Abstract

Background

Racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes exist following many cardiac procedures. Transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) has grown as an alternative to mitral valve surgery for patients at high surgical risk. The outcomes of TMVR by race and ethnicity are unknown. We aimed to evaluate racial and ethnic disparities in the outcomes of TMVR.

Methods and Results

We analyzed the National Inpatient Sample database from 2016 to 2020 to identify hospitalizations for TMVR. Racial and ethnic disparities in TMVR outcomes were determined using logistic regression models. Between 2016 and 2020, 5005 hospitalizations for TMVR were identified, composed of 3840 (76.7%) White race, 505 (10.1%) Black race, 315 (6.3%) Hispanic ethnicity, and 345 (6.9%) from other races (Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, Other). Compared with other racial and ethnic groups, Black patients were significantly younger and more likely to be women (both P<0.01). There were no significant differences between White, Black, and Hispanic patients in in‐hospital mortality (5.2% versus 5.0% versus <3.5%; P=0.89) and procedural complications, including heart block (P=0.91), permanent pacemaker (P=0.49), prosthetic valve dysfunction (P=0.45), stroke (P=0.37), acute kidney injury (P=0.32), major bleeding (P=0.23), and blood transfusion (P=0.92), even after adjustment for baseline characteristics. Adjusted vascular complications were higher in Black compared with White patients (P=0.03). Trend analysis revealed a significant increase in TMVR in all racial and ethnic groups from 2016 to 2020 (P trend<0.05).

Conclusions

Between 2016 and 2020, Black and Hispanic patients undergoing TMVR had similar in‐hospital outcomes compared with White patients, except for higher vascular complications in Black patients. Further comparative studies of TMVR in clinically similar White patients and other racial and ethnic groups are warranted to confirm our findings.

Keywords: mitral valve disease, mitral valve replacement, racial issues

Subject Categories: Catheter-Based Coronary and Valvular Interventions, Disparities, Health Equity, Mortality/Survival, Complications

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Among patients undergoing transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR), 10.1% were Black race, which is close to the relative percentage of Black people in the US population (12.6% in 2020).

Only 6.3% of patients undergoing TMVR were Hispanic ethnicity, reflecting the significant underrepresentation of Hispanic people compared with their relative percentage in the US population (18.7% in 2020).

Black and Hispanic patients undergoing TMVR have similar in‐hospital mortality and complications compared with White patients, with the exception of higher vascular complications in Black patients.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Our study highlights the underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic patients in TMVR despite similar clinical outcomes compared with White patients.

Further comparative studies of TMVR in clinically similar White patients and other racial and ethnic groups are warranted to identify the reasons for such disparities in TMVR use and to guide policy initiatives to achieve equity.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- MR

mitral regurgitation

- MVD

mitral valve disease

- M‐TEER

mitral transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair

- NIS

National Inpatient Sample

- PPM

permanent pacemaker

- TAVR

transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- TMVR

transcatheter mitral valve replacement

Surgical mitral valve repair or replacement remains the standard of care for degenerative mitral regurgitation (MR). 1 , 2 MR has become the most prevalent valvular heart disease in developed countries because of the decreased prevalence of rheumatic heart disease and mitral stenosis in these countries. 3 , 4 In addition, the incidence of functional MR has increased because of the increasing prevalence of ischemic heart disease and increased longevity in patients with heart failure. 5 Furthermore, the prevalence of MR increases with age, with significantly higher MR rates in the elderly population (0.5% [for those aged 18–44 years] versus 10% [for those aged ≥75 years]). 4 Consequently, the increasing incidence of MR, coupled with the aging populations in developed countries, has led to a growing population of elderly patients with mitral valve disease (MVD) who may be high‐risk candidates for surgical mitral valve interventions. 6 Therefore, percutaneous therapies, including mitral transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (M‐TEER; MitraClip, Abbott, Chicago, IL) and transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR), were developed as therapeutic options in patients with MVD. 7

Racial and ethnic disparities exist in the outcomes of many cardiac interventions, such as percutaneous coronary intervention, 8 coronary artery bypass surgery, 9 surgical aortic valve replacement, 10 , 11 , 12 and surgical mitral valve interventions. 12 , 13 Although racial and ethnic disparities in the use and in‐hospital outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) 14 , 15 and M‐TEER 16 have been studied in the past, disparities in TMVR outcomes have not been reported. Therefore, we analyzed the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database to investigate in‐hospital outcomes following TMVR in different racial and ethnic groups.

METHODS

Data Source and Ethics Statement

Hospitalization data were abstracted from the NIS database, which is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) family of databases sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 17 The specific data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author on request. The NIS is the largest publicly available fully deidentified all‐payer inpatient health care database in the United States. The NIS is derived from billing data submitted by hospitals to statewide organizations across the United States and has reliable and verified patient linkage numbers that can be used to track patients across hospitals within each state while adhering to strict privacy guidelines. The NIS database contains both patient‐ and hospital‐level information from ≈1000 hospitals and represents ≈20% of all US hospitalizations, covering >7 million unweighted hospitalizations each year. When weighted, the NIS extrapolates to the national level ≈35 million hospitalizations each year. Up to 40 discharge diagnoses and 25 procedures are collected for each patient using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9), codes 18 until September 2015 and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10), codes 19 from October 2015 through 2020. The NIS is compiled annually, which would allow the data to be used for analysis of disease trends over time. 20 This study was acknowledged as not human subjects research by the Institutional Review Board at Creighton University (infoEd record number: 2002777‐01).

Study Population and Patient Selection

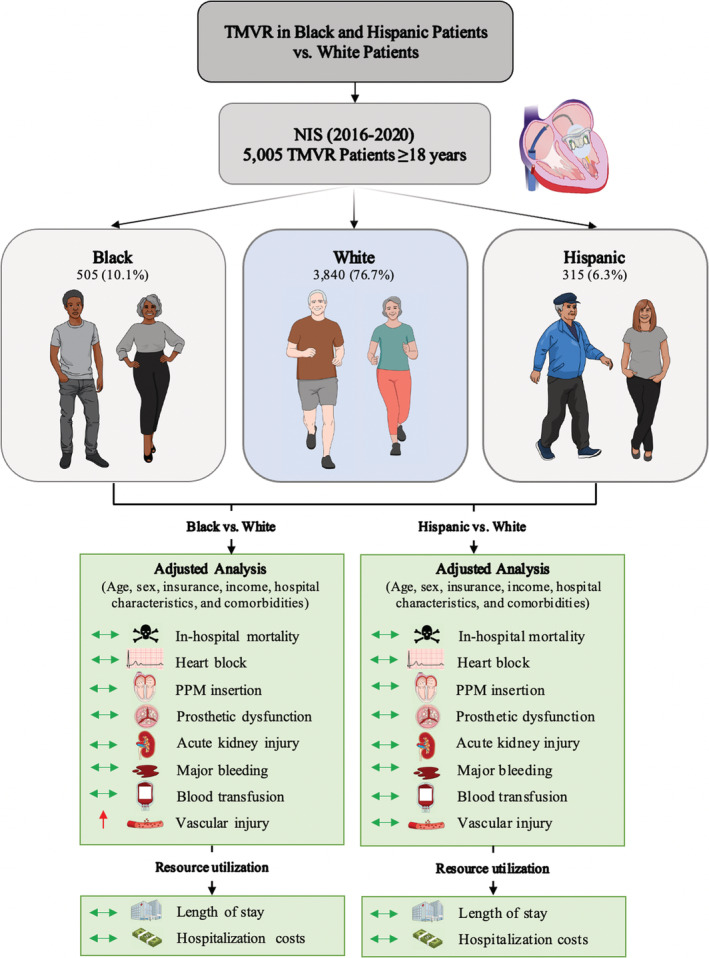

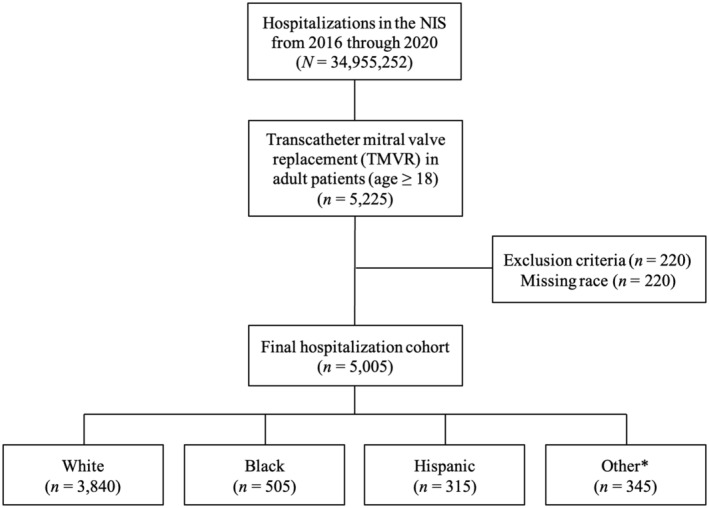

We queried the NIS database from January 2016 to December 2020 to identify hospitalizations in which adult patients (aged ≥18 years) underwent TMVR (ICD‐10, Procedure Coding System 02RG37H, 02RG38H, 02RG3JH, 02RG3KH, 02RG37Z, 02RG38Z, 02RG3JZ, and 02RG3KZ in any procedural field). We excluded hospitalizations in which the patient was aged <18 years as well as those with missing data on race. For hospitalizations that met inclusion criteria, we then stratified the total cohort by race and ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, and other). NIS combines “race” and “ethnicity” into 1 data element (race). If both “race” and “ethnicity” were available, ethnicity was preferred over race in assigning the HCUP value for “race.” 21 For the purpose of this analysis, 3 racial and ethnic groups with small sample sizes (Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Other) were combined into a single “other” group to facilitate the analysis. The other 3 HCUP race/ethnicity groups (White, Black, and Hispanic) were left unchanged for the study. “White” group refers to non‐Hispanic White patients, “Black” group refers to non‐Hispanic Black patients, and “Hispanic” group refers to Hispanic patients of all races and origins. The key findings and a detailed flow diagram are presented in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1. Key study findings.

Reported numbers represent national‐level estimates. NIS indicates National Inpatient Sample; PPM, permanent pacemaker; and TMVR, transcatheter mitral valve replacement.

Figure 2. Study flow diagram showing inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Hospitalization counts represent national‐level estimates. NIS indicates National Inpatient Sample; and TMVR, transcatheter mitral valve replacement. *Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Other.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was all‐cause in‐hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes were heart block, permanent pacemaker (PPM) insertion, prosthetic valve dysfunction, stroke, acute kidney injury (AKI), major bleeding, need for blood transfusion, and vascular complications (defined as a composite of arteriovenous fistula, aneurysm, hematoma, retroperitoneal bleeding, and venous thromboembolism). When evaluating PPM insertion post‐TMVR, we excluded patients with a known history of PPM. We also evaluated hospital length of stay (LOS), total hospital costs (inflation adjusted to 2020 US dollars 22 ), and discharge disposition, as well as independent predictors of in‐hospital mortality. The temporal trends in TMVR use, hospital LOS, and total costs were also assessed during the study period. Two authors (M.I. and M.A.A.) independently verified the ICD‐10 codes corresponding to each of the in‐hospital outcomes (Table S1), and any disagreements regarding inclusion or exclusion of ICD‐10 codes were resolved with a third author (N.S.A).

Statistical Analysis

The cohort of hospitalizations for TMVR was stratified by race and ethnicity. Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson χ2 test, whereas continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal‐Wallis 1‐way ANOVA. We reported categorical variables as percentages and continuous variables as medians with interquartile ranges.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to adjust for potential confounders, which included age, sex, insurance, income, hospital location and teaching status, bed size, region, type of admission (elective/nonelective and weekend/weekday), Elixhauser and Charlson index scores, and relevant comorbidities (Table S2). Adjustment variables were selected a priori on the basis of their clinical significance, which may directly influence in‐hospital outcomes. The results from these models are presented as adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs.

The multivariate regression model was also used to determine independent predictors of all‐cause in‐hospital mortality in patients undergoing TMVR using relevant demographic and clinical variables, shown in Tables 1 and 2. We generated a receiver operating characteristic curve and estimated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve to assess the accuracy of the predictive model (Figure S1). Trend analyses from 2016 through 2020 were conducted using linear regression.

Table 1.

Demographic and Hospital Characteristics Stratified by Race and Ethnicity

| Variable | White race (n=3840) | Black race (n=505) | Hispanic ethnicity (n=315) | Other race§ (n=345) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age, y | 76 (68–81) | 65 (55–74) | 68 (56–77) | 74 (58–81) | <0.01 |

| 18–64 | 16.8 | 49.5 | 41.3 | 31.9 | <0.01 |

| 65–74 | 28.9 | 26.7 | 25.4 | 18.8 | |

| 75–84 | 40.5 | 20.8 | 30.2 | 40.6 | |

| ≥85 | 13.8 | 3.0 | NR* | 8.7 | |

| Biological sex | |||||

| Men | 46.0 | 28.7 | 44.4 | 44.9 | 0.01 |

| Women | 54.0 | 71.3 | 55.6 | 55.1 | |

| Insurance | |||||

| Medicare | 84.2 | 66.0 | 59.7 | 58.8 | <0.01 |

| Medicaid | 3.3 | 13.0 | 12.9 | 16.2 | |

| Private insurance | 11.8 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 22.1 | |

| Self‐pay | 0.7 | 0.0 | 6.5 | NR* | |

| Income quartile† | |||||

| I | 19.9 | 45.4 | 29.5 | 16.2 | <0.01 |

| II | 25.6 | 29.9 | 19.7 | 17.6 | |

| III | 30.2 | 15.5 | 24.6 | 26.5 | |

| IV | 24.3 | 9.3 | 26.2 | 39.7 | |

| Hospital characteristics | |||||

| Location/teaching status | |||||

| Rural | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.67 |

| Urban nonteaching | 5.3 | 5.0 | 8.9 | NR* | |

| Urban teaching | 93.9 | 95.0 | 90.1 | 98.6 | |

| Bed size‡ | |||||

| Small | 7.4 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 0.30 |

| Medium | 14.8 | 10.9 | 23.8 | 10.1 | |

| Large | 77.7 | 83.2 | 68.3 | 84.1 | |

| Region | |||||

| Northeast | 20.1 | 12.9 | 17.5 | 27.5 | <0.01 |

| Midwest | 24.3 | 20.8 | 7.9 | 4.3 | |

| South | 32.6 | 55.4 | 34.9 | 20.3 | |

| West | 23.0 | 10.9 | 39.7 | 47.8 | |

| Elective admission | 69.2 | 67.3 | 77.4 | 59.4 | 0.15 |

| Weekend admission | 7.9 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 11.6 | 0.63 |

Data presented as median (interquartile range) or percentage. NR indicates not reportable.

Cell counts <11 are NR per Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project guidelines.

Estimated median household incomes are zip code‐specific, updated annually, and classified into 4 quartiles indicating the poorest to wealthiest populations.

Bed size categories are based on inpatient beds and are specific to the hospital's location and teaching status. A more detailed explanation of all the variables in the National Inpatient Sample, including the specific dollar amounts in each category of median household income and the number of hospital beds in each category, is available online (https://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdde.jsp).

Other race refers to Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Other.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics Stratified by Race and Ethnicity

| Variable | White race (n=3840) | Black race (n=505) | Hispanic ethnicity (n=315) | Other race† (n=345) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elixhauser comorbidity index | 6 (5–8) | 7 (5–8) | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) | 0.07 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 3 (1–4) | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | 0.09 |

| 0 | 4.3 | NR* | NR* | 8.7 | 0.44 |

| 1 | 21.2 | 18.8 | 30.2 | 24.6 | |

| 2 | 19.0 | 19.8 | 17.5 | 18.8 | |

| ≥3 | 55.5 | 59.4 | 49.2 | 47.8 | |

| Individual comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes | 24.7 | 31.7 | 33.3 | 36.2 | 0.05 |

| Hypertension | 82.6 | 87.1 | 85.7 | 81.2 | 0.60 |

| Dyslipidemia | 62.1 | 52.5 | 52.4 | 46.4 | 0.01 |

| Nicotine/tobacco use | 33.9 | 42.6 | 30.2 | 23.2 | 0.06 |

| Alcohol abuse | 2.3 | 3.0 | NR* | NR* | 0.89 |

| Drug abuse | 1.7 | 5.0 | NR* | NR* | 0.17 |

| Obesity | 12.8 | 15.8 | 14.3 | 4.3 | 0.13 |

| Coronary artery disease | 60.5 | 47.5 | 50.8 | 46.4 | <0.01 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 21.7 | 27.7 | 12.7 | 10.1 | 0.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 66.5 | 52.5 | 49.2 | 63.8 | <0.01 |

| Congestive heart failure | 88.0 | 91.1 | 87.3 | 76.8 | 0.03 |

| Renal failure | 37.2 | 47.5 | 33.3 | 34.8 | 0.18 |

| Dialysis dependent | 2.9 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 4.3 | <0.01 |

| Liver disease | 8.9 | 6.9 | 4.8 | 11.6 | 0.47 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 30.6 | 32.7 | 20.6 | 18.8 | 0.08 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 16.0 | 15.8 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 0.15 |

| Coagulopathy | 25.9 | 19.8 | 11.1 | 36.2 | <0.01 |

| Cancer | 3.3 | NR* | 0.0 | NR* | 0.24 |

| Malnutrition | 3.4 | 4.0 | 7.9 | 4.3 | 0.31 |

| Dementia | 1.4 | NR* | NR* | NR* | 0.98 |

| Depression | 10.9 | 8.9 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 0.14 |

| Previous history | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | 10.5 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 10.1 | 0.25 |

| Stroke/TIA | 13.0 | 9.9 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 0.19 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.44 |

| PCI | 11.6 | 3.0 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 0.04 |

| CABG | 26.6 | 13.9 | 15.9 | 20.3 | <0.01 |

| ICD | 8.7 | 15.8 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 0.03 |

| PPM | 16.7 | 6.9 | 15.9 | 20.3 | 0.07 |

Data presented as median (interquartile range) or percentage. Two authors (M.I. and M.A.A.) independently verified the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10) codes that corresponded to each comorbidity (Table S1), and any disagreements in inclusion or exclusion of ICD‐10 codes were discussed with a third individual (N.S.A). CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; NR, not reportable; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPM, permanent pacemaker; and TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Cell counts <11 are NR per Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project guidelines.

Other race refers to Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Other.

In accordance with the HCUP data use agreement, we did not report variables that contained a small number of observed (ie, unweighted) hospitalizations (<11) as this could pose risk of person identification or data privacy violation. 23 Inability to report is denoted by “NR.” A 2‐tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) software, accounting for the NIS sampling design, and were weighted using sampling weights provided with the NIS database to estimate national‐level effects per HCUP‐NIS recommendations. 20 Data were analyzed in November 2022.

Results

Patient and Hospital Characteristics

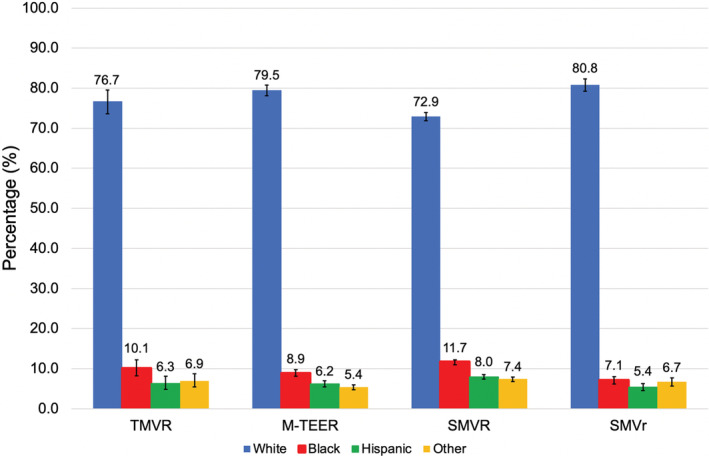

From 2016 through 2020, an estimated 5005 hospitalizations in the United States met inclusion criteria, of which an estimated 3840 (76.7%) were White race, 505 (10.1%) were Black race, 315 (6.3%) were Hispanic ethnicity, and 345 (6.9%) were from another race (Figure 2). The racial and ethnic breakdown of patients undergoing TMVR, M‐TEER, surgical mitral valve replacement, and surgical mitral valve repair is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Racial and ethnic breakdown of patients undergoing transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR), mitral transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (M‐TEER), surgical mitral valve replacement (SMVR), and surgical mitral valve repair (SMVr) in the United States from 2016 through 2020.

Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Black patients undergoing TMVR were younger and more likely to be women compared with other racial and ethnic groups (both P<0.01). White patients had the highest rates of dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation/flutter, and history of percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting, whereas Black patients had the highest rates of peripheral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, dialysis dependence, and history of implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator (all P<0.01). Differences were also found in the socioeconomic makeup of patients in each racial and ethnic group, with 9.3% of Black patients living in the highest median household income neighborhoods quartile, compared with 24.3% White patients and 26.2% Hispanic patients (P<0.01). Baseline characteristics stratified by race and ethnicity are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

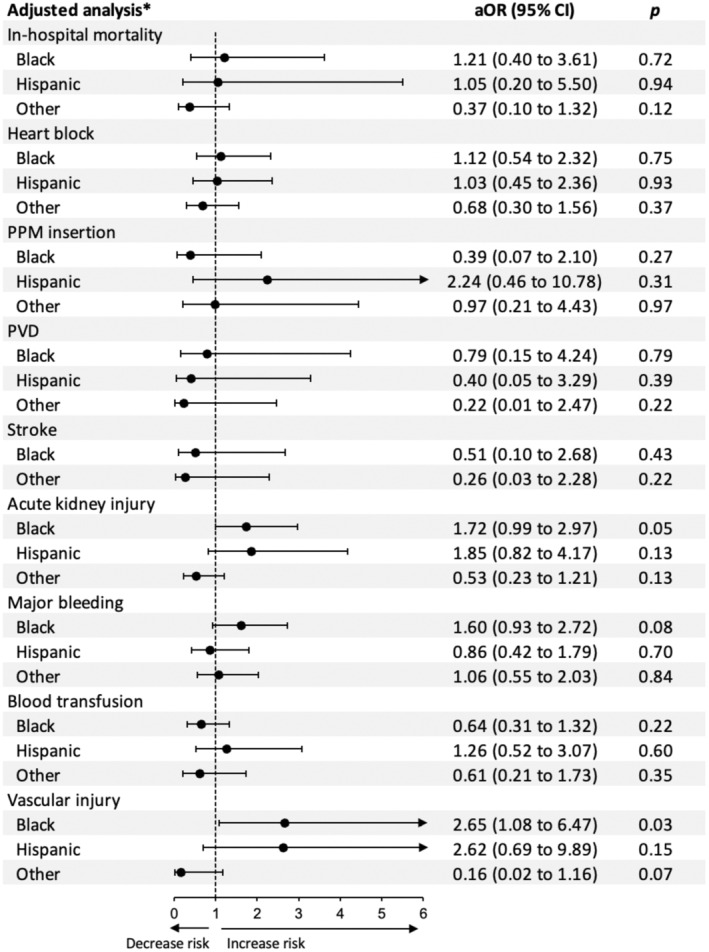

In‐Hospital Outcomes

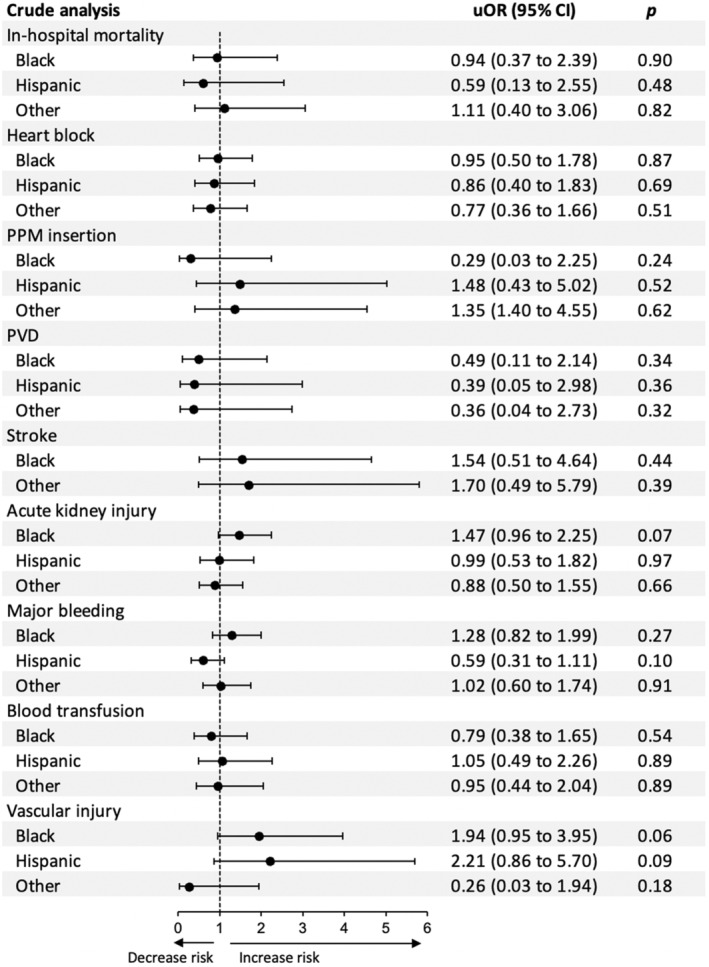

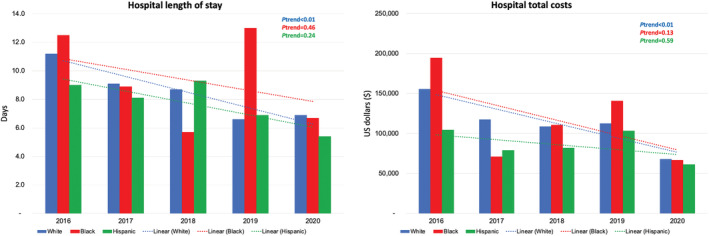

After adjustment for potential confounders using a multivariate regression analysis, Black patients had higher odds of vascular complications (P=0.03) and a tendency toward higher AKI (P=0.05) compared with White patients. On the other hand, Hispanic patients had similar odds of vascular complications and AKI compared with White patients (both P>0.1). Black and Hispanic patients had similar odds of in‐hospital mortality, heart block, PPM insertion, prosthetic valve dysfunction, major bleeding, and blood transfusion compared with White patients (all P>0.05).

The median hospital LOS was similar between White, Black, and Hispanic patients (5 versus 6 versus 3 days; P=0.12). Likewise, median total costs were similar between the 3 racial and ethnic groups ($66 424 versus $69 921 versus $61 419; P=0.71). In‐hospital outcomes stratified by race and ethnicity are shown in Table 3 and in Figures 4 and 5.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Primary and Secondary In‐Hospital Outcomes Stratified by Race and Ethnicity

| Variable | White race (n=3840) | Black race (n=505) | Hispanic ethnicity (n=315) | Other race† (n=345) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 5.2 | 5.0 | NR* | 5.8 | 0.89 |

| Complications | |||||

| Heart block | 14.5 | 13.9 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 0.91 |

| Permanent pacemaker | 3.3 | NR* | 4.8 | 4.3 | 0.49 |

| Prosthetic valve dysfunction | 3.9 | NR* | NR* | NR* | 0.45 |

| Stroke | 2.6 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 0.37 |

| Acute kidney injury | 24.0 | 31.7 | 23.8 | 21.7 | 0.32 |

| Major bleeding | 28.4 | 33.7 | 19.0 | 29.0 | 0.23 |

| Blood transfusion | 12.1 | 9.9 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 0.92 |

| Vascular injury | 5.3 | 8.9 | 10.1 | NR* | 0.07 |

| Discharge disposition | |||||

| Routine | 56.1 | 51.5 | 69.8 | 60.9 | 0.46 |

| Transfer to short‐term care hospital | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NR* | |

| Transfer to SNF or ICF | 14.2 | 10.9 | 7.9 | 10.1 | |

| Home health care | 23.9 | 32.7 | 19.0 | 21.7 | |

| Died | 5.2 | 5.0 | NR* | 5.8 | |

| Resource use | |||||

| LOS, d | 5 (2–10) | 6 (2–12) | 3 (2–8) | 7 (3–12) | 0.12 |

| Hospital cost, $ | 66 424 (43 733–110 223) | 69 921 (50 107–107 820) | 61 419 (48 323–108 574) | 70 207 (51 985–103 197) | 0.71 |

Data presented as median (interquartile range) or percentage. ICF indicates intermediate care facility; LOS, length of stay; NR, not reportable; and SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Cell counts <11 are NR per Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project guidelines.

Other race refers to Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Other.

Figure 4. Forest plots for the unadjusted outcomes following transcatheter mitral valve replacement in Black and Hispanic patients compared with White patients (reference).

PPM indicates permanent pacemaker; PVD, prosthetic valve dysfunction; and uOR, unadjusted odds ratio.

Figure 5. Forest plots for the adjusted outcomes following transcatheter mitral valve replacement in Black and Hispanic patients compared with White patients (reference).

*The multivariate regression model is adjusted for age, sex, insurance, income, hospital location and teaching status, bed size, region, type of admission, Elixhauser and Charlson index scores, and relevant comorbidities. aOR indicates adjusted odds ratio; PPM, permanent pacemaker; and PVD, prosthetic valve dysfunction.

Predictors of In‐Hospital Mortality Among Patients Undergoing TMVR

In a multivariate analysis, factors independently associated with increased in‐hospital mortality in patients undergoing TMVR were older age (>85 years) (adjusted OR, 6.75 [95% CI, 2.13–21.42]) and liver disease (adjusted OR, 18.51 [95% CI, 9.25–37.05]). Atrial fibrillation/flutter was associated with lower in‐hospital mortality (adjusted OR, 0.46 [95% CI, 0.24–0.88]) (Table 4). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.81 (Figure S1).

Table 4.

Multivariate Regression Analysis With Adjusted ORs for All‐Cause In‐Hospital Mortality

| Variable | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| 18–64 | Reference | … |

| 65–74 | 2.56 (0.89–7.35) | 0.07 |

| 75–84 | 3.08 (1.2–7.88) | 0.01 |

| >85 | 6.75 (2.13–21.42) | <0.01 |

| Female sex | 1.46 (0.76–2.82) | 0.25 |

| Insurance | ||

| Medicare | Reference | … |

| Medicaid | 0.53 (0.11–2.56) | 0.43 |

| Private insurance | 1.54 (0.62–3.83) | 0.34 |

| Income quartile | ||

| I | Reference | … |

| II | 1.12 (0.48–2.59) | 0.78 |

| III | 0.76 (0.27–2.15) | 0.61 |

| IV | 1.27 (0.51–3.15) | 0.60 |

| Region | ||

| Northwest | Reference | … |

| Midwest | 0.79 (0.27–2.30) | 0.68 |

| South | 1.00 (0.43–2.31) | 0.99 |

| West | 1.19 (0.49–2.91) | 0.68 |

| Dementia | 4.19 (0.95–18.32) | 0.05 |

| Cancer | 1.50 (0.26–8.54) | 0.64 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.21 (0.42–3.52) | 0.71 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.80 (0.41–1.56) | 0.52 |

| Renal failure | 0.90 (0.44–1.84) | 0.78 |

| Liver disease | 18.51 (9.25–37.05) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes | 0.64 (0.31–1.34) | 0.24 |

| Hypertension | 0.88 (0.40–1.92) | 0.75 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.98 (0.50–1.90) | 0.96 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 0.46 (0.24–0.88) | 0.01 |

All ORs are adjusted for the other covariates listed. ORs >1 indicate greater odds of all‐cause in‐hospital mortality.

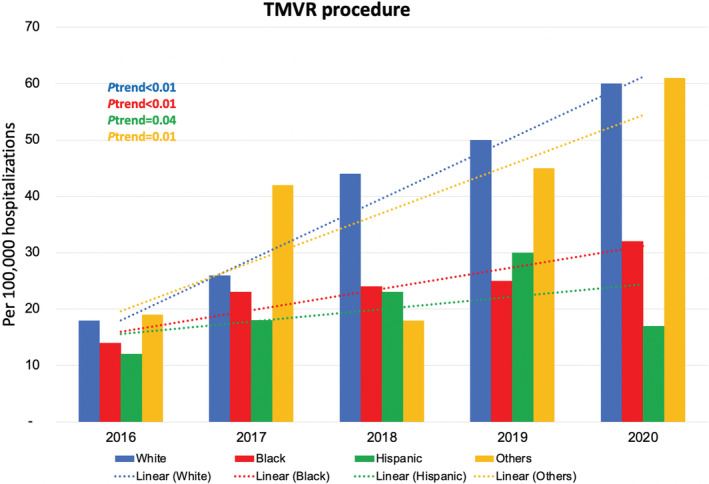

Temporal Trends

From 2016 to 2020, the number of TMVR hospitalizations per 100 000 admissions increased significantly from 14 to 60 in White patients, from 14 to 32 in Black patients, from 12 to 17 in Hispanic patients, and from 19 to 61 in other racial groups (all P trend<0.05). Over the study period, there was a nonsignificant reduction in LOS in Black patients (12.5 days in 2016 to 6.7 days in 2020; P trend=0.46) and Hispanic patients (9.0 days in 2016 to 5.4 days in 2020; P trend=0.24) and a significant reduction in LOS in White patients (11.2 days in 2016 to 6.9 days in 2020; P trend<0.01). From 2016 to 2020, there was a nonsignificant reduction in total costs in Black patients ($194 773 to $66 871; P trend=0.13) and Hispanic patients ($104 397 to $61 347; P trend=0.59) and a significant reduction in total costs in White patients ($155 827 in 2016 to $67 956 in 2020; P trend<0.01). Annual trends for TMVR hospitalizations, hospital LOS, and total costs are shown in Figures 6 and 7.

Figure 6. Year‐over‐year trend in the number of hospitalizations for transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) in the United States in different racial and ethnic groups from 2016 through 2020.

Figure 7. Year‐over‐year trend in the hospital length of stay and total costs in different racial and ethnic groups from 2016 through 2020.

Discussion

TMVR has developed as a therapy for patients with degenerated mitral bioprosthesis. 24 , 25 We report racial and ethnic disparities, and many similarities, in patients undergoing TMVR. This large study analyzed the NIS to produce several novel findings: (1) among patients undergoing TMVR, Black patients were significantly younger and more likely to be women compared with White, Hispanic, and other racial groups; (2) in‐hospital mortality following TMVR was similar across different racial and ethnic groups; (3) compared with White patients, Black and Hispanic patients had similar procedural complication rates, including heart block requiring PPM, prosthetic valve dysfunction, stroke, AKI, and major bleeding requiring blood transfusion; (4) compared with White patients, Black and Hispanic patients had similar hospital LOS and total costs; and (5) TMVR use increased significantly from 2016 to 2020 across all racial and ethnic groups.

Development of TMVR

M‐TEER emerged as a new paradigm for the treatment of MVD in patients with high surgical risk. 7 The COAPT (Cardiovascular Outcomes Assessment of the MitraClip Percutaneous Therapy for Heart Failure Patients with Functional Mitral Regurgitation) trial demonstrated lower mortality and heart failure hospitalization in patients with functional MR treated with M‐TEER compared with medical therapy. 26 , 27 Subsequently, the 2020 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and 2021 European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery guidelines recommended M‐TEER as an alternative to surgery in patients with high surgical risk. 1 , 2 However, M‐TEER has limited applicability to certain mitral valve anatomical features, including mitral annular calcification and short posterior mitral leaflets, and does not prevent the progression of MR over time. 24 Thus, TMVR with SAPIEN 3 valves was developed to overcome these limitations and subsequently received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2017 for patients with degenerated mitral bioprostheses. 24 , 25 , 28 Multiple trials evaluating the feasibility of TMVR in patients with mitral annular calcification are ongoing, including APOLLO (Trancatheter Mitral Valve Replacement with the Medtronic IntrepidTM TMVR System in Patients with Severe Symptomatic Mitral Regurgitation, NCT03242642) and ENCIRCLE (SAPEIN M3 System Transcatheter Mitral Valve Replacement Via Transseptal Access, NCT04153292).

Patient Profiles

Among patients undergoing TMVR, 10.1% were Black race, which is slightly higher than the percentage of Black patients receiving M‐TEER (8.9%) and close to their relative percentage in the US population (12.6% in 2020). However, only 6.3% of patients undergoing TMVR were Hispanic ethnicity, which is similar to the percentage of Hispanic patients receiving M‐TEER (6.2%), reflecting on their significant underrepresentation compared with their relative percentage in the US population (18.7% in 2020). Similar to M‐TEER, White patients undergoing TMVR were significantly older and less likely to be women compared with Black, Hispanic, and other race groups. 16 Likewise, White patients undergoing surgical mitral valve interventions were older and less likely to be women based on prior data. 12 , 13 , 29 Collectively, these findings could suggest that Black patients have accelerated mitral valve disease and require intervention at younger ages. Congruent with this hypothesis and similar to M‐TEER, 16 Black patients undergoing TMVR had a higher incidence of chronic kidney disease, which has been associated with progression of degenerative mitral valve disease in previous reports. 12 , 30 Alternatively, perhaps mitral valve interventions are less frequently offered to older, sicker Black patients compared with White patients.

In‐Hospital Mortality and Complications

Despite the distinctly different clinical risk profiles, as illustrated in Tables 1 and 2, our study found no significant differences between White, Black, Hispanic, and other races in in‐hospital mortality and most procedural complications following TMVR, including heart block requiring PPM, prosthetic valve dysfunction, stroke, AKI, and major bleeding requiring blood transfusion. In contrast, in a study evaluating racial disparities in patients undergoing M‐TEER, White patients had higher in‐hospital mortality (4.7% versus 1.6%), cardiac arrest (3.1% versus 0.8%), and pacemaker insertion (0.8% versus 0%) compared with Black patients (all P<0.01). 16 The reasons for the worse in‐hospital outcomes among White patients in that study are unclear, but hypothesized causes include the following: (1) more conservative selection of Black patients for M‐TEER, as reflected by the significant discrepancy in age and sex between White and Black patients 16 ; (2) higher rates of degenerative (primary) MVD in White compared with Black patients among patients with significant MVD referred to surgical intervention (84.8% versus 62.5%), as demonstrated by DiGiorgi et al 29 ; and (3) differences in risk profile among White and Black patients with significant MVD, as suggested in previous studies. 13 , 29

LOS and Hospital Cost

Our analysis showed that adjusted LOS and hospital costs were similar in Black and Hispanic patients compared with White patients. Similarly, in a study by Alqahtani et al that evaluated racial disparities in patients undergoing TAVR, there were no differences in LOS (9±8 versus 9±8 days; P=0.99) and cost of hospitalization ($58 632±$32 138 versus $58 660±$29 110; P=0.99) between White and Black patients, respectively, confirming similar patterns of resource use among White and Black patients undergoing TAVR. 14 In contrast, previous studies that evaluated racial disparities in patients undergoing M‐TEER, surgical mitral valve replacement, and surgical aortic valve replacement demonstrated longer LOS in Black compared with White patients. 12 , 16 Such findings have important cost implications and warrant further evaluation in future research.

Trends in TMVR Use

In contrast to TAVR and M‐TEER, TMVR is a relatively new procedure, born in 2009 and approved in the United States only in 2017. 7 , 31 There was a significant increase in the use of TMVR from 2016 to 2020 across all racial and ethnic groups and in both sexes. 32 Similarly, previous studies found an upward trend in other transcatheter valvular procedures in White and Black patients. 16 , 33 Elbadawi et al found that M‐TEER was increasingly performed in both White and Black patients at similar rates. 16 Ullah et al also found a statistically significant linear uptrend in the use of TAVR in patients of all races between the years 2011 and 2015, 33 with similar rates of TAVR documented between White and Black patients. 14

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. First, racial and ethnic demographics are often self‐described, self‐reported, or entered by a clerk, and their ascertainment based on personal identification is not universally performed. Hence, chances of errors in allocation of patients to different racial and ethnic categories cannot be excluded. Second, in a retrospective NIS study using administrative claims codes, incorrect coding could lead to inaccurate data. Third, the retrospective nature of the study makes it subject to inherent selection bias. Fourth, some outcomes and demographic/clinical characteristics were not available per the HCUP data use agreement because patient counts were <11. Fifth, validated risk scores, such as the society of thoracic surgeons, are not captured by the NIS, limiting patient risk assessment. Sixth, detailed baseline and procedural characteristics, such as cause of MR, echocardiographic data, indication for TMVR, access type, valve size, delivery device type, valve anatomy, postprocedure residual MR, and postprocedural medications, were unavailable, which can lead to unmeasured bias. Seventh, NIS allows detailed assessment of in‐hospital outcomes but does not include long‐term clinical outcomes beyond discharge. Studies exploring the long‐term racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes of TMVR are still needed.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our study adds meaningfully by describing racial and ethnic disparities among patients undergoing TMVR and the notable lack of outcomes disparities. The NIS is well validated for outcomes studies like ours and undergoes serial data accuracy checks and quality control. In addition, the NIS data are geographically diverse, including a nationally representative sample of centers and operators, and hence reliably demonstrate real‐world practice and outcomes.

Conclusions

Between 2016 and 2020, Black and Hispanic patients undergoing TMVR had similar in‐hospital outcomes compared with White patients, with the exception of higher vascular complications in Black patients. Further comparative studies of TMVR in clinically similar White patients and other racial and ethnic groups are warranted to confirm our findings.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S2

Figure S1

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.122.028999

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 13.

References

- 1. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP III, Gentile F, Jneid H, Krieger EV, Mack M, McLeod C, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143:e35–e71. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, Capodanno D, Conradi L, De Bonis M, De Paulis R, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561–632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coffey S, Cairns BJ, Iung B. The modern epidemiology of heart valve disease. Heart. 2016;102:75–85. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez‐Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population‐based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69208-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goel SS, Bajaj N, Aggarwal B, Gupta S, Poddar KL, Ige M, Bdair H, Anabtawi A, Rahim S, Whitlow PL, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of unoperated patients with severe symptomatic mitral regurgitation and heart failure: comprehensive analysis to determine the potential role of MitraClip for this unmet need. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:185–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Del Trigo M, Rodés‐Cabau J. Transcatheter structural heart interventions for the treatment of chronic heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e001943. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Backer O, Piazza N, Banai S, Lutter G, Maisano F, Herrmann HC, Franzen OW, Søndergaard L. Percutaneous transcatheter mitral valve replacement: an overview of devices in preclinical and early clinical evaluation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:400–409. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gaglia MA Jr, Steinberg DH, Pinto Slottow TL, Roy PK, Bonello L, Delabriolle A, Lemesle G, Okabe T, Torguson R, Kaneshige K, et al. Racial disparities in outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention with drug‐eluting stents. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burton BN, Munir NA, Labastide AS, Sanchez RA, Gabriel RA. An update on racial disparities with 30‐day outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft under the Affordable Care Act. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33:1890–1898. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rangrass G, Ghaferi AA, Dimick JB. Explaining racial disparities in outcomes after cardiac surgery: the role of hospital quality. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:223–227. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yeung M, Kerrigan J, Sodhi S, Huang PH, Novak E, Maniar H, Zajarias A. Racial differences in rates of aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:991–995. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taylor NE, O'Brien S, Edwards FH, Peterson ED, Bridges CR. Relationship between race and mortality and morbidity after valve replacement surgery. Circulation. 2005;111:1305–1312. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157737.92938.D8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vassileva C, Markwell S, Boley T, Hazelrigg S. Impact of race on mitral procedure selection and short‐term outcomes of patients undergoing mitral valve surgery. Heart Surg Forum. 2011;14:E221. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20101124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alqahtani F, Aljohani S, Almustafa A, Alhijji M, Ali O, Holmes DR, Alkhouli M. Comparative outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in African American and Caucasian patients with severe aortic stenosis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91:932–937. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alkhouli M, Holmes DR Jr, Carroll JD, Li Z, Inohara T, Kosinski AS, Szerlip M, Thourani VH, Mack MJ, Vemulapalli S. Racial disparities in the utilization and outcomes of TAVR: TVT Registry report. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:936–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Elbadawi A, Mahmoud K, Elgendy IY, Elzeneini M, Megaly M, Ogunbayo G, Omer MA, Albert M, Kapadia S, Jneid H. Racial disparities in the utilization and outcomes of transcatheter mitral valve repair: insights from a national database. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:1425–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Overview of the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) . Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Accessed November 2, 2022. https://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp

- 18. World Health Organization . International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9), Clinical Modification. World Health Organization; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization . International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10), Clinical Modification. World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khera R, Angraal S, Couch T, Welsh JW, Nallamothu BK, Girotra S, Chan PS, Krumholz HM. Adherence to methodological standards in research using the National Inpatient Sample. JAMA. 2017;318:2011–2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. NIS description of data elements. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Accessed November 2, 2022. https://hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/db/vars/race/nisnote.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 22. United States bureau of labor statistics . CPI inflation calculator. United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm [Google Scholar]

- 23. Data use agreement for the nationwide databases from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) . Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Accessed November 2, 2022. https://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/team/NationwideDUA.jsp

- 24. Alperi A, Granada JF, Bernier M, Dagenais F, Rodés‐Cabau J. Current status and future prospects of transcatheter mitral valve replacement: JACC state‐of‐the‐art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:3058–3078. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. FDA expands use of Sapien 3 artificial heart valve for high‐risk patients. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news‐events/press‐announcements/fda‐expands‐use‐sapien‐3‐artificial‐heart‐valve‐high‐risk‐patients [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stone GW, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, Kar S, Lim DS, Mishell JM, Whisenant B, Grayburn PA, Rinaldi M, Kapadia SR, et al. Transcatheter mitral‐valve repair in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2307–2318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mack MJ, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, Kar S, Lim DS, Mishell JM, Whisenant BK, Grayburn PA, Rinaldi MJ, Kapadia SR, et al. 3‐year outcomes of transcatheter mitral valve repair in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guerrero M, Dvir D, Himbert D, Urena M, Eleid M, Wang DD, Greenbaum A, Mahadevan VS, Holzhey D, O'Hair D, et al. Transcatheter mitral valve replacement in native mitral valve disease with severe mitral annular calcification: results from the first multicenter global registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:1361–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DiGiorgi PL, Baumann FG, O'Leary AM, Schwartz CF, Grossi EA, Ribakove GH, Colvin SB, Galloway AC, Grau JB. Mitral valve disease presentation and surgical outcome in African‐American patients compared with white patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Umana E, Ahmed W, Alpert MA. Valvular and perivalvular abnormalities in endstage renal disease. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325:237–242. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200304000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheung A, Webb JG, Wong DR, Ye J, Masson JB, Carere RG, Lichtenstein SV. Transapical transcatheter mitral valve‐in‐valve implantation in a human. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:e18–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ismayl M, Machanahalli Balakrishna A, Fahmy MM, Thandra A, Gill GS, Niu F, Agarwal H, Aboeata A, Goldsweig AM, Smer A. Impact of sex on in‐hospital mortality and 90‐day readmissions in patients undergoing transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR): analysis from the nationwide readmission database. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;8:407–416. doi: 10.1002/ccd.30549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ullah W, Al‐Khadra Y, Mir T, Darmoch F, Pacha HM, Sattar Y, Ijioma N, Mohamed MO, Kwok CS, Asfour AI, et al. Temporal trends in utilization and outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in different races: an analysis of the National Inpatient Sample. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2021;22:586–593. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000001172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S2

Figure S1