Abstract

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease is projected to reach 13 million in the U.S. by 2050. Although major efforts have been made to avoid this outcome, so far there are no treatments that can stop or reverse the progressive cognitive decline that defines Alzheimer’s disease. The utilization of preventative treatment before significant cognitive decline has occurred may ultimately be the solution, necessitating a reliable biomarker of preclinical/prodromal disease stages to determine which older adults are most at risk. Quantitative cerebral blood flow is a promising potential early biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease, but the spatiotemporal patterns of altered cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer’s disease are not fully understood. The current systematic review compiles the findings of 81 original studies that compared resting gray matter cerebral blood flow in older adults with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease and that of cognitively normal older adults and/or assessed the relationship between cerebral blood flow and objective cognitive function. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease had relatively decreased cerebral blood flow in all brain regions investigated, especially the temporoparietal and posterior cingulate, while individuals with mild cognitive impairment had consistent results of decreased cerebral blood flow in the posterior cingulate but more mixed results in other regions, especially the frontal lobe. Most papers reported a positive correlation between regional cerebral blood flow and cognitive function. This review highlights the need for more studies assessing cerebral blood flow changes both spatially and temporally over the course of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as the importance of including potential confounding factors in these analyses.

Keywords: cerebral blood flow, neuroimaging, biomarker, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia; 60–80% of dementia cases are attributable to AD (Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, 2021). Both the prevalence and mortality rate of AD are increasing in the U.S. and globally, and there are no current treatments that can stop or reverse the progressive loss of cognitive function caused by AD (Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, 2021). Clinical trials of treatments targeting pathologic forms of amyloid-β and tau proteins in the brain have successfully reduced them but have been unable to stop the progression of cognitive decline (Zhu et al., 2020). In order to effectively treat AD, a preventative treatment administered before irreversible neuronal damage has occurred may be necessary (Zhu et al., 2020). An effective early biomarker for the identification of older adults who are most likely to develop AD is critical (Blennow & Zetterberg, 2018; Counts et al., 2017). The disease process of AD can begin decades before cognitive decline is apparent and can manifest as subjective cognitive decline (SCD) or mild cognitive impairment (MCI; Petersen et al., 1999; Petersen, 2016; Jessen et al., 2014; Jessen et al., 2020). MCI is a stage of decreased cognitive functioning measured on objective cognitive tests accompanied by the preserved ability to complete day-to-day activities (Petersen et al., 1999). SCD, during which individuals still perform in the normal range on objective cognitive tests but report a subjective decline from their normal cognitive state, has been described as an even earlier stage of AD (Jessen et al., 2014). An effective early biomarker for AD that can lead to preventative treatment must be able to distinguish individuals with SCD and MCI from normally aging individuals and from older adults experiencing cognitive changes due to other reasons, such as depression (Culpepper et. al., 2017).

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) is a potential early biomarker for AD. CBF is globally decreased in patients with AD compared to age-matched non-demented counterparts. It has been shown that CBF is altered in individuals with preclinical AD as well, and that patterns of altered CBF are correlated with disease severity and progression from one diagnostic stage to the next (Duan et al., 2021). Due to the brain’s sensitivity to changes in blood pressure, chronic hypertension leads to constriction of the cerebral vasculature. Additionally, blood vessels in the brain become more rigid with age, so the combination of chronic hypertension and aging lead to a hyper-constricted cerebral vasculature and ultimately chronically reduced CBF (Iadecola & Gottesman, 2019). Although the longstanding amyloid cascade hypothesis of AD posits that amyloid-β and its aggregation ultimately lead to the disease processes and outcomes in AD (Hardy & Higgins, 1992), the more recently suggested two-hit hypothesis states that cerebrovascular dysfunction and amyloid-β pathology culminate to initiate and propagate AD (Zlokovic, 2011).

CBF has been studied in the context of AD and other dementias for several decades and has been measured by a variety of neuroimaging methods over time. The first measurements of CBF in humans were made in 1948 using the inhalation of nitrous oxide and quantification of the inert gas in venous blood (Kety & Schmidt, 1948). In the 1960s, the use of radioactive tracers including krypton-85 and xenon-133 allowed for the measurement of regional as well as global CBF (Lassen & Ingvar, 1961; Lassen et al., 1963). The development of positron emission tomography (PET) soon led to the use of positron-emitting tracers, particularly oxygen-15, for CBF measurement (Jones et al., 1976). Dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE MRI) and dynamic susceptibility-contrast (DSC) MRI were developed around the same time as PET and utilized gadolinium-based contrast agents that had magnetic properties to trace and quantify CBF without the need for radioactive tracers (Edelman et al., 1990; Rempp et al., 1994; Maeda et al., 1993).

The most common methods of the studies included in this review are single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) and the more recently developed arterial spin labeled (ASL) MRI. SPECT requires the blood to be labeled with an injection of a radioactive tracer, such as iodine-123 or technetium-99m (Warwick, 2004). ASL MRI, on the other hand, is completely noninvasive. In ASL MRI, blood is labeled as it flows into the brain by inverting the magnetization of the water molecules in the blood and then comparing the labeled image to an unlabeled background image (Detre et al., 2012). ASL MRI can therefore be safely and comfortably used at multiple time points to monitor changes in CBF over the course of disease or treatment.

In order to utilize CBF as an early biomarker for AD, we need to better understand how CBF changes throughout the progression of AD, including in prodromal stages. The roles of other AD-related pathologies (amyloid-β, tau, gray matter atrophy, white matter hyperintensities), AD risk factors (apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 genotype, diabetes, hypertension, and other cardiovascular diseases), and demographic factors (age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, environmental risk factors) must also be taken into consideration when measuring CBF.

The purpose of this review is to consolidate the literature comparing CBF in older adults with MCI or AD and those that are cognitively normal (CN). Patterns of altered CBF are summarized using results from several brain regions. Results are also summarized for the relationship between cognitive exam scores and CBF in older adults. The aim is to compile and synthesize the results of the existing literature concerning altered CBF in MCI and AD. This is important because various methods of CBF measurement have been used over the years; standardization of results will help to clarify whether previous findings are consistent. A recently published review (Zhang et al., 2021) covers the same topic with a broader scope. It includes studies that measured CBF velocity, and it does not exclude articles based on the age of participants with AD. Zhang et al. (2021) did not include papers that report voxel-wise results in the form of z or t scores. The current review employs an age cutoff for the MCI and AD participants included because early onset AD, diagnosed before age 65, may be a different variant of AD; early onset AD patients tend to decline more rapidly and are more likely to have cognitive declines in areas other than memory as the initial symptoms. Therefore, we excluded papers where the mean age of MCI or AD participants minus two standard deviations (SDs) is less than 60, meaning that at least 97% of the individuals studied in each paper are at least 60 years old. This defines the overall population as mostly late onset. We also included papers that report voxel-wise results to assess their consistency with papers that report regional CBF values. A recent meta-analysis (Tang et al., 2022) assessed CBF measured by ASL MRI in individuals with MCI. Our review differs by including papers that measured CBF using a variety of imaging methods and by applying an age cutoff in our inclusion criteria.

The objective of this review is to assess the cumulative evidence of altered CBF in older adults with MCI and AD in multiple brain regions and of the relationship between CBF and cognitive exam scores in these individuals. We also aim to assess the consistency of findings across papers that use a variety of imaging, processing, and analytic methods. Our main question is one of correlation rather than causation between diagnosis and CBF. In reality, it is likely that AD pathologies and altered CBF exacerbate one another and have a cyclical relationship, and it is not clear which of the two is present first or whether both arise simultaneously from a common cause.

METHODS

This systematic review includes all studies in which resting gray matter CBF is compared between diagnostic groups (CN, MCI, AD) and/or correlated with cognitive exam scores. Only studies in which the mean age of MCI/AD patients minus two SDs is at least 60 years old are included. If there was not a SD listed for age of participants with MCI/AD, that paper was not eligible unless the minimum age was at least 60. We chose to use a cutoff for participant age so that a majority of the MCI/AD patients would be over the age of 60 and less likely to have early-onset variants of AD. Both observational studies and clinical trials that measured gray matter CBF at rest prior to treatment are included, as well as both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. Only manuscripts written in English were included. All manuscripts are published as original research papers or brief reports; conference abstracts were not included. There were no restrictions on the year of publication, and papers that used any established method for the quantification of CBF were eligible for inclusion. Studies that were ineligible either did not measure gray matter CBF at rest or did not use resting gray matter CBF as an outcome measure in multiple diagnostic groups and/or in comparison with cognitive test scores.

PubMed was searched on September 12, 2022, through the National Library of Medicine and with access via Indiana University School of Medicine. 2699 potential articles resulted from a PubMed search of “brain-blood supply” or “cerebrovascular circulation” and “mild cognitive impairment” or “Alzheimer’s disease” as MeSH terms. We did not specify article type or language in the initial PubMed search in order to be inclusive of all possibly relevant articles. The search terms were chosen from PubMed MeSH terms that broadly encompassed the intended key topics of CBF, MCI, and AD.

Due to the correlational nature of the research question, the “population, intervention, control, and outcomes” (PICO) method (Richardson et al., 1995) was not used. Unlike an intervention and outcome, CBF and MCI/AD do not have a clear causal relationship. Therefore, the design used for bias and certainty assessments was a case-control research question in which the condition was MCI/AD and the variable of interest was altered CBF.

For the main synthesis, we describe increase or decrease in CBF between AD and controls in several brain regions. Altered CBF in MCI relative to controls and correlations between CBF and cognitive test scores are described as well. For papers that present relevant data only in the form of a graph, we extracted quantitative data using WebPlotDigitizer version 4.5 (automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/). For articles that had a high potential of overlapping participant samples, the article with the higher quality rating (less risk for bias) was chosen.

The information recorded for each article includes: author(s), article title, year of publication, place of the study, number of participants, diagnostic groups, criteria by which diagnoses were defined, method used to measure and quantify CBF, ages of participants, whether the paper is included in the synthesis, and which outcomes were reported. To organize this information, we used a matrix from University of Maryland Research Guides (lib.guides.umd.edu/SR/steps).

To assess the risk of bias and the quality of each article, we used the NIH Quality Assessment of Case-Control Studies. The items on this tool are: clearly stated objective, clearly specified and defined population, sample size justification, use of same population for cases and controls, use of same inclusion and exclusion criteria for cases and controls, clearly defined and differentiated cases, random selection of sample from eligible individuals, use of concurrent controls, confirmation that exposure occurred prior to the condition, clearly defined and reliable measures of exposure/risk, blinded assessment of exposure/risk with regard to case/control, and use of matching or addition of confounding variables to statistical models. Overall judgments were “poor,” “fair,” or “good.” These decisions were made according to the guidance included in the tool, where it is explained that lack of some criteria correspond to “fatal flaws” while others do not greatly affect the overall quality of the paper. CBF was considered the “exposure,” and because the direction of causation between MCI/AD and altered CBF is outside the scope of this review, it was not relevant whether the exposure occurred prior to the condition. Therefore, this question was marked as “not applicable” and not used in the overall bias rating. Other items on the rating tool that were not used were: sample size justification, random selection of sample from eligible individuals, and use of concurrent controls, because these items were all either not present or not reported in all or nearly all papers assessed. In addition, blind assessment of the CBF was not applicable for many of the papers because the CBF was measured by fully automated methods. This item was considered for those papers in which hand-drawn regions of interest were used or in which investigators visually assessed CBF images.

For each relevant paper, we reported mean and SD of CBF in each brain region for each diagnostic group. For articles that used voxel-wise measurement of CBF and reported the z or t scores of peak voxels, these scores, along with cluster sizes (k) and p values are reported. For papers that measured the correlation between CBF and cognitive test scores, r and p values are reported. For papers with mean and SD regional CBF values, effect sizes were calculated, and syntheses were presented for multiple brain regions. To measure effect size, we used Hedge’s g, which is Cohen’s d adjusted for small sample sizes, as well as the 95% confidence interval for Hedge’s g. These effect size measures were chosen because CBF is a continuous measure that is dependent on the methods of scanning and processing, so standardized measures were necessary. Effect size was calculated for the difference in CBF between MCI/AD and control groups (control CBF minus MCI/AD CBF) in the following brain regions: frontal, temporal, parietal, temporoparietal, occipital, posterior cingulate, hippocampus, and thalamus. These regions were chosen because they were the most frequently used across all papers. Thresholds were not employed for the effect sizes; we synthesized results for each brain region across studies by reporting the average, median, and range of effect size scores in each region. All Hedge’s g values and 95% confidence intervals are presented in graphs; positive effect sizes denote relatively decreased CBF in MCI/AD. These analyses and graphs were completed using the Effect Size Calculator from the Cambridge Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring (https://www.cem.org/).

A meta-analysis was not performed. Heterogeneity is discussed where there is inconsistency in findings across papers, but statistical analyses regarding heterogeneity were not completed. Sensitivity analyses were also not completed. The scope of this paper is to compile and present the findings in the literature and to discuss overall patterns of results. Reporting bias was taken into account, and certainty ratings for each synthesis are presented in the summary of findings table. Grey literature was not included. Negative findings were included whenever they were reported. For the certainty assessment, we used the GRADE tool from the Cochrane handbook. Scores are “very low,” “low,” “moderate,” and “high.” Since this tool is designed for randomized clinical trials, it instructs the assessor to begin with “moderate” for observational or case-control studies. We rated each synthesis according to the rest of the GRADE criteria but did not strictly begin at “moderate” for each paper because, by design, most of the papers were not clinical trials.

RESULTS

Of 2699 potential articles resulting from a PubMed search of “brain-blood supply” or “cerebrovascular circulation” and “mild cognitive impairment” or “Alzheimer’s disease,” 1309 were retained for further assessment and 1390 were excluded based on their abstracts. Of those excluded, 745 were reviews, editorials, commentaries, case studies, and other types of articles that did not match the eligibility criteria. 381 used animal models or cell cultures rather than human participants, 101 were not in English, and access was not available for 163 articles. Of the 1309 retained, 81 articles were ultimately chosen for inclusion in this review, and 1228 were excluded. Of these, 285 sampled MCI/AD patients who were too young or whose ages were not clearly defined, 542 did not use resting CBF as an outcome, 207 did not compare CBF between diagnostic groups or correlate it with cognitive function, 166 did not include MCI/late onset AD or had mixed patient groups, and 28 were likely to have used the same sample as other articles included in this review. The process of choosing relevant articles is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of articles identified, assessed for eligibility, and included in systematic review. Reasons for exclusion are listed. Included papers compare resting CBF between AD/MCI and CN, include an AD sample where over 95% are 60 years old or older, and are written in English.

The excluded papers with potentially overlapping samples were: Hanyu et al. (2003a), Hanyu et al. (2003b), Hanyu et al. (2004), Hanyu et al. (2008a), Hanyu et al. (2008b), Sakai et al. (2013), Sakurai et al. (2013), and Hanyu et al. (2010; with Shimizu et al. [2005]), Haji et al. (2015) and Kimura et al. (2012; with Kimura et al. [2011]), Brown et al. (1997; with Brown et al. [1996]), Colloby et al. (2002; with Firbank et al. [2011]), Kawamura et al. (1991) and Mortel et al. (1994; with Obara et al. [1994]), Pearlson et al. (1992) and Harris et al. (1998; with Harris et al. [1991]), Hoyer (1991) and Hoyer (1993; with Hoyer, Nitsch and Oesterreich [1991]), Alegret et al. (2012; with Alegret et al. [2010]), Brugnolo et al. (2010; with Nobili et al. [2005]), Lacalle-Aurioles et al. (2014; with Lacalle-Aurioles et al. [2013]), Sase et al. (2018; with Sase et al. [2017]), Ishii et al. (1999; with Yamaji et al. [1997]), Dai et al. (2009) and Duan et. al. (2021; with Duan et al. [2020]), Yew and Nation (2017) and Camargo and Wang (2021; with Mattsson et al. [2014]), and Albrecht et. al. (2020; with Rubinski et al. [2021]).

Papers included in this review are listed and characterized in Supplementary Table 1. They include: Alegret et al. (2010), Alfini et al. (2019), Ashford et al. (2000), Bangen et al. (2012), Benoit et al. (2002), Brayet et al. (2017), Brown et al. (1996), Chaudhary et al. (2013), Claus et al. (1994), Colloby et al. (2016), DeKosky et al. (1990), Deo et al. (2014), Ding et al. (2014), Duan et al. (2020), Duran et al. (2007), Encinas et al. (2003), Firbank et al. (2003), Firbank et al. (2011), Germán et al. (2021), Habert et al. (2011), Hanyu et al. (2008), Harris et al. (1991), Hayashi et al. (2011), Hayashi et al. (2021), Houston et al. (1998), Hoyer (1991), Iizuka and Kameyama (2017), Imran et al. (1998), Ishiwata et al. (2006), Ito et al. (2013), Jagust et al. (1987), Johnson et al. (1988), Johnson et al. (2007), Kaneta et al. (2017), Keller et al. (2011), Kimura et al. (2011), Knapp et al. (1996), Komatani et al. (1988), Lacalle-Aurioles et al. (2013), Lajoie et al. (2017), Lee et al. (2003), Liu et al. (2015), Lobotesis et al. (2001), Lövblad et al. (2015), Mattsson et al. (2014), Mielke et al. (1994), Mitsumoto et al. (2009), Mubrin et al. (1989), Nagahama et al. (2003), Nobili et al. (2005), O’Mahony et al. (1996), Obara et al. (1994), Ottoy et al. (2019), Pappatà et al. (2010), Prohovnik et al. (1989), Quattrini et al. (2021), Rane et al. (2018), Rubinski et al. (2021), Sase et al. (2017), Schuff et al. (2009), Shimizu et al. (2005), Song et al. (2014), Sundström et al. (2006), Takahashi et al. (2019), Takano et al. (2020), Takenoshita et al. (2020), Tanaka et al. (2002), Tateno et al. (2008), Terada et al. (2013), Tokumitsu et al. (2021), Tosun et al. (2016), Tu et al. (2022), van de Haar et al. (2016), Wang et al. (2009), Warkentin et al. (2004), Xie et al. (2016), Yamaji et al. (1997), Yamashita et al. (2014), Yoshida et al. (2011), Yoshida et al. (2017), and Zurynski et al. (1989). Supplementary Table 1 provides the following information for each included article: author, title, year of publication, location of the study (or study authors), sample size by diagnostic group, criteria used to define diagnostic groups, type of scan used to measure CBF, ages of participants in each diagnostic group, whether the paper was included in the synthesis, and which outcomes of interest were included. Notes are included to clarify special circumstances as necessary. Of the 81 papers, 49 measured CBF using SPECT, 18 using ASL MRI, one using both, and 13 using other methods. Publication dates range from 1987 to 2022.

Table 1 reports the component scores and overall quality rating on the risk of bias assessment for each paper. Justification for each score is given in the “Overall Quality Rating and Notes” column. Of the 81 papers, 36 were rated as “good,” 31 were rated as “fair,” and 14 were rated as “poor.” All of the papers rated “poor” either lacked cognitive test scores for the CN group, without which it is not clear that the CN group is free of cognitive decline, or had a CN group that was much younger than the MCI/AD group and thus not part of the same population.

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment scores for included articles.

| Authors | Clearly Stated Objective | Clearly Defined Sample | Controls and Cases from same Population | Same Inclusion Criteria for Controls and Cases | Clear Distinction of Cases and Controls | Reliable Methods to Measure CBF | Blind Assessment of CBF | Confounding Variables | Score and Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegret et al. | yes | no | yes | no | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | fair; little information about samples; AD group were all taking AChEIs while the other groups were not, and most CN did not have CT to check for exclusions |

| Alfini et. al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Ashford et. al. | yes | yes | not applicable | not applicable | yes | yes | not reported | no | fair; it appears that scan images were assembled into 3D surface pictures partly by visualizing brain landmarks, and it is not mentioned whether any manual visualization was done by blinded investigators |

| Bangen et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not reported | no | fair; image processing included manual editing of regions of interest, and it is not mentioned whether investigators were blinded to diagnosis |

| Benoit et al. | yes | yes | no | not reported | not reported | yes for AD; not reported for CN | not applicable | no | poor; CN are from a different population, scanned separately but “similarly”, not clear whether the inclusion criteria is the same, and cognitive scores for the CN group are not reported |

| Brayet et. al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | good |

| Brown et al. | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | good |

| Chaudhary et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not reported | yes | fair; image processing included manual editing of regions of interest, and it is not mentioned whether investigators were blinded to diagnosis |

| Claus et al. | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | good |

| Colloby et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| DeKosky et al. | yes | yes | not applicable | not applicable | yes | yes | yes | no | good |

| Deo et al. | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | fair; all AD are taking cognitive enhancing medications |

| Ding et al. | yes | yes | not reported | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; it is not reported whether the groups are from the same population; only CN are excluded for substance abuse |

| Duan et. al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Duran et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | good |

| Encinas et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | good |

| Firbank et al. 2003 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not reported | no | fair; image processing included manual editing of regions of interest, and it is not mentioned whether investigators were blinded to diagnosis |

| Firbank et al. 2011 | yes | no | not reported | not reported | yes | yes | yes | no | fair; little information about sample; unclear whether population and/or inclusion criteria are the same between groups |

| Germán et al. | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; all AD have positive PIB PET scans and show neurodegeneration on FDG PET or CT |

| Habert et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | good |

| Hanyu et al. | yes | yes | not applicable | not applicable | yes | yes | yes | no | good |

| Harris et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | good |

| Hayashi et. al. 2011 | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | fair; the only criteria listed for the control group is a normal MMSE score |

| Hayashi et al. 2021 | yes | yes | no | no | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; the controls were already incorporated into the eZIS SPECT analysis program; all AD showed MTL atrophy and were amyloid beta positive on PIB PET |

| Houston et al. | yes | no | no | no | yes | yes | not applicable | no | poor; the control groups are much younger than AD and one is all men; this is because that control group was matched to the group of boxers rather than AD. It is not clear where any of the participant groups were recruited from. |

| Hoyer, Nitsch & Oesterreich | yes | yes | no | no | yes | yes | not applicable | no | poor; the controls are much younger than the advanced late onset AD group |

| Iizuka & Kameyama | yes | yes for cases, no for controls | not reported | not reported | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; it is not clear whether the groups are from the same population; only AD are excluded for taking anti-anxiety or antidepressant medications |

| Imran et al. | yes | no | not reported | no | no | yes | not applicable | no | poor; it is not clear whether cases and controls are from the same population; only AD have scores reported on MMS and CDR |

| Ishiwata et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | fair; NINCDS/ADRDA was used to exclude MCI, but the paper did not specifically say that it was used to diagnose AD. |

| Ito et. al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | good |

| Jagust et al. | yes | no | yes | yes | not reported | yes | not reported | no | poor; while not explicitly clear, it can be deduced that groups are from the same population; inclusion criteria appears to be the same; cognitive exam scores are not reported for CN |

| Johnson et al. 1988 | yes | no | not reported | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | fair; it is not clear where the participants were recruited from or whether AD and CN came from the same population; ROIs may have been manually placed, and it is not clear whether this was done by blinded investigators |

| Johnson et al. 2007 | yes | no | yes for the MCI at baseline; unknown for AD | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; not clear whether the AD are from the same population as the MCI at baseline. Inclusion criteria is also not applied to several MCI, who are younger than the reported 65 year cutoff |

| Kaneta et. al. | yes | no | yes | yes | yes for AD, not reported for MCI | yes | not applicable | no | fair; all patients are MCI or AD, but it isn’t clear where they were recruited from or how MCI is defined here |

| Keller et. al. | yes | yes | not applicable | not applicable | yes | yes | not applicable | no | good |

| Kimura et al. | yes | yes for cases, no for controls | not reported | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; little information about the CN group; not clear if they are from the same population as AD |

| Knapp et. al. | yes | no | not reported | no | yes | yes | yes | no | fair; it is not clear whether the cases and controls are from the same population, and they have slightly different exclusion criteria |

| Komatani et al. | yes | yes for controls, no for AD | not reported | not reported | not reported | yes | not reported | no | poor; the criteria used for diagnostic classification is not explicitly stated, and it is not stated how the CN group was confirmed to be CN; image processing may have included manually placing ROIs, and it is not stated whether investigators were blinded |

| Lacalle-Aurioles et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | good |

| Lajoie et. al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Lee et al. | yes | no | not reported | not reported | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; little information given about the sample, not clear whether the groups are from the same population or if they have the same inclusion criteria |

| Liu et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Lobotesis et al. | yes | yes | yes | not reported | yes | yes | yes | no | fair; the exclusion criteria for the AD group is not reported |

| Lövblad et. al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | good |

| Mattsson et. al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Mielke et al. | yes | no | not reported | no | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; it is not clear whether AD and CN are from the same population, and only AD are tested/ excluded for ischemic infarcts or brain tumors |

| Mitsumoto et al. | yes | yes | yes | not reported | yes | yes | yes | no | fair; the exclusion criteria is not reported |

| Mubrin et al. | yes | no | not reported | not reported | not reported | yes for imaging; not reported for processing | not reported | no | poor; very little information about samples, especially CN; CN does not have cognitive scores reported |

| Nagahama et al. | yes | yes for cases, no for controls | not reported | yes | not reported | yes | not applicable | no | poor; little information about CN, not sure if they are from the same population as AD; cognitive scores not reported for CN |

| Nobili et al. | yes | yes | not applicable | not applicable | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| O’Mahony et al. | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | no | fair; only AD had screening with CT scans; it appears that ROIs were manually placed, and it is not stated whether investigators were blinded to diagnosis |

| Obara et al. | yes | no | not reported | no | yes | yes | not reported | yes | fair; little information about sample; not sure whether groups are from the same population; inclusion criteria differs slightly between groups |

| Ottoy et. al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Pappatà et al. | yes | yes | not reported | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | fair; it is not clear where participants are recruited from; ROIs are manually adjusted, but it is not stated whether investigators were blinded to diagnosis |

| Prohovnik et al. | yes | yes | yes | not reported | no | yes | no | yes | poor; inclusion criteria is not fully reported, CN do not have cognitive scores reported, and it is not stated whether the investigators were blinded during image processing |

| Quattrini et al. | yes | yes | not applicable | not applicable | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Rane et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Rubinski et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Sase et al. | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; inclusion criteria differs slightly between groups |

| Schuff et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Shimizu et al. | yes | yes for cases, no for controls | not reported | no | not reported | yes | not applicable | no | poor; not reported whether the groups are from the same population; only AD are excluded for taking medication that affects the CNS; cognitive exam scores are not reported for CN |

| Song et al. | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; only controls are excluded for history of head trauma, epilepsy, stroke, or brain surgery |

| Sundström et al. | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | poor; CN are younger than AD |

| Takahashi et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | good |

| Takano et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | good |

| Takenoshita et al. | yes | yes | not applicable | not applicable | yes | yes | not applicable | no | good |

| Tanaka et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Tateno et al. | yes | no | not reported | no | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; little information given about the sample, not clear whether the groups are from the same population; only CN have abnormalities on scans as exclusion criteria |

| Terada et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | good |

| Tokumitsu et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Tosun et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Tu et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | fair; ROIs were manually placed, and it is not stated whether investigators were blinded to diagnosis |

| van de Haar et al. | yes | yes | yes | no | not reported | yes | yes | yes | poor; only AD are excluded for history of stroke; CN are said to complete cognitive exams, but their scores are not reported |

| Wang et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | good |

| Warkentin et al. | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | poor; CN are much younger than AD |

| Xie et al. | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Yamaji et al. | yes | yes | not applicable | not applicable | yes | yes | not applicable | no | good |

| Yamashita et al. | yes | yes | not reported | yes | yes | yes | not applicable | no | fair; it is not clear where the controls were recruited from |

| Yoshida et al. 2011 | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | no | fair; inclusion criteria are not the same: all AD have APOE ε4, but this is not reported for CN |

| Yoshida et al. 2017 | yes | yes | not applicable | not applicable | yes | yes | not applicable | yes | good |

| Zurynski et al. | yes | yes | Yes | yes | no | yes | not applicable | yes | poor; it is not clear whether CN completed cognitive testing |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease, AchEI: acetyl cholinesterase inhibitor, APOE: apolipoprotein E, CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating, CBF: cerebral blood flow, CN: cognitively normal, CNS: central nervous system, CT: computed tomography, eZIS: easy Z-score imaging system, FDG: fluorodeoxyglucose, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, MMS/ MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination, MTL: medial temporal lobe, NINCDS/ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association, PET: positron emission tomography, PIB: Pittsburgh Compound-B, ROI: region of interest, SPECT: single-photon emission computerized tomography

Table 2 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 report the results of interest for each study. Table 2 reports the relative CBF in AD, Supplementary Table 2 reports relative CBF in MCI, and Supplementary Table 3 presents correlations between CBF and cognitive exam scores. In Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2, regional CBF data is given as mean (SD) for each diagnostic group, when available. For regional CBF in these tables and further analyses, values for left and right regions were averaged, with SDs pooled; this was also done across smaller brain regions within those of interest. When bilateral or subregional averaging was done, this is clarified in the “Notes” column. For voxel-wise results, cluster size (k), p value, and z or t value are reported, and the specific region where the peak voxel is located is given in the “Notes” column. The “Notes” column also mentions if the data were extracted from a graph rather than reported numerically in the paper. All results are reported, regardless of whether they were statistically significant. Papers with qualitative results are included in these tables as well, for completeness.

Table 2.

CBF in CN and AD in each paper.

| Author | Sample Size | Frontal | Parietal | Temporal | Temporoparietal | Occipital | Posterior Cingulate | Hippocampus | Thalamus | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegret et al. | CN: 42 AD: 42 |

AD < CN CN: 667 (25) AD: 504 (26) |

AD < CN CN: 1028 (25) AD: 802 (24) |

AD < CN CN: 885 (20) AD: 696 (26) |

AD < CN CN: 716 (23) AD: 535 (22) |

Values are eigenvariates from peak voxels where CBF differs between groups; SDs are adjusted for age; data extracted from bar graph. Regions are temporal: left temporal lobe and right temporal pole, temporoparietal: right angular gyrus, and right hippocampus. | ||||

| Benoit et al. | CN: 11 AD: 30 |

AD < CN z = 3.79 k = 1322 p = 0.008 |

AD < CN z = 3.25 k = 1431 p = 0.005 |

Results are from comparison of the whole AD group (with and without apathy) and CN; voxels correspond to right medial frontal and right posterior cingulate regions. | ||||||

| Brown et al. | CN: 14 AD: 24 |

AD < CN CN: 0.854 (0.040) AD: 0.796 (0.086) |

AD < CN CN: 0.890 (0.046) AD: 0.764 (0.104) |

AD < CN CN: 0.917 (0.050) AD: 0.839 (0.077) |

Values are regional CBF normalized to calcarine cortex; regions are frontal: low frontal & high frontal; temporal: temporal & posterior temporal; data extracted from bar graph; significance reported with Bonferroni correction | |||||

| Chaudhary et al. | CN:20 AD: 25 |

AD < CN CN: 48.56 (+10.14, −5.53) AD: 44.64 (+10.31, −11.34) |

AD < CN CN: 54.95 (+9.44, −6.70) AD: 50.93 (+9.71, −9.55) |

AD < CN CN: 59.28 (+18.44, −15.67) AD: 51.24 (+13.41, −10.31) |

The paper presented results in a graph in which error bars were not symmetrical about the mean. The temporal region combines lateral and medial temporal. Global GM CBF AD < CN CN: 55.36 (+10.14, −8.30) AD: 51.24 (+11.34, −9.28) AD < CN in anterior cingulate as well. CN: 51.03 (+12.91, −12.91) AD: 43.81 (+13.41, −12.37) |

|||||

| Claus et al. | CN: 60 AD: 48 |

AD < CN CN: 84.3 (5.6) AD: 80.8 (6.3) |

AD < CN CN: 83.0 (5.2) AD: 76.0 (7.1) |

AD < CN CN: 78.4 (6.8) AD: 70.5 (9.8) |

AD < CN CN: 89.2 (6.1) AD: 86.5 (6.4) |

Values are percentages of regional CBF relative to cerebellar CBF; anatomical ROI multi-slice values used. | ||||

| Colloby et al. | CN: 16 AD: 13 |

Mixed results; some frontal regions AD < CN and others AD > CN Middle frontal z = −2.1; medial frontal z = 2.5 |

AD < CN z = −2.9 |

AD < CN z = −1.9 |

AD > CN z = 2.0 |

AD < CN z = −2.6 |

AD < CN z = −2.4 |

This paper measured the degree to which each participant exhibited the spatial distribution of altered CBF that differentiated AD from CN. AD exhibited the pattern more than CN and thus scored higher on this measure. CN: 3.2 (1.5) AD: 10.0 (1.9) Regional differences reported contribute to the overall pattern and are the peak voxels in the region. Negative z scores denote decreased CBF in AD relative to CN. Specific peak regions are frontal: medial and middle frontal; inferior parietal, middle temporal, and lingual gyrus (occipital). |

||

| Deo et al. | CN: 9 AD: 9 |

AD < CN | AD < CN CN: 0.85 (0.08) AD: 0.77 (0.11) |

AD < CN CN: 0.91 (0.06) AD: 0.74 (0.11) |

AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | Values are ratio of regional CBF to cerebellar CBF. Regions without values come from the comparison of averaged CBF maps from AD and CN. | ||

| Ding et al. | CN: 21 AD: 24 |

AD > CN t = −3.95 k = 312 p < 0.01 |

AD < CN t = 3.34 k = 391 p < 0.01 |

AD < CN t = 3.33 k = 340 p < 0.01 |

AD < CN t = 4.77 k = 2569 p < 0.01 |

AD > CN t = −3.32 k = 355 p < 0.01 |

Voxels are: right paracentral, right superior parietal, right middle & inferior temporal, left superior, middle & inferior occipital & cuneus, and left thalamus | |||

| Duan et al. | CN: 58 MCI: 50 AD: 40 |

AD < CN AD < MCI MCI: 1.547 (0.788) AD: −1.500 (0.471) |

AD < CN AD < MCI MCI: −0.264 (0.245) AD: −1.698 (0.208) |

AD < CN AD < MCI MCI: 1.481 (0.440) AD: −1.510 (0.395) |

AD < CN AD < MCI MCI: −0.604 (0.264) AD: −2.226 (0.265) |

AD < CN AD < MCI MCI: −0.010 (1.058) AD: −1.293 (0.670) |

Global CBF AD < MCI and AD < CN CN: 38.41 (5.15) MCI: 39.66 (5.49) AD: 37.21 (3.98) Regional values are normalized to global CBF and transformed into z scores relative to CN. Negative z values denote decreased CBF relative to CN. Regions are averaged bilaterally and include: right and left inferior frontal and insular and bilateral superior medial frontal, right inferior parietal, left and right temporoparietal, bilateral posterior cingulate and precuneus, right and left hippocampus. |

|||

| Duran et al. | CN: 15 AD: 19 |

AD < CN z = 2.93 k = 197 p > 0.05 |

AD < CN z = 3.31 k = 882 p=0.04 |

AD < CN z = 3.16 k = 932 p=0.04 |

AD < CN z = 3.63 k = 617 p = 0.04 |

Peak voxels are reported for each region and include: left precuneus, left insula, left middle temporal gyrus, and right posterior cingulate; AD > CN in bilateral cerebellum and right pre- and post-central gyri. | ||||

| Encinas et al. | stable MCI: 21 MCI progressing to AD: 21 |

AD < MCI MCI: 89.8 (10) AD: 80.8 (7.8) |

AD < MCI MCI: 90.0 (8.6) AD: 82.0 (8.5) |

AD < MCI MCI: 85.0 (9.4) AD: 76.0 (9.0) |

AD < MCI MCI: 87.5 (9.1) AD: 79.5 (7.5) |

Values are percentage of regional CBF over cerebellar CBF; comparisons are stable MCI vs. MCI that progress to AD, at baseline; frontal: right and left prefrontal, right and left frontal; parietal: right and left parietal; temporal: right and left temporal, left posterior lateral temporal; temporoparietal: right and left frontoparietotemporal | ||||

| Firbank et al. 2003 | CN: 37 AD: 32 |

AD < CN p = 0.006 |

AD < CN | Voxels for parietal region are in left precuneus. There is no p value listed for the posterior cingulate. | ||||||

| Firbank et al. 2011 | CN: 29 AD: 17 |

AD < CN CN: 1.82 (0.27) AD: 1.58 (0.28) |

AD < CN CN: 1.70 (0.32) AD: 1.34 (0.31) |

AD < CN CN: 1.55 (0.27) AD: 1.47 (0.29) |

AD < CN CN: 2.68 (1.08) AD: 2.28 (0.71) |

Values are GM:WM ratio; one control does not have data for thalamus; statistics are Gabriel post hoc tests; frontal: prefrontal. | ||||

| Germán et al. | CN: 22 AD: 18 |

AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | All differences are present at a level of p < 0.05 with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Frontal regions are: lateral orbitofrontal, medial orbitofrontal, and superior frontal. Parietal regions are inferior parietal and superior parietal. Temporal regions are: inferior temporal, middle temporal, superior temporal, and transverse temporal. All regions are bilateral. | ||||

| Habert et al. | Stable MCI: 72 MCI convert to AD: 11 |

Converters < non-converters z = 3.86 k = 2679 p = 0.041 |

Converters < non-converters z = 4.10 k = 749 p = 0.041 |

CBF values were measured at baseline, before any participants converted to AD. Regions are temporoparietal: right supramarginal, right angular, and right inferior parietal; and right hippocampus. | ||||||

| Harris et al. | CN: 8 AD: 15 |

AD < CN CN: 101.6 (8.8) AD: 91.7 (10.7) |

AD < CN CN: 105.8 (8.2) AD: 89.4 (11.9) |

AD < CN CN: 106.0 (8.9) AD: 97.6 (11.3) |

All regions are combined from two slices: at basal ganglia level and superior to it | |||||

| Hayashi et al. 2021 | AD: 24 | AD < CN | AD < CN | Values are z-scores, where positive z-scores denote a reduction in CBF. Posterior cingulate, precuneus, and parietal lobe CBF AD < CN AD: 1.55 (0.57) |

||||||

| Houston et al. | CN1: 50 CN2: 40 AD: 21 |

CN1: 0.05 CN2: 0.33 AD: 2.70 |

CN1: 0.09 CN2: 0.22 AD: 2.13 |

CN1: 0.10 CN2: 0.51 AD: 2.07 |

CN1: 0.05 CN2: 0.83 AD: 3.05 |

Values are percentages of abnormal (outside 3 SDs) voxels in each region. Regions are averaged as follows: frontal (left and right frontal and left and right inferior frontal), parietal (left and right), temporal (left and right inferior temporal). | ||||

| Hoyer, Nitsch & Oesterreich | CN: 11 AD: 7 |

Global CBF AD < CN CN: 55.7 (3.0) AD: 24.3 (3.9) |

||||||||

| Iizuka & Kameyama. | CN: 9 AD: 36 |

AD < CN | AD <CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | Results were qualitative in the text and presented in a brain surface figure with a color scale, but it was not feasible to accurately extract values based on color. Comparisons were at baseline and were present in CN vs. responding and/or nonresponding AD before treatment began. | ||||

| Imran et al. | CN: 10 AD: 10 |

AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN in bilateral superior and inferior parietal lobules, bilateral inferior temporal gyri, and bilateral superior frontal gyri at t = 2.1 and p < 0.05. | |||||

| Ishiwata et al. | CN: 10 AD: 6 |

AD > CN 1% * voxel-wise results show a pattern of AD < CN in the frontal lobe |

AD < CN −8% |

AD < CN −3% |

AD < CN −2% |

AD < CN −5% |

AD < CN −3% |

Values are percentage differences (AD minus CN) in regional CBF normalized to global CBF. Regions are lateral frontal, lateral parietal, lateral temporal, and lateral occipital. | ||

| Ito et al. | MCI who do not convert: 113 MCI who convert to AD: 99 |

Converters < non-converters | Converters < non-converters | Converters < non-converters | Regions are bilateral; temporal is medial temporal. | |||||

| Jagust et al. | CN: 5 AD: 9 |

AD > CN CN: 1.11 (0.09) AD: 1.16 (0.08) |

AD < CN CN: 1.10 (0.05) AD: 0.93 (0.04) |

Values are regional CBF over whole tomographic slice | ||||||

| Johnson et al. 1988 | CN: 9 AD: 33 |

AD < CN CN: 0.69 (0.10) AD: 0.62 (0.10) |

AD < CN CN: 0.73 (0.10) AD: 0.57 (0.11) |

AD < CN CN: 0.75 (0.09) AD: 0.67 (0.08) |

AD < CN CN: 0.90 (0.10) AD: 0.81 (0.11) |

Values are regional CBF to cerebellar CBF ratios. The AD averages are calculated without the four most severe cases, who were too young for this review, but the SDs for the AD group were calculated with the 4, which is not expected to have a large effect on the SDs. | ||||

| Johnson et al. 2007 | CN: 19 AD: 34 |

AD < CN z = 3.59 k = 214 corr. p < 0.05 |

AD < CN z = 5.20 k = 6629 corr. p < 0.05 |

AD < CN z = 4.01 k = 2117 corr. p < 0.05 |

AD < CN z = 4.87 k = 862 corr. p < 0.05 |

AD > CN z = −4.42 k = 1184 corr. p < 0.05 |

Voxels are located in: left inferior frontal, left inferior parietal, right superior temporal, right posterior cingulate, and left thalamus & striatum; p values are corrected for multiple comparisons. | |||

| Kimura et al. | CN: 27 AD: 62 |

AD < CN CN: 35.4 (4.3) AD: 30.5 (5.2) |

AD < CN CN: 35.3 (3.6) AD: 30.8 (4.7) |

AD < CN CN: 40.4 (4.6) AD: 34.5 (5.9) |

AD < CN CN: 41.3 (5.1) AD: 35.9 (5.5) |

Regions are: left superior and inferior parietal, left and right middle and inferior temporal, right angular gyrus, and left and right posterior cingulate | ||||

| Knapp et al. | CN: 14 AD: 30 |

AD < CN CN: 84.28 (6.08) AD: 78.00 (9.65) |

AD < CN CN: 87.65 (6.30) AD: 77.20 (10.24) |

AD < CN CN: 80.4 (9.65) AD: 73.85 (9.51) |

AD < CN CN: 83.95 (8.30) AD: 79.55 (7.66) |

AD < CN CN: 89.50 (6.44) AD: 85.30 (11.66) |

Values are mean count density (%) relative to cerebellum. All regions were averaged bilaterally. Frontal region includes prefrontal and frontal. Temporal region includes inferior temporal, lateral temporal, and temporal. | |||

| Komatani et al. | CN: 7 AD: 9 |

AD > CN CN: 1.04 (0.02) AD: 1.08 (0.07) |

AD < CN CN: 0.98 (0.05) AD: 0.84 (0.11) |

Whole brain CBF is AD < CN, CN: 50.9 (6.9); AD: 39.7 (5.2); frontal and temporoparietal values are regional: whole brain CBF ratios. | ||||||

| Lacalle-Aurioles et al. | CN: 20 AD: 28 |

AD < CN CN: 0.849 (0.032) AD: 0.812 (0.051) |

AD > CN CN: 0.778 (0.063) AD: 0.828 (0.069) |

Values are regional CBF over whole cortical GM CBF; data was extracted from graphs; regions are: left and right parietal lobe, right medial temporal lobe. | ||||||

| Lajoie et al. | CN: 37 AD: 34 |

AD < CN CN: 39.5 (10.8) AD: 37.4 (9.0) |

AD < CN CN: 39.3 (13.1) AD: 32.7 (9.8) |

AD < CN CN: 41.2 (10.8) AD: 36.1 (8.3) |

AD < CN CN: 43.7 (11.4) AD: 39.9 (8.6) |

|||||

| Lee et al. | CN: 20 AD: 20 |

AD < CN z = 4.64 corr. p = 0.007 |

AD < CN z = 6.87 corr. p < 0.001 |

AD < CN z = 6.94 corr. p < 0.001 |

Used moderate AD as the AD group; voxels come from: left middle frontal, right superior parietal, and right superior temporal; cluster sizes not reported; p values corrected for multiple testing. | |||||

| Liu et al. | CN: 19 AD: 16 |

AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | Regions are left superior frontal, left inferior parietal, bilateral temporal, left angular (temporoparietal), and bilateral posterior cingulate. t = 5.32, p < 0.001 for overall voxel-wise comparison. | |||

| Lobotesis et al. | CN: 20 AD: 50 |

AD < CN CN: 0.90 (0.05) AD: 0.85 (0.07) |

AD < CN CN: 0.92 (0.06) AD: 0.87 (0.09) |

AD < CN CN: 0.89 (0.06) AD: 0.83 (0.09) |

AD < CN CN: 1.00 (0.04) AD: 0.97 (0.08) |

AD < CN CN: 0.98 (0.06) AD: 0.93 (0.11) |

Values are ratio of regional CBF: cerebellar CBF using the cerebellar lobe with the highest CBF. All regions were averaged across hemispheres and the temporal region includes both temporal and medial temporal measurements. | |||

| Mattsson et al. | CN: 51 AD: 24 |

AD < CN CN: 23.67 (5.58) AD: 21.37 (6.31) |

AD < CN CN: 32.5 (5.85) AD: 26.28 (4.88) |

AD < CN CN: 26.08 (6.41) AD: 19.96 (6.26) |

AD < CN CN: 31.22 (6.74) AD: 27.79 (9.17) |

AD < CN CN: 29.47 (6.32) AD: 25.41 (6.34) |

Frontal region is medial orbitofrontal, temporal is inferior temporal, and parietal is inferior parietal. | |||

| Mielke et al. | CN: 13 AD: 20 |

AD = CN CN: 0.94 (0.03) AD: 0.94 (0.04) |

AD < CN CN: 0.98 (0.01) AD: 0.96 (0.03) |

AD < CN CN: 1.06 (0.04) AD: 1.04 (0.07) |

AD > CN CN: 1.21 (0.05) AD: 1.27 (0.09) |

Values are ratio of regional CBF: global CBF. The paper also reports values with cerebellum as the reference region. Regions are frontal association cortex, temporoparietal association cortex, and occipital association cortex. | ||||

| Mitsumoto et al. | CN: 7 AD: 13 |

AD < CN CN: 0.93 (0.07) AD: 0.85 (0.06) |

AD < CN CN: 1.01 (0.07) AD: 0.88 (0.05) |

Values are ratio of regional CBF to cerebellar CBF. Parietal region is the combination of superior and inferior parietal lobules. | ||||||

| Mubrin et al. | CN: not clear AD: 31 |

AD < CN | AD < CN | Results are qualitative only; both regions are bilateral. | ||||||

| Obara et al. | CN: 18 AD: 17 |

AD < CN CN: 42.3 (9.4) AD: 37.5 (4.4) |

AD < CN CN: 43.1 (6.9) AD: 37.7 (4.9) |

AD < CN CN: 43.1 (7.6) AD: 38.2 (6.1) |

AD < CN CN: 39.5 (8.8) AD: 35.9 (4.7) |

AD < CN CN: 51.8 (10.7) AD: 47.0 (9.4) |

||||

| O’Mahony et al. | CN: 12 AD: 18 |

AD < CN CN: 0.788 (0.053) AD: 0.756 (0.068) |

AD < CN CN: 0.863 (0.048) AD: 0.758 (0.051) |

AD < CN CN: 0.785 (0.043) AD: 0.719 (0.054) |

AD < CN CN: 0.929 (0.055) AD: 0.889 (0.093) |

Values are ratio of regional CBF to cerebellar CBF. | ||||

| Ottoy et al. | CN: 10 AD: 10 |

AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN CN: 1.26 (0.1) AD: 0.98 (0.2) |

AD > CN CN: 0.86 (0.1) AD: 0.87 (0.1) |

Values are ratio of regional CBF to cerebellar CBF. This paper validates several imaging methods; values reported here are from the established 15O-H2O PET method. Frontal and parietotemporal CBF reductions were only described from a voxel-wise image (k =. 50, p < 0.05, corrected for age and education). | ||||

| Prohovnik et al. | CN: 12 AD: 18 |

Total gray matter CBF AD < CN CN: 50.31 (6.17) AD: 42.04 (5.33). |

||||||||

| Rubinski et al. | CN: 84 AD: 21 |

Global gray matter CBF AD < CN CN: 42.39 (9.73) AD: 33.70 (12.31) Partial volume effect correction was used. |

||||||||

| Sase et al. | CN: 15 AD: 27 |

This paper measures CBF in 5 mm layers from the surface of the brain. AD < CN in cingulate cortex and in every layer measured; measurements of layers were taken from lateral, superior, anterior, and posterior views. The greatest differences were found in the left lateral view of the third and fourth layers. | ||||||||

| Schuff et al. | CN: 18 AD: 14 |

AD < CN CN: 56.4 (7.9) AD: 41.2 (10.9) |

AD < CN CN: 58.7 (9.8) AD: 43.6 (11.7) |

AD < CN CN: 52.7 (19.1) AD: 45.5 (15.2) |

||||||

| Shimizu et al. | CN: 28 AD: 75 |

AD < CN AD: 1.08 (0.35) |

AD < CN AD: 1.39 (0.55) |

AD < CN AD: 1.40 (0.65) |

AD < CN AD: 0.90 (0.43) |

Values are z scores normalized to CN values | ||||

| Song et al. | CN: 33 AD: 32 |

AD < CN z = 6.96 k = 49, 544 |

AD < CN z = 5.63 k = 49, 544 |

AD < CN z = 4.42 k = 49, 544 |

AD < CN z = 5.46 k = 49, 544 |

Regions are bilateral; frontal: inferior and medial frontal; inferior parietal, inferior temporal, and cingulate gyri. Z and expected k are reported for the peak cluster in each region. | ||||

| Sundström et al. | CN: 18 AD: 18 |

AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | Voxel-wise comparison are presented graphically but not numerically; frontal region is mainly middle frontal | |||||

| Takahashi et al. | AD: 9 | Three nuclear medicine experts blinded to diagnosis visually assessed SPECT images based on a typical AD pattern of hypoperfusion. They rated the likelihood of this pattern as follows: very likely in 2 AD, likely in 4 AD, unlikely in 3 AD. None were given the rating of very unlikely. | ||||||||

| Takano et al. | CN: 12 AD: 19 |

AD < CN CN: 1.68 (0.53) AD: 1.83 (0.56) |

AD < CN CN: 1.89 (0.83) AD: 2.16 (0.88) |

AD < CN CN: 1.78 (0.62) AD: 1.85 (0.71) |

AD < CN CN: 1.26 (0.54) AD: 1.28 (0.65) |

AD < CN CN: 1.80 (0.59) AD: 2.25 (0.65) |

AD < CN CN: 1.70 (0.72) AD: 2.00 (0.78) |

Values are z scores relative to the global mean of a normal brain database. Positive z scores denote hypoperfusion. Frontal region includes: superior frontal, middle frontal, inferior frontal, medial frontal, orbital gyrus, rectal gyrus, paracentral lobule, precentral gyrus, and subcallosal gyrus. Parietal region includes: superior parietal lobule, inferior parietal lobule, angular gyrus, postcentral gyrus, precuneus, and supramarginal gyrus. Temporal includes: superior temporal, middle temporal, inferior temporal, and transverse temporal. Occipital includes: superior occipital, middle occipital, inferior occipital, cuneus, fusiform, and lingual gyrus. | ||

| Tateno et al. | CN: 16 AD: 38 |

AD < CN CN: 42.2 (3.5) AD: 37.2 (3.9) |

AD < CN CN: 36.8 (5.3) AD: 33.7 (4.1) |

AD < CN CN: 45.2 (4.0) AD: 38.5 (4.9) |

AD < CN CN: 30.4 (5.2) AD: 26.3 (3.1) |

AD < CN CN: 39.3 (7.2) AD: 34.4 (5.7) |

Values were extracted from bar graphs; the temporoparietal data is from the angular gyrus | |||

| Tokumitsu et al. | AD: 128 | This paper calculates z scores normalized to a control database for the severity of CBF decrease in bilateral posterior cingulate, precunei, and parietal cortices. Positive z-scores denote reduced CBF. AD < CN AD: 1.29 (0.35). |

||||||||

| Tu et al. | CN: 30 AD: 50 |

AD < CN CN: 53.0 (9.9) AD: 48.7 (9.9) |

AD < CN CN: 53.6 (11.2) AD: 51.4 (11.1) |

Regions are averaged bilaterally.The frontal region includes superior, middle, and inferior frontal gyri. The temporal region includes superior, middle, and inferior temporal gyri. | ||||||

| van de Haar et al. | CN: 16 MCI/AD: 14 |

MCI/AD < CN CN: 38.9 (7.2) MCI/AD: 33.3 (7.6) |

MCI/AD < CN CN: 39.6 (6.7) MCI/AD: 32.4 (7.4) |

MCI/AD < CN CN: 36.8 (6.2) MCI/AD: 31.1 (7.6) |

MCI/AD < CN CN: 37.9 (8.3) MCI/AD: 30.7 (9.1) |

The AD group includes MCI | ||||

| Warkentin et al. | CN: 92 AD: 132 |

AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | AD < CN | Global CBF AD < CN CN: 45.9 (7.2) AD: 36.9 (5.5) A cluster analysis was used to group AD participants according to their hypoperfusion patterns. All 132 had decreased CBF in temporal and temporoparietal regions. In addition to this hypoperfusion, 67 AD had hypoperfusion in mostly parietal regions, and 65 AD had hypoperfusion in mostly frontal regions. |

||||

| Yoshida et al. 2011 | CN: 8 AD: 8 |

AD > CN CN: 0.80 (0.06) AD: 0.82 (0.09) |

AD < CN CN: 0.84 (0.08) AD: 0.79 (0.11) |

AD < CN CN: 0.76 (0.03) AD: 0.63 (0.11) |

AD < CN CN: 0.84 (0.11) AD: 0.60 (0.11) |

Values are regional CBF: occipital cortex CBF ratios; the temporal region is the medial temporal lobe. | ||||

| Zurynski et al. | CN: 15 AD: 15 |

Global CBF AD < CN CN: 44.7 (7.4) AD: 31.2 (6.4) |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease, CBF: cerebral blood flow, CN: cognitively normal, GM: grey matter, MCI: mild cognitive impairment, PET: positron emission tomography, ROI: region of interest, SD: standard deviation, SPECT: single-photon emission computerized tomography, WM: white matter

With respect to reported values regardless of statistical significance, most of the 57 included papers reported relatively decreased CBF in AD in all brain regions we included. Relatively increased CBF in AD was reported in some papers in the following regions: frontal, temporal and occipital lobes, hippocampus and thalamus. Most of the 16 papers that assessed MCI reported relatively decreased CBF as well, but there was a greater proportion of relatively increased CBF in MCI than in AD. Relatively decreased CBF in MCI was reported in all included regions, and relatively increased CBF in MCI was reported in the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes and the temporoparietal region. The following paragraphs describe the frequency of each finding. These findings are listed for each paper in Table 2 for AD and Supplementary Table 2 for MCI.

Decreased relative CBF in AD was reported in the frontal lobe in 31 papers, in the parietal lobe in 37 papers, in the temporal lobe in 34 papers, in temporoparietal regions in 17 papers, in the occipital lobe in 14 papers, in the posterior cingulate in 22 papers, in the hippocampus in five papers, and in the thalamus in seven papers. Relative increases in CBF in AD were reported in the frontal lobe in five papers, in the temporal lobe in one paper, in the occipital lobe in one paper, in the hippocampus in one paper, and in the thalamus in three papers. One paper reported regions of both increased and decreased relative CBF in the frontal lobe, and another paper reported no relative difference of CBF in the frontal lobe. One paper reported a higher percentage of abnormal CBF voxels in AD in frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital regions, and one paper reported relatively decreased CBF in AD in a combined posterior cingulate, precuneus, and parietal region. Of the papers that did not report relative CBF by the included regions, five papers reported lower global CBF in AD compared to CN and one paper reported that 6 of 9 AD participants showed AD-typical patterns of decreased CBF. Additionally, individuals with MCI who converted to AD had decreased CBF compared to those who did not convert in the temporoparietal region in two papers and in the temporal lobe, posterior cingulate, and hippocampus in one paper each.

Relative decreases in CBF in MCI were reported in the frontal lobe in two papers, in the parietal lobe in five papers, in the temporal lobe in six papers, in the temporoparietal region in one paper, in the occipital lobe in two papers, in the posterior cingulate in seven papers, in the hippocampus in five papers, and in the thalamus in three papers. One paper reported decreased relative CBF in a combined region including posterior cingulate, precuneus, and parietal lobe. Relative increases in CBF in MCI were reported in the frontal lobe in three papers, in the temporal lobe in one paper, and in the temporoparietal region in one paper. One paper reported equal CBF between MCI and CN in parietal and occipital lobes. One paper found relative decreases in CBF in progressive MCI but relative increases in CBF in stable MCI in parietal and occipital lobes. This paper also found a relative increase in CBF in progressive MCI but unaltered CBF in stable MCI in the frontal lobe. Of the papers that did not report relative CBF by the included regions, one paper reported lower global CBF in MCI compared to CN, one paper reported decreased relative CBF in the anterior cingulate, and one paper reported that 23 of 39 individuals with MCI had an AD-like pattern of decreased CBF. Finally, one paper reported that CN who later declined to MCI had relatively decreased CBF in the posterior cingulate compared to those who did not decline.

Supplementary Table 3 reports r and p values for the correlation of regional CBF and cognitive test scores with details in the “Notes” column. Thirty-six papers were included, and a majority of them reported a positive correlation (better cognitive function associated with higher CBF), but there were also reports of negative correlations and of no correlation. Results were included in the table regardless of statistical significance. A positive association between regional CBF and cognitive function was reported in 30 papers. The cognitive tests used in these papers include the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), 15- Objects Test, 15 item Boston Naming Test, Poppelreuter test, California Verbal Learning Test, delayed recall portion of the Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS), cognitive portion of the ADAS, modified MMSE, Kanji writing test, Cognitive Capacity Screening Examination, Cambridge Cognition Examination (CAMCOG; language, praxis, and abstraction sub-scores), Mini Mental State Questionnaire, Trail Making Test Part B, episodic memory, visuospatial, and attention z scores, Hasegawa’s Dementia Scale, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, paired associate learning on the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB), Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices, Sally-Anne test, Clinical Dementia Rating scale, logical memory portion of the Wechsler Memory Scale 3rd Edition, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease neuropsychological battery, and selective reminding, constructional praxis, and visual search tests. Negative correlations between regional CBF and cognitive function were reported in two papers, using the Trail Making Test Part B and Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Finally, eleven papers reported no relationship between CBF and cognitive function. The cognitive tests used in these papers include: Trail Making Test Part B, Clinical Dementia Rating scale, MMSE, cognitive portion of the ADAS, memory and executive portions of the CAMCOG, revised CAMCOG, revised Wechsler Memory Scale, five-choice reaction time portion of the CANTAB, California Verbal Learning Test, self-ordering test, category fluency, and logical memory test.

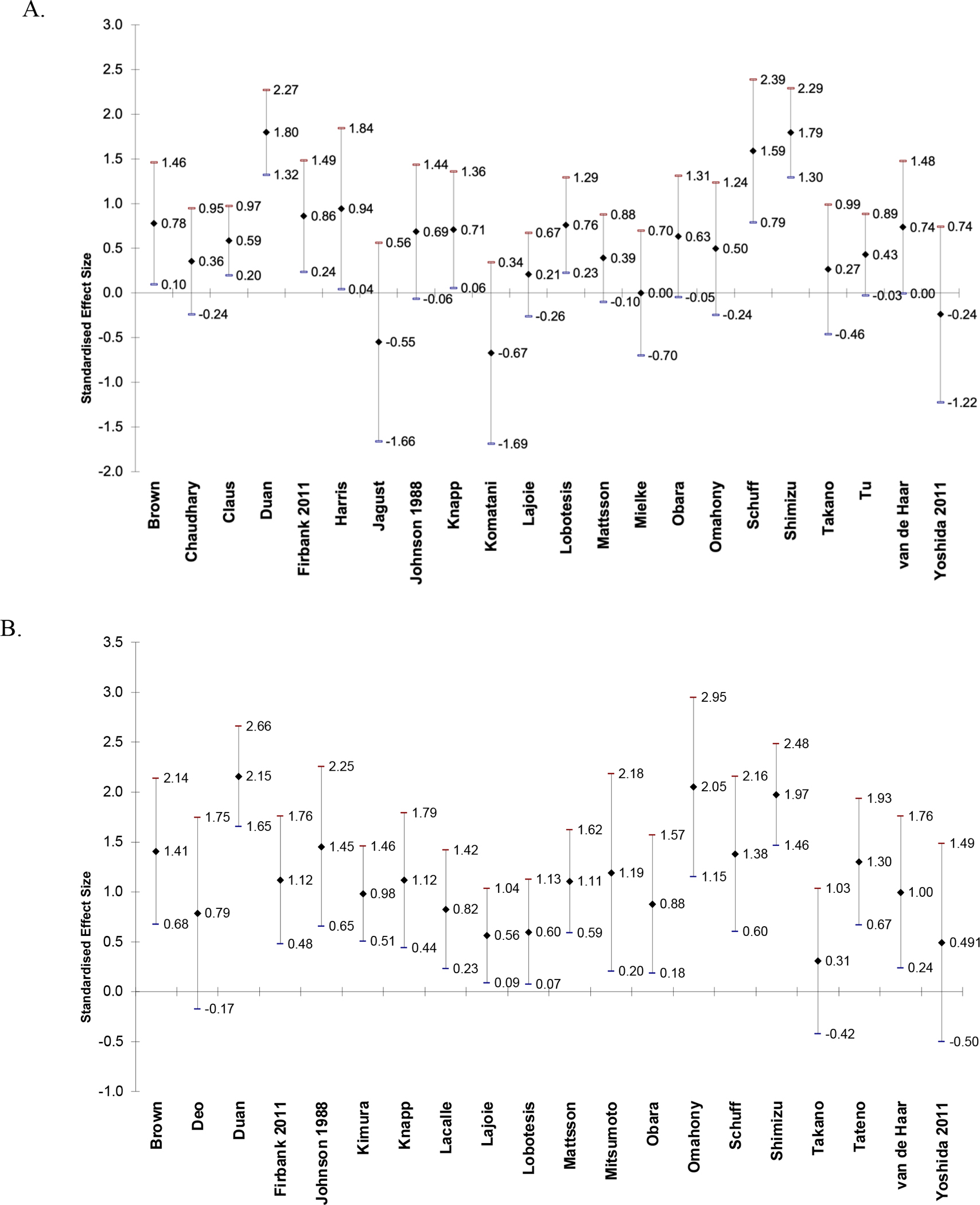

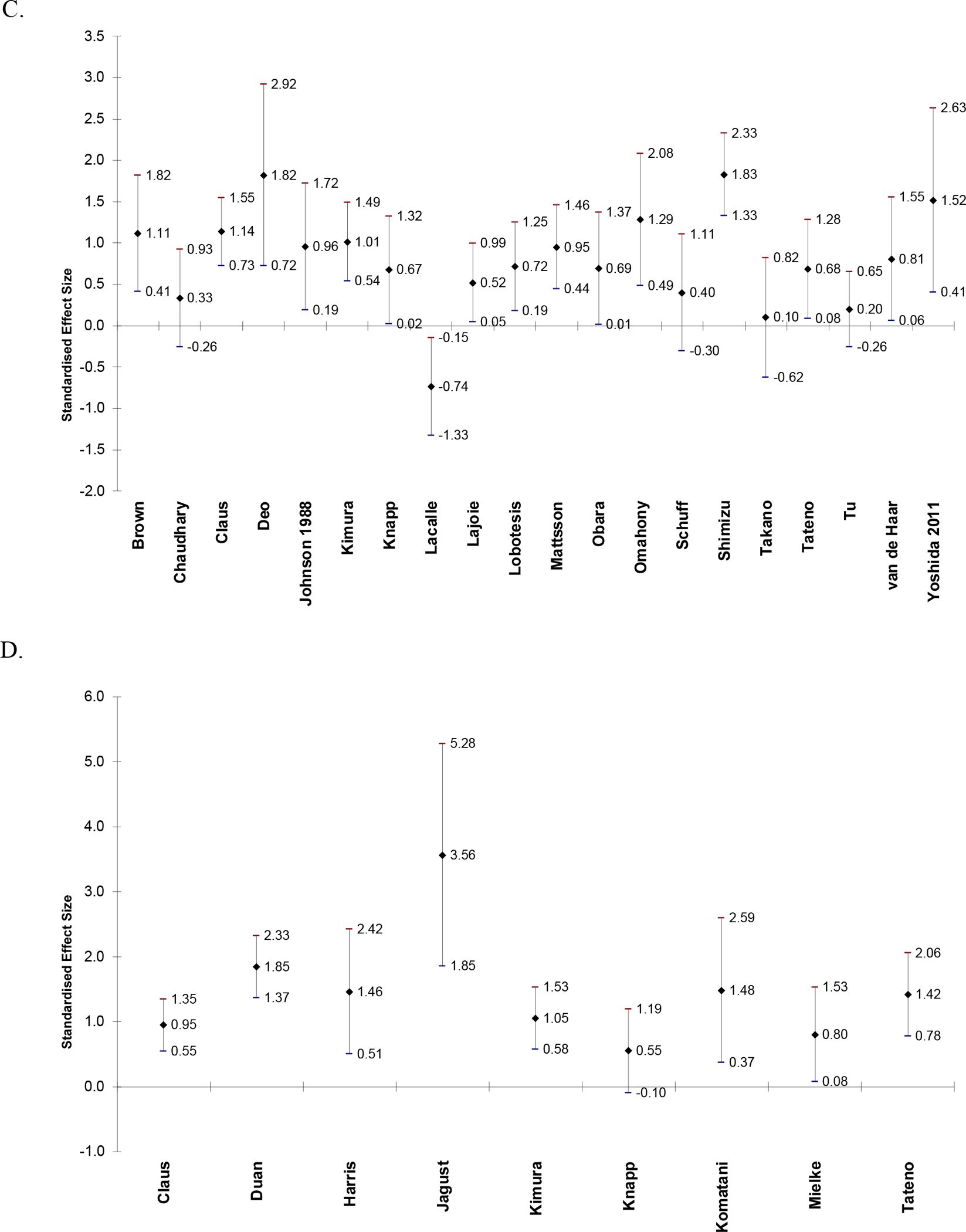

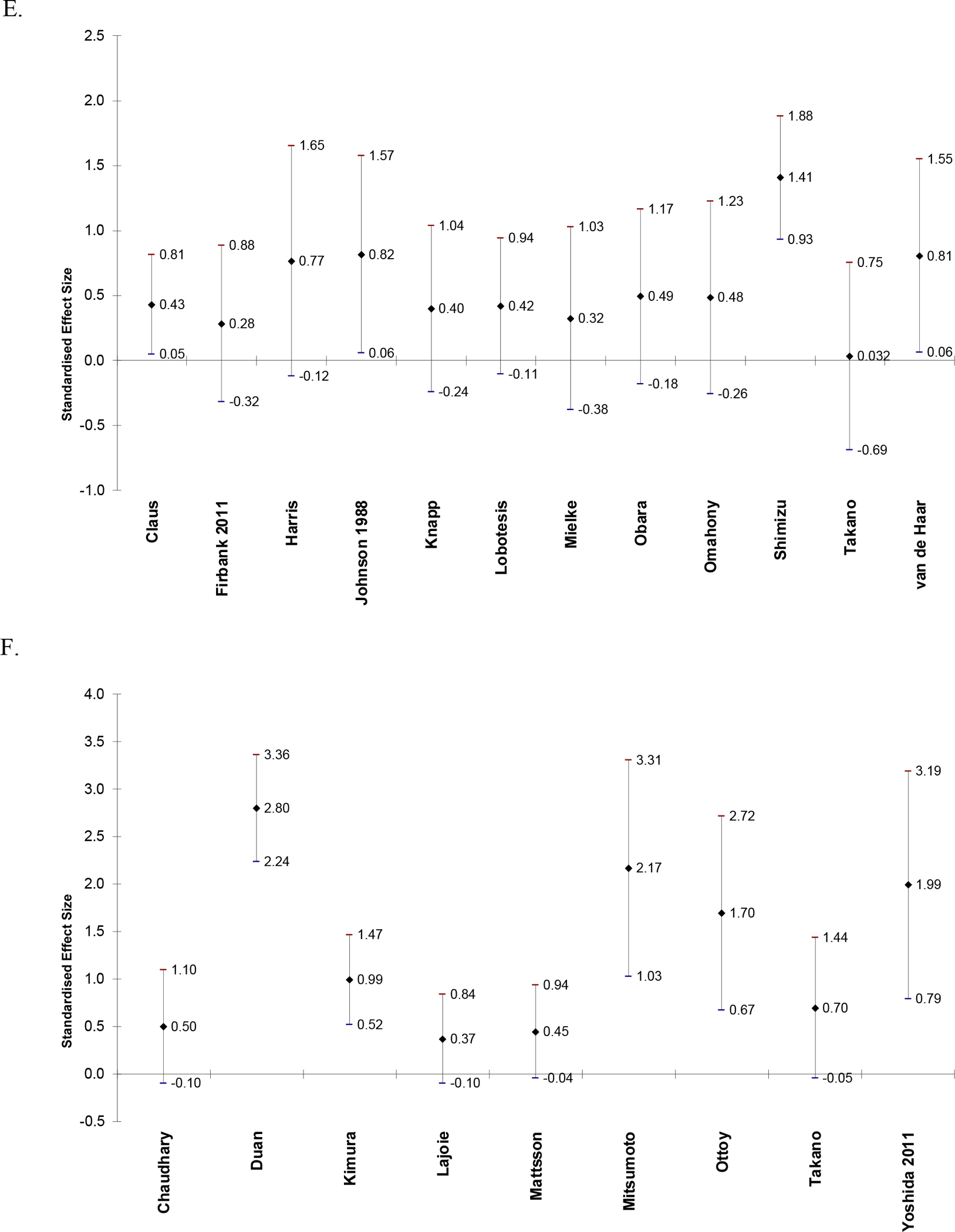

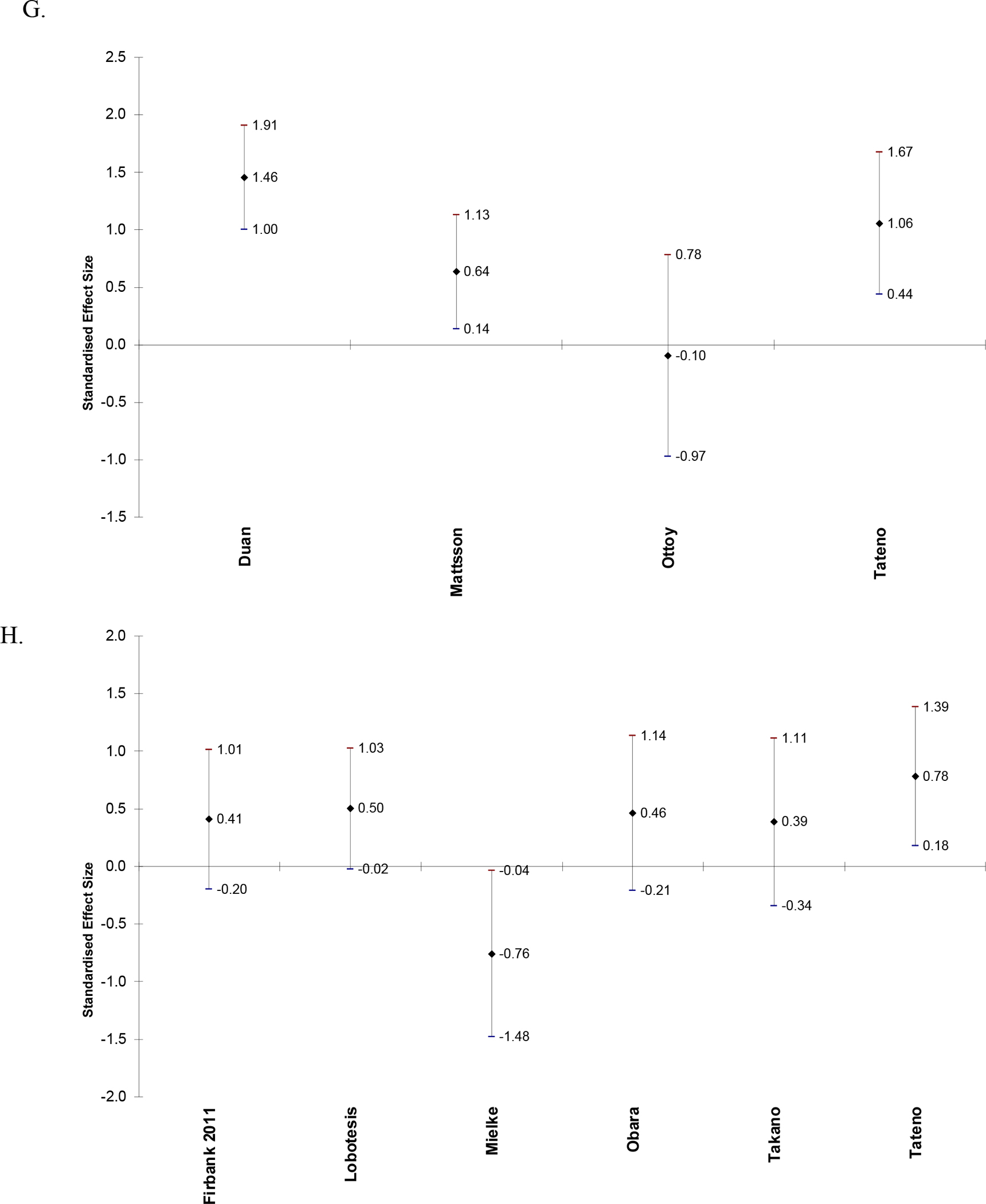

Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1 graphically present the Hedge’s g score and 95% confidence interval for the difference in CBF between AD and CN (Figure 2) and between MCI and CN (Supplementary Figure 1) for each brain region of interest. For all effect sizes, a positive value represents a decrease in CBF in patients relative to CN, as this was how the results were reported in nearly all of the papers.

Figure 2.

Effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals of difference in CBF between AD and CN in frontal lobe (A), parietal lobe (B), temporal lobe (C), temporoparietal region (D), occipital lobe (E), posterior cingulate (F), hippocampus (G), and thalamus (H). Positive effect sizes indicate that CBF is decreased in AD relative to CN.

Table 3 is a Summary of Findings table for the syntheses of results. Results are presented for CBF in CN vs. AD in papers that reported regional CBF values as mean (SD). Twenty-eight papers were included. Alegret et al. (2010) was not included because the results were reported as eigenvariates and are not comparable to the measurements in the other papers. Table 3 reports combined sample size, number of studies included, authors of included studies, mean, median, and range of Hedge’s g scores, certainty, and comments for syntheses of CBF in AD relative to controls in each brain region. The region with the greatest mean Hedge’s g (greatest relative decrease in CBF in AD) is the temporoparietal (g = 1.47), followed by the posterior cingulate (g = 1.30). All regions had positive mean and median Hedge’s g scores (decreased relative CBF in AD). At least one paper reported an increase in CBF in AD compared to CN in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, hippocampus, and thalamus.

Table 3.

Syntheses of CBF in AD compared to CN by brain region.

| Brain Region | Individuals | Studies | Hedge’s G; Mean, Median and Range | Certainty and average risk of bias score (1 to 3) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal | 593 cases; 487 controls | 22: Brown et al., Chaudhary et al., Claus et al., Duan et al., Firbank et al. 2011, Harris et al., Jagust et al., Johnson et al. 1988, Knapp et al., Komatani et al., Lajoie et al., Lobotesis et al., Mattsson et al., Mielke et al., Obara et al., O’Mahony et al., Schuff et al., Shimizu et al., Takano et al., Tu et al., van de Haar et al., Yoshida et al. 2011 | 0.57; 0.61 (−0.70, 1.80) | moderate 2.29 | Three papers reported increased CBF in AD relative to CN (Jagust, Yoshida, and Komatani) and one study reported no difference in CBF between AD and CN (Mielke). Data was extracted from graphs in three papers (Brown, Chaudhary, and Duan). Subregions were combined in six papers (Brown, Duan, Harris, Knapp, Takano, and Tu). Subgroups of AD severity were combined in Johnson, and the AD group included MCI in van de Haar. |

| Parietal | 567 cases; 423 controls | 20: Brown et al., Deo et al., Duan et al., Firbank et al. 2011, Johnson et al. 1988, Kimura et al., Knapp et al., Lacalle-Aurioles et al., Lajoie et al., Lobotesis et al., Mattsson et al., Mitsumoto et al., Obara et al., O’Mahony et al., Schuff et al., Shimizu et al., Takano et al., Tateno et al., van de Haar et al., Yoshida et al. 2011 | 1.13; 1.11 (0.31, 2.15) | moderate 2.26 | Data was extracted from graphs in five papers (Brown, Deo, Duan, Lacalle-Aurioles, and Tateno). Subregions were combined in three papers (Kimura, Mitsumoto, and Takano). Subgroups of AD severity were combined in Johnson, and the AD group included MCI in van de Haar. |

| Temporal | 620 cases; 439 controls | 20: Brown et al., Chaudhary et al., Claus et al., Deo et al., Johnson et al. 1988, Kimura et al., Knapp et al., Lacalle-Aurioles et al., Lajoie et al., Lobotesis et al., Mattsson et al., Obara et al., O’Mahony et al., Schuff et al., Shimizu et al., Takano et al., Tateno et al., Tu et al., van de Haar et al., Yoshida et al. 2011 | 0.80; 0.76 (−0.74, 1.83) | moderate 2.25 | One paper reported increased CBF in AD relative to CN (Lacalle-Aurioles). Data was extracted from graphs in five papers (Brown, Chaudhary, Deo, Lacalle-Aurioles, and Tateno). Subregions were combined in seven papers (Brown, Chaudhary, Kimura, Knapp, Lobotesis, Takano, and Tu). Subgroups of AD severity were combined in Johnson, and the AD group included MCI in van de Haar. |

| Temporoparietal | 271 cases; 208 controls | 9: Claus et al., Duan et al., Harris et al., Jagust et al., Kimura et al., Knapp et al., Komatani et al., Mielke et al., Tateno et al. | 1.47; 1.42 (0.55, 3.63) | moderate 2.42 | Data was extracted from graphs in two papers (Duan and Tateno). Subregions were combined in one paper (Harris). |

| Occipital | 356 cases; 239 controls | 12: Claus et al., Firbank et al. 2011, Harris et al., Johnson et al. 1988, Knapp et al., Lobotesis et al, Mielke et al., Obara et al., O’Mahony et al., Shimizu et al., Takano et al., van de Haar et al. | 0.56; 0.46 (0.03, 1.41) | moderate 2.05 | Subregions were combined in two papers (Harris and Takano). Subgroups of AD severity were combined in Johnson, and the AD group included MCI in van de Haar. |

| Posterior Cingulate | 235 cases; 230 controls | 9:Chaudhary et al., Duan et al., Kimura et al., Lajoie et al., Mattsson et al., Mitsumoto et al., Ottoy et al., Takano et al., Yoshida et al. 2011 | 1.30; 0.99 (0.37, 2.80) | moderate 2.63 | Data was extracted from graphs in two papers (Chaudhary and Duan). Subregions were combined in one paper (Duan). |

| Hippocampus | 112 cases; 135 controls | 4: Duan et al., Mattsson et al., Ottoy et al., Tateno et al. | 0.76; 0.85 (−0.10, 1.46) | moderate 2.78 | One paper reported increased CBF in AD relative to CN (Ottoy). Data was extracted from graphs in two papers (Duan and Tateno). |

| Thalamus | 161 cases; 108 controls | 6: Firbank et al. 2011, Lobotesis et al., Mielke et al., Obara et al., Takano et al., Tateno et al. | 0.30; 0.44 (−0.76, 0.78) | moderate 2.12 | One paper reported increased CBF in AD relative to CN (Mielke). Data was extracted from a graph in one paper (Tateno). |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease, CBF: cerebral blood flow, CN: cognitively normal, MCI: mild cognitive impairment

Reporting bias was assessed by rating the completeness of each paper in the syntheses. All papers that reported mean and SD CBF values for AD and CN were included except for Alegret et al. (2010) due to this paper’s use of voxel-wise eigenvariates. Of the included papers, Firbank et al. (2011) was missing CBF data from the thalamus for one CN participant, and Schuff et al. (2009) did not analyze or report occipital CBF data because too few voxels were present after selecting only “pure” gray or white matter voxels. Otherwise, results were fully reported in all papers. Papers were also included in regional syntheses if they reported CBF values for relevant subregions, some of which we combined for an average value within the synthesis region. This review only includes published articles from PubMed that were in English and fully accessible. These restrictions contribute to a moderate level of reporting bias, but reporting bias is likely not increased from other sources or for other reasons.

Certainty of syntheses was rated based on cumulative risk of bias scores of the constituent papers. Papers rated “good” were given three points, papers rated “fair” were given two points, and papers rated “poor” were given one point. A weighted average of this point system based on sample size was calculated for each synthesis region, and if the weighted average risk of bias score (based on sample size) was less than two, the overall certainty was lowered. All regions had average risk of bias scores of at least two; these scores are included in the “certainty” column of Table 3. Certainty was also lowered due to inconsistency (scores were higher if all results were in the same direction), and indirectness and/or imprecision (including papers where we combined subregions’ values, subgroups, or where we extracted data from graphs). Large effect sizes, evidence of dose-response relationships (MCI values intermediate between CN and AD values), and confounding factors that would have likely resulted in an effect of the opposite direction were considered as reasons to raise or maintain the certainty score. Certainty scores could be “very low,” “low,” “moderate,” or “high.” All regions were given a certainty score of “moderate.” Justifications for each certainty score are included in detail in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we compiled findings of altered CBF and the relationship between CBF and cognitive test scores in MCI/AD from previously published literature. Fifty-seven papers were included for relative CBF in AD, 17 papers were included for relative CBF in MCI, and 36 papers were included for the relationship between CBF and cognition. There were consistent reports of decreased CBF in AD compared to CN in parietal, temporoparietal, and posterior cingulate regions. Frontal, temporal, occipital, hippocampal and thalamic regions each had either relatively increased or unaltered CBF in AD reported in at least one paper. The greatest relative decrease in CBF in AD was in the temporoparietal and posterior cingulate regions according to the 28 papers included in the synthesis. There were consistent reports of decreased CBF in MCI compared to CN in posterior cingulate, hippocampal and thalamic regions, with mixed results in all other included regions. Across regions, 94% of the results reported relatively decreased CBF in AD, whereas 86% reported relatively decreased CBF in MCI.

The higher percentage of brain regions with relatively increased CBF in MCI may be because there were fewer papers that compared CBF between MCI and CN. However, it has been suggested that increased CBF in MCI could be a compensatory response to early AD pathology, in which increased blood flow is necessary in order to function at a normal level. Tang et al. (2022) completed a meta-analysis of CBF findings in MCI with ASL MRI; they found that MCI had decreased CBF in precuneus, inferior parietal, superior occipital, middle temporal and middle occipital regions and increased CBF in the lentiform nucleus. Here, we found the most consistent relatively decreased CBF in MCI in the posterior cingulate and the most frequently reported relatively increased CBF in MCI in the frontal lobe. It appears that decreased regional CBF is common in MCI, and future meta-analyses will allow us to more thoroughly describe the spatial and temporal patterns of CBF changes in MCI. In Zhang et al. (2021), the authors concluded that decreased CBF begins in the posterior cingulate, temporoparietal, and thalamic regions during MCI and that decreased CBF becomes more widespread in AD. We also found evidence of decreased CBF in MCI and reported MCI values that were intermediate between CN and AD values (Alegret et al., 2010). Additionally, we found that the greatest relative decreases in CBF in AD were located in the temporoparietal region and the posterior cingulate; CBF in the posterior cingulate was consistently relatively decreased in MCI as well. Both of these regions have been reported to have decreased CBF and decreased glucose metabolism in previous studies and reviews, and these alterations are considered characteristic of AD (Matsuda, 2001). The reasons for this pattern may be due to the spatial spread of tau pathology during AD, to vulnerability of these areas to vascular and/or neuronal damage, or to damage of functionally connected brain regions. However, several papers reported relatively increased CBF in MCI and even in AD, suggesting that alterations in CBF leading up to and during the course of AD are not linear in nature. Like Zhang et al. (2021), we found quite consistent findings of positive correlations between regional CBF and cognitive functioning, which supports the idea that decreased CBF is associated with cognitive impairment in AD. It will be necessary for future studies to elucidate whether transient increases in CBF during MCI/AD are characteristic of the disease course or if this only occurs in a particular subset of individuals with MCI/AD.