Abstract

Background:

Physical activity (PA) surveillance, policy, and research efforts need to be periodically appraised to gain insight into national and global capacities for PA promotion. The aim of this paper was to assess the status and trends in PA surveillance, policy, and research in 164 countries.

Methods:

We used data from the Global Observatory for Physical Activity (GoPA!) 2015 and 2020 surveys. Comprehensive searches were performed for each country to determine the level of development of their PA surveillance, policy, and research, and the findings were verified by the GoPA! Country Contacts. Trends were analyzed based on the data available for both survey years.

Results:

The global 5-year progress in all 3 indicators was modest, with most countries either improving or staying at the same level. PA surveillance, policy, and research improved or remained at a high level in 48.1%, 40.6%, and 42.1% of the countries, respectively. PA surveillance, policy, and research scores decreased or remained at a low level in 8.3%,15.8%, and 28.6% of the countries, respectively. The highest capacity for PA promotion was found in Europe, the lowest in Africa and low- and lower-middle-income countries. Although a large percentage of the world’s population benefit from at least some PA policy, surveillance, and research efforts in their countries, 49.6 million people are without PA surveillance, 629.4 million people are without PA policy, and 108.7 million live in countries without any PA research output. A total of 6.3 billion people or 88.2% of the world’s population live in countries where PA promotion capacity should be significantly improved.

Conclusion:

Despite PA is essential for health, there are large inequalities between countries and world regions in their capacity to promote PA. Coordinated efforts are needed to reduce the inequalities and improve the global capacity for PA promotion.

Keywords: epidemiology, guidelines and recommendations, health promotion, measurement, public health practice

Before the 2019 SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic, it was estimated that approximately 1 in 4 adults did not meet the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendations for physical activity (PA).1 This has been widely recognized as a global health problem, primarily due to the increased risks of cardiovascular disease, several types of cancer, type 2 diabetes, and a range of other chronic diseases associated with insufficient PA.2,3 Growing evidence from 2020 and 2021 has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a detrimental impact on PA levels globally4,5 further exacerbating what was already a major public health issue.5–8

To tackle this problem, it is important for countries to have national policies that support a physically active lifestyle. PA research and surveillance are needed to ensure that such policies are effective and based on empirical evidence. PA surveillance, policy, and research can therefore be considered as 3 pillars underpinning PA promotion.9

The Global Observatory for Physical Activity (GoPA!)10 was established in 2012 as an independent evidence- and expert-based surveillance system to monitor and evaluate national PA surveillance, policy, and research worldwide. As such, GoPA! facilitates evidence-based PA promotion and supports global and national PA advocacy (http://www.globalphysicalactivityobservatory.com/). In 2015 GoPA! published its first report on worldwide PA surveillance, policy, and research, producing PA profiles (the Country Cards) for 139 countries.11,12 The report identified a wide range of gaps and differences in PA surveillance, policy, and research across countries, world regions, and income groups. It was estimated that one-third of the countries had periodic surveillance, one-quarter had standalone PA policies, and two-thirds had PA research outputs, thus consolidating the urgent case for periodic monitoring of these indicators.11

The second GoPA! data collection was conducted from 2019 to 2020 (referred to as “GoPA! 2020 survey”), to enable evaluation of national and global changes in the capacity for PA promotion.9 Such evaluation was needed to support global PA leadership and advocacy and to improve national capacities for PA promotion. The aim of this paper was to assess the trends in PA surveillance, policy, and research globally, based on data from the GoPA! 2015 and 2020 surveys.

Methods

Identification of Country Contacts

GoPA! country representatives, also known as “Country Contacts”, were invited to participate in GoPA!. Through their work and experience as PA researchers, policymakers, and practitioners, most Country Contacts represent academic and government sectors in the areas of PA and/or noncommunicable disease (NCD) prevention. An active search for new members is ongoing for the countries without a representative. Description of identification methods and complete list of Country Contacts can be found elsewhere.9,11

Collection and Processing of Country-Specific Data

Sample of Countries.

Consistent with the protocol and standardized methodology established before the GoPA! 2015 survey,11,12 we collected data for 217 world countries/states/economies (hereafter referred to as “countries”). A full list of countries can be found elsewhere.9 The same protocol was used in the GoPA! 2020 survey to ensure comparability of results between countries and over time.11 Only countries that had their data approved by Country Contacts were included in the analysis of this paper.

For some of the analyses, countries were grouped into 6 WHO regions, including Africa (AFRO), Eastern Mediterranean (EMRO), Europe (EURO), The Americas (PAHO), South-East Asia (SEARO), and Western Pacific (WPRO).13 Countries were also grouped by their gross national income per capita into High Income (HIC), Upper Middle Income (UMIC), Lower Middle Income (LMIC), and Low Income (LIC), according to the 2020 World Bank’s classification.14 Information on total population and Gini inequality index was obtained from the World Bank14 and Our World in Data15 websites.

PA Surveillance.

The GoPA! working group conducted comprehensive, systematic searches to identify national PA surveys and surveillance systems. The search for the GoPA! 2015 survey was conducted from July 2014 to September 2014, while the search for the GoPA! 2020 survey was conducted from April 2019 to August 2019. There were no language restrictions, and the team members doing the searches were fluent in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Documents in these languages were thus included if they were relevant to the search topic. The searches included the following sources: (1) Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program16; (2) the WHO STEPwise Approach to NCD Risk Factor Surveillance (STEPS) Report17; (3) Google using “national survey”, “physical activity”, and a country name as search terms; (4) Google using “Non-communicable disease”, “NCD”, “risk factors”, and “national survey” as search terms; (5) Google using a country name, “national survey”, and “NCD” as search terms; (6) the World Health Survey (WHS)18; and (7) information sourced from Guthold et al1 at the WHO (only in the GoPA! 2020 survey).

PA Policy.

The GoPA! working group conducted comprehensive systematized searches through WHO MiNDbank, Google, and PubMed using “physical activity”, “national policy”, and “national plan” as search terms to identify national PA plans and other PA-related policies. The search for the GoPA! 2015 survey was conducted from July 2014 to September 2014, while the search for the GoPA! 2020 survey was conducted from April to August 2019. There were no language restrictions, and the team members conducting the searches were fluent in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Documents in these languages were thus included if they were relevant to the search topic. In addition, before the 2020 survey, the GoPA! working group developed the GoPA! Policy Inventory (version 3.0), to collect more detailed information on national PA policies directly from the Country Contacts. The development and data collection methods of the GoPA! Policy Inventory are described elsewhere.19

PA Research.

The GoPA! working group conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles to assess the quantity of PA research that was conducted using country-specific data and published between 1950 and 2019. The review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and registered in the PROSPERO database (ref: CRD42017070153). The searches were conducted from August 2017 to May 2020 in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. Details about the literature search can be found elsewhere.9,10,12,20

The population-adjusted contribution to worldwide PA research was estimated for each country using the following formula: . To be considered as part of the country’s research output, the article had to explicitly show that the research was conducted in the country or included local data. A score above 1 indicates a contribution to worldwide PA research above the global average and a score below 1 indicates a contribution below the global average. For each country, the score was estimated for the 2010–2014 and 2015–2019 periods.

Data Assessment and Approval

The GoPA! data collected through literature searches were reviewed and verified in 2015 and 2020 by representatives for 139 and 164 countries, respectively. Country Contacts could complement the information found in the literature searches with documents in the country’s native language. For the purpose of comparisons between the first and second surveys we used the data from 133 countries for which country contacts verified data in both surveys.

Scoring System

The GoPA! conceptual model for quantifying country-level capacity for PA promotion (ie, an aggregate of data on surveillance, policy, and research for PA) was used to assign a rating for each country.21 The scoring protocol and variable definitions are described in Table 1. Country Contacts revised and approved the country data, and the core research team scored and analyzed it based on the standardized scoring system presented in Table 1. More details on development of the country capacity categorization for PA promotion can be found elsewhere.21

Table 1.

Assessment of Country Progress in Physical Activity Surveillance, Policy, and Research Capacity

| Categories’ designation | National physical activity surveillance | National physical activity policy | Population-adjusted physical activity research contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green: Improved or stayed at the highest level of the indicator | Green: Periodic physical activity surveillance (first, most recent, and next surveys were determined from the 2015 and 2020 GoPA! surveys) OR an increase in the number of surveys identified in the 2020 GoPA! survey | Green: Standalone physical activity policies in the 2015 and 2020 GoPA! surveys OR transition to a standalone policy in the 2020 GoPA! survey | Green: Physical activity research was above the global average in both 2010–2014 AND 2015–2019 periods |

| Yellow: Stayed at the same level of the indicator | Yellow: First and most recent surveys were determined, but not a plan for a next or future survey including physical activity | Yellow: NCD plans including physical activity in the 2015 and 2020 GoPA! surveys OR a standalone physical activity policy in the 2015 but not in the 2020 GoPA! survey | Yellow: Physical activity research was above the global average in 2010–2014 OR 2015–2019 periods |

| Red: Decreased or stayed at the lowest level of the indicator | Red: Only a first survey was determined from the 2015 and 2020 GoPA! surveys (not a most recent or next/future survey) OR there was no surveillance data for the 2020 GoPA! survey | Red: NCD plans including physical activity in the 2015 OR 2020 GoPA! survey (but not both) | Red: Physical activity research was below the global average in both 2010–2014 AND 2015–2019 periods |

| Black: No data available for the indicator | Black: No physical activity surveillance data | Black: No physical activity policy data | Black: No physical activity research articles |

Abbreviation: GoPA!, Global Observatory for Physical Activity; NCD, noncommunicable disease.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses of surveillance, policy, and research indicators were conducted for all countries in the sample and stratified by world region and income group. PA surveillance, policy, and research progress were determined based on comparisons between the first and second surveys (Table 1). The statistical analyses were conducted in STATA (version 17.0, StataCorp) and the graphs were conducted in R (version 4.1.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Global Coverage

A total of 139 countries had representatives in the GoPA! 2015 survey (covering 64.1% of the countries and 84.0% of the world’s population), and 164 countries had representatives in the GoPA! 2020 survey (covering 75.6% of the countries and 98.8% of the world’s population). The number of countries with representatives in GoPA! surveys increased by 18.0% from 2015 to 2020. Of the 164 countries in 2020, 133 were also represented in 2015, while 6 countries (Bahrain, Bulgaria, Greenland, Maldives, Swaziland, and Tunisia) lost their representation (due to staff turnover of dedicated country contacts in most cases), and representatives from 31 new countries from Eastern Europe and the Caribbean and Pacific Islands contributed to the survey in 2020. In the GoPA! 2020 survey, 48 countries (29.3% of the GoPA! countries) had more than one Country Contact. The number of countries with more than one GoPA! representative has increased since 2015.

The survey participation increased from 2015 to 2020 across all income groups and most world regions except SEARO as follows: HICs (+3.3%), UMICs (+13.0%), LMICs (+20.0%), and LICs (+8.0%), AFRO (+21.3%), EMRO (+9.1%), EURO (+8.1%), PAHO (+18.2%), SEARO (−9.1%), and WPRO (+3.3%).

In both GoPA! surveys, a higher participation rate was associated with higher country income groups. Only 34.5% of LICs participated in GoPA! 2020 survey compared with 85.4% of HICs. The second set of GoPA! Country Cards including 164 countries can be found in the “second Physical Activity Almanac”,9 available at the GoPA! website (http://www.globalphysicalactivityobservatory.com/).

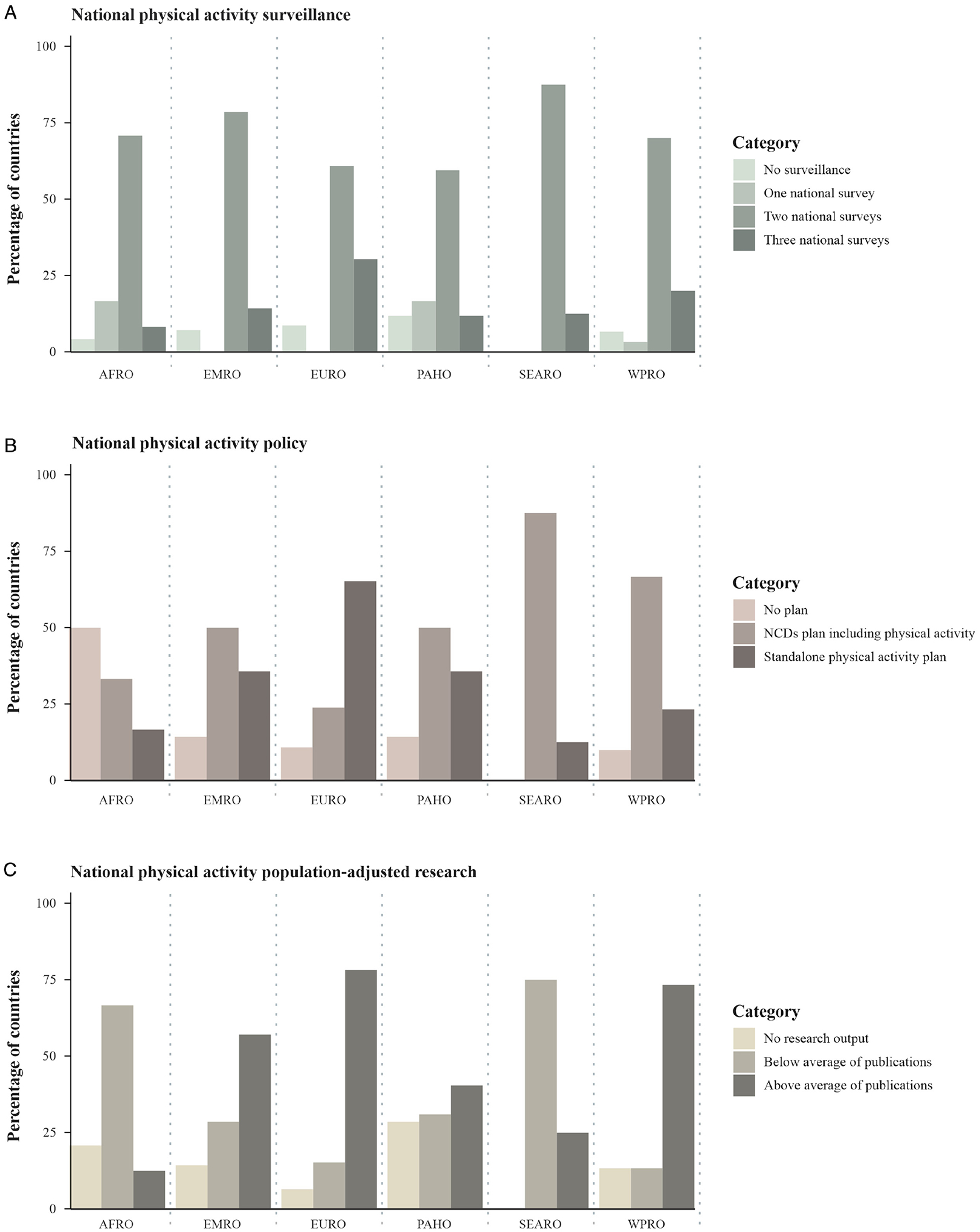

Status of Global PA

The GoPA! 2020 survey found that 92.1% of countries conducted at least one national survey on PA, 66.5% of countries at least 2 surveys, while only 18.3% of countries had 3 or more surveys and a plan for a future survey. The percentage of countries with periodic PA surveillance varied by region and income group, from 30.4% in EURO to 8.3% in AFRO region (Figure 1), and from 27.1% in HICs to 0.0% in LICs (Figure 2).

Figure 1 —

Physical activity surveillance, policy, and research characteristics by world region based on the 2020 GoPA! survey. AFRO indicates Africa; EMRO, Eastern Mediterranean; EURO, Europe; GoPA!, Global Observatory for Physical Activity; NCD, noncommunicable disease; PAHO, The Americas; SEARO, South-East Asia; WPRO, Western Pacific.

Note: The lighter-colored bars show the indicators’ lowest level (ie, surveillance: no surveillance, policy: no plan, population-adjusted research: no research output). The darker-colored bars show the indicators’ highest level (ie, surveillance: 3 national surveys, policy: standalone physical activity plan, research: above average of publications). For the most accurate interpretation of this graph (full range of color) please refer to the electronic version of the manuscript.

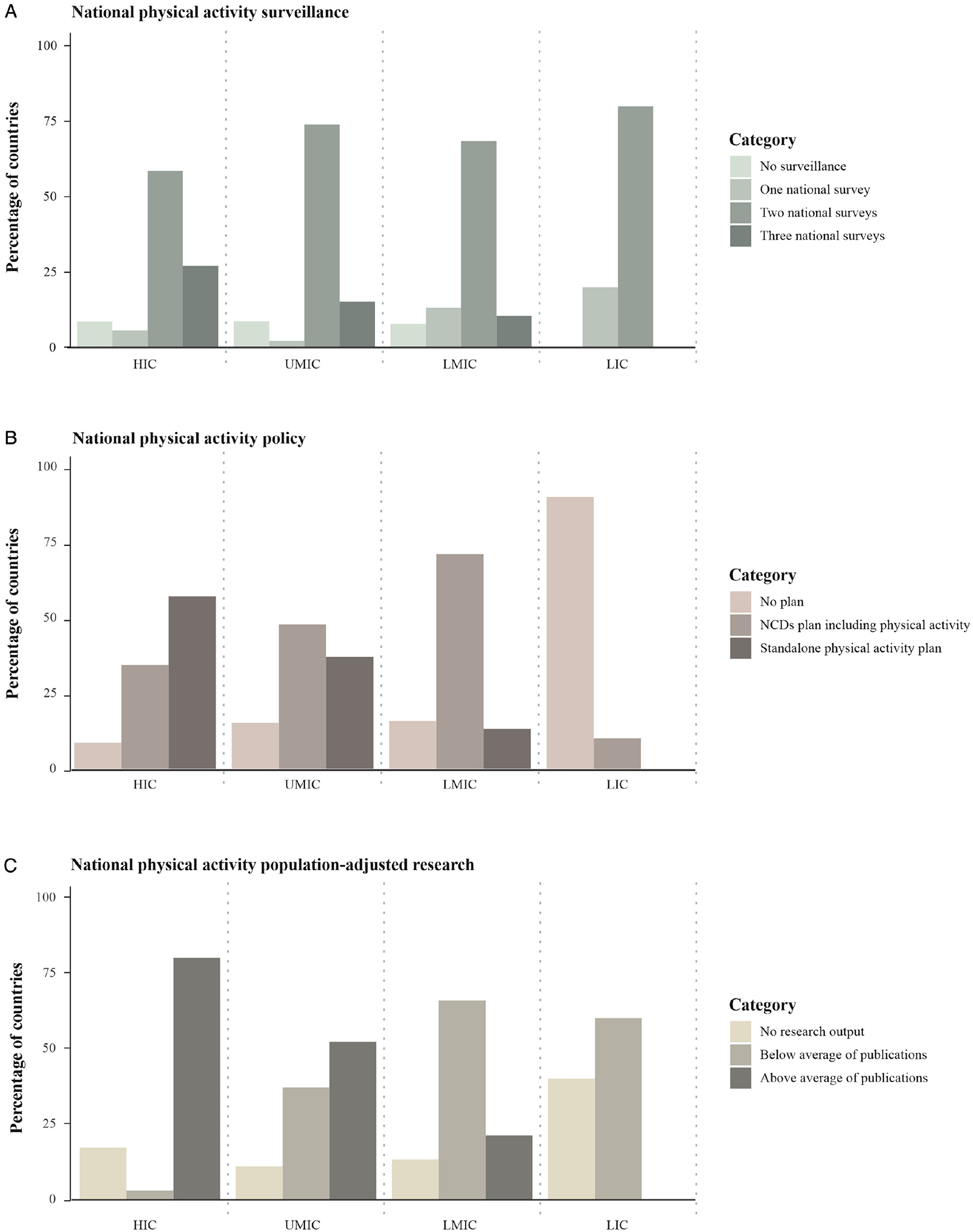

Figure 2 —

Physical activity surveillance, policy, and research characteristics by income group based on the 2020 GoPA! survey. GoPA! indicates Global Observatory for Physical Activity; HIC, high-income country; LIC, low-income country; LMIC, lower-middle-income country; NCD, noncommunicable disease; UMIC, upper-middle-income country.

Note: The lighter-colored bars show the indicators’ lowest level (ie, surveillance: no surveillance, policy: no plan, population-adjusted research: no research output). The darker-colored bars show the indicators’ highest level (ie, surveillance: 3 national surveys, policy: standalone physical activity plan, research: above average of publications). For the most accurate interpretation of this graph (full range of color) please refer to the electronic version of the manuscript.

The percentage of countries with PA policies also varied by world region (Figure 1). We found that 37.8% of the countries had a standalone PA policy, 45.1% had a PA policy embedded in their NCD prevention plan, and 17.1% did not have a PA policy. The highest percentage of countries with a standalone policy was in the EURO region (65.2%), followed by the PAHO and EMRO regions (35.7% in each). In terms of the income groups, 91.4% of HICs and only 10.0% of LICs had a PA policy, either standalone or included in an NCD policy (Figure 2). This constitutes almost a 10-fold difference between HICs and LICs in the prevalence of PA policies.

Furthermore, for 15.9% of countries, we found no PA research output. In the EURO and WPRO regions, 78.3% and 73.3% of countries, respectively, had above average contributions to the global research output. For 3 quarters of countries in the SEARO region, the contribution was below the global average. The AFRO region had the second highest (after SEARO) percentage of countries with “low” research productivity. In most HICs and UMICs, research contribution was above the global average and in most LMICs and LICs, the contribution was below the global average.

The overall capacity for PA promotion varied greatly across world regions and income groups. The highest overall capacity was found for the EURO region (all 3 indicators at the highest level), followed by the WPRO region (2 indicators at the highest level and 1 indicator at the middle level), and PAHO (2 indicators at the highest level and 1 indicator at the lowest level). The lowest overall capacity for PA promotion was found for the AFRO region, with 1 indicator at the middle level and 2 indicators at the lowest level (Figure 3).

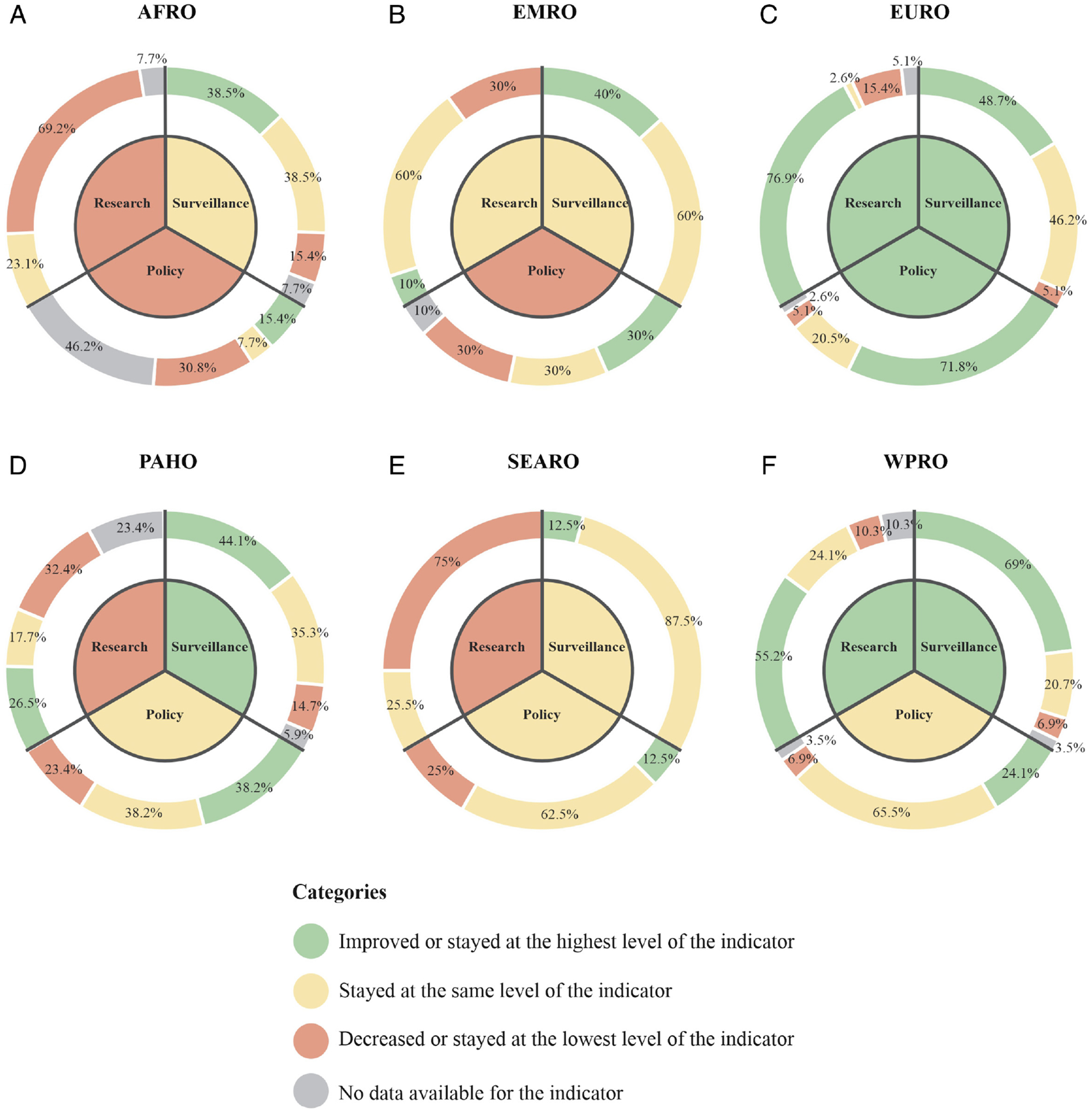

Figure 3 —

Estimated number of countries with low, medium, and high capacity for physical activity promotion. AFRO indicates Africa; EMRO, Eastern Mediterranean; EURO, Europe; PAHO, The Americas; SEARO, South-East Asia; WPRO, Western Pacific.

Note: The levels of the indicators, from lightest to darkest, are: Stayed at the same level of the indicator (light color), Improved or stayed at the highest level of the indicator, No data available for the indicator, and Decreased or stayed at the lowest level of the indicator (dark color). For the most accurate interpretation of this graph (full range of color) please refer to the electronic version of the manuscript.

When translated into population estimates, the data suggest that 2.7 billion people (37.1%) lived in a country with periodic PA surveillance, 4.5 billion people (62.3%) in a country with at least 2 surveys, and 49.6 million people (0.7%) in a country with no surveys (Figure 4). In addition, 3.4 billion people (47.5%) lived in a country with a standalone PA policy, 3.1 billion people (43.7%) with PA included in an NCD prevention policy, and 629.4 million people (8.8%) in a country without a policy (Figure 4). For research, it was estimated that 1.7 billion people (24.1%) lived in a country with PA research productivity above the global average, 5.3 billion people (74.4%) with a productivity below the global average, and 108.7 million people (1.5%) without any PA research output (Figure 4).

Figure 4 —

Global physical activity surveillance, policy, and research: GoPA! categories by country population, income, and region.

Note: Random noise was added to minimize countries’ overplotting according to H. Wickham22 with the countries maintaining their position based on the indicator and income group. For example, POL and ITA both have 2 national surveys (upper left) and are high-income countries; the random noise prevents them from overlapping but keeps them in their respective positions inside the cell, as determined by the indicator and their respective income group classification. AFRO indicates Africa; ARG, Argentina; BGD, Bangladesh; BRA, Brazil; CHN, China; COL, Colombia; EGY, Egypt, Arab Rep.; EMRO, Eastern Mediterranean; ESP, Spain; EURO, Europe; ETH, Ethiopia; DEU, Germany; GoPA!, Global Observatory for Physical Activity; HIC, high-income country; IND, India; IDN, Indonesia; IRN, Iran, Islamic Rep.; IRQ, Iraq; ITA, Italy; KEN, Kenya; KOR, Korea, Rep.; LIC, low-income country; LMIC, lower-middle-income country; MYS, Malaysia; MEX, Mexico; MAR, Morocco; MOZ, Mozambique; MMR, Myanmar; PAHO, The Americas; PAK, Pakistan; PER, Peru; PHL, Philippines; POL, Poland; RUS, Russian Federation; SEARO, South-East Asia; SAU, Saudi Arabia; TZA, Tanzania; THA, Thailand; TUR, Turkey; UGA, Uganda; UKR, Ukraine; UMIC, upper-middle-income country; USA, United States; VNM, Vietnam; WPRO, Western Pacific; ZAF, South Africa. Note: The regions from lightest to darkest on the color scale are: PAHO, EURO, EMRO, AFRO, SEARO, and WPRO. For the most accurate interpretation of this graph (full range of color) please refer to the electronic version of the manuscript.

Trends in Global PA Based on the First and Second GoPA! Surveys

PA Surveillance.

The comparison of PA indicators included 133 countries. In regard to national PA surveillance, the majority of countries improved or remained at the same level (Figure 5). The WPRO region had the highest share of countries (69.0%) where the indicator improved or stayed at the highest level, compared with the AFRO region where 15.4% of countries stayed (ie, have never had periodic surveillance) or decreased to the lowest level of the indicator (ie, previously reported any kind of surveillance but in the 2020 survey did not report current surveillance efforts or future plans). A decreased capacity was reported in 5.0%, 3.4%, and 2.6% of the EURO, WPRO, and PAHO countries, respectively (data not shown in tables).

Figure 5 —

Progress in national physical activity surveillance, policy, and research by world region.

Note: The reference period was 2015–2020 for surveillance and policy and 2010–2019 for research. The inner circles in each radial plot accumulate a percentage, thus the first inner circle represents 20.0% and the last inner circle represents 100.0%. Each region is represented by a color, for example, the first radial plot (top left) shows that 69.0% of countries in the WPRO region (dark blue) improved or stayed at the highest surveillance level. AFRO indicates Africa; EMRO, Eastern Mediterranean; EURO, Europe; PAHO, The Americas; SEARO, South-East Asia; WPRO, Western Pacific.

Note: The regions from lightest to darkest on the color scale are: PAHO, EURO, EMRO, AFRO, SEARO, and WPRO. For the most accurate interpretation of this graph (full range of color) please refer to the electronic version of the manuscript.

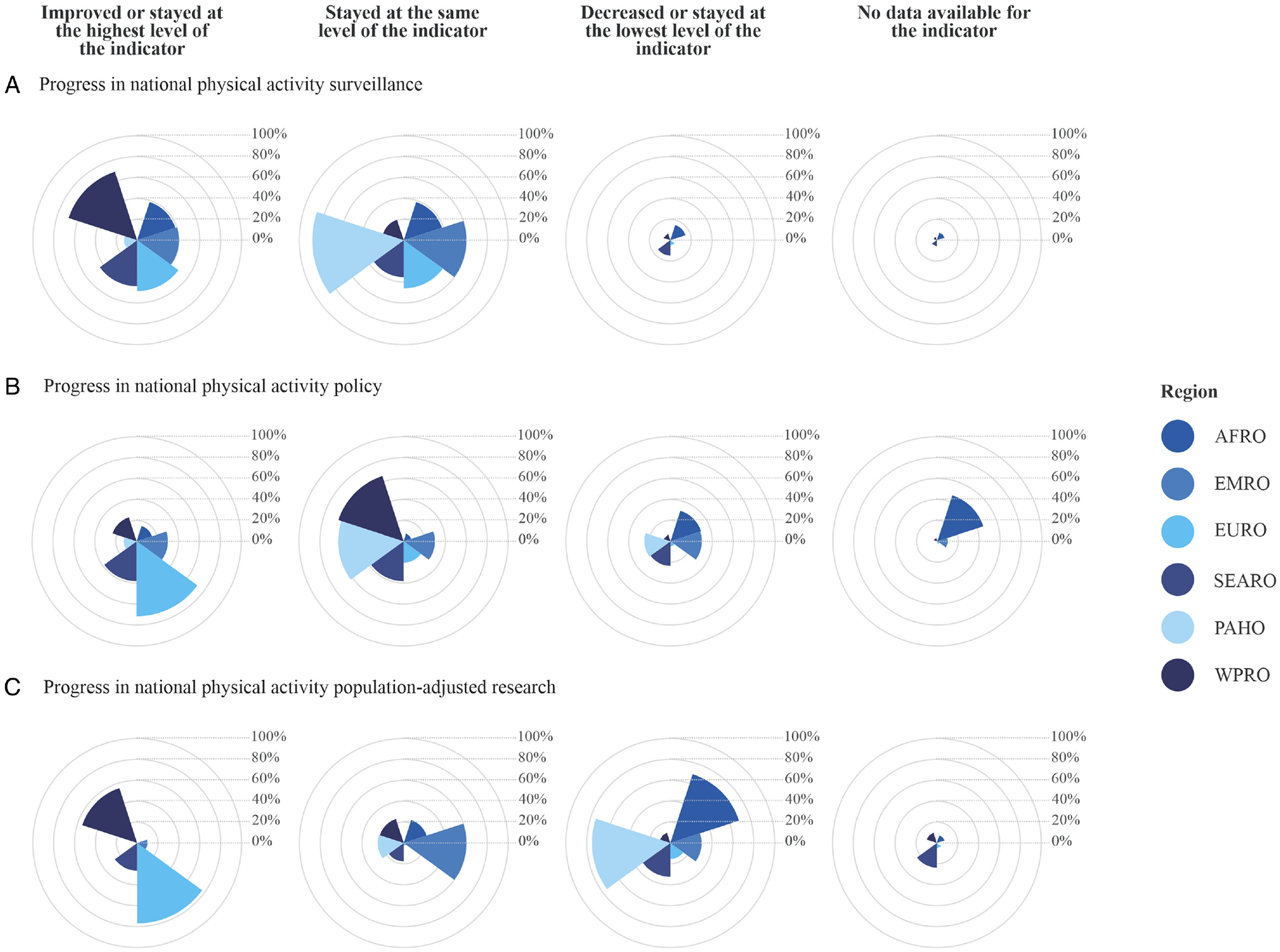

In terms of income groups, an equal or increased surveillance capacity was found for 49.2% of the HICs, 50.0% of UMICs, 40.7% of LMICs, and 60.0% of LICs. Twenty percent of the LICs decreased their score or stayed at the lowest level of the indicator (Figure 6).

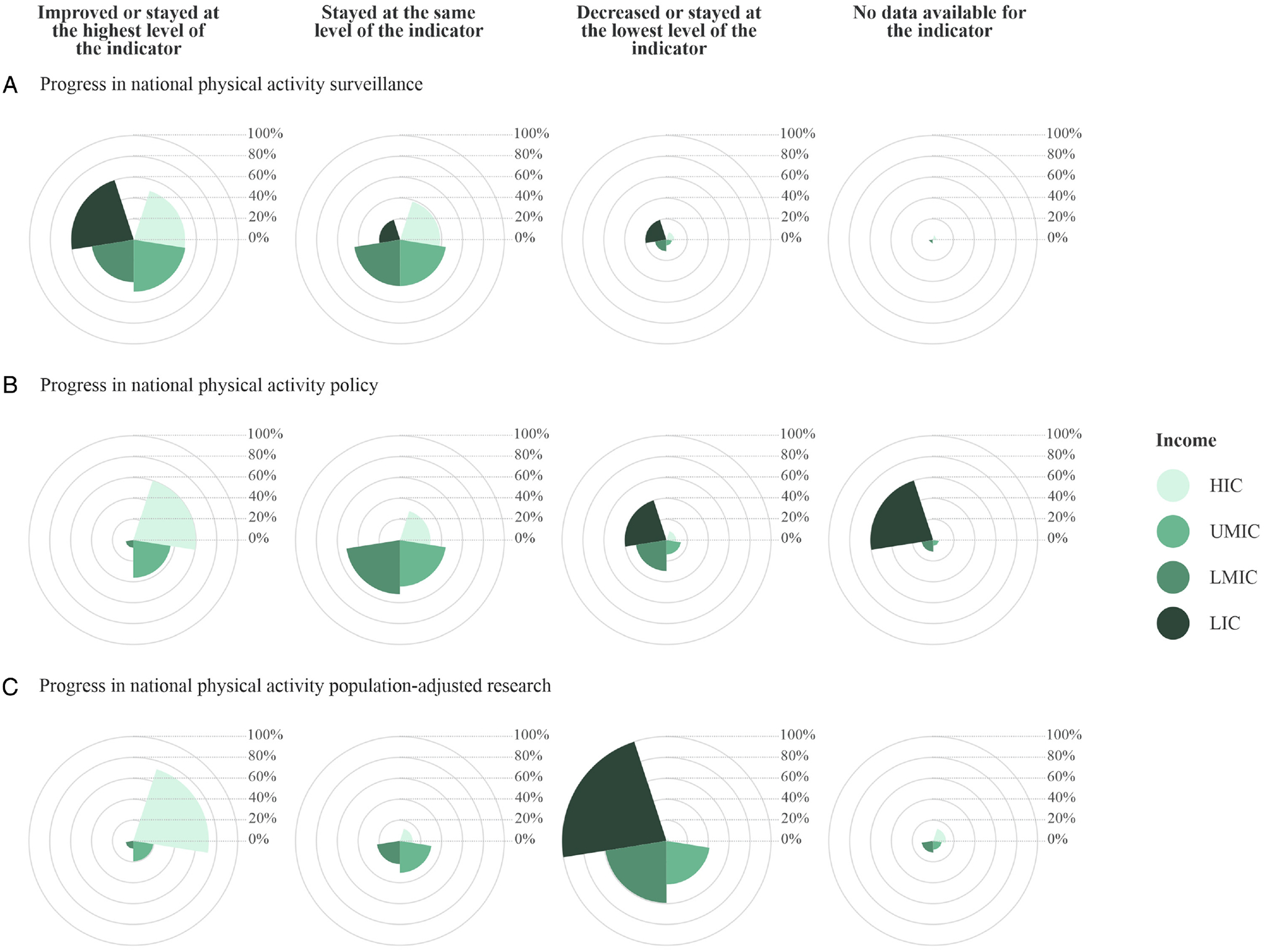

Figure 6 —

Progress in national physical activity surveillance, policy, and research by income group.

Note: The reference period was 2015–2020 for surveillance and policy and 2010–2019 for research. The inner circles in each radial plot accumulate a percentage, thus the first inner circle represents 20.0% and the last inner circle represents 100.0%. Each income group is represented by a color, for example, the first radial plot (top left) shows that 60.0% of the LICs (dark green) improved or stayed at the highest surveillance level. HIC indicates high-income country; LIC, low-income country; LMIC, lower-middle-income country; UMIC, upper-middle-income country.

Note: The income groups from lightest to darkest on the color scale are: HIC, UMIC, LMIC, and LIC. For the most accurate interpretation of this graph (full range of color) please refer to the electronic version of the manuscript.

PA Policy.

The comparison of PA policy indicators showed that most countries also improved or remained at the same level (Figure 5). EURO was the region with the highest percentage of countries (71.8%) that improved or stayed at the highest level for this indicator. AFRO was the region with the highest percentage of countries (30.8%) that stayed or decreased to the lowest level for the indicator (ie, did not report the existence of any policy or reported the existence of an NCD plan including PA in only one of the two GoPA! surveys). A decreased capacity was reported in 11.8%, 10.0%, 5.1%, and 3.4% of PAHO, EMRO, EURO, and WPRO countries, respectively (data not shown in tables).

More than half of HICs (60.0%) improved or stayed at the highest level for this indicator, while this was achieved by 38.9% of UMICs, 7.4% LMICs, and none of the LICs. Also, 20.0% of LICs decreased or stayed at the lowest level for this indicator (Figure 6).

PA Research.

The comparison of PA research indicators showed that most countries in the EURO and WPRO regions (76.9% and 55.2%, respectively) improved or stayed at the highest level of the indicator, whereas 75.0% of countries in the SEARO region and 69.0% of countries in the AFRO region decreased or remained at the lowest level (Figure 5). The population-adjusted research productivity improved or stayed the same in 72.3% of HICs, 19.4% of UMICs, and 7.4% of LMICs. The population-adjusted research productivity in all LICs decreased or stayed at the lowest level for this indicator (ie, a contribution to worldwide PA research below the global average) (Figure 6).

When analyzing the changes in all 3 indicators collectively, 38.5%, 10.3%, and 5.9% of countries in the EURO, WPRO, and PAHO regions, respectively, improved or stayed at the highest level for all 3 indicators. In the SEARO and EMRO regions, 25.0% and 10.0% of the countries stayed at the same level for all 3 indicators, respectively. Twenty-three percent of countries in the AFRO region decreased or stayed at the lowest level for all 3 indicators (data not shown in tables).

Discussion

The key findings on the status and progress in PA surveillance, policy, and research based on data from the GoPA! 2015 and 2020 surveys are as follows: First, the overall capacity for PA promotion varied greatly across countries, world regions, and income groups. The highest capacity was found for EURO, followed by WPRO and PAHO regions, and the lowest was found for the AFRO region and LICs and LMICs. This translated to an estimated 145 million people or 2.0% of the world’s population living in countries with a low capacity for or no data on PA promotion. Second, although most countries benefit from some kind of PA surveillance, policy, and research, having periodic national PA surveillance, standalone policies, and high research productivity (ie, all of the 3 elements underpinning PA promotion) is very uncommon. In particular, an estimated 6.3 billion people or 88.2% of the world’s population live in countries where the capacity for PA promotion can be significantly improved; 3.1 billion of these people live in LICs and LMICs. Third, almost 70.0% of the world’s population (5.0 billion people) live in a country without periodic PA surveillance, 10.0% of the world’s population (629.4 million people) live in a country without any PA policy, and at least 75.0% of the population (5.4 billion people) live in a country with PA research productivity below the global average. Fourth, the global 5-year progress in surveillance, policy, and research indicators was modest, with LICs and the AFRO, EMRO, and SEARO regions lagging even further behind.

Many individuals live in countries that do not have adequate PA surveillance, policy, and research for facilitating PA promotion.23–25 PA is often incorrectly considered to be an individual rather than collective responsibility,26 while, in fact, political, social, economic, and built environments play key roles in shaping population PA behavior.27–32 Putting the “blame” on individuals while failing to prioritize PA in national public health agendas is malpractice and may explain why the global prevalence of PA has not improved in the last decades.1,33,34

According to our study, most countries do not have periodic PA surveillance. This finding is in accordance with the new NCD Progress Monitor 2022 report showing that fewer than 20.0% of WHO Member States conducted a STEPS survey or other comprehensive health examination survey every 5 years.35 This widespread lack of periodic PA surveillance hinders the implementation and evaluation of evidence-based PA policies. Public health initiatives to increase PA need to be clearly prioritized in national policies, and PA surveillance is of utmost importance for assessing the overall effectiveness of these interventions. Improving national surveillance must be a public health priority, to monitor prevalence and trends and to better inform the development and evaluation of national health policies.

Progress in the development of national PA policies has been slow and unequal. Standalone PA policies are seen more frequently in HICs and in the EURO region, compared with other income groups and world regions. From a health equity perspective and in accordance with the United Nations’ declaration on the prevention of NCDs,36 LMICs and LICs countries should be supported in their efforts to increase funding, implement surveillance systems25 that are consistent and sustainable, improve research and public health capacity, governance and political will related to PA promotion. Whole-of-government and systems approaches that facilitate physically active lifestyles are also needed37,38 as recommended in the WHO Global Action Plan for Physical Activity39,40 and GoPA!-like policy monitoring initiatives such as the NCD Country Capacity Survey from the WHO Global Health Observatory,41 and the Health-Enhancing Physical Activity (HEPA) monitoring framework for the European Union.42 These approaches may help countries tackle the rising burden of NCDs25 and build healthier and more resilient populations in the context of the current challenges of pandemics and climate change.43

Even though LMICs are home to more than 80.0% of the world’s population, they collectively conduct less PA research than HICs. More PA research infrastructure is urgently needed in LMICs to inform the development of contextually relevant policies and programs for this major part of the global population.39 Due to limited resources,44–46 building research capacity in LMICs is often challenging and requires coordinated efforts at individual, institutional, and national levels,47,48 and familiarity with the local context and its challenges. The academic community in HICs should help develop global capacity for PA research by sharing their expertise and resources with researchers from LMICs.

The AFRO region had the lowest capacity for PA promotion and showed limited progress between 2015 and 2020. There are several potential explanations. First, countries in this region remain focused on the prevention and management of prevalent infectious diseases such as malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis. Infectious diseases present competing priorities for policymakers considering how to address PA promotion and the dual burden of NCDs and infectious diseases. Second, most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, where NCDs are highly prevalent and have been on the rise over the past 2 decades,49,50 are LICs or LMICs with limited resources to develop national PA surveillance, policy, and research. Third, despite the previous efforts of the African Physical Activity Network to increase PA capacity in the region, developing a viable and sustainable workforce remains a challenge for many countries.51,52

Strengths and Limitations

The key strengths of this study are: (1) analysis of PA surveillance, policy, and research indicators from two-thirds of the world’s countries verified by Country Contacts (local experts); (2) first of its kind evaluation of temporal changes in PA surveillance, policy, and research based on 2 surveys (2015 and 2020) with standardized indicators; (3) a good representation of countries from different world regions and income groups; and (4) the scoring system employed provided a straightforward measure of progress of PA surveillance, policy, and research with meaningful comparisons across world regions and income groups.

However, some limitations of the study must be taken into account while interpreting our findings. First, 53 countries were not included in the current study because they did not have GoPA! Country Contacts. Most of these 53 countries are in the AFRO and EMRO regions, and this lack of data may have affected the evaluation and comparisons between regions. Second, only the availability of reported PA policies was analyzed. It is possible that in some countries PA policies and research production exist within the gray literature or informal documents but were not reported by the Country Contact or were not picked up by the comprehensive searches. Third, other monitoring efforts use different indicators to quantify various elements of PA policy limiting comparability. For example, the HEPA monitoring framework for the European Union42 and the Active Healthy Kids Global Alliance53 are limited to the European Union countries and children, respectively. Fourth, GoPA! has yet to conduct case studies to shed light on the country-specific circumstances that contributed to the observed progress on indicators but might not have been captured by the scoring method employed. Finally, we did not assess the quality of PA surveillance, policy, and research. Having systems in place that do not include underrepresented subgroups in the population or that are not implemented with fidelity may not improve the capacity for PA promotion. Although such an analysis would provide additional important insights into the capacity for PA promotion, it was beyond the scope of the current study.

Conclusions

The overall capacity for PA promotion is remarkably unequal across world regions and income groups, and global 5-year progress in PA surveillance, policy, and research was modest. Therefore, the majority of the world’s population live in countries where PA promotion capacity should be significantly improved. Most countries do not have periodic surveillance of PA and a standalone PA policy. In nearly every sixth country, no research on PA was conducted from 2010 to 2020. GoPA! will continue to monitor PA surveillance, policy, and research globally and identify strategies to increase the capacity for national PA promotion. GoPA! will also continue to make the case for national PA promotion using multisectoral approaches consistent with the WHO Global Action Plan for Physical Activity.40 Ensuring healthy, resilient, and active populations and communities worldwide remains a key public health goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all GoPA! Country Contacts and their teams for reviewing, providing, and approving data for their countries. We appreciate their contributions over the past decade. In particular we would like to thank: Aaron Sim (Singapore), Abchir Houdon, (Djibouti), Angela Koh (Singapore), Audrey Tong (Singapore), Bharathi Viswanathan (Seychelles), Franklyn Edwin Prieto Alvarado (Colombia), Enrique Medina Sandino (Nicaragua), Galina Obreja (Republic of Moldova), Geoffrey P. Whitfield (United States), Gladys Bequer (Cuba), Isabel Cardenas (Bolivia), Juan Rivera (Mexico), Kyaw Zin Thant (Myanmar), Lisa Indar (Caribbean Islands), Louay Labban (Syrian Arab Republic), Lyna E. Fredericks (Virgin Islands), Migle Baceviciene (Lithuania), Mya Lay Sein (Myanmar), Nazan Yardim (Turkey), Olavur Jokladal (Faeroe Islands), Omar Badjie (Gambia), Saad Hassan Aden (Djibouti), Sawadogo Amidou (Burkina Faso), Seyed Ali Hosseini (Iran), Sigridur Lara Gudmundsdottir (Iceland), Takese Foga (Jamaica), Tatiana I Andreeva (Ukraine), Than Naing Soe (Myanmar), Thelma Sanchez (Costa Rica), Tigri Tertulie Lamatou Nawal (Benin), Vera Amanda Solís (Nicaragua), and Wilbroad Mutale (Zambia). We also wish to thank to Cintia Borges and Paulo Ferreira from Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Brazil for the graphic design and GoPA! website management. This research was funded in part by the University of California San Diego, United States, Universidad Federal de Pelotas, Brazil, and Universidad de los Andes, Colombia.

Appendix: Author Affiliations and ORCID Numbers

Andrea Ramírez Varela,1 Pedro C. Hallal,2 Juliana Mejía Grueso,1 Željko Pedišić,3 Deborah Salvo,4 Anita Nguyen,5 Bojana Klepac,3,6 Adrian Bauman,7 Katja Siefken,8 Erica Hinckson,9 Adewale L. Oyeyemi,10,11 Justin Richards,12 Elena Daniela Salih Khidir,13 Shigeru Inoue,14 Shiho Amagasa,14,15 Alejandra Jauregui,16 Marcelo Cozzensa da Silva,2 I-Min Lee,17,18 Melody Ding,7 Harold W. Kohl III,4,19 Ulf Ekelund,20,21 Gregory W. Heath,22 Kenneth E. Powell,23 Charlie Foster,24 Aamir Raoof Memon,3,25 Abdoulaye Doumbia,26 Abdul Roof Rather,27 Abdur Razzaque Adama Diouf,29 Adriano Akira Hino,30 Albertino Damasceno,31 Alem Deksisa Abebe,32 Alex Antonio Florindo,33 Alice Mannocci,34 Altyn Aringazina,35 Andrea Backović Juričan,36 Andrea Poffet,37 Andrew Decelis,38 Angela Carlin,39 Angelica Enescu,40 Angélica María Ochoa Avilés,41 Anna Kontsevaya,42 Annamaria Somhegyi,43 Anne Vuillemin,44 Asmaa El Hamdouchi,45 Asse Amangoua Théodore,46 Bojan Masanovic,47 Brigid M. Lynch,48,49,50 Catalina Medina,16 Cecilia del Campo,51 Chalchisa Abdeta,52 Changa Moreways,53 Chathuranga Ranasinghe,54 Christina Howitt,55 Christine Cameron,56 Danijel Jurakić,57 David Martinez-Gomez,58,59,60 Dawn Tladi,61 Debrework Tesfaye Diro,62 Deepti Adlakha,63 Dušan Mitić,64 Duško Bjelica,47 Elżbieta Biernat,65 Enock M. Chisati,66 Estelle Victoria Lambert,67 Ester Cerin,68,69 Eun-Young Lee,70 Eva-Maria Riso,71 Felicia Cañete Villalba,72 Felix Assah,73 Franjo Lovrić,74 Gerardo A. Araya-Vargas,75,76 Giuseppe La Torre,77 Gloria Isabel Niño Cruz,78 Gul Baltaci,79 Haleama Al Sabbah,80 Hanna Nalecz,81 Hilde Liisa Nashandi,82 Hyuntae Park,83 Inés Revuelta-Sánchez,76 Jackline Jema Nusurupia,84 Jaime Leppe Zamora,85 Jaroslava Kopcakova,86 Javier Brazo-Sayavera,87 Jean-Michel Oppert,88 Jinlei Nie,89 John C. Spence,90 John Stewart Bradley,91 Jorge Mota,92 Josef Mitáš,93 Junshi Chen,94 Kamilah S Hylton,95 Karel Fromel,93 Karen Milton,96 Katja Borodulin,97 Keita Amadou Moustapha,98,99,100 Kevin Martinez-Folgar,101 Lara Nasreddine,102 Lars Breum Christiansen,103 Laurent Malisoux,104 Leapetswe Malete,105 Lorelie C. Grepo-Jalao,106 Luciana Zaranza Monteiro,107 Lyutha K. Al Subhi,108 Maja Dakskobler,36 Majed Alnaji,109 Margarita Claramunt Garro,110 Maria Hagströmer,111 Marie H. Murphy,39 Matthew Mclaughlin,112 Mercedes Rivera-Morales,113 Mickey Scheinowitz,114 Mimoza Shkodra,115 Monika Piątkowska,116 Moushumi Chaudhury,117 Naif Ziyad Alrashdi,118,119 Nanette Mutrie,120 Niamh Murphy,121 Norhayati Haji Ahmad,122 Nour A. Obeidat,123 Nubia Yaneth Ruiz Gómez,124 Nucharapon Liangruenrom,125 Oscar Díaz Arnesto,126 Oscar Flores-Flores,127,128 Oscar Incarbone,129 Oyun Chimeddamba,130 Pascal Bovet,131,132 Pedro Magalhães,133 Pekka Jousilahti,134 Piyawat Katewongsa,125,135 Rafael Alexander Leandro Gómez,124 Rawan Awni Shihab,123 Reginald Ocansey,136 Réka Veress,137 Richard Marine,138 Rolando Carrizales-Ramos,139,140 Saad Younis Saeed,141 Said El-Ashker,142 Samuel Green,143 Sandra Kasoma,144 Santiago Beretervide,145 Se-Sergio Baldew,146 Selby Nichols,147 Selina Khoo,148 Seyed Ali Hosseini,149 Shifalika Goenka,150,151 Shima Gholamalishahi,152 Soewarta Kosen,153 Sofie Compernolle,154 Stefan Paul Enescu,40 Stevo Popovic,47 Susan Paudel,41 Susana Andrade,41 Sylvia Titze,156 Tamu Davidson,157 Theogene Dusingizimana,158 Thomas E. Dorner,159 Tracy L. Kolbe-Alexander,160,161 Tran Thanh Huong,162 Vanphanom Sychareun,163 Vera Jarevska-Simovska,164 Viliami Kulikefu Puloka,165 Vincent Onywera,166 Wanda Wendel-Vos,167 Yannis Dionyssiotis,168 and Michael Pratt,5

1School of Medicine, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia

2Post-graduate Program in Epidemiology, Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, RS, Brazil

3Institute for Health and Sport, Victoria University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

4Department of Kinesiology and Health Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA

5School of Medicine, Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

6Mitchell Institute for Education and Health Policy, Victoria University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

7School of Public Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

8Department Performance, Neuroscience, Therapy & Health, MSH Medical School Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

9Human Potential Centre, School of Sport and Recreation, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

10Department of Physiotherapy, Redeemer’s University, Ede, Nigeria

11Department of Physiotherapy, University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria

12Te Hau Kori, Faculty of Health, Victoria University Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand

13Aspetar Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Hospital, Doha, Qatar

14Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

15Graduate School of Public Health, Teikyo University, Tokyo, Japan

16Department of Physical Activity and Healthy Lifestyles, Center for Nutrition and Health Research, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Cuernavaca, Mexico

17Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

18Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

19University of Texas Health Science Center, School of Public Health, Austin, TX, USA

20Department of Sport Medicine, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, Oslo, Norway

21Department of Chronic Diseases, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway

22College of Medicine Chattanooga, University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, TN, USA

23Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA

24University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

25Institute of Physiotherapy & Rehabilitation Sciences, Peoples University of Medical & Health Sciences for Women, Nawabshah, Pakistan

26National Institute of Youth and Sports Mali, Mali, Bamako

27Department of Physical Education, School of Education, Central University of Kashmir, Ganderbal, Jammu and Kashmir, India

28Health Systems and Population Studies Division, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Dhaka, Bangladesh

29Laboratoire de Recherche en Nutrition et Alimentation Humaine, Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (UCAD), Dakar, Senegal

30Graduate Program in Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

31Faculty of Medicine, Eduardo Mondlane University, Maputo, Mozambique

32Public Health, Adama Hospital Medical College, Adama, Ethiopia

33School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities at University of São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

34Faculty of Economics, Universitas Mercatorum, Rome, Italy

35Department of Public Health, Caspian University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

36National Institute for Public Health, Ljubljana, Slovenia

37Division Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases, Department of NCD Prevention, Directorate for Prevention and Health Care, Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), Schwarzenburgstrasse, Switzerland

38Institute for Physical Education and Sport, University of Malta, Msida, Malta

39Centre for Exercise Medicine, Physical Activity and Health, Sports and Exercise Sciences Research Institute, Ulster University, Newtownabbey, United Kingdom

40Researcher, Romania

41Department of Bioscience, Universidad de Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador

42National Medical Research Center for Preventive Medicine, Russian Federation

43National Center for Spinal Disorders, Budapest, Hungary

44Laboratoire Motricité Humaine expertise Sport Santé (LAMHESS), Université Côte d’Azur, Nice, France

45Unité de Nutrition et Alimentation, Centre National de l’Energie, des Sciences et des Techniques Nucléaires (CNESTEN), Maroc, Morocco

46Sport and Physical Activity Division, Institut National Polytechnique Félix Houphouët-Boigny (INP-HB), Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire

47Faculty for Sport and Physical Education, University of Montenegro, Niksic, Montenegro

48Cancer Epidemiology Division, Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

49Centre for Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, the University of Melbourne, Carlton, VIC, Australia

50Physical Activity Laboratory, Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

51Researcher, Uruguay

52Early Start, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, Australia

53Sport and Recreation Department, Sports and Recreation Commission, Harare, Zimbabwe

54University of Colombo, Colombo, Sri Lanka

55University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, Barbados

56Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada

57Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

58Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

59CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain

60IMDEA Food Institute, CEI UAM+CSIC, Madrid, Spain

61Department of Sport Science, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

62Department of Sport Science, Wolaita Sodo University, Sodo, Ethiopia

63Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning, Natural Learning Initiative, College of Design, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA

64Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Belgrade, Beograd, Serbia

65SGH Warsaw School of Economics, Warszawa, Poland

66Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Kamuzu University of Health Sciences, Blantyre, Malawi

67Research Centre for Health through Physical Activity, Lifestyle and Sport (HPALS), Division of Physiological Sciences, Department of Human Biology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

68Mary MacKillop Institute for Health Research, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

69School of Public Health, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

70School of Kinesiology & Health Studies, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

71University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

72Universidad Nacional de Asunción, San Lorenzo, Paraguay

73Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, The University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé, Cameroon

74Faculty of Science and Education, University of Mostar, Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina

75Escuela de Educación Física y Deportes, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, Costa Rica

76Escuela de Ciencias del Movimiento Humano y Calidad de Vida, Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica, Heredia, Costa Rica

77Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

78School of Physiotherapy, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia

79Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Güven Health Group, Turkey

80Department of Health Sciences, Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

81Department of Child and Adolescent Health, Institute of Mother and Child, Warszawa, Poland

82School of Nursing and Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences and Veterinary Medicines, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

83College of Health Science, Dong-A University, Busan, Korea

84Tanzania Food and Nutrition Center, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

85School of Physical Therapy, Facultad de Medicina Clínica Alemana, Universidad del Desarrollo, Santiago, Chile

86Department of Health Psychology and Research Methodology, Faculty of Medicine, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Kosice, Slovakia

87PDU EFISAL, Centro Universitario Regional Noreste, Universidad de la República, Rivera, Uruguay

88Nutrition Department, Pitie-Salpetriere Hospital, Sorbonne University, Paris, France

89Faculty of Health Sciences and Sports, Macao Polytechnic University, Macao SAR, China

90Faculty of Kinesiology, Sport, & Recreation, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

91Public Health Wales NHS Trust, Wales

92Research Center in Physical Activity, health and Leisure (CIAFEL), Faculty of Sports-University of Porto (FADEUP) and Laboratory for Integrative and Translational Research in Population Health (ITR), Porto, Portugal

93Faculty of Physical Culture, Palacký University Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic

94China National Center for Food Safety Risk Assessment, Beijing, China

95Faculty of Science and Sport, University of Technology, Kingston, Jamaica

96Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

97Age Institute, Finland

98Directeur Technique Fédération de Basket Mauritanie, Mauritania

99Instructeur FIBA des Entraineurs, Africa

100Ambassadeur ITK de l’Univesrsité de Leipzig, Germany

101Urban Health Collaborative; and Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA

102Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences, Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

103Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

104Department of Precision Health, Luxembourg Institute of Health, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Luxembourg

105Department of Kinesiology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

106University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines

107Centro Universitário do Distrito Federal (UDF), Brasília, Brazil

108Department of Food Science and Nutrition, College of Agricultural and Marine Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman

109Leaders Development Institute, Ministry of Sport, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

110Dirección de Planificación, Ministerio de Salud, San José, Costa Rica

111Division of Physiotherapy, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden

112Telethon Kids Institute, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

113Centro de Acción Urbana, Comunitaria y Empresarial (CAUCE), UPR-Recinto de Rio Piedras, San Juan, Puerto Rico

114Department of Biomedical Engineering, Sylvan Adams Sports Institute, School of Public Health, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

115Physical Education and Sports, AAB Collage, Kosovo Polje, Kosovo

116Organisation and Economy, Józef Piłsudski University of Physical Education in Warsaw, Warszawa, Poland

117Human Potential Centre, School of Sport and Recreation, Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

118Department of Physical Therapy, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

119Department of Physical Therapy and Health Rehabilitation, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Majmaah University, Majmaah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

120Physical Activity for Health Research Centre, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland

121Department of Sport and Exercise Science, South East Technological University, Waterford, Ireland

122Health Promotion Centre, Ministry of Health, Brunei Darussalam

123Cancer Control Office, King Hussein Cancer Center, Amman, Jordan

124Grupo Interno de Trabajo Actividad Física del Ministerio del Deporte de Colombia, Colombia

125Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University, Salaya, Thailand

126Cardiology Society, Uruguay

127Facultad de Medicina Humana, Centro de Investigación del Envejeci-miento (CIEN), Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Lima, Peru

128Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Cientifica del Sur, Lima, Peru

129Instituto Universitario YMCA miembro de la Coalición Mundial de Universidades YMCA, Argentina

130Health Policy and Management, Global Leadership University, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

131University Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté), Lausanne, Switzerland

132Ministry of Health, Victoria, Republic of Seychelles

133Department of Physiological Sciences, Faculty of Medicine of Agostinho Neto University, Luanda, Angola

134Department of Public Health and Welfare, Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland

135Thailand Physical Activity Knowledge Development Centre, Salaya, Thailand

136University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana

137Health-Enhancing Physical Activity Focal Point, Hungary

138Numed, Dominican Republic

139Physical Education Department, Universidad Nacional Experimental Rafael María Baralt, Cabimas, Venezuela

140Physical Education Department, Universidad del Zulia, Maracaibo, Venezuela

141Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Duhok, Duhok, Iraq

142Self-Development Department, Deanship of Preparatory Year, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

143Researcher, States of Guernsey

144Sports Science Unit, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

145Comisión Honoraria para la Salud Cardiovascular, Montevideo, Uruguay

146Department of Physical Therapy, Anton de Kom University of Suriname, Tammenga, Suriname

147Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago

148Centre for Sport and Exercise Sciences, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

149Department of Sport Physiology, Marvdasht Branch, Islamic Azad University, Marvdasht, Iran

150Head Physical Activity and Obesity Prevention, Centre for Chronic Disease Control, New Delhi, India

151Indian Institute of Public Health-Delhi, Public Health Foundation of India, Gurgaon, India

152Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

153National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups, Ministry of Health, Jakarta, Indonesia

154Department of Movement and Sports Sciences, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

155Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition (IPAN), Deakin University, Geelong, VIC, Australia

156Institute of Human Movement Science, Sport and Health, University of Graz, Graz, Austria

157The Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA), Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

158Department of Food Science and Technology, College of Agriculture, Animal Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, University of Rwanda, Nyagatare, Rwanda

159Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Centre for Public Health, Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria

160School of Health and Medical Sciences and Centre for Health Research, University of Southern Queensland, Ipswich, QLD, Australia

161Division of Exercise Science and Sports Medicine, Department of Human Biology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

162National Cancer Institute, Hanoi Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam

163Department of Public Health, University of Health Sciences, Vientiane, Lao People’s Democratic Republic

164HEPA Macedonia National Organisation for the Promotion of Health-Enhancing Physical Activity at the WHO HEPA Europe, North Macedonia

165Health Promotion Strategist, Pacific Portfolio, Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand, Auckland, New Zealand

166Department of Physical Education, Exercise and Sports Science, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

167National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, The Netherlands

168Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Clinic, Patras General University Hospital, Patras, Greece

Footnotes

Author affiliations and ORCID links can be found in the Appendix to the article.

References

- 1.Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(10):e1077–e1086. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warburton DER, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2017;32(5):541–556. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saunders TJ, McIsaac T, Douillette K, et al. Sedentary behaviour and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2020;45(10 suppl 2):S197–S217. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2020-0272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stockwell S, Trott M, Tully M, et al. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2021; 7(1):e000960. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez Varela A, Sallis R, Rowlands Av, Sallis JF. Physical inactivity and COVID-19: when pandemics collide. J Phys Act Health. 2021; 18(10):1159–1160. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2021-0454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sallis R, Young DR, Tartof SY, et al. Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: a study in 48 440 adult patients. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55(19):1099–1105. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowlands Av, Kloecker DE, Chudasama Y, et al. Association of timing and balance of physical activity and rest/sleep with risk of COVID-19: a UK biobank study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(1):156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.10.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobelo F, Bienvenida A, Leung S, et al. Clinical, behavioural and social factors associated with racial disparities in COVID-19 patients from an integrated healthcare system in Georgia: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e044052. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramírez Varela A, Hallal P, Pratt M, et al. Global Observatory for Physical Activity (GoPA!): 2nd Physical Activity Almanac, Global Observatory for Physical Activity (GoPA!). Published 2021. https://indd.adobe.com/view/cb74644c-ddd9-491b-a262-1c040caad8e3. Accessed February 2, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Global Observatory for Physical Activity. GoPA! Global Observatory for Physical Activity. Published 2022. https://new.globalphysicalactivityobservatory.com/goals/. Accessed June 11, 2022.

- 11.Ramírez Varela A, Pratt M, Powell K, et al. Worldwide surveillance, policy and research on physical activity and health: the Global Observatory for Physical Activity - GoPA! J Phys Act Health. 2017;14(9):701–709. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2016-0626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramírez Varela A, Pratt M, Borges C, et al. Global Observatory for Physical Activity (GoPA!): 1st Physical Activity Almanac, Global Observatory for Physical Activity (GoPA!). Published 2016. https://indd.adobe.com/view/f8d2c921-4daf-4c96-9eaf-b8fb2c4de615

- 13.WHO. The Global Health Observatory. World Health Organization. Published 2014. https://www.who.int/data/gho. Accessed September 1, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The World Bank. World Bank. Published 2014. http://data.worldbank.org/country. Accessed September 1, 2015.

- 15.Our World in Data. Our World in Data. 2017. https://ourworldindata.org. Accessed April 1, 2017.

- 16.The DHS Program. Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). 2019. https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/Survey-Types/DHS.cfm. Accessed February 1, 2022.

- 17.WHO. National STEPS Reports. 2017. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/pages/monitoring-and-surveillance/tools-and-initiatives/who-stepwise-approach-to-surveillance. Accessed February 1, 2022.

- 18.WHO. World Health Survey (WHS). WHO multi-country studies data Archive. 2019. https://apps.who.int/healthinfo/systems/surveydata/index.php/catalog/whs. Accessed February 1, 2022.

- 19.Klepac Pogrmilovic B, Ramirez Varela A, Pratt M, et al. National physical activity and sedentary behaviour policies in 76 countries: availability, comprehensiveness, implementation, and effectiveness. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01022-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramírez Varela A, Nino Cruz GI, Hallal P, et al. Global, regional, and national trends and patterns in physical activity research since 1950: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01071-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramírez Varela A, Salvo D, Pratt M, et al. Worldwide use of the first set of physical activity country cards: the Global Observatory for Physical Activity - GoPA! Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0663-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag; 2016. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramirez Varela A, Klepac Pogrmilovic B, Hallal PC, et al. Global physical activity. In: Siefken K, Ramirez Varela A, Waqanivalu T, Schulenkorf N, eds. Physical Activity in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Routledge; 2021: 11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellew B, Nau T, Smith BJ, Pogrmilovic BK, Pedišić Ž, Bauman AE. Physical activity policy actions. In: Siefken K, Ramirez Varela A, Waqanivalu T, Schulenkorf N, eds. Physical Activity in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Routledge; 2021: 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedišić Ž, Craig CL, Bauman AE. Physical activity surveillance in the context of low- and middle-income countries. In: Siefken K, Ramirez Varela A, Waqanivalu T, Schulenkorf N, eds. Physical Activity in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Routledge; 2021: 90–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding D, Ramirez Varela A, Bauman AE, et al. Towards better evidence-informed global action: lessons learnt from the Lancet series and recent developments in physical activity and public health. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(8):462–468. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosdriesz JR, Witvliet MI, Visscher TL, Kunst AE. The influence of the macro-environment on physical activity: a multilevel analysis of 38 countries worldwide. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):110. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding D, Adams MA, Sallis JF, et al. Perceived neighborhood environment and physical activity in 11 countries: do associations differ by country? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):57. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cameron AJ, van Stralen MJM, Kunst AE, et al. Macroenvironmental factors including GDP per capita and physical activity in Europe. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(2):278–285. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31826e69f0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(12):1793–1812. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00150-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giles-Corti B, Timperio A, Bull F, Pikora T. Understanding physical activity environmental correlates: increased specificity for ecological models. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2005;33(4):175–181. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200510000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. 2012;380(9838):258–271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramirez Varela A. Worldwide Research, Surveillance and Policy on Physical Activity: The Global Observatory for Physical Activity - GoPA! [Pelotas]. Universidade Federal de Pelotas; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sallis JF, Bull F, Guthold R, et al. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1325–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30581-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2022. World Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 36.United Nations General Assembly. Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases (2011 Sept. 19). United Nations. Published 2012. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/N11/497/77/PDF/N1149777.pdf?OpenElement. Accessed July 5, 2022.

- 37.Bellew W, Smith BJ, Nau T, Lee K, Reece L, Bauman A. Whole of systems approaches to physical activity policy and practice in Australia: the ASAPa project overview and initial systems map. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17(1):68–73. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2019-0121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanley I, Neumann-Podczaska A, Wieczorowska-Tobis K, et al. Health surveillance indicators for diet and physical activity: what is available in European data sets for policy evaluation? Eur J Public Health. 2022;32(4):571–577. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckac043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pratt M, Ramirez Varela A, Salvo D, Kohl HW III, Ding D. Attacking the pandemic of physical inactivity: what is holding us back? Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(13):760–762. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization. NCD Country Capacity Survey. Noncommunicable disease surveillance, monitoring and reporting, The Global Health Observatory. Published 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/ncds/surveillance/monitoring-capacity/ncdccs. Accessed September 25, 2022.

- 42.Whiting S, Mendes R, Morais ST, et al. Promoting health-enhancing physical activity in Europe: surveillance, policy development and implementation 2015–2018. Health Policy. 2021;125(8):1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heymann D, Kickbusch I, Ihekweazu C, Khor SK. A new understanding of global health security: three interlocking functions. Published 2021. https://globalchallenges.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/A-new-understanding-of-global-heath-security-UPDATED.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2022.

- 44.Docquier F. The brain drain from developing countries. IZA World of Labor. 2014;31:1–10. doi: 10.15185/izawol.31 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li R, Ruiz F, Culyer AJ, Chalkidou K, Hofman KJ. Evidence-informed capacity building for setting health priorities in low- and middle-income countries: a framework and recommendations for further research. F1000Res. 2017;6:231. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.10966.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siefken K, Varela AR, Waqanivalu T, Schulenkorf N. Physical Activity in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Routledge; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmed A, Daily JP, Lescano AG, Golightly LM, Fasina A. Challenges and strategies for biomedical researchers returning to low- and middle-income countries after training. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(3):494–496. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lambert EV, Kolbe-Alexander T, Adlakha D, et al. Making the case for ‘physical activity security’: the 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour from a Global South perspective. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1447–1448. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bigna JJ, Noubiap JJ. The rising burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10): e1295. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30370-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gouda HN, Charlson F, Sorsdahl K, et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(10):e1375–e1387. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30374-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Global Observatory for Physical Activity, Oyeyemi A. The Global Observatory for Physical Activity - GoPA!: Africa Policy Brief. Published 2021. https://new.globalphysicalactivityobservatory.com/Documents/Policy%20Brief%20AFRO.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- 52.Oyeyemi AL, Oyeyemi AY, Omotara BA, et al. Physical activity profile of Nigeria: implications for research, surveillance and policy. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:175. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.175.12679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tremblay MS, Gonzalez SA, Katzmarzyk PT, Onywera VO, Reilly John J. Physical activity report cards: active healthy kids global alliance and the lancet physical activity observatory. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(3):297–298. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]