Abstract

Background

Out‐of‐pocket costs have significant implications for patients with heart failure and should ideally be incorporated into shared decision‐making for clinical care. High out‐of‐pocket cost is one potential reason for the slow uptake of newer guideline‐directed medical therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. This study aims to characterize patient–cardiologist discussions involving out‐of‐pocket costs associated with sacubitril/valsartan during the early postapproval period.

Methods and Results

We conducted content analysis on 222 deidentified transcripts of audio‐recorded outpatient encounters taking place between 2015 and 2018 in which cardiologists (n=16) and their patients discussed whether to initiate, continue, or discontinue sacubitril/valsartan. In the 222 included encounters, 100 (45%) contained discussions about cost. Cost was discussed in a variety of contexts: when sacubitril/valsartan was initiated, not initiated, continued, and discontinued. Of the 97 cost conversations analyzed, the majority involved isolated discussions about insurance coverage (64/97 encounters; 66%) and few addressed specific out‐of‐pocket costs or affordability (28/97 encounters; 29%). Discussion of free samples of sacubitril/valsartan was common (52/97 encounters; 54%), often with no discussion of a longer‐term plan for addressing cost.

Conclusions

Although cost conversations were somewhat common in patient–cardiologist encounters in which sacubitril/valsartan was discussed, these conversations were generally superficial, rarely addressing affordability or cost‐value judgments. Cardiologists frequently provided patients with a course of free sacubitril/valsartan samples without a plan to address the cost after the samples ran out.

Keywords: heart failure, sacubitril/valsartan, shared decision‐making

Subject Categories: Heart Failure, Health Services, Quality and Outcomes

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- HFrEF

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

During the clinical encounter, cost discussions regarding sacubitril/valsartan rarely addressed affordability or cost‐value judgments.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Free samples of sacubitril/valsartan were used without a plan to address the medications' cost after the samples ran out, which risks downstream financial toxicity or nonadherence due to unaffordability.

The lack of substantive cost discussions in our study is significant, particularly in the population with heart failure, a group of patients who are known to face significant financial hardship from medical bills.

Guideline‐directed medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) has shifted from a set of inexpensive, generic medications to involve newer, more costly options. In particular, sacubitril/valsartan and sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors significantly reduce hospitalizations and mortality. These medications remain relatively underused. 1 , 2 Some underuse likely represents therapeutic inertia, but out‐of‐pocket costs may also play an important role. For instance, Medicare Part D beneficiaries pay $1400 more per year for sacubitril/valsartan compared with valsartan. 3 Even though sacubitril/valsartan has proven to be cost‐effective to the health care system, 4 it may not be affordable to many patients. In addition, patients face similar out‐of‐pocket costs for sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. 5 Other drugs, such as vericiguat and ivabradine, also have high out‐of‐pocket costs but provide less substantial benefits.

In the context of this changing landscape of HFrEF therapy, integration of out‐of‐pocket costs into shared decision‐making discussions is important. 6 Shared decision‐making has been widely endorsed, but shared decision‐making models often ignore out‐of‐pocket cost considerations. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 High out‐of‐pocket costs affect many aspects of patient health 15 , 16 , 17 and have particularly deleterious effects for low‐income patients, for whom financial burden and cost‐related nonadherence may be the greatest. 12 Moreover, patients with HFrEF generally consider costs to be relevant to decision‐making and are receptive to their inclusion in discussions and decisions. 18 , 19 The extent to which this information is a part of real‐world HFrEF treatment discussions and shared decision‐making with patients is unknown.

Audio‐recorded patient–cardiologist encounters related to sacubitril/valsartan present an opportunity to understand the landscape of out‐of‐pocket cost discussions in encounters with patients with HFrEF. This information may help identify ways to make this process more effective and more patient‐centered.

Methods

Sample Description and Exclusion Criteria

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. We analyzed transcripts of audio‐recorded outpatient encounters that occurred between June 1, 2015, and December 3, 2018, between community cardiologists and patients with HFrEF. The data were provided by Verilogue Inc., which has a pooled database of recorded patient–physician encounters from diverse specialties across the United States that have been used in health services and market research. 20 Participating physicians agree to have visits recorded and are not informed about the purpose of recording visits in order to reduce potential bias. They are reimbursed for recorded encounters, and consent to audio recording is obtained from patients before the start of each clinician encounter. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are also included. Recorded encounters are then transcribed and deidentified.

For this study, encounters within the pooled database were included if they involved patients with a diagnosis of HFrEF and if the transcripts contained the words “sacubitril/valsartan” or “Entresto.” Encounters were subsequently excluded from analysis if the recording was incomplete (18), or if sacubitril/valsartan was mentioned only as a part of medication reconciliation but not discussed (88). Only 1 visit per patient was included. The study was considered by Duke University to be exempt from institutional review board review.

Content/Statistical Analysis

We based our analysis on a coding scheme previously developed to describe themes pertaining to cost discussions between clinicians and patients. 21 This scheme was used to identify cost discussions, characterize the content of these discussions, and identify whether clinicians described potential cost‐saving strategies to patients. We adapted that scheme to characterize when and how sacubitril/valsartan's clinical benefits were discussed, to identify and classify types of cost conversations, and to determine a decisional outcome (ie, whether the drug was initiated, not initiated, continued, or discontinued). Importantly, each recorded encounter occurred with a unique patient in a single visit as opposed to a longitudinal assessment.

All encounter transcripts were independently double‐coded by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, students, epidemiologists, and behavioral scientists to reduce coder bias and improve accuracy. Intercoder discrepancies were resolved through team consensus to ensure proper interpretation of clinical matters. All coding was conducted using NVivo software, version 10.

Results

Study Participant Characteristics

Our final analysis included 222 outpatient encounters with 222 distinct patients (Table 1) with a diagnosis of HFrEF. Most patients were White (71%), male (74%), and between the ages of 60 to 69 (27%) or 70 to 79 (30%). Patients had either public (74%) or private (25%) insurance; a small minority were uninsured (1%). A total of 16 cardiologists (Table 1) were included; all were male (100%), and half were located in the northeast (50%). Many had been in practice between 21 and 30 years (46%). The primary practice location was either group private practice (62%) or solo private practice (38%). Data on cardiologist race were not available.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients and Cardiologists

| Patient and cardiologist characteristics | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | No. 220* | % |

| Age, y | ||

| 30–39 | 1 | <1 |

| 40–49 | 14 | 6 |

| 50–59 | 33 | 15 |

| 60–69 | 60 | 27 |

| 70–79 | 65 | 30 |

| 80–89 | 37 | 17 |

| 90+ | 10 | 5 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 57 | 26 |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| White | 157 | 71 |

| Black | 38 | 17 |

| Hispanic | 20 | 9 |

| Asian | 5 | 2 |

| Primary insurance | ||

| Private | 55 | 25 |

| Public | 162 | 74 |

| Uninsured/not sure | 3 | 1 |

| Cardiologist characteristics | No. (16) | % |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 0 | 0 |

| Years in practice | ||

| 11–20 y | 4 | 27 |

| 21–30 y | 7 | 46 |

| 31+ y | 4 | 27 |

| Region of practice | ||

| Southeast | 3 | 19 |

| Northeast | 8 | 50 |

| Midwest | 2 | 12 |

| West | 3 | 19 |

Two encounters lacked patient demographic information.

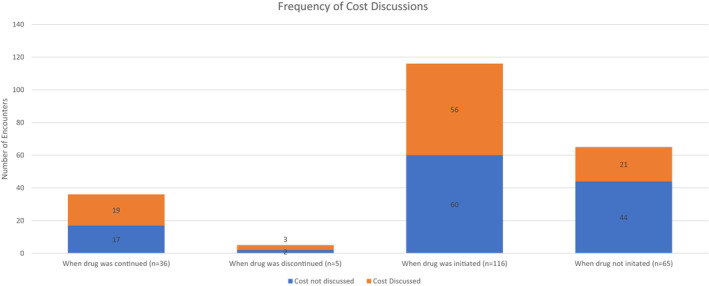

Incidence of Cost Conversations

Across 222 encounters, the cost of the drug was discussed in 100. The frequency of discussing cost in patient encounters varied across the 16 cardiologists, ranging from 5 out of 41 encounters (Dr 16) to 5 out of 5 encounters (Dr 5) (Figure 1). The majority of cost discussions were initiated by cardiologists (75 out of 100; 75%) rather than by patients (Figure 1). Of the recorded encounters, drug initiation occurred in 116 (52%), and discussion without initiation occurred in 65 (29%). In encounters where the patient was already taking the drug at the time of the encounter, continuation occurred in 36 (16%), and discontinuation occurred in 5 (2%). (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Frequency of cost discussions in total number of patient encounters across cardiologists.

Figure 2. Frequency of cost discussions across sacubitril/valsartan decisional outcomes.

The cost of sacubitril/valsartan was discussed across a diverse set of encounters, including those that involved initiation, discontinuation, continuation, and noninitiation of the drug. Cost was discussed relatively more frequently when sacubitril/valsartan was discontinued (3 out of 5 encounters; 60%), continued (20 out of 36 encounters; 56%), and initiated (56 out of 116 encounters; 48%) compared with when deciding against initiating sacubitril/valsartan (21 out of 65 encounters; 32%) (Figure 2).

Types of Sacubitril/Valsartan Cost Conversations

Isolated Discussion of Sacubitril/Valsartan Insurance Coverage or Approval Process

Discussions involving drug costs most often focused on the insurance coverage or approval process. Of the 100 encounters where cost was discussed, 64 discussions (64%) were limited to the presence or absence of insurance coverage or the insurance approval process; these conversations did not address the drug's out‐of‐pocket cost or affordability. Thirty‐eight of these discussions were visits where sacubitril/valsartan was initiated. For example, in 1 encounter, after learning from the patient that their insurance provider had changed from “BlueShield” to “HealthNet,” the doctor commented “okay…I'll try to get this drug covered” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ways of Discussing Cost Across Different Sacubitril/Valsartan Decisional Outcomes*

| Example | |

|---|---|

| Isolated discussion of insurance coverage or approval process (n=64) |

Doctor: “Okay. Now, we talked about this new medication called Entresto? That was very expensive. So…your insurance is actually quite good. It's Blue Shield?” Patient: “No, I got a new one” Doctor: “Oh…What is it?” Patient: “HealthNet…I have a silver plan” Doctor: “Okay…I'll try to get this drug covered” |

| Out‐of‐pocket cost discussion (n=5) |

Doctor: “It's probably a couple of hundred dollars a month if you had to pay at cost, but your insurance should cover it” Patient: “Yeah” |

| Affordability discussion (n=28) | Doctor: “If you do very well, maybe, but price it out. If you think it's something you could afford, Entresto…check with the pharmacy what it's going to cost you before I give it to you” |

Three transcripts were excluded because of the nonspecific nature of cost discussion.

Discussion of Sacubitril/Valsartan's Out‐of‐Pocket Cost

Specific out‐of‐pocket costs were mentioned in only 5 encounters. For example, in one encounter, the patient acknowledged that the cost is “not bad” after the cardiologist commented that at most, sacubitril/valsartan should cost the patient “$6.00 a month” (Table 2). Other encounters, particularly when the drug was not initiated or was discontinued, only had vague discussions of out‐of‐pocket costs and rarely included the exact cost the patient might expect to pay for the drug.

Out‐of‐pocket costs, when discussed, were rarely contextualized in terms of the drug's benefits. Among the 5 encounters in which patients decided to stop taking sacubitril/valsartan, 3 (60%) involved a discussion of cost. Unsustainable out‐of‐pocket cost served as the sole reason evident within these encounters for termination of sacubitril/valsartan after prior initiation. For example, in 1 encounter, the doctor commented that “we stopped that [sacubitril/valsartan]” because “it was very expensive.” In all 3 of these encounters, aspects of affordability were discussed between the patient and cardiologist.

Discussion of Sacubitril/Valsartan's Affordability

Cost discussions involving the affordability of sacubitril/valsartan were generally vague and occurred in 28 of the 100 encounters. Seventeen of these encounters (60%) specifically addressed the affordability of sacubitril/valsartan. In the other 11 encounters (39%), the affordability of the drug was briefly mentioned, but ultimately, the clinician recommended that patients determine the affordability themselves when filling the prescriptions at the pharmacy. Sometimes, a different drug was referenced by the cardiologist as a way for patients to estimate the affordability of sacubitril/valsartan. For example, in 1 encounter the cardiologist asked whether the patient's copay for Spiriva, another “brand name medicine,” is “tolerable” because sacubitril/valsartan “will probably be like Spiriva.”

Use of Free Samples in Sacubitril/Valsartan Discussions

Free samples of sacubitril/valsartan were discussed by cardiologists in 97 encounters. Overall, in encounters where samples were mentioned, cost discussions were more frequent (52 of the 97 encounters; 54%) compared with encounters where samples were not mentioned (48 of the 125 encounters; 38%). When samples were mentioned and the drug was being initiated, cost discussions occurred in 33 of the 70 encounters (47%). On the other hand, cost discussions were more common when samples were mentioned, and the drug was continued (15 of the 19 encounters; 79%) or when samples were mentioned, and the drug was not initiated (4 out of 8 encounters; 50%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Incidence of free sacubitril/valsartan sample use in encounters with and without mention of cost.

*Samples were not given/discussed in encounters where sacubitril/valsartan was discontinued.

Cost discussions were more common when samples were mentioned in the context of drug continuation than in the context of drug initiation. In both types of encounters, however, there were no discussions about long‐term planning for sacubitril/valsartan if the drug was not affordable. During the encounters where sacubitril/valsartan was initiated and cost was not discussed, free samples were proposed by cardiologists to assess the patient's ability to medically tolerate the drug. When the drug was continued and cost was discussed, sample use was suggested to address cost issues often related to insurance coverage. Interestingly, when samples were mentioned but not used (in 4 encounters), sacubitril/valsartan was not initiated owing to underlying uncertainty regarding cost of the medication. For instance, 1 patient responded saying he was “not too keen on it right now” after the doctor was unable to provide an estimate of the drug's out‐of‐pocket cost. The doctor encouraged the patient to “figure out the finances of it” before starting on samples.

Discussion

Overall, sacubitril/valsartan cost discussions were observed in 45% of encounters (100 out of 220) between patients and cardiologists; however, cost discussions were generally superficial. Most were limited to the insurance coverage approval process. Only a minority of conversations directly explored patients' specific out‐of‐pocket costs or assessed whether patients could afford the medicine, both of which are necessary for cost‐sensitive shared decision‐making. Our data are consistent with other studies, where recorded clinic visits demonstrate cost discussions are not the norm and are often ineffective in patients with cancer, depression, and rheumatologic disease. 22 The lack of substantive cost discussions in our study is significant, particularly in the population with heart failure, a group of patients who are known to face significant financial hardship from medical bills. 23

In addition to the narrow focus on insurance coverage, relatively few cost discussions mentioned the drug's benefits in a way that allowed the patient to make informed cost‐value judgments about the medication. Limiting cost discussions to insurance coverage alone does not help patients make cost‐value judgments. The annual cost of contemporary medical therapy for Medicare patients with HFrEF is on average $2217, which is unaffordable for many patients; conversely, the traditional regimen for HFrEF (beta‐blocker, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist) costs only $159 annually for Medicare recipients. 24 Weighing the relative cost of contemporary quadruple therapy for HFrEF against the relative benefit of that regimen compared with the traditional regimen is complex.

Discussion cost in the context of guideline‐directed medical therapy for heart failure can be challenging. To facilitate these discussions, clinicians and patients will both need accurate out‐of‐pocket estimates during the clinical encounter. This information was generally unavailable until the patient fills the prescription at the pharmacy, but recent pushes for greater price transparency may now make cost information more widely available. For instance, many electronic medical records now use patient insurance information to provide the clinician an estimate for out‐of‐pocket costs when ordering the medication. Even if this cost information is available, some clinicians may be uncomfortable discussing affordability with patients; however, patients with HFrEF are largely open to discussing costs with their clinician. 25 Acknowledging the cost of medical therapy is an important first step and can open the door to more substantive discussions related to value. However, the more complex task is to understand how to conduct shared decision‐making discussions of out‐of‐pocket costs in the context of the benefits of medical therapy in order to help patients make the best decisions for themselves.

One interesting finding in our study was the high use of free sacubitril/valsartan samples in encounters when continuing and initiating the drug, irrespective of whether the long‐term cost of the drug was discussed. Prior research suggests that free samples are used to ease out‐of‐pocket costs for patients, especially those who have low incomes or are uninsured. 26 Samples may also be particularly useful during a trial period to ensure that a patient tolerates a drug before purchasing it or while a prior authorization is being processed. However, free drug samples do not make out‐of‐pocket costs irrelevant. Free sample use should be accompanied by a long‐term plan for dealing with out‐of‐pocket costs when the samples run out. Otherwise, there is a downstream risk of financial toxicity or nonadherence due to unaffordability.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first characterization of real‐world cost discussion in clinical encounters for HFrEF; however, this study does have limitations. First, the Verilogue database may be subject to selection bias. There was an absence of diversity in sex and race on the part of patients, and cardiologists were generally older and in private practice. Second, we had access to only 1 visit per patient and were unable to determine how cost conversations evolved over multiple encounters. Third, many of these conversations focused on prior authorization for sacubitril/valsartan given these encounters occurred before 2018. Though prior authorizations requirements for this drug have diminished, they continue to be relevant as other newer HFrEF drugs become available. In addition, future studies could address how availability of accurate cost information during the clinical encounter alters cost–benefit discussions between patients and cardiologists.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings suggest that discussions involving sacubitril/valsartan's out‐of‐pocket cost are often vague and do not provide patients with adequate information to make a meaningful assessment of tradeoffs. In addition, they suggest a potentially problematic trend of using samples without a financial plan. In all of these respects, these data suggest that patients and clinicians do not frequently engage in meaningful cost‐sensitive decision‐making regarding sacubitril/valsartan. Though this analysis is focused on sacubitril/valsartan, the implications are particularly salient given novel therapeutic advances in the treatment of HFrEF. 24

Sources of Funding

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant # 1R01HS026081‐01.

Disclosures

Birju R. Rao reports funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and National Institutes of Health. Neal W. Dickert reports receiving research funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Greenwall Foundation. The other authors report no conflicts.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 7.

References

- 1. Sangaralingham LR, Sangaralingham SJ, Shah ND, Yao X, Dunlay SM. Adoption of sacubitril/valsartan for the management of patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11:e004302. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Luo N, Fonarow GC, Lippmann SJ, Mi X, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, Greiner MA, Hammill BG, Hardy NC, Turner SJ, et al. Early adoption of sacubitril/valsartan for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from Get With the Guidelines‐Heart Failure (GWTG‐HF). JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeJong C, Kazi DS, Dudley RA, Chen R, Tseng CW. Assessment of national coverage and out‐of‐pocket costs for sacubitril/valsartan under Medicare part D. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:828–830. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. King JB, Shah RU, Bress AP, Nelson RE, Bellows BK. Cost‐effectiveness of sacubitril‐valsartan combination therapy compared with enalapril for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC: Heart Failure. 2016;4:392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeJong C, Masuda C, Chen R, Kazi DS, Dudley RA, Tseng CW. Out‐of‐pocket costs for novel guideline‐directed diabetes therapies under Medicare part D. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1696–1699. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Backman WD, Levine SA, Wenger NK, Harold JG. Shared decision‐making for older adults with cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43:196–204. doi: 10.1002/clc.23267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drozda JP Jr, Ferguson TB Jr, Jneid H, Krumholz HM, Nallamothu BK, Olin JW, Ting HH. 2015 ACC/AHA focused update of secondary prevention lipid performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:558–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP III, Fleisher LA, Jneid H, Mack MJ, McLeod CJ, O'Gara PT, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e1159–e1195. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Tseng CW, McFadden D, Meltzer DO. Barriers to patient‐physician communication about out‐of‐pocket costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:856–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30249.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Piette JD, Heisler M, Wagner TH. Cost‐related medication underuse: do patients with chronic illnesses tell their doctors? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1749–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tseng CW, Dudley RA, Brook RH, Keeler E, Steers WN, Alexander GC, Waitzfelder BE, Mangione CM. Elderly patients' preferences and experiences with providers in managing their drug costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1974–1980. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01445.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure–out‐of‐pocket costs as side effects. N Eng J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1306826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Meltzer DO. Patient‐physician communication about out‐of‐pocket costs. JAMA. 2003;290:953–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tseng CW, Waitzfelder BE, Tierney EF, Gerzoff RB, Marrero DG, Piette JD, Karter AJ, Curb JD, Chung R, Mangione CM, et al. Patients' willingness to discuss trade‐offs to lower their out‐of‐pocket drug costs. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1502–1504. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steinman MA, Sands LP, Covinsky KE. Self‐restriction of medications due to cost in seniors without prescription coverage. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:793–799. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.10412.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rector TS. Exhaustion of drug benefits and disenrollment of Medicare beneficiaries from managed care organizations. JAMA. 2000;283:2163–2167. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.16.2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Federman AD, Adams AS, Ross‐Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Ayanian JZ. Supplemental insurance and use of effective cardiovascular drugs among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2001;286:1732–1739. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dickert NW, Mitchell AR, Venechuk GE, Matlock DD, Moore MA, Morris AA, Pierce KJ, Speight CD, Allen LA. Show me the money: patients' perspectives on a decision aid for sacubitril/valsartan addressing out‐of‐pocket cost. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e007070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Venechuk GE, Allen LA, Doermann Byrd K, Dickert N, Matlock DD. Conflicting perspectives on the value of neprilysin inhibition in heart failure revealed during development of a decision aid focusing on patient costs for sacubitril/valsartan. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e006255. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rothberg MB, Sivalingam SK, Kleppel R, Schweiger M, Hu B, Sepucha KR. Informed decision making for percutaneous coronary intervention for stable coronary disease. JAMA Inter Med. 2015;175:1199–1206. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hunter WG, Zhang CZ, Hesson A, Davis JK, Kirby C, Williamson LD, Barnett JA, Ubel PA. What strategies do physicians and patients discuss to reduce out‐of‐pocket costs? Analysis of cost‐saving strategies in 1,755 outpatient clinic visits. Med Decis Making. 2016;36:900–910. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15626384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ubel PA, Zhang CJ, Hesson A, Davis JK, Kirby C, Barnett J, Hunter WG. Study of physician and patient communication identifies missed opportunities to help reduce patients' out‐of‐pocket spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:654–661. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ali HR, Valero‐Elizondo J, Wang SY, et al. Subjective financial hardship due to medical bills among patients with heart failure in the United States: the 2014‐2018 medical expenditure panel survey. J Card Fail. 2022;28:1424–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Faridi KF, Dayoub EJ, Ross JS, Dhruva SS, Ahmad T, Desai NR. Medicare coverage and out‐of‐pocket costs of quadruple drug therapy for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:2516–2525. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rao BR, Dickert NW, Morris AA, Speight CD, Smith GH, Shore S, Moore MA. Heart failure and shared decision‐making: patients open to medication‐related cost discussions. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13:e007094. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chew LD, O'Young TS, Hazlet TK, Bradley KA, Maynard C, Lessler DS. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians' behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:478–483. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08014.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]