Abstract

HIV remains a significant public health concern in the United States, with 34,800 new cases diagnosed in 2019; of those, 18% were among women. Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with daily tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine is effective and safe, reducing HIV transmission by up to 92% in women. Though studies demonstrate low rates of PrEP adherence among cisgender women prescribed oral PrEP, little is known about the factors that shape PrEP continuation among them. This study focuses on understanding the experiences of cisgender women who have initiated PrEP to gain insight into the factors that shape PrEP continuation. We conducted semi-structured interviews with (N = 20) women who had been prescribed oral PrEP. Interviews were guided by the social-ecological framework to identify multilevel factors affecting PrEP continuation; we specifically examined the experience of engagement and retention in the PrEP cascade. We recruited women who had been prescribed oral PrEP by a government-sponsored sexual health center or a hospital-based family planning clinic in Washington, DC. Factors facilitating PrEP continuation included a positive emotional experience associated with PrEP use, high perceived risk of HIV acquisition, and high-quality communication with health care providers. The most common reason for PrEP discontinuation was low perceived HIV risk (n = 11). Other factors influencing discontinuation were side effects, a negative emotional experience while using PrEP, and negative interactions with the health care system. This study underscores the importance of specific multi-level factors, including the provision of high-quality communication designed to resonate with women and shared decision making between women and their health care providers.

Keywords: pre-exposure prophylaxis, women, HIV, adherence, HIV Infections/prevention and control

Introduction

Cisgender women (hereafter, “women”) comprised 18% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States in 2019, with significant and long-standing racial disparities in HIV incidence.1 Oral daily pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine is highly effective and safe;2,3 however, PrEP use among women, particularly Black women, remains disparately low relative to HIV incidence.4 Among the women prescribed PrEP, there are low rates of initiation and continuation.5–8

Research to date paints a consistent picture that women are enthusiastic about PrEP and report willingness to use it,9–19 however this enthusiasm and willingness are not reflected in PrEP uptake. A few studies have investigated factors that shape actual PrEP use and continuation in the United States, rather than intention. To understand this gap in the scientific literature, we apply a social-ecological framework to understand the experiences of women in an urban, high HIV-prevalence community who had been prescribed daily oral PrEP.

Methods

Study design

We obtained IRB approval from the Medstar IRB. Between June 2020 and August 2020, investigators contacted (via telephone and/or email) women who had been prescribed PrEP at a DC government-sponsored sexual health center or a hospital-based family planning clinic. Women who were not assigned female at birth, non-English speaking, or under age 18 were excluded from the study. Our scope was limited to cisgender females given that PrEP uptake patterns among this demographic group are distinct from other demographic groups.

After informed consent, investigators conducted interviews via Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)-protected video-calling service or telephone; interviews ranged between 15 and 50 min and were audio-recorded. Participants were provided a $50 gift card for participating. Investigators collected demographic data in an online data capture system (REDCap). An HIPAA-compliant third-party organization transcribed interview audio files.

Analytic framework and interview measures

Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory describes the interactions between an individual and their environment affecting perceptions and actions.20,21 Using this framework, we created a structured interview and corresponding code book to identify and explore multi-level factors affecting PrEP continuation (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Socioecological model of multisystem factors influencing PrEP continuation. This figure demonstrates the individual-, microsystem-, and macrosystem-level factors affecting PrEP continuation. PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Data analysis

Two trained investigators completed a thematic analysis,22 including data familiarization, initial coding, defining and naming themes, and reviewing themes using Dedoose. Coders achieved 75% intercoder reliability and independently coded each transcript. Discrepancies were reviewed and resolved through discussion. The analysis focused on identifying individual, microsystem, and macrosystem factors that influence PrEP utilization and (dis)continuation.

Results

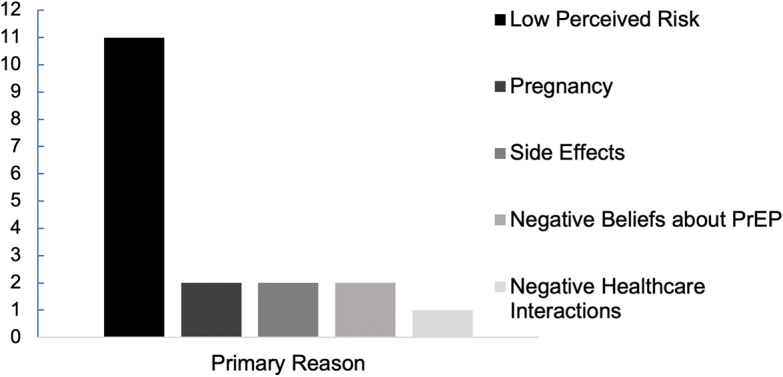

Respondents (N = 20) identified as cisgender women. The majority of participants (N = 14) identified as non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White (N = 2), non-Hispanic Asian (N = 2), and Hispanic White (N = 1). Average age was 33 years old (range, 21–52 years). Eighteen women had initiated and discontinued oral PrEP, one intended to start PrEP pending laboratory results, and one was currently using PrEP. All received PrEP at no cost (via health insurance, copay coupon cards, or Department of Health). Primary reasons for discontinuation are presented in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Primary reasons for PrEP discontinuation. The majority of participants (N = 11) reported low perceived risk of HIV transmission as the primary reason that they discontinued oral PrEP. PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Individual-level factors

Perceived HIV risk

Perceived risk of HIV was a frequent impetus for PrEP use. Several respondents noted that their PrEP use was prompted by concerns related to specific partners who were non-monogamous, living with HIV, and/or bisexual. When perceived risk was high, often in relation to partners' risk factors, participants were motivated to continue using PrEP; as circumstances and perceptions of risk changed, motivation to continue PrEP waned:

I was with someone…kind of fluid, you know, in terms of their sexuality. But I thought that we were monogamous. And then there were some things that happened that led me to believe that, that wasn't the case. And while I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do, I felt like I should do some things to protect myself.

The majority of women cited decreased perceived risk of HIV acquisition as their primary reason for discontinuation, which was often associated with the elimination of concrete potential exposures (i.e., ending relationship with partner considered high-risk). In one notable counter-example, however, a respondent discontinued PrEP because she moved to a geographic area with lower HIV prevalence.

Emotional experience

The emotional experience of using PrEP was complex and played a substantial role in participants' decisions to continue or discontinue PrEP. Many described feeling safe, protected, confident, and empowered. “[I] know that I'm safe—that gave me a lot of confidence.” “This is one of the best decisions I've ever done in my life—protecting myself… Every time I take it I feel proud of myself.” Several participants emphasized feelings of empowerment and sex-positivity. “I want to be able to control what I do with my body. And if I can't control what my sex partner do when they're not around me, I can at least control what my body has inside of me.”

Although many participants reported using condoms to prevent HIV, barrier contraception did not offer the same feelings of safety and protection provided by PrEP. Many participants described feelings of relief in having a “backup” in case of condom failure. “You are protecting yourself, in case the condom breaks. And this is just in case someone doesn't tell you the whole truth, or they miss the pills. This is protecting you in the end.”

Some participants associated PrEP with guilt and shame about sexual practices. For these individuals, oral PrEP served as a daily reminder of potential HIV exposure. Rarely participants viewed PrEP as enabling sexually promiscuous behavior:

I mean taking it though, I'm like ‘oh man,’ because you're making bad decisions. And there's some stuff that like you shouldn't be doing. Um, this is why you shouldn't be taking this, and if I stop taking this then I'm not gonna like do bad things anymore.

Some noted that taking a pill each day to prevent HIV infection was “too much” relative to eliminating the perceived risk. “The thought of taking pills every day to offset the chance of that happening honestly made me not want to have sex anymore.” Many of these respondents preferred to change their behavior to lower their HIV exposure rather than continue PrEP, including ending relationships with high-risk partners. “Because if you're in a relationship with somebody and you have to do all of that, that's too much.”

Awareness, knowledge, and beliefs

Many participants learned about PrEP from their medical providers and expressed a desire for increased awareness of PrEP in their communities, particularly among women. Specifically, several respondents reported knowing women in their lives who they thought might benefit from PrEP. Respondents also noted that misconceptions about PrEP among friends and family members create barriers to PrEP utilization, including believing that PrEP was not a prevention tool for cisgender women or that it was a medication to treat HIV. “I think it could be misunderstood because they think, ‘Oh, well the person's taking it, so they must have [HIV].’”

Participants rarely cited these misconceptions as a reason they discontinued PrEP. However, misinformation and stigma around PrEP led some participants to not disclose or to actively hide their PrEP use from family and friends. Secrecy surrounding PrEP added to the complexity and negative emotions associated with using PrEP, which appeared to influence some participants to eliminate their potential exposure to HIV to safely discontinue PrEP.

Perceived safety and efficacy and medical distrust

Some participants expressed skepticism about PrEP, with specific concerns about it being a new medication and its safety in women. The lack of public awareness of PrEP for women further undermined trust in this medication and contributed to a feeling of it being experimental or having unknown long-term side effects: “And you just kind of feel like you're a lab rat… a lab rat taking something new, and I was nervous.”

However, most participants reported positive beliefs about the safety and efficacy of PrEP. Even among those who had concerns, safety and efficacy were not primary reasons for PrEP discontinuation. However, safety concerns did contribute to some participants' reluctance to use PrEP long-term, or to only continue PrEP use if they felt their risk of HIV acquisition was imminent.

Side effects

Most commonly, side effects included gastrointestinal upset, nausea, or subjectively feeling not themselves and were a frequently noted barrier to continuation. “I couldn't eat at first - no appetite. I felt kind of depressed.” Some respondents experienced significant physical discomfort. “…I was a little bit nauseous but it [upset] my stomach and was sending me to the bathroom.” For two participants, side effects were the primary reason for discontinuation, specifically gastrointestinal upset and renal toxicity in the setting of chronic renal disease.

Acceptability of oral PrEP as a daily medication

Although none of the participants identified the inconvenience of a daily medication as their primary reason for stopping PrEP, it was a commonly cited challenge to continuation. When asked what the hardest part about PrEP was, several participants responded, “remembering to take a pill every day.” Two participants specifically expressed a desire for an injectable medication: “The one thing that I would hope that in the future there is an injectable…I just want an easier way for it to go into my system…without being nervous if I miss a day.” Of note, two participants commented on the ease of oral PrEP, that it was simple and convenient to take along with their other daily medications, for example, birth control.

Microsystem-level factors

Serodiscordant relationships

Most participants who chose to use PrEP in the context of a serodiscordant relationship described PrEP use as a positive experience. Many felt empowered by PrEP as a way to increase feelings of safety in a relationship they were committed to:

I'm gonna deal with him regardless. That he do have HIV. It wasn't a death sentence for him. It wasn't a death sentence for me. That I still cared about him and loved him. So, if I take PrEP, it was a barrier there just in case the condom break.

For others, PrEP served as a mechanism for prioritizing self-care “I did want to take the drug because I cared about him and I cared more about … I care about myself, too.”

By contrast, for other participants in a serodiscordant relationship, PrEP use magnified feelings of anxiety and stress related to HIV exposure. “So it wasn't good. So, I had to end [the relationship] because it was taking too much toll on me and stressing me out. So I had to remove myself.”

PrEP as a discrete HIV prevention option

PrEP offered a discrete prevention method for women navigating the complexities of relationships with partners who were not forthcoming about HIV status or potential HIV exposure. For example, one participant suspected that her partner was having sex with men and initiated PrEP without disclosing to her partner. PrEP allowed her to protect herself discreetly, while avoiding an unwanted confrontation with her partner about his sexuality and/or nonmonogamy. Other participants suspected that their partners had undisclosed HIV after finding antiretroviral medications and/or refusing to undergo HIV testing. These respondents decided to start PrEP with or without their partners' knowledge:

But when I told him that I wanted him to take his results, he kept on postponing that he was going to go to the doctor, but he never went there. When I went to get it [from CVS], he took the test, and it came out positive. And kept on saying, ‘Maybe we took it wrong. Maybe it's not right?’ And that's when I told my physician and he started me on [PrEP].

Health care interactions

Some participants expressed distrust of the medical system, and many commented on the importance of their interactions with individual medical providers when learning about PrEP. Several participants spoke of positive health care interactions and of providers they trusted, which contributed to their comfort taking PrEP. “I was very comfortable with starting the medication. The doctor had explained it thoroughly to me.” Several respondents noted the importance of shared decision making with their health care provider in their decision to use PrEP:

I just like how the—the counselor at the time, she was open and honest and asked me if I had any questions. She wasn't judgmental at all. She didn't like force it on me. She didn't make it seem like I was bad if I didn't wanna take it.

One respondent noted that she would have felt more comfortable hearing about PrEP from her primary care doctor as opposed to a counselor, whom she had never met before: “Maybe that, like, my physician, someone that I see on the regular, would have, you know, spoken to me about—I think it would have—I—I would have got the information the way I needed to.”

A few participants expressed that health care providers were the primary source from which they received support around PrEP, beyond initial uptake: “For me, seeing the counselor helped me stay on [PrEP], like I said, long enough to make my decision about my relationship.”

Not all respondents reported positive interactions and shared decision making with their health care providers. Some felt pressured to take PrEP or not fully informed of possible side effects:

Because I didn't mention [PrEP] to [my doctor], she mentioned it to me. And then, it's like… started feeling like it was some type of urgency for me to take it… I knew the basics of it but I didn't feel like I was thoroughly informed of, you know, the risks for taking it.

Similarly, others felt as though they were prescribed the medication without having a clear understanding of or agreement with the providers' reasons for prescribing. “But, like, um let's say like, it did hypothetically [cause long-term side effects], then I find out 25 years down the line. Like, I would like to know “Well did I really need it?” And I don't know if that like, was made clear to me.”

Macrosystem-level factors

Stigma

When probed about shame or embarrassment related to taking PrEP, the majority of participants expressed that these sentiments did not contribute to their decision to discontinue PrEP. However, when asked if there was anyone they would not want to know about their PrEP use, participants often responded with their employers, family, and friends: “Uh, God, the military, or work… I don't even tell a lot of friends.” In addition, participants articulated how HIV stigma and social norms around sex for women are inherent in PrEP stigma: “I think there's a stigma to PrEP just because of the HIV aspect… the stigma of having many sex partners, just amoral.”

Participants frequently reported HIV and PrEP stigma among friends, family, and their community. As a result, several chose to not disclose their PrEP use in their social network. This perceived need for discretion left some feeling unable to talk about PrEP or their relationships with anyone: “I don't really have support from my friends. They don't believe in it. They don't—they pretend like it's not a big deal. …I am my own support system.”

A lack of social support led to feelings of isolation and made it harder to continue on PrEP. One participant's friends had negative reactions to her simply asking if they had heard of PrEP, “they just kind of looked at me like I was crazy.” This was particularly impactful when she was struggling with side effects, “it made me feel ostracized and like I said, you know, I was having the negative side effects. It was like I didn't have anyone to talk to about it.” She went on to say, “If I had known other people that were doing it or felt like I had a little support or something, I would have felt better.”

Discussion

We applied a socio-ecological framework to understand the factors shaping women's PrEP use in a high HIV prevalence community. The results of this study contribute to a nascent body of research establishing the factors influencing uptake and continuation of PrEP for women, rather than focusing on intention to use PrEP.6,7,16,17,23 Participants described perceived risk, access to information, distrust of the medical system, and side effects as important individual-level factors that shaped PrEP continuation.

Relationship dynamics with intimate partners and within their social networks, as well as the quality of interactions with health care providers, were important micro-system factors. HIV and PrEP stigma were important macrosystem factors impacting continuation.

Perceived risk of HIV acquisition was the most commonly cited reason for continuing or discontinuing oral PrEP among participants in this and in other studies.5,6,23 This study shows that risk perceptions rooted in concrete HIV risk exposures were foundational to women's motivation to use PrEP and, for many, the withdrawal of this concrete risk exposure led to discontinuation. This has important implications for communication designed to raise awareness and improve utilization among those with indications for PrEP.

In particular, this finding points to the importance of “seasons of risk” (i.e., fluctuations in self-identified HIV risk) in the communication about PrEP for women.24 In addition, this finding suggests the importance of clear communication of guidelines regarding the time to protection after starting PrEP before a potential HIV exposure and the indicated time to continue PrEP after a potential HIV exposure in order for women to safely tailor PrEP use to their “seasons of risk.”

A recent study among Kenyan women demonstrated that episodic oral PrEP use may be less effective in preventing HIV than consistent use, as many women reported re-initiating oral PrEP several days before the potential risk exposure (compared with the recommended 20 days to reach protective levels in vaginal tissue).25 Further, this finding implicates the need for communication that distinguishes episodic PrEP use from other delivery mechanisms (i.e., on-demand PrEP, long-acting PrEP, post-exposure prophylaxis). Confusion and misinformation about PrEP cultivate distrust and impede uptake.26

Our multi-level findings are congruent with interviews among women in New York City, which identified key factors affecting continuation related to perceived risk for HIV acquisition, misinformation/lack of information about the availability of PrEP for women, positive clinical interactions, insurance coverage/costs, misinformed health care providers, side effects, and pharmacy interactions.27 Similarly, Willie et al. applied an intersectional framework for understanding the ways social-structural context and clinical contexts shape PrEP continuation.15

In-depth interviews with eight Black women highlighted the positive effects women experienced from using PrEP for self-protection and the critical importance of relationship dynamics that place responsibility for HIV prevention on women, as well as the importance of cost, medical (dis)trust, and side effects as critical factors in Black women's PrEP continuation.15

Awareness and access to accurate information about PrEP was crucial to women's utilization of PrEP. Some expressed frustration about not having heard about PrEP from their medical providers earlier; others were encouraged by the increased visibility of PrEP advertisements that were geared toward women, combatting community misperceptions that PrEP is not for women. We posit that continued misperceptions and misinformation about PrEP depress utilization and contribute to HIV and PrEP stigma, creating multi-level barriers to continuation.

Though women reported feelings of empowerment and pride regarding self-care, others experienced shame associated with PrEP use. Rectifying misinformation about PrEP may improve continuation by bolstering social support and decreasing stigma. Public communication about PrEP that resonates as sex-positive and empowerment-focused reflects the PrEP experience for many and may work toward undermining stigma.

In this study, as in others,15,27 side effects were a notable barrier to PrEP continuation. The negative impact of side effects underscores the importance of health care provider communication and education on anticipated side effects, their limited duration, and mitigation options to prepare patients, set expectations, and plan strategies to mitigate their duration/severity. Key informant interviews with seven women in Chicago also found that side effects are a major barrier to PrEP continuation and cite the importance of PrEP marketing that speaks to Black women to increase awareness of PrEP for women.28

Concerns about negative side effects and mistreatment are particularly relevant in communities such as this one. As the majority of our participants identified as Black, this distrust is grounded in well-documented contemporary and historical medical mistreatment.29 Concerns may be compounded by apprehension about the safety of newer formulations (i.e., long-acting) and modes of delivery (i.e., injectable), as they become available. Although innovations in PrEP delivery may facilitate use, mitigate side effects, and circumvent the negative emotional experience of taking a daily pill, they may also be interpreted as relatively untested or experimental.

Future research is needed to explore the experience of women using long-acting injectable methods, which will inform counseling about options for PrEP. These findings underscore the importance of systematic dissemination of accurate, timely, relevant, and resonant information about PrEP and advances in PrEP to women.

As in previous research, partners were often the impetus to utilize PrEP as partners were often viewed as introducing HIV exposure, related to known or suspected HIV infection, or nonmonogamy.24,30,31 For many women in this study, PrEP was a source of self-protection and peace of mind so that they could more fully enjoy the relationship without concerns of HIV infection. Efforts to increase PrEP use among women must consider the wide range of situations that drive a need for self-protection, particularly in ostensibly monogamous relationships, to develop strategies that are responsive to women's needs and offer discretion when needed.

Health care providers are gatekeepers to PrEP utilization for women and are often the first and important source of information about PrEP.32 High-quality interactions (e.g., open communication, lack of judgment, shared decision making) with health care providers were crucial to women's uptake and adherence to PrEP; and, as in previous research, misinformation and lack of support for PrEP among providers were significant barriers to continuation.27

Several respondents in this study described the importance of providers as sources of support regarding PrEP continuation. Conversely, ineffective communication and a lack of shared decision making between providers and patients was a significant barrier to utilization. This evidence underscores the critical importance of PrEP education for providers, and tools to facilitate high-quality, equitable communication and shared decision making around PrEP.

Feelings of empowerment, self-efficacy, self-protection, and sex positivity contributed to participants continuing PrEP whereas feelings of guilt, shame, and preference to end high-risk behaviors contributed to discontinuation. For many participants, feelings of shame, embarrassment, and stigma were grounded in cultural norms relating to sex behaviors and HIV- and PrEP-related stigma. Respondents described how stigma undermines their abilities to rely on social support systems, which are important facilitators to continued utilization of PrEP.15

On a macro level, stigma leads to silence in medical settings,33 in media, in communities, and in workplaces.34 Public communication efforts designed to raise awareness of PrEP as an empowering prevention option for women may directly and indirectly undermine stigma and shame associated with PrEP utilization and increase awareness and engagement in the PrEP cascade.

Cost was not noted as a significant barrier to PrEP continuation in this study. However, this research was conducted in Washington, DC, where financial barriers to PrEP are relatively low.35,36 Insurance coverage is high in DC (94%),37 and PrEP is covered by private insurance and Medicaid. PrEP is also available at no cost to the uninsured through both PrEP manufacturer drug assistance programs and the DC Department of Health. Evidence from locales that have not implemented Medicaid expansion demonstrate that cost can and does present significant barriers to PrEP continuation for women.15

Our sample was recruited from a single geographic region, specifically Washington, DC, one of the 48 US counties with the highest HIV incidence.38 In DC, health insurance coverage is 94%36 and the DC Department of Health (DC Health) offers the PrEP Drug Assistance Program for insured and uninsured residents.39 Through DC Health and other community clinics, uninsured and underinsured individuals can also obtain a same-day 10-day initial supply of PrEP and continued medication free of cost. Thus, the generalizability of the results of this study is to women in culturally and structurally similar locales.

In conclusion, this study contributes to an expanding body of knowledge aiming at understanding the PrEP experience among women. There are startling inequities in PrEP utilization. Understanding ways to better facilitate utilization among women who wish to use PrEP for HIV prevention is a critical step toward ending the epidemic and promoting health equity. This study underscores the importance of specific multi-level factors, including the provision of high-quality communication designed to resonate with women and shared decision making between women and their health care providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Drs. Nishita Patel, Adam Visconti, Ron Migues, Peggy Ye, Pam Lotke, and Mr. Jason Beverley and Mr. Stephen Fernandez for their support and assistance with this study.

Authors' Contributions

J.A.B.: Methodology (supporting), investigation (equal), writing—original draft preparation (lead), and writing—review and editing. S.J.H.: Conceptualization (supporting), methodology (supporting), supervision (equal), writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition. A.I.: investigation (equal), writing—original draft preparation (supporting). P.M.: writing—review and editing, project administration. R.K.S.: Conceptualization (lead), methodology (lead), supervision (equal), and writing—review and editing.

Author Disclosure Statement

R.K.S. receives grant support from Gilead Science and Viiv Healthcare; all grant funding is managed by MedStar Health Research Institute. For the remaining authors, none were declared.

Funding Information

This study received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) 1K01DA050496-02.

References

- 1. CDC. HIV and Women. Atlanta, Georgia; 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html [Last accessed: September 1, 2022].

- 2. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012;367(5):399–410; doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murnane PM, Celum C, Mugo N, et al. Efficacy of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among high-risk heterosexuals: Subgroup analyses from a randomized trial. AIDS 2013;27(13):2155–2160; doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283629037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith DK, van Handel M, Grey J. Estimates of adults with indications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by jurisdiction, transmission risk group, and race/ethnicity, United States, 2015. Ann Epidemiol 2018;28(12):850–857.e9; doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pyra M, Johnson AK, Devlin S, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use and persistence among Black Ciswomen: “Women Need to Protect Themselves, Period.” J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2022;9(3):820–829; doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amico KR, Ramirez C, Caplan MR, et al. Perspectives of US women participating in a candidate PrEP study: Adherence, acceptability and future use intentions. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22(3):e25247; doi: 10.1002/jia2.25247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hacker E, Cohn J, Golden MR, et al. HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake, initiation, and persistence in the Detroit Public Health STD Clinic. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017;4(suppl_1):S437; doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx163.1107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rolle CP, Onwubiko U, Jo J, et al. PrEP implementation and persistence in a County Health Department Setting in Atlanta, GA. AIDS Behav 2019;23(Supp 3):296–303; doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02654-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wingood GM, Dunkle K, Camp C, et al. Racial differences and correlates of potential adoption of preexposure prophylaxis: Results of a national survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1988) 2013;63(Suppl 1):S95–S101; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182920126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Minnis AM, Gandham S, Richardson BA, et al. Adherence and acceptability in MTN 001: A randomized cross-over trial of daily oral and topical tenofovir for HIV prevention in women. AIDS Behav 2013;17(2):737–747; doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0333-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goparaju L, Experton LS, Praschan NC. Women want pre-exposure prophylaxis but are advised against it by their HIV-positive counterparts. J AIDS Clin Res 2015;6(11):1–10; doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seidman DL, Weber S, Timoney MT, et al. Use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis during the preconception, antepartum and postpartum periods at Two United States Medical Centers. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215(5):632.e1–632.e7; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among us women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29(2)102–110; doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peitzmeier SM, Tomko C, Wingo E, et al. Acceptability of microbicidal vaginal rings and oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among female sex workers in a high-prevalence US city. AIDS 2017;29(11):1453–1457; doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1300628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Willie TC, Monger M, Nunn A, et al. “PrEP's just to secure you like insurance”: A qualitative study on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence and retention among black cisgender women in Mississippi. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21(1):1102; doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06786-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garfinkel DB, Alexander KA, McDonald-Mosley R, et al. Predictors of HIV-related risk perception and PrEP acceptability among young adult female family planning patients. AIDS Care 2017;29(6):751–758; doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1234679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kwakwa HA, Bessias S, Sturgis D, et al. Attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in a United States Urban Clinic Population. AIDS Behav 2016;20(7):1443–1450; doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roth AM, Aumaier BL, Felsher MA, et al. An exploration of factors impacting preexposure prophylaxis eligibility and access among syringe exchange users. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45(4):217–21; doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patel AS, Goparaju L, Sales JM, et al. Brief report: PrEP eligibility among at-risk women in the Southern United States: Associated factors, awareness, and acceptability. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019;80(5):527–532; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological Models of Human Development. In: International Encyclopedia of Education, Vol. 3 (2nd Ed.) Readings on the Development of Children (2nd Ed.). Elsevier: Oxford; 1994; pp. 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Harvard University Press: Cambridge; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braun V, Clarke V.Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77–101; doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blumenthal J, Jain S, He F, et al. Results from a pre-exposure prophylaxis demonstration project for at-risk cisgender women in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73(7):1149–1156; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Willie TC, Keene DE, Kershaw TS, et al. “You Never Know What Could Happen”: Women's perspectives of pre-exposure prophylaxis in the context of recent intimate partner violence. Women's Health Issues 2020;30(1):41–48; doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Corneli A, Perry B, Ngoje DO, et al. Episodic use of pre-exposure prophylaxis among young Cisgender Women in Siaya County, Kenya. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2022;36(10):379–388; doi: 10.1089/apc.2022.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tekeste M, Hull S, Dovidio JF, et al. Differences in medical mistrust between Black and White women: Implications for patient–provider communication about PrEP. AIDS Behav 2019;23(7):1737–1748; doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2283-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park CJ, Taylor TN, Gutierrez NR, et al. Pathways to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among women prescribed PrEP at an Urban Sexual Health Clinic. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2019;30(3):321–329; doi: 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hirschhorn LR, Brown RN, Friedman EE, et al. Black Cisgender women's PrEP knowledge, attitudes, preferences, and experience in Chicago. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020;84(5):497–507; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. Am Behav Sci 2013;57(8):10; doi: 10.1177/0002764213487340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blumenthal J, Landovitz R, Jain S, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis perspectives, sociodemographic characteristics, and HIV risk profiles of Cisgender Women seeking and initiating PrEP in a US Demonstration Project. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2021;35(12):481–487; doi: 10.1089/apc.2021.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Craddock JB, Mangum LC, Aidoo-Frimpong G, et al. The associations of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis interest and sexual risk behaviors among young Black women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2021;35(7):263–270; doi: 10.1089/apc.2020.0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hull SJ, Duan X, Brant AR, et al. Understanding psychosocial determinants of PrEP uptake among cisgender women experiencing heightened HIV risk: Implications for multi-level communication intervention. Health Commun 2022:1–12; In Press; doi: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2145781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hull SJ, Tessema H, Thuku J, et al. Providers PrEP: Identifying primary health care providers' biases as barriers to provision of equitable PrEP services. J Acquir Immune Def Syndr 2021;88(2):165–172; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hill LM, Lightfoot AF, Riggins L, et al. Awareness of and attitudes toward pre-exposure prophylaxis among African American women living in low-income neighborhoods in a Southeastern city. AIDS Care 2021;33(2):239–243; doi: 10.1080/09540121.2020.1769834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Denning P, Dinenno E. Communities in Crisis: Is There a Generalized HIV Epidemic in Impoverished Urban Areas of the United States? CDC: Atlanta, GA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36. HAHSTA. Annual Epidemiology & Surveillance Report: Data Through December 2016. Washington, DC; 2017.

- 37. Barnett JC, Vornovitsky MS. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2015. US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports; 2016: P60-257(RV). [Google Scholar]

- 38. Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy, HHS. Ending the Epidemic; 2019. Available from: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview [Last accessed: October 16, 2022].

- 39. Anonymous. PrEP for DC. 2018. Available from: www.prepfordc.com [Last accessed: March 1, 2023].