ABSTRACT

Moral injury is an emerging concept that captures the psychosocial consequences of involvement in and exposure to morally transgressive events. In the past decade, research on moral injury has grown exponentially. In this special collection we review papers on moral injury published in the European Journal of Psychotraumatology from its inception until December 2022, that have a primary focus on moral injury as evidenced by the words ‘moral injury’ in the title or abstract. We included 19 papers on quantitative (n = 9) and qualitative (n = 5) studies of different populations including (former) military personnel (n = 9), healthcare workers (n = 4) and refugees (n = 2). Most papers (n = 15) focused on the occurrence of potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs), moral injury and associated factors, while four papers primarily concerned treatment. Together, the papers offer a fascinating overview of aspects of moral injury in different populations. Research is clearly widening from military personnel to other populations such as healthcare workers and refugees. Focal points included the impact of PMIEs involving children, the association of PMIEs and personal childhood victimisation, the prevalence of betrayal trauma, and the relationship between moral injury and empathy. As for treatment, points of interest included new treatment initiatives as well as findings that PMIE exposure does not impede help-seeking behaviour and response to PTSD treatment. We further discuss the wide range of phenomena that fall under moral injury definitions, the limited diversity of the moral injury literature, and the clinical utility of the moral injury construct. From conceptualisation to clinical utility and treatment, the concept of moral injury matures. Whether or not moral injury becomes a formal diagnosis, the need to examine tailored interventions to alleviate moral injury is clear.

KEYWORDS: Moral injury, trauma, PTSD, shame, guilt, empathy, PMIE

HIGHLIGHTS

Moral injury is increasingly studied outside military populations, such as in healthcare workers and refugees.

Among the most impactful potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs) are those involving children, but betrayal trauma may be the most prevalent type of PMIE.

There is a need for tailored, evidence-based interventions to alleviate moral injury.

Abstract

El daño moral es un concepto emergente que captura las consecuencias psicosociales de la participación y exposición a eventos moralmente transgresores. En la última década, la investigación en el daño moral ha crecido de manera exponencial. En esta colección especial revisamos artículos acerca de daño moral publicado en la Revista Europea desde sus inicios hasta diciembre del 2022, que tienen su foco principal en el daño moral, como se evidencia en las palabras 'daño moral' en el título o resumen. Incluimos 19 artículos de estudios cuantitativos (n = 9) y cualitativos (n = 5) de diferentes poblaciones, incluyendo ex personal militar (n = 9), trabajadores de la salud (n = 4) y refugiados (n = 2). La mayoría de los artículos (n = 15) se centraron en la ocurrencia de experiencias potencialmente dañinas moralmente (PMIE), daño moral y factores asociados, mientras que cuatro documentos se referían principalmente al tratamiento. En conjunto, los documentos ofrecen una fascinante visión general de aspectos del daño moral en diferentes poblaciones. Las investigaciones claramente se están ampliando desde el personal militar hasta otras poblaciones, como trabajadores de la salud y refugiados. Los puntos centrales incluyen el impacto de los PMIE que involucran a niños, la asociación de los PMIE y la victimización personal en la infancia, la prevalencia del trauma de traición y la relación entre daño moral y empatía. En cuanto al tratamiento, los puntos de interés incluyeron nuevas iniciativas de tratamiento, así como hallazgos de que la exposición a PMIE no impide el comportamiento de búsqueda de ayuda y la respuesta al tratamiento del TEPT. Discutimos más a fondo la amplia gama de fenómenos que caen bajo las definiciones de daño moral, la limitada diversidad de la literatura acerca de daño moral y la utilidad clínica del constructo daño moral. De la conceptualización a la utilidad clínica y al tratamiento, madura el concepto de daño moral. Ya sea que el daño moral se convierta o no en un diagnóstico formal, la necesidad de examinar intervenciones adaptadas para aliviar el daño moral es clara.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Daño moral, trauma, TEPT, vergüenza, culpa, empatía, PMIE

Abstract

摘要:道德伤害是一个新兴概念,捕捉了参与和暴露于违背道德事件的社会心理后果。 在过去十年中,对道德伤害的研究呈指数级增长。在这个特别的集合中,我们回顾了欧洲心理创伤学杂志从创刊到 2022 年 12 月发表的关于道德伤害的论文,可由标题或摘要中包含“道德伤害”一词证明这些论文主要关注道德伤害。 我们纳入了 19 篇关于不同人群的定量(n = 9)和定性(n = 5)研究的论文,包括(前)军人(n = 9)、医护人员(n = 4)和难民(n = 2)。 大多数论文 (n = 15) 关注潜在道德伤害经历 (PMIE)、道德伤害和相关因素的发生,而四篇论文主要关注治疗。 总之,这些论文对不同人群的道德伤害的各个方面进行了引人入胜的概述。 研究显然正在从军人扩大到其他人群,如医护人员和难民。关注点包括涉及儿童的 PMIE 的影响、PMIE 与个人童年受害的关联、背叛创伤的普遍存在以及道德伤害与共情之间的关系。 至于治疗,关注点包括新的治疗举措以及 PMIE 暴露不会妨碍求助行为和对 PTSD 治疗反应的发现。 我们进一步讨论了属于道德伤害定义、道德伤害文献有限多样性以及道德伤害结构临床效用的广泛现象。 从概念化到临床应用和治疗,道德伤害的概念日趋成熟。 无论道德伤害是否成为一个正式诊断,考查减轻道德伤害的个性化干预措施的需求都是显而易见的。

关键词: 羞耻, 内疚, 创伤后应激障碍(PTSD), 创伤, 自我

In recent years, increasing attention is given to psychosocial suffering associated with transgressions of important moral beliefs and expectations, also known as moral injury (Litz et al., 2009). Instances of such transgressions and their emotional consequences abound. Even though civilian deaths may be perceived as collateral damage by military commanders, military veterans themselves may feel deep guilt over killing innocent civilians. Due to limited resources, rescue teams and healthcare personnel may experience moral dilemmas over whom to save after natural disasters, and upon looking back may feel troubled knowing they were unable to help all those in need. First responders experience increasing violence while doing their job, and some may feel betrayed by colleagues and superiors who failed to show support. Increasingly, the aftermath of such experiences – including persistent feelings of guilt, shame and anger, negative beliefs about self and others, social withdrawal, PTSD symptoms, and self-undermining behaviour – may be focus of clinical intervention.

While moral injury is a relatively new clinical concept in the psychotrauma field, the clinical observations underlying it are not new. The psychological sequelae of exposure to war have long been known to include enduring and impairing negative moral emotions such as guilt, shame and rage. In 1949, after visiting a displaced persons’ camp that housed concentration camp survivors, Friedman reported: “The sense of guilt at having remained alive when so many others had died – so universal among the survivors – seems to have played a not unimportant role in the genesis of the symptoms” (p. 603). A decade or two later, the issue of guilt emerged again in Vietnam veterans after their involvement in what they felt was an unjust war. Scholars such as Lifton (1973) and Kubany (1994) published influential works on combat-related guilt in military veterans. In 1994 the concept of moral injury was coined by Shay, who stressed the psychological suffering that resulted from moral transgressions in war:

I’ve come to strongly believe through my work with Vietnam veterans (…) that moral injury is an essential part of any combat trauma that leads to lifelong psychological injury. Veterans can usually recover from horror, fear, and grief once they return to civilian life, so long as “what’s right” has not also been violated. (p. 20).

Although the first conceptualisation of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) was based on the symptomatology of Vietnam veterans, trauma-related guilt and related negative moral emotions and cognitions experienced by many veterans were originally not included as symptoms of PTSD. Instead, PTSD was conceptualised as an anxiety disorder focusing on the experience of fear (DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1980). It took another 33 years and four editions of the DSM for moral symptoms such as persistent cognitions of blame and persistent feelings of guilt or shame to be officially acknowledged as part of the syndrome of posttraumatic stress (DSM-5; APA, 2013).

In the run-up to DSM-5, Litz et al. (2009) published a seminal paper on moral injury and moral repair in war veterans, proposing the following definition that is still central to the field:

(…) the lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioral, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations, that is, moral injury. (p. 697)

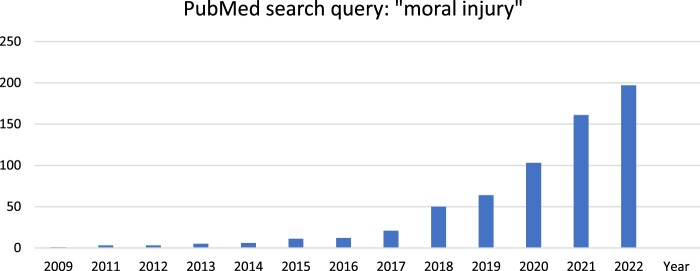

Since then, the concept of moral injury has really caught on and research on moral injury has grown exponentially (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of publications on moral injury in PubMed, 2009–2022.

The European Journal of Psychotraumatology has been publishing papers on moral injury since 2019. In this special collection we review these papers which cover a range of research populations and study types.

1. This collection

For this special collection, we included papers that were published in the European Journal of Psychotraumatology until December 2022, and that have a primary focus on moral injury as evidenced by the words ‘moral injury’ in the title and/or abstract. One paper was excluded because it concerned an editorial (O'Donnell & Greene, 2021).

The collection exists of 19 papers published in the years 2019–2022 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Papers on moral injury in the European Journal of Psychotraumatology 2019–2022.

| Author | Year | Study type | Country | Population | N (% men) | MI assessment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Military Personnel | |||||||

| Williamson | 2019 | qualitative | UK | military personnel | 6 (100) | Interviews | PMIE exposure was reported related to veterans’ own actions or to those of others, and consistently led to psychological distress |

| Williamson | 2020 | qualitative | UK | military personnel | 30 (100) | Interviews | events experienced by UK veterans can simultaneously be morally injurious and traumatic or life-threatening |

| Denov | 2022 | other | Canada | military personnel | n.a. | n.a. | Military personnel who encounter child soldiers during a military deployment may be at risk for MI |

| Hertz | 2022 | other | Israel | military personnel | 615 (100) | MIES | Vignettes of killing an innocent led to more shame and guilt than vignettes of killing a person carrying a bomb |

| Battaglia | 2019 | quantitative | Canada | military personnel | 33 (87.9) | MIES | A significant relation between childhood emotional abuse and the presence of MI in adulthood |

| Levi-Belz | 2020 | quantitative | Israel | military personnel | 191 (85.4) | MIES | Strong bridge associations between the PTSD nodes and most of the PMIES nodes |

| Healthcare Workers | |||||||

| Berkhout | 2022 | qualitative | Canada, UK | healthcare workers | 21 (23.8) | Interviews | MI underpins sources of healthcare worker distress |

| Hegarty | 2022 | qualitative | UK | healthcare workers | 30 (33.3) | Interviews | HCWs experienced a range of mental health symptoms primarily related to perceptions of institutional betrayal and feeling unable to fulfil their duty of care |

| Maftei | 2021 | quantitative | Romania | healthcare workers | 115 (24.6) | MIES* | Almost 50% of the participants reported high levels of PMIE exposure |

| Zerach | 2021 | quantitative | Israel | healthcare workers | 296 (22.4) | MIES* | Three subgroups: high exposure, betrayal-only, minimal exposure. The first two classes were associated with perceived stress and symptom severity |

| Refugees | |||||||

| Hoffman | 2019 | quantitative | Australia | refugees | 221 (46.2) | MIAS | A three-profile solution: MI-Other, MI-Other + Self, no-MI. MI profiles were associated with trauma experience, living difficulties and greater psychopathology |

| Passardi | 2022 | qualitative | Australia | refugees | 13 (30.8) | Interviews | In my country they torture your body but in Australia they kill your mind |

| Other | |||||||

| Fani | 2021 | quantitative | USA | civilians | 81 (8.4) | MIES* | Greater exposure and distress related to PMIEs were associated with higher trauma exposure as well as post-traumatic and depressive psychopathology |

| Williamson | 2022 | quantitative | UK | veterinary professionals | 90 (22.3) | MIES* | Exposure to PMIEs was reported by almost all veterinary professionals and was significantly associated with symptoms of PTSD |

| Ter Heide | 2020 | other | Netherlands | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Factors involved in the perception-action model of empathy may help explain the development of moral injury |

| Treatment | |||||||

| Nazarov | 2020 | quantitative | Canada | military personnel | 4854 (89.2) | CES | Deployed members exposed to PMIEs were more likely to seek help from their family doctor, paraprofessionals, non-professionals, and the civilian health care system |

| Held | 2021 | quantitative | USA | military personnel | 161 (91.3) | MIES | PMIE exposure and the type of index trauma did not predict changes in symptom outcomes |

| De la Rie | 2021 | case study | Netherlands | refugees | 1 (100) | MIAS | BEP-MT is a promising treatment protocol for patients suffering from PTSD after moral trauma |

| Williamson | 2022 | other | UK | military personnel | n.a. | n.a. | An intervention for MI-related mental health difficulties in UK military veterans will be developed |

Note: MI: moral injury; MIES: Moral Injury Events Scale; MIES*: adapted version of the Moral Injury Events Scale; MIAS: Moral Injury Appraisals Scale; BEP-MT: Brief Eclectic Psychotheray for Moral Trauma; HCW: healthcare worker; PMIE: potentially morally injurious event; PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; CES: Combat Experiences Scale.

The number of papers on moral injury published in EJPT has grown each year, from three papers in 2019, four in 2020 and five in 2021, to seven in 2022. The majority of papers concerned quantitative studies (n = 9), followed by qualitative studies (n = 5) and other types of studies or papers. Papers originated from seven, predominantly western, countries. Most papers focused on (former) military personnel (n = 9), followed by healthcare workers (n = 4) and refugees (n = 2). Participants in the studies of military personnel were predominantly male, participants in studies of other populations were predominantly female. Last, the vast majority (n = 15) of papers focused on the occurrence of potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs), moral injury and associated factors, while four papers primarily concerned treatment. In our review, we arranged the papers based on study populations and treatment studies.

2. The papers

Together, the papers offer a fascinating overview of aspects of moral injury in different populations (military, healthcare, refugees, and other) as well as of emerging treatment approaches.

2.1. Military personnel

The majority of papers dealt with moral injury in military personnel: military veterans or active service members. Williamson and colleagues conducted two qualitative studies of moral injury in UK military veterans. The first study (Williamson et al., 2019) was conducted with veterans and clinicians, and explored the moral injury concept, moral injurious experiences, and experiences of treating veterans with moral injury. Participants reported frequent transgressive actions by self and others, including killing children and inability to prevent the harming of civilians, which led to significant psychological distress. Treatment was conducted using a variety of techniques including responsibility pie charts, compassion-focused therapy and imagery re-scripting. In a follow-up paper (Williamson et al., 2020), the authors explored differences in response to morally injurious versus traumatic events in UK military veterans. Moral dissonance was reported to be central to the distress of those exposed to PMIEs, contributing to profound shame, disgust and guilt, as well as poor self-care and risk-taking. However, posttraumatic growth was also reported in this subgroup, especially with regards to spirituality.

Both papers by Williamson et al. mentioned the victimisation of children as a special cause of moral injury. In a review article, Denov (2022) focused on the impact of encountering children and child soldiers during military deployment. Active transgressions against children and a failure to protect children are perceived as the ultimate violation of moral beliefs about protecting innocent, vulnerable and helpless individuals. Such events may have a profound psychological impact – including shock, trauma, paralysis, and feelings of betrayal.

Indeed, this hypothesis was tested in a lab study by Hertz et al. (2022). Using case vignettes of killing a minor versus an adult, and killing an innocent suspect versus a non-innocent suspect, they tested which condition elicited the most intense shame, guilt and anger. However, while imagining killing an innocent suspect elicited greater guilt and shame than imagining killing a non-innocent suspect, contrary to the hypothesis imagining killing a minor versus an adult elicited similar degrees of shame and guilt.

Interestingly, personal experiences of childhood victimisation may influence guilt and shame after PMIEs. Battaglia et al. (2019) investigated the potential relationship between adverse childhood experiences and later onset moral injury in Canadian treatment-seeking military members. The authors identified an association between self-reported childhood emotional abuse and moral injury, suggesting that negative beliefs about oneself, others and the world, developed after adverse childhood experiences, may serve as a risk factor. In addition, they noted that betrayal was the only type of moral injury significantly associated with PTSD symptom clusters.

These findings were echoed in a study by Levi-Belz et al. (2020), who applied a network analysis model to a dataset of PMIEs, PTSD, depression, and combat exposure among Israel Defense Forces veterans. They noted that betrayal-based experiences were related to PTSD symptoms clusters directly and through depressive symptoms. Comparable to the Battaglia study, the strongest link was found between betrayal and negative changes in cognitions and mood.

2.2. Healthcare workers

The corona pandemic meant a fanning out of the moral injury concept from military personnel to healthcare workers. Where ‘moral distress’ was previously the dominant term to indicate the moral burdening of healthcare workers, this now shifted to the more loaded ‘moral injury’.

Two papers appeared that looked at the lived experience of healthcare workers during the pandemic. Berkhout et al. (2022) conducted an interview study focusing on sources and mechanisms of healthcare worker distress in Canada and the UK. Moral injury was suggested to be a mechanism, defined as the moral distress resulting from an inability to act in accordance with professional values or from the experience of betrayal in the workplace. Seeing work as meaningful was suggested to counterbalance such distress. An interview study by Hegarty et al. (2022) focused on the experience of and psychological response to cumulative PMIE exposure in frontline healthcare workers. Workers reported feeling betrayed by their superiors as well as feeling they themselves led their patients down. Moral strategies were employed to prevent or cope with moral distress, including breaking the rules, using dark humour, and learning from PMIEs to prevent repetition.

Two quantitative studies also focused on PMIE exposure during the pandemic. Maftei and Holman (2021) studied the prevalence of PMIE exposure of Romanian physicians during the pandemic. In line with the qualitative findings, betrayal was the most frequently reported PMIE. PMIE exposure was related to a simple measure of negative physical and emotional consequences. In Israel, Zerach and Levi-Belz (2021) conducted a latent class analysis of PMIE exposure in health and social care workers. They found three classes characterised by high exposure, betrayal only, and minimal exposure, respectively. The first two classes were associated with higher perceived stress, higher self-criticism, and higher symptom severity of depression, anxiety, PTSD and moral injury, as well as with lower self-compassion.

2.3. Refugees

A population among whom moral injury studies are still limited, is refugees. In one of the first studies of moral injury among refugees, Hoffman et al. (2019) conducted a latent profile analysis of moral injury appraisals. They found three profiles: transgressions by others, transgressions by others and self, and no transgressions. The first two profiles were associated with different traumatic and resettlement stressors, and with greater psychopathology. Focusing on lived experience, Passardi et al. (2022) conducted a qualitative study of refugees residing in Australia who had been detained on Nauru. Participants described how they expected to find safety in Australia, but instead experienced deprivation, powerlessness, violence and dehumanisation, leading to a feeling of being irreparably damaged. Experiences were viewed through a moral injury lens and interpreted as violation of moral expectations, betrayal, and consequent moral injury.

2.4. Other

The previous studies were all conducted in populations exposed to war or profession-related trauma. Two other studies focused on populations not commonly included in moral injury research: trauma-exposed civilians and veterinary professionals. Fani et al. (2021) conducted an initial evaluation of the MIESS-C, an adapted version of the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES; Nash et al., 2013) in civilians who participated in the Grady Trauma Project. The adapted items were found to be clear. MIESS-C exposure and distress were related with childhood abuse as well as current PTSD and depression symptom severity. Interestingly, individuals with a prior suicide attempt had higher MIESS-C exposure and distress scores.

An elevated risk of suicide was a reason to conduct a study of moral injury in veterinary professionals, who are involved in sometimes unnecessary or harmful procedures with animals. Williamson, Murphy, and Greenberg (2022) conducted an online study using an adapted version of the MIES (Nash et al., 2013). The majority of participants endorsed one or more items on the MIES, predominantly PMIEs committed by others and betrayal, with PMIE exposure being related to higher PTSD symptom severity.

A last paper (Ter Heide, 2020) presented a model of the development of moral injury based on the perception-action model of empathy (De Waal & Preston, 2017). Based on this model it is hypothesised that individuals who are most at risk of developing moral injury are those who have a high exposure to a victim’s expressions of distress, feel personally connected to the victim, experience great desire to help the victim, and are prevented from or fail in helpful or respectful behaviour. Confirmation of this hypothesis may be found in several papers in this special collection, such as the finding that veterans’ own experiences of childhood maltreatment is related to higher moral injury severity scores after PMIE exposure (Battaglia et al., 2019).

2.5. Treatment

Many of the papers described above included recommendations for treatment, such as initiating reflective practice groups for healthcare workers exposed to PMIEs (Hegarty et al., 2022), tailoring profession-related moral injury treatment to the specific PMIE that underlies it (Hertz et al., 2022), and the need to address cognitive distortions regarding responsibility in refugees (Hoffman et al., 2019). Four papers in this special collection focused predominantly on treatment, addressing common assumptions on treatment seeking and efficacy, and inspiring future treatment recommendations.

Nazarov et al. (2020) conducted a study among deployed Canadian Armed Forces personnel that focused on the assumption that service members exposed to PMIEs may be reluctant to seek help. Contrary to that assumption, those who had been exposed to PMIEs were more likely to seek help for mental health problems, especially from general practitioners, religious advisers and non-professionals. The authors stress the need for increasing awareness of moral injury among those groups as well as for transparency about confidentiality issues.

Held et al. (2021) tested another common assumption: the idea that PMIE exposure negatively impacts veterans’ responses to PTSD treatment. Using data from a three-week Cognitive Processing Therapy intensive treatment programme, they found that PMIE exposure and type of index trauma did not predict changes in PTSD and depression. Given that the programme also involved mindfulness and yoga interventions, the authors recommend that future research explore whether standalone trauma-focused therapy achieves similar outcomes in this population.

Last, two papers focused on development of treatment protocols. De la Rie et al. (2021) described a treatment protocol for moral injury based on Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy, which incorporates five stages: information and motivation, imaginary exposure, mementos and writing tasks, finding meaning and activation, and farewell or closure ritual. The protocol was evaluated in a morally injured refugee patient, who responded favourably. A future multiple baseline study may further elucidate treatment effectiveness.

Plans for the development of an intervention for moral injury in UK military veterans were presented by Williamson, Murphy, Aldridge and colleagues (2022). Development involves three stages: conducting a systematic review, co-designing the intervention with patient representatives and other stakeholders, and conducting a pilot study. The intervention will be evaluated using both qualitative and quantitative data.

3. Discussion

Moral injury is an old phenomenon but a relatively new concept. This special collection contains 19 papers on the variety and treatment of moral injury, adding to insights gained in prior special issues on moral injury (Litz & Kerig, 2019; Nieuwsma et al., 2022; Vermetten et al., 2023). We reviewed papers in different populations, from military members to healthcare workers and refugees, as well as papers focusing on treatment. Different focal points were noted, including the impact of PMIEs involving children, the association of PMIEs and personal childhood victimisation, the prevalence of betrayal trauma, and the relationship between moral injury and empathy. As for treatment, points of interest included new treatment initiatives as well as findings that PMIE exposure does not impede help-seeking behaviour and response to PTSD treatment. In addition, we offer three reflections.

First, while originally related to experiences in war and combat, the moral injury concept has now fanned out to experiences of exposure to suffering and stress in other, mostly professional settings. In that fanning out, new challenges arise. It has been widely discussed that the definition of PMIEs and moral injury is still unclear (e.g. Litz et al., 2022). Terms such as high stakes and betrayal are open to a wide range of interpretations. Even within this special collection, definitions do not always concur. This means that psychological phenomena differing widely in severity and persistence may all be labelled as moral injury. PMIEs may range from exposure to professional stressful events to killing in combat; moral injury may range from temporary feelings of being overwhelmed to chronic, debilitating feelings of guilt. On the one hand, this broad interpretation of PMIEs and moral injury shows the desire and need for a clinical concept that describes the consequences of exposure to morally harmful and stressful situations. The moral injury concept brings home that moral suffering and wellbeing are essential elements of mental health and have a place in the therapist’s room. On the other hand, broadening the concept to include exposure to situations or contexts that do not meet the DSM-5 A-criterion and to include symptoms that are limited in severity and persistence, raises issues on recognition and liability as well as pathologizing. Future studies and discussions will help to determine the clinical utility as well as boundaries of the moral injury construct.

Second, as the papers in this special collection show, diversity in the moral injury literature is still limited. Most participants in the studies presented here were from western countries. Application of the moral injury concept to populations other than military veterans has led to an increased inclusion of women. Given that moral beliefs and expectations, exposure to PMIEs, and symptoms of moral injury may differ among genders, cultures and professions, consultation and inclusion of a larger range of individuals and groups exposed to morally burdening situations is called for. As discussed, both the PTSD construct as well as the moral injury concept lean heavily on the experiences of Vietnam veterans. However, women, children and other demographic groups may be exposed to moral transgressions that are different in nature and may have different psychosocial consequences, such as physical or sexual violence by attachment figures (Herman, 1992). Including such experiences in the moral injury literature may provide a more comprehensive picture of how moral transgressions may affect moral functioning and wellbeing.

Last, the papers in this special collection reflect the path taken when a clinical concept matures: that from conceptualisation to clinical utility and treatment. Even though definitions on moral transgressions and moral injury are not sharply defined, the need for interventions to address moral suffering is clear. In the past 15 years, several treatment programmes for moral injury have been proposed and evaluated, including Adaptive Disclosure (Litz et al., 2009; Litz et al., 2016), Trauma-Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy (TrIGR; Norman et al., 2019), and Acceptance & Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury (ACT-MI; Evans et al., 2020). Increasingly it is recognised that moral suffering may severely impact the lives of those affected as well as of their families and loved ones, and that it may need to be addressed therapeutically. This means that moral injury is maturing from a term that describes a type of heartache after moral transgressions, to a circumscribed clinical construct. In that respect, moral injury is following the path of other clinical concepts that originally described types of heartache after interpersonal trauma and loss, and that are now formal DSM-5 or ICD-11 diagnoses: complex PTSD (Maercker et al., 2013) and prolonged grief disorder (Eisma et al., 2022; Killikelly & Maercker, 2017; Prigerson et al., 2021). Whether that path ends in moral injury being included in the DSM or ICD as a PTSD subtype remains to be seen. However, the need to examine tailored interventions to alleviate moral injury is clear.

Regardless of the challenges that lie ahead, it is clear that the moral injury concept has enriched our understanding and therapeutic approach of moral suffering. We hope that the 19 papers presented here will inspire further research and development. Whether or not moral injury becomes a formal diagnosis, the concept appears here to stay.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, A. M., Protopopescu, A., Boyd, J. E., Lloyd, C., Jetly, R., O’Connor, C., Hood, H. K., Nazarov, A., Rhind, S. G., Lanius, R. A., & McKinnon, M. C. (2019). The relation between adverse childhood experiences and moral injury in the Canadian Armed Forces. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1546084. 10.1080/20008198.2018.1546084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout, S. G., Billings, J., Abou Seif, N., Singleton, D., Stein, H., Hegarty, S., Ondruskova, T., Soulios, E., Bloomfield, M. A. P., Greene, T., Seto, A., Abbey, S., & Sheehan, K. (2022). Shared sources and mechanisms of healthcare worker distress in COVID-19: A comparative qualitative study in Canada and the UK. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2107810. 10.1080/20008066.2022.2107810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Rie, S. M., Van Sint Fiet, A., Bos, J. B. A., Mooren, N., Smid, G., & Bersons, B. P. R. (2021). Brief eclectic psychotherapy for moral trauma (BEPMT): Treatment protocol description and a case study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1929026. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1929026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denov, M. (2022). Encountering children and child soldiers during military deployments: The impact and implications for moral injury. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2104007. 10.1080/20008066.2022.2104007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waal, F. B. M., & Preston, S. D. (2017). Mammalian empathy: Behavioural manifestations and neural basis. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 18, 498–509. 10.1038/nrn.2017.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma, M. C., Janshen, A., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2022). Content overlap analyses of ICD-11 and DSM-5 prolonged grief disorder and prior criteria-sets. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1). 10.1080/20008198.2021.2011691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, W. R., Walser, R. D., Drescher, K. D., & Farnsworth, J. K. (2020). The moral injury workbook: Acceptance & commitment therapy skills for moving beyond shame, anger & trauma to reclaim your values. New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fani, N., Currier, J. M., Turner, M. D., Guelfo, A., Kloess, M., Jain, J., Mekawi, Y., Kuzyk, E., Hinrichs, R., Bradley, B., Powers, A., Stevens, J. S., Michopoulos, V., & Turner, J. A. (2021). Moral injury in civilians: Associations with trauma exposure, PTSD, and suicide behavior. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1965464. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1965464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, P. (1949). Some aspects of concentration camp psychology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 105(8), 601–605. doi: 10.1176/ajp.105.8.601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, S., Lamb, D., Stevelink, S. A. M., Bhundia, R., Raine, R., Doherty, M. J., Scott, H. R., Rafferty, A. M., Williamzons, V., Dorrington, S., Hotopf, M., Razavi, R., Greenberg, N., & Wessely, S. (2022). ‘It hurts your heart’: Frontline healthcare worker experiences of moral injury during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2128028. 10.1080/20008066.2022.2128028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held, P., Klassen, B. J., Steigerwald, V. L., Smith, D. L., Bravo, K., Rozek, D. C., Van Horn, R., & Zalta, A. (2021). Do morally injurious experiences and index events negatively impact intensive PTSD treatment outcomes among combat veterans? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1877026. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1877026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, U., Snider, K. L. G., Levy, A., Canetti, D., & Gross, M. L. (2022). To shoot or not to shoot: Experiments on moral injury in the context of West Bank checkpoints and COVID-19 restrictions enforcement. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2013651. 10.1080/20008198.2021.2013651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J., Liddell, B., Bryant, R. A., & Nickerson, A. (2019). A latent profile analysis of moral injury appraisals in refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1686805. 10.1080/20008198.2019.1686805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killikelly, C., & Maercker, M. (2017). Prolonged grief disorder for ICD-11: The primacy of clinical utility and international applicability. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup6), 10.1080/20008198.2018.1476441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany, E. S. (1994). A cognitive model of guilt typology in combat-related PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 7(1), 3–19. 10.1002/jts.2490070103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Belz, Y., Greene, T., & Zerach, G. (2020). Associations between moral injury, PTSD clusters, and depression among Israeli veterans: A network approach. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1736411. 10.1080/20008198.2020.1736411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifton, R. J. (1973). Home from the war: Learning from Vietnam veterans. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Litz, B. T., & Kerig, P. K. (2019). Introduction to the special issue on moral injury: Conceptual challenges, methodological issues, and clinical applications. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 341–349. 10.1002/jts.22405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz, B. T., Lebowitz, L., Gray, M. J., & Nash, W. P. (2016). Adaptive disclosure: A new treatment for military trauma, loss, and moral injury. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Litz, B. T., Plouffe, R. A., Nazarov, A., Murphy, D., Phelps, A., Coady, A., Houle, S. A., Dell, L., Frankfurt, S., Zerach, G., Levi-Belz, Y., & the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium . (2022). Defining and assessing the syndrome of moral injury: Initial findings of the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 923928. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.923928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maercker, A., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., Cloitre, M., Van Ommeren, M., Jones, L. M., Humayan, A., Kagee, A., Llosa, A. E., Roussaeu, C., Somasundaram, D. J., Souza, R., Suzuki, Y., Weissbecker, I., Wessely, S. C., First, M. B., & Reed, G. M. (2013). Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: Proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry, 12(3), 198–206. 10.1002/wps.20057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maftei, A., & Holman, A. C. (2021). The prevalence of exposure to potentially morally injurious events among physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1898791. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1898791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash, W. P., Marino Carper, T. L., Mills, M. A., Au, T., Goldsmith, A., & Litz, B. T. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Events Scale. Military Medicine, 178(6), 646–652. 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarov, A., Fikretoglu, D., Liu, A., Richardson, D., & Thompson, M. (2020). Help-seeking for mental health issues in deployed Canadian Armed Forces personnel at risk for moral injury. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1729032. 10.1080/20008198.2020.1729032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwsma, J. A., Smigelsky, M. A., & Grossoehme, D. H. (2022). Introduction to the special issue “Moral injury care: Practices and collaboration”. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 28(sup1), S3–S8. 10.1080/08854726.2022.2047564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, S., Allard, C., Browne, K., Capone, C., Davis, B., & Kubany, E. (2019). Trauma informed guilt reduction therapy: Treating guilt and shame resulting from trauma and moral injury. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, M. L., & Greene, T. (2021). Understanding the mental health impacts of COVID-19 through a trauma lens. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1982502. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1982502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passardi, S., Hocking, D. C., Morina, N., Sundram, S., & Alisic, E. (2022). Moral injury related to immigration detention on Nauru: A qualitative study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2029042. 10.1080/20008198.2022.2029042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson, H. G., Kakarala, S., Gang, J., & Maciejwski, P. K. (2021). History and status of prolonged grief disorder as a psychiatric diagnosis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 109–126. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-093600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay, J. (1994). Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Heide, F. J. J. (2020). Empathy is key in the development of moral injury. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1843261. 10.1080/20008198.2020.1843261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermetten, E., Jones, C., Smith MacDonald, L., Ter Heide, J. J., Greenshaw, A. J., & Brémault-Phillips, S. (2023). Editorial: Emerging treatments and approaches for moral injury and moral distress. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1125161. 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1125161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Greenberg, N., & Murphy, D. (2019). Moral injury in UK armed forces veterans: A qualitative study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1562842. 10.1080/20008198.2018.1562842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Aldridge, V., Bonson, A., Seforti, D., & Greenberg, N. (2022). Development of an intervention for moral injury-related mental health difficulties in UK military veterans: A feasibility pilot study protocol. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2138059. 10.1080/20008066.2022.2138059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., & Greenberg, N. (2022). Experiences and impact of moral injury in U.K. veterinary professional wellbeing. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2051351. 10.1080/20008198.2022.2051351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Stevelink, S. A. M., Allen, S., Jones, E., & Greenberg, N. (2020). The impact of trauma exposure and moral injury on UK military veterans: A qualitative study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1704554. 10.1080/20008198.2019.1704554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerach, G., & Levi-Belz, Y. (2021). Moral injury and mental health outcomes among Israeli health and social care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent class analysis approach. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1945749. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1945749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]