Abstract

Leishmaniasis as a widespread neglected vector-borne protozoan disease is a major public health concern in endemic areas due to 12 million people affected worldwide and 60,000 deaths annually. Several problems and side effects in using current chemotherapies leads to progression of new drug delivery systems against leishmaniasis. For instance, layered double hydroxides (LDHs) so-called anionic clays due to their proper characteristics, have been considered recently. In the present study, LDH nanocarriers were prepared using co-precipitation method. Then, the intercalation reactions with amphotericin B were conducted via indirect ion exchange assay. Finally, after characterization of prepared LDHs, the anti-leishmanial effects of Amp-Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites against Leishmania major were evaluated using an in vitro and in silico model. According to results, current study demonstrated that Zn/Al–NO3 LDH nanocarriers can be used as a new promising delivery system by intercalating amphotericin B into its interlayer space for leishmaniasis treatment by eliminating the L. major parasites by remarkable immunomodulatory, antioxidant and apoptotic effects.

Keywords: Layered double hydroxides, Leishmaniasis, Amphotericin B, Drug delivery

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Leishmaniasis as a widespread neglected vector-borne protozoan disease is a major public health concern in endemic areas due to 12 million people affected worldwide and 60,000 deaths annually [1,2]. Wide range of mammalian hosts, including humans and animals can be infected by several species of parasites of the genus Leishmania transmitted through the bite of infected female phlebotomine sandflies [3,4]. According to the fatality rates, leishmaniasis is the third highest among all the neglected tropical diseases after sleeping sickness and chagas disease [5]. Moreover, co-infection of AIDS or malaria with leishmanial infection has a significant importance in regions where both infections are endemic [6,7]. In order to three main types of this disease including visceral leishmaniasis (Kala-azar) (VL), which is the deadliest form, cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) as the most prevalent form and mucosal leishmaniasis (ML), different manifestations can occur [8]. The life-long scars generated by cutaneous form can lead to serious social stigma or other mental health disorders including depression and anxiety [9]. Based on the previous studies, among all the species, L. major and L. tropica are the two most common species that cause cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Middle East, Africa, and India [10]. Leishmaniasis is endemic in 88 Tropical and subtropical countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Afghanistan, Syrian, Algeria, Iran, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia with 1.5–2 million new cases annually. According to world health organization (WHO) reports, approximately 500,000 and 1 to 1.5 million of these new cases are consisted of VL and CL, respectively [11,12]. The current chemotherapies including Pentavalent antimonials (Sb or SbV) as the first line drugs and gold standard, amphotericin B as the second line, miltefosine, paromomycin and pentamidine have series of limitations. In recent years, several problems such as high resistance, failures in treatment, high cost, parenteral administration and pain at the injection site, restriction for using in pregnant women and the elderly people, side-effects like cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity lead to improvement of new drug delivery systems against leishmaniasis [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]]. By improvement of nanotechnologies, new chemotherapies and drug delivery systems have been considered and used for treatment of leishmaniasis in order to enhance the pharmacokinetic properties, efficacy, target delivery effect, releasing drugs under controlled system and long-term lifetime of systemic circulation of their entrapped drugs [19,20]. Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) so-called anionic clays due to their features have recently attracted considerable attention. For instance, simplicity of laboratorial preparation using water as solvent, structural and morphological tunability, low toxicity, inexpensive, dispersibility in water, generating ions which can be found in the human body [21]. The normalized formula for all these structures is: [M2+1-xM3+x (OH)2][An−]x/n·mH2O, while M+2 is a divalent metal like Mg2+, Zn2+ or Ni2+, M+3 a trivalent metal such as Al3+, Ga3+, Fe3+ or Mn3+ and A-n is an inorganic (NO3−) or organic (RCO2-) anion n valent, and x ranges from 0.2 to 0.4 [[22], [23], [24]]. These nanostructures consist of cationic brucite-like layers and anions and water molecules in an interlayer gallery in order to counterbalance the positive charge [25]. LDH nanoparticles as a biocompatible drug delivery carrier are easily internalized into the cells through endocytosis. It is the characteristic that specifies its application as a suitable platform in clinical therapy [26,27]. In addition, acting as a protective shield by their inorganic sheets from tissue damage, acting as a reservoir (i.e., as extended release systems) of the guest species without any transfiguration or change in integrity of intercalated guest structure lead to intercalate various chemical compounds including cardiovascular [28], anti-inflammatory [29], anti-cancer [30] and anti-leishmanial drugs [31] and other agents such as vitamins, fragrances and dyes into the LDH carriers in order to enhance their efficacy and other crucial properties [21,[32], [33], [34], [35]]. Among all the available methods for synthesis of drug-LDH including co-precipitation, ion-exchange, the calcination-reconstruction, hydrothermal and exfoliation-restacking, the co-precipitation and ion-exchange method is most frequently used for the synthesis of drug-LDH nanocomposites [[36], [37], [38]]. In the present study, after preparation of LDHs with Zn as divalent cation and Al as the trivalent one (Zn2+/Al3+ molar ratio 2:1) with co-precipitation method, the intercalation reactions with amphotericin B were conducted via indirect ion exchange method. Finally, the prepared Zn–Al LDHs were characterized, and their anti-leishmanial effects were evaluated against Leishmania major using an in vitro and in silico model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and equipment

All the reagents utilized in present study were used as received without any purification. Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO supplied the drug amphotericin B. Pure basic Zinc nitrate hexahydrate [Zn(NO3)2·6H2O], aluminium nitrate nonahydrate [Al(NO3)3·9H2O] and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. RPMI 1640 medium containing l-glutamine, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal calf serum (FCS), Pen/Strep, DPPH (2,20-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), BHA (Butylated hydroxyanisole) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich, France. To determine the particle size distribution and the hydrodynamic diameter the dynamic light scattering (DLS) was applied. In addition, Nano Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments, UK) was used to measure the surface charge of prepared nanostructures through a scattering angle of 90° at 25 °C. For this purpose, 2 mg of freeze-dried nano-powders were dissolved in 4 mL of Milli-Q water. In order to evaluated the morphology of the samples, Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM, ZEISS, SIGMA VP-500, Germany) was used. The UV–vis spectra of LDH precursor and Amp-LDH were compared using UV spectrometer S-3100 SCINCO.

2.2. Synthesis of Zn–Al LDHs carrier

In the present study, co-precipitation method was used to synthesize the Zn–Al LDHs precursor. For this purpose, a certain quantity of the metal salt solutions (Zn2+/Al3+ molar ratio 2:1) were mixed. Then 0.01 M NaOH solution was added dropwise to the reaction medium with magnetic stirring under nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature until pH = 8. Then, in order to eliminate the excess nitrate anions, centrifugation and repeated washing with deionized water were carried out. Finally, the white gelatinous Zn–Al LDHs precipitate was collected and reserved for characterization.

2.3. Synthesis of amp- Zn–Al LDHs binary system

Subsequently, ion exchange method was used to make the amphotericin B (Amp) incorporate into the interlayer of Zn–Al LDHs and conduct the intercalation reactions. For this purpose, 50 mg Amp was dissolved in 10 mL deionized water and gradually added to 10 mL of aqueous suspension containing 50 mg LDH precursor. The Amp- Zn–Al LDHs mixture was mixed using a magnetic stirrer for 2 h and the pH of the reaction medium was fixed in ∼8.5 by adding 0.01 M NaOH drop by drop. After centrifugation and 3 times washing with deionized water, the final product was used for further experiments.

3. 4. interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) functional residues

For this purpose, the “Hotspot” (https://loschmidt.chemi.muni.cz/hotspotwizard) and CASTp (http://sts.bioe.uic.edu/castp/calculation.html) softwares were used prior to docking to anticipate the functional residues hotspots within the structure of IFN-γ [[39], [40], [41]]. The integration of functional, evolutionary, and configurational datas were obtained from bioinformatics databases in order to be used in these softwares for in silico evaluations.

4. 5. surface configurational pockets assessment of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)

It seems critical to describe and measure superficial regions on 3-dimensional (3-D) configurations of IFN-γ prior to docking. In order to determine cavities buried inside proteins and pockets on protein surfaces, we used Molegro Virtual Docker software, which is a program to explore the cavity (Molegro 2011). Selected cavity position measurement was X:49.24, Y:0.15, and Z:49.25.

4.1. Protein-ligand docking

This study used PubChem CID 936 (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Amphotericin-b) to obtain 3-D form of amphotericin B. In addition, Protein Data Bank (PDB) (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/repository/uniprot/P01580?csm=7EE80BAECB42071A) was used to attain 3-D structure of IFN-γ. Molegro Virtual Docker software was used prior to the experimental studies in order to carry out the Molecular docking investigations. At the beginning, we performed docking within a confined space to study feasible binding spots. Docking configurations were selected based on the binding affinity. Graphical delineation was accomplished using Molegro Molecular Viewer 2.5.0 (Molegro ApS, Aarhus, Denmark).

4.2. Parasite and macrophage cell-line

Standard Iranian strain of L. major (MRHO/IR/75/ER) was obtained from Leishmaniasis Research Center (Kerman, Iran). Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium-1640 (RPMI-1640) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HFBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 IU/mL) antibiotics were used to culture the promastigotes and incubate them at 25 °C. The Pasteur Institute of Iran supplied murine macrophage cells J774 A.1 ATCC®TIB-67™. They were seeded and maintained in the Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) enriched with 10% HFBS and 1% Pen/Strep antibiotics and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

4.3. Anti-promastigote assay

In this study, the anti-promastigote activity of amphotericin B, ZnAl-LDH carriers alone and along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) was investigated using MTT test. At first step, 105 cells/mL of L. major promastigotes in the logarithmic growth phase were seeded in a 96-well microplate with RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS at final volume of 90 μL. Then, the promastigotes were treated in three sets with 10 μL of various concentrations (25, 50, 100 and 200 μg/mL) of the samples and incubated at 25 °C for 72 h. In the next step, after preparing and adding 10 μL of the MTT (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) at concentration of 5 mg/mL to each well, the promastigotes were incubated at 25 °C for 3 h. Finally, by adding DMSO the experimental reactions were stopped and OD absorbance was determined at 490 nm using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (Bio Tek-ELX800).

4.4. Anti-intramacrophage amastigote assay

This method was carried out in order to assess the leishmanicidal effects of ZnAl-LDH carriers alone and while mixed with intercalated amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) and conventional form of amphotericin B against intramacrophage amastigotes of L. major and measure the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50 values). Initially, 200 μL (106 cells/ml) of promastigotes in stationary phase were added to 200 μL (105 cells/ml) of murine macrophages at a ratio of 10:1 and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. After the adhesion of the macrophages (containing amastigotes) to the slides, successive washing with fresh RPMI-1640 medium was performed to remove the free promastigotes. In the next step, intramacrophage amastigotes were treated with various concentrations of Amp-ZnAl-LDH and amphotericin B (12.5, 25, 50 and 100 μg/mL) in triplicates and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 72 h. Finally, in order to study under a light microscope, methanol and Giemsa were used to fix and stain the dried slides, respectively. Activity of anti-intramacrophage amastigotes of the drugs were obtained by counting the number of amastigotes in each macrophage by examining 100 macrophages (% amastigotes viability) in comparison to macrophages containing amastigotes without any drugs as a positive control.

4.5. Cytotoxicity assay

In order to investigate the cytotoxicity effects on murine macrophage cells and calculate the CC50 (the 50% cytotoxic concentration), flow cytometry assay was carried out. For this purpose, after preparing various dilutions of amphotericin B, ZnAl-LDH carriers alone and mixed with intercalated amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH), the cells (1 × 106) were treated with the samples in duplicate and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 72 h. Then, the samples were washed three times with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and due to the manufacture's instruction of PE Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharnigen™), 500 μL of 1X binding buffer, 5 μL of Annexin V and 5 μL 7-AAD were added to micro tubes. Finally, after 15 min of incubation in dark, the percentages of cellular viability were determined using flow cytometer (BD FACSCalibur, San Jose, California, USA). Moreover, evaluating and comparing the safety of drugs were carried out by measuring the selectivity index (SI) using the following equation:

| SI (selectivity index) = CC50 (macrophages) / IC50 (amastigotes) | Eq. 1 |

4.6. Antioxidant assay

In order to determine the hydrogen atom or electron-donation ability of Zn–Al LDHs nanostructures, the scavenging activity of the purple-coloured methanol solution of 2,2ʹ-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) as a reagent was investigated. In this spectrophotometric assay, 5 mL of a 0.004% methanol solution of DPPH radical was used for adding to 50 μL of different dilutions of the samples in methanol. Then, the absorbance of samples was measured at 517 nm after incubation in the dark for 30 min and radical scavenging activity was measured by any reduction in the absorbance of DPPH mixture. Finally, the concentration required to inhibit 50% of DPPH (IC50) and the antioxidant level of ZnAl-LDH nano carriers and butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) as a positive control were calculated using following equation (Eq. 2):

| DPPH radical scavenging ability (%) = [A−B/A] × 100 | Eq. 2 |

Which A express the absorbance of the control reaction (prepared by replacing the test compounds with deionized water) and B express the absorbance of the test compounds.

4.7. Apoptosis assay

The current study used PE Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Pharnigen™) in order to assess the apoptotic and necrotic values of the L. major promastigotes. In brief, 1 × 106 L. major promastigotes were exposed to 100 μL of different concentrations (25, 50 and 100 μg/mL) of Amp-Zn-Al LDHs nanostructures and seeded in 1.5 mL micro tubes with RPMI-1640 and 10% FBS and incubated at 24 ± 1 °C for 72 h. As previously mentioned, after washing with PBS and adding 1X binding buffer, Annexin V and 7-AAD stains to each micro tube, they were placed in dark for 15 min. Finally, the early apoptosis [Annexin V (+), 7-AAD (−)], late apoptosis [Annexin V (+), 7-AAD (+)] and necrosis [Annexin V (−), 7-AAD (+)] were analyzed with Cell Quest software after reading by flow cytometer (BD FACSCalibur, San Jose, California, USA).

4.8. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

In the current study, real time PCR (qPCR) was utilized on L. major intra-macrophage amastigotes in order to determine the expression levels of interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin-12 (IL-12p40), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS gene), transforming growth factor (TGF- β) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) compared to the expression profile of GAPDH as a reference gene. Initially, after exposing of J774-A1 cell line to the various concentrations of Amp-ZnAl-LDH and amphotericin B, RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, USA) was used to extract total RNA of the samples according to the manufacturer's instructions. Afterward, the quality and concentration (ng/μL) of extracted RNA were investigated by OD's measurement using spectrophotometer (NanoDrop ND-1000, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). Then, cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription of 500 ng RNA using Takara Prime Script™ RT reagent kits (Takara Bio, Inc., Japan). Finally, the qPCR reaction was executed in duplicate using 7.5 μL SYBR Green master mix (SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II, Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan), 2 μL cDNA diluted in 3.5 μL RNase-free H2O and 2 μL of forward and reverse primer with Rotor-Gene Cycler (Rotor-Gene 3000 cycler, Corbett, Sydney, Australia) by following template: 95 °C for 1 min, then, 40 three-step rounds of 10 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 58 °C and 20 s at 72 °C for cDNA augmenting, primer annealing and extension, respectively and 65 °C for 1 min for final step. Sequences of the specific primers and reference genes indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of the specific primers and reference genes.

| Gene | Forward sequence (5′–3′) | Reverse sequence (5′–3′) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-12 P40 | TGGTTTGCCATCGTTTTGCTG | ACAGGTGAGGTTCACTGTTTCT | 171 |

| IL-10 | CTTACTGACTGGCATGAGGATCA | GCAGCTCTAGGAGCATGTGC | 134 |

| iNOS | ACATCGACCCGTCCACAGTAT | CAGAGGGGTAGGCTTGTCTC | 89 |

| TGF-β | CCACCTGCAAGACCATCGAC | CTGGCGAGCCTTAGTTTGGAC | 112 |

| IFN-γ | ACAGCAAGGCGAAAAAGGATG | TGGTGGACCACTCGGATGA | 106 |

| GAPDH | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA | 95 |

2−ΔCt method was used to ascertain gene expression level and in order to calculate the ΔCT, the following equation was utilized: [ΔCT = CT (target) - CT (reference)]. Also, comparative threshold method (2–ΔΔCT) was employed to measure the fold increase (FI).

4.9. Statistical analysis

In this study, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's post-hoc test were used to investigate the differences between the treatment groups and analyze the Statistical data using in SPSS software ver. 20 (Chicago, Illinois, USA). In addition, for designing the graphs and analyzing the mean of 2−ΔCt for the treatment and control groups GRAPHPAD PRISM 6 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, California, USA) was utilized. Also, Following the calculation of the IC50 and CC50 values by probit analysis in SPSS software, we determined the selectivity index (SI) using the equation as mentioned previously (Eq. (1)). For all the experiments, P < 0.05 was statistically considered significant.

5. Results

5.1. Characterization

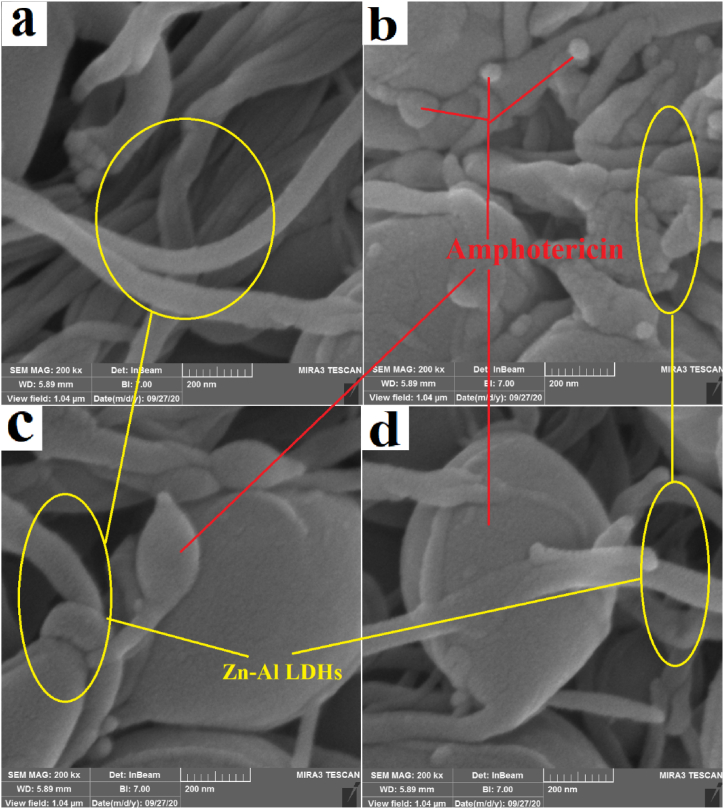

In this study, the zeta potential of prepared Amp-Zn-Al LDHs nanocomposites were calculated aiming to determine the electrostatic charge of the surface of particles [42]. This charge of the surface plays a significant role in physical stability of nanocomposites and adherence of them to other biological surfaces. According to Table 2, the calculated zeta potential of Amp-ZnAl-LDH is 2.09 mV. This positive charge of nanocomposites can lead to better electrostatic interaction with negatively charged microbial surfaces. Besides, positively charged nanocarriers are more quickly taken up by macrophages and other phagocytic cells via phagocytosis and accumulated about twice more in mononuclear phagocytes [[43], [44], [45]]. The results of microscopic SEM (scanning electron microscopy) imaging show that after a period of 1 month from the preparation of Amp-Zn-Al LDHs nanocomposites gradually Amphotericin B structures grow in Zn–Al LDHs nanocomposites. The results of scanning electron microscopy images for the Zn–Al LDHs and Amp-Zn-Al LDHs after 1day, after 1 week and after 1 month are given in Fig. 1a, b, 1c and 1d, respectively.

Table 2.

Zeta potential measurement of LDH carrier containing amphotericin B (Amp-Zn/Al-LDH).

| Amp-ZnAl-LDH |

Raw |

Fit |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Valid | μ (μm.cm/V.s) | ς (mV) | μ (μm.cm/V.s) | σ | ς (mV) | σ |

| Average | 0 | 0 | 0.35 | −5.12 | 2.09 | −30.32 | |

| 1 | −2.23 | −13.22 | 0.27 | −6.77 | 1.57 | −40.1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.49 | −4.95 | 2.92 | −29.33 | |

| 3 | – | 0 | 0 | 0.51 | −4.24 | 3.02 | −25.09 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 | −4.28 | 0.84 | −25.37 | |

| 5 | 2.23 | 13.22 | 0.19 | −5.86 | 1.1 | −34.71 | |

| 6 | – | 0 | 0 | 0.52 | −4.61 | 3.08 | −27.33 |

Fig. 1.

SEM images of the Zn–Al LDHs (a) amphotericin B anions intercalated into the interlayer space of Zn–Al LDHs nanocomposites after 1day (b) after 1 week (c) after 1 month (d).

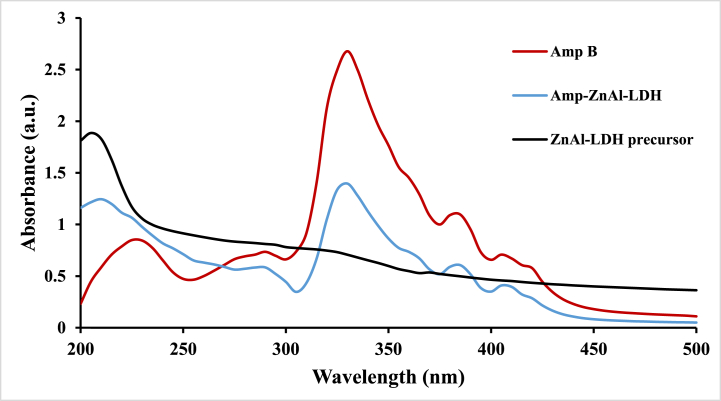

In order to evaluate the intercalation of amphotericin B into the ZnAl-LDH carrier UV–vis spectrophotometry was used, which is a very simple method. Similar to other literature, the results of UV–vis spectroscopy show a strong absorption for ZnAl-LDH precursor in the near-ultraviolet region, which is decreased gradually by increasing in the wavelength of light [46]. As indicated in Fig. 2, the absorption spectra of aqueous amphotericin B suspension (Amp B), ZnAl-LDH precursor and Amp-ZnAl-LDH samples were determined. Due to the results, the both Amp and Amp-ZnAl-LDH demonstrated a strong absorption at 330 nm and no absorption was found in the visible region in agreement with previous studies [47]. There were no significant differences between them. According to the comparison of the UV–vis spectra of Amp and Amp-ZnAl-LDH, it can be concluded that there are no significant differences between them. These results can verify the successful intercalation of amphotericin B into the LDH matrix.

Fig. 2.

UV–vis spectra of the Amp, Zn–Al LDHs precursor and Amp-ZnAl-LDH samples.

The result of X-Ray diffraction analysis (XRD) shows that in the case that the structures of ZnAl-LDH were examined alone, no peaks are observed (Fig. 3A), and when the structures of amphotericin B are preserved, the peaks at XRD pattern are clearly observed (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

XRD pattern of the ZnAl-LDH structures (A) and ZnAl-LDH structures containing amphotericin B (B).

As can be seen from Fig. 4, the prepared niosomes were in a narrow size range during a period of 6 months. The obtained results from Dynamic light scattering analysis (DLS) revealed that there was no significant size alteration, and particles remained in the nanometer range (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

The size distribution changes of ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) during storage at 4-8 °C as an indicator of physical stability of particles.

Table 3.

Checked points for the evaluation of physical stability of LDH carriers containing amphotericin B (Amp-Zn/Al-LDH) during storage at 4–8 °C.

| Formulation | Vesicle size (μm) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 week | 1 month | 3 months | 6 months | |

| Amp-ZnAl-LDH | 11.23 ± 0.71 | 8.49 ± 1.38 | 7.87 ± 1.10 | 10.15 ± 0.83 |

5.2. Docking

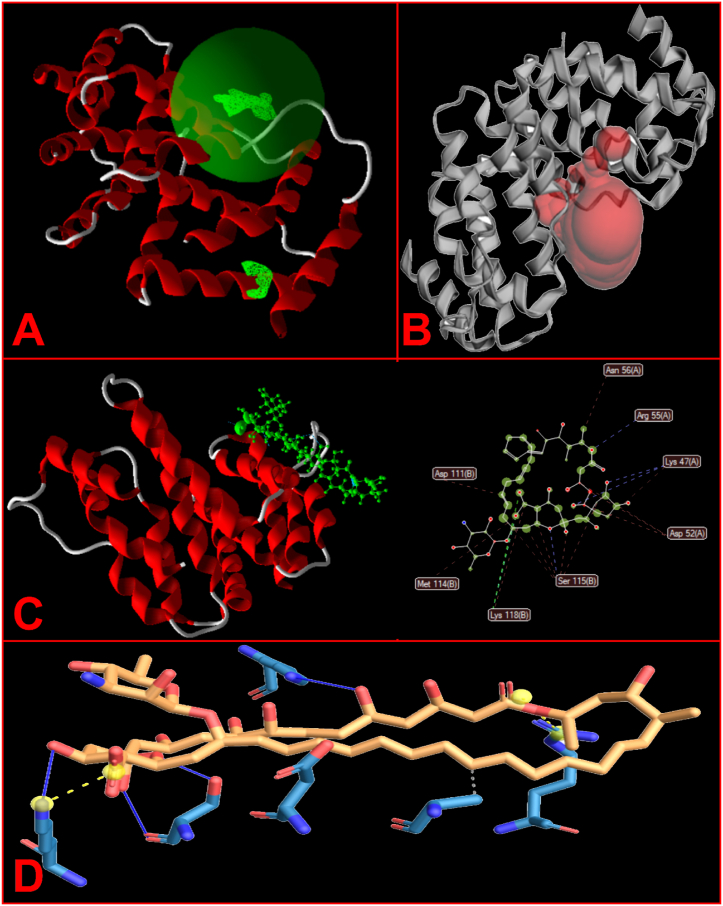

Based to the results of Hotspot software, we predicted amino acids Val 44, Leu 49, Phe 50, Trp 54, and Leu 98 as variable residues in catalyst pockets and disposal tunnels. In order to illustrate the hydrophobic cavities and residues and hydrogen bonds between ligand and target protein as the main forces of ligand-protein binding energy, the 2-D interaction diagrams was assessed. Moreover, Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) websites revealed the interplay between the IFN-γ and amphotericin B. According to the steric interplays, amphotericin B binds with GLN 69, SER 72, PHE 73, LEU 75, ARG 76, GLU 79, VAL 80, ILE 116, ALA117, LYS 118, PHE 119, GLU 120, VAL 121, ASN 122, GLU 95, MET 114 amino acids of IFN-γ, respectively (Fig. 5B). Functional study of IFN-γ structure demonstrated that IFN-γ be made up 5 cavities, which one of them is central (Fig. 5A). In the present study, Molecular docking was carried out in order to predict the affinity of amphotericin B to protein IFN-γ targets. IFN-γ residues/molecules contribution indicated in Table 4. Findings demonstrated that amphotericin B fastens to IFN-γ residues (Fig. 5D) at the active spots (Asp, Met, Lys, Ser, Arg and Asn) (Table 5 and Fig. 5C). Moreover, a MolDock score of −164.287 kcal/mol was obtained (Table 6).

Fig. 5.

Docking. A) IFN-γ consists of a central pocket and 4 cavities. B) amphotericin B (Amp B) binds to IFN-γ with the active site residues by LIGPLOT program. C) Molecular docking by Molegro Virtual Docker software. D) Predicted amino acids in pocket formation by PLIP web tool.

Table 4.

IFN-γ residues/molecules Contribution.

| Index | Residue | AA | Distance | Ligand Atom | Protein Atom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 B | VAL | 3.03 | 1970 | 287 |

| 2 | 49 B | LEU | 3.09 | 1965 | 366 |

| 3 | 50 B | PHE | 3.68 | 1959 | 385 |

| 4 | 50 B | PHE | 3.01 | 1961 | 388 |

| 5 | 54 B | TRP | 3.83 | 1950 | 456 |

| 6 | 98 B | LEU | 2.75 | 1991 | 1199 |

Table 5.

Hydrogen bonds for amp-ZnAl-LDH

| Index | Residue | AA | Distance H-A | Distance D-A | Donor Angle | Donor Atom | Acceptor Atom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54 B | TRP | 2.27 | 2.67 | 100.97 | 459 [Nar] | 2006 [O.co2] |

| 2 | 67 B | GLN | 3.45 | 3.82 | 103.03 | 1989 [N3] | 691 [O2] |

| 3 | 67 B | GLN | 1.82 | 2.81 | 160.72 | 692 [Nam] | 1995 [O.co2] |

| 4 | 74 B | TYR | 1.86 | 2.88 | 169.77 | 2002 [O3] | 809 [O3] |

| 5 | 74 B | TYR | 1.70 | 2.68 | 157.49 | 809 [O3] | 2001 [O3] |

| 6 | 74 B | TYR | 1.80 | 2.68 | 141.71 | 2001 [O3] | 809 [O3] |

| 7 | 101 B | THR | 2.49 | 3.07 | 114.74 | 1249 [O3] | 1990 [O3] |

| 8 | 101 B | THR | 2.11 | 3.07 | 152.86 | 1990 [O3] | 1249 [O3] |

Table 6.

Contribution of the IFN-γ residues/molecules.

| Hydrophobic InteractionsHydrophobic Interactions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | Residue | AA | Distance | Ligand Atom | Protein Atom | ||

| 1 | 108 B | ALA | 3.27 | 3929 | 3325 | ||

| 2 |

111 B |

ASP |

2.93 |

3924 |

3379 |

||

| Hydrogen Bonds | |||||||

| Index |

Residue |

AA |

Distance H-A |

Distance D-A |

Donor Angle |

Donor Atom |

Acceptor Atom |

| 1 | 47 A | LYS | 2.14 | 3.05 | 145.92 | 361 [N3+] | 3967 [O3] |

| 2 | 115 B | SER | 1.64 | 2.63 | 159.69 | 3439 [O3] | 3917 [O3] |

| 3 | 115 B | SER | 2.60 | 3.25 | 121.23 | 3957 [O3] | 3437 [O2] |

| 4 |

118 B |

LYS |

2.63 |

3.11 |

108.26 |

3482 [N3+] |

3958 [O3] |

| Salt Bridges | |||||||

| Index |

Residue |

AA |

Distance |

Ligand Group |

Ligand Atoms |

||

| 1 | 55 A | ARG | 5.08 | Carboxylate | 3940, 3965 | ||

| 2 | 118 B | LYS | 3.09 | Carboxylate | 3971, 3960 | ||

5.3. Anti-promastigote assay

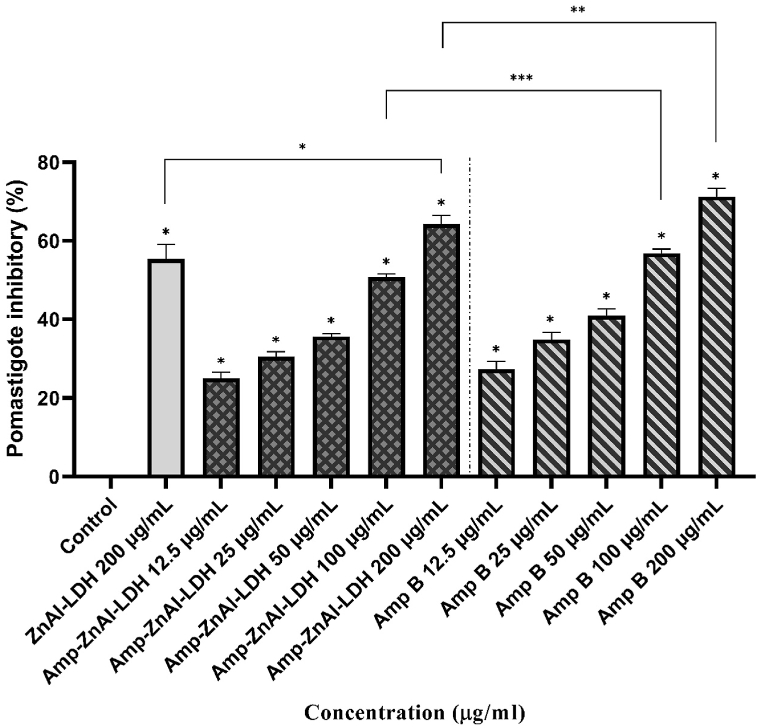

The mean inhibition rates of L. major promastigotes exposed to different concentrations (12.5, 25, 50, 100 and 200 μg/mL) of amphotericin B (Amp B), ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) in comparison to ZnAl-LDH precursor and negative control are presented in Fig. 6. According to the results, a dose-dependent anti-leishmanial effect was observed for both Amp and Amp-ZnAl-LDH on the L. major promastigotes compared to negative control (P < 0.001). The IC50 values for Amp B and Amp-ZnAl-LDH were obtained 65.36 ± 10.86 and 111.14 ± 8.28 μg/mL, respectively, which indicates that Amp B had a significantly better leishmanicidal effect than Amp-ZnAl-LDH (P < 0.01). However, at the concentration of 100 μg/mL the inhibitory rate of Amp-ZnAl-LDH was significantly higher than ZnAl-LDH carrier (P < 0.001) and there were no significant differences between the Amp B and Amp-ZnAl-LDH nanocomposites at the similar concentrations except the concentrations of 100 and 200 μg/mL (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

The mean inhibition rates of L. major promastigotes exposed to different concentrations of amphotericin B (Amp B), ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) in comparison to ZnAl-LDH precursor and negative control by colorimetric assay (*P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.05).

5.4. Anti-intramacrophage amastigote assay

Table 7 shows the mean number of L. major amastigotes in the macrophages after treatment with various concentrations (12.5, 25, 50 and 100 μg/mL) of amphotericin B (Amp B), ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) in comparison to untreated control. For both Amp B and Amp-ZnAl-LDH, a significant decrease was demonstrated in the quantity of amastigotes in a dose-response manner compared to untreated control. According to comparison of the IC50 values of Amp-ZnAl-LDH (21.05 ± 1.14 μg/mL) and Amp B (25.41 ± 0.90 μg/mL), it can be concluded that Amp-ZnAl-LDH had significantly higher inhibitory effects in comparison to Amp B against amastigote form of L. major (P < 0.01). Moreover, further results displayed that the combination of amphotericin B and ZnAl-LDH had more inhibitory effects than its carrier only (ZnAl-LDH) against the amastigotes of L. major at concentration of 100 μg/mL (P < 0.001).

Table 7.

The average number of intra-macrophage amastigotes treated with different concentrations of amphotericin B (Amp B), ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) in comparison to Untreated control after 72 h.

| Concentrations (μg/mL) | Amp-ZnAl-LDH |

Amp B |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P-value | Mean ± SD | P-value | |

| 0 (Untreated control) | 43 ± 0.58 | NR | 43 ± 0.58 | NR |

| 12.5 | 32 ± 1.07 | P < 0.001 | 35 ± 1.16 | P < 0.001 |

| 25 | 17 ± 0.26 | P < 0.001 | 22 ± 2.38 | P < 0.001 |

| 50 | 6 ± 1.53 | P < 0.001 | 10 ± 0.97 | P < 0.001 |

| 100 | 3 ± 0.43 | P < 0.001 | 5 ± 0.6 | P < 0.001 |

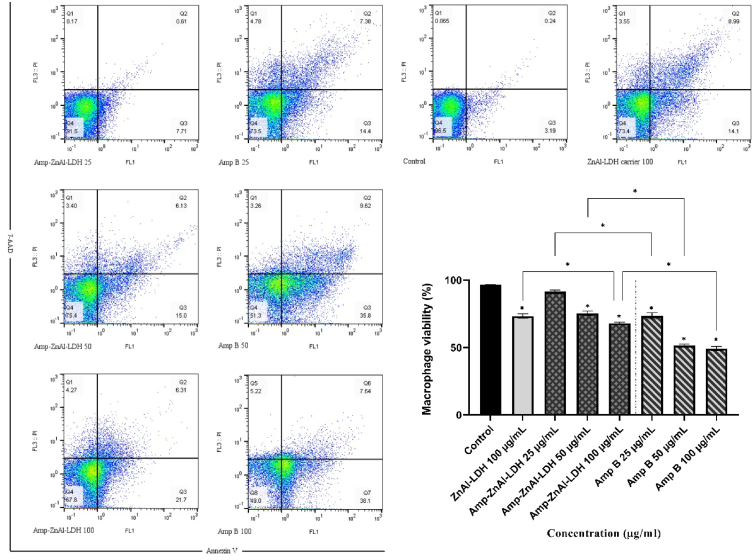

5.5. Cytotoxic effect on macrophages

As shown in Fig. 7, the cytotoxic effect of amphotericin B (Amp B) and ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) was mediated in a dose-dependent response; by increasing the concentrations of samples from 25 μg/mL to 100 μg/mL, the viability percentages of macrophage cell line reduced. These results showed that there are significant differences between samples and negative control (P < 0.001) except the lowest concentration of Amp-ZnAl-LDH (25 μg/mL), which was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). In addition, highest concentration (100 μg/mL) of ZnAl-LDH alone as a nanocarrier of amphotericin B presented significantly higher rate of viability of murine macrophages compared to Amp-ZnAl-LDH and Amp B in same concentration (P < 0.001). Meanwhile, the Amp-ZnAl-LDH had less cytotoxicity effects in comparison to amphotericin B in similar concentrations (P < 0.001). According to the results, the CC50 value of Amp-ZnAl-LDH (156.84 ± 2.85 μg/mL) was significantly higher than amphotericin B (87.27 ± 1.78 μg/mL) for macrophages (P < 0.01). In related with previous findings [[48], [49], [50]], it was found that intercalation of amphotericin B into the LDH carrier leads to a reduction in its cytotoxic effects on murine macrophages as compared with conventional form of the drug.

Fig. 7.

The viability profiles of the murine macrophages exposed to various concentrations of amphotericin B (Amp B) and ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) in comparison to untreated control and LDH carrier at the concentration of 100 μg/mL after 72 h incubation. Bars demonstrate the mean ± standard deviation of viability rates (*P < 0.001).

In order to evaluate the toxicity and safety index of ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) and amphotericin B (Amp B), the selectivity index (SI) was measured as an indicator for the treatment of macrophages. Table 8 demonstrates the SI of Amp-ZnAl-LDH and Amp B as a positive control, which is 7.45 and 3.43, respectively. According to the results, it can be concluded that Amp-ZnAl-LDH nanocomposites have higher safety index compared to Amp B; besides, the SI ≥ 1 of Amp-ZnAl-LDH nanocomposites exhibits high selectivity to the parasites of L. major [51].

Table 8.

Evaluating and comparing the selectivity index (SI) of ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) and amphotericin B (Amp B) as a positive control drug using IC50 values of samples against amastigote forms of L. major and CC50 values of the drugs on macrophage cell line.

| Drugs | Amastigote |

Promastigote |

Macrophage |

selectivity index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μg/ml) | IC50 (μg/ml) | CC50 (μg/ml) | CC50/IC50(value of amastigote forms) | |

| Amp-ZnAl-LDH | 21.05 ± 1.14 | 111.14 ± 8.28 | 156.84 ± 2.85 | 7.45 |

| Amphotericin B | 25.41 ± 0.90 | 65.36 ± 10.86 | 87.27 ± 1.78 | 3.43 |

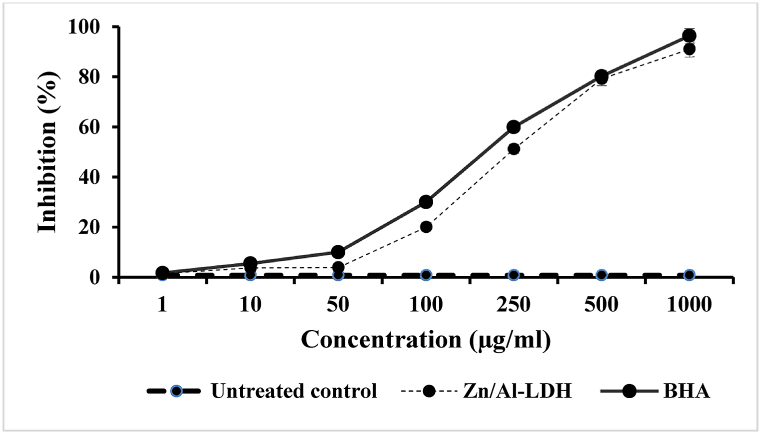

5.6. Antioxidant activity

Fig. 8 demonstrates the antioxidant activity of ZnAl-LDH nanocomposites and BHA as a positive control, measured by the DPPH method. The results of antioxidant effect of various concentrations of the samples showed high rate of radical-scavenging activity for both the ZnAl-LDH nanocarrier and BHA in a dose-response pattern. In the present study, the IC50 value of the ZnAl-LDH was calculated by statistical analysis (222.4 μg/mL) in comparison to BHA (164.9 μg/mL), which is significantly different (P < 0.001). Moreover, the prepared LDH exhibits higher activity in decreasing the stable free radical DPPH to the yellow-coloured DPPH compared to the untreated control (P < 0.001).

Fig. 8.

Scavenging activity of various concentrations of Zn/Al-LDH nanocarrier and butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) as a positive control on 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radicals in comparison with untreated control. Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments.

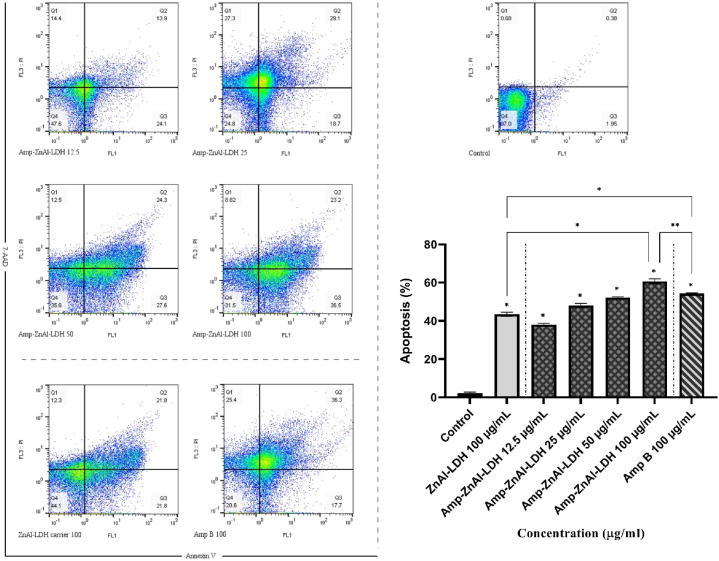

5.7. Evaluation of parasites apoptosis

As shown in Fig. 9, the percentages of apoptotic L. major promastigotes exposed to different concentrations of ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) were obtained by flow cytometry method. In addition, concentration of 100 μg/mL amphotericin B (Amp B) and ZnAl-LDH carrier alone were selected for flow cytometry assay. Results showed significant increase in percentage of apoptotic cells from 38% for 12.5 μg/mL to 59.7% for 100 μg/mL for Amp-ZnAl-LDH nanocomposites in a dose-dependent manner after 72 h treatment. According to Fig. 6, the results were assessed by the following regions; left bottom: alive parasites, right bottom: early apoptosis, left top: necrosis, right top: late apoptosis. In order to measure the level of apoptotic cells, the sum of early and late apoptosis percentages was calculated for each sample. Statistical analysis indicated significant differences between all the samples compared to control without treatment with 97% of alive parasite cells (P < 0.001). Besides, results demonstrated higher level of apoptosis for Amp-ZnAl-LDH in comparison to Amp B (P < 0.01) and ZnAl-LDH carrier alone (P < 0.001) at 100 μg/mL concentration. Due to the results, although Amp B in 100 μg/mL concentration caused less level of viable parasites compared with Amp-ZnAl-LDH, higher percentage of apoptosis was obtained for Amp-ZnAl-LDH.

Fig. 9.

Flow cytometry analysis of L. major promastigotes exposed to various concentrations of ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) and concentration of 100 μg/mL amphotericin B (Amp B) and ZnAl-LDH carrier alone in comparison with untreated control after 72 h incubation. Bars demonstrate the mean ± standard deviation of viability rates (*P < 0.001, **P < 0.01).

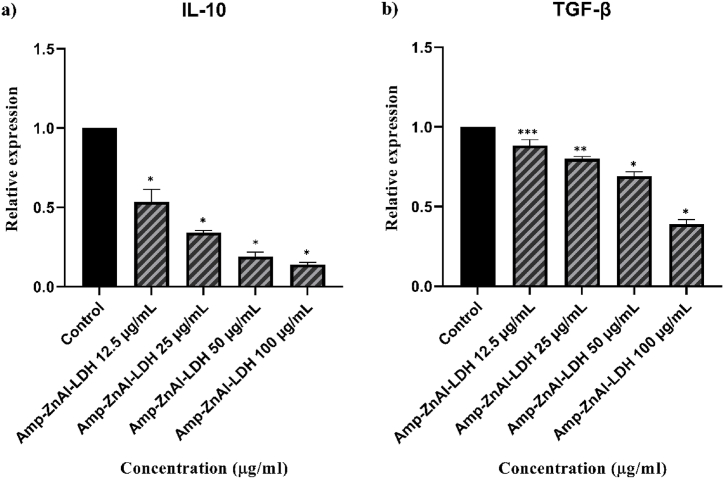

5.8. Gene expression

As shown in Fig. 10a, b, c, the expression profiles of the IL-12p40, IFN-γ, and iNOS genes, which are parameters associated with Th1 cell-mediated immune responses are all up-regulated significantly (*P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.05) except the concentration of 12.5 μg/mL. On the contrary, a significant reduction (*P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.05) was found in the expression of the IL-10 (Fig. 11a) and TGF-β (Fig. 11b) genes as a marker of Th2 cell-mediated immune responses compared to untreated control.

Fig. 10.

The gene expression levels of IL-12p40 (a), IFN-γ (b), and iNOS (c) associated with Th1 cell-mediated immune responses on L. major intra-macrophage amastigotes exposed to various concentrations of the ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) in comparison with untreated control. Bars demonstrate the mean ± standard deviation (*P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.05).

Fig. 11.

The gene expression levels of IL-10 (a) and TGF-β (b) associated with Th2 cell-mediated immune responses on L. major intra-macrophage amastigotes exposed to various concentrations of the ZnAl-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) in comparison with untreated control. Bars demonstrate the mean ± standard deviation (*P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.05).

6. Discussion

Currently, leishmaniasis is one of the most neglected tropical diseases, which consider as a public health problem due to its high rate of infection and morbidity. Besides, series of limitations such as large-scale drug resistance, treatment failures, side effects, parenteral administration, long treatment duration and pain at the injection site have been reported in recent years [[52], [53], [54], [55]]. Thus, a demand for development of safer, more innovative, efficient, cost-effective alternative therapeutic modalities is urgently increased. The nanotechnology provides application of various drug-loaded nanocarrier systems such as metallic nanoparticles, Layered double hydroxides (LDHs), nanostructured layered films and nanostructured lipid carriers. These nanocarrier systems play a crucial role for the treatment of leishmaniasis, including improving drug delivery to the target sites and bioavailability, decreasing toxicity of drugs and protecting the drug from being metabolized [[56], [57], [58], [59], [60]]. According to other studies, which were examined leishmanicidal activity of ZnO NPs, results showed high rate of anti-leishmanial activities caused by inducing apoptosis and membrane permeability in leishmania parasites [61,62]. Thus, using Zn/Al-LDH nanostructures seemed to be an interesting subject for using their both drug-loading capacity and anti-leishmanial activities.

In this study, the synthesis of Zn/Al-LDH nanocarriers was done by co-precipitation method and amphotericin B intercalated Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites were prepared using an anion exchange route. The result of UV–vis spectroscopy combined with the results of SEM analyses, confirmed that amphotericin B anions were intercalated successfully.

According to the results of in vitro and in silico assays, it can be concluded that Amp-Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites had high suppressing effects on L. major parasites. By comparing the mean IC50 values of promastigote and amastigote forms of L. major, it can be concluded that amastigotes (clinical stage) were more sensitive than promastigotes in treatment with Amp-Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites. Results indicated that conventional form of amphotericin B was more effective than Amp-Zn/Al-LDH against promastigote form of L. major parasites. However, intercalation of this drug into the interlayer space of Zn/Al-LDH provided higher anti-leishmaniasis effect against clinical stage (intra-macrophage amastigotes) of L. major parasites compared to conventional form of the drug. The results of zeta potential measurement confirm the fact that naturally positively charged structure is one of the remarkable features of inorganic LDH nanoparticles [63]. In the current study, it can be concluded that compared to amphotericin B anions, positively charged Amp-Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites were taken up more quickly by macrophages via endocytosis. Surface charge of nanoparticles is the main parameter to improve electrostatic interactions with the cell membrane and cellular uptake efficiency especially by macrophages [31,64]. In agreement with previous researches, higher uptake efficiency by macrophages were demonstrated in positively charged nanoparticles compared to negatively charged or neutral nanoparticles [45]. In addition, biodistribution studies presented higher distribution and bioavailability for positively charged nanoparticles compared to negatively charged particles [65].

Based on results, although the Zn/Al-LDH precursor had high rate of leishmanicidal activity, the combination of this nanocarrier with amphotericin B by intercalation process caused more destructive effects against L. major parasites in vitro assays. Besides, calculating selectivity index as marker of toxicity indicated that LDH as a delivery system intercalated with amphotericin B (SI = 7.45) is less harmful for mammalian macrophages in comparison to conventional form of amphotericin B (SI = 3.43). Recent studies demonstrated similar results in reducing the toxicity of corresponding pure drug that intercalated into the LDH carriers [66,67].

This study revealed appropriate antioxidant property of Zn/Al-LDH nanocarrier, which might be considered as a mechanism of action for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis [68]. In addition, related to this activity, Zn/Al-LDH nanocarriers are able to prevent oxidative stress and decrease the occurrence of cell degeneration, cancer and other diseases [69].

In the present study, Leishmania programmed cell death (PCD) was assessed due to the importance of PCD in parasite biology [70]. For this purpose, the apoptosis rate of L. major promastigotes was analyzed using flow cytometry method. Results indicated high level of apoptotic activity in both early and late apoptotic stages for Amp-Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites in a dose-dependent manner. Amp-Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites demonstrated significantly higher apoptosis level than amphotericin B alone in 100 μg/mL concentration. However, amphotericin B alone at the highest dose showed higher level of necrotic death (25.4%) compared to Amp-Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites. Therefore, by intercalation of amphotericin B into the Zn/Al-LDH nanocarriers, the percentage of necrosis was significantly decreased to (8.82%). Necrosis is a toxic process known as irreversible disruption of plasma membrane integrity in which the cell is a passive victim. In this process, the macrophages become activated and the production of proinflammatory cytokines is induced subsequently [71,72]. These results enrich the fact that using Zn/Al-LDH nanocarriers may have the ability to adjust the cell signaling and apoptotic pathways.

Present study evaluated the action mode of Zn/Al-LDH carriers along with amphotericin B (Amp-ZnAl-LDH) in stimulating anti-leishmaniasis immune responses associated with Th1 and Th2 cells. Related to Th1 cell-mediated immune responses, pro-inflammatory cytokines like IFN-γ, iNOS, and IL-12 are generated, the macrophages are induced and it finally leads to elimination of intra-macrophage amastigotes and resistance to infection. In contrast, production of IL-10 and TGF-β cytokines related to Th2 cells leads to failure in cure or non-healed infection by blocking the induction of Th1 cells and subsequently reducing the generation of IFN-γ and IL-12 [[73], [74], [75]]. In the current study, by increasing the concentration of Amp-Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites from 12.5 to 100 μg/mL, the up-regulated expression of Th1-related genes and a significant reduction in Th2-related genes were observed in comparison with untreated control on L. major intra-macrophage amastigotes. In agreement with qPCR results, the in silico findings in current study showed that amphotericin B could bind to IFN-γ to create a stable combination. IFN-γ as one the Th1-associated cytokines have the ability to activate macrophages, which leads to increase the production of NO by iNOS [76,77].

7. Conclusion

As far as the authors are aware, the current research is the first to target in vitro anti-leishmanial effects of amphotericin B as an approved drug intercalated into the interlayer space of Zn/Al–NO3 LDH nanocarrier. There are no reports on assessing the cytotoxicity of amphotericin B intercalated into the LDH nanocarriers compared to its conventional form. According to the current findings, it can be concluded that Amp-Zn/Al-LDH nanocomposites can eliminate the L. major parasites by remarkable immunomodulatory, antioxidant and apoptotic effects using in vitro and in silico assays. According to results, current study demonstrated that Zn/Al–NO3 LDH nanocarriers can be used as a new promising delivery system by intercalating amphotericin B into its interlayer space against leishmaniasis.

Author contribution statement

Sina Bahraminejad: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Abbas Pardakhty; Iraj Sharifi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Alireza Keyhani; Ehsan Salarkia: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Mehdi Ranjbar: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary content related to this article has been published online at [URL].

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to council of Pharmaceutics Research Center, Institute of Neuropharmacology, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15308.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Nafari A., et al. Nanoparticles: new agents toward treatment of leishmaniasis. Parasite epidemiology and control. 2020;10 doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2020.e00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonui W.K. Titus, and hygiene, Cross-protection against Leishmania donovani but not L. braziliensis caused by vaccination with L. major soluble promastigote exogenous antigens in BALB/c mice. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007;76(3):579–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabral F.V., et al. Nitric-oxide releasing chitosan nanoparticles towards effective treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Nitric Oxide. 2021;113:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2021.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albalawi A.E., et al. Therapeutic potential of green synthesized copper nanoparticles alone or combined with meglumine antimoniate (glucantime®) in cutaneous leishmaniasis. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(4):891. doi: 10.3390/nano11040891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabbabi A.J.A.h.s. Review of leishmaniasis in the Middle East and north Africa. Afr. Health Sci. 2019;19(1):1329–1337. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v19i1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akbari M., Oryan A., Hatam G.J.A.t. Application of nanotechnology in treatment of leishmaniasis: a review. Acta Trop. 2017;172:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aschale Y., et al. Malaria-visceral leishmaniasis co-infection and associated factors among migrant laborers in West Armachiho district, North West Ethiopia: community based cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3865-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvar J., et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pires M., et al. The impact of leishmaniasis on mental health and psychosocial well-being: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hepburn N.J.C., dermatology E.D.C. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: clinical dermatology• Review article. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2000;25(5):363–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaye P., Scott P.J.N.R.M. Leishmaniasis: complexity at the host–pathogen interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9(8):604–615. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirian S., et al. Three Leishmania/L. species–L. infantum, L. major, L. tropica–as causative agents of mucosal leishmaniasis in Iran. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2013;107(5):267–272. doi: 10.1179/2047773213Y.0000000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiwanitkit V.J.T., management c.r. Interest in paromomycin for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) Therapeut. Clin. Risk Manag. 2012;8:323. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S30139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundar S., Chatterjee M.J.I.J. Visceral leishmaniasis-current therapeutic modalities. Indian J. Med. Res. 2006;123(3):345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chakravarty J., Sundar S.J.J. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010;2(2):167. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.62887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khosravi A., et al. vol. 56. 2019. pp. 10–18. (Toxico-pathological Effects of Meglumine Antimoniate on Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahraminegad S., et al. vol. 14. 2021. (The Assessment of Apoptosis, Toxicity Effects and Anti-leishmanial Study of Chitosan/CdO Core-Shell Nanoparticles, Eco-Friendly Synthesis and Evaluation). 4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igbineweka O., et al. vol. 13. 2012. pp. 90–97. (Evaluating the Efficacy of Topical Silver Nitrate and Intramuscular Antimonial Drugs in the Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Sokoto, Nigeria). 2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahraminegad S., et al. vol. 25. 2021. (Therapeutic Effects of the As-Synthesized Polylactic Acid/chitosan Nanofibers Decorated with Amphotricin B for in Vitro Treatment of Leishmaniasis). 11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Carvalho R.F., et al. vol. 135. 2013. pp. 217–222. (Leishmanicidal Activity of Amphotericin B Encapsulated in PLGA–DMSA Nanoparticles to Treat Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in C57BL/6 Mice). 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambrogi V., et al. vol. 92. 2003. pp. 1407–1418. (Effect of Hydrotalcite-like Compounds on the Aqueous Solubility of Some Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs). 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olfs H.-W., et al. vol. 43. 2009. pp. 459–464. (Comparison of Different Synthesis Routes for Mg–Al Layered Double Hydroxides (LDH): Characterization of the Structural Phases and Anion Exchange Properties). 3-4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng Y.-M., et al. vol. 415. 2012. pp. 195–201. (Preparation of Nanostructured Microspheres of Zn–Mg–Al Layered Double Hydroxides with High Adsorption Property). [Google Scholar]

- 24.San Román M., et al. vol. 55. 2012. pp. 158–163. (Characterisation of Diclofenac, Ketoprofen or Chloramphenicol Succinate Encapsulated in Layered Double Hydroxides with the Hydrotalcite-type Structure). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seron A., Delorme F.J.J.o.P., Solids C.o. vol. 69. 2008. pp. 1088–1090. (Synthesis of Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs) with Varying pH: A Valuable Contribution to the Study of Mg/Al LDH Formation Mechanism). 5-6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S.S., et al. vol. 9. 2017. pp. 42668–42675. (Layered Double Hydroxide and Polypeptide Thermogel Nanocomposite System for Chondrogenic Differentiation of Stem Cells). 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh J.-M., et al. vol. 17. 2006. pp. 1411–1417. (Cellular Uptake Mechanism of an Inorganic Nanovehicle and its Drug Conjugates: Enhanced Efficacy Due to Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis). 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan A.I., et al. Intercalation and controlled release of pharmaceutically active compounds from a layered double hydroxideElectronic supplementary information (ESI) available: fig. S1: X-ray diffraction patterns of (a)[LiAl2 (OH) 6] Cl· H2O and (b) LDH/Ibuprofen intercalate. Chem. Commun. 2001;22:2342–2343. doi: 10.1039/b106465g. http://www.%20rsc.%20org/suppdata/cc/b1/b106465g See. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costantino U., et al. vol. 107. 2008. pp. 149–160. (Hydrotalcite-like Compounds: Versatile Layered Hosts of Molecular Anions with Biological Activity). 1-2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riaz U., Ashraf S.J.M. vol. 13. 2013. pp. 522–529. (Double Layered Hydroxides as Potential Anti-cancer Drug Delivery Agents). 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menezes J., et al. vol. 91. 2014. pp. 127–134. (Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs) as Carrier of Antimony Aimed for Improving Leishmaniasis Chemotherapy). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bi X., Zhang H., Dou L.J.P. vol. 6. 2014. pp. 298–332. (Layered Double Hydroxide-Based Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery). 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan A.I., et al. vol. 48. 2009. pp. 10196–10205. (Recent Developments in the Use of Layered Double Hydroxides as Host Materials for the Storage and Triggered Release of Functional Anions). 23. [Google Scholar]

- 34.De M., Ghosh P.S., Rotello V.M.J.A.M. vol. 20. 2008. pp. 4225–4241. (Applications of Nanoparticles in Biology). 22. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi S.-J., Choy J.-H.J.N. vol. 6. 2011. pp. 803–814. (Layered Double Hydroxide Nanoparticles as Target-specific Delivery Carriers: Uptake Mechanism and Toxicity). 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans D.G., Duan X.J.C.C. vol. 5. 2006. pp. 485–496. (Preparation of Layered Double Hydroxides and Their Applications as Additives in Polymers, as Precursors to Magnetic Materials and in Biology and Medicine). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ladewig K., Xu Z.P., Lu D.D. vol. 6. 2009. pp. 907–922. (Layered Double Hydroxide Nanoparticles in Gene and Drug Delivery). 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou K., Zhang H., Duan X.J.C. vol. 62. 2007. pp. 2022–2031. (Studies on the Formation of 5-aminosalicylate Intercalated Zn–Al Layered Double Hydroxides as a Function of Zn/Al Molar Ratios and Synthesis Routes). 7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sumbalova L., et al. vol. 46. 2018. pp. W356–W362. (HotSpot Wizard 3.0: Web Server for Automated Design of Mutations and Smart Libraries Based on Sequence Input Information). W1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian W., et al. vol. 46. 2018. pp. W363–W367. (CASTp 3.0: Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of Proteins). W1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 doi: 10.1093/nar/gky473. PMID: 29860391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amiri M., et al. vol. 849. 2020. (The Magnetic Inorganic-Organic Nanocomposite Based on ZnFe2O4-Imatinib-Liposome for Biomedical Applications, in Vivo and in Vitro Study). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asthana S., et al. vol. 57. 2013. pp. 1714–1722. (Immunoadjuvant Chemotherapy of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Hamsters Using Amphotericin B-Encapsulated Nanoemulsion Template-Based Chitosan Nanocapsules). 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Batrakova E.V., Gendelman H.E., Kabanov A.V.J.E. vol. 8. 2011. pp. 415–433. (Cell-mediated Drug Delivery). 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Danesh-Bahreini M.A., et al. vol. 6. 2011. p. 835. (Nanovaccine for Leishmaniasis: Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles Containing Leishmania Superoxide Dismutase and Evaluation of its Immunogenicity in BALB/c Mice). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen S., et al. vol. 586. 2020. (Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Molybdenum Disulfide by Compositing ZnAl–LDH). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivnay B., et al. vol. 565. 2019. pp. 447–457. (Critical Process Parameters in Manufacturing of Liposomal Formulations of Amphotericin B). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kura A.U., et al. vol. 8. 2014. pp. 1–8. (Layered Double Hydroxide Nanocomposite for Drug Delivery Systems; Bio-Distribution, Toxicity and Drug Activity Enhancement). 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi S.-J., et al. vol. 9. 2013. pp. 205–210. (Toxicity Evaluation of Inorganic Nanoparticles: Considerations and Challenges). 3. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Annan K., et al. vol. 5. 2013. p. 103. (The Heavy Metal Contents of Some Selected Medicinal Plants Sampled from Different Geographical Locations). 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neira L.F., Mantilla J.C., Escobar P.J.J. vol. 74. 2019. pp. 1634–1641. (Anti-leishmanial Activity of a Topical Miltefosine Gel in Experimental Models of New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis). 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sazgarnia A., et al. vol. 29. 2013. pp. 79–86. (Antiparasitic Effects of Gold Nanoparticles with Microwave Radiation on Promastigotes and Amastigotes of Leishmania Major). 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gamboa-Leon R., et al. 2014. Antileishmanial Activity of a Mixture of Tridax Procumbens and Allium Sativum in Mice; p. 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sen R., et al. vol. 36. 2010. pp. 43–49. (Efficacy of Artemisinin in Experimental Visceral Leishmaniasis). 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saleem K., et al. vol. 9. 2019. p. 1749. (Applications of Nanomaterials in Leishmaniasis: a Focus on Recent Advances and Challenges). 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Costa Lima S.A., et al. vol. 7. 2012. pp. 1839–1849. (Characterization and Evaluation of BNIPDaoct-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles for Visceral Leishmaniasis: in Vitro and in Vivo Studies). 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Italia J.L., Ravi Kumar M., Carter K.J.J. vol. 8. 2012. pp. 695–702. (Evaluating the Potential of Polyester Nanoparticles for Per Oral Delivery of Amphotericin B in Treating Visceral Leishmaniasis). 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bobo D., et al. vol. 33. 2016. pp. 2373–2387. (Nanoparticle-based Medicines: a Review of FDA-Approved Materials and Clinical Trials to Date). 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moen M.D., Lyseng-Williamson K.A., Scott L.J.J.D. vol. 69. 2009. pp. 361–392. (Liposomal Amphotericin B). 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tarnawski A.S., et al. vol. 94. 2000. pp. 93–98. (Antacid Talcid Activates in Gastric Mucosa Genes Encoding for EGF and its Receptor. The Molecular Basis for its Ulcer Healing Action). 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Delavari M., et al. vol. 9. 2014. p. 6. (In Vitro Study on Cytotoxic Effects of ZnO Nanoparticles on Promastigote and Amastigote Forms of Leishmania Major (MRHO/IR/75/ER)). 1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nadhman A., et al. vol. 11. 2016. p. 2451. (Annihilation of Leishmania by Daylight Responsive ZnO Nanoparticles: a Temporal Relationship of Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Lipid and Protein Oxidation). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Delgado R.R., et al. vol. 280. 2004. pp. 431–441. (Surface-charging Behavior of Zn–Cr Layered Double Hydroxide). 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jeon S., et al. vol. 8. 2018. p. 1028. (Surface Charge-dependent Cellular Uptake of Polystyrene Nanoparticles). 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Du X.-J., et al. vol. 6. 2018. pp. 642–650. (The Effect of Surface Charge on Oral Absorption of Polymeric Nanoparticles). 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sugano K., et al. vol. 9. 2010. pp. 597–614. (Coexistence of Passive and Carrier-Mediated Processes in Drug Transport). 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al Ali S.H.H., et al. vol. 7. 2012. p. 2129. (Controlled Release and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibition Properties of an Antihypertensive Drug Based on a Perindopril Erbumine-Layered Double Hydroxide Nanocomposite). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keyhani A., et al. vol. 101. 2021. (In Vitro and in Vivo Therapeutic Potentials of 6-gingerol in Combination with Amphotericin B for Treatment of Leishmania Major Infection: Powerful Synergistic and Multifunctional Effects). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharifi F., et al. vol. 12. 2018. pp. 264–269. (Cytotoxicity, Leishmanicidal, and Antioxidant Activity of Biosynthesised Zinc Sulphide Nanoparticles Using Phoenix Dactylifera). 3. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Basmaciyan L., Casanova M.J.P. vol. 26. 2019. (Cell Death in Leishmania). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ardestani S.K., et al. vol. 132. 2012. pp. 116–122. (Cell Death Features Induced in Leishmania Major by 1, 3, 4-thiadiazole Derivatives). 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brouckaert G., et al. vol. 15. 2004. pp. 1089–1100. (Phagocytosis of Necrotic Cells by Macrophages Is Phosphatidylserine Dependent and Does Not Induce Inflammatory Cytokine Production). 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jafarzadeh A., et al. vol. 71. 2019. pp. 1685–1700. (Leishmania Species‐dependent Functional Duality of Toll-like Receptor 2). 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oliaee R.T., et al. vol. 86. 2020. (The Potential Role of Nicotinamide on Leishmania Tropica: an Assessment of Inhibitory Effect, Cytokines Gene Expression and Arginase Profiling). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bamorovat M., et al. vol. 69. 2019. pp. 321–327. (Host's Immune Response in Unresponsive and Responsive Patients with Anthroponotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Treated by Meglumine Antimoniate: A Case-Control Study of Th1 and Th2 Pathways). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maspi N., et al. vol. 110. 2016. pp. 247–260. (Pro-and Anti-inflammatory Cytokines in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: a Review). 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jafarzadeh A., et al. vol. 147. 2021. (The Importance of T Cell-Derived Cytokines in Post-kala-azar Dermal Leishmaniasis). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.