Abstract

Women of color experience marked disparities in fulfillment of desired postpartum permanent contraception. While many attribute the disparity to the required Medicaid sterilization consent form and 30-day waiting period established in response to forced and coerced sterilizations, the policy does not entirely explain the disparity; racial and ethnic disparities persist even within strata of insurance type. We therefore propose framing postpartum permanent contraception as a health disparities issue that requires multi-level interventions to address. Based on the literature, we identify discrete levels of barriers to postpartum permanent contraception fulfilment at the patient-, physician-, hospital-, and policy-levels that interact and compound within and between individual levels, affecting each individual patient differently. At the patient-level, sociodemographic characteristics such as age, race and ethnicity, and parity impact desire for and fulfillment of permanent contraception. At the physician-level, implicit bias and paternalistic counseling contribute to barriers in permanent contraception fulfillment. At the hospital-level, Medicaid reimbursement, operating room availability, and religious affiliation influence fulfillment of permanent contraception. Lastly, at the policy-level, the Medicaid consent form and waiting period pose a known barrier to fulfillment of desired postpartum permanent contraception. Unpacking each of these discrete barriers and untangling their collective impact is necessary to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in permanent contraception fulfillment.

Keywords: permanent contraception, postpartum contraception, health disparities

Introduction

Permanent contraception (historically referred to as sterilization) is the most commonly used form of contraception in the United States (U.S.) [1]. Despite its popularity, approximately half of women who desire permanent contraception in the postpartum period do not ultimately undergo the procedure [2–4]. Women of color experience marked disparities in fulfillment of desired postpartum permanent contraception, with non-Hispanic Black women being about half as likely and Hispanic women being one-fifth as likely as non-Hispanic white women to receive desired permanent contraception [5]. These disparities in fulfillment of permanent contraception contribute to well-known disparities in pregnancy outcomes. Women with unfulfilled permanent contraception requests experience up to twice the rate of unintended pregnancy in the following year compared to women who did not request permanent contraception. Due to such pregnancies having short interpregnancy intervals, they are associated with worse outcomes for both mother and baby, including preeclampsia, preterm birth, and low birth weight [2–4, 6, 7]. In addition to this clinical and public health impact, disparities in permanent contraception fulfillment are also ethically problematic as women are not able to fulfill their autonomously desired reproductive choice [4]. Therefore, to improve health outcomes and promote autonomy, it is vital to recognize the racialized disparities of permanent contraception.

Racial and ethnic disparities in permanent contraception are especially pertinent to acknowledge and address given the history of coerced sterilization in the U.S. Social scientists have coined the term stratified reproduction to articulate the ways that fertility of people of color and those of low socioeconomic status is devalued compared to the fertility of affluent, white individuals [8]. In the 1960s and 70s, as permanent contraception uptake increased dramatically due to the legalization of contraception, there were numerous incidences of coerced sterilization of poor women and women of color [9]. It is due to this troubling history that we use the recommended terminology of permanent contraception rather than sterilization when discussing care that is autonomously-desired [10]. In response to these incidences, the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare developed a required, standardized consent form and waiting period for publicly funded permanent contraception in 1976. This policy was updated in 1978, extending the waiting period from 72 hours to 30 days from the time of written informed consent. It has not been updated since. We use the terminology of sterilization when referring to the Medicaid policy given the verbiage in the federal policy and Medicaid consent form.

While health care practices, regulations, and insurance infrastructures have evolved since the inception of the Medicaid sterilization consent form and process, the form and process themselves have not changed. In contemporary clinical practice, the federal Medicaid policy is often viewed as the primary cause of racial and ethnic disparities in permanent contraception fulfillment. Many studies have demonstrated that women with Medicaid are less likely to undergo their desired postpartum permanent contraception procedure than women with private insurance [11–16]. Women of color are more likely to have Medicaid and are therefore more likely to face barriers due to the Medicaid consent process [17]. While the Medicaid sterilization consent form and process remain an undeniable and discrete barrier to autonomously desired care, it does not entirely explain the racial disparity in permanent contraception fulfillment, as racial and ethnic disparities persist even within strata of insurance type. Black and Hispanic women with Medicaid are less likely to undergo their desired postpartum permanent contraception procedure than white women with Medicaid [5]. Additionally, one study found that Medicaid was not negatively associated with permanent contraception fulfillment after controlling for known factors that impact contraceptive choice and fulfillment such as race, ethnicity, and adequacy of prenatal care, indicating that insurance type may instead be a proxy for other factors and barriers that impact choice in contraceptive method and provision of the desired method.

Multiple barriers to achieving equitable postpartum permanent contraception exist. The simple solution of advocating for complete removal of the required Medicaid form and waiting period ignores the troubling history of coercion. Importantly, given ongoing coercive permanent contraceptive practices, structural racism, and implicit bias, eliminating the Medicaid policy entirely also removes protection for a vulnerable population [4, 18–21]. Furthermore, removal of this barrier alone would do little to alleviate other identified barriers to obtaining desired postpartum permanent contraception at the patient-, physician-, and hospital-levels [22–24]. A better understanding of the impact of this layering of barriers both individually and collectively is therefore necessary to address the disparities surrounding postpartum permanent contraception in a manner that is both evidence-based and patient-centered.

Health Disparities Framework

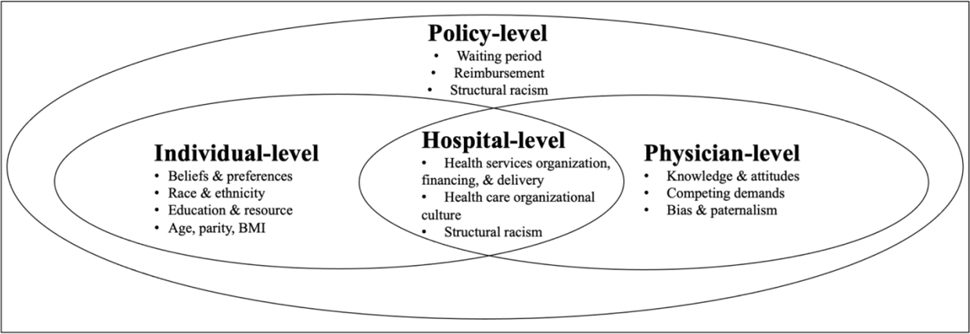

We therefore propose adapting the health disparities framework developed by Kilbourne et al. to frame fulfillment of desired postpartum permanent contraception as a health disparities issue that requires multi-level interventions to address – rather than solely a Medicaid policy issue (Figure 1) [25]. Based on a critically appraised topic review of the literature, we have identified discrete levels of barriers to equitable postpartum permanent contraception layered at the patient-, physician-, hospital-, and policy-levels.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Barriers to Postpartum Permanent Contraception (Adapted from Kilbourne 2006)

Patient-level

A variety of patient-level factors, including age, race and ethnicity, BMI, mode of delivery, and others, are associated with both desire for and fulfillment of postpartum permanent contraception. However, it is unclear whether these differences are due to variation in patient’s autonomous choices – which should be respected and fulfilled – or disparities due to external factors. For example, women who deliver vaginally are less likely to undergo a permanent contraception procedure in the inpatient postpartum period than those who deliver via cesarean section, likely due to the ease of performing the concomitant permanent contraception procedure during cesarean delivery. It remains unknown whether this is because some patients autonomously choose to forgo the inpatient surgery after a vaginal delivery, or due to an external barrier to care. For example, this could be due to a physician-level factor such as lack of physician availability, a hospital-level factor such as lack of operating room availability or lack of adequate hospital reimbursement, or a policy-level barrier such as lack of a valid signed Medicaid sterilization consent form.

Physician-level

Physician-level factors, such as implicit bias and paternalistic counseling, contribute to barriers in permanent contraception fulfillment. Gendered and racialized tropes regarding fertility and pregnancy directly impact counseling and provision of permanent contraception [26]. Racial biases influence clinical decision-making, compromise autonomy and informed consent and in turn, directly affect health outcomes [21, 27]. For permanent contraception, implicit bias and coercive contraceptive practices occur in two forms: patients with certain demographics are counseled toward permanent contraception, whereas patients with other demographics are counseled away from permanent contraception. Multiple studies have demonstrated that contraceptive counseling varies depending on patient race and ethnicity [18, 19]. Women of color also experience negative contraceptive counseling, with undertones of discrimination and coercion and a greater likelihood of being advised to limit their childbearing [48, 50, 51]. Further research is needed to understand the extent to which physician-level barriers like bias contribute to disparities in permanent contraception.

Hospital-level

Hospital-level barriers also directly influence permanent contraception fulfillment. Lack of available operating room and lack of time to complete the permanent contraception procedure have both been associated with decreased fulfillment of permanent contraception [12, 15]. Some hospitals have created additional administrative hurdles for patients desiring permanent contraception due to the threat of reimbursement difficulties if the Medicaid sterilization consent form has not been properly completed [29]. Little transparency and convoluted instructions from state Medicaid offices make this process more difficult for both physicians and hospitals [30]. Additionally, religiously affiliated hospitals may deny permanent contraception to certain or all women [31]. This may be especially challenging for those who cannot obtain in-network insurance coverage at other institutions [32]. Importantly, existing studies evaluating the impact of hospital-level factors on fulfillment of desired permanent contraception have been conducted at single institutions and therefore do not capture variation in hospital-level barriers. Therefore, to more fully understand how hospital-level factors and policies impact permanent contraception, multi-site research within and between states is needed.

Policy-level

At the policy-level, the Medicaid consent form and waiting period pose a known barrier to fulfillment of desired postpartum permanent contraception and contribute to health disparities. Of note, variation in Medicaid sterilization policies has been noted both between individual states and within the same state [23]. The Medicaid consent process interacts with patient-, physician-, and hospital-level factors, thus making attribution of specific factors and barriers to the overall disparity difficult. Though some have advocated for the abolishment of the Medicaid consent process altogether, it is imperative to keep in mind the historical and ongoing contemporary context for the policy. Due to the many interactions with barriers at different levels, eliminating the Medicaid policy altogether would not eliminate the racial and ethnic disparities. Instead, future research is needed to fully understand how the Medicaid policy interacts with patient-, physician-, and hospital-level factors.

Additionally, it is imperative that any changes in the Medicaid sterilization policy be aligned with the goals of the populations impacted by the current provisions and any revisions. One qualitative study noted that patients with Medicaid insurance do not want the Medicaid waiting period removed altogether given continued coercion in contemporary medical practice [33]. While ongoing reports of coercion continue despite the Medicaid policy, it is important to remember that the viewpoints of the communities most impacted must be honored. Therefore, revision to the Medicaid policy must be informed by this goal of ensuring equity in fulfillment of desired permanent contraception while being mindful of the goals and desires of the patients and communities impacted by any such policy revision.

Conclusion

Thus, there are well-documented racial and ethnic disparities in fulfillment of desired postpartum permanent contraception. Barriers at multiple levels – including patient-, physician-, hospital-, and policy – all contribute to these disparities. While it is necessary to understand these individual level factors and barriers impacting permanent contraception, they do not act alone. Rather, the various barriers interact and compound within and between levels. That is, a patient’s demographics, such as age, race, ethnicity, and clinical characteristics like BMI, are not intrinsically barriers to permanent contraception in isolation. Rather, survey based- studies have found that these patient-level characteristics influence a physician’s willingness to perform the permanent contraception procedure, thereby preventing permanent contraception fulfillment [24, 34–36]. Thus, patient-level characteristics are made to become barriers when they interact with physician-, hospital-, and policy-level factors. As a second example, hospital-level barriers, such as reimbursement and hospital culture, impact permanent contraception fulfillment through interactions with barriers at the patient-, physician-, and policy-levels. That is, if hospital culture or practice is to limit operating room availability or impose cut-offs for postpartum permanent contraception based on BMI, this influences the manner in which physicians interact with and counsel their patients.

Therefore, barriers across layers of this proposed framework interact with one another, compounding differently to impact individuals to varying extents [36–43]. To understand the mechanisms by which barriers impact permanent contraception fulfillment, it is necessary to examine all layers of barriers together within a health disparities framework. Unpacking each of these discrete barriers and untangling their collective impact is necessary to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in permanent contraception fulfillment. In doing so, we can ensure women are able to make fully autonomous decisions about their bodies and their childbearing.

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge Kristen Berg, PhD; Emily Miller, MD; Kari White, PhD; Tania Serna, MD; Margaret Boozer, MD; Jennifer Bailit, MD; and Douglas Gunzler, PhD.

Funding:

Brooke Bullington received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (T32HD52468, PI Julie Daniels and Andrew Olshan) and an infrastructure grant for population research to the Carolina Population Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (P2CHD050924, PI Elizabeth Frankenberg). Dr. Arora is funded by 1R01HD098127 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) branch of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable

Consent to participate: Not applicable

Consent for publication: Not applicable

Code availability: Not applicable

Availability of data and material:

Not applicable

References

- [1].Daniels K, Abma JC. Current Contraceptive Status Among Women Aged 15–49: United States, 2015–2017. NCHS Data Brief; 327, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db327_tables-508.pdf#3. (2018, accessed 1 November 2021). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Access to Postpartum Sterilization: ACOG Committee Opinion Summary, Number 827. Obstet Gynecol 2021; 137: 1146–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Block-Abraham D, Arora KS, Tate D, et al. Medicaid Consent to Sterilization Forms: Historical, Practical, Ethical, and Advocacy Considerations. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2015; 58: 409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Borrero S, Zite N, Potter JE, et al. Medicaid Policy on Sterilization — Anachronistic or Still Relevant? http://dx.doi.org/101056/NEJMp1313325 2014; 370: 102–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].White K, Potter JE. Reconsidering racial/ethnic differences in sterilization in the United States. Contraception 2014; 89: 550–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Thurman AR, Janecek T. One-year follow-up of women with unfulfilled postpartum sterilization requests. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 116: 1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cleland J, Conde-Agudelo A, Peterson H, et al. Contraception and health. Lancet (London, England) 2012; 380: 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Harris L, Wolfe T . Stratified reproduction, family planning care and the double edge of history. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2014; 26: 539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Borrero S, Zite N, Potter J, et al. Medicaid policy on sterilization--anachronistic or still relevant? N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 102–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jensen JT. Permanent contraception: modern approaches justify a new name. Contraception 2014; 89: 493–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zite N, Wuellner S, Gilliam M. Failure to obtain desired postpartum sterilization: Risk and predictors. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 105: 794–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zite N, Wuellner S, Gilliam M. Barriers to obtaining a desired postpartum tubal sterilization. Contraception 2006; 73: 404–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Boardman L, DeSimone M, Allen R. Barriers to Completion of Desired Postpartum Sterilization. Rhode Island Medical Journal, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23641425/ (2013, accessed 5 October 2021). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wolfe KK, Wilson MD, Hou MY, et al. An updated assessment of postpartum sterilization fulfillment after vaginal delivery. Epub ahead of print 2017. DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Morris J, Ascha M, Wilkinson B, et al. Desired Sterilization Procedure at the Time of Cesarean Delivery According to Insurance Status. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 134: 1171–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hahn TA, McKenzie F, Hoffman SM, et al. A Prospective Study on the Effects of Medicaid Regulation and Other Barriers to Obtaining Postpartum Sterilization. J Midwifery Womens Health 2019; 64: 186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Keisler-Starkey K, Bunch LN. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2019 Current Population Reports. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Downing RA, LaVeist TA, Bullock HE. Intersections of Ethnicity and Social Class in Provider Advice Regarding Reproductive Health. Am J Public Health 2007; 97: 1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dehlendorf C, Ruskin R, Grumbach K, et al. Recommendations for intrauterine contraception: a randomized trial of the effects of patients’ race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 203: 319.e1–319.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gomez A, Wapman M. Under (implicit) pressure: young Black and Latina women’s perceptions of contraceptive care. Contraception 2017; 96: 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kathawa CA, Arora KS. Implicit Bias in Counseling for Permanent Contraception: Historical Context and Recommendations for Counseling. https://home.liebertpub.com/heq 2020; 4: 326–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Arora K, Wilkinson B, Verbus E, et al. Medicaid and fulfillment of desired postpartum sterilization. Contraception 2018; 97: 559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Arora K, Castleberry N, Schulkin J. Variation in waiting period for Medicaid postpartum sterilizations: results of a national survey of obstetricians-gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018; 218: 140–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Arora KS, Castleberry N, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists’ counseling regarding postpartum sterilization. Int J Womens Health 2018; 10: 425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, et al. Advancing Health Disparities Research Within the Health Care System: A Conceptual Framework. Am J Public Health 2006; 96: 2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Harris L Interdisciplinary perspectives on race, ethnicity, and class in recommendations for intrauterine contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 203: 293–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Goulding A, Bauer A, Muddana A, et al. Provider Counseling and Women’s Family Planning Decisions in the Postpartum Period. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2020; 29: 847–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yee L, Simon M. Perceptions of coercion, discrimination and other negative experiences in postpartum contraceptive counseling for low-income minority women. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2011; 22: 1387–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Arora K, Ponsaran R, Morello L, et al. Attitudes and beliefs of obstetricians-gynecologists regarding Medicaid postpartum sterilization - A qualitative study. Contraception 2020; 102: 376–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bouma-Johnston H, Ponsaran R, Arora K. Variation by state in Medicaid sterilization policies for physician reimbursement. Contraception 2021; 103: 255–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Henkel A, Beshar I, Goldthwaite L. Postpartum permanent contraception: Updates on policy and access. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schueler K, Hebert L, Wingo E, et al. Denial of tubal ligation in religious hospitals: Consumer attitudes when insurance limits hospital choice. Contraception 2021; 104: 194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Batra P, Rodriguez K, Cheney AM. Using Deliberative and Qualitative Methods to Recommend Revisions to the Medicaid Sterilization Waiting Period. Womens Health Issues 2020; 30: 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Harrison D, Cooke C. An elucidation of factors influencing physician willingness to perform elective female sterilization. Obstet Gynecol 1988; 72: 565–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, Yoon JD, et al. Factors influencing physicians’ advice about female sterilization in USA: a national survey. Hum Reprod 2011; 26: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Williams A, Kajiwara K, Soon R, et al. Recommendations for Contraception: Examining the Role of Patients’ Age and Race. 77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].White K, Potter J, Hopkins K, et al. Variation in postpartum contraceptive method use: results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). Contraception 2014; 89: 57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Starr K, Martins S, Watson S, et al. Postpartum Contraception Use by Urban/Rural Status: An Analysis of the Michigan Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Data. Womens Health Issues 2015; 25: 622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Callegari L, Zhao X, Schwarz E, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in contraceptive preferences, beliefs, and self-efficacy among women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017; 216: 12–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Jackson A, Karasek D, Dehlendorf C, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in women’s preferences for features of contraceptive methods. Contraception 2016; 93: 406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kramer R, Higgins J, Godecker A, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patterns of long-acting reversible contraceptive use in the United States, 2011–2015. Contraception 2018; 97: 399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Madden T, Secura GM, Nease R, et al. The Role of Contraceptive Attributes in Women’s Contraceptive Decision Making HHS Public Access. Am J Obs Gynecol 2015; 213: 46–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Iseyemi A, Zhao Q, McNicholas C, et al. Socioeconomic Status As a Risk Factor for Unintended Pregnancy in the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Obstet Gynecol 2017; 130: 609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable