Abstract

Cancer is serious endangers human life. After a long period of research and accumulation, people's understanding of cancer and the corresponding treatment methods are constantly developing. p53 is an important tumor suppressor gene. With the more in-depth understanding of the structure and function of p53, the more importance of this tumor suppressor gene is realized in the process of inhibiting tumor formation. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are important regulatory molecules with a length of about 22nucleotides (nt), which belong to non-coding RNA and play an important role in the occurrence and development of tumors. miR-34 is currently considered to be a master regulator of tumor suppression. The positive feedback regulatory network formed by p53 and miR-34 can inhibit the growth and metastasis of tumor cells and inhibit tumor stem cells. This review focuses on the latest progress of p53/miR-34 regulatory network, and discusses its application in tumor diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: miR-34, p53, Signaling pathway, Tumor

1. Introduction

Cancer has become a major threat to human health. In 2020, the number of lung cancer deaths was 1.8 million, accounting for 18% of the world's cancer deaths, ranking the first and far exceeding the cancer ranked behind [1]. Based on the latest data from the National Cancer Center, the number of new cancer cases in China in 2016 was 4.064 million, and the number of new deaths was 2.414 million. Among them, lung cancer is the cancer with the highest number of new cases in China, accounting for about 20.4% of the total new cases in men and women [2]. At present, there are many methods to treat cancer, among which the most widely used are three traditional therapies: surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. However, the traditional therapies have serious toxic and side effects. The situation of most cancers after treatment is not optimistic, including surgical trauma, damage to normal cells caused by radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and long-term chemotherapy is easy to produce drug resistance [3]. With the advent of the era of “precision medicine”, targeted drug therapy has guided the “post-chemotherapeutic era” that specifically eliminates cancer cells. Among the targeted drug studies, clinically more target-inhibitory drugs are focused on kinases in tumor-related pathways such as human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In addition, there are membrane protein molecules specific to cancer cell surface represented by cluster of differentiation −20 (CD20) and programmed death-1/programmed death ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1), cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3) and other immune escape related molecules. The high specificity of small molecule inhibitors such as kinase inhibitors and signaling pathway key protein inhibitors reduces the toxic and side effects on non-tumor tissues, and enriches all killing resources of tumors to focus on local tumors. For example, gefitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of EGFR, is a clinically effective drug for treating sensitive mutations of EGFR in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, after using these drugs for 1–2 years, most patients gradually developed drug resistance, which affected the therapeutic effect and ended in failure [[4], [5], [6]]. The occurrence of tumor involves the abnormality of multiple signal pathways. Therefore, the searches for new targets in cancer treatment and the resistance of antitumor drugs are the main problems to be solved urgently.

Non-coding RNA (nc RNA) refers to RNA molecules that are transcribed from genome and do not encode protein, including long-chain non-coding RNA and small-chain non-coding RNA. NcRNAs are involved in the regulation of pathways related to tumor suppression and occurrence. Micro RNA (miRNA) is a kind of conserved, non-coding single-stranded RNA which widely exists in eukaryotes and consists of 18–23 nucleotides. MiRNA is highly conserved in evolution. It can recognize the binding site of the target gene mRNA 3′-UTR, and play the role of transcription inhibition or cutting or degradation of mRNA, thus inhibiting the expression of downstream genes and weakening or eliminating the function of downstream genes. Studies have shown that miRNA is closely related to tumor. p53 is an important tumor suppressor gene which responds to DNA damage and cell stress. In this article, we will review progress of miR-34/p53 axis on tumorigenesis.

1.1. p53 and cancer treatment

In 1979, Lionel Crawford and other researchers from the British Cancer Research Foundation and Princeton University first tracked the trace of p53 [7]. Up to now, the researches on p53 have gone more than 40 years [8]. TP53 located on human 17p13.1 chromosome, is encoded by TP53 (tumor protein 53), which consists of 393 amino acid residues, molecular weight 53 kD.p53 protein is a typical transcription factor, its transcriptional activation domain is located in the amino terminal, the DNA binding domain is located in the middle of the peptide chain, and the carboxyl terminal contains nuclear localization signal and tetramerization domain. The half-life of wild-type p53 protein in cells is only 15–30min.p53 protein is mainly distributed in the nucleus and cytoplasm, and can specifically bind to the promoter of target gene. Its activity and stability are regulated by post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination and methylation. Under normal physiological conditions, the intracellular level of p53 protein is low, and it is mainly located in the cytoplasm. When cells are subjected to stress such as hypoxia and DNA damage, p53 protein rapidly accumulates and activates in the cell, regulating the transcription of a series of genes, leading to cell cycle arrest, apoptosis or senescence, thus avoiding cell carcinogenesis. Studies have shown that p53 can inhibit the cell cycle process in many ways, one of which is up-regulating the expression of downstream gene p21. Subsequently, p21 protein bound to cyclins E/Cdk2 and D/Cdk4, resulting in cell cycle G1 arrest [9].

When the anti-tumor function of p53 is lost, it will promote the proliferation of tumor cells and inhibit the apoptosis of tumor cells. Studies have shown that TP53 gene mutation is the main mechanism of p53 inactivation, and more than 50% of cancers are accompanied by mutation of p53 [10]. The main types of mutations in p53 include missense mutations, truncation mutations, in-frame mutations and splicing mutations. Missense mutations result in single amino acid substitutions that show function-enhancing activity during tumourigenesis, such as the p53 R175H and R273H mutations that promote tumour cell invasion and migration. Truncating mutations lead to protein truncation, which can also promote tumour development. For example, the p53 exon 6 truncation mutants R196* and R213* promote proliferation and metastasis of tumour cells [11]. In-frame mutations are caused by deletions or insertions of nucleotides. Splice mutations are caused by mutations that occur at the splice site. Approximately 80% of p53 mutations are missense mutations. It is mainly located in exons 5–8 of the coding DNA binding domain, with the most common mutation sites occurring in R175, G245, R248, R249, R273 and R282 [12]. Thus, different p53 mutation types are caused by different mechanisms and contribute to the malignant development of tumors. Malhotra et al. have established consistent conclusions regarding the carcinogenic function of mutant p53 in various cancers through multi-omics studies. Omics-based studies have emphasized the importance of p53 in the processing of colon cancer miRNA and determined the carcinogenic effect of mutp53 R273H in colon cancer cells [13]. In addition, in tumors without TP53 gene mutation, the function of wild-type p53 is regulated by other proteins or non-coding RNA, and is often inactivated due to the down-regulation of positive regulators or up-regulation of negative regulators. The research conducted by Shi L et al. showed that TP53 and LRP1B were key genes for regulating the immunophenotype of hepatocellular carcinoma through EPCAM [14]. Our laboratory Wang et al. confirmed that p53 was a direct target of miR-150, and the overexpression of p53 promoted the expression of suppressor miRNAs such as miR-34a, miR-184, miR-181a and miR-148 [15]. Recent studies have confirmed that a variety of small molecular compounds and polypeptide drugs can restore the wild-type activity of p53 mutant by mutagenizing its spatial conformation and folding, or inhibit its carcinogenic activity by promoting the degradation of p53 mutant protein, and finally inhibit the tumor growth (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of small molecular compounds and polypeptide drugs on p53.

| Name | Research phase | Clinical indication | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP-31398 | Preclinical | Liver cancer, Colorectal cancer, Endometrial carcinoma | [[16], [17], [18]] |

| PEITC | Preclinical | Oral cancer, Colorectal cancer, Prostate cancer | [[19], [20], [21]] |

| NSC319726 | Preclinical | Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma | [22] |

| COTI-2 | Phase I clinical | Triple-negative breast cancer, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | [23,24] |

| PRIMA-1 | Preclinical | Breast cancer, Esophageal cancer | [25] |

| ReACp53 | Preclinical | Ovarian cancer | [26] |

| Ganetespib (STA-9090) | Phase Ⅱ clinical | Lung cancer, Ovarian cancer, Prostate cancer | [27,28] |

| APR-246 (Eprenetapopt) | Preclinical | Neuroblastoma | [29] |

2. miR-34 family

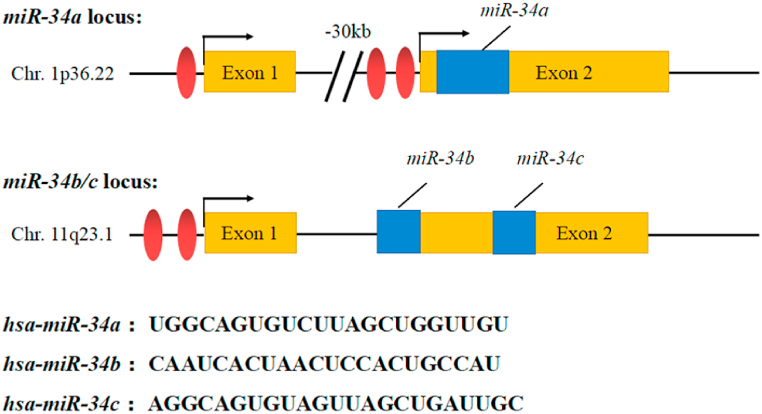

miR-34 family includes miR-34a, miR-34b and miR-34c, which are encoded by two different genes in human body [30,31]. Among them, miR-34a is one of the most studied miRNA, which is located on chromosome 1p36.22 and encoded by its own transcript, while miR-34b and miR-34c are co-located on chromosome 11q23.1 as a gene cluster and co-transcribed and expressed. Genetic structure prediction results indicated that the coding sequence of miR-34a is located in exon 2 of the transcription precursor and this position is ∼30 kb downstream of exon 1 of the transcription precursor. Meanwhile, the coding sequences of miR-34b and miR-34c are located in intron 1 and exon 2, respectively (Fig. 1). miR-34 is highly conserved and stably expressed in the process of biological evolution, which negatively regulates the protein expression of target genes by combining with the complementary sequence of 3′UTR of target mRNA [32]. Li et al. predicted a total of 512 putative targets for miR-34a/b/c from multiple miRNA databases. These targets were further analysed in the gene ontology (GO), KEGG pathway and responseome pathway datasets. The results suggest that they are involved in the regulation of signal transduction, macromolecular metabolism and protein modifications. In addition, these targets are involved in key signaling pathways such as MAPK, Notch, Wnt, PI3K/AKT, p53 and Ras, as well as apoptosis, cell cycle and EMT-related pathways [33]. Many studies have found that miR-34 family members are the direct targets of p53 [34,35]. miR-34 is the first miRNA that is directly regulated by tumor suppressor gene p53. It has been found that miR-34 has low expression in many kinds of tumor cells, and plays an important role in tumor diagnosis, treatment, drug resistance and prognosis, so it can inhibit the occurrence and development of tumor [36].

Fig. 1.

Gene localization and mature structural sequence of miR-34 family.

In our study, we found that the overexpression of miR-34a inhibited the proliferation and promoted the apoptosis of NSCLC cells in vitro by directly targeting TFβR2, which played an oncogene role in non-small cell lung cancer [37]. And we showed that in NSCLC cell lines A549, SPC-A1 and HCC827 (EGFR mutation), miR-34a inhibited the growth and metastasis of NSCLC by directly targeting EGFR, thus exerting its tumor inhibitory effect [38].

Abnormal expression of miR-34 is detected in a variety of tumors, and it is also the first miRNA confirmed to be directly regulated by the tumor suppressor gene p53, thus inhibiting the occurrence and development of tumors. Studies have found that the expression level of miR-34a in most human organs and tissues is higher than that of miR-34b and miR-34c [39]. As a tumor suppressor gene, miR-34a has low expression in many tumor tissues such as prostate cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, cervical cancer, and is associated with poor prognosis, which is expected to be used as an indicator for tumor prevention, diagnosis, and prognosis evaluation [40,41]. While miR-34b/c has been proved to play an important role in brain development [42].

3. The function of p53/miR-34 axis in cancer

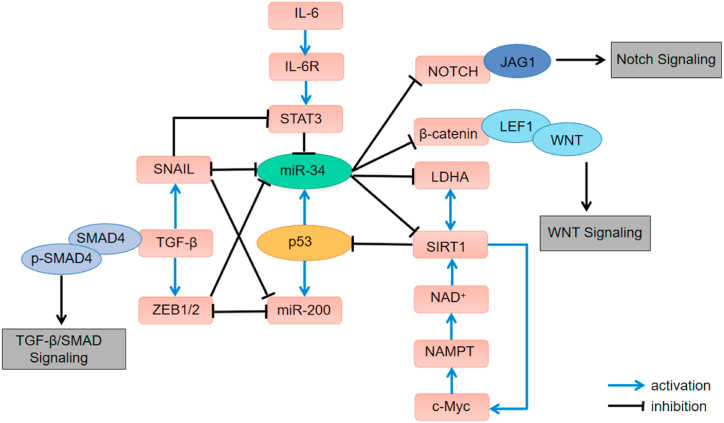

miR-34 is also regulated by p53, and the extended inhibitory effect of p53 on tumor is targets via miR-34 family (Fig. 2). miR-34a is an important molecule in tumor inhibition, and participates in the regulation of the occurrence and development of various cancers, including proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion, metabolism, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and so on, thus inhibiting the growth and metastasis of tumors [43].

Fig. 2.

Feedback loops involving p53/miR-34.

When cells are subjected to some stimuli, such as DNA damage and drug stimulation, the expression of p53 will be activated to cope with the stimuli. p53 demethylates the promoter region of CpG island of miR-34a, activates the expression of miR-34a, and then regulates the target gene of miR-34a. Shi et al. showed that p53 protein had a direct targeted regulation on the expression of miR-34a [44]. In addition, there were indirect regulatory factors that affect the expression of p53 and miR-34a, such as silencing information regulator related enzyme 1 (SIRT1), which is a NAD+-dependent deacetylase [45]. When it inhibited the post-transcriptional deacetylation of p53 protein, the activity of p53 protein was down-regulated. MiR-34a can induce the activity of p53 by inhibiting the expression of SIRT1 [46,47].

3.1. Cell cycle

Studies on many tumors have shown that abnormal expression of miR-34a can inhibit the expression of CDK4 and CDK6, thus promoting the progress of cell cycle [48]. Xu et al. [49] showed that p53 promoted the expression of miR-34a, which promoted the process of cell cycle via targeting E2F transcription factor 3 (E2F3). In addition, Wang et al. [50] also reported that miR-34a inhibited MAP2K1, an important member of the MEK/ERK signal pathway, and thus arrested cell cycle. Furthermore, miR-34a targeted nicotinamide phosphoribosyl-transferase (NAMPT), which is the key speed-limiting enzyme of NAD+ remediation pathway, thereby regulating the activity of SIRT1 [51]. Fan et al. [52] revealed that SIRT1 and c-MYC regulated each other through a positive feedback loop. At the same time, miR-34a inhibited the c-MYC/SIRT1 pathway, thereby activating p53 and then up-regulating the expression of miR-34a [53].

3.2. Cell apoptosis

miR-34 plays an important role in promoting apoptosis in many cancers [54]. miR-34a had been proved to target anti-apoptotic gene c-Myc [55], Bcl-2 and induced cell apoptosis [56]. In NSCLC the expression of PDGFR was negatively correlated with miR-34a. Overexpression of miR-34a leaded to down-regulation of PDGFR expression, which in turn promoted apoptosis of cancer cells [57]. Death receptor CD95 has the function of promoting apoptosis. Meanwhile, CD95 was also one of the target genes of p53. miR-34a and CD95 responded to p53 at the same time. The expression of CD95 can affect the activation of p53 and the ability of p53 to regulate miR-34a [58].

3.3. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

EMT plays a promoting role in the tumorigenesis [59]. miR-34a directly inhibited EMT-induced transcription factor SNAIL, and then inhibited EMT process [60]. p53 protein played a key role in cellular plasticity by targeting miR-34a and miR-200 families to regulate EMT pathway and its relative MET pathway. The p53, miR-34a and miR-200 families form two double negative feedback loops with SNAIL, zinc finger e-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) and zinc finger e-box binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2). The combination of ZEB1 and SNAIL with the E-box of miR-34a promoter inhibited the expression of miR-34a, which further increases the relationship between the two circuits of miR34a/SNAIL and miR-200/ZEB [61]. The zinc finger protein 281 (ZNF281), the product of miR-34a target gene, was co-regulated by SNAIL and miR-34a.Therefore, the expression of ZNF281 was regulated by miR-34a and SNAIL related circuits. On the one hand, miR-34a indirectly inhibited its expression; On the other hand, SNAIL directly induced the expression of ZNF281 [62].

3.4. Migration and invasion pathways

The abnormal expression of miR-34a affected tumor deterioration and migration, and tumor metastasis occurs in primary cancer patients with low expression of miR-34a, which revealed that miR-34a played an important role in inhibiting tumor metastasis [63,64]. In the mouse experiment, overexpression of miR-34a could inhibit the formation of metastatic tumor. In vivo experiments showed that stable overexpression of miR-34a could significantly reduce the metastasis of breast cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer and osteosarcoma cells. Many studies have shown that miR-34a inhibited the migration and invasion of cancer cells by directly regulating target genes, such as AXL, PDGFR-α/β and c-Met. A recent study showed that when rectal cancer cells were cultured in a medium containing interleukin-6 (IL-6), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, STAT3) can directly inhibit the expression of miR-34a.IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a loop mechanism, that is, there is a positive and negative feedback regulation pathway among interleukin 6 receptor (IL-6R), STAT3 and miR-34a [65]. The activation of this pathway was associated with the invasion and migration of primary rectal tumors and rectal cancers.

3.5. Glucose metabolism of cancer

miR-34a mediated the inhibition of hexokinase 1 (HK1), hexokinase 2 (HK2), glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK1), thereby inhibiting glycolysis and enhancing mitochondrial respiration. p53 regulated glycolysis and glucose metabolism through miR-34a-mediated inhibition of these enzymes. Lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) catalyzed the conversion of pyruvate to lactic acid, which played a key role in anaerobic glycolysis. Huang et al. proved that LDHA was the target site of miR-34a [66]. SIRT1 was regulated by LDHA. At the same time, inhibition of SIRT1 expression also resulted in down-regulation of LDHA transcription.

3.6. Cancer stem cells

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) have the characteristics of stem cells. Liu et al. showed that the expression of miR-34a in prostate cancer stem cells was significantly down-regulated, while up-regulation of miR-34a expression inhibited tumor regeneration and metastasis in CD44+ group [67]. miR-34a also played an important role in rectal cancer stem cells. Up-regulation or down-regulation of miR-34a expression affected the CSCs-related signal pathway mediated by miR-34a target gene Notch1 [68], thus changing the balance between self-renewal and differentiation of CSCs.miR-34a can not only regulate the Notch signal pathway, but also directly inhibit the ligand Dll1 (Delta-like ligand 1) of Notch. Through this mechanism, miR-34a can inhibit the proliferation, migration and invasion of choriocarcinoma cells and the growth of xenografted tumors. In mesothelioma, p53/miR-34 regulatory network is closely related to the proliferation of CSC. When p53 or miR-34a is down-regulated, the expression of c-Met was up-regulated, thus promoting the proliferation of CSC [69]. At the same time, its ability of migration and invasion has also been enhanced.

4. The relationship of miR-34 and cancer

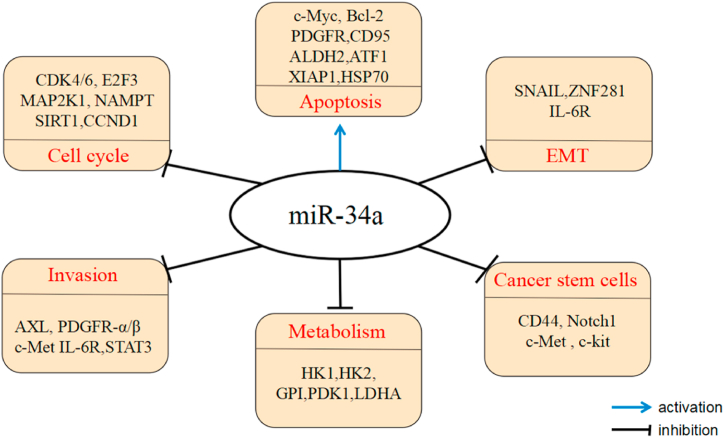

At present, miR-34a is closely related to the occurrence of various tumors and is likely to be a tumor suppressor gene of various tumors (Fig. 3). Meta-analysis showed that in gastrointestinal cancer (GIC) patients, the low expression of miR-34a was significantly related to worse odds ratio (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS)/progression-free survival (PFS)/recurrence-free survival (RFS), and the decreased expression level of miR-34a was related to poor tumor differentiation and late TNM stage. MiR-34a may become a new factor for prognosis prediction and progress of GICs [70].

Fig. 3.

miR-34a regulates cancer-revelated pathways and processes by targeting key factors.

4.1. miR-34 in lung cancer

Lung cancer is a malignant tumor originating from the bronchial mucosal epithelium or glands, and the incidence and mortality of lung cancer are among the highest in the Chinese, which is a serious threat to life and health. Among them, NSCLC is the most common in clinic, accounting for 80%–85% of the total number of patients with lung cancer [71]. Therapeutic measures such as surgery, chemoradiotherapy and molecular targeted drugs can greatly improve the prognosis of patients with NSCLC, but the therapeutic benefits are severely reduced due to the resistance of lung cancer cells to chemotherapy and molecular targeted drugs. Therefore, how to antagonize drug resistance of NSCLC has become an important topic of clinical attention and research in recent years.

miR-34 was low-expressed in NSCLC and exerted anti-cancer effects by regulating biological processes such as proliferation, metastasis, invasion and apoptosis of NSCLC cells [72]. In addition, miR-34 antagonized the drug resistance of NSCLC by inhibiting EMT, improving the imbalance of anti-apoptotic mechanisms, regulating tumor stem cells, and cooperating against drug resistance and specific signaling pathways [73]. Feng et al. demonstrated that miR-34b-3p might act as a tumor suppressor in NSCLC by targeting CDK4 [74]. The research results of Lin et al. showed that RBM38 in NSCLC cell line regulated SIRT1 by regulating the expression of miR-34a under hypoxic conditions, thus playing the role of oncogene [75]. In addition, Wang J et al. demonstrated that has-circRNA-002178 could induce T-cell exhaustion by enhancing PDL1 expression by sponge adsorption of miR-34 in lung adenocarcinoma cells [76]. Therefore, in-depth study of miR-34 will help to further deepen the understanding of lung cancer and clarify the mechanism of occurrence, development and drug resistance of miR-34 in lung cancer, providing new ideas for clinical prevention and treatment of lung cancer.

4.2. miR-34 in ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer is one of the common tumors in female reproductive organs [77]. Due to the lack of obvious symptoms in the early stage, most of them are in the advanced stage when discovered, and the ovary has a special shape, the growth site of malignant tumors is extremely hidden, which leads to a high mortality rate and seriously endangers the life and health of women [78]. At present, surgery combined with chemoradiotherapy is often used in clinical treatment of ovarian cancer, but it has severe side effects and seriously reduces the quality of life of patients after surgery. Therefore, exploring specific markers for early diagnosis of ovarian cancer is of great significance to improve the therapeutic effect and improve the prognosis of patients.

Recent studies have pointed out that the expression of miR-34 is related to the disease progression of ovarian cancer patients, and may participate in the development process of ovarian cancer [79]. Jia et al. found that miR-34 inhibited the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells by triggering autophagy and apoptosis, and inhibited cell invasion by targeting Notch 1 [80].

4.3. miR-34 in hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common malignant tumor in the world and the third leading cause of cancer-related death [81]. At present, surgical resection is still the preferred treatment for HCC. However, due to the unobvious early symptoms of HCC, many patients are in the advanced stage at present, resulting in poor effect of surgical treatment. The recurrence rate is as high as 50% two years after surgery, and the five-year survival rate is only about 10% [82]. Therefore, it is of great significance to find new therapeutic strategies for HCC and deeply explore its molecular mechanisms.

miRNAs play an important regulatory role in the occurrence and malignant transformation of HCC. Many studies have reported the abnormal expression of miR-34 in HCC. The research of Feili et al. showed that the expression of miR-34a-5p was significantly reduced in HCC patients, and the overexpression of miR-34 could improve the occurrence and development of liver fibrosis by targeting Smad4 and regulating TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway [83]. Qi et al. found that miR-34a was predicted to target Lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and that Indole-3-carbinol (I3C) down-regulated its expression. Furthermore, I3C inhibited the degradation of p53 by MDM2 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, and stable p53 induced miR-34a. I3C regulated the expression of LDHA, a key enzyme in aerobic glycolysis, in a p53-dependent manner via miR-34a, suggesting that cancer metabolism is an important target of I3C in hepatocellular carcinoma cells [84]. Zhao et al. found that miR-34a-5p was significantly downregulated in HCC radiation-resistant cells and that c-MYC was a direct target of miR-34a-5p. miR-34a-5p overexpression reversed c-MYC-induced radio resistance, counteracted the cancer stem cell (CSC) properties of HCC, and enhanced the radiosensitivity of HCC [85]. Among various tumors, p53 is a tumor suppressor gene with a broad and powerful function. However, Makino et al. proposed a new mechanism for the occurrence of liver cancer. p53 activated in stem cells of patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) can create a microenvironment that supports the formation of tumors by hepatic progenitor cells (HPC), whose expression is positively correlated with the level of apoptosis, the expression of genes related to sentinel-associated secret Phenotype (SASP), HPC related genes, and later cancer development [86].

MiR-34a is highly methylated in HCC. Li et al. demonstrated that miR-34a inhibit the occurrence of HCC by up-regulating palmitoyl membrane palmitoylated protein (MPP2). Essentially, the miR-34a methylation site is located upstream of its binding site to p53. After demethylation, the expression level of miR-34a was up-regulated, which promoted the expressions of MPP2, caspase9, caspase3, E-cadherin and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2)-associated X protein, and inhibited cell proliferation, migration and invasion [87]. Therefore, it is of great significance to study the effect of methylation/demethylation of miR-34a on the expression of upstream regulatory factors such as p53 and explore its function. As the most famous tumor suppressor gene, p53 can promote the occurrence of HCC. These results suggest that p53 is a potential therapeutic target for cancer prevention in patients with chronic liver disease.

4.4. miR-34 in other cancers

p53 mutation often occur in many cancers. p53 mutation was found in approximately 50% of cases of colorectal cancer. Yang et al. reported for the first time that leucine-rich pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein (LRPPRC) was a key functional downstream target for p53 mutation leading to resistance in colorectal cancer. Due to its RNA binding function, LRPPRC could specifically bind to the multidrug resistance 1 (MDR1), increasing the stability of the MDR1 and protein expression. In mutant p53 cells, the p53/miR-34a/LRPPC/MDR1 signaling pathway was reversely activated, leading to the accumulation of LRPPC and MDR1 proteins and promoting chemotherapy resistance of colorectal cancer. However, silent LRPPC showed great potential for reversing p53-induced chemotherapy resistance of colorectal cancer [88]. Feng et al. found that apatinib up-regulated miR-34a-5p and down-regulated HOXA13 in synovial sarcoma cells, which led to a significant decline in the proliferation, migration and invasion of SW982 cells, promoted apoptosis and inhibited tumorigenesis [89]. Gu et al. showed that miR-34b-5p, as a tumor suppressor, inhibited the proliferation, migration and invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells. At the same time, circBFAR acted as a miR-34b-5p sponge in PDAC, thus up-regulating the expression level of mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (MET), further activating the MET/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, and finally promoting the occurrence and development of PDAC cells [90]. In addition, miR-34 b/c-5p was a tumor suppressor in breast cancer. Zhang et al. found that miR-34 b/c-5p inhibited the growth of breast cancer cells mainly by targeting neurokinin −1 receptor (NK1R) [91].

5. miR-34/p53 and noncoding RNAs

miR-34, with its important regulatory effects on cell cycle, proliferation and apoptosis, has been widely studied in the field of cancer. miR-34 can also act on various major cells related to inflammation and aging through a similar mechanism. Srinivasan et al. found that miR-34 was a modifier of brain aging and neurodegeneration. The miR-34 mutant showed the characteristics of early aging, including shortened life span, neurodegeneration and accumulation of inhibitory histone marker H3K27me3. In addition, it is confirmed that miR-34 regulated the 3′ non-coding region of Lst8, a subunit of Tor Complex 1 (TORC1), and it was determined that Lst8 was a potential target of miR-34 [92]. Tian et al. found that miR-34a-5p was up-regulated in Osteoarthritis (OA). LncRNA SNHG7 regulated Synoviolin 1 (SYVN1) by sponging miR-34a-5p, thereby promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis and autophagy [93]. In addition, research by Wu et al. revealed that LGR4 was a direct target that mediates the pro-inflammatory functions of miR-34a and miR-34c. miR-34-LGR4 axis regulated GSK-3β-induced p65 serine 468 phosphorylation and altered the activity of NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby regulating the inflammatory response of keratinocytes [94].

In addition, the current studies have pointed out that long-chain non-coding RNA (lncRNA) plays an important role in the process of epigenetic regulation, cell cycle regulation, nuclear and cytoplasmic transport, transcription, translation, shearing, and is considered to be a functional RNA that plays an important role in the transcription and post-transcription regulation of gene expression. Different lncRNA has different effects in the process of tumor occurrence and development. Long-chain noncoding RNA lnc-Ip53 was up-regulated in a variety of cancer types, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The research conducted by Zhang et al. showed that lnc-Ip53 inhibited the acetylation of p53 by interacting with histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and E1A binding protein p300, resulting in the loss of p53 activity, thus promoting tumor growth and chemotherapy resistance [95]. The expression of lncRNA NEAT1 is up-regulated in colorectal cancer tissues. Luo et al. found that lncRNA NEAT1, as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNAs), inhibited the expression of miR-34a, and then activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which promoted the proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer cells [96]. LncRNA MALAT1 was overexpressed in melanoma tissues. Li et al. have shown that LncRNA MALAT1, as a miRNA molecular sponge, negatively regulated the level of miR-34a and regulated the expression of c-Myc and Met in melanoma cells [97]. Shree et al. found that LINC01711 functions as a competitive endogenous RNA for miR-34a, promoting ZEB1 expression to regulate invasion [98]. The research of mutual regulation between lncRNA and miR-34a suggested that p53 may act through lncRNA or be influenced by lncRNA. MiR-34a not only regulates lncRNA, but also participates in the signal regulation pathway of miR-34a in turn. The two regulate each other and play an important role in biological functions.

6. p53/miR-34 therapeutics in clinical

A large number of preclinical studies have shown that p53/miR-34 has a broad application prospect in tumor treatment. MRX34, a special amphoteric lipid nanoparticle, belongs to an analogue of miR-34 and is also the first therapeutic drug related to miRNA. The results of a Phase I clinical trial (NCT01829971) evaluating the safety of MRX34 demonstrated that, despite the potential of MRX34 targeted therapy, it was rapidly discontinued due to severe immunotoxicity associated with accidental drug miss-target [99]. Currently, the FDA has not approved any targeted drug for TP53. Gene therapy, targeted tumor vaccines and anticancer drugs against TP53 mutations are in the early stages of clinical trials. The eprenetapopt (APR-246, also known as PRIMA-1MET) developed by Aprea Therapeutics in the United States is a small molecule that has been proved to be able to restore the mutant and inactivated p53 protein to the conformation and function of wild-type p53 to induce programmed cell death in human cancer cells. Phase II clinical study (NCT03588078) results showed that eprenetapopt was safe and had shown strong efficacy in the treatment of patients with TP53-muted myelopathy syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia [100]. PC14586, a p53 activator from PMV Pharma Company, could selectively combine with p53 Y220C mutant protein, thus recovering the normal p53 protein structure and its tumor inhibition function. Phase I/II clinical trials have been started and are being developed to treat patients with advanced solid tumors with p53 Y220C mutation determined by next generation sequencing.

MDM2 (murine double minute 2) is an important ubiquitin ligase in ubiquitination modification of p53. MDM2 ubiquitinated p53 by specifically binding p53, thereby reducing the protein level and transcription activity of p53 [101]. KRT-232, developed by Kartos Therapeutics, is a selective, small molecule inhibitor of interaction with MDM2-p53 that had been shown to be safe in a Phase I clinical trial (NCT02016729) in patients with advanced solid tumors, multiple myeloma, or acute myeloid leukemia [102]. Another small molecule MDM2 inhibitor, APG-115, developed by Yasheng Medicine, had a high binding affinity for MDM2, and could restore the tumor inhibitory activity of p53 by blocking the interaction between MDM2 and p53. It had achieved positive results in phase II clinical trials for patients with unresectable/metastatic melanoma or advanced solid tumors [103]. Although it has been reported that a variety of small molecular compound or polypeptide drugs targeting the mutant p53 have been developed, few drugs have entered clinical trials, and no drug targeting the mutant p53 has been approved for marketing in tumor therapy. Obviously, more studies on mutant p53 are needed in the future.

7. Conclusion and perspective

In summary, the p53/miR-34a regulatory network plays an important role in regulating the occurrence and development of tumors in the signaling pathways in which miR-34a is involved. Through this pathway, miR-34a can directly or indirectly regulate different genes to inhibit the occurrence of tumors or promote apoptosis of tumor cells. Therefore, the regulatory network of p53/miR-34a and cancer have been increasingly studied. Undoubtedly, further study on the relationship between the two is of great significance for revealing the mechanism of tumor occurrence and development. As an important member of p53 regulatory network, miR-34 is not only directly regulated by p53, but also involved in the feedback regulation of p53 pathway by regulating certain genes that regulate p53 activity. On the one hand, p53 can inhibit several proto-oncogenes such as Bcl-2, c-Myc and cytokines such as cyclinE2, cyclinD1 and c-Met through the regulation of miR-34 family, thus exerting oncogenic effects. The miR-34 family can also enhance p53 activity by inhibiting silencing message regulators such as SIRTI. p53 and the miR-34 family form a positive feedback regulatory network that plays an important role in inhibiting tumor development and progression. According to the current research results, miR-34a is low expressed in tissues of cancer patients. At the same time, miR-34a was negatively correlated with tumor stem cells, tumor malignancy, tumor size, and poor prognosis. Therefore, detecting the expression level of miR-34a is of great significance for the prognosis and diagnosis of cancer patients. In terms of chemotherapy resistance, miR-34a can promote the sensitivity of cancer cells to drugs, thus enhancing the efficacy of drugs. miR-34 is widely involved in the occurrence and development of tumors by regulating multiple target genes, which plays an important role in the early diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of tumors. In the United States, analogues of miR-34a have entered phase I clinical trials. The research on miR-34a and its regulatory network is only the beginning. With the deepening of the research, the development and application of new drug targets will not be far off, and it is also the target of accurate tumor medical treatment or personalized treatment.

At present, many studies have shown that miR-34 plays a regulatory role in the immune response. The mutated p53 is found to be immunogenic and can trigger an immune response as a novel antionco. Wang et al. reported that STAT3 is a downstream target of miR-34a and that KCNQ1 overlapping transcript 1(KCNQ1OT1) regulates STAT3 through its role as a miR-34a sponge. Knockdown of KCNQ1OT1 decreased PD-L1 levels, enhanced cytotoxicity and proliferation of CD8+ T cells, and inhibited apoptosis of CD8+ T cells. KCNQ1OT1 inhibited CD8+ T cell function through the miR-34a/STAT3/PD-L1 axis inhibited CD8+ T cell function, thereby promoting immune evasion of melanoma cells [104]. Deng et al. found that p53 inhibited the expression of PD-L1 through miR-34a. MiR-34a inhibited cell activity and migration, and promote apoptosis and cytotoxicity of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [105]. Tsai et al. found that the treatment of bladder cancer (BC) cells with autophagy inhibitors chloroquine (CQ) and bafemycin A1 (Baf-A1) inhibited the expression of hsa-microRNA-34a (miR-34a), and the overexpression of miR-34a in BC cells prevented the expression of PD-L1 induced by autophagy. During the treatment with autophagy inhibitor, the expression of miR-34a and PD-L1 was negatively correlated. In addition, overexpression of miR-34a induces cytotoxicity of natural killer cells to BC cells [106]. Many studies have found that antibodies play a vital role in immunotherapy. P1C1TM is an engineered T-cell receptor-like antibody that distinguishes between mutant p53 expressing HLA-A24+ and wt p53 and mediates antibody-dependent cytotoxicity in cells harboring mutant p53. The combination of P1C1TM and PNU-159682 specifically inhibited tumor growth [107]. H2-scDb is a bispecific antibody that specifically recognizes cancer cells harboring the p53 R175H mutation and efficiently activates T-cells to kill tumor cells in vitro and in vivo [108].

TP53 is a key tumor suppressor gene, which mutates in more than half of human cancers. At present, a large number of studies have found that ferroptosis may be the most important weapon for p53 to inhibit tumor. Gu's team proved that p53 inhibited cystine uptake by inhibiting the expression of SLC7A11 (the key component of cystine/glutamate antiporter protein), and made cells sensitive to ferroptosis [109]. In addition, lipid oxidase ALOX12 was the key regulatory factor of p53-dependent iron death, but SLC7A11 could directly bind to ALOX12 to limit its function. When p53 downregulated SLC7A11, ALOX12 would be released. Free ALOX12 could oxidize the polyunsaturated fatty acid chain of cell membrane phospholipids, leading to ferroptosis of cells [110]. Moreover, iPLA2β was a key regulator of p53 activation-induced iron death under high ROS stress. Meanwhile, p53 induced ferroptosis in a GPX4-independent manner [111]. p53 could induce the expression of SAT1, which promoted the function of ALOX15, another member of the ALOX family, to enhance cellular ferroptosis [112]. The above-mentioned abundant evidence supported the role of p53 in promoting ferroptosis. However, p53 has also been shown to inhibit the occurrence of ferroptosis in some cases. Cell cycle regulatory protein p21 is an important target gene of p53. p21 could inhibit the progress of cell cycle, thus converting part of the raw materials used to synthesize nucleic acid into synthetic reducing NADPH and glutathione, which inhibited the occurrence of ferroptosis [113].

With the in-depth understanding of the structure and function of p53, the importance of this tumor suppressor gene is new light in inhibiting tumor formation. As an important highly mutated tumor suppressor gene, p53 is an attractive therapeutic target for tumor therapy. The study on the combination of p53 and ferroptosis found that p53 could promote ferroptosis of cells in most cases, thus inhibiting tumor. However, many outstanding problems still exist. First of all, p53 mutates in more than 50% of tumors, so what are the factors that affect the type and spectrum of p53 mutation? Secondly, post-translational modification plays an important role in the accumulation of mutant p53. How does post-translational modification work by regulating mutant p53, and what is the specific regulatory mechanism? Thirdly, the current research mainly focuses on the hot spots of p53 mutation. At present, it is uncertain whether p53 mutation with different residues and different functional domains performs the same function acquisition and what is its mechanism. Therefore, in-depth exploration of the regulatory network of p53/miRNA-34 and other non-coding RNA may provide a new idea for treating tumors (especially tumors with p53 mutation), expand the new mechanism of p53 regulating tumor development, and open up a new direction for developing new drugs with tumor inhibition.

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (Grant No. 20S11901300) and Shanghai Huangpu District Scientific Research Project (HLM202106).

Contributor Information

Zhijun Lu, Email: lusamacn@126.com.

Zhongliang Ma, Email: zlma@shu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W., Zheng R., Baade P.D., et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullard A. Addressing cancer's grand challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19(12):825–826. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Y.-L., Zhang L., Kim D.-W., et al. Phase ib/II study of capmatinib (INC280) plus gefitinib after failure of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor therapy in patients with EGFR-mutated, MET factor-dysregulated non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36(31):3101–3109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.7326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen P., Huang H.-P., Wang Y., et al. Curcumin overcome primary gefitinib resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer cells through inducing autophagy-related cell death. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):254. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1234-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duan J., Xu J., Wang Z., et al. Refined stratification based on baseline concomitant mutations and longitudinal circulating tumor DNA monitoring in advanced EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma under gefitinib treatment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020;15(12):1857–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lane D.P., Crawford L.V. T antigen is bound to a host protein in SV40-transformed cells. Nature. 1979;278(5701):261–263. doi: 10.1038/278261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine A.J. p53: 800 million years of evolution and 40 years of discovery. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2020;20(8):471–480. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radine C., Peters D., Reese A., et al. The RNA-binding protein RBM47 is a novel regulator of cell fate decisions by transcriptionally controlling the p53-p21-axis. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27(4):1274–1285. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0414-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabapathy K., Lane D.P. Therapeutic targeting of p53: all mutants are equal, but some mutants are more equal than others. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15(1):13–30. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C., Liu J., Xu D., et al. Gain-of-function mutant p53 in cancer progression and therapy. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;12(9):674–687. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjaa040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akbar R., Ullah K., Rahman T.U., et al. miR-183-5p regulates uterine receptivity and enhances embryo implantation. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2020;64(1):43–52. doi: 10.1530/JME-19-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malhotra L., Singh A., Kaur P., et al. Comprehensive omics studies of p53 mutants in human cancer. Brief Funct Genomics. 2022:elac015. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elac015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi L., Cao J., Lei X., et al. Multi-omics data identified TP53 and LRP1B as key regulatory gene related to immune phenotypes via EPCAM in HCC. Cancer Med. 2022;11(10):2145–2158. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang D.-T., Ma Z.-L., Li Y.-L., et al. miR-150, p53 protein and relevant miRNAs consist of a regulatory network in NSCLC tumorigenesis. Oncol. Rep. 2013;30(1):492–498. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L., Yu Z.-Y., Yu T.-T., et al. A Slug-dependent mechanism is responsible for tumor suppression of p53-stabilizing compound CP-31398 in p53-mutated endometrial carcinoma. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020;235(11):8768–8778. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malarz K., Mularski J., Kuczak M., et al. Novel benzenesulfonate scaffolds with a high anticancer activity and G2/M cell cycle arrest. Cancers. 2021;13(8) doi: 10.3390/cancers13081790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei X.-W., Yuan J.-M., Huang W.-Y., et al. 2-Styryl-4-aminoquinazoline derivatives as potent DNA-cleavage, p53-activation and in vivo effective anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;186 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aggarwal M., Saxena R., Asif N., et al. p53 mutant-type in human prostate cancer cells determines the sensitivity to phenethyl isothiocyanate induced growth inhibition. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):307. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1267-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam-Ubol A., Fitzgerald A.L., Ritdej A., et al. Sensory acceptable equivalent doses of β-phenylethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC) induce cell cycle arrest and retard the growth of p53 mutated oral cancer in vitro and in vivo. Food Funct. 2018;9(7):3640–3656. doi: 10.1039/c8fo00865e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aggarwal M., Saxena R., Sinclair E., et al. Reactivation of mutant p53 by a dietary-related compound phenethyl isothiocyanate inhibits tumor growth. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(10):1615–1627. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y., Vocke C.D., Ricketts C.J., et al. Genomic and metabolic characterization of a chromophobe renal cell carcinoma cell line model (UOK276) Genes, Chromosomes Cancer. 2017;56(10):719–729. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Synnott N.C., O'Connell D., Crown J., et al. COTI-2 reactivates mutant p53 and inhibits growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020;179(1):47–56. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindemann A., Patel A.A., Silver N.L., et al. COTI-2, A novel thiosemicarbazone derivative, exhibits antitumor activity in HNSCC through p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25(18):5650–5662. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amirtharaj F., Venkatesh G.H., Wojtas B., et al. p53 reactivating small molecule PRIMA-1/APR-246 regulates genomic instability in MDA-MB-231 cells. Oncol. Rep. 2022;47(4) doi: 10.3892/or.2022.8296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neal A., Lai T., Singh T., et al. Combining ReACp53 with carboplatin to target high-grade serous ovarian cancers. Cancers. 2021;13(23) doi: 10.3390/cancers13235908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ray-Coquard I., Braicu I., Berger R., et al. Part I of GANNET53: a European multicenter phase I/II trial of the Hsp90 inhibitor ganetespib combined with weekly paclitaxel in women with high-grade, platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer-A study of the GANNET53 consortium. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:832. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jansson K.H., Tucker J.B., Stahl L.E., et al. High-throughput screens identify HSP90 inhibitors as potent therapeutics that target inter-related growth and survival pathways in advanced prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35417-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Müller M., Rösch L., Najafi S., et al. Combining APR-246 and HDAC-inhibitors: a novel targeted treatment option for neuroblastoma. Cancers. 2021;13(17) doi: 10.3390/cancers13174476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bazrgar M., Khodabakhsh P., Prudencio M., et al. The role of microRNA-34 family in Alzheimer's disease: a potential molecular link between neurodegeneration and metabolic disorders. Pharmacol. Res. 2021;172 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C., Jia Q., Guo X., et al. microRNA-34 family: from mechanism to potential applications. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2022;144 doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2022.106168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L., Liao Y., Tang L. MicroRNA-34 family: a potential tumor suppressor and therapeutic candidate in cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1059-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S., Wei X., He J., et al. The comprehensive landscape of miR-34a in cancer research. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021;40(3):925–948. doi: 10.1007/s10555-021-09973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakami Y., Kimura-Masuda K., Oda T., et al. MYC causes multiple myeloma progression via attenuating TP53-induced MicroRNA-34 expression. Genes. 2022;14(1) doi: 10.3390/genes14010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alshehri A.S., El-Kott A.F., El-Kenawy A.E., et al. Cadmium chloride induces non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats by stimulating miR-34a/SIRT1/FXR/p53 axis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;784 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin F., Wen D., Wang X., et al. Dual responsive micelles capable of modulating miRNA-34a to combat taxane resistance in prostate cancer. Biomaterials. 2019:192. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Z.-L., Hou P.-P., Li Y.-L., et al. MicroRNA-34a inhibits the proliferation and promotes the apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer H1299 cell line by targeting TGFβR2. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(4):2481–2490. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y.L., Liu X.M., Zhang C.Y., et al. MicroRNA-34a/EGFR axis plays pivotal roles in lung tumorigenesis. Oncogenesis. 2017;6(8):e372. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2017.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gatsiou A., Georgiopoulos G., Vlachogiannis N.I., et al. Additive contribution of microRNA-34a/b/c to human arterial ageing and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2021;327:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu X., Cheng Y.-S.L., Matthen M., et al. Down-regulation of the tumor suppressor miR-34a contributes to head and neck cancer by up-regulating the MET oncogene and modulating tumor immune evasion. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-01865-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X., Zhao S., Fu Y., et al. miR-34a-5p functions as a tumor suppressor in head and neck squamous cell cancer progression by targeting Flotillin-2. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021;17(15):4327–4339. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.64851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grad M., Nir A., Levy G., et al. Altered white matter and microRNA expression in a murine model related to williams syndrome suggests that miR-34b/c affects brain development via ptpru and dcx modulation. Cells. 2022;11(1) doi: 10.3390/cells11010158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan H., Li Y., Yuan F., et al. Up-regulation of microRNA-34a mediates ethanol-induced impairment of neural crest cell migration in vitro and in zebrafish embryos through modulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting Snail1. Toxicol. Lett. 2022;358:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2022.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi X., Kaller M., Rokavec M., et al. Characterization of a p53/miR-34a/CSF1R/STAT3 feedback loop in colorectal cancer. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;10(2):391–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chi D.H., Kahyo T., Islam A., et al. NAD(+) levels are augmented in aortic tissue of ApoE(-/-) mice by dietary omega-3 fatty acids. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022;42(4):395–406. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.317166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hao R., Song X., Sun-Waterhouse D., et al. MiR-34a/Sirt1/p53 signaling pathway contributes to cadmium-induced nephrotoxicity: a preclinical study in mice. Environ. Pollut. 2021;282 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ong A.L.C., Ramasamy T.S. Role of Sirtuin1-p53 regulatory axis in aging, cancer and cellular reprogramming. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018;43:64–80. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steele T.M., Talbott G.C., Sam A., et al. Obatoclax, a BH3 mimetic, enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis and decreases the clonogenicity of muscle invasive bladder cancer cells via mechanisms that involve the inhibition of pro-survival molecules as well as cell cycle regulators. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(6) doi: 10.3390/ijms20061285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu D., Song Q., Liu Y., et al. LINC00665 promotes Ovarian Cancer progression through regulating the miRNA-34a-5p/E2F3 axis. J. Cancer. 2021;12(6):1755–1763. doi: 10.7150/jca.51457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y., Chen J., Chen X., et al. MiR-34a suppresses HNSCC growth through modulating cell cycle arrest and senescence. Neoplasma. 2017;64(4):543–553. doi: 10.4149/neo_2017_408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pi C., Ma C., Wang H., et al. MiR-34a suppression targets Nampt to ameliorate bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell senescence by regulating NAD(+)-Sirt1 pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021;12(1):271. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02339-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan W., Tang S., Fan X., et al. SIRT1 regulates sphingolipid metabolism and neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells through c-Myc-SMPDL3B. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.67452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao J., Lin H., Huang K. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles transmitting MicroRNA-34a-5p suppress tumorigenesis of colorectal cancer through c-MYC/DNMT3a/PTEN Axis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021;59(1):47–60. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02431-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li S., Wei X., He J., et al. The comprehensive landscape of miR-34a in cancer research. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021;40(3):925–948. doi: 10.1007/s10555-021-09973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhai L., Zhao Y., Liu Z., et al. mRNA expression profile analysis reveals a C-MYC/miR-34a pathway involved in the apoptosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells induced by Yiqichutan treatment. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020;20(3):2157–2165. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kapadia C.H., Ioele S.A., Day E.S. Layer-by-layer assembled PLGA nanoparticles carrying miR-34a cargo inhibit the proliferation and cell cycle progression of triple-negative breast cancer cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2020;108(3):601–613. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruiz-Camp J., Quantius J., Lignelli E., et al. Targeting miR-34a/Pdgfra interactions partially corrects alveologenesis in experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019;11(3) doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Casanova J.M., Almeida J.S., Reith J.D., et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and cancer markers in osteosarcoma: influence on patient survival. Cancers. 2021;13(23) doi: 10.3390/cancers13236075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brabletz T., Kalluri R., Nieto M.A., et al. EMT in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018;18(2):128–134. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aida R., Hagiwara K., Okano K., et al. miR-34a-5p might have an important role for inducing apoptosis by down-regulation of SNAI1 in apigenin-treated lung cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021;48(3):2291–2297. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y., Wu Z., Hu L. The regulatory effects of metformin on the [SNAIL/miR-34]:[ZEB/miR-200] system in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition(EMT) for colorectal cancer(CRC) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018;834:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hahn S., Jackstadt R., Siemens H., et al. SNAIL and miR-34a feed-forward regulation of ZNF281/ZBP99 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition. EMBO J. 2013;32(23):3079–3095. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim J.S., Kim E.J., Lee S., et al. MiR-34a and miR-34b/c have distinct effects on the suppression of lung adenocarcinomas. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019;51(1) doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0203-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Córdova-Rivas S., Fraire-Soto I., Mercado-Casas Torres A., et al. 5p and 3p strands of miR-34 family members have differential effects in cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in cervical cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(3) doi: 10.3390/ijms20030545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rokavec M., Öner M.G., Li H., et al. Corrigendum. IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a feedback loop promotes EMT-mediated colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125(3):1362. doi: 10.1172/JCI81340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang X., Xie X., Wang H., et al. PDL1 and LDHA act as ceRNAs in triple negative breast cancer by regulating miR-34a. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0593-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun D., Wu Y., Zhang S., et al. Distinct roles of miR-34 family members on suppression of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen Y., Li Z., Zhang M., et al. Correction to: circ-ASH2L promotes tumor progression by sponging miR-34a to regulate Notch1 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-01902-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chu J., Jia J., Yang L., et al. LncRNA MIR31HG functions as a ceRNA to regulate c-Met function by sponging miR-34a in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;128 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen Y.-L., Liu X.-L., Li L. Prognostic value of low microRNA-34a expression in human gastrointestinal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07751-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Son J., Jang J., Beyett T.S., et al. A novel HER2-selective kinase inhibitor is effective in HER2 mutant and amplified non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2022;82(8):1633–1645. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun D., Wu Y., Zhang S., et al. Distinct roles of miR-34 family members on suppression of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garinet S., Didelot A., Denize T., et al. Clinical assessment of the miR-34, miR-200, ZEB1 and SNAIL EMT regulation hub underlines the differential prognostic value of EMT miRs to drive mesenchymal transition and prognosis in resected NSCLC. Br. J. Cancer. 2021;125(11):1544–1551. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01568-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feng H., Ge F., Du L., et al. MiR-34b-3p represses cell proliferation, cell cycle progression and cell apoptosis in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by targeting CDK4. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019;23(8):5282–5291. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin Q.Y., Yin H.L. RBM38 induces SIRT1 expression during hypoxia in non-small cell lung cancer cells by suppressing MIR34A expression. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020;42(1):35–44. doi: 10.1007/s10529-019-02766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang J., Zhao X., Wang Y., et al. circRNA-002178 act as a ceRNA to promote PDL1/PD1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(1):32. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2230-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.An Y., Yang Q. Tumor-associated macrophage-targeted therapeutics in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2021;149(1):21–30. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eisenhauer E.A. Real-world evidence in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_8):viii61–viii65. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Welponer H., Tsibulak I., Wieser V., et al. The miR-34 family and its clinical significance in ovarian cancer. J. Cancer. 2020;11(6):1446–1456. doi: 10.7150/jca.33831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jia Y., Lin R., Jin H., et al. MicroRNA-34 suppresses proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells by triggering autophagy and apoptosis and inhibits cell invasion by targeting Notch 1. Biochimie. 2019;160:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021;7(1):7. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hartke J., Johnson M., Ghabril M. The diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2017;34(2):153–159. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Feili X., Wu S., Ye W., et al. MicroRNA-34a-5p inhibits liver fibrosis by regulating TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway in hepatic stellate cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2018;42(10):1370–1376. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Qi Y., Zhang C., Wu D., et al. Indole-3-Carbinol stabilizes p53 to induce miR-34a, which targets LDHA to block aerobic glycolysis in liver cancer cells. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(10) doi: 10.3390/ph15101257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhao X., Zhuang Y., Wang B., et al. The miR-34a-5p-c-MYC-CHK1/CHK2 Axis counteracts cancer stem cell-like properties and enhances radiosensitivity in hepatocellular cancer through repression of the DNA damage response. Radiat. Res. 2023;199(1):48–60. doi: 10.1667/RADE-22-00098.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Makino Y., Hikita H., Fukumoto K., et al. Constitutive activation of the tumor suppressor p53 in hepatocytes paradoxically promotes non-cell autonomous liver carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2022;82(16):2860–2873. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li F.-Y., Fan T.-Y., Zhang H., et al. Demethylation of miR-34a upregulates expression of membrane palmitoylated proteins and promotes the apoptosis of liver cancer cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021;27(6):470–486. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i6.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang Y., Yuan H., Zhao L., et al. Targeting the miR-34a/LRPPRC/MDR1 axis collapse the chemoresistance in P53 inactive colorectal cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29(11):2177–2189. doi: 10.1038/s41418-022-01007-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Feng Q., Wang D., Guo P., et al. Apatinib functioned as tumor suppressor of synovial sarcoma through regulating miR-34a-5p/HOXA13 Axis. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/7214904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 90.Guo X., Zhou Q., Su D., et al. Circular RNA circBFAR promotes the progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via the miR-34b-5p/MET/Akt axis. Mol. Cancer. 2020;19(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang L., Wang L., Dong D., et al. MiR-34b/c-5p and the neurokinin-1 receptor regulate breast cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis. Cell Prolif. 2019;52(1) doi: 10.1111/cpr.12527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Srinivasan A.R., Tran T.T., Bonini N.M. Loss of miR-34 in Drosophila dysregulates protein translation and protein turnover in the aging brain. Aging Cell. 2022;21(3) doi: 10.1111/acel.13559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tian F., Wang J., Zhang Z., et al. LncRNA SNHG7/miR-34a-5p/SYVN1 axis plays a vital role in proliferation, apoptosis and autophagy in osteoarthritis. Biol. Res. 2020;53(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s40659-020-00275-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wu J., Li X., Li D., et al. MicroRNA-34 family enhances wound inflammation by targeting LGR4. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2020;140(2) doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.07.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang L.-Z., Yang J.-E., Luo Y.-W., et al. A p53/lnc-Ip53 negative feedback loop regulates tumor growth and chemoresistance. Adv. Sci. 2020;7(21) doi: 10.1002/advs.202001364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Luo Y., Chen J.-J., Lv Q., et al. Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 promotes colorectal cancer progression by competitively binding miR-34a with SIRT1 and enhancing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2019;440–441:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li F., Li X., Qiao L., et al. MALAT1 regulates miR-34a expression in melanoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(6):389. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1620-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shree B., Sengar S., Tripathi S., et al. LINC01711 promotes transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) induced invasion in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) by acting as a competing endogenous RNA for miR-34a and promoting ZEB1 expression. Neurosci. Lett. 2023;792 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hong D.S., Kang Y.-K., Borad M., et al. Phase 1 study of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br. J. Cancer. 2020;122(11):1630–1637. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0802-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cluzeau T., Sebert M., Rahmé R., et al. Eprenetapopt Plus Azacitidine in -Mutated Myelodysplastic Syndromes and Acute Myeloid Leukemia: a Phase II Study by the Groupe Francophone des Myélodysplasies (GFM) J. Clin. Oncol. 2021;39(14):1575–1583. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Faruq O., Zhao D., Shrestha M., et al. Targeting an MDM2/MYC Axis to overcome drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Cancers. 2022;14(6) doi: 10.3390/cancers14061592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Taylor A., Lee D., Allard M., et al. Phase 1 concentration-QTc and cardiac safety analysis of the MDM2 antagonist KRT-232 in patients with advanced solid tumors, multiple myeloma, or acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2021;10(8):918–926. doi: 10.1002/cpdd.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang Z., Oh M., Sasaki J.-I., et al. Inverse and reciprocal regulation of p53/p21 and Bmi-1 modulates vasculogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(7):644. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03925-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang X., Ren Z., Xu Y., et al. KCNQ1OT1 sponges miR-34a to promote malignant progression of malignant melanoma via upregulation of the STAT3/PD-L1 axis. Environ. Toxicol. 2023;38(2):368–380. doi: 10.1002/tox.23687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Deng S., Wang M., Wang C., et al. p53 downregulates PD-L1 expression via miR-34a to inhibit the growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells: a potential clinical immunotherapeutic target. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023;50(1):577–587. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-08047-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tsai T.-F., Chang A.-C., Chen P.-C., et al. Autophagy blockade potentiates cancer-associated immunosuppression through programmed death ligand-1 upregulation in bladder cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2022;237(9):3587–3597. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Low L., Goh A., Koh J., et al. Targeting mutant p53-expressing tumours with a T cell receptor-like antibody specific for a wild-type antigen. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):5382. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13305-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hsiue E.H.-C., Wright K.M., Douglass J., et al. Targeting a neoantigen derived from a common TP53 mutation. Science. 2021;(6533):371. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jiang L., Kon N., Li T., et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520(7545):57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature14344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chu B., Kon N., Chen D., et al. ALOX12 is required for p53-mediated tumour suppression through a distinct ferroptosis pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019;21(5):579–591. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0305-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chen D., Chu B., Yang X., et al. iPLA2β-mediated lipid detoxification controls p53-driven ferroptosis independent of GPX4. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):3644. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23902-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ou Y., Wang S.J., Li D., et al. Activation of SAT1 engages polyamine metabolism with p53-mediated ferroptotic responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113(44):E6806–e6812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607152113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tarangelo A., Magtanong L., Bieging-Rolett K.T., et al. p53 suppresses metabolic stress-induced ferroptosis in cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2018;22(3):569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.