ABSTRACT

The American Heart Association's Strategically Focused Children's Research Network started in July 2017 with 4 unique programs at Children's National Hospital in Washington, DC; Duke University in Durham, North Carolina; University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah; and Lurie Children's Hospital/Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois. The overarching goal of the Children's National center was to develop evidence‐based strategies to strengthen the health system response to rheumatic heart disease through synergistic basic, clinical, and population science research. The overall goals of the Duke center were to determine risk factors for obesity and response to treatment including those that might work on a larger scale in communities across the country. The integrating theme of the Utah center focused on leveraging big data‐science approaches to improve the quality of care and outcomes for children with congenital heart defects, within the context of the patient and their family. The overarching hypothesis of the Northwestern center is that the early course of change in cardiovascular health, from birth onward, reflects factors that result in either subsequent development of cardiovascular risk or preservation of lifetime favorable cardiovascular health. All 4 centers exceeded the original goals of research productivity, fellow training, and collaboration. This article describes details of these accomplishments and highlights challenges, especially around the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Keywords: childhood and adolescent obesity, congenital heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, trajectories of cardiovascular health

Subject Categories: Genetics, Epigenetics

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ARF

acute rheumatic fever

- CVH

cardiovascular health

- RHD

rheumatic heart disease

- SFRN

Strategically Focused Research Network

The American Heart Association (AHA) was founded in the 1920s, in large part to fight the most significant childhood heart condition of the era, rheumatic heart disease (RHD). The AHA Council on Rheumatic Fever was established in 1944 to focus on research and education and was chaired for several years by T. Duckett Jones. In 1950 the council expanded its name to include congenital heart disease (CHD) and in 1952 the council appointed its first pediatrician, Helen Taussig, to the executive committee. In 1973 the council changed its name to “Cardiovascular Disease in the Young” and included the Committee of Atherosclerosis and Hypertension. Nearly a century after AHA began and half a century after commissioning of Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Children's Strategically Focused Research Network (SFRN) was established to apply state‐of‐the‐art basic, clinical, and population science strategies and train the next generation of pediatric cardiology scientists while still embodying Cardiovascular Disease in the Young's original focus on RHD, CHD, and preventive cardiology. The Children's SFRN directly and proudly builds on work done by the early pioneers in of pediatric cardiovascular science within AHA in the 1940s and 1950s.This article highlights the hypotheses, goals, accomplishments, challenges, and future directions of each center; provides an overview of collaboration efforts (Table 1) 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 and trainee accomplishments (Table 2) 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ; and summarizes how we can leverage the output of this SFRN to advance pediatric cardiovascular science.

Table 1.

Collaboration

| Title/Description | Lead | Participating centers | PIs and lead fellows |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ad hoc working groups were established with the members of the Children's and Go Red for Women SFRN networks interested in maternal health, specifically related to the role of the placenta | Utah | Northwestern, Magee Women's Institute | PIs: Tristani‐Firouzi, Silver, Allen, Catov |

| Focus groups for families pursuing surgery, termination of pregnancy, or palliative care within a fetal congenital heart disease population 2 , 3 , 4 | Utah | Duke, Northwestern, Children's National |

PIs: Fagerlin, Miller, Marino, Donofrio Fellow, Delaney |

| Cardiovascular risk phenoclusters of children with obesity. These findings will then be applied to the sample of children used in the basic science and clinical projects to examine the relationships between omics, behavioral factors, and the cardiovascular risk phenoclusters. | Duke | Duke, Northwestern | PIs: Shah, Skinner, Fellow Marma |

| Metabolomic and lipidomic indicators of cardiovascular health in youth | Duke | Northwestern | PI's: Shah, Marma |

|

Rheumatic heart disease in the United States: forgotten but not gone Results of a 10‐year multicenter review 1 |

Children's National Cincinnati Children's |

Children's National, Duke, Northwestern, 20 additional institutions |

PIs: Sable, Beaton, Fellow DeLoizaa‐Carney (Fellow in Tech SFRN) |

| Maternal health and epigenetics | Northwestern | University of Pittsburgh | PI: Hou |

PI indicates principal investigator; and SFRN, Strategically Focused Research Network.

Table 2.

Trainee Accomplishments

| Center | Name, publications | AHA SFRN fellow project | Other | Position after AHA SFRN fellowship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utah | Sergiusz Wesolowski. 16 , 28 | Basic: artificial intelligence tools, data science | Data scientist, Recursion Pharmaceuticals | |

| Utah | Derek Weyhrauch 28 , 33 | Clinical: placental transcriptomics | Assistant professor, Cincinnati Children's Heart Institute | |

| Utah | Rebecca Delaney 2 , 3 , 4 , 28 | Population: shared decision making | Research assistant professor, Population Health Sciences, University of Utah | |

| Utah | Alistair Thorpe 3 , 32 | Population: decision aid, values clarification | Postdoctoral fellow, Population Health Sciences, University of Utah | |

| Duke | McAllister Windom, MD 28 , 37 | Clinical: hearts & parks | Faculty: clinical associate, Duke | |

| Duke | Nathan Bihlmeyer, PhD 28 , 29 , 30 | Basic: metabolomic profiles in obesity | Postdoctoral fellow, Duke | |

| Duke | Cody Neshteruk, PhD 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 | Population: behavioral interventions and physical activity measurement in childhood obesity. | Faculty: medical instructor of population health, Duke | |

| Children's National | Meghan Zimmerman, MD, MPH 1 , 8 , 20 , 21 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 43 |

Clinical: incidence of ARF Clinical: RHD follow‐up |

Full MPH | Faculty: Dartmouth |

| Children's National | Emma Ndagire, MBChS 8 |

Clinical: ARF diagnosis Population: RHD readiness |

MPH certificate | Faculty: Uganda Heart Institute |

| Children's National | Babu Muhamed, PhD, MPH 1 , 7 , 21 , 24 , 25 |

Basic: immune response to Group A Streptococcus Clinical: RHD in USA |

Full MPH | Postdoctorate: University of Tennessee |

| Northwestern | Brian Joyce, PhD 13 | Basic: epigenetic biomarkers of health‐related environmental exposures and behaviors | Research assistant professor, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine | |

| Northwestern | Population: early life origins of racial and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. | Research assistant professor, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University | ||

| Northwestern | Orna Reges, PhD 23 | Clinical: association of cumulative systolic blood pressure with long‐term risk of cardiovascular disease and healthy longevity | Senior lecturer, Ariel University, Israel |

AHA indicates American Heart Association; ARF, acute rhematic fever; MPH, master's of public health; RHD, rheumatic heart disease; and SFRN, Strategically Focused Research Network.

Children's National Hospital

Center Hypotheses and Goals

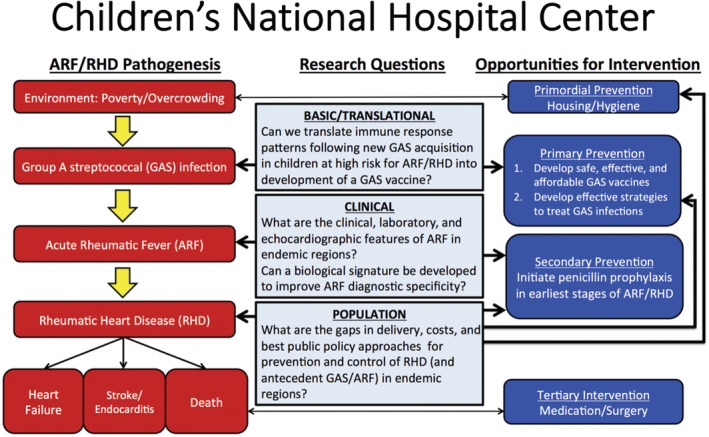

RHD remains a significant contributor to the global burden of cardiac disease with a worldwide prevalence of 40.5 million people; RHD is responsible for over 300 000 deaths and over 10 million disability‐adjusted life years lost each year. 34 It is a disease of poor and disadvantaged people and those who lack regular access to both preventive care and advanced cardiac care. 35 , 36 Prevention and early detection of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and RHD before progression to moderate to severe valvular changes is high priority for reducing the global burden of RHD. 37 , 38 The overarching goal of our center is to develop evidence‐based strategies to strengthen the health system response to RHD through synergistic basic, clinical, and population science research (Figure 1). Our 3 projects are intricately woven together under 1 unifying aim: improving the diagnosis and prevention of ARF and RHD around the globe. Our center brings a synergistic approach to closing this knowledge gap both from the rationale and operational standpoints and has a strong focus on developing strategies that are rapidly translatable to public health policy and solutions that can dramatically reduce the burden of RHD. The 4 specific goals that track with each of our projects are to (1) make critical advancements in the science needed for the development of a safe, effective group A streptoccal vaccine through study of the immune response to group A Streptococcus infection; (2) characterize the pattern of contemporary and endemic ARF; (3) develop a biological signature to improve sensitivity and specificity of ARF diagnosis; and (4) identify health‐system shortfalls and develop a “costed” action plan to incite meaningful policy change.

Figure 1. Pathogenesis, research questions, and opportunities for intervention for the Children's national rheumatic heart disease prevention SFRN Center.

ARF indicates acute rheumatic fever; GAS, Group A Streptococcus; and RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Successes and Challenges

ARF and RHD are potentially “vaccine preventable” diseases. The goal of the basic science project was to study the immune responses of children before and after strep throat infections to ultimately inform vaccine development. Our recruitment of 256 participants from Cape Town, South Africa, together with subsequent follow‐up investigations, provided a total of 864 throat swabs and serum samples for analysis. From 42 subjects with positive group A Streptococcuscultures, ≈202 serum samples were subjected to ELISA analysis of the full set (35 antigens) of antibody assays (7070 assays). ELISAs performed in Memphis and Cape Town revealed concordant results that served to validate the assays for each group A Streptococcusantigen. Criteria were established for new antibody responses and high levels of preexisting antibodies against specific antigens using standard titration curves of antibodies present in commercial intravenous immunoglobulin against each antigen. Ongoing and soon to be completed analyses hold promise for a statistical association of immunity to one or more shared StreptococcusA antigens with protection against immunologically significant new acquisitions on StreptococcusA. This information may inform the design of broadly protective vaccines designed to prevent the StreptococcusA infections that trigger ARF. Our clinical project examined why ARF diagnosis was low in endemic settings despite high rates of RHD. We established ARF surveillance sites in Lira and Mbarara districts in Uganda that included widespread community and health care provider education and establishing the infrastructure to diagnose ARF. As a result, 1075 children presented and 691 met inclusion criteria and were enrolled. Our work provides some of the first detailed descriptions of ARF in sub‐Saharan Africa. The results confirm that ARF is common among our study population in Uganda. 20 , 21 Our study also found that ARF resembles many other diseases, which can lead to misdiagnosis or a lack of health‐seeking behavior. We also evaluated the health system's ability to diagnosis and treat ARF. We found that only tier 3 centers can adequately diagnosis ARF based on Jones Criteria. 39 Finally, in partnership with Telethon Kids Institute in Australia we collected blood to identify biomarkers of ARF. The Somalogic proteomics data has been the most promising, allowing us to reliably distinguish definite ARF from alternate diagnoses and healthy controls with just over 20 down‐selected proteins. The article is being drafted. The population project focused on defining gaps and determining costs for RHD care delivery in Uganda and providing data to support government investment. We surveyed ≈400 health facilities, interviewed people living with RHD and health workers, and conducted community focus groups. We also had a series of in‐patient meetings with the Ugandan Ministry of Health, most recently in August 2022. This work has resulted in 4 published articles 22 , 40 , 41 , 42 ; another article is under review, and 2 more are in the advanced stages of preparation. We also plan to prepare a policy brief to synthesize all the key findings that will be tailored to policy makers in African countries facing challenges similar to those in Uganda. The COVID‐19 pandemic affected all of our projects, resulting in delays in recruitment and transfer of blood samples as well as limiting in‐person fellow education. However, all of the milestones of the RHD center were still achieved and we leveraged virtual technology to ensure fellow education was not compromised.

One of the unique challenges and successes of our RHD center was to advance a culture and infrastructure of conducting clinical research in low‐income countries to assure benefit to the most vulnerable populations. This was done by conducting focus groups that included study participants to help design the studies before carrying them out, using strict local ethics reviews and medical counsels that included appropriate support and reimbursement for patients and families and translation of consent/assent into local languages, and relying on local nonphysician health workers to work directly with patients and families.

Future Directions for the Center

The gravitas of the AHA investment in control of RHD holds promise for advancing efforts at reduction of the global disease burden in the next decade. The investigators and output of this center have made considerable contributions to ARF and RHD research and policy. A second AHA SFRN center (2021–2024) focused on RHD is included in the Technology Network (A. Beaton, center director; C. Sable and D. Watkins, coinvestigators) Data from the clinical project formed the basis of a successful multinational biomarkers project (A. Beaton, principal investigator, and C. Sable, coinvestigator) to start in 2023 (Leducq Foundation). Data from the population project informed a highly scored R01 application (A. Beaton, principal investigator; C. Sable and D. Watkins, coinvestigators, second percentile, final funding announcement pending) focused on implementation of an RHD control program in 2 districts in northern Uganda that will likely start in early 2023. In addition to ongoing funded research that has specifically resulted from the Children's RHD center, investigators have had leadership roles in companion AHA Scientific and Advocacy Statements 43 , 44 as well as a National Institutes of Health working group focused on prioritizing funding for RHD research. The 71st World Health Organization Assembly adopted a resolution on RHD in June 2018. Representatives of 26 member states and 6 nongovernmental organizations including the AHA spoke in support of the resolution, recognizing that RHD remains a significant public health concern in many countries. Our center team continues to play a major role in advancing the directives of this resolution around the globe.

Duke University

Center Hypotheses and Goals

In 2018, 14.7 million (or 1:5) children aged 2 to 19 had obesity, and the rate of body mass index (BMI) increase among children has nearly doubled over the past 2 years during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 12 , 15 If not effectively treated, childhood obesity is associated with an 80% increased risk of persistent obesity into adulthood and a 5‐fold increased risk of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Lifestyle interventions are the cornerstone of all childhood obesity treatments. 26 To be effective, they must include nutrition and activity counseling inclusive of the child's family and delivered face to face for at least 26 hours over a 6‐ to 12‐month period. 11 Children receiving this high‐intensity lifestyle treatment demonstrate reductions in BMI and improvement in comorbidities, health behaviors, and quality of life.

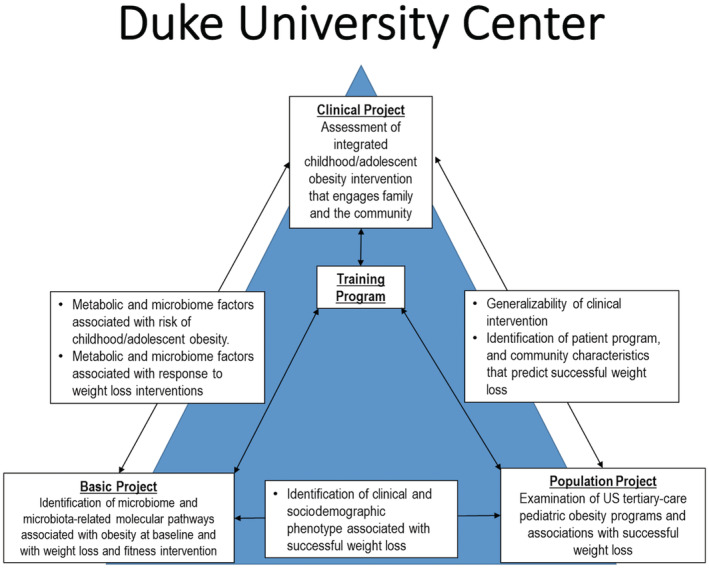

We developed and tested a model of childhood obesity treatment pairing health care organizations with local parks and recreation departments to deliver intensive lifestyle treatment. Health care providers screen for obesity, provide counseling, and treat comorbidities; recreation centers provide intensive health behavior and lifestyle treatment in the community. Our clinical project performed a randomized controlled trial to measure effectiveness of clinic‐community intervention on BMI reduction and fitness among children with obesity aged 5 to 17. The population project described patient, family, and program components as well as types of weight loss intervention components used, retention rates, and trajectories of weight loss in other pediatric weight loss programs. The basic program assessed whether branched chain amino acids and the fecal microbiome were associated with obesity phenotypes and whether they changed in response to intervention. Our overall goals were to determine how those differences might influence the risk of obesity and response to treatment including those that might work on a larger scale in communities across the country (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Synergy among the basic, clinical, and population projects in Duke SFRN Center.

Successes and Challenges

Successes

Throughout the grant period we had many successes and challenges. The successes of the Duke Center predominantly arose from existing and close collaborations of the investigators within 2 existing Duke programs called Bull City Fit and Healthy Lifestyles, which the health system has offered since 2012. These programs combine regular exercise, nutrition classes, family involvement, and monthly medical evaluations. Project focus and group structure, multiple regularly occurring cross‐project group meetings, and shared resources (ie, biobanks and clinical research support teams), and complementary cross‐disciplinary areas of expertise helped accelerate the projects. We successfully trained 3 fellows who all have obtained full‐time positions and subsequently secured their own grant funding for research after their AHA training period. Through innovative study designs on the clinical project, we successfully recruited and implemented an intervention in a population that is well documented as being difficult to reach and retain. The clinical project randomized 255 patients (36% Black and 43% Hispanic) ages 5 to 17 years. Participants assigned to the intervention arm were enrolled in the clinic‐community intervention for 6 months, and those assigned to the comparison group received a nonobesity‐related literacy intervention for 6 months and then were enrolled in the clinic‐community intervention for an additional 6 months. Participants initially randomized to intervention continue in the intervention for the full 12 months of the study (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03339440). Although final trial results are yet to be published, we used innovative study designs and implementation methods to successfully recruit and randomize the study population. Some of the trial innovations included (1) notification to primary care providers of patient eligibility in electronic health records (EHRs); (2) remote consent; (3) virtual visits; (4) virtual exercise sessions, and (5) implementation of wearable fitness devices. Through the use of these measures, we were able to transition an in‐person intervention to a remote‐based enrollment and intervention effort after the COVID‐19 pandemic forced all clinical research operations to cease in‐person and on‐site activities. In our basic science project, we found novel, biologically plausible proteins associated with obesity and metabolic health, including biomarkers associated with heterogeneity in response to interventions. Our most prominent proteins included IGFBP1/2 (insulin‐like growth factor‐binding protein 1/2) and FABP4 (fatty acid binding protein 4), proteins important in insulin signaling, adipocyte biology, and metabolism. 9 As a collaborative in the SFRN‐wide initiative, we successfully hosted colleagues from Northwestern SFRN for a 2‐week onsite shared learning visit among many other collaborative activities across all SFRNs. We have several publications 6 , 10 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 5 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 and have obtained several grants to provide follow‐on funding to sustain our initiatives:

R01 (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) multiple principal investigators A. C. Skinner/S. C. Armstrong: Fit Together: Implementation of Clinic Community Model of Child Obesity Treatment

R01 (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) principal investigator Lawrence David (using pilot data on microbiome from AHA): DNA metabarcoding of stool microbiome to determine dietary intake in children with obesity.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Contract/MITRE Corporation): Child Obesity Data Initiative—connecting clinic and community data to create longitudinal child health surveillance for obesity prevention and treatment.

Challenges

The COVID‐19 pandemic's impact on research operations was the most difficult challenge encountered. The pandemic shut down research operations midway through the project implementation period. This forced us to cut clinical enrollment short of our goal, transition our in‐person intervention to a remote‐based intervention, and collect follow‐up data remotely that otherwise would have been collected in a clinic setting. Other challenges encountered on the clinical project include our lead coordinator getting into a serious and debilitating car accident early in our recruitment efforts, which caused a temporary delay in enrollment until the measures, described previously, were implemented. This delay negatively affected timelines on the basic science project because that project relied on analyzing samples collected under the clinical project protocol. The population project experienced challenges with data sharing from other registry networks, which caused delays and ultimately required us to analyze a different internal data source rather than the proposed registry data source from the grant. This change in data source did not affect any scientific aims but rather caused some analysis delays.

Future Directions for the Center

The Duke Center's current focus is upon expanding community‐based interventions of obesity in youth that lead to future cardiovascular disease, as well as performing further studies of metabolomic mechanisms underpinning obesity. We have obtained additional grant funding to expand our clinic‐community model to other regions of North Carolina, We believe that some of the best work from the SFRN is still to come as the work from the clinical and basic projects comes to completion. It is hoped that correlates can be found between the metabolomics/microbiome data and the phenotypic and outcome correlates in our trial participants. Additionally, we have an exciting collaboration with the Northwestern SFRN evaluating cardiovascular risk phenoclusters in children with obesity. These findings will then be applied to the sample of children used in the basic science and clinical projects to examine the relationships between omics, behavioral factors, and the cardiovascular risk phenoclusters. Our overall goal is to interrogate these interactions to understand the mechanistic basis of obesity. Importantly, we currently have 2 National Institutes of Health grants and 1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant that were recently awarded to sustain our work.

University of Utah

Center Hypotheses and Goals

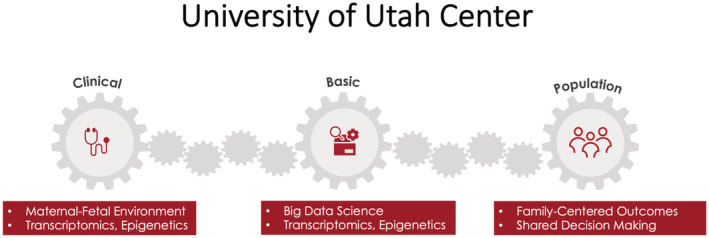

The integrating theme of the Utah Children's SFRN program centered on leveraging big data‐science approaches to improve the quality of care and outcomes for children with congenital heart defects, within the context of the patient and their family. The Utah Center sought to achieve this thematic goal by (1) advancing our understanding of disease pathogenesis, (2) laying the foundation for outcomes prediction, and (3) improving health care delivery using a family‐centered approach. Despite decades of high‐quality research, the explanation for the majority of isolated congenital heart defects remains unknown. All too often, we as clinicians are unable to satisfactorily answer the most common question asked by parents: “why did this happen?” The basic and clinical science projects investigated the hypothesis that the maternal–fetal environment and congenital heart defects are intricately linked via the placenta and that unique placenta transcriptomic signatures provide insight into the cause of congenital heart defects and prediction of clinical outcomes. The second most common question asked by families of a child with congenital heart defects is “what do we do next?” Despite physicians' best intentions to clearly explain the diagnosis of congenital heart defects, treatment options, and possible outcomes, it is often unclear how parents interpret or perceive this information, especially in the context of a life‐threatening new diagnosis. The Population Science project focused on understanding how parents make treatment decisions for their child with complex congenital heart defects, designing solutions to shared decision‐making challenges faced by families and providers and evaluating decision support interventions to improve the decision‐making process for these families (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Synergy among the basic, clinical, and population projects in Utah SFRN Center.

Successes and Challenges

A principal driver for the success of the Utah SFRN program was the collaborative spirit of investigators at the Utah Center and across the Children's SFRN consortium. Specifically, the Population Science project leaders successfully coordinated and conducted 10 focus groups with parents and 31 semistructured interviews with congenital heart defects practitioners across all participating Children's SFRN sites, identifying the informational needs, outcome priorities, and decision aid preferences of parents and clinicians. 2 , 4 Religious/spiritual beliefs and quality of life considerations factored prominently in individual family's approach to decision making. 2 Challenges to making clinical decisions included inconsistent communication of options by providers, the urgency of arriving at a decision, and the difficulty in processing complex information at a stressful time for families. Importantly, these results informed a randomized clinical trial to evaluate the impact of a decision aid, with and without a values clarification method, on parental physical and mental health, decision making and quality of clinical encounters. 3 While the clinical trial is ongoing, early preliminary data suggest that the decision aid may be beneficial in improving parents' psychological distress, perinatal grief, and general mental health, as well as improving their perspective of the effectiveness of risk communication and treatment decision making in clinician consultations compared with parents who did not receive decision aid.

Collaborative efforts across other SFRN programs proved crucial for the success of the Utah SFRN Clinical Science project. Ad hoc working groups were established with the members of the Children's and Go Red for Women SFRN networks interested in maternal health, specifically related to the role of the placenta. The working groups allowed for sharing ideas and protocols that informed the final manual of operations for tissue collection in the Clinical Science project. Although recruitment for the prospective case–control study is complete, placenta transcriptomic analyses are ongoing, using novel bioinformatic tools designed by members of the Basic Science team. Finally, collaborative efforts within members of the Utah SFRN program were instrumental in achieving the goals of the Basic Science project, culminating in published work describing integrated data‐science approaches to predicting the risk of CHD and CHD outcomes. 16 , 28 The Utah Center developed a novel and rigorous approach to risk‐factor identification and prediction, leveraging state‐of‐the‐art computational workflows to compute on EHRs at scale. 16 These data serve as inputs to an explainable artificial intelligence based platform that captures and quantifies synergistic (nonadditive) effects between variables that affect the outcome under study. 28 The ability to capture synergistic relationships between variables is a major advantage and innovation for risk prediction. Moreover, the ability to transform enormous collections of EHRs into compact, portable tools devoid of protected health information solves many of the legal, technological, and data‐scientific challenges associated with large‐scale EHR analyses.

The COVID‐19 pandemic created significant challenges for the Utah SFRN Center, principally related to recruitment for the Clinical and Population Science projects. Collaboration with Northwestern/Lurie Children's Hospital and the Magee Women's Institute to increase recruitment for the clinical case–control project was severely compromised by the pandemic onset and ultimately, recruitment at those sites was abandoned. However, preliminary placental transcriptomic data allowed for updated calculations to ensure appropriate power with revised recruitment goals that were ultimately achieved. Transcriptomic and epigenetic analyses of cases and control placental samples are currently underway, with expected timeline for completion targeted to the end of the no cost extension period. Likewise, recruitment of parents for the Population Science project was significantly affected by the pandemic, but this deficit will be overcome during the no‐cost extension period.

Future Directions for the Center

The Children's SFRN program provided unique research and training opportunities for the Utah Center that will continue to thrive long after the funding period ends. The successful data‐science approaches and decision support tools were leveraged to support junior faculty members' R01 and K‐award pathways in atrial fibrillation, maternal–fetal medicine, bicuspid valve disease, and CHD (pending review) that will open new directions of translational science, while launching the careers of clinician‐scientists. Preliminary data from the clinical and population Science projects provides a glimpse into impactful findings with the potential to alter how we care for children with congenital heart defects and their families. The Utah SFRN Center anticipates that data from each project will be successfully leveraged into future funding opportunities focused on improving the quality of care and outcomes for children with congenital heart defects and the family's experience with their child's health care journey.

Northwestern/Lurie Children's

Center Hypotheses and Goals

“Cardiovascular health” (CVH) was first formally defined by the AHA in 2010 and updated and refined in 2022, in terms of 7 (now 8) behavioral and biologic metrics (diet, physical activity, smoking, sleep, BMI, blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose). 53 Favorable status on these metrics taken together as a composite CVH score, at age 50, is strongly predictive of healthy longevity, including near absence of major cardiovascular disease events through the remaining life course. But its prevalence at middle age is very low (<10%), having declined sharply with age beginning in early childhood. 14 , 54 , 55 , 56

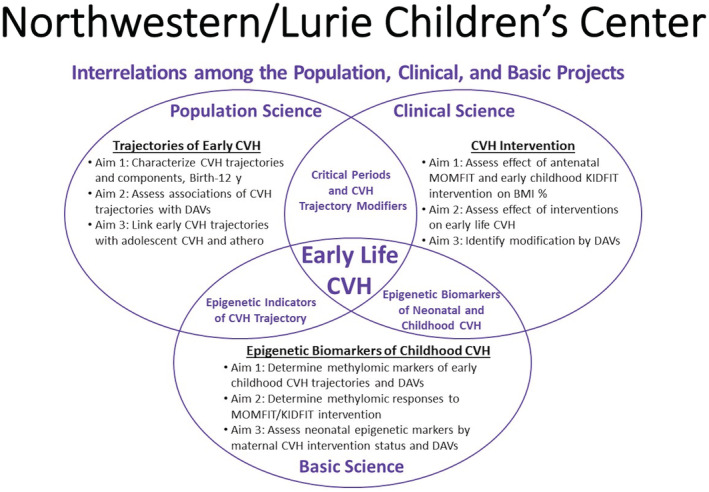

Our overarching hypothesis is that the early course of change in CVH, from birth onward, reflects factors that result in either subsequent development of cardiovascular risk or preservation of lifetime favorable CVH (Figure 4). Discovery of the trajectories of CVH from the beginning of life will enable systematic measurement, monitoring, and modification of CVH from early life onward, through lifestyle, pharmacologic, public health, and health policy interventions . 57

Figure 4. Synergy among the population, clinical and basic science projects of the Northwestern SFRN Center.

BMI % denotes body mass index percentile; CVH, cardiovascular health; DAVs, developmental assets and vulnerabilities; KIDFIT, Keeping Ideal CVH Family Intervention Trial; and MOMFIT, Maternal–Offspring Metabolics Family Intervention Trial.

To define this novel paradigm for cardiovascular research, policy, and practice, our venter has conducted synergistic population, clinical, and basic science research and training that have narrowed major gaps in prior knowledge. In addition, this venter for the first time assessed the modifying effects on CVH of early life developmental assets and vulnerabilities. These include aspects of neurodevelopmental health and social environmental exposures on CVH trajectories that are suggested by compelling evidence that developmental assets and vulnerabilities influence lifelong behavior, health, and quality of life. 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65

Successes and Challenges

The Population Science Project identified early life trajectories of CVH and its components from birth through age 12 with data from a Chicago‐wide EHR consortium. Records were analyzed of over 20 million patient encounters with 1.2 million children ranging in age from birth to 12 years. Decline in levels of CVH from early childhood was confirmed and was driven by increasing BMI. Disparities by race or ethnicity with less favorable BMI and cholesterol were evident by age 2. Three distinct trajectories were identified among groups aged 2 to 12 years: almost 60% of children maintained high levels of clinical CVH, one quarter had high levels of clinical CVH early that declined in their later childhood/early teens, and ≈17% had intermediate levels of clinical CVH early in childhood that further declined with age. Neurodevelopmental health was investigated in relation to CVH among 231 children of diverse socioeconomic status with the finding of associations with adverse childhood exposures in analyses with adjustment for demographic and economic factors. High parental CVH was discovered to be a strong predictor of high CVH in the child. This project thus contributed to the impact of the center by closing the gap in knowledge of CVH developmental trajectories between ages 2 and 8 or 12 years, the lower age observed in most previous studies, and adding insights to the relation of early life CVH with race or ethnicity, BMI, adverse childhood experiences, and parental CVH. Both administrative delays in merging data systems and COVID‐related delays in participant evaluations were addressed with flexible scheduling.

The Clinical Science Project investigated methods and procedures for a future clinical trial of a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension‐type dietary intervention for improving CVH in early childhood. Recruitment, CVH assessment, intervention, and evaluation were tested in 3‐ to 5‐year‐old participants whose mothers were all previously recruited to a study called MOMFIT (Maternal–Offspring Metabolics Family Intervention Trial) designed to restrict excessive gestational weight gain among women who were overweight or obese through dietary and lifestyle intervention. 66 Because COVID introduced serious challenges with respect to each of these procedures, extensive adaptation and innovation were required in order to collect pilot data giving evidence of intervention benefit for diet quality on CVH at 12 months. The success of these adaptations enabled completion of the pilot study, albeit with reduced final sample size, that provided valuable lessons about methodological alternatives and a family oriented intervention that will serve in future studies. The clinical project thus added to the center's impact by laying the groundwork for further research on the ability to modify CVH trajectories through dietary interventions to promote, preserve, or improve dietary patterns in early life.

The Basic Science Project was closely linked with the population and clinical science projects by using materials from both studies. This research strategy enabled identification of novel blood‐based epigenomic biomarkers of trajectories of CVH and occurrence of neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities and, additionally, and predictors of effectiveness of childhood dietary intervention. The data outputs include DNA genome‐wide methylation association analyses (among mothers and children), mother–child paired methylomic profile comparisons, postintervention methylomic profile comparisons, and epigenetic age analyses. Our preliminary analysis identified signs of differentially methylated sites in children that were associated with childhood clinical CVH at baseline (in particular, BMI). Some of the children's markers were also associated with the mother's CVH profile. For postintervention analysis, it was challenging to perform an epigenome‐wide search because of the small effect size and a short period of follow‐up. Therefore, we are aiming to test the intervention effects by focusing on only the top markers that were associated with children's or mothers’ CVH profiles. Epigenetic age analysis is ongoing as the methods for epigenetic age estimation among children are limited, which is a challenge that requires further validation. This project has contributed to the center with potential expansion of tools to measure and monitor CVH and to predict and evaluate intervention outcomes. Adaptive scheduling changes in the Population and Clinical Science Projects delayed laboratory acquisition of study materials, requiring corresponding rescheduling.

Future Directions for the Center

Catalyzed by the AHA funding, the Northwestern SFRN has already embarked on future endeavors. Ongoing activities are leveraging the extensive data to publish new insights on the mechanisms and outcomes of childhood CVH from birth. We are implementing and testing new means for allowing clinicians, patients, and families to track trajectories of CVH from early life. The ultimate goal is for CVH to be a new “vital sign” that can be tracked from birth into adulthood, just as height and BMI are tracked for children on nomograms, so that maintenance of high CVH can be monitored, and any declines in CVH over time are quickly identified and can trigger health‐promoting interventions. The center investigators also have embarked on a large study (the Young Hearts study) to track CVH in thousands of youth across multiple health systems in the city of Chicago. Based on the experiences catalyzed by the center, the leadership is also developing plans for a new training program in childhood CVH.

Strengths and Future Opportunities for SFRNs

The Children's SFRN came together in 2017 as a group of 4 centers focused on widely diverse aspects of children's cardiovascular health, all of which represent major public health issues: RHD, CHD, childhood and adolescent obesity, and early life trajectories and mechanisms of CVH. Despite disparate scientific approaches, diverse geographic areas of focus across the country and the globe, and notable challenges to participant recruitment posed by the COVID‐19 pandemic, the 4 centers each achieved remarkable progress in addressing their own compelling science and also collectively created novel collaborations to leverage each other's strengths and address new areas of science.

The Children‘s National Center has generated critical insights into the immunology of vaccine responses to Group A Streptococcus that will advance global prevention efforts while also making critical inroads on diagnosis and management capacity in low‐ and middle‐income country settings. Leveraging its unique big data infrastructure on genomics, family pedigrees, and clinical data, the Utah Center is making ongoing insights into prediction of congenital heart defects and the role of the placenta in their development and actively testing strategies for improving the processes of decision making and care for families whose children have congenital heart defects. A notable collaboration across all 4 centers in the network led to focus groups at each site that informed the development and design of a decision aid for practitioners and families that is currently being tested in a clinical trial. The Duke Center successfully tested and implemented a novel strategy for weight loss in children and adolescents pairing clinical and community‐based resources and pivoted the intervention to a remote strategy during the pandemic. Ongoing insights into the microbiome, and its changes with lifestyle interventions, will provide deeper insights into the mechanisms of successful weight loss. The Northwestern Center leveraged data from millions of patient encounters to define early life trajectories of CVH from birth to age 10 and is assessing the contributions of genome‐wide and specific DNA methylation marks in determining those trajectories, both observationally and after a dietary intervention. The close alignment between the Duke and Northwestern Centers’ aims allowed for additional collaborations around childhood health interventions and deeper phenotyping of CVH in children and associations with multiple omics pathways. Other collaborations reached beyond the Children's SFRN to engage investigators from multiple other AHA‐funded SFRN centers addressing related areas of science.

Each of the 4 centers has successfully leveraged the data and infrastructure of its center and the network to obtain follow‐on funding of major scientific projects. Similarly, each center successfully trained 3 fellows and advanced their careers through mentoring and providing network‐wide opportunities for growth in skills and knowledge.

At the end of the SFRN funding period, it is important to acknowledge the substantial challenges to recruitment, performance of science, and collaboration that were posed by the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nonetheless, the centers and network pivoted successfully to achieve their broad aims and affect the field of children's cardiovascular health in tangible ways. The diverse areas of focus of the 4 centers did not naturally suggest immediate collaborative opportunities, but the investigators found innovative areas of common ground for new studies, and they came together successfully in the joint effort of training junior colleagues.

Future opportunities are already emerging as several of the centers leverage their SFRN data to continue their important work with new funding sources and as SFRN‐based collaborations evolve into exciting areas of omics and deeper phenotyping of childhood health and disease states that will drive further innovations in health care and lifelong prevention.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network.

Disclosures

None.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

REFERENCES

- 1. de Loizaga SR, Arthur L, Arya B, Beckman B, Belay W, Brokamp C, Hyun Choi N, Connolly S, Dasgupta S, Dibert T, et al. Rheumatic heart disease in the United States: forgotten but not gone: results of a 10 year multicenter review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e020992. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.020992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Delaney RK, Pinto NM, Ozanne EM, Brown H, Stark LA, Watt MH, Karasawa M, Patel A, Donofrio MT, Steltzer MM, et al. Parents’ decision‐making for their foetus or neonate with a severe congenital heart defect. Cardiol Young. 2022;32:896–903. doi: 10.1017/S1047951121003218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Delaney RK, Pinto NM, Ozanne EM, Stark LA, Pershing ML, Thorpe A, Witteman HO, Thokala P, Lambert LM, Hansen LM, et al. Study protocol for a randomised clinical trial of a decision aid and values clarification method for parents of a fetus or neonate diagnosed with a life‐threatening congenital heart defect. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e055455. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pinto NM, Patel A, Delaney RK, Donofrio MT, Marino BS, Miller S, Ozanne EM, Zickmund SL, Karasawa MH, Pershing ML, et al. Provider insights on shared decision‐making with families affected by CHD. Cardiol Young. 2021;32:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1047951121004406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aguayo L, Chirinos DA, Heard‐Garris N, Wong M, Davis MM, Merkin SS, Seeman T, Kershaw KN. Association of exposure to abuse, nurture, and household organization in childhood with 4 cardiovascular disease risks factors among participants in the CARDIA study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023244. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.023244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alexander E, Skinner A, Gaskin K, Jones J, Wong C, Loflin C, Fleming R, Howard J, Armstrong S, Neshteruk C. A mixed‐methods examination of referral processes to clinic‐community partnership programs for the treatment of childhood obesity. Child Obes. 2021;17:516–524. doi: 10.1089/chi.2020.0361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barth DD, Naicker P, Engel K, Muhamed B, Basera W, Mayosi BM, Dale JB, Engel ME. Molecular epidemiology of noninvasive and invasive group a streptococcal infections in Cape Town. mSphere. 2019;4:e00421‐19. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00421-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beaton A, Okello E, Rwebembera J, Grobler A, Engelman D, Alepere J, Canales L, Carapetis J, DeWyer A, Lwabi P, et al. Secondary antibiotic prophylaxis for latent rheumatic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:230–240. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bihlmeyer NA, McCann JR, Rawls JF, Skinner A, Armstrong S, Li J, Shah S. Pediatrics and proteins: unique biology of children undergoing obesity intervention. NHGRI Annual Training & Career Development Meeting. 2022.

- 10. D'Agostino EM, Day SE, Konty KJ, Armstrong SC, Skinner AC, Neshteruk CD. Longitudinal association between weight status, aerobic capacity, muscular strength, and endurance among new York City youth, 2010‐2017. Child Obes. 2022. doi: 10.1089/chi.2022.0034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. US Preventive Services Task Force , Grossman DC, Bibbins‐Domingo K, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Kemper AR, Krist AH, et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US preventive services task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317:2417–2426. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fryar C, Carroll M, Afful J. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity among children and adolescents aged 2–19 years: United States, 1963–1965 through 2017–2018. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021.

- 13. Joyce BT, Gao T, Zheng Y, Ma J, Hwang SJ, Liu L, Nannini D, Horvath S, Lu AT, Bai Allen N, et al. Epigenetic age acceleration reflects long‐term cardiovascular health. Circ Res. 2021;129:770–781. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krefman AE, Labarthe D, Greenland P, Pool L, Aguayo L, Juonala M, Kahonen M, Lehtimaki T, Day RS, Bazzano L, et al. Influential periods in longitudinal clinical cardiovascular health scores. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190:2384–2394. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lange SJ, Kompaniyets L, Freedman DS, Kraus EM, Porter R, Dnp BHM, Goodman AB. Longitudinal trends in body mass index before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic among persons aged 2‐19 years—United States, 2018‐2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1278–1283. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lemmon G, Wesolowski S, Henrie A, Tristani‐Firouzi M, Yandell M. A Poisson binomial‐based statistical testing framework for comorbidity discovery across electronic health record datasets. Nat Comput Sci. 2021;1:694–702. doi: 10.1038/s43588-021-00141-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neshteruk CD, Jones DJ, Skinner A, Ammerman A, Tate DF, Ward DS. Understanding the role of fathers in children's physical activity: a qualitative study. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17:540–547. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2019-0386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neshteruk CD, Norman K, Armstrong SC, Cholera R, D'Agostino E, Skinner AC. Association between parenthood and cardiovascular disease risk: analysis from NHANES 2011‐2016. Prev Med Rep. 2022;27:101820. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Neshteruk CD, Zizzi A, Suarez L, Erickson E, Kraus WE, Li JS, Skinner AC, Story M, Zucker N, Armstrong SC. Weight‐related behaviors of children with obesity during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Child Obes. 2021;17:371–378. doi: 10.1089/chi.2021.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Okello E, Ndagire E, Atala J, Bowen AC, DiFazio MP, Harik NS, Longenecker CT, Lwabi P, Murali M, Norton SA, et al. Active case finding for rheumatic fever in an endemic country. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016053. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Okello E, Ndagire E, Muhamed B, Sarnacki R, Murali M, Pulle J, Atala J, Bowen AC, DiFazio MP, Nakitto MG, et al. Incidence of acute rheumatic fever in northern and western Uganda: a prospective, population‐based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e1423–e1430. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00288-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Opara CC, Du Y, Kawakatsu Y, Atala J, Beaton AZ, Kansiime R, Nakitto M, Ndagire E, Nalubwama H, Okello E, et al. Household economic consequences of rheumatic heart disease in Uganda. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:636280. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.636280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reges O, Ning H, Wilkins JT, Wu CO, Tian X, Domanski MJ, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Allen NB. Association of cumulative systolic blood pressure with long‐term risk of cardiovascular disease and healthy longevity: findings from the lifetime risk pooling project cohorts. Hypertension. 2021;77:347–356. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salie MT, Rampersadh K, Muhamed B, Engel KC, Zuhlke LJ, Dale JB, Engel ME. Utility of human immune responses to GAS antigens as a diagnostic indicator for ARF: a systematic review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:691646. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.691646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salie T, Engel K, Moloi A, Muhamed B, Dale JB, Engel ME. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of the prevalence of group a streptococcal emm clusters in Africa to inform vaccine development. mSphere. 2020;5:e00429‐20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00429-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17:95–107. doi: 10.1111/obr.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stein E, Pulle J, Zimmerman M, Otim I, Atala J, Rwebembera J, Oyella LM, Harik N, Okello E, Sable C, et al. Previous traditional medicine use for sore throat among children evaluated for rheumatic fever in northern Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104:842–847. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wesołowski S, Lemmon G, Hernandez EJ, Henrie A, Miller TA, Weyhrauch D, Puchalski MD, Bray BE, Shah RU, Deshmukh VG, et al. An explainable artificial intelligence approach for predicting cardiovascular outcomes using electronic health records. PLOS Digit Health. 2022;1:1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zimmerman M, Kitooleko S, Okello E, Ollberding N, Sinha P, Mwambu T, Sable C, Beaton A, Longenecker C, Lwabi P. Clinical outcomes of children with rheumatic heart disease. Heart. 2022;108:633–638. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2021-320356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zimmerman M, Sable C. Congenital heart disease in low‐and‐middle‐income countries: focus on sub‐Saharan Africa. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2020;184:36–46. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zimmerman M, Scheel A, DeWyer A, Nambogo JL, Otim IO, Tompsett A, Rwebembera J, Okello E, Sable C, Beaton A. Determining the risk of developing rheumatic heart disease following a negative screening echocardiogram. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:632621. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.632621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thorpe A, Scherer AM, Han PKJ, Burpo N, Shaffer V, Scherer L, Fagerlin A. Exposure to common geographic COVID‐19 prevalence maps and public knowledge, risk perceptions, and behavioral intentions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2033538. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weyhrauch DL, Truong DT, Pinto NM, Amula V, Lambert LM, Zhang C, Presson AP, Wilkes J, Minich LL, Williams RV. Changes in provider prescribing behavior for infants with single ventricle physiology after evidence‐based publications. Pediatr Cardiol. 2021;42:1224–1232. doi: 10.1007/s00246-021-02606-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, Karthikeyan G, Beaton A, Bukhman G, Forouzanfar MH, Longenecker CT, Mayosi BM, Mensah GA, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990‐2015. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:713–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Watkins D, Zuhlke L, Engel M, Daniels R, Francis V, Shaboodien G, Kango M, Abul‐Fadl A, Adeoye A, Ali S, et al. Seven key actions to eradicate rheumatic heart disease in Africa: I Addis Ababa communique. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2016;27:1–5. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2015-090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carapetis JR, Beaton A, Cunningham MW, Guilherme L, Karthikeyan G, Mayosi BM, Sable C, Steer A, Wilson N, Wyber R, et al. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:15084. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Remenyi B, Carapetis J, Wyber R, Taubert K, Mayosi BM, World Heart Federation . Position statement of the world heart federation on the prevention and control of rheumatic heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:284–292. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carapetis JR, Zuhlke L, Taubert K, Narula J. Continued challenge of rheumatic heart disease: the gap of understanding or the gap of implementation? Global Heart. 2013;8:185–186. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ndagire E, Ollberding N, Sarnacki R, Meghna M, Pulle J, Atala J, Agaba C, Kansiime R, Bowen A, Longenecker CT, et al. Modelling study of the ability to diagnose acute rheumatic fever at different levels of the Ugandan healthcare system. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e050478. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chang AY, Barry M, Bendavid E, Watkins D, Beaton AZ, Lwabi P, Ssinabulya I, Longenecker CT, Okello E. Mortality along the rheumatic heart disease cascade of care in Uganda. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15:e008445. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nalubwama H, Ndagire E, Sarnacki R, Atala J, Beaton A, Kansiime R, Mwima R, Okello E, Watkins D. Community perspectives on primary prevention of rheumatic heart disease in Uganda. Glob Heart. 2022;17:5. doi: 10.5334/gh.1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ndagire E, Kawakatsu Y, Nalubwama H, Atala J, Sarnacki R, Pulle J, Kyarimpa R, Mwima R, Kansiime R, Okello E, et al. Examining the Ugandan health system's readiness to deliver rheumatic heart disease‐related services. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Beaton A, Kamalembo FB, Dale J, Kado JH, Karthikeyan G, Kazi DS, Longenecker CT, Mwangi J, Okello E, Ribeiro ALP, et al. The American Heart Association's call to action for reducing the global burden of rheumatic heart disease: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e358–e368. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kumar RK, Antunes MJ, Beaton A, Mirabel M, Nkomo VT, Okello E, Regmi PR, Remenyi B, Sliwa‐Hahnle K, Zuhlke LJ, et al. Contemporary diagnosis and management of rheumatic heart disease: implications for closing the gap: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e337–e357. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D'Agostino EM, Armstrong SC, Alexander EP, Ostbye T, Neshteruk CD, Skinner AC. Predictors and patterns of physical activity from transportation among United States youth, 2007‐2016. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Granados I, Haderer EL, D'Agostino EM, Neshteruk CD, Armstrong SC, Skinner AC, D'Agostino EM. The association between neighborhood public transportation usage and youth physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61:733–737. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Skinner AC, Xu H, Christison A, Neshteruk C, Cuda S, Santos M, Yee JK, Thomas L, King E, Kirk S. Patient retention in pediatric weight management programs in the United States: analyses of data from the pediatrics obesity weight evaluation registry. Child Obes. 2022;18:31–40. doi: 10.1089/chi.2021.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Armstrong SC, Skinner AC. D“fining "”uccess" in childhood obesity interventions in primary care. Pediatrics. 2016;138:138. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Armstrong SC, Windom M, Bihlmeyer NA, Li JS, Shah SH, Story M, Zucker N, Kraus WE, Pagidipati N, Peterson E, et al. Rationale and design of “hearts & parks”: study protocol for a pragmatic randomized clinical trial of an integrated clinic‐community intervention to treat pediatric obesity. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:308. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02190-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bihlmeyer NA, Kwee LC, Clish CB, Deik AA, Gerszten RE, Pagidipati NJ, Laferrere B, Svetkey LP, Newgard CB, Kraus WE, et al. Metabolomic profiling identifies complex lipid species and amino acid analogues associated with response to weight loss interventions. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0240764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McCann JR, Bihlmeyer NA, Roche K, Catherine C, Jawahar J, Kwee LC, Younge NE, Silverman J, Ilkayeva O, Sarria C, et al. The pediatric obesity microbiome and metabolism study (POMMS): methods, baseline data, and early insights. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29:569–578. doi: 10.1002/oby.23081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Suarez L, Skinner AC, Truong T, McCann JR, Rawls JF, Seed PC, Armstrong SC. Advanced obesity treatment selection among adolescents in a pediatric weight management program. Child Obes. 2022;18:237–245. doi: 10.1089/chi.2021.0190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Labarthe D, Lloyd‐Jones DM. 50×50×50: cardiovascular health and the cardiovascular disease endgame. Circulation. 2018;138:968–970. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Perak AM, Marino BS, de Ferranti SD. Squaring the curve of cardiovascular health from the beginning of life. Pediatrics. 2018;141:141. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Allen NB, Krefman AE, Labarthe D, Greenland P, Juonala M, Kahonen M, Lehtimaki T, Day RS, Bazzano LA, Van Horn LV, et al. Cardiovascular health trajectories from childhood through middle age and their association with subclinical atherosclerosis. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:557–566. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, Black T, Brewer LC, Foraker RE, Grandner MA, Lavretsky H, Perak AM, Sharma G, et al. Life's essential 8: updating and enhancing the American Heart Association's construct of cardiovascular health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146:e18–e43. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Daniels SR, Pratt CA, Hollister EB, Labarthe D, Cohen DA, Walker JR, Beech BM, Balagopal PB, Beebe DW, Gillman MW, et al. Promoting cardiovascular health in early childhood and transitions in childhood through adolescence: a workshop report. J Pediatr. 2019;209:240–251.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wiebe SA, Clark CA, De Jong DM, Chevalier N, Espy KA, Wakschlag L. Prenatal tobacco exposure and self‐regulation in early childhood: implications for developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2015;27:397–409. doi: 10.1017/S095457941500005X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wakschlag LS, Estabrook R, Petitclerc A, Henry D, Burns JL, Perlman SB, Voss JL, Pine DS, Leibenluft E, Briggs‐Gowan ML. Clinical implications of a dimensional approach: the normal:abnormal spectrum of early irritability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Clark CA, Espy KA, Wakschlag L. Developmental pathways from prenatal tobacco and stress exposure to behavioral disinhibition. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2016;53:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2015.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mellion K, Uzark K, Cassedy A, Drotar D, Wernovsky G, Newburger JW, Mahony L, Mussatto K, Cohen M, Limbers C, et al. Health‐related quality of life outcomes in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2014;164:781–788.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, Peacock G, Gerdes M, Gaynor JW, Mussatto KA, Uzark K, Goldberg CS, Johnson WH Jr, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126:1143–1172. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318265ee8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Marino BS, Cassedy A, Drotar D, Wray J. The impact of neurodevelopmental and psychosocial outcomes on health‐related quality of life in survivors of congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2016;174:11–22.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Marino BS, Tomlinson RS, Wernovsky G, Drotar D, Newburger JW, Mahony L, Mussatto K, Tong E, Cohen M, Andersen C, et al. Validation of the pediatric cardiac quality of life inventory. Pediatrics. 2010;126:498–508. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gerstle M, Beebe DW, Drotar D, Cassedy A, Marino BS. Executive functioning and school performance among pediatric survivors of complex congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2016;173:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Redman LM, Drews KL, Klein S, Horn LV, Wing RR, Pi‐Sunyer X, Evans M, Joshipura K, Arteaga SS, Cahill AG, et al. Attenuated early pregnancy weight gain by prenatal lifestyle interventions does not prevent gestational diabetes in the LIFE‐moms consortium. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;171:108549. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]