Abstract

Background

Pediatric exposures to unsafe sources of water, unsafely managed sanitation, and animals are prevalent in low- and middle-income countries. In the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa case-control study, we examined associations between these risk factors and moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD) in children <5 years old in The Gambia, Kenya, and Mali.

Methods

We enrolled children <5 years old seeking care for MSD at health centers; age-, sex-, and community-matched controls were enrolled at home. Conditional logistic regression models, adjusted for a priori confounders, were used to evaluate associations between MSD and survey-based assessments of water, sanitation, and animals living in the compound.

Results

From 2015 to 2018, 4840 cases and 6213 controls were enrolled. In pan-site analyses, children with drinking water sources below “safely managed” (onsite, continuously accessible sources of good water quality) had 1.5–2.0-fold higher odds of MSD (95% confidence intervals [CIs] ranging from 1.0 to 2.5), driven by rural site results (The Gambia and Kenya). In the urban site (Mali), children whose drinking water source was less available (several hours/day vs all the time) had higher odds of MSD (matched odds ratio [mOR]: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.1, 1.7). Associations between MSD and sanitation were site-specific. Goats were associated with slightly increased odds of MSD in pan-site analyses, whereas associations with cows and fowl varied by site.

Conclusions

Poorer types and availability of drinking water sources were consistently associated with MSD, whereas the impacts of sanitation and household animals were context-specific. The association between MSD and access to safely managed drinking water sources post-rotavirus introduction calls for transformational changes in drinking water services to prevent acute child morbidity from MSD.

Keywords: diarrhea, water, sanitation, animal feces

We assessed water, sanitation, and animal-associated risk factors for moderate-to-severe diarrhea in children in a matched case-control study. Less availability (hours/day) and access to quality drinking water were consistent risk factors; poor sanitation and animal ownership were context-specific risk factors.

More than 500 000 deaths, 10% of deaths in children under 5 years of age, are attributed to diarrhea annually [1, 2]. Previous estimates suggest unsafe water and sanitation cause 72% and 56% of diarrheal deaths, respectfully, in children <5 years old [3]. Nonetheless, water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) coverage improved globally: use of at least “basic” water services—improved water sources within 30 minutes round trip for collection—increased from 81% to 89% from 2000 to 2015; use of at least “basic” sanitation facilities—improved facilities not shared with other households—increased from 59% to 68% [4]. Both are focuses of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [4, 5]. Alongside these improvements, other factors—including the introduction of vaccines for rotavirus [6], cholera [7], and typhoid [8] and improved quality and access to healthcare [9]—have the potential to reduce diarrheal morbidity and mortality. Updated evidence of the impact of WASH on severe child morbidity—moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD)—in low-income countries following these changes, and of the relative importance of animal feces as a potential cause of MSD [10, 11], is needed.

The Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) study was a matched case-control study of clinically defined MSD in children <5 years old in 3 sites in sub-Saharan Africa (The Gambia, Kenya, and Mali) that previously participated in the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) [12, 13] and subsequently introduced rotavirus vaccine. VIDA collected data on household demographics, assets, education, drinking water sources, sanitation facilities, onsite animals, and other factors. In this study, we aimed to examine associations between survey-based water and sanitation conditions (as measured by associated SDG ladders), animal presence, and MSD in children enrolled in VIDA. Data on associations between WASH and animal characteristics and MSD can inform preventive efforts to maximize impact on acute pediatric clinical illness.

METHODS

Study Sites

Of 7 study sites in the GEMS, 3 in which rotavirus infection accounted for the highest attributable fraction of MSD in the first 2 years of life and that introduced rotavirus vaccine before 2015 were selected for inclusion in the VIDA study [12–14]. These sites were in The Gambia (2 rural areas, Basse and Bansang, the latter site not included in GEMS), Mali (2 urban neighborhoods in Bamako), and Kenya (rural area, Siaya County). Each site maintained a censused population with an ongoing demographic surveillance system (DSS) from which cases and controls were selected.

Study Design

Methods of the VIDA study were similar to GEMS [13] as described elsewhere [15]. In brief, VIDA was a matched case-control study: case-children were <5 years old and sought care for MSD at sentinel health centers within the DSS areas. MSD was defined as ≥3 loose stools within a 24-hour period with one of the following: sunken eyes, need for intravenous fluids, loss of skin turgor, dysentery, or admission to the health center. Each case was matched to 1–3 control children who were free from diarrhea in the 7 days preceding enrollment, randomly selected from the site-specific DSS database within 14 days of case presentation, and matched to each case by age group (0–11, 12–23, and 24–59 months), sex, and neighborhood. Consent was obtained from the caregiver at enrollment. This study was approved by the ethical review committees at the University of Maryland, Baltimore (HP-00062472), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (reliance agreement 6729), The Gambia Government/Medical Research Council/Gambia at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (1409), the Comité d'Ethique de la Faculté de Médecine, de Pharmacie, et d'Odonto-Stomatologie, Bamako, Mali (no number), and the Kenya Medical Research Institute Scientific & Ethics Review Unit in Siaya County, Kenya (SSE 2996). Informed, written consent was obtained from all participants prior to initiation of study procedures.

Data Collection

Data on household demographics, assets, caregiver's education, animals living in the compound, and water and sanitation conditions (using Joint Monitoring Program [JMP] criteria for water and sanitation service ladders [4]) were collected by survey (ie, did not include water testing-based or other laboratory parameters) at enrollment, which took place at the health facility for cases, and at home for controls. The JMP water and sanitation ladder levels are described in Supplementary Material [4].

Analyses

We used conditional logistic regression to compute matched odds ratios (mOR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for associations between MSD and water and sanitation ladder levels (including subcomponents) and presence/absence of animals in the compound using R version 3.5.2 [16]. We conducted (1) pan-site analyses of data from all 3 sites in a single model, accounting for clustering by site using a random effect and (2) site-specific analyses. Within analyses, we examined (1) “individual” unadjusted associations between the variable of interest and MSD; and (2) “combined,” adjusted models assessing all variables of interest (drinking water, sanitation, and animals) and MSD. Beyond the water and sanitation ladder levels and animal risk factors, we analyzed subcomponents of ladder levels (eg, water availability, sharing of sanitation facilities) to examine risk factors and compare to previous GEMS analyses [17]. All multivariable models were adjusted for caregiver's education, household assets, and fuel source, described in Supplementary Material, as in other VIDA analyses [18].

RESULTS

Survey-Based Drinking Water Source Characteristics

The VIDA study enrolled 4840 cases/6213 controls: 1678 cases/2138 controls in The Gambia, 1608 cases/1980 controls in Mali, and 1554 cases/2095 controls in Kenya. Most caregivers (73%) reported the child had drinking water sources that met survey-based criteria for safely managed [4] (Mali [89%], The Gambia [78%], Kenya [52%]; Table 1). Onsite piped water sources were uncommon in Mali (17%), The Gambia (11%), and Kenya (<2%). Public taps were the most common in Mali (65%) and The Gambia (50%) but not Kenya (17%), where the most common sources were rainwater (34%) and surface water (23%) (Supplementary Table 1). Almost all children were given stored water (99% in The Gambia and Mali, 89% in Kenya, Table 1) despite caregivers reporting high water availability: available “all the time” in Mali and Kenya (>80%) and available “all the time” (53%) or “several hours/day” (45%) in The Gambia.

Table 1.

Drinking Water-Related Characteristics Among Cases and Controls by Site in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) Study, 2015–2018

| Variable | Pan-site (%) | The Gambia (%) | Kenya (%) | Mali (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water ladder | ||||

| ȃSafely manageda | 8023 (73) | 2960 (78) | 1885 (52) | 3178 (89) |

| ȃBasicb | 484 (4.4) | 75 (2.0) | 372 (10) | 37 (1.0) |

| ȃLimitedc | 984 (8.9) | 169 (4.4) | 445 (12) | 370 (10) |

| ȃUnimprovedd | 699 (6.3) | 587 (15) | 109 (3.0) | 3 (0.08) |

| ȃSurface watere | 862 (7.8) | 24 (0.63) | 838 (23) | 0 |

| Drinks onsite piped waterf | 1100 (10) | 428 (11) | 59 (1.6) | 613 (17) |

| Child given stored water | 10 559 (96) | 3776 (99) | 3245 (89) | 3538 (99) |

| Water availability | ||||

| ȃAll the time | 8021 (73) | 2022 (53) | 2968 (81) | 3031 (84) |

| ȃSeveral hours per day | 2415 (22) | 1701 (45) | 202 (5.5) | 512 (14) |

| ȃA few times per week | 543 (4.9%) | 87 (2.3) | 422 (12) | 34 (0.95) |

| ȃLess frequent than a few times per week | 73 (0.66) | 5 (0.13) | 57 (1.6) | 11 (0.31) |

Water for drinking from an improved source (piped water, boreholes or tubewells, protected dug wells, protected springs, rainwater, and packaged or delivered water) that is located onsite, available when needed, and free of fecal and chemical contamination [4].

Water for drinking from an improved source where collection time is ≤30 minutes round trip, inclusive of queueing [4].

Water for drinking from an improved source where collection time is >30 minutes round trip, inclusive of queueing [4].

Water for drinking collected from an unprotected spring or unprotected dug well [4].

Water for drinking collected from a river, dam, lake, pond, stream, canal, or irrigation ditch [4].

Onsite piped water: within the household or in the yard.

Survey-Based Household Sanitation Characteristics

Almost all households reported having access to a sanitation facility (99%, 94%, 100% in The Gambia, Kenya, and Mali, respectively) (Table 2). Most Gambian households (90%), and some in Mali (55%) and Kenya (29%), had a private sanitation facility (not shared with other households). Gambian households had mostly at least basic (34%) and unimproved (61%) sanitation; Kenyan households had at least basic (13%), limited (31%), and unimproved sanitation (50%); Malian households had at least basic (55%) or limited sanitation (44%). Pit latrines were the most common sanitation facility (Supplementary Table 2), although 55% lacked a cleanable slab (making them “unimproved”; those with a slab meet higher sanitation ladder criteria). Pit latrines were reported by 93% in The Gambia (slabs: 32% with, 61% without); 88% in Kenya (slabs: 38% with, 50% without); and 96% in Mali (slabs: 96% with, < 1% without) (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2.

Sanitation-Related Characteristics Among Cases and Controls by Site in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) Study, 2015–2018

| Variable | Pan-site (%) | The Gambia (%) | Kenya (%) | Mali (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No facility | 278 (2.5) | 56 (1.5) | 222 (6.1) | 0 |

| Private facility | 6470 (59) | 3416 (90) | 1064 (29) | 1990 (55) |

| Facility shared by 1–2 HHs | 2417 (22) | 242 (6.3) | 1542 (42) | 633 (18) |

| Facility shared by ≥3 HHs | 1888 (17) | 102 (2.7) | 821 (23) | 965 (27) |

| Sanitation ladder | ||||

| ȃAt least basica | 3723 (34) | 1286 (34) | 469 (13) | 1968 (55) |

| ȃLimitedb | 2834 (26) | 138 (3.6) | 1121 (31) | 1575 (44) |

| ȃUnimprovedc | 4217 (38) | 2336 (61) | 1836 (50) | 45 (1.3) |

| ȃOpen defecationd | 279 (2.5) | 56 (1.5) | 223 (6.1) | 0 |

Abbreviation: HH, household.

“At least basic” encompasses the highest 2 levels of the sanitation ladder: safely managed (use of improved sanitation facilities—including flush or pour flush toilets to piped sewers, septic tanks, or pit latrines; ventilated improved pit latrines; composting toilets; and pit latrines with slabs—that are not shared with other households and where excreta are safely disposed of onsite/in the system or transported and treated offsite) and basic (use of improved sanitation facilities that are not shared with other households, but whose safe disposal or treatment is unknown) [4].

Use of sanitation facilities that are improved but shared between ≥2 households [4].

Use of pit latrines without a slab or platform, hanging latrines, or bucket latrines [4].

Disposal of human feces in open spaces or bodies of water or with solid waste (ie, not into sanitation facilities) [4].

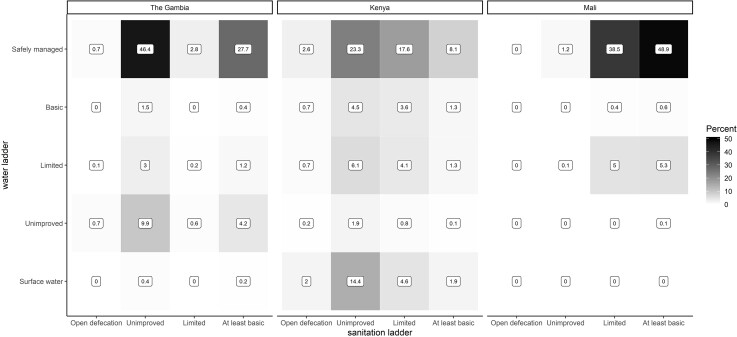

Combined Water and Sanitation Ladders

Overall, 49% of households in Mali, 28% in The Gambia, and 8% in Kenya met the highest levels for both water and sanitation ladders (Figure 1). Most other households had safely managed water and unimproved sanitation (46%) in The Gambia and safely managed water and limited sanitation (39%) in Mali. In Kenya, combined categories varied: 23% had safely managed water and unimproved sanitation, 18% had safely managed water and limited sanitation, and 14% had surface water and unimproved sanitation.

Figure 1.

Heatmap distribution of VIDA study households along the water and sanitation ladders, by study site. Numbers represent the percentages of households in given water/sanitation ladder levels for each study site. Abbreviation: VIDA, Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa.

Survey-Based Reporting of Animals Living in Compound

Almost all households had animals living in the compound with the enrolled study child (>99% per site, Table 3). Rodents (98% in Mali, 93% in The Gambia, 45% in Kenya), (82% in The Gambia, 92% in Kenya, 39% in Mali) and ruminants (cows, goats, or sheep: 86% in The Gambia, 77% in Kenya, 21% in Mali) were most common.

Table 3.

Animals Living in Compound With Cases and Controls by Site in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) Study, 2015–2018

| Variable | Pan-site (%) | The Gambia (%) | Kenya (%) | Mali (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No animal | 67 (0.61) | 20 (0.52) | 37 (1.0) | 10 (0.28) |

| Cats | 4105 (37) | 1358 (36) | 2593 (71) | 154 (4.3) |

| Cows | 3972 (36) | 1439 (38) | 2500 (69) | 33 (0.92) |

| Dogs | 3590 (33) | 1146 (30) | 2319 (64) | 125 (3.5) |

| Fowl | 7893 (71) | 3137 (82) | 3371 (92) | 1385 (39) |

| Goats | 4516 (41) | 2824 (74) | 1644 (45) | 48 (1.3) |

| Pigs | 484 (4.4) | 2 (0.05) | 480 (13) | 2 (0.06) |

| Rodents | 8684 (79) | 3542 (93) | 1630 (45) | 3512 (98) |

| Sheep | 4595 (42) | 2574 (68) | 1272 (35) | 749 (21) |

| Othersa | 22 (0.20) | 5 (0.13) | 9 (0.25) | 8 (0.22) |

| Any ruminants | 6862 (62) | 3281 (86) | 2816 (77) | 765 (21) |

Includes mostly rabbits and turtles/tortoises.

Water, Sanitation, and Animal Risk Factors for MSD

Findings from individual (Supplementary Tables 3–5) and combined-adjusted (Table 4) models were similar; thus we present combined-adjusted pan-site and site-specific models (Table 4). Compared to those with safely managed water, children in households with poorer drinking water levels had higher odds of MSD in the pan-site model: basic water service mOR: 1.5 (95% CI: 1.2–1.8); limited: 1.5 (1.0, 2.2); unimproved: 1.6 (1.0, 2.5); and surface water: 2.0 (1.6, 2.4). In The Gambia, each water service level below safely managed was associated with higher odds of MSD: basic water mOR: 1.9 (95% CI: 1.1, 3.4); limited: 3.0 (2.1, 4.3); unimproved: 2.2 (1.7, 2.8); and surface water: 2.9 (1.2, 6.7). In Kenya, basic (mOR: 1.4 [95% CI: 1.1, 1.8]), limited (1.5 [1.2, 1.9]), and surface water (1.8 [1.4, 2.2]) were associated with higher odds of MSD.

Table 4.

Adjusted Matched Odds Ratios (mOR) of Moderate-to-Severe Diarrhea (MSD) for Water, Sanitation, and Animal-Associated Risk Factors in the VIDA Study, 2015–2018 (Combined Adjusted Modelsa)

| Variable | Pan-site mOR (95% CI)b | Site-specific | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Gambia mOR (95% CI) | Kenya mOR (95% CI) | Mali mOR (95% CI) | ||

| Water ladder | ||||

| ȃSafely managed | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| ȃBasic | 1.48 (1.24, 1.78) | 1.93 (1.10, 3.38) | 1.39 (1.09, 1.77) | 1.07 (.54, 2.11) |

| ȃLimited | 1.47 (.97, 2.23) | 2.98 (2.06, 4.32) | 1.51 (1.20, 1.91) | .96 (.75, 1.22) |

| ȃUnimproved | 1.59 (1.01, 2.53) | 2.16 (1.67, 2.78) | .77 (.48, 1.22) | .75 (.07, 8.55) |

| ȃSurface water | 1.95 (1.58, 2.41) | 2.85 (1.22, 6.67) | 1.76 (1.43, 2.17) | … |

| Sanitation ladder | ||||

| ȃAt least basic | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| ȃLimited | .96 (.91, 1.01) | .98 (.67, 1.45) | 1.39 (1.10, 1.75) | .94 (.81, 1.09) |

| ȃUnimproved | .67 (.50, .90) | .55 (.48, .65) | 1.10 (.88, 1.38) | .68 (.36, 1.29) |

| ȃOpen defecation/no facility | .40 (.24, .68) | 1.12 (.59, 2.11) | .39 (.27, .58) | … |

| Animals living in compound | ||||

| ȃCows | 1.23 (.57, 2.65) | 2.25 (1.87, 2.70) | .71 (.60, .84) | 1.74 (.85, 3.57) |

| ȃFowl | .83 (.65, 1.06) | 1.16 (.95, 1.41) | .64 (.48, .84) | .71 (.61, .82) |

| ȃGoats | 1.06 (1.05, 1.06) | 1.11 (.92, 1.34) | 1.12 (.96, 1.31) | 1.03 (.57, 1.86) |

| ȃSheep | .94 (.80, 1.09) | .88 (.74, 1.05) | .85 (.72, 1.00) | 1.16 (.97, 1.38) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; VIDA, Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa.

Adjusted for caregivers' education, assets, and type of fuel, in addition to variables shown. All variables included in a single model.

Pan-site model includes all sites with a random effect for site.

Compared with those with at least basic sanitation, children with unimproved sanitation (mOR: 0.7 [95% CI: .5, .9]) and without a facility (open defecation: 0.4 [.2, .7]) had lower odds of MSD in the pan-site model, mirroring site-specific findings in The Gambia (unimproved sanitation mOR: 0.6 [95% CI: .5, .7]) and Kenya (open defecation mOR: 0.4 [.3, .6]). However, children with limited (shared) sanitation had 1.4-fold increased odds of MSD in Kenya (95% CI: 1.1, 1.8). No water or sanitation ladder levels were associated with MSD in Mali.

Children from households with goats had 6% higher odds of MSD in the pan-site model (95% CI: 1.05, 1.06). Children from households with cows had 2.3-fold higher odds of MSD in The Gambia (95% CI: 1.9, 2.7) but lower odds of MSD in Kenya (mOR: 0.7 [95% CI: .6, .8]). Children from households with fowl had lower odds of MSD in Kenya (mOR: 0.6 [95% CI: .5, .8]) and Mali (0.7 [.6, .8]).

Among subcomponents of water and sanitation ladder variables tested (Supplementary Table 6A), children in households with water available a few times per week (mOR: 1.5 [95% CI: 1.3, 1.6]) or less often (1.9 [1.8, 2.1]) had higher odds of MSD compared those with water available all the time. Children in Kenya followed this trend. Compared with children with water available all the time, children with water available several hours per day had lower odds of MSD in The Gambia (0.5 [.4, .6]), but 1.9-fold higher odds of MSD (95% CI: 1.5, 2.5) in Mali. Sharing a sanitation facility with ≥3 households (vs having a private facility) was associated with 2.4-fold higher odds of MSD (95% CI: 1.9, 2.9) in Kenya.

Compared with those with improved sources, children who drank from unimproved sources had higher odds of MSD in the pan-site model (mOR: 1.5 [95% CI: 1.2, 1.9]), The Gambia (1.9, [1.5, 2.5]), and Kenya (1.3 [1.1, 1.6]) (Supplementary Table 6B).

DISCUSSION

In pan-site and rural site analyses, we observed strong, positive associations between MSD in children <5 years old and reported water sources that were lower on the JMP water ladder and therefore likely to deliver poorer water quality and/or be less accessible. However, associations between survey-based assessments of sanitation or animals and MSD varied by site. Water availability (hours per day available) was the only association between water and sanitation conditions and MSD in the urban site (Mali), suggesting more complex, unmeasured environmental exposure pathways in cities.

Analyses of water, sanitation, and animal associations with clinical MSD can inform community preventive measures to maximize impact on preventing acute child morbidity from severe diarrhea. These analyses complement analyses of water, sanitation, and animal associations with enteric pathogen carriage [19], which focus on broader prevention of enteric pathogen exposure—regardless of where subsequent development of clinical diarrhea—yet may inform longer-term developmental outcomes.

In pan-site and site-specific analyses in The Gambia and Kenya, levels of the water ladder below “onsite, continuously supplied water from an improved source” (survey-based criteria for “safely managed” water, the highest JMP water ladder level) were associated with higher odds of MSD. However, we did not test water sources for fecal and chemical contamination—the other criteria for safely managed water [4]. Lower levels of the drinking water ladder include water from less accessible improved sources (basic: not onsite but ≤30 minutes round-trip; limited: > 30 minutes round-trip), and water from less-protected sources (more likely to have fecal or other contamination): unimproved or surface water. Higher odds of MSD in children with basic water than in children with safely managed water supports the focus on universal access to safely managed water in SDG 6.1 [4]. Limiting focus to “basic” services alone (SDG 1.4) [4] may leave children at risk for MSD, as evidence from this and other studies [20, 21] suggests additional reductions in diarrhea and child morbidity exist with continuously supplied onsite water.

In the urban site (Bamako, Mali), lower water availability (several hours per day) was associated with higher odds of MSD, but other documented water and sanitation conditions were not associated with MSD. Inconsistent water availability in a primarily piped water supply in the Mali site suggests interruptions in service, increasing reliance on stored water, and the chance of compromises in the system (eg, cross connections, low or negative pressure, or infiltration of the water line) that can introduce fecal contamination [22] and contribute to diarrhea and dysentery [23–25]. The absence of other water and sanitation associations with MSD may reflect a relative uniformity of services in the study population—82% piped in-yard or public tap water, 96% pit latrines with a slab—limiting the ability to detect differences. Furthermore, urban environments may warrant examination of other complex exposure pathways, such as food-associated fecal exposures due to urban wastewater irrigation, open drains, and floodwater [26–33].

Site-specific associations between the sanitation ladder and MSD suggest a need for assessment beyond the ladder levels to evaluate sanitation-associated risks of MSD. For example, use of unimproved versus at least basic sanitation was associated with lower odds of pediatric MSD in The Gambia, but sub-ladder level analysis indicates the comparison was primarily private pit latrines with slabs versus those without slabs. This small difference has produced no measurable change in diarrhea in randomized-controlled trials in Kenya [34]. In Kenya, the absence of a sanitation facility (221 enrollees, 6%) was associated with lower odds of MSD, but these households may have been more geographically isolated than comparison households, leaving children less exposed to fecal contamination from neighbors. Within VIDA, Kenya had the lowest coverage of private (29% vs 90% in The Gambia and 55% in Mali) and “at least basic” (private and improved facilities: 13% vs 34% and 55%, respectively) sanitation. Poorer quality sanitation in areas of lower coverage may not sufficiently reduce community-level fecal contamination to elicit measurable health impacts even among those with higher-quality facilities [35, 36]. Importantly, the reference group encompassed both basic and safely managed facilities because current methods of measuring and data for safe management are incomplete [4]. Fecal waste from sanitation facilities meeting “improved” or “basic” design criteria may still be unsafely emptied, transported, or directly discharged into the environment without treatment [37], which was not accounted for in this study.

Animals present in the child's living space increase the risk of pathogen exposure and subsequent diarrhea, but certain animals represent important food sources whose nutritional benefits may extend to combatting inflammation, infections, and stunting [38, 39]. Children or caregivers who do not practice safe animal feces management and hygiene, which have not been a traditional focus of WASH efforts [11], may have more exposure to environmental fecal contamination [40], animal-associated enteric pathogens [10, 41], and subsequent diarrhea. This analysis is an early effort to incorporate animals into models assessing WASH risk factors; however, further research should improve resolution of human-animal and human-animal feces contact and should model specific animal-associated pathogen risks [11, 41].

Water conditions at sites appeared consistent with, or improved from, the 2007–2011 GEMS. At each site, the most prevalent drinking water source was the same, though reported unimproved or surface water use decreased in Mali (12% to <1%) and Kenya (38% to 26%), but not The Gambia (consistently 15%) (unpublished data). JMP country-level trends in unimproved water source use were consistent in Mali (decrease from 21% to 4%), Kenya (more modest decrease: 51% to 40%), and The Gambia (minimal decrease: 21% to 17%) [4]. Compared to the GEMS, associations between unimproved or surface water and MSD appeared slightly larger in pan-site (mOR: 1.5 [95% CI: 1.2, 1.9] vs 1.2 [1.1, 1.3] in GEMS) and The Gambia (mOR: 1.9 [1.5, 2.5] vs 1.3 [1.0, 1.6]), but similar in Kenya (mOR: 1.3 [1.1, 1.6] vs 1.3 [1.1, 1.5]) and Mali (mOR: 0.7 [0.1, 7.8] vs 1.1 [0.9, 1.3]) (unpublished data), although VIDA and GEMS results were not statistically compared. Larger magnitudes of associations may be due to decreased rotavirus infection (not considered to have primarily waterborne exposure pathways) via vaccine-induced protection and a therefore higher burden of MSD attributable to other WASH-associated pathogens [42].

Sanitation conditions were largely unchanged from the GEMS in The Gambia and Mali, although Kenyan households without sanitation facilities decreased (29% to 6%) [17] more than in 2000–2015 JMP data (20% to 15%) [4]. In Mali, sanitation shared with 1–2 households, compared with private facilities, was associated with lower odds of MSD (mOR: 0.8 [95% CI: .7, 1.0]), in contrast to the GEMS (1.2 [1.0, 1.5] [17]). In Kenya, children in households sharing a facility with ≥3 households had larger odds of MSD than in the GEMS (mOR: 2.2 [1.8, 2.7] vs 1.6 [1.3, 2.1]). Sharing a facility with 1–2 households showed no association, unlike in the GEMS (mOR: 1.4 [1.1, 1.8]) [17]. Shared sanitation was not associated with MSD in The Gambia in either study [17].

Analyses of animal risk factors for MSD in GEMS were limited to a subset of 73 Kenyan case-control pairs, making qualitative comparisons between studies difficult. Frequencies of reporting animals were similar in the GEMS and VIDA [43].

Besides slightly different site locations in Kenya and The Gambia, data collection between the VIDA study and the GEMS [17] varied. The VIDA study did not collect household-level data on water treatment, length of water storage, presence of handwashing stations, and other variables to help contextualize WASH practices. Sanitation facilities were not observed, but respondent-reported, which could have yielded reporting bias in cases enrolled at clinics, not at home [44, 45]. Through verification of latrines in 2019, we observed 33/100 most recent VIDA Kenya case enrollees had a different sanitation facility than reported in their initial enrollment [unpublished data], although we are unable to identify whether these discrepancies were due to changes in household sanitation after enrollment, or inaccurate reporting.

In summary, we observed lower levels of survey-reported access to and availability of safe drinking water sources were strongly associated with MSD: almost all levels of the JMP drinking water ladder below “safely managed” were associated with ≥40% increased odds of MSD in pan-site and rural site (Kenya and The Gambia) analyses. Survey-reported sanitation ladder and animal associations with MSD were more context-dependent. Although improved understanding of how human and animal feces management integrate is still needed [46], these results support calls to deliver more transformational, rather than incremental, improvements in water and sanitation to reduce severed diarrhea in children [47].

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

David M Berendes, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Kirsten Fagerli, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Sunkyung Kim, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Dilruba Nasrin, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Medicine, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Helen Powell, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Irene N Kasumba, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Medicine, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Sharon M Tennant, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Medicine, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Anna Roose, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

M Jahangir Hossain, Medical Research Council Unit, The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Banjul, The Gambia.

Joquina Chiquita M Jones, Medical Research Council Unit, The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Banjul, The Gambia.

Syed M A Zaman, Medical Research Council Unit, The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Banjul, The Gambia.

Richard Omore, Center for Global Health Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kisumu, Kenya.

John B Ochieng, Center for Global Health Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kisumu, Kenya.

Jennifer R Verani, Division of Global Health Protection, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nairobi, Kenya.

Marc-Alain Widdowson, Division of Global Health Protection, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nairobi, Kenya.

Samba O Sow, Centre pour le Développement des Vaccins du Mali (CVD-Mali), Bamako, Mali.

Sanogo Doh, Centre pour le Développement des Vaccins du Mali (CVD-Mali), Bamako, Mali.

Ciara E Sugerman, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Eric D Mintz, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Karen L Kotloff, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors express their deep gratitude to the families who participated in these studies, the clinical and field staff for their exceptional hard work and dedication, and to the physicians, administration, and health officials at every site who generously provided facilities and support for the conduct of the study. They are grateful to Catherine Johnson, Chris Focht, and Nora Watson at the Emmes Company, LLC, for expert data management and reporting. Special thanks go to Carl Kirkwood, Duncan Steele, and Anita Zaidi at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for helpful oversight, Kathy Neuzil for thoughtful suggestions, and to the following members of our International Scientific Advisory Committee for providing insightful comments and guidance: Janet Wittes (Chair), George Armah, John Clemens, Christopher Duggan, Stephane Helleringer, Ali Mokdad, James Nataro, and Halvor Sommerfelt. This supplement is sponsored by the Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health (CVD) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore (UMB).

Supplement sponsorship. This supplement was sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This study is based on research funded in part by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1111236/OPP1116751).

Disclaimer. The funding organizations had no role in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Kenya Medical Research Institute, University of Maryland, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nor any of the collaborating partners in this project.

Financial support. This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grants OPP1111236 and OPP1116751.

References

- 1. Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396:1204–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) . GBD Results Tool. 2022. Available at: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. Accessed 25 May 2021.

- 3. Troeger C, Blacker BF, Khalil IA, et al. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:1211–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) . Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene: 2017 update and SDG baselines. Geneva, Switzerland. 2017. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/JMP-2017-report-launch-version_0.pdf. Accessed 1 December 2022

- 5. United Nations General Assembly . Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html.

- 6. Aliabadi N, Antoni S, Mwenda JM, et al. Global impact of rotavirus vaccine introduction on rotavirus hospitalisations among children under 5 years of age, 2008–16: findings from the Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Lancet Glob Heal 2019; 7:e893–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Longini IM, Nizam A, Ali M, Yunus M, Shenvi N, Clemens JD. Controlling endemic cholera with oral vaccines. PLoS Med 2007; 4:1776–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Date KA, Bentsi-Enchill A, Marks F, Fox K. Typhoid fever vaccination strategies. Vaccine 2015; 33:C55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barber RM, Fullman N, Sorensen RJD, et al. Healthcare access and quality index based on mortality from causes amenable to personal health care in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a novel analysis from the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2017; 390:231–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ngure FM, Humphrey JH, Mbuya MNN, et al. Formative research on hygiene behaviors and geophagy among infants and young children and implications of exposure to fecal bacteria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 89:709–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prendergast AJ, Gharpure R, Mor S, et al. Putting the “A” into WaSH: a call for integrated management of water, animals, sanitation, and hygiene. Lancet Planet Heal 2019; 3:e336–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Muhsen K. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS): impetus, rationale, and genesis. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kotloff KL, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, et al. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) of diarrheal disease in infants and young children in developing countries: epidemiologic and clinical methods of the case/control study. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:S232–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 2013; 382:209–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Powell H, Liang Y, Roose A, et al. A description of the statistical methods for the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) study. Clin Infect Dis. 2023; 76(Suppl 1):S5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2015; Available at: https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 1 December 2022

- 17. Baker KK, O’Reilly CE, Levine MM, et al. Sanitation and hygiene-specific risk factors for moderate-to-severe diarrhea in young children in the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, 2007–2011: case-control study. PLoS Med 2016; 13:e1002010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nasrin D, Liang Y, Powell H, et al. Moderate-to-severe diarrhea and stunting among children younger than 5 years: findings from the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) study. Clin Infect Dis. 2023; 76(Suppl 1):S41–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berendes DM, Omore R, Prentice-Mott G, et al. Exploring survey-based water, sanitation, and animal associations with enteric pathogen carriage: comparing results in a cohort of cases with moderate-to-severe diarrhea to those in controls in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) study, 2015–2018. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76(Suppl 1):S140–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pickering AJ, Davis J. Freshwater availability and water fetching distance affect child health in sub-Saharan Africa. Environ Sci Technol 2012; 46:2391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nygren BL, O’Reilly CE, Rajasingham A, et al. The relationship between distance to water source and moderate-to-severe diarrhea in the global enterics multi-center study in Kenya, 2008–2011. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016; 94:1143–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kumpel E, Nelson KL. Comparing microbial water quality in an intermittent and continuous piped water supply. Water Res 2013; 47:5176–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bivins AW, Sumner T, Kumpel E, et al. Estimating infection risks and the global burden of diarrheal disease attributable to intermittent water supply using QMRA. Environ Sci Technol 2017; 51:7542–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ercumen A, Arnold BF, Kumpel E, et al. Upgrading a piped water supply from intermittent to continuous delivery and association with waterborne illness: a matched cohort study in Urban India. PLoS Med 2015; 12:e1001892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baker KK, Sow SO, Kotloff KL, et al. Quality of piped and stored water in households with children under five years of age enrolled in the Mali site of the Global Enteric Multi-Center Study (GEMS). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 89:214–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang Y, Moe CL, Null C, et al. Multipathway quantitative assessment of exposure to fecal contamination for young children in low-income urban environments in Accra, Ghana : the SaniPath analytical approach. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 97:1009–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robb K, Null C, Teunis P, Yakubu H, Armah G, Moe CL. Assessment of fecal exposure pathways in low-income urban neighborhoods in Accra, Ghana : rationale, design, methods, and key findings of the SaniPath study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 97:1020–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Antwi-Agyei P, Cairncross S, Peasey A, et al. A farm to fork risk assessment for the use of wastewater in agriculture in Accra, Ghana. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0142346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Berendes DM, Kirby AE, Clennon JA, et al. Urban sanitation coverage and environmental fecal contamination: links between the household and public environments of Accra, Ghana. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0199304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Katukiza AY, Ronteltap M, van der Steen P, Foppen JW, Lens PNL. Quantification of microbial risks to human health caused by waterborne viruses and bacteria in an urban slum. J Appl Microbiol 2014; 116:447–63. Available at: https://sfamjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jam.12368. Accessed 12 November 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Labite H, Lunani I, van der Steen P, Vairavamoorthy K, Drechsel P, Lens P. Quantitative microbial risk analysis to evaluate health effects of interventions in the urban water system of Accra, Ghana. J Water Health 2010; 8:417–30. Available at:https://iwaponline.com/jwh/article-abstract/8/3/417/18121. Accessed 12 November 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gretsch SR, Ampofo JA, Baker KK, et al. Quantification of exposure to fecal contamination in open drains in four neighborhoods in Accra, Ghana. J Water Health 2016; 14: 255–66. http://jwh.iwaponline.com/content/early/2015/11/11/wh.2015.138.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Berendes DM, Leon JS, Kirby AE, et al. Associations between open drain flooding and pediatric enteric infections in the MAL-ED cohort in a low-income, urban neighborhood in Vellore, India. BMC Public Health 2019; 19:926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Null C, Stewart CP, Pickering AJ, et al. Effects of water quality, sanitation, handwashing, and nutritional interventions on diarrhoea and child growth in rural Kenya: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Heal 2018; 6:e316–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berendes D, Kirby A, Clennon JA, et al. The influence of household- and community-level sanitation and fecal sludge management on urban fecal contamination in households and drains and enteric infection in children. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 96:1404–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fuller JA, Eisenberg JNS. Herd protection from drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016; 95:1201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baum R, Luh J, Bartram J. Sanitation: a global estimate of sewerage connections without treatment and the resulting impact on MDG progress. Environ Sci Technol 2013; 47:1994–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Millward DJ. Nutrition, infection and stunting: the roles of deficiencies of individual nutrients and foods, and of inflammation, as determinants of reduced linear growth of children. Nutr Res Rev 2017; 30:50–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mosites EM, Rabinowitz PM, Thumbi SM, et al. The relationship between livestock ownership and child stunting in three countries in Eastern Africa using national survey data. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0136686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ercumen A, Pickering AJ, Kwong LH, et al. Animal feces contribute to domestic fecal contamination: evidence from E. coli measured in water, hands, food, flies, and soil in Bangladesh. Environ Sci Technol 2017; 51:8725–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Penakalapati G, Swarthout J, Delahoy MJ, et al. Exposure to animal feces and human health: a systematic review and proposed research priorities. Environ Sci Technol 2017; 51:11537–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kotloff KL. VIDA MAIN PAPER. Clin Infect Dis. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Conan A, Reilly CEO, Ogola E, et al. Animal-related factors associated with moderate-to-severe diarrhea in children younger than five years in western Kenya : a matched case-control study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11:e0005795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Van de Mortel T. Faking it: social desirability response bias in self-report research. Aust J Adv Nurs 2008; 25:40–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bartram J, Brocklehurst C, Fisher MB, et al. Global monitoring of water supply and sanitation: history, methods and future challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014; 11:8137–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Berendes DM, Yang PJ, Lai A, Hu D, Brown J. Estimation of global recoverable human and animal faecal biomass. Nat Sustain 2018; 1:679–85. Available at:http://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-018-0167-0. Accessed 13 November 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pickering AJ, Null C, Winch PJ, et al. The WASH benefits and SHINE trials: interpretation of WASH intervention effects on linear growth and diarrhoea. Lancet Glob Heal 2019; 7:e1139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.