Abstract

The aim of this study was to provide a new effective carrier for rescuing the sensitivity of drug‐resistant in breast cancer cells. Nano‐gold micelles loaded with Dox and Elacridar (FP‐ssD@A‐E) were chemically synthesised. With the increase in the amount of Dox and Elacridar, the encapsulation rate of FP‐ssD@A‐E gradually increased, and the drug loading rate gradually decreased. FP‐ss@A‐E had a sustained‐release effect. Dox, Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E significantly improved cell apoptosis, in which, FP‐ssD@A‐E was the most significant. FP‐ssD@A‐E significantly decreased the cell viability and improved the Dox uptake. The levels of VEGFR‐1, P‐gp, IL‐6, and i‐NOS were significantly decreased after Dox, Dox + Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E treatment. It was worth noting that FP‐ssD@A‐E had the most significant effects. The prepared FP‐ssD@A‐E micelles, which were spherical in shape, uniform in particle size distribution, and had good drug loading performance and encapsulation efficiency.

Keywords: breast cancer, doxorubicin, drug loaded hybrid micelles, elacridar, gold nanoparticles

(1) FP‐ss@A‐E had a sustained‐release function for Dox. (2) FP‐ss@A‐E improved apoptosis of breast cancer cells. (3) FP‐ss@A‐E improves the intake of Dox and decreases cytokine levels.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignant tumours [1]. According to the latest global cancer burden data released by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization in 2020, there are 2.26 million new cases of breast cancer worldwide, surpassing the 2.2 million cases of lung cancer, making it the world's largest cancer [2]. The current treatment methods for breast cancer mainly include early surgery supplemented by chemotherapy, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, and biological immunotherapy [3]. However, antitumour drugs that lack cell selectivity have caused serious damage to normal human cells [4]. At the same time, failure to accumulate effective therapeutic doses of chemotherapeutic drugs in the local area of the tumour leads to tumour resistance.

Nanotechnology has unique advantages in the targeted delivery of antitumour drugs and tumour treatment [5]. Nanoparticles have a variety of characteristics in vivo, including biocompatibility, targeting, invisibility, sustained release, main body stability, and surface modification [6]. Therefore, nanotechnology can maximise local tumour accumulation, improve the high penetration and retention effects of solid tumours, and reverse tumour drug resistance [7]. Thereinto, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have been widely used in many medical aspects, such as disease diagnosis, drug detection, and cell imaging [8]. AuNPs have a certain biological activity, photothermal effect, which can also be used as a carrier to load drugs [9]. By forming the gold‐sulphur (Au‐S) coordination bond, the sulfhydryl‐containing compound can self‐assemble on the surface of the nanogold to obtain stable nanoparticles, thereby loading the drug on the surface of the nano‐gold [10]. Furthermore, AuNPs have a relatively large specific surface area for loading a large number of drugs [11]. At present, gold nanoparticles have been widely researched and applied as carriers of chemical drugs, protein drugs, and gene drugs.

Elacridar (ELC) is a third‐generation P‐glycoprotein (P‐gp) inhibitor [12]. This type of reversal agent is a high‐efficiency, low‐toxicity, and specific multidrug resistance (MDR) reversal agent that acts on P‐gp [13]. Besides, doxorubicin (Dox) is a cycle non‐specific anticancer chemotherapeutic drug that affects cells in all phases [14]. Its mechanism of action is mainly to directly act on DNA, which inhibits the synthesis of DNA and the synthesis of RNA [15]. It also has the effect of destroying the structure and function of cell membranes [16]. Doxorubicin has a strong cytotoxic effect, and carcinogenic and mutagenic effects [17]. When combined with Dox, although drug interactions increase the toxicity of the blood system, ELC can make doxorubicin have an ideal clinical treatment effect for most tumour types.

In this study, a metal‐organic complex drug‐loaded nanomicelle drug that reverses breast cancer resistance was designed and prepared. The nanomicelle drug was loaded with doxorubicin and Elacridar (FP‐ssD@A‐E) as the main pharmacological ingredients. The gold nanoparticles were loaded into the micelle drug by the electrostatic attraction of disulphide bonds and gold nanoparticles. FP‐ssD@A‐E might be a new effective method for decreasing cell toxicity and rescuing the sensitivity of drug‐resistant breast cancer cells.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Cysteine (NH2‐SS‐NH2) was obtained from PerkinElmer. Dichloromethane and dimethylformamide were purchased from Sinopharm. Triethylamine, methacryloyl chloride, Copper(I) bromide, ethyl 2‐bromoisobutyrate, 1,2,3,4‐tetrahydronaphthalene, oleylamine, HAuCl4•3H2O, toluene, Elacridar, and trifluoroacetic acid were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. Tert‐butyl methacrylate and ligand N,N,N′,N′,N″‐pentamethyldiethylenetriamine were obtained from Aladdin (Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd.).

2.2. Construction of dual drug‐loaded micelles

Cystine (NH2‐SS‐NH2) (PerkinElmer) was placed in the dichloromethane (DCM, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) reagent, and 1.5 equivalents of triethylamine (Sigma‐Aldrich) were added to the equilibrium system. Then, four equivalents of methacryloyl chloride (Sigma‐Aldrich) were added dropwise under ice bath conditions and stirred at room temperature for 12 h to obtain MMA‐SS‐NH2. MMA‐SS‐NH2 and DOX (Chemex Export‐Import) were dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) in sequence at a ratio of 1:2, triethylamine was added as a catalyst, and MMA‐SS‐Dox was obtained by reacting at room temperature for 24 h. After removing the polymerisation inhibitor, tert‐butyl methacrylate (tBMA, Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd.) and the ligand N,N,N′,N'′,N″‐pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA, Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd.) were mixed and dissolved in a round bottom flask. After deoxygenating with argon for 30 min, the Copper(I) bromide (CuBr; Sigma‐Aldrich) was purified and dissolved in a two‐necked flask. The constant‐pressure titration funnel was used to drop the deoxygenated mixed solution. After stirring for 10 min, the solution was transferred to an oil bath at 85°C, the initiator ethyl 2‐bromoisobutyrate (EBriB, Aldrich) was added, and the reaction was carried out for 2 h to obtain P(tBMA). Then the MMA with the inhibitor was removed and the prepared MMA‐SS‐Dox was added, and the reaction was continued for 4 h to obtain P(tBMA)‐P(MMA‐SS‐Dox). Twenty‐five millilitres ml of 1,2,3,4‐tetrahydronaphthalene (Sigma‐Aldrich), 25 ml of oleylamine (Sigma‐Aldrich), and 0.25 g of HAuCl4•3H2O (Sigma‐Aldrich) were stirred at 25°C and mixed magnetically for 10 min. The mixture was reacted at 25°C for 1 h, then 50 ml of absolute ethanol was added to cover the AuNPs, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 7 min, and then dispersed in 50 ml of toluene to obtain uniform AuNPs. Then, P(tBMA)‐P(MMA‐SS‐DOX) was dissolved in toluene (Sigma‐Aldrich), added to the toluene solution containing AuNPs and Elacridar (Sigma‐Aldrich), and stirred for 48 h. After adding 50 ml of water, the solution was centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 2 h, repeated three times, and freeze‐dried to obtain P(tBMA)‐P(MMA‐SS‐DOX)@AuNPs‐Elacridar. P(tBMA)‐P(MMA‐SS‐DOX)@AuNPs‐Elacridar was dissolved in DCM. After ultrasonic dispersion, trifluoroacetic acid (Sigma‐Aldrich) was slowly added dropwise to the solution and stirred for 2 h in an ice bath environment to obtain P(MAA)‐P(MMA‐SS‐Dox)@AuNPs‐Elacridar. Finally, excess triethylamine and two equivalents of FA‐mPEG‐NH2 were added and stirred at room temperature for 8 h to obtain FA‐mPEG‐P(MMA‐SS‐Dox)@AuNPs‐Elacridar (FP‐ssD@A‐E). For FP‐ss@AuNPs, DOX and Elacridar did not participate in the reaction.

2.3. Characterisation of chemical structure

The Nicolet 6700 FT‐IR Fourier Infrared Absorption Spectrometer was used to measure the Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT‐IR) with the range of 500–4000 cm−1. The sample was diluted and compressed with KBr (Sigma‐Aldrich).

The sample was ultrasonically dispersed in absolute ethanol, and the ultraviolet‐visible spectrum (UU‐Vis) data was recorded with an Hp‐6010 spectrophotometer.

The X‐ray diffraction (XRD) pattern was detected by Brucker AXS D8 Advance, using Cu‐Kα rays (40 kV, 300 mA), and the test range was 30–90°.

2.4. Morphology analysis of dual drug‐loaded nanomicelles

The transmission electron microscope (TEM) test was carried out on the FEI Tecnai G2 F20 S‐Twin high‐resolution TEM. The sample was dispersed by ultrasonic and then picked up and dried with a copper net.

The dynamic laser light scattering (DLS) test was performed with the Brookhaven Plus 90 nm laser particle size, the sample concentration was 1 mg/ml, and the ultrasonic dispersion was performed.

The zeta potential of the sample was measured by a Malvern laser particle size analyser (Zetasizer Nano‐ZS90). Each sample was filtered with a 0.45 μm microporous membrane before testing. The sample concentration was 1.0 mg/ml.

Stabilities of gold‐based micelles were studied over 72 h at 25°C in aqueous solution at 0.9% w/w NaCl. Spectra were recorded between 220 and 450 nm.

2.5. Standard curve of Dox and Elacridar

The absorbance of Dox (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 µg/ml) and Elacridar (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, and 0.1 μg/ml) at 480 nm were detected using fluorescence spectrophotometer. Then, the standard curves of Dox and Elacridar were drawn. The solvent used was DMSO and the molar extinction coefficient was 4.1 × 109 cm−1 M−1 at 480 nm.

2.6. Drug loading rate and encapsulation rate

The nanomicelles containing different amounts of Dox and Elacridar were obtained, dissolved in a quantitative dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution, and diluted to a certain concentration. According to the standard curve of Dox and Elacridar, the content of Dox and Elacridar was calculated, and the drug loading (DL) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) of the nanomicelles were then calculated.

2.7. Drug release of Dox and Elacridar in dual drug‐loaded micelles

Dual drug‐loaded nanomicelles containing Dox (0.5 mg/ml) and Elacridar (0.5 mg/ml) were dispersed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4) and placed in a dialysis bag. Then, the dialysis bag was placed in a 200 ml release medium (pH = 7.4, PBS), and the release experiment was performed in a constant temperature shaker at 37°C. Samples were taken at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h, and the same amount of isothermal release medium was added at the same time. At the end of treatment, the supernatant was removed, the cells were washed with ice‐cold PBS and lysed with 1% Triton‐X in PBS. Dox and Elacridar concentrations in the cell lysates were measured with SpectraMax Gemini XS microplate fluorometer (Molecular Devices), excited at 478 nm and emitted at 594 nm. The content of Dox and elacridar in the sample was determined, and the cumulative release rate was calculated. In addition, the raw materials of Dox and Elacridar were used as controls to determine the cumulative release rate. Release kinetics of Dox and Elacridar were measured by analysing fluorescence images. The rate of release was determined at 42°C using the millifluidic. Release rates were fastest for Dox, followed in order by Elacridar. Nearly 100% of Dox was released, the most of all the compounds. Release after 6 s measured using the millifluidic method was highest for Dox, followed by Elacridar. After 10 min (measured with the cuvette method), release was highest for Dox, followed by Elacridar.

2.8. Cell culture and treatment

Human breast cell lines HBL‐100, MCF‐7, and MCF‐7/MDR were purchased from the Stem Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose medium containing 10% foetal bovine serum and 50 IU/L penicillin and streptomycin. The cells were placed in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 saturated humidity. The medium was changed every other day, and the cells were passaged in the logarithmic growth phase. Based on groups, the cells were treated with different concentrations of Dox, Elacridar, FP‐ss‐AuNPs, FP‐ss‐D@A‐E, and Free Dox + Elacridar.

2.9. Cell Counting Kit‐8 (CCK8) assay

The cells in the logarithmic growth phase are routinely digested and then plated in a 96‐well plate and placed in an incubator overnight. The number of cells inoculated per well was about 2500 cells, and the fusion degree is about 20% after adherence. Different amounts of FP‐ss@AuNPs, Dox, FP‐ss‐D@A‐E, and Elacridar were treated with the cells. CCK8 detection was performed at 2, 8, 24, and 48 h. The detection method was briefly as follows. The original medium in the 96‐well plate was discarded, and 100 μl of complete medium containing 10% CCK8 (Abcam) was added to each well. After incubating in a 37°C incubator for 1 h, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The cell survival rate was the ratio of the light absorption value of the experimental group and the light absorption value of the control group. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was calculated by plotting the cell survival rate and the logarithm of the drug dose.

2.10. Flow cytometry assay

Cells were placed in culture flasks. Each flask was 2.7 ml and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. The cell lines were divided into five groups, including FP‐ss@AuNPs, free Dox, Elacridar, free Dox + Elacridar, and FP‐ssD@A‐E groups, and the culture was continued for 24 h after treatment. The adherent cells were digested with 0.25% pancreatin and 0.02% Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid (EDTA). The cell suspension was obtained, centrifuged, washed, and then fixed with prechilled 70% ethanol for 24 h. After discarding the fixative, the cells were resuspended in PBS for 5 min, and apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry (BD FACSVia™ System).

2.11. Drug‐uptake assay

Cells were inoculated on a 12‐well plate tissue culture slide to a density of 5 × 104 per well and allowed to grow overnight. The three groups of cells were treated with the corresponding drugs, and after incubating for 6 h, the culture medium was discarded. After washing three times with PBS, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and stained with DAPI, DIC, and Merge to observe the DOX content in the cells.

2.12. Determination of cytokine level

The dual drug‐loaded imaging micelles were incubated with HBL‐100, MCF‐7, MCF‐7/MDR cell lines for 24 h, and the levels of vascular endothelial cell growth factor receptor‐1 (VEGFR‐1), Permeability glycoprotein (P‐gp), interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and i‐Nitric Oxide Synthase (i‐NOS) were detected with an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. The brief steps were as follows. Cells were cultured in groups and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. The cells in the 96‐well culture plate were centrifuged at 4°C and centrifuged at 200 × g for 15 min. The supernatant of each well was transferred to a 200 μL sterile centrifuge tube and stored at −80°C for later use. The standard is proportionally diluted to the required concentration. Thirty minutes before use, the concentrated biotinylated antibody and concentrated enzyme conjugate provided in the kit were, respectively, diluted into biotinylated antibody working solution and enzyme conjugate working solution (1:100). The cell supernatant sample was taken out of the refrigerator at −80°C in advance and placed in the refrigerator at 4°C, and was equilibrated at room temperature before use. The specific steps of the experiment were carried out according to the instructions of the ELISA kit (R&D Systems). The average A value of 3 replicate wells for each sample was calculated. According to the linear regression equation obtained from the standard, the content of the sample in the cell culture supernatant was calculated.

2.13. Statistical analysis

All results were processed by SPSS 11. 0 software and measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD. One‐way analysis of variance was used for comparison three or more groups, SNK test was used for pairwise comparison. p < 0.05 represented that the difference was statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Chemical structure characterisation of dual drug‐loaded nanomicelles

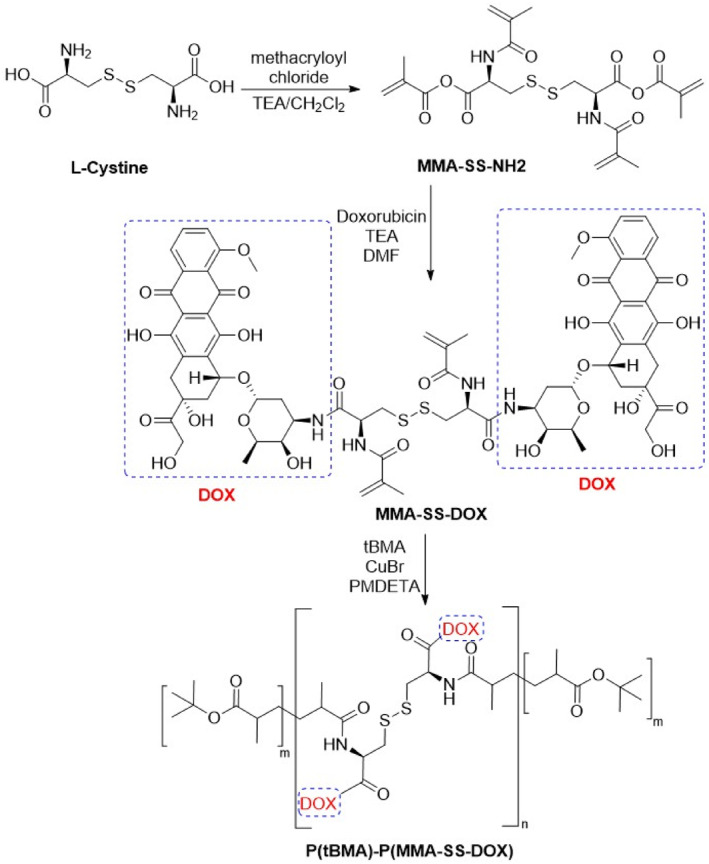

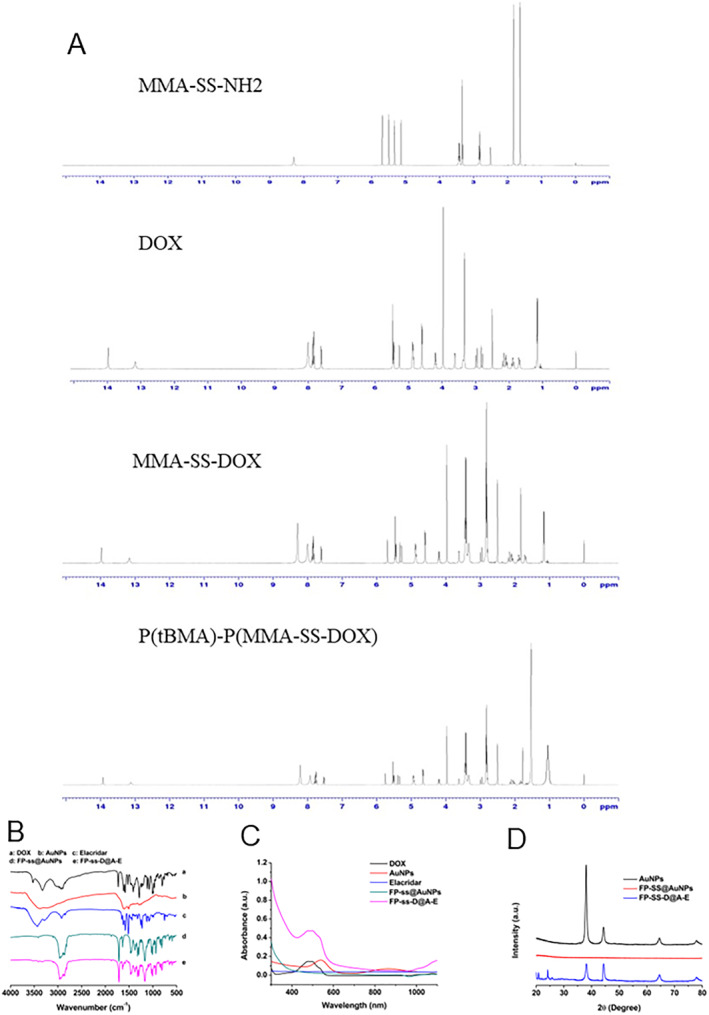

Scheme 1 exhibited the preparation of P(tBMA)‐P(MMA‐SS‐Dox). It was shown that the 1H NMR characterisation of MMA‐SS‐NH2, DOX, MMA‐SS‐DOX, and P(tBMA)‐P(MMA‐SS‐Dox) in Figure 1a. Chemical structure characterisation including FT‐IR, UU‐Vis, and XRD data of DOX, AuNPs, Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E were detected. The infrared spectrum of the standard sample of doxorubicin showed characteristic peaks of doxorubicin at 816, 1117, 1211, 1581, 1732, and 2921 cm−1. Elacridar was with characteristic peaks at 1275, 1496, and 3482 cm−1. When doxorubicin and Elacridar were loaded on the nanoparticles, the characteristic absorption of Elacridar and doxorubicin appeared at the same time. However, the peak at 1581 cm−1 was shifted, which might be due to the formation of disulphide bonds during the loading process of doxorubicin (Figure 1b). Through ultraviolet‐visible absorption spectra, the light absorption values of Dox, AuNPs, Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E under different wavelength conditions are obtained (Figure 1c). The XRD results showed that free AuNPs had significant crystal peaks. The spectrum of blank micelles did not show the crystal peaks of AuNPs. The crystal peaks of the dual‐drug carrier were not obvious. The AuNPs and the drug might exist in a molecular or amorphous state, indicating that the drug was encapsulated in the nanogold micelles (Figure 1d).

Scheme 1.

The preparation of P(tBMA)‐P(MMA‐SS‐DOX)

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structure characterisation of dual drug‐loaded nanomicelles. (a) 1H NMR of MMA‐SS‐NH2, DOX, MMA‐SS‐DOX, and P(tBMA)‐P(MMA‐SS‐Dox). (b) FTIR spectra of DOX, AuNPs, Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E. (c) The light absorption values of DOX, AuNPs, Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E under different wavelength conditions. (d) The XRD spectra.

3.2. Morphology analysis of dual drug‐loaded nanomicelles

Morphology analysis of AuNPs, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E were detected. The gold micelles were almost spherical. It could be seen that the gold nanoparticles were wrapped in the micelles. The volume of blank micelles and drug‐loaded micelles did not change significantly (Figure 2a). Based on the results, the drug was loaded in the hydrophobic core. DLS analysis results showed that the size of gold nanoparticles was mostly distributed at 13.2 nm, and the size of blank micelles was 220.9 nm. After loading AuNPs and Elacridar, the particle size distribution was wider, and the average particle size was about 251.6 nm (Figure 2b). The zeta potentials of gold nanoparticles, blank micelles, and dual drug‐loaded micelles are −4.2, 10.3, and −12.6 mV respectively (Figure 2c). The results also further illustrated that the drug was encapsulated in the nano‐gold micelles. Stability of AuNPs, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E was 90, 95, and 100 mol/mol in aqueous solution at 0.9% w/w NaCl was monitored by UV–vis spectroscopy over time.

FIGURE 2.

Morphology analysis of dual drug‐loaded nanomicelles. (a) The transmission electron microscope (TEM) test. (b) The dynamic laser light scattering (DLS) assay. (c) The zeta potential of AuNPs, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E.

3.3. Drug release of dual drug‐loaded nanomicelles

Ultraviolet‐visible spectrophotometry was used to calculate micelle DL. The content and light absorption curves were fitted according to the drug concentration, absorbance, and fluorescence intensity. The regression equation of the standard curve of DOX was y = 0.65x + 0.00627, and the regression equation of the standard curve of Elacridar was y = 349721x − 7.96 (Figure 3a). With the increase in the amount of Elacridar and DOX, the encapsulation rate of FP‐ssD@A‐E gradually increased, and the DL rate gradually decreased (Figure 3b). Interestingly, DOX and Elacridar released more than 95% of the drug within 5 h in vitro. However, DOX in FP‐ss@A‐E was released for 50 h, and Elacridar was released for 23 h. Therefore, it was suggested that FP‐ss@A‐E had a sustained‐release effect (Figure 3c).

FIGURE 3.

Drug release of dual drug‐loaded nanomicelles. (a) The regression equation of the standard curve of DOX was y = 0.65x + 0.00627, and the regression equation of the standard curve of Elacridar was y = 349721x − 97.96. (b) With the increase in the amount of Elacridar and DOX, the encapsulation rate of FP‐ssD@A‐E gradually increased, and the drug loading rate gradually decreased. (c) FP‐ss@A‐E had a sustained‐release effect.

3.4. Cell cytotoxicity in vitro

As shown in Figure 4a, FP‐ss@AuNPs nanoparticles were non‐cytotoxic. Free Dox, Elacridar, and FP‐ssD@A‐E have a certain degree of toxicity to HBL‐100, MCF‐7, and MCF‐7/MDR cells, and the cell survival rate is dose‐dependent (Figure 4b–e). The differences in cell proliferation of HBL‐100, MCF‐7, and MCF‐7/MDR in each group at 2, 8, 24, and 48 h were evaluated. The results showed that after 24 h, the cell viability of the FP‐ss‐A group was significantly higher than the other group, and the cell viability of FP‐ssD@A‐E was the lowest among all groups (Figure 4f–h). Thereby, FP‐ssD@A‐E effectively decreased the cell viability.

FIGURE 4.

Cell cytotoxicity in vitro. (a) FP‐ss@AuNPs nanoparticles were non‐cytotoxic. (b−e) Free Dox, Elacridar, and FP‐ssD@A‐E have dose‐dependent toxicity to HBL‐100, MCF‐7, and MCF‐7/MDR cells. Compared with HBL‐100 group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Compared with MCF‐7 group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01. (f−h) The differences in cell proliferation of HBL‐100, MCF‐7, and MCF‐7/MDR in each group at 2, 8, 24, and 48 h. Compared with free Dox group, *p< 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3.5. FP‐ssD@A‐E improved cell apoptosis

The effects of free Dox, Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E on apoptosis of HBL‐100, MCF‐7, and MCF‐7/MDR cells were detected. As shown in Figure 5, Dox, Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E significantly improved cell apoptosis. Among these groups, FP‐ssD@A‐E was the most significant.

FIGURE 5.

FP‐ssD@A‐E improved cell apoptosis

The effects of free Dox, Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ssD@A‐E on apoptosis of HBL‐100, MCF‐7, and MCF‐7/MDR cells were detected. Compared with FP‐ss@AuNPs, ***p < 0.001.

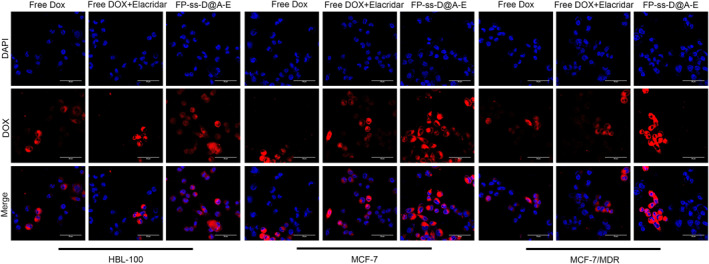

3.6. Uptake of FP‐ssD@A‐E

As shown in Figure 6, the blue fluorescence represented the nucleus stained with Hoechst33342, while the red fluorescence represented the dye‐labelled Dox. The red fluorescence was concentrated in the nucleus, indicating that Dox had been absorbed by the cell and most of it was concentrated in the nucleus. More importantly, the red fluorescence of the FP‐ssD@A‐E group was significantly higher than that in the free Dox group and free Dox + Elacridar group in HBL‐100, MCF‐7, and MCF‐7/MDR cells. Based on the results, FP‐ssD@A‐E significantly improved the Dox uptake.

FIGURE 6.

FP‐ssD@A‐E significantly improved the Dox uptake.

3.7. Determination of cytokine level

The dual drug‐loaded imaging micelles were incubated with HBL‐100, MCF‐7, MCF‐7/MDR cell lines for 24 h, and the levels of VEGFR‐1, P‐gp, IL‐6, and i‐NOS were detected. As shown in Figure 7, the levels of VEGFR‐1, P‐gp, IL‐6, and iNOS were significantly lower after Dox, Dox + Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ss‐D@A‐E treatment. It was worth noting that FP‐ssD@A‐E had the most significant effects.

FIGURE 7.

FP‐ss@AuNPs decreased cytokine level

The levels of VEGFR‐1, P‐gp, IL‐6, and iNOS were significantly lower after Dox, Dox + Elacridar, FP‐ss@AuNPs, and FP‐ss‐D@A‐E treatment. Among these groups, FP‐ssD@A‐E had the most significant effects. Compared with control group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

4. DISCUSSION

According to the American Cancer Society, about 80% of breast cancer cases were hormone receptor positive, so the incidence of cancer cell metastasis and drug resistance was high [18]. Among the many formation mechanisms of MDR, the most common one was the P‐gp glycoprotein mechanism [19]. P‐gp glycoprotein had an energy‐dependent drug pump function, and its substrates were mostly fat‐soluble, including anthracycline antibiotics such as daunorubicin (Dox) and adriamycin, and plant antibiotics such as vincristine [20, 21].

DOX belongs to the anthracycline antitumour antibiotic, which has certain cardiotoxicity [22]. The current method of reducing the side effects of Dox on the heart is mainly through the application of drug delivery systems to change the biodistribution of doxorubicin [23]. At present, liposomes have been successfully used for the delivery of Dox [24]. Although liposomes change the pharmacokinetics and distribution of Dox in vivo, it has the defect that Dox is not effective. ELC is a third‐generation P‐gp inhibitor that inhibits ABC transporters expression [13]. Previous studies have confirmed that the combination of ELC and chemotherapeutic drugs increased the sensitivity of tumour cells to chemotherapeutic drugs and enhanced the killing effect of drugs [25]. Therefore, FP‐ss@AuNPs nanomicelles were designed in this study to encapsulate Dox and Elacridar, so that the drug could be efficiently and safely targeted to breast cancer cells, and the concentration of the drug in the target cell was increased.

In this study, the drug release assay confirmed that FP‐ss@AuNPs had a better sustained release effect. The in vitro cytotoxicity of FP‐ss@AuNPs was determined by the CCK8 cytotoxicity experiment. It could be seen that its efficacy was better than that of free DOX, indicating that it could be released in tumour cells. Then, the toxicity assay of FP‐ssD@A‐E on cells showed that it reduced the IC50 value of doxorubicin and improved the MDR reversal efficiency of drug‐resistant cells. Besides, FP‐ss@AuNPs increased the Dox uptake of HHBL‐100, MCF‐7, and MCF‐7/MDR, which had the strongest inhibitory effect on breast cancer cells. Therefore, FP‐ss@AuNPs could carry doxorubicin and overcome P‐gp‐mediated MDR.

Importantly, FP‐ss@AuNPs decreased vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR‐1), P‐gp, IL‐6, and iNOS levels in breast cancer cells in this study. The formation of tumour blood vessels depends on the induction and regulation of a variety of related factors. Among them, VEGFR‐1 was specifically expressed on breast cancer cells, and the expression level was significantly higher than other receptors [26]. VEGFR‐1 plays a leading role in VEGF signal transduction and angiogenesis [27]. Furthermore, IL‐6 was mainly produced by a variety of cells such as macrophages, T cells, and B cells, which regulate the growth and differentiation of a variety of cells [28]. It had the function of regulating immune response, acute phase response, and hematopoietic function, and played a critical role in the body's anti‐infection immune response [29]. The increased level of IL‐6 was closely related to the development, MDR, and treatment effect of breast cancer [30]. Besides, MDR was an important reason for the failure of breast cancer chemotherapy, and the overexpression of the MDR1 gene and its product P‐gp protein were the important mechanisms of MDR [31]. Previous studies have shown that in breast cancer, P‐gp promotes the occurrence of MDR by inhibiting the accumulation of drugs in tumour cells and inhibiting the activation of caspase enzymes [32]. Simultaneously, a previous study referred that iNOS activity in tumour animal models was enhanced when MDR occurs [33]. Thereby, FP‐ss@AuNPs regulated blood vessel formation, immune response, and MDR.

5. CONCLUSION

In summary, the FP‐ssD@A‐E micelles were prepared, which were spherical in shape, uniform in particle size distribution, and had good DL performance and EE in this study. Combining the inhibitory effect of ELC on P‐gp protein and the killing effect of DOX on tumours, it achieved better exerted on the therapy of breast cancer.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Liu‐Jing Wen and Jie Zhang designed the experiments. Liu‐Jing Wen performed the experiments, analysed the data, and wrote this manuscript. Yue‐Sheng Wang analysed the data and revised this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report that they have no declarations of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The present study was supported by The Tianjin Municipal Education Commission Scientific Research Plan Project (grant no. 2020KJ145).

Wen, L.‐J. , Wang, Y.‐S. , Zhang, J. : Nano‐gold micelles loaded Dox and Elacridar for reversing drug resistance of breast cancer. IET Nanobiotechnol. 17(2), 49–60 (2023). 10.1049/nbt2.12102

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zheng, J.L. , et al.: Graphene‐based materials: a new tool to fight against breast cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 603, 120644 (2021). 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olsson, A. , Schubauer‐Berigan, M. , Schüz, J. : Strategies of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC/WHO) to reduce the occupational cancer burden. Meditsina Tr. Promyshlennaia Ekol. 61(3), 140–154 (2021). 10.31089/1026-9428-2021-61-3-140-154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Esteva, F. , et al.: Immunotherapy and targeted therapy combinations in metastatic breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 20(3), e175–e186 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meng, G.G. , James, B.R. , Skov, K.A. : Porphyrin chemistry pertaining to the design of anti‐cancer drugs; part 1, the synthesis of porphyrins containing meso‐pyridyl and meso‐substituted phenyl functional groups. Can. J. Chem. 72(9), 2447–2457 (1994). 10.1139/v94-241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lamichhane, S. , Lee, S. : Albumin nanoscience: homing nanotechnology enabling targeted drug delivery and therapy. Arch Pharm. Res. 43(1), 118–133 (2020). 10.1007/s12272-020-01204-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jølck, R. , Andresen, T.L. , Berg, R.H. : Functionalization of self‐organized nanoparticles for biological targeting and active drug release. Catal. Ind. 6, 67–71 (2011) [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li, Y. , et al.: The application of nanotechnology in enhancing immunotherapy for cancer treatment: current effects and perspective. Nanoscale 11(37), 11–17178 (2019). 10.1039/c9nr05371a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Min, S. , et al.: Morphologically homogeneous, pH‐responsive gold nanoparticles for non‐invasive imaging of HeLa cancer. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 34, 102394 (2021). 10.1016/j.nano.2021.102394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dong, F. , et al.: Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) as potential drug carrier for treatment and care of cardiac hypertrophy agents. J. Cluster Sci. 33(3), 1–9 (2021). 10.1007/s10876-021-02003-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhu, A. , et al.: A SERS aptasensor based on AuNPs functionalized PDMS film for selective and sensitive detection of Staphylococcus aureus – ScienceDirect. Biosens. Bioelectron. 172, 112806 (2020). 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hua, J. : Synthesis and characterization of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and ZnO decorated zirconia as a potential adsorbent for enhanced arsenic removal from aqueous solution. J. Mol. Struct. 1228, 129482 (2020). 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuntner, C. , et al.: Dose‐response assessment of tariquidar and elacridar and regional quantification of P‐glycoprotein inhibition at the rat blood‐brain barrier using (R)‐[11C]verapamil PET. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imag. 37(5), 942–953 (2010). 10.1007/s00259-009-1332-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park, Y. , et al.: Highly eribulin‐resistant KBV20C oral cancer cells can be sensitized by co‐treatment with the third‐generation P‐glycoprotein inhibitor, Elacridar, at a low dose. Anticancer Res. 37, 4139–4146 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li, S. , et al.: Quercetin enhances chemotherapeutic effect of doxorubicin against human breast cancer cells while reducing toxic side effects of it. Biomed. Pharmacother. 100, 441–447 (2018). 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tajmir‐Riahi, H.A. The anticancer drug doxorubicin binds DNA and RNA at different locations. Éditions universitaires européennes; (2017) [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zaab, C. , et al.: Passive permeability assay of doxorubicin through model cell membranes under cancerous and normal membrane potential conditions. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 146, 133–142 (2020). 10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Attia, S.M. : Mutagenicity of some topoisomerase II‐interactive agents. Saudi Pharmaceut. J. 16, 1 (2008) [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freelander, A. , et al.: Molecular biomarkers for contemporary therapies in hormone receptor‐positive breast cancer. Genes 12(2), 285 (2021). 10.3390/genes12020285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teodori, E. , et al.: Dual P‐glycoprotein and CA XII inhibitors: a new strategy to reverse the P‐gp mediated multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer cells. Molecules 25(7), 1748 (2020). 10.3390/molecules25071748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang, E. , et al.: 7‐O‐geranylquercetin contributes to reverse P‐gp‐mediated adriamycin resistance in breast cancer. Life Sci. 238, 116938 (2019). 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu, J. , et al.: Codelivery of adriamycin and P‐gp inhibitor Quercetin using PEGylated liposomes to overcome cancer drug resistance. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 108(5), 1788–1799 (2019). 10.1016/j.xphs.2018.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bruynzeel, A. , et al.: Long‐term effects of 7‐monohydroxyethylrutoside (monoHER) on DOX‐induced cardiotoxicity in mice. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 60(4), 509–514 (2007). 10.1007/s00280-006-0395-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shanthi, K. , et al.: Fabrication of a pH responsive DOX conjugated PEGylated palladium nanoparticle mediated drug delivery system: an in vitro and in vivo evaluation. RSC Adv. 5(56), 44998–45014 (2015). 10.1039/c5ra05803a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bavli, Y. , et al.: Doxebo (doxorubicin‐free Doxil‐like liposomes) is safe to use as a pre‐treatment to prevent infusion reactions to PEGylated nanodrugs. J. Contr. Release 306, 138–148 (2019). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gonalves, J. , et al.: A combo‐strategy to improve brain delivery of antiepileptic drugs: focus on BCRP and intranasal administration. Int. J. Pharm. 593, 120161 (2021). 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.120161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boscolo, E. , Mulliken, J.B. , Bischoff, J. : VEGFR‐1 mediates endothelial differentiation and formation of blood vessels in a murine model of infantile hemangioma. Am. J. Pathol. 179(5), 2266–2277 (2011). 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shibuya, M. : Differential roles of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐1 and receptor‐2 in angiogenesis. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39(5), 469–478 (2006). 10.5483/bmbrep.2006.39.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heusinkveld, M. , et al.: M2 macrophages induced by prostaglandin E2 and IL‐6 from cervical carcinoma are switched to activated M1 macrophages by CD4+ Th1 cells. J. Immunol. 187(3), 1157–1165 (2011). 10.4049/jimmunol.1100889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petra, T. , et al.: Dietary selenium levels affect selenoprotein expression and support the interferon‐γ and IL‐6 immune response pathways in mice. Nutrients 7(8), 6529–6549 (2015). 10.3390/nu7085297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi, Z. , et al.: Enhanced chemosensitization in multidrug‐resistant human breast cancer cells by inhibition of IL‐6 and IL‐8 production. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 135(3), 737–747 (2012). 10.1007/s10549-012-2196-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hemauer, S.J. , et al.: Modulation of human placental P‐glycoprotein expression and activity by MDR1 gene polymorphisms. Biochem. Pharmacol. 79(6), 921–925 (2010). 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. El‐Readi, M.Z. , et al.: Resveratrol mediated cancer cell apoptosis, and modulation of multidrug resistance proteins and metabolic enzymes. Phytomedicine 55, 269–281 (2019). 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.06.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li, X. , et al.: Overexpression of a new gene P28GANK confers multidrug resistance of gastric cancer cells. Cancer Invest. 27(2), 129–139 (2009). 10.1080/07357900802189816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.