Abstract

Objective: To investigate the usefulness of the combination of neurological findings and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a prognostic predictor in patients with motor complete cervical spinal cord injury (CSCI) in the acute phase.

Design: A cross-sectional analysis

Setting: Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Spinal Injuries Center

Participants/Methods: Forty-two patients with an initial diagnosis of motor complete CSCI (AIS A, n = 29; AIS B, n = 13) within 72 h after injury were classified into the recovery group (Group R) and the non-recovery group (Group N), based on the presence or absence of motor recovery (conversion from AIS A/B to C/D) at three months after injury, respectively. The Neurological Level of Injury (NLI) at the initial diagnosis was investigated and the presumptive primary injured segment of the spinal cord was inferred from MRI performed at the initial diagnosis. We investigated whether or not the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI exceeded one segment. The presence of a difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI was compared between Groups R and N.

Results: The number of cases with the differences between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI was significantly higher in Group N than in Group R.

Conclusion: The presence of differences between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI might be a poor improving prognostic predictor for motor complete CSCI. The NLI may be useful for predicting the recovery potential of patients with motor complete CSCI when combined with the MRI findings.

Keywords: Cervical spinal cord injury, Neurological level of injury, Motor complete spinal cord injury, Prognostic predictor, Ascending myelopathy

Introduction

Spontaneous improvement of traumatic cervical spinal cord injury (CSCI) can be seen in the natural course.1 Spontaneous improvement can also be seen in patients with initially complete CSCI at a certain rate. El Tecle et al. reported that the overall rate of conversion of the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) A SCIs from pooled data of prospective trials and observational series which reported outcomes at 1 year following injury was 28.1%.2 Mori et al. reported that even among patients with complete motor paralysis caused by cervical SCI without bone and disc injury within 72 h after trauma, approximately 30% of those with an AIS A and 85% of the patients with an AIS B improved neurologically at 6 months after conservative treatment.3 Although it is important to accurately assess whether neurological improvement in initially complete CSCI patients is due to intervention or spontaneous recovery, it is very difficult to perform a strict assessment.

There are many reports on the prognosis of CSCI.2–20 Most discuss the rate of motor recovery in motor complete CSCI or the rate of recovery in cases of complete CSCI. We previously reported that 96.8% of the patients with <50% T1-weighted low-intensity area of spinal cord at the subacute stage recovered to walk at discharge.18 There was a significant relationship between the antero-posterior diameter ratio of the T1-weighted low-intensity area on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the subacute stage and the ASIA motor score. Moreover, we reported neurologic prognosis was correlated with MRI after 2–3 days after injury.19 If the vertical diameter of T2 high-intensity area of spinal cord was <45 mm, the patients were walk with or without cane at discharge. In these reports, we recognized that there were limitations in the prognostic prediction based on MRI alone. Because the spread of the high-intensity area of the spinal cord on T2-weighted sagittal MRI changes over time, there may be minor differences in the prognostic prediction depending on the timing at which MRI was performed.19 Furthermore, the size of the low-intensity area on T1-weighted imaging is not clear up to the chronic phase.18 Thus, the ability to predict the prognosis in the acute phase based on MRI alone is limited.

The worksheet of assessing spinal cord injury (SCI) made by the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) evaluates both the grade and level of SCI by examining the motor and sensory functions.21,22 The grade of SCI is expressed in accordance with ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS), while the level of SCI is expressed as the Neurological Level of Injury (NLI). The predominant tool used to predict outcomes after traumatic SCI is the ISNCSC. Although the ISNCSCI provide a detailed assessment of the severity of SCI, it merely describes the neurological status at the time of the examination, without necessarily indicating the prognosis of each patient. Khorasanizadeh et al. reported how neurological recovery after TSCI was significantly dependent on injury factors (i.e. severity, level, and mechanism of injury), but was not associated with the type of treatment or country of origin.23 They stated that a method of predicting the prognosis of an individual patient in the acute phase may be useful in establishing whether or not outcomes are influenced by a particular intervention and aiding in predicting the prognosis of the injury.

The ISNCSCI worksheet originally only represents the neurological status for individual patients at the time of the evaluation. We thus considered combining the ISNCSCI worksheet with the MRI findings, which are usually obtained at the initial diagnosis, for the purpose of examining its utility as a prognostic predictor for motor complete CSCI. The present study investigated whether or not the combination of the neurological findings by the ISNCSCI worksheet and the MRI findings at the initial diagnosis could be used to judge the recovery potential of individual patients with motor complete CSCI in the acute phase.

Methods

The present study included patients with traumatic CSCI who received an initial diagnosis within 72 h after injury from 2014 to 2019, and who exhibited motor complete CSCI (AIS A, B) at the initial diagnosis and skeletal levels of C4/5 to C6/7. We have decided on AIS A/B as the inclusion criteria, because almost all patients with motor complete SCI are concerned about whether or not their ability to walk will recover. We tried to detect poor prognostic predictors of motor recovery from motor complete CSCI (AIS A/B) to motor incomplete CSCI (AIS C/D). C3/4 skeletal level injury cases were excluded because the C5 segment of the spinal cord is considered to be at the C3/4 skeletal level, and no key muscle is defined above the C5 segment of the spinal cord. C7/T1 skeletal level injury cases were also excluded, as many did not have any upper extremity symptoms. All patients underwent treatment at our hospital alone from the acute phase (within 72 h after injury) to the chronic phase. Records were retrospectively collected from an investigation of our institute's database. We extracted the neurological data at the time of the initial diagnosis within 72 h and at 3 months. All patients who received an initial diagnosis within 72 h after injury had MRI performed at the same time as the initial diagnosis. All MRI findings were reviewed by all authors of the current study at the trauma case conference of our institute.

The study included 42 patients: 29 patients with AIS A (22 with bone injury and 7 without bone injury) and 13 patients with AIS B (7 with bone injury and 6 without bone injury). Of the 29 patients with AIS A, 22 were men, 7 were women, and their mean age was 54.6 (range 18-74) years old. Of the 13 patients with AIS B, 10 were men, 3 were women, and their mean age was 57.4 (range 17-87) years old. The timing of the initial diagnosis (ISNCSCI examination and MRI) was as follows; 21 patients with AIS A and 7 patients with AIS B received a diagnosis within 24 h after injury, 7 patients with AIS A and 5 patients with AIS B received a diagnosis within 48 h after injury, 1 patient with AIS A and 1 patient with AIS B received a diagnosis within 72 h after injury. The demographics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the study population.

| AIS A | AIS B | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 29 | 13 |

| w bone injury | 22 | 7 |

| w/o bone injury | 7 | 6 |

| Mean age in years (range) | 54.6 (18–74) | 57.4 (17–87) |

| Sex (male/female) | 22/7 | 10/3 |

| Timing of initial ISNCSCI & MRI (hours after injury) |

||

| <24 | 21 | 7 |

| 24–48 | 7 | 5 |

| 48–72 | 1 | 1 |

| Skeletal level of injury | ||

| C4/5 | 8 | 1 |

| C5/6 | 11 | 6 |

| C6/7 | 10 | 6 |

These patients were classified into two groups based on the functional status at three months after injury: the non-recovery group (Group N), in which no motor recovery was observed; and the recovery group (Group R), in which motor recovery (conversion from AIS A/B to C/D) was observed. Because recovery from paralysis is hardly expected beyond eight weeks after injury,17 the time point of three months after injury was set as the point for evaluating the prognosis. As a result, Group N (remained with AIS A/B) included 28 patients, and Group R (recovered to AIS C/D) included 14 patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Conversion of AIS grade at 3 months after injury.

| AIS grade | AIS grade (3 months after injury) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Initial diagnosis) | A | B | C | D |

| A | 21 | 5 | 3 | |

| B | 2 | 9 | 2 | |

We inferred the presumptive primary injured segment of the spinal cord from the high-intensity area of the spinal cord on T2-weighted sagittal MRI at the initial diagnosis. With respect to the high-intensity area of the spinal cord, in cases with bone injury, such as fracture or dislocation, all cases coincided with the affected skeletal (intervertebral) level, and in cases without bone injury, the intervertebral level with the highest-intensity area of the spinal cord on T2-weighted sagittal MRI was inferred to be the injured segment of the spinal cord. By referencing Kokubun's report24 and other supporting reports,25,26 the presumptive primary injured segment of the spinal cord was defined as follows: C4/5 intervertebral injury affected the C6 segment of the spinal cord; C5/6 intervertebral injury affected the C7 segment of the spinal cord; and C6/7 intervertebral injury affected the C8 segment of the spinal cord. The AIS grade and NLI were obtained from the ISNCSCI examination at the initial diagnosis within 72 h after injury and at 3 months after injury. The authors of the current study performed the examination.

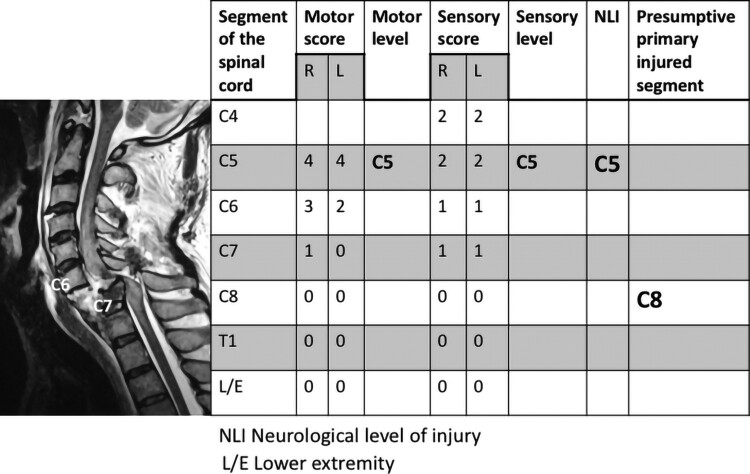

It was assumed that if the primary injury of the spinal cord was mild, the damage to the spinal cord and spread of secondary injury would be limited, with the NLI likely indicating the rostral segment of the spinal cord, just adjacent to the primary injured segment. We investigated whether or not the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI exceeded one segment (Fig. 1). If the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI exceeded one segment, the case was defined as having NLI-gap. The rate of patients with NLI-gap was compared between Groups R and N. In addition, the correlation between the presence of NLI-gap and the rate of patients with or without bone injury was investigated.

Figure 1.

Case presentation: C6/7 skeletal level injury with NLI-gap. The presumptive primary injured segment was determined to be the C8 segment of the spinal cord, as the skeletal level of injury was C6/7, which is estimated to affect the C8 segment of the spinal cord. Given the neurological findings, the NLI was determined to be C5. Since the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI exceeded one segment, this case was considered to have NLI-gap. If the NLI had been C7, then the case would have been considered to not have NLI-gap.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Chi-square test to compare Groups R and N and the rates of patients with or without bone injury. Significance was set at a value of P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP 13 software program (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

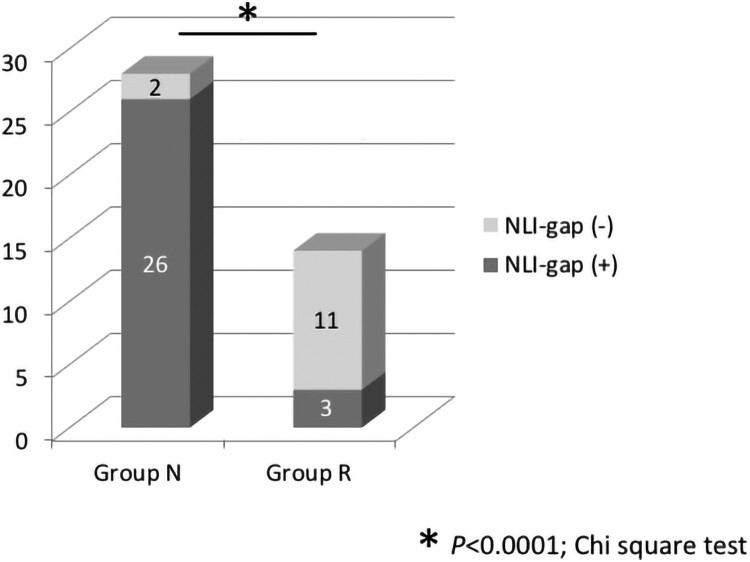

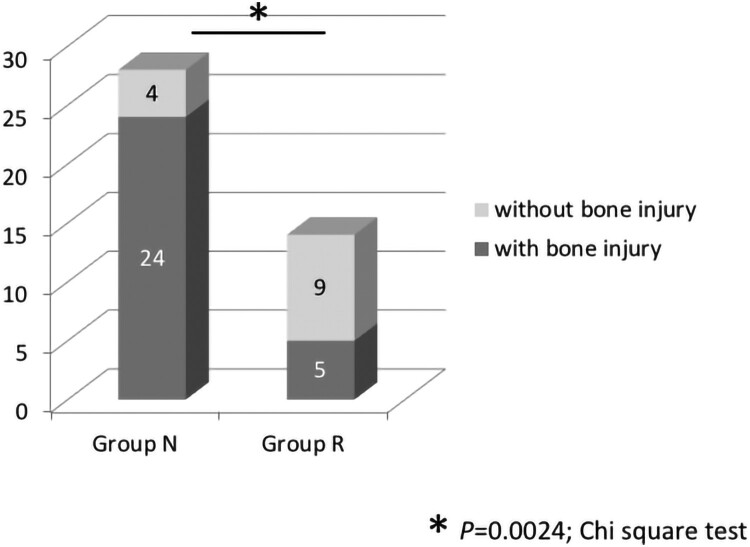

NLI-gap was detected in 26 of 28 cases (92.9%) in Group N and 3 of 14 cases (21.4%) in Group R. The rate of patients with NLI-gap was significantly higher in Group N than in Group R (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). A summary of the cases with NLI-gap in Groups N and R is shown in Table 3. Each group was subdivided according to the AIS grade and presence or absence of bone injury. Bone injury was noted in 24 of 28 cases (85.7%) in Group N, and 5 of 14 cases (35.7%) in Group R, which was a statistically significant difference (P = 0.0024) (Fig. 3). Both the rate of patients with NLI-gap and the rate of patients with bone injury were significantly higher in Group N than in Group R. The presence of NLI-gap tended to be slightly useful in comparison with the presence of bone injury as a poor prognostic predictor of motor complete CSCI (the presence of NLI-gap: P < 0.0001; odd ratio, 47.667; 95% confidence interval, 7.510–296.962, the presence of bone injury: P = 0.0024; odd ratio, 10.800; 95% confidence interval, 2.456–47.585) (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Rate of NLI-gap in Groups N and R. NLI-gap was noted in 26 of 28 cases (92.9%) in Group N and 3 of 14 cases (21.4%) in Group R. The rate of patients with NLI-gap was significantly higher in Group N than in Group R. *P < 0.0001, Chi-square test.

Table 3.

A summary of the cases with NLI-gap in Groups N and R, which each group was subdivided according to the AIS grade and presence or absence of bone injury.

| Difference | NLI-gap | Group N | Group R | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIS | A | B | A | B | ||||||

| Bone injury | w | w/o | w | w/o | w | w/o | w | w/o | ||

| 3 2 |

presence | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |||

| 1 | absence | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | |

Note: Difference the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI. w, with, w/o, without.

Figure 3.

Rate of bone injury in Groups N and R. Bone injury was noted in 24 of 28 cases (85.7%) in Group N, and 5 of 14 cases (35.7%) in Group R. The rate of patients with bone injury was significantly higher in Group N than in Group R. *P = 0.0024, Chi-square test.

Table 4.

Results of the simple logistic regression in the poor prognostic predictor of motor complete CSCI.

| P Value | Odd ratio | 95% Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLI-gap | <0.0001 | 47.667 | 7.510–296.962 |

| Bone injury | 0.0024 | 10.800 | 2.456–47.585 |

Note: The presence of NLI-gap tended to be more useful than the presence of bone injury as a poor prognostic predictor of motor complete CSCI according to a simple logistic regression analysis.

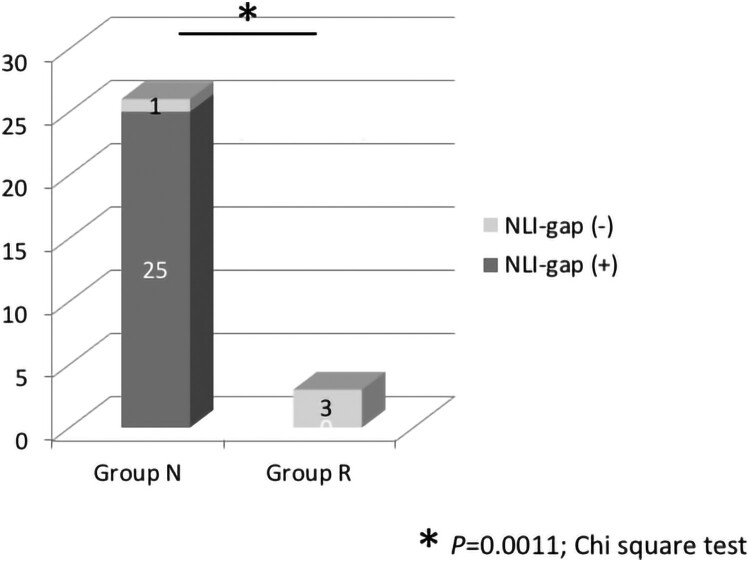

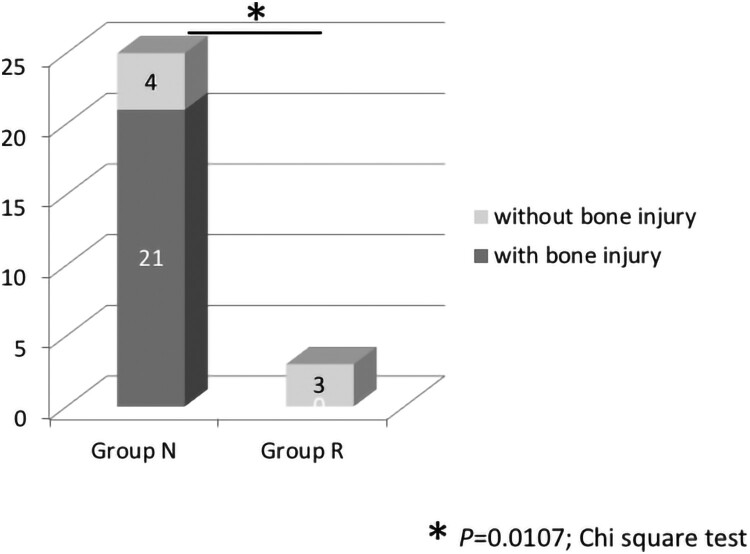

We also analyzed the subgroup of only initially AIS A patients. NLI-gap was detected in 25 of 26 cases (96.2%) in Group N and 0 of 3 cases (0.0%) in Group R. The rate of patients with NLI-gap was significantly higher in Group N than in Group R (P = 0.0011) (Fig. 4). Bone injury was noted in 21 of 25 cases (84.0%) in Group N, and 0 of 3 cases (0.0%) in Group R, showing a statistically significant difference (P = 0.0107) (Fig. 5). A similar tendency was observed in the group with AIS A alone and the group with AIS A/B.

Figure 4.

Rate of NLI-gap in Groups N and R in the initially AIS A patients. NLI-gap was detected in 25 of 26 cases (96.2%) in Group N and 0 of 3 cases (0.0%) in Group R. The rate of patients with NLI-gap was significantly higher in Group N than in Group R. *P = 0.0011, Chi-square test.

Figure 5.

Rate of bone injury in Groups N and R in the initially AIS A patients. Bone injury was noted in 21 of 25 cases (84.0%) in Group N, and 0 of 3 cases (0.0%) in Group R, showing a statistically significant difference. *P = 0.0107, Chi-square test.

Discussion

It is difficult to assess the recovery potential in individual patient with complete CSCI in the acute phase. With respect to the prognostic predictors of SCI, while there have been reports indicating the possibility of recovery based on the AIS in the acute phase as a percentage of the whole2,3,7,11–13,15,17 or the prediction of recovery using finding from MRI18,19 and other imaging modalities, there are few reports concerning predictors indicating whether or not an individual patient will be able to recover. Aarabi et al. reported that intramedullary lesion length on MRI is a strong predictor of AIS conversion.27 Because they used postoperative MRI to predict prognosis, the results may not reflect the true prognosis of SCI. Morishita et al. reported that motor recovery could be expected in a very high percentage of patients with patellar tendon reflex (PTR) within 72 h of injury.20 In addition, they emphasized that, as all physicians should be familiar with the PTR, this seems to be a simple and extremely useful sign for predicting improvement of motor paralysis during the acute stage of CSCI.

A simple and familiar method of predicting the prognosis of an individual patient in the acute phase may be useful for judging whether or not outcomes are influenced by a particular intervention. In the present study, we investigated whether or not the combination of the neurological findings by the ISNCSCI worksheet and the MRI findings at the initial diagnosis could be used to judge the recovery potential of individual patients with motor complete CSCI in the acute phase. Because the ISNCSCI worksheet for individual patients only reflects the neurological status at the time of the evaluation, we attempted to combine the ISNCSCI worksheet with the MRI findings, which are usually obtained at the initial diagnosis, in order to examine the potential utility of this combination as a prognostic predictor for motor complete CSCI.

SCI is usually initiated by the primary mechanical injury followed by secondary injury which includes many factors (e.g. vascular compromise, loss of vascular autoregulation, capillary destruction, loss of microcirculation, vasospasm, thrombosis, and hemorrhage) to lead to tissue destruction over the ensuring hours, days, and weeks. First, the presumptive primary injured segment of the spinal cord was inferred from the high-intensity area of the spinal cord on T2-weighted sagittal MRI at the initial diagnosis, while the NLI was automatically decided according to the ISNCSCI worksheet at the initial diagnosis. It was assumed that if the primary injury of the spinal cord was mild, the damage to the spinal cord and spread of secondary injury would be limited, with the NLI likely indicating the rostral segment of the spinal cord, just adjacent to the primary injured segment; the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI should be one segment. If this difference exceeded one segment, then the damage of the spinal cord could be expected to be severe with a poor potential for recovery from paralysis. We considered this difference to be the magnitude of the secondary injury, indicating ascending myelopathy.

The results of the present study support this hypothesis, indicating that patients with NLI-gap had a significantly lower recovery rate from motor complete CSCI than those without it. Furthermore, the significance of differences was greater in the presence of NLI-gap than in the presence of bone injury. Many physicians may tend to think that the external force at the time of injury is greater in patients with bone injury than in those without bone injury and that the damage of the spinal cord is consequently greater as well.28 However, the presence or absence of bone injury does not always correspond to the magnitude of damage to the spinal cord. The present results suggest that the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI may be an indicator of the magnitude of spinal cord damage. Furthermore, the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI may reflect secondary injury or ascending myelopathy29 in the acute phase CSCI.

One issue with this study is how to determine the primary injured segment of the spinal cord. Although previous reports and studies suggest that the C6 segment of the spinal cord is located between the C4/5 intervertebral level, the C7 segment of the spinal cord between the C5/6 intervertebral level, and the C8 segment of the spinal cord between the C6/7 intervertebral level, there may be slight differences in the injured segment of the spinal cord, even among cases of the same intervertebral injury. These slight differences in the injured segment of the spinal cord, even in the same intervertebral injury, may be due to the mechanism of injury or due to individual differences. This issue appears to be a limitation inherent to the present study and similar future studies. The sample size and composition differences between groups (AIS A/B) are also significant limitations of the study. In addition, it may be necessary to combine NLI-gap with various other prognostic confounders (e.g. age, energy of trauma, time from injury to initial assessment, time from injury to MRI). Further analysis of the association with these various factors is needed.

However, the present findings suggest that the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI, which is taken to indicate the presence of NLI-gap, is a useful predictor of a poor prognosis of motor complete CSCI in the acute phase.

Conclusions

The primary injured segment of the spinal cord was inferred from MRI findings obtained at the initial diagnosis. We investigated whether or not the difference between the presumptive primary injured segment and the NLI exceeded one segment. The difference was defined as NLI-gap. The presence of NLI-gap indicated a poor recovery from motor complete CSCI. Conversely, patients without NLI-gap can generally be expected to recover from motor complete CSCI. In addition to represent the neurological level of spinal cord injury, the NLI may be useful for predicting the recovery potential of patients with motor complete CSCI when combined with the MRI findings.

Data archiving

Data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the inclusion of private information of patients but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Statement of ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Spinal Injuries Center. This article does not include any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all of the patients who were included in the present study.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors OK designed the studies, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. TK supervised the overall project. HS, MM, YM, TH, KK, KK, HK and KY performed the data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s). No funds were received in support of this work. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript..

Conflicts of interest Authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- 1.Curt A, Van Hedel HJA, Klaus D, Dietz V, EM-SCI Study Group . Recovery from a spinal cord injury: significance of compensation, neural plasticity, and repair. J Neurotrauma 2008;25:677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Tecle NE, Dahdaleh NS, Bydon M, Ray WZ, Torner JC, Hitchon PW.. The natural history of complete spinal cord injury: a pooled analysis of 1162 patients and a meta-analysis of modern data. J Neurosurg Spine 2018;28:436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori E, Ueta T, Maeda T, Ideta R, Yugue I, Kawano O, et al. Sequential neurological improvement after conservative treatment in patients with complete motor paralysis caused by cervical spinal cord injury without bone and disc injury. J Neurosurg Spine 2018;29:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steeves JD, Kramer JK, Fawcett JW, Cragg J, Lammertse DP, Blight AR, et al. Extent of spontaneous motor recovery after traumatic cervical sensorimotor complete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011;49:257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, Leo-Summers L, Aldrich EF, Fazl M, et al. Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the third national acute spinal cord injury randomized controlled trial. National acute spinal cord injury study. JAMA 1997;277:1597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, Leo-Summers L, Aldrich EF, Fazl M, et al. Methylprednisolone or tirilazad mesylate administration after acute spinal cord injury: 1-year follow up. Results of the third national acute spinal cord injury randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg 1998;89:699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fehlings MG, Vaccaro A, Wilson JR, Singh A, Cadotte DW, Harrop JS, et al. Early versus delayed decompression for traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: results of the surgical timing in acute spinal cord injury study (STASCIS). PLoS One 2012;7:e32037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geisler FH, Dorsey FC, Coleman WP.. Recovery of motor function after spinal-cord-injury –a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with GM-1 ganglioside. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1829–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Granger N, Blamires H, Franklin RJM, Jeffery ND.. Autologous olfactory mucosal cell transplants in clinical spinal cord injury: a randomized double-blinded trial in a canine translational model. Brain 2012;135:3227–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lima C, Pratas-Vital J, Escada P, Hasse-Ferreira A, Capucho C, Peduzzi JD.. Olfactory mucosa autografts in human spinal cord injury: a pilot clinical study. J Spinal Cord Med 2006;29:191–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papadopoulos SM, Selden NR, Quint DJ, Patel N, Gillespie B, Grube S.. Immediate spinal cord decompression for cervical spinal cord injury: feasibility and outcome. J Trauma 2002;52:323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaccaro AR, Daugherty RJ, Sheehan TP, Dante SJ, Cotler JM, Balderston RA, et al. Neurologic outcome of early versus late surgery for cervical spinal cord injury. Spine 1997;22:2609–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Middendrop JJ, Hosman AJF, Pouw MH, EM-SCI Study Group, Van de Meent H.. ASIA impairment scale conversion in traumatic SCI: is it related with the ability to walk? A descriptive comparison with functional ambulation outcome measures in 273 patients. Spinal Cord 2009;47:555–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer JL, Lammertse DP, Schubert M, Curt A, Steeves JD.. Relationship between motor recovery and independence after sensorimotor-complete cervical spinal cord injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2012;26:1064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zariffa J, Kramer JL, Fawcett JW, Lammertse DP, Blight AR, Guest J, et al. Characterization of neurological recovery following traumatic sensorimotor complete thoracic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011;49:463–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson JR, Cadotte DW, Fehlings MG.. Clinical predictors of neurological outcome, functional status, and survival after traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine 2012;17:11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawano O, Maeda T, Mori E, Takao Y, Sakai H, Masuda M, et al. How much time is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of permanent complete cervical spinal cord injury? Spinal Cord 2020;58:284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsushita A, Maeda T, Mori E, Yugue I, Kawano O, Ueta T, et al. Subacute T1-low intensity area reflects neurological prognosis for patients with cervical spinal cord injury without major bone injury. Spinal Cord 2016;54:24–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsushita A, Maeda T, Mori E, Yugue I, Kawano O, Ueta T, et al. Can the acute magnetic resonance imaging features reflect neurologic prognosis in patients with cervical spinal cord injury? Spine J 2017;17:1319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morishita K, Kasai Y, Ueta T, Shiba K, Akeda K, Uchida A.. Patellar tendon reflex as a predictor of improving motor paralysis in complete paralysis due to cervical cord injury. SpinalCord 2009;47:640–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A, et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (Revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med 2011;34:535–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Spinal Injuries Association . International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. Richmond (VA: ): American Spinal Injuries Association; Revised 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khorasanizadeh M, Yousefifard M, Eskian M, Lu Y, Chalangari M, Harrop JS, et al. Neurological recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury: a systemtic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Spine 2019;15:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kokubun S. [Neurological localization of the symptomatic level of lesion on cervical spondylotic myelopathy.] Rinsho Seikei Geka. 1984;19:417–424. (JPN).

- 25.Matsumoto M, Ishikawa M, Ishii K, Nishizawa T, Maruiwa H, Nakamura M, et al. Usefulness of neurological examination for diagnosis of the affected level in patients with cervical compressive myelopathy: prospective comparative study with radiological evaluation. J Neurosurg Spine 2005;2:535–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seichi A, Takeshita K, Kawaguchi H, Matsushita K, Higashikawa A, Ogata N, et al. Neurological level diagnosis of cervical stenotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;31:1108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aarabi B, Sansur CA, Ibrahimi DM, Simard JM, Hersh DS, Le E, et al. Intramedullary lesion length on postoperative magnetic resonance imaging is a strong predictor of ASIA impairment scale grade conversion following decompressive Surgery in cervical spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery 2017;80:610–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawano O, Maeda T, Mori E, Yugue I, Takao T, Sakai H, et al. Influence of spinal cord compression and traumatic force on the severity of cervical spinal cord injury associated with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine 2014;39:1108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada S, Saito T, Kawano O, Hayashida M, Matsumoto Y, Harimaya K, et al. Sequential changes of ascending myelopathy after spinal cord injury on magnetic resonance imaging: a case report of neurologic deterioration from paraplegia to tetraptegia. Spine J 2014;14:e9–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the inclusion of private information of patients but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.