Abstract

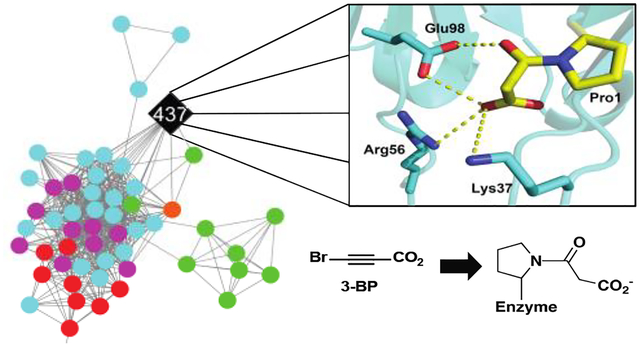

The amino-terminal proline (Pro1) has long been thought to be a mechanistic imperative for tautomerase superfamily (TSF) enzymes, functioning as a general base or acid in all characterized reactions. However, a global examination of more than 11,000 nonredundant sequences of the TSF uncovered 346 sequences that lack Pro1. The majority (~85%) are found in the malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase (MSAD) subgroup where most of the 294 sequences form a separate cluster. Four sequences within this cluster retain Pro1. Because these four sequences might provide clues to assist in the identification and characterization of activities of nearby sequences without Pro1, they were examined by kinetic, inhibition, and crystallographic studies. The most promising of the four (from Calothrix sp. PCC 6303 designated 437) exhibited decarboxylase and tautomerase activities and was covalently modified at Pro1 by 3-bromopropiolate. A crystal structure was obtained for the apo enzyme (2.35 Å resolution). The formation of a 3-oxopropanoate adduct with Pro1 provides clues to build a molecular model for the bound ligand. The modeled ligand extends into a region that allows interactions with three residues (Lys37, Arg56, Glu98), suggesting that these residues could play roles in the observed decarboxylation and tautomerization activities. Moreover, these same residues are conserved in 16 nearby, non-Pro1 sequences in a sequence similarity network. Thus far, these residues have not been implicated in the mechanisms of any other TSF members. The collected observations provide starting points for the characterization of the non-Pro1 sequences.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The tautomerase superfamily (TSF) consists of more than 11,000 members that sort into five major subgroups.1 The members share a β–α–β building block and have a catalytic amino-terminal proline that functions as a general base or acid.1–4 There are no known cofactors that assist in catalysis. The TSF is an ideal model for how Nature repurposes a single (and simple) scaffold to diversify activity. In general, TSF members consist of a single β–α–β unit per monomer (homo- or heterohexamers) or two consecutively fused β–α–β units per monomer (trimers).1 TSF enzymes carry out primarily tautomerization, dehalogenation, hydration, and decarboxylation reactions.1,3 Thus far, Pro1 is a critical residue for the activities of the experimentally known members.

In the course of the analysis of the TSF sequence similarity network (SSN), 346 sequences were unexpectedly found to lack Pro1.1 Mapping of these sequences onto the SSN showed that they are distributed across the superfamily, but are most prevalent in the malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase (MSAD) subgroup (294 of 346).1 The broad distribution and significant proportion of non-Pro1 sequences in the TSF (~3%) suggest the coded proteins could have significantly different enzymatic functions/mechanisms than the characterized TSF enzymes (assuming some or all function as enzymes). In order to characterize the potential new chemistry and mechanisms, we examined the properties of four nearby Pro1 sequences as a first step. It was anticipated that the existing body of work on the mechanisms of Pro1 enzymes in the MSAD subfamily (and in the TSF), might help these efforts and that the results might be applicable to the non-Pro1 sequences.

To date, seven MSADs have been purified and characterized to varying degrees.5–10 These seven MSADs are considered the canonical MSADs where Pro1 plays a critical role. Two MSADs (from Pseudomonas pavonaceae 1705–8 and Coryneform bacterium strain FG419, known respectively as Pp and FG41 MSAD) have been extensively investigated by sequence, inhibition, crystallographic, and mutagenic studies. Both are part of degradative pathways for 1,3-dichloropropene, a soil fumigant, and convert malonate semialdehyde (MSA) to acetaldehyde.5 Acetaldehyde is presumably channeled into the Krebs Cycle as acetyl CoA.

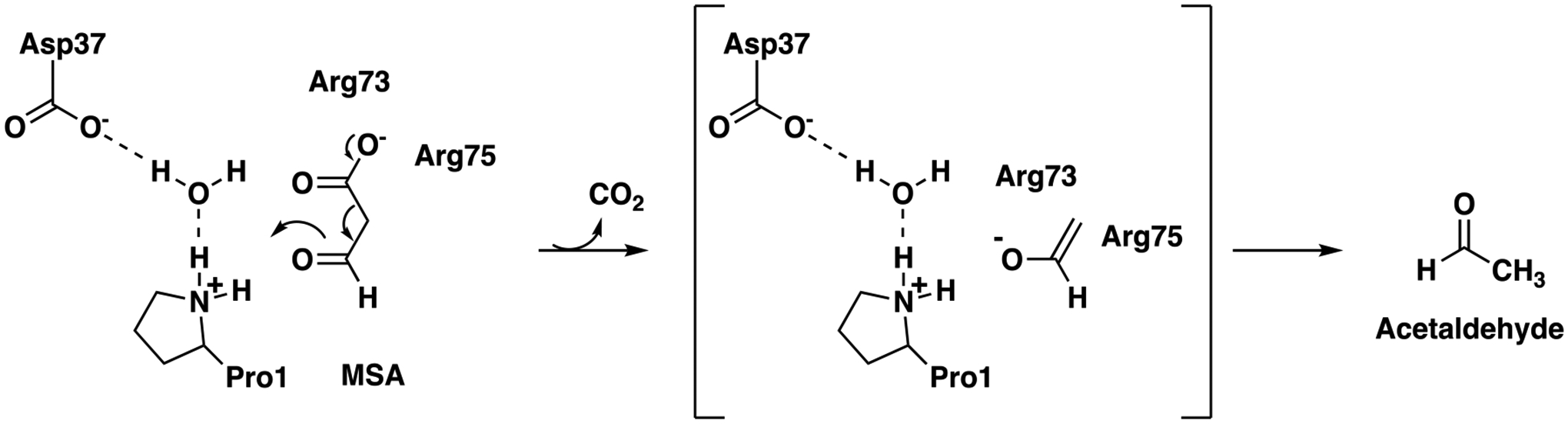

The key residues for the Pp MSAD have been identified as Pro1, Asp37, and a pair of arginines (Arg73 and Arg75).5–8 In addition, there is a hydrophobic wall (Trp114, Phe116, Phe123, and Leu128) that facilitates decarboxylation. Much is known about Pro1 in the mechanism, but the exact role remains elusive. Both Pro1 and Asp37 are in the midst of a hydrogen bond network where one water molecule is within hydrogen bonding distance of the prolyl nitrogen and another water molecule is within hydrogen bonding distance of a carboxylate oxygen of Asp37. In the working hypothesis for the mechanism, a cationic Pro1 (pKa ~9.2, as measured by 15N NMR spectroscopy6), an oxyanion hole of some sort, or both polarize the C-3 carbonyl group (Scheme 1).

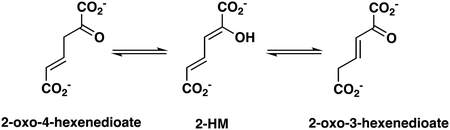

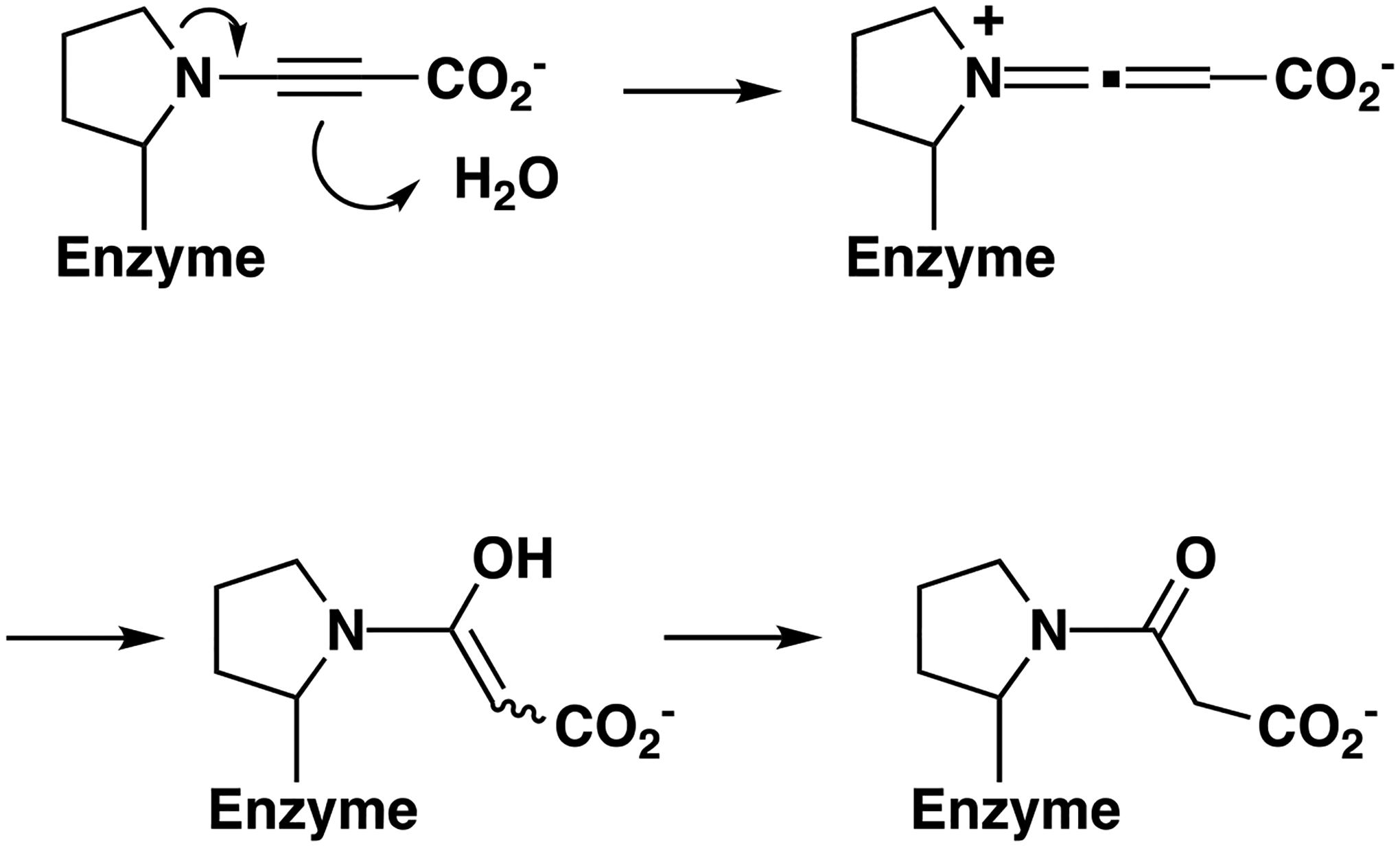

Scheme 1.

Proposed Mechanism for Pp MSAD.

The hydrogen bond network is presumed to be partially responsible for the pKa of Pro1.8 The pair of arginines (one or both) stabilize the developing enolate and/or position the carboxylate group so that the C1-C2 bond is parallel to the p-orbitals of the 3-carbonyl group. This conformation along with positioning the carboxylate group in front of the hydrophobic wall facilitate decarboxylation of the β-keto acid.8 The proposed roles are based on an apo MSAD structure and the interactions seen in a structure of the enzyme covalently modified at Pro1 by a 3-oxopropanoate adduct.8,9

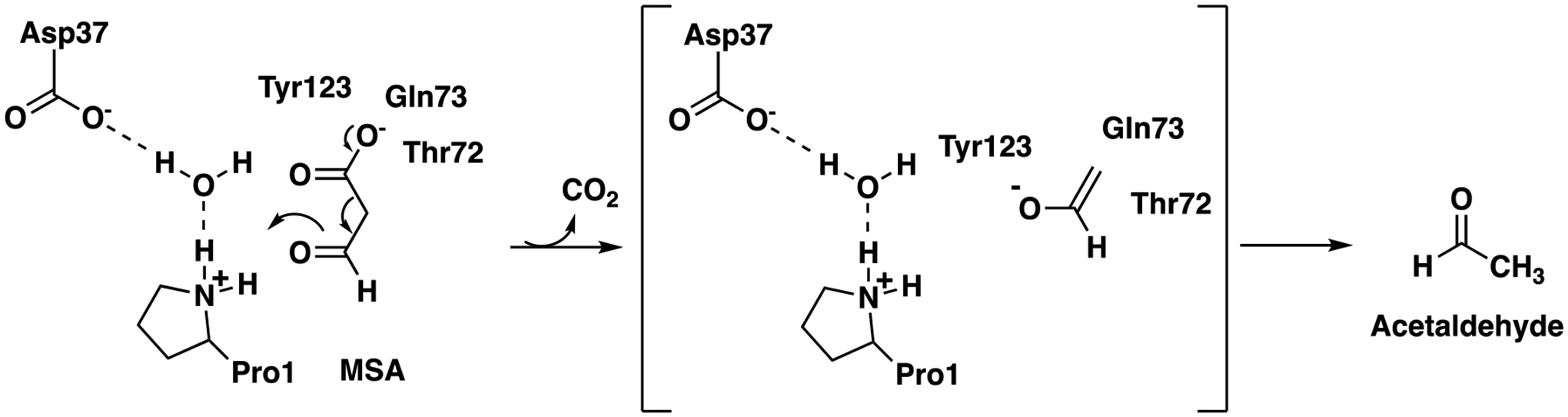

A variation on this mechanism is seen in FG41 MSAD, which has 38% sequence identity (65% similarity) with Pp MSAD, but lacks Arg73 and the second arginine (Arg76) is shifted in position by the insertion of a glycine.9 The mechanism is somewhat similar, but other groups play roles, notably, Gln73, Thr72, and Tyr123 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Proposed Mechanism for FG41 MSAD.

These three residues could play analogous roles to Arg73 and Arg75. The remaining five MSADs have Pro1, Asp37, sometimes Arg73, Arg75/76, and the hydrophobic wall.10 In all cases, Pro1 is essential for activity.

Notably, there is little sequence similarity between the sequences in the set of canonical MSADs and those in the set of non-Pro1 sequences. Moreover, the genomic context for the latter set of sequences is not useful. Most of non-Pro1 sequences are in one cluster in the MSAD subgroup. Within this cluster, four sequences retain Pro1.1 Given the proximity of these four sequences to those without Pro1, characterization of the proteins coded by the Pro1 sequences might provide information that could be used in the characterization of the non-Pro1 sequences. Hence, these four sequences served as starting points.

Two of the four sequences (from Calothrix sp. PCC 6303 and Rivularia sp. PCC 7116) could be expressed and the proteins purified (designated 437 and JJ3). These proteins were subjected to kinetic, inhibition, and crystallographic study. Kinetic analysis showed that both have tautomerase activity (using phenylenolpyruvate and 2-hydroxymuconate) and weak MSAD activity. In addition, mass spectral analysis indicated that Pro1 was covalently modified by 3-bromopropiolate (3-BP) to result in a 3-oxopropanoate adduct. The crystal structure of the enzyme and a model of the 3-oxopropanoate adduct on Pro1 show interactions with three residues (Lys37, Arg56, and Glu98). Bioinformatics and sequence analysis identified the same three residues in 16 nearby sequences that did not have Pro1. Although the biological substrates are not known for 437 and JJ3, these residues might play roles in the observed tautomerization and decarboxylation mechanisms. This is the first time these three residues have been identified in TSF members as potential binding and catalytic ligands in the processing of substrate or inhibitor. The results and their implications for the characterization of the functions and mechanisms of the proteins coded by the non-Pro1 sequences are discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials.

Chemicals, biochemicals, buffers, and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO), Fisher Scientific Inc. (Pittsburgh, PA), Fluka Chemical Corp. (Milwaukee, WI), or EMD Millipore, Inc. (Billerica, MA). 2-Hydroxymuconate (2-HM)11 and 3-bromopropiolate (3-BP)12 were synthesized by the indicated references. Phenylenolpyruvate (PP) was purchased from Fluka Chemical Corp. (Milwaukee, WI) as the crystalline free acid, which exists exclusively in the enol form. Propiolic acid (98%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and purified further prior to use by distillation. N2 was purified by a literature procedure.13 N2 is an enzyme from Gammaproteobacteria bacterium SG8_31 (UniProt accession A0A0S8FF56) and is in the 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase (4-OT) subgroup, as described elsewhere.13 The DEAE Sephadex, Phenyl-Sepharose 6 Fast Flow, and Sephadex G-75 resins were obtained from GE Healthcare Bio-sciences (Pittsburgh, PA). The Econo-Column® chromatography columns were obtained from BioRad (Hercules, CA). The Amicon stirred cell concentrators and the ultrafiltration membranes (3,000 or 5,000 Da, MW cutoff) were purchased from EMD Millipore Inc.

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids.

Four genes were codon-optimized for expression in Escherichia coli, synthesized, and cloned into the expression vector pJ411 by ATUM (Newark, CA). The sequences for the genes were obtained from Pseudanabaena biceps PCC 7429 (UniProt Accession L8N1T0), Vibrio caribbeanicus ATCC BAA-2122 (UniProt Accession E3BL63), Calothrix sp. PCC 6303 (UniProt Accession K9V437), and Rivularia sp. PCC 7116 (UniProt Accession K9RJJ3). Proteins are designated by the last three characters of the UniProt accession number (underlined). The E. coli BL21-Gold(DE3) cells are an all-purpose strain for high-level protein expression and easy induction and are obtained from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA)

General Methods.

Techniques for standard molecular biology manipulations were based on methods described elsewhere.14 DNA sequencing was performed in the DNA Sequencing Facility in the Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology (ICMB) at the University of Texas at Austin. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was carried out on an LCQ electrospray ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo, San Jose, CA) in the Proteomics Facility in the ICMB. Steady-state kinetic assays were performed on an Agilent 8453 diode-array spectrophotometer at 22 °C. Non-linear regression data analysis was performed using the program GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software. San Diego, CA). Protein concentrations were determined by the Waddell method.15 Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out on denaturing gels containing 12% polyacrylamide.16 The sequence alignments and secondary information were visualized using ESPript version 3.0.17

Growth and Expression 437 and JJ3.

The four lyophilized plasmids were resuspended in MilliQ water (50 μL) and DNA concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer 2000 (Thermo Scientific). Concentrations ranged from 40–100 ng/μL. An aliquot (5 μL) was used to transform electrocompetent E. coli BL-21 Gold(DE3) cells that were plated on Lysogeny broth (LB) agar plates supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/mL). These plates are designated LB/Kn. Transformants were collected and used to inoculate a 10-mL LB/Kn preculture (50 μg/mL) in a 50-mL conical tube. The cultures were grown at 37 °C with shaking (220 rpm) overnight. An aliquot of starter culture (1 mL) was used to inoculate a pre-warmed 1-L LB/Kn culture (50 μg/mL) in 2-L flasks. Cultures were grown at 37 °C (220 rpm) until the OD600 reading was ~0.5 (~4 h). The cultures were chilled on ice for ~15 min, induced with isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) (final concentration 0.75 mM), and expressed at 20 °C at 220 rpm for 20 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation (30 min, 11000 × g) with typical yields of 5–7 g cell pellet/L culture media. The pellets were resuspended in 50 mM Na2HPO4 buffer (10 mL, pH 8.3, buffer A) and flash frozen for future use. As needed, the resuspension was thawed, made 1 mM in phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and incubated on ice until chilled. The mixture (~15 mL) on ice, was disrupted by sonication (two cycles of 3-min each at 1-s pulses, 40% cycle duty/50% output) using a model W-385 Ultrasonic Processor Sonicator (Heat Systems-Ultrasonics, Inc., Newtown, CT). Cycles were separated by a 3-min interval. Cell debris was pelleted at 18,000 rpm (25,400 × g) at 4 °C for 45 min and removed. The lysate was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. It was found that two proteins (1T0 and L63) did not express solubly and they were not pursued further. Proteins 437 and JJ3 did express, and were purified and subjected to characterization as described below.

Purification of 437.

The clear lysate (~11 mL) from above (on ice) was made 1 M in (NH4)2SO4, where the ground (NH4)2SO4 was added in 3 portions to the stirring solution over a 30-min period. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation at 18,000 rpm (25,400 × g, 20 min) at 4°C. The supernatant was loaded onto a hand-packed Phenyl Sepharose column (20 mL bed volume) that had been previously equilibrated in buffer A made 1 M in (NH4)2SO4 (buffer B). The column was washed with 3 column volumes of buffer B, and the retained proteins were eluted using a linear gradient (buffer B to buffer A, total volume of 80 mL) followed by a final wash of deionized water (2 × 20 mL). Fractions (~1 mL) were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The target protein began eluting at ~15 mM (NH4)2SO4 and through the deionized water wash. Fractions containing the target protein with the fewest contaminants were pooled (~20 mL) and made up to ~40 mL in volume using buffer A. The resulting solution was concentrated to ~15 mL using a 250-mL Amicon Stirred Cell equipped with a 5,000 Da cutoff membrane filter.

The concentrate was applied to a hand-packed DEAE Sephadex column (~ 20 mL bed volume), which had been pre-equilibrated with buffer A, and washed with 3 column volumes of buffer A (3 × 20 mL). The retained protein was eluted with a linear gradient (buffer A to buffer A made 2 M in NaCl, total volume of 80 mL). Fractions (~1 mL) were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The target protein began eluting at ~650 mM NaCl. Fractions containing target protein with the fewest contaminants were pooled and concentrated (~15 mL to ~0.5 mL) using a 250-mL Amicon Stirred Cell equipped with a 5,000 kDa cutoff membrane filter.

The concentrate was loaded onto a hand-packed Sephadex G-75 column (~40 mL bed volume), which had been pre-equilibrated with buffer A. Fractions (~0.75 mL) were collected, and the target protein began eluting after ~15 mL (at room temperature). Fractions containing near-homogeneous protein (as determined by SDS-PAGE) were pooled and concentrated to ~4 mL (using a 50-mL Amicon Stirred Cell equipped with a 3,000 Da cutoff membrane filter). The final yield was 2 mL of protein (7 mg/mL) after concentration by a 0.5 mL Amicon Microcentrifuge Spin Column fit with a 3,000 Da cutoff membrane filter. Aliquots (50 μL) were flash frozen and stored at −80 °C for kinetic and crystallographic studies.

Purification of JJ3.

After sonication and centrifugation (above), the lysate (~11 mL) was applied to a hand-packed DEAE Sephadex column (~20 mL bed volume), which had been previously equilibrated with buffer A, and washed with 3 column volumes of buffer A (3 × 20 mL). The protein eluted in the initial wash. The wash (~60 mL) was concentrated to ~15 mL using a 250-mL Amicon stirred cell equipped with a 5,000 Da cutoff membrane. While on ice, the sample was made in 1 M in (NH4)2SO4, where the ground (NH4)2SO4 was added in three portions over a 30-min period. No obvious precipitate was observed. The sample was loaded onto a hand-packed Phenyl-Sepharose column (~20 mL bed volume) previously equilibrated in buffer B [buffer A made 1 M in (NH4)2SO4]. The column was washed with 3 column volumes of buffer B (3 × 20 mL). The retained protein was then eluted along a linear gradient from buffer B to buffer A (total volume 80 mL) followed by a final wash with deionized water (2 × 20 mL). Fractions (~1 mL) were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The target protein began eluting at ~200 mM (NH4)2SO4 through the deionized water wash. Fractions containing near-homogeneous protein (as determined by SDS-PAGE) were pooled and concentrated to ~0.6 mL (using a 50-mL Amicon Stirred Cell equipped with a 3,000 Da cutoff membrane). The resulting concentrate was desalted into buffer A using two PD-10 Sephadex columns previously equilibrated in buffer A, and the target protein was eluted using buffer A. Fractions (~ 0.3 mL) were collected, and those containing protein were pooled and concentrated using a 0.5 mL Amicon Microcentrifuge Spin Column equipped with a 3,000 Da cutoff membrane. The final yield was ~1 mL of protein (5 mg/mL). Aliquots (50 μL) were flash frozen and stored at −80°C for kinetic and crystallographic studies.

Inactivation of 437 and JJ3 by 3-Bromopropiolate (3-BP).

The inactivation protocols were adapted from techniques described elsewhere.7,18 Accordingly, a stock solution of 3-BP (3 mg/mL, 20.3 μM) was made up in 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer, pH 8, immediately before being incubated with protein. In a glass test tube, aliquots of 3-BP (7 μL) and protein (95 μL) from a stock solution of 437 or JJ3 (10.5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL, respectively) were combined at 2.1 molar equivalents (calculated by monomer molecular mass) and incubated at 5°C for 20 h. Subsequently, the individual solutions were exchanged into 10 mM (NH4)HCO3 using a PD-10 Sephadex column.19 An aliquot (50 μL) of each eluent (~900 μL) was submitted for mass spectral analysis in order to confirm labeling of the protein. For 437, a second aliquot (50 μL) of the eluent was prepared according to the endoproteinase Glu-C from Streptococcus aureus V8 digestion protocol (see below) and submitted for mass spectral analysis in order to determine the site of modification. (JJ3 was not subjected to proteolytic digest.) The remaining 800 μL of eluent was concentrated using a 3,000 Da Amicon Microcentrifuge Spin Column to ~300 μL. The concentrate was then exchanged into 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, using a PD-10 Sephadex column, concentrated to 10 mg/mL using the 3,000 Da Amicon Microcentrifuge Spin Columns, and subjected to crystallographic analysis.

Proteolytic Digestion and Mass Spectrometric Analysis.

Aliquots (50 μL) of a control and inactivated sample (~1 mg/mL) were lyophilized to a powder (~1 h) using a Savant SpeedVac centrifuge (model SPD121P). Both proteins were treated with sequencing grade endoproteinase Glu-C from S. aureus V8 (protease V8) using a modification of a literature procedure.20 Accordingly, the samples were resuspended in 6M guanidine HCl (3 μL) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. A portion (50 μg) of protease V8 was resuspended in 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer, pH 8 (20 μL). The volume was brought up to 45 μL in 10 mM (NH4)HCO3 buffer (pH 8) and 5 μL of protease V8 solution was added to each sample. The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. An aliquot (20 μL) of each sample was desalted and submitted for liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis using a Dionex LC and Orbitrap Fusion 1 mass spectrometer with a 30 min run time. The data were processed using Proteome Discover (PD) 2.2 and the proteome software Scaffold 5. The remaining 30 μL was flash frozen and stored at −80 °C.

Steady-State Kinetics.

Tautomerization activity was examined with 2-hydroxymuconate (2-HM) and phenylenolpyruvate (PP) (see Scheme 3), as described elsewhere.21,22 Briefly, assays using 2-HM and PP were carried out in 10 mM Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 8.3) at 22 °C in quartz cuvettes with pathlengths of 1 cm or 2 mm, respectively. Stock solutions of 2-HM (0.8−58 mM) and PP (8−116 mM) were prepared by dissolving the appropriate amount of the crystalline free acids in absolute ethanol. For 2-HM, substrate concentrations ranged from 5–75 μM and for PP they ranged from 125–1075 μM. A stock solution of 437 was diluted 5-fold into 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer (final pH of 8.3), for assays using 2-HM (0.0098 mg/mL and final concentration of 0.654 μM) and 10-fold for assays using PP (0.0082 mg/mL and final concentration of 0.549 μM). A stock solution of JJ3 was diluted 5-fold into 100 mM Na2HPO4 buffer (final pH of 8.3) for assays using 2-HM (0.0069 mg/mL and final concentration of 0.485 μM) and 10-fold for assays using PP (0.012 mg/mL and final concentration of 0.826 μM). The enol−keto tautomerization of 2-HM was monitored by following the decay of the enol form at 296 nm (ε = 22,000 M−1cm−1). The enol−keto tautomerization of PP was monitored by following the decay of the enol form at 305 nm (ε = 6,110 M−1cm−1). Initial rates were determined, plotted against the substrate concentration, and fit to the Michaelis-Menten and Lineweaver-Burk equations using GraphPad Prism 9 (Figures S1A,B and S2A,B).

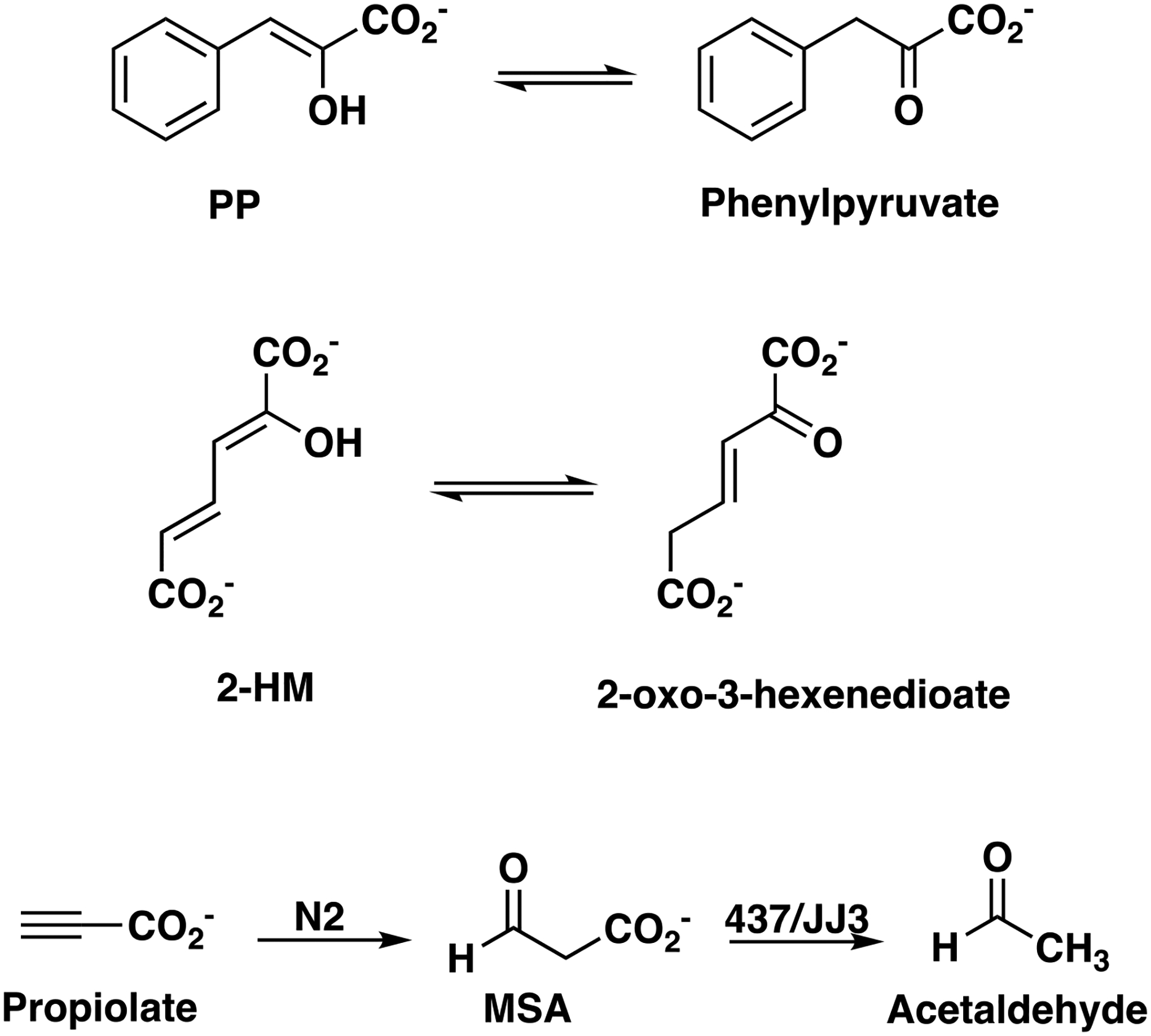

Scheme 3.

Enzyme-catalyzed Tautomerization and Decarboxylation Reactions.

MSAD activity was determined using malonate semialdehyde (MSA) as substrate at 22 °C in 10 mM Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 8.3) in a 1 cm quartz cuvette following a protocol described elsewhere.24 MSA can be generated from propiolate using the enzyme designated N2 (see Scheme 3).13 N2 is from Gammaproteobacteria bacterium SG8_31 (UniProt accession A0A0S8FF56) and is in the 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase (4-OT) subgroup, as described elsewhere.13 Accordingly, N2 (410 μL of 6.4 mg/mL) was added to propiolic acid to make a final solution of 1 mL (21 mg/mL, 300 mM) in 100 mM dibasic Na2HPO4 buffer made pH 8 with 1M NaOH. The mixture was incubated at 22 °C until the conversion of propiolate to MSA was complete (~30 min). This reaction was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy and determined to be complete when the spectrum from 200–400 nm remained unchanged. This stock solution was used for substrate concentrations, 1.5–6 mM, and a 10-fold dilution (made in 100 mM Na2HPO4, pH 8) was used for substrate concentrations, 0.3–0.9 mM. A 15 mg/mL (22.6 mM) stock solution of NAD+ and a 16.1 mg/mL (0.285 mM) stock solution of aldehyde dehydrogenase from Baker’s yeast were made in 100 mM Na2HPO4, pH 8.2 (as separate solutions). The final concentrations are 452 μM and 5.7 μM, respectively. Solutions of 437 (0.098 mg/mL, final concentration of 6.54 μM) and JJ3 (0.069 mg/mL, final concentration of 4.9 μM) were used in this assay. In a 1 cm quartz cuvette, the reactions were monitored for 5 min (10 s intervals) by following the increase at 340 nm due to the production of NADH (ε = 6,220 M−1cm−1). Initial rates were determined, the non-enzymatic rates were subtracted from these rates, the corrected rates were plotted against substrate concentrations, and fit to the Michaelis-Menten and Lineweaver-Burk equations using GraphPad Prism 9 (Figures S1C and S2C). The kinetic parameters are based on the monomer molecular mass (437: 14,975 Da; JJ3: 14,215 Da).

1H NMR Analysis of the 437- and JJ3-catalyzed Tautomerization of 2-Hydroxymuconate.

The 1H NMR protocol for monitoring the reactions of 437 and JJ3 with 2-hydroxymuconate followed that described elsewhere, as modified below.13 Accordingly, an amount of 2-HM (1.2 mg) in 30 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DMSO-d6) was added to 20 mM Na3PO4 buffer (final total volume of 600 μL). The final pH of the solution was ~8.0. Subsequently, an aliquot (30 μL) of 437 (6.8 mg/mL) or JJ3 (6.1 mg/mL) was added to the mixture to initiate the experiment. A similar experiment was set up in the absence of enzyme. Product formation was monitored using a Bruker AVANCE III 500 MHz spectrometer (Billerica, MA) for 26 min. The chemical shifts for the three isomers (structures are shown later in the paper) are reported elsewhere.11 The approximate amount of product in the mixtures was determined by integration, as described previously.24 The signals integrated were as follows: 2-HM, 7.13 ppm (dd, 1H, C4); 2-oxo-3-hexenedioate, 3.06 ppm (d, 2H, C5); and 2-oxo-4-hexenedioate, 3.47 ppm (d, 2H, C3). NMR signals were analyzed using the software program SpinWorks 3.1.6 (Copyright © 2009 Kirk Marat, University of Manitoba).

Crystallization.

Initial crystallization conditions for the apo 437 and 437 covalently modified by 3-BP were identified using sparse-matrix screening with a Phoenix crystallization robotic system (Art Robbins Instruments). The crystal conditions were then optimized using the sitting drop vapor diffusion technique at room temperature. The diffracting crystals were obtained using 24-well crystallization plates (Hampton Research) where a 1 μL aliquot of protein (~10 mg/mL) was mixed with 1 μL of mother liquor. Crystals of the apo 437 were grown in conditions containing 10–33% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 550 monomethyl ether, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.6), 0.2 M calcium acetate. The crystal belongs to the space group P212121 with a unit cell a = 51.0 Å, b = 86.9 Å, c = 146.4Å, α = β = γ = 90°. The modified 437 crystallized in 16–31% (v/v) PEG 6000 and 0.1M HEPES buffer (pH 6.5–7.5). Crystals grew to maturity within 7 days and belong to the orthorhombic space group P212121 with the unit cell dimension a = 38.5 Å, b = 51.6 Å, c = 158.2 Å, α = β = γ = 90°. Crystals were cryoprotected with mother liquor supplemented with 30% glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen until synchrotron data collection.

Data collection, Processing, Structure Determination and Refinement.

Diffraction data were collected from the Advanced Photon Source (APS) beamline 23-ID-B (Argonne National Laboratories). The data sets were indexed, integrated, and scaled using HKL-3000.25 The structures were determined by molecular replacement (MR) using Phaser-MR from the PHENIX suite of programs.26 The search model used in molecular replacement is a monomer of fused 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase1 with all side chains changed to alanine [Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 4LKB]. Structure refinement was carried out using Phenix Refine. To build a model of 437 with the 3-oxopropanoate adduct (derived from 3-BP) the location of the ligand was identified by the Fo-Fc omit map, which showed covalent bond formation and the position of the 3-oxo moiety of the 3-oxopropanoate adduct. The density for the rest of the ligand is weak so Phenix.LigandFit was used to build a virtual model for possible binding modes. The virtual model was then optimized to ensure that there were no steric clashes. The data collection and refinement statistics for the apo 437 structure is summarized in Table 1. The final model was evaluated by ProCheck and Molprobity.27 Figures were prepared using PyMol (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics system, Version 1.8 Schrodinger, LLC).28

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics for Apo 437

| Data collection | |

| space group | P21 21 21 |

| cell dimensions | |

| a,b,c (Å) | 51.0, 86.9, 146.4 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| resolution (Å) | 48.13–2.35 (2.44–2.35)a |

| wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 |

| R sym | 0.069 (0.759)a |

| R pim | 0.031 (0.378)a |

| CC1/2 | 0.997 (0.801)b |

| I/σ | 10.6 (1.6)a |

| completeness (%) | 99.47 (97.02)a |

| redundancy | 5.6 (4.9)a |

| Refinement | |

| resolution (Å) | 48.13–2.35 (2.44–2.35)a |

| no. of reflections | 27629 (2643)a |

| R work | 0.2169 (0.2583)a |

| Rfree c | 0.2756 (0.3121)a |

| no. of atoms | 5913 |

| protein | 5785 |

| water | 128 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| protein | 27.1 |

| water | 28.4 |

| r.m.s. deviations | |

| bond lengths(Å) | 0.003 |

| bond angles (°) | 0.58 |

| Ramachandran plot | (%) |

| favored | 99.43 |

| allowed | 0.57 |

| outliers | 0.00 |

| MolProbity scored | 1.23/(100th percentile)e |

Values for the corresponding parameters in the outermost shell are in parentheses.

CC1/2 is the Pearson correlation coefficient for a random half of the data; the two numbers represent the lowest and highest resolution shell, respectively.

Rfree is the Rmodel calculated for 10% of the reflections randomly selected and omitted from refinement.

MolProbity score is calculated by combining the clash score with the rotamer and Ramachandran percentage and scaled on the basis of X-ray resolution.

The percentage is calculated with 100th percentile as the best and 0th percentile as the worst among structures of comparable resolution.

Construction of the SSN and Multisequence Alignment.

In the TSF SSN, the MSAD-like subgroup consists of 143 nodes representing 2050 non-redundant sequences in a 50% representative network.1 After manual curation to remove sequences greater than 160 amino acids, an additional 397 sequences were added to the MSAD-like subgroup in 2017, making a total of 2447 sequences. The UniProt codes for the updated MSAD-like subgroup were submitted to Enzyme-Function Initiative-Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST) server to generate a Level 2 (100% identity network) (Figure S3).29 The different levels (Levels 1, 2, and 3) refer to a hierarchical classification scheme where subgroups and sub-subgroups are defined by sequence similarity. An increase from Level 1 to Level 2 (for example) means that sequences are grouped together at higher stringency (the minimum edge alignment score increases).1,29 The Level 2 network contained 1964 nodes and was visualized with a minimum edge alignment score of 40 in the organic layout in Cytoscape (Version 3.7.1).30 In the Level 2 network, the Pro1 nodes (colored blue) dominate the network (Figure S3). However, there is a distinct cluster of mostly non-Pro1 nodes (boxed) consisting of 353 sequences. Manual curation of these sequences for those with a correctly annotated start codon in-frame with a ribosome binding site1, reduced the number of sequences to 271 where 4 sequences have Pro1 and 267 sequences do not have Pro1. The UniProt codes for the 271 sequences were submitted to the EFI-EST server to generate the Level 3 100% identity network. An edge alignment score of 48 was applied, and the nodes were organized in Cytoscape,30 as described above. Clustal Omega was used to generate a multisequence alignment of the sequences with edges to 437.31

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression and Purification of 437 and JJ3.

437 and JJ3 were overproduced in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified to near homogeneity. The typical yield was ~13 mg for 437 (2 mL at 6.5 mg/mL) and ~5 mg for JJ3 (1 mL at 5 mg/mL) per L of culture. MS analysis of the purified 437 showed a single major signal corresponding to a monoisotopic mass of 14,975 Da (calc. 14,977 Da; calc with Met1 15,108 Da) in the reconstructed mass spectrum (Figure S4A). MS of the purified JJ3 showed a single major signal corresponding to a monoisotopic mass of 14,215 Da (calc. 14,216 Da; calc with Met1 14,347 Da) in the reconstructed mass spectrum (Figure S4C). The smaller signals (14,314 Da and 14,593 Da) are unknown impurities. The mass difference of ~132 Da between the calculated (with Met1) and the observed mass indicates that the translation-initiating methionine was post-translationally removed, resulting in the mature and catalytically active proteins (127 amino acids for 437 and 121 amino acids for JJ3) with Pro1.32

Kinetic Analysis using Phenylenolpyruvate, 2-Hydroxymuconate, and Malonate Semialdehyde.

437 and JJ3 convert PP, 2-HM, and MSA to their respective products (Scheme 3).

MSA was generated by the N2-catalyzed hydration of propiolate (Scheme 3), as previously described.13 The kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

| 437 | JJ3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

| PP | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 1200 ± 300 | 3600 ± 1050 | 9.0 ± 3.4 | 3200 ± 1500 | 2800 ± 1700 |

| 2-HM | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 34 ± 12 | 4700 ± 1800 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 24 ± 10 | 9000 ± 4000 |

| MSA | (2.7 ± 0.15) ×10−3 | 900 ± 150 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | (4.0 ± 0.59) ×10−3 | 4000 ± 1000 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

The kinetic parameters were determined by the assays described in the text.

Both 437 and JJ3 have nearly comparable tautomerase activities using PP or 2-HM with kcat/Km values of ~103 M−1s−1, although 2-HM might be a slightly better substrate. It was not possible to saturate either enzyme with PP so that the Vmax (and by extension, the kcat) can only be viewed as estimates (with significant error). Higher substrate concentrations result in values that are outside the accuracy of the spectrophotometer (> 1.5 absorbance units).

In other work, we have used PP and 2-HM to gauge tautomerase activity.1,11,13 4-OT subgroup members use both 2-HM and PP as substrates, but those in cis-3-chloroacrylic acid dehalogenase (cis-CaaD) subgroup can only process PP.1 Analysis of the 4-OT and cis-CaaD active sites shows that Pro1 is positioned between two arginine groups (positionally comparable to Arg-11 and Arg-39 in 4-OT) such that di- and monocarboxylate substrates can be processed by 4-OT and related homologues.1,13 However, in cis-CaaD, the two arginine groups (Arg-70 and Arg-73) are to one side of Pro-1 so that 2-HM is not converted to product, but PP is.1 These observations suggest that the active sites of 437 and JJ3 could be more like 4-OT (which processes both mono- and dicarboxylated compounds) than cis-CaaD with regard to the positioning of Pro1 and the two active site groups that bind the carboxylate groups. The active site topographies of 437 and JJ3 are under investigation.

The MSA activities of 437 and JJ3 are poor (kcat/Km values of 1–3.3 M−1s−1), but higher than the non-enzymatic activity (at all substrate concentrations). Clearly, MSA is not the biological substrate for these enzymes. Superimposition of the active sites of 437 and Pp MSAD shows significant differences, consistent with the absence of robust MSA activity.

NMR Analysis.

The MSAD activities of 437 and JJ3 were too slow to be followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. The hydration of propiolate (by 437 or JJ3) was also examined by 1H NMR spectroscopy, but product was not detected (after an 18-h incubation period). In order to verify product formation for 2HM and that product formation occurred at a faster rate in the presence of enzyme, the reactions were followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Analysis of the spectra clearly show that the enzymatic ketonization of 2-HM to 2-oxo-3-hexenedioate is faster than the non-enzymatic reaction. After 26 min, all three isomers are present (shown below), but 2-oxo-3-hexenedioate predominates in the mixture with 437 (~65.2%) and JJ3 (~69.3%) compared with non-enzymatic (~10.3%).

Modification of 437 and JJ3 by 3-Bromopropiolate.

437 and JJ3 were incubated with 3-BP at pH 8.0, as described in the experimental section. After incubation for 20 h, the enzymes were recovered and analyzed by MS. For 437, the major signal was found at 15,060 Da, corresponding to an adduct with a mass of 85 Da (Figure S4B). As shown in Figure S4A, the unlabeled 437 has a mass of 14,975 Da. For JJ3, the major signal was found at 14,301 Da (corresponding to an adduct with a mass of 86 Da), with smaller signals at 14,257 Da, 14,345 Da, and 14,680 Da (Figure S4D). As shown in Figure S4C, the unlabeled JJ3 has a mass of 14,215 Da. The signal at 14,257 Da corresponds to a loss of 44 Da, which likely results from decarboxylation of the adduct on JJ3 (under the conditions of the mass spectrometer).13 The signal at 14680 Da corresponds to the covalently modified impurity (14,593 Da) with a mass difference of 87 Da. The identities of the signals at 14,345 Da are not known. For both 437 and JJ3, the mass of the adduct corresponds to the attachment of a 3-oxopropanoate moiety.

Protease V8 digestion and MS Analysis.

After it was confirmed that a single site on protein was modified, the 3-BP treated protein was digested (along with a control sample) with protease V-8 and the resulting mixture was analyzed by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). At pH 8.0, protease V8 cleaves at the carboxy side of aspartic and glutamic acid residues. Examination of the 127-amino acid sequence shows 11 glutamates and 7 aspartates. Fortunately, the amino-terminal sequence (PQLKIYGLRE due to cleavage at Glu10) could be detected and analysis of the series of b and y ions showed that the covalent modification is localized to Pro1 (see Figure Legend in Figure S5).18,19 In the control sample, the same peptide (Pro1 to Glu10) did not show modification. The MS of the control sample showed a signal at 1,216.7 Da (calc. 1216) and the MS of the 3-BP-treated sample showed a signal at 1,302.7 Da (calc. 1302). The mass difference corresponds to 86 Da, which is the mass of the adduct.

Crystal Structure of Apo 437.

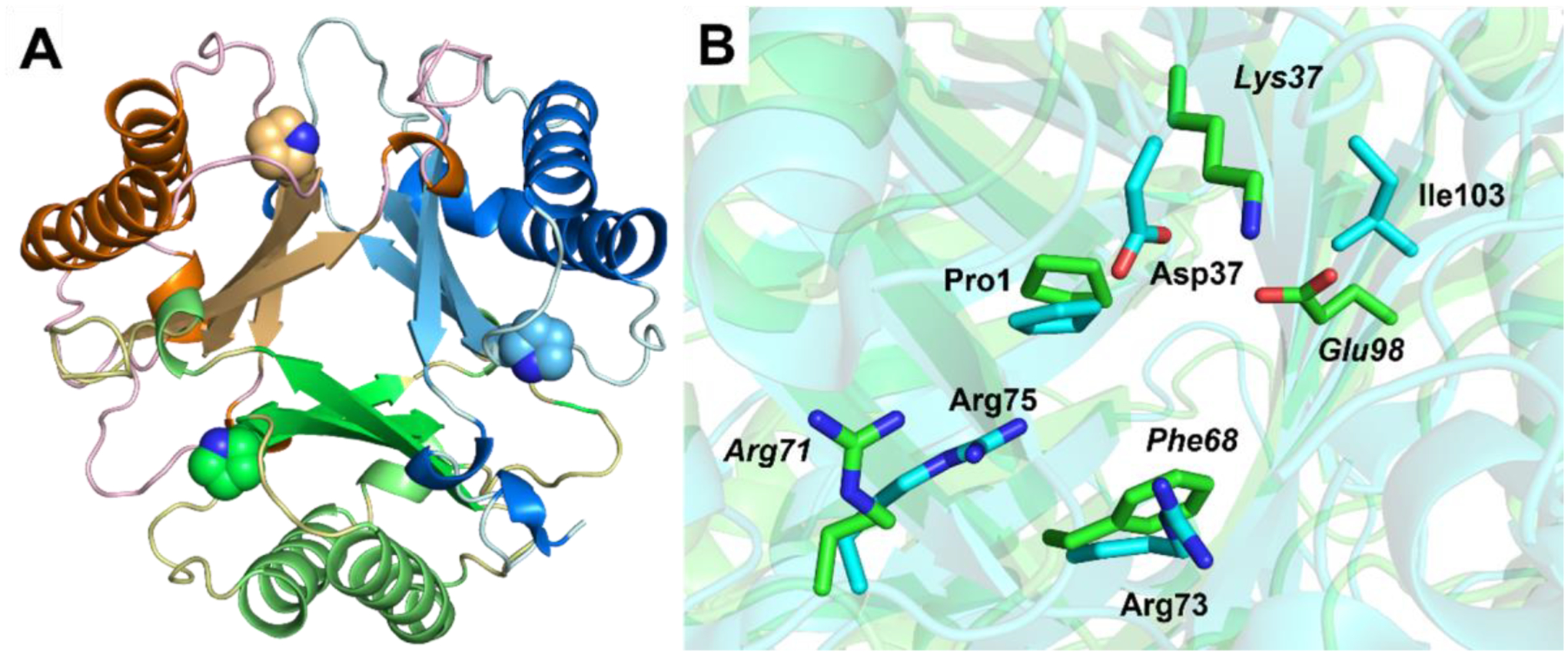

The apo 437 crystals are highly mosaic and diffract to 2.35 Å resolution and are indexed as space group of P212121 (Table 1). The final model for the 437 contains six molecules per asymmetric unit, forming two trimers. In each trimer, three monomers arrange in a P3 symmetry with a rotation of 120 degrees. The main chain fold of 437 is identical to known MSAD family members with an internal symmetry of the first and second half of the protein that is related to the consecutively fused β-α-β building blocks, which is the hallmark of the TSF (Figure 1A).1,33 The β strands comprise the core of the trimer with α helixes surrounding it at the peripheral (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of 437 and superimposition of active sites of Pp MSAD and 437. (A) The overall structure of the 437 trimer shown in ribbon diagram. Each monomer consists of a consecutively fused β–α–β units. The Pro1 is shown as space filling model for each monomer of the trimer. (B) Superimposition of the active sites of Pp MSAD (PDB code 2AAG) and 437. The backbones of the proteins are shown in ribbon diagram where the Pp MSAD is colored with cyan and 437 is coded with green for the carbon atoms. The side chains of key residues are shown in sticks with the residue numbers labeled next to the side chains in which Pp MSAD is labeled in normal font and 437 is labeled in italics.

Inspection of the area around Pro1, presumably the active site region, shows little conservation with known TSF members other than Pro1 (Figure 1B). In Pp MSAD, Asp37 has two roles: it raises the pKa of Pro-1 to 9.26 and activates a water molecule for the Michael addition to acetylene compounds.8,9,10 In 437, it is replaced by a Lys37. The proximity of the positively charged Lys37 to Pro1 may lower the pKa of the prolyl nitrogen so that it can function as a base in the ketonization of PP and 2-HM. The Arg73 and Arg75 pair that interact with the carboxylate group of MSA is also missing. A hydrophobic residue, Phe68, replaces the sidechain position of Arg73. Arg71, which is still present, adopts a different rotameric state so that the side chain extends outwards away from the active site.

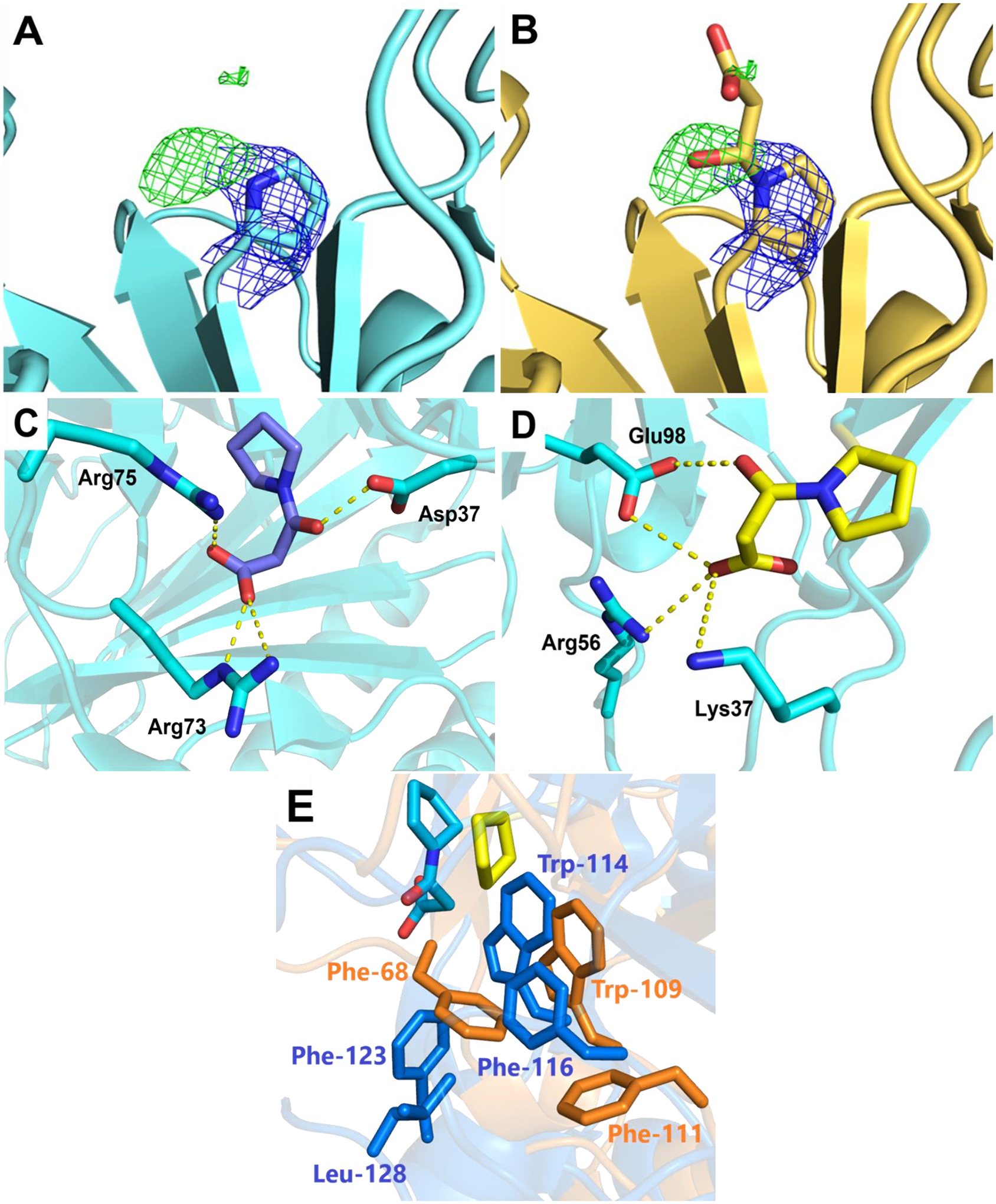

Model of the 3-Oxopropanoate Adduct on Pro1.

To identify potential residues participating in binding and turnover in 437, the protein was treated with 3-BP, and the covalently modified enzyme was crystallized. 3-BP has been a powerful tool for the identification of active site ligands in other TSF members.7,8,10,18 However, when the structure is solved using apo 437 as the search model, the only positive density in the Fo-Fc omit map at the active site is extended out from the prolyl nitrogen of Pro1 (Figure 2A,B). The new positive density compared with apo 437 is consistent with the mass spectral result that a 3-oxopropanoate adduct is formed from the incubation of 3-BP with Pro1. Although there is strong positive density indicating the position of the carbonyl group (of the 3-oxopropanoate adduct), the rest of the ligand exhibits little density (Figure 2A). The partial density of the adduct was used to guide modeling of the ligand into the active site using Phenix.LigandFit (Figure 2B). The model provides an important clue for the possible orientation of the ligand, yet it shouldn’t be considered an experimental structure for 437 adduct due to the relatively weak density for the carboxylate group of the ligand.

Figure 2.

Active sites of 437 and Pp MSAD. (A) 2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc maps of 437 treated with 3-BP. The omit map of Fo-Fc contoured to 3 σ suggests adduct formation. The 2Fo-Fc map is contoured to 1.5 σ with Pro1 shown in sticks. (B) Modeling of 3-oxopropanoate adduct of 437. The ligand is fit into the maps using Phenix.LigandFit. (C) The interactions of the modified Pp MSAD (PDB code 2AAL). The 3-oxopropanoate adduct of Pro1 is colored violet at the carbon atoms and the Pp MSAD is colored cyan. (D) The potential interactions of 437 with the modeled 3-oxopropanoate adduct shown in yellow at the carbon atoms. (E) The residues making up the hydrophobic walls of Pp MSAD and 437 at the active sites. The hydrophobic wall is partially conserved with Pp MSAD shown in gold and 437 in blue. The 3-oxopropanoate adduct on Pro1 in Pp MSAD is shown in sticks colored in cyan at the carbon atoms. The Pro1 side chain of 437 is colored in yellow.

Since the positive density specifies the location of the carbonyl group with the planar configuration of 3-oxopropanoate, the energy minimized model displays an orientation with the carboxylate group extending into a region with positive residues, potentially forming salt bridges with Lys37 and Arg56 (Figures 2C,D). Interestingly, the carboxylate groups of both the Pp MSAD/3-BP structure and our 437/3-BP model are extending into positive residue patches, but the orientation flips to the opposite direction due to the different location of these positive residues (Figures 2C,D). The carbonyl group of the adduct (3-oxopropanoate) in the model forms a hydrogen bond with Glu98 (Figure 2D), reminiscent of the Asp37 interaction found in modified Pp MSAD structure (Figure 2C).8 The hydrophobic wall in Pp MSAD is only partially conserved in 437 (Figure 2E). While Trp114 and Phe116 are conserved (corresponding to Trp109 and Phe111 in 437), the other side of the active site, which is all exclusively hydrophobic residues, are much more hydrophilic to include the Lys and Arg residues potentially binding to carboxylate of the ligand. Notably, even though Phe123 is not conserved in 437 (the comparable residue is Asp117), the hydrophobicity to cover the Pro-1 is still maintained with Phe68 coming from the opposite direction (Figure 2E).

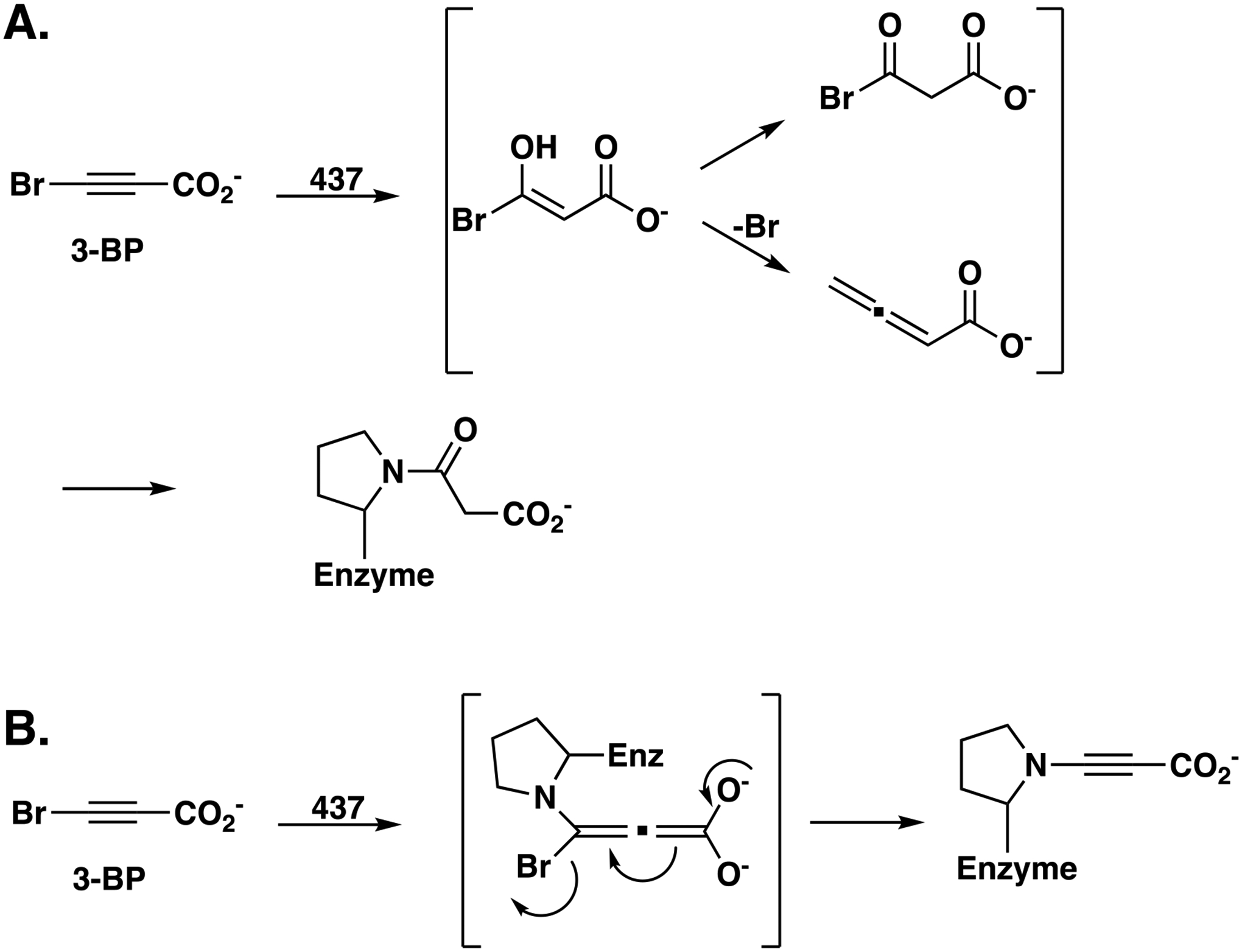

Inactivation of 437 and JJ3 by 3-Bromopropiolate.

Based on our previous work with 3-BP and the inactivation of TSF members by it7,8,10,18, and the crystallographic and labeling analysis presented above, two mechanisms can be proposed that are consistent with the formation of the 3-oxopropanoate adduct on Pro1 (Scheme 4A,B).

Scheme 4.

Proposed Mechanisms for Inactivation of 437 by 3-Bromopropiolate. A) Mechanism-based route by hydration of 3-bromopropiolate. B) Michael-type route initiated by nucleophilic attack of Pro1 at C3 of Inactivation of 437 by 3-Bromopropiolate. A) Mechanism-based route by hydration of 3-bromopropiolate.

In mechanism A, modification of Pro1 can occur by a mechanism-based route where 3-BP undergoes 437-catalyzed hydration and rearrangement to an acyl halide or an allene (shown in brackets). Acylation (or alkylation) of Pro1 by either species would generate the final adduct. The interaction of Lys37 and Arg56 with the carboxylate group (as suggested by the model in Figure 2D) could make the C3 position of 3-BP more susceptible to nucleophilic attack by polarizing the α,β-unsaturated acid along with the activating effect of the halogen substituent. In view of the observations that there is not an ordered water molecule near Glu98 and there is no evidence for the hydration of propiolate acid, this mechanism seems less likely.

In mechanism B, a nucleophilic Pro1 could attack the C-3 position of 3-BP in a Michael-type reaction. The conjugate addition to an α,β-unsaturated acid is not normally favorable, but again, Lys37 and Arg56 could interact with the carboxylate group and draw electron density away from the C-3 position, making it more susceptible to nucleophilic attack. Rearrangement of the intermediate to reform the triple bond would expel the bromide and leave a propargyl moiety on Pro1.

The mass spectral analysis shows that the adduct on Pro1 has a molecular mass of 85/86 Da, which is consistent with a 3-oxopropanoate moiety. A rearrangement, as shown in Scheme 5, could produce the 3-oxopropanoate adduct.

Scheme 5.

Inactivation of 437 by 3-Bromopropiolate.

The propargyl moiety could rearrange to an electrophilic allene, which would readily be attacked by water. Ketonization of the enol produces the observed 3-oxopropanoate adduct moiety. Other than the crystallographic observations and previous work, there is no evidence to support this mechanism.

Mechanisms for Tautomerization and Decarboxylation.

Kinetic analysis of 437 shows that both 2-HM and PP are converted to their respective products with comparable kcat/Km values. An extensive analysis of the active sites for the 4-OT and 4-OT subgroup members shows that Pro1 is positioned between two arginine residues comparable to Arg-11 and Arg-39 in 4-OT. Arg-11 has a role in binding and catalysis: it binds C6 and draws electron density toward C5 to facilitate protonation at C5.1,3 In cis-CaaD, the two arginine groups (Arg-70 and Arg-73) are to one side of Pro-1 so that 2-HM is not converted to product, but PP is. The comparable kcat/Km values for PP and 2-HM suggest that the active sites of 437 and JJ3 are more 4-OT-like. Examination of the active site region in 437 show three residues capable of binding carboxylate groups (Lys37, Arg56, and Arg71) along with Pro1 to function as a base. Lys37 sits on top of Pro1 and proximity of the positively charged Lys37 to Pro1 might lower the pKa of the Pro1 so it can function as a base. Without additional study, it is not possible to determine if any of the three residues is involved in the binding of the carboxylate groups and how they “sit” with respect to Pro1 These studies are underway.

The active sites of 437 and JJ4 have little in common with Pp MSAD or FG41 MSAD, other than Pro1, so it’s not surprising that it has very little activity with MSA. Moreover, the biological reactions of 437 and JJ3 are not known. Without additional mechanistic and mutagenic work, it is not possible to formulate a mechanism for the decarboxylation reaction.

Bioinformatics and Sequence Analysis.

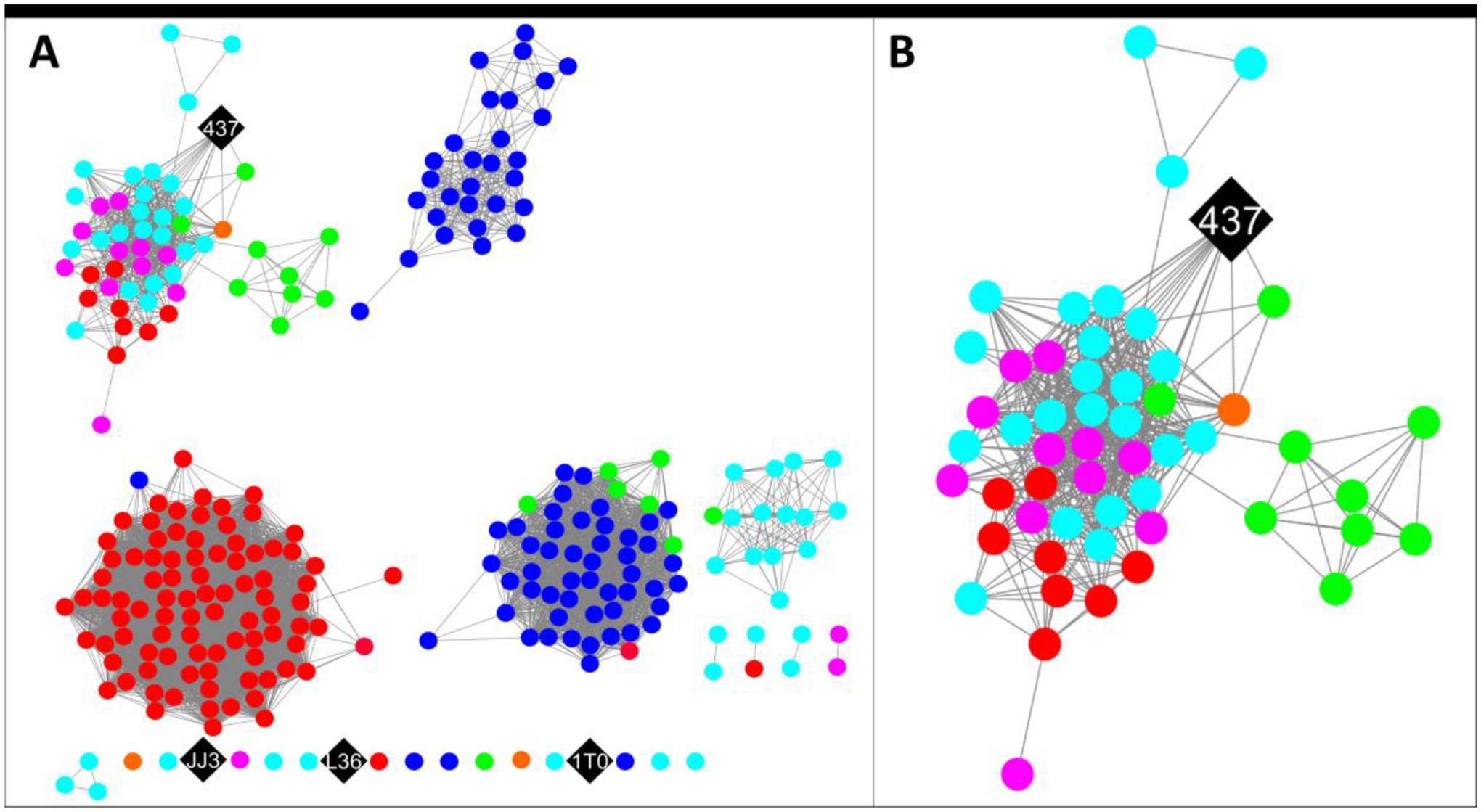

The sequences in the boxed region of the Level 2 SSN (Figure S3) were used to generate the Level 3 100% identity network (Figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

The level 3 SSN for the cluster of sequences shown in the box in the level 2 SSN (Figure S3). (A) The SSN with a minimum edge alignment score of 48 (sequence identity ~ 64%).29 The sequences are color coded by their amino termini as follows: Gly (magenta); Ala (cyan); Pro (black); Thr (orange); Ser (red); and Val (green). (B) An enlarged view of the sub-cluster containing 437 showing edges with the other nodes.

The 271 sequences in the network are color-coded according to the N-terminal group (see Figure Legend). The 4 diamond nodes (colored black) retain Pro1 and were examined in this study. Three are singletons (JJ3, 1T0, and L36). Proteins 1T0 and L36 did not express solubly and were not pursued after it was determined that they are singletons. JJ3 expressed and was characterized, but was later found to be a singleton with limited use.

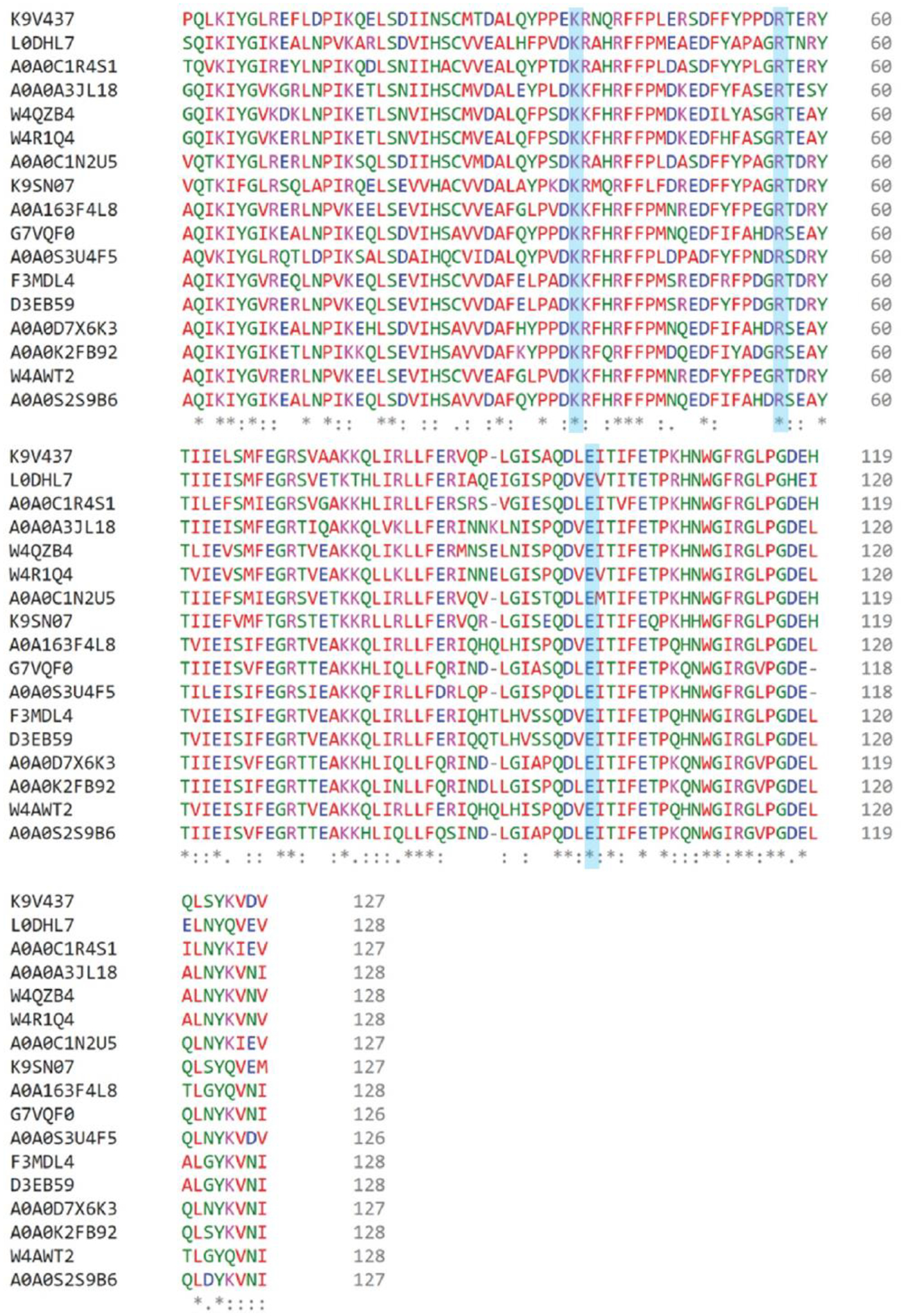

Protein 437 shares edges with 15 other nodes containing 16 sequences (Figure 3B) that do not have an amino terminal proline. The amino termini are Gly, Ala, Pro, Thr, Ser, and Val. The sequences in this cluster were subjected to a multisequence alignment shown in Figure 4. The residues identified in model of the 3-oxopropanoate adduct (Lys37, Arg56, Glu98) are conserved in all 16 sequences (highlighted in blue). This might reflect a similar mechanism for all once a substrate(s) is determined.

Figure 4.

Sequence alignment of 437 with 16 sequences listed by the UniProt Accession codes. 437 shares edges with the 15 nodes containing these sequences as shown in Figure 3B. The conserved active site residues (Lys37, Arg56, and Glu98) are highlighted in blue. Identical residues are indicated by a single * beneath the sequences. Residues that are similar with respect to hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity or charge are marked with . for lower similarity, and : to indicate higher similarity. Trp109 is identical in all 17 sequences and Phe68 and F111 are mostly conserved, as described in the text. The percent identity matrix performed by Clustal Omega calculated the percent identity of 437 to the 16 other connecting sequences to be between 54–68%. The multisequence alignment was obtained using Clustal Omega.31

In addition, the residues comprising the hydrophobic wall are conserved or mostly conserved (Figures 2E,4). Trp109 is found in all 17 sequences. Phe68 is found in all sequences except for 2 where it is replaced with an Ile. Phe111 is the “least” conserved and is only found in six sequences. In the other eleven sequences, it is replaced with an Ile. Ile and Phe are similar in hydrophobicity. This area of hydrophobicity could be involved in the decarboxylation of MSA since so little else is conserved between the sequences of the MSADs and this set of sequences.

More interestingly, Pro1 will not be involved in the mechanism because it is not present. As noted earlier and elsewhere, when proteins are expressed in E. coli, the removal of the initiating methionine correlates with the identity of the second amino acid.32 For Gly, Ala, Pro, Thr, Ser, and Val, the initiating Met is likely removed. This prediction is based on a study of sequences available in 1989.32 Our experience with Pro1 mutants of 4-OT, showed that for both the P1G (Pro1 is replaced by Gly) and P1A (Pro1 is replaced by Ala) mutants, Met1 was removed.34 However, replacing Pro with Val generated a mixture of M1P2V (45%, Met in position 1 and Pro2 is replaced with Val) and P1V (55%, Pro1 is replaced with Val), as assessed by mass spectral analysis.34 Mutations where Pro1 was replaced with Thr or Ser were not constructed.

For 12 of the 16 sequences, the Ala (9 sequences) or Gly (3 sequences) will be the N-terminal group because the initiating methionine is removed.34 For the encoded proteins, the amino terminal group can function as a catalytic residue, as we have seen with 4-OT mutants when Ala or Gly replaced Pro1. The same is also true when Val (2 sequences) is in the amino-terminal position although the enzyme will likely be a mixture of M1P2V and PIV.

The proteins encoded by an amino-terminal Ser (1 sequence) and Thr (1 sequence) present interesting cases. In both, the amino terminal group can function as a catalytic residue, as above. Alternatively, the N-terminal amino group could abstract a proton from the side chain hydroxyl group of Ser (or Thr) in a catalytic dyad to make a very nucleophilic hydroxy group as an oxyanion, as found in penicillin G acylase.35,36 These proteins might represent new mechanisms and chemistry in the TSF. All or some of the proteins encoded by the 16 sequences might not function as enzymes. The possibilities are currently under investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The protein mass spectrometry analysis was conducted in the Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology Protein and Metabolite Analysis Facility at the University of Texas at Austin. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM-129331 to C.P.W. and GM-104896 to Y.J.Z. and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-1334 to CPW).

ABBREVIATIONS

- APS

Advanced Photon Source

- 3-BP

3-bromopropiolate

- cis-CaaD

cis-3-chloroacrylic acid dehalogenase

- DEAE

diethylaminoethyl

- EFI-EST

Enzyme-Function Initiative-Enzyme Similarity Tool

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid

- 2-HM

2-hydroxymuconate

- FG41 MSAD

Coryneform bacterium strain FG41 malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase

- ICMB

Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside

- Kn

kanamycin

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid Chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry

- LB

Lysogeny broth

- MSA

malonate semialdehyde

- MSAD

malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase

- MR

molecular replacement

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- 4-OT

4-oxaolcrotonate tautomerase

- PP

phenylenolpyruvate

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PDB

protein data bank

- Pp MSAD

Pseudomonas pavonaceae 170 malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase

- SSN

sequence similarity network

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TSF

tautomerase superfamily

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/.

Michaelis-Menten Plots, Lineweaver-Burk Plots, Level 2 100% Identity SSN, mass spectra for 437, JJ3, and covalently modified 437, JJ3, and mass spectral analysis of the V8 digest of 437.

Accession Codes

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank: PDB entry 7TVK for the apo 437.

UniProt accession ID

437 from Calothrix sp. PCC 6303 (UniProt Accession K9V437)

JJ3 from Rivularia sp. PCC 7116 (UniProt Accession K9RJJ3).

REFERENCES

- 1.Davidson R, Baas B-J, Akiva E, Holliday G, Polacco BJ, LeVieux JA, Pullara CR, Zhang YJ, Whitman CP, and Babbitt PC (2018) A global view of structure-function relationships in the tautomerase superfamily. J. Biol. Chem 293, 2342–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murzin AG (1996) Structural classification of proteins: new superfamilies. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 6, 386–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poelarends GJ, Veetil VP, and Whitman CP (2008) The chemical versatility of the β-α-β fold: Catalytic promiscuity and divergent evolution in the tautomerase superfamily. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 65, 3606–3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stivers JT, Abeygunawardana C, Mildvan AS, Hajipour G, Whitman CP, and Chen LH (1996) Catalytic role of the amino-terminal proline in 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase: affinity labeling and heteronuclear NMR studies. Biochemistry 35, 803–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poelarends GJ, Johnson WH Jr., Murzin AG, and Whitman CP (2003) Mechanistic characterization of a bacterial malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase: identification of a new activity in the tautomerase superfamily. J. Biol. Chem 278, 48674–48683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poelarends GJ, Serrano H, Johnson WH Jr., Hoffman DW, and Whitman CP (2004) The hydratase activity of malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase: mechanistic and evolutionary implications. J. Am. Chem. Soc 126, 15658–15659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poelarends GJ, Serrano H, Johnson WH Jr., and Whitman CP (2005) Inactivation of malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase by 3-halopropiolates: evidence for hydratase activity. Biochemistry 44, 9375–9381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almrud JJ, Poelarends GJ, Johnson WH Jr., Serrano H, Hackert ML, and Whitman CP (2005) Crystal structures of the wild-type, P1A mutant, and inactivated malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase: a structural basis for the decarboxylase and hydratase activities. Biochemistry 44, 14818–14827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo Y, Serrano H, Poelarends GJ, Johnson WH Jr., Hackert ML, and Whitman CP (2013) Kinetic, mutational, and structural analysis of malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase from Coryneform bacterium strain FG41: mechanistic implications for the decarboxylase and hydratase activities. Biochemistry 52, 4830–4831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huddleston JP, Burks EA, and Whitman CP (2014) Identification and characterization of new family members in the tautomerase superfamily. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 564, 189–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitman CP, Aird BA, Gillespie WR, and Stolowich NJ (1991) Chemical and enzymatic ketonization of 2-hydroxymuconate, a conjugated enol. J. Am. Chem. Soc 113, 3154–3162. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersson K (1972) Additions to propiolic and halogen substituted propiolic acids. Chem. Scripta 2, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baas B-J, Medellin BP, LeVieux JA, Erwin K, Lancaster EB, Johnson WH Jr., Kaoud TS, Moreno RY, de Ruijter M, Babbitt PC, Zhang YJ, and Whitman CP (2021) Kinetic and structural analysis of two linkers in the tautomerase superfamily: analysis and implications. Biochemistry 60, 1776–1786.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, and Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waddell WJ (1956) A simple ultraviolet spectrophotometric method for the determination of protein. J. Lab. Clin. Med 48, 311–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli UK (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert X, and Gouet P (2014) Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucl. Acids Res 42 (W1), W320–W324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang SC, Johnson WH Jr., Czerwinski RM, and Whitman CP (2004) Reactions of 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase and YwhB with 3-halopropiolic acids: analysis and implications. Biochemistry 43, 748–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang SC, Person MD, Johnson WH Jr., and Whitman CP (2003) Reactions of trans-3-chloroacrylic acid dehalogenase with acetylene substrates: consequences of and evidence for a hydration reaction. Biochemistry 42, 8762–8773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houmard J, and Drapeau GR (1972) Staphylococcal protease: a proteolytic enzyme specific for glutamoyl bonds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 69, 3506–3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burks EA, Fleming CD, Mesecar AD, Whitman CP, and Pegan SD (2010) Kinetic and structural characterization of a heterohexamer 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase from Chloroflexus aurantiacus J-10-fl: implications for functional and structural diversity in the tautomerase superfamily. Biochemistry 49, 5016–5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burks EA, Yan W, Johnson WH Jr., Li W, Schroeder GK, Min C, Gerratana B, Zhang Y, and Whitman CP (2011) Kinetic, crystallographic, and mechanistic characterization of TomN: elucidation of a function for a 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase homologue in the tomaymycin biosynthetic pathway. Biochemistry 35, 7600–7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang SC, Johnson WH Jr., and Whitman CP (2003) The 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase- and YwhB-catalyzed hydration of 3E-haloacrylates: implications for the evolution of new enzymatic activities. J. Am. Chem. Soc 125, 14282–14283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poelarends GJ, Serrano H, Person MD, Johnson WH Jr., and Whitman CP (2008) Characterization of Cg10062 from Corynebacterium glutamicum: implications for the evolution of cis-3-chloroacrylic acid dehalogenase activity in the tautomerase superfamily. Biochemistry 47, 8139–8147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minor W, Cymborowski M,. Otwinowski Z, and Chruszcz M (2006) HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution - - from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr 62, 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, and Adams PD (2012) Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr 68, 352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen VB, Arendall WB III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, and Richardson DC (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr 66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Lano WL (2002) The PyMol molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zallot R, Oberg N, and Gerlt JA (2019) The EFI web resource for genomic enzymology tools: leveraging protein, genome, and metagenome databases to discover novel enzymes, and metabolic pathways. Biochemistry 58, 4169–4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, and Ideker T (2003) Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13, 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen DG, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, and Higgins. (2011) D.G. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7, 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirel P-H, Schmitter J-M, Dessen P, Fayat G, and Blanquet S (1989) Extent of N-terminal methionine excision from Escherichia coli proteins is governed by the side-chain length of the penultimate amino acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 86, 8247–8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeVieux JA, Baas B-J, Kaoud TS, Davidson R, Babbitt PC, Zhang YJ, Whitman CP (2017) Kinetic and structural characterization of a cis-3-chloroacrylic acid dehalogenase homologue in Pseudomonas sp. UW4: A potential step between subgroups in the tautomerase superfamily, Arch Biochem Biophys, 636, 50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czerwinski RM, Johnson WH Jr., Whitman CP, Harris TK, Abeygunawardana C, and Mildvan AS (1997) Kinetic and structural effects of mutations of the catalytic amino-terminal proline in 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase. Biochemistry 36, 14551–14560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duggleby HJ, Tolley SP, Hill CP, Dodson EJ, Dodson G, and Moody PC (1995) Penicillin acylase has a single-amino-acid catalytic centre. Nature 373, 264–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grigorenko BL, Khrenova MG, Nilov DK, Nemukhin AV, and Švedas VK (2014) Catalytic cycle of penicillin acylase from Escherichia coli: QM/MM modeling of chemical transformations in the enzyme active site upon penicillin G hydrolysis. ACS Catal. 4, 2521–2529. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.