Abstract

Forgiveness often discussed as a religious idea is also a popular topic in psychology. Empirical studies have shown that forgiveness decreases anger, anxiety, and depression and increases self-esteem and hopefulness for the future. However, research on the relationship between various outcomes of forgiveness is scarce. Thus, we aimed at examining the mediating roles of anger and hope in the relationship between forgiveness and psychological health outcomes. A sample of college students from a large non-profit university (N = 202) filled out self-report measures on forgiveness, anger, anxiety, depression, hope, and self-esteem. A parallel mediation analysis examining the role of anger and hope in the forgiveness-psychological health link was conducted. Results supported the indirect effect of forgiveness on psychological health through anger and hope, and the two mediators had a comparable size of magnitude. Implications, limitations, and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: Forgiveness, Anger, Hope, Parallel mediation analysis, Psychological health

Forgiveness is an idea commonly found in various religious traditions such as Judaism, Christianity, Confucianism, and Islam (Enright et al., 1992). For instance, Enright et al. (1992) noted that in Judaism and Christianity, divine forgiveness involves forgiveness of sins and human forgiveness is expected to imitate divine forgiveness. More specific to Christianity, Cheong and DiBlasio (2007) argued that it would be important to see the relationship between Christ-like love and forgiveness, as forgiveness is an important component in fulfilling the divine command to love others (see Kim et al., 2021 and Wang Xu et al., 2021 for recent studies on the relationship between forgiveness love). While forgiveness is often recognized as a religious idea, its implications for personal and relational well-being led to scholarly explorations among many psychologists (Baskin & Enright, 2004; Wade et al., 2014). In particular, forgiveness has been noted as a way to resolve anger (and other transgression-related negative emotions) which in turn leads to various psychological and physical health benefits (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015; Lawler et al., 2005; Lee & Enright, 2019; Toussaint et al., 2015; Worthington & Scherer, 2004). However, the empirical support for a reduction in anger mediating the effect of forgiveness on other psychological benefits is surprisingly scarce.

Furthermore, it has been argued that forgiveness is a way to restore hope for the future (Enright, 2001). For instance, forgiveness might open up a possibility for forgivers to reconcile with the offender (if the offender apologizes and accepts forgiveness) or renew strength and energy for forgivers to seek justice in the past injustice that they suffered (Enright, 2001). Through the process of forgiveness, forgivers in addition to abandoning anger are encouraged to discover new meaning in suffering which may turn despair into hope (Enright, 2015). Forgiveness interventions have shown such an effect of forgiveness on both reduced anger and increasing hope among other outcome variables such as anxiety, depression, and self-esteem (Baskin & Enright, 2004; Wade et al., 2014). However, despite the claim that forgiveness reduces anger and restores hope, there has not been any empirical investigation examining the mediating role of hope in the relationship between forgiveness and other outcome variables. Given that forgiveness has shown to have psychological benefits and that forgiveness interventions target the areas of anger and hope, we empirically examined the parallel mediation of anger and hope in the relationship between forgiveness and other commonly measured psychological outcomes, namely, anxiety, depression, and self-esteem (Enright, 2001).

Understanding Forgiveness

There are differing definitions of forgiveness in the psychology literature reflecting the complex nature of forgiveness that involves cognitive, affective, behavioral, motivational, decisional, and interpersonal aspects (Fehr et al., 2010; Worthington & Scherer, 2004). Forgiveness has been discussed as consisting of two types, namely, decisional and emotional forgiveness (Worthington, 2003), as an emotion-focused coping strategy in the face of injustice (Worthington & Scherer, 2004), and also as a disposition or personality trait (Berry et al., 2005). Despite differing conceptualizations of forgiveness that exist within the literature, most researchers consider forgiveness as a human strength that leads to replacing negative emotions with positive emotions toward the offender (Exline et al., 2003; McCullough, 2000). We adopt the view that forgiveness is a moral virtue as are kindness, gentleness, and justice, practiced in the face of another’s injustice by abandoning unhealthy anger (e.g., resentment) and developing goodwill toward the transgressor (Enright, 2012; Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015). It is our assertion that forgiveness is not just an anger reduction strategy; it is offering something good to the offenders in spite of what they have done, which makes forgiveness distinct from other ways that one might adopt to cope with negative emotions such as suppression, catharsis, distraction, relaxation, and so on (Enright, 2001). The paradox of forgiveness is that as forgivers willingly abandon resentment toward those who hurt them and offer goodness to them (i.e., practicing a moral virtue), they themselves heal from the wound and develop a more optimistic view of the future (i.e., the experience of psychological effects distinct from the essence of the virtue of forgiveness).

Unforgiveness and Anger

Anger is a natural response to an experience of another’s transgression, which, if not resolved, can lead to a desire for revenge or displacement of that anger onto other people (Fitzgibbons, 1986). Victims, when introduced to the idea of forgiveness, may be motivated to forgive as a way to cope with discomfort felt in unforgiveness or unresolved negative emotions, which often get in the way of their own well-being (Worthington & Scherer, 2004; Younger et al., 2004). The negative health effects of unforgiveness are widely documented which include but are not limited to: stress, increased depression and anxiety, social isolation, and even compromised physical health due to stress on one’s immune system (Lawler et al., 2005; Toussaint et al., 2015; Worthington & Scherer, 2004).

Unforgiveness originates from the unresolved emotional pain experienced by the victim, for instance, anger, which then becomes an enduring state that affects the victim’s overall health (Berry et al., 2005; Worthington & Scherer, 2004). Unforgiveness may be more than an emotion as it encompasses the negative emotion, judgment, and behavior that ensue the hurtful event (see Stackhouse et al., 2018 for a recent development on the theory of unforgiveness). In other words, unforgiveness may be the state in which the anger that the victim experiences takes hold of their daily lives, eventually impacting their overall well-being (Fitzgibbons, 1986).

Also, unforgiveness has been hypothesized to be influenced by the victim’s rumination on the transgression/injustice, the motivations of the transgressor, or the consequences that are a result of the transgression (Berry et al., 2005). Rumination on the transgression in particular is thought to be linked to establishing and maintaining unhealthy anger which gets in the way of forgiving the transgressor (Berry et al., 2005). A recent study in fact has shown that anger mediates the relationship between rumination on the transgression and forgiveness, further demonstrating the powerful role of anger in unforgiveness (Qinglu et al., 2019). This theory of unforgiveness warrants that forgiveness is a pathway toward resolving anger especially when it is caused by another’s hurtful actions (or inactions).

The Role of Reduced Anger in the Forgiveness Health Link

Empirical research has shown positive relationships between forgiveness and psychological and physical health (Lee & Enright, 2019; Toussaint et al., 2015). Forgiveness is found to be linked with physical health in the areas that include but not limited to: cholesterol, heart health, HIV, hypertension, physical pain, sleep quality, etc. (see Lee & Enright, 2019 for a meta-analytic report on the physical correlates of forgiveness). For instance, Waltman et al. (2008), through a randomized control trial study, demonstrated the effect of forgiveness therapy on participants’ reduced anger and increased forgiveness and heart functioning when compared with the alternative treatment group. Lee and Enright (2014) also conducted a randomized control trial demonstrating the health effects of forgiveness among females with fibromyalgia in the various areas of fibromyalgia-related health such as physical ability to perform daily tasks, pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and so on.

Forgiveness therapy has been largely successful in meeting the criteria for improved psychological health across various populations including but not limited to incest survivors (Freedman & Enright, 1996), those who experienced spousal abuse (Reed & Enright, 2006), substance-dependent clients (Lin et al., 2004), and terminally ill, elderly cancer patients (Hansen et al., 2009). For instance, in one study, a 12-session forgiveness therapy was found to be effective in reducing the substance-dependent individuals’ anger as well as their anxiety and depression and increasing their forgiveness and self-esteem when compared with those in the alternative treatment group (Lin et al., 2004). The improved health of those that have undergone forgiveness interventions in these studies is often seen alongside a reduction in anger, suggesting the mediating role of the release of anger in the health benefits of forgiveness.

Forgiveness and Hope

One widely accepted definition of hope is “the perceived capability to derive pathways to desired goals and motivate oneself via agency thinking to use those pathways” (Snyder, 2002, p.249). Hope consists of three elements: goals, agency, and pathways (Lopez, 2013). It is through hope that we develop a sense of agency which allows us to seek out pathways toward our desired goals without being trapped in the past. The opposite of hope is despair, but the power of hope is that those hopeful remain optimistic about the future and are motivated to work toward contributing to the better future themselves (Peterson, 2006). Desmond Tutu, a South African leader known for his anti-apartheid and human rights efforts, famously asserted that there is no future without forgiveness (Tutu, 1999). While unforgiveness traps victims in emotional prison which prevents them from moving on with their lives, forgiveness helps them overcome their unresolved anger and allows them to seek out new possibilities that they have not seen before (Enright, 2001).

When victims cannot find meaning in suffering, they are likely to experience hopelessness and even “a despairing conclusion that there is no meaning to life itself” (Enright, 2015, p.115). However, through the process of forgiveness, forgivers who find meaning in suffering may develop a more optimistic view of the future (Enright, 2015).

Empirical studies have consistently shown the power of forgiveness in increasing hope for the future alongside reduced anger. Incest survivors who learned to forgive found greater hope for the future when compared with the wait-list control group (Freedman & Enright, 1996). College-age adults who learned to forgive showed a greater level of hope at posttest when compared with the control group, which was maintained at the 10-week follow-up (Luskin et al., 2005). Terminally ill, elderly cancer patients who did not have many months to live found greater hope for the future after learning to forgive for four weeks (Hansen et al., 2009). Abused early adolescent females in Pakistan where disclosing sexual abuse to others is considered a taboo, after learning about forgiveness, reported a higher level of hope at one-year follow-up when compared with the alternative treatment group whose level of hope was rapidly decreasing (Rahman et al., 2018). At-risk adolescents who learned to forgive in a classroom setting showed improvement in both forgiveness and hope when compared with the active control group (Freedman, 2018). Furthermore, there is preliminary evidence suggesting that hope is a mechanism through which forgiveness may protect against depression (Toussaint et al., 2008), and numerous studies have shown that forgiveness is an antidote to depression that often originates from feeling hopeless for the future (Wade et al., 2014).

Despite the theoretical claim that forgiveness leads to health benefits via reduced anger and increased hope as well as the empirical literature supporting the independent effects of forgiveness on anger and hope along with benefits in other areas, the parallel mediation of anger and hope in the forgiveness-psychological health link has not been explored.

Current Study

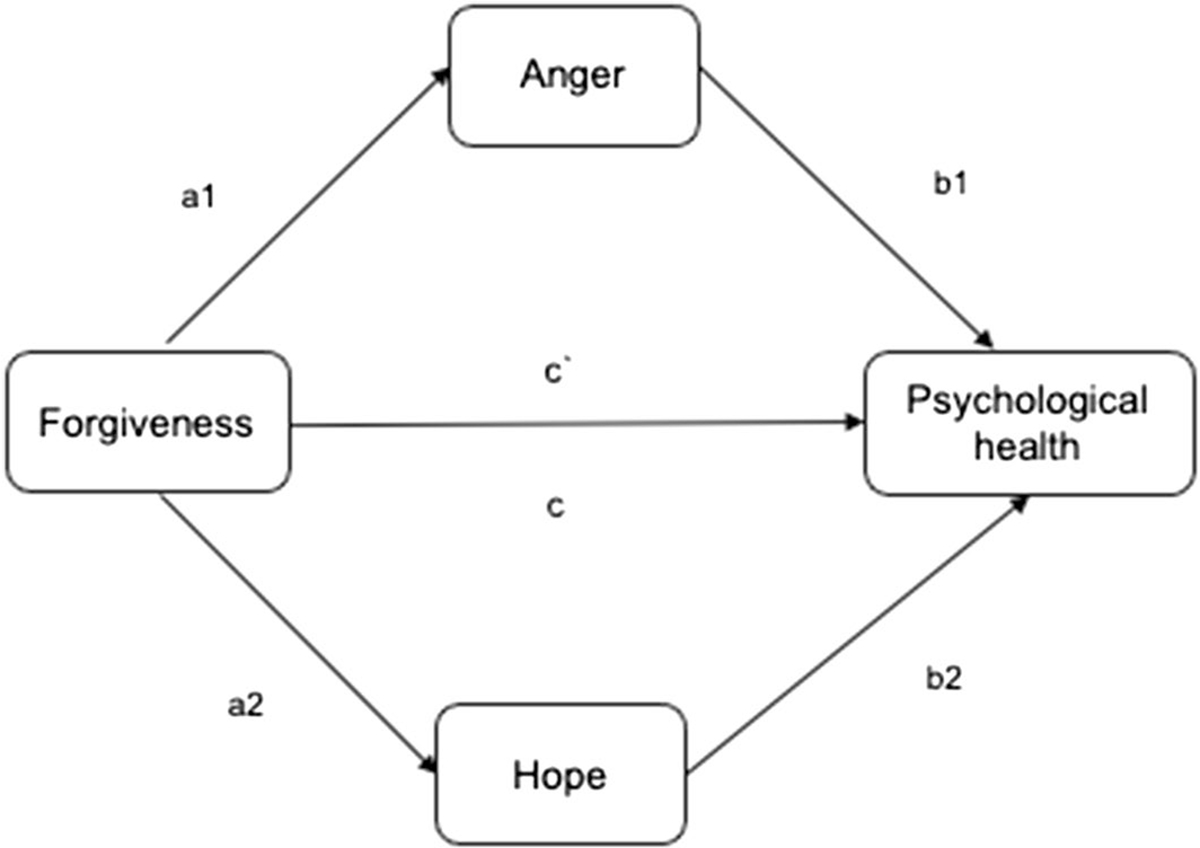

As examined, the prevalence of anger can be seen within unforgiveness, while the reduction of anger occurs during the process of forgiveness. While forgiveness therapy has demonstrated its positive effects on psychological health across various populations, the occurrence of improved health along with a reduction in anger makes it worthwhile to examine the role of anger in the health benefits of forgiveness. Would it be that reduced anger is one of the underlying mechanisms through which forgivers regain psychological health? Furthermore, many research studies have shown the effect of forgiveness on increasing hope across different ages and populations, and forgiveness is noted as a way to restore hope. According to the Process Model of Forgiveness, one of the most widely studied forgiveness intervention model (Enright, 2001; Wade et al., 2014), forgivers first work toward understanding and developing empathy and compassion toward the offender, and then they are encouraged to find meaning in suffering and a new purpose in life during the last phase of the forgiveness process (Enright, 2001). Given the process of forgiveness delineated as the process of abandoning anger and also discovering hope for the future, would it be that anger and hope uniquely mediate the effect of forgiveness on psychological outcomes? We hypothesized that after controlling for covariates (age, gender, race, time since the hurt, and depth of the hurt), forgiveness has indirect effects on psychological health outcomes, namely, anxiety (H1), depression (H2), and self-esteem (H3) through the unique effects of anger and hope. We chose anxiety, depression, and self-esteem as the psychological health outcome variables because they are the most commonly studied psychological health outcomes in the forgiveness literature (Baskin & Enright, 2004; Fehr et al., 2010; Wade et al., 2014). We used a parallel mediation model, examining the effect of forgiveness on each outcome variable via anger and hope because a parallel mediation model allows us to check and compare specific indirect effects (anger alone, hope alone, and anger and hope combined). See Fig. 1 for our hypothesized parallel mediation model.

Fig. 1.

The hypothesized parallel mediation model with anger and hope mediating the effect of forgiveness on psychological health [anxiety (H1), depression (H2), and self-esteem (H3)]

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants, at the age of 18 or older, taking a psychology course(s) at a large non-profit university in Central Virginia, were invited to take an anonymous online survey that included self-report measures on forgiveness, anger, anxiety, depression, hope, and self-esteem. The first page of the survey was the consent form followed by screening questions and a demographic questionnaire. The data collected were a part of a larger data collection effort; however, the current dataset has been neither analyzed nor reported elsewhere. After screening for pseudoforgiveness (n = 2), 202 college students (male = 34; female = 168) whose ages ranged from 18 to 52 (M = 19.87; SD = 3.921) provided the final data for the current study (there were two in their 40’s and one in her/his 50’s and none were in their 30’s). All participants identified as Christian of various denominations/sectors, and 82.7% of the participants (n = 167) identified as white (African-American = 6.9%, Latino/Hispanic = 4%, Asian = 3%, Native American = 0.5%, and Others = 3%).

Measures

Forgiveness

A 30-item version of the 60-item Enright Forgiveness Inventory (EFI-60: Subkoviak et al., 1995; EFI-30: Enright et al., 2021) was used to measure participants’ transgression-specific forgiveness. After having participants recall a specific incident when they were unjustly hurt by another (as well as the depth of hurt and the time since the hurt), participants rated on a scale of 1 (Strongly disagree)—6 (Strongly agree) their current affect, behavior, and cognition toward the offender. An example of the affect subscale is “I feel warm toward him/her.” An example of the behavior subscale is “Regarding the person, I do or would help.” An example of the cognition subscale is “I think he or she is evil.” The total score for EFI-30 ranges from 30 to 180 where higher scores indicate higher forgiveness. Five items from each subscale were reversed coded prior to coming up with the composite forgiveness scores. The final five questions (outside the 30-item forgiveness scale) measured participants’ level of pseudoforgiveness by asking questions about their perception of the incident as unjust and hurtful, and participants with a score of 20 or higher were excluded from the analysis as they might not have been truly hurt or the incident reported was not unjust. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.975.

Anger, Anxiety, and Depression

Five-item anger, 6-item anxiety, and 6-item depression short forms from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS; Cella et al., 2010) were used to measure participants’ state anger, anxiety, and depression. Participants indicated the frequency of each emotional experience that they experienced in the past 7 days on a scale of 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). Sample items are “I felt angry” for the anger scale, “I felt fearful” for the anxiety scale, and “I felt worthless” for the depression scale. The anger scale ranged from 5 to 25, and the anxiety and depression scales rated from 6 to 36 where higher scores indicated higher levels of each emotion experienced within the past 7 days. The Cronbach’s alphas for the current sample were 0.874 (anger), 0.900 (anxiety), and 0.900 (depression).

Self-esteem

The 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg, 1965) was used to measure participants’ self-esteem. All items were rated on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly agree) to 4 (Strongly disagree), and five items were negatively keyed items. After reverse coding the negative items, all items were reverse coded to make higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. Scores ranged from 10 to 40, and the Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.880.

Hope

The 12-item Adult Hope Scale (AHS; Snyder et al., 1991) was used to measure participants’ hope. Four items were fillers, and the remaining 8 items made up agency and pathway subscales. We combined the two subscales to measure participants’ general level of hope for the future (α = 0.829 in this sample). Sample items are “I energetically pursue my goals” and “I can think of many ways to get the things in life that are important to me,” and each item was rated on a scale of 1 (Definitely false) to 8 (Definitely true). Scores ranged from 8 to 64 where higher scores indicated higher hope.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23 as well as Hayes’ (2018) PROCESS macro (version 3). First, we computed bivariate correlations between all study variables, and then, we tested the parallel mediation model (Fig. 1) with anger and hope as mediators in the relationship between forgiveness and anxiety, depression, and self-esteem. Age, gender (dummy coded as female = 1 and male = 0), race (dummy coded as white = 1 versus the rest = 0), time since the hurt, and depth of the hurt were included as covariates. The bootstrap confidence intervals (with 5000 resampling) were used to determine whether or not the indirect effects were statistically significant. Note that when examining indirect effects (mediating effects) using Hayes’ (2018) PROCESS macro (version 3), total effects between the predictor and outcome variables are not required because the statistical significance of total effects is vulnerable to the sample size and there could be any number of mediators between them regardless of the presence of the total effects. In addition, in the following sections, we also reported findings from two additional models to further explore the role played by anger and hope in the forgiveness and health link: (1) serial mediation of anger and hope and (2) serial mediation of hope and anger. Given that our study was correlational, the temporal order between variables cannot be established in this study. We speculated that anger and hope would play comparable roles; however, we still wanted to explore the temporal relation between anger and hope by testing serial mediation models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

There were no missing data, and assumptions of normality were met with kurtosis: max =| 0.551| and skewness: max =|.633|. See Table 1 for means and standard deviations for all measured variables. About 38% of the participants reported that they were hurt by friends of the opposite gender (including current and past romantic relationships), 32% by friends of the same gender, 20% by relatives, and 11% by others (such as employer, pastor, etc.). In total, 31% of them reported that the offense occurred within the past few days or weeks, 33% of them within the several months, and 22% of them at least a year or several years ago. In total, 76% of them reported that they were deeply hurt by the offense (either a great deal of hurt or much hurt), 20% of them some hurt, and 5% of them a little hurt. There were various types of deep injustices that participants reported, but common examples included being cheated by or breaking up with romantic partners, having been ignored, abandoned, or mistreated by family members, and being insulted or gossiped by peers.

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations between study variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1. Forgiveness | 1 | |||||

| 2. Anger | −.19** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Anxiety | − .06 | .39** | 1 | |||

| 4. Depression | −.13 | .53** | .68** | 1 | ||

| 5. Hope | .18** | −.24** | −.27** | −.35** | 1 | |

| 6. Self-Esteem | .12 | −14** | −.50** | −.63** | .43** | 1 |

| Mean | 131.91 | 12.82 | 20.77 | 22.12 | 49.37 | 28.18 |

| SD | 32.59 | 3.99 | 5.37 | 5.18 | 7.32 | 5.36 |

p < .01

Bivariate Associations

Anxiety had a moderate positive relationship with anger (r = 0.39, p < 0.01) and a weak to moderate negative relationship with hope (r = −0.23, p < 0.01). Depression had a strong positive relationship with anger (r = 0.53, p < 0.01) and a moderate negative relationship with hope (r = −0.35, p < 0.01). Self-esteem had a moderate to strong negative relationship with anger (r = 0.40, p < 0.01) and a moderate to strong positive relationship with hope (r = 0.43, p < 0.01). Forgiveness had weak to moderate relationship with anger (r = −0.19, p < 0.01) and hope (r = 0.18, p < 0.01) but was not associated with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem. See Table 1 for correlation coefficients for all study variables.

Parallel Mediation Analyses: Anger and Hope

Hypothesis 1: Anxiety

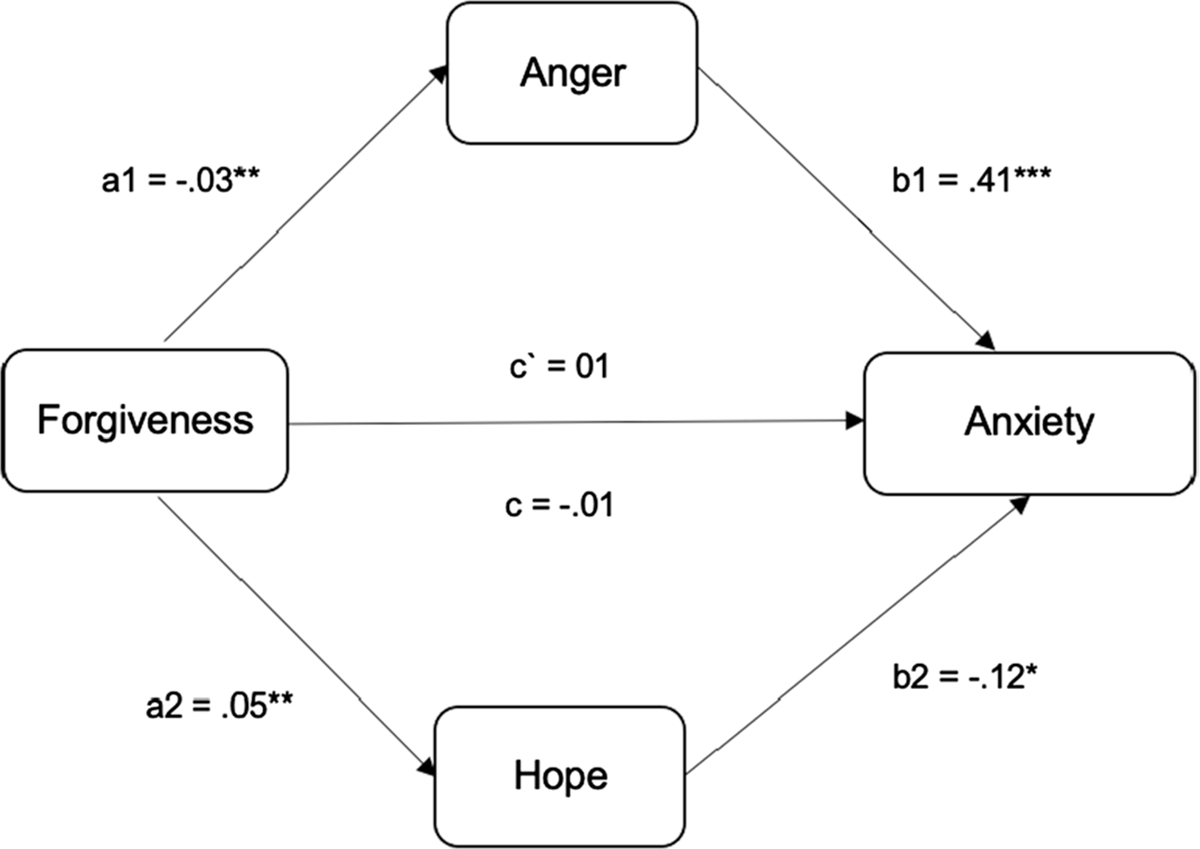

After controlling for age, gender (dummy coded as female = 1 and male = 0), race (dummy coded as white = 1 versus the rest = 0), time since the hurt, and depth of the hurt, findings supported the specific indirect effects of forgiveness on anxiety via anger (a1*b1 = −0.0113, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0226, −0.0029]) and hope (a2*b2 = −0.0058, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0124, −0.0003]). The parallel mediation of anger and hope was also supported (a1*b1 + a2*b2 = −0.0170, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0304, −0.0064]). Findings did not support the total effect of forgiveness on anxiety (c = −0.0074, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0306, 0.0159]) and the direct effect of forgiveness on anxiety (c′ = 0.0097, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0129, 0.0322]). See Fig. 2 for the parallel mediation model with path coefficients for anxiety as the outcome variable provided as an example. For path coefficients for outcome variables, see Table 2. Contrasts between specific indirect paths have shown that the specific indirect effects of forgiveness on anxiety via anger and via hope did not statistically differ, showing a comparable role of anger and hope predicting anxiety (difference = 0.0055, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0050, 0.0183]).

Fig. 2.

The parallel mediation model with anger and hope mediating the effect of forgiveness on anxiety (H1). *p < .05 **p < .01***p < .001

Table 2.

Model path coefficients for anxiety, depression, and self-esteem as the psychological outcomes

| Coefficients | SE | t | P | |

|

| ||||

| a1 | − .03 | .01 | − 3.09 | ** |

| a2 | .05 | .02 | 3.02 | ** |

| b1 | .41 | .09 | 4.57 | *** |

| b2 | − .12 | .05 | − 2.39 | * |

| c | − .01 | .01 | − .62 | ns |

| c′ | .01 | .01 | .85 | ns |

|

| ||||

| Depression | ||||

|

| ||||

| Coefficients | SE | t | P | |

|

| ||||

| a1 | − .03 | .01 | − 3.09 | ** |

| a2 | .05 | .02 | 3.02 | ** |

| b1 | .61 | .08 | 7.72 | *** |

| b2 | − .16 | .04 | − 3.78 | *** |

| c | − .02 | .01 | − 1.34 | ns |

| c′ | .01 | .01 | 92 | ns |

|

| ||||

| Self-Esteem | ||||

|

| ||||

| Coefficients | SE | t | P | |

|

| ||||

| a1 | − .03 | .01 | − 3.09 | ** |

| a2 | .05 | .02 | 3.02 | ** |

| b1 | − .43 | .09 | − 4.98 | *** |

| b2 | .26 | .05 | 5.56 | *** |

| c | .02 | .01 | 1.46 | ns |

| c′ | − .01 | .01 | − .63 | ns |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Hypothesis 2: Depression

After controlling for age, gender (dummy coded as female = 1 and male = 0), race (dummy coded as white = 1 versus the rest = 0), time since the hurt, and depth of the hurt, findings supported the specific indirect effects of forgiveness on depression via anger (a1*b1 = −0.0168, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0307, −0.0048]), hope (a2*b2 = −0.0080, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0151, −0.0022]), and both anger and hope (a1*b1 + a2*b2 = −0.0248, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0403, −0.0105]). Findings did not support the total effect of forgiveness on depression (c = −0.0155, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0384, 0.0073]) and the direct effect of forgiveness on depression (c′ = 0.0093, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0106, 0.0292]). Contrasts between specific indirect paths have shown that the specific indirect effects of forgiveness on depression via anger and via hope did not statistically differ, indicating that each mediator played a comparable role (difference = 0.0087, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0048, 0.0238]).

Hypothesis 3: Self-Esteem

After controlling for age, gender (dummy coded as female = 1 and male = 0), race (dummy coded as white = 1 versus the rest = 0), time since the hurt, and depth of the hurt, findings supported the specific indirect effects of forgiveness on self-esteem via anger (a1*b1 = 0.0118, 95% bootstrap CI [0.0031, 0.0225]), hope (a2*b2 = 0.0128, 95% bootstrap CI [0.0041, 0.0221]), and both anger and hope (a1*b1 + a2*b2 = 0.0247, 95% bootstrap CI [0.0113, 0.0388]). Findings did not support the total effect of forgiveness on self-esteem (c = 0.0178, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0063, 0.0418]) and the direct effect of forgiveness on self-esteem (c′ = −0.0069, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0286, 0.0148]). Contrasts between specific indirect paths have shown that the specific indirect effects of forgiveness on self-esteem via anger and via hope did not statistically differ, indicating the comparable role played by anger and hope (difference = 0.0011, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0124, 0.0139]).

Exploratory Analyses

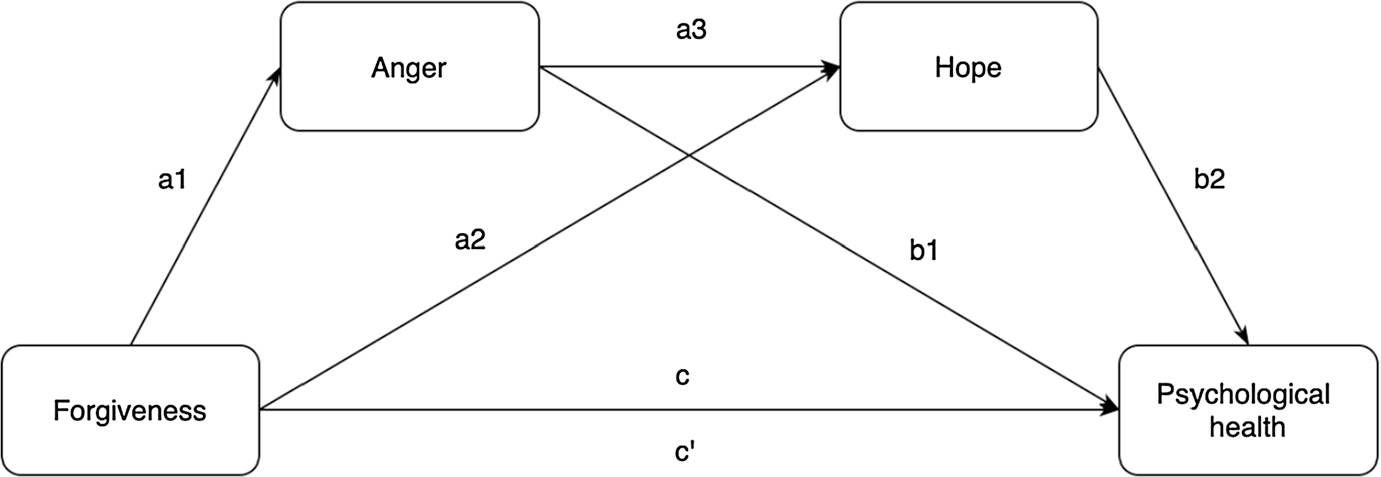

Below, we briefly report the results of exploratory analyses examining the serial mediation of anger and then hope as well as hope and then anger.

Serial Mediation of Anger and then Hope

After controlling for age, gender (dummy coded as female = 1 and male = 0), race (dummy coded as white = 1 versus the rest = 0), time since the hurt, and depth of the hurt, the serial mediation of anger and then hope in the relationship between forgiveness and anxiety was not supported (a1*a3*b2 = −0.0009, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0032, 0.0000]). See Fig. 3 for the tested model. After accounting for the same control variables, the serial mediation of anger and then hope in the relationship between forgiveness and depression was supported (a1*a3*b2 = −0.0013, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0036, −0.0001]). After accounting for the same control variables, the serial mediation of anger and then hope in the relationship between forgiveness and self-esteem was supported (a1*a3*b2 = 0.0021, 95% bootstrap CI [0.0001, 0.0057]).

Fig. 3.

The serial mediation model with anger and then hope mediating the effect of forgiveness on psychological health, namely, anxiety, depression, and self-esteem

Serial Mediation Hope and then Anger

For the tested model in this analysis, the position of anger and hope in the sequence in Fig. 3 is switched so that now the sequence is hope and then anger. After controlling for age, gender (dummy coded as female = 1 and male = 0), race (dummy coded as white = 1 versus the rest = 0), time since the hurt, and depth of the hurt, the serial mediation of anger and then hope in the relationships between forgiveness and anxiety (a1*a3*b2 = −0.0017, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0048, −0.0001]), depression (a1*a3*b2 = −0.0026, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.0068, −0.0001]), and self-esteem (a1*a3*b2 = 0.0018, 95% bootstrap CI [0.0001, 0.0049]) were all supported.

Discussion

Our main findings suggest that anger and hope not only independently but also simultaneously mediate the effect of forgiveness on anxiety, depression, and self-esteem with a comparable size of magnitude. While the positive effects of forgiveness have been rigorously studied, few studies examined the relationships between different outcome variables. Theoretically and also as delineated in the popular forgiveness intervention model, forgiveness has been noted as a way to cope with unresolved anger and restore hope (Enright, 2001; Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015). Therefore, it was deemed worthwhile to study the mediating role of reduced anger and restored hope as the mechanism for the positive benefits of forgiveness.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that specifically focused on testing the parallel mediation of anger and hope in the relationship between forgiveness and psychological health. Past studies have suggested that reduced unforgiveness (a combination of delayed, negative emotions due to the hurtful experience) and negative affect are possible mechanisms through which forgivers enjoy health benefits (Lawler et al., 2005; Worthington & Scherer, 2004). For instance, Lawler et al. (2005) operationally defined negative affect as tension, anger, and depression and showed its mediating role between forgiveness and physical health. However, this study further refined the past findings by specifically focusing on reduced anger as opposed to other studies that focused on negative emotions in general. Furthermore, despite the claim that forgiveness is linked to hope as well as many intervention studies showing the immediate effect of forgiveness on hope, few studies have examined hope as the mechanism of changes (Toussaint et al., 2008). According to the findings in this study, hope not only appeared to mediate the effect of forgiveness on psychological health but also did so with the magnitude comparable to that of anger.

The evidence for the relationships between forgiveness, anger, hope, and psychological well-being is undeniable according to the current state of forgiveness literature (see for example, Wade et al., 2014). However, by showing that forgivers experience greater psychological health (lower anxiety and depression and greater self-esteem) indirectly through reduced anger and improved hope for the future, this study provided empirical evidence for the underlying mechanisms of the forgiveness health link. This finding allows researchers and clinicians to have greater confidence in making the claim that forgiveness reduces anger and restores hope, leading to greater health. Unforgiveness may continue to entrap victims in emotional prison, but forgiveness not only helps victims overcome anger but also helps them find freedom to explore new possibilities for the better future. The restoration of freedom seems to be one of the paradoxes of forgiveness that forgivers experience when they make a courageous decision to let go of the past and move on (Enright, 2001).

Based on the findings of our exploratory analyses attempting to determine whether the indirect effects of forgiveness on outcome variables follow the seriation of anger and then hope or hope and then anger, findings were inconclusive as both produced significant results except for the case of the indirect effect of forgiveness on anxiety via anger and then hope. First, regarding these findings, further investigations are warranted, especially given the use of cross-sectional data in our study, and second, these findings might suggest the complexity of psychological changes that interact with individual differences. Through the process of forgiveness, some might feel reduced anger leading to greater hope and then other outcomes, while others might regain hope first and then experience reduced anger leading to other psychological benefits.

Clinical Implications

Findings in this study present the potential of implementing forgiveness therapy (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015) for helping clients struggling with anger, hopelessness, and other related psychological health issues. For example, those within the field of marriage and family therapy may utilize forgiveness interventions in terminating destructive generational patterns and cycles. According to a longitudinal study of three generations of family members, anger and aggressive behavior that is displayed in parenting is transmitted intergenerationally (Conger et al., 2003). The results of the study were consistent with a social learning perspective in showing that anger occurs as a destructive pattern that is transmitted from parent to child (Conger et al., 2003). Another study that explored the intergenerational effect of forgiveness has shown that forgiveness may be a factor that weakens the relationship between forgivers’ being hurt as a child and being aggressive toward their own child (Lee & Enright, 2009). Based upon these findings, forgiveness interventions could be implemented within families who have adopted the intergenerational transmission of anger to foster hope and so promote psychological well-being in generations to come.

Implications for mental health professionals that treat individuals may include implementing forgiveness therapy in those whose anger is interfering with their lives and health. Individuals that are unable to regulate their anger are likely to present with other issues such as decreased physical health, depression, anxiety, and more; therefore, anger has the ability to impede greatly on a client’s capacity to function (Lawler et al., 2005; Toussaint et al., 2015; Worthington & Scherer, 2004). Rather than primarily treating the symptoms of the anger only, implementing forgiveness therapy with clients struggling with transgression-related anger and other negative health outcomes may undergo an increase in hope and thus restore overall psychological health. An experimental study conducted with college students comparing the effects of a forgiveness program and an anger reduction program showed that the forgiveness program may result in greater benefits when compared with a program that focuses on anger reduction only (Goldman & Wade, 2012).

Finally, a lack of motivation or will to live is a key characteristic that can be seen in individuals with depression according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). According to the definition of hope that is recognized by the current study being the ability to create and achieve goals through one’s ability to motivate the self, hope would be considered absent in a depressed individual that lacks motivation or will to live (Snyder, 2002). Based upon the results of the current study, forgiveness therapy could be considered a viable treatment for clients who suffered an injustice and so are displaying a lack of motivation or will to live. Even in the cases of severe cases of injustices such as being the victim of acid attack violence, recent studies have shown that forgiveness may restore hope for the future, which may in turn help the survivors to seek justice and demand societal changes (Haroon et al., 2021).

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations to be noted. This study used a correlational design; therefore, causal claims cannot be made. However, the proposed model tested in this study originated from a popular forgiveness model in which forgiveness is portrayed as a way to deal with anger and restore hope. Thus, we invite others to continue to explore the role of anger and hope as the mechanisms behind the forgiveness health link and do so using different designs (e.g., longitudinal, experimental).

Second, the generalizability (external validity) of our findings is seriously limited for the following reasons: 1) This study used college students who shared several demographic characteristics in common such as religion, age, race, and gender. All were Christian college students taking a psychology course. Most identified as white females. 2) Also, we used a convenient sample from one non-profit university. In other words, ours was a biased sample without direct external validity. Replications with different demographic groups with a more representative sample would be necessary to increase external validity. Until then, it remains unclear whether anger and hope would play a mediating role between forgiveness and psychological well-being for those who do not share demographic characteristics with the ones who provided data for the current study.

Third, we used anonymous self-report measures for our data collection. We have carefully chosen the measures with known reliability and validity; however, the accuracy of responses still largely depended on participants’ reading of the items, motivation, and memories. In addition, for the anger, anxiety, and depression measures, short-form measures were used instead of long-forms measures. In replication efforts, future researchers may consider using different types of measures such as behavioral measures or long-form measures.

Fourth, although there is a reason to believe that one’s being transgressed against is linked to one’s current state of anger and level of hope, anger and hope were not measured in the context of another’s transgression. Therefore, for future research, the mediating role of transgression-specific anger and hope should be compared to their more general counterparts. Furthermore, forgiving is more than abandoning anger as have discussed in the paper; therefore, it would be interesting to compare forgiveness programs with other empirically supported anger reduction programs and simultaneously examine the role of hope that leads to psychological benefits. Also, given that unforgiveness as a delayed, negative emotion, which includes anger, is not always experienced when transgressed against (Worthington & Scherer, 2004), it would be interesting to examine the effects of forgiveness programs for those who do not appear to have any anger issues but instead have issues with a lack of hope.

Finally, the current study did not consider physical health. Forgiveness is linked to physical health (Lee & Enright, 2019). Then, examining the parallel mediation of anger and hope in the forgiveness-physical health link would help us answer whether anger and hope play the comparable role in predicting physical health.

Despite the limitations of this study and areas for further investigations, this study was the first study that documented the parallel mediation of anger and hope in the relationship between forgiveness and psychological health with a comparable size of magnitude. Thus, we believe that this study opens up opportunities for future researchers to further explore the question of how forgiveness restores health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Human and animal rights All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Date availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI]

- Baskin TW, & Enright RD (2004). Intervention studies on forgiveness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82(1), 79–90. 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00288.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Worthington EL Jr., O’Connor LE, Parrott L III., & Wade NG (2005). Forgivingness, vengeful rumination, and affective traits. Journal of Personality, 73(1), 183–226. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone AA, Rothrock N, Reeve BB, Yount S, Amtmann D, Bode R, Buysse D, Choi S, Cook KF, et al. (2010). The patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63, 1179–1194. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong RK, & DiBlasio FA (2007). Christ-like love and forgiveness: A biblical foundation for counseling practice . Journal of Psychology & Christianity, 26(1), 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Neppl T, Kim KJ, & Scaramella L (2003). Angry and aggressive behavior across three generations: A prospective, longitudinal study of parents and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(2), 143–160. 10.1023/a:1022570107457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD (2001) Forgiveness is a choice: A step-by-step process for resolving anger and restoring hope. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD (2012). The forgiving life. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD (2015). 8 keys to forgiveness. W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD, & Fitzgibbons RP (2015). Forgiveness therapy: An empirical guide for resolving anger and restoring hope. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD, Gassin EA, & Wu C-R (1992). Forgiveness: A developmental view. Journal of Moral Education, 21, 99–114. 10.1080/0305724920210202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD, Rique J, Lustosa R, Song MJ, Komoski MC, Batool I, & Costuna E (2021). Validating the enright forgiveness inventory—30 (EFI-30): International studies. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Exline JJ, Worthington EL Jr., Hill P, & Mc- Cullough ME (2003). Forgiveness and justice: A research agenda for social and personality psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7, 337–348. 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr R, Gelfand MJ, & Nag M (2010). The road to forgiveness: A meta-analytic synthesis of its situational and dispositional correlates. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 894. 10.1037/a0019993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbons RP (1986). The cognitive and emotive uses of forgiveness in the treatment of anger. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 23(4), 629–633. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman SR (2018). Forgiveness as an educational goal with at-risk adolescents. Journal of Moral Education, 47, 415–431. 10.1080/03057240.2017.1399869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman SR, & Enright RD (1996). Forgiveness as an intervention goal with incest survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(5), 983. 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman DB, & Wade NG (2012). Comparison of forgiveness and anger-reduction group treatments: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 22, 604–620. 10.1080/10503307.2012.692954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MJ, Enright RD, Klatt J, & Baskin TW (2009). A palliative care intervention in forgiveness therapy for elderly terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Palliative Care, 25(1), 51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon Z, Iftikhar R, Kim JJ, Volk F, & Enright RD (2021). A randomized controlled trial of forgiveness intervention program with female acid attack survivors in Pakistan. Journal of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 10.1002/cpp.2545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Kaplan HM, Oliver MJ, & Whitmoyer NS (2021). Comparing compassionate love and empathy as predictors of transgression-general and transgression-specific forgiveness. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 49(2), 112–125. 10.1177/0091647120926482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler KA, Younger JW, Piferi RL, Jobe RL, Edmondson KA, & Jones WH (2005). The unique effects of forgiveness on health: An exploration of pathways. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28(2), 157–167. 10.1007/s10865-005-3665-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-R, & Enright RD (2009). Father’s forgiveness as a moderator between perceived unfair treatment by family of origin member and anger with own children. The Family Journal, 17, 22–31. 10.1177/1066480708328474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-R, & Enright RD (2014). A forgiveness intervention for women with fibromyalgia who were abused in childhood: A pilot study. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 1, 203–217. 10.1037/scp0000025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-R, & Enright RD (2019). A meta-analysis of the association between forgiveness of others and physical health. Psychology & Health, 34, 626–643. 10.1080/08870446.2018.1554185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WF, Mack D, Enright RD, Krahn D, & Baskin TW (2004). Effects of forgiveness therapy on anger, mood, and vulnerability to substance use among inpatient substance-dependent clients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 1114. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez SJ (2013). Making hope happen: Create the future you want for yourself and others. Atria Books. [Google Scholar]

- Luskin FM, Ginzburg K, & Thoresen CE (2005). The efficacy of forgiveness intervention in college age adults: Randomized controlled study. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, 29, 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME (2000). Forgiveness as human strength: Theory, measurement, and links to well-Being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 43–55. 10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.43 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C (2006). A primer in positive psychology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qinglu W, Peilian C, Xianglong Z, Xiuyun L, & Hongfei D (2019). Roles of anger and rumination in the relationship between self-compassion and forgiveness. Mindfulness, 10, 272–278. 10.1007/s12671-018-0971-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Iftikhar R, Kim JJ, & Enright RD (2018). Pilot study: Evaluating the effectiveness of forgiveness therapy with abused early adolescent females in Pakistan. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 5, 75–87. 10.1037/scp0000160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed GL, & Enright RD (2006). The effects of forgiveness therapy on depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress for women after spousal emotional abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 920. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 249–275. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, et al. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 570–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackhouse MRD, Ross RWJ, & Boon SD (2018). Unforgiveness: Refining theory and measurement of an understudied construct. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57, 130–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subkoviak MJ, Enright RD, Wu Ch., Gassin EA, Freedman S, Olson LM, & Sarinopoulos I (1995). Measuring interpersonal forgiveness in late adolescence and middle adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 18, 641–655. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint LL, Williams DR, Musick MA, & Everson-Rose SA (2008). Why forgiveness may protect against depression: Hopelessness as an explanatory mechanism. Personality and Mental Health, 2, 89–103. 10.1002/pmh.35 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint LL, Worthington EV Jr., & Williams DR (Eds.). (2015). Forgiveness and health. New York: Springer. 10.1007/978-94-017-9993-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tutu D (1999). No future without forgiveness. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Wade NG, Hoyt WT, Kidwell JE, & Worthington EL Jr. (2014). Efficacy of psychotherapeutic interventions to promote forgiveness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(1), 154. 10.1037/a0035268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltman R, Coyle E, & Holter, & Swoboda,. (2008). The effects of a forgiveness intervention on patients with coronary artery disease. Psychology & Health, 24, 11–27. 10.1080/08870440801975127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Xu J, Kim JJ, Olmstead N, & Enright RD (2021). The development of forgiveness and other-focused love. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 10.1177/00916471211034514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington EL Jr. (2003). Forgiving and reconciling: Bridges to wholeness and hope. InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington EL, & Scherer M (2004). Forgiveness is an emotion-focused coping strategy that can reduce health risks and promote health resilience: Theory, review, and hypotheses . Psychology & Health, 19(3), 385–405. 10.1080/0887044042000196674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Younger JW, Piferi RL, Jobe RL, & Lawler KA (2004). Dimensions of forgiveness: The views of laypersons. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 837–855. 10.1177/0265407504047843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.