Abstract

Objectives

2-deoxy-2[18F]Fluoro-d-glucose (FDG) PET-CT has an emerging role in assessing response to neoadjuvant therapy in oesophageal cancer. This study evaluated FDG PET-CT in predicting pathological tumour response (pTR), pathological nodal response (pNR) and survival.

Methods

Cohort study of 75 patients with oesophageal or oesophago-gastric junction (GOJ) adenocarcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy then surgery at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London (2017–2020). Standardised uptake value (SUV) metrics on pre- and post-treatment FDG PET-CT in the primary tumour (mTR) and loco-regional lymph nodes (mNR) were derived. Optimum SUVmax thresholds for predicting pathological response were identified using receiver operating characteristic analysis. Predictive accuracy was compared to PERCIST (30% SUVmax reduction) and MUNICON (35%) criteria. Survival was assessed using Cox regression.

Results

Optimum tumour SUVmax decrease for predicting pTR was 51.2%. A 50% cut-off predicted pTR with 73.5% sensitivity, 69.2% specificity and greater accuracy than PERCIST or MUNICON (area under the curve [AUC] 0.714, PERCIST 0.631, MUNICON 0.659). Using a 30% SUVmax threshold, mNR predicted pNR with high sensitivity but low specificity (AUC 0.749, sensitivity 92.6%, specificity 57.1%, p = 0.010). pTR, mTR, pNR and mNR were independent predictive factors for survival (pTR hazard ratio [HR] 0.10 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.03–0.34; mTR HR 0.17 95% CI 0.06–0.48; pNR HR 0.17 95% CI 0.06–0.54; mNR HR 0.13 95% CI 0.02–0.66).

Conclusions

Metabolic tumour and nodal response predicted pTR and pNR, respectively, in patients with oesophageal or GOJ adenocarcinoma. However, currently utilised response criteria may not be optimal. pTR, mTR, pNR and mNR were independent predictors of survival.

Key Points

• FDG PET-CT has an emerging role in evaluating response to neoadjuvant therapy in patients with oesophageal cancer.

• Prospective cohort study demonstrated that metabolic response in the primary tumour and lymph nodes was predictive of pathological response in a cohort of patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection.

• Patients who demonstrated a response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the primary tumour or lymph nodes on FDG PET-CT demonstrated better survival and reduced rates of tumour recurrence.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00330-023-09482-7.

Keywords: Oesophageal neoplasms; Positron emission tomography-computed tomography; Neoadjuvant therapy; Pathology, Surgical; Surgical oncology

Introduction

2-Deoxy-2[18F]fluoro-d-glucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG PET-CT) is routinely used for staging of oesophageal cancer and has an emerging role in evaluating response to neoadjuvant therapy [1, 2]. A reduction in FDG avidity of the primary tumour and loco-regional lymph nodes (LN) following neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to predict pathological response and survival [1–4]. However, no studies have evaluated the prognostic significance of metabolic parameters derived on FDG PET-CT with respect to pathological response in LNs, but have instead used primary tumour response or pathological nodal stage as a surrogate [5]. This is despite emerging evidence of a discrepancy, in up to 25% of patients, between the response in the primary tumour compared with that in LNs [1, 6, 7]. One hypothesis is that this discrepancy may be due to variations in chemo-sensitivity of different clonal populations of tumour cells [6, 8].

Change in primary tumour maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) is the most widely used FDG PET-CT parameter to define metabolic response to treatment with various thresholds described. The most commonly utilised are a 35% reduction in SUVmax as adopted by the MUNICON trial [9] and PET Response Criteria in Solid Tumours (PERCIST) which recommends a 30% reduction to define response [10]. However, there is no consensus regarding the optimal classification; the MUNICON threshold was derived from only 40 patients [11] and PERCIST is not tumour specific.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of FDG PET-CT to predict pathological response in the primary tumour and LNs for patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to surgical resection. Secondary aims were to assess the prognostic effect of metabolic and pathological response on survival and to evaluate the predictive ability of currently utilised response classifications.

Methods

Design

This was a cohort study based on an ethically approved, prospectively maintained database of consecutive oesophago-gastric resections performed at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. The present study included patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy who underwent oesophago-gastrectomy with curative intent for histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction between January 2017 and December 2020. All patients had locally advanced tumours, i.e. cT2 or higher, positive LNs or both. Tumours were staged using the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM version 8 [12]. Tumours of the oesophago-gastric junction were categorised using the Siewert classification [13]. The primary outcome measure was tumour regression grade in the primary tumour and LNs. Secondary outcomes were overall and disease-free survival.

FDG PET-CT protocol

Patients were assessed with FDG PET-CT before and after completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, prior to surgery. The majority of patients had FDG PET-CT performed on one of two GE Discovery 710 PET-CT systems (GE Healthcare) at the host institution. Patients were fasted for a minimum of 6 h. A standard PET acquisition minimum coverage from skull base to upper thighs was acquired post-injection of a 350-MBq + / − 10% and an uptake time of 60 min at 3 min per bed position. The standard clinical attenuation–corrected PET reconstruction was a time-of-flight ordered subset expected maximisation reconstruction using 2 iterations, 24 subsets and a 6.4-mm Gaussian filter (VPFX, GE Healthcare) and thickness of 3.27 mm. The low-dose unenhanced CT scan was performed in shallow respiration, using a standardised protocol: 140 kV, pitch 1.375, 40 mm beam collimation (64 × 0.625 mm), 0.5-s rotation time and auto mA (15–100 mA, noise index 40). CT images were reconstructed with a thickness of 2.5 mm. A minority of patients had a combination of FDG PET-CT examinations performed on different scanners at the same institution, or different scanners at different institutions. Image analysis was undertaken using Hybrid Viewer (Hermes Medical Solutions) by a board-certified radiologist (M.S.) with 10 years of PET-CT reporting and who provides specialist input to the upper gastro-intestinal multi-disciplinary team meeting.

Tumour measurements

A freehand region of interest (ROI) was used to calculate the SUVmax in the primary tumour. For oesophageal tumours, metabolic tumour length was calculated by multiplying the number of axial images the primary tumour was visible by the section thickness of the PET images. For junctional tumours with a non-vertical orientation, a freehand measurement was made in the most appropriate orthogonal imaging plane. Axial fused PET-CT imaging, with its ability to demonstrate residual mural thickening, was used to assist measurement of SUVmax in the primary tumour on post-treatment imaging when tumoural uptake was visually indistinguishable from background physiological oesophago-gastric uptake.

Metabolic tumour response (mTR)

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to determine optimum SUVmax and metabolic tumour length thresholds for predicting pTR in the study cohort. Metabolic tumour response (mTR) was defined using PERCIST (ΔSUVmax 30%) and MUNICON (ΔSUVmax 35%) and based on results of ROC curve analysis. Patients with a complete metabolic response (CMR), i.e. tumour indistinguishable from background physiological oesophago-gastric uptake, or partial metabolic response (PMR), i.e. reduction in tumour SUVmax ≥ pre-defined thresholds detailed above, were classified as responders. Patients with stable metabolic disease (SMD), i.e. reduction or increase in tumour SUVmax < predefined thresholds, or progressive metabolic disease (PMD), i.e. increase in tumour SUVmax ≥ predefined thresholds, were classified as non-responders.

Nodal measurements

Metabolic nodal (mN) stage was defined as nodes discrete from the primary tumour within a standard lymphadenectomy territory visible above background soft tissue uptake and categorised as mN0 (0 avid nodes), mN1 (1–2 avid nodes), mN2 (3–6 avid nodes) or mN3 (> 6 avid nodes). A freehand ROI was drawn around the most avid node to determine nodal SUVmax. Post-treatment nodal SUVmax measurement was not possible if nodal uptake was visually indiscernible from background soft tissue uptake and the size of the nodal residuum on axial fused PET-CT imaging was small thereby precluding reliable assessment.

Metabolic nodal response

Metabolic nodal response (mNR) was defined as CMR (no discernible uptake above background soft tissue uptake), PMR (reduction in mN category or SUVmax ≥ 30%), SMD (stable mN category or reduction/progression in SUVmax < 30%) or PMD (progression of mN category or SUVmax ≥ 30%). ROC curve analysis was used to identify optimum SUVmax nodal threshold for predicting pNR in the study cohort.

Pathological tumour and nodal response (pTR and pNR)

Pathological response was evaluated using the Mandard classification, a 5-point categorical scoring system based on the proportion of fibrosis and viable tumour cells in the surgical resection specimen [14]. Mandard scores were calculated for response in the primary tumour (pTR) and resected LN (pNR) as described previously [6]. Patients with Mandard scores of 1–3 were classified as responders and those with scores of 4–5 as non-responders.

Treatment

All patients were on a curative-intent treatment pathway and received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection. Patients who received extended neoadjuvant therapy as part of an advanced disease protocol were excluded. Transthoracic or transhiatal oesophagectomy or extended total gastrectomy was performed by either open or minimally invasive approach.

Statistical analysis

Clinicopathological characteristics were compared using the chi-squared test. Overall survival was defined as time from surgery to death or date of last outpatient department visit. Disease-free survival was defined as time from surgery to cancer recurrence, death or date of last outpatient department visit. Continuous variables (SUVmax and metabolic tumour length) were evaluated using ROC analysis to identify the threshold which provided the greatest area under the curve (AUC) for predicting pathological response in the study cohort. An AUC of 1.0 indicated perfect predictive ability and an AUC of 0.5, no ability. Crude and adjusted logistic regression analyses were performed adjusting for age (continuous), sex (male or female), chemotherapy regimen (epirubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine (ECX) or fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin and docetaxel (FLOT)) and presence of signet ring cells (yes or no). Survival curves were created using the Kaplan–Meier method, with subgroups compared using the log-rank test. Crude and adjusted survival analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazards regression adjusted for age (continuous), sex (male or female), chemotherapy regimen (ECX or FLOT), cT stage (cT1–2 or cT3–4), cN stage (cN0 or cN +), tumour grade (well/moderately differentiated or poorly differentiated) and presence of signet ring cells (yes or no). Confounders for logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards analyses were defined based on directed acyclic graphs [15]. Harrell’s C-index was calculated to compare the accuracy of different metabolic response parameters to predict survival. p values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics (IBM Corp, IBM SPSS statistics Version 27.0.) and GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Results

Patient and treatment characteristics

There were 76 eligible patients identified from the institutional database. One patient had a non-avid tumour on baseline FDG PET-CT and was excluded, leaving 75 patients for final analysis. Mean age was 63 years (range 26–79) with the majority male (65/75, 86.7%) (Table 1). Almost two thirds received FLOT (48/75, 64.0%) with the remainder receiving ECX chemotherapy. Most patients (71/75, 94.7%) completed all prescribed cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a minority completing 2 cycles of ECX (n = 2) or 2 cycles of FLOT (n = 2). There was discordance between pathological response in the primary tumour and LN in several patients, including a significant proportion (6/26, 23.1%) who demonstrated a LN response in the absence of a response in the primary tumour. Median SUVmax pre- and post-chemotherapy, respectively, was 11.5 (range 3.8–47.6) and 4.4 (2.7–30.3) in the primary tumour and 4.4 (1.5–19.3) and 2.2 (1.0–8.2) in LNs. The majority of patients had baseline and post-treatment FDG PET-CT performed on the same scanner at the host institution (61/75, 81.3%). The PET scanners used for the remaining 14 patients are shown in Supplementary table 1. Stratified analysis excluding patients with FDG PET-CT performed on different scanners (Supplementary table 2, Supplementary table 3) did not demonstrate any major differences to clinicopathological, response or survival results, so this cohort was included in the final analysis.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological and treatment characteristics of 75 patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection

| Variable | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at operation (mean) | 63 years | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 65 (86.7%) | |

| Female | 10 (13.3%) | |

| Tumour location | ||

| Oesophagus | 11 (14.7%) | |

| Oesophago-gastric junction | Siewert type 1 | 11 (14.7%) |

| Siewert type 2 | 45 (60.0%) | |

| Siewert type 3 | 8 (10.7%) | |

| Operation | ||

| Transthoracic oesophagectomy | 50 (66.7%) | |

| Transhiatal oesophagectomy | 12 (16.0%) | |

| Extended total gastrectomy | 13 (17.3%) | |

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||

| ECX | 27 (36.0%) | |

| FLOT | 48 (64.0%) | |

| cT stage | ||

| cT0–2 | 4 (5.3%) | |

| cT3–4 | 71 (94.7%) | |

| cN stage | ||

| cN0 | 9 (12.0%) | |

| cN1–3 | 66 (88.0%) | |

| ypT stage | ||

| ypT0–2 | 37 (49.3%) | |

| ypT3–4 | 38 (50.7%) | |

| ypN stage | ||

| ypN0 | 39 (52.0%) | |

| ypN1–3 | 36 (48.0%) | |

| Tumour grade | ||

| Well/moderate differentiation | 39 (52.0%) | |

| Poor differentiation | 36 (48.0%) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||

| No | 43 (57.3%) | |

| Yes | 32 (42.7%) | |

| Signet ring cell | ||

| No | 66 (88.0%) | |

| Yes | 9 (12.0%) | |

| Resection margin | ||

| R0 | 54 (72.0%) | |

| R1 | 21 (28.0%) | |

| Baseline and restaging FDG PET-CT performed on same scanner | ||

| Yes | 61 (81.3%) | |

| No | 14 (18.7%) | |

| Pathological primary tumour regression (pTR) | ||

| Responder (Mandard 1–3) | 49 (65.3%) | |

| Non-responder (Mandard 4–5) | 26 (34.7%) | |

| Pathological nodal regression (pNR) | ||

| Responder (Mandard 1–3) | 27 (36.0%) | |

| Non-responder (Mandard 4–5) | 21 (28.0%) | |

| Negative nodes | 24 (32.0%) | |

| Not recorded | 3 (4.0%) | |

| Discordance between pTR and pNR | ||

| pT responder and pN non-responder | 5 (6.9%) | |

| pN responder and pT non-responder | 6 (8.3%) | |

| mT responder and mN non-responder | 3 (4.0%) | |

| mN responder and mT non-responder | 3 (4.0%) | |

| Recurrence | ||

| No recurrence | 51 (68.0%) | |

| Any recurrence | 24 (32.0%) | |

| Death | ||

| Alive at end of follow-up | 54 (72.0%) | |

| Not alive at end of follow-up | 21 (28.0%) | |

| Median SUVmax (range) | ||

| Tumour pre-chemotherapy | 11.5 (3.8–47.6) | |

| Tumour post-chemotherapy | 4.4 (2.7–30.3) | |

| Lymph node pre-chemotherapy | 4.4 (1.5–19.3) | |

| Lymph node post-chemotherapy | 2.2 (1.0–8.2) | |

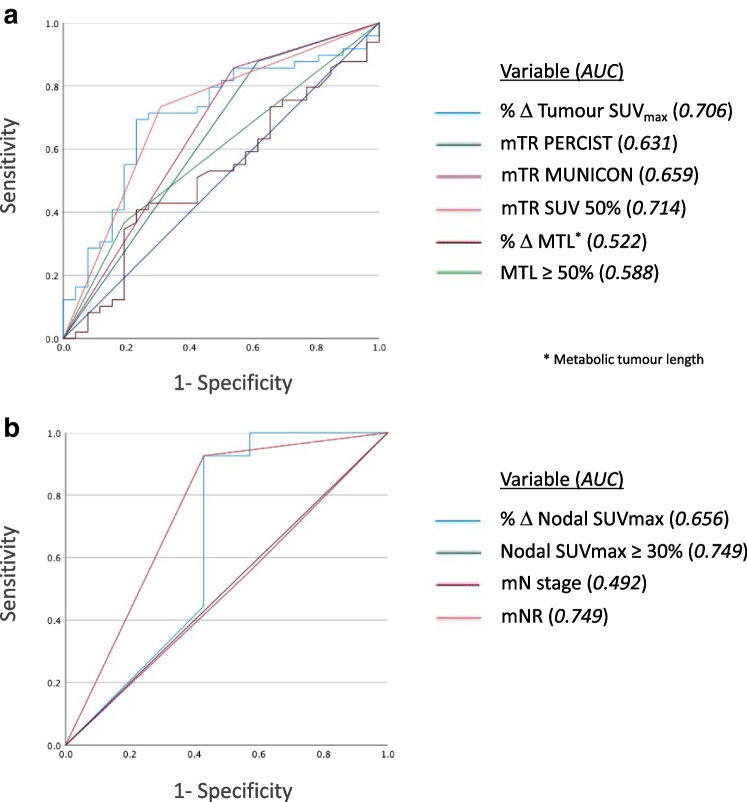

Prognostic ability of metabolic tumour response to predict pathological tumour response

ROC analysis (Fig. 1) demonstrated an optimum tumour SUVmax decrease of 51.2% for predicting pTR. Using a pragmatic cut-off of 50% (SUV 50%), this provided the best predictor of pTR (Table 2) (AUC 0.714, sensitivity 73.5%, specificity 69.2%, positive predictive value (PPV) 81.3%, negative predictive value (NPV) 58.1%, p < 0.001). This was more accurate than PERCIST (AUC 0.631, sensitivity 87.8%, specificity 38.5%, PPV 72.9%, NPV 62.5%, p = 0.008) and MUNICON (AUC 0.659, sensitivity 85.7%, specificity 46.2%, PPV 75.0%, NPV 63.2%, p = 0.003) which demonstrated higher sensitivity but significantly lower specificity. ROC analysis demonstrated an optimum reduction of metabolic tumour length of 46.9% for predicting pTR. Using a similarly pragmatic cut-off of 50%, this was less accurate than SUVmax (AUC 0.588, sensitivity 36.7%, specificity 80.8%, PPV 78.3%, NPV 40.4%, p = 0.118). mTR using SUV 50% and MUNICON provided the best concordance with pTR (n = 54, 72.0%), better than for PERCIST (n = 53, 70.7%) and reduction in metabolic tumour length (n = 39, 52.0%).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis evaluating the ability of metabolic tumour response (mTR) parameters to predict pathological tumour response (a) and the ability of metabolic nodal parameters (mNR) to predict pathological nodal response or pathological node negativity in patients with metabolic positive nodes on baseline FDG PET-CT (b) in 75 patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection

Table 2.

Prognostic ability of metabolic response parameters to predict pathological response in 75 patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection

| Pathologic response | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondera | Non-responderb | AUCc | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPVd | NPVe | p value | ||

|

mTRf PERCIST |

Responderg | 43 (72.9%) | 16 (27.1%) | 0.631 | 87.8% | 38.5% | 72.9% | 62.5% | p = 0.008 |

| Non-responderh | 6 (37.5%) | 10 (62.5%) | |||||||

|

mTR MUNICON |

Responderg | 42 (75.0%) | 14 (25.0%) | 0.659 | 85.7% | 46.2% | 75.0% | 63.2% | p = 0.003 |

| Non-respondere | 7 (36.8%) | 12 (63.2%) | |||||||

|

mTR SUV 50% |

Responderg | 36 (81.3%) | 8 (18.2%) | 0.714 | 73.5% | 69.2% | 81.3% | 58.1% | p < 0.001 |

| Non-responderh | 13 (41.9%) | 18 (58.1%) | |||||||

| MTLi | Responderj | 18 (78.3%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.588 | 36.7% | 80.8% | 78.3% | 40.4% | p = 0.12 |

| Non-responderk | 31 (59.6%) | 21 (40.4%) | |||||||

| mNRl | mN responderm | 25 (86.2%) | 4 (13.8%) | 0.749 | 92.6% | 57.1% | 86.2% | 66.7% | p = 0.010 |

| mN non-respondern | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | |||||||

Italics denote a statistically significant p-value

aMandard 1–3 (includes pN-negative nodes for nodal response)

bMandard 4–5

cArea under the curve

dPositive predictive value

eNegative predictive value

fMetabolic tumour response

gComplete/partial metabolic response

hStable/progressive metabolic disease

iMetabolic tumour length

j ≥ 50% decrease

k < 50% decrease or increase

lMetabolic nodal response, excluding metabolic negative nodes on baseline and restaging FDG PET-CT

mComplete/partial metabolic response or decrease in mN stage

nStable/progressive metabolic disease or stable/increase in mN stage

Logistic regression analysis (Table 3) demonstrated that all metabolic response criteria predicted pathological response except change in metabolic tumour length. However, SUV 50% was the most prognostic (SUV 50% odds ratio [OR] 7.41, 95% CI 2.23–24.61; MUNICON OR 4.87, 95% CI 1.37–17.30; PERCIST OR 4.05, 95% CI 1.09–15.04; change in tumour length OR 2.48, 95% CI 0.73–8.36). No other confounders in the adjusted model were predictive for pathological response. A further iteration of the model adjusting additionally for FDG PET-CT performed on separate scanners yielded similar results (SUV 50%, OR 7.33, 95% CI 2.20–24.47). Evaluation of metabolic response stratified by Mandard score in the primary tumour (Supplementary table 4) demonstrated that patients with a lower Mandard score (1–3) were more likely to be metabolic responders and also demonstrated improved survival.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models evaluating the ability of metabolic tumour response (mTR) parameters and metabolic nodal response (mNR) to predict pathological response in 75 patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection, providing odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI)

| Crude | Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| MTLb,c | Non-respondere | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Responderf | 2.44 (0.78–7.59) | 2.48 (0.73–8.36) | |

| mTR PERCISTc | Non-responderg | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Responderh | 4.48 (1.40–14.34) | 4.05 (1.09–15.04) | |

| mTR MUNICONc | Non-responderg | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Responderh | 5.14 (1.69–15.62) | 4.87 (1.37–17.30) | |

| mTR SUV 50%c | Non-responderg | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Responderh | 6.23 (2.19–17.75) | 7.41 (2.23–24.61) | |

| mNRd | Non-responderi | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Responderj | 16.67 (2.09–133.05) | 17.19 (1.92–154.16) | |

| mN negative | 3.43 (0.56–21.18) | 3.31(0.50–21.84) | |

Bold entries indicate statistically significant results

aAdjusted for: age, sex, chemotherapy regimen (FLOT/ECX), signet ring cell (yes, no)

bMetabolic tumour length

cModel evaluating pathological tumour response (Mandard 1–3)

dModel evaluating pathologic nodal response (Mandard 1–3) or node negativity

e ≥ 50% decrease

f < 50% decrease or increase

gComplete/partial metabolic response

hStable/progressive metabolic disease

iStable/progressive metabolic disease or stable/increase in mN stage

jComplete/partial metabolic response or decrease in mN stage

Prognostic ability of metabolic nodal response to predict pathological nodal response

Analysis of metabolic nodal parameters (Table 4) demonstrated that percentage change of nodal SUVmax was more accurate than mN stage for predicting pNR or pathological node negativity (pN −) (SUVmax concordant n = 41, 56.9%; mN stage concordant n = 33, 45.8%). The combined category of mNR was equally as accurate as percentage change in nodal SUVmax alone.

Table 4.

Prognostic ability of metabolic response parameters in lymph nodes and metabolic nodal response (mNR) to predict pathological nodal response (pNR) in 72 patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection

| pNR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pN respondera | pN non-responderb | pN negative | p value | ||

| Δ Nodal SUVmax | Metabolic responderc | 19 (67.9%) | 3 (10.7%) | 6 (21.4%) | p < 0.001 |

| Metabolic non-responderd | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| mN negative | 6 (15.8%) | 14 (36.8%) | 18 (47.4%) | ||

| mN stage | Metabolic respondere | 11 (61.1%) | 3 (16.7%) | 4 (22.2%) | p = 0.002 |

| Metabolic non-responderf | 10 (62.5%) | 4 (25.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | ||

| mN negative | 6 (15.8%) | 14 (36.8%) | 18 (47.4%) | ||

| mNR | mN responderg | 19 (67.9%) | 3 (10.7%) | 6 (21.4%) | p < 0.001 |

| mN non-responderh | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| mN negative | 6 (15.8%) | 14 (36.8%) | 18 (47.4%) | ||

Italics denote a statistically significant p-value

aMandard 1–3

bMandard 4–5

cComplete/partial metabolic response

dStable/progressive metabolic disease

eDecrease in mN stage

fStable/increase in mN stage

gComplete/partial metabolic response or decrease in mN stage

hStable/progressive metabolic disease or stable/increase in mN stage

ROC analysis (Fig. 1) excluding patients with metabolically negative nodes (mN −) at baseline (n = 38) demonstrated an optimum nodal SUVmax decrease of 32.6% for predicting pNR or pathological node negativity. Using an SUVmax threshold of 30% to define mNR (Table 2), this demonstrated high sensitivity and PPV but relatively low specificity and NPV for predicting pNR or pN − (AUC 0.749, sensitivity 92.6%, specificity 57.1%, PPV 86.2%, NPV 66.7%, p = 0.010). There was significantly higher concordance when excluding mN − patients compared with the entire cohort (85.3% vs 56.9%). Three patients had missing pNR data so were excluded from nodal analysis.

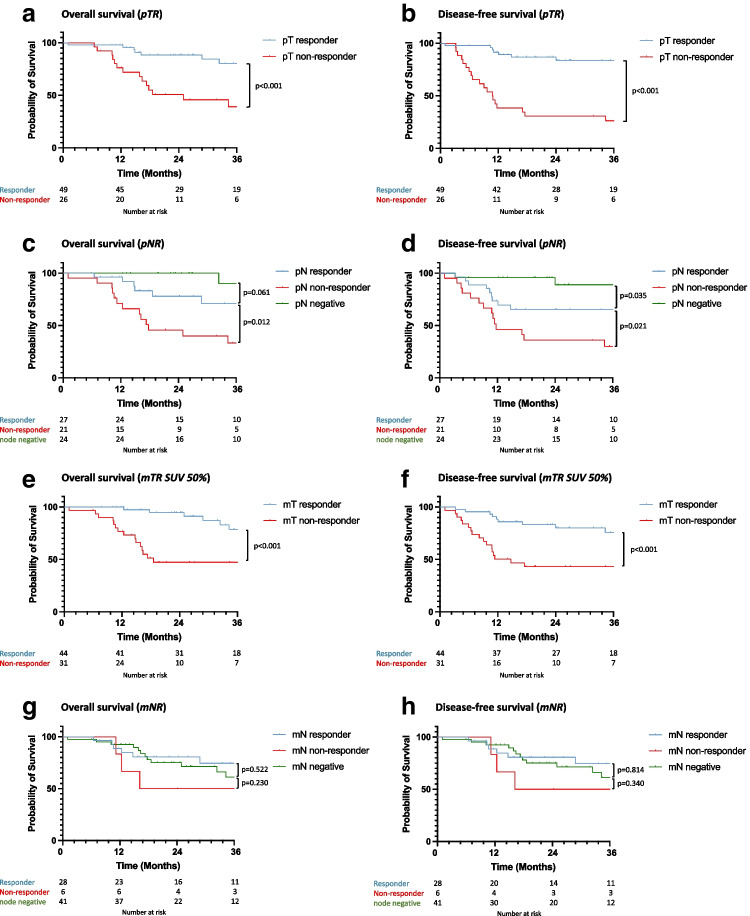

Prognostic effect of pathological response on survival

Kaplan–Meier (Fig. 2) and Cox regression survival analysis (Table 5) demonstrated better overall and disease-free survival in primary tumour pathological responders compared with non-responders (responder overall survival HR 0.10, 95% CI 0.03–0.34; disease-free survival HR 0.05, 95% CI 0.02–0.15). Pathological LN responders and patients with pathologically negative nodes had better survival than LN non-responders (responder overall survival HR 0.17, 95% CI 0.06–0.54; disease-free survival HR 0.28 (0.11–0.70); node negative overall survival HR 0.03, 95% CI 0.01–0.25; disease-free survival 0.05, 95% CI 0.01–0.26).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for overall and disease-free survival by pathological tumour response (pTR) (a + b), pathological nodal response (pNR) (c + d), metabolic tumour response (mTR) (e + f) and metabolic nodal response (mNR) (g + h) in 75 patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection

Table 5.

Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of overall and disease-free survival for metabolic tumour response (mTR), pathological tumour response (pTR), metabolic nodal response (mNR) and pathological nodal response (pNR) in 75 patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection. The accuracy of each mTR classification to predict survival was compared using Harrell’s C-index

| Overall survival | Disease-free survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusteda | Crude | Adjusteda | ||

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

|

mTR PERCIST |

Non-responderb | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Responderc | 0.45 (0.18–1.12) | 0.50 (0.17–1.45) | 0.39 (0.18–0.85) | 0.41 (0.18–0.97) | |

| C-index | 0.584 | 0.764 | 0.586 | 0.728 | |

| mTR MUNICON | Non-responderb | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Responderc | 0.35 (0.15–0.82) | 0.30 (0.10–0.84) | 0.33 (0.16–0.71) | 0.31 (0.13–0.73) | |

| C-index | 0.639 | 0.788 | 0.621 | 0.738 | |

|

mTR SUV 50% |

Non-responderb | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Responderc | 0.19 (0.08–0.50) | 0.17 (0.06–0.48) | 0.25 (0.11–0.55) | 0.24 (0.10–0.58) | |

| C-index | 0.732 | 0.831 | 0.679 | 0.773 | |

| pTR | Non-responderd | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Respondere | 0.22 (0.09–0.54) | 0.10 (0.03–0.34) | 0.12 (0.05–0.29) | 0.05 (0.02–0.15) | |

| mNR | Non-responderf | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Responderg | 0.40 (0.10–1.61) | 0.16 (0.03–0.69) | 0.57 (0.16–2.13) | 0.19 (0.04–0.90) | |

| Node negative | 0.56 (0.15–2.00) | 0.30 (0.08–1.21) | 0.64 (0.18–2.24) | 0.32 (0.08–1.32) | |

| pNR | Non-responderd | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Respondere | 0.31 (0.12–0.82) | 0.17 (0.06–0.54) | 0.39 (0.17–0.89) | 0.28 (0.11–0.70) | |

| Node negative | 0.05 (0.01–0.39) | 0.03 (0.01–0.25) | 0.09 (0.02–0.37) | 0.05 (0.01–0.26) | |

aAdjusted for: age, sex, chemotherapy regimen (FLOT/ECX), cT stage (cT0–2, cT3–4), cN stage (cN0, cN +), differentiation (well-mod, poor), signet ring cell (yes, no)

bStable/progressive metabolic disease

cComplete/partial metabolic response

dMandard 4–5

eMandard 1–3

fStable/progressive metabolic disease or stable/increase in mN stage

gComplete/partial metabolic response or decrease in mN stage

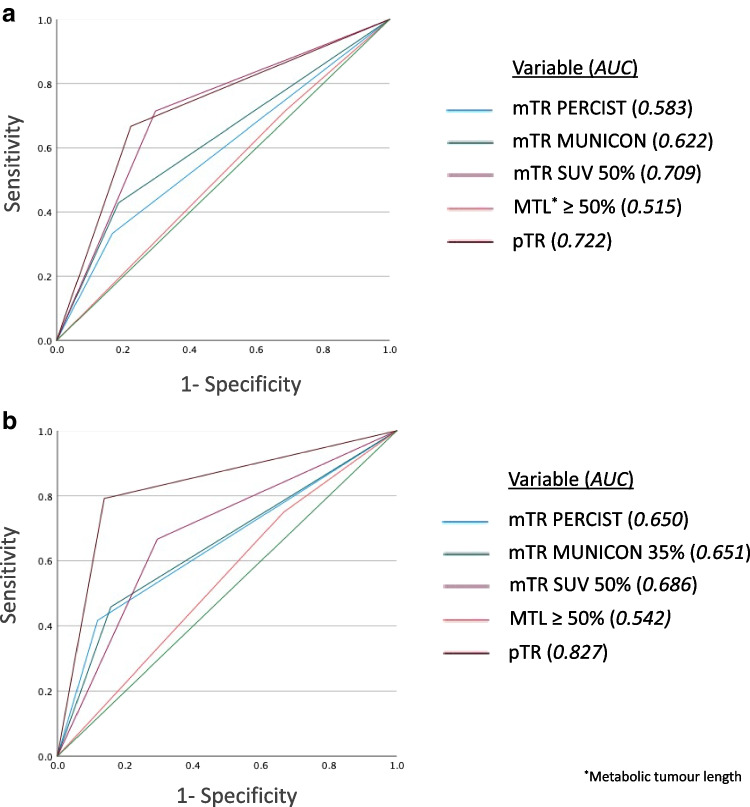

Prognostic effect of metabolic response on survival

Metabolic responders in the primary tumour demonstrated better overall and disease-free survival compared with non-responders using all SUVmax thresholds of mTR. However, when survival models were compared using Harrell’s C-index (Table 5), SUV 50% demonstrated the best predictive ability for overall and disease-free survival in both crude and adjusted analyses compared with PERCIST and MUNICON criteria. ROC analysis for metabolic and pathological tumour characteristics (Fig. 3) demonstrated pTR to be the best predictor of recurrence and survival, and SUV 50% was the second best predictor.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis evaluating the prognostic effect of metabolic tumour response (mTR) parameters and pathological tumour response (pTR) on survival (a) and recurrence (b) in 75 patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection

Metabolic nodal responders demonstrated improved survival compared with non-responders on adjusted analysis (responder overall survival HR 0.13, 95% CI 0.02–0.66; disease-free survival HR 0.19, 95% CI 0.04–0.90; node negative overall survival HR 0.30, 95% CI 0.08–1.21; disease-free survival 0.32, 95% CI 0.08–1.32). No other confounders in the adjusted model were prognostic for survival.

Discussion

In this study, metabolic response on FDG PET-CT after neoadjuvant chemotherapy was predictive of pathological response in both the primary tumour and LN metastases of patients with adenocarcinomas of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction. Patients who had a favourable metabolic or pathological response in the primary tumour or LNs had improved survival compared to non-responders.

Some methodological issues deserve attention. This study allowed for the long-term follow-up of a consecutive cohort of patients treated for oesophago-gastric adenocarcinoma and compared FDG PET-CT response with pathological LN response, making these results novel. Although most data were collected prospectively, the observational design made it difficult to exclude confounding. However, the results were adjusted for the key prognostic factors to counteract this. As a single-centre study, one advantage was that there was consistency of pathological and radiological reporting. This reduced heterogeneity; however, the single-centre design reduced the generalisability of the findings compared to a population-based approach. Although most patients had FDG PET-CT performed on the same scanner, the inclusion of 14 patients who did not may have introduced bias due to potential differences in SUVmax measurements and calibration between scanners. However, stratified analysis revealed no obvious differences in clinicopathological, response or survival results between these patients.

It has been suggested that commonly utilised thresholds of SUVmax are not optimal for assessing response to neoadjuvant therapy in oesophageal cancer, with higher cut-offs proposed [5, 16, 17]. This is supported by the results of the present study which suggest a reduction in SUVmax of 50% in the primary tumour was a better predictor of not only pathological response but also tumour recurrence and survival compared with PERCIST (ΔSUVmax 30%) and MUNICON (ΔSUVmax 35%). Although increasing the SUVmax threshold to 50% slightly decreased the sensitivity for predicting pathological response compared with PERCIST and MUNICON, it significantly increased the specificity and, overall, correctly identified pathological response in more patients. In this study, change in SUVmax was more accurate than change in metabolic tumour length for predicting pathological response and survival. However, advances in FDG PET-CT allowing calculation of three-dimensional spatial metrics such as metabolic tumour volume and total lesion glycolysis may provide even more reliable prognostic information [5]. Although such metrics were not calculated for the present study due to technical limitations, these results are still relevant since change in SUVmax remains the most reproducible and widely utilised metabolic parameter for response assessment.

The prognostic ability of FDG PET-CT to identify pathologic nodal disease was relatively poor. Approximately half of patients with metabolic negative nodes on baseline and restaging FDG PET-CT had pathological positive nodes, approximately a quarter of the patients in the entire cohort. This is not unexpected given that false-negative observations are well recognised, particularly with respect to small LNs due to a combination of limited tumour burden (insufficient to generate a detectable PET signal) and size below the spatial resolution of PET. When patients with metabolic negative nodes were excluded from response analysis to counteract the high false-negative rate, concordance, sensitivity and positive predictive value of mNR for predicting pNR or pathological node negativity were high, although specificity and negative predictive value remained low. Interestingly, there was also a false-positive rate of just over 10%, i.e. patients with metabolically positive but pathologically negative nodes, a finding which might be explained by post-treatment inflammation, also a well-recognised pitfall in FDG PET-CT interpretation.

The results of the present study support the findings of several previous studies demonstrating that a decrease in metabolic activity in the primary tumour following chemotherapy predicts pathological response [5, 18] and survival [3, 9, 19]. However, to our knowledge, only two studies from the same institution have evaluated the association between mNR and these outcomes [3, 5], with similar results obtained. Furthermore, no previous studies have evaluated the ability of FDG PET-CT to predict pathological nodal response. This is despite recent findings suggesting it is an independent predictor of survival and evidence of a discrepancy, 23% in this study, between patients who demonstrate a nodal response in the absence of a response in the primary tumour [6, 7]. The use of FDG PET-CT in assessing response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with oesophageal or junctional adenocarcinoma remains an under-researched area, and a large-scale study is needed to establish optimum response thresholds and its prognostic effect on pathological response and survival. Although this analysis focused on FDG PET-CT response after completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, at which point treatment alteration would not generally be considered, recent studies have evaluated early response assessment after induction chemotherapy in patients undergoing chemoradiation, with promising results [20]. Further research is warranted into whether FDG PET-CT performed earlier in the treatment pathway could be used to tailor individual treatment strategies in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that metabolic response on FDG PET-CT was predictive of pathological response in both the primary tumour and LNs in a cohort of patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or oesophago-gastric junction treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection. However, a relatively high false-negative rate makes metabolic evaluation of pathological nodal response challenging. Metabolic tumour response, pathological tumour response, metabolic nodal response and pathological nodal response were all independent prognostic factors for survival.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Collaborators

Guy’s and St Thomas’ Oesophago-gastric Research Group: A. Jacques, N. Griffin, V. Goh, S. Ngan, K. Owczarczyk, A. Sita-Lumsden, A. Qureshi, F. Chang, U. Mahadeva, B. Gill-Barman, S. George, M. Ong, J. Waters, M. Cominos, T. Sevitt, O. Hynes, G. Tham, J. M. Dunn, and S. S. Zeki.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CI

Confidence interval

- CMR

Complete metabolic response

- ECX

Epirubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine

- FDG

2-Deoxy-2[18F]fluoro-d-glucose

- FLOT

Fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin and docetaxel

- HR

Hazard ratio

- LN

Lymph node

- mN stage

Metabolic nodal stage

- mNR

Metabolic nodal response

- mTR

Metabolic tumour response

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- OR

Odds ratio

- PERCIST

PET Response Criteria in Solid Tumours

- PET-CT

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- PMD

Progressive metabolic disease

- PMR

Partial metabolic response

- pNR

Pathological nodal response

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- pTR

Pathological tumour response

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- ROI

Region of interest

- SMD

Stable metabolic disease

- SUVmax

Maximum standardised uptake value

- TNM

Tumour, nodes and metastases

Funding

The authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Mr. Andrew Davies.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and biometry

Dr. Aida Santaolalla and Professor Mieke Van Hemelrijck (King’s College London) kindly provided statistical advice for this manuscript.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Methodology

• Prospective

• observational

• performed at one institution

Footnotes

Jonathan L. Moore and Manil Subesinghe contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jonathan L. Moore, Email: Jonathan.moore13@nhs.net

On behalf of the Guy’s and St Thomas’ Oesophago-gastric Research Group:

A. Jacques, N. Griffin, V. Goh, S. Ngan, K. Owczarczyk, A. Sita-Lumsden, A. Qureshi, F. Chang, U. Mahadeva, B. Gill-Barman, S. George, M. Ong, J. Waters, M. Cominos, T. Sevitt, O. Hynes, G. Tham, J. M. Dunn, and S. S. Zeki

References

- 1.Miyata H, Yamasaki M, Makino T, et al. Impact of number of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose-PET-positive lymph nodes on survival of patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery for oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2016;103(1):97–104. doi: 10.1002/BJS.9965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Findlay JM, Gillies RS, Franklin JM, et al. Restaging oesophageal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy with 18F-FDG PET-CT: identifying interval metastases and predicting incurable disease at surgery. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(10):3519–3533. doi: 10.1007/S00330-016-4227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Findlay JM, Bradley KM, Wang LM, et al. Metabolic nodal response as a prognostic marker after neoadjuvant therapy for oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2017;104(4):408–417. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foley K, Findlay J, Goh V. Novel imaging techniques in staging oesophageal cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;36–37:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Findlay JM, Bradley KM, et al. Predicting pathologic response of esophageal cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: the implications of metabolic nodal response for personalized therapy. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(2):266–275. doi: 10.2967/JNUMED.116.176313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies AR, Myoteri D, Zylstra J, et al. Lymph node regression and survival following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2018;105(12):1639–1649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans RP, Kamarajah SK, Kunene V, et al. Impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on nodal regression and survival in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;0(0). 10.1016/J.EJSO.2021.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Noorani A, Li X, Goddard M, Crawte J, et al. Genomic evidence supports a clonal diaspora model for metastases of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2020;52(1):74. doi: 10.1038/S41588-019-0551-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lordick F, Ott K, Krause BJ, et al. PET to assess early metabolic response and to guide treatment of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction: the MUNICON phase II trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(9):797–805. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, et al. Response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(Suppl 1):122–150. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber WA, Ott K, Becker K, et al. Prediction of response to preoperative chemotherapy in adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction by metabolic imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(12):3058–3065. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.12.3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). TNM classification of malignant tumours - eighth edition. J B, editor. Wiley Blackwell

- 13.Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction - classification , pathology and extent of resection Tumor Type Adeno Ca of the Distal Esophagus True Ca Cardia Anatomical. 1996;173–82

- 14.Mandard FJ , Dalibard JC, Mandard J, et al. 1994 Pathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. Clinicopathologic Correlations. Cancer.73(11) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Textor J, Van Der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS, et al. Software application profile robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package “dagitty”; 10.1093/ije/dyw341 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Downey RJ, Akhurst T, Ilson D, et al. Whole body 18FDG-PET and the response of esophageal cancer to induction therapy: results of a prospective trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(3):428–432. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim MK, Ryu JS, Kim SB, et al. Value of complete metabolic response by (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography in oesophageal cancer for prediction of pathologic response and survival after preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(9):1385–1391. doi: 10.1016/J.EJCA.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillies RS, Middleton MR, Blesing C, et al. Metabolic response at repeat PET/CT predicts pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in oesophageal cancer. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(9):2035–2043. doi: 10.1007/S00330-012-2459-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ott K, Weber WA, Lordick F, et al. Metabolic imaging predicts response, survival, and recurrence in adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(29):4692–4698. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman KA, Ou FS, Hall NC, et al. Randomized phase II study of PET response-adapted combined modality therapy for esophageal cancer: mature results of the CALGB 80803 (Alliance) Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(25):2803–2815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.