Abstract

Two articles in this week’s issue focus on the use of ipilimumab and decitabine for patients with myelodysplasia (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) before and after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for high-risk disease. In the first article, Garcia et al report on the results of a phase 1 trial of the combination in 54 patients, demonstrating overall response rate of 52% in patients who are HSCT-naïve and 20% in patients post-HSCT; responses are usually short-lived. In the second article, Penter and colleagues characterize gene expression responses to therapy and conclude that decitabine acts directly to clear leukemic cells while ipilimumab acts on infiltrating lymphocytes in marrow and extramedullary sites. Responses are determined by leukemic cell burden and by the frequency and phenotype of infiltrating lymphocytes. Increasing bone marrow regulatory T cells is identified as a potential contributor to checkpoint inhibitor escape.

TO THE EDITOR:

CTLA-4 blockade has generated long-lasting remissions for subsets of cancer patients for whom traditional chemotherapies have failed. We have previously demonstrated clinical activity with ipilimumab (IPI) monotherapy at a 10 mg/kg dose in the treatment of relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) (including leukemia cutis) without excessive graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) induction.1,2 Epigenetic modifiers enhance expression of CTLA-4, CD80, and tumor antigen expression on leukemia cells and can induce cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell activation.3, 4, 5 We set out to determine if combining decitabine (DEC) with IPI could augment responses without causing unacceptable immune toxicity. Here, we report the results of a multicenter phase 1 trial with combination IPI + DEC in patients with relapsed, refractory (R/R), or secondary myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in both the post-HSCT and transplant-naïve settings (NCT02890329; CTEP 10026).

This phase 1 trial used a 3 + 3 dose-escalation design and was approved by central and local institutional review boards. All patients provided written informed consent. Eligible patients with morphologic relapse, refractory, or untreated secondary MDS/AML were stratified by prior transplant status into post-HSCT (arm A) or transplant-naïve (arm B) arms. Both arms received a lead-in priming cycle of DEC (cycle 0), and in the absence of GVHD or disease progression, patients received combination IPI + DEC in 28-day cycles for 1 year (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website). IV DEC at 20 mg/m2 was administered on days 1 through 5. The 3 IV IPI dose-escalation cohorts included 3, 5, and 10 mg/kg on day 1 of each “ipilimumab induction” cycle (cycles 1-4) and every other “ipilimumab maintenance” cycle (cycles 5-12). IPI infusion was withheld for immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and resumed only if the irAE resolved within 8 weeks. Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were assessed for 8 weeks after the first IPI dose and defined as being any of the following: treatment-related death; ≥grade 3 acute GVHD; ≥grade 3 nonhematologic toxicity; or grade 4 hematologic toxicity without recovery. Overall response rate (ORR) included complete remission (CR) and CR with incomplete count recovery for AML, and CR and marrow CR with or without hematologic improvement for MDS.6,7

From September 2017 to August 2021, a total of 54 patients enrolled, including 6 who withdrew (n = 3) or progressed (n = 3) during cycle 0. Ultimately, 48 patients received combination IPI + DEC, including 25 post-HSCT patients (23 AML and 2 MDS; all R/R) and 23 transplant-naïve patients (15 AML and 8 MDS; including 20 R/R and 3 previously untreated), and are included in the following safety and efficacy analyses (supplemental Figure 2; supplemental Tables 1-3).

The most frequent grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events, in the post-HSCT and transplant-naïve arms, respectively, were neutropenia, 32% and 48%; thrombocytopenia, 28% and 48%; and febrile neutropenia, 36% and 61% (supplemental Table 4A). The overall irAE rate was 44% (11 of 25) in the post-HSCT and 48% (11 of 23) in the transplant-naïve settings (Figure 1A; supplemental Tables 4B-C). Most irAEs occurred at an IPI dose of 10 mg/kg (7 of 11 [63%] post-HSCT patients; 9 of 11 [82%] transplant-naïve patients) and were less frequent at lower doses (n = 2 per arm at an IPI dose of 3 mg/kg; n = 2 in the post-HSCT arm at an IPI dose of 5 mg/kg). Steroid-responsive chronic GVHD developed at each tested IPI dose level in the post-HSCT arm, including 1 severe and 3 moderate cases. In the transplant-naïve arm, the most common irAEs were dermatitis (n = 6) and colitis (n = 3). A median of 3 IPI doses (range: 1-8) and 4 treatment cycles were received in both arms (range: 1-13). No DLTs were observed at IPI dose levels of 3 and 5 mg/kg. Three DLTs occurred at an IPI dose of 10 mg/kg, including 2 toxic deaths in post-HSCT patients receiving immune suppression (1 case of late-onset grade 3 acute GVHD of the colon/liver, and 1 case of pneumonitis), and 1 case of steroid-refractory immune-mediated grade 4 thrombocytopenia without bleeding in a transplant-naïve patient. In total, 31 patients were treated at the IPI dose level of 10 mg/kg, including 15 post-HSCT and 16 transplant-naïve patients. In combination with DEC, the maximum tolerated dose/recommended phase 2 dose (MTD/RP2D) of IPI was determined to be 10 mg/kg for both arms.

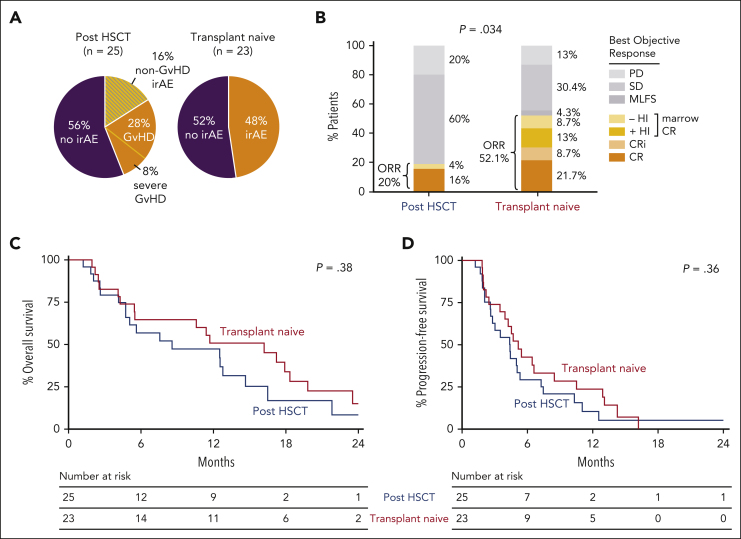

Figure 1.

Safety and efficacy of IPI plus DEC therapy in MDS/AML patients who are posttransplant or transplant-naïve. (A) Frequency of all irAEs, regardless of grade and steroid use (topical or systemic) among patients treated with IPI + DEC. IrAEs shown in orange with stripes are indicated for cases in which GVHD-specific findings were not clearly detected based on available local clinical pathologic assessment. In the post-HSCT group, 11 of 25 patients had observed irAEs, including 7 of 25 with GVHD (including 2 of 25 with severe GVHD: 1 with severe chronic and 1 with grade 3 acute). In the transplant-naïve group, 11 of 23 patients had reported irAEs. (B) Comparison of overall response rate (ORR) by treatment arm, carried out using Fisher’s exact test. Arm A (post-HSCT) responders included the following: 4 with CR and 1 with marrow CR (mCR) without hematologic improvement (HI). Arm B (transplant-naïve) responders included the following: 5 with CR, 2 with CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi), 3 with mCR with HI (mCR + HI), and 2 with mCR without HI. (C-D) Kaplan-Meier overall survival and progression-free survival curves in patients who received IPI + DEC, separated by arms: post-HSCT (arm A, blue; n = 25) and transplant-naïve (arm B, red; n = 23). MLFS, morphologic leukemia-free state; PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

Objective responses were achieved more frequently in the transplant-naïve group, which had a 52% ORR (n = 12 of 23), compared with the post-HSCT group, which had a 20% ORR (n = 5 of 25; P = .034; Figure 1B). Subsequently, 1 transplant-naïve patient was bridged to HSCT, and 2 post-HSCT patients underwent a second transplant. Although responses occurred at each IPI dose level, most occurred at 10 mg/kg (3 of 11 patients at 3 mg/kg, 2 of 6 patients at 5 mg/kg, and 12 of 31 patients at 10 mg/kg). Of the 6 cases of myeloid sarcoma without morphologic marrow involvement, 3 achieved CR. We identified 2 historical cohorts (2016-2022), including 46 patients with post-HSCT morphologic relapse and 44 with previously untreated AML, who were treated with single-agent DEC at our institution. Although no difference was detected in the post-HSCT relapse setting (P = .5), a higher response rate was observed with IPI + DEC compared to single-agent DEC in the transplant-naïve setting (P = .019).

The median follow-up for patients in the study was 9.7 months (range: 4.4-35.4) in the post-HSCT arm, and 14.3 months (range: 5.1-25.0) in the transplant-naïve arm. No statistical difference occurred in overall survival (P = .38) or progression-free survival (P = .36) between the transplant-naïve and the post-HSCT arms (Figure 1C-D). Univariate analyses did not reveal any significant association of response with history of prior GVHD, presence of a TP53 mutation, blast burden, disease histology (AML vs MDS), or prior hypomethylating agent–therapy exposure.

The median duration of response was 4.46 months (range: 1.0-40.7) and 6.14 months (range: 1.2-16.9) in patients with and without prior HSCT, respectively (supplemental Figure 3). Durable remission >1 year with concomitant irAE development occurred in 3 transplant-naïve patients treated at an IPI dose of 10 mg/kg and 1 post-HSCT patient (number 1006) treated at an IPI dose of 3 mg/kg. Patient 1006 achieved CR and developed chronic GVHD after one IPI + DEC cycle and continues to maintain a durable CR >3.5 years later. We thus asked if irAE development was associated with outcome (supplemental Figure 4). No differences were observed in median overall survival in either post-HSCT or transplant-naïve patients based on irAE occurrence (Figure 2A). However, among the transplant-naïve patients, 1-year overall survival was significantly longer in those with irAE development than in those without (72.7% vs 33.3%; P = .039), suggesting that IPI + DEC–induced immune activation was associated with survival benefit. However, to significantly lengthen progression-free survival among transplant-naïve patients, subsequent consolidation with transplant is still necessary when possible.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal evaluation of local and systemic immune responses after IPI plus DEC therapy. (A) Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves in the post-HSCT (left panel) and the transplant-naïve (right panel) arms, separated by those with irAEs requiring systemic steroids (orange) and those without any irAE (purple). Two post-HSCT patients who required only topical steroids were not included in this analysis. (B) Multiplex immunofluorescence of bone marrow biopsies obtained serially from patients before and after combination DEC + IPI therapy. Immunohistochemical staining staining density was semi-quantified by Inform software (Akoya Biosciences, Marlborough, MA). The left panel shows serial multiplex immunofluorescence images with CD3 (purple), CD8 (white), and GZMB (green) immunohistochemical staining from patient 1002 (who achieved CR). Arrows indicate clusters of CD3+ CD8+ GZMB+ cells observed after 4 cycles of IPI + DEC treatment. The right panel shows dynamic changes in CD3+ T-cell subsets among 16 available paired samples before and after IPI + DEC treatment. Statistical testing was performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for unpaired samples. (C) Serial flow cytometry-based immune phenotyping was performed using 10 paired blood samples collected at screening, after DEC lead-in, and after IPI + DEC combination therapy at the RP2D (IPI 10 mg/kg). The left panel shows a uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot with cells colored according to 8 peripheral blood mononuclear cell populations obtained from FlowSOM (Bioconductor). Generated UMAPs were stratified by each timepoint (T0, T1, and T2). Based on unsupervised cluster analysis of immune cell types and checkpoint expression, accumulations of ICOS+ CD4+ T cells were observed (dashed line). The right panel shows the proportion of ICOS-positive cells in CD4+ T cells. (D) Comparison of the proportion of CD4+ Treg cells as a subset of total CD3+ T cells was performed. Box plots indicate median, quartile 1 (Q1), and Q3, and minimum (min) and maximum (max). P values were determined with the 2-sided, paired t-test. T0, screening; T1, end of lead-in DEC; T2, end of combination IPI + DEC cycle 1; and T3, end of combination IPI + DEC cycle 2.

Despite striking examples of individual responders with increased cytotoxic T-cell infiltrate (CD3+CD8+granzyme B+) using multiplexed immunofluorescence staining on serial bone marrow biopsies and globally increased CD3+ density after IPI + DEC administration, no distinct pattern of local T-cell infiltration pre- or posttreatment was associated with response, highlighting underlying tumor and immune heterogeneity (Figure 2B; supplemental Figures 5 and 6; supplemental Tables 5 and 6). We further evaluated systemic effects of treatment on circulating T-cell subsets (supplemental Table 7; supplemental Figures 7-9). Following IPI infusion, we observed upregulation of the inducible costimulator (ICOS) molecule on CD4+ T cells (mean 13.3% vs 25.7%, P = .021) and on CD8+ T cells (mean 3.5% vs 7%, P = .011), both independent of clinical response (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 9D).

Our prior IPI monotherapy study demonstrated that responses were associated with decreased activation of regulatory T cells.1 Here, we detected a global increase in regulatory T cells following IPI + DEC treatment (mean 4.2% vs 10.8%; P = .04; Figure 2D), which has been described previously after hypomethylating-agent maintenance treatment in the HSCT setting8, 9, 10 and may have been induced as a compensatory mechanism to immune activation.

In summary, combination IPI + DEC treatment has an acceptable safety profile and has meaningful clinical activity in patients with R/R MDS/AML that does not appear to require T cell–mediated alloreactivity. IPI + DEC treatment may serve as a less-intensive bridge to transplant among potential transplant candidates. Future studies are warranted to identify rational IPI-based treatment strategies to generate prolonged responses without severe immune toxicity.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.H.A. reports receiving personal fees from Janssen, Novartis, and Merck, outside the submitted work. A.B. reports receiving personal fees from Acceleron, Agios, BMS/Celgene, CTI biopharma, Gilead, Keros Therapeutics, Novartis, Taiho, and Takeda, outside the submitted work. D.J.D. reports receiving personal fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Autolus, Agios, Blueprint, Forty-Seven, Gilead, Jazz, Kite, Novartis, Pfizer, Servier, and Takeda; and receiving institutional research funds from AbbVie, Novartis, Blueprint, and Glycomimetics. M.S.D. has received institutional research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Ascentage Pharma, BMS, Genentech, MEI Pharma, Novartis, Surface Oncology, and TG Therapeutics; and has received personal consulting income from AbbVie, Adaptive Biosciences, Aptitude Health, Ascentage Pharma, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Celgene, Curio Science, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Janssen, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Research to Practice, TG Therapeutics, and Takeda, outside the submitted work. J.S.G. reports receiving personal fees from AbbVie, Astellas, and Takeda; and receiving institutional research funds from AbbVie, Genentech, Prelude, and AstraZeneca, all outside the submitted work. V.H. reports receiving personal fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Omeros, and Alexion, outside the submitted work. B.A.J. reports receiving consulting/advisor fees from AbbVie, BMS, Genentech, Gilead, GlycoMimetics, Jazz, Pfizer, Servier, Takeda, Tolero, and Treadwell; serving on the protocol steering committee for GlycoMimetics and the data monitoring committee for Gilead; receiving travel reimbursement from AbbVie; and receiving institutional research funding from 47, AbbVie, Accelerated Medical Diagnostics, Amgen, AROG, BMS, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Forma, Genentech/Roche, Gilead, GlycoMimetics, Hanmi, Immune-Onc, Incyte, Jazz, Loxo Oncology, LP Therapeutics, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Sigma Tau, and Treadwell. P.K. received personal fees from Novartis and Takeda and served on the Novartis advisory board, outside the submitted work. M.R.L. has received personal fees from Pfizer and institutional research funding from AbbVie and Novartis, outside the submitted work. D.N. has received personal fees from Pharmacyclics, served as consultant to the American Society of Hematology Research Collaborative, and has stock ownership in Madrigal Pharmaceuticals. J.R. reports receiving institutional research funding from Equillium, Kite/Gilead, and Novartis; serves on the data safety monitoring committee for Avrobio; and has received consulting income from Akron Biotech, Clade Therapeutics, Draper Laboratories, Garuda Therapeutics, LifeVault Bio, Novartis, Rheos Medicines, Talaris Therapeutics, and TScan Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. R.J.S. serves on the Board of Directors for Kiadis, Be the Match/National Marrow Donor Program, and DSMB for Juno, Celgene, and BMS; and reports receiving personal fees from Neovii, Gilead, Rheos Therapeutics, VOR Biopharma, and Novartis. R.M.S. reports receiving grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Agios, and Novartis, grants from Arog, and personal fees from Actinium, Argenx, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Biolinerx, Celgene, Daiichi-Sankyo, Elevate, Gemoab, Janssen, Jazz, Macrogenics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Hoffman LaRoche, Stemline, Syndax, Syntrix, Syros, and Takeda, outside the submitted work. B.K.T. serves on the Speakers Bureau for BMS, outside the submitted work. C.J.W. holds equity at BioNTech, Inc, and has received institutional research funding from Pharmacyclics, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families who participated in this trial and the research coordinators, research nurses, advanced practice providers, and site staff for their support of the trial; Carol Reynolds for flow cytometry; and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) BCRP.

This study was supported by research funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants K08CA245209 and UM1CA186709 (Principal Investigator: Geoffrey Shapiro). The study was also supported by the LLS Therapy Accelerator Program, a Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Medical Oncology Grant, the Jock and Bunny Adams Education and Research Fund, and the Ted and Eileen Pasquarello Tissue Bank in Hematologic Malignancies. The Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) of the NCI and Bristol-Myers Squibb provided study drug (ipilimumab) support. Scientific and financial support for the Cancer Immune Monitoring and Analysis Centers–Cancer Immunologic Data Commons (CIMAC-CIDC) Network are provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Cooperative Agreements U24CA224331 (to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute CIMAC) and U24CA224316 (to the CIDC at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute). J.S.G. is a recipient of the Conquer Cancer Foundation Career Development Award and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Translational Research Program Award. L.P. is supported by a research fellowship from the German Research Foundation (DFG, PE 3127/1-1) and is a Scholar of the American Society of Hematology.

Authorship

Contribution: J.S.G., R.J.S., D.N., D.J.D., M.S.D., H.S., and R.M.S. conceived and designed the study; J.S.G., M.K., B.K.T., L.M.M., P.K., A.M.B., A.B., B.A.J., M.R.L., M.W., E.S.W., I.G., J.H.A., C.C., V.H., A.S., R.L., T.R., D.J.D., R.M.S., and R.J.S. acquired the data; J.S.G., D.N., Y.F., L.P., R.J.S., and R.M.S. analyzed and interpreted the data; J.S.G., Y.A., J.R., N.C., S.J.R., K.P., J.O.W., Y.F., D.N., L.P., and C.J.W. provided correlative analyses; J.S.G., L.P., and R.J.S. wrote the paper; and Y.F. and D.N. performed the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Deidentified individual participant data that underlie the reported results will be made available for approved use by the study authors. Proposals for access should be sent to the corresponding author. Complete trial cohort-level data will be published on clinicaltrials.gov at conclusion of the trial. This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02890329).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Davids MS, Kim HT, Bachireddy P, et al. Ipilimumab for patients with relapse after allogeneic transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):143–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penter L, Zhang Y, Savell A, et al. Molecular and cellular features of CTLA-4 blockade for relapsed myeloid malignancies after transplantation. Blood. 2021;137(23):3212–3217. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021010867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srivastava P, Paluch BE, Matsuzaki J, et al. Induction of cancer testis antigen expression in circulating acute myeloid leukemia blasts following hypomethylating agent monotherapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7(11):12840–12856. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang H, Bueso-Ramos C, DiNardo C, et al. Expression of PD-L1, PD-L2, PD-1 and CTLA4 in myelodysplastic syndromes is enhanced by treatment with hypomethylating agents. Leukemia. 2014;28(6):1280–1288. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang LX, Mei ZY, Zhou JH, et al. Low dose decitabine treatment induces CD80 expression in cancer cells and stimulates tumor specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood. 2006;108(2):419–425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424–447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodyear OC, Dennis M, Jilani NY, et al. Azacitidine augments expansion of regulatory T cells after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2012;119(14):3361–3369. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pusic I, Choi J, Fiala MA, et al. Maintenance therapy with decitabine after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(10):1761–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magenau JM, Qin X, Tawara I, et al. Frequency of CD4(+)CD25(hi)FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells has diagnostic and prognostic value as a biomarker for acute graft-versus-host-disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(7):907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.