Key Points

Question

What are the metabolic signatures of major depressive disorder (MDD), what direction do they take, and how does the host gut microbiome contribute to these signatures?

Findings

In this cohort study, metabolites in the energy and lipid metabolism processes were associated with MDD. Changes in lipid metabolism were consistent with the gut dysbiosis observed in individuals with MDD.

Meaning

Energy and lipid metabolism was disrupted in individuals with MDD, the latter of which may be explained by gut dysbiosis observed in individuals with MDD.

This metabolome-wide association study evaluates the association of metabolic factors and the human gut microbiome and metabolome with major depressive disorder.

Abstract

Importance

Metabolomics reflect the net effect of genetic and environmental influences and thus provide a comprehensive approach to evaluating the pathogenesis of complex diseases, such as depression.

Objective

To identify the metabolic signatures of major depressive disorder (MDD), elucidate the direction of associations using mendelian randomization, and evaluate the interplay of the human gut microbiome and metabolome in the development of MDD.

Design, Setting and Participants

This cohort study used data from participants in the UK Biobank cohort (n = 500 000; aged 37 to 73 years; recruited from 2006 to 2010) whose blood was profiled for metabolomics. Replication was sought in the PREDICT and BBMRI-NL studies. Publicly available summary statistics from a 2019 genome-wide association study of depression were used for the mendelian randomization (individuals with MDD = 59 851; control individuals = 113 154). Summary statistics for the metabolites were obtained from OpenGWAS in MRbase (n = 118 000). To evaluate the interplay of the metabolome and the gut microbiome in the pathogenesis of depression, metabolic signatures of the gut microbiome were obtained from a 2019 study performed in Dutch cohorts. Data were analyzed from March to December 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes were lifetime and recurrent MDD, with 249 metabolites profiled with nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with the Nightingale platform.

Results

The study included 6811 individuals with lifetime MDD compared with 51 446 control individuals and 4370 individuals with recurrent MDD compared with 62 508 control individuals. Individuals with lifetime MDD were younger (median [IQR] age, 56 [49-62] years vs 58 [51-64] years) and more often female (4447 [65%] vs 2364 [35%]) than control individuals. Metabolic signatures of MDD consisted of 124 metabolites spanning the energy and lipid metabolism pathways. Novel findings included 49 metabolites, including those involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (ie, citrate and pyruvate). Citrate was significantly decreased (β [SE], −0.07 [0.02]; FDR = 4 × 10−04) and pyruvate was significantly increased (β [SE], 0.04 [0.02]; FDR = 0.02) in individuals with MDD. Changes observed in these metabolites, particularly lipoproteins, were consistent with the differential composition of gut microbiota belonging to the order Clostridiales and the phyla Proteobacteria/Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidetes/Bacteroidota. Mendelian randomization suggested that fatty acids and intermediate and very large density lipoproteins changed in association with the disease process but high-density lipoproteins and the metabolites in the tricarboxylic acid cycle did not.

Conclusions and Relevance

The study findings showed that energy metabolism was disturbed in individuals with MDD and that the interplay of the gut microbiome and blood metabolome may play a role in lipid metabolism in individuals with MDD.

Introduction

Major depression is an important determinant of population health, affecting people across the life span. It is associated with a plethora of debilitating symptoms beyond emotional dysregulation,1 spanning from cognition, motoric function, and neurovegetative symptoms to inflammation and disturbances of the immune system and increased risks of cardiometabolic disorders and mortality.2 Most antidepressants target the monoamine pathway, but evidence is increasing for a more complex interplay of multiple pathways involving a wide range of metabolic alterations spanning energy3 and lipid metabolism.4 Variations in lipids, including triglycerides, low- and very low-density lipoproteins (LDLs and VLDLs), high-density lipoproteins (HDLs), phosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylcholines, lysophosphatidylethanolamines, phosphatidylethanolamines, and sphingomyelins, have been associated with major depressive disorder (MDD) in various studies.5,6 Similarly disturbances in the metabolites in the energy metabolism or the tricarboxylic acid cycle have been reported in individuals with MDD.7

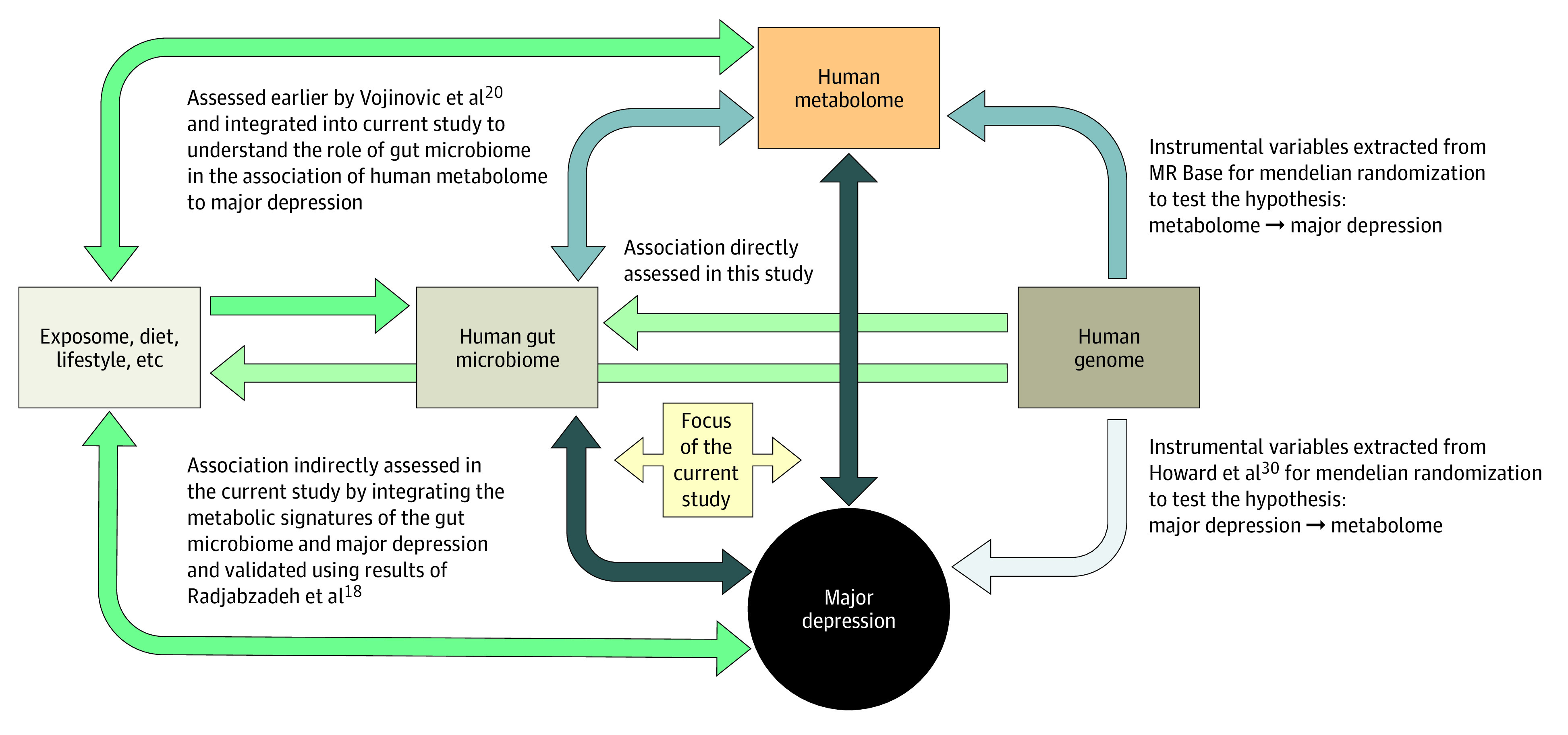

Disturbed plasma lipid concentrations have been implicated in the development of mitochondrial dysfunction,8 with HDLs inversely correlating with mitochondrial DNA damage.9 A recent study of 5283 patients with depression and 10 145 control individuals profiled with the Nightingale proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) metabolomics platform showed a shift toward decreased levels of HDLs and increased levels of VLDLs and triglycerides in patients with depression.10 The relevance and molecular mechanisms underlying this shift are not understood. The gut microbiome, which is primarily modulated by diet,11 has been shown to be a major determinant of circulating lipids, specifically triglycerides and HDLs,12,13,14,15,16 and regulate mitochondrial function.17 Disruptions to the gut microbiome have been found in patients with major depressive disorder.18,19 Metabolic signatures of the gut microbiome can be found in feces and blood.12,20,21 In our recent study,20 we observed an association of metabolites in plasma with 32 gut microbial groups. A higher abundance of family Christensenellaceae, genera Christensenellaceae R7 group, Ruminococcaceae (UCG002, UCG003, UCG005, UCG010, and UCG014), Coprococcus, Ruminococcaceae NK4A214 group, and Ruminiclostridium 6 was associated with a favorable lipid profile (ie, decreased VLDLs and increased HDLs). Decreased abundance of the same groups of gut microbiota were also associated with higher scores for depressive symptoms in our study of gut microbiome and depression.18 This raises questions as to whether the gut microbiome explains part of the shift in VLDL and HDL levels seen in patients with depression,10 and if the metabolic signatures of the disease based on Nightingale metabolites can be used as a tool to infer the association between gut microbiome and depression (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A Conceptual Framework of the Study.

Arrows depict the directionality of association, and darker shading indicates stronger associations. The green arrows depict associations that were neither studied nor used in the current study.

In this study, we harness the power of the UK Biobank to study more than 58 257 individuals, including 6811 individuals with lifetime MDD and 4370 with recurrent MDD who were profiled for NMR spectroscopy–based metabolites with the Nightingale platform. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date evaluating dysregulation of metabolites involved in the mitochondrial functioning in individuals with MDD. When integrating the data with those of the gut microbiome to understand the interplay between the blood metabolome, gut microbiome, and MDD, we found evidence that altered gut microbiome may be associated with the shift in VLDL-HDL ratio in individuals with MDD.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The study is embedded in the UK Biobank cohort, which comprises more than 500 000 individuals. Participants aged 37 to 73 years during recruitment (2006 to 2010) for whom blood sampling was performed were included.22 Participants were registered with the UK National Health service and from 22 assessment centers across England, Wales, and Scotland using standardized procedures for data collection, including a wide range of questionnaires, anthropological measurement, clinical biomarkers, and genotype data. All participants provided electronically signed informed consent. UK Biobank has approval from the Northwest Multicenter Research Ethics Committee, the Patient Information Advisory Group, and the Community Health Index Advisory Group. Further details on the rationale, study design, survey methods, data collection are available elsewhere.22 The current study is a part of UK Biobank projects 30418 and 54520.

Definition of Traits

We considered 2 phenotypes for the initial analyses, including lifetime and recurrent MDD. Both were defined using the UK Biobank field code 20126, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes F32 (single episode) and F33 (recurrent), or if participants were receiving antidepressant therapy at baseline. Individuals who reported any other mental illnesses (eg, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and psychosis) were excluded. Control individuals included those who had not reported depression at baseline. Details on the exclusions and assessment of confounders are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Metabolite Profiling

A random subset of 118 466 individuals was profiled for plasma metabolites using a high-throughput 1H-NMR metabolomics (Nightingale Health; biomarker quantification version 2020),23,24 which includes 249 metabolites. A natural logarithm transformation of each metabolite was performed for the analysis. The 0 values were replaced by the lowest value except for 0. Finally, the transformed values were scaled to standard deviation units. Details are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Replication

For replication, we considered the results from the 2020 study performed in Dutch cohorts by the Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure, Netherlands (BBMRI-NL), consortium.10 The study included 5283 individuals with depression and 10 145 control individuals, who were characterized using the Nightingale platform. Further replication was sought in the Predictors of Remission in Depression to Individual and Combined Treatments (PREDICT) study.25 Details on the PREDICT study, metabolomics profiling, and statistical analysis are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed in R statistical software version 4.1.2 (R Foundation). Descriptive analysis was performed using the CBCgrps26 library of R. Data were analyzed from March to December 2021.

Metabolome-Wide Association Analysis

We used logistic regression to test the association of the metabolite levels with lifetime and recurrent depression. We considered 4 models with an increasing number of covariates in each subsequent model to identify the effects of most known confounders in the regression analysis. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, fasting time, race and ethnicity, assessment center, and technical variables during the NMR measurement, (ie, batch and spectrometer); model 2 was additionally adjusted for body mass index (BMI); model 3 for antidepressant use; and model 4 for most known lifestyle factors, including smoking status, alcohol intake frequency, physical activity, education, and medication use for common chronic diseases. A false discovery rate (FDR) of .05 was used to identify significantly associated metabolites. We further performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding participants currently receiving antidepressant therapy. Race and ethnicity data were included in this study because ethnicity is a known confounder in epidemiological studies and were gathered via self-report according to the categories used in the UK Biobank: Asian or Asian British, Black or Black British, Chinese, White, mixed (Black Caribbean and White, Black African and White, Asian and White, or any other mixed background), and other (not specified).

Integration of Metabolic Signatures of Human Gut Microbiome and MDD

To identify patterns of correlation in the metabolic signatures of MDD and the human gut microbiome, we first regressed the metabolic signatures of MDD on the metabolic signatures of the gut microbiota (MDD z score on microbe z score), then regressed the metabolic signatures of gut microbiota on the metabolic signatures of MDD (microbe z score on MDD z score). MDD z score included the results of the association analysis of MDD with Nightingale metabolites from the current study, while microbe z score included the results of the association analysis of the gut microbiome ascertained with 16S RNA sequencing and with the Nightingale metabolites published earlier by Vojinovic et al.20 Correlation between the metabolic profiles of the 361 gut microbial taxa and MDD was estimated as the geometric mean of the effect estimates from the 2 regressions described above (ie, r2 = β for MDD on microbe × β for microbe on MDD). Since the 249 metabolites were correlated, a simple linear regression would give inflated regression slopes. We therefore used a linear mixed model using 20 metabolite clusters identified using the method of Li and Ji27 as random effects to account for the correlation structure in the metabolites. Significance of the correlation was tested using the t test. FDR was applied to correct for multiple testing. Next, we compared the t statistics (proxy association for MDD-microbiome based on the metabolome) as obtained in the present study with the z scores (direct association of MDD and microbiome) from Radjabzadeh et al.18

Mendelian Randomization

Mendelian randomization provides evidence about putative associations between modifiable risk factors and disease using genetic variants as natural experiments.28 To ascertain whether the direction of the association observed between metabolites and MDD, we performed bidirectional 2-sample mendelian randomization using the R package TwoSampleMR.29 For mendelian randomization, we used single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) with a P value <1 × 10−6, with linkage disequilibrium R2 < .001 within 10 000 kbps clumping distance. The overlapping SNVs were used without seeking proxy SNVs, as we assumed that each meaningful locus should have multiple SNVs significant and overlapped. The metabolite genome-wide association data were obtained from the Medical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unity OpenGWAS in MRbase,29 which included all UK Biobank participants recruited who were profiled for Nightingale metabolites (n = 118 000). For MDD, we used the publicly available results of the 2019 genome-wide association study by Howard et al30 (individuals with MDD = 59 851; control individuals = 113 154). Pleiotropy was assessed using the Egger method.

Results

This study included 6811 individuals with lifetime major depression vs 51 446 control individuals and 4370 with recurrent major depression vs 62 508 control individuals (Table). Individuals with lifetime major depression were significantly younger (median [IQR] age, 56 [49-62] years vs 58 [51-64] years), more often female (4447 [65%] vs 2364 [35%]), more likely to smoke, had higher education, had a higher BMI, were less physically active, consumed less alcohol, and were more likely to have a Black or mixed racial or ethnic background compared to control individuals (Table). Of the participants with history of depression, 1312 (19%) were using antidepressants at the time of assessment. Individuals with depression more often used medication related to gastric diseases, pain, and addiction (Table).

Table. Descriptive Statistics for Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Control Individuals and Recurrent Depression.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime MDD | Recurrent MDD | |||||

| Control (n = 51 446) | MDD (n = 6811) | P value | Control (n = 62 508) | MDD (n = 4370) | P value | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 58 (51-64) | 56 (49-62) | <1 × 10−10 | 58 (50-63) | 56 (49-62) | <1 × 10−10 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 24 535 (48) | 4447 (65) | <1 × 10−10 | 30 637 (49) | 2870 (66) | <1 × 10−10 |

| Male | 26 911 (52) | 2364 (35) | 31 871 (51) | 1500 (34) | ||

| BMI, median (IQR) | 26.62 (24.16-29.6) | 26.76 (24.09-30.16) | 1.54 × 10−4 | 26.64 (24.13-29.68) | 26.81 (24.05-30.37) | 2.49 × 10−4 |

| Fasting time, median (IQR) | 1.1 (0.69-1.39) | 1.1 (1.1-1.39) | 1.10 × 10−9 | 1.1 (0.69-1.39) | 1.1 (1.1-1.39) | 1.42 × 10−8 |

| Race and ethnicitya | ||||||

| Asianb | 918 (2) | 121 (2) | 1.97 × 10−8 | 1317 (2) | 86 (2) | 9.85 × 10−5 |

| Blackc | 694 (1) | 109 (2) | 982 (2) | 78 (2) | ||

| Chinese | 175 (0) | 10 (0) | 240 (0) | 8 (0) | ||

| Whited | 49 006 (95) | 6437 (95) | 59 065 (94) | 4108 (94) | ||

| Mixede | 222 (0) | 64 (1) | 279 (0) | 40 (1) | ||

| Otherf | 431 (1) | 70 (1) | 625 (1) | 50 (1) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| A levels, AS levels, or equivalent | 5767 (11) | 867 (13) | 1 × 10−10 | 6951 (11) | 540 (12) | 1 × 10−10 |

| CSEs or equivalent | 2591 (5) | 367 (5) | 3319 (5) | 236 (5) | ||

| College or university degree | 17 398 (34) | 2505 (37) | 20 775 (33) | 1645 (38) | ||

| NVQ or HND or HNC or equivalent | 3676 (7) | 407 (6) | 4411 (7) | 260 (6) | ||

| O levels, GCSEs, or equivalent | 10 909 (21) | 1518 (22) | 13 310 (21) | 965 (22) | ||

| Other professional qualifications | 2877 (6) | 355 (5) | 3382 (5) | 232 (5) | ||

| None | 8228 (16) | 792 (12) | 10 360 (17) | 492 (11) | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Current | 3190 (6) | 581 (9) | 1 × 10−10 | 4125 (7) | 390 (9) | 1 × 10−10 |

| Previous | 17 463 (34) | 2598 (38) | 21 076 (34) | 1663 (38) | ||

| Never | 30 793 (60) | 3632 (53) | 37 307 (60) | 2317 (53) | ||

| Physical activity | ||||||

| High | 20 897 (41) | 2692 (40) | 7.86 × 10−4 | 25 052 (40) | 1721 (39) | 2.56 × 10−1 |

| Moderate | 21 548 (42) | 2801 (41) | 26 222 (42) | 1821 (42) | ||

| Low | 9001 (17) | 1318 (19) | 11 234 (18) | 828 (19) | ||

| Alcohol frequency | ||||||

| Daily or almost daily | 10 706 (21) | 1324 (19) | 1 × 10−10 | 12 666 (20) | 851 (19) | 1 × 10−10 |

| Three or four times a wk | 13 138 (26) | 1559 (23) | 15 569 (25) | 999 (23) | ||

| Once or twice a wk | 13 951 (27) | 1658 (24) | 16 871 (27) | 1031 (24) | ||

| Less than once a wk | 13 651 (27) | 2270 (33) | 17 402 (28) | 1489 (34) | ||

| Medicationsg | ||||||

| A02BC proton pump inhibitors | ||||||

| No | 47 779 (93) | 6016 (88) | 1 × 10−10 | 57 702 (92) | 3844 (88) | 1 × 10−10 |

| Yes | 3667 (7) | 795 (12) | 4806 (8) | 526 (12) | ||

| C01AA digitalis glycosides | ||||||

| No | 51 335 (100) | 6801 (100) | 3.02 × 10−1 | 62 372 (100) | 4366 (100) | 1.12 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 111 (0) | 10 (0) | 136 (0) | 4 (0) | ||

| C10 lipid-modifying agents | ||||||

| No | 41 559 (81) | 5643 (83) | 4.57 × 10−5 | 50 552 (81) | 3581 (82) | 8.46 × 10−2 |

| Yes | 9887 (19) | 1168 (17) | 11 956 (19) | 789 (18) | ||

| A10BA02 metformin | ||||||

| No | 50 213 (98) | 6624 (97) | 8.68 × 10−2 | 60 950 (98) | 4226 (97) | 1.34 × 10−3 |

| Yes | 1233 (2) | 187 (3) | 1558 (2) | 144 (3) | ||

| A10.excl.A10BA02 antidiabetes excluding metformin | ||||||

| No | 51 045 (99) | 6769 (99) | 1.68 × 10−1 | 61 999 (99) | 4335 (99) | 9.94 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 401 (1) | 42 (1) | 509 (1) | 35 (1) | ||

| B01AC06 acetylsalicylic acid | ||||||

| No | 44 604 (87) | 6079 (89) | 4.50 × 10−9 | 54 175 (87) | 3887 (89) | 1.86 × 10−5 |

| Yes | 6842 (13) | 732 (11) | 8333 (13) | 483 (11) | ||

| C07 β-blocking agents | ||||||

| No | 48 273 (94) | 6392 (94) | 9.81 × 10−1 | 58 587 (94) | 4098 (94) | 9.24 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 3173 (6) | 419 (6) | 3921 (6) | 272 (6) | ||

| C08 calcium channel blockers | ||||||

| No | 47 802 (93) | 6374 (94) | 4.53 × 10−2 | 58 107 (93) | 4087 (94) | 1.67 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 3644 (7) | 437 (6) | 4401 (7) | 283 (6) | ||

| C03 diuretics | ||||||

| No | 47 687 (93) | 6352 (93) | 9.42 × 10−2 | 57 968 (93) | 4095 (94) | 1.79 × 10−2 |

| Yes | 3759 (7) | 459 (7) | 4540 (7) | 275 (6) | ||

| C02 antihypertensives | ||||||

| No | 50 716 (99) | 6739 (99) | 1.86 × 10−2 | 61 628 (99) | 4324 (99) | 6.07 × 10−2 |

| Yes | 730 (1) | 72 (1) | 880 (1) | 46 (1) | ||

| C09 agents acting on the renin angiotensin system | ||||||

| No | 44 437 (86) | 5971 (88) | 3.57 × 10−3 | 54 094 (87) | 3832 (88) | 3.28 × 10−2 |

| Yes | 7009 (14) | 840 (12) | 8414 (13) | 538 (12) | ||

| N02A opioids | ||||||

| No | 50 044 (97) | 6414 (94) | 1 × 10−10 | 60 470 (97) | 4107 (94) | 1 × 10−10 |

| Yes | 1402 (3) | 397 (6) | 2038 (3) | 263 (6) | ||

| N02B other analgesics and antipyretics | ||||||

| No | 38 515 (75) | 4683 (69) | 1 × 10−10 | 46 089 (74) | 2952 (68) | 1 × 10−10 |

| Yes | 12 931 (25) | 2128 (31) | 16 419 (26) | 1418 (32) | ||

| N02C antimigraine preparations | ||||||

| No | 51 042 (99) | 6700 (98) | 1 × 10−10 | 61 964 (99) | 4296 (98) | 6.10 × 10−8 |

| Yes | 404 (1) | 111 (2) | 544 (1) | 74 (2) | ||

| N03A antiepileptics | ||||||

| No | 50 997 (99) | 6675 (98) | <1 × 10−10 | 61 860 (99) | 4292 (98) | 5.65 × 10−6 |

| Yes | 449 (1) | 136 (2) | 648 (1) | 78 (2) | ||

| N04A anticholinergic agents | ||||||

| No | 51 439 (100) | 6809 (100) | 2.84 × 10−1 | 62 499 (100) | 4369 (100) | 4.91 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 7 (0) | 2 (0) | 9 (0) | 1 (0) | ||

| N04B dopaminergic agents | ||||||

| No | 51366 (100) | 6797 (100) | 4.20 × 10−1 | 62 402 (100) | 4363 (100) | >.99 |

| Yes | 80 (0) | 14 (0) | 106 (0) | 7 (0) | ||

| N05A antipsychotics | ||||||

| No | 51 365 (100) | 6736 (99) | <1 × 10−10 | 62 410 (100) | 4330 (99) | <1 × 10−10 |

| Yes | 81 (0) | 75 (1) | 98 (0) | 40 (1) | ||

| N05B anxiolytics | ||||||

| No | 51 398 (100) | 6762 (99) | <1 × 10−10 | 62 444 (100) | 4330 (99) | <1 × 10−10 |

| Yes | 48 (0) | 49 (1) | 64 (0) | 40 (1) | ||

| N05C hypnotics and sedatives | ||||||

| No | 51 369 (100) | 6714 (99) | <1 × 10−10 | 62 380 (100) | 4311 (99) | <1 × 10−10 |

| Yes | 77 (0) | 97 (1) | 128 (0) | 59 (1) | ||

| N06A antidepressants | ||||||

| No | 51 405 (100) | 5499 (81) | <1 × 10−10 | 61 783 (99) | 3491 (80) | <1 × 10−10 |

| Yes | 41 (0) | 1312 (19) | 725 (1) | 879 (20) | ||

| N06B psychostimulants agents used for ADHD and nootropics | ||||||

| No | 51 443 (100) | 6808 (100) | 2.43 × 10−2 | 62 504 (100) | 4369 (100) | 2.87 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 3 (0) | 3 (0) | 4 (0) | 1 (0) | ||

| N06C psycholeptics and psychoanaleptics in combination | ||||||

| No | 51 446 (100) | 6808 (100) | 1.60 × 10−3 | 62 503 (100) | 4369 (100) | 3.33 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 3 (0) | 5 (0) | 1 (0) | ||

| N06D antidementia drugs | ||||||

| No | 51 184 (99) | 6788 (100) | 6.96 × 10−2 | 62 196 (100) | 4354 (100) | 2.69 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 262 (1) | 23 (0) | 312 (0) | 16 (0) | ||

| N07A parasympathomimetics | ||||||

| No | 51 432 (100) | 6807 (100) | 1.51 × 10−1 | 62 484 (100) | 4368 (100) | 6.86 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 14 (0) | 4 (0) | 24 (0) | 2 (0) | ||

| N07B drugs used in addictive disorders | ||||||

| No | 51 424 (100) | 6798 (100) | 9.10 × 10−5 | 62 480 (100) | 4363 (100) | 6.72 × 10−3 |

| Yes | 22 (0) | 13 (0) | 28 (0) | 7 (0) | ||

| N07C antivertigo preparations | ||||||

| No | 51 331 (100) | 6784 (100) | 9.64 × 10−3 | 62 366 (100) | 4354 (100) | 9.53 × 10−2 |

| Yes | 115 (0) | 27 (0) | 142 (0) | 16 (0) | ||

| N01A anesthetics, general | ||||||

| No | 51 444 (100) | 6808 (100) | 1.33 × 10−2 | 62 498 (100) | 4368 (100) | 1.83 × 10−1 |

| Yes | 2 (0) | 3 (0) | 10 (0) | 2 (0) | ||

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Race and ethnicity data were gathered for this study via self-report and electronic health record because ethnicity is a known confounder in epidemiological studies. Categories are as they are presented in the UK Biobank and included Asian or Asian British, Black or Black British, Chinese, White, mixed, and other.

Including Bangladeshi, Indian, Pakistani, and any other Asian background.

Including African, Caribbean, and any other Black background.

Including White British, Irish, and any other White background.

Including Asian and White, Black African and White, Black Caribbean and White, and any other mixed background.

Individual responses not reported.

Medications are defined by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes.

Metabolome-Wide Association Analysis for Major Depression Using the Nightingale Platform

Results of the analysis are shown in eFigures 1-5 in Supplement 1. Adjusting for age, sex and technical covariates, 178 of 249 metabolites tested (71.0%) were significantly (defined as FDR < .05) associated with MDD in model 1. When adjusting for BMI (model 2), 163 metabolites (65.5%) remained significantly associated with MDD, and further adjusting for antidepressant use (model 3) yielded 132 metabolites (53.0%) significantly associated with MDD. In the full model further adjusted for lifestyle factors, including physical activity, alcohol consumption, smoking, education, and medication use for cardiovascular morbidity (model 4), a total of 124 metabolites (49.8%) remained significantly associated with MDD (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). These include 27 VLDL particles that were increased in individuals with MDD; 18 HDL particles, all of which were decreased in individuals with MDD except the triglycerides in HDL particles; and 5 intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) particles, all of which were decreased in individuals with MDD except the triglyceride content in IDL. Among fatty acids, total monounsaturated fatty acids (β [SE], 0.05 [0.02]; FDR = 6.8 × 10−03) and its ratio to total fatty acids (β [SE], 0.10 [0.02]; FDR = 5.5 × 10−06) were significantly increased in individuals with MDD while the ratios of linoleic acid (β [SE], −0.04 [0.02]; FDR = 0.05), omega 6 (β [SE], −0.06 [0.02]; FDR = 3.2 × 10−03), and polyunsaturated fatty acid (β [SE], −0.06 [0.02]; FDR = 2.0 × 10−03) to total fatty acids were significantly decreased in individuals with MDD. Further, apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1; β [SE], −0.06 [0.02]; FDR = 0.01), cholesteryl esters (β [SE], −0.05 [0.02]; FDR = 0.03), citrate (β [SE], −0.07 [0.02]; FDR = 4.0 × 10−04), and sphingomyelins (β [SE], −0.06 [0.02]; FDR = 2.6 × 10−03) were significantly decreased in individuals with MDD while alanine (β [SE], 0.05 [0.02]; FDR = 0.02) and pyruvate (β [SE], 0.04 [0.02]; FDR = 0.02) were significantly increased in individuals with MDD (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). The correlation structure of the 124 associated metabolites is provided in eFigure 6 in Supplement 1. Findings were very similar when excluding those with antidepressant use instead of adjusting for antidepressants (eFigure 7 and eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Comparing the results of lifetime MDD with those of recurrent depression, the metabolic profiles were found to be similar (eFigures 2, 3, 4, and 5 in Supplement 1).

Comparing our results with those of the BBMRI-NL,10 113 of the metabolites that we found to be associated with MDD were also studied by BBMRI-NL. The effects of the identified metabolites from model 4 in our study are consistent with those seen in the previous study by the BBMRI-NL consortium (eFigure 8 and eTable 3 in Supplement 1). In the present study, we identified 49 metabolites that were FDR significant that were not reported in the BBMRI-NL study (11 were not measured, and 38 did not achieve significance in the study after correction for multiple testing) (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). These include metabolites involved in mitochondrial functioning, including alanine, citrate, pyruvate and fatty acids, including percentage polyunsaturated fatty acid, percentage linoleic acid, percentage omega 6, sphingomyelins, and IDL subfractions, in addition to some VLDL and HDL subfractions that were not associated in the BBMRI study. The association of depression with omega 6, polyunsaturated fatty acid, citrate, and pyruvate was replicated in the PREDICT study25 (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). We could not replicate the finding on alanine, sphingomyelins, IDL, or other lipid fractions, although most of these showed consistency in direction of effects in the BBMRI-NL study (eFigure 8 in Supplement 1).

Mendelian Randomization Analysis

Results of bidirectional mendelian randomization are provided in eFigure 9 and eTable 6 in Supplement 1. No significant pleiotropy was observed (eTable 7 in Supplement 1) in the mendelian randomization analysis. However, significant heterogeneity was observed for most metabolites (eTable 8 in Supplement 1), suggesting violation of assumption of mendelian randomization. We therefore considered the results of the weighted median method, as this has been shown to produce consistent results in the presence of heterogeneity.31 Significant mendelian randomization results were obtained after correcting for multiple testing using FDR < .05 (eFigure 9 in Supplement 1) when MDD was used as the exposure and metabolites as the outcome. Changes in 25 VLDLs (β [SE] range, 0.05 [0.03] to 0.11 [0.03]; FDR < 0.04), 5 IDL (β [SE] range, −0.09 [0.03] to 0.06 [0.03]; FDR < 0.03), 6 extra-large HDL subfractions (β [SE] < −0.07 [0.02]; FDR < 0.01), HDL–cholesteryl ester (β [SE], −0.05 [0.02]; FDR = 0.03), HDL-triglycerides (β [SE], 0.08 [0.03]; FDR = 0.01), and fatty acids, including monounsaturated fatty acids (β [SE], 0.10 [0.03]; FDR = 3.4 × 10−04), ratio of polyunsaturated fatty acids to monounsaturated fatty acids (β [SE], −0.12 [0.03]; FDR < 2.3 × 10−05), and omega-6 fatty acids (β [SE], −0.08 [0.03]; FDR = 2.4 × 10−03), appeared to be associated with genes that were associated with MDD. However, mendelian randomization was inconclusive about the association with the medium and large HDL subfractions, apoA1, citrate, pyruvate, alanine, total cholesteryl ester, and sphingomyelins (eFigure 9 in Supplement 1).

Integration of Human Gut Microbiome and Metabolic Signatures

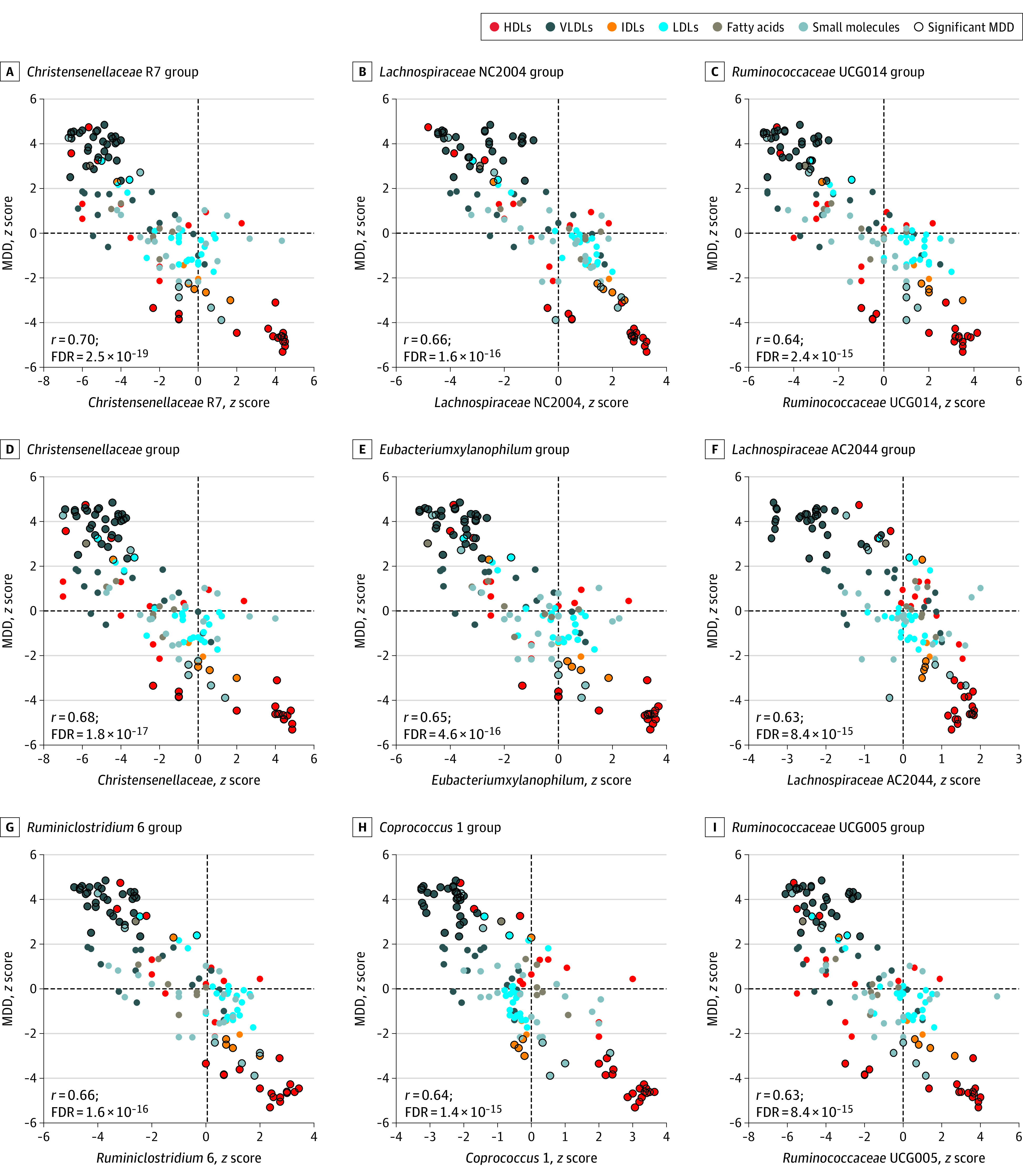

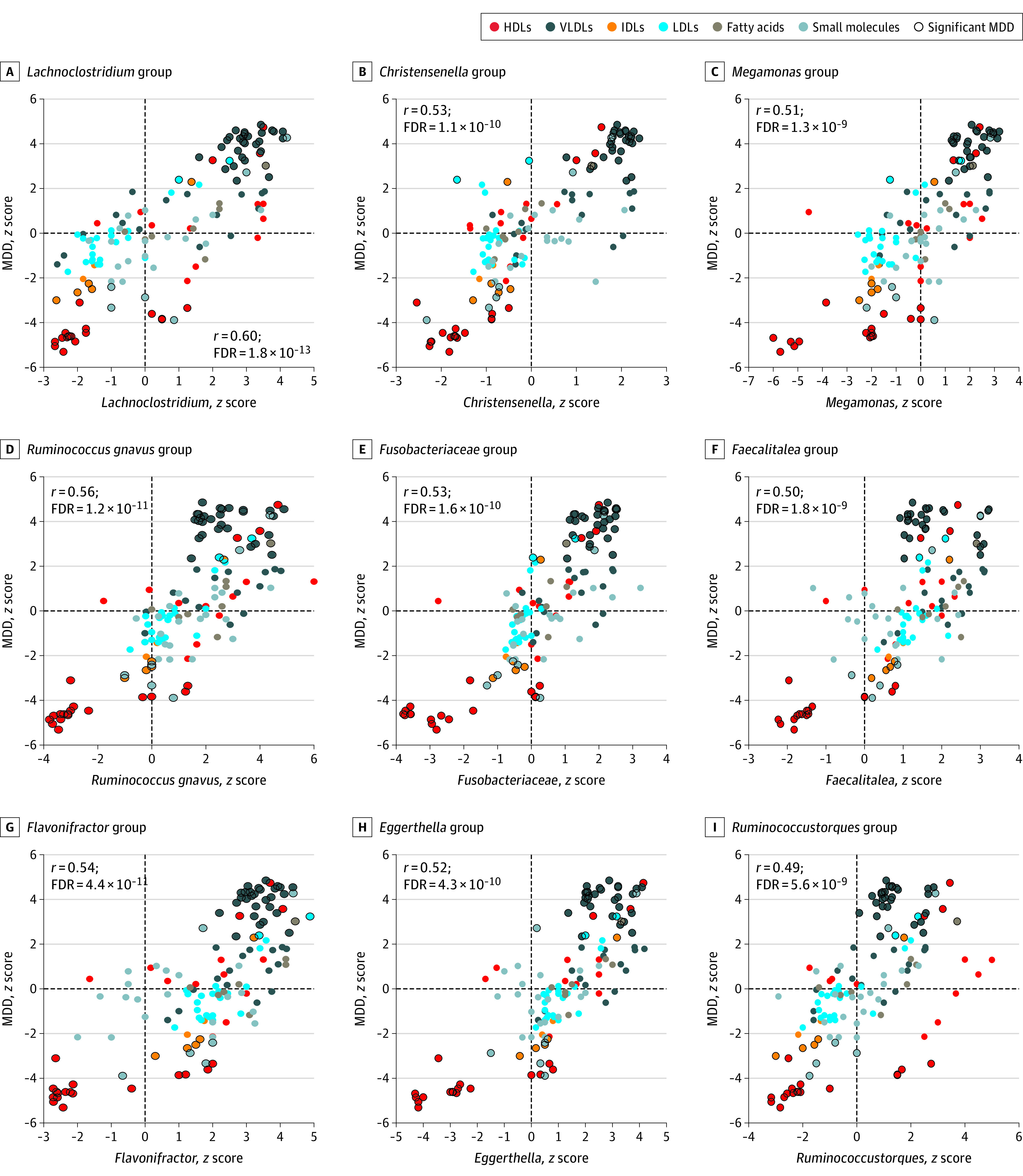

Results of correlation between the metabolic signature of MDD and the metabolic signatures of the gut microbial taxa are provided in eTable 9 in Supplement 1 and Figures 2 and 3). Figure 2 shows all taxa whose metabolic signatures showed significant negative correlation (r > −0.50; FDR < .05) with that of MDD, and Figure 3 illustrates all taxa whose metabolic signatures show significant positive correlation (r < 0.50; FDR < .05) with the metabolic signature of MDD. We henceforth refer to this correlation of the metabolic signatures of MDD and gut microbial taxa as a proxy association between MDD and gut microbiome. When comparing this proxy association with the direct association of depression with the gut microbiome from our previous independent study,18 we found a significant correlation (r = 0.58; P < 1 × 10−16) (eFigure 10 in Supplement 1). This finding suggests that the Nightingale platform can be used as a proxy measure for the microbiome and that the correlation of the microbiome and MDD is mainly associated with VLDL and HDL particles. Of note is that the bacteria that were associated with a healthy lipid profile (ie, increased levels of HDL subfractions and decreased VLDL lipid levels) were found to be decreased in individuals with MDD (Figure 2). Conversely, bacteria that were associated with an unhealthy lipid profile (ie, decreased levels of lipids in HDL particles and increased levels of lipids in VLDL) were found to be increased in individuals with MDD (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Association of Metabolic Profiles (z Scores) of Healthy Gut Microbiota and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).

Scatterplots showing correlations between the metabolic signatures of microbial taxa and MDD. Taxa that show inverse correlation with the metabolic signatures of MDD are shown. Each dot represents a metabolite. The x-axis shows the association of the metabolite with microbial taxa, and the y-axis shows the association of the metabolite with MDD. Different colors of the dots represent the class of the metabolite, and the metabolites highlighted with black circles are significantly associated with MDD in model 4.

Figure 3. Association of Metabolic Profiles (z Scores) of Unhealthy Microbiota and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).

Scatterplots showing the correlation between the metabolic signatures of microbial taxa and MDD. Taxa that show positive correlation with the metabolic signatures of MDD are shown. The x-axis shows the association of the metabolite with microbial taxa, and the y-axis shows the association of the metabolite with MDD. Different colors of the dots represent the class of the metabolite, and the metabolites highlighted with black circles are significantly associated with MDD in model 4.

Overall, we observed 223 bacterial taxa significantly associated with MDD using proxy association (corrected FDR < .05) (eFigure 11 and eTable 9 in Supplement 1). eFigure 11 in Supplement 1 shows the complete gut microbiome profile of individuals with MDD at hierarchical levels. Family Ruminococcaceae (r = −0.60; FDR = 2.9 × 10−13) and most of its genera were significantly negatively correlated with MDD. Several other families belonging to the order Clostridiales also showed significant negative correlation with MDD (ie, Clostridiaceae [r = −0.59; FDR = 8.8 × 10−13], Christensenellaceae [r = −0.68; FDR = 1.8 × 10−17], Peptostreptococcaceae [r = −0.50; FDR = 2.1 × 10−09], Defluviitaleaceae [r = −0.45; FDR = 9.4 × 10−08], and Peptococcaceae [r = −0.41; FDR = 2.3 × 10−06]). Families Lachnospiraceae (r = 0.43; FDR = 6.3 × 10−07) and Eubacteriaceae (r = 0.38; FDR = 1.3 × 10−05) were significantly positively correlated with MDD; however, some genera belonging to these families were significantly negatively correlated with MDD (eFigure 11 in Supplement 1). Further, several families belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria (Pseudomonadota), including Methanobacteriaceae, Rhodospirillaceae, Desulfovibrionaceae, Pasteurellaceae, Neisseriaceae, and Oxalobacteraceae, and phylum Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidota), including Porphyromonadaceae, Rikenellaceae, and Prevotellaceae, were significantly negatively correlated with MDD (eFigure 11 and eTable 9 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this cohort study, we identified 124 metabolites, including 49 novel associations, in the lipid and energy metabolism pathways associated with MDD. Novel metabolites include citrate and pyruvate, which are 2 key metabolites of the energy metabolism pathway. The metabolic shift observed in depression was associated with bacterial taxa belonging to order Clostridiales and phyla Proteobacteria/Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidetes/Bacteroidota. Mendelian randomization analysis suggested that changes in VLDLs, IDLs, and fatty acids were associated with MDD, but was inconclusive for the changes observed in HDLs, apoA1, or metabolites in the tricarboxylic acid cycle.

The finding that various VLDL particles and total monounsaturated fatty acids were increased and HDL particles and apoA1 were decreased in individuals with depression are consistent with findings of previous studies.10,32 Our study provides evidence suggesting that the microbiome was associated with the shift in VLDL/HDL levels in individuals with MDD. Most bacterial families belonging to the order Clostridiales and phyla Proteobacteria/Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidetes/Bacteroidota were decreased in individuals with MDD and were associated with high HDL and low VLDL levels in blood, while families Lachnospiracea and Eubacteriaceae were predicted to be increased in individuals with MDD and are associated with low HDLs and high VLDL levels in blood. Using this proxy method, we confirmed the findings of the previous studies as well as our own study on the association of the gut microbiome with depression.18,19,33 These include lower abundance of phyla Proteobacteria/Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidetes/Bacteroidota, family Ruminococcaceae, and genera Coprococcus and Ruminococcus and higher abundance of Flavonifractor and Eggerthella in individuals with MDD.19,33 Earlier studies have shown that gut microbiome is associated with the circulating lipids and has a bidirectional association with mitochondrial function.12,17 Members of microbiota from the order Clostridiales are known to provide a transforming growth factor β–enriched environment for promotion and accumulation of regulatory T cells in the gut.34 These regulatory T cells have been found to be reduced in individuals with mood disorders.35 We found several families belonging to the order Clostridiales associated with MDD in our proxy association. Our findings are in line with those of our previous study, wherein families within Clostridiales were found to be the predominant microbes associated with psychiatric disorders, including depression.36 Since the gut microbiome is mainly modulated by diet11,37 and the contribution of host genetics is small,38,39 it might explain the inconclusive mendelian randomization results for some of the metabolites, including medium and large HDLs and apoA1.

The second major finding in this study was the disruption in the mitochondrial metabolism (tricarboxylic acid/Krebs cycle). In individuals with MDD, we found significantly increased levels of pyruvate and decreased levels of citrate.40 Significantly increased levels of pyruvate and decreased levels of citrate in blood have been reported in individuals with bipolar depression,41 and increased mitochondrial activity–generating citrate and reduced oxidative stress parameters have been observed in patients with bipolar depression treated with lithium compared to untreated patients.42 Decreased citrate levels were found in the urine of rats in a chronic unpredictable mild stress–depression model.43,44 Extracellular citrate has also been used for neurotransmitter synthesis.40,45 In animal models of induced oxidative stress, oral administration of citrate was associated with a decrease in brain lipid peroxidation and inflammation, liver damage, and DNA fragmentation.46 Notably, 90% of the total citrate in the body is localized in bones.47,48 Osteoblast metabolic production of citrate provides the source of citrate in bone in the presence of zinc, which inhibits the oxidation of citrate in mitochondria.48,49 Citrate is released in the plasma during bone resorption.47 Decreased levels of blood citrate cause loss of bone citrate and osteoporosis.47 The association of depression and osteoporosis is well established;50 however, a mendelian randomization study did not find osteoporosis to be associated with depression.51 Interestingly, administration of vitamin D has been associated with an increase in plasma and bone citrate concentrations by inhibiting mitochondrial citrate oxidation.47 This implies that, if plasma citrate deficiency has an influence on major depression, the subgroup of individuals with MDD exhibiting low citrate levels may benefit from treatment with zinc and vitamin D supplements, both of which have shown to ameliorate symptoms of depression.52,53

Low citrate levels may also be a result of intestinal dysbiosis or impairment of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex that catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate into acetyl coenzyme (acetyl-CoA).54 One of the questions to answer in future studies is whether acetyl-CoA accounts for the observed association of MDD with lipids and mitochondrial metabolites citrate and pyruvate. Cholesterol synthesis initiates from acetyl-CoA.55 Acetyl-CoA is synthesized in mitochondria from the pyruvate, fatty acids, or amino acids (eg, phenylalanine, tyrosine, leucine, lysine, and tryptophan).56 Acetyl-CoA is transported out of the mitochondria after being converted into citrate.56 Cytosolic acetyl-CoA is used in lipid biosynthesis.57 We hypothesize that citrate, which we found to be decreased in individuals with depression, may be the key metabolite connecting the lipid and energy metabolism pathways via acetyl-CoA.

To our knowledge, this is the largest and most comprehensive study investigating the association of NMR-confirmed metabolites with major depression. The strengths of this study include the statistical power to detect robust associations, a comprehensive control for confounders, including lifestyle factors and medication use, identifying the direction of association using mendelian randomization, and the use of metabolomics to identify gut microbiome profiles of individuals with MDD.

Limitations

This study has limitations. One of its major weaknesses is that the Nightingale metabolomics platform is limited in the number of metabolites assessed and dominated by lipoproteins. A more diverse metabolomics platform might have improved the sensitivity in detecting proxy associations with the gut microbiome. Second, we included self-reported depression in our analysis, which might not reflect true MDD. Third, up to 95% of participants in the UK Biobank are identified as White, and thus these findings may not be generalizable to a diverse population. Despite limitations, our results on both metabolome and gut microbiome are consistent with those of the previous studies, and we replicated the novel findings in an independent study.

Conclusions

This cohort study identified that the metabolites involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle/energy metabolism were significantly altered in individuals with MDD compared to control individuals. We further showed that the metabolic shift observed in individuals with MDD was consistent with the gut dysbiosis observed in this group, suggesting an interplay of the host gut microbiome and the blood metabolome in individuals with MDD. Future experimental studies and trials are needed to resolve whether metabolic profiles in patients improve after intervention with respect to their gut microbiomes.

eMethods

eTable 1. Results for all models for Lifetime MDD

eTable 2. Results of sensitivity analysis

eTable 3. Significant Findings and replication in BBMRI-NL Study

eTable 4. Novel Findings of the study

eTable 5. Results of replication in the PReDICT study

eTable 6. Results of Mendelian Randomization analysis

eTable 7. Results of horizontal pleiotropy in MR

eTable 8. Results of Heterogeneity test in Mendelian Randomization

eTable 9. Correlation between MDD and Microbiome metabolic signatures

eFigure 1. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis

eFigure 2. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis for lifetime MDD and recurrent MDD for model 1

eFigure 3. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis for lifetime MDD and recurrent MDD for model 2

eFigure 4. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis for lifetime MDD and recurrent MDD for model 3

eFigure 5. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis for lifetime MDD and recurrent MDD for model 4

eFigure 6. Correlation structure of 124 metabolites associated with lifetime major depression

eFigure 7. Scatter plot of effect estimates (MDD) from model 4 and sensitivity analysis by removing individuals on antidepressants

eFigure 8. Significantly associated metabolites with MDD in model 4 and the results of replication in BBMRI-NL study

eFigure 9. Results of Mendelian Randomization for the 124 associated metabolites in model 4

eFigure 10. Scatter plot of direct and proxy association of microbiome with major depression

eFigure 11. Hierarchical illustration of all healthy and pathogenic bacteria that showed significant correlation (r > 0.3 & FDR < 0.05) with MDD metabolic profile

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):153-160. doi: 10.1002/wps.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedrich MJ. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1517. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rezin GT, Amboni G, Zugno AI, Quevedo J, Streck EL. Mitochondrial dysfunction and psychiatric disorders. Neurochem Res. 2009;34(6):1021-1029. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9865-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parekh A, Smeeth D, Milner Y, Thure S. The role of lipid biomarkers in major depression. Healthcare (Basel). 2017;5(1):5. doi: 10.3390/healthcare5010005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.F Guerreiro Costa LN, Carneiro BA, Alves GS, et al. Metabolomics of major depressive disorder: a systematic review of clinical studies. Cureus. 2022;14(3):e23009. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Li J, Zheng P, et al. Plasma lipidomics reveals potential lipid markers of major depressive disorder. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408(23):6497-6507. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9768-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen JJ, Xie J, Li WW, et al. Age-specific urinary metabolite signatures and functions in patients with major depressive disorder. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(17):6626-6637. doi: 10.18632/aging.102133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madamanchi NR, Runge MS. Mitochondrial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2007;100(4):460-473. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258450.44413.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh NI, Gerschenson M, Bennett K, et al. Lipoprotein concentration, particle number, size and cholesterol efflux capacity are associated with mitochondrial oxidative stress and function in an HIV positive cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239(1):50-54. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bot M, Milaneschi Y, Al-Shehri T, et al. ; BBMRI-NL Metabolomics Consortium . Metabolomics profile in depression: a pooled analysis of 230 metabolic markers in 5283 cases with depression and 10,145 controls. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87(5):409-418. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman TM, Shively CA, Register TC, et al. Diet, obesity, and the gut microbiome as determinants modulating metabolic outcomes in a non-human primate model. Microbiome. 2021;9(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01069-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu J, Bonder MJ, Cenit MC, et al. The gut microbiome contributes to a substantial proportion of the variation in blood lipids. Circ Res. 2015;117(9):817-824. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castro-Mejía JL, Khakimov B, Aru V, et al. Gut microbiome and its cofactors are linked to lipoprotein distribution profiles. Microorganisms. 2022;10(11):2156. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10112156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia B, Zou Y, Han X, Bae JW, Jeon CO. Gut microbiome-mediated mechanisms for reducing cholesterol levels: implications for ameliorating cardiovascular disease. Trends Microbiol. 2023;31(1):76-91. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2022.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Roy T, Lécuyer E, Chassaing B, et al. The intestinal microbiota regulates host cholesterol homeostasis. BMC Biol. 2019;17(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12915-019-0715-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakaya K, Ikewaki K. Microbiota and HDL metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2018;29(1):18-23. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franco-Obregón A, Gilbert JA. The microbiome-mitochondrion connection: common ancestries, common mechanisms, common goals. mSystems. 2017;2(3):e00018-17. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00018-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radjabzadeh D, Bosch JA, Uitterlinden AG, et al. Gut microbiome-wide association study of depressive symptoms. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7128. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34502-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson CA, Diaz-Arteche C, Eliby D, Schwartz OS, Simmons JG, Cowan CSM. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression—a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;83:101943. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vojinovic D, Radjabzadeh D, Kurilshikov A, et al. Relationship between gut microbiota and circulating metabolites in population-based cohorts. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5813. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13721-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zierer J, Jackson MA, Kastenmüller G, et al. The fecal metabolome as a functional readout of the gut microbiome. Nat Genet. 2018;50(6):790-795. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0135-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritchie SC, Surendran P, Karthikeyan S, et al. Quality control and removal of technical variation of NMR metabolic biomarker data in ∼120,000 UK Biobank participants. medRxiv. 2021:2021.09.24.21264079. doi: 10.1101/2021.09.24.21264079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Julkunen H, Cichonska A, Slagboom PE, Wurtz P; Nightingale Health UKBI . Metabolic biomarker profiling for identification of susceptibility to severe pneumonia and COVID-19 in the general population. Elife. 2021;10:e63033. doi: 10.7554/eLife.63033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunlop BW, Binder EB, Cubells JF, et al. Predictors of remission in depression to individual and combined treatments (PREDICT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:106. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, Gayle AA, Wang J, Zhang H, Cardinal-Fernández P. Comparing baseline characteristics between groups: an introduction to the CBCgrps package. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(24):484. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.09.39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity (Edinb). 2005;95(3):221-227. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G. Reading mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 2018;362:k601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, et al. The MR-base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife. 2018;7:e34408. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, et al. ; 23andMe Research Team; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(3):343-352. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40(4):304-314. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segoviano-Mendoza M, Cárdenas-de la Cruz M, Salas-Pacheco J, et al. Hypocholesterolemia is an independent risk factor for depression disorder and suicide attempt in northern Mexican population. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1596-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGuinness AJ, Davis JA, Dawson SL, et al. A systematic review of gut microbiota composition in observational studies of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(4):1920-1935. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01456-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imdad S, Lim W, Kim JH, Kang C. Intertwined relationship of mitochondrial metabolism, gut microbiome and exercise potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2679. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauer ME, Teixeira AL. Neuroinflammation in mood disorders: role of regulatory immune cells. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2021;28(3):99-107. doi: 10.1159/000515594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Ma Y, Bao Z, et al. Clostridiales are predominant microbes that mediate psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;130:48-56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh RK, Chang HW, Yan D, et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med. 2017;15(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1175-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scepanovic P, Hodel F, Mondot S, et al. ; Milieu Intérieur Consortium . A comprehensive assessment of demographic, environmental, and host genetic associations with gut microbiome diversity in healthy individuals. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0747-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothschild D, Weissbrod O, Barkan E, et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature. 2018;555(7695):210-215. doi: 10.1038/nature25973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mycielska ME, Milenkovic VM, Wetzel CH, Rümmele P, Geissler EK. Extracellular citrate in health and disease. Curr Mol Med. 2015;15(10):884-891. doi: 10.2174/1566524016666151123104855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshimi N, Futamura T, Kakumoto K, et al. Blood metabolomics analysis identifies abnormalities in the citric acid cycle, urea cycle, and amino acid metabolism in bipolar disorder. BBA Clin. 2016;5:151-158. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Machado-Vieira R, Andreazza AC, Viale CI, et al. Oxidative stress parameters in unmedicated and treated bipolar subjects during initial manic episode: a possible role for lithium antioxidant effects. Neurosci Lett. 2007;421(1):33-36. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu XJ, Li ZY, Li ZF, et al. Urinary metabonomic study using a CUMS rat model of depression. Magn Reson Chem. 2012;50(3):187-192. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng S, Yu M, Lu X, et al. Urinary metabonomic study on biochemical changes in chronic unpredictable mild stress model of depression. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411(3-4):204-209. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westergaard N, Sonnewald U, Unsgård G, Peng L, Hertz L, Schousboe A. Uptake, release, and metabolism of citrate in neurons and astrocytes in primary cultures. J Neurochem. 1994;62(5):1727-1733. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62051727.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdel-Salam OM, Youness ER, Mohammed NA, Morsy SM, Omara EA, Sleem AA. Citric acid effects on brain and liver oxidative stress in lipopolysaccharide-treated mice. J Med Food. 2014;17(5):588-598. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.0065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Costello LC, Franklin RB. Plasma citrate homeostasis: how it is regulated; and its physiological and clinical implications. an important, but neglected, relationship in medicine. HSOA J Hum Endocrinol. 2016;1(1). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Costello LC, Franklin RB, Reynolds MA, Chellaiah M. The important role of osteoblasts and citrate production in bone formation: “osteoblast citration” as a new concept for an old relationship. Open Bone J. 2012;4. doi: 10.2174/1876525401204010027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franklin RB, Chellaiah M, Zou J, Reynolds MA, Costello LC. Evidence that osteoblasts are specialized citrate-producing cells that provide the citrate for incorporation into the structure of bone. Open Bone J. 2014;6:1-7. doi: 10.2174/1876525401406010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cizza G, Primma S, Coyle M, Gourgiotis L, Csako G. Depression and osteoporosis: a research synthesis with meta-analysis. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42(7):467-482. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1252020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He B, Lyu Q, Yin L, Zhang M, Quan Z, Ou Y. Depression and osteoporosis: a mendelian randomization study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2021;109(6):675-684. doi: 10.1007/s00223-021-00886-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petrilli MA, Kranz TM, Kleinhaus K, et al. The emerging role for zinc in depression and psychosis. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:414. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaffer JA, Edmondson D, Wasson LT, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(3):190-196. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomas GW, Mains CW, Slone DS, Craun ML, Bar-Or D. Potential dysregulation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex by bacterial toxins and insulin. J Trauma. 2009;67(3):628-633. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a8b415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lent-Schochet D, Jialal I. Biochemistry, Lipoprotein Metabolism. StatPearls; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhagavan NV, Ha C-E. Lipids I: Fatty Acids and Eicosanoids. In: Bhagavan NV, Ha C-E, eds. Essentials of Medical Biochemistry. Second Edition. Academic Press; 2015:269-297. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mycielska ME, Patel A, Rizaner N, et al. Citrate transport and metabolism in mammalian cells: prostate epithelial cells and prostate cancer. Bioessays. 2009;31(1):10-20. doi: 10.1002/bies.080137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eTable 1. Results for all models for Lifetime MDD

eTable 2. Results of sensitivity analysis

eTable 3. Significant Findings and replication in BBMRI-NL Study

eTable 4. Novel Findings of the study

eTable 5. Results of replication in the PReDICT study

eTable 6. Results of Mendelian Randomization analysis

eTable 7. Results of horizontal pleiotropy in MR

eTable 8. Results of Heterogeneity test in Mendelian Randomization

eTable 9. Correlation between MDD and Microbiome metabolic signatures

eFigure 1. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis

eFigure 2. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis for lifetime MDD and recurrent MDD for model 1

eFigure 3. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis for lifetime MDD and recurrent MDD for model 2

eFigure 4. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis for lifetime MDD and recurrent MDD for model 3

eFigure 5. Results of metabolome-wide association analysis for lifetime MDD and recurrent MDD for model 4

eFigure 6. Correlation structure of 124 metabolites associated with lifetime major depression

eFigure 7. Scatter plot of effect estimates (MDD) from model 4 and sensitivity analysis by removing individuals on antidepressants

eFigure 8. Significantly associated metabolites with MDD in model 4 and the results of replication in BBMRI-NL study

eFigure 9. Results of Mendelian Randomization for the 124 associated metabolites in model 4

eFigure 10. Scatter plot of direct and proxy association of microbiome with major depression

eFigure 11. Hierarchical illustration of all healthy and pathogenic bacteria that showed significant correlation (r > 0.3 & FDR < 0.05) with MDD metabolic profile

Data sharing statement