Abstract

Background

Stunting increases morbidity and mortality, hindering mental development and influencing cognitive capacity of children. This study aimed to examine the trends and determinants of stunting from infancy to middle adolescence in four countries: Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam.

Methods

A 15-year longitudinal data on the trends of stunting were obtained from the Young Lives cohort study. The study includes 38,361 observations from 4 countries. A generalized mixed-effects model was adopted to estimate the determinant of stunting.

Results

The patterns of stunting in children from aged 1 to 15 years have declined from an estimated 30% in 2002 to 20% in 2016. Stunting prevalence varied among four low- and middle-income countries with children in Ethiopia, India, and Peru being more stunted compared to children in Vietnam. The highest stunted was recorded in India and the lowest was recorded in Vietnam. In all four countries, the highest prevalence of severe stunting was observed in 2002 and moderate stunting was observed in 2006. Parents’ education level played a significance role in determining a child stunting. Children of uneducated parents were shown to be at a higher risk of stunting.

Conclusion

Disparities of stunting were observed between- and within-country of four low- and middle-income with the highest prevalence recorded in low-income country. Child stunting is caused by factors related to child’s age, household wealth, household size, the mother’s and father’s education level, residence area and access to save drinking water.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13690-023-01090-7.

Keywords: Longitudinal data, Prevalence, Random effect, Stunting

Background

The Sustainable Development Goals and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development both call for reducing disparities in health and leaving no one behind [1, 2]. Health disparities are linked to social disparities in nutrition via complex pathways that include policies addressing health and nutrition; the quality and quantity of food available and consumed; access to and affordability of nutritious foods of high quality; and individuals’ and populations’ living conditions and circumstances. To effectively plan, create, and implement public health nutrition policies, strategies, and programs, the evidence base on health disparities in nutrition must be expanded [3].

Stunting, wasting, and underweight have often been used to measure the prevalence of under-nutrition in children. Stunting is the delayed growth and development that children endure as a result of poor nutrition, frequent infection, and insufficient psychosocial stimulation [4]. Children are considered stunted if their height-for-age is more than two standard deviations below the WHO Child Growth Standards median [5, 6]. Stunting raises morbidity and mortality risks in children, and also hinders mental development, and influence the cognitive ability of children [5, 7–9]. It is a physical sign of persistent childhood malnutrition that is clearly visible and quantified [6].

In recent decades, there has been significant success in lowering child stunting prevalence [3, 6, 9, 10]. However, between-country disparities in the prevalence of stunting reduction are widely observed. Africa and Asia suffer the greatest burden of a child stunting [11]. Stunting prevalence, for example, has decreased by two-thirds in upper-middle-income nations since 2000, whereas it remains high in low and lower-middle-income nations [10, 12, 13].

The Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations have identified stunting, along with other nutrition indicators, as the primary focal areas for eradicating global malnutrition [14]. The disparity in worldwide progress in child stunting provides an appropriate scenario for testing the hypothesis in child stunting trends. In this regard, it is critical to investigate the major causes and trends of stunting so that individual nations may learn what works and develop customized policies and initiatives.

The objective of this study was, therefore, to investigate the patterns and determinants of stunting from infancy to middle adolescence in four countries: Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam.

Materials and methods

Data sources and settings

Longitudinal data on the prevalence of stunting were obtained from the Young Lives cohort study. The Young Lives study is a 15-year longitudinal study that looks at the changing nature of childhood poverty in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. The Young Lives cohort study thus collects data from these countries at both child-level and household-level to understand the causal effect of childhood poverty. Children from poor household were purposively over-sampled [15].

For sample selection, a multistage sampling approach was adopted, with the first stage including the selection of 20 sentinel stations from each nation. Following the selection of 20 sentinel sites, households with children, on average, one-year age groups were chosen at random. Finally, 100 households with, on average, a one-year-old child were selected randomly from each sentinel site [16]. A longitudinal anthropometric measurements of children were collected at the years 2002, 2006, 2009, 2013, and 2016 [17]. The sample and sampling procedures adopted in the Young Lives cohort study were addressed in detail elsewhere [18–23].

The study variables

The stunting status of children was a categorical outcome variable. It was measured longitudinally on five measurement occasions from 2002 to 2016. Children with height-for-age z-scores (HAZ) greater than or equal to -2 were categorized as not stunted, moderately stunted if their HAZ were between − 3 and − 2, and severely stunted if their HAZ were less than − 3 [3, 15, 24, 25]. The Independent variables considered as determinants of stunting were gender, age, residence area (rural and urban), father’s level of education, father’s age, mother’s level of education, mother’s age, household size, wealth index, and access to safe drinking water. In the Young Lives study, the wealth index is the major measure of households’ socioeconomic status [19]. It is the average of housing quality, access to services, and consumer durable ownership. This average yields a number between 0 and 1, with a higher wealth index reflecting a better socioeconomic status [15].

Ethical approval

In this study, the secondary data from the UK archival sources were used. The UK data are publicly available and can be accessed from this link http://www.younglives.org.uk/ by contacting the UK program team using personal accounts and providing the reason for the request. After reviewing the abstract of our study, we were given permission to use the data.

Data analysis methods

Generalized linear mixed-effect model (GLMM)

In a current longitudinal data, individuals in the study are followed over a period of time and, for each individual, data were collected at five time points from aged 1 to 15 years. One of the mixed-effects classes commonly used for analyzing longitudinal binary data is the generalized linear mixed model. Consider a binary longitudinal outcome of stunting ( ,

,  ) taking only two possible values (not stunted coded as 0 and stunted coded as 1). In this regard, a general GLMM for binary longitudinal outcome can be written as [26]

) taking only two possible values (not stunted coded as 0 and stunted coded as 1). In this regard, a general GLMM for binary longitudinal outcome can be written as [26]

|

where  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are vectors containing fixed and random covariates, respectively,

are vectors containing fixed and random covariates, respectively,  is a vector of fixed effect and D is a covariance matrix. A GLMM is typically based on the likelihood method of statistical inference [26, 27].

is a vector of fixed effect and D is a covariance matrix. A GLMM is typically based on the likelihood method of statistical inference [26, 27].

The fixed variables ( ) included in a GLMM are: gender, age, residence area, father’s level of education, father’s age, mother’s level of education, mother’s age, household size, wealth index, and access to safe drinking water. Children (Children Id) were considered as random variable (

) included in a GLMM are: gender, age, residence area, father’s level of education, father’s age, mother’s level of education, mother’s age, household size, wealth index, and access to safe drinking water. Children (Children Id) were considered as random variable ( ) in this study. The outcome variable (stunting) was reclassified into two categories: stunted and not stunted, with moderately stunted and severely stunted being merged into the term stunted. Hence, the data were analyzed by using a binary longitudinal outcome in GLMM.

) in this study. The outcome variable (stunting) was reclassified into two categories: stunted and not stunted, with moderately stunted and severely stunted being merged into the term stunted. Hence, the data were analyzed by using a binary longitudinal outcome in GLMM.

The data were analyzed using Statistical Analysis Systems SAS 9.4 version. Modeling categorical response variables with random effects is a major use of the PROC GLIMMIX in SAS statistical procedure. The PROC GLIMMIX provides the capability to model binary (not-stunted/stunted, 0/1) outcome, including random effects and correlated errors.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

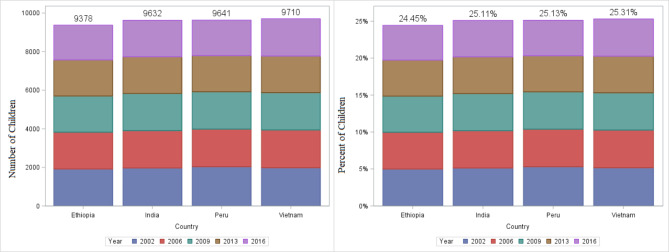

Table 1 shows the background characteristics of the children, their parents, and the countries from which the children were chosen. In all, 38,361 observations were available from 4 countries. Of these observations, 9378, 9632, 9641, and 9710 were conducted in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam, respectively. The percentage of observations (children chosen) from each country was nearly identical, the minimum was 9378(24.45%) from Ethiopia and the maximum was 9710(25.31%) from Vietnam (Fig. 1). The majority of the children in the sample were from rural areas, and more than half of them were males. In 2002, the majority of children’s mothers (40.3%) were uneducated. However, the percentage of uneducated mothers has decreased over time from 40.3% to 2002 to 24.6% in 2016. Similarly, the percentage of uneducated fathers fell from 32.6% to 2002 to 12.6% in 2016 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Background Characteristics of children in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam

| Characteristics | Year of survey | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2006 | 2009 | 2013 | 2016 | |||

| Child’s sex | Male | n | 4091 | 4040 | 3990 | 3935 | 3900 |

| % | 51.8 | 52.1 | 52.0 | 52.1 | 52.1 | ||

| Female | n | 3814 | 3711 | 3682 | 3619 | 3579 | |

| % | 48.2 | 47.9 | 48.0 | 47.9 | 47.9 | ||

| Area of residence | Urban | n | 2976 | 2925 | 2940 | 3015 | 3044 |

| % | 37.6 | 37.7 | 38.3 | 39.9 | 40.7 | ||

| Rural | n | 4929 | 4826 | 4715 | 4539 | 4434 | |

| % | 62.4 | 62.3 | 61.5 | 60.1 | 59.3 | ||

| Access to safe drinking water | No | n | 3999 | 3340 | 2771 | 2569 | 2198 |

| % | 50.6 | 43.1 | 36.2 | 34.0 | 29.5 | ||

| Yes | n | 3901 | 4411 | 4892 | 4981 | 5257 | |

| % | 49.4 | 56.9 | 63.8 | 66.0 | 70.5 | ||

| Father’s education level | Uneducated | n | 2295 | 1464 | 1232 | 870 | 809 |

| % | 32.6 | 21.0 | 18.4 | 13.2 | 12.6 | ||

| Primary school | n | 2462 | 3013 | 2998 | 3010 | 2713 | |

| % | 34.9 | 43.2 | 44.7 | 45.8 | 42.3 | ||

| Secondary school | n | 1749 | 1765 | 1734 | 1750 | 1849 | |

| % | 24.8 | 25.3 | 25.9 | 26.6 | 28.8 | ||

| Diploma and above | n | 521 | 553 | 547 | 617 | 676 | |

| % | 7.4 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 9.4 | 10.5 | ||

| Adult and Religious education | n | 21 | 176 | 189 | 324 | 364 | |

| % | 0.3 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 4.9 | 5.7 | ||

| Mother’s education level | Uneducated | n | 3115 | 2357 | 2004 | 1844 | 1757 |

| % | 40.3 | 31.1 | 27.2 | 25.4 | 24.6 | ||

| Primary school | n | 2660 | 3113 | 3212 | 3133 | 2924 | |

| % | 34.4 | 41.1 | 43.6 | 43.1 | 41.0 | ||

| Secondary school | n | 1522 | 1524 | 1510 | 1538 | 1628 | |

| % | 19.7 | 20.1 | 20.5 | 21.2 | 22.8 | ||

| Diploma and above | n | 414 | 412 | 432 | 462 | 525 | |

| % | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 6.4 | 7.4 | ||

| Adult and Religious education | n | 19 | 163 | 215 | 287 | 300 | |

| % | 0.2 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 4.2 | ||

| The four Low- and middle-income countries | Ethiopia | n | 1917 | 1908 | 1877 | 1871 | 1805 |

| % | 24.3 | 24.6 | 24.5 | 24.8 | 24.1 | ||

| India | n | 1970 | 1937 | 1924 | 1907 | 1894 | |

| % | 24.9 | 25.0 | 25.1 | 25.2 | 25.3 | ||

| Peru | n | 2035 | 1950 | 1937 | 1876 | 1843 | |

| % | 25.7 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 24.8 | 24.6 | ||

| Vietnam | n | 1983 | 1956 | 1934 | 1900 | 1937 | |

| % | 25.1 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 25.9 | ||

Fig. 1.

The number and percent of children included in the study from Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam

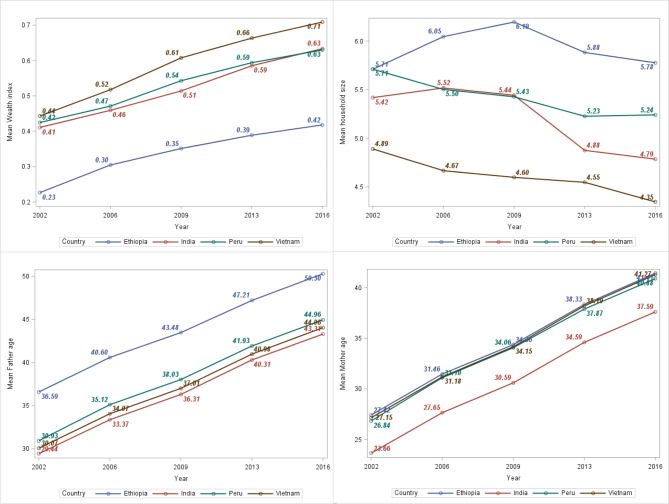

Figure 2 depicts the graphical exploration of the characteristics of numeric variables such as father’s age, mother’s age, wealth index, and household size. From Fig. 2, it can be seen that Vietnam had the highest wealth index and the lowest household size throughout all the study periods. In contrast, Ethiopia had the lowest wealth index and the largest household size from 2002 to 2016. In all study periods from 2002 to 2016, the parents (father and mother) of Indian children had the lowest average ages, while the parents of Ethiopian children had the highest average ages.

Fig. 2.

The mean trends of father’s age, mother’s age, wealth index, and household size in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam

Height-for-age

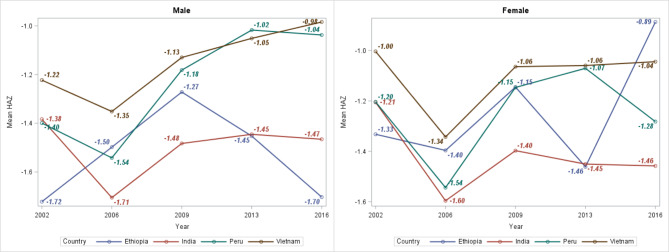

From 2002 to 2016, height-for-age z-score (HAZ) values were computed for each child in four study countries to assess the trends and prevalence of stunting. Figure 3 shows trends in the mean HAZ of children in the four study countries. The minimum (-1.72) and maximum (-0.98) estimated mean HAZ were recorded in Ethiopian males and females, respectively. Children in Vietnam had approximately the highest mean HAZ in both genders, except in 2016, where Ethiopian females had the highest estimated mean HAZ (-0.89).

Fig. 3.

Mean height-for-age z-score of children in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam

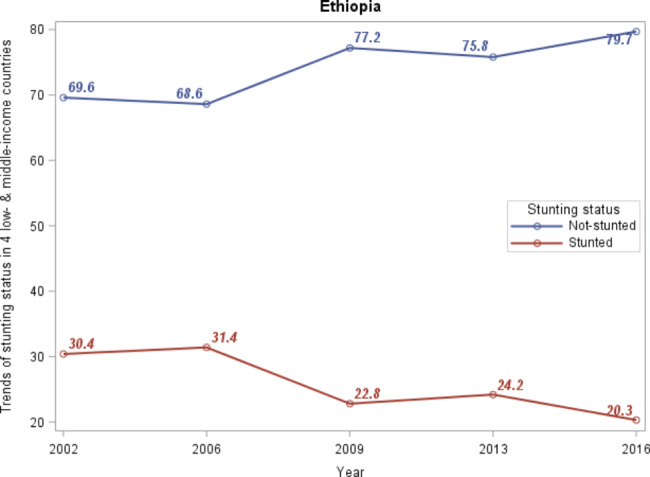

Between-country patterns of stunting prevalence from 2002 to 2016

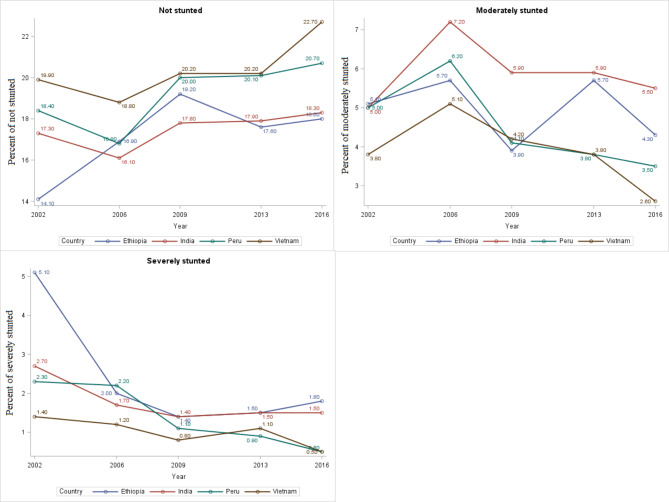

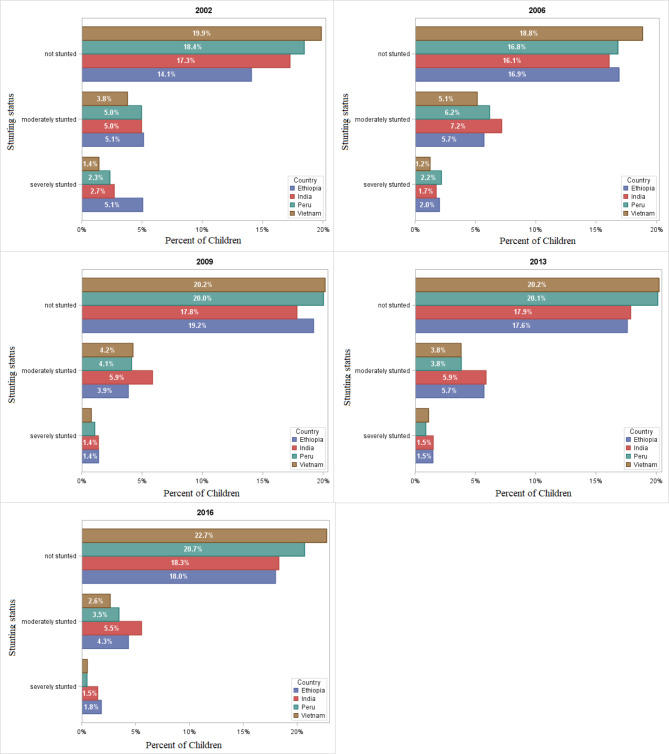

The within- and between-country status of stunting prevalence was presented in Table 2; Fig. 4, respectively. From the visual inspection of the between-country trends of stunting prevalence displayed in Fig. 4, the trends of stunting in children from 2002 to 2016 have declined from an estimated 30% in 2002 to 20% in 2016. In fact, the four countries have observed reductions in stunting prevalence. However, the greatest decline occurred in Vietnam to 2.6% in moderately stunted and to 0.5% in severely stunted (Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Within-country (Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam) prevalence of stunting status

| Country | Stunting | Prevalence, n(%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2006 | 2009 | 2013 | 2016 | |||

| Ethiopia | Not stunted | n | 1112 | 1310 | 1474 | 1329 | 1345 |

| % | 58 | 68.7 | 78.5 | 71 | 74.5 | ||

| Moderately stunted | n | 405 | 442 | 296 | 431 | 324 | |

| % | 21.1 | 23.2 | 15.8 | 23 | 18 | ||

| Severely stunted | n | 400 | 156 | 107 | 111 | 136 | |

| % | 20.9 | 8.2 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 7.5 | ||

| India | Not stunted | n | 1365 | 1246 | 1368 | 1350 | 1368 |

| % | 69.3 | 64.3 | 71.1 | 70.8 | 72.2 | ||

| Moderately stunted | n | 392 | 556 | 450 | 444 | 415 | |

| % | 19.9 | 28.7 | 23.4 | 23.3 | 21.9 | ||

| Severely stunted | n | 213 | 135 | 106 | 113 | 111 | |

| % | 10.8 | 7 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 5.9 | ||

| Peru | Not stunted | n | 1458 | 1303 | 1537 | 1520 | 1547 |

| % | 71.6 | 66.8 | 79.3 | 81 | 83.9 | ||

| Moderately stunted | n | 392 | 478 | 317 | 289 | 259 | |

| % | 19.3 | 24.5 | 16.4 | 15.4 | 14.1 | ||

| Severely stunted | n | 185 | 169 | 83 | 67 | 37 | |

| % | 9.1 | 8.7 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 2 | ||

| Vietnam | Not stunted | n | 1570 | 1461 | 1547 | 1528 | 1700 |

| % | 79.2% | 74.7 | 80 | 80.4 | 87.8 | ||

| Moderately stunted | n | 300 | 399 | 326 | 288 | 198 | |

| % | 15.1 | 20.4 | 16.9 | 15.2 | 10.2 | ||

| Severely stunted | n | 113 | 96 | 61 | 84 | 39 | |

| % | 5.7 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 2 | ||

Fig. 4.

Trends of stunting in four low- and middle-income countries

Fig. 5.

Between-country trends of stunting status among four low- and middle-income countries from 2002 to 2016

From the results of within-county prevalence of stunting status presented in Table 2, for all four countries, the highest prevalence of severe stunting was observed in 2002 and moderate stunting was observed in 2006. For instance, the prevalence of severe stunting in 2002 was 20.9%, 10.8%, 9.1%, and 5.7% in Ethiopia [23], India, Peru, and Vietnam, respectively. On the other hand, the highest prevalence of moderate stunting observed in 2006 was 23.2%, 28.7%, 24.5%, and 20.4% in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam, respectively (Table 2). Accordingly, the lowest prevalence of severe stunting was observed in 2009 for both Ethiopia and India (5.7% and 5.5%, respectively) and in 2016 for Peru and Vietnam (both 2%).

Figures 6 and 5 depict the prevalence and patterns of stunting status from 2002 to 2016. The percentages of between-country prevalence were derived using the sum of children numbers affected in each country divided by the total children in four countries. The percentages of within-country prevalence, on the other hand, were calculated by dividing the total number of children exposed in each country by the total number of children in the corresponding country.

Fig. 6.

Between-country prevalence of stunting among four low- and middle-income countries from 2002 to 2016

Results of generalized linear mixed-effects model

Stunting determinants were chosen by first including all considered factors into the model and then evaluating their significance. Subsequently, those factors that were statistically significant in determining a child stunting were considered and interpreted. In this regard, factors such as a child’s country, a child’s age, household size, wealth index, child’s sex, residence area, father’s education level, and mother’s education level were statistically significant determinants of stunting. However, father’s age and mother’s age were not statistically significant determinants of stunting. The significance tests of variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The fixed effects significance tests in determinants of stunting

| Effect | Num DF | Den DF | F Value | Pr > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 3 | 32,616 | 30.64 | < 0.0001 |

| Child’s age | 4 | 32,616 | 46.21 | < 0.0001 |

| Mother’s age | 2 | 32,616 | 0.72 | 0.4859 |

| Father’s age | 2 | 32,616 | 0.07 | 0.9349 |

| Household size | 1 | 32,616 | 8.59 | 0.0034 |

| Wealth index | 2 | 32,616 | 52.11 | < 0.0001 |

| Child’s sex | 1 | 32,616 | 36.00 | < 0.0001 |

| Residence area | 1 | 32,616 | 50.83 | < 0.0001 |

| Father’s education level | 4 | 32,616 | 11.59 | < 0.0001 |

| Mother’s education level | 4 | 32,616 | 25.16 | < 0.0001 |

Table 4 depicts the estimated odds ratios of factors related to parents’ and children’s characteristics in determining a child’s stunting. The findings of the study revealed that there were disparities in stunting prevalence in four low- and middle-income countries; Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. Compared to children in Vietnam, children in Ethiopia, India, and Peru were more stunted (Ethiopia: OR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.21–1.93, p = 0.0003, India: OR = 2.33, 95% CI: 1.89–2.88, p < 0.0001, Peru: OR = 2.57, 95% CI: 2.04–3.24, p < 0.0001). In terms of ages, children were more stunted at five years old (OR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.14–1.42, p < 0.0001) and less stunted at eight (OR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.53–0.69, p < 0.0001), twelve (OR = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.65–0.89, p = 0.0006), and fifteen (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.46–0.66, p < 0.0001) years old.

Table 4.

The fixed effects factors related to parents’ and children’s characteristics

| Effect | Estimate | SE | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country (ref. = Vietnam) | |||||

| Ethiopia | 0.4261 | 0.1183 | 1.531 | 1.214–1.931 | 0.0003 |

| India | 0.8468 | 0.1069 | 2.332 | 1.891–2.876 | < 0.0001 |

| Peru | 0.9445 | 0.1181 | 2.572 | 2.04–3.241 | < 0.0001 |

| Child’s age in year (ref. = age one) | |||||

| Age five | 0.2384 | 0.0554 | 1.269 | 1.139–1.415 | < 0.0001 |

| Age eight | -0.503 | 0.0661 | 0.605 | 0.531–0.688 | < 0.0001 |

| Age twelve | -0.276 | 0.0799 | 0.759 | 0.649–0.887 | 0.0006 |

| Age fifteen | -0.591 | 0.0915 | 0.554 | 0.463–0.663 | < 0.0001 |

| Mother’s age in year (ref. =≤29 age) | |||||

| 30≤ age ≤36 | 0.07984 | 0.0665 | 1.083 | 0.951–1.234 | 0.2301 |

| ≥37 age | 0.09663 | 0.1016 | 1.101 | 0.903–1.344 | 0.3413 |

| Father’s age in year (ref. = ≤34 age) | |||||

| 35≤ age ≤41 | 0.00028 | 0.0654 | 1 | 0.88–1.137 | 0.9966 |

| > 41 age | 0.02459 | 0.0969 | 1.025 | 0.848–1.239 | 0.7996 |

| Household size in number (ref.=≤5 household size) | |||||

| >5 household size | 0.1478 | 0.0504 | 1.159 | 1.05–1.28 | 0.0034 |

| Wealth index (ref. = low) | |||||

| Medium | -0.3833 | 0.0575 | 0.682 | 0.609–0.763 | < 0.0001 |

| High | -0.8559 | 0.0839 | 0.425 | 0.36–0.501 | < 0.0001 |

| Child’s sex (ref. = Boy) | |||||

| Girl | -0.4372 | 0.0729 | 0.646 | 0.56–0.745 | < 0.0001 |

| Residence area (ref. = Urban) | |||||

| Rural | 0.5994 | 0.0841 | 1.821 | 1.544–2.147 | < 0.0001 |

| Father education level (ref. = uneducated) | |||||

| Adult and religious education | 0.1172 | 0.1465 | 1.124 | 0.844–1.498 | 0.4235 |

| Primary school | -0.0896 | 0.0781 | 0.914 | 0.785–1.065 | 0.2512 |

| Secondary school | -0.6365 | 0.1092 | 0.529 | 0.427–0.655 | < 0.0001 |

| Diploma and above | -0.6942 | 0.1718 | 0.499 | 0.357–0.699 | < 0.0001 |

| Mother education level (ref. = uneducated) | |||||

| Adult and religious education | -0.0921 | 0.1661 | 0.912 | 0.659–1.263 | 0.5793 |

| Primary school | -0.3241 | 0.0784 | 0.723 | 0.62–0.843 | < 0.0001 |

| Secondary school | -1.0428 | 0.1206 | 0.352 | 0.278-0.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Diploma and above | -1.75 | 0.2174 | 0.174 | 0.113–0.266 | < 0.0001 |

Girls and boys are not equally likely to be stunted in these four low- and middle-income countries, but in these countries, stunting afflicts fewer girls (OR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.56–0.75, p < 0.0001) than boys. This suggests that girls had a 35% lesser odds of stunting compared to boys. Children in rural households were more than 1.82 times (OR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.54–2.15, p < 0.0001) as likely to be stunted as children in urban households.

Regarding parents-related factors, children from educated parents (mother and father), children from high wealth index households, and children from low household sizes were associated with lower odds of stunting. For instance, children born to mothers with a primary school, secondary school, and diploma and above education level had 0.72 (95% CI: 0.62–0.84, p < 0.0001), 0.35 (95% CI: 0.28–0.4, p < 0.0001), and 0.17 (95% CI: 0.11–0.27, p < 0.0001) times less likely to be stunted than children from uneducated mothers, respectively. Similarly, children born to fathers with a secondary school, and diploma and above education level had 0.53 (95% CI: 0.43–0.66, p < 0.0001), 0.499 (95% CI: 0.357–0.699, p < 0.0001), and 0.17 (95% CI: 0.11–0.27) times less likely to be stunted than children from uneducated mothers, respectively. Children from the medium and high wealth index households were less than 0.68 (95% CI: 0.61–0.76, p < 0.0001) and 0.43 (95% CI: 0.36–0.50, p < 0.0001) times as likely to be stunted as children from the low wealth index households, respectively.

Discussion

This study covered four low- and middle-income countries of the Young Lives study area; namely Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. The Young Lives data are well-suited for studying the longitudinal dynamics of child-related variables as well as the influence of children’s early-life situations on their later outcomes. As a result, the data derived from the Young Lives study and used in this study contained both country-specific and statistically sound information.

The current study covered only four low- and middle-income countries and reported on the patterns, prevalence, and determinants of stunting from 2002 to 2016. Countries are expected to identify their contributions and set their own objectives in order for the global stunting target to be met. The ability to translate the global aim into individual national targets is reliant on nutrition profiles, risk factor trends, demographic changes and executing nutrition policies, and the level of health system development [11]. Therefore, the findings of this study insight into the stunting prevalence in these countries that are used to show the countries’ contribution to the global stunting target.

In this study, the within- and between-country status of stunting prevalence was examined. The trends of stunting prevalence among children aged 1 to 15 years in four low- and middle-income countries were declined from 30 to 20% (Fig. 4). According to Onis et al. [28] study on the prevalence and trends of stunting among preschool children in developing countries, stunting prevalence declined from 47% to 1980 to 33% in 2000 (by 40 million). Despite the overall decrease in stunting, progress was heterogeneous across countries. The highest moderate stunted was recorded in India during all the study periods, whereas Vietnam had the lowest prevalence except in 2009. Ethiopia recorded the highest percentage of severe stunting (5.1%) in 2002 and the lowest percentage of moderate stunting (3.9%) in 2009 compared with that of India, Peru, and Vietnam. This result is similar to the findings of Astatkie [23], who utilized the same dataset to investigate dynamics of stunting in Ethiopia using both younger and older cohort data. He noted that the highest cross-sectional prevalence of severe stunting in younger children was observed in Round 1 (2002).

A generalized linear mixed-effects model was adopted to estimate the determinant of stunting from 2002 to 2016. The basic model contained the factors country, child’s age, mother’s age, father’s age, household size, wealth index, child’s sex, residence area, father’s education level, and mother’s education level as fixed effects and children as a random effect.

Stunting prevalence varied among four low- and middle-income countries with children in Ethiopia, India, and Peru being more stunted compared to children in Vietnam. The study identified that a child’s age was a significant factor in determining a child stunting. At ages 8, 12, and 15 years, children were less likely to be stunted than at age 1 year. However, Children were more likely to be stunted at five years of age than at one year of age. This result is consistent with the previous studies [23, 29–31].

The study showed that girls were at a lesser risk for stunting than boys. This was confirmed in several previous studies [23, 29, 32–37]. In contrast, previous studies found no significant variation in stunting based on gender [38, 39]. Furthermore, the findings indicated that the mother’s education level and the father’s education level also played a role in determining child stunting. One likely reason is that more education implies literacy, which allows parents to obtain more health information. Better feeding patterns and nutrition status in Ugandan children have been linked to maternal literacy and education [40]. Children of uneducated parents were shown to be at a higher risk of stunting. This result is consistent with earlier findings [31, 33, 34, 41, 42]. Conversely, a study in Uganda noted that no significant effect of education level on stunting [38], while other studies found an inverse relationship between education level and stunting [43, 44]. Berhane et al. reported that more educated mothers provided a more diverse diet for their children. Furthermore, greater education opens the door to a higher income, enhancing household wealth [32].

This study noted that children of households with a medium and high wealth index had a much lower risk for stunting than low wealth index households. Several previous studies found that children of a rich household were related to a lower risk of stunting [33, 34, 42, 45]. A study of Ethiopian children demonstrated that low socioeconomic status may predispose children to stunting [46]. Residence area is another environmental factor that impacts food security and thus could changes child stunting. Children in rural households were also found to be at a higher risk of stunting as compared to urban households. Furthermore, the study showed that households of several sizes living together increased the risk of stunting in those children. It is evident that the food available must be distributed to all household members, which raises the risk of under-nutrition in less resourceful households. Living many household sizes together puts a greater strain on caregivers and household resources as compared to a singleton [37].

Several previous studies were used cross-sectional data to evaluate the nutrition status of children [47–50]. It is rational that cross-sectional studies are restricted in quantifying individual changes over time. One of the strength of this study is that it utilized longitudinal data to examine the prevalence of stunting over time from 2002 to 2016 in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam. Longitudinal studies are more successful and have higher statistical power than cross-sectional studies in evaluating changes over time [51, 52]. There are also some limitations to the present analyses. This study was limited to four low- and middle-income countries; hence, the results present in this study may not reflect all children in low- and middle-income countries. Another limitation of the study is that the Young Lives study employed a purposive sampling technique to select sentinel sites from which children under the study can be chosen. This may limit to generalize the study results. Despite these limitations, the current findings provide a good foundation for monitoring stunting levels and changes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the pattern of stunting among children aged 1 to 15 years has reduced in four low- and middle-income countries. Despite the overall decrease, progress of decrement was heterogeneous across countries. The highest stunted was recorded in India during all the study periods, and approximately the lower was recorded in Vietnam. Ethiopia recorded the highest percentage of severe stunting in 2002 and the lowest percentage of moderate stunting in 2009. Child stunting is caused by factors associated with child’s age, household wealth, household size, the mother’s and father’s education level, residence area and access to save drinking water. Policies and interventions should focus on parents’ education and access to save drinking water, as these are the most powerful factors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Young Lives study for giving us access to the data files. Young Lives is a 15-year study of the changing nature of childhood poverty in low- and middle-income countries.

Author contributions

SKW analyzed and drafted this manuscript. TZ designed, advised and supervised the start, the analysis, and the write-up of the manuscript. KL and YHF prepared and arranged data for analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The Young Lives data are publicly available and can be accessed from http://www.younglives.org.uk/.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.United Nations Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Sustainable Development Goals [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 24]. Available from: http://archive.unu.edu/unupress/food/V182e/ch05.htm.

- 2.United Nations Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [Internet]. [cited 2022 Dec 24]. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld.

- 3.World Health Organization. Reducing stunting in children: equity considerations for achieving the Global Nutrition Targets 2025. 2018.

- 4.UNICEF. State of the World’s Children Statistical Report. 2015.

- 5.World Health Organization. utrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) country profile indicators: interpretation guide. 2019.

- 6.Vaivada T, Akseer N, Akseer S, Somaskandan A, Stefopulos M, Bhutta ZA. Stunting in childhood: an overview of global burden, trends, determinants, and drivers of decline. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112:777S–91. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Improving Child Nutrition. The Achievable Imperative for Global Progress. 2013.

- 8.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoddinott J, Alderman H, Behrman JR, Haddad L, Horton S. The economic rationale for investing in stunting reduction. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9(S2):69–82. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balla S, Goli S, Vedantam S, Rammohan A. Progress in child stunting across the world from 1990 to 2015: testing the global convergence hypothesis. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(17):5598–607. doi: 10.1017/S136898002100375X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onis M, De, Branca F. Childhood stunting : a global perspective. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12:12–26. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: key findings of the 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO. Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) country profile indicators: interpretation guide [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44397.

- 14.UN-DESA. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017. 2017.

- 15.Briones K. A guide to young lives rounds 1 to 5 constructed files. Young Lives Tech Note. 2018;48:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young Lives . Young lives Survey Design and Sampling (Round 5): Ethiopia. Oxford: Young Lives; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffery K, Chatterjee I, Lavin T, Li IW. Young lives and wealthy minds: the nexus between household consumption capacity and childhood cognitive ability. Econ Anal Policy. 2020;65:89–104. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2019.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wake SK, Zewotir T, Muluneh EK. Variations in physical growth trajectories among children aged 1–15 years in low and middle income countries: Piecewise model approach. Malaysian J Public Heal Med. 2021;21(3):200–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wake SK, Baye BA, Gondol KB. Longitudinal study of growth variation and its determinants in Body Weight of Children aged 1–15 years in Ethiopia. Iran J Pediatr. 2022;32(4):e122662. doi: 10.5812/ijp-122662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wake SK, Zewotir T, Muluneh EK. Growth characteristics of four low-and Middle-Income Countries Children Born just after the Millennium Development Goals. J Biostat Epidemiol. 2021;7(2):108–19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wake SK, Zewotir T, Muluneh EK. Studying latent change process in height growth of children in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03269-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wake SK, Zewotir T, Muluneh EK. Nonlinear physical growth of children from infancy to Middle Adolescence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J Res Health Sci. 2021;21(4):e00533. doi: 10.34172/jrhs.2021.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Astatkie A. Dynamics of stunting from childhood to youthhood in Ethiopia: evidence from the Young lives panel data. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(2):1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onis M, De, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Garza C, Comparison of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child growth Standards and the National Center for Health Statistics / WHO international growth reference : implications for child health programmes. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(7):942–7. doi: 10.1017/PHN20062005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group &. de Onis M. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length / height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu L. Mixed effects models for complex data. CRC Press; 2009.

- 27.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for Longitudinal Data. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Mercedes O, Edward AF, Monika B. Is malnutrition declining? An analysis of changes in levels of child malnutrition since 1980. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(10):1222–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takele K, Zewotir T, Ndanguza D. Understanding correlates of child stunting in Ethiopia using generalized linear mixed models. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6984-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenske N, Burns J, Hothorn T, Rehfuess EA. Understanding child stunting in India: A comprehensive analysis of socio-economic, nutritional and environmental determinants using additive quantile regression. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Habyarimana F, Zewotir T, Ramroop S, Ayele DG. Spatial distribution of determinants of malnutrition of children under five years in Rwanda: SimultaneousMeasurement of three anthropometric indices. J Hum Ecol. 2016;54(3):138–49. doi: 10.1080/09709274.2016.11906996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berhane HY, Jirström M, Abdelmenan S, Berhane Y. Social stratification, diet diversity and malnutrition among preschoolers: a survey of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):712. doi: 10.3390/nu12030712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nshimyiryo A, Hedt-Gauthier B, Mutaganzwa C, Kirk CM, Beck K, Ndayisaba A, et al. Risk factors for stunting among children under five years: a cross-sectional population-based study in Rwanda using the 2015 demographic and Health Survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6504-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKenna CG, Bartels SA, Pablo LA, Walker M. Women’s decision-making power and undernutrition in their children under age five in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0226041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tariku EZ, Abebe GA, Melketsedik ZA, Gutema BT. Prevalence and factors associated with stunting and thinness among school-age children in Arba Minch Health and demographic surveillance site, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0206659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bork KA, Diallo A. Boys are more stunted than girls from early infancy to 3 years of age in rural senegal. J Nutr. 2017;147(5):940–7. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.243246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quamme SH, Iversen PO. Prevalence of child stunting in Sub-Saharan Africa and its risk factors. Clin Nutr Open Sci. 2022.

- 38.Habaasa G. An investigation on factors associated with malnutrition among underfive children in Nakaseke and Nakasongola districts, Uganda. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0448-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renzaho AMN. Mortality rates, prevalence of malnutrition, and prevalence of lost pregnancies among the drought-ravaged population of Tete Province, Mozambique. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2007;22(1):26–34. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00004301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ickes SB, Hurst TE, Flax VL. Maternal literacy, facility birth, and education are positively associated with better infant and young child feeding practices and nutritional status among ugandan children. J Nutr. 2015;145(11):2578–86. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.214346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart CP, Iannotti L, Dewey KG, Michaelsen KF, Onyango AW. Contextualising complementary feeding in a broader framework for stunting prevention. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9:27–45. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ekholuenetale M, Tudeme G, Onikan A, Ekholuenetale CE. Socioeconomic inequalities in hidden hunger, undernutrition, and overweight among under-five children in 35 sub-saharan Africa countries. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2020;95(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s42506-019-0034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Makoka D. The Impact of Maternal Education on Child Nutrition: Evidence from Malawi, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. DHS Working Papers No. 84. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF International, 2013.

- 44.Eshete H, Abebe Y, Loha E, Gebru T, Tesheme T. Nutritional status and effect of maternal employment among children aged 6–59 months in Wolayta Sodo Town, Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27(2):155–62. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v27i2.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magadi MA. Social Science & Medicine Household and community HIV / AIDS status and child malnutrition in sub-saharan Africa : evidence from the demographic and health surveys. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(3):436–46. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kassaw MW, Bitew AA, Gebremariam AD, Fentahun N, Açik M, Ayele TA. Low Economic Class Might Predispose Children under Five Years of Age to Stunting in Ethiopia: Updates of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Nutr Metab. 2020;2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Fenta HM, Zewotir T, Muluneh EK. Disparities in childhood composite index of anthropometric failure prevalence and determinants across ethiopian administrative zones. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9 September):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kasaye HK, Bobo FT, Yilma MT, Woldie M. Poor nutrition for under-five children from poor households in Ethiopia: evidence from 2016 demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Sadeeq AH, Bukair AZ, Al-Saqladi AWM. Assessment of undernutrition using composite index of anthropometric failure among children aged 5 years in rural yemen. East Mediterr Heal J. 2018;24(12):1119–26. doi: 10.26719/2018.24.12.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fenta HM, Workie DL, Zike DT, Taye BW, Swain PK. Determinants of stunting among under-five years children in Ethiopia from the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and Health Survey: application of ordinal logistic regression model using complex sampling designs. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal. 2020;8(2):404–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2019.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Leger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. 2. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Young Lives data are publicly available and can be accessed from http://www.younglives.org.uk/.