Abstract

We ask how urgent care centers (UCCs) impact healthcare costs and utilization among nearby Medicare beneficiaries. When residents of a zip code are first served by a UCC, total Medicare spending rises while mortality remains flat. In the sixth year after entry, 4.2% of the Medicare beneficiaries in a zip code that is served use a UCC, and the average per-capita annual Medicare spending in the zip code increases by $268, implying an incremental spending increase of $6,335 for each new UCC user. UCC entry is also associated with a significant increase in hospital stays and increased hospital spending accounts for half of the total increase in annual spending. These results raise the possibility that, on balance, UCCs increase costs by steering patients to hospitals.

Keywords: Urgent Care, Medicare, I11

I. Introduction

Urgent Care Centers (UCCs) are frequently viewed as a way to curb healthcare costs (Weinick et al., 2010; Allen et al., 2019; Merritt et al., 2000; Corwin et al., 2016). If patients can be diverted from costly hospital emergency rooms (ERs) and treated at lower cost in UCCs, the potential per-visit savings could be substantial. However, UCCs are increasingly owned by hospitals and health systems or corporations that contract with health systems (Kaissi et al., 2016). Some commentators have expressed concern that these UCCs are used to funnel patients into hospital systems (Landro, 2016). As one hospital executive remarked: “The benefit to patients is getting them out of the ER so they can get treated most effectively and efficiently for their non-life-threatening problems.… And on the flip side, it’s provided us with more feet through the door” (Experity, 2016).

Hence, the literature offers two starkly different hypotheses about the potential impact of UCCs on healthcare utilization and spending. The first is that UCCs substitute for more costly care in emergency rooms (ERs). If this hypothesis is true then spending should fall. The alternative hypothesis is that UCCs increase costs by increasing the amount of services consumed. This increase could occur because UCCs funnel patients to ERs and hospitals, by crowding out less expensive care in doctors’ offices, by encouraging the increased consumption of visits (because they are more convenient), or by providing additional services such as laboratory and imaging tests. We seek to determine which of these competing hypotheses is true for an important segment of the U.S. healthcare market: Beneficiaries of Medicare, the national program providing health insurance to the U.S. elderly. Moreover, regardless of effects on spending, it is possible that UCCs could have effects on health by, for example, promoting more timely or more appropriate use of care. Therefore, we will also examine the effect of newly obtained access to UCCs on mortality.

Previous studies of the impact of UCCs are based on case studies of a small number of UCCs rather than on the universe of UCCs and focus on the relatively narrow question of whether trips to UCCs substitute for trips to the emergency room (ER). This study presents the first analysis of the effects of UCC entry using a comprehensive list of UCCs.1 Medicare claims identify visits to a UCC with a specific code, which allows us to create a comprehensive list of zip codes whose inhabitants are served by a UCC. A second contribution is that we are also the first to examine the effects of UCCs on the full range of healthcare services: Because we observe all healthcare spending for Medicare recipients, we can examine not only possible substitution between ERs and UCCs, but also the overall effects of UCCs on the use of care including physician’s offices and hospitals as well as drugs, testing and other services. A third contribution is to examine effects on mortality as well as on spending.

We focus on the period 2006 to 2016, when the share of zip codes in which Medicare patients were served by a UCC grew from 28.3% to 90.7%. To estimate the impact of UCC entry, we use a difference-in-differences (DID) framework, comparing zip codes whose residents first begin being served by a UCC to zip codes in which residents are not yet being served. Because the impact of UCC entry could vary with, for example, the relative distance to UCCs and other providers, we use the estimator proposed by de Chaisemartin and d’Haultfœuille (2022), which is suitable for staggered entry with potentially heterogeneous treatment effects. And we also investigate the sensitivity of our estimates to possible violations of the parallel trends assumption using methods described by Rambachan and Roth (2022).

Our results show that when the residents of a zip code first begin to be served by a UCC, total annual Medicare spending rises while mortality remains flat. Six years after the zip code begins to be served, average annual Medicare spending per beneficiary in the area increases by $268 (2006 dollars). This increase amounts to a 4.1% increase over the baseline average annual spending (measured in 2006). Within six years, on average, 4.2% of beneficiaries in the newly served area use a UCC each year, with an average of 1.54 visits per user per year. Therefore, the implied incremental increase in total annual Medicare spending is $6,335 per UCC user and $4,133 per UCC visit. Inpatient hospital spending is the largest contributor to this increase, rising by $153 per beneficiary per year, a 4.1% increase relative to the baseline average annual inpatient spending ($3,614 per UCC user or $2,343 per UCC visit). Part D spending on prescription drugs, home health spending, and Part B drug spending rise by $108 per capita (9.07%), $43 per capita (9.37%), and $19 per capita (4.70%), respectively.2 There are also increases in the number of ER visits that result in hospital admission (3.64%).

The large increase in hospital spending and total spending reflects the fact that UCC entry is associated with a substantial increase in hospital utilization: six years after the zip code begins to be served, we estimate an incremental increase of 2.55 hospital stays per 100 served Medicare beneficiaries per year, which implies an incremental increase of 0.6 stays per year per UCC user, or 0.39 stays per UCC visit. The percentage increase in elective inpatient visits (5.57%) is larger than in non-elective visits (3.6%). By six years after, about a quarter of the increase in elective inpatient spending occurs within 90 days after a UCC visit, while about half of the increase occurs within six months of a UCC visit. In the case of non-elective visits, which are typically more urgent than elective visits, 14% of the increase occurs within two days of a UCC visit. These results speak to the continuing debate about the prevalence of induced demand in healthcare markets.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section II provides some background about UCCs and prior work. Section III provides an overview of the data, and Section IV discusses our methods. Results appear in Section V, robutness checks in Section VI, followed by a discussion and conclusions in Section VII.

II. Background

According to the American Academy of Urgent Care Medicine (2021), most UCCs employ physicians. They typically have X-ray and laboratory facilities and can treat wounds, injuries, fractures, asthma attacks and mild concussions. They do not offer surgery or inpatient care, and most do not have advanced imaging equipment (e.g., CT scans). If a patient requires more advanced care, the UCC will transfer the patient to an ER. From the patient’s point of view, the most salient features of a UCC are likely that they have longer opening hours than typical doctor’s offices, and that they welcome walk-in patients. UCC visits are slightly more expensive than physician visits but substantially cheaper than ER visits.3

While the first UCCs were owned by physicians, UCCs are increasingly owned by either hospitals and health systems or corporations that contract with health systems. According to the Urgent Care Association (2018), in 2008, 54.1% of UCCs were owned by physicians, 24.8% were owned by hospitals, and the rest were owned largely by corporations, often with private equity partners. By 2014, physician ownership had fallen to 40%, and direct hospital ownership had increased to 37%. According to the Urgent Care Association (2018), big hospital chains such as Dignity Health, HCA, Aurora Health, Intermountain Health, and Carolinas Healthcare have all made significant investments in UCCs. Yee et al. (2013) report that in some markets, the vast majority of UCCs are owned by hospitals.

These trends in ownership suggest that arrangements with hospitals are likely to have become increasingly important over time. While there is little direct evidence that ownership of UCCs matters to patient spending (and indeed, data about ownership of UCCs are not comprehensively available), related research about the ownership of physician practices suggests that patients in organizations owned by hospitals have higher spending than patients treated in similar physician-owned practices, although there is no consistent difference in quality (Ho et al., 2020). Similarly, Chernew et al. (2021) show that physicians affiliated with hospitals refer patients to hospitals for imaging tests that could easily be done in an outpatient setting.

However, much of the existing literature about UCCs argues that they should lower healthcare costs. For example, Weinick et al. (2010) examine the types of conditions that bring people to the ER and estimate that as many as 27.1% of ER visits could be treated at UCCs or retail clinics (e.g. clinics located in many drug stores), for a savings of up to $4.4 billion annually. Similarly, Allen et al. (2019) find that in areas with multiple UCCs, local non-emergent ER visits increase by 1.43% (over the adjusted mean rate of 70.58%) after UCCs close each day. This finding suggests that UCC visits can substitute for ER visits. Merritt et al. (2000) tracked patients before and after their first visit to a UCC and report that patients were less likely to use ERs subsequently. Corwin et al. (2016) examine a cross-section of Medicare beneficiary data in 2012 and find that ER use is lower in areas with high UCC use and vice versa.

Other observers have found zero or positive effects of UCC entry on ER use. Yakobi (2017) finds that although by 2015 over 100 UCCs were operating in New York City, there appeared to have been no impact on ER use. Carlson et al. (2020) examine patients who were using the ERs at two academic medical centers for low severity conditions. They find that patients who lived within one mile of an open UCC were less likely to utilize one of the ERs. Still, proximity to a UCC had no apparent effect on the use of the other ER. Using commercial insurance data and focusing only on the market for urgent care services, Wang et al. (2021) find that UCC entry is associated with small reductions in ER visits, but the combined spending on ER and UCC increases. They do not examine the effects of UCC on all types of healthcare spending or mortality as we do. In related work, Xu and Ho (2020) report that the entry of new, free-standing emergency departments had little impact on visits to hospital ERs but merely increased the overall use of emergency services. These conflicting results suggest that the impact of UCCs on healthcare costs and care utilization is still an open question. We provide new evidence by exploiting the staggered entry of UCCs in the United States using a difference-in-differences method that is robust to heterogeneous treatment effects and accounts for underlying time trends.4 Our data allow for the most extensive exploration to date of the impacts of UCCs, in terms of time, space, and the range of outcomes covered.

III. Data

Our main source of data is claims from the Medicare Fee-for-Service population (CMS, 2006–2016). We use a 20-percent sample of the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary Files (MBSF). These files include information about the patient’s utilization of care and spending, demographic characteristics, chronic conditions, dates of Medicare enrollment, date of death (if applicable), and zip code of residence.5 To identify UCC and physician visits and to measure the associated spending, we also use the 20-percent sample of the Carrier Files, which record fee-for-service claims submitted by professional providers, including physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. For analyzing inpatient spending, we use the 20-percent sample of the Inpatient Files, which contain claims submitted by hospital providers.

To define UCC entry, we take advantage of the fact that since 2003 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which oversees Medicare, has included a specific place of service code for urgent care facilities.6 Using this code, we determine the share of the Medicare beneficiaries residing in a given zip code who used a UCC in each year. If this share is at least 1%, we consider that the zip code is served by a UCC. We sometimes refer to the share rising above this 1% threshold as an “entry,” but to be clear, the UCC serving patients in a particular zip code need not necessarily be located in that same zip code.7 We later explore the robustness of our results to using different thresholds to define entry by reproducing our main results with an alternative 0.5% threshold. Note that it is necessary to use some threshold because Medicare beneficiaries might occasionally use a UCC located far from their homes, for example, if they were on vacation. The definition of entry is further detailed in Appendix A.

A patient-year is included in the sample if the patient was covered by Medicare Parts A and B (which cover inpatient and outpatient care, respectively) for the entire year or if the patient died sometime during the year. In addition, the patient must have been enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare for all 12 months and be 65 or older. We remove zip codes that had fewer than 100 fee-for-service beneficiaries in at least one year, leaving 14,562 zip codes which are observed over the entire period.

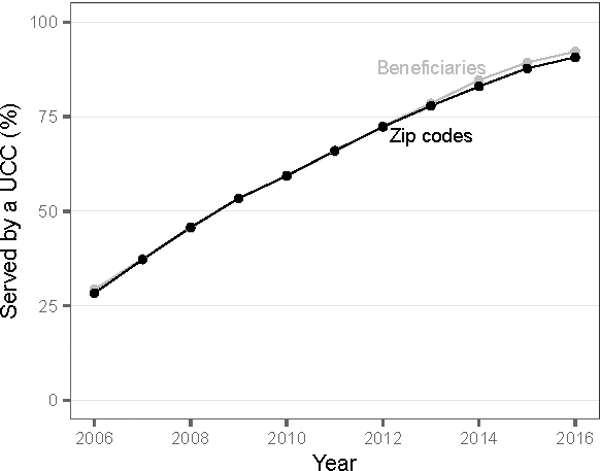

Over our sample period, there was a rapid penetration of UCCs. Between 2006 and 2016, the share of zip codes with a UCC entry grew from 28.3% to 90.7%, and the fraction of Medicare beneficiaries living in zip codes with a UCC entry increased from 29.3% to 92.2% (See Figure 1 and Appendix Table A1). The fraction of beneficiaries covered is slightly higher than the fraction of treated zip codes over our sample period, indicating that zip codes with UCC entry are slightly larger than those without. In contrast, only 5.1% of enrollees live in zip codes that experienced UCC exit (defined as a drop in the share of patients from the zip code who are treated by a UCC to below 1% for at least two years and throughout the remaining study period). Therefore, in the main analysis, we ignore exits. However, robustness analyses discussed below confirm that including exits has little impact on our estimates because they are so rare relative to entries.

Figure 1:

UCC Entry Over Time

Notes: The figure shows the percent of beneficiaries (gray) and zip codes (black) that had a UCC entry on or before each year. UCC entry is defined as the first year in which more than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in a zip code use a UCC. For detailed definitions, see Appendix A. For entry measures using alternative definitions, see Appendix Table A1 and Appendix Table A2.

Characteristics of patients, utilization of care, and spending are shown in Table 1 for areas with and without UCCs in 2011, about halfway through our sample period, and in 2016, the end of the period. Spending is in 2006 US dollars throughout. Since when a zip code becomes treated, the control sample of untreated zip codes shrinks, we display means in several different ways in Table 1 so that it is possible to compare the same set of treatment and control zip codes. For example, columns (2) and (3) deal with zip codes that were treated and untreated as of 2011, while column (4) shows outcomes in 2011 for the different and smaller set of zip codes that still remained untreated in 2016.

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics, Different Subsamples

| Subsample: | Full Sample | Treated by 2011 | Untreated by 2011 | Untreated by 2016 | Treated by 2016 | Untreated by 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Period: | 2006–2016 | 2011 Outcomes | 2011 Outcomes | 2011 Outcomes | 2016 Outcomes | 2016 Outcomes |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|

| ||||||

| A. UCC entry, Total Spending, and Mortality | ||||||

| Probability of UCC use | 0.032 | 0.041 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.063 | 0.005 |

| UCC spending (USD per capita, annual) | 4.47 | 5.89 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 8.73 | 0.58 |

| Total spending (USD per capita, annual) | 11,537 | 11,570 | 12,396 | 11,741 | 11,920 | 11,620 |

| Mortality risk | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.056 | 0.058 | 0.051 | 0.057 |

| B. Annual Spending, by Type of Service (USD per capita) | ||||||

| Inpatient | 3,491 | 3,386 | 3,732 | 3,430 | 3,307 | 3,262 |

| Hospital outpatient | 1,533 | 1,499 | 1,601 | 1,688 | 1,842 | 2,041 |

| Part D | 1,383 | 1,300 | 1,583 | 1,618 | 1,704 | 1,681 |

| SNF and hospice | 1,274 | 1,405 | 1,472 | 1,389 | 1,219 | 1,271 |

| Imaging and tests | 530 | 556 | 535 | 438 | 472 | 372 |

| Physician visits: non-UCC | 526 | 577 | 556 | 472 | 572 | 471 |

| Home health | 511 | 515 | 592 | 602 | 480 | 497 |

| Part B drug | 431 | 427 | 397 | 369 | 526 | 431 |

| C. Annual Inpatient Spending, by Category | ||||||

| (1) Acute facilities | 3,108 | 3,017 | 3,303 | 3,025 | 2,944 | 2,860 |

| (2) Non-acute facilities | 383 | 369 | 429 | 405 | 364 | 401 |

| (A) Non-elective | 2,453 | 2,438 | 2,775 | 2,404 | 2,305 | 2,272 |

| (B) Elective | 1,021 | 1,018 | 1,044 | 1,080 | 942 | 950 |

| D. Annual Inpatient Spending: Non-Elective Admissions | ||||||

| All beneficiaries | 2,453 | 2,438 | 2,775 | 2,404 | 2,305 | 2,272 |

| If no UCC visit in this or prior calendar year | 2,459 | 2,434 | 2,776 | 2,404 | 2,304 | 2,272 |

| If at least one UCC visit in this or prior calendar year | 2,356 | 2,484 | 2,549 | 2,305 | 2,313 | 2,344 |

| Spending on admissions within 1 year of UCC visit | 1,624 | 1,707 | 1,609 | 1,435 | 1,596 | 1,419 |

| Spending on admissions within 7 days of UCC visit | 283 | 310 | 251 | 241 | 259 | 215 |

| Spending on admissions within 2 days of UCC visit | 210 | 234 | 198 | 209 | 184 | 168 |

| E. Annual Inpatient Spending: Elective Admissions | ||||||

| All beneficiaries | 1,021 | 1,018 | 1,044 | 1,080 | 942 | 950 |

| If no UCC visit in this or prior calendar year | 1,016 | 1,008 | 1,043 | 1,079 | 931 | 949 |

| If at least one UCC visit in this or prior calendar year | 1,103 | 1,152 | 1,234 | 1,285 | 1,044 | 1,095 |

| Spending on admissions within 1 year of UCC visit | 711 | 750 | 735 | 714 | 681 | 668 |

| Spending on admissions within 180 days of UCC visit | 440 | 466 | 451 | 354 | 413 | 320 |

| Spending on admissions within 90 days of UCC visit | 263 | 287 | 256 | 275 | 241 | 158 |

| F. ER utilization | ||||||

| Number of ER visits | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.69 |

| ER visits without admission | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.49 |

| ER visits with admission | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| G. Controls | ||||||

| Age | 76.37 | 76.42 | 76.66 | 76.36 | 76.00 | 75.93 |

| Percent male | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| CCI approximation (lower is better) | 2.97 | 2.96 | 3.10 | 3.09 | 3.11 | 3.24 |

| Part D enrollment (number of months) | 6.26 | 5.67 | 6.28 | 6.63 | 7.88 | 7.96 |

|

| ||||||

| Observations (Beneficiary-Years) | 51,260,567 | 3,044,037 | 1,587,742 | 377,326 | 4,425,561 | 375,015 |

Notes: Column 1 shows average characteristics for all sampled patients in all years. Columns 1 and 5 focus on the subsample of beneficiaries who reside in zip codes that had a UCC entry (“treated”) by 2011 and 2016, respectively. Column 3 focuses on untreated zip codes as of 2011 (“controls”) and can be compared to column 2. Columns 4 and 6 focus on the subsample of beneficiaries living in zip codes with no UCC entry (“controls”) by 2016, measured in 2011 and 2016 respectively and can be compared to column (5). Spending is the sum of Medicare and beneficiary spending for each particular category and is denominated in 2006 US dollars. CCI stands for Charlson Comorbidity Index. For detailed definitions, see Section III and Appendix A.

The first panel of Table 1 shows that the probability of UCC use, the number of UCC visits, and UCC spending are all an order of magnitude bigger in “treated” zip codes with UCC entry compared to “control” zip codes without such entry, as one would expect given our definition of entry. Panel A also shows that total annual spending is about $300 higher in treated vs. untreated zip codes in 2016, whereas the annual mortality rate is slightly lower (5.1% in treated versus 5.7% in untreated zip codes). These differences could reflect differences in the areas where UCCs entered over time. Previous research suggests that UCCs first entered wealthier urban areas and areas with higher private insurance rates (Le and Hsia, 2016). One might well expect the effect of UCC entry to be different in the richer urban areas where UCCs initially entered compared to in areas they entered later. For example, patients in the latter might have many alternatives to UCCs. In what follows, we use methods that are robust to heterogeneous treatment effects.

Panel B of Table 1 shows the main categories of Medicare spending that we consider. One can see that the largest components of spending are (in order): inpatient hospital visits, outpatient hospital visits, Medicare Part D drug benefits, and spending on skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and hospice. For most categories, per capita 2011 spending was lower in treated areas; however, by 2016, per capita spending on inpatient visits and Part D was slightly higher in treated areas. As discussed above, one possible explanation for this crossover is that poorer areas with less healthy populations were added to the treatment group over time. These patterns underscore the need to account, as we do below, for potential differences in both morbidity and insurance coverage between areas.

Since inpatient spending is the largest category, Panels C–E of Table 1 break it down in several ways. Inpatient spending in acute care facilities (a category that includes most general-purpose hospitals) follows the pattern described above, being lower in treated areas in 2011, but higher in treated areas by 2016. Spending on non-elective visits (i.e., visits that were relatively urgent) was also lower in treatment areas in 2011 but higher in treatment areas by 2016. In both years, spending on elective visits was roughly even in treatment and control areas.

Because one concern about UCCs is that they may steer patients to hospitals, we further break down inpatient hospital spending on elective and non-elective visits by considering only patients who visited a UCC in the past year or the previous year. Panel A shows that 6.3% of patients in zip codes treated in 2016 visited a UCC during the year. In the two-year period 2015–2016, 10.2% of patients visited a UCC. In 2016, patients who visited a UCC in either the current or the previous year spent an average of $2,313 on non-elective inpatient admissions, nearly the same as the average beneficiary living in the same zip code ($2,305). Of this spending, 8% ($184) occurred within two days of a UCC visit, and 11% ($259) occurred within seven days of a UCC visit. We see a similar pattern for elective visits: Patients who visited a UCC in 2015 or 2016 had spending of $1,044 compared to an overall mean of $942. Because elective visits may be scheduled in a more leisurely way than non-elective visits, we consider a longer time window for elective visits. We show that 23% ($241) of the spending occurred within 90 days of a UCC visit, and 39.6% ($413) occurred within 180 days. Although they are only descriptive, these figures suggest that UCCs could possibly be steering patients to hospitals and that this possibility merits further investigation.

Panel F of Table 1 shows comparable figures for ER visits. An ER visit can end in an admission to the hospital or a discharge, so these two types of visits are further broken out. Zip codes with UCC entry had fewer ER visits on average than control zip codes in 2016 (0.60 versus 0.69 per beneficiary per year). This difference is concentrated in visits that did not result in an admission (0.40 vs 0.49 per beneficiary per year).

The last panel of Table 1 shows the available control variables. In addition to age and sex (which are constant over time and similar in treatment and control areas), we construct an approximation to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Charlson et al., 1987), which is frequently used to measure the burden of chronic disease in elderly people.8 The index is a severity-weighted sum of the number of chronic conditions. Table 1 shows that people are sicker in control areas than in treatment areas. The index rises over time in both treatment and control areas which is consistent with UCCs moving into areas where people are sicker: Moving the least sick patient from the control to the treatment group would increase the mean level of sickness in both groups. In models examining spending on drugs, we also control for the number of months of Part D coverage, since elderly people may move in and out of such coverage over time. See Appendix A for further discussion of the definitions of the variables included in Table 1.

IV. Methods

Our main analysis relies on a series of DID event-study analyses, examining the impact of UCC entry on a range of outcomes in treated relative to yet-to-be-treated and never treated zip codes. Several authors have shown that when treatment is staggered, standard DID estimates can be biased in the presence of heterogeneous treatment effects (Goodman-Bacon, 2021; de Chaisemartin and d’Haultfœuille, 2020, 2022). For example, as discussed above, UCCs tended to enter more urban markets first, and consumers in these markets may have had more choices than those in rural areas. Sun and Abraham (2020) show that the estimated coefficients from two-way fixed effect regressions are not robust when there are heterogeneous treatment effects, while Borusyak and Jaravel (2017) show that in this case, it is also difficult to identify pre-trends. Since it is quite likely that UCCs will have different impacts in different areas, depending, for example, on how well served they are by other types of providers, we use the estimator proposed by de Chaisemartin and d’Haultfœuille (2022) which is unbiased in the presence of heterogeneous treatment effects.

We compute dynamic treatment effects for each event-time , where denotes contemporaneous treatment effects and denotes dynamic average treatment effects. This estimator corresponds to the average effect of the treatment on the treated patients (ATT), given the staggered entry design. Note that in keeping with the huge growth of UCCs over our sample period and as discussed above, in our main results, we ignore exits and assume that once a zip code is treated, it stays treated. Specifically, we estimate:

| (1) |

where is the average outcome for beneficiaries in zip code and year is the year of UCC entry in zip code is the number of beneficiaries in zip code and year is the number of beneficiaries in zip codes treated for the first time in year and is the number of beneficiaries in zip codes that had not been treated by year . The weights capture the relative size of the group of zip codes that had UCC entry in each year for a fixed event-time relative to all treated zip codes observed for event-time .9 The term in brackets is the DID estimator comparing the outcome evolution from period (the last period before the treatment) to in groups treated for the first time in and in groups that are yet to be treated in period .

We present plots with dynamic treatment effects for the six years following a UCC entry and placebo pre-treatment effects for the six years preceding entry (with period −1 as the baseline). We compute the placebo pre-period coefficients as proposed by de Chaisemartin and d’Haultfœuille (2022) in order to be able to assess the parallel trends assumption. These coefficients are computed using the following equation:

| (2) |

To incorporate the effects of control variables, we estimate a generalization of equations (1) and (2) in which ( and ) are replaced by residuals from regressions of on (the control variables) and year fixed effects. The control variables include beneficiary age, gender, and the approximated Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI, see Section III for details). Note that the CCI measures the incidence of chronic conditions, which are an important predictor of mortality. If it were the case that UCC entry affected the CCI, then it would be an inappropriate control. On the other hand, to the extent that comorbidities are an important predictor that is largely unaffected by UCC entry, it is an appropriate and important control. We shed more light on this issue below. Estimates of the effect of UCC entry on drug spending and utilization and on total spending also control for months of Part D enrollment. The reason for controlling for Part D enrollment is that although sample participants must have been in Medicare Parts A and B for 12 months, many have fewer than 12 months of enrollment in Part D, the part of Medicare that covers prescription drugs.

The event-study graph also helps rule out mean reversion by verifying that no “Ashenfelter’s Dip” is observed pre-entry. This could be a concern if, for example, UCCs were mainly built by hospitals in areas with decreasing Medicare spending on hospital services.

In addition to the DID event-study graphs, we summarize our findings in tables that report weighted averages of the dynamic estimates for the post-treatment effects from equation (1). The weights correspond to the size of the group of zip codes that had UCC entry and are observed for event-time relative to all treated zip codes.10 Standard errors are clustered at the zip code level and are computed using 200 bootstrap replications.

In auxiliary sensitivity analyses using methods proposed by Rambachan and Roth (2022), which are discussed in Appendix B, we also evaluate the robustness of our estimates to replacing the parallel trends assumption with the weaker assumption that any differential pre-trends between the treatment and control zip codes vary smoothly over the time of UCC entry. This weaker assumption allows for the possibility that something that appears to be a break at the time of UCC entry, is actually the continuation of a pre-existing trend. Hence, these methods provide a stronger test of the hypothesis that UCC entry had a causal effect on outcomes of interest.

V. Results

Figure 2a shows the “first stage” results: The entry of a UCC in a zip code increases the use of UCCs by Medicare beneficiaries living in that zip code. This is, of course, a necessary condition for UCC entry to affect other types of utilization of medical care and spending and is implied by our definition of UCC entry. Figure 2a shows that the probability that a beneficiary uses a UCC is essentially zero prior to entry and then jumps to about 1.5% in the year of entry, rising smoothly to 4.2% by six years after entry.11 Appendix Figure A1 shows that this “first stage” is robust to using alternative measures of UCC use: the average number of UCC visits or Medicare spending on UCC services both increased similarly among Medicare beneficiaries living in a zip code upon UCC entry. By the sixth year from entry, UCC use increases to 6.5 visits per 100 beneficiaries per year. Given the size of the user population, this implies that every incremental user visits UCC about 1.5 times a year.

Figure 2:

UCC Entry, Annual Spending, and Mortality

Notes: The figure shows DID estimates of the impact of UCC entry on the probability of UCC use (the “first stage”), total annual Medicare spending, and mortality. UCC entry (Year 0) is the first year in which more than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in a zip code use a UCC. Year −1 (denoted by a vertical dashed line) is the reference level set to zero. The different panels show estimates of from equation (1) for the different outcomes. The probability of UCC use (Panel A) is the share of beneficiaries with any UCC visit during the year. Total spending (Panel B) is the total annual per capita spending on all services. Mortality risk (Panel C) is the probability that the beneficiary died anytime during the year. For detailed definitions see Section III. Standard errors are clustered by zip code.

| (3) |

The remaining panels of Figure 2 show DID estimates for the impact of UCC entry on total per capita Medicare spending and mortality. Figure 2b shows spending results. First, there is no significant pretrend in spending (in particular, no “Ashenfelter’s Dip” that could have existed if, for example, UCC entry responded to preexisting decreases in hospital spending). Post entry, annual spending per recipient began to rise, increasing by almost $300 per person by six years after entry. This amounts to a 2.4% increase over the baseline—approximately a 0.4% increase per year. Figure 2c shows no corresponding change in mortality rates—death rates are unchanged following UCC entry.

These estimates capture the average treatment effects on the entire population of served beneficiaries. The average treatment effects on UCC users are larger: considering the total annual spending and the user population size, by the sixth year, entry is associated with an incremental $6,335 increase per UCC user, or $4,113 per UCC visit.12 Since the increase in expenditure is much higher than the amount spent directly on UCCs and has no effect on mortality, it begs the question of what categories account for the additional spending?

This question is addressed in Figure 3, which shows the impact of UCC entry on the four service categories with the greatest increases in spending. Figure 3a shows that inpatient hospital spending accounts for the largest share of the increase, rising by $153 per person by six years after entry (4.12% of the 2006 baseline average). This increase in hospital spending reflects an incremental utilization increase of 2.5 visits per 100 beneficiaries per year (Appendix Table A3), which amounts to 0.60 additional inpatient hospital visits per UCC user per year, or 0.39 additional inpatient hospital visits per every UCC visit.

Figure 3:

UCC Impact on Annual Spending, Selected Services

Notes: The figure shows DID estimates of the impact of UCC entry on spending on selected services. UCC entry (Year 0) is the first year in which more than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in a zip code use a UCC. Year −1 (denoted by a vertical dashed line) is the reference level set to zero. The different panels show estimates of from equation (1) with annual per-capita spending on each of the services shown in the panel titles as the outcome. Panels A–D show results for the most affected services, in descending order. For detailed definitions see Section III. Standard errors are clustered by zip code.

Figure 3b shows that there is also an increase in Medicare Part D spending (for prescription drugs) of $108 (9.07%) after six years, suggesting that patients are receiving more prescriptions or prescriptions for more expensive drugs after a UCC opens. This observation is consistent with concerns about UCC over-prescription of drugs such as antibiotics (Laude et al., 2020; Urgent Care Association, 2019; Incze et al., 2018).

Figure 3c shows that UCC entry also led to modest increases in home health spending of approximately $43 per patient after six years. Although there does not seem to be much research on this subject, it is possible that the availability of additional options for receiving both regular doctor visits and urgent care encourages some seniors to remain in their homes and therefore to make greater use of home health services.

Finally, Figure 3d shows an increase in spending on Part B drugs of about $19 per person after six years. These are drugs that a patient would not usually give themselves (such as injectable and infused drugs that are usually given in an outpatient setting) but could be administered in a setting such as a UCC. In Appendix B we show that all of these results except for the one on Part B drug spending are robust to relaxing the parallel trends assumption and replacing them with the weaker assumption that the difference between the treatment and control zips follows a smooth time trend, using the method proposed by Rambachan and Roth (2022). For Part B drug spending the investigation in Appendix B suggests that if a differential pre-trend is allowed, we cannot reject the null of no UCC effect. However, since there is nothing in Figure 3d to suggest a rejection of the stronger parallel-trends assumption for Part B drug spending, we have retained it in this “main results” figure.

Appendix Figure A2 shows DID graphs for several other categories of services that might be impacted by UCC entry: hospital outpatient visits, imaging and tests, skilled nursing facilities and hospice, and non-UCC physician visits. For these outcomes, we observe significant pre-trends before entry, which change smoothly, if at all, around UCC entry. Therefore, it is unlikely that UCC had any impact on these services. This observation is confirmed by our analysis in Appendix B, which shows that the estimated impact of UCC on these outcomes is not robust to even modest violations of the parallel trends assumption.

Because inpatient hospital spending was the largest contributor to increases in spending following UCC entry, we examine it further in Figure 4. Figure 4a shows that virtually all of the increase in spending is occurring in regular acute care hospitals rather than non-acute care facilities. Figure 4b breaks admissions into elective and non-elective components. As discussed above, both components of inpatient spending rise following UCC entry. While the absolute size of the increase in spending on elective visits is less because elective visits account for a smaller share of spending, there is a larger percentage increase in spending on elective visits (5.62%) than in spending on non-elective visits (3.6%).

Figure 4:

UCC Impact on Annual Inpatient Spending and Emergency Room Visits

Notes: The figure shows DID estimates of the impact of UCC entry on annual spending on inpatient admissions and on the number of ER visits. UCC entry (Year 0) is the first year in which more than 1% of Medicare beneficiaries in a zip code use a UCC. Year −1 (denoted by a vertical dashed line) is the reference level set to zero. The different panels show estimates of from equation (1) for different outcomes. Panels A–D show the impact on inpatient spending, by facility and admission type, and by the time between a UCC visit and the admission. Panels E and F show the impact on ER visits ending with and without a patient being admitted to a hospital. For detailed definitions see Section III. Standard errors are clustered by zip code.

Figure 4c further breaks down the increase in spending on elective hospitalizations by asking what share of the increase in spending occurs within a relatively short window after a trip to a UCC? By six years after entry, about a quarter of the increase in elective spending occurs within 90 days after a UCC visit, while about half of the increase occurs within six months of a visit. We chose these cutoffs to allow time for a patient to book an elective visit. Figure 4d performs a similar exercise for non-elective visits. Because these visits are supposed to be more urgent, we focus on much shorter time windows of two and seven days. The figure shows that 15% of the increase in non-elective spending occurs within two days of a UCC visit, while 21% occurs within seven days of a visit.

As discussed above, UCCs are often thought of as a substitute for emergency rooms, so it is particularly interesting to see how UCC entry affects ER utilization. The remaining panels of Figure 4 show the impact of UCCs on the number of ER visits, divided by whether the person was admitted to the hospital from the ER. We look at the number of visits here because it is difficult to attribute spending to the ER when many visits result in admission and are billed together with subsequent hospital charges. Figure 4e shows that there is little change in the number of ER visits that do not end in admission when a UCC opens in a patient’s zip code, suggesting that UCCs do not divert a significant share of patients from ERs. However, the number of ER visits that end in an admission rises by 3.7% by six years after UCC entry (Figure 4f). Together with the results for inpatient visits, these estimates seem consistent with the idea of UCCs’ serving as a way to get “feet in the door” of hospitals.

The estimates underlying Figures 1–3 are summarized in Table 2. Column 1 shows the mean of the dependent variable in 2006 for all beneficiaries not yet treated in 2006. Column 2 shows a weighted average of the pre-treatment coefficients (i.e. the pre-trend values), while column 3 shows a weighted average of the post-UCC entry estimates, where the weights are as described above. Since we observe zip codes for up to six years after their first UCC entry and the effects are growing over time, column 4 shows the last point estimate, while column 5 divides that point estimate by the baseline mean to give an estimate of the percent change six years after entry.

Table 2:

The Impact of UCC Entry

| Mean Dependent Variable in 2006 | βpre | βpost | β 6 | β6/mean (percent) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|

| |||||

| A. UCC entry, Total Spending, and Mortality | |||||

| Probability of UCC use | 0.0024 | −0.0010 (0.0001) | 0.0266 (0.0004) | 0.0424 (0.0008) | – |

| Total annual spending (USD per capita) | 11,054.73 | 26.73 (19.54) | 129.08 (20.62) | 268.63 (40.10) | 2.43 |

| Mortality risk | 0.0555 | −0.0001 (0.0002) | 0.0002 (0.0002) | 0.0008 (0.0004) | 1.46 |

| B. Annual Spending, by Service Category | |||||

| Inpatient | 3,723.80 | 2.69 (12.16) | 64.49 (11.86) | 153.24 (21.38) | 4.12 |

| Part D | 1,192.61 | −8.09 (3.93) | 47.75 (4.07) | 108.20 (8.47) | 9.07 |

| Home health | 460.59 | 5.97 (3.91) | 16.07 (4.46) | 43.17 (9.64) | 9.37 |

| Part B drug | 407.77 | −1.75 (3.68) | 10.45 (3.18) | 19.17 (7.14) | 4.70 |

| C. Annual Inpatient Spending, Different Breakdowns | |||||

| (1) Inpatient in acute facilities | 3,322.77 | −3.01 (10.64) | 57.99 (10.24) | 140.26 (18.64) | 4.22 |

| (2) Inpatient in nonacute facilities | 401.04 | 5.70 (3.75) | 6.50 (3.99) | 12.97 (7.55) | 3.23 |

| (A) Inpatient: non-elective | 2,639.29 | 19.78 (10.19) | 37.61 (10.25) | 91.70 (18.34) | 3.47 |

| (B) Inpatient: elective | 1,133.93 | 9.66 (6.66) | 33.65 (6.79) | 63.13 (12.92) | 5.57 |

| D. UCC Impact on the Number of ER Visits | |||||

| ER visits without admission | 0.3192 | 0.0019 (0.0009) | −0.0010 (0.0011) | −0.0031 (0.0025) | −0.97 |

| ER visits with admission | 0.2258 | 0.0011 (0.0007) | 0.0032 (0.0007) | 0.0082 (0.0014) | 3.64 |

Notes: The table shows DID estimates of the impact of UCC entry on different outcomes. Column 1 shows the mean of the dependent variable in 2006 for all beneficiaries not yet treated in 2006. Column 2 shows a weighted average of pre-treatment estimates from equation (2), which describe the pre-trends in outcome variables. Column 3 shows a weighted average of post-treatment coefficients from equation (3). Column 4 shows estimates of β6, the estimated change in the outcome six years after UCC entry. Column 5 shows this change in outcome six years after UCC entry as a percentage of the mean dependent variable in 2006. Spending for each category is the sum of Medicare and beneficiary spending denominated in 2006 US dollars. All estimates control for beneficiary age, gender and patient approximated Charlson Comorbidity Index. Estimates of Part D spending and total spending also control for months of Part D enrollment. Standard errors are clustered by zip code. N = 36,030,854 patient-years. For detailed definitions see Section III.

Each panel of Table 2 corresponds to one of the figures, allowing us to refine the discussion above. In the case of Figure 2, Panel A of Table 2 confirms that there is a clear trend break in UCC use after UCC entry. There were no significant pre-trends in either total per capita spending or mortality, but spending increased after UCC entry. Panel B indicates that there were no pre-trends in any of the four most affected spending categories, except for Part D spending, where spending difference was slightly negative prior to UCC entry and then increased dramatically after entry. Panel C shows that there were no significant pre-trends in specific types of inpatient spending. Panel D indicates that there was no pre-trend in ER visits ending in admission to the hospital, although there was a clear increase after UCC entry. For ER visits that ended without an admission, there is a positive coefficient six years before entry that drives an overall positive “pre” coefficient, but no evidence of any effect after UCC entry.

VI. Robustness

We have conducted several additional robustness analyses which are available in an online appendix. First, we replicate the analysis using the utilization of different services instead of total spending on each service as the outcome (Appendix Table A3). The results show that the increases in hospital and home health spending previously discussed correspond to increases in utilization. Specifically, utilization of inpatient hospital stays—the main driver of the increases in spending—rises by 6.65% by six years after UCC entry.

Second, since our data consist of fee-for-service claims and do not include Medicare managed care claims, we considered the possibility that the trends we see could be impacted by fee-for-service enrollment trends and/or trends in other predetermined covariates. We find that treated zip codes saw a small decline in the share enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare, a corresponding decline in the average Charlson index of beneficiaries, a small increase in the number of months of Part D enrollment, and a small change in the gender composition of beneficiaries (Appendix Figure A3). Yet these changes occurred smoothly through UCC entry and are very small in magnitude, suggesting that they could not be driving the estimated effects of UCC entry.

Third, we show in the appendix that we obtain very similar results when we consider alternative specifications that include UCC exits (which, as discussed, are rare. See Appendix Table A4), alternative time frames for follow-up inpatient spending (Appendix Table A5), or alternative threshold for defining UCC entry to a zip code (Appendix Table A6).

VII. Discussion and Conclusions

We present the first national analysis of the effects of UCC entry on overall healthcare spending and utilization, focusing on the period 2006 to 2016, which was characterized by a rapid expansion of UCC services. We find that when Medicare patients in a zip code first begin to be served by a UCC, total Medicare spending rises, with no impact on mortality. On average, in the sixth year after entry, 4.2% of Medicare beneficiaries use a UCC at least once, and the average total annual Medicare spending in the area increases by $268, implying a $6,335 increase per UCC user. Delving into the mechanisms underlying this increase, we find that the largest rise is in inpatient hospital spending, which increases by 4.1% six years after UCC entry. Entry is also associated with a 6.5% increase in the overall number of hospital stays in the served area. This increase in inpatient spending accounts for more than half of the increase in total annual spending. The fact that the percentage increase in visits is greater than the percentage increase in spending may indicate that the marginal visits induced by UCC entry are of lower acuity. The number of ER visits that result in hospital admission increases as well. We also see increases in prescription drug spending (apparently due to the prescribing of higher-priced drugs) and home health spending. These findings highlight the possibility that the expanding web of contractual and ownership relationships between UCCs and hospitals (which we, unfortunately, cannot observe directly given the lack of ownership data) may influence their financial incentives. This issue warrants further research.

Of course, we cannot rule out the possibility that UCCs may have different impacts on the costs and utilization of younger populations, who may use them for different health conditions, may have different preferences, and whose insurers may pay different prices, even for the same services (Cooper et al., 2019). Such a population may also face higher out-of-pocket exposure when using a UCC than Medicare beneficiaries, who often have supplementary insurance. Our study also does not quantify the benefits of convenience brought by UCCs or of more frequent medical visits by patients who desire them.

We conclude that at least for the Medicare population, which accounted for 21% of U.S. healthcare spending in 2019 (Martin et al., 2021), the entrance of UCCs increases total healthcare spending, with a particularly significant effect on inpatient visits and no corresponding effect on mortality. These findings underscore the need for continued examination of the benefits and costs of the expansion of UCCs and their wider impact on the US healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging grant numbers P01AG005842 and P30AG012810. Dan Zeltzer acknowledges support from Israeli Science Foundation grant number 1461/20.

Footnotes

It has been difficult to develop a uniform definition or a comprehensive longitudinal database of UCCs. Several private organizations offer UCC accreditation, but because not all UCCs pursue accreditation, it is impossible to compile a comprehensive list of facilities from these sources. Moreover, accrediting organizations typically only have lists of current members.

Part B drugs are administered by healthcare providers but not during an inpatient visit.

FFS Medicare patients (the study sample), pay either a copay or a 20% coinsurance. However, this copay is often covered by additional supplementary insurance, which most Medicare beneficiaries hold. Physician visits cost around $25, UCC visits around $30–$40. ER visits are typically much more expensive, costing a few hundred to a few thousand dollars. For all insurance types, out-of-pocket UCC costs are typically closer in cost to an outpatient office visit than to ER visit because the latter also includes a facility fee.

Heterogeneous treatment effects may arise in this context for various reasons, including variability in access to other related services such as hospitals, physicians, and retail clinics.

CMS obtains death information from multiple administrative sources to determine the eligibility of patients and to monitor the appropriate usage of Medicare benefits. See Appendix A for more details.

“CMS Place of Service Code Set,” https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/place-of-service-codes/Place_of_Service_Code_Set, accessed January 2023.

For example, if a UCC opens in zip code A and begins serving more than 1% of residents of zip code A as well as more than 1% of residents of adjacent zip codes B and C, then we would treat zips A, B, and C as treated by the opening. We prefer this definition to using MSA or county, because these larger administrative units often encompass quite large areas and could include many residents who live far from a new UCC.

Our approximation is based on the smaller set of chronic conditions that is available in MBSF File. See Appendix A for the list of included conditions and their weights.

The weights are defined as follows:.

They are defined as follows:

Pre-entry UCC use may reflect occasional use by zip code residents of UCCs located in other areas.

These estimates are obtained by dividing the average increase of $268.63 by the incremental increase in the share of beneficiaries using a UCC (0.0424) or the incremental increase in the number of UCC visits per year (0.0653).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Janet Currie, Princeton Center for Health and Wellbeing and NBER..

Anastasia Karpova, Princeton University..

Dan Zeltzer, School of Economics, Tel Aviv University, POBox 39040, Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv, Israel 6997801; Princeton Center for Health and Wellbeing..

References

- Allen Lindsay, Cummings Janet R, and Hockenberry Jason(2019), “Urgent care centers and the demand for non-emergent emergency department visits.” NBER Working Paper No. 25428. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Urgent Care Medicine (2021), “What is urgent care medicine?” https://aaucm.org/what-is-urgent-care-medicine/, accessed January 2023.

- Borusyak Kirill and Jaravel Xavier (2017), “Revisiting event study designs.” Available at SSRN 2826228. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Lucas C, Raja Ali S, Dworkis Daniel A, Lee Jarone, Brown David FM, Samuels-Kalow Margaret, Wilson Michael, Shapiro Marc, Kim Jungyeon, and Yun Brian J (2020), “Impact of urgent care openings on emergency department visits to two academic medical centers within an integrated health care system.” Annals of Emergency Medicine, 75, 382–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson Mary E, Pompei Peter, Ales Kathy L, and MacKenzie C Ronald (1987), “A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation.” Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40, 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernew Michael, Cooper Zack, Hallock Eugene Larsen, and Morton Fiona Scott (2021), “Physician agency, consumerism, and the consumption of lower-limb mri scans.” Journal of Health Economics, 76, 102427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CMS (2006–2016), “20% Research Identifiable Medicare Databases.” Data dictionaries are available at https://resdac.org/cms-data, accessed January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Zack, Craig Stuart V, Gaynor Martin, and Van Reenen John (2019), “The price ain’t right? hospital prices and health spending on the privately insured.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134, 51–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin Gregory S, Parker Devin M, and Brown Jeremiah R (2016), “Site of treatment for non-urgent conditions by medicare beneficiaries: is there a role for urgent care centers?” The American Journal of Medicine, 129, 966–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Chaisemartin Clément and d’Haultfœuille Xavier (2020), “Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects.” American Economic Review, 110, 2964–96. [Google Scholar]

- de Chaisemartin Clément and d’Haultfœuille Xavier (2022), “Difference-in-differences estimators of intertemporal treatment effects.” NBER Working Paper No. 29873. [Google Scholar]

- Experity (2016), “It’s a win-win for healthcare as hospital systems acquire urgent care centers.” https://www.experityhealth.com/resources/hospitals-acquire-urgent-cares/, accessed January 2023.

- Goodman-Bacon Andrew (2021), “Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing.” Journal of Econometrics. 10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Vivian, Metcalfe Leanne, Vu Lan, Short Marah, and Morrow Robert (2020), “Annual spending per patient and quality in hospital-owned versus physician-owned organizations: an observational study.” Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35, 649–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incze Michael A, Redberg Rita F, and Katz Mitchell H (2018), “Overprescription in urgent care clinics—the fast and the spurious.” JAMA Internal Medicine, 178, 1269–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaissi Amer, Shay Patrick, and Roscoe Christina (2016), “Hospital systems, convenient care strategies, and healthcare reform.” Journal of Healthcare Management, 61, 148–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landro Laura (2016), “Traditional providers get into the urgent-care game.” The Wall Street Journal. March 20, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Laude Jillian D, Kramer Harold P, Lewis Marie, Winiarz Michael, Harrison Cecelia K, Zhang Zugui, and Drees Marci (2020), “Implementing antibiotic stewardship in a network of urgent care centers.” The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 46, 682–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Sidney T and Hsia Renee Y (2016), “Community characteristics associated with where urgent care centers are located: a cross-sectional analysis.” BMJ Open, 6, e010663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Anne B, Hartman Micah, Lassman David, Catlin Aaron, and National Health Expenditure Accounts Team (2021), “National health care spending in 2019: Steady growth for the fourth consecutive year.” Health Affairs, 40, 14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt Brenda, Naamon Edwin, and Morris Stephen A (2000), “The influence of an urgent care center on the frequency of ed visits in an urban hospital setting.” The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18, 123–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambachan Ashesh and Roth Jonathan (2022), “A more credible approach to parallel trends.” Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Liyang and Abraham Sarah (2020), “Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects.” Journal of Econometrics. [Google Scholar]

- Urgent Care Association (2018), “Urgent care industry white paper 2018 (unabridged): The essential role of the urgent care center in population health.” https://www.ucaoa.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=m3Bg5772Y-Q%3D&portalid=80/, accessed January 2023.

- Urgent Care Association (2019), “Industry perspectives: 2018 report - habits and perceptions of ucc antibiotic prescribing.” https://www.ucaoa.org/About-UCA/Industry-News/ArtMID/10309/ArticleID/758/hs.healthstream.com/l/152971/2020-05-08/v4msjn/, accessed January 2023.

- Wang Bill, Mehrotra Ateev, and Friedman Ari B (2021), “Urgent care centers deter some emergency department visits but, on net, increase spending: Study examines whether growth of retail urgent care centers deterred lower-acuity emergency department visits.” Health Affairs, 40, 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinick Robin M, Burns Rachel M, and Mehrotra Ateev (2010), “Many emergency department visits could be managed at urgent care centers and retail clinics.” Health Affairs, 29, 1630–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Yingying and Ho Vivian (2020), “Freestanding emergency departments in texas do not alleviate congestion in hospital-based emergency departments.” The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38, 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakobi Ramy (2017), “Impact of urgent care centers on emergency department visits.” Health Care Current Reviews, 5, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Yee Tracy, Lechner Amanda E, and Boukus Ellyn R (2013), “The surge in urgent care centers: emergency department alternative or costly convenience.” Research Brief, 26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.