Abstract

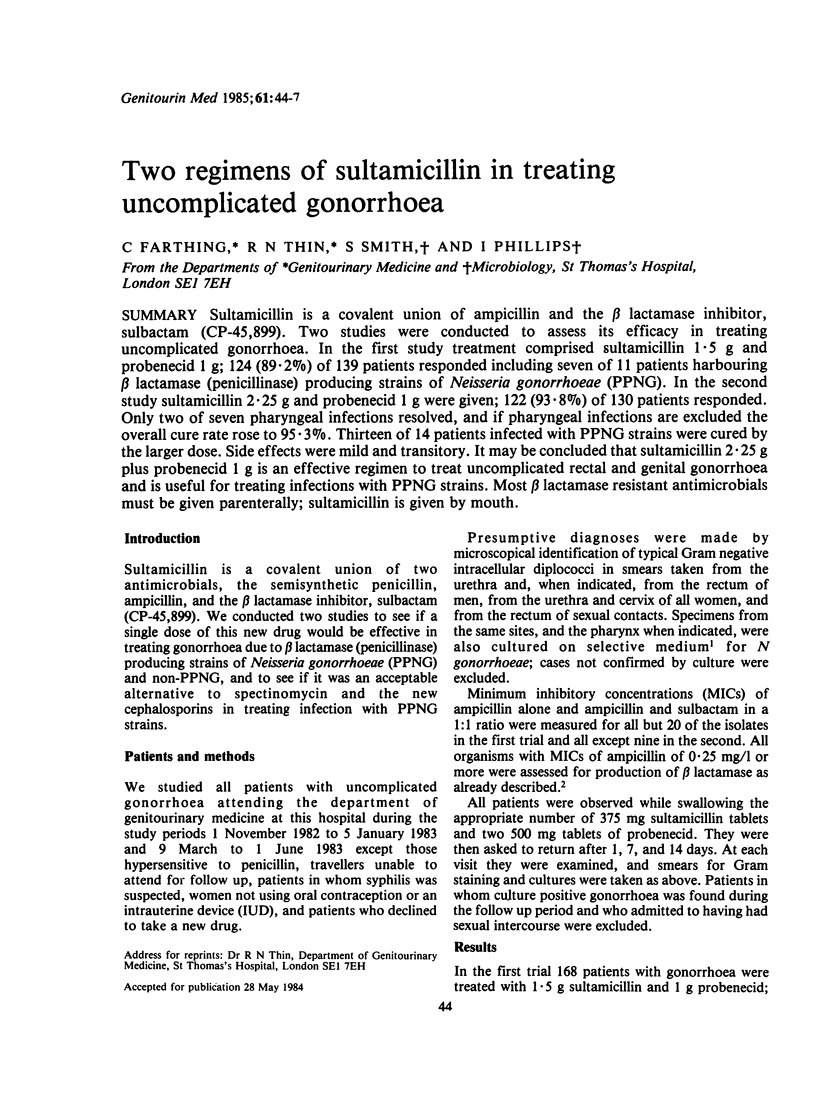

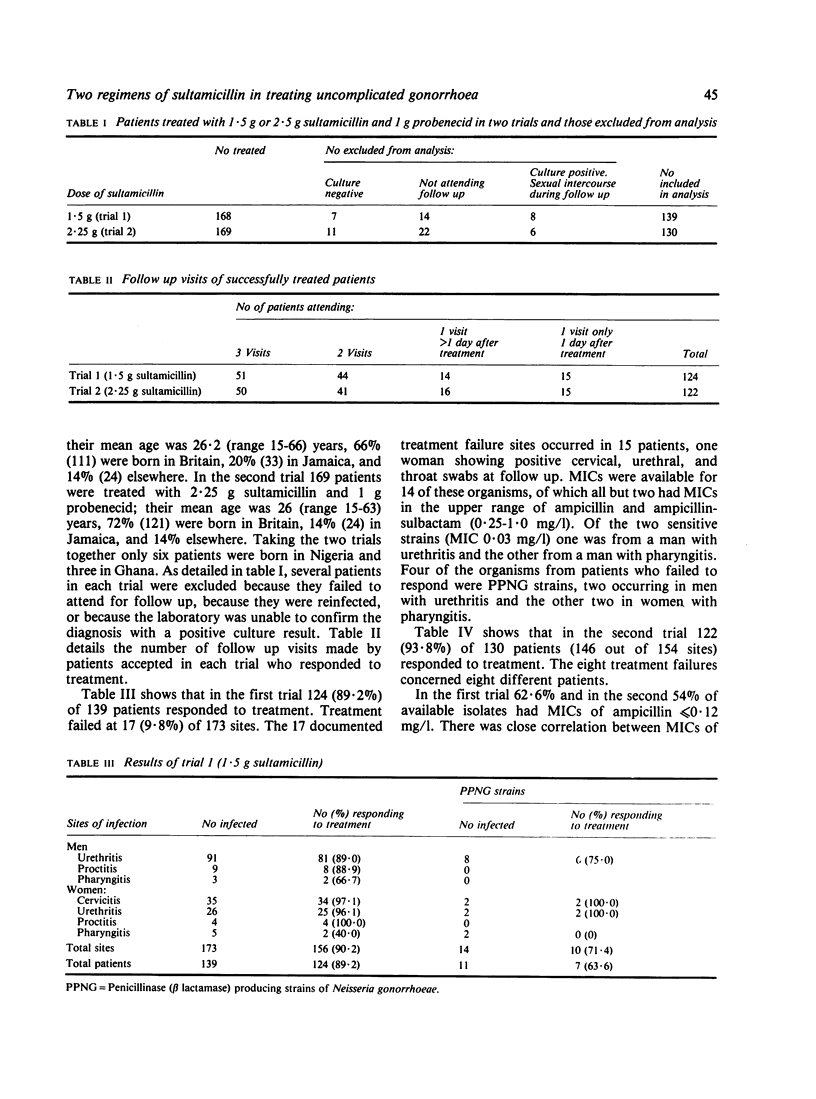

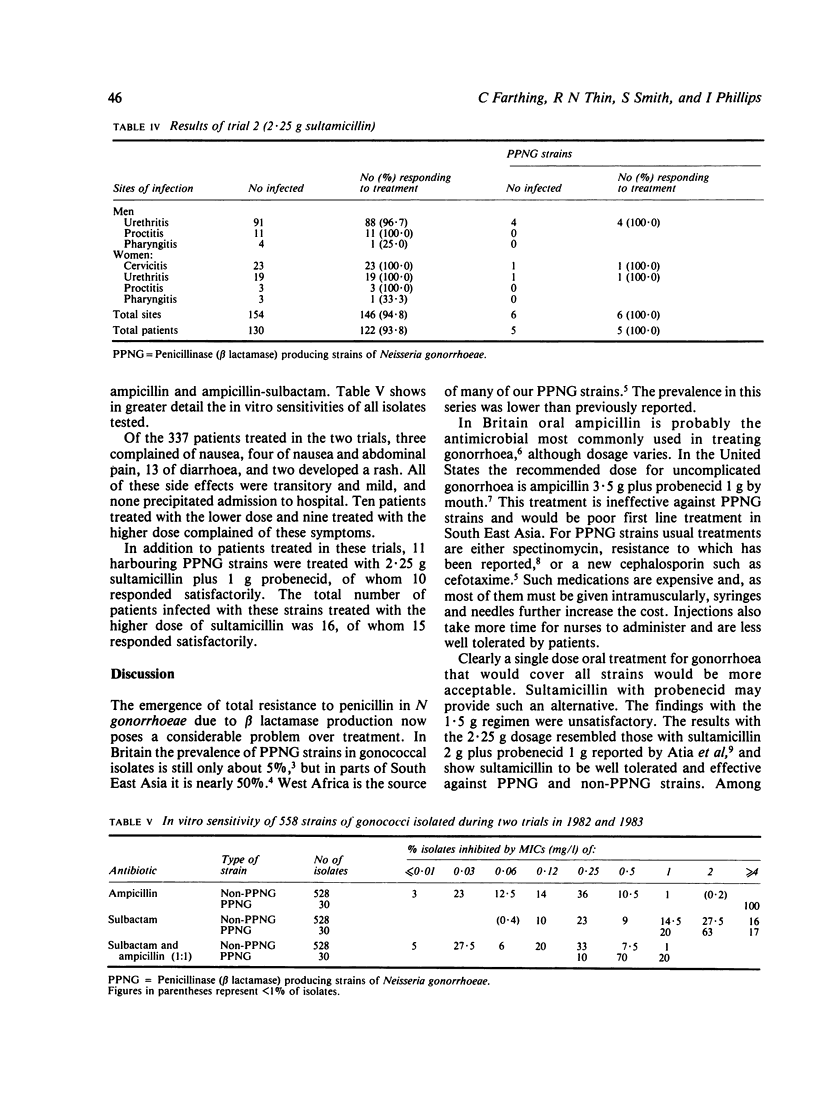

Sultamicillin is a covalent union of ampicillin and the beta lactamase inhibitor, sulbactam (CP-45,899). Two studies were conducted to assess its efficacy in treating uncomplicated gonorrhoea. In the first study treatment comprised sultamicillin 1.5 g and probenecid 1 g; 124 (89.2%) of 139 patients responded including seven of 11 patients harbouring beta lactamase (penicillinase) producing strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (PPNG). In the second study sultamicillin 2.25 g and probenecid 1 g were given; 122 (93.8%) of 130 patients responded. Only two of seven pharyngeal infections resolved, and if pharyngeal infections are excluded the overall cure rate rose to 95.3%. Thirteen of 14 patients infected with PPNG strains were cured by the larger dose. Side effects were mild and transitory. It may be concluded that sultamicillin 2.25 g plus probenecid 1 g is an effective regimen to treat uncomplicated rectal and genital gonorrhoea and is useful for treating infections with PPNG strains. Most beta lactamase resistant antimicrobials must be given parenterally; sultamicillin is given by mouth.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adler M. W. Diagnostic treatment and reporting criteria for gonorrhoea in sexually transmitted disease clinics in England and Wales. 2: treatment and reporting criteria. Br J Vener Dis. 1978 Feb;54(1):15–23. doi: 10.1136/sti.54.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atia W. A., Emmerson A. M., Holmes D. Sultamicillin in the treatment of gonorrhoea caused by penicillin sensitive and penicillinase producing strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Br J Vener Dis. 1983 Oct;59(5):293–297. doi: 10.1136/sti.59.5.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easmon C. S., Ison C. A., Bellinger C. M., Harris J. W. Emergence of resistance after spectinomycin treatment for gonorrhoea due to beta-lactamase producing strain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982 May 29;284(6329):1604–1605. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6329.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panikabutra K., Ariyarit C., Chitwarakorn A., Saensanoh C. Cefaclor and cefamandole as alternatives to spectinomycin in the treatment of men with uncomplicated gonorrhoea. Br J Vener Dis. 1983 Oct;59(5):298–301. doi: 10.1136/sti.59.5.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips I. Beta-lactamase-producing, penicillin-resistant gonococcus. Lancet. 1976 Sep 25;2(7987):656–657. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)92466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips I., Humphrey D., Middleton A., Nicol C. S. Diagnosis of gonorrhoea by culture on a selective medium containing vancomycin, colistin, nystatin and trimethoprim (VCNT). A comparison with Gram-staining and immunofluorescence. Br J Vener Dis. 1972 Aug;48(4):287–292. doi: 10.1136/sti.48.4.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thin R. N., Barlow D., Eykyn S., Phillips I. Imported penicillinase producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae becomes endemic in London. Br J Vener Dis. 1983 Dec;59(6):364–368. doi: 10.1136/sti.59.6.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]