Abstract

Herein, the authors synthesised chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs) as a resveratrol (RSV) carrier and evaluated their efficacy in stimulating apoptosis in MDA‐MB 231 cells. Blank (Cs NPs) and RSV‐ Cs NPs (RSV‐Cs NPs) were synthesised via ionic gelation and characterised by using fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Scanning electron microscope, dynamic light scattering/Zeta potential and RSV release. MDA‐MB 231 cells were treated with RSV, Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs (24, 48, and 72 h), followed by the 3‐[4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl]‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. Cell toxicity was evaluated using lactate dehydrogenase assay, and real‐time polymerase chain reaction was performed to explore apoptosis induction. FTIR spectra confirmed the NPs via the formation of cross‐linking bonds. Cs and RSV‐Cs NPs sizes were about 75 and 198 nm with 14 and 24 mV zeta potentials. The RSV entrapment efficiency was 52.34 ± 0.16%, with an early rapid release followed by a sustained manner. Cs and RSV‐Cs NPs inhibited cell proliferation at lower concentrations and IC50 values. RSV‐Cs NPs had the most cytotoxic effect and stimulated intrinsic apoptotic pathway, indicated by increased Bcl‐2‐associated x (BAX), BAX/Bcl‐2 ratio, P53 expressions, reduced Bcl‐2 and upregulated caspases 3, 8 and 9. RSV‐Cs NPs have a great potential to suppress invasive breast cancer cell proliferation by targeting mitochondrial metabolism and inducing the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Keywords: apoptosis, breast cancer, chitosan nanoparticles, resveratrol

RSV‐Cs NPs potentially suppress MDA‐MB 231 breast cancer cells by inducing apoptosis via activating the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

1. INTRODUCTION

As the central malignancy of the female population, breast cancer (BC) surpassed lung cancer in terms of the leading cause of cancer worldwide in 2020. It involves 2.3 million new cases (11.7%) of all cancers, 25% and 15% of newly diagnosed and cancer death cases in women, respectively. The growing rate of BC incidence in South America, Africa and Asia is correlated with lifestyle changes and socio‐cultural and environmental factors [1]. From the point of molecular classification, BC is divided into hormone receptor‐positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor‐2 positive (HER2+) and triple‐negative BC (TNBC). HR+ BC encloses ER+, PR+ and ER+/PR+ subtypes, making up approximately 70% of the diagnosed breast tumours. Triple‐negative BC is the invasive form comprising nearly 15% of all BC types and is indicated by the negative expression of ER, PR and HER2 [2].

The standard therapies for BC include local (surgical resection and radiation therapy) and systemic (hormone therapy, chemotherapy and combination therapies) interventions [3]. However, BC relapse and metastasis observed in 50% of cases are the main reasons for cancer‐related mortality linked to poor prognosis and reduced survival [4]. Furthermore, chemotherapeutics induce toxicities against healthy tissues and lead to organ dysfunction [5]. Traditional medicine and herbal remedies have historically gained attention in cancer prevention and treatment. Resveratrol (RSV, trans‐3,4̕,5‐trihydroxystilbene) is a herbal polyphenol with various distributions in grapes, berries, peanuts, medicinal plants and some kinds of fungi [6].

Resveratrol is a strong anti‐oxidant compound with anti‐cancer, anti‐angiogenic, anti‐inflammatory and cardiovascular protective effects [7, 8, 9]. Resveratrol targeted RhoA/Lats1/YAP (Yes‐associated protein) signalling pathway in MDA‐MB231 and MDA‐MB468 BC cells through stimulating reactive oxygen species (ROS), followed by diminished proliferation and invasion [10]. Resveratrol suppressed MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB231 cancer cell lines through modulating apoptosis‐inducing miRNAs miR‐125b‐5p, miR‐200c‐3p, miR‐409‐3p, miR‐122‐5p and miR‐542‐3p [11]. Furthermore, it prohibited metastatic and stemness characteristics of BC by interfering with cancer cells and cancer‐associated fibroblast cross‐talk [12].

The challenges with RSV application are the low aqueous solution and bioavailability [13]. The instability of chemical structure and rapid degradation followed by the trans‐to‐cis isomerisation decline RSV anti‐oxidant potential and therapeutic efficacy [14]. An intelligent solution to this issue is employing innovative formulations based on nanoparticles (NPs) to improve RSV stability, enhance anti‐oxidant activity and provide controlled release [15]. Nanoparticulate systems have a wide application in cancer diagnosis, imaging, detection, and therapy [16]. Layer‐by‐layer liquid crystalline NPs were biocompatible and safe enough for tamoxifen and RSV co‐delivery while inducing apoptosis and DNA damage in MCF‐7 and CAL‐51 BC cell lines [17]. Naturally derived bio‐polymers are prominent in drug loading and delivery because of non‐toxicity, non‐immunogenicity, biocompatibility, high drug loading and controlled release potential [18]. Chitosan (Cs) is a natural deacetylated polymer from the chitin found in crustacean shells with excellent properties as a nanocarrier, including mucoadhesiveness, high structural resistance to acidic pH, the potential to proceed through cellular barriers and bearing functional groups for further cross‐linking and modifications [19, 20].

Anti‐cancer effects of RSV‐loaded Cs NPs and their modified forms have been assessed in prostate, colorectal and hepatic cancers [21, 22, 23]. However, no previous study reported the efficacy of RSV delivery via Cs NPs in BC. In the present study, we synthesised Cs NPs as a carrier to RSV via an ionic gelation method using sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) as a cross‐linker. Then, we investigated the morphological properties, particle size distribution, RSV Entrapment efficiency (EE) and release from NPs. In the next step, we looked for antiproliferative, anti‐cancer and anti‐apoptotic characteristics of prepared NPs against TNBC cell line MDA‐MB231 cells.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This work was approved by the ethical committee of the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran [Ethical code: IR.KUMS.MED.REC.1400.031].

2.1. Materials

Low molecular weight chitosan (LMWC, Cat# 448,869), sodium TPP (Cat# 238,503), RSV (Cat# R5010) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Cat# D8418) were prepared from Sigma (Sigma‐Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Taufkirchen, Germany). DMEM‐F12 medium (Cat# 10,565,018), foetal bovine serum (FBS, Cat# 16‐000‐044) and 3‐[4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl]‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reagent (Cat# M6494) were obtained from Gibco (Gibco Invitrogen, Massachusetts, USA).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Nanoparticle synthesis and characterisation

The blank and RSV‐loaded Cs NPs were synthesised by using the aforementioned ionic gelation method at room temperature [24]. The Cs solution was prepared in 0.5% acetic acid (2.0 mg/ml), stirring at 700 RPM for 6 h. The solution pH was set to 5 using 1M NaOH. The tripolyphosphate solution was prepared by dissolving 1.25 mg/ml TPP in deionised water under mild stirring. The pH was adjusted to 4 using 0.1 M HCl. Cs NPs were prepared by dropwise adding TPP into Cs solution (Cs: TPP ratio: 10:1) while stirring at 700 RPM for 15 min. RSV‐loaded Cs NPs were synthesised by adding RSV (2.0 mg/ml in DMSO) to the Cs solution. Suspensions were centrifuged at 15,000 RPM for 15 min at 4 °C, washed in deionised water 3 times and resuspended into glass Petri dishes and dried at 40 °C for 24 h.

2.2.2. FTIR

The fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy (FT‐IR) spectra were collected on a Nexus670 ThermoNicolet Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (Gaithersburg, USA) in 400‐4000 cm−1.

2.2.3. Dynamic light scattering/zeta potential

Nanoparticles size, distribution and surface charges were analysed with the suspension of NPs in a deionised water and subsequent assessment by the dynamic light scattering (DLS) method using Zeta sizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instrument, UK) at 25°C and a scattering angle of 90°.

2.2.4. Scanning electron microscope

The nanoparticle morphology was illustrated by scanning electron microscopy at 15kV, accelerating voltage by the MIRA3TESCAN‐XMU Scanning electron microscope (SEM) instrument (TESCAN ORSAY HOLDING, Brno‐Kohoutovice, Czech Republic).

2.2.5. Entrapment efficiency

The RSV EE was calculated by measuring RSV‐Cs NPs suspension and NP‐free supernatant absorbances at 310 nm using a Unico 2800 UV‐visible spectrophotometer instrument (UNICO, Dayton, NJ, USA). The EE was computed as follows:

Where total and free RSV were, respectively, the absorbances of NP suspension and the NP‐free supernatant were obtained following NP suspension centrifugation.

2.2.6. Drug release

The RSV release was evaluated by incubating RSV‐loaded NPs in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) (pH = 7.4, 37°C) at a 200 μg/ml concentration under slow agitation for 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h (n = 3). Half of the PBS was replaced by the equivalent volumes of fresh PBS at each time point. The collected samples were centrifuged, and their absorbances were read at 310 nm by using a Unico 2800 UV‐visible spectrophotometer.

2.2.7. Cell culture experiments

Cell line preparation

The human breast adenocarcinoma cell line (MDA‐MB231 and NCBI Code: C578) was ordered from the Pasteur Institute of Iran (Tehran, Iran). The MDA‐MB231 cells were incubated in the complete DMEM‐F12 medium containing 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2 pressure in a humidified incubator. The culture media were refreshed twice a week until the cells got a 70%–80% confluency.

Cell proliferation and IC50 determination

The antiproliferative effect of NPs against BC cells was evaluated by using MTT method, followed by calculating the half‐maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50). IC50 is a drug concentration inhibiting cancer cell proliferation by 50% and is the most common method to assess a drug's therapeutic potential in vitro [25]. 104 cells were cultured in each well of 96‐well plates and treated with RSV, Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs at 0, 25, 50, 100 and 200 μg/ml concentrations for 24, 48 and 72 h. After the incubation ended, the culture media were pulled out, 100 μL of the MTT solution (0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The MTT reagent was removed, and 100 μL DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The samples absorbances were read at an optical density (OD) = 570 nm by using an ELISA reader machine (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). Cell proliferation was calculated as follows:

Where OD C : the OD of the untreated cells and OD T : the OD of treated cells.

Cell proliferation data were analysed, and IC50 values were quantified according to the dose‐response curve.

Cell toxicity

Nanoparticle cytotoxicity was investigated via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. MDA‐MB231 cells were incubated at the IC50‐ defined concentrations of RSV, Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs for 48 h. Two untreated groups were included as control and total LDH samples. After the treatment, 20 μL PermiSolution was added to the total LDH cells and kept at room temperature for an hour. About 50 μL of supernatants from each group were added to the same volume of the working solution, followed by dark‐incubating at 37°C for 30 min. The triplicates absorbances were measured at OD = 545 nm in an ELISA reader machine. Cell toxicity was calculated as follows:

Where OD Control : the OD of the untreated cells, OD Test : the OD of treated cells and OD Total : the OD of the Total LDH group.

2.2.8. Apoptosis measurements

Real‐time PCR

A conventional quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique was used to evaluate the apoptosis induction in MDA‐MB231 cells. After treatment with IC50‐defined concentrations of RSV, Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs for 48 h, the cells were detached using the 0.25%Trypsin/EDTA and centrifuged at 1500 RPM for 10 min. Untreated cells were kept as the control group. otal RNA was extracted using the RNA isolation reagent Trizol (Life Biolab, Heidelberg, Germany) based on the manufacturer's recommendation. RNA concentration was determined using NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Germany, Deutschland). cDNA was synthesised from 1 μg RNA by using Thermo Scientific RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc., Porto Salvo, Portugal). Real‐time PCR was performed by employing SYBR green PCR Master Mix (RealQ Plus 2x Master Mix, Ampliqon, Denmark) containing reactive oxygen species as a reference dye in the step one Real‐time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, USA). The comparative threshold cycle (CT) was normalised against the glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase as the housekeeping gene, and the data were reported by fold change = 2^ ‐(ddCT). The forward and reverse primers are listed in the following table.

| Gene | Accession no. | Sequence (5'→3') | Length (bp) | Tm (°c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAX‐ human | NM_001291430.2 | F: cctgtgcaccaaggtgccggaact | 24 | 60 |

| R: ccaccctggtcttggatccagccc | 24 | |||

| Bcl‐2‐ human | NM_000657.3 | F: ttgtggccttctttgagttcggtg | 24 | 60 |

| R: ggtgccggttcaggtactcagtca | 24 | |||

| Caspase 3‐ human | NM_032991.3 | F: tggactgtggcattgagac | 19 | 60 |

| R: caaagcgactggatgaacc | 19 | |||

| Caspase 8‐ human | NM_001080125 | F: agaagagggtcatcctgggaga | 22 | 60 |

| R: tcaggacttccttcaaggctgc | 22 | |||

| Caspase 9‐ human | NM_001229 | F: gtttgaggaccttcgaccagct | 22 | 60 |

| R: caacgtaccaggagccactctt | 22 | |||

| P53‐ human | NM_001126118.2 | F: taacagttctgcatgggcggc | 21 | 60 |

| R: aggacaggcacaaacacgcacc | 22 | |||

| GAPDH‐ human | NM_001289745.3 | F: aaggtcggagtcaacggatttg | 22 | 60 |

| R: gccatgggtggaatcatattgg | 22 |

Abbreviation: BAX, Bcl‐2‐associated x.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data collected in replicates were registered as mean ± SD. A one‐way or two‐way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's test was accomplished in GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) at significant levels of p‐value <0.05, p‐value <0.01, and p‐value <0.001.

3. RESULTS

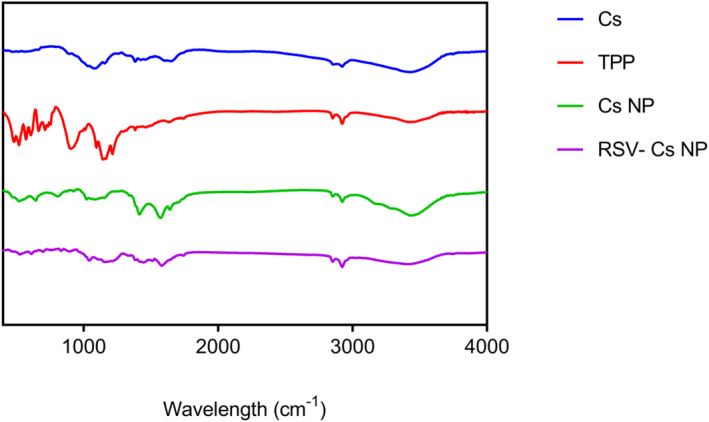

3.1. FTIR

The chemical compositions of Cs, TPP, Cs NP and RSV‐Cs NP samples are analysed at 400 to 4000 cm−1, verified with characteristic peaks of each compound and Cs‐TPP cross‐linking was done (Figure 1). A detailed description of FTIR peaks is shown in Table 1. The O‐H stretching peak of chitosan at 3425.6 cm−1 shifted towards a broader peak of 3437.15 cm−1 in Cs NPs, indicating increased O‐H and N‐H stretching of functional groups participating in hydrogen bond formation.

FIGURE 1.

FTIR spectra of chitosan (Cs), sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP), chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs) and resveratrol‐loaded Cs NPs (RSV‐ Cs NPs) at 400 to 4000 cm−1. FTIR, fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy

TABLE 1.

Characteristic FTIR peaks of chitosan (Cs), sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP), chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs), and resveratrol‐loaded chitosan nanoparticles (RSV‐Cs NPs)

| Wavelength (cm−1) | Compound | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 895 cm−1 | Cs | C‐H bending of the aromatic ring |

|

Cs | Skeletal vibrations involving O−C stretching |

| 1332 cm−1 | Cs | Amide III, C‐N stretching |

| 1427.3 cm−1 | Cs | O−H bending vibration |

| 1543 cm−1 | Cs | Amide II, N‐H deformation |

| 1635.6 cm−1 | Cs | Amide I, C=O stretching |

| 2855.6 cm−1 | Cs | C‐H asymmetric stretching |

| 2922.16 cm−1 | Cs | C‐H symmetric stretching |

| 3425.6 cm−1 | Cs | O‐H stretching |

| 895 cm−1 | TPP | Asymmetric stretching of the P−O−P bridge |

| 1080.1 cm−1 | TPP | Symmetric and anti‐symmetric stretching of the PO3 group |

| 1155.36 cm−1 | TPP | Symmetric and anti‐symmetric stretching of the PO2 group |

| 1151.5 cm−1 | Cs NP |

|

| 1207.4 cm−1 | Cs NP | Anti‐symmetric stretching of the PO2 group |

| 1572 cm−1 | Cs NP | N‐O‐P stretching |

| 1639.5 cm−1 | Cs NP | C=O stretching of amide I |

| 2924.1 cm−1 | Cs NP | C‐H symmetric stretching |

| 3437.15 cm−1 | Cs NP | O‐H and N‐H stretching |

| 900.7 cm−1 | RSV‐Cs NP | Asymmetric stretching of the P−O−P bridge of TPP |

| 1207.4 cm−1 | RSV‐ Cs NP | Anti‐symmetric stretching of the PO2 group of TPP |

| 1386.8 cm−1 | RSV‐ Cs NP |

|

| 1512.2 cm−1 | RSV‐ Cs NP | RSV benzene ring |

| 1581.6 cm−1 | RSV‐ Cs NP | C=C stretching of the aromatic ring of RSV |

| 3417.9 cm−1 | RSV‐ Cs NP | O‐H stretching |

Note: FTIR peaks confirm that Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs are formed.

Abbreviation: FTIR, fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy.

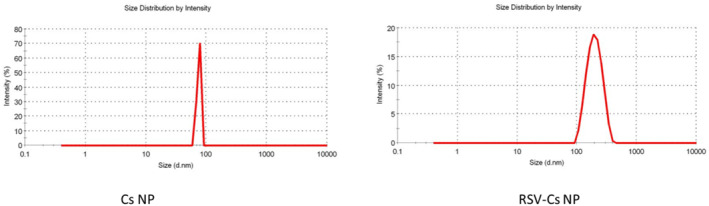

3.2. Dynamic light scattering/zeta potential

Nanoparticle sizes and zeta potential measured by DLS are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. The hydrodynamic diameter of Cs NPs was 75.6 ± 1.3 nm and 198.3 ± 4.6 for RSV‐Cs NPs. The polydispersity index of Cs NPs was 0.11 ± 0.023, which increased to 0.297 ± 0.045 for RSV‐Cs NPs. The polydispersity index in the range of 0.11–0.297 reflected monodisperse distribution without the aggregated NPs in suspension. Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs Zeta potentials were 14.8 and 24.0 mV, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Size distribution of chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs) and resveratrol‐loaded Cs NPs (RSV‐ Cs NPs) measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS). Cs NPs have a narrower size distribution identified by 75.6 ± 1.3 nm, while RSV‐Cs have a broader size range of 198.3 ± 4.6 nm

TABLE 2.

Mean particle size, Polydispersity index (PDI), Zeta potential, and entrapment efficiency (EE) of chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs) and resveratrol‐loaded chitosan nanoparticles (RSV‐Cs NPs)

| Sample | Mean particle size (nm) | Polydispersity index (PDI) | Zeta potential (mV) | Entrapment efficiency (EE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs NP | 75.6 ± 1.3 | 0.11 ± 0.023 | 14.8 ± 1.71 | ‐ |

| RSV‐Cs NP | 198.3 ± 4.6 | 0.297 ± 0.045 | 24 ± 3.32 | 52.34 ± 0.16% |

Note: Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs have nanometric sizes with narrow distribution. The entrapment efficiency of RSV into Cs NPs is more than 50%.

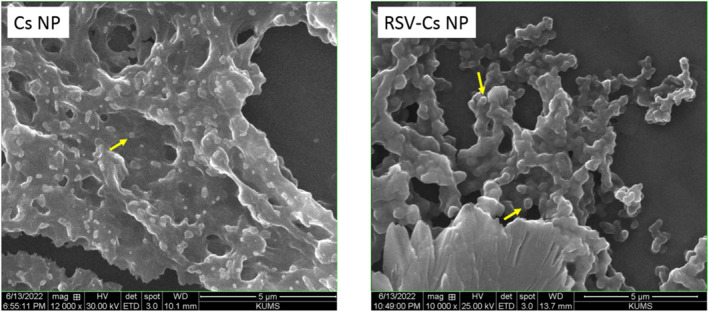

3.3. Scanning electron microscope

The morphology of NPs observed using SEM is shown in Figure 3. From SEM micrographs, the NPs are observed with high agglomeration in the dry state, mirroring inter‐and intramolecular hydrogen bonds. Most NPs were morphologically sphere‐shaped (yellow arrows) with nanometric sizes in both samples, but Cs NPs appeared to be smaller than RSV‐Cs NPs.

FIGURE 3.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrographs of chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs) and resveratrol‐loaded Cs NPs (RSV‐ Cs NPs). Nanoparticles are agglomerated in the dry state with smooth‐surface spherical morphology and nanometric sizes

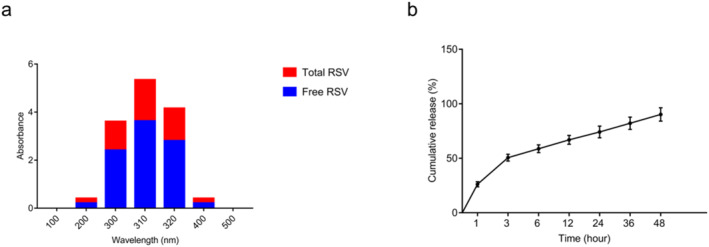

3.4. Entrapment efficiency and in vitro resveratrol release

The EE of RSV in Cs NPs is represented in Figure 4a. The data showed that EE was about 52.34 ± 0.16%, suggesting that more than half of RSV was incorporated into the Cs matrix. Besides, the results of RSV release from NPs over 48 h of incubation in PBS (pH = 7.4, 37°C) can be seen in Figure 4b. In the first 2 h post‐incubation, a fast release of RSV (50.6 ± 2.5%) was observed, followed by a slow release that reached 90.25 ± 5% within 48 h.

FIGURE 4.

Entrapment efficiency (EE) and in vitro resveratrol (RSV) release from RSV‐ Cs NPs. (a): EE of RSV was 52.34 ± 0.16%, suggesting that more than half of RSV was incorporated into the chitosan matrix. (b): in a 48‐h incubation of RSV‐ Cs NPs in PBS (pH = 7.4, 37°C), an early RSV burst release (50.6 ± 2.5%) in 2 h was detected, followed by a sustainable release reached 90.25 ± 5% till the end of incubation. PBS, phosphate‐buffered saline

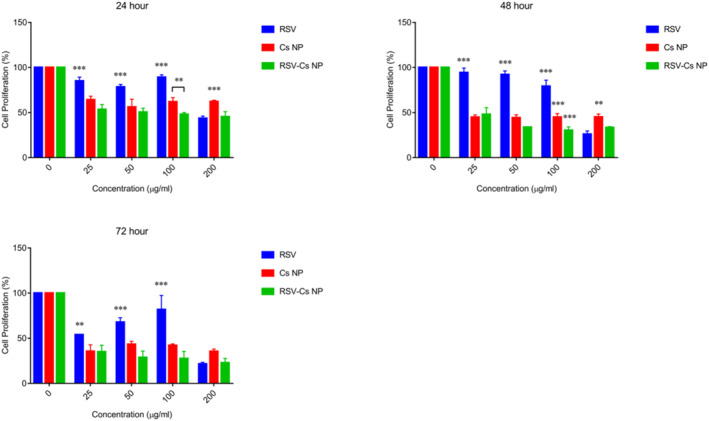

3.5. Cell proliferation and IC50 determination

The antiproliferative effects and IC50 values were assessed by an MTT assay following the treating MDA‐MB 231 cells with RSV, Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs at different concentrations and time points (Figure 5). The data suggested that all treatment groups had dose‐ and time‐dependent antiproliferative effects. Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs had a significantly higher antiproliferative effect than RSV at 25, 50 and 100 μg/ml concentrations at all time points (*** p‐value < 0.001). At 24 h, all concentrations of the treatment groups reduced cell proliferation. At this time, cell proliferation reached the minimum values of 43.6 ± 2.55% in RSV 200 μg/ml, 56.1 ± 8.7% in Cs NPs 50 μg/ml and 45.3 ± 5.7% in RSV‐Cs NPs 200 μg/ml. At 48 h, the minimised cell proliferation rates were 26 ± 3.5% in RSV 200 μg/ml, 44.2 ± 3.35% in Cs NPs 50 μg/ml and 30.3 ± 3.8% in RSV‐Cs NPs 100 μg/ml. At 72 h, cell proliferation reached the least values of 21.56 ± 1.75% in RSV 200 μg/ml, 35.5 ± 2.64% in Cs NPs 200 μg/ml and 22. 9 ± 4.8% in RSV‐Cs NPs 200 μg/ml.

FIGURE 5.

MDA‐MB 231 cell proliferation upon the incubation with different concentrations of resveratrol (RSV), chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs), and resveratrol‐loaded Cs NPs (RSV‐ Cs NPs) for 24, 48 and 72 h. Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs have a significantly higher antiproliferative effect than RSV at 25, 50 and 100 μg/ml concentrations at all time points (*** p‐value < 0.001)

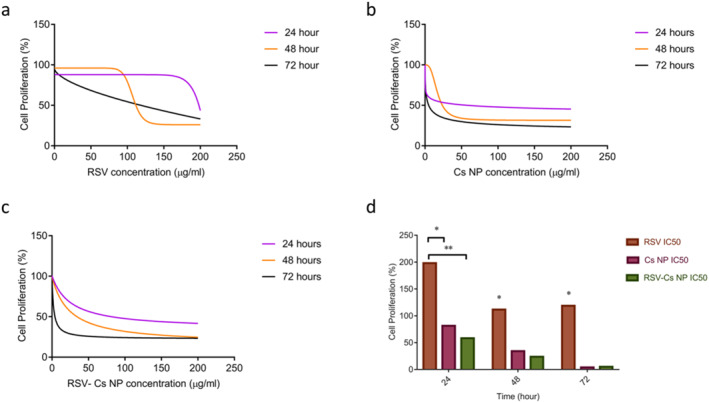

IC50 values calculated, following the plotting dose‐response graphs are represented in Figure 6. Accordingly, IC50 quantities at 24, 48 and 72 h for RSV were 198.094 μg/ml, 111.662 μg/ml and 118.617 μg/ml. For Cs NPs, IC50 quantities were 138.831 μg/ml, 59.752 μg/ml and 24.448 μg/ml. For RSV‐Cs NPs, IC50 values were 58.246 μg/ml, 23.743 μg/ml and 5.017 μg/ml. Different IC50 values were observed between the control group with treatments (** p‐value < 0. 01, * p‐value < 0. 05). These data showed the antiproliferative effect of RSV, Cs NPs and their combined nanoformulations on BC cells in a time and dose‐dependent manner.

FIGURE 6.

Dose‐response graphs and inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of resveratrol (RSV), chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs), and resveratrol‐loaded Cs NPs (RSV‐ Cs NPs) at 24, 48, and 72 h. Dose‐response graphs of (a): RSV; (b): Cs NPs; (c): RSV‐Cs NPs; (d): IC50 values of RSV, Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs.IC50 values decrease in a time‐dependent manner with remarkable differences between the control and treatment groups (** p‐value < 0. 01, * p‐value < 0. 05)

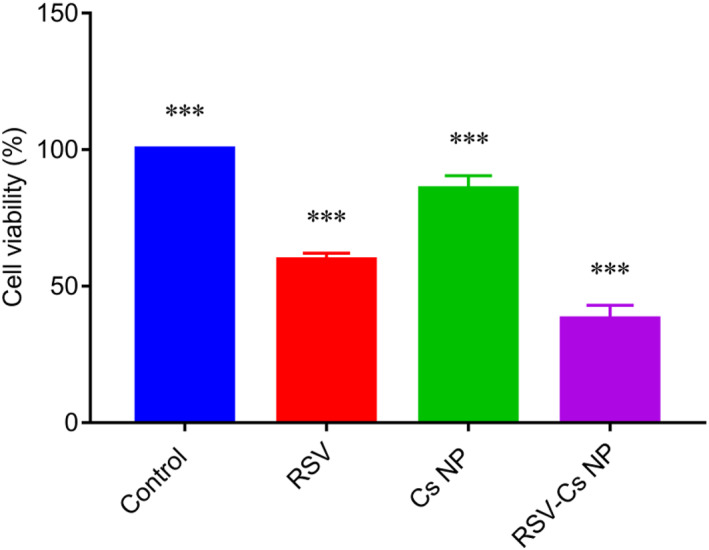

3.6. Cell toxicity

The cytotoxicity of RSV, Cs NPs and RSV‐C NPs was explored by using the LDH assay. Lactate dehydrogenase is a cytosolic enzyme released into culture media upon the cell plasma membrane breakage, indicating cell apoptosis, necrosis and other forms of injury [26]. MDA‐MB 231 cells were treated with the IC50‐defined concentrations of RSV, Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs for 48 h, as shown in Figure 7. Cell viabilities were 59.46 ± 2.16%, 85.47 ± 4% and 37.84 ± 4.2% for RSV, Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs. These data demonstrated that all treatments induced toxicities against the BC cells, among which RSV‐Cs NPs had the most prominent effect (*** p‐value < 0.001).

FIGURE 7.

MDA‐MB 231 cell viability upon the treatment with IC50‐defined concentrations of resveratrol (RSV), chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs), and resveratrol‐loaded Cs NPs (RSV‐ Cs NPs) for 48 h. Cell viabilities prominently diminished to 59.46 ± 2.16% for RSV, 85.47 ± 4% for Cs NPs, and 37.84 ± 4.2% for RSV‐Cs NPs. RSV‐Cs NPs had the most effect on cell viability inhibition (*** p‐value < 0.001)

3.7. Apoptosis measurements

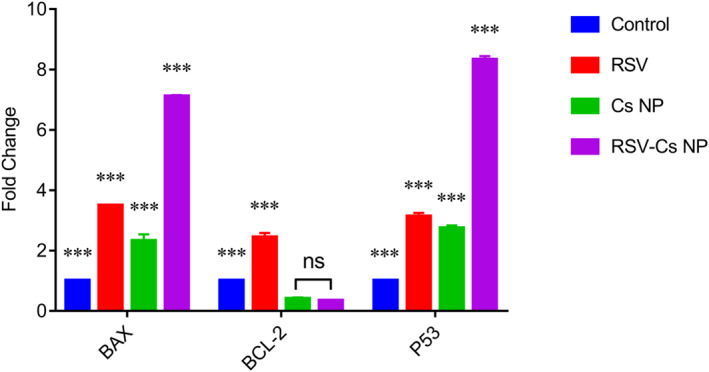

The activation of apoptotic pathways was evaluated using a quantitative real‐time PCR. Bcl‐2‐associated x (BAX), Bcl‐2 and P53 expression data are depicted in Figure 8. The BAX expression significantly increased in all treatment samples compared with the control group. The highest BAX expression was in cells treated with RSV‐Cs NPs by 7.1 fold, more significant than RSV (3.5 fold) and Cs NPs (2.3 fold) (*** p‐value < 0.001). The Bcl‐2 expression was outstandingly higher in control and the RSV (2.4 fold) samples when compared with NP‐treated cells (0.4 fold in Cs NPs and 0.35 fold in RSV‐Cs NPs) (*** p‐value < 0.001). However, no notable differences between cells treated with Cs NP and RSV‐Cs NP were observed (ns: non‐significant). P53 was notably overexpressed in treatment groups with 3.1 fold in RSV, 2.75 fold in Cs NPs and 8.3 fold in RSV‐Cs NPs (*** p‐value < 0.001).

FIGURE 8.

BAX, Bcl‐2, and P53 expression in MDA‐MB 231 cells treated with IC50‐defined concentrations of resveratrol (RSV), chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs), and resveratrol‐loaded Cs NPs (RSV‐ Cs NPs) NPs for 48 h. BAX expression significantly increases in all treatment groups, and the highest expression is observed in RSV‐Cs NPs (*** p‐value < 0.001). Bcl‐2 expression is outstandingly higher in control and RSV‐treated samples, while there is no different Bcl‐2 expression in cells treated with NPs (*** p‐value < 0.001, ns: non‐significant). P53 overexpresses in treatment samples with differences among groups in which the RSV‐Cs NPs group has the highest P53 level (*** p‐value < 0.001). BAX, Bcl‐2‐associated x

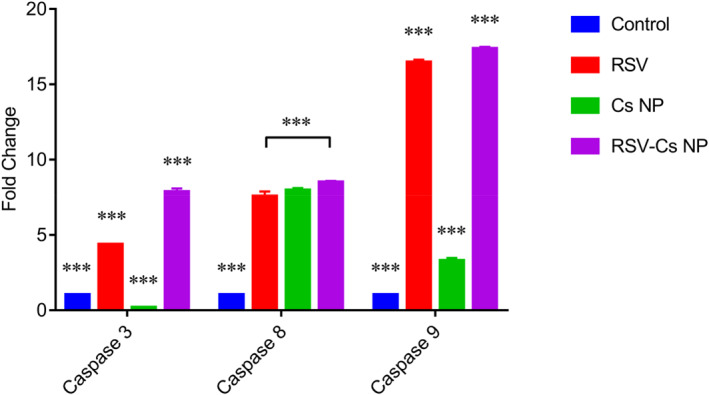

Also, to investigate the activation of intrinsic or extrinsic apoptotic pathways, we measured caspases 3, 8 and 9 expressions (Figure 9). The caspase 3 expression was higher in RSV (4.35 fold) and RSV‐Cs NPs (7.85 fold) than Cs NPs (0.16 fold) (*** p‐value < 0.001). Caspase 8 was prominently overexpressed in treated samples (7.5 fold in RSV, 7.93 fold in Cs NPs and 8.5 fold in RSV‐Cs NPs). The caspase 8 level was the highest in RSV‐Cs NPs, marked differently from the RSV‐treated samples (*** p‐value < 0.001). Similarly, caspase 9 increased in all treatments (16.4 fold in RSV, 3.27 fold in Cs NPs and 17.33 fold in RSV‐Cs NPs) with an extreme overexpression in RSV and RSV‐Cs NPs (*** p‐value < 0.001).

FIGURE 9.

Caspase 3, caspase 8 and caspase 9 expressions in MDA‐MB 231 cells were treated with IC50‐defined concentrations of resveratrol (RSV), chitosan nanoparticles (Cs NPs), and resveratrol‐loaded Cs NPs (RSV‐ Cs NPs) for 48 h. Caspase 3 expression is higher in RSV and RSV‐Cs NPs compared with the control and Cs NPs groups (*** p‐value < 0.001). Caspase 8 prominently overexpresses in treated samples, with the highest level in RSV‐Cs NPs (*** p‐value < 0.001). Caspase 9 increases in all treated groups with an extreme overexpression in RSV and RSV‐Cs NPs (*** p‐value < 0.001)

4. DISCUSSION

Cs‐based NPs are efficient nanocarriers for cancer therapy because they are biodegradable, biocompatible and can be administered orally and intravenously [27]. Also, the modification and functionalisation of Cs NPs allow for targeted delivery and local drug administration, which minimises systemic toxicities [28]. Phytochemical‐loaded NPs have been a great promise to treat BC. Ellagic acid‐loaded Cs NPs improved the anti‐cancer efficacy and breast tumour regression [29]. Loading curcumin into Cs‐protamine NPs upgraded its anti‐cancer effects by inhibiting NF‐κB, IL‐6 and TNF‐α and downregulating Bcl‐2 in BC cells [30]. In the present study, we synthesised Cs NPs for RSV delivery to get a more efficient therapeutic output against metastatic BC cells. The FTIR data confirmed the Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs formation. A peak at 1207.4 cm−1 pertains to the ionic cross‐links between Cs cationic amino groups and TPP anionic groups [31, 32]. A broad peak at 1639.5 cm−1 belonging to amide I C = O stretching was attributed to the strong electrostatic interactions between the TPP phosphorous and Cs amine groups. The resveratrol incorporation resulted in the disappearance of Cs aromatic ring peak at 895 cm−1 and broader O‐H stretching at 3417.9 cm−1, indicating more hydrogen bonds [33].

The resveratrol characteristic peaks were not detectable in the RSV‐loaded NPs due to the RSV wrapping into chitosan [34]. The mean particle size is decisive for NP biocompatibility, bioactivity and intratumor accumulation to ensure an effective anti‐cancer response. Our data affirmed that NP sizes were less than 200 nm, suitable for cellular uptake and drug delivery. Nanoparticles greater than 300 nm are detected by immune cells, like macrophages, and cleared from the blood circulation [35]. These data agreed with those reported earlier in which RSV‐Cs NPs exhibited larger hydrodynamic sizes due to their highly hydrating nature [24]. Zeta potential is a vital factor in determining NP stability in colloidal suspensions. Positive Zeta values obtained in our work return to the positively charged amine groups found in the chitosan structure. Positively charged NPs quickly pass through cancer cell membranes that are rich in negatively charged phospholipids and proteins [36]. Increased zeta in RSV‐loaded NPs illustrated an enhanced stability following RSV incorporation.

The EE of RSV‐Cs NPs was more than 50% quantitatively less than the previous reports in protein‐based and lipophilic NPs. The lower EE arises because the hydrophile identity of Cs restricts the interaction with lipophilic RSV molecules [24, 37]. The assessment of RSV release from NPs displayed an early burst release within 2 h followed by a sustainable release of up to 48 h. The burst release might occur due to the free RSV molecules at the surface of NPs and their subsequent desorption, diffusion and dissolution. In contrast, the gradual release brings entrapped RSV free into the culture medium [38]. The cell proliferation data manifested that RSV‐Cs NPs were more efficacious than the free RSV at equivalent concentrations, prompting higher cancer cell death [37]. Also, we found that lower concentrations of NPs showed better antiproliferative effects, which was in agreement with a report that depicted that the NPs at lower extents produce higher ROS [39].

IC50 values were notably reduced in Cs NPs and RSV‐Cs NPs compared to RSV, pointing out the improved anti‐cancer effects of nanoformulations arising from the enhanced RSV water solubility, bioavailability, physicochemical stability and controlled release [16]. A study showed the strong potential of RSV to suppress MDA‐MB 231 and Hela cancer cells via impairing cell respiration and glycolysis pathways, inducing oxidative stress and triggering mitophagy [40].

The evaluation of apoptosis‐related gene expression in treated cells suggested that RSV‐Cs NPs had the most pro‐apoptotic properties, possibly due to RSV nanoformulation and the synergistic effect of Cs and RSV to provoke apoptosis. BAX and Bcl‐2 are anti‐ and pro‐apoptotic mediators, which are crucial in cell survival and apoptosis regulation. In healthy cells, Bcl‐2 binds to BAX and hinders its activation. Increased BAX expression and reduced Bcl‐2 levels gave rise to a higher BAX/Bcl‐2 ratio in NP‐treated groups, indicating apoptosis stimulation [41]. Our findings represented that P53 expression increased in treatment groups. This observation agreed with the previous evidence that RSV‐loaded gelatin NPs prompted P53 activation associated with BAX expression, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in non‐small cell lung cancer cells [42].

Consistent with our results, RSV‐loaded solid lipid NPs exhibited a superior potential to increase BAX and decrease Bcl‐2 expression in MDA‐MB 231 cells in vitro, leading to a higher cell death rate [43]. Our work represented RSV‐Cs NPs upregulated caspases 3, 8 and 9 in treated cells. In one study, Cs NPs appeared to persuade cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by activating caspases 3 and 8, associated with the extrinsic apoptotic pathway [44]. In contrast, in another report, treating lung cancer cells with RSV‐loaded liposomes stimulated mitochondrial damage, which drove the intrinsic apoptotic pathway through cytochrome C release to activate caspases 9 and 3 [45]. In a similar report, Zhang et al. demonstrated that RSV‐loaded gold NPs upregulated caspases 3, 8 and 9 alongside activating PI3K/Akt signalling in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, which pertained to the involvement of intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptotic pathway [46].

5. CONCLUSION

To conclude, our work that showed Cs NPs provided a sustainable RSV release during the treatment time while reducing IC50 values. RSV‐Cs NPs exhibited a more potent apoptosis‐inducing effect against BC cells. This result reflected that Cs NPs improved the RSV bioavailability, stability and pharmacological properties in vitro. These data verified the strong potential of RSV‐Cs NPs as appropriate candidates, which could be regarded as a novel strategy for clinical BC therapy in the future. However, more 3‐dimensional in vitro and in vivo experiments are necessary to ensure the efficiency and possible side effects caused by the administration of nanoformulated therapeutic regimens before clinical use.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Azam Bozorgi: Conceptualisation; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft. Zahra Haghighi: Investigation; Methodology. Mohammad Rasool Khazaei: Project administration; Writing – review & editing. Maryam Bozorgi: Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology. Mozafar Khazaei: Conceptualisation; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report that they have no declarations of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was financially supported by the Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran, as a part of the MD thesis [grant No. 4000725].

Bozorgi, A. , et al.: Anti‐cancer effect of chitosan/resveratrol polymeric nanocomplex against triple‐negative breast cancer; an in vitro assessment. IET Nanobiotechnol. 17(2), 91–102 (2023). 10.1049/nbt2.12108

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sung, H. , et al.: Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J. Clin. 71(3), 209–49 (2021). 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Denkert, C. , et al.: Molecular alterations in triple‐negative breast cancer‐the road to new treatment strategies. Lancet 389(10087), 2430–42 (2017). 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32454-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waks, A.G. , Winer, E.P. : Breast cancer treatment: a review. JAMA 321(3), 288–300 (2019). 10.1001/jama.2018.19323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yousefi, M. , et al.: Organ‐specific metastasis of breast cancer: molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying lung metastasis. Cell. Oncol. 41(2), 123–40 (2018). 10.1007/s13402-018-0376-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zeglinski, M. , et al.: Trastuzumab‐induced cardiac dysfunction: a 'dual‐hit. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 16(3), 70–4 (2011) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sinha, D. , et al.: Resveratrol for breast cancer prevention and therapy: preclinical evidence and molecular mechanisms. Semin. Cancer Biol. 40‐41, 209–32 (2016). 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keshavarz, G. , et al.: Resveratrol effect on adipose‐derived stem cells differentiation to chondrocyte in three‐dimensional culture. Adv. Pharmaceut. Bull. 10(1), 88–96 (2020). 10.15171/apb.2020.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khazaei, M.R. , et al.: Inhibitory effect of resveratrol on the growth and angiogenesis of human endometrial tissue in an in Vitro threedimensional model of endometriosis. Reprod. Biol. 20(4), 484–90 (2020). 10.1016/j.repbio.2020.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bozorgi, A. , et al.: Natural and herbal compounds targeting breast cancer, a review based on cancer stem cells. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 23, 970–83 (2020). 10.22038/ijbms.2020.43745.10270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim, Y.N. , et al.: Resveratrol suppresses breast cancer cell invasion by inactivating a RhoA/YAP signaling axis. Exp. Mol. Med. 24(2), e296 (2017). 10.1038/emm.2016.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Venkatadri, R. , et al.: Role of apoptosis related miRNAs in resveratrol‐induced breast cancer cell death. Cell Death Dis. 7(2), e2104 (2016). 10.1038/cddis.2016.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suh, J. , Kim, D.H. , Surh, Y.J. : Resveratrol suppresses migration, invasion and stemness of human breast cancer cells by interfering with tumor‐stromal cross‐talk. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 643, 62–71 (2018). 10.1016/j.abb.2018.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davidov‐Pardo, G. , McClements, D.J. : Resveratrol encapsulation: designing delivery systems to overcome solubility, stability and bioavailability issues. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 38(2), 88–103 (2014). 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Orallo, F. : Comparative studies of the anti‐oxidant effects of cis‐and trans‐resveratrol. Curr. Med. Chem. 13(1), 87–98 (2006). 10.2174/092986706775197962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Al‐Jubori, A.A. , Sulaiman, G.M. , Tawfeeq, A.T. : Anti‐oxidant activities of resveratrol loaded poloxamer 407: an in vitro and in vivo study. J. Appl. Sci. Nanotechnol. 1(3), 1–12 (2021). 10.53293/jasn.2021.3809.1046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Siddiqui, I.A. , et al.: Resveratrol nanoformulation for cancer prevention and therapy. Ann. NY. Acad. Sci. 1348(1), 20–31 (2015). 10.1111/nyas.12811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al‐Jubori, A.A. , et al.: Layer‐by‐layer nanoparticles of tamoxifen and resveratrol for dual drug delivery system and potential triple‐negative breast cancer treatment. Pharmaceutics 13(7), 1098 (2021). 10.3390/pharmaceutics13071098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang, Y. , Sun, T. , Jiang, C. : Biomacromolecules as carriers in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 8(1), 34–50 (2018). 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bozorgi, A. , et al.: Application of nanoparticles in bone tissue engineering; a review on the molecular mechanisms driving osteogenesis. Biomater. Sci. 9(13), 4541–67 (2021). 10.1039/d1bm00504a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Motiei, M. , et al.: Intrinsic parameters for the synthesis and tuned properties of amphiphilic chitosan drug delivery nanocarriers. J. Contr. Release 260, 213–25 (2017). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eroglu, E. : A resveratrol‐loaded poly(2‐hydroxyethyl methacrylate)‐chitosan based nanotherapeutic: characterization and in vitro cytotoxicity against prostate cancer. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 21(4), 2090–8 (2021). 10.1166/jnn.2021.19317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang, Y. , et al.: In vitro and in vivo combinatorial anti‐cancer effects of oxaliplatin‐ and resveratrol‐loaded N, O‐carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles against colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 163, 105864 (2021). 10.1016/j.ejps.2021.105864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bu, L. , et al.: Trans‐resveratrol loaded chitosan nanoparticles modified with biotin and avidin to target hepatic carcinoma. Int. J. Pharm. 452(1‐2), 355–62 (2013). 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu, J. , et al.: Preparation and biological activity studies of resveratrol loaded ionically crosslinked chitosan‐TPP nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 175, 170–7 (2017). 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.07.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aykul, S. , Martinez‐Hackert, E. : Determination of half‐maximal inhibitory concentration using biosensor‐based protein interaction analysis. Anal. Biochem. 508, 97–103 (2016). 10.1016/j.ab.2016.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumar, P. , Nagarajan, A. , Uchil, P.D. : Analysis of cell viability by the lactate dehydrogenase assay. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2018(6), pdb.prot095497 (2018). 10.1101/pdb.prot095497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang, E. , et al.: Advances in chitosan‐based nanoparticles for oncotherapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 222, 115004 (2019). 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herdiana, Y. , et al.: Chitosan‐based nanoparticles of targeted drug delivery system in breast cancer treatment. Polymers 13(11), 1717 (2021). 10.3390/polym13111717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaur, H. , et al.: Ellagic acid‐loaded, tween 80‐coated, chitosan nanoparticles as a promising therapeutic approach against breast cancer: in‐vitro and in‐vivo study. Life Sci. 284, 119927 (2021). 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abdel‐Hakeem, M.A. , et al.: Curcumin loaded chitosan‐protamine nanoparticles revealed antitumor activity via suppression of NF‐κB, proinflammatory cytokines and Bcl‐2 gene expression in the breast cancer cells. J. Pharm. Sci. 110(9), 3298–305 (2021). 10.1016/j.xphs.2021.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dounighi, N. , et al.: Preparation and in vitro characterization of chitosan nanoparticles containing Mesobuthus eupeus scorpion venom as an antigen delivery system. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 18(1), 44–52 (2011). 10.1590/S1678-91992012000100006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tomaz, A. , et al.: Ionically crosslinked chitosan membranes used as drug carriers for cancer therapy application. Materials 11(10), 2051 (2018). 10.3390/ma11102051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cho, A. , et al.: Preparation of chitosan‐TPP microspheres as resveratrol carriers. J. Food Sci. 79(4), 79–E576 (2014). 10.1111/1750-3841.12395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jeong, H. , et al.: Resveratrol crosslinked chitosan loaded with phospholipid for controlled release and anti‐oxidant activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 93, 757–66 (2016). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vonarbourg, A. , et al.: Evaluation of pegylated lipid nanocapsules versus complement system activation and macrophage uptake. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 78(3), 620–8 (2006). 10.1002/jbm.a.30711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mirzaie, Z.H. , et al.: Docetaxel–chitosan nanoparticles for breast cancer treatment: cell viability and gene expression study. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 88(6), 850–8 (2016). 10.1111/cbdd.12814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shao, J. , et al.: Enhanced growth inhibition effect of Resveratrol incorporated into biodegradable nanoparticles against glioma cells is mediated by the induction of intracellular reactive oxygen species levels. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 72(1), 40–7 (2009). 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Senthil Kumar, C. , et al.: Targeted delivery and apoptosis induction of trans‐resveratrol‐ferulic acid loaded chitosan coated folic acid conjugate solid lipid nanoparticles in colon cancer cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 231, 115682 (2020). 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Khatun, M. , et al.: Resveratrol–ZnO nanohybrid enhanced anti‐cancerous effect in ovarian cancer cells through ROS. RSC Adv. 6(107), 105607–17 (2016). 10.1039/C6RA16664D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rodríguez‐Enríquez, S. , et al.: Resveratrol inhibits cancer cell proliferation by impairing oxidative phosphorylation and inducing oxidative stress. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 370, 65–77 (2019). 10.1016/j.taap.2019.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Siddiqui, I.A. , et al.: Excellent anti‐proliferative and pro‐apoptotic effect of (−)‐epigallocatechin‐3‐gallate encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles on human melanoma cell growth both in vitro and in vivo. Nanomedicine 10(8), 1619–26 (2014). 10.1016/j.nano.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Karthikeyan, S. , Hoti, S.L. , Prasad, N.R. : Resveratrol loaded gelatin nanoparticles synergistically inhibits cell cycle progression and constitutive NF‐kappaB activation, and induces apoptosis in non‐small cell lung cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 70, 274–82 (2015). 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang, W. , et al.: Anticancer effects of resveratrol‐loaded solid lipid nanoparticles on human breast cancer cells. Molecules 22(11), 1814 (2017). 10.3390/molecules22111814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wimardhani, Y.S. , et al.: Chitosan exerts anti‐cancer activity through induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in oral cancer cells. J. Oral Sci. 56(2), 119–26 (2014). 10.2334/josnusd.56.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang, X.‐X. , et al.: The use of mitochondrial targeting resveratrol liposomes modified with a dequalinium polyethylene glycol distearoylphosphatidyl ethanolamine conjugate to induce apoptosis in resistant lung cancer cells. Biomaterials 32(24), 5673–87 (2011). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang, D. , et al.: Nano‐gold loaded with resveratrol enhance the anti‐hepatoma effect of resveratrol in vitro and in vivo. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 15(2), 288–300 (2019). 10.1166/jbn.2019.2682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.