Abstract

The active site of a protein folding reaction is in domain V of the 23S rRNA in the bacterial ribosome and its homologs in other organisms. This domain has long been known as the peptidyl transferase center. Domain V of Bacillus subtilis is split into two segments, the more conserved large peptidyl transferase loop (RNA1) and the rest (RNA2). These two segments together act as a protein folding modulator as well as the complete domain V RNA. A number of site-directed mutations were introduced in RNA1 and RNA2 of B.subtilis, taking clues from reports of these sites being involved in various steps of protein synthesis. For example, sites like G2505, U2506, U2584 and U2585 in Escherichia coli RNA1 region are protected by deacylated tRNA at high Mg2+ concentration and A2602 is protected by amino acyl tRNA when the P site remains occupied already. Mutations A2058G and A2059G in the RNA1 region render the ribosome Eryr in E.coli and Lncr in tobacco chloroplast. Sites in P loop G2252 and G2253 in E.coli are protected against modification by the CCA end of the P site bound tRNA. Mutations were introduced in corresponding nucleotides in B.subtilis RNA1 and RNA2 of domain V. The mutants were tested for refolding using unfolded protein binding assays with unfolded carbonic anhydrase. In the protein folding assay, the mutants showed partial to complete loss of this activity. In the filter binding assay for the RNA–refolding protein complex, the mutants showed an extent of protein binding that agreed well with their protein folding activity.

INTRODUCTION

We have shown that ribosomes act as protein folding modulators in vivo and in vitro (1–6). This finding was corroborated by experiments from a number of other laboratories (7,8). The protein folding activity was tracked down to domain V of the 23S bacterial ribosomal RNA, known for harboring the peptidyl transferase center and having a secondary structure and a number of nucleotides in the loop region that have been conserved throughout evolution. The structure–function relationship of this RNA segment became easier to study when we could split domain V into the more conserved central loop region (RNA1) and the variable stem–loop region (RNA2) outside the central loop. These two RNA segments complement each other in the folding reaction as follows. RNA1 binds the polypeptide chain as it begins to fold; the RNA1 bound protein undergoes some alteration in its structure and can then be dissociated from RNA1 by RNA2 in a folding competent state (9).

We generated a few mutants in RNA1 by site-directed mutagenesis and checked the protein folding ability of these mutants. Mutations were also introduced in RNA2 and selected for their inability to participate in the folding reaction, namely their failure to release the refolding protein from RNA1. The ultimate aim was to see whether the same mutations could be introduced in 23S rRNA, and selection carried out for those that are proficient in protein synthesis but deficient in protein folding. Alternatively, failure to produce such mutants would strongly imply that the sites for peptidyl transferase reaction in domain V overlap with the sites required for folding the protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Escherichia coli XLIB was employed as the host for plasmids. Plasmids pDK105 and pDK106 contained the whole domain V and the central loop only (RNA1) from Bacillus subtilis, respectively. These plasmids were linearized with appropriate restriction enzymes and used as templates for synthesis of whole or part of domain V RNA of B.subtilis (10). The PCR products were cloned in the vector pGEM4Z under T7 promoter. The medium for liquid cultures was LB and all incubations were at 37°C.

PCR reaction

Point mutations were introduced in vitro at desired bases in domain V by PCR. For SDM3′E and SDM5′E, mutations were incorporated into the PCR product raised from pDK106 with the mutated primers SDM3′E and SDM5′E containing the desired mutations at one end and normal primers SP2 and SP1, respectively, at the other (Table 1). Both primers contained restriction sites for cloning at the ends.

Table 1. Oligonucleotides used for site-directed mutations by PCR in RNA1 and RNA2.

| Primer name | Sequence | Primer length | Position of mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SP1 | ACC GAA TTC GGA TCC TTT CCA GCG CCC GCG ACG | 33 | – |

| SP2 | GAG AAA GAG AAG CTT GCA GGT TAC CCG CGA CAG | 33 | – |

| SP3 | GGA CTG AAT TCG GGG TAG CTT TTA TCC GTT GA | 32 | – |

| SDM3′E | GAG AAA GAG GGA TCC CCC GCG ACG GAT AGG GGC CGA ACC GTC TCA CG | 47 | A2629G, U2636C |

| SDM5′E | GAG AAA GAG AAG CTT ACC CGC GAC AGG ACG GGG AGG CCC CGT GGA | 45 | A2085G, A2086G, A2089G |

| SDM6 | GGC ACC TCG ACA CCG GCT CAT CG | 23 | U2531C, G2532A, U2533C |

| SDM8 | GCG AGC TGG GCC CAG AAC GTC G | 22 | U2611C, U2612C |

| SDM3 | GTT TGA CTG GCC AGG TCG CCT CC | 23 | G2579C, G2580C, G2581A |

The mutation sites are shown in bold. The cloned mutants were sequenced to ensure that only the desired changes were introduced in the entire length of the RNA molecules.

Mutations in SDM6 and SDM8 were introduced by a two- step PCR using pDK106 as the template (11). In the first step, primers SDM8 and SDM6, which contained the altered bases, were used along with one of the terminal primers SP1 at the 3′ end (Table 1). Products with lengths of 75 and 150 nt, respectively, were obtained. To introduce point mutations in RNA2, the first step PCR was carried out with the primers SDM3 and SP3 using plasmid pDK105 as the template. A 210 bp long fragment was obtained. These first step PCR products were purified by High Pure PCR purification kit (Boehringer Mannheim). These products were subjected to mung bean nuclease digestion to chew off 3′ terminal overhang A, which could possibly be incorporated by Taq DNA polymerase (12). One unit of mung bean nuclease (Promega) was used per µg of DNA in a 50 µl reaction mixture, which contained 10 mM sodium acetate buffer pH 5.0, 1 mM l-cysteine, 0.1 mM zinc acetate pH 5.0, 50 mM NaCl and 5% glycerol. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 15 min. The PCR products were then eluted from the 2% agarose gel by the phenol freeze–thaw method. These products were used as mega primer at the 3′ end in the second step PCR. The normal primer SP2 was used at the 5′ end for SD8 and SDM6, with pDK106 as the template, and for SDM3 with pDK105 as the template, respectively. The PCR was carried out in a 50 µl reaction mixture, containing recommended buffer 10 mM Tris–HCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl pH 8.3, 20°C (Roche Biochemicals, Germany), 200 nM dNTP, 300 nM of each primer and 5 U of Taq DNA polymerase. The thermal parameter was 95°C, 30 s (denaturation); 55°C, 45 s (annealing); 72°C, 1 min (elongation); for 30 cycles in the thermocycler (Bio-Rad).

Cloning of the PCR products in pGEM4Z

The PCR products were digested with HindIII and EcoRI at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. They were ligated in the vector pGEM4Z digested with the same set of enzymes. The ligation reaction was carried out with 5 U of T4 DNA ligase (Boehringer Mannheim) of the Rapid DNA ligation kit in a total reaction volume of 20 µl containing dilution buffer and ligation buffer, the vector:insert ratio being kept at 1:3. The mixture was incubated at 15°C for 24 h. The ligated products were transformed in E.coli XLIB and selected for in the presence of marker ampicillin and β-galactosidase inducer IPTG and X-Gal. Plasmid DNA was isolated from the selected colonies (13) and the mutations were confirmed by Thermo Sequencing by [γ-32P]ATP end-labeled primers using a Thermo sequencing kit (USB).

Synthesis of run off transcripts

The plasmids with mutants of RNA1 and RNA2 regions were linearized with EcoRI. Similarly, the templates for wild-type RNA1 and RNA2 were obtained by linearizing plasmids pDK106 and pDK105 by EcoRI and SmaI, respectively. In vitro transcription was carried out on these plasmids in a total reaction volume of 20 µl, which contained 40 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 6 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM spermidine, 1 mM each of RNTP, 1 µg of linearized DNA template, 1 µl [32P]UTP (10 µCi/µl, 4000 Ci/mM) and 25 U of placental RNase inhibitor. T7 RNA polymerase (20 U) was used in each reaction to transcribe the mutant RNA1 and RNA2. SP6 RNA polymerase (20 U) was used for transcription of the wild-type RNA. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The products were extracted with phenol–chloroform followed by ethanol–ammonium acetate precipitation. The quantity of RNA synthesized was calculated from the amount of radioactivity incorporated. The size of the transcripts was checked by running them on a 5% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea.

Unfolding and refolding of enzymes

We showed the protein folding ability of domain V of 23S ribosomal RNA with a large number of proteins like alkaline phosphatase, lactate and malate dehydrogenases, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, glucose oxidase, restriction endonucleases, β-lactamase, carbonic anhydrase (CA) (1–6). In the experiments reported here, we have chosen the enzyme CA because it a monomer of relatively small size.

Human CA (EC 4.2.11), purchased from Sigma, gave monomeric single bands of molecular weight 29 800 in SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. All laboratory reagents used were of analytical grade. CA was denatured at a concentration of 12 µM with 6 M guanidine–HCl for 3 h at 25°C. The protein lost its secondary structure as revealed by its CD spectrum. For refolding, the denatured protein was diluted 100-fold (final concentration 120 nM) in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 5 mM magnesium acetate and 200 mM NaCl, and incubated at 25°C for 15 min for self-folding. When RNA1 and RNA2 were used for refolding, the unfolded enzyme was allowed 5 min at 25°C to bind to RNA1. RNA2 was then added at the same concentration as RNA1. Following a further incubation for 15 min at 25°C, the activity of the refolded protein was measured (9). The residual guanidine–HCl concentration after dilution of unfolded enzyme did not interfere with the refolding activity. The activity of the refolded enzyme was assayed by adding 500 µM p-nitrophenyl acetate to the refolding mixture and measuring the increase in A400 with time at 25°C. The concentrations of the enzymes and ribosomal RNA, the time of incubation for refolding the unfolded protein, etc., varied in different experiments and are mentioned in the appropriate places.

Binding assay of unfolded protein with RNA

To study the binding of the unfolded protein to RNA1 and its mutants, increasing concentrations of denatured CA were allowed to refold in the refolding buffer at a fixed RNA1 concentration, in separate sets. The wild-type and mutant RNA1s carried the label of [α-32P]UTP. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 5 min and filtered through 0.45 µm pre-soaked nitrocellulose filter paper (Sartorious). The filter papers were dried and 32P counts were taken in a Beckman (LS 6000, SE) liquid scintillation counter. The percentage of radioactivity retained on the filter paper was calculated. The wild-type RNA1 served as the control. The RNA bound to denatured protein was retained on the filter while the free RNA passed through it.

The release of RNA1 from the RNA1–protein complex was monitored by a similar approach. The unfolded protein was allowed to form a stable complex with the [α-32P]UTP-labeled wild-type RNA1 for 5 min at 25°C. Mutant or wild-type unlabeled RNA2 was then added to the reaction mixture at the same concentration as RNA1 and after 15 min the samples were filtered through 0.45 µm nitrocellulose filter paper. The percentage of retained count was measured.

RESULTS

Refolding of unfolded carbonic anhdrase with RNA1 and its mutants

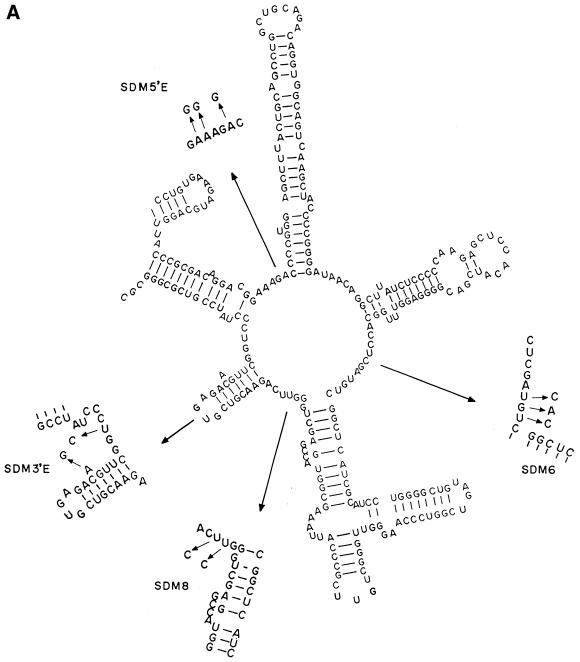

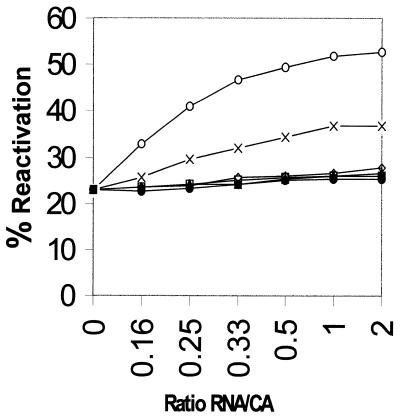

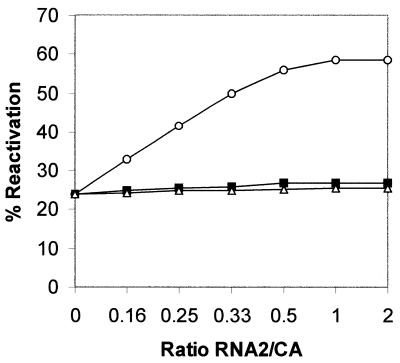

Since we do not have any selection procedures for protein folding deficiency of ribosomal RNA, we introduced a number of site-directed mutations into domain V of B.subtilis and tested for their protein folding ability. Four sets of multiple site-directed mutations in RNA1 were found to have an effect on protein folding. These were SDM5′E (A2085G, A2086G, A2089G), SDM6 (U2531C, G2532A, U2533C), SDM8 (U2611C, U2612C) and SDM3′E (A2629G, U2636C) as represented in Figure 1A. Although the numbering differs in the case of E.coli, the same nucleotides occupy identical positions in the secondary structure of domain V RNA as in the case of B.subtilis. Many of the nucleotides mentioned here are involved in different activities related to protein synthesis, for example, mutation A2085G in E.coli causes resistance to erythromycin (14), A2086G renders lincomycin-resistant tobacco chloroplasts, and A2089 is responsible for chloramphenicol resistance in mouse mitochondria (15). U2611 and U2636 correspond to E.coli U2584 and U2609, respectively, which are protected in chemical footprinting experiments by the CCA end of the P-site bound N-acetyl-Phe-tRNA (16). Nucleotide U2531, corresponding to U2504 of E.coli, could bind to the 3′ end of amino acyl tRNA during the peptidyl transferase reaction (17). All four mutants were tested for their protein folding activity as follows. Unfolded CA was allowed to bind for 5 min at 25°C to different concentrations of RNA1. Then RNA2 was added to each sample at the same concentrations as RNA1. After a further incubation for 15 min the activity of refolded protein was measured (9). It was found that three mutants were completely deficient in folding CA and one mutant (SDM6) was half as efficient in folding the protein as the wild-type RNA1 (Fig. 2). With wild-type RNA1 we get a maximum recovery of activity of CA ∼50% while it was 20% in the control without RNA1. The reason for the partial recovery of activity was the ability of RNA1 to refold only the protein molecules that bound to it at a very early stage of refolding. Those that failed to bind RNA1 at a very early stage went into the unproductive self-folding pathway. If we compare the protein with substrate and the RNA1 with enzyme, it is a situation where the substrate conformation changed rapidly with time and the enzyme could not recycle to bind fresh substrate after one round of refolding. This is also reflected in the inability of the refolding protein to sequester all the RNA molecules as shown below.

Figure 1.

(A) The secondary conformation of RNA1 with point mutations introduced as shown by arrows in the regions blown up in the figure. (B) The secondary conformation of RNA2 with the point mutations introduced in the P-loop region as shown by arrows in the blown up P-loop segment.

Figure 2.

Refolding of unfolded CA in the presence of wild-type and four mutants of RNA1. The refolding was done by 15 min incubation in the absence of RNA as control (filled circles) and by 5 min incubation with different RNA1 molecules followed by 15 min incubation after addition of wild-type RNA2 at an equimolar concentration with RNA1. RNA1 wild-type, open circles; mutants SDM6, crosses; SDM8, open squares; SDM 5′E, open rhombus and SDM 3′E, open triangles.

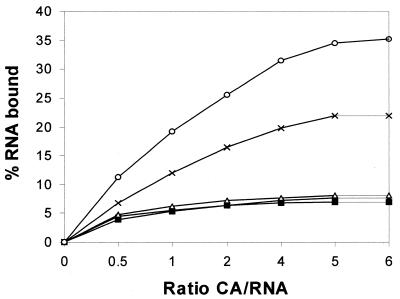

Binding of refolding carbonic anhydrase with RNA1 and its mutants

We have seen that the refolding protein binds quite strongly to RNA1. The complex is stable and can be identified by gel retardation, gel filtration and binding to nitrocellulose filter paper (18). We assayed the binding of unfolded CA with RNA1 mutants using nitrocellulose filter paper. The 32P-labeled RNA bound to the refolding protein could stick to the filter paper, while the RNA itself passed through. The pattern of binding of the wild-type and mutant RNA1 was in line with the ability of these RNA1 molecules to fold CA. Whereas maximum binding was observed with the wild-type RNA1, about half as much binding was observed with SDM6. Other mutants failed to bind any unfolded protein (Fig. 3). The reason for the failure to get all the unfolded protein to bind to RNA1 has been discussed earlier.

Figure 3.

Filter binding of [32P]RNA1 bound to unfolded CA. Unfolded CA at various concentrations was added to a fixed concentration of RNA1, and after 15 min the protein–RNA complex was trapped on a nitrocellulose filter for RNA1 wild-type (open circles) and RNA1 mutants SDM6 (crosses), SDM8 (open triangles), SDM3′E (filled squares) and SDM5′E (filled circles).

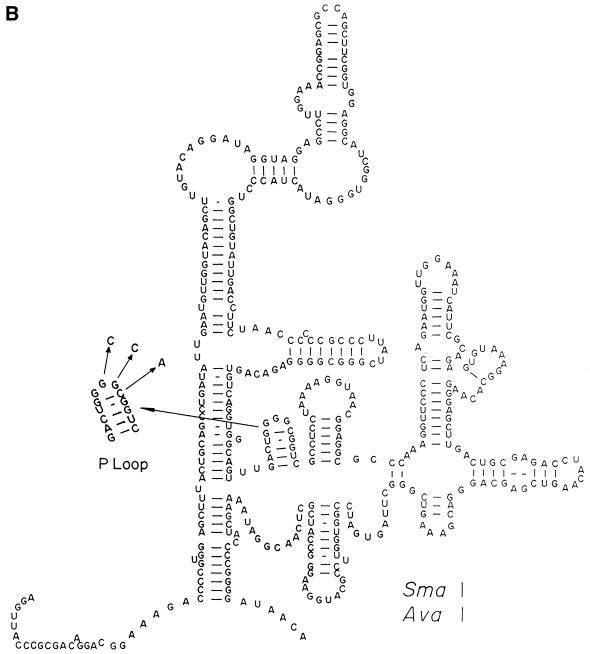

Effect of mutations in RNA2 on protein folding and filter retention of RNA1

One mutation set in the P loop in the RNA2 region (SDM3: G2579C, G2580C and G2581A) shown in Figure 1B completely knocked out its ability to act in folding CA (Fig. 4). Chemical footprinting by the 3′ terminal CCA of P site-bound tRNA protects these sites. Base substitution here can impair growth, translation fidelity (18,19) and peptidyl transferase activity (20–23).

Figure 4.

Refolding of unfolded CA bound to RNA1 and then released by RNA2, wild-type (circles) and mutant SDM3 (squares). Control shows self-folding of CA (triangles).

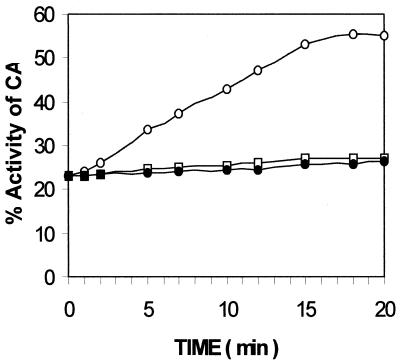

When RNA2 was added to the wild-type RNA1–refolding protein complex in a ratio of protein:RNA1:RNA2 of 4:4:1, the time course of refolding of CA appeared as in Figure 5. Here, RNA2 was added at one-quarter the molar concentration of RNA1 to slow down the refolding process, so that the time course could be measured accurately. With RNA2 at the same concentration or higher than that of RNA1, the refolding would be fast and the time course could not be followed accurately. There was no increase in activity of the protein in the presence of mutant (SDM3) RNA2. With wild-type RNA2, there was a gradual increase in refolding of CA, as expected from our earlier observations. We have shown earlier that RNA2 dissociates the refolding protein from RNA1 in a folding competent state and recycles it if the RNA1:RNA2 ratio is high (9).

Figure 5.

Time course of refolding of RNA1-bound unfolded CA in the presence of RNA2. The wild-type RNA1–protein complex was formed in 5 min, at 25°C, by adding an equimolar concentration of CA and RNA1 (120 nM each). Refolding was initiated by adding RNA2 wild-type (open circles) and mutant (squares) at one-quarter the concentration of RNA1, so that the enzyme could be folded slowly to enable accurate measurements. The control (filled circles) shows self-folding of CA.

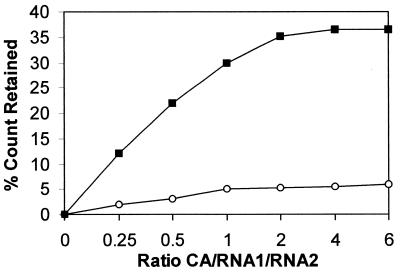

In the filter binding assay, α-32P-labeled RNA1 could be trapped when unfolded CA was bound to it. After 5 min incubation with RNA1, an equimolar amount of wild-type or mutant RNA2 was added to the RNA1–protein complex and it was incubated for a further 15 min. The filter binding showed that mutant RNA2 (SDM3) could not dissociate the refolding protein from RNA1, whereas wild-type RNA2 could do so (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Filter binding of 32P-labeled RNA1–unfolded CA complex where RNA2 wild-type (circles) and mutant SDM3 (squares), at equimolar concentrations with RNA1, were added to the complex and incubated for an additional 15 min.

DISCUSSION

Since we have not been able to design an experiment that could select protein folding defective ribosomal mutants, we proceeded to introduce site-directed mutations at various positions in domain V of the 23S rRNA, which acts as the protein folding modulator. Two possible situations could have arisen. If active sites for peptidyl transferase and protein refolding were non-overlapping, we would possibly be able to get mutants defective in one of these functions and not the other. But if the two active sites were overlapping, attempts to discover mutations exclusively defective in protein folding activity could fail. We introduced a number of site-directed mutations in RNA1 and RNA2. Some of the mutants had a number of nucleotides changed and turned out to be deficient in protein folding. Many of the mutations have been known to cause a number of different changes in the functions related to protein synthesis. Most of the mutations coincide with antibiotic resistance mutations, tRNA recognition sites implicated in fidelity of translation and sites that interact with the newly synthesized polypeptide chain as it interacts with the 50S subunit after completion of its synthesis (post-translation). For example, A2059 and A2062 in SDM5′E correspond to chloramphenicol resistance (24,25) in E.coli. SDM 5′E RNA1 is completely deficient in protein folding, maybe because of three A→G changes, which significantly affect secondary structure, almost eliminating the single-stranded stretch AAAGA. Also, in vitro transcribed RNA, harboring identical mutations in intact E.coli domain V, eliminate its capacity to refold denatured CA (S.Chowdhury, unpublished observation). The mutations abolish the ability of RNA1 to bind refolding protein molecules.

In SDM6, mutation U2531C corresponds to U2504C in E.coli, causing increased read through of stop codons and frame shifting, and consequent lethality (26). Mutation U2532A corresponds to E.coli U2505A which reduces the peptidyl transferase activity of 70S ribosome to 14% (27). Severe reduction of the 70S activity in E.coli is also caused by U2506C corresponding to U2533 in B.subtilis. In such a background the triple mutant is not inactive but shows only 50% loss of protein folding activity.

The mutant SDM8 also has its analog in E.coli. U2611C and the U2612C analog in E.coli show 20% activity of the 70S ribosome (27) and <6% peptidyl transferase activity with loss of tRNA fragment binding (28), respectively. These two sites are protected by P site tRNA (16). SDM8 is completely deficient in protein folding.

The mutation A2629G in SDM3′E corresponds to A2602G in E.coli, a universally conserved nucleotide that causes inhibition of peptide elongation to a level of 10% (29). It is the binding site of the antitumor antibiotic sparsomycin in the presence of N-blocked P-site bound tRNA which increases the accessibility of A2602 on the ribosome (30). U2636 in B.subtilis corresponds to U2609 in E.coli. Nucleotides A2602 and U2609 are protected by A site tRNA. In our experiments, A2629G and U2636C double mutant completely lacks protein folding activity. Mutations introduced at identical positions of in vitro transcripts of total domain V RNA showed similar effects (S.Chowdhury, unpublished observation).

The RNA2 SDM3 in our experiment is a triple mutant (G2579C, G2580C and C2581A) and is completely deficient in protein folding by virtue of the inability of this mutant RNA2 to release the refolding protein from RNA1 bound state. The corresponding E.coli mutation G2252C has <5% peptidyl transferase activity (27) and a reduced rate of peptidyl transferase activity in vitro (20,21). This mutation also interferes with the binding of the peptidyl tRNA to the P site of the 50S subunit. Mutations in the P loop perturb the conformation, disturbing the A site interaction with CCA end tRNA (31). The double mutant is detrimental to cell growth (26). Mutant G2253C in E.coli is also slow growing and has reduced fidelity in tRNA selection.

We have seen that a number of nucleotides in domain V RNA each interact with a large number of different proteins during refolding (S.Pal, S.Chowdhury, N.Das, J.Ghosh, A.DasGupta and C.DasGupta, manuscript submitted). These nucleotides are different from the mutated ones that we are reporting here and there is no overlap. But that does not make the two sets mutually exclusive. The activity of the RNA depends on both its tertiary structure and some conserved nucleotides that are involved in specific interactions. Mutations might change one or both of these things. In any event, we plan to mutate the specific bases and see what effect it produces on protein folding.

In another approach by Choi and Brimacombe (32), the N-terminal end of the growing polypeptide chain has been shown to make contact with a number of nucleotides, mostly in domain V RNA of E.coli. Among those nucleotides, A2062, U2506, U2585 and U2609 correspond to the nucleotides A2089, U2533, U2612 and U2636 of B.subtilis, which have been mutated in our experiments.

In this set of initial experiments with site-directed mutations in RNA1 and RNA2, we put in multiple mutations to ensure that with most of them we saw a significant effect on protein folding. Since the consecutive or very closely spaced nucleotides mutated together in our experiments are involved in unique activities in protein synthesis, like binding of P site tRNA, conferring antibiotic resistance, providing peptidyl transferase reaction, etc., we thought it might be necessary to mutate them together to get the desired effect.

Again, there could be drastic changes in the secondary structure of RNA1 and RNA2 as a result of introducing mutations, which might cause the loss of activity. When we checked the putative secondary structure of the RNA molecules (33,34) we found that mutations SDM3′E, SDM8 and SDM5′E distort the central loop of RNA1 significantly. These three sets of mutations completely eliminate the protein folding activity of RNA1. SDM6 does not distort the central loop visibly, although it eliminates the single-stranded regions between helices 73 and 74 and also reduces the length of helix 93. But this mutant is still half as active as the wild-type RNA1. Therefore, the preservation of the large peptidyl tranferase loop appears to be more important for the activity of RNA1. On the other hand, mutation SDM3 in RNA2 does not affect the secondary structure so drastically, yet is completely deficient in protein folding. These clustered mutations in the P loop, however, alter the site that is protected by CCA of P site-bound tRNA and could drastically affect the activity of the RNA2 region of domain V.

Now that we have a number of effective mutations, we will introduce them one at a time. If we get the desired effect with a single point mutation, it will be easier to evolve structure–function correlation for domain V RNA in protein synthesis and folding. The most promising candidates for single base mutations appear to be those marked by Choi and Brimacombe (32), who found that the newly synthesized polypeptide chain interacts mostly with the nucleotides in domain V of E.coli 23S rRNA, a study more akin to our experiment of protein folding on this RNA. We will also introduce site-directed mutations in nucleotides that bind to refolding protein (S.Pal, S.Chowdhury, N.Das, J.Ghosh, A.DasGupta and C.DasGupta, manuscript submitted). Finally we will go for in vitro selection for random mutations in domain V to be able to see the role of every nucleotide in this RNA segment on protein folding. Reverse genetics can then be used to find out if we could isolate bacteria capable of protein synthesis but deficient in protein folding.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work was supported by CSIR [Grant No. 37(1058)/00/EMR-II] and DBT [Grant No. PR1796/BRB/15/178/99], Goverment of India. Help from the distributive information center of this department is acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Das B., Chattopadhyay,S. and DasGupta,C. (1992) Reactivation of denatured fungal glucose-6 phosphate dehydrogenase and E.coli alkaline phosphatase with E.coli ribosome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 183, 774–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bera A.K., Das,B., Chattopadhyay,S. and DasGupta,C. (1994) Refolding of denatured restriction endonucleases with ribosomal preparations from Methanosarcina barkeri. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int., 32, 315–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das B., Chattopadhyay,S., Bera,A.K. and DasGupta,C. (1996) In vitro protein folding by ribosomes from Escherichia coli, wheat germ and rat liver the role 50S particle and its 23S RNA. Eur. J. Biochem., 235, 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chattopadhyay S., Das,B. and DasGupta,C. (1996) Reactivation of denatured proteins by 23S ribosomal RNA: Role of domain V. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 8284–8287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pal D., Chattopadhyay,S., Chandra,S., Sarkar,D., Chakraborty,A. and DasGupta,C. (1997) Reactivation of denatured proteins by domain V of bacterial 23S RNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 5047–5051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chattopadhyay S., Pal,S., Pal,D., Sarkar,D., Chandra,S. and DasGupta,C. (1999) Protein folding in Escherichia coli: role of 23S ribosomal RNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1429, 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kudlichi W., Coffman,A., Kramer,G. and Hardesty,B. (1997) Ribosomes and ribosomal RNAs as chaperone for folding of proteins. Fold. Des., 2, 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argent R.H., Parrott,A.M., Day,P.J., Roberts,L.M., Stockley,P.G., Lord,J.M. and Radford,S.E. (2000) Mar 31, ribosome-mediated folding of partially unfolded ricin A chain. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 9263––9269.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pal S., Chandra,S., Chowdhury,S., Sarkar,D., Ghosh,A.N. and Dasgupta,C. (1999) Complementary role of two fragments of domain V of 23S ribosomal RNA in protein folding. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 32771–32777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovalic D., Giannattasio,R.B. and Weisblum,B. (1995) Methylation of minimalist 23S RNA sequences in vitro by ErmSF (TlrA) N-Methyltransferase. Biochemistry, 34, 15838–15844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barik S. (1995) Site-directed mutagenesis by PCR: substitution, insertion, deletion and gene fusion. Meth. Neurosci., 26, 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chattopadhyay D., Raha,T. and Chattopadhyay,D. (1997) PCR mutagenesis: treatment of megaprimer with Mung Bean Nuclease improves yield. Biotechniques, 22, 1054–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maniatis T., Fritsch,E.F. and Sambrook,J. (1982) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 14.Vester B. and Garrett,R.A. (1988) The importance of highly conserved nucleotides in the binding region of chloramphenicol at the peptidyl transferase centre of Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J., 7, 3577–3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douthwaite S. (1992) Functional interactions within 23S RNA involving the peptidyl transferase centre. J. Bacteriol., 174, 1333–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moazed D. and Noller,H.F. (1989) Interaction of tRNA with 23S rRNA in the ribosomal A, P and E sites. Cell, 57, 585–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Conner M. and Dahlberg,A.E. (1995) The involvement of two distinct regions of 23S ribosomal RNA in tRNA selection. J. Mol. Biol., 254, 838–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Conner M. and Dahlberg,A.E. (1993) Mutations at U2555, a tRNA- protected base in 23S RNA affect translational fidelity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 9214–9218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregory S.T., Lieberman,K.R. and Dahlberg,A.E. (1994) Mutations in the peptidyl transferase region of E.coli 23S rRNA affecting translational accuracy. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 279–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieberman K.R. and Dahlberg,A. (1994) The importance of conserved nucleotides of 23S ribosomal RNA and transfer RNA in ribosome catalyzed peptide bond formation. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 16163–16169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samaha R.R., Green,R. and Noller,H.F. (1995) A base pair between tRNA and 23S rRNA in the peptidyl transferase center of the ribosome. Nature, 377, 309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porse B.T. and Garrett,R.A. (1995) Mapping important nucleotides in peptidyl transferase center of 23S RNA using a random mutagenesis approach. J. Mol. Biol., 249, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spahn C.M.T., Remme,J., Schafer,M.A. and Nierhaus,K.H. (1996) Mutational analysis of two highly conserved UGG sequences of 23S rRNA from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 32849–32856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen L.H., Mauvias,P. and Douthwaite,S. (1999) The macrolide-ketolide antibiotic binding site is formed by structures in domain II and V of 23S ribosomal RNA. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moazed D. and Noller,H.F. (1987) Chloramphenicol, erythromycin, carbomycin and vernamycin B protect overlapping sites in peptidyl transferase region of 23S ribosomal RNA. Biochimie, 69, 879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Connor M., Brunelli,C.A., Firpo,M.A., Gregory,S.T., Lieberman,K.R., Lodmell,J.S., Moine,H., Van,Ryk,D.I. and Dahlberg,A.E. (1995) Genetic probes of ribosomal RNA function. Biochem. Cell Biol., 73, 859–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porse B.T., Thi-Ngoc,H.P. and Garrett,R.A. (1996) The donor substrate site within the peptidyl transferase loop of 23S RNA and its putative interactions with the CCA-end of N-blocked amino acyl-tRNA (Phe). J. Mol. Biol. 264, 472–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noller H.F. (1997) Mutations at nucleotides G2251 and U2585 of 23S RNA perturb the peptidyl transferase center of the ribosome. J. Mol. Biol. 266, 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mankin A.S. and Khaitovich,P. (2000) Reconstitution of the 50S subunit with in vitro-transcribed 23S RNA: a new tool for studying peptidyl transferase. In Garrett,R.A., Douthwaite,S.R., Liljas,A., Matheson,A.T., Moore,P.B. and Noller,H.F. (eds), The Ribosome: Structure, Function, Antibiotics and Cellular Interactions. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 229–293.

- 30.Porse B.T., Kirillov,S.V., Awayez,J.M., Ottenheijm,H.C.J. and Garrett,R.A. (1999) Direct crosslinking of the antitumor antibiotic sparsomycin and its derivatives, to A2602 in the peptidyl transferase centre of 23S- like RNA within ribosome–tRNA complexes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 9003–9008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gregory S.T. and Dahlberg,A.E. (1999) Mutations in the conserved P loop perturb the conformation of two structural elements in the peptidyl transferase center of 23S ribosomal RNA. J. Mol. Biol., 285, 1475–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi K.M. and Brimacombe,R. (1998) The path of the growing peptide chain through the 23S rRNA in 50S ribosomal subunit; a comparative crosslinking study with three different peptide families. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 887–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathews D.H., Burkard,M.E. and Turner,D.H. RNA structure version 3.5, copyright (1996, 1997, 1998, 1999), Isis pharmaceuticals, Inc.

- 34.Mathews D.H., Sabina,J., Zuker,M. and Turner,D.H. (1999) Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol., 288, 911–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]