Acute otitis media (AOM) is the most common diagnosis associated with antibiotics in children in the United States, resulting in 10 million antibiotic prescriptions annually. Current American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the management of AOM recommend that most children with nonsevere AOM be treated with observation or a delayed prescription (a prescription to be filled only if the child’s health worsens or is not improved), rather than an immediate antibiotic.1 When an antibiotic is prescribed, amoxicillin is recommended as first-line therapy for most children, and 5 to 7 days of therapy is recommended for children 2 years or older, as appropriate. Despite these recommendations, more than 95% of children with AOM are prescribed an antibiotic of which more than 95% are immediate and 94% are for a duration of 10 days, including for those 2 years or older.2 While amoxicillin is the most frequently prescribed antibiotic for AOM because of its high activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae, nearly 40% of antibiotics prescribed are broad spectrum (any nonamoxicillin antibiotic), primarily composed of cefdinir and azithromycin.

Microbiology and Spontaneous Resolution

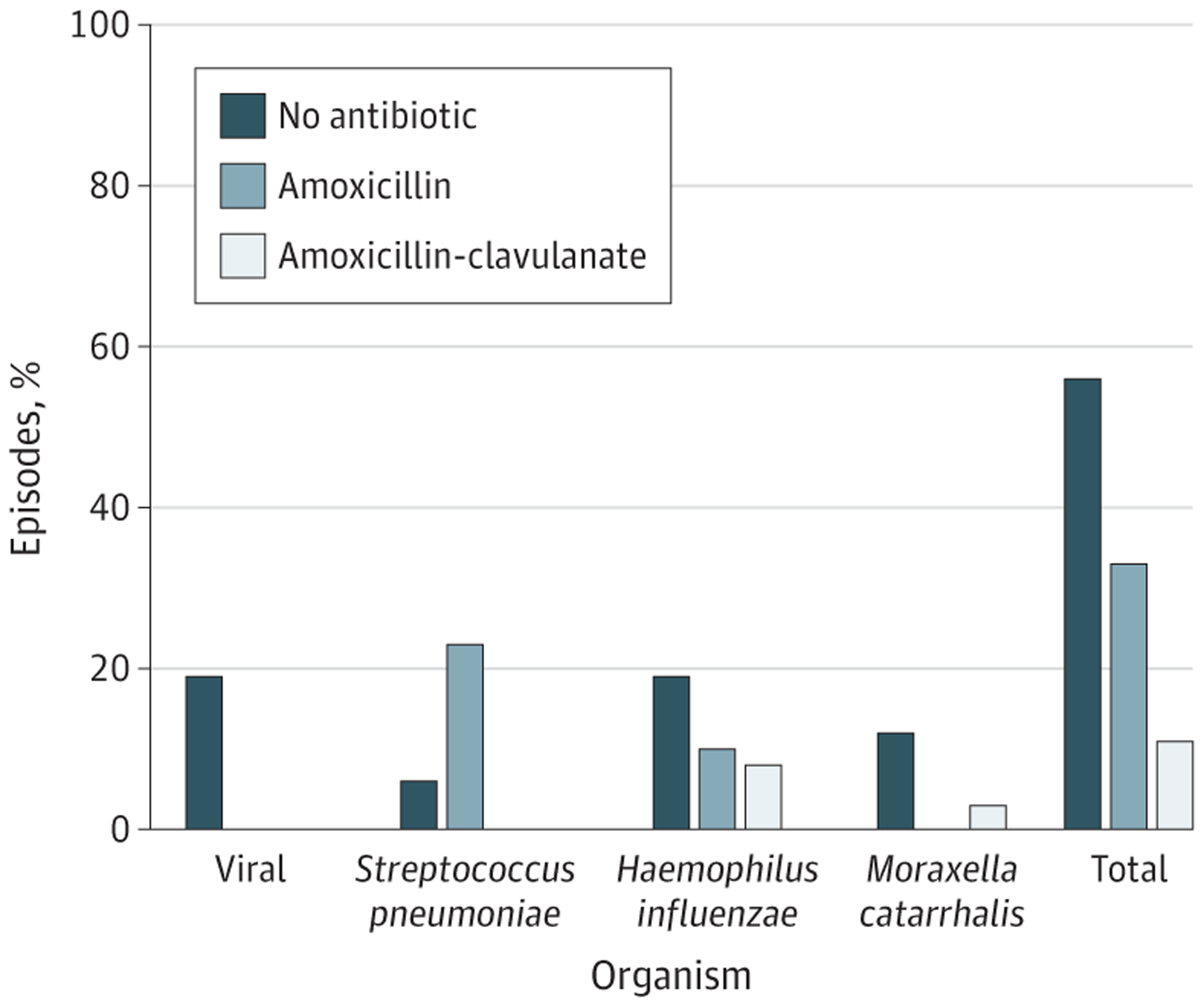

The introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) 7 in 2000 and 13 in 2010 has led to an overall decrease in AOM episodes and a change in the proportion of AOM episodes caused by each otopathogen. Whereas S pneumoniae previously predominated, Haemophilus influenzae is now the most common otopathogen and the proportion of cases associated with Moraxella catarrhalis has also increased.3 This shift has important implications for AOM management because the spontaneous resolution rates of AOM associated with H influenzae (48%) and M catarrhalis (75%) are higher than for AOM associated with S pneumoniae (19%).4 Thus, as we see more infections caused by H influenzae and M catarrhalis, fewer AOM episodes are expected to benefit from antibiotics. This is further illustrated by an increase in the number needed to treat for symptomatic benefit in the post-PCV compared with pre-PCV era. Whereas symptomatic benefit was evident for 1 of every 15 children treated with an antibiotic in the pre-PCV era, benefit is evident for only 1 of every 20 childrenin the post-PCV era (25% relative increase).2 In fact, clinical data indicate that 78% to 85% of AOM episodes in the post-PCV era self-resolve.2 The Figure shows the proportion of AOM episodes expected to self-resolve based on the current microbiology. Thus, given the high self-resolution rates and high number needed to treat for symptomatic benefit, nearly 75% of antibiotics currently prescribed for AOM in the United States may be potentially unnecessary.

Figure.

Percentage of Acute Otitis Media Episodes Expected to Be Best Treated by No Antibiotic, Amoxicillin, and Amoxicillin-Clavulanate

Percentages are based on the otopathogen distribution and spontaneous resolution rates for children 2 years and younger. For older children, the percentage expected to resolve without an antibiotic is higher than shown here.

The unnecessary use of antibiotics causes significant harms to children. In addition to the development of antibiotic-resistant organisms, the overuse of antibiotics for AOM is estimated to result in 2.5 million parent-reported adverse drug events annually and increases risk for Clostridium difficile infections and chronic diseases later in life.5 In effect, for every 20 children treated with antibiotics, 1 child is likely to benefit while 5 are likely to experience harm.

Microbiology and Antibiotic Agent Selection

The change in microbiology also has significant implications for antibiotic selection. While amoxicillin is effective for S pneumoniae, nearly half of H influenzae isolates and most M catarrhalis isolates produce beta-lactamase rendering them nonsusceptible to amoxicillin. The change in otopathogens has prompted some to call for a change in first-line treatment from amoxicillin to amoxicillin-clavulanate for most children. The Figure shows the small number of children who would be expected to benefit from amoxicillin-clavulanate based on the microbiology. In clinical practice, the actual resolution rates of AOM treated with narrow- vs broad-spectrum antibiotics are 96.9% and 96.6%, respectively, in the post-PCV era.5 Therefore, the proportion of children who would benefit from a broad-spectrum antibiotic remains low even though the otopathogen distribution has shifted toward pathogens that are less susceptible to amoxicillin. This is likely from the increase in the prevalence of organisms that are more likely to self-resolve owing to a typically benign clinicalcourse and overdiagnosis in real-world settings. In contrast, a change from narrow- to broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing would result in a significant increase in antibiotic-associated morbidity because adverse drug events (36% vs 25%), reduction in quality of life, C difficile infections, and the development of antibiotic resistance organisms are greater for broad-spectrum antibiotics, compared with narrow-spectrum antibiotics.5

How Can We Reduce Unnecessary Antibiotic Exposure for AOM?

Pragmatic, broad-reaching approaches are needed to reduce unnecessary prescribing for AOM. We need to shift our paradigm from focusing primarily on the optimal antibiotic prescribing regimen based on in vitro match to otopathogens to emphasizing that most children with AOM do not benefit from antibiotics and should solely receive symptomatic therapy. For children who do not benefit, antibiotics are exclusively associated with harms. For clinicians and parents, the framework needs to shift to defaulting to symptom management with no antibiotic, with an antibiotic required only in select circumstances, or if a child’s health does not improve. This could be practically accomplished by routine use of observation or delayed prescribing. Both strategies effectively reduce antibiotic use with favorable clinical outcomes and high parental satisfaction. In contrast to beliefs that not treating with antibiotics might result in permanent, serious complications, complications from untreated AOM are exceedingly rare. Perhaps, these beliefs stem from an assumption that if all viral infections do not benefit from antibiotics that all bacterial infections require one (similar to treatment of gram-negative sepsis where mortality is high). A cultural reset among clinicians and parents is needed to amend this assumption because it has implication for other diagnoses such as sinusitis, which is caused by the same pathogens and often resolves without an antibiotic.

Interventions to reduce prescribing of immediate antibiotics, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and durations of antibiotics that are longer than necessary for AOM have proven effective in select clinical settings. Additionally, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and American Academy of Pediatrics have released tools, such as the Core Elements of Outpatient Stewardship6 and the Antibiotic Change Package7 to aid practices in outpatient stewardship. Future studies that focus on dissemination and implementation of effective interventions particularly in different clinical environments (eg, family medicine, emergency medicine) are needed to reduce unnecessary prescribing.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dr Frost reports salary support from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (grant K23HD099925). No other disclosures were reported.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Holly M. Frost, Department of Pediatrics, Denver Health and Hospital Authority, Denver, Colorado; and Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora..

Adam L. Hersh, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City..

REFERENCES

- 1.Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e964–e999. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venekamp RP, Sanders SL, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB, Rovers MM. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6): CD000219. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000219.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur R, Morris M, Pichichero ME. Epidemiology of acute otitis media in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3): e20170181. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein JO. Otitis media. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19(5): 823–833. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.5.823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerber JS, Ross RK, Bryan M, et al. Association of broad- vs narrow-spectrum antibiotics with treatment failure, adverse events, and quality of life in children with acute respiratory tract infections. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2325–2336. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez GV, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(6):1–12. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6506a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics. Chapter quality network improving antibiotic prescribing for children: change package. Accessed April 03, 2021. https://downloads.aap.org/DOCCSA/CQN%20ABX%20Change%20Package%20Final%20October%202019.pdf”https://www.aap.org/enus/professional-resources/quality-improvement/quality-improvement-resources-and-tools/Pages/antibiotic-stewardship.aspx”