Abstract

Although modern risk estimators, such as the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Pooled Cohort Equation, play a central role in the decisions of patients to start pharmacologic therapy to prevent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), there is limited evidence to inform expectations for 10-year ASCVD risk reduction from established lifestyle interventions. Using data from the original DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) trial, we determined the effects of adopting the DASH diet on 10-year ASCVD risk compared with adopting a control or a fruits and vegetables (F/V) diet. The DASH trial included 459 adults aged 22 to 75 years without CVD and not taking antihypertensive or diabetes mellitus medications, who were randomized to controlled feeding of a control diet, an F/V diet, or the DASH diet for 8 weeks. We determined 10-year ASCVD risk with the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Pooled Cohort Equation based on blood pressure and lipids measured before and after the 8-week intervention. Compared with the control diet, the DASH and F/V diets changed 10-year ASCVD risk by −10.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] −14.4 to −5.9) and −9.9% (95% CI −14.0 to −5.5) respectively; these effects were more pronounced in women and Black adults. There was no difference between the DASH and F/V diets (–0.4%, 95% CI −6.9 to 6.5). ASCVD reductions attributable to the difference in systolic blood pressure alone were −14.6% (–17.3 to −11.7) with the DASH diet and −7.9% (−10.9 to −4.8) with the F/V diet, a net relative advantage of 7.2% greater relative reduction from DASH compared with F/V. This was offset by the effects on high-density lipoprotein of the DASH diet, which increased 10-year ASCVD by 8.8% (5.5 to 12.3) compared with the more neutral effect of the F/V diet of −1.9% (−5.0 to 1.2). In conclusion, compared with a typical American diet, the DASH and F/V diets reduced 10-year ASCVD risk scores by about 10% over 8 weeks. These findings are informative for counseling patients on both choices of diet and expectations for 10-year ASCVD risk reduction.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States, claiming more than 800,000 lives annually.1 A healthy dietary pattern is a core lifestyle strategy for the primary prevention of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD).2,3 Determining the 10-year risk of ASCVD of a patient is recommended to decide on a preventive strategy and whether this strategy should include pharmacologic therapy.4−7 The DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) trial published in 1997 demonstrated the efficacy of dietary interventions to lower CVD risk factors.8 This study found that in adults with elevated blood pressure (BP) and hypertension, the DASH diet reduced systolic BP (SBP) but also decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels compared with the control diet. In contrast, a diet high in fruits and vegetables (F/V) reduced SBP to a lesser degree but improved HDL cholesterol. The impact of the DASH diet on 10-year ASCVD risk, estimated by the Pooled Cohort Equation, has not been reported. Moreover, the incremental benefit of the DASH diet compared with a simplified healthy diet emphasizing F/V is unknown. The objectives of the present study were to (1) determine the effect of the DASH diet on 10-year ASCVD risk compared with a typical American (control) diet and the F/V diet and (2) determine the contribution of dietary changes on specific risk factors toward overall 10-year ASCVD risk. We hypothesized that the risk estimation would be similar between the DASH and F/V diets based on recent reports demonstrating similar levels of cardiac injury and inflammation between the 2 diets compared with the control.9,10

Methods

Data from the DASH trial were acquired from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center. The DASH trial was a 3-arm, parallel-group, randomized controlled feeding trial comparing the effects of 3 diets on BP. Detailed research methods have been published.11 To summarize, 459 adults aged 22 to 75 years old without a CVD event within the previous 6 months and not taking antihypertensive or diabetes mellitus medications were enrolled at 4 clinical centers in the US (Baltimore, Maryland; Boston, Massachusetts; Durham, North Carolina; and Baton Rouge, Louisiana) between September 1994 and January 1996.8,12 After a 3-week run-in period with the control diet, eligible participants were randomized to 1 of 3 dietary plans (described later), and underwent an 8-week interventional feeding period.

To be eligible for the trial, participants were required to have an average SBP <160 mm Hg and an average diastolic BP (DBP) between 80 and 95 mm Hg. Participants were excluded for hyperlipidemia, a CVD event within the previous 6 months, body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2, renal insufficiency, excessive alcohol intake (>14 drinks/week), or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

The trial was initiated and sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and received institutional review board approval from all sites. The present secondary analysis was determined by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center institutional review board to be exempt research.

Participants were randomized to a control diet, an F/V diet, or the DASH diet for 8 weeks (Supplementary Table 1 for nutrition details). The study provided participants with all their food during the run-in and intervention feeding periods. The control diet was typical of what many Americans eat, with potassium, magnesium, and calcium amounts close to the 25th percentile of US consumption. The control diet was also high in total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol. An F/V diet provided more F/V than the control diet and had a higher potassium and magnesium level, close to the 75th percentile of US consumption; otherwise, the F/V diet was similar to the control diet. The DASH diet also provided more F/V than the control diet but included whole grains, poultry, fish, and nuts. DASH emphasizes fat-free or low-fat dairy products, with reduced saturated and total fat, cholesterol, sweets, and sugary beverages. The DASH diet provided magnesium, potassium, and calcium levels at the 75th percentile of US consumption. Weight was kept constant throughout all dietary assignments. BP and lipids were measured at baseline before randomization and at 8 weeks.

Staff and participants were blinded to diet assignments, and participants were blinded to all measurement data. During the screening visits, the heights and weights of participants were measured and used to calculate BMI. Obesity was defined as a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2. Participants also provided information on demographics, smoking habits, alcohol intake, and medication use. Race was self-reported by participants as White, Black or other; ethnicity was self-reported as Hispanic or non-Hispanic. Physical activity information was obtained during screening and at the end of the intervention using a questionnaire.

At study visits, 2 BPs were measured with random-zero sphygmomanometers while participants were in a seated position. Baseline BP was the average of 3 pairs of measurements during screening and 4 pairs during the run-in phase. Follow-up BPs were based on 5 pairs of measurements during the last 2 weeks of the intervention. Participants were categorized as having hypertension at baseline if prerandomization SBP was ≥140 mm Hg or DBP was ≥90 mm Hg.

Fasting blood samples were measured 12 hours apart and were drawn toward the end of the run-in period and at the end of the 8-week intervention period. The blood samples were then collected and sent for analysis to a central laboratory to quantify total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels using enzymatic colorimetry.11

The primary outcome of the present study was the absolute and relative difference in 10-year ASCVD risk scores from baseline. Estimated 10-year ASCVD risks at baseline and 8 weeks were calculated for each participant using the Pooled Cohort Equation.13 The components of the equations include age, gender, race/ethnicity, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, SBP, diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, smoking, and whether a participant was treated for hypertension. Total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and SBP were used to determine change in 10-year ASCVD risk as these were measured prerandomization and after 8 weeks of the intervention. In contrast, other components of the Pooled Cohort Equation were collected at baseline alone.

Analyses were restricted to the subpopulation with complete BP and lipid data at baseline and the 8-week follow-up visit. We computed baseline population characteristics for the included participants by diet assignment using means (SD) for continuous variables and counts with percentages for categorical or dichotomous variables.

Because of the non-normal distribution of the 10-year ASCVD risk estimates, the data were log-transformed. We used linear mixed-effects models clustered by participant with an exchangeable covariance matrix to compare the means of log-transformed ASCVD values at baseline and 8 weeks. The fixed portion of the model included diet (with values 0 for the control diet, 1 for the F/V diet, and 2 for the DASH diet), visit (with values 0 for baseline and 1 for the 8-week follow-up visit), and a diet-by-visit interaction term. The random effects portion of the model included participant identification, introducing a random intercept. We calculated both the absolute and the relative percentage difference in change from baseline by each diet intervention compared with the control. We analyzed the log-transformed ASCVD values comparing the absolute and relative percentage difference in DASH versus F/V diets.

Because the Pooled Cohort Equation is intended for adults aged between 20 and 79 years without diabetes mellitus and whose total cholesterol is between 130 and 320 mg/100 ml, HDL between 20 and 100 mg/100 ml, and SBP between 90 and 200 mm Hg, the previously mentioned calculations were repeated with 2 sensitivity analyses, involving either the exclusion or imputation of 6 participants with age, lipid, and SBPs outside of the intended range. For the imputed calculation, we substituted values for participants whose numbers fell outside this range with the indicated minimum and maximum values (n = 6). For example, anyone aged <20 years received the age of 20, whereas an age >79 years was given an age of 79.

We also evaluated the impact of dietary patterns on the individual components of the 10-year ASCVD risk scores, namely the SBP, total cholesterol, and HDL, and determined the contribution of changes in these individual components to change in 10-year ASCVD risk. For example, to examine the change in 10-year ASCVD risk score attributable to change in SBP, we calculated the change in 10-year ASCVD risk scores using the baseline and 8-week post-intervention values while maintaining total and HDL cholesterol constant at the baseline value of each participant.

In addition, we performed a prespecified stratified analysis, focused on the following CVD risk factors: age (<60 years and ≥60 years), gender (male or female), race (Black or non-Black), stage 2 hypertension status (≥140/90 mm Hg), obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m2), and smoking status (current smoker, no or yes). Interaction terms were restricted to pairs of diets (F/V vs control, DASH vs control, DASH vs F/V).

All analyses were performed using Stata software version 15.2 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas). A p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

From 459 randomized participants in the DASH trial, only the 437 participants included in our study had the complete data lipid measurements at baseline and at the 8-week follow-up needed to calculate the ASCVD risk scores (Supplementary Figure 1). There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between those with and without complete data (data not shown).

The baseline characteristics of the DASH trial participants across dietary interventions are listed in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 45 years. Roughly half were women and Black. BMI, hypertension status, SBP, DBP, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and smoking status were similar across the 3 randomized arms.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to dietary assignment, n = 437

| Control, n = 145 | Fruit and vegetable, n = 146 | DASH (combination), n = 146 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 44.7 (1.1) | 45.9 (1.1) | 44.5 (1.0) |

| Female, % | 45.1 | 43.4 | 52.0 |

| Black, % | 49.1 | 46.3 | 52.6 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 28.0 (0.4) | 27.8 (0.4) | 28.2 (0.4) |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2, % | 36.2 | 34.8 | 34.4 |

| Hypertension, % | 26.0 | 26.3 | 25.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg (SD) | 130.5 (1.1) | 131.3 (1.1) | 130.8 (1.0) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg (SD) | 84.8 (0.4) | 84.3 (0.5) | 84.1 (0.4) |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/100 ml (SD) | 120.9 (2.9) | 127.9 (2.9) | 118.7 (3.3) |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol, mmol/L (SD) | 3.1 (0.1) | 3.3 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.1) |

| Alcohol consumption, drinks/day (SD) | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) |

| Physical activity,* cal/kg/d (SD) | 37.6 (0.6) | 37.7 (0.6) | 37.7 (0.6) |

| Current smoking, % | 7.6 | 14.4 | 8.9 |

There were only 134 (control), 137 (fruit and vegetable), and 136 (DASH) with physical activity data.

The DASH diet lowered SBP, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol to a greater extent than either the F/V or control diet (Table 2). The net differences between the DASH diet and the control diet were −2.5 (95% confidence interval [CI] −4.2 to −0.8) mm Hg for SBP, −3.8 (95% CI −9.2 to 1.6) mg/dl for total cholesterol, and −0.2 (95% CI −1.7 to 1.2) mg/dl for HDL cholesterol.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular disease risk factors at baseline and at 8 weeks after intervention

| Control | F/V | DASH | F/V vs Control | DASH vs control | DASH vs F/V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | Baseline, mean (SE) | 131.3 (0.95) | 131.6 (0.95) | 131.1 (0.95) | |||

| 8-wk, mean (SE) | 129.9 (0.9) | 127.8 (0.9) | 124.4 (0.9) | ||||

| Absolute difference, mean (95% CD | −1.3 (−2.5, −0.2) | −3.8 (−5.0, −2.7) | −6.7 (−7.8, −5.5) | −2.5 (−4.2, −0.8) | −5.3 (−7.0, −3.7) | −2.8 (−4.5, −1.2) | |

| Total cholesterol, mg/100 ml | Baseline, mean (SE) | 191.4 (2.85) | 194.8 (2.84) | 187.1 (2.84) | |||

| 8-wk, mean (SE) | 195.0 (2.9) | 194.7 (2.8) | 177.6 (2.8) | ||||

| Absolute difference, mean (95% CD | 3.6 (−0.2, 7.5) | −0.2 (−4.0, 3.6) | −9.5 (−13.3, −5.7) | −3.8 (−9.2, 1.6) | −13.1 (−18.5, −7.7) | 9.3 (−14.7, 3.9) | |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/100 ml | Baseline, mean (SE) | 48.2 (1.16) | 47.9 (13.9) | 48.5 (1.15) | |||

| 8-wk, mean (SE) | 48.4 (1.2) | 47.9 (1.2) | 45.0 (1.2) | ||||

| Absolute difference, mean (95% CI) | 0.3 (−0.7, 1.3) | 0.0 (−1.0, 1.0) | −3.5 (−4.5, −2.5) | −0.2 (−1.7, 1.2) | −3.8 (−5.2, −2.4) | −3.5 (−5.0, −2.1) |

Statistically significant differences (p <0.05) are denoted in bold. Presented as mean (SE).

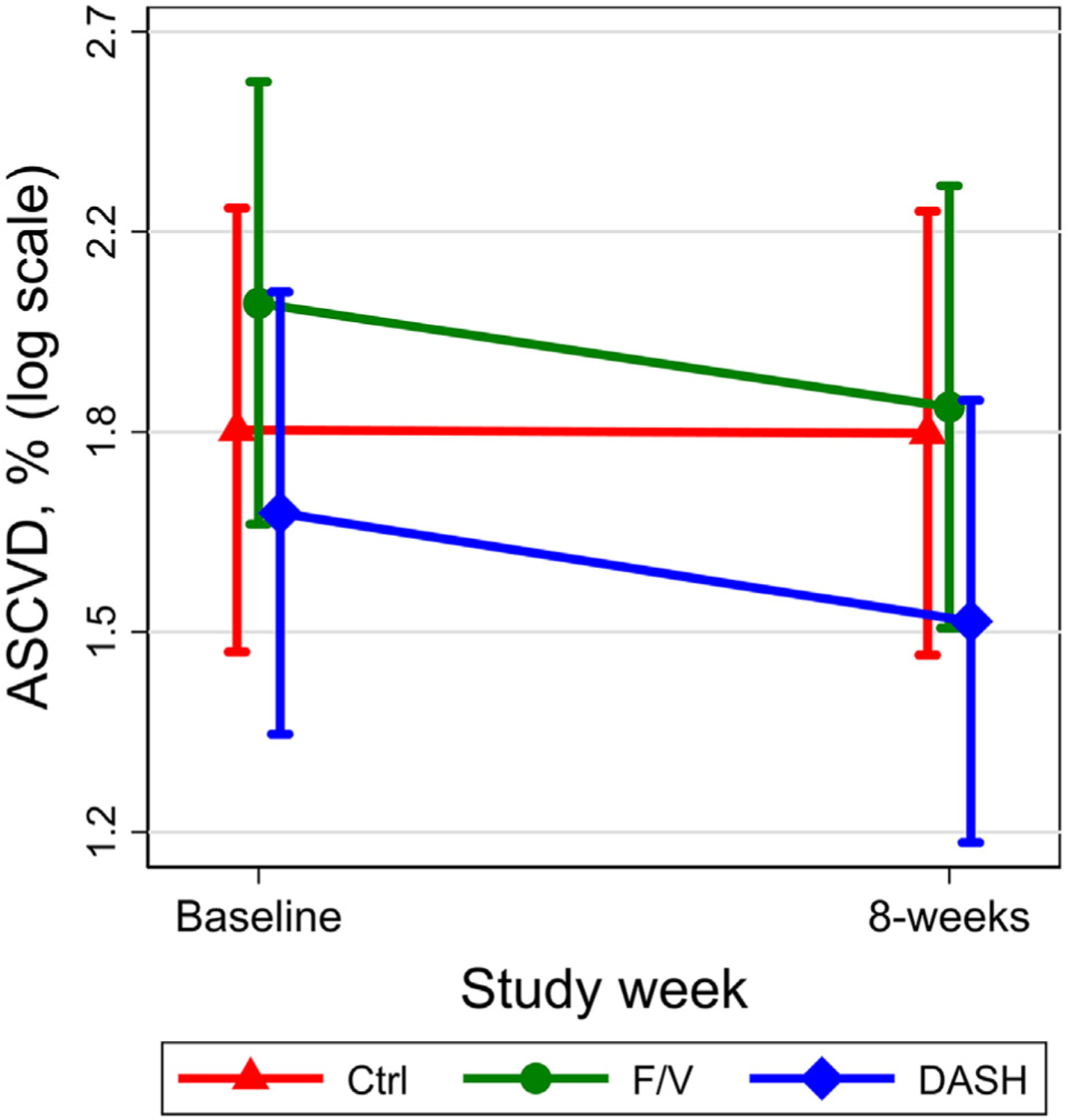

The mean 10-year ASCVD risk scores at baseline were 1.84% for the control group, 2.08% for the F/V diet group, and 1.69% for the DASH group. Risk scores at 8 weeks were lower for F/V diets and DASH but not the control diet (Figure 1, Supplement Figure 2, Table 3). Compared with the control diet, the between-group absolute difference in 10-year ASCVD risk for the F/V diet was −0.21%, representing a relative difference of −9.9%. Similarly, the DASH diet produced an absolute difference of −0.17% in ASCVD risk, representing a relative difference of −10.3%. There was no difference between the DASH and F/V diets. Sensitivity analyses excluding or imputing risk factor values outside the acceptable range for the Pooled Cohort Equation were virtually identical (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Mean (95% CI) 10-year ASCVD risk score at baseline and after 8 weeks of the Ctrl (triangle), F/V (circle), and DASH (diamond) diets. Data are presented on a log scale and generated using mixed-effects models. Ctrl = control.

Table 3.

Pooled cohort equation-predicted 10-year ASCVD risk at baseline and 8 weeks after intervention overall and according to difference in individual risk factors, n = 437

| Control | F/V | DASH | F/V vs control | DASH vs control | DASH vs F/V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incorporating all risk factor differences | ||||||

| Baseline risk %, mean* (SE) | 1.84 (0.21) | 2.08 (0.23) | 1.69 (0.19) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 8-weekrisk %, mean* (SE) | 1.83 (0.21) | 1.88 (0.21) | 1.52 (0.17) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Absolute difference in risk from baseline and between groups, % difference (95% CI) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.08) | −0.21 (−0.31, −0.10) | −0.17 (−0.26, −0.09) | −0.20 (−0.34, −0.06) | −0.17 (−0.28, −0.05) | −0.01 (−0.11,0.10) |

| Relative difference from baseline and between groups, % difference (95% CI) | −0.3 (−4.9, 4.5) | −9.9 (−14.0, −5.5) | −10.3 (−14.4, −5.9) | −9.6 (−15.5, −3.3) | −10.0 (−15.8, −3.7) | −0.4 (−6.9, 6.5) |

| Attributable difference in systolic blood pressure alone | ||||||

| Baseline mean (SE) | 1.84 (0.21) | 2.08 (0.23) | 1.69 (0.19) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 8-week mean (SE) | 1.79 (0.20) | 1.92 (0.22) | 1.44 (0.16) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Absolute difference from baseline and between groups, % (95% CI) | −0.05 (−0.11, 0.01) | −0.17 (−0.24, −0.09) | −0.25 (−0.32, −0.17) | −0.11 (−0.21, −0.01) | −0.20 (−0.29, −0.11) | −0.11 (−0.19, −0.04) |

| Relative difference from baseline and between groups, % (95% CI) | −2.7 (−5.9, 0.6) | −7.9 (−10.9, −4.8) | −14.6 (−17.3, −11.7) | −5.4 (−9.7, −0.9) | −12.2 (−16.2, −8.0) | −7.2 (−11.4, −2.7) |

| Attributable difference in total cholesterol alone | ||||||

| Baseline mean (SE) | 1.84 (0.20) | 2.08 (0.23) | 1.69 (0.19) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 8-week mean (SE) | 1.88 (0.21) | 2.08 (0.23) | 1.63 (0.18) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Absolute difference from baseline and between groups, % (95% CI) | 0.05 (−0.01, 0.10) | −0.00 (−0.07, 0.06) | −0.06 (−0.11, −0.01) | −0.06 (−0.15, 0.04) | −0.10 (−0.18, −0.02) | −0.06 (−0.13, 0.02) |

| Relative difference from baseline and between groups, % (95% CI) | 2.5 (−0.6, 5.7) | −0.2 (−3.2, 2.9) | −3.5 (−6.4, −0.5) | −2.6 (−6.7, 1.7) | −5.9 (−9.9, −1.7) | −3.3 (−7.4, 0.9) |

| Attributable differences in HDL cholesterol alone | ||||||

| Baseline mean (SD) | 1.84 (0.21) | 2.08 (0.23) | 1.69 (0.19) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 8-week mean (SD) | 1.83 (0.21) | 2.04 (0.23) | 1.84 (0.21) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Absolute difference from baseline and between groups, % (95% CI) | −0.00 (−0.06, 0.06) | −0.04 (−0.11, 0.03) | 0.15 (0.08, 0.21) | −0.04 (−0.13, 0.05) | 0.15 (0.07,0.23) | 0.18 (0.10, 0.27) |

| Relative difference from baseline and between groups, % (95% CI) | −0.0 (−3.2, 3.2) | −1.9 (−5.0, 1.2) | 8.8 (5.5, 12.3) | −1.9 (−6.1, 2.6) | 8.9 (4.1, 13.9) | 11.0 (6.1, 16.0) |

Estimates were generated using mixed-effects models with log-transformed 10-year ASCVD risk scores. Means and SE were exponentiated before presentation.

This estimate is the 10-year ASCVD risk score, which is the calculation of the 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event.

Compared with the control diet, changes in 10-year ASCVD driven by decreases in SBP from the F/V and DASH diets were −7.9% and −14.6%, respectively. Compared with F/V, decreases in SBP from DASH changed ASCVD by −7.2%. In contrast, the effect of HDL cholesterol on ASCVD was −1.9% for the F/V diet and 8.8% for the DASH diet, with DASH increasing 10-year ASCVD risk scores by 11% compared with the F/V diet. The effect of total cholesterol on 10-year ASCVD risk score was −0.2% for the F/V diet and −3.5% compared with the control diet. Compared with the F/V diet, the effect of the DASH diet on total cholesterol nonsignificantly changed 10-year ASCVD risk by −3.3%.

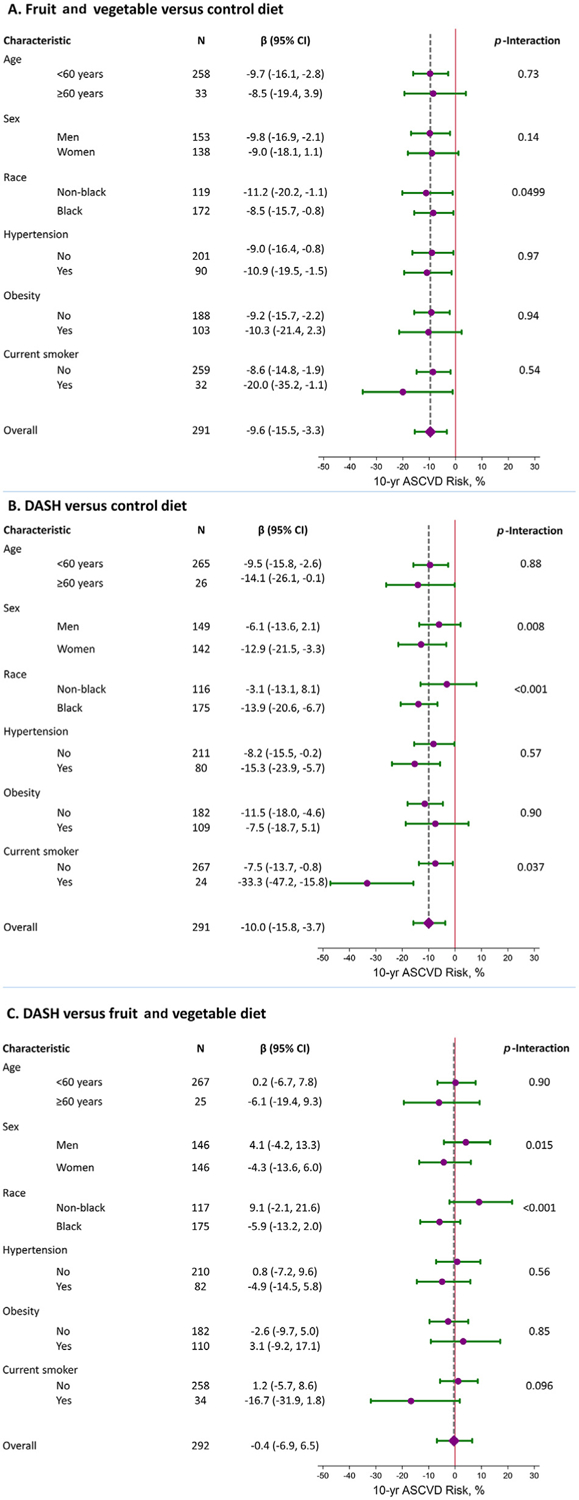

DASH changed 10-year ASCVD risk score by −12.9% in women compared with −6.1% in men (p = 0.008) (Figure 2). Moreover, DASH changed 10-year ASCVD risk score by −13.9% in Black adults versus 3.1% in non-Black adults (p <0.001). There was no evidence of effect modification across strata for F/V versus the control.

Figure 2.

Relative reduction (95% CI) in 10-year ASCVD risk score in strata of age, gender, race, hypertension, obesity, and current smoking status, comparing the fruit and vegetable diet to the control diet (A), the DASH diet compared with the control diet (B), and the DASH diet compared with the fruit and vegetable diet (C). The diamond and vertical dashed line represent the relative reduction for the entire population compared overall comparison.

Discussion

In a diverse group of adults with elevated BP, not on medications for BP, lipid, or glucose management, both the DASH diet and a diet high in F/V reduced 10-year ASCVD risk scores to a similar degree (relative reduction of ~10%). The effects of the DASH diet were greater in women and Black adults. Although the DASH diet reduced risk factors associated with 10-year ASCVD risk (i.e., SBP and total cholesterol) more so than F/V, the DASH diet also reduced HDL, a finding that would increase estimated 10-ASCVD risk. In contrast, the F/V diet reduced SBP to a lesser degree but did not affect HDL, resulting in a similar net difference in overall ASCVD risk reduction as the DASH diet.

Previous efforts to investigate the net effect of different dietary interventions on CVD events have used the Framingham Heart Study (FRS) coronary heart disease risk score, which was derived from a single municipal area and included a predominantly White middle-class, North-Eastern American male population.14 Chen et al14 documented a statistically significant reduction in 10-year coronary heart disease risk in participants on the DASH diet compared with those on a diet rich in F/V. However, the applicability of the FRS to a more diverse and contemporary US population has been debated as the score tends to overestimate risk in low-risk populations and underestimate risk in high-risk populations.15,16 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines currently recommends the Pooled Cohort Equation risk calculator, used in our study, to estimate 10-year ASCVD risk as the Pooled Cohort Equation was derived from multiple community-based cohorts. Previous work has shown that the FRS underestimates subclinical atherosclerotic risk in asymptomatic women.17 Moreover, the Pooled Cohort Equation allows for better risk estimations in Black adults who bear a disproportionate burden of CVD morbidity and mortality in the United States.18,19 Our study extends the existing literature by investigating the effects of DASH or DASH-like dietary patterns on predicted ASCVD risk using the Pooled Cohort Equation. In contrast to the study by Chen et al,14 our study did not find an overall advantage of the DASH diet compared with the F/V diet.

Our results are consistent with previous work demonstrating that both the DASH and F/V diets were associated with equal reductions in markers of subclinical cardiac damage and strain, namely high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, in adults without preexisting CVD.9 The more complex DASH diet did not decrease markers of subclinical damage over a diet high in F/V. Similar findings were observed in the OMNIHEART study, which found that 3 healthy diets (DASH, a DASH-like diet rich in proteins, and a Mediterranean-like diet) lowered high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I and high-sensitivity−C-reactive protein levels over 6 weeks without significantly different effects between diets.10

One of the primary reasons for the equivalent 10-year ASCVD risk estimates of the DASH and F/V diets pertains to their differing effects on HDL cholesterol. Higher levels of HDL cholesterol have traditionally been viewed as cardioprotective based on observational evidence.20 However, trials targeting HDL cholesterol (e.g., niacin) have not demonstrated reductions in CVD events,21−23 and torcetrapib, which raises HDL cholesterol, increased CVD events.24 Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that distinct HDL cholesterol subtypes may confer distinct health benefits.25 It should be noted that despite the equivalence in 10-year ASCVD risk, the HDL cholesterol/total cholesterol ratio, an important predictor of CVD events, was marginally improved with DASH.11 Therefore, further work is needed on the longer-term CVD effects from diet, which is beyond the scope of the 8-week intervention period in the present study.

Our study suggests that the benefits associated with these diets may vary by gender. Although a diet rich in F/V produced comparable reductions in 10-year ASCVD risk score between men and women, the reduction in 10-year ASCVD risk score associated with the DASH diet were twice as large in women than men. CVD is the leading cause of death in women.26 Hypertension is also more strongly associated with heart failure and death in women, and women are less likely to receive risk factor modification therapy (e.g., fewer statin prescriptions).27 Therefore, our findings that DASH may be more efficacious in women are relevant for lifestyle counseling in this demographic group.

Similarly, whereas a diet rich in F/V led to a modestly smaller reduction in 10-year ASCVD risk score in Black participants, the effect with the DASH diet was 4 times as large in Black than non-Black participants. This is particularly relevant as dietary pattern has been identified as one of the most important mediators of hypertension risk in Black adults.28 The impact of disparities on access to healthy foods has been a major focus of policy effects to promote higher intake of F/V in Black adults. However, our study suggests that public policies simply focused on F/V may fall short of the CVD prevention benefits observed from the complete DASH dietary pattern.

Although our study has many strengths (e.g., its controlled intervention, randomized design, high follow-up rates, and standardized assessments), it should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. CVD risk was assessed using estimation from the ASCVD calculator and was not a reflection of actual CVD events. The estimates also assume that the difference in cardiovascular risks over 8 weeks is sustained over the long term. Finally, the DASH trial was conducted nearly 30 years ago; it is possible that the typical American diet has improved somewhat, that is, reduction in % energy intake in saturated fat, which suggests that the benefits of the DASH and F/V diets might be somewhat less than projected in our study.

In summary, although DASH and F/V diets reduced 10-year ASCVD risk by 10% over an 8-week period, DASH was more efficacious in women and Black adults. These results support ongoing public health initiatives to promote greater consumption of F/V at large and the DASH diet, especially in women and Black adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors are indebted to the study participants for their sustained commitment to the DASH trial.

Dr. Juraschek is supported by the National Institute of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Bethesda, Maryland) grants K23HL135273-03 and R21HL144876-01.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.10.019.

References

- 1.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, Boehme AK, Buxton AE, Carson AP, Commodore-Mensah Y, Elkind MSV, Evenson KR, Eze-Nliam C, Ferguson JF, Generoso G, Ho JE, Kalani R, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Levine DA, Lewis TT, Liu J, Loop MS, Ma J, Mussolino ME, Navaneethan SD, Perak AM, Poudel R, Rezk-Hanna M, Roth GA, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Thacker EL, VanWagner LB, Virani SS, Voecks JH, Wang N-Y, Yaffe K, Martin SS. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022;145: e153–e639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Vadiveloo M, Hu FB, Kris-Etherton PM,Rebholz CM, Sacks FM, Thorndike AN, Van Horn L, Wylie-Rosett J. 2021 Dietary guidance to improve cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;144:e472–e487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand SS, Hawkes C, de Souza RJ, Mente A, Dehghan M, Nugent R,Zulyniak MA, Weis T, Bernstein AM, Krauss RM, Kromhout D, Jenkins DJA, Malik V, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Mozaffarian D, Yusuf S, Willett WC, Popkin BM. Food consumption and its impact on cardiovascular disease: importance of solutions focused on the globalized food system: a report from the workshop convened by the World Heart Federation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1590–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD,Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, Michos ED, Miedema MD, Muñoz D, Jr Smith SC, Virani SS, Sr Williams KA, Yeboah J, Ziaeian B. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;140:e596–e646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, Goldberg R, Heidenreich PA, Hlatky MA, Jones DW, Lloyd-Jones D, Lopez-Pajares N, Ndumele CE, Orringer CE, Peralta CA, Saseen JJ, Smith SC, Sperling L, Virani SS, Yeboah J. AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice guidelines. Circulation 2019;139:e1082–e1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D’Agostino RB, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ, Robinson JG, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC, Sorlie P, Stone NJ, Wilson PWF, Jordan HS, Nevo L, Wnek J, Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Smith SC, Tomaselli GF. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129(suppl 2):S49–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin SS, Sperling LS, Blaha MJ, Wilson PWF, Gluckman TJ, Blumenthal RS, Stone NJ. Clinician-patient risk discussion for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease prevention: importance to implementation of the 2013 ACC/AHA Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:1361–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, Bray GA, Vogt TM, Cutler JA, Windhauser MM, Lin PH, Karanja N. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juraschek SP, Kovell LC, Appel LJ, Miller ER, Sacks FM, Christenson RH, Rebuck H, Chang AR, Mukamal KJ. Associations between dietary patterns and subclinical cardiac injury: an observational analysis from the DASH trial. Ann Intern Med 2020;172:786–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovell LC, Yeung EH, Miller ER 3rd, Appel LJ, Christenson RH,Rebuck H, Schulman SP, Juraschek SP. Healthy diet reduces markers of cardiac injury and inflammation regardless of macronutrients: results from the OmniHeart trial. Int J Cardiol 2020;299:282–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obarzanek E, Sacks FM, Vollmer WM, Bray GA, Miller ER, Lin PH,Karanja NM, Most-Windhauser MM, Moore TJ, Swain JF, Bales CW, Proschan MA, DASH Research Group. Effects on blood lipids of a blood pressure−lowering diet: the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacks FM, Obarzanek E, Windhauser MM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM,McCullough M, Karanja N, Lin PH, Steele P, Proschan MA. Rationale and design of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension trial (DASH). A multicenter controlled-feeding study of dietary patterns to lower blood pressure. Ann Epidemiol 1995;5:108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D’Agostino RB, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ, Robinson JG, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC, Sorlie P, Stone NJ, Wilson PWF. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2935–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen ST, Maruthur NM, Appel LJ. The effect of dietary patterns onestimated coronary heart disease risk: results from the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:484–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brindle P, Beswick A, Fahey T, Ebrahim S. Accuracy and impact ofrisk assessment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Heart 2006;92:1752–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM. The pooled cohort risk equations-Blackrisk matters. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:12–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michos ED, Nasir K, Braunstein JB, Rumberger JA, Budoff MJ, Post WS, Blumenthal RS. Framingham risk equation underestimates subclinical atherosclerosis risk in asymptomatic women. Atherosclerosis 2006;184:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muntner P, Colantonio LD, Cushman M, Goff DC, Howard G,Howard VJ, Kissela B, Levitan EB, Lloyd-Jones DM, Safford MM. Validation of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease pooled cohort risk equations. JAMA 2014;311:1406–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topel ML, Shen J, Morris AA, Al Mheid I, Sher S, Dunbar SB, Vaccarino V, Sperling LS, Gibbons GH, Martin GS, Quyyumi AA. Comparisons of the Framingham and pooled cohort equation risk scores for detecting subclinical vascular disease in Blacks versus Whites. Am J Cardiol 2018;121:564–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagao M, Nakajima H, Toh R, Hirata KI, Ishida T. Cardioprotectiveeffects of high-density lipoprotein beyond its anti-atherogenic action. J Atheroscler Thromb 2018;25:985–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Investigators AIM-HIGH, Boden WE, Probstfield JL, Anderson T,Chaitman BR, Desvignes-Nickens P, Koprowicz K, McBride R, Teo K, Weintraub W. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2255–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HPS2-THRIVE Collaborative Group, Landray MJ, Haynes R, Hopewell JC, Parish S, Aung T, Tomson J, Wallendszus K, Craig M, Jiang L, Collins R, Armitage J. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2014;371:203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalil RS, Wang JH, de Boer IH, Mathew RO, Ix JH, Asif A, Shi X,Boden WE. Effect of extended-release niacin on cardiovascular events and kidney function in chronic kidney disease: a post hoc analysis of the AIM-HIGH trial. Kidney Int 2015;87:1250–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJP,Komajda M, Lopez-Sendon J, Mosca L, Tardif JC, Waters DD, Shear CL, Revkin JH, Buhr KA, Fisher MR, Tall AR, Brewer B, ILLUMINATE Investigators. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2109–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sacks FM, Liang L, Furtado JD, Cai T, Davidson WS, He Z, McClelland RL, Rimm EB, Jensen MK. Protein-defined subspecies of HDLs (high-density lipoproteins) and differential risk of coronary heart disease in 4 prospective studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020;40:2714–2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC. Women and heart disease. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/women.htm Accessed on July 25, 2022.

- 27.American College of Cardiology. Cardiovascular care of women: understanding the disparities. Available at: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/08/01/12/42/http%3a%2f%2fwww.acc.org%2flatest-in-cardiology%2farticles%2f2020%2f08%2f01%2f12%2f42%2ffeature-cardiovascular-care-of-women-understanding-the-disparities. Accessed on July 25, 2022.

- 28.Howard G, Cushman M, Moy CS, Oparil S, Muntner P, Lackland DT,Manly JJ, Flaherty ML, Judd SE, Wadley VG, Long DL, Howard VJ. Association of clinical and social factors with excess hypertension risk in Black compared with White US adults. JAMA 2018;320:1338–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.