Abstract

The task of informing workers of hazards in the workplace is seldom more difficult than with the subject of reproductive and developmental hazards. Occupational health staff and physicians are faced with a paucity of relevant medical information. Workers, kept aware of the thalidomide spectre with every media report of the latest descriptive epidemiology study, are anxious to know more. Employers, knowing that few agents are regulated on the basis of reproductive hazards, are encouraged to lessen workplace exposure to all agents but need guidance from government and scientists in setting priorities. Understandable ethical and scientific limitations on human studies require researchers to study animals and cells. The difficulties of extrapolating the results of this research to humans are well known. The scientific, medical, and workplace difficulties in dealing with reproductive and developmental hazards are mirrored in the regulatory positions found in North America. Some regard fetal protection policies as sex discrimination whereas others consider such policies as reasonable. Guidelines are provided to allow employers and medical practitioners to consider this difficult problem.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ahlborg G. A., Jr Validity of exposure data obtained by questionnaire. Two examples from occupational reproductive studies. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990 Aug;16(4):284–288. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlborg G., Jr Pregnancy outcome among women working in laundries and dry-cleaning shops using tetrachloroethylene. Am J Ind Med. 1990;17(5):567–575. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700170503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger D., Leviton A., Waternaux C., Needleman H., Rabinowitz M. Longitudinal analyses of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N Engl J Med. 1987 Apr 23;316(17):1037–1043. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704233161701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman D. J., Anderson K. E., Buffler P., Salg J. Surveillance for work-related adverse reproductive outcomes. Am J Public Health. 1989 Dec;79 (Suppl):53–57. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.suppl.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brender J. D., Suarez L. Paternal occupation and anencephaly. Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Mar;131(3):517–521. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug abuse and brain development. Proceedings of the Sixth International Neurotoxicology Conference. October 10-14, 1988, Little Rock, Arkansas. Neurotoxicology. 1989 Fall;10(3):305–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M. J., Hall A. J., Snee M. P., Downes S., Powell C. A., Terrell J. D. Methods and basic data of case-control study of leukaemia and lymphoma among young people near Sellafield nuclear plant in West Cumbria. BMJ. 1990 Feb 17;300(6722):429–434. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6722.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M. J., Snee M. P., Hall A. J., Powell C. A., Downes S., Terrell J. D. Results of case-control study of leukaemia and lymphoma among young people near Sellafield nuclear plant in West Cumbria. BMJ. 1990 Feb 17;300(6722):423–429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6722.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer R. A. Transplacental transport of lead. Environ Health Perspect. 1990 Nov;89:101–105. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9089101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirguis S. S., Pelmear P. L., Roy M. L., Wong L. Health effects associated with exposure to anaesthetic gases in Ontario hospital personnel. Br J Ind Med. 1990 Jul;47(7):490–497. doi: 10.1136/oem.47.7.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R. M., Hegemier S., Tennyson L. M. The fetal alcohol syndrome: a multihandicapped child. Neurotoxicology. 1989 Fall;10(3):585–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein J. S., Frumkin H. The right to know about toxic exposures. Implications for physicians. N Engl J Med. 1985 Mar 14;312(11):687–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198503143121104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huel G., Mergler D., Bowler R. Evidence for adverse reproductive outcomes among women microelectronic assembly workers. Br J Ind Med. 1990 Jun;47(6):400–404. doi: 10.1136/oem.47.6.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Martin. Did I begin? New Sci. 1989 Dec 9;124(1694):39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg C. K. Benzodiazepines: influence on the developing brain. Prog Brain Res. 1988;73:207–228. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60506-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren G., Chang N., Gonen R., Klein J., Weiner L., Demshar H., Pizzolato S., Radde I., Shime J. Lead exposure among mothers and their newborns in Toronto. CMAJ. 1990 Jun 1;142(11):1241–1244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemasters G. K., Samuels S. J., Morrison J. A., Brooks S. M. Reproductive outcomes of pregnant workers employed at 36 reinforced plastics companies. II. Lowered birth weight. J Occup Med. 1989 Feb;31(2):115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. J., Mathew R. M., Chenault C. B., Brown M. H., Hurtt M. E., Bentley K. S., Mohr K. L., Working P. K. Differences in the quality of semen in outdoor workers during summer and winter. N Engl J Med. 1990 Jul 5;323(1):12–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007053230103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

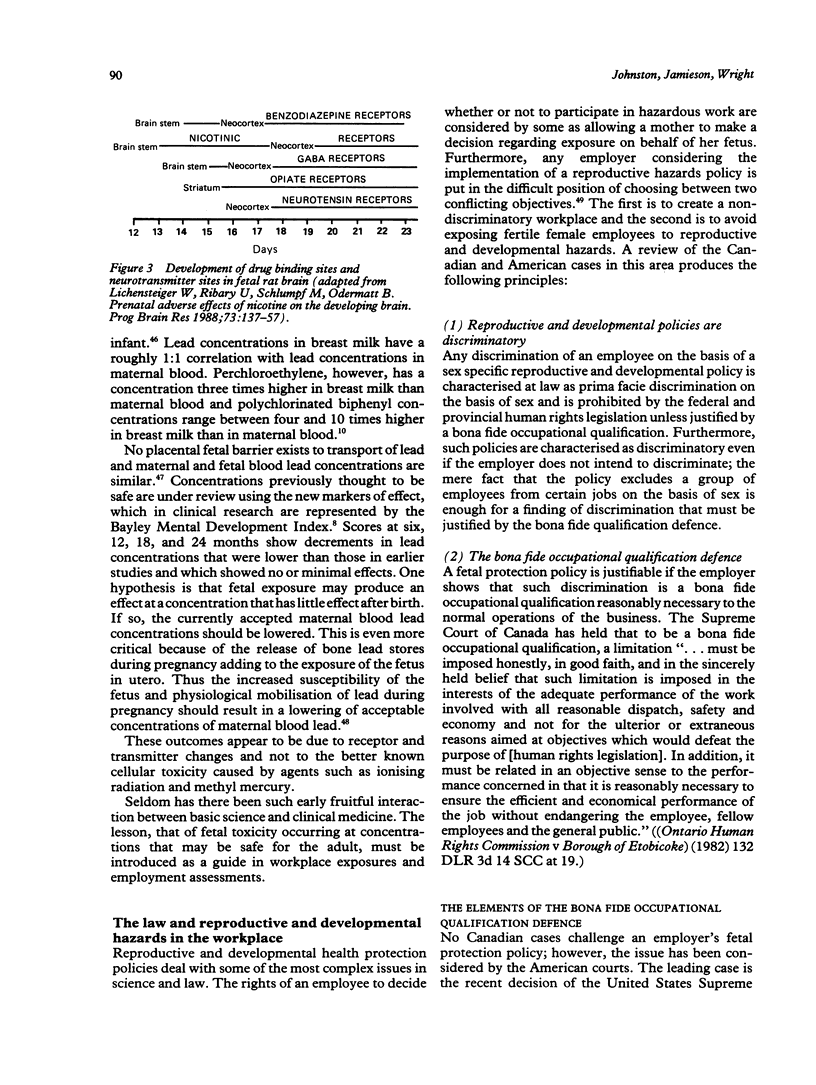

- Lichtensteiger W., Ribary U., Schlumpf M., Odermatt B., Widmer H. R. Prenatal adverse effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Prog Brain Res. 1988;73:137–157. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindbohm M. L., Taskinen H., Sallmén M., Hemminki K. Spontaneous abortions among women exposed to organic solvents. Am J Ind Med. 1990;17(4):449–463. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700170404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry F. VDTs and health: many studies, few answers. CMAJ. 1989 Nov 1;141(9):974–977. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry R. B., Thunem N. Y., Anderson-Redick S. Alberta Congenital Anomalies Surveillance System. CMAJ. 1989 Dec 1;141(11):1155–1159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. D., McDonald J. C. Outcome of pregnancy in leatherworkers. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986 Apr 12;292(6526):979–981. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6526.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen G. W., Lanham J. M., Bodner K. M., Hylton D. B., Bond G. G. Determinants of spermatogenesis recovery among workers exposed to 1,2-dibromo-3-chloropropane. J Occup Med. 1990 Oct;32(10):979–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshan A. F., Teschke K., Baird P. A. Birth defects among offspring of firemen. Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Feb;131(2):312–321. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M., Himmelstein J. Reproductive hazards in the workplace: what the practitioner needs to know about chemical exposures. Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Jun;71(6 Pt 1):921–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajhans G. S., Brown D. A., Whaley D., Wong L., Guirguis S. S. Hygiene aspects of occupational exposure to waste anaesthetic gases in Ontario hospitals. Ann Occup Hyg. 1989;33(1):27–45. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/33.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo M., Muñoz N., Day N., Parra J. E., Hernandez C., Blettner M., Giraldo A. Birth defects among children born to a population occupationally exposed to pesticides in Colombia. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990 Aug;16(4):239–246. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

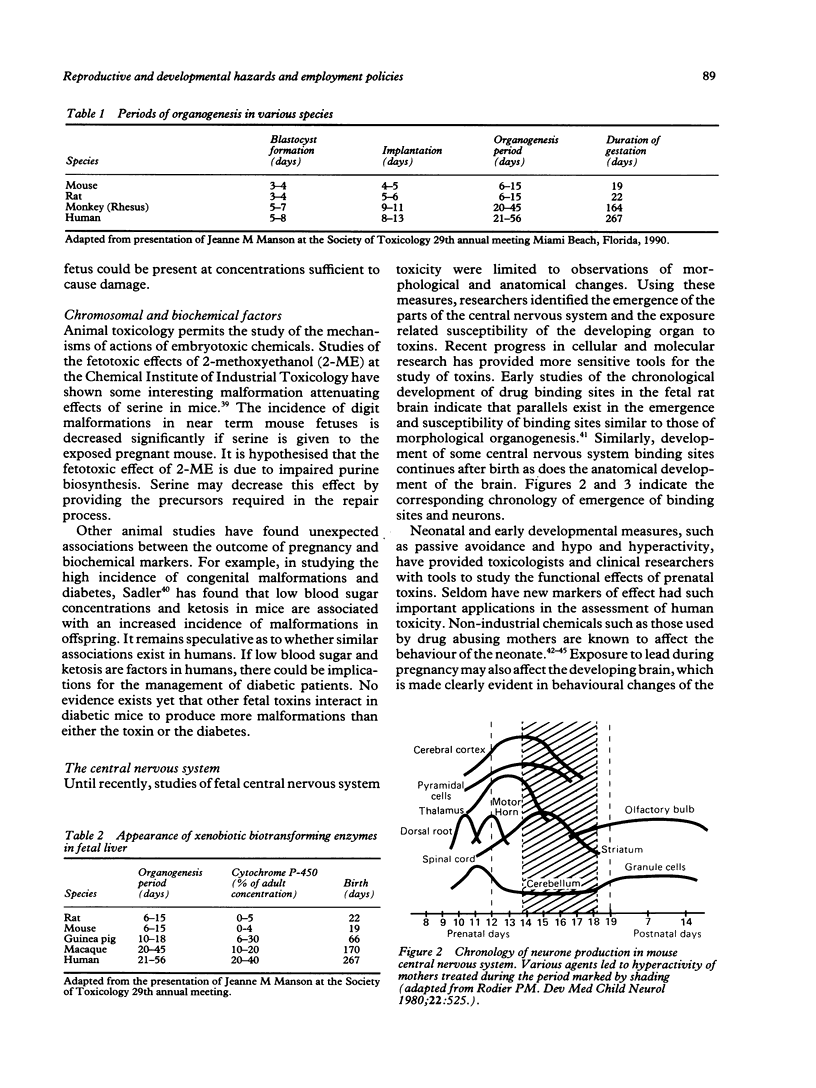

- Rodier P. M. Chronology of neuron development: animal studies and their clinical implications. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1980 Aug;22(4):525–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1980.tb04363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier P. M. Structural--functional relationships in experimentally induced brain damage. Prog Brain Res. 1988;73:335–348. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier P. M. Structural--functional relationships in experimentally induced brain damage. Prog Brain Res. 1988;73:335–348. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld E. K. Toward the twenty-first century: lessons from lead and lessons yet to learn. Environ Health Perspect. 1990 Jun;86:191–196. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9086191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithells R. W., Sheppard S. Teratogenicity testing in humans: a method demonstrating safety of bendectin. Teratology. 1978 Feb;17(1):31–35. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420170109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stücker I., Caillard J. F., Collin R., Gout M., Poyen D., Hémon D. Risk of spontaneous abortion among nurses handling antineoplastic drugs. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990 Apr;16(2):102–107. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taskinen H. K. Effects of parental occupational exposures on spontaneous abortion and congenital malformation. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990 Oct;16(5):297–314. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. A., Ballantyne B. Occupational reproductive risks: sources, surveillance, and testing. J Occup Med. 1990 Jun;32(6):547–554. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199006000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]