Abstract

Objective:

News media has recently been replete with stories of anti-Asian rhetoric and racism related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Empirical literature, however, has yet to systematically analyze and document these experiences and their impact. Our study aimed to examine this phenomenon by analyzing news media coverage published between December 31, 2019–June 30, 2020 on COVID-related anti-Asian incidents.

Method:

We utilized a phenomenological approach to conduct qualitative content analysis of 84 media articles reporting on coronavirus related anti-Asian incidents. We also present the emerging psychological framework of race-based stress and trauma to conceptualize the psychological impact of these race-based incidents reported in the media.

Results:

Qualitative analysis revealed five primary themes: (a) pathologizing cultural practices; (b) alien in one’s own land; (c) invalidation of interethnic differences; (d) ascription of diseased status; and (e) duality of frontline hero and virus carrier. We provide examples for each of these themes.

Conclusion:

These themes document stigmatizing narratives and demonstrate the phenomenology of race-based stress and trauma experienced by Asian individuals during the COVID era. We present potential implications for mental health of Asian individuals during and following the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as recommendations for future research.

Keywords: COVID-19, Asian, qualitative, racism, race-based stress and trauma

In the first 7 months of the “Coronavirus Disease of 2019” (COVID-19) pandemic, over 20 million cases were confirmed, with over 730,000 associated deaths worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO, 2020a]). The universal scale of the economic, social, and public health consequences of the pandemic is unprecedented, expedited by globalization of travel and instantaneous spread of information online. The spreading of viral infection from Wuhan, China, where COVID-19 originated (Phelan et al., 2020), was closely accompanied by news of anti-Chinese and anti-Asian sentiment around the world. News and social media have been replete with stories of anti-Asian rhetoric, stigma, and racism (e.g., Lee, 2020; Zhou, 2020), prompting various efforts to report and monitor incidents (e.g., Asian Americans Advancing Justice, 2020) One U.S.-based reporting center initiative issued a press release indicating that its site logged over 1,700 reports of coronavirus-related discrimination experienced by Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the first 6 weeks of its launch (A3PCON, 2020). Given the latency to publication, empirical literature has yet to systematically analyze and document Asian experiences of COVID-19 race-based harassment and stress. The purpose of this study is to apply a psychological framework of race-based stress and trauma to analyze and thematically organize the psychological impact of COVID-19 race-based incidents reported in the media.

Race-Based Stress and Trauma

Race-based stress and trauma is an emerging psychological framework that shifts the conversation about trauma from acute, incident-based trauma to the chronic stress and retraumatization associated with racism (Williams et al., 2018). Racism, as a chronic stressor contributing to negative health outcomes, has been well-documented across disciplines (e.g., Geronimus et al., 2006; WHO, 2008). However, mental health symptoms resulting from racism, have not been typically categorized or acknowledged in psychiatric diagnostic criteria (Poussaint, 2002). Indeed, a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM–5), requires a single “Criterion A” incident where one is exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Chronic experiences of racism often do not “qualify.” In order to address the psychological distress resulting from repeated exposure to negative race-based encounters, researchers have begun to conceptualize this phenomenon using various terms, such as “race-based traumatic stress” (Carter, 2007) and “race-based stress and trauma” (Carlson et al., 2018) among others. In this emerging literature, however, Asian populations have not been the focus for conceptualization or research. In this article, the authors use a race-based stress and trauma framework to qualitatively examine coronavirus-related anti-Asian incidents reported in the media, in order to understand the underlying stigma and psychological impact associated with COVID-19 racism on Asian individuals around the world.

Method

We implemented a phenomenological approach to qualitative content analysis (QCA; Elo & Kyngäs, 2008; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) in order to explore Asian experiences of COVID-19 race-based incidents reported in the media. Phenomenological theory (Davidsen, 2013) prescribes engaging in a descriptive investigation of a phenomenon by seeking to understand the perspective of those who have experienced it, with the goal of describing the meaning of what was experienced and how it was experienced (Neubauer et al., 2019).

Qualitative content analysis is a research technique that moves away from the focus on objectivity as maintained by traditional quantitative analysis (Berelson, 1952) in order to allow for “the subjective interpretation of the content of text data” (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005, p.1278) while utilizing systematic classification processes in coding and thematic pattern identification (Kaefer et al., 2015). A phenomenological approach to content analysis allows for inductive coding to elucidate novel themes derived from the data, as well as deductive coding to reinterpret previously determined themes, if they exist. The unique circumstances related to COVID-19 compel inductive coding, as new experiences or phenomena are certainly present. However, given a well-established framework in the racial microaggressions literature documenting Asian experiences in the U.S. (Sue, Bucceri, et al., 2007; Sue, Capodilupo, et al., 2007), and in other countries such as Australia (Li, 2019), and Canada (Houshmand et al., 2014), we also conducted deductive coding to explore their manifestations during the coronavirus era. Importantly, phenomenological qualitative analysis seeks not to “reveal universal objective facts,” but to allow researchers to apply theoretical expertise in interpreting and communicating one perspective (among a great diversity of possible perspectives) on a given topic (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). Previous research has utilized similar qualitative methodology to examine news media articles on a range of emerging phenomena; for example, online news media coverage of weight loss surgery (Glenn et al., 2012), news about primary school curriculum changes (Tasdemir & Kus, 2011), and media coverage of climate change and carbon emissions (Kaefer et al., 2015) among others.

Data Collection

We conducted a Google (www.google.com) search for COVID-19 (using COVID-19, coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2) and racism (using racism, discrimination, harassment, stigma, microaggressions, or xenophobia). We used advanced settings to restrict returns to English language articles published between December 31, 2019 (first reported cases of COVID-19) and June 30, 2020 (date of search). As Google query returns can be innumerable, results are sorted based on an algorithm of importance, whereby the most relevant returns are listed first or earlier (Brin & Page, 1998). Given our resource limitations, we could not systematically analyze every single search return of the millions of returns. We planned in an a priori manner to utilize Saunders et al.’s (2018) definition of qualitative data saturation, which prescribes data collection to be complete when “new data repeat what was expressed in the previous data,” reading search returns until data saturation.

The unit of analysis was the narrative arc of each incident of prejudicial and discriminatory behavior related to COVID-19, against an Asian target, including targets’ descriptions of the incidents and their reports of psychological sequalae. The first and second author screened search results in order of appearance for initial inclusion criteria of (a) being related to COVID-19, (b) being related to racism—where the text referenced race or ethnicity as being related to the incident, and (c) mentioning the targets as individuals of any Asian descent. As we read each search result, we created a timeline of incidents from December 31, 2019–June 30, 2020 with brief descriptors of the incident described (what happened, to whom, and where), in order to identify when novel incidents were referenced. Multiple articles could reference the same incident with different details; as the incident was the unit of analysis, we added additional notes to the timeline to link multiple articles to the same incident. After 84 articles were read and linked to the timeline, we found that additional search results were not yielding information about novel incidents and determined sufficient data saturation for moving on to analytical procedures. No articles were excluded from analyses, as each of the 84 returns met inclusion criteria.

Data Analysis

To facilitate immersion into the data, the 84 articles were read and reread in temporal order by the first two authors, who then independently conducted thematic coding. An initial codebook was generated for deductive coding using Sue et al.’s (2007) eight microaggressive themes affecting Asian Americans: alien in own land, ascription of intelligence, exoticization of Asian women, invalidation of interethnic differences, denial of racial reality, pathologizing cultural values/communication styles, second class citizenship, and invisibility. New codes emerging from inductive coding that reflected additional themes related to COVID-19 race-based stress and trauma were then added to the codebook, and the articles were rereviewed against these codes. The coders met weekly to review progress and compare discrepancies in codes, which occurred infrequently (< 10%; suggesting sufficient reliability (Miles & Huberman, 1994) and were reconciled by discussion (Zade et al., 2018) until consensus was reached. Our third author conducted functions of an independent auditor (Nadal et al., 2012) by reviewing the coding team’s codes and chosen quotations for accuracy and provided feedback to the team, who then made revisions based on the feedback. Guided by phenomenology and QCA theory, all authors met to discuss coding results to describe inductive and deductive themes that emerged from the data. This study was exempt from institutional review, as it involved a review of published and publicly-available articles.

Researchers’ Backgrounds

The qualitative research team consisted of three Asian American female identified researchers, ranging in generational status from first (U.S. born, internationally raised, and returned to the U.S. as an adult) to 2.5 (born to parents who immigrated to the U.S. as emerging adults), of Taiwanese, Chinese, and Vietnamese American ethnic backgrounds. One member is an assistant professor of psychology on the U.S. West Coast, another member is an assistant professor in a medical university in the U.S. Midwest, and the third member works as a research assistant for a nonprofit health care research organization located in the U.S. East Coast. Guided by principles of reflexivity in qualitative research (Patnaik, 2013; Palaganas et al., 2017; Subramani, 2019), we continuously reflected on our backgrounds to clarify the lenses used to arrive at our interpretations.

Results

Our qualitative content analysis yielded five primary themes related to the phenomenon of COVID-19 anti-Asian racism and race-based stress. While each racist incident was analyzed as the unit of analysis, incidents may reflect multiple themes concurrently.

Theme 1: Pathologizing Cultural Practices

Theme 1 refers to the process of designating Asian, and as particularly salient in our analyses, Chinese cultural practices, as abnormal or unacceptable, while maintaining dominant or White cultural practices as normal or ideal. For example, an early theory about COVID-19’s origin suggested that the virus spread to humans through the consumption of bats at the Huanan Wet Market in Wuhan, China. Despite lack of confirmation of the veracity of this theory, there was swift blame and criticism placed on the lifestyles and food practices of people in China. Media sources such as National Public Radio (NPR) erroneously indicated that “patients who came down with disease at the end of December all had connections to the Huanan Seafood Market,” using sensationalist imagery such as “countertops of the stalls are red with blood…there’s lots of water, blood, fish scales, and chicken guts…” to describe wet markets (Beaubien, 2020). The Wall Street Journal described the Huanan market as “offering carcasses and live specimens of dozens of wild animals—from bamboo rats to ostriches, baby crocodiles and hedgehogs,” highlighting these rare examples rather than more predominant examples, such as produce, seafood, and farmed and domesticated meat products, also ubiquitously sold at wet markets (Page, 2020). The British Daily Mail (Knowles, 2020) published the headline, “Will they ever learn? Chinese markets are still selling bats and slaughtering rabbits on blood-soaked floors as Beijing celebrates ‘victory’ over the coronavirus.” The article described “terrified dogs and cats crammed into rusty cages,” accompanied by a video of a woman eating bat soup (later clarified to have been filmed not in China; Palmer, 2020). The article prompted extensive comments by readers describing Chinese people as “disgusting,” “backward,” and “cruel.”

These language choices communicate denigrating messages about wet markets and disparaging them beyond the potential for propagating disease, thus passing judgment on Chinese peoples’ lifestyles more generally. Although wet markets are present worldwide, often serving as tourist attractions (for example, Pike Place Market in Seattle, Washington), portraying Chinese wet markets as “incubator[s] for novel pathogens,” as described in The New York Times (Myers, 2020), condemns Chinese cultural practices. This pathologization contributes to stigmatizing narratives against Asians, augmenting their experience of race-based stress during COVID.

Theme 2: Alien in One’s Own Land

Following the global progression of COVID-19, the Asian diaspora living in the West has frequently experienced alienation in its own land, with others increasingly viewing Asians as foreigners. This was illustrated when two Hmong American men arrived at a Super 8 hotel in Plymouth, Indiana. The hotel employee allegedly demanded if they were from China and asserted that their policy was to turn away anyone from China to be quarantined (Sandleben, 2020). Although they were American, the employee implicitly interpreted their Asian appearance as foreign and likely from China.

Another example comes from reports of an Asian American father and son who were walking in Queens, New York, when a stranger yelled, “You f*ing Chinese!” at them. He then followed the pair to a bus stop and struck the father in the head (Henry & Bensimon, 2020). The father and son were reported to be “scared,” “worried,” and “shaken,” with the father saying, “He came at me because I was Chinese, but I’m American.” The perpetrator was charged by the police with a hate crime, and the father described subsequently teaching his son to be “hyperaware” of surroundings and to “avoid this kind of situation” (Bensimon, 2020).

A third example is from April 16, 2020, when U.S. President Donald Trump tweeted a video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi from February (3 weeks before the stay-at-home order). Pelosi is seen in the video advocating on behalf of San Francisco’s Chinatown, encouraging people to visit as precautions had been taken, and urging people not to discriminate against Asian-owned businesses. Trump criticized Pelosi as being “crazy” for wanting people to visit Chinatown long after “[he] closed the border to China” and accused her of being responsible for many deaths (Trump, 2020a). NBC reported that Trump may be “equating Chinatown with China,” and that the tweet received backlash from the Asian and Asian American community and representatives (Yam, 2020). Responding tweets accused Trump of being unable to distinguish between Chinese nationals and Asian Americans, saying his actions were causing Asians and Asian Americans to be perceived as “perpetual foreigners” and enabling anti-Asian discrimination (Chu, 2020; Lu, 2020)

Theme 3: Invalidation of Interethnic Differences

The origin of COVID-19 in China has not only been followed by increased racism against those of Chinese descent, but against individuals who appear to be of Asian descent, denying the diversity and differences among Asian ethnicities. This phenomenon reflects the continually existing perception among many that “all Asians look alike” (Sue, Bucceri, et al., 2007) and are therefore the same. In addition, it equates the term Asian with East Asian, marginalizing others such as South Asian or Brown Asians in the process (Nadal, 2019). During COVID, this has often translated to all Asians being associated with China, where the virus originated. A widely shared example is the assault of a Singaporean student, J. Mok, attending University College in London (BBC News, 2020b). While walking home at night, a group of men shouted, “I do not want your coronavirus in my country,” and attacked him, resulting in multiple severe injuries (Mok, 2020). Although Mok is Singaporean, not from China, and had been studying in London for the past 2 years, his assailants disregarded interethnic differences while simultaneously ascribing blame for the COVID-19 crisis to him.

Another manifestation occurred when a Vietnamese curator in London, A. Nguyen, received an email from an exhibitor in early March, describing why her invitation to a United Kingdom art fair had been withdrawn. The email detailed, “The coronavirus is causing much anxiety everywhere, and fairly or not, Asians are being seen as carriers of the virus,” and the exhibitor was worried her presence might deter audiences from attending (Stolworthy, 2020). While Nguyen is Vietnamese, the exhibitor associated her with China and the virus, invalidating interethnic Asian differences.

In the Netherlands, a Korean-Dutch interpreter was cycling home when two men on a scooter drove past her, shouted “Chinese,” and attempted to punch her (Rajagopalan, 2020). She swerved to avoid the punch and nearly fell off her bike. The woman reported feeling “terrified”, particularly because the incident occurred when she was traveling alone at night. She reported being “so shaken” that she decided to stop going out after dark following the incident.

On the subway in Los Angeles, a Thai American, T. Jiraprapasuke, reported being the target of a verbal attack. She described a man nearby shouting about the coronavirus, blaming China as the source of the virus, exclaiming “F*** Chinese” … “every disease comes from China”… and “They’re f***ing disgusting” (Jiraprapasuke, 2020a, 2020b). In an interview with CNN (Cable News Network), Jiraprapasuke noted that she initially did not realize that the man was targeting her until he started gesturing toward her while speaking (Cooper, 2020). In the interview, she describes examples of the race-based stress and trauma she experienced, indicating how scared she was as the only person of Asian descent on the train, as the shouting went on for over 15 min and escalated until the man stepped off the train. When no ally came to her defense, she felt “alone, unsafe, and trapped on the train.” She described that “it was a terrifying experience” and that she had not experienced that level of fear in her entire life. Jiraprapasuke also described the experience as surprising—despite not being Chinese, the man was attacking her because he perceived her to look a certain way (Gostanian et al., 2020).

Theme 4: Ascription of Diseased Status

Relatedly, both examples of Mok and Nguyen highlight another anti-Asian race-based theme during COVID-19, where individuals appearing to be of Asian descent are automatically assumed to be sick. In effect, beyond ascribing blame to Asian individuals for COVID-19 and its consequences, some have ascribed infection with COVID-19 itself. In Nguyen’s case, the exhibitor was concerned that fears of Nguyen carrying the virus may prevent audience members from entering the exhibition space (Stolworthy, 2020). That Nguyen was withdrawn from the art fair for this reason illuminates an alarming, false narrative: that anyone with an Asian appearance is assumed to be infected with COVID-19. Similarly, Mok was assumed to be a carrier of the virus based on his assailant’s perception of his racial appearance.

A. Choi, a Korean American, was in a bathroom at New York’s Penn Station when he heard someone spit and realized a man had spit in his hair. Choi recalled asking the man “Why?,” to which the man responded, “You Chinese f*. All of you should die and all of you have the ‘Chinese virus’.” Choi expressed feeling “embarrassed, angry, and disgusted” by the encounter. He also attempted to report the incident to the nearest police officer, who indicated that what the perpetrator did was “not a crime” and therefore unlikely to be prosecutable (Yakas, 2020).

Another example from New York City, an early epicenter of the pandemic in the U.S., occurred when a woman named I. Chen was walking and a man called after her, saying “Hey, Ms. Lee, I’d be into you if you didn’t carry the virus.” He then proceeded to follow her on his bike, shouting, “This is why Asian men beat their wives.” Chen expressed feeling afraid that she was in physical danger. Following this encounter, she reported doing everything possible to avoid similar situations (a race-based trauma symptom), for instance, walking “40 blocks to avoid taking the bus or subway” or wearing a “big hat and sunglasses” to hide her Asian appearance (Kambhampaty & Sakaguchi, 2020).

More subtle instances of this have also been documented. From January to July 2020 (when this article was written), as COVID-19 has progressed globally, videos have surfaced of people on public transportation automatically covering their faces or moving away when an Asian person enters the bus or subway (Kaci, 2020). The belief that Asian-appearing individuals carry the virus has led to avoidant behavior from bystanders.

A critical incident progressing beyond simple avoidance occurred on March 14, 2020, when three Asian Americans, a father and his 2-year-old and 6-year-old sons, were stabbed by a 19-year-old Hispanic man, Jose Gomez, at a Sam’s Club in Midland, Texas (CBS, 2020a). According to a report of the arrest affidavit (CBS, 2020b), Gomez attempted to kill the family while they were shopping in the store. A Sam’s Club employee who tried to stop Gomez was also stabbed; he and an off-duty border patrol agent were able to remove Gomez’s knife and hold him until the Midland police arrived. Gomez was charged with three counts of attempted capital murder and one count of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. The FBI investigated this case, and, in a report warning against increasing incidents of hate crimes against Asian Americans, described the suspect’s confessed motive for stabbing the family: “he thought the family was Chinese, and infecting people with the coronavirus” (Margolin, 2020).

Ascription of a diseased status to individuals based on Asian race has also occurred from the American presidential office. On March 10, 2020; Trump began to switch his rhetoric from referring to COVID-19 as “the virus” to referring to it as the “China/Chinese Virus” (Trump, 2020b). He first did this by retweeting support for the Mexican-U.S. border wall, saying “with China Virus spreading around the globe… we need the Wall more than ever!” Then, he shared an original tweet stating, “The United States will be powerfully supporting those industries, like Airlines [sic] and others, that are particularly affected by the Chinese Virus” (Trump, 2020c). Another tweet, revealing a photograph of his notes for a briefing later that week (Botsford, 2020), showed that the word “corona” and “coronavirus” had been crossed out and replaced with the word “Chinese” in what was reported to be Trump’s own handwriting. He, and other elected U.S. officials have also referred to COVID-19 as the “Wuhan virus” and “Kung Flu”, which have been characterized as “weaponized language” (Nakamura, 2020).

The viral hashtag #JeNeSuisPasUnVirus (“I am not a virus”) from France is an example in Europe of ascribing diseased status to those of Asian descent. French Asians reported accounts of racism such as others avoiding them on public transit, strangers asking them to put masks on, and getting asked if they are dangerous when they cough (Kaci, 2020). On January 28, 2020, a Twitter user posted a picture of the hashtag written on a piece of paper, with the caption: “I’m Chinese, but I’m not a virus! I know everyone’s scared of the virus but no prejudice, please,” which resonated with many and went viral with 40,000 likes (Chengwang, 2020). This hashtag reflects the frustration and sadness that French Asians feel due to being stigmatized and discriminated against in the COVID-19 era (Coste & Amiel, 2020). French media sources, such as the newspaper Le Courrier Picard, have also perpetuated this theme by using headlines like “Alerte jaune” (Yellow alert) and “Le péril jaune?” (Yellow peril?), to describe the growing pandemic, with an image of a Chinese woman wearing a mask on the cover. This newspaper received a large amount of backlash and later apologized, saying they had not intended to perpetuate some of the “worst Asian stereotypes” (BBC News, 2020a).

Theme 5: Duality of Frontline Hero and Virus Carrier

Asian health care workers around the world are navigating a duality of simultaneously being celebrated as heroes working to combat the virus in the face of significant health risk to themselves, while also being targets of anti-Asian discrimination, ranging from their services being refused by patients, to being spit on or assaulted (Natividad, 2020). Asian physicians have described patients in the emergency room who have declined care from them, explaining “I’m not racist, I just do not want to get the virus.” Others have been asked if “Someone not from China could take care of them” (Fu, 2020; Wahlquist & Australian Associated Press, 2020; Yi, 2020).

On March 15, 2020; R. Quaichon, a nurse in Brighton, England described in a video on Facebook that she had just been racially abused by a White couple at a train station on her way to a night shift at the hospital. She expressed how “mentally shattered” she was from the experience. She reported that the man elbowed her in the ribs, shoving her to the side, while the woman with him yelled, “at least we are Whites you f***ing c***” (Gilroy, 2020). She then described that the juxtaposition of caring for COVID patients in an overtime night shift while being treated so inhumanely felt like an oxymoron (Coates, 2020; Quaichon, 2020).

J. Tsui, a nurse in New York City, was waiting for the train when a man approached and said that he should “go back to his country” due to “all these sicknesses…spread by ‘chinks’” (Kambhampaty & Sakaguchi, 2020). The man advanced toward Tsui, causing him to back up to the edge of the platform. A bystander defended Tsui, highlighting his health care provider status saying, “Leave him alone. Cannot you see he’s a nurse? That he’s wearing scrubs?” After boarding the train, Tsui reported feeling afraid to get off in case the perpetrator followed him to a location without witnesses, as the man continued to antagonize and motion to him, “I’m watching you.”

The duality is also reflected in Dr. S. Fujimoto’s experience in New York, who described feeling “revered, but also paradoxically feared,” a sentiment echoed by his Asian American colleagues in health care. Dr. C. Fu explains that “Asian American doctors are both celebrated and villainized.” Other providers report feeling “blamed,” “disappointed,” “left speechless,” and “worried” due to COVID-19 racism (Fu, 2020; Wong, 2020).

Discussion

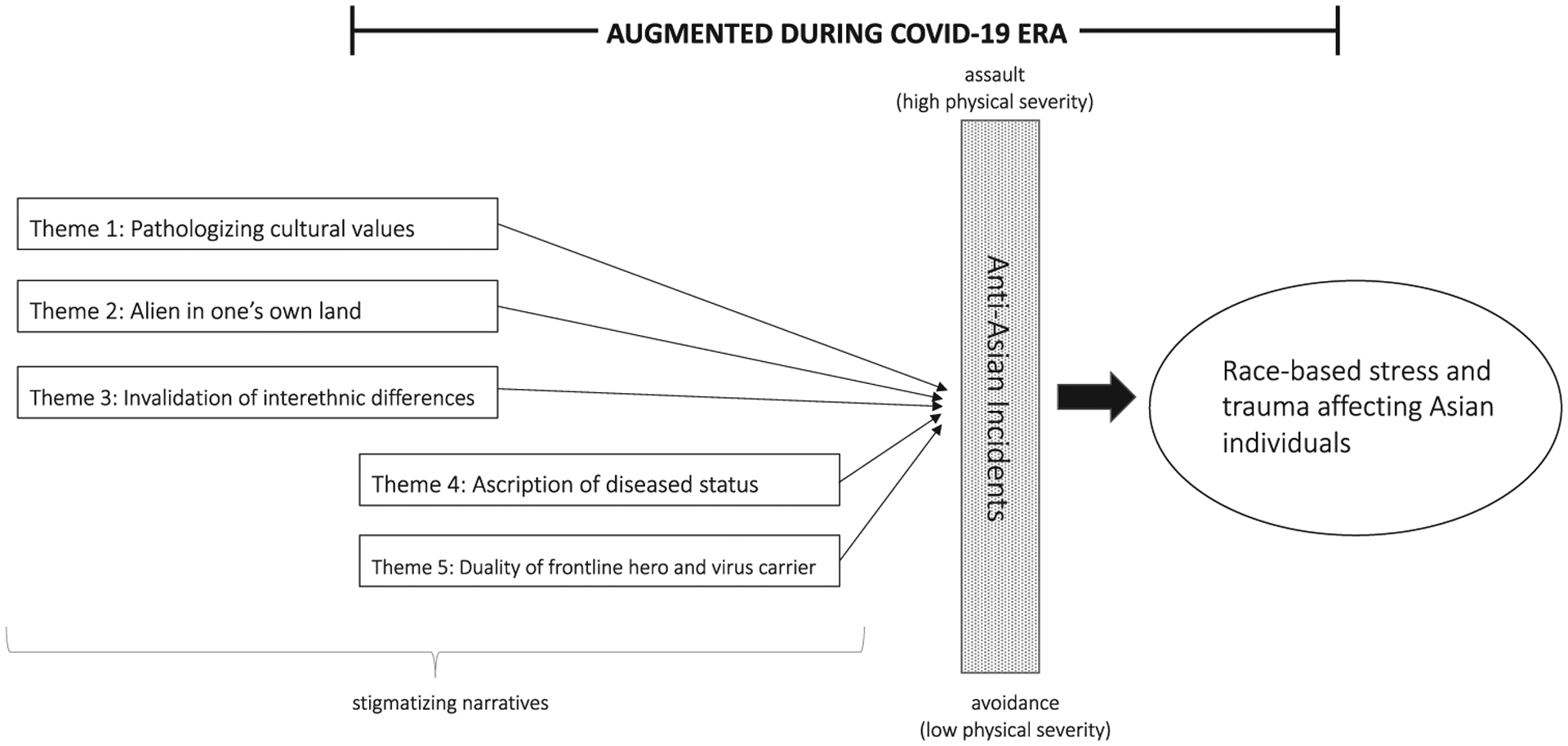

In this article, we present a novel contribution to empirical literature by providing the first phenomenological exploration to our knowledge of incidents of COVID-19 anti-Asian racism and race-based stress reported in the media. Five themes reflecting stigmatizing narratives emerged from our qualitative analyses, which we illustrate in Figure 1. The first three were derived from deductive coding, which reflect themes affecting Asian individuals prior to existence of COVID-19, but were augmented during the current coronavirus era: (Theme 1) pathologizing cultural values, where Asian behaviors are considered abnormal; (Theme 2) alien in one’s own land, where individuals of Asian descent are perpetually assumed to be foreigners or outsiders; and (Theme 3) invalidation of interethnic differences by denying diversity among Asian ethnicities. The next two themes were novel during COVID; (Theme 4) ascription of diseased status refers to Asian people being presumed to be infected with the coronavirus, a carrier of the virus, or sick, on the basis of their race; and (Theme 5) duality of frontline hero and virus carrier, where Asian doctors, nurses, and health care providers describe being simultaneously essential while also perceived as threats.

Figure 1.

Model of Race-Based Stress Themes

The targets of the racist incidents who were interviewed directly reported a range of psychological responses due to the incidents, such as distressing memories of the incidents, avoidance of people, places, and situations that remind them of the incidents (including public transit, commuting alone, and walking after dark), negative alterations in cognitions and mood (such as feeling “terrified,” “scared,” “worried”), and changes in reactivity (such as being “hyperaware”). These consequences respectively reflect some symptom criteria for PTSD, such as Criterion b, intrusion symptoms (distressing memories); Criterion c, avoidance of trauma reminders; Criterion d, negative alterations in cognitions and mood; and Criterion e, alterations in arousal and reactivity (APA, 2013) and can be understood within the framework of race-based stress impacting Asian individuals who experience and anticipate stigma during COVID-19 and beyond.

In addition to presenting the five distinct themes, we also offer a multidimensional interpretation of the relationships among the themes. First, the race-based incidents described in the articles may reflect several themes at once; for example, non-Chinese Asian individuals who experience verbal assaults about carrying the virus reflect both invalidation of interethnic differences along with ascription of diseased status. Second, incidents in each theme reflect a scale of physical severity, ranging from microaggressions such as avoidance, to verbal insults, to bodily assault without injury, and finally to bodily assault with injury. Third, each theme may involve incidents enacted in different spheres of racism, at the interpersonal level between individuals, or at broader cultural and institutional levels (Nazroo et al., 2020). Interpersonal racism examples include J. Mok in London or A. Choi in New York City, where individual perpetrators are enacting racism by yelling racial slurs and spitting on or physically assaulting their targets. Institutional racism is reflected in instances where targets are denied entry into public spaces such as hotels or subways. Misrepresentation by the media and misnaming of the virus by political figures can also be understood to reflect racism occurring at broader institutional or cultural levels.

For example, shortly after Trump first tweeted about the “Chinese Virus,” the Executive Director of WHO’s Emergencies Program warned against the referral of COVID-19 in that manner. Ryan encouraged caution in language choice when discussing the virus, suggesting that inappropriate labeling could encourage profiling of individuals and xenophobic behavior (WHO, 2020b). Similarly, the WHO Director-General expressed that “stigma is more dangerous than the virus itself” (WHO, 2020c).

The Center for Public Integrity conducted a population-based poll of 1,000 Americans and found that 29% of respondents “blamed China or Chinese people for the COVID-19 pandemic” (Jackson et al., 2020). In addition, 32% witnessed others “blaming Asian people for the COVID-19 pandemic.” This data points to the possible aggregate impact of the range of incidents described in the results. A third of this sample observed scapegoating of Asians for the COVID pandemic, akin to our findings in Theme 4, which contributes to the race-based stress experienced by the Asian community during this time.

The collective blame placed on Asian people for COVID-19 has also resulted in significant negative economic impact (Mar & Ong, 2020). For example, an NPR podcast dated February 26, 2020, discussed the impact of COVID-19 on businesses in San Francisco Chinatown. Despite no confirmed cases at the time, Chinatown’s businesses began suffering early over virus-related fears. Even before shelter-in-place orders were levied, less tourism and fewer people were observed in the typically dense, urban area. In February 2020, Chinatown stores reported seeing a 70%–80% reduction in business even during the Lunar New Year celebration, which usually draws large crowds (Chang, 2020). Similarly, a Los Angeles Times interview dated March 19, 2020, prior to Los Angeles county issuing its “stay-at-home” order, reported that over a dozen Chinese restaurants had already closed due to lack of business (Garcetti, 2020). Other Asian-owned businesses have been explicitly vandalized with coronavirus-related messages (Peng, 2020).

Limitations

This study is limited due to the absence of empirical literature published on this emerging phenomenon, inhibiting the ability to conduct a systematic review of indexed research articles. As dictated by our choice of qualitative phenomenology, the themes we present are nonexhaustive and should not be taken as such. The possibility of researcher bias is also present, as the same authors who conceptualized the study also conducted the qualitative coding and thematic analysis. The authors used best practices of reflexivity in qualitative research, which understands researchers’ backgrounds as contributing to “richer meanings to the phenomenon under study and clarifies the lenses used to arrive at certain interpretations” (Patnaik, 2013). The generalizability of our themes are also limited as media reports may be biased in many ways, which have also been acknowledged in the previous research utilizing similar methodology (e.g., Glenn et al., 2012). For example, possible biases include underrepresenting the full spectrum of racist incidents that actually occurred, possibly skewing toward more severe or “media-worthy” cases due to readership interest, and may reflect the media outlets’ existing bias (e.g., ranging from conservative to liberal). As this study included only English-language media articles of global events, local perspectives are likely missed. Additionally, this study only includes data from the beginning to 6 months into the pandemic, which limits generalizability of these findings to later stages of the pandemic, as it continues to evolve. Finally, our data on the psychological impact of racist incidents are based on the targets’ self-report to media sources. Therefore, clinical implications of the psychological impact, including intensity and duration of symptoms cannot be determined. Future research is needed that assesses these constructs using representative samples in order to improve generalizability.

Conclusion

With our limitations in mind, our study provides a novel contribution to the literature by initiating the empirical exploration of COVID-19 anti-Asian racism and race-based stress. We synthesize experiences reported in the news media of the racism experienced by the Asian diaspora living in the West in the current COVID-19 era. These targets of racism express feeling hypervigilance, changes in cognitions around safety, depressed mood, avoidance of triggers, and other negative psychological sequelae that have been previously documented in response to experiences of race-based stress and trauma in other non-Asian communities of color (Carter, 2007). In addition, these mental health symptoms are likely exacerbated by the repetitive nature of information transfer through social media (Brown et al., 2021). Our findings may be helpful to mental health care providers treating Asian clients who experience race-based stress and trauma, particularly those whose symptoms have been amplified during COVID.

Timely, empirical research is needed that systematically assesses mental health symptoms experienced by Asian targets of racism during the time of COVID-19 crisis. As the pandemic continues to unfold, collecting data on whether and how public anti-Asian attitudes evolve will also be useful. Treatment development and implementation research following the quantification of the psychosocial impact over time will allow for appropriate distribution of psychological resources to address the COVID-19 race-based stress and trauma affecting Asian communities.

Clinical Impact Statement.

This study used qualitative research methods to explore the phenomenon of COVID-related anti-Asian incidents reported in the media. These incidents contribute to race-based stress and trauma experienced by Asian individuals, highlighting their need for mental health support.

Footnotes

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- A3PCON. (2020, March 19). Stop AAPI Hate. A3PCON—Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council. http://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/stop-aapi-hate/ [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.: DSM–5. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Americans Advancing Justice. (2020, March 20). Stand against hatred. https://www.standagainsthatred.org

- BBC News. (2020a, January 29). Coronavirus: French Asians hit back at racism with ‘I’m not a virus.’ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-51294305

- BBC News. (2020b, March 6). Teens arrested over racist coronavirus attack. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-51771355

- Beaubien J (2020, January 31). Why they’re called ‘wet markets’-and what health risks they might pose. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/01/31/800975655/why-theyre-called-wet-markets-and-what-health-risks-they-might-pose [Google Scholar]

- Bensimon O (2020, March 15). Cops bust suspect accused of coronavirus-related hate crime on Asian man. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/03/14/cops-bust-suspect-in-coronavirus-related-hate-crime-on-asian-man/ [Google Scholar]

- Berelson B (1952). Content analysis in communicative research. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Botsford J [@jabinbotsford]. (2020, March 19). Close up of President @realDonaldTrump Notes Is seen where he crossed out “Corona” and replaced it with “Chinese” virus as [Image attached] [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/jabinbotsford/status/1240701140141879298

- Brin S, & Page L (1998). The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine. CNIS, 30(1–7), 107–117. 10.1016/S0169-7552(98)00110-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ME, Dustman PA, & Barthelemy JJ (2021). Twitter impact on a community trauma: An examination of who, what, and why it radiated. Journal of Community Psychology, 49, 838–853. 10.1002/jcop.22330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Endsley M, Motley D, Shawahin L, & Williams M (2018). Addressing the impact of racism on veterans of color: A race-based stress and trauma intervention. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 748–762. 10.1037/vio0000221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT (2007). Clarification and purpose of the race-based traumatic stress injury model. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 144–154. 10.1177/0011000006295120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CBS. (2020a, March 17). Suspect admits he tried to kill family at Midland Sam’s Club. CBS 7 KOSA-TV. https://www.cbs7.com/content/news/FIRST-ON-CBS7-Suspect-admitted-to-trying-to-kill-family-at-Midland-Sams-Club-affidavit-says-568837371.html [Google Scholar]

- CBS. (2020b, March 15). Three victims released from the hospital following stabbing at Midland Sam’s Club. CBS 7 KOSA-TV. https://www.cbs7.com/content/news/BREAKING-FIRST-ON-CBS7-Stabbing-inside-Midland-Sams-Club-568806781.html [Google Scholar]

- Chang J (2020, February 26). San Francisco Chinatown affected by coronavirus fears, despite no confirmed cases. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2020/02/26/809741251/san-francisco-chinatown-affected-by-coronavirus-fears-despite-no-confirmed-cases [Google Scholar]

- Chengwang L. [@ChengwangL]. (2020, January 28). Je suis Chinois Mais je ne suis pas un virus!! Je sais que tout le monde a peur au virus [Image attached] [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/ChengwangL/status/1222114635878367232

- Chu J [@RepJudyChu]. (2020, April 16). We don’t have a border with China. Also, the fact that you can’t distinguish between China & Chinese AMERICANS puts [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/RepJudyChu/status/1250872656053878786

- Coates M (2020). Covid-19 and the rise of racism. BMJ, 369, m1384. 10.1136/bmj.m1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A (2020, February 21). Woman who recorded racist coronavirus tirade speaks out. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/videos/us/2020/02/21/coronavirus-attacks-viral-video-jiraprapasuke-acfc-full-episode-vpx.cnn [Google Scholar]

- Coste V, & Amiel S (2020, March 2). Coronavirus: France faces ‘epidemic’ of Anti-Asian Racism. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/2020/02/03/coronavirus-france-faces-epidemic-of-anti-asian-racism [Google Scholar]

- Davidsen AS (2013). Phenomenological approaches in psychology and health sciences. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 10(3), 318–339. 10.1080/14780887.2011.608466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, & Kyngäs H (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong TP (2002). The contemporary Asian American experience: Beyond the model minority (2nd ed.) Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Fu C (2020, April 8). An Asian-American doctor on the challenges of the coronavirus pandemic. TIME; https://time.com/collection-post/5816886/asian-american-doctor-coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- Garcetti E (2020, March 19). City of Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti: Public order under city of Los Angeles emergency authority. https://www.lamayor.org/sites/g/files/wph446/f/article/files/SAFER_AT_HOME_ORDER2020.03.19.pdf

- Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, & Bound J (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826–833. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy R (2020, March 20). Nurses on coronavirus frontline facing ‘abhorrent’ abuse from public. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/coronavirus/nurses-fighting-coronavirus-facing-abhorrent-abuse-from-public-20-03-2020/ [Google Scholar]

- Glenn NM, Champion CC, & Spence JC (2012). Qualitative content analysis of online news media coverage of weight loss surgery and related reader comments. Clinical Obesity, 2(5–6), 125–131. 10.1111/cob.12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostanian A, Ciechalski S, & Abdelkader R (2020, February 11). Asians worldwide share examples of coronavirus-related xenophobia on social media. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/asians-worldwide-share-examples-coronavirus-related-xenophobia-social-media-n1132036 [Google Scholar]

- Henry J, & Bensimon O (2020, March 14). Victim of possible coronavirus hate crime in Queens speaks out. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/03/14/victim-of-possible-coronavirus-hate-crime-in-queens-speaks-out/ [Google Scholar]

- Houshmand S, Spanierman LB, & Tafarodi RW (2014). Excluded and avoided: Racial microaggressions targeting Asian international students in Canada. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(3), 377–388. 10.1037/a0035404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Berg J, & Yi J (2020). New Center for Public Integrity/Ipsos Poll finds most Americans say the coronavirus pandemic is a natural disaster. Ipsos. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/center-for-public-integrity-poll-2020 [Google Scholar]

- Jiraprapasuke T [@TannyRJ]. (2020a, February 4). Second part of coronavirus rant #IAmNotAVirus [Video attached] [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/TannyRJ/status/1224931693049499648

- Jiraprapasuke T [@TannyRJ]. (2020b, February 4). Video shot by@autumnlovevogue. Happened on 2/1/2020. Headed home with a friend. He directed his coronavirus rant at me for 15 [Video attached] [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/tannyrj/status/1224929040022159361

- Kaci M [@Mkacitv5m]. (2020, January 29). #JeNeSuisPasUnVirus Report-age @TV5MONDE @koimagazinefr [Video attached] [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/MKACITV5M/status/1222601762353373185

- Kaefer F, Roper J, & Sinha P (2015). A software-assisted qualitative content analysis of news articles: Example and reflections. Forum Qualitative Social Research, 16(2), 8. 10.17169/fqs-16.2.2123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kambhampaty AP, & Sakaguchi H (2020, June 25). Asian Americans share experiences of racism during COVID-19. TIME. https://time.com/5858649/racism-coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- Knowles G (2020, May 3). Chinese markets are still selling bats. Daily Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8163761/Chinese-markets-selling-bats.html [Google Scholar]

- Lee BY (2020, February 18). How COVID-19 coronavirus is uncovering Anti-Asian Racism. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2020/02/18/how-covid-19-coronavirus-is-uncovering-anti-asian-racism/ [Google Scholar]

- Li YT (2019). “It’s not discrimination”: Chinese migrant workers’ perceptions of and reactions to racial microaggressions in Australia. Sociological Perspectives, 62(4), 554–571. 10.1177/0731121419826583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C [@ChrisLu44]. (2020, April 16). Most major U.S. cities have a Chinatown. Chinese Americans live there, as do Americans of all races and ethnicities [Image attached] [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/ChrisLu44/status/1250875306967273475

- Mar D, & Ong P (2020, July 20). COVID-19’s employment disruptions to Asian Americans. UCLA Asian American Studies Center. http://www.aasc.ucla.edu/resources/policyreports/COVID19_Employment_CNK-AASC_072020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Margolin J (2020, March 27). FBI warns of potential surge in hate crimes against Asian Americans amid coronavirus. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/U.S./fbi-warns-potential-surge-hate-crimes-asian-americans/story?id=69831920 [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, & Huberman AM (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mok J (2020, March 2). The spread of coronavirus has resulted in panic across the world — with people debating as to the severity of [Thumb-nail with link attached] [Facebook post]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/jaidanmok/posts/10158209158373713

- Myers SL (2020, January 25). China’s omnivorous markets are in the eye of a lethal outbreak once again. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/25/world/asia/china-markets-coronavirus-sars.html [Google Scholar]

- Nadal K (2019). The Brown Asian American movement: Advocating for South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Filipino American communities. Asian American Policy Review, 29, 2–95. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Skolnik A, & Wong Y (2012). Interpersonal and systemic microaggressions toward transgender people: implications for counseling. Journal of LGBTQ Issues in Counseling, 6(1), 55–82. 10.1080/15538605.2012.648583 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura D (2020, June 24). With ‘kung flu,’ Trump sparks backlash over racist language—and a rallying cry for supporters. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/with-kung-flu-trump-sparks-backlash-over-racist-language-and-a-rallying-cry-for-supporters/2020/06/24/485d151e-b620-11ea-aca5-ebb63d27e1ff_story.html [Google Scholar]

- Natividad I (2020, April 9). Racist harassment of Asian health care workers won’t cure coronavirus. Berkeley News. https://news.berkeley.edu/2020/04/09/racist-harassment-of-asian-health-care-workers-wont-cure-coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- Nazroo JY, Bhui KS, & Rhodes J (2020). Where next for understanding race/ethnic inequalities in severe mental illness? Structural, interpersonal and institutional racism. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(2), 262–276. 10.1111/1467-9566.13001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, & Varpio L (2019). How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), 90–97. 10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor C, & Joffe H (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. 10.1177/1609406919899220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Page J (2020, January 26). Virus sparks soul-searching over China’s wild animal trade. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/virus-sparks-soul-searching-over-chinas-wild-animal-trade-11580055290 [Google Scholar]

- Palaganas E, Sanchez M, Molintas MVP, & Caricativo R (2017). Reflexivity in Qualitative Research: A Journey of Learning. Qualitative Report, 22, 426–438. 10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer J (2020, January 27). Don’t blame bat soup for the coronavirus. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/01/27/coronavirus-covid19-dont-blame-bat-soup-for-the-virus/. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik E (2013). Reflexivity: Situating the researcher in qualitative research. Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(2), 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Peng S (2020, April 10). Smashed windows and racist graffiti: Vandals target Asian Americans amid coronavirus. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/smashed-windows-racist-graffiti-vandals-target-asian-americans-amid-coronavirus-n1180556 [Google Scholar]

- Phelan AL, Katz R, & Gostin LO (2020). The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: Challenges for global health governance. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(8), 709–710. 10.1001/jama.2020.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poussaint AF (2002). Yes: It can be a delusional symptom of psychotic disorders. The Western Journal of Medicine, 176(1), 4. 10.1136/ewjm.176.1.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaichon R (2020, March 15). Yesterday I was racially abused [Facebook]. https://www.facebook.com/Republic.of.reizel/videos/3422010924482474/

- Rajagopalan M (2020, March 4). Men yelling “Chinese” tried to punch her off her bike. She’s the latest victim of racist attacks linked to coronavirus BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/megharacoronavirus-racism-europe-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- Sandleben T (2020, February 14). Asian man turned away from Michiana hotels due to coronavirus concerns. ABC 57. https://www.abc57.com/news/asian-man-turned-away-from-michiana-hotels-due-to-coronavirus-concerns [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Burroughs H & Jinks C (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology, 52(4), 1893–1907. 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolworthy J (2020, March 5). Vietnamese curator banned from U.K. event after being told ‘Asians’ are seen as coronavirus carriers The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/news/coronavirus-affordable-arts-fair-an-nguyen-asian-vietnamese-battersea-a9378481.html [Google Scholar]

- Subramani S (2019). Practising reflexivity: Ethics, methodology and theory construction. Methodological Innovations, 12(2), 1–17. 10.1177/2059799119863276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Bucceri J, Lin AI, Nadal KL, & Torino GC (2007). Racial microaggressions and the Asian American experience. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(1), 72–81. 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AM, Nadal KL, & Esquilin M (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasdemir A, & Kus Z (2011). The content analysis of the news in the national papers concerning the renewed primary curriculum. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 11(1), 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Trump D [@realDonaldTrump]. (2020a, April 16). Crazy Nancy Pelosi deleted this from her Twitter Account. She wanted everyone to pack into Chinatown long after I [Video Attached] [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/1250852583318736896

- Trump D [@realDonaldTrump]. (2020b, March 10). Going up fast. We need the wall more than ever! [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1237334397172490240

- Trump D [@realDonaldTrump]. (2020c, March 16). The United States will be powerfully supporting those industries, like airlines and others, that are particularly affected by the [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1239685852093169664

- Wahlquist C, & Australian Associated Press. (2020, February 26). Doctors and nurses at Melbourne hospital racially abused over coronavirus panic. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/27/doctors-and-nurses-at-melbourne-hospital-racially-abused-over-coronavirus-panic [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2008). WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health -Final Report. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/

- WHO. (2020a, May 14). COVID-19 Situation Reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports

- WHO. (2020b, March 18). WHO @WHO. Twitter Periscope. https://www.pscp.tv/WHO/1ypKdQPYELoGW [Google Scholar]

- WHO. [@WHO]. (2020c, March 2). World Health Organization (WHO) on Twitter: ‘When talking about #COVID19, certain words & language may have a negative [Video attached] [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/who/status/1234597035275362309?ref_url=https%3a%2f%2fthehill.com%2fhomenews%2fadministration%2f488479-who-official-warns-against-calling-it-chinese-virus-says-there-is-no.

- Williams M, Pereira DP, & DeLapp R (2018). Assessing racial trauma with the trauma symptoms of discrimination scale. Psychology of Violence, 8, 735–747. 10.1037/vio0000212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong B (2020, May 14). Asian American doctors created a video to challenge COVID-19 racism. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/asian-american-doctors-video-covid-19racism_n_5ebd8cd5c5b62f5c3026ecb4?ncid=fcbklnkushpmg00000098 [Google Scholar]

- Yakas B (2020, March 13). Asian man says NYC cops didn’t care he was spat on in coronavirus-related incident. Gothamist. https://gothamist.com/news/asian-coronavirus-hate-crime-assault-penn-station [Google Scholar]

- Yam K (2020, April 16). Trump appears to equate Chinatown with China. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/trump-appears-equate-chinatown-china-n1185796 [Google Scholar]

- Yi S (2020, April 21). I’m an Asian American doctor on the front lines of two wars: Coronavirus and racism. The Lily. https://www.thelily.com/im-an-asian-american-doctor-on-the-front-lines-of-two-wars-coronavirus-and-racism/ [Google Scholar]

- Zade H, Drouhard M, Chinch B, Gan L, & Aragon C (2018). Conceptualizing disagreement in qualitative coding. Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 159, 1–11. 10.1145/3173574.3173733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L (2020, April 21). How the coronavirus is surfacing America’s deep-seated anti-Asian biases. Vox. https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/4/21/21221007/anti-asian-racism-coronavirus [Google Scholar]