Abstract

Purpose

In intensive care units (ICUs), decisions about the continuation or discontinuation of life-sustaining treatment (LST) are made on a daily basis. Professional guidelines recommend an open exchange of standpoints and underlying arguments between doctors and families to arrive at the most appropriate decision. Yet, it is still largely unknown how doctors and families argue in real-life conversations. This study aimed to (1) identify which arguments doctors and families use in support of standpoints to continue or discontinue LST, (2) investigate how doctors and families structure their arguments, and (3) explore how their argumentative practices unfold during conversations.

Method

A qualitative inductive thematic analysis of 101 audio-recorded conversations between doctors and families.

Results

Seventy-one doctors and the families of 36 patients from the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU (respectively, N-ICU, P-ICU, and A-ICU) of a large university-based hospital participated. In almost all conversations, doctors were the first to argue and families followed, thereby either countering the doctor’s line of argumentation or substantiating it. Arguments put forward by doctors and families fell under one of ten main types. The types of arguments presented by families largely overlapped with those presented by doctors. A real exchange of arguments occurred in a minority of conversations and was generally quite brief in the sense that not all possible arguments were presented and then discussed together.

Conclusion

This study offers a detailed insight in the argumentation practices of doctors and families, which can help doctors to have a sharper eye for the arguments put forward by doctors and families and to offer room for true deliberation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-023-07027-6.

Keywords: Intensive care, Communication, Critical care, Decision-making, Argumentation, Qualitative research

Take-home message

| Arguments put forward by doctors and families fell under one of ten main types and the types of arguments presented by families largely overlapped with those presented by doctors. A real exchange of arguments occurred in a minority of conversations and was generally quite brief in the sense that not all possible arguments were presented and then discussed together. |

Introduction

In neonatal (N-ICU), pediatric (P-ICU), and adult (A-ICU) intensive care units (ICUs), decisions about continuation or discontinuation of life-sustaining treatment (LST) are made nearly every day [1, 2]. These decisions require good communication between doctors and families and involve careful consideration of the pros and cons of the (still) possible treatments [3–5]. As recent studies have underlined, argumentation in the sense of solid reasoning is one of the intrinsic parts of the decision-making process [6–13]. Professional guidelines not only recommend an open exchange of standpoints and underlying arguments within the medical team, but also between doctors and families to reach the most appropriate decision for individual patients [14–25]. Decisions about LST have major consequences for patients and their families. These decisions are particularly difficult to make when they take place in the gray zone, i.e., in situations in which there is incomplete knowledge about the relative harms and benefits of the remaining treatment options [27]. Decisions in the gray zone require an even more solid exchange of arguments by all parties involved. It is thus far not investigated how doctors and families argue in real-life conversations in the ICU. Studying these actual argumentation practices will provide insight into how decisions are reached, and into missed opportunities and best practices.

In this qualitative observational study, we thoroughly explored doctors’ and families’ argumentation in conversations regarding the decision to continue or discontinue LST in the N-ICU, P-ICU, and A-ICU [28]. We especially focused on decisions in the gray zone. We aimed to (1) identify which arguments doctors and families of critically ill patients use in support of standpoints to continue or discontinue LST (argumentation content), (2) investigate how doctors and families structure their arguments (argumentation structure), and (3) explore how doctors’ and families’ argumentative practices unfold during conversations (argumentation dynamics).

Methods

Design and setting

This study is part of the FamICom-project in which different aspects of doctor–family communication in the ICU are studied, such as family involvement, conflict management, and uncertainty [3–5, 28]. This qualitative explorative study focused on the real-life argumentative practices of both doctors and families regarding the decision to partly or fully continue or discontinue (i.e., withhold or withdraw) LST (henceforth: to continue or discontinue LST), using inductive thematic analysis. This approach was chosen, because argumentative practices within the ICU context have not yet been studied and guiding theories are therefore lacking [29, 30]. For the sake of clarity, we quantified the incidence of the main types of arguments. Data were derived from audio recordings of team–family conversations in the N-ICU, P-ICU, and A-ICU of the Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC). ‘Families’ refers to the relatives or close friends who were present during these conversations.

Population and sampling

Seventy-one doctors and the families of 36 patients participated in our study. We strived for maximum variation regarding patients’ age, gender, diagnosis, disease progression, and course of treatment, families’ ethnic background, and doctors’ gender, medical specialty, and role.

Recruitment

Prior to data collection, all doctors and nurses from the participating units received oral and written information and were asked for their consent to participate.

Data collection

The inclusion period lasted from April 2018 to December 2019. Families of patients were eligible to participate from the moment when doubts were expressed by the medical team and/or the family whether continuing LST was in the patient’s best interests. Only conversations in Dutch or English were included. Conversations in other languages or with an interpreter were excluded.

The attending doctor or nurse introduced the study to eligible families. Families who were interested in participating were further informed and then asked for their oral and written consent by a member of the research team or the attending doctor.

From the moment of inclusion, all conversations between the medical team and families were audio-recorded until a final decision was reached to either continue or discontinue LST.

Data analysis

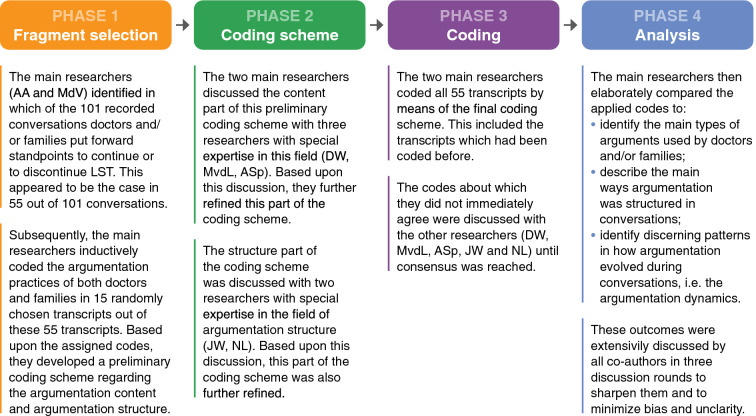

The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and anonymized. Transcripts (n = 101) were then uploaded to MaxQDA 2020 [31]. Coding and analysis consisted of four phases, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In developing our coding scheme, we were inspired by the pragma-dialectical argumentation theory [32]. In line with this theory, we differentiated between standpoints, main arguments, and sub-arguments [32]. Standpoints are defined as the positions taken toward a specific proposition. Our study focused on two standpoints: the standpoint that LST should be continued and the standpoint that LST should be discontinued. Main arguments are defined as arguments directly substantiating a standpoint, whereas sub-arguments indirectly underpin a standpoint. According to the pragma-dialectical argumentation theory, in an ideal situation, all relevant standpoints should be presented in a discussion and substantiated with relevant arguments and sub-arguments [32].

Fig. 1.

Four phases of coding and analysis

Ethics

The Amsterdam UMC institutional review board waived approval of this study (W17_475 # 17.548). All participants could withdraw their consent at any time.

Results

Seventy-one doctors and the families of 36 patients participated in our study. Table 1 lists patients’, relatives’, and doctors’ characteristics. All doctors and all but one nurse from the N-ICU gave their consent and participated. All but one of the approached families agreed to participate, the latter because they found participation too burdensome at that moment.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of included patients, relatives, and doctors

| Characteristics | Patients | Relatives | Doctors |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 36), n (%) | (N = 104), n (%) | (N = 71), n (%) | |

| Setting | |||

| Neonatal intensive care unit | 12 (33) | 33 (32) | 22 (31) |

| Pediatric intensive care unit | 12 (33) | 30 (29) | 35 (49) |

| Adult intensive care unit | 12 (33) | 41 (39) | 14 (20) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Premature | 11 (30) | – | – |

| 0–1 | 6 (16) | – | – |

| 1–4 | 1 (3) | – | – |

| 4–12 | 2 (6) | – | – |

| 12–16 | 2 (6) | – | – |

| 16–21 | 2 (6) | – | – |

| 21–35 | – | – | – |

| 35–50 | 3 (8) | – | – |

| 50–65 | 5 (14) | – | – |

| 65 + | 4 (11) | – | – |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 17 (47) | 41 (39) | 28 (40) |

| Female | 19 (53) | 63 (61) | 43 (60) |

| Main diagnosis | |||

| Prematurity | 5 (14) | – | – |

| Prematurity + congenital disorder + acute illness | 1 (3) | – | – |

| Perinatal asphyxia | 4 (11) | – | – |

| Congenital disorder | 13 (36) | – | – |

| Acute illness | 11 (30) | – | – |

| Cancer + acute illness | 2 (6) | – | – |

| Neurological damage | |||

| Yes | 24 (67) | – | – |

| No | 12 (33) | – | – |

| Total duration of care in the intensive care unit | |||

| 0–24 h | 5 (14) | – | – |

| 1–7 days | 10 (28) | – | – |

| 1–4 weeks | 16 (44) | – | – |

| 1–3 months | 5 (14) | – | – |

| Relation to the patient | |||

| Parent | – | 46 (44) | – |

| Grandparent | – | 8 (7) | – |

| Partner | – | 7 (7) | – |

| Child | – | 9 (9) | – |

| Sibling | – | 8 (7) | – |

| Brother in law/sister in law | – | 2 (2) | – |

| Aunt/uncle/cousin | – | 10 (10) | – |

| Friend | – | 4 (4) | – |

| Other | – | 5 (5) | – |

| Unknown | – | 5 (5) | – |

| Ethnic background | |||

| Dutch | – | 86 (83) | – |

| Moroccan | – | 4 (4) | – |

| Syrian | – | 1 (1) | – |

| Surinamese | – | 1 (1) | – |

| Ghanese | – | 3 (3) | – |

| Pakistani | – | 2 (2) | – |

| Turkish | – | 2 (2) | – |

| Ethiopian | – | 2 (2) | – |

| Unknown | – | 3 (3) | – |

| Medical specialty | |||

| Neonatologist | – | – | 14 (20) |

| Pediatric intensivist | – | – | 9 (13) |

| Pediatrician | – | – | 15 (21) |

| Pediatric neurologist | – | – | 7 (10) |

| Pediatric cardiologist | – | – | 3 (4) |

| Metabolic pediatrician | – | – | 2 (3) |

| Pediatric pulmonologist | – | – | 1 (1) |

| Intensivist | – | – | 9 (13) |

| Anesthesiologist | – | – | 4 (6) |

| Internist-hematologist | – | – | 1 (1) |

| Neurosurgeon | – | – | 3 (4) |

| Neurologist | – | – | 1 (1) |

| Unknown | – | – | 2 (3) |

| Role | |||

| Resident | – | – | 20 (28) |

| Fellow | – | – | 13 (18) |

| Staff | – | – | 36 (51) |

| Unknown | – | – | 2 (3) |

In most cases, doubts whether LST was still in the patient’s best interest were first uttered by the medical team. Only occasionally, families were the first to voice their doubts. In the A-ICU, it took between one and three conversations before a final decision to either continue or discontinue LST was reached, whereas in the N-ICU and P-ICU, this took between one and nine conversations.

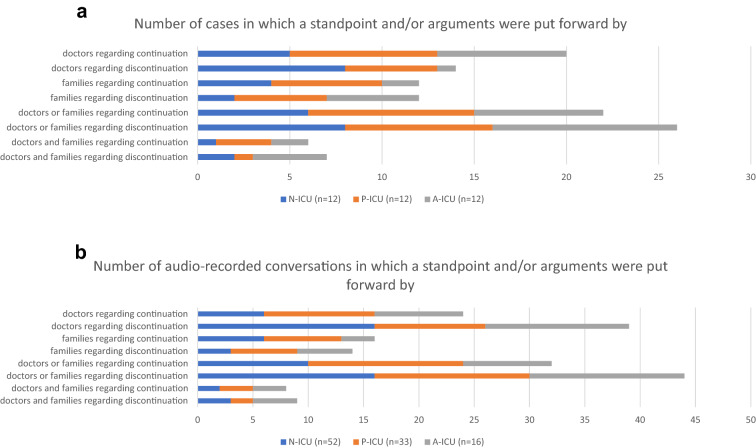

In Fig. 2a, b, we present the number of cases and audio-recorded conversations in which doctors and/or families put forward a standpoint and/or arguments.

Fig. 2.

a Number of cases in which doctors and/or families put forward a standpoint and/or arguments in support of a standpoint. b Number of audio-recorded conversations in which doctors and/or families put forward a standpoint and/or arguments in support of a standpoint

Argumentation content

Our analysis resulted in a complete overview of all arguments doctors and families of critically ill patients used in support of standpoints to continue or discontinue LST. These arguments could be classified under one of ten main types. These main types of arguments could be divided into four clusters, namely treatment-related (types 1–4), patient-related (types 5–7), family-related (types 8–9), and ‘deviating’ (type 10) types of arguments. Table 2 provides a description of the ten main types of arguments, complemented by illustrative quotes.

Table 2.

Main types of arguments and illustrative quotes

| Main types of arguments | Description | Illustrative quotes doctors | Illustrative quotes families |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment-related types of arguments | |||

|

Type 1: Generally accepted healthcare standards 18/341 coded arguments (5%) |

This type of argumentation involves for instance stressing that the latest protocols were followed or that the medical team acted according to the normal course of action. Only doctors used such arguments, both in support of discontinuing LST and—slightly more often—in support of continuing LST | After a neurological exam, a doctor argued that LST should be continued, because “the patient responded to the stimuli and in such situations, it is policy to keep on trying” | Does not apply |

| A doctor in a conversation stressed that LST should not be continued because “all tests and discussions didn’t result in new conclusions. So, according to the protocol, LST should not be continued” | |||

|

Type 2: Uncertainty 39/341 coded arguments (11%) |

Arguments concerning uncertainty were mainly used in support of continuation of LST and were put forward by doctors more often than by families | A doctor refers to uncertainty as a reason to continue LST: “So, there is that small chance and that’s why we want to seize it” | Does not apply |

|

Type 3: Medical (in)effectiveness 86/341 coded arguments (25%) |

Arguments of this type referred to the estimation whether LST was still effective or had become ineffective. Descriptions of the patient’s medical condition supporting the estimation of medical effectiveness or ineffectiveness also fell under this argument type. This type of arguments was mainly used by doctors. Occasionally, families also referred to medical ineffectiveness in their plea to discontinue LST. This was the most frequently used type of arguments | In one conversation, a doctor argued that “with everything that we do and with all the medicines we give her, we're just not going to make her better. LST should therefore be discontinued.” | A partner stated that “it won’t get any better than this. It will only get worse”, implying that LST should be discontinued |

|

Type 4: Proportionality 68/341 coded arguments (20%) |

Arguments within this type concerned the proportionality of LST, i.e., whether its pros outweighed its cons. These cons not only included the negative side effects of the provided treatment, but also the lasting effects of the illness itself. Arguments of this type were mainly used by doctors and to a lesser extent by families. They were only used to plea for discontinuation of LST This type of arguments was also commonly used |

A doctor argued to withdraw LST as “it is uncertain that it will help, while it is certain that it will cause more damage” | In a conversation, a relative compared the pros and cons of ventilations in favor of discontinuation: “Ventilation may help now, but in the longer term it will cause serious and lasting damage to her lungs” |

| Patient-related types of arguments | |||

|

Type 5: Comparison 9/341 coded arguments (3%) |

In this type of argumentation, different situations or patients were compared. Doctors mainly presented more general comparisons. Families presented more specific comparisons | A general comparison made by a doctor: “Well, it doesn’t happen often in persons who are conscious that it [the treatment provided] doesn’t work out.” | One mother compared her critically ill child with another critically child “who the doctors also only gave a ten percent chance, but who is now twelve years old and living a happy life” |

|

Type 6: Patient’s quality of life 51/341 coded arguments (15%) |

Arguments concerning the patient’s current or future quality of life were used by both doctors and families. They were mainly used to support discontinuation of LST and only occasionally to support continuation of LST. This type of arguments was quite common | In one conversation, a doctor argued that LST should be continued, because “the patient seems more at ease now” | A relative in a conversation argued that LST should not be continued as “we are continuously making concessions to her current and future quality of life.” |

|

Type 7: Patient’s former wishes and family’s substituted judgment 20/341 coded arguments (6%) |

Arguments concerning the patient’s former wishes and the family’s substituted judgment about the patient’s former wishes were mainly used by families. Doctors never referred to the patient’s documented wishes. Instead, they sometimes referred to the information which the family had just provided about what in their opinion the patient would have wished | A doctor stated: “And that, in combination with what you just told me about how your father looked at life, makes it unacceptable to continue his treatment” | Families argued that LST should not be continued, because the patient “always said that she would be very unhappy if she had to depend on other people for the rest of her life” |

| Family-related types of arguments | |||

|

Type 8: Psychological wellbeing of families 16/341 coded arguments (5%) |

Arguments of this type were mainly used by families and only occasionally by doctors. They were mainly put forward in support of continuation of LST | In a conversation, one of the doctors argued to start ventilation when necessary “to give you [the family] more time” | A relative expressed that “it just feels wrong to give up” in response to the advice the doctor had just given to discontinue LST |

|

Type 9: Family’s moral responsibility 8/341 coded arguments (2%) |

Arguments of this type concerned the moral responsibility which families felt for the patient’s life and wellbeing. They were only put forward by families and only in support of discontinuation. This type of arguments was the least frequently used type | Does not apply | A partner of a patient in the A-ICU was very worried about the risks of a specific LST and stated that she did not want “to be responsible for putting him in danger. I therefore would rather wish that this treatment will be withheld” |

| 'Deviating’ type of argument | |||

|

Type 10: Professional authority 26/341 coded arguments (8%) |

Arguments falling under this type referred to the authority of the individual doctor, the medical team, or medical expertise in general. Only doctors used this type of argument. They did so mainly to plea for discontinuation of LST. In doing so, they most often referred to the authority of the medical team | A doctor argued that “the whole medical team feels that if a ventilator becomes necessary, we should not be doing that anymore” | Does not apply |

Argumentation structure

We further explored how doctors and families structured their argumentation. An argumentation structure refers to the relation between a standpoint, main arguments, and sub-arguments. Examples of such relations in our study are visualized in supplementary A and B.

The standpoints focused on in our study were the standpoint that LST should be continued and the standpoint that LST should be discontinued. Occasionally doctors presented both standpoints in the same conversation. In most conversations, they put forward only one of these standpoints.

Doctors in the N-ICU and P-ICU mainly presented the standpoint to discontinue LST, also in the initial conversations. Doctors in the A-ICU slightly more often presented the standpoint to continue LST in the initial conversations. In later conversations, they predominantly presented than the standpoint to discontinue LST.

Looking into the standpoints presented by families, parents in the N-ICU mainly appeared to advocate the standpoint to continue LST in the first and over subsequent conversations. In the P-ICU, in the initial conversations, most parents put forward the standpoint to continue LST, whereas in later conversations, parents largely presented the standpoint that LST should be discontinued. Families in the A-ICU mainly argued in support of the standpoint to discontinue LST in the first and over subsequent conversations.

Main arguments and sub-arguments

In the vast majority of conversations, both doctors and families substantiated their standpoints with one or more main arguments. These main arguments were underpinned with sub-arguments in a minority of conversations. Table 2 provides a description of the ten main types of arguments.

If doctors or families argued for continuation of LST, they mostly presented one main argument, for example: “We should continue LST, because there is still too much uncertainty to stop treatment”. In the conversations in which doctors presented more than one argument to continue LST, this mostly concerned arguments referring to generally accepted healthcare standards and uncertainty, as illustrated by the next quote: “The test that we normally do in this kind of situation, showed that she responded to the stimuli. We therefore can’t rule out that she will wake up”. In conversations in which families presented more than one argument in favor of continuing LST, these arguments often concerned the following types: family’s moral responsibility and psychological wellbeing of families. This is illustrated by the next quote: “She must have this last chance, because otherwise I will always keep wondering ‘what if’”.

Doctors often substantiated their standpoint that LST should be discontinued with two or more main arguments. They mostly combined arguments regarding the following four types: patient’s quality of life, medical (in)effectiveness, professional authority, and/or proportionality. For example: “We should not give CPR, because it will not result in a well-functioning heart. On the contrary, it will cause more damage and this extra damage will be too much for her”.

In the few conversations in which families presented more than one argument in favor of discontinuation, these arguments concerned the patient’s quality of life in combination with their own moral responsibility, to illustrate: “We [as her family] must take into account her remaining quality of life and happiness”.

Because doctors and families often used only one main argument and infrequently substantiated their main arguments with sub-arguments, their line of arguing appeared to be rather abstract and vague. For example, doctors regularly argued that LST should be discontinued because “the treatment is not proportional anymore” without elaborating or explaining this (dis)proportionality. Similarly, families for instance argued that LST should be discontinued, because the patient “suffered”, without elaborating on their observations and without being invited to do so by the doctor. Despite the vagueness of the argumentation, doctors seldom asked open questions to explore what families meant. Families in turn did also seldom ask for further clarifications.

Argumentation dynamics

In almost all conversations, doctors were the first to argue and families followed, thereby either countering the doctor’s line of argumentation or substantiating it. Often, families did not immediately respond to the arguments presented by the doctor but did so much later in the conversation. Only in a minority of conversations, a true exchange of arguments (i.e., doctors and families responding to each other’s arguments by complementing or contradicting the other’s arguments) took place. This was mainly the case within the N-ICU. The exchange of arguments was generally quite brief in the sense that not all possible types of arguments were presented and then discussed together.

In response to doctors’ standpoint to discontinue LST, most parents in the N-ICU plead for continuation of LST and brought in new arguments. In their subsequent response, most doctors further substantiated their standpoint to discontinue LST with additional arguments. Still, the outcome of most exchanges was that LST would be continued for the time being. In the P-ICU, families argued as often in line with doctors’ previously presented standpoint as in the opposite direction. When they agreed with the doctor’s standpoint, they often broadened or deepened this standpoint by providing new or additional arguments. For example, a doctor argued that LST should not be continued, “because it is not in your child’s best interest”. In response, the parents put forward a new argument, namely that their child “suffered visibly, because she was often gasping for air and was not smiling as often anymore”. Families in the A-ICU mainly argued in line with the doctor’s standpoint to discontinue LST. They less often provided additional arguments than parents in the N-ICU and P-ICU.

In the conversations in which doctors and families did not exchange arguments, they presented their arguments as stand-alone arguments instead of being part of an overall argumentation structure. These conversations had two different outcomes. First, the treatment option that the doctor suggested was followed. Second, if families fiercely (i.e., repeatedly and/or extensively) argued for continuation of LST, a decision was postponed and a follow-up conversation was planned.

Almost none of the conversations ended with a kind of meta-discussion in which all exchanged arguments were summed up and weighed before an overall conclusion was drawn.

Discussion

We thoroughly explored which arguments doctors and families used to either argue that LST should be continued or discontinued, how they structured their arguments, and how their argumentative practices unfolded during conversations. In almost all conversations, doctors were the first to argue and families followed, thereby either countering the doctor’s line of argumentation or substantiating it. Arguments put forward by doctors and families in the conversations we analyzed fell under one of ten main types. The types of arguments presented by families largely overlapped with the types of arguments presented by doctors. A real exchange of arguments occurred in a minority of conversations and was generally quite brief. If families did respond to the arguments presented by the doctor, they often did so much later in the conversation.

The arguments presented by doctors in our study appeared to be largely consistent with recent professional guidelines in their content [15–26]. This consistency may be related to the highly protocolized care for critically ill patients over the last decades, including end-of-life decision-making. Then again, guidelines are adapted in response to actual (practice) developments within critical care. In that regard, it is of interest to see which of the arguments we identified are not represented in the current guidelines. We found two novel arguments, namely those referring to uncertainty and to professional authority.

The first novel argument type, referring to uncertainty, was frequently put forward by both doctors and families in all ICUs to plea for continuation of LST. This can partly be explained by the fact that technical innovations increasingly enable ICU teams to keep patients alive, in theory for as long as the patient or the patient’s legal representatives wish for—a few exceptions notwithstanding. Yet, the patient often pays a high price for his survival, including lasting severe disabilities and a permanent loss of independency. In this light, the patient’s quality of life in the short and long term has become a more and more decisive factor in making decisions about the continuation or discontinuation of LST. However, the assessment of the remaining quality of life is much more prone to uncertainty. Recent studies in which families of critically ill patients were interviewed also show that uncertainty is an important argument for families to ask for continuation of LST, at least until there is more certainty about prognosis and treatment effects [4, 33–42]. Studies also reveal that adequately discussing uncertainties improves both the decision-making process and the wellbeing of patients and their families [33–42]. Based on these findings, we recommend including uncertainty as a topic for discussion in professional guidelines concerning end-of-life decision-making in the ICU. This will not reduce the amount of uncertainty itself. Yet, addressing this issue in conversations with families may help them to better understand the recommended line of action and to come to term with their decision [4, 43].

The other novel argument, professional authority, can be regarded as deviating in the sense that one could question whether it is an argument or a persuasion technique [44]. That is, presenting a treatment option as an authorized decision suggests that a group of experts regards a certain option as the best option, and families of patients might not feel comfortable to disagree with the perceived best option [44]. In that sense, professional authority arguments may limit family participation in the decision-making process [44]. Arguments based on generally accepted healthcare standards and on comparisons can also function as participation limiting due to their steering character. That is, families may fear that they will not be able to forgive themselves in case of a negative outcome if they went against generally accepted healthcare standards [44]. Comparisons can steer toward a particular treatment decision, because they may impede the evaluation of the pros and cons of each option available [44]. Despite these drawbacks, references to professional authority, generally accepted healthcare standards, and comparisons may have an important function in conversations with families. These three types of arguments can underline that what the doctors do and say is based on professional, evidence-based standards. If worded clearly and empathically, this may well help families to understand and accept the suggested course of action. On the long term, it will reduce families’ feelings of doubt and guilt that treatment has either been withdrawn too early or too late [4]. These three argument types show that there is a thin dividing line between argumentation and persuasion [5, 44, 45]. Doctors should be aware of this and provide room for weighing of arguments. Doing so enables open, meaningful, and insightful discussions which stimulates well-considered and appropriate treatment decisions.

Regarding the argumentation structure and dynamics, doctors presented only the standpoint to continue LST or the standpoint to discontinue LST in most conversations. This was unexpected, since most of the conversations concerned decisions in the gray zone. These decisions are characterized by the fact that there is no clearly best treatment option, because all remaining treatment options have their pros and—often very serious—cons. In that light, it is important to explicitly discuss both options, including these pros and cons [27, 32]. It is important that doctors guide this process well and to maintain the right balance between inviting families to participate in the decision-making process and not overburdening them with too much responsibility.

We frequently observed a lack of concrete explanation and deepening of arguments and of summarizing all exchanged arguments. This raises the question whether doctors and families really understood each other’s arguments, especially since both parties seldom asked clarifying questions. This may add to mutual misunderstandings which in turn may well result in conflicting views between doctors and families [5, 46, 47]. Former studies have shown that true deliberation and a complete and extensive exchange of arguments and information will enhance both family satisfaction and the quality of the argumentation process, and by effect the treatment decision that is reached [6–14, 44, 48, 49]. Nevertheless, communication is much more than argumentation alone: it implies the building of true relationships, too. Communication requires synchronizing (non-)verbal messages between healthcare staff and families for the benefit of the patient and the family as a whole [3–5]. As each patient and family has their own communication needs and preferences, it is important for healthcare professionals to tailor their communication to those needs and preferences [3].

Limitations and strengths

We have pushed for maximum variation regarding the participating patients, their families, and their doctors. Still, selection bias may well have occurred. This limits the generalizability of our study. Another limitation is that we only audio-recorded conversations to minimize the intrusiveness of our data collection, which precluded the analysis of non-verbal communication. Moreover, we cannot rule out that the Hawthorne effect may have occurred due to the audio-recording of conversations [50]. Finally, this study describes the argumentative practices of doctors and families within one medical center only, which was unavoidable given the logistical demands of the study. It would be relevant to expand this study to other ICUs in the Netherlands and, preferably, to ICUs in other countries, thereby also multiplying the number of cases. This will enable investigating contextual and cultural influences on the argumentation practices of healthcare staff and families.

The main strength of this study is that we collected a large dataset of transcripts of real-life, highly sensitive conversations which we meticulously analyzed. Furthermore, we investigated the actual argumentation practices in three different ICUs.

Practice recommendations

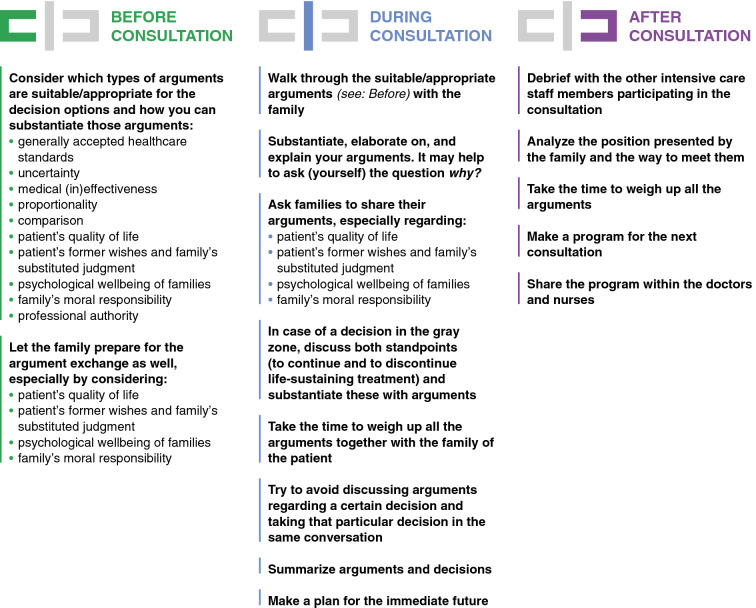

Doctors’ awareness of argumentation in end-of-life conversations may add to open and insightful discussions and to well-considered and appropriate treatment decisions. We present some hands-on recommendations in Fig. 3. Future research is needed to investigate how and to what extent best practice recommendations improve families’ and doctors’ experiences of the decision-making process, including their satisfaction with the communication.

Fig. 3.

Recommendations for doctors

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the trust of the participating families, doctors, and nurses. Moreover, we thank Maartje Harmelink and Joyce Lamerichs for their valuable assistance during the data collection phase of this study.

Author contributions

AA and MdV had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. AA, MdV, JW, NL, DW, MvdL, and ASp contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation. AA, SP, ASp, JW, NL, DW, MS, TC, JvW, MvH, AvK, MvdL, ASt, ES, and MdV contributed substantially to the writing of the manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AA and all authors commented on the previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is part of the research project ‘FamICom’, which was supported by ZonMw [Project No. 844001316]. ZonMw is the Dutch organization for healthcare research and innovation.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Compliance with ethical standards

The Amsterdam UMC institutional review board waived approval of this study (W17_475 # 17.548). All participants could withdraw their consent at any time.

Data management and sharing

Data and coding books are available upon request.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Curtis JR, Vincent JL. Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the intensive care unit. Lancet. 2010;376(9749):1347–1353. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Erin KK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, Netzer G, Kentish-Barnes N, Sprung CL, Hartog CS, Coombs M, Gerritsen RT, Hopkins RO, Franck LS, Skrobik Y, Kon AA, Scruth EA, Harvey MA, Lewis-Newby M, White DB, Swoboda SM, Cooke CR, Levy MM, Azoulay E, Curtis JR. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):103–128. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akkermans A, Lamerichs JMWJ, Schultz MJ, Cherpanath TGV, van Woensel JBM, van Heerde M, van Kaam AHCL, van de Loo MD, Stiggelbout AM, Smets EMA, de Vos MA. How doctors actually (do not) involve families in decisions to continue or discontinue life-sustaining treatment in neonatal, pediatric, and adult intensive care: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2021;35(10):1865–1877. doi: 10.1177/02692163211028079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prins S, Linn AJ, van Kaam AHLC, van de Loo M, van Woensel JBM, van Heerde M, Dijk PH, Kneyber MCJ, de Hoog M, Simons SHP, Akkermans A, Smets EMA, Hillen MA, de Vos MA. How physicians discuss uncertainty with parents in intensive care units. Pediatrics. 2022;149(6):e2021055980. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-055980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spijkers AS, Akkermans A, Smet EMA, Schultz MJ, Cherpanath TGV, van Woensel JBM, van Heerde M, van Kaam AH, van de Loo M, Willems DL, de Vos MA. How doctors manage conflicts with families of critically ill patients during conversations about end-of-life decisions in neonatal, pediatric, and adult intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(7):910–922. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06771-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akkermans A, Henkemans FS, Labrie N, Henselmans I, van Laarhoven HWM. Characteristics of argumentation in consultations about palliative systemic treatment for advanced cancer: an observational content analysis. In: van Eemeren F, Garssen B, editors. Argumentation in actual practice: topical studies about argumentative discourse in context. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2020. pp. 237–266. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigi S. The role of argumentative strategies in the construction of emergent common ground in a patient-centered approach to the medical encounter. J Argum Context. 2018;7(2):141–156. doi: 10.1075/jaic.18028.big. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Eemeren FH, Garssen BJ, Labrie NHM. Argumentation between doctors and patients: understanding clinical argumentative discourse. Amsterdam: Johns Benjamins; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snoeck Henkemans F, Labrie N, Pilgram R. Argumentation and patient centered care. J Argum Context. 2018;7(2):117–119. doi: 10.1075/jaic.18026.sno. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karnilie-Miller O, Neufeld-Kroszynski G. The potential of argumentation theory in enhancing patient-centered care in breaking bad news encounters. J Argum Context. 2018;7(2):120–137. doi: 10.1075/jaic.18023.kar. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munthe C, El-Alti L, Hatvigsson T, Nijsingh N. Disputing with patients in person-centered care: ethical aspects in standard care, pediatrics, psychiatry, and public health. J Argum Context. 2018;7(2):231–244. doi: 10.1075/jaic.18022.mun. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilgram R, Snoeck Henkemans F. A pragma-dialectical perspective on obstacles to shared decision-making. J Argum Context. 2018;7(2):177–180. doi: 10.1075/jaic.18027.pil. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilgram R (2015) A doctor’s argument by authority: an analytical and empirical study of strategic manoeuvring in medical consultation. Dissertation, University of Amsterdam

- 14.Rubinelli S, Snoeck Henkemans F. Argumentation and health. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canadian Critical Care Society Ethics Committee. Bandrauk N, Downar J, Paunovic B. Withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment: the Canadian Critical Care Society position paper. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65(1):105–122. doi: 10.1007/s12630-017-1002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamsi-Pasha H, Albar MA. Withdrawing or withholding treatment. IJHHS. 2017;1(2):59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Commissie Ethiek NVIC (2021) Leidraad Palliatieve Zorg En Staken Van Levensverlengende Behandelingen Bij Volwassen Ic-Patiënten. NVIC. https://www.nvic.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Einde-leven-leidraad-2.0-februari-2021.pdf. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

- 18.Health Professionals Council of South Africa (2016) Guidelines for the withholding and withdrawing of treatment. https://www.hpcsa.co.za/Uploads/Professional_Practice/Conduct%20%26%20Ethics/Booklet%207%20Guidelines%20withholding%20and%20withdrawing%20treatment%20September%202016.pdf. Accessed 8 Nov 2022

- 19.Joint Committee on Biomedical Ethics of the Los Angeles County Medical Association and Los Angeles County Bar Association (2006) Guidelines for physicians: forgoing life-sustaining treatment for adult patients. https://thaddeuspope.com/images/lacma-lacba-joint-comm-adult-guidelines-_3-22-06-final_1.pdf. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

- 20.Lesieur O, Leloup M, Gonzalez F, Mamzer MF, EPILAT study group, Withholding or withdrawal of treatment under French rules: a study performed in 43 intensive care units. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s13613-015-0056-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NVK (2022) Richtlijn Palliatieve Zorg voor Kinderen. https://palliaweb.nl/richtlijnen-palliatieve-zorg/richtlijn/palliatieve-zorg-voor-kinderen. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

- 22.Queensland Government (2017) Implementation guidelines end-of-life care: decision-making for withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining measures from patients under the age of 18 years. https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/PDF/qcycn/imp-guideline-eolc-part-1.pdf. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

- 23.Reignier J, Feral-Pierssens AL, Boulain T, Carpentier F, Le Borgne P, Del Nista D, Potel G, Dray S, Hugenschmitt D, Laurent A, Ricard-Hibon A, Vanderlinden T, Chouihed T, French Society of Emergency Medicine (Société Française de Médecine d’Urgence, SFMU), French Intensive Care Society (Société de Réanimation de Langue Française, SRLF) Withholding and withdrawing life-support in adults in emergency care: joint position paper from the French Intensive Care Society and French Society of Emergency Medicine. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):105. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0579-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka M, Kodama S, Lee I, Huxtable R, Chung Y. Forgoing life-sustaining treatment—a comparative analysis of regulations in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and England. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12910-020-00535-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The State of Queensland (Queensland Health) (2018) End-of-life care: guidelines for decision-making about withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining measures from adult patients. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0033/688263/acp-guidance.pdf. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

- 26.Weise KL, Okun AL, Carter BS, Christian CW, Committee on Bioethics, Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect Guidance on forgoing life-sustaining medical treatment. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20171905. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norman G (2014) What few appreciate: the gray zone of medical decisions, what few appreciate: the gray zone of medical decisions. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20140324195914-10808081-what-few-appreciate-the-gray-zone-of-medical-decisions/. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

- 28.Akkermans A, Prins S, Spijkers A, Wagemans J, Labrie N, Willems D, Schultz M, Cherpanath TGV, van Woensel JBM, van Heerde M, van Kaam AH, van de Loo M, Stiggelbout AM, Smets EMA, de Vos MA. Argumentation in end-of-life conversations with families in Dutch intensive care units. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2022;10(2):001069. doi: 10.1186/s40635-022-00468-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. Applied thematic analysis. London: SAGE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joffe H. Thematic analysis. In: Harper D, Thompson A, editors. Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: a guide for students and practitioners. Chichester: Wiley; 2011. pp. 163–223. [Google Scholar]

- 31.VERBI Software (2020) MAXQDA 2020 manual. https://www.maxqda.com/help-mx20/welcome. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

- 32.van Eemeren FH, Grootendorst R. A systematic theory of argumentation: the pragmadialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Branchett K, Stretton J. Neonatal palliative and end of life care: what parents want from professionals. J Neonatal Nurs. 2012;18(2):40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jnn.2012.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brashers DE. Communication and uncertainty management. J Commun. 2001;51(3):477–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2001.tb02892.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein RM, Street Jr. RL (2020) Patient centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 07-6225. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/pcc_monograph.pdf. Accessed 12 Feb 2023

- 36.Han PKJ, Klein WMP, Arora NK. Varieties of uncertainty in health care: a conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Mak. 2011;31(6):828–838. doi: 10.1177/0272989x11393976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haward MF, Murphy RO, Lorenz JM. Message framing and perinatal decisions. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):109–118. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hillen MA, Gutheil CM, Strout TD, Smets EMA, Han PKJ. Tolerance of uncertainty: conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Soc Sci Med. 2017;180:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Labrie NHM, van Veenendaal NR, Ludolph RA, Ket JCF, van der Schoor SRD, van Kempen AAMW. Effects of parent-provider communication during infant hospitalization in the NICU on parents: a systematic review with meta-synthesis and narrative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(7):1526–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meert KL, Eggly S, Pollack M, Anand KJS, Zimmerman J, Carcillo J, Newth CJL, Dean JM, Willson DF, Nicholson C. Parents’ perspectives on physician-parent communication near the time of a child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(1):2–7. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000298644.13882.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaefer KG, Block SD. Physician communication with families in the ICU: evidence-based strategies for improvement. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15(6):569–577. doi: 10.1097/mcc.0b013e328332f524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong P, Liamputtong P, Koch S, Rawson H. Barriers to regaining control within a constructivist grounded theory of family resilience in ICU: living with uncertainty. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(23–24):4390–4403. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medendorp NM, Stiggelbout AM, Aalfs CM, Han PKJ, Smets EMA, Hillen MA. A scoping review of practice recommendations for clinicians’ communication of uncertainty. Health Expect. 2021;24(4):1025–1043. doi: 10.1111/hex.13255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engelhardt EG, Pieterse AH, Stiggelbout AM. Implicit persuasion in medical decision-making. An overview of implicitly steering behaviors and a reflection on explanations for the use of implicitly steering behaviors. J Argum Context. 2018;7(2):209–227. doi: 10.1075/jaic.18032.eng. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Eemeren FH. Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse: extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Burns JP, Puopolo AL, Galper BZ, Truog RD, Brennan TA. Conflict in the care of patients with prolonged stay in the ICU: types, sources, and predictors. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1489–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zante B, Schefold JC. Teaching end-of-life communication in intensive care medicine: review of the existing literature and implications for future curricula. J Intensive Care Med. 2017;34(4):301–310. doi: 10.1177/0885066617716057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, Cassell J, Cox P, Hill N, Hinds C, Pimentel JM, Reinhart K, Thompson BT. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU. Statement of the 5th international consensus conference in critical care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:770–784. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Peters S, Tranmer JE, O'Callaghan CJ. Decision making in the ICU: perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Franke RH, Kaul JD. The Hawthorne experiments: first statistical interpretation. Am Sociol Rev. 1978;43:623–643. doi: 10.2307/2094540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.