ABSTRACT

Aims

This cross‐sectional study assessed the association of serum dehydroepiandrosterone levels with the risk of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in China.

Materials and Methods

Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the association of dehydroepiandrosterone with diabetic retinopathy after adjusting for confounding factors. A restricted cubic spline was also used to model the association of serum dehydroepiandrosterone level with the risk of diabetic retinopathy and to describe the overall dose–response correlation. Additionally, an interaction test was conducted in the multivariate logistic regression analysis to compare the effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on diabetic retinopathy among age, sex, obesity status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and glycosylated hemoglobin level subgroups.

Results

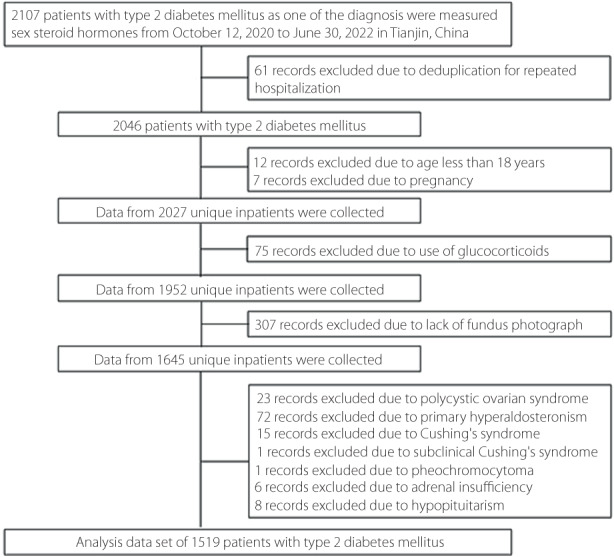

In total, 1,519 patients were included in the final analysis. Low serum dehydroepiandrosterone was significantly associated with diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus after adjustment for confounding factors (odds ratio [quartile 4 vs quartile 1]: 0.51; 95% confidence interval: 0.32–0.81; P = 0.012 for the trend). Additionally, the restricted cubic spline indicated that the odds of diabetic retinopathy decreased linearly as the dehydroepiandrosterone concentration increased (P‐overall = 0.044; P‐nonlinear = 0.364). Finally, the subgroup analyses showed that the dehydroepiandrosterone level stably affected diabetic retinopathy (all P for interaction >0.05).

Conclusions

Low serum dehydroepiandrosterone levels were significantly associated with diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, suggesting that dehydroepiandrosterone contributes to the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy.

Keywords: Dehydroepiandrosterone, Diabetes mellitus, type 2, Diabetic retinopathy

Low serum dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) was found to be statistically associated with diabetic retinopathy (DR) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus after adjustment for traditional risk factors. The restricted cubic spline further indicated that the odds of diabetic retinopathy decreased linearly with the increase of DHEA concentrations. The subgroup analysis stratified according to age, sex, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and HbA1c, also showed stable effect of DHEA on diabetic retinopathy.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic retinopathy (DR), a common microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus (DM), remains the leading cause of vision impairment and blindness in adults 1 . Worldwide, the number of adults with diabetic retinopathy was estimated to be 103.12 million in 2020 and is expected to increase to 160.50 million by 2045 2 . In China, 18.45% of patients with diabetes mellitus have diabetic retinopathy 3 , and the independent risk factors for diabetic retinopathy are younger age, higher systolic blood pressure (SBP), longer duration of diabetes mellitus, and poor glycemic control 4 . However, despite these traditional indicators of risk, wide variations in the development and severity of diabetic retinopathy exist which cannot be completely explained by these known factors 5 . Therefore, diabetic retinopathy risk factors are not fully understood.

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), an androgen precursor, is an abundant steroid hormone in human circulation. Previous studies have reported that DHEA improves endothelial cell function, inhibits inflammation, and reverses vascular remodeling 6 , 7 . Low DHEA levels are associated with the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) in the general population and individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus 8 , 9 . Furthermore, our previous study demonstrated an inverse relationship between low serum DHEA and diabetic kidney disease (DKD) in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus 10 . In recent years, the point of a unifying mechanism has been raised in the pathogenesis of micro‐ and macrovascular complications of diabetes mellitus. These common pathogenic pathways included the production of reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, and chronic low‐grade inflammation 11 . In animal experiments, DHEA attenuated the adverse effects of hyperglycemia on bovine retinal pericytes 12 . However, the association of DHEA with the risk of diabetic retinopathy remains unclear in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Therefore, this cross‐sectional study assessed the association of DHEA with the risk of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

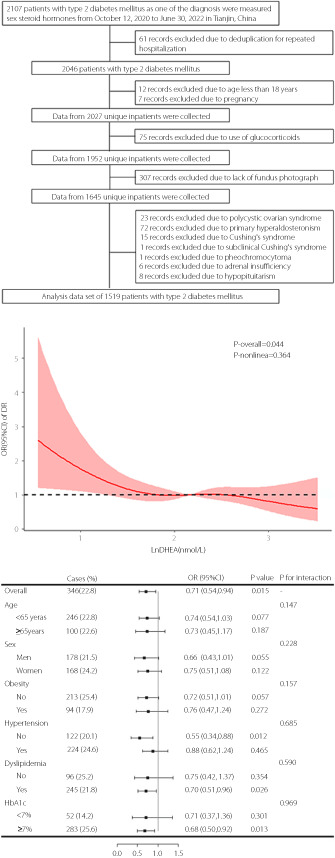

This cross‐sectional study was conducted at the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital in Tianjin, China. Hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were enrolled and DHEA measured between October 12, 2020, and June 30, 2022. The patients were admitted for glycemic control and evaluation of diabetic complications. The type of diabetes mellitus was determined by physicians based on clinical features, including the onset age, acute or chronic onset, body mass index (BMI), fasting or post glucose‐challenge insulin and C‐peptide levels, insulin dependence, and pancreatic beta cell autoantibodies if necessary. If multiple medical records for one patient existed, only one of the patient's records was included. The exclusion criteria were: age <18 years, pregnancy, use of glucocorticoids or sex hormones, polycystic ovarian syndrome, hypopituitarism, and adrenal disease, including primary hyperaldosteronism, Cushing's syndrome, subclinical Cushing's syndrome, pheochromocytoma, and adrenal insufficiency. Moreover, participants without fundus photograph information were excluded. None of the participants enrolled in this study used DHEA. Figure 1 details the study population identification process.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the identification of the study population. There were 1,519 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus involved in the final analysis.

The Institutional Review Board of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital approved this study (approval number: IRB2020‐YX‐027‐01) and waived the informed consent requirement because the data were gathered from electronic medical records, and the participants’ identities were anonymized.

Data collection

Clinical data for each participant were extracted from electronic medical records, including age, sex, height, body weight, medical insurance type, smoking and drinking status, medical history (type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease [CVD]), SBP, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), lipid profiles, fasting blood glucose (FBG) level, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level, uric acid concentration, creatinine level, the urine albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR), and medication use (hypotensive, lipid‐lowering, and glucose‐lowering medications). The BMI was calculated as the participant's weight (kg) divided by height (meters) squared. Obesity was defined as a BMI >27.5 kg/m2 13 . The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation 14 .

The serum DHEA concentration was quantified using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry as described previously 10 , 15 . Briefly, fasting blood samples were collected in the morning after admission and immediately sent to the Laboratory of Endocrinology and Metabolism at the Tianjin Medical University General Hospital. Two professionals pre‐treated the samples following uniform standards and then loaded them into a Jasper™ HPLC system coupled to an AB SCIEX Triple Quad™ 4500MD mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) to measure DHEA.

Definitions

Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting blood glucose level ≥7.0 mmol/L, a 2 hour plasma glucose level ≥11.1 mmol/L, an HbA1c level ≥6.5%, a self‐reported history of diabetes mellitus, or the use of hypoglycemic medications 16 . Hypertension was defined as an SBP ≥140 mmHg, a DBP ≥90 mmHg, a self‐reported history of hypertension, or the use of hypotensive medications 17 . Dyslipidemia was defined as a total cholesterol (TC) level ≥6.2 mmol/L, a triglyceride (TG) level ≥2.3 mmol/L, a low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) level ≥4.1 mmol/L, a high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C) level <1.0 mmol/L, or the use of lipid‐lowering medications 18 . Diabetic kidney disease was defined as an albumin to creatinine ratio value >30 mg/g or an eGFR level <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 19 .

Experienced and trained specialists took standard non‐mydriatic fundus photographs to evaluate diabetic retinopathy. Diabetic retinopathy was diagnosed based on microaneurysms, hard exudates, cotton wool spots, intraretinal hemorrhages, venous beading changes, intraretinal microvascular anomalies, neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage, or tractional retinal detachment 20 . The International Classification of Diabetic Retinopathy Scale 20 defines sight‐threatening diabetic retinopathy as severe non‐proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) or diabetic macular edema. Thus, the patients were divided into non‐diabetic retinopathy, non‐sight‐threatening diabetic retinopathy (i.e., mild or moderate NPDR), and sight‐threatening diabetic retinopathy (i.e., severe NPDR, PDR or diabetic macular edema) groups.

Statistical analyses

Normally distributed continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation, and between‐group comparisons were performed using Student's t‐tests or one‐way analysis of variance. Non‐normally distributed variables were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges, and between‐group comparisons were conducted using Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests. Categorical variables were described as numbers with percentages, and between‐group comparisons were performed using the chi‐squared tests.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the association of DHEA with diabetic retinopathy after adjusting for confounding factors. Potential confounders were determined according to univariate findings (including the insurance type, BMI, duration of diabetes mellitus, SBP, DBP, and diabetic kidney disease [yes/no], the HDL‐C, FBG, and HbA1c levels, the use of metformin, α‐glucosidase inhibitors, and insulin [all P < 0.05]) and literature reports (including age) 4 , 21 . The serum DHEA levels were equally categorized into quartiles, and the lowest quartile was used as a reference. The restricted cubic spline with four knots (5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles) was used to model the association of DHEA with diabetic retinopathy and to depict the overall dose–response correlation.

Moreover, subgroup analyses were performed to determine the relationship between DHEA and diabetic retinopathy based on the following subgroups: age (<65 or ≥65 years), sex, obesity status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and HbA1c (<7.0 or ≥7.0%). An interaction test in the logistic regression analyses was used to compare the effects of DHEA on diabetic retinopathy between the analyzed subgroups. The DHEA data were log‐transformed with the base natural constant in the logistic regression analyses and restricted cubic spline. A two‐sided P‐value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 25.0; Armonk, NY, USA) and R software (version 4.1.3; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of participants

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the participants based on the DHEA quartiles. During the study period, 2,107 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were hospitalized, and 1,519 participants were included in the analysis; 826 (54.4%) were men, and the mean overall age was 55.60 ± 14.17 years. The prevalences of non‐sight‐threatening diabetic retinopathy and sight‐threatening diabetic retinopathy were 20.3% and 2.4%, respectively. The median duration of diabetes mellitus was 7.00 (1.00–15.00) years. The mean fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels were 7.77 ± 2.89 mmol/L and 8.68 ± 2.21%, respectively. Participants in the higher quartiles were younger, had a shorter duration of diabetes mellitus, and had fewer instances of diabetic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and medication use (hypotensive and lipid‐lowering medications, sulfonylureas, metformin, α‐glucosidase inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, and insulin) than those in the lower quartiles (all P < 0.05). Furthermore, BMI, DBP, eGFR, and the TC, TG, LDL‐C, FBG levels significantly trended upward, whereas the ACR significantly trended downward (all P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients categorized by quartiles of DHEA level

| Variables | Overall | Quartiles of DHEA level | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | |||

| Participants | 1,519 | 380 | 308 | 379 | 380 | – |

| Age, years | 55.60 ± 14.17 | 63.14 ± 11.32 | 58.57 ± 12.26 | 53.69 ± 13.41 | 46.99 ± 14.25 | <0.001 |

| Male sex, % | 826 (54.4) | 196 (51.6) | 230 (60.5) | 201 (53.0) | 199 (52.4) | 0.048 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.15 ± 5.46 | 26.33 ± 4.36 | 26.79 ± 4.96 | 27.39 ± 6.16 | 28.04 ± 6.00 | <0.001 |

| Current smoking, % | 432 (28.5) | 88 (23.3) | 126 (33.2) | 117 (31.0) | 101 (26.6) | 0.012 |

| Current drinking, % | 407 (26.9) | 83 (22.0) | 113 (29.7) | 105 (27.8) | 106 (28.0) | 0.084 |

| Insurance type, % | ||||||

| Urban workers | 1,262 (83.1) | 310 (81.6) | 330 (86.8) | 325 (85.8) | 297 (78.2) | 0.013 |

| Non‐working urban residents | 179 (11.8) | 48 (12.6) | 36 (9.5) | 42 (11.1) | 53 (13.9) | |

| Self‐pay | 78 (5.1) | 22 (5.8) | 14 (3.7) | 12 (3.2) | 30 (7.9) | |

| Duration of type 2 diabetes, year | 7.00 (1.00, 15.00) | 10.00 (3.00, 20.00) | 10.00 (2.00, 17.00) | 7.00 (1.00, 13.00) | 3.00 (0.16, 10.00) | <0.001 |

| DR status, % | ||||||

| Non‐DR | 1,173 (77.2) | 267 (70.3) | 297 (78.2) | 291 (76.8) | 318 (83.7) | 0.002 |

| Non‐sight‐threatening DR | 309 (20.3) | 100 (26.3) | 74 (19.5) | 77 (20.3) | 58 (15.3) | |

| Sight‐threatening DR | 37 (2.4) | 13 (3.4) | 9 (2.4) | 11 (2.9) | 4 (1.1) | |

| DKD, % | 447 (31.9) | 157 (44.0) | 120 (33.7) | 84 (23.9) | 86 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| CVD, % | 334 (22.0) | 130 (34.2) | 96 (25.3) | 70 (18.5) | 38 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 911 (60.0) | 259 (68.2) | 254 (66.8) | 213 (56.2) | 185 (48.7) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 1,122 (74.7) | 310 (82.4) | 270 (72.4) | 282 (75.0) | 260 (68.8) | <0.001 |

| Use of hypotensive medications, % | 759 (50.2) | 238 (62.8) | 217 (57.4) | 173 (46.0) | 131 (34.6) | <0.001 |

| Use of lipid‐lowering medications, % | 389 (25.7) | 145 (38.3) | 101 (26.6) | 77 (20.4) | 66 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| Glucose‐lowering medications | ||||||

| Sulfonylureas, % | 195 (13.1) | 67 (18.3) | 49 (13.1) | 51 (13.7) | 28 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Glinides, % | 95 (6.4) | 29 (7.9) | 28 (7.5) | 16 (4.3) | 22 (5.8) | 0.164 |

| Metformin, % | 575 (38.6) | 155 (42.3) | 160 (42.8) | 141 (37.9) | 119 (31.6) | 0.005 |

| Thiazolidinediones, % | 32 (2.1) | 9 (2.5) | 12 (3.2) | 7 (1.9) | 4 (1.1) | 0.220 |

| α‐glucosidase inhibitors, % | 504 (33.8) | 161 (44.0) | 140 (37.4) | 116 (31.2) | 87 (23.1) | <0.001 |

| DPP‐4 inhibitors, % | 192 (12.9) | 55 (15.0) | 57 (15.2) | 45 (12.1) | 35 (9.3) | 0.048 |

| GLP‐1 receptor agonists, % | 97 (6.5) | 23 (6.3) | 16 (4.3) | 34 (9.1) | 24 (6.4) | 0.062 |

| SGLT‐2 inhibitors, % | 167 (11.2) | 47 (12.8) | 42 (11.2) | 45 (12.1) | 33 (8.8) | 0.313 |

| Insulin, % | 513 (34.5) | 157 (42.9) | 146 (39.0) | 114 (30.6) | 96 (25.5) | <0.001 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | ||||||

| Systolic | 136.59 ± 18.07 | 137.14 ± 19.32 | 137.13 ± 17.55 | 136.04 ± 18.17 | 136.04 ± 17.19 | 0.708 |

| Diastolic | 83.11 ± 11.92 | 81.02 ± 11.47 | 82.23 ± 11.70 | 83.66 ± 11.33 | 85.53 ± 12.70 | <0.001 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.98 ± 1.57 | 4.71 ± 1.32 | 4.84 ± 1.24 | 5.19 ± 1.72 | 5.18 ± 1.84 | <0.001 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.75 (1.27, 2.54) | 1.62 (1.18, 2.26) | 1.78 (1.27, 2.40) | 1.83 (1.32, 2.72) | 1.83 (1.29, 3.00) | 0.001 |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L | 1.08 ± 0.26 | 1.06 ± 0.28 | 1.06 ± 0.25 | 1.09 ± 0.26 | 1.10 ± 0.26 | 0.065 |

| LDL‐C, mmol/L | 3.01 ± 0.98 | 2.81 ± 1.02 | 2.95 ± 0.92 | 3.10 ± 0.95 | 3.15 ± 1.00 | <0.001 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 7.77 ± 2.89 | 7.49 ± 2.87 | 7.66 ± 2.80 | 7.85 ± 3.06 | 8.08 ± 2.79 | 0.038 |

| HbA1c, % | 8.68 ± 2.21 | 8.71 ± 2.34 | 8.72 ± 2.22 | 8.62 ± 2.17 | 8.67 ± 2.11 | 0.939 |

| Uric acid, μmol/L | 342.38 ± 104.00 | 343.80 ± 108.65 | 345.13 ± 101.88 | 342.14 ± 104.15 | 338.43 ± 101.46 | 0.833 |

| eGFR, mL/(min*1.73 m2) | 105.82 ± 24.15 | 95.11 ± 24.69 | 100.31 ± 24.53 | 110.31 ± 20.88 | 117.66 ± 19.58 | <0.001 |

| ACR, mg/g | 15.00 (7.30, 39.65) | 20.20 (9.78, 90.17) | 15.02 (7.83, 47.38) | 12.85 (7.00, 28.53) | 13.30 (6.40, 29.55) | <0.001 |

ACR, albumin to creatinine ratio; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; DPP‐4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4; DR, diabetic retinopathy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FBG, fasting blood glucose; GLP‐1, glucagon‐like peptide‐1; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL‐C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; SGLT‐2, sodium‐glucose cotransporter‐2; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Table 2 provides the clinical characteristics of the study population based on the diabetic retinopathy status. Overall, 346 of 1,519 patients (22.8%) had diabetic retinopathy. Those with diabetic retinopathy had a longer duration of diabetes mellitus, more instances of diabetic kidney disease and hypertension, and higher SBP, DBP, ACR, HDL‐C, FBG, and HbA1c, but lower BMI and eGFR values than those without diabetic retinopathy (all P < 0.05). Furthermore, patients with diabetic retinopathy were more likely to use metformin, α‐glucosidase inhibitors, and insulin than those without diabetic retinopathy (all P < 0.05). Finally, the proportion of medical insurance type significantly differed between patients with and without diabetic retinopathy (P = 0.025).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients categorized by the presence of diabetic retinopathy

| Variables | Non‐DR | DR | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, % | 1,173 (77.2) | 346 (22.8) | – |

| Age, years | 55.25 ± 14.53 | 56.77 ± 12.86 | 0.062 |

| Male sex, % | 648 (55.2) | 178 (51.4) | 0.213 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.42 ± 5.62 | 26.22 ± 4.75 | <0.001 |

| Current smoking, % | 343 (29.3) | 89 (25.9) | 0.214 |

| Current drinking, % | 325 (27.8) | 82 (23.8) | 0.147 |

| Insurance type, % | |||

| Urban workers | 989 (84.3) | 273 (78.9) | 0.025 |

| Non‐working urban residents | 124 (10.6) | 55 (15.9) | |

| Self‐pay | 60 (5.1) | 18 (5.2) | |

| Duration of type 2 diabetes, year | 6.00 (0.50, 13.00) | 10.00 (4.00, 19.00) | <0.001 |

| DKD, % | 286 (26.4) | 161 (50.5) | <0.001 |

| CVD, % | 251 (21.4) | 83 (24.0) | 0.310 |

| Hypertension, % | 687 (58.6) | 224 (64.7) | 0.039 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 877 (75.5) | 245 (71.8) | 0.176 |

| Use of hypotensive medications, % | 579 (49.5) | 180 (52.6) | 0.306 |

| Use of lipid‐lowering medications, % | 301 (25.7) | 88 (25.6) | 0.957 |

| Glucose‐lowering medications | |||

| Sulfonylureas, % | 140 (12.2) | 55 (16.2) | 0.052 |

| Glinides, % | 73 (6.3) | 22 (6.5) | 0.925 |

| Metformin, % | 423 (36.8) | 152 (44.8) | 0.007 |

| Thiazolidinediones, % | 26 (2.3) | 6 (1.8) | 0.584 |

| α‐Glucosidase inhibitors, % | 357 (31.0) | 147 (43.4) | <0.001 |

| DPP‐4 inhibitors, % | 138 (12.0) | 54 (15.9) | 0.058 |

| GLP‐1 receptor agonists, % | 76 (6.6) | 21 (6.2) | 0.786 |

| SGLT‐2 inhibitors, % | 129 (11.2) | 38 (11.2) | 0.997 |

| Insulin, % | 336 (29.2) | 177 (52.2) | <0.001 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||

| Systolic | 135.63 ± 17.26 | 139.84 ± 20.26 | 0.001 |

| Diastolic | 82.74 ± 11.45 | 84.36 ± 13.32 | 0.041 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.95 ± 1.60 | 5.07 ± 1.43 | 0.221 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.76 (1.27, 2.56) | 1.69 (1.25, 2.48) | 0.141 |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L | 1.06 ± 0.26 | 1.12 ± 0.27 | <0.001 |

| LDL‐C, mmol/L | 2.99 ± 0.98 | 3.07 ± 1.00 | 0.189 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 7.66 ± 2.76 | 8.15 ± 3.23 | 0.012 |

| HbA1c, % | 8.57 ± 2.20 | 9.07 ± 2.21 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid, μmol/L | 343.12 ± 103.97 | 339.92 ± 104.22 | 0.618 |

| eGFR, mL/(min*1.73 m2) | 107.30 ± 23.19 | 100.82 ± 26.56 | <0.001 |

| ACR, mg/g | 13.50 (6.99, 29.28) | 28.05 (9.43, 170.58) | <0.001 |

ACR, albumin to creatinine ratio; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; DPP‐4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4; DR, diabetic retinopathy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FBG, fasting blood glucose; GLP‐1, glucagon‐like peptide‐1; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL‐C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; SGLT‐2, sodium‐glucose cotransporter‐2; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

DHEA associations with diabetic retinopathy

Table 3 presents the odds ratios (ORs) for the association of DHEA with diabetic retinopathy in three models. The diabetic retinopathy odds decreased significantly as the DHEA level increased incrementally in model 1 (unadjusted; OR [quartile 4 compared with quartile 1]: 0.46; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.33–0.65; P < 0.001 for the trend). Furthermore, a low serum DHEA level remained statistically associated with diabetic retinopathy after adjusting for age, insurance type, BMI, duration of diabetes mellitus, SBP, DBP, diabetic kidney disease, HDL‐C, FBG, HbA1c, and the use of metformin, α‐glucosidase inhibitors, and insulin in model 3 (OR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.32–0.81; P = 0.012 for the trend). Moreover, when DHEA was log‐transformed with the base natural constant and analyzed as a continuous variable, a significant association between DHEA and diabetic retinopathy risk remained after adjusting for the abovementioned variables (OR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.54–0.94; P = 0.015).

Table 3.

Odds ratios of diabetic retinopathy by different status of DHEA

| No. of participants | No. of cases | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Quartile 1 | 380 | 113 | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Quartile 2 | 380 | 83 | 0.66 (0.48, 0.92) | 0.013 | 0.68 (0.49, 0.95) | 0.022 | 0.56 (0.37, 0.85) | 0.006 |

| Quartile 3 | 379 | 88 | 0.72 (0.52, 0.99) | 0.042 | 0.74 (0.52, 1.03) | 0.076 | 0.70 (0.46, 1.07) | 0.102 |

| Quartile 4 | 380 | 62 | 0.46 (0.33, 0.65) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.32, 0.69) | <0.001 | 0.51 (0.32, 0.81) | 0.005 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.012 | |||||

| As a continuous variable † | 1,519 | 346 | 0.66 (0.54, 0.81) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.53, 0.83) | <0.001 | 0.71 (0.54, 0.94) | 0.015 |

DHEA was log‐transformed with base natural constant.

Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: adjusts for age and insurance type. Model 3: model 2 + BMI, duration of diabetes mellitus, SBP, DBP, DKD, HDL‐C, FBG, HbA1c, and use of metformin, α‐glucosidase inhibitors, and insulin.

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; DR, diabetic retinopathy; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL‐C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; OR, odds ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Figure 2 describes the overall dose–response association of DHEA with diabetic retinopathy in the restricted cubic spline. After adjusting for covariates, the odds of diabetic retinopathy decreased linearly with increasing DHEA concentrations (P‐overall = 0.044; P‐nonlinear = 0.364).

Figure 2.

The overall dose–response association of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) with diabetic retinopathy (DR) shown by the restricted cubic spline. The line indicated the adjusted ORs and 95% CI is shown by shaded areas. DHEA was log‐transformed with base natural constant. Adjusted for age, insurance type, BMI, duration of diabetes, SBP, DBP, DKD, HDL‐C, FBG, HbA1c, and use of metformin, α‐glucosidase inhibitors and insulin.

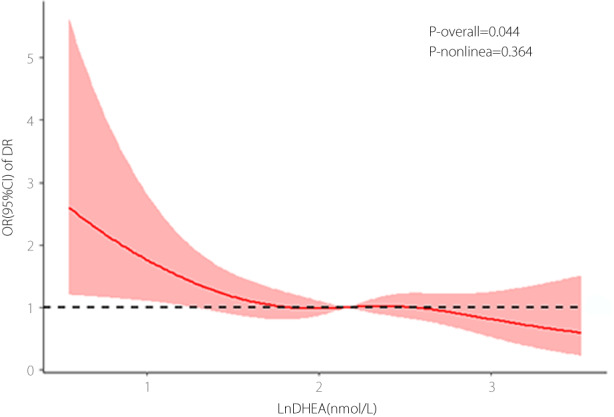

Subgroup analyses of the DHEA and DR relationship

Figure 3 illustrates the association between DHEA and diabetic retinopathy in the subgroup analyses based on age, sex, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and the HbA1c level. The effect of DHEA on diabetic retinopathy risk was stable in all subgroups, and no interactions between DHEA and the subgroup variables were statistically significant (all P for interaction >0.05).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analyses of the association of DHEA with diabetic retinopathy. DHEA was log‐transformed with base natural constant. Adjusted for age, insurance type, BMI, duration of diabetes mellitus, SBP, DBP, DKD, HDL‐C, FBG, HbA1c, and use of metformin, α‐glucosidase inhibitors and insulin.

DISCUSSION

This cross‐sectional study assessed the association of DHEA levels with diabetic retinopathy risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. To our knowledge, we are the first to report a significant association between low serum DHEA levels and DR in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients after adjusting for traditional risk factors. Moreover, the effect of DHEA on diabetic retinopathy was stable in the age, sex, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and HbA1c subgroups.

Previous studies have evaluated associations of DHEA with macrovascular and microvascular diseases. In men, a low DHEA concentration was associated with an increased incidence of macrovascular diseases. A prospective study of the general population demonstrated that a low serum DHEA level was associated with a 5 year risk of developing coronary heart disease in men aged 69–81 years 8 . The Massachusetts Male Aging Study also reported a significant association between low serum DHEA levels and the development of ischemic heart disease 22 . Moreover, low DHEA levels correlated with cardiovascular disease, including coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke, in participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus from 10 communities in Shanghai, China 9 . Similarly, our previous study identified a relationship between low DHEA levels and coronary heart disease in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus 15 . Conversely, a significant relationship was not identified between DHEA and the incidence of cardiovascular disease in studies of women in the general population or those with type 2 diabetes mellitus 9 , 15 , 23 . Sex‐specific differences regarding these associations remain unclear and require further investigation.

Previous studies have described the relationship between DHEA and microvascular disease. The population‐based Rotterdam study showed that DHEA was not related to microvascular injury in men or women, evaluated by arteriolar and venular calibers of the retina 24 . However, a study of postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus from Shanghai, China, reported that high DHEA levels were associated with diabetic kidney disease 9 . In contrast, a rat mesangial cell‐based study showed that DHEA had a protective effect against hyperglycemia‐induced lipid peroxidation and cell growth inhibition 25 . Our previous study also reported that low serum DHEA levels correlated with diabetic kidney disease in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus 10 . In addition, DHEA was shown to reverse bovine retinal capillary pericyte loss caused by glucose toxicity 12 . Similarly, the current study identified a strong negative correlation between the serum DHEA level and diabetic retinopathy in participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus. We presume that differences in the participants, outcomes, and adjusted risk factors partially explain these contrasting results.

Presently, diabetic retinopathy is considered an inflammatory neurovascular complication of diabetes mellitus and is characterized by retinal capillary occlusion, vasculature leakage, retinal ischemia and damage, angiogenesis, and neovascularization 26 . Inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy 27 , and increases in endothelial cell adhesion molecules, such as VCAM‐1 and E‐selectin, cause an accumulation of leukocytes in retinal capillaries 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 . Leukocyte‐endothelium adhesion leads to endothelial cell apoptosis and the breakdown of the blood–retinal barrier 32 , thereby causing a low‐grade inflammatory state in the retina. In addition, the upregulated inflammatory cytokine expression in the serum and ocular samples of diabetic patients, including TNF‐α, IL‐6, IL‐8, and soluble VCAM‐1, have been associated with the severity of diabetic retinopathy 33 , 34 , 35 .

Furthermore, DHEA inhibits inflammation and regulates immune responses. For example, in a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)‐induced lung inflammation model, DHEA restrained acute neutrophil recruitment by upregulating developmental endothelial locus 1 expression, which is decreased in an inflammatory state 36 . In mice with colitis, DHEA attenuates intestinal inflammatory injury through GPR30‐mediated Nrf2 activation and NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition 37 . Moreover, DHEA relieves Escherichia coli O157:H7‐induced inflammation in mice and LPS‐induced inflammation in RAW264.7 macrophages by blocking the activation of AKT, MAPK, and NF‐κB signaling pathways and increasing the activation of Nrf2, which is associated with autophagy 38 , 39 . Given that diabetic retinopathy is also an inflammatory complication of diabetes mellitus, we hypothesized that the anti‐inflammatory effects of DHEA partly explain the inverse relationship between DHEA and diabetic retinopathy.

Neurodegeneration is an important part in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy 40 . Neurodegeneration, including reactive gliosis, decreased retinal neuronal function, and neuronal apoptosis, is now regarded as an early event in the progression of diabetic retinopathy 41 , 42 . Diabetes mellitus‐induced neurodegeneration occurs before visible microangiopathy in diabetic rats and humans 43 , 44 . Moreover, DHEA has neuroprotective effects on stroke and traumatic brain and spinal injuries 45 , 46 , 47 . Furthermore, DHEA inhibits microglial inflammation by activating the TrkA‐Akt1/2‐CREB‐Jmjd3 pathway in subarachnoid hemorrhage and neuroinflammation models 48 , 49 . Additionally, DHEA prevents the apoptotic loss of neurons through its interaction with nerve growth factor 50 , and intravitreal DHEA injections reduces retinal damage caused by the excitatory amino acid, AMPA, in adult Sprague–Dawley rats 51 . Furthermore, BNN27, a novel C17‐spiroepoxide derivative of DHEA, reverses retinal injury in diabetic rats, targeting the neurodegenerative and inflammatory components of diabetic retinopathy 52 . Therefore, we speculate that the neuroprotective mechanisms of DHEA underlie the relationship between DHEA and diabetic retinopathy.

Although animal experiments have presented favorable evidence regarding the effects of DHEA on inflammation and neurodegeneration, DHEA supplementation in humans has been controversial since these studies only included a small number of participants. For instance, a daily 50 mg dose of DHEA significantly increased insulin sensitivity 53 and decreased the total cholesterol and low‐density lipoprotein levels 54 , 55 in patients with hypoadrenalism and healthy postmenopausal women. Furthermore, 50 mg of DHEA per day for 6 months improved age‐related changes in fat mass, lean mass, and bone mineral density in older women and men 56 , 57 . However, a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials indicated that DHEA administration reduced fasting plasma glucose levels but not insulin resistance 58 . In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that DHEA treatment does not affect insulin secretion 59 or lipid profiles 60 . DHEA supplementation did not affect cardiovascular parameters, arterial stiffness, or endothelial function in women with hypoadrenalism or hypopituitarism 61 , 62 . Thus, further clinical trials with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm the effect of DHEA on glucose metabolism and health.

This study had several limitations. First, the causal association of DHEA with diabetic retinopathy could not be determined because of the study's cross‐sectional design. Second, we recruited hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus; thus, these results should be confirmed before generalizing them to the general diabetic population. Third, we did not assess the association between low DHEA levels and the severity of diabetic retinopathy, especially sight‐threatening diabetic retinopathy because of the small number of patients with severe diabetic retinopathy. Finally, this study's sample size was relatively small, potentially limiting the power to test subgroup interactions.

In conclusion, low serum DHEA levels were significantly associated with diabetic retinopathy in adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in northern China, suggesting a potential role of DHEA in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Further prospective studies are necessary to confirm these results and to identify the mechanisms underlying associations between DHEA and diabetic microvascular complications.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Approval of the research protocol: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (approval number: IRB2020‐YX‐027‐01).

Informed consent: The requirement for informed consent was waived because the data were gathered from electronic medical records, and the participants’ identities were anonymized.

Approval date of registry and the registration no. of the study: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81830025 and 81900720), the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0802502), Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (18JCYBJC93900), Tianjin Municipal Health Commission (TJWJ2021ZD001), Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (TJYXZDXK‐030A), and the Tianjin Municipal Education Commission (2021KJ209).

REFERENCES

- 1. Steinmetz JD, Bourne RR, Briant PS, et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the Right to Sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health 2021; 9: e144–e160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Teo ZL, Tham YC, Yu M, et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ophthalmology 2021; 128: 1580–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Song P, Yu J, Chan KY, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and burden of diabetic retinopathy in China: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Glob Health 2018; 8: 010803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ting DSW, Cheung CY, Nguyen Q, et al. Deep learning in estimating prevalence and systemic risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: a multi‐ethnic study. NPJ Digit Med 2019; 2: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin KY, Hsih WH, Lin YB, et al. Update in the epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Investig 2021; 12: 1322–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rutkowski K, Sowa P, Rutkowska‐Talipska J, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): hypes and hopes. Drugs 2014; 74: 1195–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu D, Iruthayanathan M, Homan LL, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone stimulates endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis through extracellular signal‐regulated kinase 1/2‐mediated mechanisms. Endocrinology 2008; 149: 889–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tivesten Å, Vandenput L, Carlzon D, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate predict the 5‐year risk of coronary heart disease events in elderly men. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64: 1801–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang C, Zhang W, Wang Y, et al. Novel associations between sex hormones and diabetic vascular complications in men and postmenopausal women: a cross‐sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2019; 18: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang X, Xiao J, Li X, et al. Low serum dehydroepiandrosterone is associated with diabetic kidney disease in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Endocrinol 2022; 13: 915494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes 2005; 54: 1615–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brignardello E, Beltramo E, Molinatti PA, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone protects bovine retinal capillary pericytes against glucose toxicity. J Endocrinol 1998; 158: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Consultation, WHO Expert . Appropriate body‐mass index for asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004; 363: 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150: 604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang X, Xiao J, Liu T, et al. Low serum dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate are associated with coronary heart disease in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Endocrinol 2022; 13: 890029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diabetes branch of the Chinese Medical Association . Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes in China (2020 edition). Chin J Endocrinol Metab 2021; 37: 311–398. [Google Scholar]

- 17. The Joint Committee of Chinese Hypertension Prevention Guide . Guidelines on prevention and treatment of hypertension in China (2018 edition). Chin J Cardiovasc 2019; 24: 24–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18. The Joint Committee of Chinese Adult Dyslipidemia Prevention Guide . Guidelines on prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in Chinese adults (2016 edition). Chin J Cardiol 2016; 44: 833–853. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tuttle KR, Bakris GL, Bilous RW, et al. Diabetic kidney disease: a report from an ADA consensus conference. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2864–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL 3rd, Klein RE, et al. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 1677–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wong TY, Cheung N, Tay WT, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: the Singapore Malay eye study. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 1869–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Feldman HA, Johannes CB, Araujo AB, et al. Low dehydroepiandrosterone and ischemic heart disease in middle‐aged men: prospective results from the Massachusetts male aging study. Am J Epidemiol 2001; 153: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meun C, Franco OH, Dhana K, et al. High androgens in postmenopausal women and the risk for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease: the Rotterdam study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018; 103: 1622–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aribas E, Ahmadizar F, Mutlu U, et al. Sex steroids and markers of micro‐ and macrovascular damage among women and men from the general population. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021; 29: 1322–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brignardello E, Gallo M, Aragno M, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone prevents lipid peroxidation and cell growth inhibition induced by high glucose concentration in cultured rat mesangial cells. J Endocrinol 2000; 166: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Youngblood H, Robinson R, Sharma A, et al. Proteomic biomarkers of retinal inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 4755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Forrester JV, Kuffova L, Delibegovic M. The role of inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 583687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kasza M, Meleg J, Vardai J, et al. Plasma E‐selectin levels can play a role in the development of diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2017; 255: 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Limb GA, Hickman‐Casey J, Hollifield RD, et al. Vascular adhesion molecules in vitreous from eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999; 40: 2453–2457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang W, Lo ACY. Diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiology and treatments. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19: 1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tang J, Kern TS. Inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res 2011; 30: 343–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joussen AM, Poulaki V, Mitsiades N, et al. Suppression of Fas‐FasL‐induced endothelial cell apoptosis prevents diabetic blood‐retinal barrier breakdown in a model of streptozotocin‐induced diabetes. FASEB J 2003; 17: 76–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boss JD, Singh PK, Pandya HK, et al. Assessment of neurotrophins and inflammatory mediators in vitreous of patients with diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017; 58: 5594–5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Storti F, Pulley J, Kuner P, et al. Circulating biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial activation in diabetic retinopathy. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2021; 10: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gouliopoulos NS, Kalogeropoulos C, Lavaris A, et al. Association of serum inflammatory markers and diabetic retinopathy: a review of literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2018; 22: 7113–7128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ziogas A, Maekawa T, Wiessner JR, et al. DHEA inhibits leukocyte recruitment through regulation of the integrin antagonist DEL‐1. J Immunol 2020; 204: 1214–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cao J, Lu M, Yan W, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone alleviates intestinal inflammatory damage via GPR30‐mediated Nrf2 activation and NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition in colitis mice. Free Radic Biol Med 2021; 172: 386–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao J, Cao J, Yu L, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone resisted E. Coli O157:H7‐induced inflammation via blocking the activation of p38 MAPK and NF‐κB pathways in mice. Cytokine 2020; 127: 154955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cao J, Li Q, Shen X, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone attenuates LPS‐induced inflammatory responses via activation of Nrf2 in RAW264.7 macrophages. Mol Immunol 2021; 131: 97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simó R, Stitt AW, Gardner TW. Neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy: does it really matter? Diabetologia 2018; 61: 1902–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abcouwer SF, Gardner TW. Diabetic retinopathy: loss of neuroretinal adaptation to the diabetic metabolic environment. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014; 1311: 174–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Simó R, Hernández C. Neurodegeneration in the diabetic eye: new insights and therapeutic perspectives. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2014; 25: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barber AJ, Lieth E, Khin SA, et al. Neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes. Early onset and effect of insulin. J Clin Invest 1998; 102: 783–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lopes de Faria JM, Russ H, Costa VP. Retinal nerve fibre layer loss in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus without retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2002; 86: 725–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Arbo BD, Bennetti F, Ribeiro MF. Astrocytes as a target for neuroprotection: modulation by progesterone and dehydroepiandrosterone. Prog Neurobiol 2016; 144: 27–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Charalampopoulos I, Alexaki VI, Lazaridis I, et al. G protein‐associated, specific membrane binding sites mediate the neuroprotective effect of dehydroepiandrosterone. FASEB J 2006; 20: 577–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vahidinia Z, Karimian M, Joghataei MT. Neurosteroids and their receptors in ischemic stroke: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Res 2020; 160: 105163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tao T, Liu GJ, Shi X, et al. DHEA attenuates microglial activation via induction of JMJD3 in experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation 2019; 16: 243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alexaki VI, Fodelianaki G, Neuwirth A, et al. DHEA inhibits acute microglia‐mediated inflammation through activation of the TrkA‐Akt1/2‐CREB‐Jmjd3 pathway. Mol Psychiatry 2018; 23: 1410–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lazaridis I, Charalampopoulos I, Alexaki VI, et al. Neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone interacts with nerve growth factor (NGF) receptors, preventing neuronal apoptosis. PLoS Biol 2011; 9: e1001051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kokona D, Charalampopoulos I, Pediaditakis I, et al. The neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) protects the retina from AMPA‐induced excitotoxicity: NGF TrkA receptor involvement. Neuropharmacology 2012; 62: 2106–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ibán‐Arias R, Lisa S, Mastrodimou N, et al. The synthetic microneurotrophin BNN27 affects retinal function in rats with streptozotocin‐induced diabetes. Diabetes 2018; 67: 321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dhatariya K, Bigelow ML, Nair KS. Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone replacement on insulin sensitivity and lipids in hypoadrenal women. Diabetes 2005; 54: 765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Libè R, Barbetta L, Dall'Asta C, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation on hormonal, metabolic and behavioral status in patients with hypoadrenalism. J Endocrinol Invest 2004; 27: 736–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lasco A, Frisina N, Morabito N, et al. Metabolic effects of dehydroepiandrosterone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women. Eur J Endocrinol 2001; 145: 457–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Villareal DT, Holloszy JO, Kohrt WM. Effects of DHEA replacement on bone mineral density and body composition in elderly women and men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000; 53: 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Villareal DT, Holloszy JO. Effect of DHEA on abdominal fat and insulin action in elderly women and men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 292: 2243–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang X, Feng H, Fan D, et al. The influence of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on fasting plasma glucose, insulin levels and insulin resistance (HOMA‐IR) index: a systematic review and dose response meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med 2020; 55: 102583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Basu R, Dalla Man C, Campioni M, et al. Two years of treatment with dehydroepiandrosterone does not improve insulin secretion, insulin action, or postprandial glucose turnover in elderly men or women. Diabetes 2007; 56: 753–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Panjari M, Bell RJ, Jane F, et al. The safety of 52 weeks of oral DHEA therapy for postmenopausal women. Maturitas 2009; 63: 240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rice SP, Agarwal N, Bolusani H, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone replacement on vascular function in primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency: a randomized crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 1966–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Christiansen JJ, Andersen NH, Sørensen KE, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone substitution in female adrenal failure: no impact on endothelial function and cardiovascular parameters despite normalization of androgen status. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007; 66: 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]