Abstract

Background

The magnitude of pediatric enteric pathogen exposures in low-income settings necessitates substantive water and sanitation interventions, including animal feces management. We assessed associations between pediatric enteric pathogen detection and survey-based water, sanitation, and animal characteristics within the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa case-control study.

Methods

In The Gambia, Kenya, and Mali, we assessed enteric pathogens in stool of children aged <5 years with moderate-to-severe diarrhea and their matched controls (diarrhea-free in prior 7 days) via the TaqMan Array Card and surveyed caregivers about household drinking water and sanitation conditions and animals living in the compound. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using modified Poisson regression models, stratified for cases and controls and adjusted for age, sex, site, and demographics.

Results

Bacterial (cases, 93%; controls, 72%), viral (63%, 56%), and protozoal (50%, 38%) pathogens were commonly detected (cycle threshold <35) in the 4840 cases and 6213 controls. In cases, unimproved sanitation (RR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.12–2.17), as well as cows (RR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.16–2.24) and sheep (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.11–1.96) living in the compound, were associated with Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli. In controls, fowl (RR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.15–1.47) were associated with Campylobacter spp. In controls, surface water sources were associated with Cryptosporidium spp., Shigella spp., heat-stable toxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli, and Giardia spp.

Conclusions

Findings underscore the importance of enteric pathogen exposure risks from animals alongside more broadly recognized water and sanitation risk factors in children.

Keywords: water, sanitation, diarrhea, animals, enteric pathogens

We assessed survey-based water, sanitation, and animal factors associated with enteric pathogens in cases of moderate to severe diarrhea and controls. Animals, cows and sheep (cases) and fowl (controls), were associated with bacterial carriage; surface water was associated with bacteria and protozoa in controls.

Despite incidence among children aged <5 years declining 10% from 2005 to 2015, diarrhea continued to cause an estimated 500 000 deaths globally in 2020 [1–3].

Beyond diarrhea, subclinical infection or carriage of enteric pathogens in children in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is common. A birth cohort study in 7 LMICs [4], as well as cross-sectional assessments in Mozambique [5] and Zimbabwe [6], found that the majority of nondiarrheal stools had enteric pathogens detected, generally by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), alongside concurrently low relative diarrheal prevalence. These subclinical infections or pathogen carriage may contribute to stunting and other longer-term health outcomes [7] but also suggest that the levels of exposure to enteric pathogens and therefore the role of environmental barriers to exposure, such as water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), are far larger than suggested by diarrheal rates alone.

Despite the utility of enteric pathogen carriage as an outcome itself [8–10], assessments of WASH risk factors have focused on pediatric diarrhea [3, 11]. Analysis of environmental risk factors and enteric pathogen exposure may yield insights into the relative importance of different pathways and sources in fecally contaminated environments [12], including animals [13].

We used data from the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) case-control study to examine water, sanitation, and animal exposure and enteric pathogen detection across study sites in The Gambia, Kenya, and Mali. We compared TaqMan Array Card–based enteric pathogen detection with survey-based assessment of levels of the water and sanitation ladders (established by the Joint Monitoring Program (JMP) [14]) and the presence of animals in the compound separately for cases of moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD) and controls. Parallel examination of risk factors between cases and controls can highlight which are important for pathogens that may cause populations to seek care for MSD and which represent background exposure or transmission among populations without recent diarrhea but potentially with intermittent carriage and/or symptoms that may affect longer-term developmental outcomes [15].

METHODS

Study Sites

Three study sites in sub-Saharan Africa that participated in the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) and introduced rotavirus vaccine before 2015 were selected for the VIDA study [16–19].

Study Design

VIDA study methods were similar to those described previously for GEMS [17] and GEMS 1A [20] and have been described elsewhere [19, 21]. Briefly, the VIDA study was a matched case-control study. Cases aged 0–59 months residing in each study site's demographic surveillance system (DSS) and seeking care for MSD at sentinel health centers serving the site's DSS population were screened for diarrhea, defined as ≥3 abnormally loose stools within a 24-hour period. Eligible episodes had acute onset within the past 7 days after ≥7 diarrhea-free days and met criteria for MSD defined as at least 1 of the following: sunken eyes, loss of skin turgor, intravenous rehydration administered or prescribed, visible blood in stool, or hospitalization. Within 14 days of presentation of each case, 1–3 control children without MSD were randomly selected from the DSS database, matched to the case by age group (0–11, 12–23, and 24–59 months), sex, and neighborhood, and were free of diarrhea for the 7 days prior to enrollment. This study was approved by the ethical review committees at the University of Maryland, Baltimore (HP-00062472), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (reliance agreement 6729), The Gambia Government/Medical Research Council/Gambia at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (1409), the Comité d'Ethique de la Faculté de Médecine, de Pharmacie, et d'Odonto-Stomatologie, Bamako, Mali (no number), and the Kenya Medical Research Institute Scientific & Ethics Review Unit in Siaya County, Kenya (SSE 2996). Informed, written consent was obtained from all participants prior to initiation of study procedures [19].

Data Collection

At enrollment (at the clinic for cases, at home for controls), data on household demographics, assets, caregiver's education, animals living in the compound, and water and sanitation access (JMP water and sanitation service ladders [14]; definitions in the Supplementary Material) were collected from the caregiver by survey. Pathogens were detected in cases and their first matched control using a qPCR panel [22] at enrollment. A list of pathogens assessed can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Notably, the pan-Giardia spp. probe was used in a subset of enrollments by site, 61% in The Gambia, 84% in Kenya, and 53% in Mali, due to logistical limitations. Amplifications for enteric pathogens were coded as a detection for cycle threshold (Ct) values <35. Additionally, a cut point of Ct <30 was used for sensitivity analysis to determine whether associations between risk factors and specific enteric pathogens were robust to a more specific choice of cut point and ensure that associations were not being driven by associations with very low levels of given pathogens.

Analysis

Water, sanitation, and animal risk factors for pathogen detection were explored by applying modified Poisson regression (generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors), using geepack in R version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria [23, 24]). Separate models were run for cases and controls. Reference groups were safely managed water (water ladder), at least basic sanitation (sanitation ladder), and the absence of animals. The presence/absence of animals in the child's compound was limited to models for enteric bacteria and for protozoa reported to be transmitted by animal feces (Campylobacter coli or Campylobacter jejuni, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Salmonella spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia spp. [13, 25]). All models were adjusted for a priori confounders (fuel source, household assets, primary caregiver's education), consistent with previous VIDA environmental risk factor analyses [26], and for age group, sex, and site (matching variables for control selection in the VIDA study [19]). Models for rotavirus were also adjusted for rotavirus vaccine doses received. Interactions between the water ladder, sanitation ladder, or animals and site were assessed via analysis of variance. When significant (P < .05), site-specific variable estimates were presented.

RESULTS

Prevalence of Survey-Based Water, Sanitation, and Animal Risk Factors in the VIDA Study

Among 4840 cases and 6213 controls, most reported using drinking water sources that met survey-based criteria for safely managed water (69% of cases, 75% of controls), especially in The Gambia and Mali (Table 1). In Kenya, many used surface water sources (>20% of cases and controls). Reported sanitation varied: 99% of case and control households in Mali reported at least basic or limited sanitation; those in The Gambia reported at least basic (40% of cases, 29% of controls) or unimproved (54% of cases, 67% of controls) sanitation; and most in Kenya reported either limited (33% of cases, 29% of controls) or unimproved (51% of cases, 50% of controls) sanitation. Animals were present in >99% of households. Rodents, fowl, goats, and sheep were most common in The Gambia; fowl, cats, cows, and dogs were most common in Kenya; and rodents, fowl, and sheep were most common in Mali, the only urban site where other animals were virtually absent.

Table 1.

Water, Sanitation, and Animals Among Enrollees in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa Study: Overall and by Site

| Pan-site | The Gambia | Kenya | Mali | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Cases (%) | Controls (%) | Cases (%) | Controls (%) | Cases (%) | Controls (%) | Cases (%) | Controls (%) |

| Water ladder | ||||||||

| ȃSafely manageda | 3353 (69) | 4670 (75) | 1206 (72) | 1754 (82) | 724 (47) | 1161 (55) | 1423 (88) | 1755 (89) |

| ȃBasicb | 234 (4.8) | 250 (4.0) | 42 (2.5) | 33 (1.5) | 174 (11) | 198 (9.5) | 18 (1.1) | 19 (0.96) |

| ȃLimitedc | 485 (10) | 499 (8.0) | 110 (6.6) | 59 (2.8) | 209 (13) | 236 (11) | 166 (10) | 204 (10) |

| ȃUnimprovedd | 340 (7.0) | 359 (5.8) | 306 (18) | 281 (13) | 33 (2.1) | 76 (3.6) | 1 (0.06) | 2 (0.1) |

| ȃSurface watere | 428 (8.8) | 434 (7.0) | 14 (0.83) | 10 (0.46) | 414 (27) | 424 (20) | 0 | 0 |

| Sanitation ladder | ||||||||

| ȃAt least basicf | 1738 (36) | 1985 (32) | 674 (40) | 611 (29) | 183 (12) | 286 (14) | 881 (55) | 1087 (55) |

| ȃLimitedg | 1299 (27) | 1535 (25) | 68 (4.1) | 70 (3.3) | 520 (33) | 601 (29) | 711 (44) | 864 (44) |

| ȃUnimprovedh | 1717 (35) | 2500 (40) | 907 (54) | 1434 (67) | 795 (51) | 1040 (50) | 16 (1.0) | 29 (1.5) |

| ȃOpen defecationi | 86 (1.8) | 193 (3.1) | 30 (1.8) | 26 (1.2) | 56 (3.6) | 166 (7.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Animals living in the compound | ||||||||

| ȃNo animal | 34 (0.70) | 33 (0.53) | 2 (0.12) | 18 (0.84) | 26 (1.7) | 11 (0.52) | 6 (0.37) | 4 (0.20) |

| ȃCats | 1826 (38) | 2279 (37) | 684 (41) | 674 (32) | 1079 (69) | 1514 (72) | 63 (3.9) | 91 (4.6) |

| ȃCows | 1784 (37) | 2188 (37) | 767 (46) | 673 (31) | 1000 (64) | 1499 (72) | 17 (1.1) | 16 (0.81) |

| ȃDogs | 1546 (32) | 2044 (33) | 518 (31) | 628 (29) | 971 (62) | 1348 (64) | 57 (3.5) | 68 (3.4) |

| ȃFowl | 3370 (70) | 4523 (73) | 1417 (84) | 1724 (81) | 1400 (90) | 1970 (94) | 554 (34) | 831 (42) |

| ȃGoats | 1997 (41) | 2519 (41) | 1276 (76) | 1551 (73) | 700 (45) | 943 (45) | 22 (1.4) | 26 (1.3) |

| ȃPigs | 202 (4.2) | 282 (4.2) | 1 (0.06) | 1 (0.05) | 200 (13) | 280 (13) | 1 (0.06) | 1 (0.05) |

| ȃRodents | 3772 (78) | 4912 (79) | 1548 (92) | 1997 (93) | 659 (42) | 969 (46) | 1565 (97) | 1947 (98) |

| ȃSheep | 1996 (41) | 2599 (42) | 1156 (69) | 1420 (66) | 500 (32) | 771 (37) | 340 (21) | 409 (21) |

| ȃOthersj | 9 (0.19) | 13 (0.21) | 2 (0.12) | 3 (0.14) | 3 (0.19) | 6 (0.29) | 4 (0.25) | 4 (0.20) |

Water for drinking from an improved source (piped water, boreholes or tube wells, protected dug wells, protected springs, rainwater, and packaged or delivered water) that is located onsite, available when needed, and free of fecal and chemical contamination [14].

Water for drinking from an improved source where collection time is ≤30 minutes round trip, inclusive of queueing [14].

Water for drinking from an improved source where collection time is >30 minutes round trip, inclusive of queueing [14].

Water for drinking collected from an unprotected spring or unprotected dug well [14].

Water for drinking collected from a river, dam, lake, pond, stream, canal, or irrigation ditch [14].

“At least basic” encompasses the highest 2 levels of the sanitation ladder: safely managed (use of improved sanitation facilities, including flush or pour flush toilets to piped sewers, septic tanks, or pit latrines; ventilated improved pit latrines; composting toilets; and pit latrines with slabs that are not shared with other households and where excreta are safely disposed of onsite/in the system or transported and treated offsite) and basic (use of improved sanitation facilities that are not shared with other households but whose safe disposal or treatment is unknown) [14].

Use of sanitation facilities that are improved but shared between ≥2 households [14].

Use of pit latrines without a slab or platform, hanging latrines, or bucket latrines [14].

Disposal of human feces in open spaces or bodies of water or with solid waste (ie, not into sanitation facilities) [14].

Includes primarily rabbits, turtles, and tortoises.

Pathogen Detection in Stool

Bacteria were the most common pathogens detected (91% of cases, 71% of controls), followed by protozoa (50%, 37%) and viruses (41%, 24%; Supplementary Table 1). The most commonly detected pathogens were enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC: 60% in cases, 65% in controls), C. coli/jejuni (32%, 28%), and Shigella (34%, 23%) among bacteria; adenovirus 40/41 (12% in both cases and controls) and GII norovirus (12%, 11%) among viruses; and Giardia spp. (45%, 48%) and Cryptosporidium spp. (23%, 18%) among protozoa. Generally, cases had more bacterial, protozoal, and viral detections than controls (Supplementary Figure 1).

Case-Only Analyses

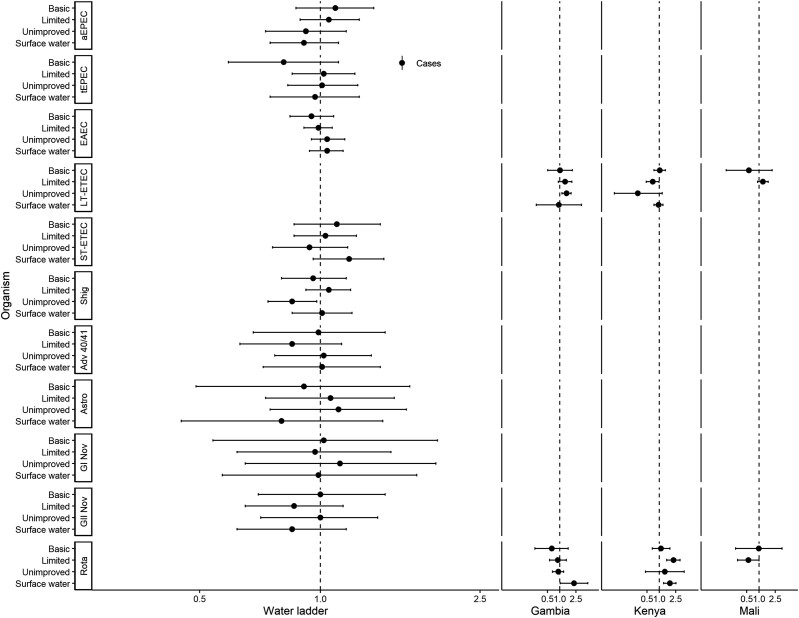

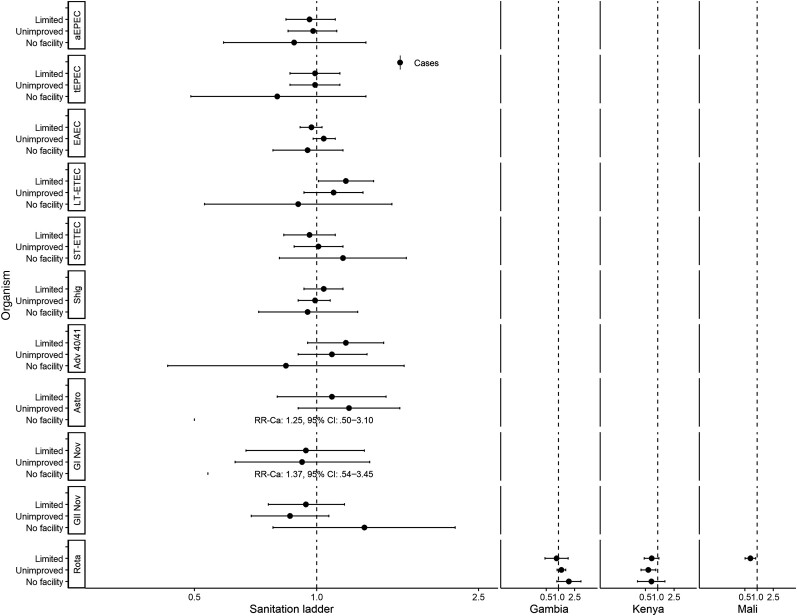

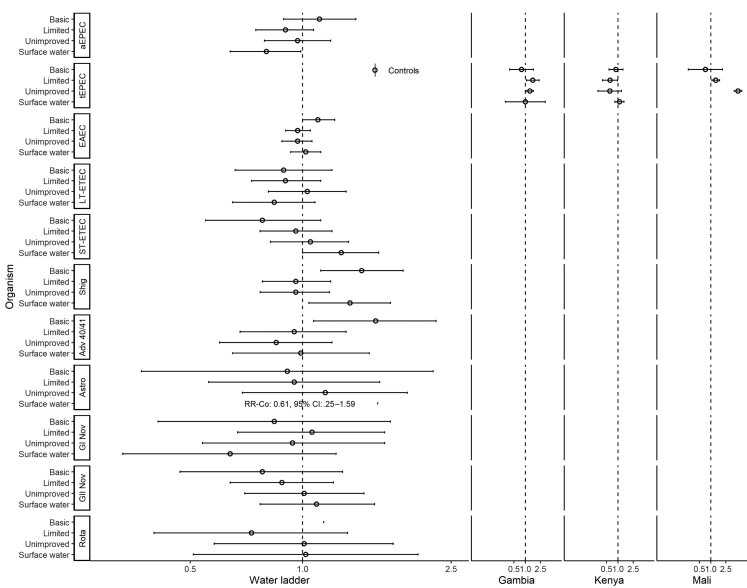

Figures 1 and 2 show associations with non-animal–associated pathogens. Reporting unimproved water was associated with a lower risk of detecting Shigella spp. (adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI], .74–.98; Figure 1). There were significant interactions between water ladder and site in the detection of heat-labile enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli (LT-ETEC) and rotavirus. In The Gambia, reporting unimproved water was associated with a higher risk of LT-ETEC (aRRGambia, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.13–1.89); however, in Kenya, limited water was associated with a lower risk (aRRKenya, 0.69; 95% CI, .48–.99; no associations in Mali). Reporting limited water was associated with a higher risk of rotavirus in Kenya (aRRKenya, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.52–3.20). Reporting surface water was associated with a higher risk of rotavirus in The Gambia (aRRGambia, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.03–4.83) and Kenya (aRRKenya, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.27–2.54); no associations were observed in Mali. Reporting limited sanitation was associated with detection of LT-ETEC (aRR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.01–1.38; Figure 2). There was significant interaction between sanitation and site for rotavirus. In Kenya, reporting unimproved sanitation was associated with lower risk of detection (aRRKenya, 0.59; 95% CI, .39–.89); in Mali, reporting limited sanitation was associated with lower risk of detection (aRRMali, 0.69; 95% CI, .51–.93); and no associations were observed in The Gambia.

Figure 1.

Adjusted associations (risk ratios [RR] and 95% confidence intervals [CI]) between water and sanitation ladder levels and pathogen exposure among cases in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: water ladder. Reference group for water ladder: safely managed. Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders (see Figure 2 for sanitation ladder estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Interactions were assessed between water ladder levels and site via analysis of variance; when significant, site-specific results are presented for that pathogen/variable combination. Abbreviations: Adv 40/41, adenovirus 40/41; aEPEC, atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli; Astro, astrovirus; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; GI Nov, GI norovirus; GII Nov, GII norovirus; LT-ETEC, heat-labile enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli; Rota, rotavirus; Shig, Shigella spp. or enteroinvasive E. coli probe; ST-ETEC, heat-stable enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli; tEPEC, typical enteropathogenic E. coli.

Figure 2.

Adjusted associations (RRs and 95% CIs) between water and sanitation ladder levels and pathogen exposure among cases in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: sanitation ladder. Reference group for sanitation ladder: at least basic (combined safely managed and basic). Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders (see Figure 1 for water ladder estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Interactions were assessed between water ladder levels and site via analysis of variance; when significant, site-specific results are presented for that pathogen/variable combination. Abbreviations: Adv 40/41, adenovirus 40/41; aEPEC, atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli; Astro, astrovirus; CI, confidence interval; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; GI Nov, GI norovirus; GII Nov, GII norovirus; LT-ETEC, heat-labile enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli; Rota, rotavirus; RR, risk ratio; Shig, Shigella spp. or enteroinvasive E. coli probe; ST-ETEC, heat-stable enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli; tEPEC, typical enteropathogenic E. coli.

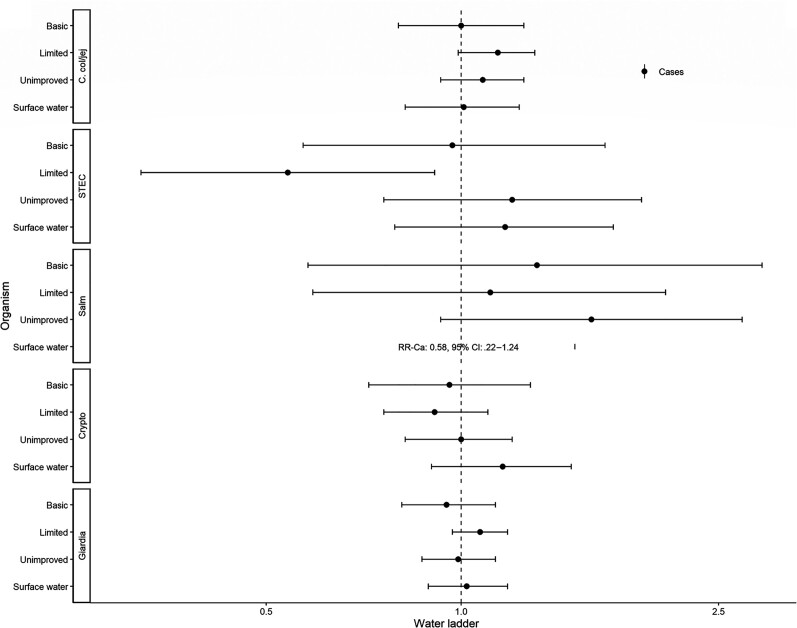

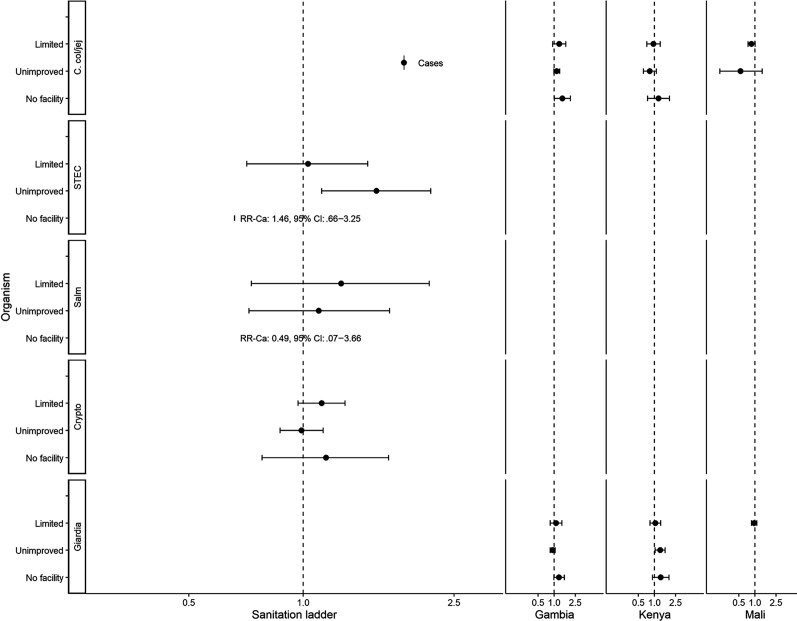

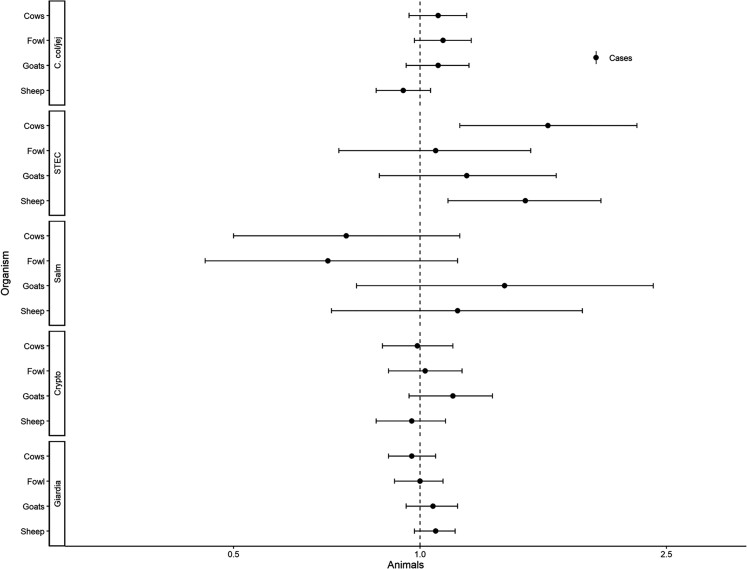

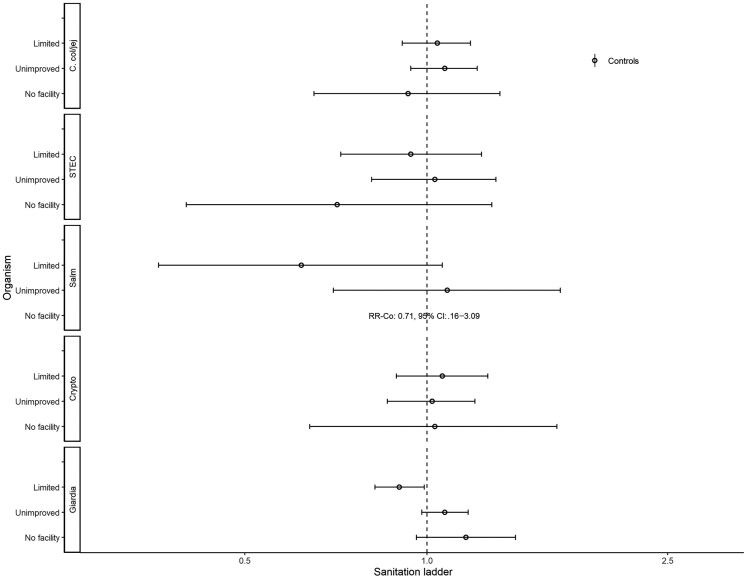

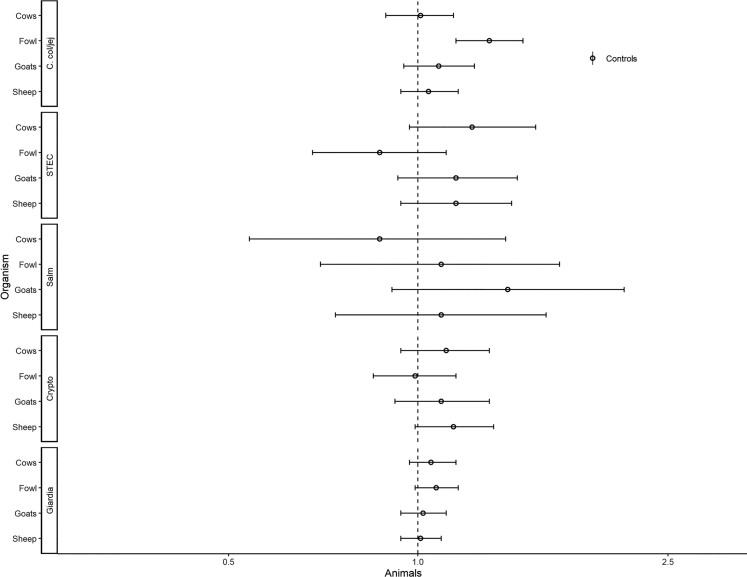

Figures 3–5 show assessments of animal-associated pathogens. Reporting limited water was associated with lower detection of STEC (aRR, 0.54; 95% CI, .32–.91; Figure 3). Reporting unimproved sanitation was associated with the detection of STEC (aRR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.12–2.17; Figure 4). Reporting no sanitation facility was associated with C. coli/jejuni in The Gambia (aRRGambia, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.01–2.04), with no associations at other sites. Reporting unimproved sanitation was associated with Giardia spp. in Kenya (aRRKenya, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.03–1.58), with no associations at other sites. Cows (aRR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.16–2.24) and sheep (aRR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.11–1.96) were associated with detection of STEC (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Adjusted associations (RRs and 95% CIs) between water and sanitation ladder levels, animals, and pathogen exposure among cases in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: water ladder. Reference group for water ladder: safely managed. Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders and animal risk factors (see Figure 4 for sanitation ladder estimates, Figure 5 for animal estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Among enrollees who had a sample tested for Giardia spp.: pan site: N = 7278 of 11 053, 66%; The Gambia site: N = 2311 of 3816, 61%; Kenya site: N = 3070 of 3649, 84%; Mali site: N = 1897 of 3588, 53%. Abbreviations: Ca, C. col/jej, Campylobacter coli or jejuni; CI, confidence interval; Crypto, Cryptosporidium spp.; Giardia, Giardia spp.; RR, risk ratio; Salm, Salmonella spp.; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

Figure 4.

Adjusted associations (RRs and 95% CIs) between water and sanitation ladder levels, animals, and pathogen exposure among cases in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: sanitation ladder. Reference group for sanitation ladder: at least basic (combined safely managed and basic). Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders and animal risk factors (see Figure 3 for water ladder estimates, Figure 5 for animal estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Among enrollees who had a sample tested for Giardia spp.: pan site: N = 7278 of 11 053, 66%; The Gambia site: N = 2311 of 3816, 61%; Kenya site: N = 3070 of 3649, 84%; Mali site: N = 1897 of 3588, 53%. Interactions were assessed between water ladder levels and site via analysis of variance; when significant, site-specific results are presented for that pathogen/variable combination. Abbreviations: Ca, C. col/jej, Campylobacter coli or jejuni; CI, confidence interval; Crypto, Cryptosporidium spp.; Giardia, Giardia spp.; RR, risk ratio; Salm, Salmonella spp.; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

Figure 5.

Adjusted associations (risk ratios [RRs] and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) between water and sanitation ladder levels, animals, and pathogen exposure among cases in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: animals. Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders and animal risk factors (see Figure 3 for water ladder estimates, Figure 4 for sanitation ladder estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Among enrollees who had a sample tested for Giardia spp.: pan site: N = 7278 of 11 053, 66%; The Gambia site: N = 2311 of 3816, 61%; Kenya site: N = 3070 of 3649, 84%; Mali site: N = 1897 of 3588, 53%. Abbreviations: Ca, C. col/jej, Campylobacter coli or jejuni; Crypto, Cryptosporidium spp.; Giardia, Giardia spp.; Salm, Salmonella spp.; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

Control-Only Analyses

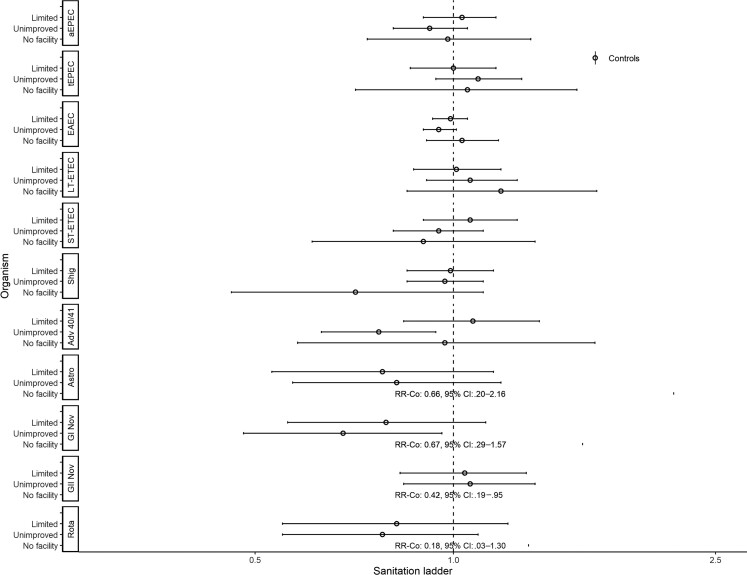

Figures 6 and 7 show assessments of non-animal–associated pathogens. Reporting basic water was associated with EAEC (aRR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.00–1.22), Shigella spp. (aRR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.12–1.86), and adenovirus 40/41 (aRR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.07–2.28; Figure 6). Reporting surface water was associated with lower risk of detecting atypical enteropathogenic E. coli (aEPEC; aRR, 0.80; 95% CI, .64–.99) but higher risk of heat-stable enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli (ST-ETEC; aRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.00–1.60) and Shigella spp. (aRR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.04–1.72). There was significant interaction between water ladder levels and site for typical enteropathogenic E. coli detection. In The Gambia and Mali, reporting limited (aRRGambia, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.08– 2.28; aRRMali, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.07–1.70) or unimproved (aRRGambia, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.05–1.64; aRRMali, 5.17; 95% CI, 4.11–6.50) water was associated with higher risk of detection; however, in Kenya, reporting limited water was associated with lower risk of detection (aRRKenya, 0.62; 95% CI, .39–.97). Reporting unimproved sanitation was associated with lower risk of detecting adenovirus 40/41 (aRR, 0.77; 95% CI, .63–.94), and GI norovirus (aRR, 0.68; 95% CI, .48–.96; Figure 7). Reporting no facility was associated with lower risk of detecting GII norovirus (aRR, 0.42; 95% CI, .19–.95).

Figure 6.

Adjusted associations (RRs and 95% CIs) between water and sanitation ladder levels and pathogen exposure among controls in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: water ladder. Reference group for water ladder: safely managed. Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders (see Figure 7 for sanitation ladder estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Interactions were assessed between water ladder levels and site via analysis of variance; when significant, site-specific results are presented for that pathogen/variable combination. Abbreviations: Adv 40/41, adenovirus 40/41; aEPEC, atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli; Astro, astrovirus; Co, CI, confidence interval; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; GI Nov, GI norovirus; GII Nov, GII norovirus; LT-ETEC, heat-labile enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli; Rota, rotavirus; RR, risk ratio; Shig, Shigella spp. or enteroinvasive E. coli probe; ST-ETEC, heat-stable enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli; tEPEC, typical enteropathogenic E. coli.

Figure 7.

Adjusted associations (RRs and 95% CIs) between water and sanitation ladder levels and pathogen exposure among controls in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: sanitation ladder. Reference group for sanitation ladder: at least basic (combined safely managed and basic). Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders (see Figure 6 for water ladder estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Interactions were assessed between water ladder levels and site via analysis of variance; when significant, site-specific results are presented for that pathogen/variable combination. Abbreviations: Adv 40/41, adenovirus 40/41; aEPEC, atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli; Astro, astrovirus; Co, CI, confidence interval; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; GI Nov, GI norovirus; GII Nov, GII norovirus; LT-ETEC, heat-labile enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli; Rota, rotavirus; RR, risk ratio; Shig, Shigella spp. or enteroinvasive E. coli probe; ST-ETEC, heat-stable enterotoxin-producing enterotoxigenic E. coli; tEPEC, typical enteropathogenic E. coli.

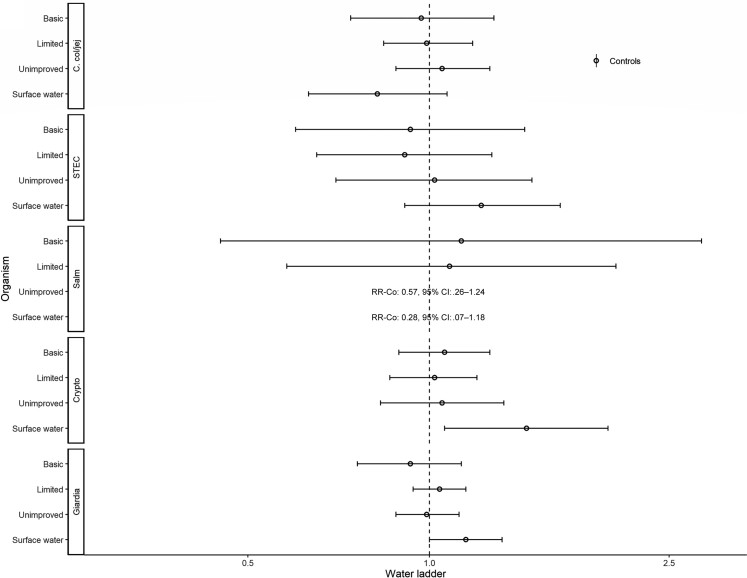

Associations with animal-associated enteric pathogens are presented in Figures 8–10. Reporting surface water was associated with the detection of Cryptosporidium spp. (aRR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.06–1.98) and Giardia spp. (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.00–1.32; Figure 8). Reporting limited sanitation was associated with a lower risk of detecting Giardia spp. (aRR, 0.90; 95% CI, .82–.99; Figure 9). Fowl were associated with C. coli/jejuni (aRR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.15–1.47; Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Adjusted associations (RRs and 95% CIs) between water and sanitation ladder levels, animals, and pathogen exposure among controls in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: water ladder. Reference group for water ladder: safely managed. Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders and animal risk factors (see Figure 9 for sanitation ladder estimates, Figure 10 for animal estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Among enrollees who had a sample tested for Giardia spp.: pan site: N = 7278 of 11 053, 66%; The Gambia site: N = 2311 of 3816, 61%; Kenya site: N = 3070 of 3649, 84%; Mali site: N = 1897 of 3588, 53%. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Co, C. col/jej, Campylobacter coli or jejuni; Crypto, Cryptosporidium spp.; Giardia, Giardia spp.; RR, risk ratio; Salm, Salmonella spp.; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

Figure 9.

Adjusted associations (RRs and 95% CIs) between water and sanitation ladder levels, animals, and pathogen exposure among controls in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: sanitation ladder. Reference group for sanitation ladder: at least basic (combined safely managed and basic). Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders and animal risk factors (see Figure 8 for water ladder estimates, Figure 10 for animal estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Among enrollees who had a sample tested for Giardia spp.: pan site: N = 7278 of 11 053, 66%; The Gambia site: N = 2311 of 3816, 61%; Kenya site: N = 3070 of 3649, 84%; Mali site: N = 1897 of 3588, 53%. Interactions were assessed between water ladder levels and site via analysis of variance; when significant, site-specific results are presented for that pathogen/variable combination. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Co, C. col/jej, Campylobacter coli or jejuni; Crypto, Cryptosporidium spp.; Giardia, Giardia spp.; RR, risk ratio; Salm, Salmonella spp.; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

Figure 10.

Adjusted associations (risk ratios [RRs] and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) between water and sanitation ladder levels, animals, and pathogen exposure among controls in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa study: animals. Each model of a pathogen outcome included water and sanitation ladders and animal risk factors (see Figure 8 for water ladder estimates, Figure 9 for sanitation ladder estimates) and was adjusted for sex, age group, site, caregiver education, fuel source, and household assets. Estimates with RRs or CIs outside the bounds of the graphic are written in text. Among enrollees who had a sample tested for Giardia spp.: pan site: N = 7278 of 11 053, 66%; The Gambia site: N = 2311 of 3816, 61%; Kenya site: N = 3070 of 3649, 84%; Mali site: N = 1897 of 3588, 53%. Abbreviations: C. col/jej, Campylobacter coli or jejuni; Crypto, Cryptosporidium spp.; Giardia, Giardia spp.; Salm, Salmonella spp.; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

For both case and control models, unadjusted estimates are presented in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Sensitivity Analysis

Compared with the Ct = 35 cut point for classifying detection and nondetection of specified enteric pathogens, most aRRs did not change markedly when assessed using a Ct = 30 cut point to assess robustness of the association (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Notable exceptions were associations between surface water and ST-ETEC and Giardia spp. in controls (ST-ETEC: aRR, 1.27; Ct = 35 cut point vs aRR, 0.97; Ct = 30 cut point; Giardia spp. aRRs, 1.15 vs 1.00), and also between limited sanitation and LT-ETEC in cases (aRRs, 1.18 vs 0.95). Marginal associations were strengthened between Campylobacter in cases and exposure to fowl (aRR, 1.09; 95% CI, .98–1.21 vs aRR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.02–1.23), as were those between Campylobacter and goats in both cases (aRR, 1.07; 95% CI, .95–1.20 vs aRR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.00–1.25) and controls (aRR, 1.08; 95% CI, .95–1.23 vs aRR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01–1.28).

DISCUSSION

In our evaluation of survey-based water, sanitation, and animal risk factors for enteric pathogen detection in cases and controls, we observed key animal associations with enteric pathogens, including STEC and Campylobacter spp., and surface water with bacteria, protozoa, and viruses. Water, sanitation, and animal associations differed between cases and controls for many enteric pathogens. Overall, these results support other evidence that although the pediatric microbiome in LMIC settings is complex, the environment, inclusive of WASH and animal exposures, plays an important role [27, 28].

These results, along with those of the Maputo Sanitation [5, 8] and the Sanitation Hygiene Infant Nutrition Efficacy trials [6], are some of the first to examine stool-based markers of enteric pathogen exposure as outcomes in both cases and controls and to assess risks from animals alongside WASH [29]. Identifying risk factors for acquisition of enteric pathogens can inform the design and evaluation of environmental interventions with increased sensitivity of outcome measures over diarrhea or nutritional health in LMIC settings [5, 8, 22, 30, 31]. This approach mirrors hazard-based approaches to systematically reduce enteric exposures in food production systems [32], following an environmental health framework to evaluate associations between the environment and pathogen hazards in stool, independent of downstream disease impacts [8, 10, 33]. This analysis focusing on detection of enteric pathogen carriage in stool is complementary to other analyses assessing similar risk factors but focusing on clinical MSD [26], as this analysis provides greater understanding of the degree to which environmental risk factors for carriage mirror those for clinical diarrhea, and therefore may suggest new avenues of intervention.

Cows, sheep, and unimproved sanitation were associated with STEC detection among MSD cases. STEC colonizes the intestines of cattle and other ruminants globally. Humans are exposed via fecal contamination of agricultural products harvested where animals graze, as well as milk, meat, and other fecally contaminated environments and surfaces [34–37]. Data are limited in defining the clinical importance of STEC in LMIC [38]. In the GEMS and VIDA studies, STEC was uncommon and not associated with MSD [18, 20]. While the specific exposure pathways by which animals contribute to STEC in humans in LMICs remain uncertain [13], unhygienic handling of food from farm to fork as well as manure have been implicated [34, 37, 39, 40], and the persistence of STEC in feces may be consistent with human sanitation-related pathways [14, 37].

Campylobacter coli/jejuni detection was marginally associated with fowl and goats among MSD cases and significantly associated with fowl, goats, and sheep among controls. These observations are supported by recent analyses of Campylobacter in food animals and meat in sub-Saharan Africa [41] and in strong associations between poultry ownership and household environmental contamination [42] and Campylobacter spp. infection in children [43]. Although the Campylobacter-associated pediatric diarrheal disease burden is not well defined, Campylobacter was responsible for 12% of community-based diarrhea in children aged <2 years at MAL-ED sites [31], 6%–12% of MSD among infants seeking healthcare at 6 of 7 GEMS sites [22], and a high global burden of disability-adjusted life-years [3, 13]. Although our data cannot confirm exposure pathways, they may include geophagy [44]; consumption of untreated, contaminated water sources; hand-to-mouth contact; or contaminated food via unhygienic handling practices [45].

Multiscale interventions along the entire value chain may be required to mitigate animal-associated pathogens [46]. To date, household-based interventions, including sequestering children in safe play spaces away from animals, have not interrupted enteric pathogen transmission [47], and corralling of poultry incurs increased costs from construction and maintenance/feed [48].

Among controls, Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp., which are persistent, chlorine-tolerant protozoans with zoonotic sources and low infectious doses [13], were associated with drinking surface water. In GEMS cases, Cryptosporidium spp. infection risk was lower for children reported to drink mainly boiled water and rainwater [49]; however, treatment of drinking water was not recorded in this study. Associations between surface water and chlorine-susceptible organisms (Shigella spp. and ST-ETEC [50]) could reflect drinking or non-drinking–related exposures to unchlorinated water [51].

The differences in risk factors between cases and controls are important and may have several potential explanations. WASH and animal exposure assessment varied slightly between cases (interviewed at the health facility) and controls (interviewed at home where direct observations were possible). A post-study observation of sanitation at the Kenya site noted differences from facilities reported at enrollment [26], suggesting potential for courtesy bias. Second, the time since exposure may be shorter in an MSD case than in a control, meaning controls had more time to accumulate varying potential exposures, complicating risk factor determination. Many enteric bacteria, protozoa, and viruses can be shed for weeks to months after an initial symptomatic infection or with partial host immunity that mitigates diarrheal symptoms but does not eliminate the inciting agent [52]. Third, the degree of symptomatology necessary to be classified as a case may vary with the amount of infectious inoculum at a single exposure, while controls could incur repeated, smaller-dose exposures insufficient to cause acute symptoms. Finally, pathogens that did not cause the symptoms could have been co-detected in cases and thus could be falsely classified with the risk factor associated with the MSD episode.

Exposure to rotavirus from surface water in cases at the rural sites (The Gambia and Kenya), though unexpected, could be from direct or more delayed pathways. Direct environmental exposure could be through fecal discharge into surface water from poorly managed onsite sanitation or open defecation, combined with use of surface water for drinking [53, 54]. Separately, repeated exposure to poorer water and sanitation conditions, yielding repeat enteric infections and environmental enteropathy, could have reduced oral vaccine seroconversion rates and rendered children more susceptible to rotavirus despite vaccination, as suggested recently in Zimbabwe and Peru [55, 56].

Consistent with results assessing MSD in the VIDA study, the mixed associations observed suggest sanitation-associated risk factors are poorly described using the ladder [26]. Inclusion of community-level sanitation coverage and examination of joint effects with drinking water may be informative in additional investigations [57, 58]. Cohort studies, including longitudinal sampling to directly assess impacts of better sanitation conditions from birth on enteric pathogen detections, may also be more appropriate than cross-sectional analyses [12].

This analysis has limitations. Analyzing cases and controls as separate cohorts limits the generalizability of results despite systematic sampling. The exploratory analytic approach and the number of models tested should incur further and more directed hypothesis testing. Further, we did not assess laboratory-based risk factors; the safely managed level of the water ladder was assessed by survey and did not include microbial water quality assessments, an important criterion [14]. Additionally, the sample size was insufficient to evaluate individual risk factors comprising ladder levels, such as water availability. Quantifying animals within the compound and screening them for pathogens may have provided greater detail on exposure risks from aggregate contact. Finally, the evaluation of pathogen detection should be appropriately contextualized given that molecular methods cannot guarantee viable pathogens were present.

These results identify animals as important risk factors for acquisition of enteric pathogens in resource-poor settings while underscoring more well-documented water-related risk factors. Additionally, examination of water and sanitation conditions and stool-based pathogen detection in cases and controls, in contrast to the use of diarrhea as an outcome, can change the sensitivity with which interventions to reduce enteric pathogen transmission are evaluated. Site-specific variability in certain associations with pathogens supports the importance of context-specific approaches to understanding and mitigating environmental enteric pathogen transmission.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

David M Berendes, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Richard Omore, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Center for Global Health Research, Kisumu, Kenya.

Graeme Prentice-Mott, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Kirsten Fagerli, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Sunkyung Kim, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Dilruba Nasrin, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Helen Powell, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Pediatrics, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

M Jahangir Hossain, Medical Research Council Unit, The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; Banjul, The Gambia.

Samba O Sow, Centre pour le Développement des Vaccins du Mali (CVD-Mali), Bamako, Mali.

Sanogo Doh, Centre pour le Développement des Vaccins du Mali (CVD-Mali), Bamako, Mali.

Joquina Chiquita M Jones, Medical Research Council Unit, The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; Banjul, The Gambia.

John B Ochieng, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Center for Global Health Research, Kisumu, Kenya.

Jane Juma, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Center for Global Health Research, Kisumu, Kenya.

Alex O Awuor, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Center for Global Health Research, Kisumu, Kenya.

Billy Ogwel, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Center for Global Health Research, Kisumu, Kenya.

Jennifer R Verani, Division of Global Health Protection, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nairobi, Kenya.

Marc-Alain Widdowson, Division of Global Health Protection, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nairobi, Kenya.

Irene N Kasumba, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Sharon M Tennant, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Anna Roose, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Pediatrics, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Syed M A Zaman, Medical Research Council Unit, The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; Banjul, The Gambia.

Jie Liu, Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA; School of Public Health at Qingdao University, Qingdao, China.

Ciara E Sugerman, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

James A Platts-Mills, Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA.

Eric R Houpt, Centre pour le Développement des Vaccins du Mali (CVD-Mali), Bamako, Mali.

Karen L Kotloff, Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Pediatrics, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Eric D Mintz, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the families who participated in these studies; the clinical and field staff for their exceptional hard work and dedication; and the physicians, administration, and health officials at every site who generously provided facilities and support for the conduct of the study. The authors are grateful to Catherine Johnson, Chris Focht, and Nora Watson at the Emmes Company, LLC, for expert data management and reporting. Special thanks go to Carl Kirkwood, Duncan Steele, and Anita Zaidi at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for helpful oversight; Kathy Neuzil for thoughtful suggestions; and the following members of our International Scientific Advisory Committee for providing insightful comments and guidance: Janet Wittes (chair), George Armah, John Clemens, Christopher Duggan, Stephane Helleringer, Ali Mokdad, James Nataro, and Halvor Sommerfelt.

Supplement sponsorship. This supplement was sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This study is based on research funded in part by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1111236/OPP1116751).

Disclaimer. The funding organizations had no role in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the writing of the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Kenya Medical Research Institute, University of Maryland, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), or any of the collaborating partners in this project.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant OPP1111236 and OPP1116751).

References

- 1. Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396:1204–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Troeger C, Forouzanfar M, Rao PC, et al. Estimates of global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoeal diseases: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:909–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Troeger C, Blacker BF, Khalil IA, et al. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:1211–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rogawski McQuade ET, Liu J, Platts-Mills JA, et al. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to investigate the effect of enteropathogen infections on linear growth in children in low-resource settings: longitudinal analysis of results from the MAL-ED cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6:e1319–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Knee J, Sumner T, Adriano Z, et al. Risk factors for childhood enteric infection in urban Maputo, Mozambique: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0006956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rogawski McQuade ET, Platts-Mills JA, Gratz J, et al. Impact of water quality, sanitation, handwashing, and nutritional interventions on enteric infections in rural Zimbabwe: the Sanitation Hygiene Infant Nutrition Efficacy (SHINE) trial. J Infect Dis 2020; 221:1379–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kosek MN, Ahmed T, Bhutta Z, et al. Causal pathways from enteropathogens to environmental enteropathy: findings from the MAL-ED birth cohort study. EBioMedicine 2017; 18:109–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown J, Cumming O. Stool-based pathogen detection offers advantages as an outcome measure for water, sanitation, and hygiene trials. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020; 102:260–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pickering AJ, Null C, Winch PJ, et al. The WASH Benefits and SHINE trials: interpretation of WASH intervention effects on linear growth and diarrhoea. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7:e1139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wagner EG, Lanoix JN. Excreta disposal for rural areas and small communities. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolf J, Hunter P, Freeman M, et al. The impact of drinking water, sanitation and hand washing with soap on childhood diarrhoeal disease: updated meta-analysis and -regression. Trop Med Int Health 2018; 23:508–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berendes D, Leon J, Kirby A, et al. Household sanitation is associated with lower risk of bacterial and protozoal enteric infections, but not viral infections and diarrhea, in a cohort study in a low-income urban neighborhood in Vellore, India. Trop Med Int Health 2017; 22:1119–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Delahoy MJ, Wodnik B, McAliley L, et al. Pathogens transmitted in animal feces in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2018; 221:661–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund . Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene: 2017 update and SDG baselines. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2017. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/JMP-2017-report-launch-version_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berendes DM, O’Reilly CE, Kim S, et al. Diarrhoea, enteric pathogen detection and nutritional indicators among controls in the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, Kenya site: an opportunity to understand reference populations in case-control studies of diarrhoea. Epidemiol Infect 2018; 147:e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Muhsen K. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS): impetus, rationale, and genesis. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:215–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kotloff KL, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, et al. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) of diarrheal disease in infants and young children in developing countries: epidemiologic and clinical methods of the case/control study. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:S232–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study. GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 2013; 382:209–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kotloff KL, Sow SO, Hossain MJ, et al. Changing landscape of moderate-to-severe diarrhea among children in 3 sub-Saharan African countries following rotavirus vaccine introduction: the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA). in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levine MM, Nasrin D, Acácio S, et al. Diarrhoeal disease and subsequent risk of death in infants and children residing in low-income and middle-income countries: analysis of the GEMS case-control study and 12-month GEMS-1A follow-on study. Lancet Glob Health 2020; 8:e204–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Powell H, Liang Y, Roose A, et al. A description of the statistical methods for the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) study. Clin Infect Dis. 2023; 76(Suppl 1):S5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu J, Platts-Mills JA, Juma J, et al. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to identify causes of diarrhoea in children: a reanalysis of the GEMS case-control study. Lancet 2016; 388:1291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2015; Available at: https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 1 June 2022.

- 24. Halekoh U, Højsgaard S, Yan J. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J Stat Softw 2006; 15:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hale CR, Scallan E, Cronquist AB, et al. Estimates of enteric illness attributable to contact with animals and their environments in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:S472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berendes DM, Fagerli K, Kim S, et al. Survey-based assessment of water, sanitation, and animal-associated risk factors for moderate-to-severe diarrhea in the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) study: The Gambia, Mali, and Kenya, 2015–2018. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76(Suppl 1):S132–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mosites E, Sammons M, Otiang E, et al. Microbiome sharing between children, livestock and household surfaces in western Kenya. PLoS One 2017; 12:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pehrsson EC, Tsukayama P, Patel S, et al. Interconnected microbiomes and resistomes in low-income human habitats. Nature 2016; 533:212–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prendergast AJ, Gharpure R, Mor S, et al. Putting the “A” into WaSH: a call for integrated management of water, animals, sanitation, and hygiene. Lancet Planet Health 2019; 3:e336–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Platts-Mills JA, Babji S, Bodhidatta L, et al. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: a multisite birth cohort study (MAL-ED). Lancet Glob Health 2015; 3:564–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Platts-Mills JA, Liu J, Rogawski ET, et al. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to assess the aetiology, burden, and clinical characteristics of diarrhoea in children in low-resource settings: a reanalysis of the MAL-ED cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6:e1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ropkins K, Beck AJ. Evaluation of worldwide approaches to the use of HACCP to control food safety. Trends Food Sci Technol 2000; 11:10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Penakalapati G, Swarthout J, Delahoy MJ, et al. Exposure to animal feces and human health: a systematic review and proposed research priorities. Environ Sci Technol 2017; 51:11537–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Beutin L, Fach P. Detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from nonhuman sources and strain typing. Microbiol Spectr 2014; 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stromberg ZR, Redweik GAJ, Mellata M. Detection, prevalence, and pathogenicity of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from cattle hides and carcasses. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2018; 15:119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Karmali MA. Emerging public health challenges of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli related to changes in the pathogen, the population, and the environment. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:371–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Croxen MA, Law RJ, Scholz R, Keeney KM, Wlodarska M, Finlay BB. Recent advances in understanding enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26:822–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kim JS, Lee MS, Kim JH. Recent updates on outbreaks of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and its potential reservoirs. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020; 10:273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lupindu AM, Olsen JE, Ngowi HA, et al. Occurrence and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other non-sorbitol-fermenting E. coli in cattle and humans in urban areas of Morogoro, Tanzania. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis 2014; 14:503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Islam MA, Mondol AS, De Boer E, et al. Prevalence and genetic characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from slaughtered animals in Bangladesh. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008; 74:5414–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thomas KM, de Glanville WA, Barker GC, et al. Prevalence of Campylobacter and Salmonella in African food animals and meat: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Food Microbiol 2020; 315:108382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bauza V, Madadi V, Ocharo R, Nguyen TH, Guest JS. Enteric pathogens from water, hands, surface, soil, drainage ditch, and stream exposure points in a low-income neighborhood of Nairobi, Kenya. Sci Total Environ 2019; 709:135344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zambrano LD, Levy K, Menezes NP, Freeman MC. Human diarrhea infections associated with domestic animal husbandry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2014; 108:313–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ngure FM, Humphrey JH, Mbuya MNN, et al. Formative research on hygiene behaviors and geophagy among infants and young children and implications of exposure to fecal bacteria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 89:709–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rukambile E, Sintchenko V, Muscatello G, Kock R, Alders R. Infection, colonization and shedding of Campylobacter and Salmonella in animals and their contribution to human disease: a review. Zoonoses Public Health 2019; 66:562–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carron M, Chang Y-M, Momanyi K, et al. Campylobacter, a zoonotic pathogen of global importance: prevalence and risk factors in the fast-evolving chicken meat system of Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Humphrey JH, Mbuya MNN, Ntozini R, et al. Independent and combined effects of improved water, sanitation, and hygiene, and improved complementary feeding, on child stunting and anaemia in rural Zimbabwe: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7:e132–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Harvey SA, Winch PJ, Leontsini E, et al. Domestic poultry-raising practices in a Peruvian shantytown: implications for control of Campylobacter jejuni-associated diarrhea. Acta Trop 2003; 86:41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Delahoy MJ, Omore R, Ayers TL, et al. Clinical, environmental, and behavioral characteristics associated with Cryptosporidium infection among children with moderate-to-severe diarrhea in rural western Kenya, 2008–2012: the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0006640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. World Health Organization . Guidelines for drinking-water quality. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Medgyesi D, Sewell D, Senesac R, Cumming O, Mumma J, Baker KK. The landscape of enteric pathogen exposure of young children in public domains of low-income, urban Kenya: the influence of exposure pathway and spatial range of play on multi-pathogen exposure risks. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019; 13:e0007292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Levine MM, Robins-Browne RM. Factors that explain excretion of enteric pathogens by persons without diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:303–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kiulia NM, Hofstra N, Vermeulen LC, Obara MA, Medema G, Rose JB. Global occurrence and emission of rotaviruses to surface waters. Pathogens 2015; 4:229–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kraay ANM, Brouwer AF, Lin N, Collender PA, Remais JV, Eisenberg JNS. Modeling environmentally mediated rotavirus transmission: the role of temperature and hydrologic factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115:E2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Church JA, Rukobo S, Govha M, et al. The impact of improved water, sanitation and hygiene on oral rotavirus vaccine immunogenicity in Zimbabwean infants: sub-study of a cluster-randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:2074–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Delahoy MJ, Cárcamo C, Ordoñez L, et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination varies by level of access to piped water and sewerage: an analysis of childhood clinic visits for diarrhea in Peru, 2005–2015. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020; 39:756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fuller JA, Eisenberg JNS. Herd protection from drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016; 95:1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fuller JA, Westphal JA, Kenney B, Eisenberg JNS. The joint effects of water and sanitation on diarrhoeal disease: a multicountry analysis of the demographic and health surveys. Trop Med Int Health 2015; 20(3):284–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.