Abstract

Despite extensive use of primary aromatic amines (AAs) in consumer products, little is known about their occurrence in the environment. In this study, we investigated the occurrence of 14 AAs and nicotine in 75 sediment samples collected from seven estuarine and freshwater ecosystems in the Unites States. Additionally, risk quotients (RQs) were calculated to assess potential risks of these chemicals to aquatic organisms. Of the 14 AAs analyzed, seven of them were found in sediments. The sum concentrations of seven AAs in sediments were in the range of 10.2 to 1810 ng/g, dry wt (mean: 388 ng/g). Aniline was the most abundant compound, accounting for, on average, 53% of the total concentrations. Nicotine was found in sediments at a concentration range of <LOQ to 1340 ng/g, dry wt (mean: 119 ng/g). Among the seven sampling locations studied, AAs and nicotine concentrations were the highest in sediment from Altavista wastewater lagoon in Virginia (AV, mean: 1700 ng/g) followed in descending order by Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (CSSC, mean: 807 ng/g), Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal (IHSC, mean: 698 ng/g) and New Bedford Harbor (NBH, mean: 482 ng/g). Sediments from the upper Mississippi River (MISS, mean: 63.4 ng/g) and Tittabawassee River (TBR, mean: 52.3 ng/g) contained the lowest concentrations. The RQ values for AAs in sediment ranged from 0 to 733 and that for nicotine ranged from 0 to 2060. Among AAs, the highest RQ value was found for 4-chloroaniline. Nicotine exhibited notable RQ values, which suggested risk from this chemical to aquatic organisms. This is the first study to report the occurrence of AAs in sediments and our results suggest the need for further investigations on the sources and ecological impacts of these chemicals in aquatic ecosystems.

Keywords: aromatic amine, aniline, sediment, risk, nicotine

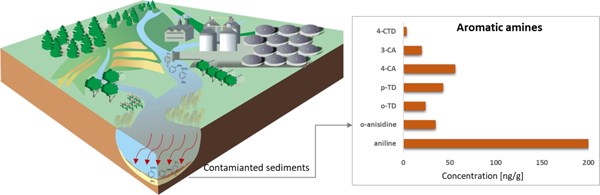

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Primary aromatic amines (AAs) are organic chemicals consisting of an aromatic ring attached to an amine, and are building blocks in the production of textile dyes, agrochemicals, and other synthetic chemicals (IARC, 2010a). For decades, AAs were produced in large quantities for the manufacture of food colorants, textiles, rubber, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, pesticides, and explosives (Favaro Perez et al., 2021; Padahe et al., 2021; Merkel et al., 2018; Campanella et al., 2015; Ros et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2010; Andrew et al., 2004; Turesky et al., 2003). Aniline, the building block of AAs, is a high production volume chemical (USEPA, 2020; OECD, 2009; Käfferlein et al., 2014), with a global production of 8.4 million tons in 2020 (Mohammed et al., 2020). The production of aniline in the USA in 2011 was ~887 000 tons, whereas that in 2012–2015, it was 2.3 million tons (ChemView, 2016). The USA is also the third-largest consumer of aniline, accounting for 17% of its global consumption (IHS Markit, 2019). AAs are also found in cigarette butts, tobacco smoke and diesel exhaust (Dobaradaran et al., 2022; WHO, 2021). Nicotine is a constituent of tobacco smoke, with annual global consumption of ~50 000 tons (WHO, 2021; van Wel et al., 2016).

Studies have shown that AAs and nicotine are carcinogenic and endocrine disrupting chemicals, which can enter the aquatic environment through the discharge of wastewater (Weber et al., 2001; Government Canada, 1994). Based on a model, the UNEP (2005) reported that the major sink for AAs in the environment is aquatic ecosystems (84%) followed by atmosphere (16%). Studies have reported the occurrence of AAs in surface-, ground- and drinking water at concentrations ranging from 500 ng/L in drinking water to 20,000 mg/L in wastewater (Neurath et al., 1977; Greve and Wegman, 1975; Meijers and van der Leer, 1976; Herzel and Schmidt, 1977; Shackelford and Keith, 1976; Hushon et al., 1980; Government Canada, 1994; Rockett et al., 2014; Anastacio Ferraz et al., 2012; He et al., 2014; Albahnasawi et al., 2020). Aquatic environment is the major sink for nicotine (93%), followed by soil (4%) and air (3%) (Seckar et al., 2008). High concentrations of nicotine have been found in wastewater (up to 424,000 ng/L) and surface water ( up to 9,340 ng/L) (Verovsek et al., 2022; Oropesa et al., 2017; Benotti and Brownawell, 2007; Wang et al., 2001; Kaiser et al., 1996). Studies have also shown that 80% of AAs, especially aniline, are covalently bound in sediments with half-lives of approximately 3500 days (Weber et al., 2001; ECHA, 2019; Giersing et al., 2009). Thus, sediments can be a sink for AAs in the aquatic environment. Although recent studies reported occurrence of AAs and nicotine in human urine and indoor dust (Chinthakindi et al., 2022; Chinthakindi and Kannan, 2022a,b; Chinthakindi and Kannan, 2021), there is limited information on the magnitude of contamination by these compounds in the aquatic ecosystems (ChemView, 2016; IHS Markit, 2019).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the occurence of AAs and nicotine simultaneously in sediments from US aquatic ecosystems. The aim of this study was to determine the concentrations and frequency of occurrence of 14 AAs and nicotine in 75 sediment samples collected from seven freshwater and estuarine ecosystems in the United States. We further assessed ecological risks of AAs and nicotine in sediments, based on the reported, predicted no-effect concentrations (PNEC) in sediment for these chemicals.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sampling

A total of 75 sediment samples were collected between 2004 and 2017 from seven water bodies covering six states in the United States: New Bedford Harbor (NBH, n=24; collected in 2017), Massachusetts; Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (CSSC, n=9, collected in 2013), Illinois; Altavista wastewater lagoon (AV, n=6, collected in 2015), Virginia; Upper Mississippi River (MISS, n=13, collected in 2012), Iowa; Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal (IHSC, n=3, collected in 2006), Indiana; and Saginaw Bay (SB, n=8, collected in 2004) and Tittabawassee River (TBR, n=11, collected in 2004), Michigan. Further details of the samples are provided in the Supplementary Information (Table S1. Fig. S1). Sediment samples were collected using a dredge or grab sampler. Surface sediment (0–12”) was used for analysis. Sediment sample from each location was homogenized, and stored in pre-cleaned amber jars, and transported to the laboratory. Prior analysis samples were freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C.

2.2. Chemicals and reagents

Fifteen native standards (NS) and 9 isotopically labeled internal standards (IS)(see Table S2 for chemical names and their abbreviations) of 95–99% purity were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (TRC; Toronto, ON, Canada), AccuStandard (New Haven, CT, USA) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The names of target analytes, abbreviations and Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) numbers are shown in Table S2. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade solvents, namely water, methanol, and methyl t-butyl ether (MTBE) were purchased from J. T. Baker (Center Valley, PA, USA). Analytical-grade formic acid (HCOOH), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and hydrochloric acid (HCl; 37%, v/v) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Glass tubes (16 × 100 mm) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3. Chemical analysis

Sediment samples were extracted by ultrasonication. Briefly, 0.5 g of freeze-dried sediment was weighed into a glass tube, fortified with 10 ng each of isotopically labeled IS, and equilibrated for 30 min. Four milliliters of HPLC grade water and 50 µL of 10 M NaOH were added, vortexed for 1 min, and sonicated (at 40 kHz) at room temperature (22°C) using a Branson 3510 R-DTH sonicator for 30 min (Branson Ultrasonics Corporation, Danbury, CT, USA) followed by shaking on an orbital shaker (at 180 strokes per min) for 30 min (Eberbach Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Samples were centrifuged at 2880 × g for 20 min (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5804, Hamburg, Germany) and the aqueous layer was transferred into a 15 mL polypropylene (PP) tube. The aqueous layer was extracted with 3 mL of MTBE by shaking in an orbital shaker at 180 strokes per min for 30 min and then centrifuged at 2880 × g for 10 min. The MTBE layer was transferred into another 15 mL PP tube and the extraction was repeated with additional 3 mL of MTBE. The MTBE extracts were combined and fortified with 15 µL of 0.25M HCl and evaporated to near-dryness under a gentle N2 stream. The residue was then reconstituted with 200 µL of water: methanol mixture (9:1 v/v) and transferred into a vial with a 300 µL glass insert for instrumental analysis.

2.4. Instrumental analysis

Analysis of AAs and nicotine was performed on a Shimadzu LC-30 AD series HPLC coupled to a Sciex QTRAP 5500 tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Target analytes were chromatographically separated on an Ultra BiPh column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 5 µm; Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA) connected to a Betasil C18 guard column (20 mm × 2.1 mm, 5 µm; Thermo Scientific, West Palm Beach, FL, USA) using formic acid (0.1%) in a water/methanol mixture (95:5, v/v) (A), and 0.1% formic acid in methanol (B) as the mobile phases. The mobile phase gradient program was as follows: 95% A (min 0), 95%–58% A (min 0.01–2.50), 58%–25% A (min 2.50–6.50), 25%–5% A and a hold for 1 min (min 6.50–8.70), 5%–95% A (min 8.70–9.70), and a hold for 2.50 min (min 9.70–10.00), for a total run time of 12.5 min. The mobile phase flow rate was 0.3 mL/min and the sample injection volume was 5 µL.

Identification of target analytes was performed using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) in electrospray positive ionization mode (ESI+-MS/MS). The compound-specific MS/MS parameters including collision energy, declustering potential, entrance potential, and collision exit potential were optimized, and are summarized in Table S2. The MS ion source temperature and ion spray voltage were set at 500°C and 4500 V, respectively. The collision gas and curtain gas flow rates were set at 8 and 20 psi, respectively. The gas 1 and gas 2 flow rates were set at 30 and 30 psi, respectively.

2.5. Quality assurance and quality control

The analytes were quantified against an external calibration curve constructed with native and isotopically labeled ISs. Nine of the 15 target analytes had corresponding isotopically labeled IS. For the remaining analytes, IS was selected based on the structural similarity. A nine-point calibration curve, prepared at concentrations of analytes ranging from 0.1 to 50 ng/mL (with 10 ng/mL IS mixture), showed regression coefficients >0.999. Relative recoveries (%) of target analytes were determined in triplicate experiments by fortifying a sediment (sample # 16) at a concentration of 10 ng/g each for both native and internal standards, and passed through the entire analytical procedure. The mean recoveries of target analytes were in the range of 47% (2-aminobiphenyl [ABP]) - 144% (2,6-dimethylaniline [DMA]). The lowest acceptable calibration concentrations divided by a nominal sample weight of 0.5 g were used in the calculation of limits of quantification (LOQs), which were in the range of 0.2–1.0 ng/g, dry wt (Table S3). A solvent blank and a midpoint calibration standard were injected after every 10 samples to monitor for carryover of target analytes and drift in instrumental sensitivity, respectively.

2.6. Risk assessment

A risk quotient (RQ) approach was used in the assessment of potential ecological risks of AAs and nicotine in sediments. RQ values were calculated by dividing the measured AA or nicotine concentration (MEC) in sediment by the predicted no-effect concentration (PNECsed), derived from toxicity studies using aquatic invertebrates namely Daphnia magna, Chironomus riparius or Lumbriculus variegatus (Kucharski et al., 2022):

RQ = MECsed/ PNECsed

where:

MECsed- measured concentration in sediment [ng/g, dry wt].

PNECsed- predicted no-effect concentration in sediment [ng/g, dry wt].

The PNECsed values for aniline, o-anisidine, o/m-toluidine and nicotine have been reported in the literature (Table S10). The PNECsed for p-toluidine was calculated from the reported PNECwater as below:

PNECsed =(Kd/Rhosusp) x PNECwater x1000 (Kucharski et al., 2022)

where:

PNECwater – predicted no-effect concentration in water was 0.12 μg/L (UNEP, 2005).

Kd – distribution coefficient of the chemical between water and sediment.

Rhosusp – bulk density of wet sediment, and we used a value of 1150 kg/m3.

PNECsed for 4-chloroanaliline (4-CA) and 3-chloroaniline (3-CA) were estimated from the results of chronic toxicity studies, by dividing EC50 by a factor of 1000 (Kucharski et al., 2022; ECHA, 2003).

The PNECsed values for aniline, o-anisidine, o-/m-toluidine (o-/m-TD), p-toluidine (p-TD), 4-chloroaniline (4-CA), 3-chloroaniline (3-CA) and nicotine are 153, 8, 2, 2.09, 0.54, 0.54 and 0.65 ng/g, dry wt, respectively. A RQ value of >1 is suggestive of a potential risk posed by the contaminant on sediment dwelling aquatic organisms.

2.7. Data analysis

The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to verify whether there are statistically significant differences between the concentrations among different sites. Another non-parametric test, Mann-Whitney pairwise test, was used to compare differences in concentrations between samples collected from two different locations. The significance was set at p≤0.05. The correlation between AAs and nicotine was tested using Spearman’s correlation test. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to evaluate the multivariate ordination of AAs and nicotine concentrations among various locations. Prior to performing the PCA, the raw data were normalized by subtracting from the mean value and dividing by the standard deviation. Hierarchical cluster analysis was then performed to determine the differences in concentration patterns among samples. All analyses were performed using PAST 4.0 software. Data are presented on a dry weight basis unless specified otherwise.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Concentrations of AAs and nicotine in sediments

Of the 14 AAs targeted, seven, namely aniline, o-anisidine, o-/m-TD, p-TD, 3-CA, 4-CA and 4-chloro-o-toluidine (4-CTD), were found in sediments and their sum concentrations (∑7AAs) ranged from 10.2 (TBR) to 1810 ng/g, dry wt (AV) (Table 1). The concentrations were significantly different among the seven water bodies studied (Kruskal-Wallis test, p≤0.05; Table S4). The lowest mean concentrations of ∑7AAs were found in sediments from the TBR (51.8 ng/g) and the MISS (60.1 ng/g) whereas the highest mean concentrations were measured in sediments from AV (935 ng/g), followed by CSSC (697 ng/g), IHSC (615 ng/g), NBH (482 ng/g), and SB (275 ng/g). For nicotine, the highest mean concentrations were found in sediments from AV (760 ng/g), followed in decreasing order by CSSC (129 ng/g), NBH (112 ng/g), IHSC (83.4 ng/g) MISS (3.27 ng/g) and TBR (0.480 ng/g) (Table 1). Nicotine concentrations in sediment from AV were significantly higher than those in other samples (Mann-Whitney pairwise test, p≤0.05; Table S7).

Table 1.

Concentrations (ng/g, dry weight) of primary aromatic amines and nicotine in sediments collected from seven waterbodies in the United States.1

| Sampling Location | aniline | o-anisidine | o/m-TD | p-TD | 4-CA | 3-CA | 4-CTD | ∑AAs | nicotine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBH -New Bedford Harbor, Massachusetts (n = 24) | min | 119 | 3.86 | 5.58 | 19.8 | 32.7 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 210 | 23.6 |

| max | 730 | 42.0 | 87.4 | 179 | 175 | 17.8 | 11.6 | 1140 | 284 | |

| mean | 307 | 14.9 | 27.1 | 59.1 | 63.3 | 6.37 | 3.35 | 482 | 112 | |

| median | 288 | 12.6 | 22.8 | 41.9 | 52.4 | 5.22 | 2.63 | 434 | 97.2 | |

| DF (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 80.9 | 95.8 | 100 | ||

| CSSC -Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, Illinois (n = 9) | min | 29.1 | 1.52 | 3.90 | 7.19 | 11.8 | 2.59 | <LOQ | 56.2 | 9.73 |

| max | 557 | 325 | 143 | 155 | 181 | 110 | 26.5 | 1130 | 314 | |

| mean | 321 | 82.4 | 57.7 | 67.4 | 105 | 40.2 | 5.22 | 679 | 129 | |

| median | 353 | 46.2 | 54.8 | 63.4 | 96.2 | 35.8 | 2.77 | 688 | 98.9 | |

| DF (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| AV – Altavista wastewater lagoon, Virginia (n = 6) | min | 34.5 | 2.30 | 4.33 | 5.01 | 24.4 | 22.1 | 2.03 | 116 | 262 |

| max | 509 | 407 | 55.1 | 93.7 | 395 | 330 | 76.0 | 1800 | 1340 | |

| mean | 303 | 182 | 28.2 | 41.8 | 204 | 154 | 22.0 | 935 | 760 | |

| median | 300 | 158 | 26.9 | 36.6 | 179 | 159 | 14.2 | 867 | 757 | |

| DF (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| MISS -Mississippi River, Iowa (n = 13) | min | 4.73 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | nd | 13.5 | <LOQ |

| max | 66.4 | 53.7 | 12.3 | 29.5 | 16.3 | 0.110 | nd | 135 | 10.9 | |

| mean | 31.1 | 15.2 | 3.32 | 5.42 | 5.04 | 0.0200 | nd | 60.1 | 3.27 | |

| median | 26.1 | 8.04 | 2.35 | 2.41 | 4.02 | 0.00 | nd | 60.5 | 1.73 | |

| DF (%) | 100 | 84.7 | 92.3 | 69.3 | 76.9 | 15.3 | nd | 76.9 | ||

| IHSC - Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal, Indiana (n = 3) | min | 108 | 1.27 | 43.2 | 90.3 | 27.9 | <LOQ | nd | 271 | 42.6 |

| max | 433 | 3.73 | 97.3 | 306 | 102 | 4.12 | nd | 942 | 117 | |

| mean | 280 | 2.77 | 69.2 | 204 | 57.7 | 1.37 | nd | 615 | 83.7 | |

| median | 299 | 3.31 | 67.0 | 214 | 43.8 | 0.00 | nd | 632 | 91.4 | |

| DF (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 33.3 | nd | 100 | ||

| SB - Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron, Michigan (n = 8) | min | 15.5 | 4.25 | 4.03 | 4.78 | <LOQ | <LOQ | nd | 32.6 | 0.00 |

| max | 569 | 27.2 | 25.6 | 64.5 | 45.9 | 9.73 | nd | 709 | 23.5 | |

| mean | 198 | 10.4 | 16.0 | 25.4 | 21.9 | 3.28 | nd | 275 | 10.5 | |

| median | 144 | 6.42 | 17.3 | 17.5 | 23.2 | 2.02 | nd | 241 | 8.02 | |

| DF (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50.0 | nd | 75.0 | ||

| TBR - Tittabawassee River, Michigan (n = 11) | min | 4.22 | 3.05 | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0.08 | 0.00 | nd | 10.2 | 0.00 |

| max | 169 | 25.5 | 34.7 | 16.4 | 20.1 | 0.00 | nd | 266 | 4.69 | |

| mean | 30.9 | 7.84 | 6.16 | 2.42 | 4.48 | 0.00 | nd | 51.8 | 0.48 | |

| median | 16.7 | 5.42 | 2.58 | 0.00 | 2.92 | 0.00 | nd | 32.1 | 0.00 | |

| DF (%) | 100 | 100 | 72.7 | 45.4 | 100 | 0.00 | nd | 36.3 | ||

| min | 4.22 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 10.25 | <LOQ | |

| Total (n=75) | max | 730 | 408 | 143 | 307 | 396 | 331 | 76.0 | 1800 | 1340 |

| mean | 206 | 34.7 | 24.1 | 43.1 | 56.1 | 19.9 | 3.51 | 388 | 119 | |

| median | 169 | 11.6 | 15.9 | 28.0 | 36.6 | 0.550 | 0.470 | 303 | 35.9 |

Aniline; o-anisidine; o/m-TD, ortho/meta-toluidine; p-TD, para-toluidine; 4-CA, 4-chloroaniline; 3-CA, 3-chloroaniline; 4-CTD, 4-chloro-o-toluidine; nicotine. nd - not detected. DF- detection frequency; LOQ- limit of quantification.

Among seven AAs, aniline was the most abundant compound found in all sediment samples (Table 1). The highest and lowest aniline concentrations were found in sediments from NBH (range: 119–730 ng/g, mean: 307 ng/g) and the TBR (4.22–169 ng/g, 30.9 ng/g), respectively. 4-CA was the second abundant AA found in all sediment samples. The highest concentrations of 4-CA were found in sediment collected from AV (24.4–395 ng/g, 204 ng/g) and the lowest concentrations were found in sediments from the TBR (0.0800–20.1 ng/g, 4.48 ng/g).

The percentage composition of individual AA to the sum of the mean concentration of seven AAs (∑7AAs) is shown in Fig. 1. Aniline accounted for 32.4% to 72.0% of the ∑7AAs concentrations, with a mean value of 53.0% (Fig.1), followed in descending order by 4-CA (range: 8.00%−21.8%, mean: 12.0%), p-TD (4.50%−33.1%, 11.9%), and o-anisidine (0.500%−25.2%, 11.3%). The proportion of o/m-TD and 3-CA in ∑7AAs concentrations was <8.00% and <4.00%, respectively (Fig. 1). Besides being used in several products including dyes, rubber, herbicides and pharmaceuticals (USEPA, 2020; OECD, 2009; Käfferlein et al., 2014), aniline, the simplest of AA, is formed from the degradation of several other AAs (Arora, 2015; Chinthakindi et al., 2022). This would explain elevated composition of aniline in sediments. 4-CA is a high production volume chemical with an annual production of 250–500 tons in 2016 in the United States and is used in the manufacture of dyes, pesticides and drugs. o-Anisidine was reported to be present at high concentrations in freshly smoked and aged cigarette butts (Dobaradaran et al., 2022).

Fig 1.

Composition profiles (%) of primary aromatic amines in sediments collected from the United States (NBH – New Bedford Harbor; CSSC – Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal; AV- Altavista wastewater lagoon; MISS – upper Mississippi River; IHSC – Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal; SB -Saginaw Bay; TBR – Tittabawassee River; o/m-TD - ortho/meta-toluidine; p-TD- para-toluidine; 4-CA- 4-chloroaniline; 3-CA- 3-chloroaniline; 4-CTD- 4-chloro-o-toluidine).

Our results suggest the widespread occurrence of AAs and nicotine in sediment from freshwater and estuarine waters in the United States. Aniline and several other AAs have been used in more than 300 consumer products (Chinthakindi and Kannan, 2021). These chemicals may arise from dyes, rubber, varnishes, cosmetics, polyurethane foam, and agrochemicals (Albahnasawi et al., 2020; He et al., 2014; Rockett et al., 2014; Anastacio Ferraz et al., 2012; Weber et al., 2001; Rippen, 1990). Earlier studies have reported elevated concentrations of AAs and nicotine in untreated wastewater (up to 5780 ng/L) and textile sludge (up to 82500 ng/g) (Gracia-Lor et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020; Van Wel et al., 2016; Ning et al., 2015; Senta et al., 2015). The high concentrations of AAs and nicotine found in AV can be, therefore, related to sources arising from industrial sewage (SAP, 2005). In fact, sediments from AV were collected from a wastewater lagoon, which received discharges from local textile and furniture industries (e.g. Burlington Industries, Lane Furniture Company) (SAP, 2005; VADEQ, 1999), and that would explain the highest concentrations of AAs and nicotine found in those samples. Studies reporting AA concentrations in sediments are scarce. Akyuz and Ata (2006) reported aniline, m-toluidine, 3-CA and 4-CA in sediments from Turkey at mean concentrations 192, 0.35, 10.4 and 0.19 ng/kg, dry wt, respectively. Jurado-Sanchez et al. (2013), found five AA compounds namely aniline, 2-CA, 3-CA, 2,4,5-trichloroaniline and 2,4,6-trichloroaniline in sediments from Spain at concentrations ranging from 0.40 to 1.3 ng/g, dry wt. The reported concentrations of aniline, m-toluidine, 3-CA and 4-CA from Turkey and Spain are much lower than those found in our study. In China, Hu et al. (2020) measured concentrations of five AAs namely, phenylamine, 4-chlorophenylamine, 1-naphthalenamine, diphenylamine, and 4-aminobiphenyl in sediments from Dianchi Lake, at a mean total concentration of 19 ng/g, dry wt. Feng et al. (2007) reported concentrations of two AAs, namely, phenylamine and benzidine in sediments from Zhenjian, Yixing, and Changzhou (China) in the range of <LOD to 55 ng/g, dry wt. However, our study was focused on a different set of AAs and direct comparison with the studies from China was not possible. To our knowledge no other studies are available for comparison of AAs concentrations in sediments.

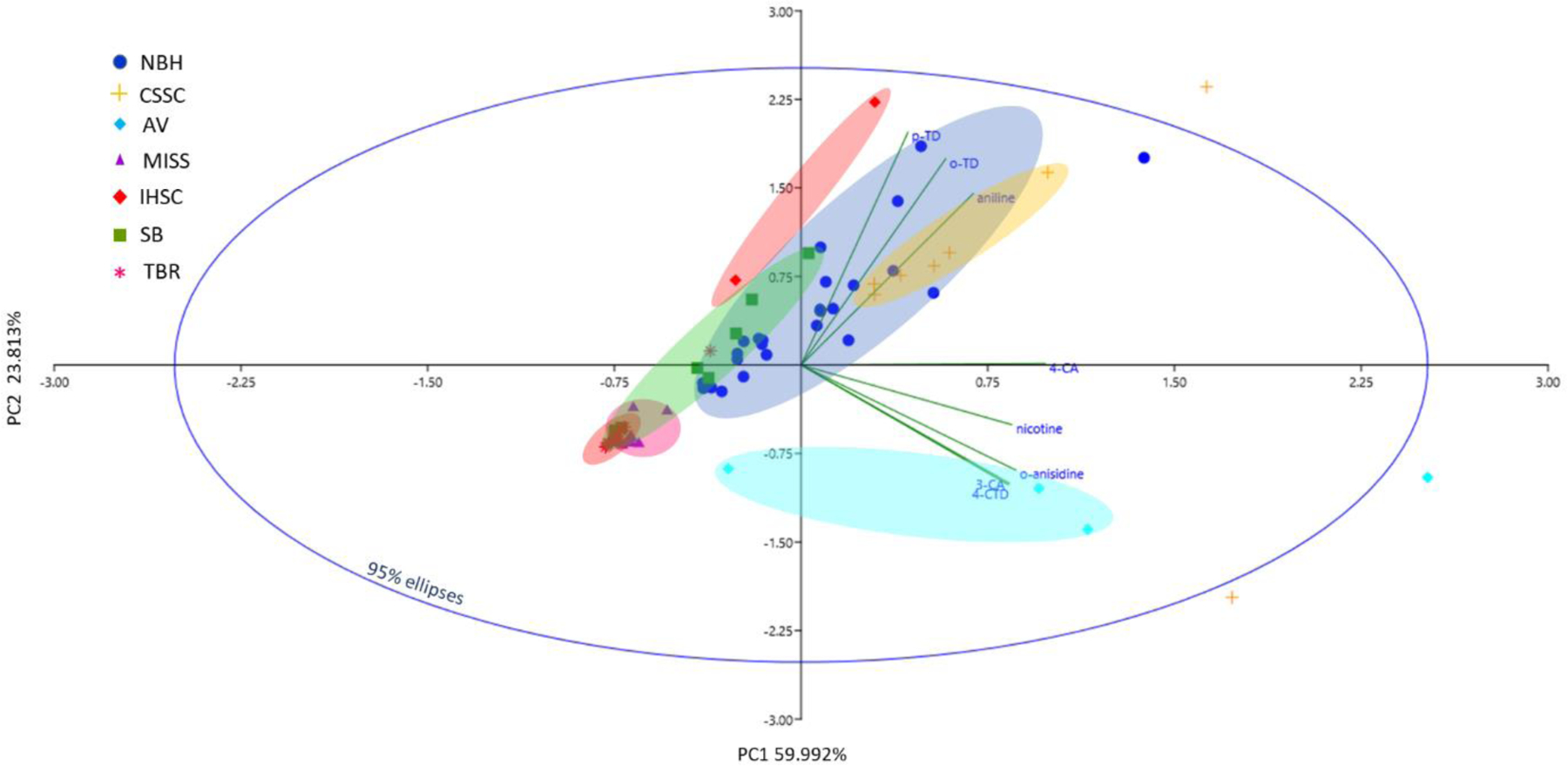

3.2. PCA and correlation analysis

The principal component analysis (PCA) of AA and nicotine concentrations in sediments distinguished less polluted areas (i.e. TBR and MISS) from more highly polluted ones (i.e. CSSC, IHSC and NBH) (Fig. 2). Sediment from AV lagoon, containing the highest concentrations of AAs and nicotine, clustered separately, while sediments from SB with moderate concentrations of AAs, clustered between low- and high- concentration samples. The PCA also displayed a significant contribution of aniline, o/m-TD and p-TD in sediments collected from NBH and CSSC, confirming that these three compounds accounted for most of ∑7AAs concentrations (see Fig. 1). Aniline, o/m-TD, and p-TD correlated positively in principal component 1 (PC1), which explained 60% of the total variance in AAs concentrations. The loadings for o-anisidine, 3-CA and 4-CTD were correlated in principal component 2 (PC2) (24% of the total variance) and with samples collected from AV lagoon (Fig. 2); the three compounds were dominant in AV lagoon sediment samples accounting for 38% of ∑7AAs concentrations (see Fig.1). The loading for nicotine was also correlated in PC2, concurrence with the high concentration of this compound found in AV lagoon sediment samples. The results of PCA were further confirmed by the hierarchical cluster analysis, which showed that AA patterns in sediments from the TBR and MISS were related (the smallest distance), whereas those of AV were farthest in comparison to other sampling sites (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Scatterplot of scores of principal component analysis of concentrations of aromatic amines and nicotine in sediment samples collected from the United States (NBH – New Bedford Harbor; CSSC – Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal; AV- Altavista wastewater lagoon; MISS – upper Mississippi River; IHSC – Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal; SB - Saginaw Bay; TBR – Tittabawassee River; o/m-TD - ortho/meta-toluidine; p-TD- para-toluidine; 4-CA- 4-chloroaniline; 3-CA- 3-chloroaniline; 4-CTD- 4-chloro-o-toluidine).

Spearman’s correlation analysis demonstrated strong positive correlations between aniline and o/m-TD (correlation coefficient, rs=0.82), aniline and p-TD (rs=0.86), and aniline and 4-CA (rs=0.87). Similarly, strong correlations were found between 4-CA and 3-CA (rs=0.74) and 4-CA and 4-CTD (rs=0.81) (Fig. 3, Table S9). p-TD is widely used in the production of dyes, pesticides, pharmaceuticals and as antioxidants in rubber and in the production of polyurethane foam (Hanley et al., 2012; IARC, 2010b; Marand et al., 2004). o/m-TD is an impurity in p-TD formulations. The concentrations of o/m-TD were, on average, 2-fold lower than p-TD concentrations (Table 1). 4-CA is used as an intermediate in the production of colorants for drugs, textiles, cosmetics, tattoo inks, and hair dyes (WHO, 2003). Thus, the significant correlation between aniline and o/m-TD, p-TD, and 4-CA may imply environmental transformation of the latter three compounds into aniline (Kaufman and Blake, 1973). Similar correlations were reported in earlier studies of AAs in indoor dust (Chinthakindi and Kannan, 2022; Chinthakindi et al., 2021). Nicotine was strongly correlated with 4-CA (rs=0.87), p-TD (rs=0.78), aniline (rs=0.77), and o/m-TD (rs=0.68) (Fig. 3, Table S9). Aniline, p-TD, and o/m-TD are the major AAs present in tobacco smoke (Shubert et al., 2011; Stabbert et al., 2003; Luceri et al., 1993). The correlation of nicotine with aniline, o/m-TD, p-TD, and 4-CA suggests similar sources of these chemicals. Considering the high consumption of nicotine each year, cigarette butts and smoke are important sources of AAs in the environment.

Fig. 3.

The Spearman correlation coefficients (rs) between individual aromatic amines and nicotine (rs =0.00–0.19 – very week correlation; 0.20–0.39 -weak correlation; 0.40–0.59- moderate correlation; 0.60–0.79 – strong correlation; 0.80–1.00 – very strong correlation; blank spots indicate no significant correlation at p=0.05); (o/m-TD - ortho/meta-toluidine; p-TD- para-toluidine; 4-CA- 4-chloroaniline; 3-CA- 3-chloroaniline; 4-CTD- 4-chloro-o-toluidine).

3.3. Comparison of AAs with other organic compounds in sediments

Concentrations of several organic contaminants were reported in the same set of sediments analyzed in this study and are compiled in Table S8. Sediments from the MISS showed 3-fold higher concentration of ∑7AAs than the concentration reported for polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) (Martinez et al., 2016). The concentrations of ∑7AAs in sediments from the TBR were an order of magnitude higher than those of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs) and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs) (Hilscherova et al., 2003). The mean concentrations of ∑7AAs in SB sediments were four-fold higher than those of PCBs, and an order of magnitude higher than those of PCDDs and PCDFs (Kannan et al., 2008). In contrast, sediments from CSSC contained much lower concentrations of ∑7AAs than those of PCBs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and organophosphate esters (OPEs) (Peverly et al., 2015). The IHSC is a heavily industrialized urban catchment, and sediments from this canal contained PCBs at concentrations as high as 72000 ng/g (Saktrakulkla et al., 2022; Martinez et al., 2010, 2011), an order of magnitude higher than those of ∑7AAs concentrations. Concentrations of PCBs in sediments from NBH, an urban tidal estuary located in Massachusetts, is on the order of several milligrams per gram (Saktrakulkla et al., 2022), which is two orders of magnitude higher than the concentrations of ∑7AAs measured in our study. PCBs concentrations in AV lagoon sediments (12700 mg/g) (Mattes et al. 2018) were several orders of magnitude higher than those of∑7AAs concentrations. Overall, sediments from MISS, TBR and SB demonstrated higher levels of ∑7AAs in comparison to other legacy organic compounds, whereas samples from heavily contaminated industrial sites such as CSSC, IHSC, NBH and AV contained higher concentrations of legacy organic pollutants (mainly PCBs) than those of ∑7AAs. Further studies on the relationship between AAs and other legacy organic pollutants are needed.

3.4. Ecological risk

The risk quotient (RQ) approach introduced by the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) is a point estimate of exposure and effects (Liu et al., 2018). In this study, RQ values were calculated as the ratios of measured environmental concentration (MEC) in sediment to the predicted no-effect concentration (PNECsed) (Kucharski et al., 2022). The PNECsed values for six AAs and nicotine were derived from chronic toxicity studies of these chemicals on aquatic invertebrates namely Daphnia magna, Chironomus riparius or Lumbriculus variegatus (Table S10).

The RQ values for individual AAs and nicotine are presented in Table 2. The RQs for AAs in several locations exceeded the value of 1.0 (USEPA, 2007). 4-CA exhibited the highest RQs, that ranged from 0 to 733 with mean values for each study site ranging from 8.29 (TBR) to 378 (AV). Aniline showed lower RQs in the range of 0 to 51, with mean values ranging from 0.200 (TBR) to 2.10 (CSSC). One study reported that among four anilines tested (aniline, 4-chloroaniline, 3,5-dichloroaniline and 2,3,4-trichloroaniline), 4-CA was the most toxic and aniline was the least toxic to algae P. subcapitata (Dom et al. 2010). Vazquez and Rial (2014) reported that aniline was less toxic than cyclododecane and naphthalene to selected bacteria (Pseudomonas sp., Phaeobacter sp. and Euconostoc mesenteroides).

Table 2.

Calculated risk quotient (RQ) values for aromatic amines and nicotine in sediments collected from the United States.

| Sampling Location | aniline | o-anisidine | o/m-TD | p-TD | 4-CA | 3-CA | nicotine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBH -New Bedford Harbor, Massachusetts (n = 24) | min | 0.780 | 0.480 | 2.79 | 9.46 | 60.7 | 0 | 36.3 |

| max | 4.77 | 5.25 | 43.7 | 86.0 | 325 | 32.9 | 438 | |

| mean | 2.01 | 1.87 | 13.6 | 28.3 | 117 | 11.8 | 173 | |

| SD | 0.980 | 1.24 | 8.84 | 21.9 | 61 | 11.3 | 105 | |

| CSSC -Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, Illinois (n = 9) | min | 0.190 | 0.190 | 1.95 | 3.44 | 21.9 | 4.81 | 15.0 |

| max | 3.64 | 40.6 | 71.4 | 74.1 | 335 | 203 | 483 | |

| mean | 2.10 | 10.3 | 28.9 | 32.3 | 195 | 74.5 | 198 | |

| SD | 0.980 | 11.7 | 18.9 | 21.2 | 82 | 54.7 | 159 | |

| AV – Altavista wastewater lagoon, Virginia (n = 6) | min | 0.23 | 0.290 | 2.17 | 2.39 | 45 | 41.1 | 403 |

| max | 3.33 | 51.0 | 27.6 | 44.8 | 733 | 613 | 2060 | |

| mean | 1.98 | 22.8 | 14.1 | 20.0 | 378 | 286 | 1170 | |

| SD | 1.20 | 18.6 | 8.75 | 14.4 | 245 | 196 | 483 | |

| MISS -Mississippi River, Iowa (n = 13) | min | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| max | 0.43 | 6.71 | 6.18 | 14.1 | 30.1 | 0 | 16.8 | |

| mean | 0.200 | 1.89 | 1.66 | 2.59 | 9.34 | 0 | 5.03 | |

| SD | 0.13 | 2.01 | 1.66 | 3.95 | 8.78 | 0 | 5.54 | |

| IHSC - Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal, Indiana (n = 3) | min | 0.710 | 0.160 | 21.6 | 43.2 | 51.7 | 0 | 65.5 |

| max | 2.83 | 0.470 | 48.7 | 147 | 188 | 7.63 | 180 | |

| mean | 1.83 | 0.350 | 34.6 | 97.5 | 107 | 2.54 | 129 | |

| SD | 0.87 | 0.130 | 11.1 | 42.4 | 58.6 | 3.60 | 47.6 | |

| SB - Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron, Michigan (n = 8) | min | 0.100 | 0.530 | 2.02 | 2.29 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| max | 3.72 | 3.40 | 12.8 | 30.9 | 85.0 | 18.0 | 36.1 | |

| mean | 1.29 | 1.31 | 8.00 | 12.2 | 41.0 | 6.08 | 16.1 | |

| SD | 1.22 | 1.03 | 4.23 | 10.5 | 33.7 | 6.64 | 14.3 | |

| TBR - Tittabawassee River, Michigan (n = 11) | min | 0.03 | 0.380 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| max | 1.11 | 3.19 | 17.4 | 7.83 | 37.3 | 0 | 7.22 | |

| mean | 0.200 | 0.980 | 3.08 | 1.16 | 8.29 | 0 | 0.740 | |

| SD | 0.300 | 0.760 | 4.74 | 2.23 | 9.66 | 0 | 2.06 |

Aniline; o-anisidine; o/m-TD, ortho/meta-toluidine; p-TD, para-toluidine; 4-CA, 4-chloroaniline; 3-CA, 3-chloroaniline; 4-CTD, 4-chloro-o-toluidine; nicotine

The RQ values for nicotine ranged from 0 (TBR, MISS, SB) to 2060 (AV) with mean values between 0.740 (TBR) and 1170 (AV). The calculated mean and max RQ values for nicotine in AV sediment were notably >1. Ruan and Liu (2015) showed that nicotine at concentrations of 3 to 8 ng/g in sediments significantly reduced microbial diversity. Hiki et al. (2017) demonstrated that among several organic (e.g., PAHs) and inorganic pollutants (e.g., trace metals), nicotine exerted significant toxicity in sediments. Thus, further studies are needed to assess toxicity of nicotine towards aquatic organisms.

4. Conclusions

The study reports the concentrations of seven AAs and nicotine simultaneously in sediments from the United States waterbodies. AAs, especially aniline, o-anisidine and 4-chloroaniline were found ubiquitously in sediments. Aniline and 4-CA accounted for over 65% of the total AAs concentrations. Sediments from a wastewater lagoon contained the highest concentrations of AAs and nicotine suggesting that sewage discharges are a major source of these chemicals in the aquatic environment. The risk quotients calculated for the chemicals in sediments suggested potential threat to aquatic organisms, especially from nicotine contamination. However, it should be noted that samples analyzed in the study were collected over a broad time period and stored in the laboratory for several years prior to analysis. Therefore potential volatilization loss of AAs cannot be ignored. Nevertheless, our results provide baseline information on the occurrence of AAs and nicotine in aquatic ecosystems and their environmental risks.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Aromatic amines (AAs) and nicotine were measured in sediments from US waterbodies

Seven of the14 AAs analyzed were found frequently, with aniline predominating

Concentrations of AAs were in the range of 10.2 – 3140 ng/g dry wt

Highest concentrations AAs and nicotine were found in wastewater lagoon

Nicotine followed by 4-chloroaniline exhibited the highest risk quotients

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) under award number U2CES026542 (KK), the Polish-US Fulbright Commission with the Fulbright Senior Award 2021/22 grant (PL/2021/54/SR) (MU), and NIEHS award P42ES013661 (KCH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS and Polish-US Fulbright Commission.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

MU: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. SC: Methodology, Sample analysis, Manuscript review. AM: Samples, Manuscript review; KCH: Samples, Manuscript review; KK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Akyuz M, Ata S (2006). Simultaneous determination of aliphatic and aromatic amines in water and sediment samples by ion-pair extraction and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A, 1129, 88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albanhnasawi A, Yuksel E, Gurbulak E, Duyum F (2020). Fate of aromatic amines through decolorization of real textile wastewater under anoxic-aerobic membrane bioreactor. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 8, 104226 [Google Scholar]

- Anastacio Ferraz ER, Rodriguez de Oliveira GA, Palma de Oliveira D (2012). The impact of aromatic amines on the environment: risks and damage. Frontiers in Bioscience E4, 914–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew AS, Schned AR, Heaney JA, Karagas MR (2004). Bladder cancer risk and personal hair dye use. International Journal of Cancer, 109, 581–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora PK (2015). Bacterial degradation of monocyclic aromatic amines. Frontiers in Microbiology 6:820. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benotti MJ, Brownawell BJ. (2007). Distributions of pharmaceuticals in an urban estuary during both dry- and wet-weather conditions. Environmental Science & Technology, 4 (16), 5795–5802, 10.1021/es0629965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanella G, Ghanni M, Quenti G, Farris S (2015). On the origin of primary aromatic amines in food packaging materials. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 46(1), 137–143 [Google Scholar]

- ChemView (2016). Benzenamine. National aggregate production volumes. Chemical Data Reporting [online database]. Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention. United States Environmental Protection Agency Available from: https://chemview.epa.gov/chemview.

- Chinthakindi S, Kannan K (2021). Primary aromatic amines in indoor dust from 10 countries and associated human exposure. Environment international, 157, 106840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinthakindi S, Kannan K (2022a). Variability in urinary concentrations of primary aromatic amines. Science of the Total Environment, 831, 154768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinthakindi S, Kannan K (2022b). Urinary and fecal excretion of aromatic amines in pet and cats from the United States. Environment International, 163, 107208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinthakindi S, Zhu Q, Liao C, Kannan K (2022). Profiles of primary aromatic amines, nicotine and cotinine in indoor dust and associated human exposure in China. Science of the Total Environment, 806, 151395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobaradaran S, Mutke XAM, Schmidt TC, Swiderski Ph., De-la-Torre GE, Jochmann MJ. (2022). Aromatic amines contents of cigarette butts: Fresh and aged cigarette butts vs unsmoked cigarette. Chemosphere, 301, 134735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dom N, Knapen D, Benoot D, Nobels I, Blust R (2015). Aquatic multi-species acute toxicity of (chlorinated) anilines: Experimental versus predicted data. Chemosphere, 81, 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECHA (2003). Technical Guidance Document in Support of Commission Directive 93/67/EEC on Risk Assessment for New Notified Substances and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 on Risk Assessment for Existing Substances, Part II [Google Scholar]

- ECHA (2019). Aniline. Registered substance [online database]. Helsinki, Finland: European Chemicals Agency Available from: https://echa.europa.eu/fr/registration-dossier/-/registered-dossier/15333/5/2/4.

- Favaro-Perez MA, Daniel D, Padula M, do Lago CL, Grespan Bottoli CB (2021). Determination of primary aromatic amines from cooking utensils by capillary electrophoresis-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry, 362, 129902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng YH, Lin S, Zhang XF, Xu YG, Yu F, Xu J (2007). Organic contamination in river sediment and its distribution characteristics in southern Jiangsu. Journal of Agro-Environment Science, 26, 1240–1244 [Google Scholar]

- Giersing M, Egler PG, Pawlowski S, Chupp Th., Rauert C, Riedhammer C, Schwarz-Schulz B, Knaker T. (2009). Effect testing and bioaccumulation of aromatic amines in the sediment. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 9, 163–167 [Google Scholar]

- Government Canada (1994). Canadian Environmental Protection Act, Priority substances list assessment report: Aniline Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/ewh-semt/alt_formats/hecs-sesc/pdf/pubs/contaminants/psl1-lsp1/aniline/aniline-eng.pdf.

- Gracia-Lor E, Rousis NI, Zuccato E, Castiglioni S (2020). Monitoring caffeine and nicotine use in a nationwide study in Italy using wastewater-based epidemiology. Science of the Total Environment, 747, 141331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve PA, Wegman RC (1975). [Determination and occurrence of aromatic amines and their derivatives in Dutch surface waterways]. Schriftenr Ver Wasser Boden Lufthyg (46):59–80. [German] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley KW, Viet SM, Hein MJ, Carreon T, Ruder AM (2012). Exposure to o-toluidine, aniline, and nitrobenzene in a rubber chemical manufacturing plant: a retrospective exposure assessment update. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 9, 478–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D, Zhao B, Tang C, Xu Z, Zhang S, Han J. (2014). [Determination of aniline in water and fish by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry]. Se Pu 32(9):926–9. [Chinese] doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1123.2014.05025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzel F, Schmidt G (1977). [Aniline and urea derivatives in soil and water samples]. Gesund Ing 98(9):221–6. [German] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiki K, Nakajima F, Tobino T (2017). Causes of highway road dust toxicity to an estuarine amphipod: Evaluating the effects of nicotine. Chemosphere, 168, 1365–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilscherova K, Kannan K, Nakata H, Hanari N, Yamashita N, Bradley PW, McCabe JM, Taylor AB, Giesy JP (2003). Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin and dibenzofuran concentration profiles in sediments and floodplain soils of the Tittabawassee river, Michigan. Environmental Science & Technology, 37, 468–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Yang T, Liu Ch., Jin J, Gao B, Wang X, Qi M, Wei B, Zhan Y, Chen T, Wang H, Liu Y, Bai D, Rao Z, Zhan N. (2020). Distribution of aromatic amines, phenols, chlorobenzenes, and naphthalenes in the surface sediment of the Dianchi Lake, China. Frontiers in Environmental Science and Engineering, 14, 66 [Google Scholar]

- Hushon J, Clerman R, Small R, Sood S, Taylor A, Thoman D (1980). An assessment of potentially carcinogenic, energy-related contaminants in water. Prepared for the United States Department of Energy and National Cancer Institute McLean (VA), USA: MITRE Corporation; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- IARC (2010a). Working group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Some aromatic amines, organic dyes, and related exposures. Available from: IARC Press, international agency for Research on Cancer. https://www.ncbi.nml.nih.gov/books/NBK385419 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC (2010b). Some aromatic amines, organic dyes, and related exposures. IARC Monogr Eval Carc Risk Hum 99, 1–678 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC (2021). Some aromatic amines and related compounds. IARC Monogr Identif Carcinog Hazards Hum, 127:1–267 [Google Scholar]

- IHS Markit (2019). Aniline. Chemical economics handbook Available from: https://ihsmarkit.com/products/aniline-chemical-economics-handbook.html, accessed before website was updated in September 2020.

- Johnson JR, Karlsson D, Dalene M, Skarpping G (2010). Determination of aromatic amines in aqueous extracts of polyurethane foam using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Analytica Chimica Acta, 678, 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado-Sanchez B, Ballesteros E, Gallego M (2013). Comparison of microwave assisted, ultrasonic assisted and Soxhlet extractions of N-nitrosamines and aromatic amines in sewage sludge, soils and sediments. Science of the Total Environment, 463–464, 293–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käfferlein HU, Broding HC, Bünger J, Jettkant B, Koslitz S, Lehnert M, et al. (2014). Human exposure to airborne aniline and formation of methemoglobin: a contribution to occupational exposure limits. Archives of Toxicology, 88, 1419–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser JP, Feng Y, Bollag JM. (1996). Microbial metabolism of pyridine, quinoline, acridine, and their derivatives under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Microbiological Reviews 60 (3), 483–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan K, Yun SH, Ostaszewski A, McCabe JM, Mackenzie-Taylor D, Taylor AT (2008). Dioxin-like toxicity in the Saginaw River Watershed: Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, dibenzofurans, and biphenyls in sediments and floodplain soils from the Saginaw and Shiawassee rivers and Saginaw Bay, Michigan, USA. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 54, 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman DD, Blake J (1973). Microbial degradation of several acetamide, acylanilide, carbamate, toluidine and urea pesticides. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 5, 297–308 [Google Scholar]

- Kucharski D, Nałęcz-Jawecki G, Drzewicz P, Skowronek A, Mianowicz K, Strzelecka A, Giebułtowicz J (2022). The assessment of environmental risk related to the occurrence of pharmaceuticals in bottom sediments of the Odra River estuary (SW Baltic Sea). Science of The Total Environment, 828, 154446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Yin X, Zhang D, Yan D, Cui L, Zhu Z, Wen L (2018). Distribution, sources, and ecological risk assessment of quinolone antibiotics in the surface sediments from Jiaozhou Bay wetland, China. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 129, 859–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luceri F, Pieracini G, Monet G, Dolara P (1993). Primary aromatic amines from side-stream cigarette smoke are common contaminants of indoor air. Toxicological and Industrial Health 9, 405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marand A, Karlsson D, Dalene M, Skarping G (2004). Extractable organic compounds in polyurethane foam with special reference to aromatic amines and derivatives thereof. Analytica Chimica Acta, 510, 109–119 [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Hornbuckle KC (2011). Record of PCB congeners, sorbents and potential toxicity in core samples in Indiana Harbor and ship Canal. Chemosphere, 85, 542–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Norstrom K, Wang K, Hornbuckle KC (2010). Polychlorinated biphenyl in the surficial sediment of Indiana Harbor and ship Canal, Lake Michigan. Environment International, 36, 849–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Schnoebelen DJ, Hornbuckle KC (2016). Polychlorinated biphenyl congeners in sediment cores from upper Mississippi River. Chemosphere, 144, 1943–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattes TE, Ewald JM, Liang Y, Martinez A, Awad A, Richards P, Hornbuckle KC, Schnoor JL (2018). PCB dechlorination hotspots and reductive dehalogenase genes in sediments from a contaminated lagoon. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25, 16376–16388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijers A, van der Leer R (1976). The occurrence of organic micropollutants in the river Rhine and the river Maas in 1974. Water Research, 10, 597–604 [Google Scholar]

- Merkel S, Kappstein O, Sander S, Weyer J, Richter S, Pfaff K, et al. (2018). Transfer of primary aromatic amines from coloured paper napkins into four different food matrices and into cold water extracts. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part A, Chemistry, Analysis, Control, Exposure and Risk Assessment, 35, 1223–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed M, Mekala LP, Chintalapati S, Chintalapati VR (2020). New insights into aniline toxicity: aniline exposure triggers envelope stress and extracellular polymeric substance formation in Rubrivivax benzoatilytius JA1. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 385, 121571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurath GB, Dünger M, Pein FG, Ambrosius D, Schreiber O (1977). Primary and secondary amines in the human environment. Food and Cosmetics Toxicology, 15, 275–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning X-A, Liang J-Y., Li R-J, Hong Z, Wang Z-J, Chang K-L, Zhang Y-P, Yang Z-Y. (2015). Aromatic amine contents, component distributions and risk assessment in sludge from 10 textile-dyeing plants. Chemosphere, 134, 367–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2009). The 2007 OECD list of high production volume chemicals. OECD Environment, Health and Safety Publications Series on Testing and Assessment No. 112. ENV/JM/MONO(2009)40. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Available from: http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=ENV/JM/MONO(2009)40&doclanguage=en.

- Pahade P, Bose D, Peris-Vicente J, Goberna-Bravo MA, Chiba JA, Romero JE, Carda-Broch S, Durgbanshi A (2021). Screening of some banned aromatic amines in textile products from Indian bandhani and gamthi fabric and in human sweat using micellar liquid chromatography. Microchemical Journal, 165, 106134 [Google Scholar]

- Peverly A, O’Sullivan C, Liu L-Y., Venier M, Martinez A, Hornbuckle KC, Hites RA. (2015). Chicago’s Sanitary and Ship Canal sediment: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls, brominated flame retardants, and organophosphate esters. Chemosphere, 134, 380–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett L, Aldous A, Benson V, Brandon Y, Briere B, Dee T, et al. (2014). Volatile organic compounds - understanding the risks to drinking water. National Centre for Environmental Toxicology. Report DWI9611.04, October 2014. Drinking Water Inspectorate Available from: http://dwi.defra.gov.uk/research/completed-research/reports/DWI70-2-292.pdf.

- Ross MM, Gago-Dominguez M, Aben KKH, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Kampman E, Vermeulen SH, et al. (2012). Personal hair dye use and the risk of bladder cancer: a case-control study from the Netherlands. Cancer Causes Control, 23, 1139–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan A, Liu Ch. (2015). Analysis of effect of nicotine on microbial community structure in sediment using PCR-DGGE fingerprinting. Water Science and Engineering, 8, 309–314 [Google Scholar]

- Saktrakulka P, Li X, Martinez A, Lehmler H-J., Hornbucle KC. (2022). Hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls are emerging Legacy pollutants in contaminated Sediments. Environmental Science and Technology, 10.1021/acs.est.1c04780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAP (2005). Sampling and Analysis Plan. Roanoke River Basin PCB TMDL Development (Virginia). Tetra Tech, Inc. for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency – Region III Virginia Department of Environmental Quality U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [Google Scholar]

- Schubert J, Kappenstein O, Luch A, Schulz TZ (2011). Analysis of primary aromatic amines in the mainstream waterpipe smoke using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A, 1218, 5628–5637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckar JO, Stavanja MS, Paul R, Harp PR, Yongsheng Y, Garner Ch.D., Doi J. (2008). Environmental fate and effects of nicotine released during cigarette production. Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry 27(7),1505–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senta I, Gracia-Lor E, Borsotti A, Zuccato E, Castiglioni S (2015). Wastewater analysis to monitor use of caffeine and nicotine and evaluation of their metabolites as biomarkers for population size assessment. Water Research, 74, 23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford WM, Keith LH (1976). Frequency of organic compounds identified in water. Report EPA-600/4–76-062 Athens (GA), USA: Environmental Research Laboratory, Analytical Chemistry Branch, United States Environmental Protection Agency; pp. 9, 58, 59 [Google Scholar]

- Stabbert R, Schaffer KH, Biefel C, Rustemeir K (2003). Analysis of aromatic amines in cigarette smoke. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 17, 2125–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turesky RJ, Freeman JP, Holand RD, Nestorick DM, Miller DW, Ratnasinghe DL, et al. (2003). Identification of aminobiphenyl derivatives in commercial hair dyes. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 16, 1162–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNEP (2005). Initial Assessment Report For SIAM Washington, DC, 18–21 October 2005 [Google Scholar]

- US EPA (1986). Michigan dioxin studies. Dow chemical wastewater characterization study. Tittabawassee River sediment and native fish Report by the US EPA, Region V., Westlake, OH [Google Scholar]

- US EPA (2007). Appendix F: The Risk Quotient Method and Levels of Concern August 29, 2007 https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/endanger/litstatus/effects/appendix_f_rq_method_and_locs.pdf [Google Scholar]

- US EPA (2020). EPA: high production volume list. United States Environmental Protection Agency Available from: https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/chemical_lists/EPAHPV#:~:text=Chemicals%20considered%20to%20be%20HPV,one%20million%20pounds%20per%20year.&text=However%2C%20EPA%20will%20mandate%20testing,Substance%20Control%20Act%20(TSCA), accessed 4 March 2021.

- VADEQ (1999). DEQ Investigations at BGF Industries, 401 Amherst Avenue Altavista, Virginia 24517. Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Environmental Science Division, Water Quality Assessment and Planning Richmond, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wel JHP, Gracia-Lor E, van Nuijs ALN, Kinyua J, Salvatore S, Castiglioni S, Bramness JG, Covaci A, Van Hal G (2016). Investigation of agreement between wastewater-based epidemiology and survey data on alcohol and nicotine use in a community. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162, 170–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez JA, Rial D (2014). Inhibition of selected bacterial growth by three hydrocarbons: Mathematical evaluation of toxicity using a toxicodynamic equation. Chemosphere, 112, 56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verovest T, Heath D, Heath E (2022). Occurrence, fate and determination of tobacco (nicotine) and alcohol (ethanol) residues in waste- and environmental waters. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 34, e00164 [Google Scholar]

- Wang SN, Huang HY, Xie KB, Xu P (2012). Identification of nicotine biotransformation intermediates by Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain S33 suggests a novel nicotine degradation pathway. Applied Microbiology & Biotechnology, 95(6), 1567e1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber EJ, Colon D, Baughman GL (2001). Sediment-associated reactions of aromatic amines. 1. Elucidation of sorption mechanisms. Environmental Science & Technology, 35, 2470–2475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2003). 4-chloroaniline: Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 48. World Health Organization https://www.who.int/ipcs/publications/cicad/en/ccad48.pdf?ua=1

- WHO (2021). WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2021: addressing new and emerging products Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ISBN 978–92-4–003209-5 https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/tobacco-control/global-tobacco-report-2021

- Yun HS, Addink R, McCabe JM, Ostaszewski A, Mackenzie D, Taylor AB, Kannan K (2008). Polybrominated diphenyl ethers and polybrominated biphenyls in sediment and floodplain soils of the Saginaw river watershed, Michigan, USA. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 55, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Q, Eaglesham G, Tscharke BJ, O’Brien JW, Li J, Thompson J, Shimko KM, Reeks T, Geber C, Thomas KV, Thai Ph.K. (2020). Determination of anabasine, anatabine, and nicotine biomarkers in wastewater by enhanced direct injection LC-MS/MS and evaluation of their in-sewer stability. Science of the Total Environment, 743, 140551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.