Abstract

Background

High expression of immune checkpoints (ICs) and senescence molecules (SMs) contributes to T cell dysfunction, tumor escape, and progression, but systematic evaluation of them in co-expression patterns and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was lacking.

Methods

Three publicly available datasets (TCGA, Beat-AML, and GSE71014) were first used to explore the effect of IC and SM combinations on prognosis and the immune microenvironment in AML, and bone marrow samples from 68 AML patients from our clinical center (GZFPH) was further used to validate the findings.

Results

High expression of CD276, Bcl2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3), and SRC was associated with poor overall survival (OS) of AML patients. CD276/BAG3/SRC combination, standard European Leukemia Net (ELN) risk stratification, age, and French-American-British (FAB) subtype were used to construct a nomogram model. Interestingly, the new risk stratification derived from the nomogram was better than the standard ELN risk stratification in predicting the prognosis for AML. A weighted combination of CD276 and BAG3/SRC positively corrected with TP53 mutation, p53 pathway, CD8+ T cells, activated memory CD4+ T cells, T-cell senescence score, and Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) score estimated by T-cell dysfunction.

Conclusion

High expression of ICs and SMs was associated with poor OS of AML patients. The co-expression patterns of CD276 and BAG3/SRC might be potential biomarkers for risk stratification and designing combinational immuno-targeted therapy in AML.

Key Messages

High expression of CD276, BAG3, and SRC was associated with poor overall survival of AML patients.

The co-expression patterns of CD276 and BAG3/SRC might be potential biomarkers for risk stratification and designing combinational immuno-targeted therapy in AML.

Keywords: Prognosis, immune checkpoint, senescence, risk stratification, acute myeloid leukemia

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common subtype of adult leukemia with an incidence of 3.7/100,000 [1–3]. The prognosis of AML is worse with age, whose 5-year survival rate is less than 10% for patients over 60 years old [4]. AML is caused by a variety of genetic factors, environmental changes, and their complex interactions. Patients can be divided into favorable, intermediate, and poor-risk subgroups based on their cytogenetic and molecular biological characteristics. Although AML patients in different categories benefit from chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the prognosis of these patients varies widely [5,6]. Therefore, it is urgent to explore novel biomarkers for more precise risk stratification of AML patients.

The different prognosis of AML patients suggests that other key factors such as cellular immunity and senescence also affect the therapeutic effect [7,8]. As we know, immune evasion and abnormal immune surveillance of cancers play a crucial role in the carcinogenesis and progression of cancers [9,10]. The study of immune checkpoints (ICs), such as PD-1 (programmed cell death 1), in the immune escape of AML cells, makes it one of the most promising targets in recent years [9–11]. Our previous reports suggested that high co-expressions of PD-1/CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4), PD-L2 (PD-1 ligand 2)/CTLA-4, BRD4 (Bromodomain protein 4)/PD-1, and BRD4/PD-L1 (PD-1 ligand 1) correlated with poor overall survival (OS) of AML patients, which might be potential immune biomarkers for designing novel AML therapy [9,11]. However, the combination of ICs could not perform risk stratification for all patients with AML and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) showed a low response rate to AML [12]. It is thought that there are factors other than ICs that may aggravate their immunosuppression, influence their effects on immunotherapy, and contribute to the adverse clinical outcomes of patients with AML.

Cellular senescence is a complex adaptive process implemented by cells that respond to DNA damage [13]. Senescent cells, especially T cells, are characterized by the accumulation of galactosidase glycosidase (SA-β-gal) and the expression of senescence-related secretory phenotype (SASP), as well as the release of cytokines and growth factors, which lead to tumor immune escape and progression [14,15]. Recent studies have shown that exhaustion and senescence are the primary dysfunctional states of effector T cells, which are increasingly considered the main obstacles to the success of cancer immunotherapy [8,14]. Moreover, senescence immunophenotype can be observed in exhausted T cells, indicating a clear relationship between them. Therefore, it is important to eliminate senescence cells or reverse T cell senescence and exhaustion through the replacement, reprogramming, and restoration of the immune system as well as modulation of signaling in tumor sites [14]. Notably, senescence-related genes are significantly associated with adverse clinical outcomes of various cancer patients, which may provide an important reference for the risk stratification for patients [16–18].

In this study, three publicly available datasets (TCGA, Beat-AML, and GSE71014) were first used to investigate the effect of IC and senescence molecule (SM) combinations on outcomes and the immune microenvironment in AML, and bone marrow (BM) samples from 68 AML patients from our clinical center was further used to validate the findings.

Methods

AML patients’ samples

During the period from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2018 a total of 68 BM samples were collected from the newly diagnosed AML patients at Guangzhou First People’s Hospital (GZFPH). Clinical characteristics from 68 AML patients were used for analysis including age, gender, OS time, event, French-American-British (FAB) subtypes, and standard risk stratification, which was shown in Table S1. The last follow-up time was on 1 August 2022 and the median follow-up time for 68 surviving patients was 61.73 months. In addition, BM samples from 5 healthy individuals (HIs) were assigned as controls. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou First People’s Hospital. All participants were provided with written informed consent.

Publicly available datasets

The transcriptome sequencing data of 155 de novo AML patients with complete clinical information and mutation data of 153 patients from the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) database (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/) were downloaded by using UCSC-XENA (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/) [9,11,19]. transcriptome sequencing data was presented in a form of log2(RPKM + 1) and the clinical information was used for analysis including age, gender, OS time, event, FAB subtypes, and standard risk stratification (Table S1). The transcriptome sequencing data of ICs and SMs from 405 de novo AML patients and mutation data from 359 patients were obtained from the Beat-AML database (http://www.vizome.org/aml/) [20]. Corresponding clinical information of the Beat-AML dataset included gender, OS time, event, FAB subtypes, and standard European Leukemia Net (ELN) risk stratification (Table S1). The mRNA expression data and clinical information (OS time and event) of 104 de novo AML patients with normal karyotype from GSE71014 were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) [21,22] (Table S1). Since the TCGA, Beat-AML, and GSE71014 datasets were publicly available, no local ethics committee approval was required.

Acquisition of ICs and SMs

A total of 11 immune checkpoints, including BTLA, CD160, CD276, CTLA4, TIM-3, HHLA2, IDO1, LAG3, PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2, and TIGIT, were used in this study [9]. The list of 279 cellular senescence-related genes was downloaded from the CellAge database (https://genomics.senescence.info/cells/) [23].

Extraction of RNA and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the reverse transcription kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) [24,25]. The expression levels of CD276, Bcl2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3), SRC, CD57, and Killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G (KLRG1) were quantified by the quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), and the β-actin was designed as an internal control, which was performed on Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, California, USA) [9,11]. The list of primers for qRT-PCR was shown in Table S2. The expression levels of CD276, BAG3, SRC, CD57, KLRG1 were presented as 2−ΔΔCT.

Weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA)

The R package ‘WGCNA’ was used to construct a weighted correlation network of ICs and SMs in AML [26]. In the scale-free network, the weighted co-expression relationship among all genes in the adjacency matrix was evaluated by pairwise Pearson coefficient. Genes with high correlations were clustered into the same color module. Additionally, the topological overlap of intramodules was also used for selecting the functional modules.

Construction of nomogram model

For the nomogram model in this study, we referred to the reporting recommendations for tumor biomarker studies and our previous publications on constructing a nomogram model for predicting and visualizing the clinical outcomes of patients with cancer [27–30]. The nomogram model for predicting the OS rate of patients with AML was constructed by ‘foreign’ and ‘rms’ R packages. After the nomogram model assigned a point for each prognostic factor, the total point was obtained to predict OS rates for AML patients.

Estimation of the immune microenvironment

Immune score and the frequency of immune cell subpopulations in the TCGA dataset were downloaded from the TIMER database (http://timer.cistrome.org/) [31,32]. The ‘estimate’ and ‘CIBERSORT’ R packages were used to estimate the immune score and frequency of immune cell subpopulations of AML in the GSE71014 dataset, respectively. KLRG1 and CD57 were considered the most reliable surface marker for T-cell senescence; thus, the T-cell senescence score was calculated as the mean value of KLRG1 and CD57 expression levels [14]. Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) correlates the tumor expression data with the T cell dysfunction signature and predicts tumors with a high correlation to T cell dysfunction as responders for immune checkpoint blockade therapy [33,34]. The TIDE score was downloaded from the TIDE database (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) [34].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 22.0, IBM) and R (version 4.2.1, https://www.r-project.org/), as appropriate. Differences of the two and three groups of quantitative data were determined by Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon and Kruskal–Wallis tests, respectively. Categorical variables were compared by χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. The correlation of two groups of quantitative data was presented by the Spearman coefficient. Differences in Kaplan-Meier curves were compared by log-rank test using the R package ‘survival’. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to select prognostic factors by SPSS. C-index was determined using the R package ‘survcomp’. The optimal cut-points were determined by the ‘maxstat’ package or X-tile software (version 3.6.1), as appropriate [9,27,35]. Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) pathways were performed by the R package ‘GSEABase’ and ‘GSVA’. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The contribution of ICs and SMs to prognostic attributes for patients with AML

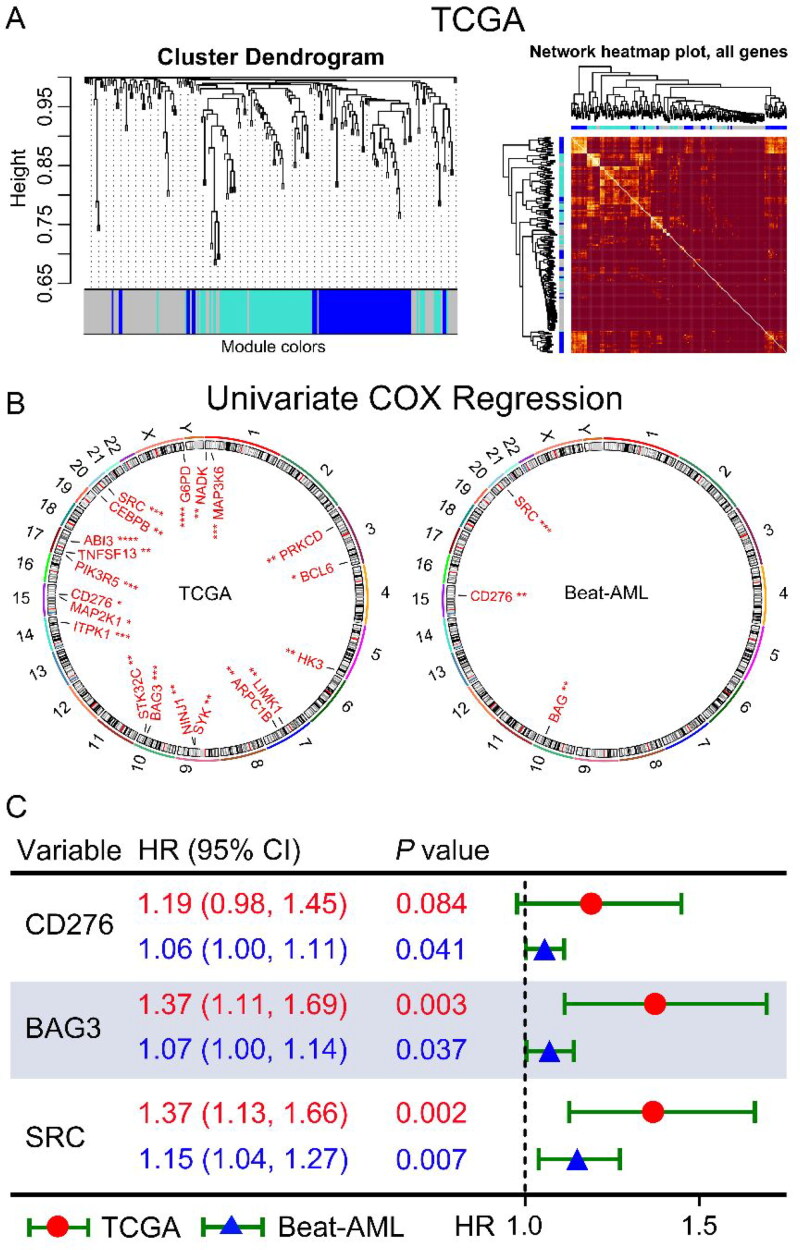

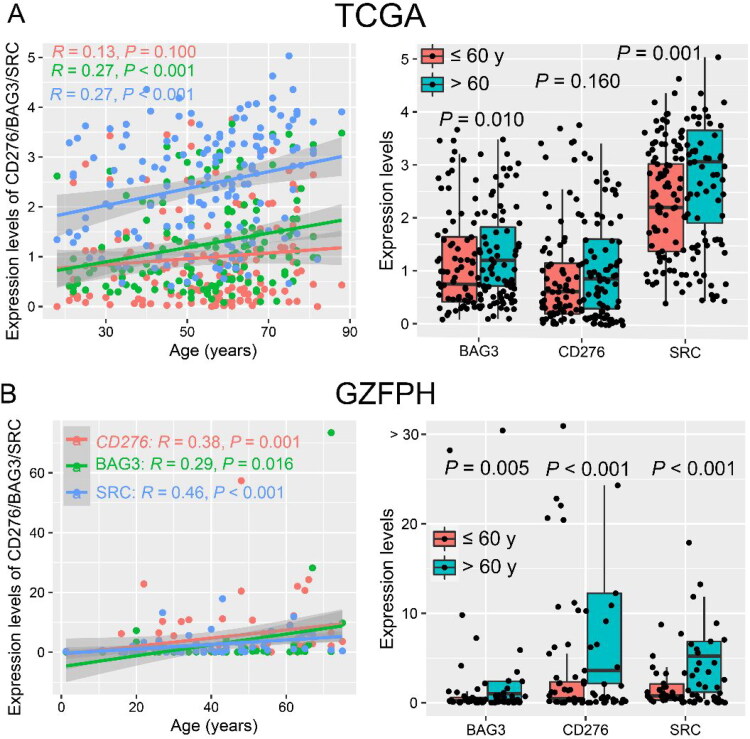

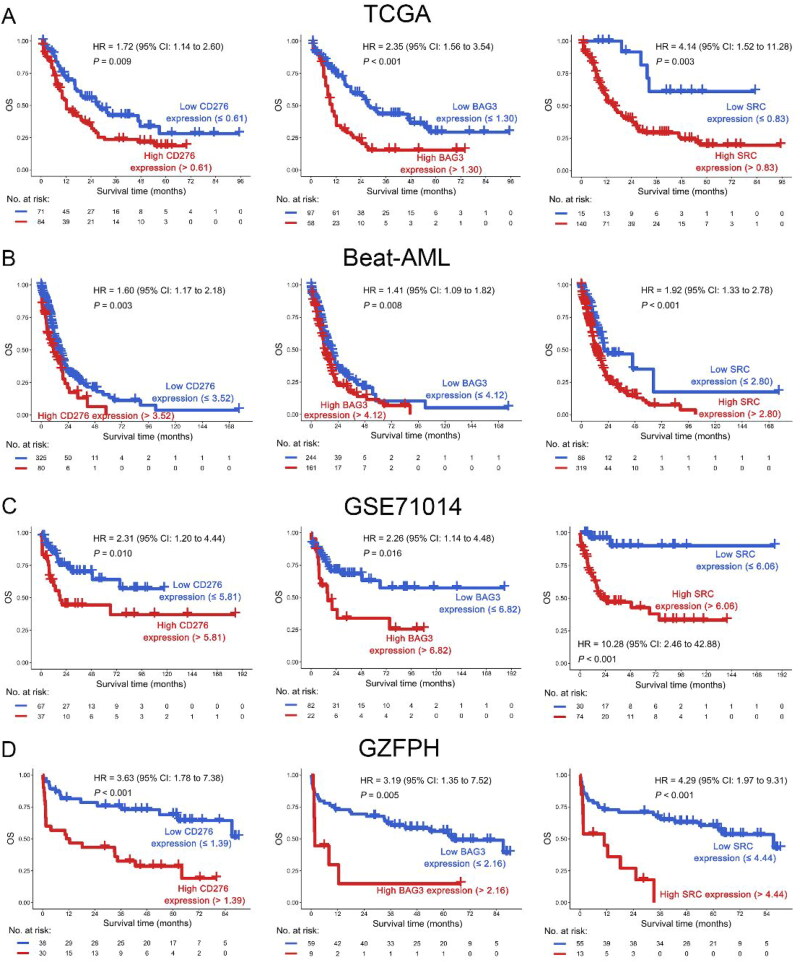

To investigate the co-expression patterns of ICs and SMs, WGCNA was performed on the transcriptome data of AML in the TCGA dataset, and CD276 and 64 SMs were highly correlated in the blue module (Figures 1 and 2(A)). In the blue module, 19 SMs were positively correlated with CD276 and were associated with poor OS in AML patients in the TCGA dataset, as well as BAG3 and SRC in the Beat-AML dataset by univariate COX regression analysis. Hence, increased co-expression of CD276, BAG3, and SRC was significantly associated with poor OS in both TCGA and Beat-AML datasets (p < 0.1, Figure 2(B,C)). Because CD276, BAG3, and SRC were correlated with senescence, the relationship between CD276, BAG3, and SRC and age was analyzed. Interestingly, BAG3 and SRC had a positive correlation with age in the TCGA dataset (p < 0.05, Figure 3(A)). This result was confirmed in the AML sample from our clinical center (GZFPH dataset) (p < 0.05, Figure 3(B)). Moreover, there is a positive correlation between CD276 and age in GZFPH (R = 0.38, p = 0.001) but not in the TCGA dataset (R = 0.13, p = 0.100), which might be due to the cohort size being smaller in GZFPH dataset and the sample size of AML samples needed to be enlarged to further validate this result in the future (Figure 3(A,B)). To better assess the impact of CD276, BAG3, and SRC on the prognosis of patients with AML, patients were divided into low and high-expression subgroups based on the optimal cut-point, and the Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted (Figure S1). The results suggested that AML patients with high expression of CD276, BAG3, and SRC predicted poor OS in the TCGA, Beat-AML, and GSE71014 datasets (p < 0.05, Figure 4(A–C). These findings were confirmed in the GZFPH dataset again (p < 0.01, Figure 4(D)).

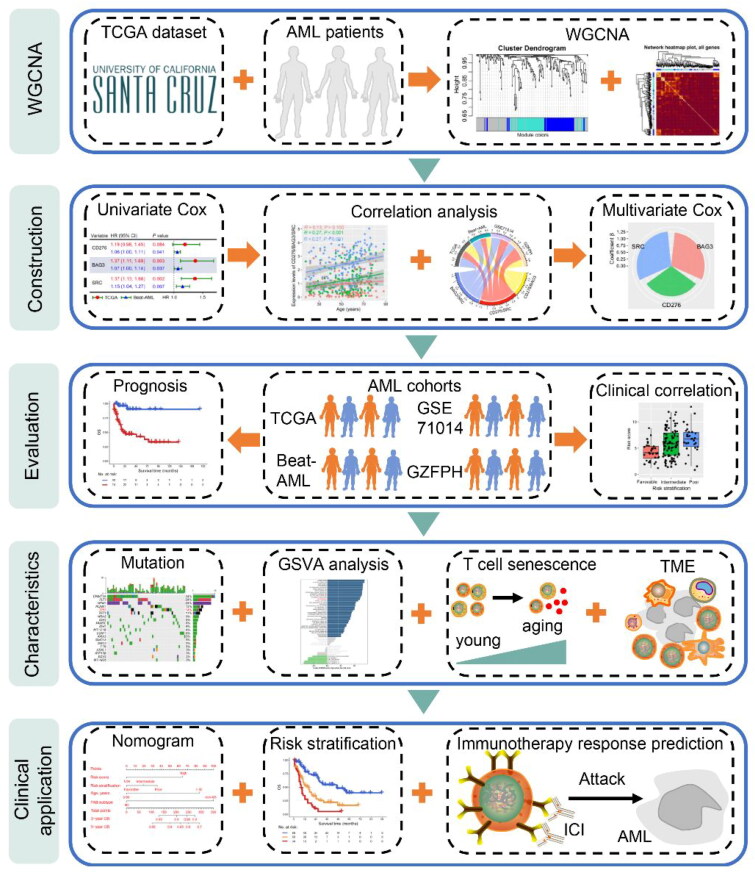

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the study design. Transcriptome sequencing data of AML patients in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were downloaded from the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) database for constructing weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) of immune checkpoint (IC) and senescence molecules. Then, univariate and multivariate COX regression models and correlation analysis were used to select molecules with co-expression patterns to estimate risk scores and construct a prognosis model. TCGA, Beat-AML, GSE71014, and Guangzhou First People’s Hospital (GZFPH) datasets were used to analyze and validate the relationship between the co-expression of immune checkpoints and senescence molecules and prognosis. Moreover, the correlation between risk score and gene mutations, Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) pathways and tumor immune microenvironment was investigated. Finally, the risk score and clinical information were used to establish a nomogram model and risk stratification to predict the overall survival (OS) of AML patients, as well as the immune response to immunotherapy.

Figure 2.

Selection of co-expressed and prognostic ICs and selection of senescence molecules of AML patients. (A) WGCNA was constructed using IC and senescence molecules from 155 AML patients in the TCGA database. Highly correlated genes were assigned to the same color module (left panel), and the correlation between genes in the same color module was shown in a heatmap (right panel). The color scale from red to yellow represents the correlation from weak to strong. (B) Univariate Cox regression was used to analyze the IC and senescence molecules in the blue color module in the TCGA (left panel) and Beat-AML (right panel) datasets. The genes with p < 0.05 were displayed in the circular plot. (C) IC and senescence molecules were associated with poor OS in both TCGA and Beat-AML datasets. *, p < 0.1; **, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

( A–B) CD276, BAG3, and SRC are positively correlated with age in AML patients in the TCGA (A) and GZFPH (B) datasets.

Figure 4.

(A–D) OS analysis of CD276 (left panel), BAG3 (middle panel), and SRC (right panel) in AML patients in the TCGA (A), Beat-AML (B), GSE71014 (C) and GZFPH (D) datasets.

Weighted combinations of CD276 and BAG3/SRC associated with clinical outcome

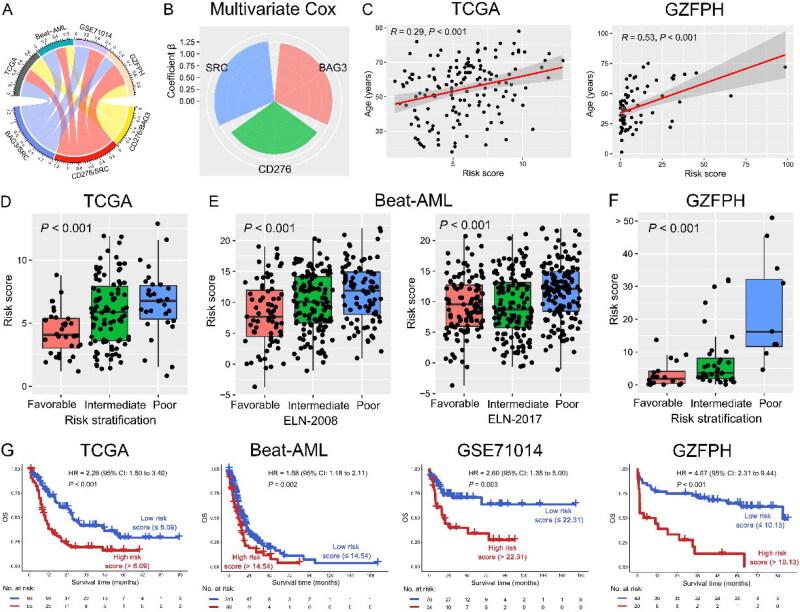

We next sought to assess the relationship between the weighted combinations of CD276/BAG3/SRC and survival outcomes. Multivariate COX regression of these 3 co-expression genes (CD276 and BAG3/SRC) was analyzed, and the following formula can be used to calculate the risk score of each patient according to the coefficients in the TCGA dataset: risk score = 1.12 × (CD276 expression level) + 1.23 × (BAG3 expression level) +1.27 × (SRC expression level) (Figure 5(A,B)). Interestingly, the risk score was positively correlated with age in the TCGA dataset (R = 0.29, p < 0.001). This result was also shown in the GZFPH dataset (R = 0.53, p < 0.001) (Figure 5(C) and S2). Importantly, a high-risk score was significantly associated with poor risk stratification in the TCGA and Beat-AML datasets (p < 0.001, Figure 5(D,E)). These findings were again confirmed in the GZFPH dataset (p < 0.001, Figure 5(F)). Moreover, the risk score was significantly positively correlated with 17-gene leukemia stem cell (LSC17) score in AML in the TCGA dataset (R = 0.40, p < 0.001, Figure S3). Furthermore, patients with AML were divided into low- and high-risk score subgroups according to the optimal cut-point for the risk score (Figure S1). Patients with high-risk scores had significantly shorter OS than patients with a low-risk score in the TCGA, Beat-AML, and GSE71014 datasets (p < 0.01), which was confirmed in the GZFPH dataset [p < 0.001; hazard ratio (HR) = 4.67; 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.31 to 9.44] (Figure 5(G)). Taken together, a weighted combination of CD276 and BAG3/SRC had the potential for risk stratification of patients with AML.

Figure 5.

A weighted combination of CD276, BAG3, and SRC was associated with the prognosis of AML patients. (A) Correlation among CD276, BAG3, and SRC with p < 0.05 in TCGA, Beat AML, GSE71014, and GZFPH datasets. (B) The radar plot shows the contribution of CD276, BAG3, and SRC to OS in the TCGA dataset, which was determined by the coefficients β in the multivariate COX regression model. Risk score = β1* (CD276 expression) + β2* (BAG3 expression) + β3* (SRC expression). (C) Positive correlation between risk score and age in the TCGA (left panel) and GZFPH (right panel) datasets. D-F: Relationship between risk score and favorable, intermediate, and poor risk subgroups TCGA (D), Beat-AML (E), and GZFPH (F) datasets. (G) OS analysis of low- and high-risk patients based on the combination of CD276, BAG3, and SRC in the TCGA, Beat-AML, GSE71014, and GZFPH datasets.

Risk stratification for patients with AML

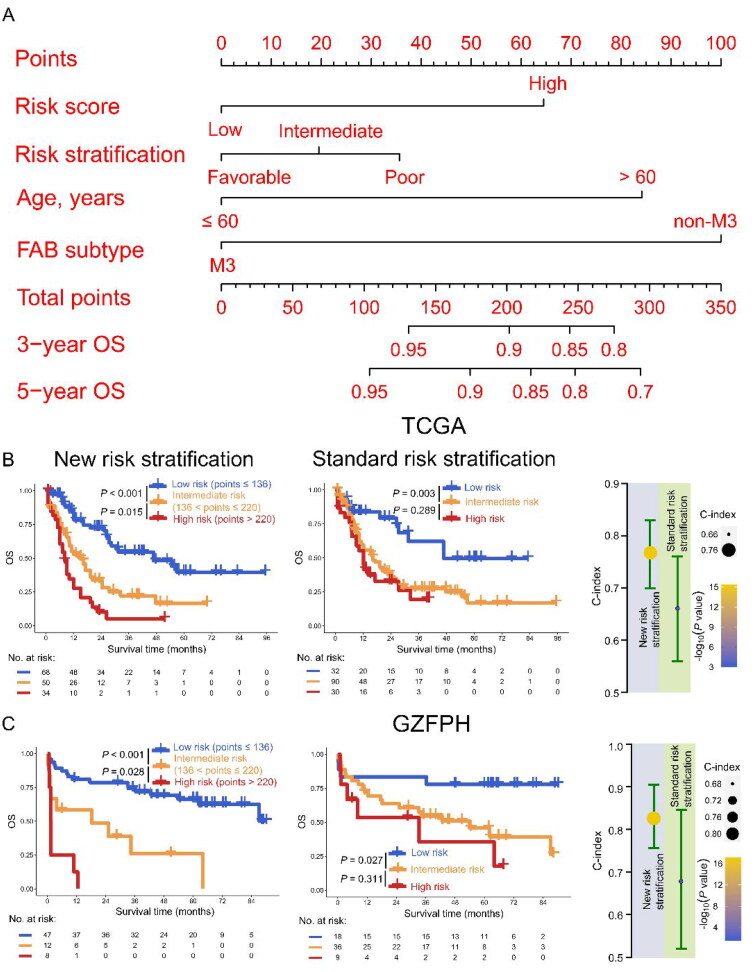

Risk stratification could provide an important reference for clinicians when determining treatment options for AML. Given this idea, we seek to assess the significance of combining risk score and clinical characteristics, which are thought to be more accurate in predicting the prognosis of AML patients, to construct a new risk stratification model. Risk score, LSC17 score, standard ELN risk stratification, gender, age, and FAB subtype were first included in univariate and multivariate Cox analysis for selecting prognostic variables in the TCGA dataset, and the results indicated that risk score and age were independent predictors for AML patients other than LSC17 (HR > 1, p < 0.05, Table S3). Apart from risk score and age, standard ELN risk stratification and FAB subtype were significantly associated with poor prognosis, and them were used to construct a nomogram model to predict OS for AML (Figure 6(A)). Based on the cut-off values of total points (136 and 220) in the nomogram model, AML patients were divided into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk subgroups in the TCGA dataset (low vs. intermediate risk, p < 0.001; intermediate vs. high risk, p = 0.015) (Figure S4 and 6(B), left panel). These results were confirmed in the GZFPH dataset (low vs. intermediate risk, p < 0.001; intermediate vs. high risk, p = 0.028) (Figure 6(C), left panel). However, in terms of standard ELN risk stratification, although intermediate-risk patients had poorer OS than low-risk patients (p = 0.003), intermediate-risk and high-risk subgroups had no significant difference in predicting the OS in the TCGA dataset (p = 0.289) (Figure 6(B), middle panel). These results were again confirmed in the GZFPH dataset (low vs. intermediate risk, p = 0.027; intermediate vs. high risk, p = 0.311) (Figure 6(C), right panel). Notably, the C-index was used to evaluate the model, indicating that the new risk stratification model had a better performance in the TCGA dataset [new vs. standard: 0.76 (95% CI: 0.70 − 0.83) vs. 0.66 (95% CI: 0.56 − 0.76)]. This finding was also shown in the GZFPH dataset [new vs. standard: 0.83 (95% CI: 0.76 − 0.91) vs. 0.68 (95% CI: 0.52 − 0.85)] (Figure 6(B,C), right panels). Therefore, a combination of risk score, standard ELN risk stratification, age, and FAB subtype could improve the performance for constructing a new risk stratification model in AML.

Figure 6.

Construction of risk stratification for AML patients. (A) The risk score, risk stratification, age, and FAB subtype were used to construct the nomogram model in the TCGA dataset. B-C: Kaplan Meier curves of new (left panel) and standard (middle panel) risk stratification were plotted and C-index was used for evaluating the performance of new and standard European Leukemia Net (ELN) risk stratification (right panel) in the TCGA (B) and GZFPH (C) datasets.

The risk score was associated with TP53 mutation and the 53 pathway

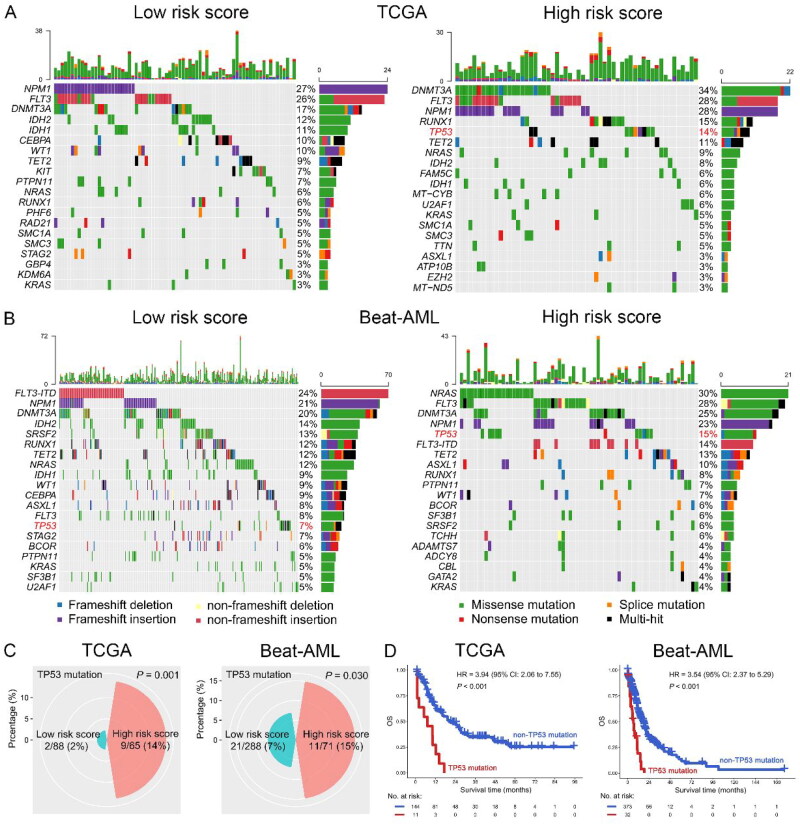

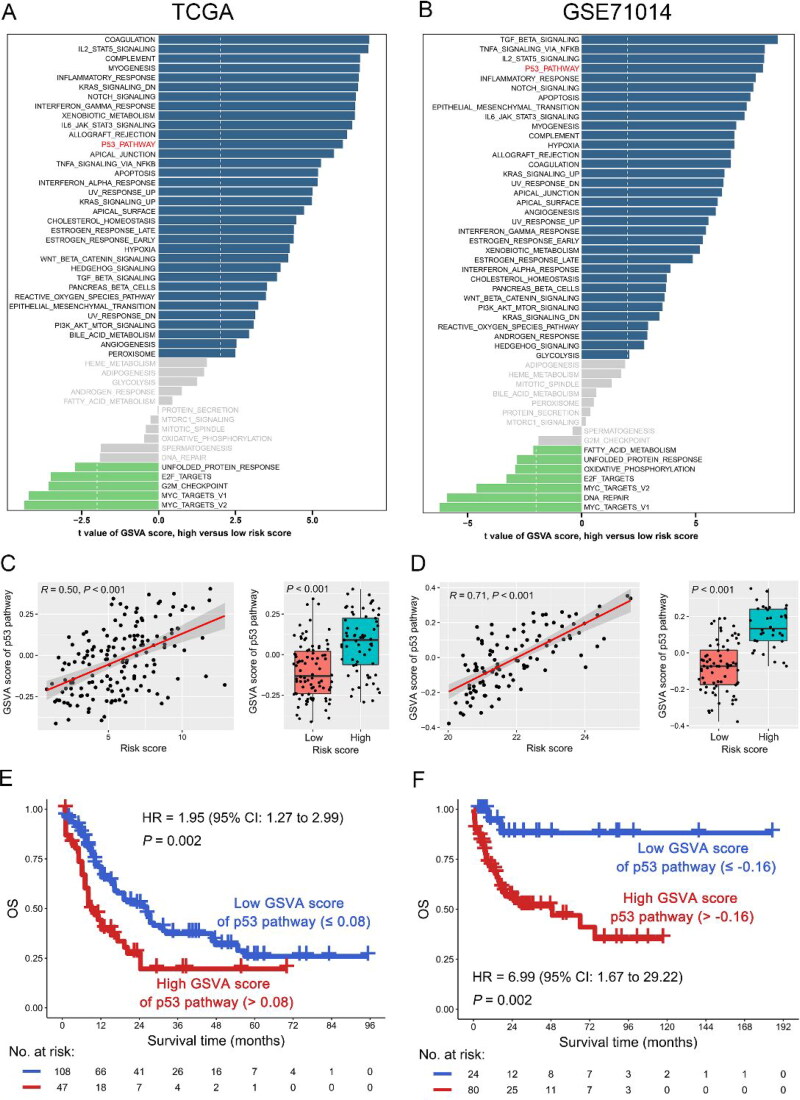

To further investigate the mechanism of risk score affecting the outcome of AML patients, we analyzed the relationship between risk score and gene mutation or pathway. As shown in Figure 7(A–C), the mutation rate of TP53 in the high-risk subgroup was significantly increased compared with the low-risk subgroup in the TCGA dataset [high vs. low risk: 9/65 (14%) vs. 2/88 (2%), p < 0.001]. This finding was confirmed in the Beat-AML dataset [high vs. low risk: 11/71 (15%) vs. 21/288 (7%), p = 0.030]. However, no other gene mutation was positively correlated with TP53 mutation in the both TCGA and Beat-AML datasets, suggesting that there were no co-mutations between TP53 and other genes in AML (Figure S5). Then, TP53 mutation vs. OS was analyzed, suggesting that TP53 mutation was significantly associated with poor OS in the TCGA dataset (HR = 3.94, 95% CI: 2.06 − 7.55, p < 0.001). The result was also found in the Beat-AML dataset (HR = 3.54, 95% CI: 2.37 − 5.29, p < 0.001) (Figure 7D). Interestingly, when we performed GSVA analysis, we found that the risk score was positively correlated with the p53 pathway in both TCGA (R = 0.50, p < 0.001) and GSE71014 (R = 0.50, p < 0.001) dataset (Figure 8(A–D)). Notably, the high GSVA score of the p53 pathway predicted poor OS of AML patients in the TCGA dataset (HR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.27 − 2.99, p = 0.002), which was again confirmed in another dataset (GSE71014, HR = 6.99, 95% CI: 1.67 − 29.22, p = 0.002) (Figure 8(E,F)).

Figure 7.

Correlation between risk score and gene mutation in AML patients. A-B: Mutation landscape of the top 20 genes in low- (left panel) and high-risk score (right panel) subgroups in the TCGA (A) and Beat-AML (B) datasets. C-D: High-risk score was positive correlation with TP53 mutation (C) and TP53 mutation was associated with poor OS (D) in AML patients in the TCGA (left panel) and Beat-AML (right panel) datasets.

Figure 8.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) of high-risk score subgroup in AML. A-B: GSVA pathways of high-risk score subgroup in the TCGA (A) and GSE71014 (B) datasets. C-D: Relationship between risk score and GSVA score of p53 pathway in the TCGA (C) and GSE71014 (D) datasets. E-F: OS analysis of low- and high-GSVA score of p53 pathway based on the optimal cut-point in the TCGA (E) and GSE71014 (F) datasets.

The risk score was positively correlated with the tumor immune microenvironment in AML

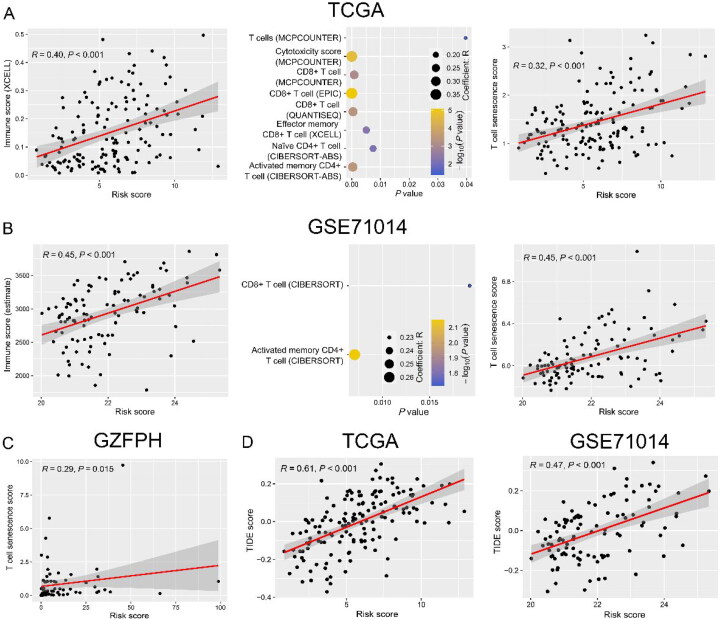

Because the risk score was calculated by the weighted combination of immune checkpoint and senescence molecules, we further analyzed its relationship with the tumor immune microenvironment in AML. As expected, the risk score was positively correlated with immune scores in both TCGA (R = 0.40, p < 0.001) and GSE71014 (R = 0.45, p < 0.001) datasets (Figure 9(A,B), left panels). Then, the correlation between risk score and immune cell subpopulations was investigated, and the results indicated that there was a positive correlation between risk score with CD8+ T cells and activated memory CD4+ T cells in both TCGA and GSE71014 datasets (R > 0, p < 0.05) (Figure 9(A,B), middle panels). Importantly, the risk score was positively correlated with T-cell senescence score in TCGA (R = 0.32, p < 0.001), GSE71014 (R = 0.45, p < 0.001), and GZFPH (R = 0.29, p = 0.015) datasets (Figure 9(A–C)). Patients with high TIDE scores correlated with T-cell dysfunction might benefit from ICI therapy. This study suggested that there was a significantly positive correlation between risk score and TIDE score in both TCGA (R = 0.61, p < 0.001) and GSE71014 (R = 0.47, p < 0.001) datasets (Figure 9(D) and S6).

Figure 9.

Correlation between risk score and tumor immune microenvironment in AML. A-B: Correlation between risk score and immune score (left panel), immune cell subpopulations (middle panel), and T-cell senescence score (right panel) in the TCGA (A) and GSE71014 (B) datasets. (C) The GZFPH dataset was used to validate the relationship between risk score and T-cell senescence score. (D) Risk score had a positive correlation with Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) score in the TCGA (left panel) and GSE71014 (right panel) datasets.

Discussion

Risk stratification plays an indispensable role in the management of AML patients [36]. However, not all patients benefit from it, so it is necessary to explore novel prognostic biomarkers for more precise therapy for AML. Immune exhaustion and senescence will lead to the dysfunction of effector T cells and tumor escape, and their expression levels can affect the response to immunotherapy for cancer patients [14,27,37,38]. Rutella S et al. identified 20 genes from 172 immune effector dysfunction (IED) genes for estimating prognostic index (PI20) scores that could predict the prognosis and the response to immunotherapy for AML patients [8]. However, the number of genes in PI20 is still large; for clinicians, they may hope to find the biomarkers for clinical outcome prediction from minimizing data which is easier for analysis in the clinic. In this study, CD276/BAG3/SRC was considered the optimal immune checkpoint and senescence molecule combination for OS prediction in AML patients, which was significantly less than 20 genes and easier to predict the prognosis of AML patients in the clinic.

ICs were significantly associated with cellular senescence in cancer patients, but systematic evaluation of them in co-expression patterns and prognosis in AML was lacking [14,39]. Hence, analyzing the expression levels of ICs and SMs vs. OS to determine the optimal prognosis stratified population is an important reference for AML patients to benefit from immunotherapy [9,11]. However, a single IC gene has limited performance in prognosis prediction, a combination of ICs and SMs could predict the prognosis of AML more precisely. Moreover, current ICIs have limited clinical activity as monotherapy for highly proliferative AML, the rational combination of ICIs and target therapy has the potential to improve the rates of sustained response [11,40]. Recently, various studies have reported that CD276 was an attractive target for antibody-based immunotherapy and high expression levels of CD276 predicted a poor clinical outcome in cancer patients, including AML [41–43]. The protein encoded by SRC is a tyrosine-protein kinase whose activity can be inhibited by phosphorylation by c-SRC kinase, and SRC plays a role in the regulation of cell growth. Previous reports suggest that SRC was an essential signal transduction molecule and druggable target for FLT3-ITD mediated transformation; thus, SRC might be a therapeutic target in FLT3-ITD + AML [44,45]. The Src and c-Kit kinase inhibitor dasatinib enhances p53-mediated targeting of human AML stem cells by chemotherapeutic agents [45]. Hence, SRC may be an important target for the treatment of AML patients. Moreover, in cancer cells, BAG3 binds to and supports an identical array of prosurvival proteins, and it may represent a therapeutic target: it can promote survival through multiple cell pathways; its expression is induced by stress and growth factors found in cancer cells; high levels of expression correlate directly with chemoresistance; and high levels of BAG3 predict a poor outcome in a variety of cancers, including leukemias. BAG3 protects estrogen receptor-α–positive neuroblastoma and breast cancer cells through an estrogen response element–independent noncanonical autophagy pathway, and also protects non–small cell lung cancer cells from apoptosis. However, cancer cells do not follow a script, and in epithelial thyroid cancer cells, the knockdown of BAG3 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and increased migration and invasion [46]. Although BAG3 is a therapeutic target for patients with cancer, but it is little known in AML [46]. This study demonstrated that high expression of CD276, BAG3, and SRC was significantly associated with poor OS for AML patients. Additionally, CD276 was positively correlated with BAG3 and SRC, and compared with CD276, BAG3, or SRC, a weighted combination of them was a better biomarker in predicting the prognosis for AML. Importantly, a weighted combination of them was positively correlated with the T cell dysfunction signature of TIDE in AML, which indicated that AML patients with high expression subgroup of CD276, BAG3, and SRC might benefit from the immunotherapy plus targeted therapy. In addition, to perform risk stratification more accurately for AML, CD276, BAG2, SRC, standard ELN risk stratification, age, and FAB subtype were used to construct a nomogram model. Interestingly, the new risk stratification derived from the nomogram was better than the standard ELN risk stratification in predicting the prognosis for AML.

More targeted and individualized analysis of IC and SM combinations could predict the prognosis of AML patients. Therefore, the relationship between IC/SM combinations and gene mutations was analyzed, and we found that the weighted combination of CD276 and BAG3/SRC was positively correlated with TP53 mutation in AML. Previous studies have reported that TP53 mutation predicts adverse clinical outcomes, immunosuppressive phenotype, and response to immunotherapy in AML [47–49], which confirmed our findings that the weighted combination of CD276 and BAG3/SRC could predict the prognosis and response to immunotherapy of patients carrying TP53 mutation. Various reports suggest that the process of cell senescence is mainly mediated by two mechanisms: p53/p21 and Rb1/p16 pathways [15, 50]. The Src and c-Kit kinase inhibitor dasatinib enhances the p53-mediated targeting of AML stem cells [45]. These findings are consistent with our results, suggesting that a weighted combination of CD276 and BAG3/SRC had a positive correlation with the p53 pathway in AML. Taken together, co-expression of CD276/BAG3/SRC predicted the adverse outcomes of AML patients carrying TP53 mutation through the p53 pathway.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) inside the tumor microenvironment are a critical role in tumor eradication [27]. Expression of ICs and SMs leads to T-cell exhaustion and senescence, while these genes are induced by immune regulatory factors from TILs [8,14]. Our study showed that a weighted combination of CD276 and BAG3/SRC was significantly positively correlated with CD8+ T cells and activated memory CD4+ T cells, as well as T-cell senescence score in AML. The findings indicated that AML patients with increased co-expression of CD276 and BAG3/SRC might lead to T-cell exhaustion and senescence; thus, combined targeting them might reverse T-cell exhaustion and senescence and benefit from immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

However, this study had limitations. One limitation was that no AML patients in our study received ICI or targeted BAG3/SRC treatment, and the impact of ICI or targeted treatment cannot be assessed. Also, the relatively small sample size of AML restricted any further analysis. Besides, as a retrospective study, statistical bias was almost inevitable.

Conclusions

To our best knowledge, we first identified that CD276 and BAG3/SRC were the optimal combination of ICs and SMs to predict the clinical outcomes of patients with AML, which will provide novel insights into designing combinational immuno-targeted therapy in AML patients.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81500126), the Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (No. 2022A1515012478), the Guangzhou Science and Technology Bureau Project (No. 201904010033), and Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. A2023330).

Author contributions

CTC, CXW, and YPZ: Contributed to the concept development and study design. PPW: Collected the clinical information, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. YLZ and QHC: Performed the experimental research. QQL: Contributed to the follow-up of AML patients and performed qRT-PCR. SYP, WZ, TFD, WJM, and SQW: Diagnosed and treated the patients and provided clinical bone marrow samples. CTC: Coordinated the research and helped to write the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical statemente

This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou First People’s Hospital.

Patient consent

All participants were provided with written informed consent.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Deschler B, Lübbert M.. Acute myeloid leukemia: epidemiology and etiology. Cancer. 2006;107(9):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li M, Zhang D.. DNA methyltransferase-1 in acute myeloid leukaemia: beyond the maintenance of DNA methylation. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):2011–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu D, Tang D, Chai X, et al. Acute leukemia in pregnancy: a single institutional experience with 21 cases at 10 years and a review of the literature. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):567–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimony S, Stahl M, Stone RM.. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(3):502–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estey EH. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2019 update on risk-stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(10):1267–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tallman MS, Wang ES, Altman JK, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(6):721–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA, et al. Enasidenib in mutant IDH2 relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017;130(6):722–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutella S, Vadakekolathu J, Mazziotta F, et al. Immune dysfunction signatures predict outcomes and define checkpoint blockade-unresponsive microenvironments in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(21): e159579. [ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C, Liang C, Wang S, et al. Expression patterns of immune checkpoints in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobo W, Hutten TJA, Schaap NPM, et al. Immune checkpoint molecules in acute myeloid leukaemia: managing the double-edged sword. Br J Haematol. 2018;181(1):38–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen C, Xu L, Gao R, et al. Transcriptome-based co-expression of BRD4 and PD-1/PD-L1 predicts poor overall survival in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:582955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abaza Y, Zeidan AM.. Immune checkpoint inhibition in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Cells. 2022;11(14):2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anerillas C, Herman AB, Rossi M, et al. Early SRC activation skews cell fate from apoptosis to senescence. Sci Adv. 2022;8(14):eabm0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasakovski D, Xu L, Li Y.. T cell senescence and CAR-T cell exhaustion in hematological malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lv Y, Wu L, Jian H, et al. Identification and characterization of aging/senescence-induced genes in osteosarcoma and predicting clinical prognosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:997765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin W, Wang X, Wang Z, et al. Comprehensive analysis uncovers prognostic and immunogenic characteristics of cellular senescence for lung adenocarcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:780461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q, Tang Y, Hu G, et al. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis identifies cellular senescence as a new therapeutic target for cancer: multi-omics analysis and single-cell sequencing validation. Am J Cancer Res. 2022;12(9):4103–4119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tubita A, Lombardi Z, Tusa I, et al. Inhibition of ERK5 elicits cellular senescence in melanoma via the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21. Cancer Res. 2022;82(3):447–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldman MJ, Craft B, Hastie M, et al. Visualizing and interpreting cancer genomics data via the xena platform. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(6):675–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyner JW, Tognon CE, Bottomly D, et al. Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2018;562(7728):526–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C, Chio CL, Zeng H, et al. High expression of CD56 may be associated with favorable overall survival in intermediate-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Hematology. 2021;26(1):210–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chuang MK, Chiu YC, Chou WC, et al. An mRNA expression signature for prognostication in de novo acute myeloid leukemia patients with normal karyotype. Oncotarget. 2015;6(36):39098–39110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avelar RA, Ortega JG, Tacutu R, et al. A multidimensional systems biology analysis of cellular senescence in aging and disease. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C, Wang P, Mo W, et al. Expression profile analysis of prognostic long non-coding RNA in adult acute myeloid leukemia by weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). J Cancer. 2019;10(19):4707–4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CT, Wang P, Mo W, et al. lncRNA-CCDC26, as a novel biomarker, predicts prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(3):2203–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langfelder P, Horvath S.. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang P, Chen Y, Long Q, et al. Increased coexpression of PD-L1 and TIM3/TIGIT is associated with poor overall survival of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(10):e002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, Nie D, Huang Y, et al. Anticancer effects of disulfiram in T-cell malignancies through NPL4-mediated ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Leukoc Biol. 2022; 1124):919–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang PP, Liu SH, Chen CT, et al. Circulating tumor cells as a new predictive and prognostic factor in patients with small cell lung cancer. J Cancer. 2020;11(8):2113–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C, Liu S, Jiang X, et al. Tumor mutation burden estimated by a 69-gene-panel is associated with overall survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2021;10(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li B, Severson E, Pignon JC, et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, et al. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):e108–e110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Q, Cao D, Fang B, et al. Immune-related gene signature predicts clinical outcomes and immunotherapy response in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Med. 2022;11(17):3364–3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med. 2018;24(10):1550–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen C, Liu SM, Chen Y, et al. Predictive value of TCR Vβ-Jβ profile for adjuvant gefitinib in EGFR mutant NSCLC from ADJUVANT-CTONG 1104 trial. JCI Insight. 2022;7(1):e152631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022;140(12):1345–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinterleitner C, Strähle J, Malenke E, et al. Platelet PD-L1 reflects collective intratumoral PD-L1 expression and predicts immunotherapy response in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):7005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tu J, Xu H, Ma L, et al. Nintedanib enhances the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade by upregulating MHC-I and PD-L1 expression in tumor cells. Theranostics. 2022;12(2):747–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lan C, Kitano Y, Yamashita YI, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast senescence and its relation with tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and PD-L1 expressions in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2022;126(2):219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stahl M, Goldberg AD.. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia: novel combinations and therapeutic targets. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(4):37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang LY, Jin Y, Xia PH, et al. Integrated analysis reveals distinct molecular, clinical, and immunological features of B7-H3 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Med. 2021;10(21):7831–7846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kontos F, Michelakos T, Kurokawa T, et al. B7-H3: an attractive target for antibody-based immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(5):1227–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao B, Li H, Xia Y, et al. Immune checkpoint of B7-H3 in cancer: from immunology to clinical immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leischner H, Albers C, Grundler R, et al. SRC is a signaling mediator in FLT3-ITD- but not in FLT3-TKD-positive AML. Blood. 2012;119(17):4026–4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dos Santos C, McDonald T, Ho YW, et al. The src and c-Kit kinase inhibitor dasatinib enhances p53-mediated targeting of human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells by chemotherapeutic agents. Blood. 2013;122(11):1900–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirk JA, Cheung JY, Feldman AM.. Therapeutic targeting of BAG3: considering its complexity in cancer and heart disease. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(16): e149415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sallman DA, McLemore AF, Aldrich AL, et al. TP53 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and secondary AML confer an immunosuppressive phenotype. Blood. 2020;136(24):2812–2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vadakekolathu J, Lai C, Reeder S, et al. TP53 abnormalities correlate with immune infiltration and associate with response to flotetuzumab immunotherapy in AML. Blood Adv. 2020;4(20):5011–5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wen XM, Xu ZJ, Jin Y, et al. Association analyses of TP53 mutation with prognosis, tumor mutational burden, and immunological features in acute myeloid leukemia. Front Immunol. 2021;12:717527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu D, Prives C.. Relevance of the p53-MDM2 axis to aging. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(1):169–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.