Abstract

Background

AP2/ERF transcription factors (AP2/ERFs) are important regulators of plant physiological and biochemical metabolism. Evidence suggests that AP2/ERFs may be involved in the regulation of bud break in woody perennials. Green tea is economically vital in China, and its production value is significantly affected by the time of spring bud break of tea plant. However, the relationship between AP2/ERFs in tea plant and spring bud break remains largely unknown.

Results

A total of 178 AP2/ERF genes (CsAP2/ERFs) were identified in the genome of tea plant. Based on the phylogenetic analysis, these genes could be classified into five subfamilies. The analysis of gene duplication events demonstrated that whole genome duplication (WGD) or segmental duplication was the primary way of CsAP2/ERFs amplification. According to the result of the Ka/Ks value calculation, purification selection dominated the evolution of CsAP2/ERFs. Furthermore, gene composition and structure analyses of CsAP2/ERFs indicated that different subfamilies contained a variety of gene structures and conserved motifs, potentially resulting in functional differences among five subfamilies. The promoters of CsAP2/ERFs also contained various signal-sensing elements, such as abscisic acid responsive elements, light responsive elements and low temperature responsive elements. The evidence presented here offers a theoretical foundation for the diverse functions of CsAP2/ERFs. Additionally, the expressions of CsAP2/ERFs during spring bud break of tea plant were analyzed by RNA-seq and grouped into clusters A-F according to their expression patterns. The gene expression changes in clusters A and B were more synchronized with the spring bud break of tea plant. Moreover, several potential correlation genes, such as D-type cyclin genes, were screened out through weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA). Temperature and light treatment experiments individually identified nine candidate CsAP2/ERFs that may be related to the spring bud break of tea plant.

Conclusions

This study provides new evidence for role of the CsAP2/ERFs in the spring bud break of tea plant, establishes a theoretical foundation for analyzing the molecular mechanism of the spring bud break of tea plant, and contributes to the improvement of tea cultivars.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-023-04221-y.

Keywords: Tea plant, AP2/ERF, Spring bud break, Low temperature, Light

Background

The AP2/ERF family is one of the largest transcription factor family that is mainly found in plants [1]. This family detects and binds numerous cis-acting elements, such as GCC-box, DRE/CRT, and CEI, and is involved in the expression of various plant genes [2]. In general, AP2/ERFs have at least one conserved AP2 domain, which comprises 60–70 amino acid residues, forming a typical 3D structure of three β-folds and one α-helix [3–5]. According to Sakuma’s classification method [6], the AP2/ERF family can be divided into five categories, namely DREB, ERF, AP2, RAV subfamilies and Soloist.

With the genome-wide identification and analysis of the AP2/ERF family in different plants (such as Arabidopsis [7, 8], rice [7], peanut [9], grapevine [10] and poplar [11]), the research on their functions has been deepened. AP2/ERFs are associated with the construction of complex signal transduction pathways in plants. They respond to a variety of stimuli, for example, extreme temperature, drought, high salt and hormones (ethylene, gibberellin and abscisic acid) [2], and have emerged as key regulators of the various physiological and biochemical reactions of plants, which assist plants in effectively improving their ability to cope with adversity stress [12, 13]. Furthermore, AP2/ERFs regulate the expressions of target genes during numerous phases of plant growth and development, including cell proliferation and differentiation [14–17], flower growth [3, 18], bud break [19–23] and leaf senescence [24, 25]. Studies in tea plant have shown that the AP2/ERF family contains the most abundant transcription factors in tea plant [26]. Some AP2/ERFs have been cloned in tea cultivars ‘Shuchazao’, ‘Anji Baicha’ and ‘Yingshuang’ [27–30]. Further research indicated that these regulators mainly responded to abiotic stress, such as low temperature, high salt and ethylene. RNA-seq analysis was also performed on a short winter dormancy tea cultivar ‘Emei Wenchun’, in which the PB.2659.1, an AP2/ERF transcription factor closest to PtEBB1 in poplar, was screened out by significantly differentially expression analysis [22, 31].

The economic value of tea plant is inextricably connected with its growth and development period. Green tea production accounts for more than 60% of the tea industry in China, with spring elite green tea accounting for more than half of the total output value. However, the economic benefits of spring elite green tea heavily depend on the harvest time. The bud break time in spring has a direct effect on the yield of spring tea since the fresh shoots of tea plant are the main harvest objects. Accordingly, the spring bud break period, as an important agronomic trait of the growth and development period in tea plant, has received extensive attention in the tea industry. A large number of independent genes regulate the release of the bud dormancy and the bud break as a complex process controlled by multiple genes. Genes, such as CsCDK1 [32], CsARF1 [33], CsAIL (an AP2/ERF transcription factor) [34] and CsDAM1 [35], have been cloned in tea plant, and their expressions have been confirmed to change during the dormancy release of tea plant. However, the molecular mechanism of tea plant bud break remains largely unknown.

Although some AP2/ERFs have been cloned in tea plant, few reports have focused on tea plant bud break. Here, AP2/ERF family in tea plant was analyzed using bioinformatics. The analysis focused on the classification of the gene family, phylogenetic tree information, chromosome localization, gene duplication, cis-acting elements of the promoters, gene structure, and conserved motifs. Subsequently, the expression patterns of CsAP2/ERFs in different stages of spring bud break were explored by RNA-seq, and the potential interaction genes were mined by weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA). Finally, temperature and light treatment were conducted on tea plant to explore the response patterns of CsAP2/ERFs. This research provided a reference point for further study on the molecular mechanisms of CsAP2/ERFs in regulating the bud break of tea plant.

Results

Identification of CsAP2/ERFs in tea plant

According to the annotation information of the AP2 domain (PF00847), 178 AP2/ERF genes were identified from the tea plant genome. The protein sequences of these genes were extracted and compared with 147 AP2/ERF proteins in Arabidopsis. Based on the domain characteristics and sequence similarity, the AP2/ERF family in tea plant was divided into five categories, namely DREB subfamily (52 members), ERF subfamily (88 members), AP2 subfamily (30 members), RAV subfamily (4 members) and Soloist (4 members). We named these genes in accordance with the family classification and genome location information, and recorded them in Table S1. Thereafter, the basic physicochemical properties of CsAP2/ERFs were analyzed. The amino acid lengths of CsAP2/ERFs ranged from 67 aa (CsSoloists-01) to 748 aa (CsAP2-29), and the protein molecular weight (MW) ranged from 74.54 kDa (CsSoloists-01) to 811.66 kDa (CsAP2-29). The theoretical isoelectric point (pI) varied from 4.49 (CsERF-36) to 10.24 (CsERF-70).

Phylogenetic analysis of CsAP2/ERFs

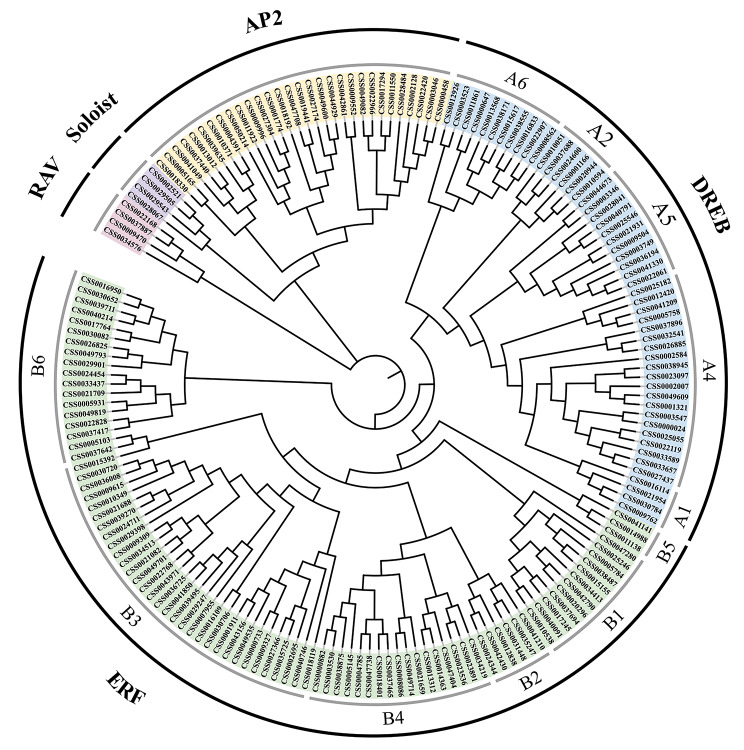

An unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed in tea plant by using the conserved sequences of proteins in the CsAP2/ERF family (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, the DREB and ERF subfamilies were subdivided into six groups based on two main distribution methods proposed by Sakuma [6] and Nakano [7]. Table 1 summarizes the number of AP2/ERFs of tea plant, Arabidopsis [7], poplar [11] and grapevine [10]. Overall, the ERF subfamily has a numerical advantage in all species listed. According to the comparison of the distribution of subfamilies in four species, the distribution of CsAP2/ERFs was more similar to that of poplar and grapevine. Moreover, the A3 group (IVb) of DREB subfamily was missing in tea plant and grapevine, which is consistent with previous reports [10, 26].

Fig. 1.

A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of the AP2/ERF family in tea plant. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on 178 conserved domain sequences of CsAP2/ERFs. The CsAP2/ERF family was allocated to five subfamilies (DREB subfamily with groups A1-A6, ERF subfamily with groups B1-B6, AP2 subfamily, RAV subfamily and Soloist), and covered with different colors

Table 1.

Summary of the AP2/ERF family in tea plant, Arabidopsis, poplar and grapevine

| Distribution method | Sakuma’s method | Nakano’s method | Camellia sinensis | Arabidopsis thaliana | Populus trichocarpa | Vitis vinifera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family/subfamily | Group | Group | ||||

| DREB | A1 | IIIc | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| A2 | IVa. IVb | 6 | 8 | 18 | 4 | |

| A3 | IVb | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| A4 | IIIa, IIIb, IIId, IIIe | 20 | 16 | 26 | 13 | |

| A5 | IIa, IIb, IIc, IIIa | 11 | 16 | 14 | 7 | |

| A6 | Ia, Ib | 11 | 10 | 11 | 5 | |

| Total | 52 | 57 | 77 | 36 | ||

| ERF | B1 | VIIIa, VIIIb | 12 | 15 | 19 | 7 |

| B2 | VII | 6 | 5 | 6 | 3 | |

| B3 | IXa, IXb, IXc,Xb | 32 | 17 | 35 | 37 | |

| B4 | Xa, Xc | 17 | 8 | 7 | 4 | |

| B5 | VI | 3 | 8 | 8 | 4 | |

| B6 | Va, Vb, VI-L, Xb-L | 18 | 12 | 16 | 18 | |

| Total | 88 | 65 | 91 | 73 | ||

| AP2 | 30 | 18 | 26 | 18 | ||

| RAV | 4 | 6 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Soloist | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 178 | 147 | 200 | 132 |

Gene location and genome synteny of CsAP2/ERFs

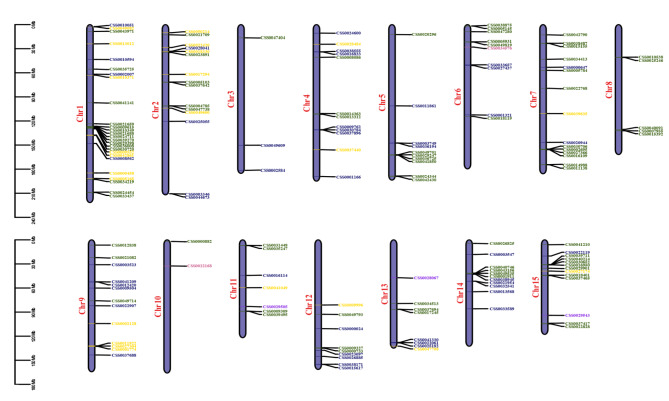

159 CsAP2/ERFs were unevenly distributed across 15 chromosomes, except for 19 genes on contigs (Fig. 2). Chr1 had the largest number of CsAP2/ERFs (26 genes), whereas Chr10 had the smallest (2 genes). CsDREBs located on every chromosome except Chr 8 and Chr 10. Apart from that, two CsRAVs were mapped on Chr6 and Chr10, as well as three CsSoloists were mapped on Chr 11, Chr 13 and Chr15. CsERFs were more likely to get clustered on chromosomes compared with other CsAP2/ERFs. Clustered CsERFs were easy to spot in Chr1, Chr5, Chr7, Chr14 and Chr15. Every chromosome contained more than two types of CsAP2/ERFs, while Chr 8 only has CsERFs.

Fig. 2.

Genome location of 159 CsAP2/ERFs on 15 chromosomes. The chromosomal positions of CsAP2/ERFs were mapped according to the genome of tea cultivar ‘Shuchazao’. The subfamilies were shown in different colors (CsDREBs in blue, CsERFs in green, CsAP2s in yellow, CsRAVs in pink and CsSoloists in purple)

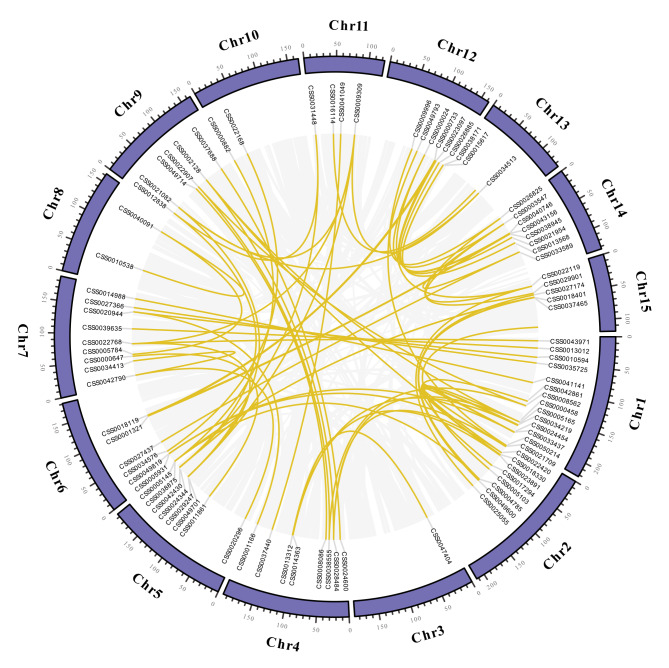

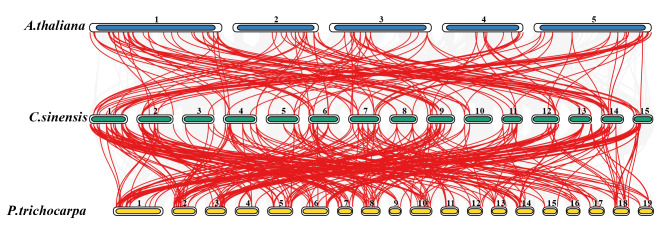

We detected gene duplication events in the CsAP2/ERF family in tea plant (Fig. 3), and 72 pairs of whole genome duplication (WGD) or segmental duplication events and 13 pairs of tandem duplication events were found. Thus, WGD or segmental duplication was the main expansion pattern of the CsAP2/ERF family. Meanwhile, tandem duplication promoted the extension of CsDREBs and CsERFs. We calculated the Ka/Ks values for all paralogous genes to assess the selection pressures (Table S4). The results showed that the ratios of Ka/Ks between all paralogous gene pairs were less than one, indicating that purifying selection was dominant during the evolution of the CsAP2/ERFs. To further explore the potential evolutionary mechanisms of the CsAP2/ERF family, the synteny analysis of the AP2/ERF families of tea plant, Arabidopsis and poplar was conducted (Fig. 4). The synteny relationships are presented in Table S5. The results showed that tea plant has more AP2/ERF gene pairs with poplar (300 pairs) than with Arabidopsis (133 pairs). This result suggested that the AP2/ERF family of tea plant was evolutionarily similar to poplar.

Fig. 3.

The synteny analysis of CsAP2/ERFs. The value on each chromosome represents the chromosome length in Mega base (Mb). The gray lines indicate all synteny blocks in the genome of tea cultivar ‘Shuchazao’, and the gold lines denote the whole genome duplication (WGD) or segmental duplicated gene pairs of CsAP2/ERFs

Fig. 4.

The synteny analysis of AP2/ERFs between Arabidopsis, tea plant and poplar. Gray lines indicate all synteny blocks between tea plant and the other two species. The red lines indicate the orthologous AP2/ERFs

Gene structure and conserved motif analysis of CsAP2/ERFs

The CDS, UTR and introns were analyzed to characterize the gene structure of CsAP2/ERFs. The CsAP2s had the unique gene structures in the CsAP2/ERF family, and they tended to include several short tandem CDS regions (Figure S2). Comparatively, the other four subfamilies had fewer number of CDS, ranging from one to four in the majority (Figure S3-S6), and CSS0012420 (CsDREB) was one exception which had seven CDS. All CsRAVs and several CsDREBs had a long, complete CDS almost covering the whole genes. A total of 76 CsAP2/ERFs had the UTRs in their structure, but nine of them only had the 5’-UTR as well as 16 only had the 3’-UTR.

15 conserved motifs were predicted by the MEME to investigate the key motif in CsAP2/ERFs. The motif compositions were distinct in different subfamilies (Figure S2-S6). However, motif 1 was conserved in all CsAP2/ERFs except all CsSoloists and two CsERFs (CSS0005103 and CSS0037642). CsAP2s had two main composite patterns, one was motif 1-motif 3-motif 1, and the other was motif 7-motif 10-motif 2-motif 1. Based on these basic patterns, the composition of CsAP2s would add or replace some motifs. CsDREBs, CsERFs and CsRAVs had a similar motif composition, a series connection of motif 2-motif 4-motif 1. On this basis, more than half of CsDREBs added motif 6, and only one CsDREB (CSS0033589) added motif 8. Motif 11 was conserved in CsRAVs compared with motif 9. Different from CsDREBs and CsRAVs, the motifs of CsERFs were more diverse in groups B3 and B6. Motif 9 was found in group B6, while motifs 8, 13 and 14 were found in group B3. Besides, CsSoloists were half more covered with motif 12.

Putative cis-acting element analysis of CsAP2/ERFs

The PlantCARE database was exploited to analyze the cis-acting elements in CsAP2/ERFs. As the results showed in Table S6, the elements were classified into five categories: hormone response, plant growth and metabolic regulation, stress response, structural elements and transcription factor binding sites. The hormone responsive elements include five types: abscisic acid response (ABRE), auxin response (TGA-element and AuxRR-core), gibberellin response (TATC-box, P-box and GARE-motif), MeJA response (TGACG-motif and CGTCA-motif) and salicylic acid response (TCA-element). Plant growth and metabolic regulation elements contain MSA-like (cell cycle regulation), circadian (circadian control), HD-zip 1 (differentiation of the palisade mesophyll cells), ACE (light response), CAT-box (meristem expression), RY-element (seed-specific regulation) and so on. The third type is stress responsive elements, such as the wound responsive element (WUN-motif) and the low-temperature responsive element (LTR). The fourth type consists of structural elements, such as the protein binding site (Box III/HD-Zip 3) and promoter and enhancer regions (CAAT-box). Finally, the common transcription factor binding sites include the MYB binding site (MBS, MBSI and MRE) and the MYBHv1 binding site (CCAAT-box).

In CsAP2/ERFs, the most widely distributed cis-acting elements are the structural elements, which account for more than 70% of the total amount in the five subfamilies, and are as high as 80.34% in CsSoloists. In addition, plant growth and metabolic regulation elements account for more than 10% in each subfamily, the highest is 13.98% in CsERFs, followed by 13.20% in CsAP2s and 12.72% in CsRAVs. The distribution of the hormone responsive elements widely varied, ranging from 8.67% (CsRAVs) to 3.42% (CsSoloists). CsDREBs (6.31%) and CsERFs (6.51%) have similar numbers of hormone responsive elements, while CsSoloists (3.42%) have slightly less. Stress responsive elements accounted for 3.13% (CsDREBs), 3.14% (CsERFs), 4.53% (CsAP2s), 2.89% (CsRAVs), and 4.56% (CsSoloists) of the total, respectively. Among the five subfamilies, transcription factor binding sites are the least distributed, occupying only about 1% of the total cis-acting elements.

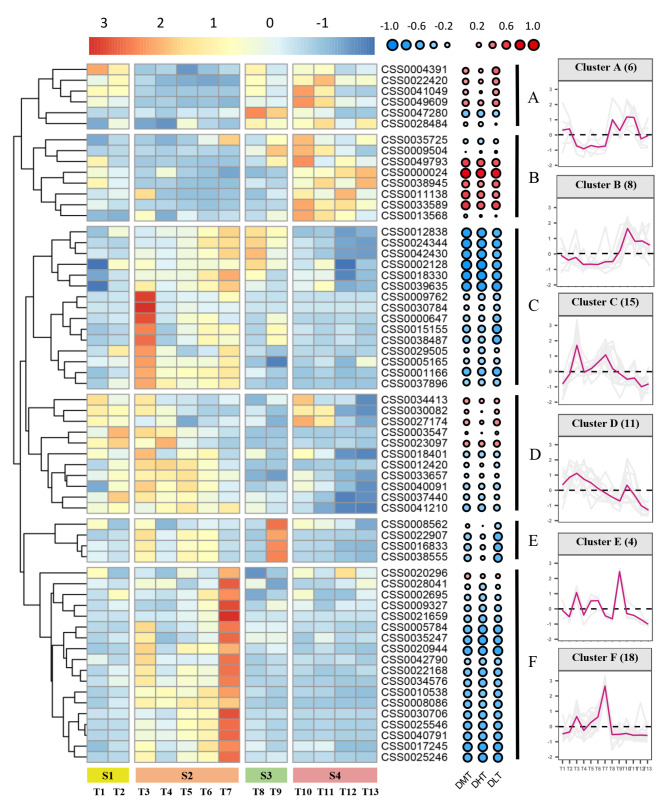

Expression profiles of CsAP2/ERFs during spring bud break

The expression profiles of CsAP2/ERFs were detected by RNA-seq, and the results were analyzed from T1 (November 1, 2021) to T13 (March 19, 2022) to clarify the role of CsAP2/ERFs during tea plant bud break, which were classified into four stages (S1: paradormancy, S2: endodormancy, S3: ecodormancy and S4: bud expansion and break) [36–38]. A total of 62 CsAP2/ERFs were selected by the FPKM values (FPKM > 5) (Table S7). These genes were hierarchically clustered according to the expression similarities and grouped into six expression modules, naming clusters A-F for further analysis (Fig. 5). Cluster F contained the largest number of CsAP2/ERFs (18 members). 15 genes belonged to cluster C, followed by clusters D, B and A, which contained 11, 8 and 6 CsAP2/ERFs severally. Besides, cluster E contained the last number of CsAP2/ERFs (4 members).

Fig. 5.

Heatmap of CsAP2/ERFs during the different stages of tea plant bud break. The 62 CsAP2/ERFs clustered into six groups based on their specific expressions during the four stages (S1-S4) of tea plant bud break (S1: T1-T2, S2: T3-T7, S3: T8-T9 and S4: T10-T13). The circular heatmap showed the correlation analysis between the environmental factors and gene expression levels (DMT: daily mean temperature, DHT: daily maximum temperature, DLT: daily minimum temperature). The graph on the right of the heatmap showed the expression patterns of the six distinct clusters. Gene expression levels were represented by standardized FPKM values. The standardization method was z-score, z = (x − µ)/σ (x: original value, z: transformed value, µ: mean and σ: standard deviation)

The analysis of the clustering results indicated that there were two main expression patterns. Clusters A and B more actively expressed in the stages close to bud break (S3 and S4), while other clusters in the early stages (S1 and S2). The expression of cluster A sharply decreased after S1, and it was almost not expressed in the whole S2. The expression of cluster B was similar to that of cluster A in this phase. The expression recovery of clusters A and B was observed in S3 and slightly declined in S4. In contrast, other clusters were inactive in both S3 and S4 periods except for cluster E with a transient recovery of expression in T9 (S3). Clusters C, E and F showed apparent expression peaks during the whole expression process compared with clusters A, B and D. The highest expression levels were evident in T3 (S2), T9 (S3) and T7 (S2). The expression peak of cluster E appeared at T9, and two obvious fluctuations occurred before this. Clusters C and F had virtually identical expression patterns, and they showed high expression levels at T3 and T7. In contrast with cluster C, the expression peak of T7 was higher than that of T3 in cluster F.

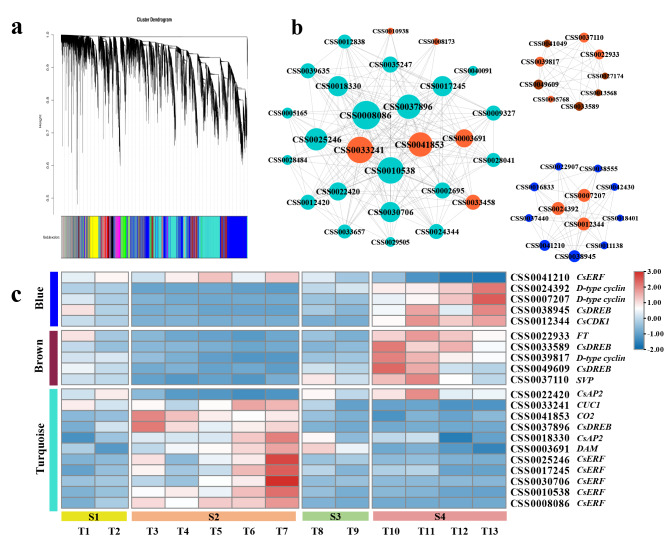

Expression profiles of the potential interacting genes of CsAP2/ERFs

WGCNA was performed to explore the potential interaction genes of CsAP2/ERFs to further elucidate the mechanism of CsAP2/ERFs in tea plant bud break regulation (Fig. 6a). In the clustering module of WGCNA, the previously mentioned CsAP2/ERFs (picked by FPKM > 5) were mainly divided into three modules, namely, Blue, Brown and Turquoise. Meanwhile, some reported genes involved in the bud break of woody perennials appeared in these three modules. The co-expression network between CsAP2/ERFs and bud break related genes were analyzed (Fig. 6b). The top 50% genes in each network were selected according to the degree values to further analysis. Subsequently, referring to the correlation coefficients (Table S8), the expression profiles of 12 CsAP2/ERFs and nine highly related genes (|r| > 0.70) were shown in Fig. 6c.

Fig. 6.

Screening of potential interacting genes based on WGCNA. (a) Clustering dendrogram of the average network adjacency for identifying potential interacting genes. The genes in modules are marked with different colors. (b) Gene networks in blue, brown and turquoise modules. The CsAP2/ERFs in these three modules are severally colored with the module color, and the orange dots show the bud break related genes. The dot size represents the degree values. (c) The expression profiles of the selected genes from the blue, brown and turquoise modules

CSS0041210 and CSS0038945 was classified into Module Blue. Three cyclin-related genes (CSS0024392, CSS0007207 and CSS0012344) were found in this module. These genes had similar expression patterns with CSS0038945 (r > 0.80) and were negatively correlated with the expression of CSS0041210 (r ≤ −0.85). The expressions of genes listed in Module Brown were consistent (r > 0.70), and their expression peaks appeared at S4 and decreased with the development of the tea buds. The gene expression peak in Module Turquoise mainly appeared in S2, while CSS0022420 was not active in this phase. The results of the correlation analysis showed that the expression of CSS0022420 was negatively correlated with CSS0041853 (CO2), and the correlation coefficient was −0.73. Concurrently, CSS0041853 (CO2) was positively correlated with the expressions of CSS0010538, CSS0008086 and CSS0037896, and the correlation coefficients were 0.78, 0.86 and 0.95, respectively. The expression of CSS0010538 was also highly consistent with CSS0003691 (DAM) and CSS0033241(CUC1), with the correlation coefficients of 0.70 and 0.79 separately. CSS0033241(CUC1) had the highest expression correlation with CSS0008086 (r = 0.80).

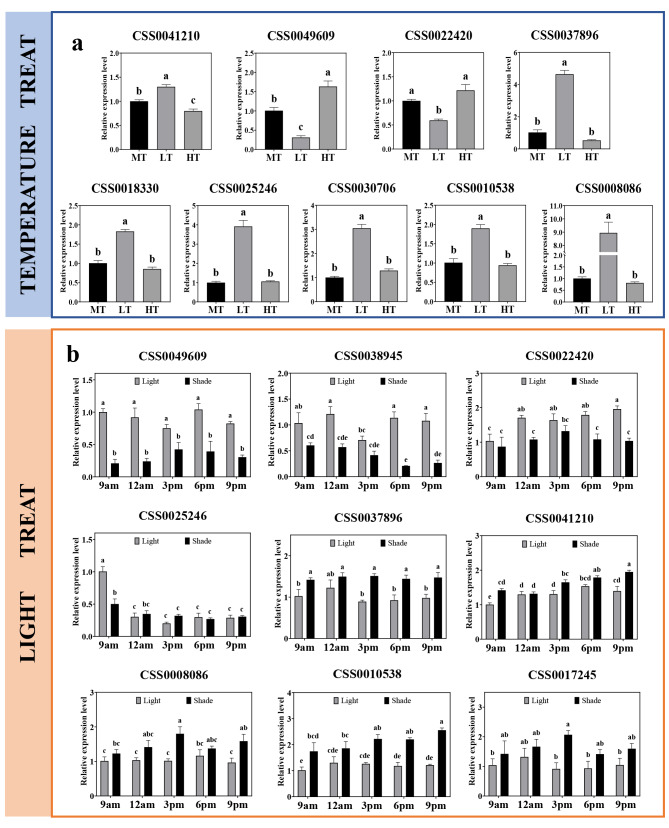

Expression profiles of CsAP2/ERFs under low and high temperature treatment

The WGCNA analysis mentioned above found 12 CsAP2/ERFs which had the potential relationships with bud break related genes, and the temperature experiments were performed to further verify whether these genes were involved in bud break under temperature-controlled processes. And interestingly, nine CsAP2/ERFs, which responded to high (30 °C) or low temperature (4 °C) treatment, were discovered (Fig. 7a). The results of the expression levels indicated that they were all sensitive to low temperature, and CSS0041210 and CSS0049609 were simultaneously influenced by high temperature.

Fig. 7.

Expression profiles of CsAP2/ERFs under treatments. (a) Temperature treatment. MT: middle temperature (15 °C), LT: low temperature (4 °C) and HT: high temperature (30 °C). (b) Light treatment. The error bars exhibit the means ± SE (n = 3) gained from the three independent biological replicates. The letter represents the significance of the differences (LSD test, P < 0.05)

Expression profiles of CsAP2/ERFs under light treatment

The expression profiles of 12 CsAP2/ERFs screened by WGCNA were detected under light treatment. As the results showed in Fig. 7b, nine CsAP2/ERFs responded to light, and four of them were down-regulated under shade treatment while five were up-regulated. CSS0049609 expressed significantly different at five sampling times, however, CSS0025246 and CSS0017245 distinguished at only one time.

Discussion

The AP2/ERF family is vital in plant development and stress resistance [2]. However, the identification and functional studies of this family remain poorly understood due to the complex genetic background of tea plant. 89 CsAP2/ERFs were previously characterized using transcriptome data [26]. In this study, we identified more CsAP2/ERFs (178) in the genome of tea plant, and they were grouped into five subfamilies according to the contained domains and the sequence conservation. The number of AP2/ERFs greatly varies among different species, as shown in Table 1. The number of CsAP2/ERFs in tea plant is relatively large among the plants we have listed. This condition could be caused by the two WGD events in tea plant during the process of genome evolution [39]. In addition, 72 pairs of WGD or segmental duplication were detected in tea plant, making a major construction to the increase in the number of CsAP2/ERFs, which is different from the main amplification of other transcription factor families, such as WRKY and PME [40, 41]. The amplification of AP2/ERFs in several plants, such as pear [42] and pumpkin [43], is also dominated by segmental duplication. Accordingly, segmental duplication may be a main extension form of AP2/ERFs. Moreover, not all duplicated genes had similar expression profiles (Fig. 5), which had also been confirmed in pumpkin [43]. Based on the result of the comparison of the synteny of AP2/ERFs between tea plant, Arabidopsis and poplar, more gene pairs are present in tea plant and poplar. Given that both are woody perennials, more similar selective pressure and closer relationship may support the formation of more orthologous genes [39, 44, 45].

The differences in gene structure and composition may contribute to the functional diversity of AP2/ERFs [43, 46]. The gene structure analysis showed that the same group or subfamily shared similar gene structures in the CsAP2/ERF family. For example, the CsAP2 subfamily tended to contain three to nine short and tandem CDS regions (Figure S2c), while the CsDREB and CsERF subfamilies were more likely to form an intron-free structure (Figure S3c, 4c). The structural characteristics of these subfamilies are consistent with the AP2/ERFs in other plant [43, 47, 48]. The classification results obtained from phylogenetic trees basically match the prediction results of the conserved domain (Figure S2-S6), indicating that the conserved domains are also an important identification feature of the classification in the AP2/ERF family. The analysis of the motif composition revealed that most CsAP2/ERFs contained motifs 1, 2 and 4, which were associated with the AP2 domain. Additionally, the subfamilies were differentiated into their unique motifs, such as motif 6 of the CsDREB subfamily, motif 14 of the CsERF subfamily and motif 15 of the CsAP2 subfamily, which may support their different functions [49]. Meanwhile, the exogenous hormones and environmental signals may be vital in regulating the transcriptional activity of AP2/ERFs [2], and the recognition of these signals needs to be accomplished by cis-acting elements. The analysis of the cis-acting elements on the promoters of CsAP2/ERFs proved that there were various types of hormone response elements and signal-sensing elements (Table S6), such as abscisic acid responsive elements (ABRE), gibberellin responsive elements (TATC-box, P-box and GARE-motif), light responsive elements (ACE) and low temperature responsive elements (LTR). The existence of multiple signal-sensing elements supports the involvement of AP2/ERFs in plant physiology and metabolism.

AP2/ERFs are involved in the construction of plant growth and development system and have been confirmed to play a regulatory role in the bud break of woody perennials, such as poplar [20, 22], pear [19] and peach [23]. Most tea plants located in the temperate tea producing area need to experience a cycle of spring bud break and winter dormancy as a member of woody perennials [44, 50, 51]. We observed the bud break process of the tea buds from November 2021 to March 2022 (from S1 to S4) (Figure S1). The tea buds experienced paradormancy, endodormancy and ecodormancy in S1-S3, respectively. The growth of the tea buds stopped at this time due to the surrounding environment or endogenous signals [52, 53]. At the end of S3, the growth points of the tea buds regained their growth capacity but remained in a state of growth arrest due to the limitations of growth conditions [54]. Next, the growing substances in the tea buds continued to accumulate in S4, which made the tea buds enter the expansion period (T10-T12). On March 19, 2022 (T13), the tea buds broke. Consequently, tea plant entered the one and a bud (one bud with one leaf) stage.

Favorable external environment is the key factor for spring bud break of tea plant. Temperature and light are essential in tea plant dormancy to bud break transition[31, 55–59]. Here, we investigated the cis-elements of CsAP2/ERFs on their promoters and showed that many cis-elements were signal perception elements, such as LTR (low temperature response), ACE and G-box (light response). By calculating the correlation between the expressed CsAP2/ERFs with daily minimum temperature (DLT), daily maximum temperature (DHT) and daily mean temperature (DMT), it was found that most genes were related to the DLT, accounting for 42.50% (|r| ≥ 0.5) (Table S7). Meanwhile, the temperature and light treatment found that nine CsAP2/ERFs could significantly respond to low temperature, and nine could respond to light. Among the above-mentioned genes, seven of them can respond to both low temperature and light.

Tea plant regenerates productive buds in spring under suitable conditions, and this phase is a multi-signal regulation process, which often occurs with altered gene expressions [33, 35, 60, 61]. The expressions of CsAP2/ERFs were detected by RNA-seq during the whole process from winter dormancy to spring bud break. The cluster analysis divided the gene expressions into clusters A-F. The gene expressions of clusters A and B were highest at the end of the dormant stage and the tea bud expansion stage. The high-level expression of cluster C-F appeared in the early of stage of dormancy, they expressed barely near the tea bud break. The seasonal expression analysis of woody perennials showed that AP2/ERFs had a huge expression transition after chilling accumulation of dormancy or before bud break. In poplar, the expression of EBB3 was induced by low temperature in the winter/spring months (November to March) [20]. The similar expression pattern of PpEBB was found in pear [19]. Compared with poplar and pear, cluster A and B were more synchronized with the process of tea plant bud break in spring. Further research revealed that CSS0047280 in cluster A is the orthologous gene of ESR2 in Arabidopsis. ESR2 is vital in shoot regeneration through the transcriptional regulation of CUC1, and ectopic expression of CUC1 could promote adventitious shoot formation from Calli through Shoot Apical Meristem (SAM) activation [62]. This work provided a reference for studying the potential mechanism of CSS0047280 in tea plant bud break. In addition, the CSS0035725 in cluster B had high homology with EBB3, the bud break regulation gene in poplar [20]. This result also indicates that this gene may have a similar function to EBB3 in regulating the bud break. Furthermore, the genes in other clusters were down-regulated before tea plant bud break, showing an opposite expression pattern to the genes in clusters A and B which also suggested a possible negative regulatory mechanism.

D-type cyclins are an important cell cycle progression checkpoint, whose expression correlates with bud reactivation of growth at the bud break, and participates in compound pathways in the regulation of bud break in woody perennials [20, 34, 63, 64]. In poplar, CYCD3.1 promotes poplar bud break, and it is up-regulated by EBB3 which is up-regulated by EBB1. The entire pathway is induced by low temperature signals [20]. Our study found a CsAP2/ERF (CSS0049609) that could respond to low temperature signal and were highly correlated with D-type cyclin genes in expression. CSS0039817, the orthologous gene of poplar CYCD3.1, had a similar expression pattern to CSS00033589 and CSS0049609 in module Brown. The correlation coefficients of gene expression were 0.89 (CSS0039817 and CSS0033589) and 0.90 (CSS0039817 and CSS0049609) during spring bud break (Table S9). These results demonstrate that CSS00033589, CSS0049609 and CSS0039817 may be similar to the regulation mechanism of EBB1 and EBB3 on CYCD3.1. Moreover, CSS0028484 and CSS0022420 had high sequence similarity and similar expression profile with CsAIL, an AP2/ERF transcription factor reported in tea plant [34]. Previous studies have shown that CsAIL may be an upstream regulatory gene of tea plant D-type cyclin genes CsCYCD3.2 and CsCYCD6.1, which is consistent with our experimental results. The above-mentioned results provide evidence to prove that the CsAP2/ERFs are involved in the expression and regulation of D-type cyclin genes, thereby affecting tea plant bud break.

Conclusions

This study performed a systematic analysis of the CsAP2/ERF family in tea plant. A total of 178 CsAP2/ERFs were identified and divided into five subfamilies. The evolution, gene location, conserved motifs, and cis-acting element features of CsAP2/ERFs were investigated. Furthermore, the expression patterns of CsAP2/ERFs in different periods of tea plant bud break were analyzed. Nine low temperature responsive and nine light responsive CsAP2/ERFs were found during the experiment of the temperature and light treatments. Finally, CsAP2/ERFs may be an upstream regulator of D-type cyclin genes, which affected tea plant bud break in spring. Our study provided a new direction for further research on the functioning of CsAP2/ERFs in tea plant bud break.

Materials and methods

Identifications of the CsAP2/ERFs

The genome data and annotation information of the chromosome-level reference of tea plant were downloaded from TPIA (http://tpdb.shengxin.ren/) [65]. The Hidden Markov Model (HMM) file was downloaded from InterPro (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/download/Pfam/) [66] and submitted to Simple HMM Search of TBtools [67] along with the AP2 domain ID (PF00847). The above-mentioned steps were used to retrieve the AP2/ERF proteins from the tea plant genome [39]. After eliminating repetitive sequences, the rest of the proteins were analyzed by CD-search of NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) [68]. Ultimately, 178 CsAP2/ERFs were identified. The ExPAsy ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) [69] was employed to predict the physical and chemical parameters of the CsAP2/ERF proteins, including the amino acids, molecular weight and isoelectric points (Table S1).

Phylogenetic tree construction

The protein sequences of 178 CsAP2/ERFs were extracted from the tea plant genome by TBtools [67], and the AP2/ERF protein sequences of Arabidopsis were downloaded from the PlantTFDB (http://planttfdb.gao-lab.org/) [70]. The conserved domains were predicted through CDD (http://www.ncbi.nl.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) [71], and the predicted results were downloaded for phylogenetic analysis. Then, all sequences were aligned by MUSCLE in MEGA [72] with the neighbor-joining (NJ) method using the Poisson model, and the bootstrap test was replicated 1000 times. The result was imported into the iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/) [73] to display the phylogenetic tree.

Chromosomal distribution and gene duplication

The location information of CsAP2/ERFs on the chromosomes was collected by the TeaGVD (http://www.teaplant.top/teagvd) [74]. One Step MCScanX of TBtools [67, 72] was used to identify the synteny regions on the tea plant genome [39] based on E-value ≤ 1E −5. Then, the paralogous relationships were extracted by the ID information of CsAP2/ERFs. The genome data and annotation information of the Arabidopsis and poplar were downloaded from EnsemblPlants (http://plants.ensembl.org/info/data/ftp/index.html) [75]. The above-mentioned files were used for synteny analysis together with the genome information of the tea plant [39]. The chromosomal localization and gene synteny were visualized by TBtools [67]. Finally, non-synonymous substitutions (Ka) and synonymous substitutions (Ks) of the paralogous genes were calculated using KaKs_Calculator 2.0 with the calculation method NG [76].

Gene structure, conserved motif and promoter analysis

The structures (CDS, UTR and introns) of 178 CsAP2/ERFs were extracted from the genome annotation information of tea plant [39] and displayed through the GSDS (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/) [77]. Then, the TBtools [67] was used to extract the genome sequences of 178 CsAP2/ERFs and the 2 kb sequences upstream from the transcription start site. The MEME (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme) [78] was used to identify conserved motifs. The 2 kb sequences upstream of the genes were analyzed by the PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) [79] for predicting the cis-acting elements in the promoters of CsAP2/ERFs.

Plant growth and treatment

The 8-year-old early-sprouting tea cultivar ‘Longjing43’ was grown in Shengzhou experimental base, Tea Research Institute of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (TRICAAS), Zhejiang, China. From November 1, 2021 to March 19, 2022, the apical buds were sampled 13 times depending on the development of buds and weather conditions. The records of sampling can be obtained from Figure S1 and Table S3. In the same field in Shengzhou, tea plants with consistent growth were selected for light treatment. The tea plant in light group grew naturally without additional treatment. the shade group was shaded for four days before sampling, and the shading rate was 95%. On the fifth day, two groups of tea plant were sampled every three hours separately, from 9am to 9pm on December 14, 2021. Potted early-sprouting tea cultivar ‘Longjing43’ (2-year-old) with consistent and robust growth was cultivated in the greenhouse. The tea plant was then moved into the high (30 °C), low (4 °C) and middle (15 °C) temperature climate chambers for treatment. The humidity of the artificial climate chamber used for temperature treatment was set at 70%, and the photoperiod of 14 h of light (10,000 lx) and 10 h of darkness is maintained. After two days of treatment, the apical buds were harvested, and frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Three biological replicates were set up for each sample.

Gene expression analysis based on RNA-seq and qRT-PCR

The total RNA was extracted by EASY-spin Plus Complex Plant RNA Kit (Aidlab Biotechnologies Company, Beijing, China) and used to construct cDNA libraries. The Agilent bioanalyzer 2100 system was used to detect the library quality. The qualified libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina Inc., CA, USA) developed by the Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). After removing the unqualify reads (adapter reads, poly-N reads and low-quality reads), the clean reads were aligned to the tea plant genome using HISAT2 [80]. The average total reads were 44,917,372, and the average map rate up to 85.94%. The transcript expression levels of individual genes were quantified using FPKM values, which were counted by featureCounts basing on the length of the gene and reads count mapped to the genes.

Subsequently, the gene expression heatmap was generated by TBtools [67]. Real-time qPCR was conducted on LightCycler® 480 II (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, BW, Germany) using LightCycler® 480 SYBR® Green I Master (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, BW, Germany). Each treatment performed three biological and three technical replicates. The relative expression level was calculated by using the 2−ΔΔCT method [81]. The internal reference gene was CsGAPDH. The primer sequences of the reference genes and CsAP2/ERFs are listed in Table S2.

WGCNA analysis

WGCNA [82] was performed by the R package. The gene expression data were obtained from RNA-seq. All genes were filtered by the standard of FPKM > 1, and we set the soft threshold to nine to construct the network. The dissimilarity between genes was used for the hierarchical clustering of genes, and a hierarchical clustering tree was established. Then, the tree was cut into 15 modules (the minimum number of genes in the module was 30) by using the dynamic shearing method, and the modules with a coefficient of dissimilarity less than 0.25 were merged. The WGCNA results were used to identify gene sets with high covariation and to mine potential interacting genes. The gene co-expression network was visualized using Cytoscape [83].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AP2/ERF

APETALA2/Ethylene responsive factor

- WGCNA

weighted correlation network analysis

- DREB

dehydration responsive element binding protein

- RAV

Related to ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE3 (ABI3)/VIVIPAROUS1(VP1)

- WGD

whole genome duplication

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads

Author Contributions

JQM and LC conceived the study. YJL, JYW, MYW and XMT collected the samples. YJL performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. SC and JDC provided software support. JQM, LC and SC revised the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1200200), the Major Project of Agricultural Science and Technology in Breeding of Tea Plant Variety in Zhejiang Province (2021C02067), the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences through the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAASASTIP-2017-TRICAAS), Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-19), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A20500).

Data Availability

The datasets presented for this study can be found in the Supplementary Materials and NCBI with the accession number PRJNA898859. The direct link for the NCBI database is https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/all/?term=PRJNA898859.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental research and field studies on plants in our study complies with Chinese institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. The planting and management of experimental materials are permitted by the Tea Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Liang Chen, Email: liangchen@tricaas.com.

Jianqiang Ma, Email: majianqiang@tricaas.com.

References

- 1.Feng K, Hou XL, Xing GM, Liu JX, Duan AQ, Xu ZS, Li MY, Zhuang J, Xiong AS. Advances in AP2/ERF super-family transcription factors in plant. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2020;40(6):750–76. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2020.1768509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu ZS, Chen M, Li LC, Ma YZ. Functions and application of the AP2/ERF transcription factor family in crop improvement. J Integr Plant Biol. 2011;53(7):570–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jofuku KD, Boer GWB, Van Montagu M, Okamuro JK. Control of Arabidopsis flower and seed development by the homeotic gene APETALA2. Plant Cell. 1994;6(9):1211–25. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamuro JK, Caster B, Villarroel R, Van Montagu M, Jofuku KD. The AP2 domain of APETALA2 defines a large new family of DNA binding proteins in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(13):7076–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riechmann JL, Meyerowitz EM. The AP2/EREBP family of plant transcription factors. Biol Chem. 1998;379(6):633–46. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.6.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakuma Y, Liu Q, Dubouzet JG, Abe H, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. DNA-binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of Arabidopsis DREBs, transcription factors involved in dehydration- and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290(3):998–1009. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakano T, Suzuki K, Fujimura T, Shinshi H. Genome-wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol. 2006;140(2):411–32. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.073783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, Reuber L, Jiang CZ, Keddie J, Adam L, Pineda O, Ratcliffe OJ, Samaha RR, et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290(5499):2105–10. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui Y, Bian J, Guan Y, Xu F, Han X, Deng X, Liu X. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiles of ethylene signal genes and apetala2/ethylene-responsive factors in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L) Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:828482. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.828482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhuang J, Peng RH, Cheng ZM, Zhang J, Cai B, Zhang Z, Gao F, Zhu B, Fu XY, Jin XF, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the putative AP2/ERF family genes in Vitis vinifera. Sci Hortic. 2009;123(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2009.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhuang J, Cai B, Peng RH, Zhu B, Jin XF, Xue Y, Gao F, Fu XY, Tian YS, Zhao W, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371(3):468–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Licausi F, Ohme-Takagi M, Perata P. APETALA2/Ethylene Responsive Factor (AP2/ERF) transcription factors: mediators of stress responses and developmental programs. New Phytol. 2013;199(3):639–49. doi: 10.1111/nph.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie Z, Nolan TM, Jiang H, Yin Y. AP2/ERF transcription factor regulatory networks in hormone and abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:228. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banno H, Ikeda Y, Niu QW, Chua NH. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ESR1 induces initiation of shoot regeneration. Plant Cell. 2001;13(12):2609–18. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandler JW, Cole M, Flier A, Grewe B, Werr W. The AP2 transcription factors DORNRÖSCHEN and DORNRÖSCHEN-LIKE redundantly control Arabidopsis embryo patterning via interaction with PHAVOLUTA. Development. 2007;134(9):1653–62. doi: 10.1242/dev.001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirch T, Simon R, Grünewald M, Werr W. The DORNRÖSCHEN/ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION1 gene of Arabidopsis acts in the control of meristem cell fate and lateral organ development. Plant Cell. 2003;15(3):694–705. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuo N, Banno H. The Arabidopsis transcription factor ESR1 induces in vitro shoot regeneration through transcriptional activation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008;46(12):1045–50. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvi S, Sponza G, Morgante M, Tomes D, Niu X, Fengler KA, Meeley R, Ananiev EV, Svitashev S, Bruggemann E, et al. Conserved noncoding genomic sequences associated with a flowering-time quantitative trait locus in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(27):11376–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704145104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anh Tuan P, Bai S, Saito T, Imai T, Ito A, Moriguchi T. Involvement of EARLY BUD-BREAK, an AP2/ERF transcription factor gene, in bud break in Japanese pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) lateral flower buds: expression, histone modifications and possible target genes. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57(5):1038–47. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azeez A, Zhao YC, Singh RK, Yordanov YS, Dash M, Miskolczi P, Stojkovič K, Strauss SH, Bhalerao RP, Busov VB. EARLY BUD-BREAK 1 and EARLY BUD-BREAK 3 control resumption of poplar growth after winter dormancy. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1123. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21449-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busov V, Carneros E, Yakovlev I. EARLY BUD-BREAK1 (EBB1) defines a conserved mechanism for control of bud-break in woody perennials. Plant Signaling Behav. 2016;11(2):e1073873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Yordanov YS, Ma C, Strauss SH, Busov VB. EARLY BUD-BREAK 1 (EBB1) is a regulator of release from seasonal dormancy in poplar trees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(27):10001–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405621111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao X, Wen B, Li C, Tan Q, Liu L, Chen X, Li L, Fu X. Overexpression of the peach transcription factor early bud-break 1 leads to more branches in poplar. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:681283. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.681283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koyama T, Nii H, Mitsuda N, Ohta M, Kitajima S, Ohme-Takagi M, Sato F. A regulatory cascade involving class II ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR transcriptional repressors operates in the progression of leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 2013;162(2):991–1005. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.218115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan XL, Fan ZQ, Shan W, Yin XR, Kuang JF, Lu WJ, Chen JY. Association of BrERF72 with methyl jasmonate-induced leaf senescence of Chinese flowering cabbage through activating JA biosynthesis-related genes. Hortic Res. 2018;5:22. doi: 10.1038/s41438-018-0028-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu ZJ, Li XH, Liu ZW, Li H, Wang YX, Zhuang J. Transcriptome-based discovery of AP2/ERF transcription factors related to temperature stress in tea plant ( Camellia sinensis ) Funct Integr Genomics. 2015;15(6):741–52. doi: 10.1007/s10142-015-0457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen LB, Fang C, Wang Y, Li YY, Jiang CJ, Liang MZ. Cloning and expression analysis of stress-resistant ERF genes from tea plant [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze] J Tea Sci. 2011;31(1):53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen LB, Li YY, Wang Q, Gao YL, Jiang CJ. Cloning and expression analysis of RAV gene related to cold stress from tea plant [ Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntz] Plant Physiol Commun. 2010;46(4):354–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z, Wu Z, Li X, Li T, Zhuang J. Gene cloning of CsDREB-A1 transcription factor from Camellia sinensis and its characteristic analysis. J Plant Resour Environ. 2014;23(4):8–16.

- 30.Liu ZW, Xiong YY, Li T, Yan YJ, Han HR, Wu ZJ, Zhuang J. Isolation and expression profiles analysis of two ERF subfamily transcription factor genes under temperature stresses in Camellia sinensis. Plant Physiol J. 2014;50(12):1821–32.

- 31.Tan L, Wang L, Zhou B, Liu Q, Chen S, Sun D, Zou Y, Chen W, Li P, Tang Q. Comparative transcriptional analysis reveled genes related to short winter-dormancy regulation in Camellia sinensis. Plant Growth Regul. 2020;92(2):401–15. doi: 10.1007/s10725-020-00649-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang XC, Ma CL, Yang YJ, Jin JQ, Ma JQ, Cao H. cDNA cloning and expression analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase ( CsCDK ) gene in tea plant. Acta Hortic Sinica. 2012;39(2):333–42. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang XC, Ma CL, Yang YJ, Cao HL, Hao XY, Jin JQ. Expression analysis of auxin-related genes at different winter dormant stages of axillary buds in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) J Tea Sci. 2012;32(6):509–16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, Liu Y, Sun L, Wang L, Zeng J, Yang Y, Wang X, Wei C, Hao X. Cloning of CsAIL in tea plant and its expression analysis during winter dormancy transition. Acta Hortic Sinica. 2019;46(2):385–96. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang W. Correlation between bud dormancy and CsDAM gene expression in tea varieties. Master thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. 2020.

- 36.Hao X, Chao W, Yang Y, Horvath D. Coordinated expression of FLOWERING LOCUS T and DORMANCY ASSOCIATED MADS-BOX-Like genes in leafy spurge. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0126030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lang GA, Early JD, Martin GC, Darnell RL. Endo-, para-, and ecodormancy: physiological terminology and classification for dormancy research. HortScience. 1987;22(5):701. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.22.5.701b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh RK, Svystun T, AlDahmash B, Jönsson AM, Bhalerao RP. Photoperiod- and temperature-mediated control of phenology in trees - a molecular perspective. New Phytol. 2017;213(2):511–24. doi: 10.1111/nph.14346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia E, Tong W, Hou Y, An Y, Chen L, Wu Q, Liu Y, Yu J, Li F, Li R, et al. The reference genome of tea plant and resequencing of 81 diverse accessions provide insights into its genome evolution and adaptation. Mol Plant. 2020;13(7):1013–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang D, Mao Y, Guo G, Ni D, Chen L. Genome-wide identification of PME gene family and expression of candidate genes associated with aluminum tolerance in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). BMC Plant Biol. 2022;22(1):306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Zhao H, Mallano AI, Li F, Li P, Wu Q, Wang Y, Li Y, Ahmad N, Tong W, Li Y, et al. Characterization of CsWRKY29 and CsWRKY37 transcription factors and their functional roles in cold tolerance of tea plant. Beverage Plant Res. 2022;2:15.

- 42.Li X, Tao S, Wei S, Ming M, Huang X, Zhang S, Wu J. The mining and evolutionary investigation of AP2/ERF genes in pear (Pyrus) BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1265-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Q, Zhang L, Chen P, Wu C, Zhang H, Yuan J, Zhou J, Li X. Genome-wide identification of APETALA2/ETHYLENE RESPONSIVE FACTOR transcription factors in Cucurbita moschata and their involvement in ethylene response. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:847754. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.847754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hao X, Yang Y, Yue C, Wang L, Horvath DP, Wang X. Comprehensive transcriptome analyses reveal differential gene expression profiles of Camellia sinensis axillary buds at para-, endo-, ecodormancy, and bud flush stages. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:553. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuskan GA, Difazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Ralph S, Rombauts S, Salamov A, et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray) Science. 2006;313(5793):1596–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mattick JS. Introns: evolution and function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4(6):823–31. doi: 10.1016/0959-437X(94)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu M, Sun W, Ma Z, Zheng T, Huang L, Wu Q, Zhao G, Tang Z, Bu T, Li C, et al. Genome-wide investigation of the AP2/ERF gene family in tartary buckwheat (Fagopyum Tataricum) BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1681-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao M, Haxim Y, Liang Y, Qiao S, Gao B, Zhang D, Li X. Genome-wide investigation of AP2/ERF gene family in the desert legume Eremosparton songoricum: identification, classification, evolution, and expression profiling under drought stress. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:885694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Gregorio J, Hernández-Bernal AF, Cordoba E, León P. Characterization of evolutionarily conserved motifs involved in activity and regulation of the ABA-INSENSITIVE (ABI) 4 transcription factor. Mol Plant. 2014;7(2):422–36. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding J, Nilsson O. Molecular regulation of phenology in trees-because the seasons they are a-changin’. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;29:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horvath DP, Anderson JV, Chao WS, Foley ME. Knowing when to grow: signals regulating bud dormancy. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8(11):534–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Franklin KA. Light and temperature signal crosstalk in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12(1):63–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rohde A, Bhalerao RP. Plant dormancy in the perennial context. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12(5):217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hao X. Studies on the molecular mechanism of winter bud dormancy in tea plant (Camellia Sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze). PhD thesis, Northwest A&F University. 2015.

- 55.Basler D, Körner C. Photoperiod and temperature responses of bud swelling and bud burst in four temperate forest tree species. Tree Physiol. 2014;34(4):377–88. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpu021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brunner AM, Evans LM, Hsu CY, Sheng X. Vernalization and the chilling requirement to exit bud dormancy: shared or separate regulation? Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:732. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cooke JEK, Eriksson ME, Junttila O. The dynamic nature of bud dormancy in trees: environmental control and molecular mechanisms. Plant, Cell Environ. 2012;35(10):1707–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Man R, Lu P, Dang QL. Insufficient chilling effects vary among boreal tree species and chilling duration. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1354. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang XC, Zhao QY, Ma CL, Zhang ZH, Cao HL, Kong YM, Yue C, Hao XY, Chen L, Ma JQ, et al. Global transcriptome profiles of Camellia sinensis during cold acclimation. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:415. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang B, Cao HL, Huang YT, Hu YR, Qian WJ, Hao XY, Wang L, Yang YJ, Wang XC. Cloning and expression analysis of auxin efflux carrier gene CsPIN3 in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) Acta Agron Sinica. 2016;42(1):58–69. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2016.00058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hao XY, Cao HL, Yang YJ, Wang XC, Ma CL, Xiao B. Cloning and expression analysis of auxin response factor gene (CsARF1) in tea plant (Camellia sinensis [L.] O. Kuntze) Acta Agron Sinica. 2013;39(3):389–97. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2013.00389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ikeda Y, Banno H, Niu QW, Howell SH, Chua NH. The ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION 2 gene in Arabidopsis regulates CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 1 at the transcriptional level and controls cotyledon development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47(11):1443–56. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dewitte W, Riou-Khamlichi C, Scofield S, Healy JMS, Jacqmard A, Kilby NJ, Murray JAH. Altered cell cycle distribution, hyperplasia, and inhibited differentiation in Arabidopsis caused by the D-type cyclin CYCD3. Plant Cell. 2003;15(1):79–92. doi: 10.1105/tpc.004838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karlberg A, Bako L, Bhalerao RP. Short day-mediated cessation of growth requires the downregulation of AINTEGUMENTALIKE1 transcription factor in hybrid aspen. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(11):e1002361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xia EH, Li FD, Tong W, Li PH, Wu Q, Zhao HJ, Ge RH, Li RP, Li YY, Zhang ZZ, et al. Tea plant information archive: a comprehensive genomics and bioinformatics platform for tea plant. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17(10):1938–53. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mistry J, Chuguransky S, Williams L, Qureshi M, Salazar GA, Sonnhammer ELL, Tosatto SCE, Paladin L, Raj S, Richardson LJ, et al. Pfam: the protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D412–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marchler-Bauer A, Bryant SH. CD-Search: protein domain annotations on the fly. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W327–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Artimo P, Jonnalagedda M, Arnold K, Baratin D, Csardi G, Castro ED, Duvaud S, Flegel V, Fortier A, Gasteiger E, et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Jin J, Tian F, Yang DC, Meng YQ, Kong L, Luo J, Gao G. PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D1040–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, He J, Lanczycki CJ, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, et al. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D200–3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:W293–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen JD, He WZ, Chen S, Chen QY, Ma JQ, Jin JQ, Ma CL, Moon DG, Ercisli Sezai, Yao MZ, Chen L. TeaGVD: a comprehensive database of genomic variations for uncovering the genetic architecture of metabolic traits in tea plants. Front in Plant Sci. 2022;13:1056891. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1056891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kersey PJ, Allen JE, Allot A, Barba M, Boddu S, Bolt BJ, Carvalho-Silva D, Christensen M, Davis P, Grabmueller C, et al. Ensembl Genomes 2018: an integrated omics infrastructure for non-vertebrate species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D802–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinf. 2010;8(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(10)60008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu B, Jin J, Guo AY, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(8):1296–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bailey TL, Johnson J, Grant CE, Noble WS. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W39–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, Rouzé P, Rombauts S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):325–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-∆∆CT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Ideker T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(3):431–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented for this study can be found in the Supplementary Materials and NCBI with the accession number PRJNA898859. The direct link for the NCBI database is https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/all/?term=PRJNA898859.