Abstract

Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) are mobile genetic elements that can transfer by conjugation to recipient cells. Some ICEs integrate into a unique site in the genome of their hosts. We studied quantitatively the process by which an ICE searches for its unique integration site in the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. We followed the motion of both ICEBs1 and the chromosomal integration site in real time within individual cells. ICEBs1 exhibited a wide spectrum of dynamical behaviors, ranging from rapid sub-diffusive displacements crisscrossing the cell, to kinetically trapped states. The chromosomal integration site moved sub-diffusively and exhibited pronounced dynamical asymmetry between longitudinal and transversal motions, highlighting the role of chromosomal structure and the heterogeneity of the bacterial interior in the search. The successful search for and subsequent recombination into the integration site is a key step in the acquisition of integrating mobile genetic elements. Our findings provide new insights into intracellular transport processes involving large DNA molecules.

INTRODUCTION

Conjugation is a horizontal gene transfer process that contributes significantly to the generation of genetic diversity in bacteria (1). During conjugation, or mating, DNA is transferred directly from a donor bacterial cell to a recipient. There are two types of conjugative elements, plasmids and integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs). Whereas plasmids are extrachromosomal, ICEs reside integrated in the chromosome of a host cell. As a potent force of bacterial evolution, conjugation has played a fundamental role in organizing the genetic information on chromosomes, distributing genes involved in processes such as pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance and metabolism (2,3).

Although stably maintained integrated in the host chromosome, ICEs can excise from the chromosome to form a circular DNA that can then transfer from a donor cell to a recipient where it is first extrachromosomal but then integrates into the chromosome of the new host to form a stable transconjugant. Many ICEs integrate into a specific, often unique site in the bacterial chromosome. Locating and integrating into the proper site is an essential step in the lifecycle of these widespread elements, yet nothing is known about how an ICE locates the proper integration site.

ICEBs1 is a relatively small ICE (∼20 kb) found in the chromosome of Bacillus subtilis (4,5). It integrates into a preferred attachment site, attB, located in a tRNA gene (trnS-leu2). In the absence of its normal attachment (integration) site, ICEBs1 can integrate into secondary sites with reduced frequency, and integration into these secondary sites is detrimental to both the element and its bacterial host (6), highlighting the importance of locating the proper site for integration.

The search for attB by ICEBs1 belongs to a general class of search problems that are ubiquitous in many biological contexts, ranging from the search for cognate sites by transcription factors (7,8), the repair of DNA lesions (9), to horizontal gene transfer processes other than conjugation (10) and the RNA-guided search of specific sequences by CRISPR (11,12). Common to all these processes is the search for a short ∼10–20 bp-long target site along a ∼1 to >5 Mb-long chromosome, within the complex and crowded bacterial cytoplasm (13). Several investigations have provided evidence supporting the notion that the cytoplasm is a non-equilibrium active medium in which fluctuations are primarily metabolic, driven by ATP and GTP usage (14,15). The in vivo search mechanisms allowing an ICE to locate its integration site in a transconjugant are largely unknown.

Here, we focus on the quantitative characterization of the in vivo dynamics of both ICEBs1 and its integration site attB during the search process leading to integration into the chromosome of a transconjugant. We visualize both loci within the same cell in real time by labelling each locus with multiple binding sites for a fluorescent reporter protein, specifically TetR-mApple2 (tetO sites inserted close to the attB site) or LacI-GFP (lacO sites inserted at the ICEBs1), as represented in Supplementary Figure S1 (16). Previous investigations in Escherichia coli revealed that the motion of chromosomal loci is subdiffusive and consistent with fractional Brownian motion (15,17). Moreover, anisotropy between the longitudinal and transversal motions of chromosomal loci has been reported for E. coli (18) and Vibrio cholerae (19), possibly reflecting an underlying structural anisotropy in the bacterial chromosome. Our experimental findings indicate that far from being diffusive, the search is a non-equilibrium, metabolically driven process in which the rapid, sub-diffusive motion of ICEBs1 across the whole cell is punctuated by episodic explorations of local chromosomal regions, until the asymmetrically moving target site (attB) is found and integration takes place. Our results underscore the importance of chromosomal structure in the search, the efficiency of target location within a crowded environment, and heterogeneity as an essential principle in bacterial subcellular behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and growth conditions

Bacillus subtilis strains were grown in LB medium for routine cloning and strain constructions. Strains for experiments were grown in defined S7 minimal salts medium (containing 50 mM MOPS [morpholinepropanesulfonic acid]) supplemented with l-arabinose (1%), phenylalanine (40 μg/ml), tryptophan (40 μg/ml), threonine (200 μg/ml) and methionine (40 μg/ml), as needed. Xylose (1%) was added to induce expression from Pxyl-rapI (all reagents were from Sigma unless specified).

Live-cell imaging and mating conditions

Donors and recipients were colony purified from frozen (−80°C) stocks on LB agar plates with the appropriate antibiotics overnight at 42°C. Cells from a single colony were inoculated into liquid LB medium and grown to an optical density OD600 of ∼0.8 to 1. Cells were then diluted into defined minimal medium with arabinose as the carbon source to an OD600 of ∼0.02. After at least three to four generations (OD600 of ∼0.2), expression of rapI from Pxyl-rapI was induced by addition of xylose to the donors. Cells were grown for another hour, to allow for ICEBs1 gene expression and excision, and then washed three times. Donors and recipients were then mixed at a ratio of ∼1 donor per three recipients at a concentration of ∼108 cells/ml. Five microliters of this mating mix were placed on an agarose pad (low melting 2% agarose dissolved in defined minimal growth medium). The pad was circular with a volume of ∼100 μl and a height of ∼2 mm. Then the pad was laid on top of a MatTek device that has coverslip glass (#1.5) built into a 35 mm dish. The effect of different treatments was studied by addition of 5 μl of 100× stock solutions on top of the agar pad, at 37°C and then tracking cells using fluorescence microscopy. The 100× concentrations of compounds and total times of cell tracking were: Chloramphenicol (50 mg/ml, 30 min); rifampicin (10 mg/ml, 15 min) and 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) (45 mg/ml, 30 min). Time-lapse images were recorded typically between 1–3 h following mating.

Bacterial strains and growth

The B. subtilis strains used are listed in Table 1. All are derivatives of JH642 (20,21). Strains were constructed by standard procedures using natural transformation. New alleles were constructed according to the following and transformed into a clean JH642 or ICEBs1 null JH642 derived strain (JMA222) (22). Alleles were transformed by natural transformation as described into appropriate backgrounds. tetR-mApple was constructed by replacing the yfp coding sequence in pPSL38 (23) with mApple (24) to produce pSAM021. pSAM021 was integrated into the chromosome at cgeD. Diagnostic PCR was used to verify integration by double-crossover. ΔyddS::tetO240 is linked to attB and was constructed by inserting the tetO array from pLAU44 (25) by restriction digest cloning into the plasmid pSAM221. pSAM221 was constructed by amplifying two fragments from JH642 genomic DNA and the chloramphenicol resistance cassette from pGEMcat (26). Fragments were inserted into digested pUC19 by isothermal assembly reaction generating pSAM308 (27). The plasmid pSAM308 was integrated into the chromosome by double-crossover into yddS and confirmed by diagnostic PCR.

Table 1.

B. subtilis strains used

| Strain | Relevant genotypea (comments) | Fluorescence |

|---|---|---|

| SAM318 (recipient) | ICEBs10 (cured of ICEBs1) ΔyddS::(tetO240 cat; near attB) ΔcgeD::{Ppen(mutTAGG)-tetR-mApple2 tet} ΔamyE::(Ppen-lacI-gfpmut2 spc) | GFP (foci if ICEBs1+); mApple2 (attB) |

| MMB1277 (donor) | ICEBs1 Δ(rapI-yddM)::{lacO (arrays in ICEBs1) kan} amyE::(Pxyl-rapI spc) | None |

| SAM837 | ICEBs1 Δ(rapI-yddM)::{lacO (arrays in ICEBs1) kan} ΔyddS::(tetO240 cat; near attB) ΔcgeD::{tet Ppen(mutTAGG)-tetR-mApple2} ΔamyE::(Ppen-lacI-gfpmut2 spc) | GFP (ICEBs1); mApple2 (attB) |

| SAM049 | ΔcgeD::{tet Ppen(mutTAGG)-tetR-mApple2} 300°::(tetO kan) | mApple2 (300°) |

aAll strains contain the trpC2 pheA1 alleles (not indicated).

Microscopy and image acquisition

The setup consists of an inverted microscope (Nikon, Ti2-Eclipse) with a motorized x–y-stage (Prior). Stage, sample holder and objective (100×/1.45 oil, Nikon) are inside a temperature box (Okolab) at 37°C. Phase contrast and fluorescence images were acquired with a sensitive camera (Andor DU-987), using the NIS-Element Advanced Research software (Nikon, version 5.02.01). An experiment consists of a sequence of images taken from a sample. An image consist of 512 × 512 pixels (px) with a resolution of 109.76 nm/pixel. Images were typically acquired every about 4 s or 30 s over a total time of around 6 min or 45 min. These parameters allowed us to capture essential features of the dynamics while minimizing photo-bleaching. Cells were illuminated with light of the appropriate wavelength, produced by a light emitting diode set (CoolLED pE-4000), using appropriate filter sets for each fluorescent reporter: GFP (Chroma, 49002- ET-GFP (FITC/Cy2)) and RFP (Chroma, 49008-ET-mCherry, Texas Red).

Image analysis

Only transconjugants of strain SAM318 that displayed two attB loci and one ICEBs1 were analysed. In the strain in which ICEBs1 was fully integrated (SAM837), two attB foci and two ICEBs1 foci were analysed in each cell. The presence of two foci indicates that that region of the chromosome has already been replicated. All image processing and data analysis were carried out using a MATLAB (MathWorks) algorithm developed in our laboratory. The code aims at finding the trajectories of ICEBs1 and chromosomal attachment sites labeled with fluorophores and characterize their dynamics. NIS-element images were converted to TIFF files and then individual cell segmentation was carried out in phase contrast images to determine the cell boundaries. The algorithm then calculates the center of mass of each cell and its centerline.

ICEBs1 and attB positions were then determined with sub-pixel resolution by fitting a Gaussian plus a constant to pixel clusters above an appropriate threshold within the cell boundaries. Their positions were then determined with respect to the cells’ center of mass, with  being the distance of the locus to the centreline (transversal direction) and

being the distance of the locus to the centreline (transversal direction) and  being the position along the centreline relative to the center of mass (longitudinal direction).

being the position along the centreline relative to the center of mass (longitudinal direction).

RESULTS

Search and location of the integration site attB by ICEBs1 in individual cells

We used fluorescence reporters and microscopy (28), to visualize the appearance of transconjugants after mating donor and recipient strains. Typically, transconjugants could be visualized about one hour following mixing donors and recipients (Figure 1) and the positions of ICEBs1 and attB loci were followed ∼2–4 generations after mixing donors and recipients. The percentage of transconjugants was ∼5%, a mating efficiency that is comparable to previous observations (16).

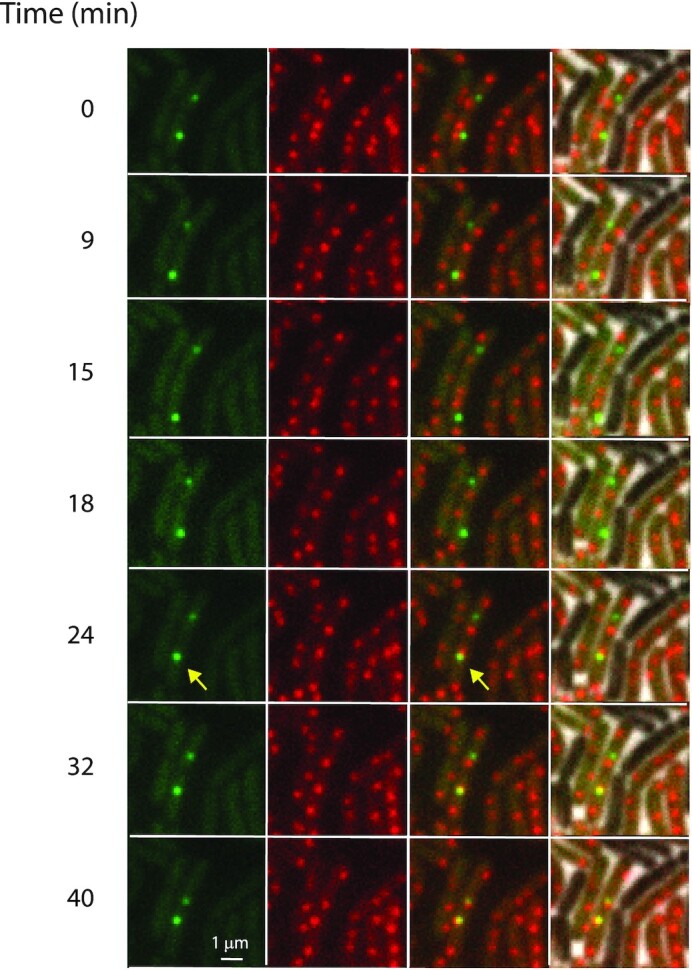

Figure 1.

Search for the chromosomal integration site attB by ICEBs1. First column: snapshots of ICEBs1 labelled with GFP in transconjugant cells at the indicated times (green dots), ∼1 h after mating of MMB1277 as a donor and SAM318 as a recipient (Materials and Methods), with  corresponding to the time at which the first image was recorded; second column: attB labelled with mApple2 (red dots); third column: overlay of GFP (ICEBs1) and mApple2 (attB) images; fourth column: overlay of third column with phase contrast images, showing the presence of non-fluorescent donor cells. Arrows show a moving ICEBs1 that integrates (see also Movie S1). The scale bar represents 1 μm.

corresponding to the time at which the first image was recorded; second column: attB labelled with mApple2 (red dots); third column: overlay of GFP (ICEBs1) and mApple2 (attB) images; fourth column: overlay of third column with phase contrast images, showing the presence of non-fluorescent donor cells. Arrows show a moving ICEBs1 that integrates (see also Movie S1). The scale bar represents 1 μm.

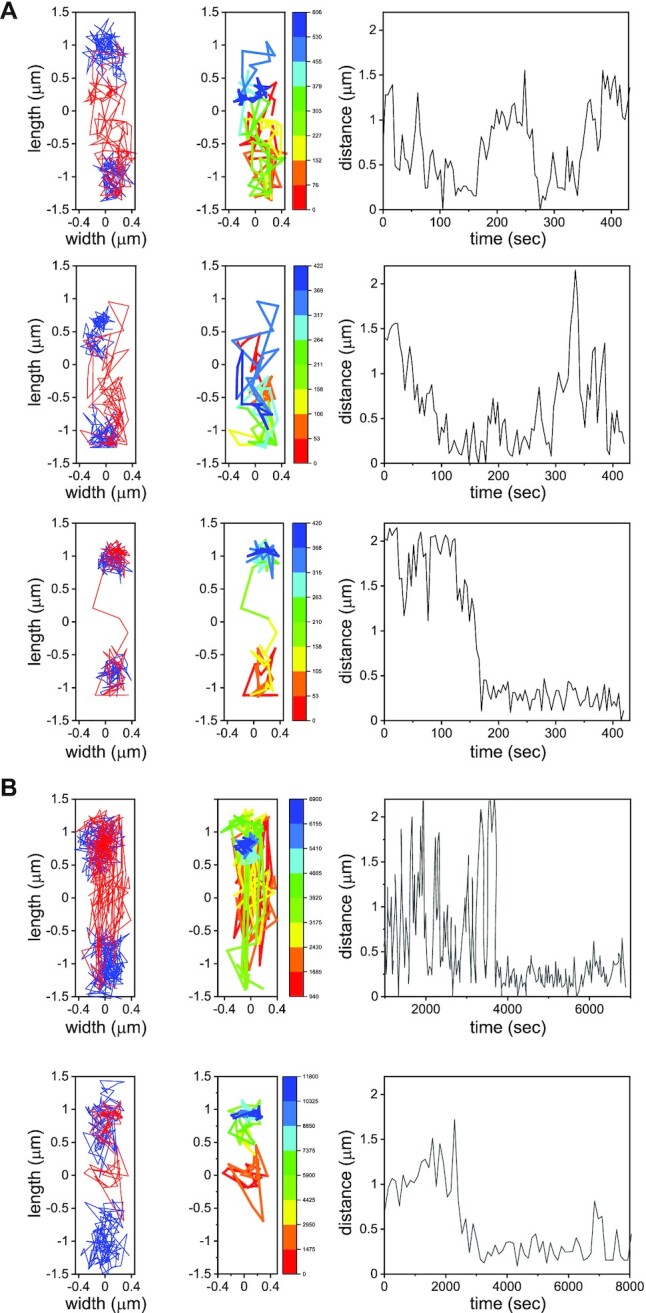

To capture the dynamical characteristics of the search process in the transconjugants, we sampled the motion of ICEBs1 and attB in transconjugant cells at various temporal resolutions (Video 1 illustrates the search and eventual location of an attB locus at a low temporal resolution of 2 min/frame). Two-dimensional trajectories of attB and ICEBs1 in representative cells are shown (Figures 2 and 3) soon after detection of ICEBs1. The behavior of attB trajectories was generally uniform, with two loci (indicative of a partly replicated chromosome) found typically at ¼ and ¾ along the longitudinal axis (Figure 4A). These positions are in accordance with previous observations (29).

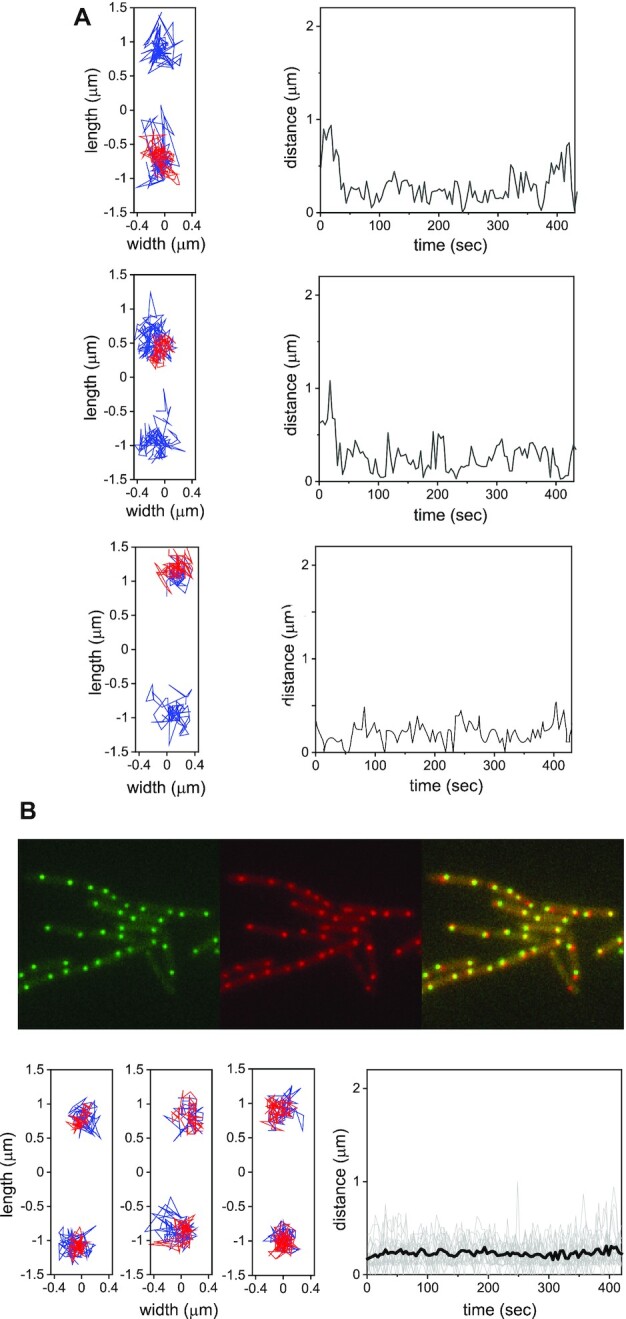

Figure 2.

Trajectories of integrated ICEBs1 in transconjugants. (A) Three representative events of integrated ICEBs1. The left panels show two-dimensional trajectories of attB (blue) and ICEBs1 (red) in transconjugants; the mean interval between successive positions in the trajectories is ∼4 s. Right panels: instantaneous distance between ICEBs1 and the nearest attB as a function of time. (B) Top: fluorescence images of integrated ICEBs1 (green), attB (red) and the overlay in strain SAM837 in which ICEBs1 is integrated and cannot excise. Bottom: left panels show representative two-dimensional trajectories of attB and ICEBs1 in strain SAM837. The right panel shows the instantaneous distance between ICEBs1 and the nearest attB as a function of time for 20 pairs (grey lines) and their mean (black line).

Figure 3.

Target search for attB by ICEBs1. (A) First panels from left to right: Representative two-dimensional trajectories of attB (blue) and ICEBs1 (red) in three transconjugants; the interval between successive positions in the trajectories is ∼4 s. Second panel: ICEBs1 trajectories color-coded according to time. Third panel: distance between ICEBs1 and one of the attB sites (there are two because most cells have a partly replicated chromosome). (B) As in (A), for typical intervals of ∼120 s between frames.

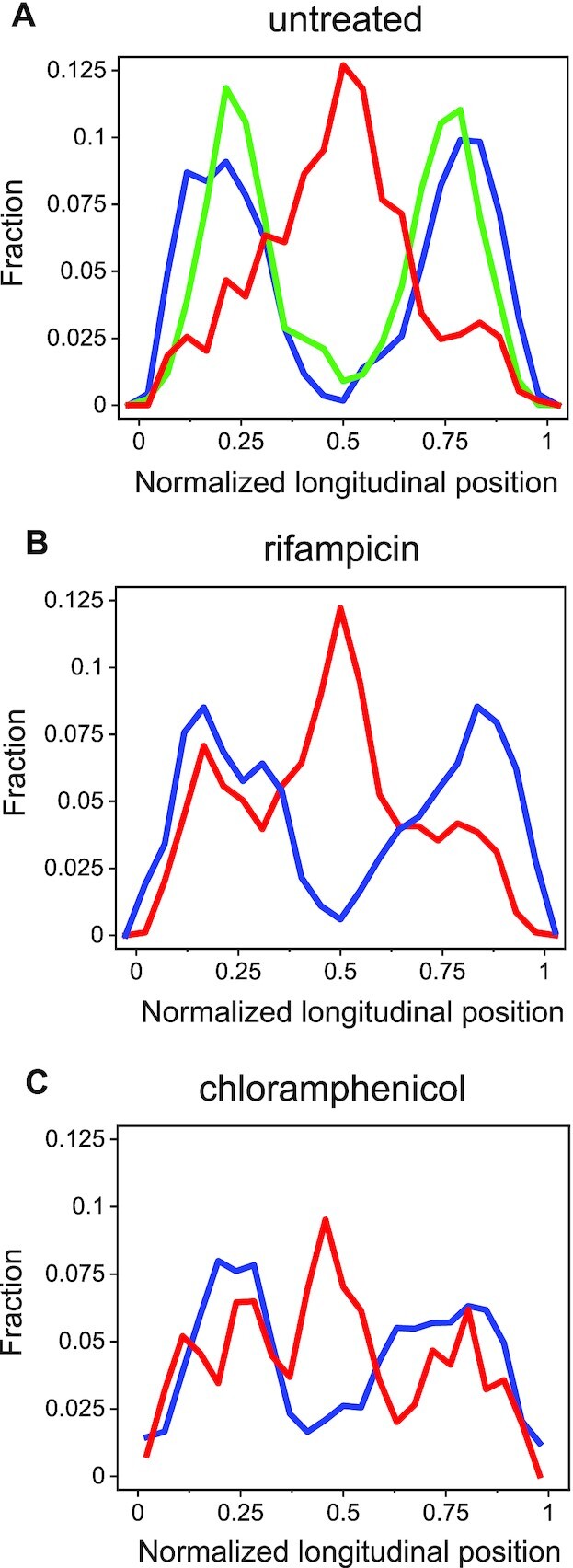

Figure 4.

Position distributions of chromosomal loci and ICEBs1 along the cell's main axis. (A) Distributions of normalized longitudinal positions of a tet array in yddS (∼47°; 13.16 centisomes) near attB (blue, ∼45°; 12.56 centisomes, n = 8040), Supplementary Figure S1) and a tet array in a different chromosomal locus (green, 300°, using SAM049, n = 10 560), and ICEBs1 (red, n = 1134) along a cell's main axis. Only ICEBs1 trajectories whose displacements were >200 nm were included. Longitudinal positions were normalized by the cell length. (B) Same as in (A), but for cells following treatment with rifampicin (red n = 933 and blue n = 3196). (C) Same as in A, but for cells following treatment with chloramphenicol (red n = 7646 and blue n = 5270).

In contrast, ICEBs1s exhibited substantial dynamical heterogeneity: In some cells there was considerable movement of ICEBs1, quite different from that of attB. In the majority of cells, the trajectories of ICEBs1 overlapped considerably with those of attB (Figure 2A). Cells in which ICEBs1 and attB trajectories were similar had likely integrated the element into the chromosome (into attB). Plots of the two-dimensional Euclidean distance between ICEBs1 and attB trajectories with which they overlap are shown in Figure 2A. Note that the distance between fluorescence spots fluctuates around ∼200 nm. To support the notion that such events indeed correspond to integration, we measured the distance between attB and ICEBs1 loci in a strain (SAM837) bearing integrated ICEBs1 that was unable to excise (Figure 2B). The average distance between spots in this strain is indeed ∼200 nm. We surmise that the distance between tandem operator sites labelling attB and ICEBs1s (∼15 kb, Supplementary Figure S1), together with local chromosome de-compaction due to both TetR-mApple2 and LacI-GFP polymerization on the respective tandem operator sites, account for this distance.

About 45 ± 2% (n = 1223) of the total number of transconjugants, displayed mobile behavior without being integrated. These included 14 ± 2% (mean ± SE, n = 868, five independent experiments) that displayed fast motion of ICEBs1 that often spanned a large portion of the cell volume. This fast motion was punctuated by episodes of more compact exploration, until eventual integration at attB (Figure 3). A small group of cells, had ICEBs1 that was kinetically trapped, and the extent of motion of ICEBs1 was significantly reduced (Supplementary Figure S2). Pooling together the longitudinal positions of ICEBs1 that displayed large-scale motion with steps >200 nm (to eliminate elements that had integrated), we calculated the spatial distribution of ICEBs1 along the main cell axis. We found that the distribution of freely moving ICEBs1 peaks at the cell center, and overlaps moderately with the longitudinal distribution of attB loci, allowing ICEBs1 to locate attB (Figure 4A). Note that inhomogeneous molecular distributions in bacterial cells have been reported previously (30). To gain further insights into the mechanisms of search, we characterized quantitatively the motion of each locus separately.

The motion of the target chromosomal integration site attB is anisotropic

As a first step to characterize the dynamics of attB in live cells, we calculated the mean square displacement ( ) of 2D trajectories (Figure 5A), where

) of 2D trajectories (Figure 5A), where  is the position of the locus at time

is the position of the locus at time  , and

, and  is a delay time. A power law fit

is a delay time. A power law fit  of the mean of the

of the mean of the  traces yields

traces yields

, indicating subdiffusive behavior (0<

, indicating subdiffusive behavior (0< <1). Here,

<1). Here,  is an apparent diffusion coefficient and

is an apparent diffusion coefficient and  is a scaling exponent. The value of

is a scaling exponent. The value of  is comparable to those obtained at different chromosomal loci in E. coli (15,17,31). B. subtilis is a rod-shaped bacterium that grows along its longitudinal (y) axis and divides by binary fission. This structure has important functional implications for the organization of its chromosome and the segregation of copies into daughter cells (32,33). We inquired how this built-in asymmetry between length and width manifests itself in the motion of attB and ICEBs1, prior to integration. To this end, we calculated separately the mean square displacement along the longitudinal (

is comparable to those obtained at different chromosomal loci in E. coli (15,17,31). B. subtilis is a rod-shaped bacterium that grows along its longitudinal (y) axis and divides by binary fission. This structure has important functional implications for the organization of its chromosome and the segregation of copies into daughter cells (32,33). We inquired how this built-in asymmetry between length and width manifests itself in the motion of attB and ICEBs1, prior to integration. To this end, we calculated separately the mean square displacement along the longitudinal ( ) and transversal (

) and transversal ( ) directions (

) directions ( and

and  respectively), from data taken at a ∼4 s intervals (n = 60, Figure 5B). Fitting these with a power law dependence, we obtained a ∼1.7-fold difference between

respectively), from data taken at a ∼4 s intervals (n = 60, Figure 5B). Fitting these with a power law dependence, we obtained a ∼1.7-fold difference between  (0.426 ± 0.022) and

(0.426 ± 0.022) and  (0.247 ± 0.005), i.e. asymmetric behavior. Bacterial growth as measured by the cell length for the duration and conditions of the experimental runs is negligible: the relative change in length is 0.06 ± 0.03% (mean ± SE, 100 cells). Boundary effects are also negligible in both directions. Indeed, single realizations of the mean square displacements (shown in gray in Figure 5) do not exhibit a transition to a plateau, as it would be expected for sub-diffusion in a bounded environment (34). We note that the sub-diffusive behavior of integrated ICEBs1 is similar to that of attB loci measured in the same cells (Supplementary Figure S3).

(0.247 ± 0.005), i.e. asymmetric behavior. Bacterial growth as measured by the cell length for the duration and conditions of the experimental runs is negligible: the relative change in length is 0.06 ± 0.03% (mean ± SE, 100 cells). Boundary effects are also negligible in both directions. Indeed, single realizations of the mean square displacements (shown in gray in Figure 5) do not exhibit a transition to a plateau, as it would be expected for sub-diffusion in a bounded environment (34). We note that the sub-diffusive behavior of integrated ICEBs1 is similar to that of attB loci measured in the same cells (Supplementary Figure S3).

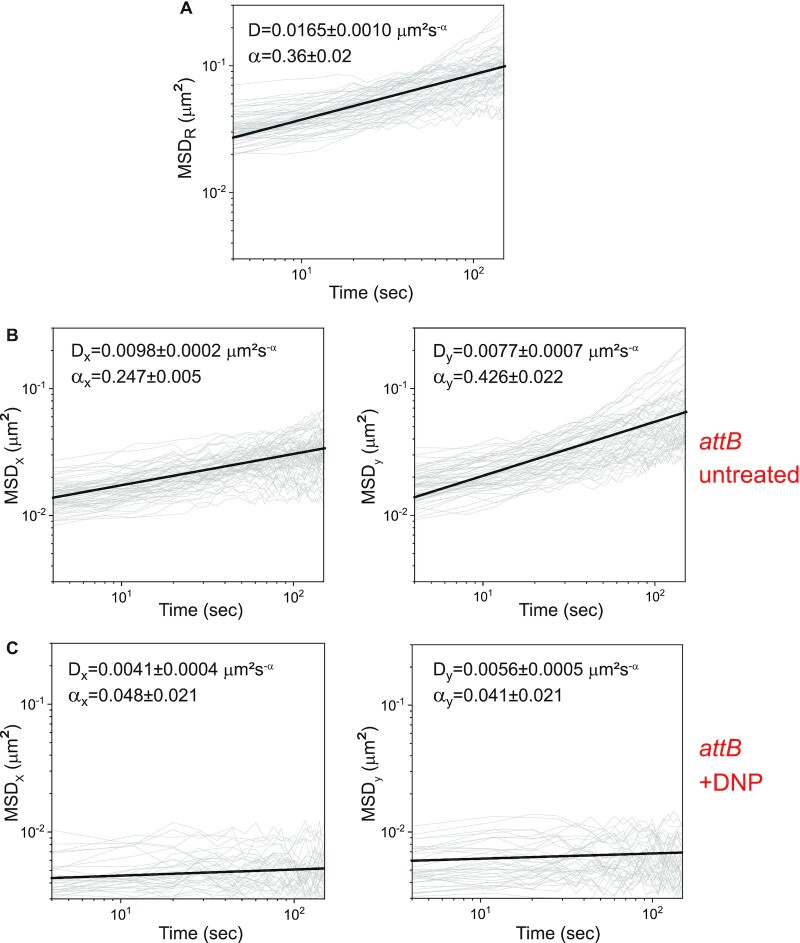

Figure 5.

Anisotropic mean square displacement of attB. (A) Time-averaged mean square displacement  of individual two-dimensional trajectories of attB (grey, n = 59). (B) Time-averaged mean squared displacement in the transversal (left panel) and longitudinal (right panel) directions (

of individual two-dimensional trajectories of attB (grey, n = 59). (B) Time-averaged mean squared displacement in the transversal (left panel) and longitudinal (right panel) directions ( and

and respectively) of individual trajectories of attB (gray, n = 59). The effective diffusion coefficient

respectively) of individual trajectories of attB (gray, n = 59). The effective diffusion coefficient  and exponent

and exponent  defined by

defined by  corresponding to the mean

corresponding to the mean  over all trajectories (black line) are given in each panel in black. (C) Same as in (B), in cells treated with DNP (n = 38).

over all trajectories (black line) are given in each panel in black. (C) Same as in (B), in cells treated with DNP (n = 38).

We determined the contributions of metabolic activity and thermal fluctuations to the motion of attB (15). We added 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) to cells, which depletes a cell of ATP and GTP and measured movement of the two loci (14). Addition of DNP caused a drastic reduction in the power-law exponents of the mean square displacements of attB in both directions, and a moderate reduction in the effective diffusion coefficients (Figure 5C), indicating that the motion of attB is primarily driven by metabolic activity, and not by thermal fluctuations. This finding is consistent with previous results showing that the thermal contribution to the dynamics of chromosomal loci and plasmids in E. coli and C. crescentus is small (14), and with slower vacuole motion in acanthamoebae as a result of myosin II inhibition (35).

In addition to global metabolic activity, the motion of chromosomal sites is driven on long timescales by genome replication and segregation. To determine the relative contribution of DNA replication and segregation to the subdiffusive behavior of attB, we inhibited DNA replication with 6-(p-hydroxyphenylazo)-uracil (HPUra), a specific inhibitor of DNA polymerase III (36). We show both  and

and  in Supplementary Figure S4A. We found that the values of the power law exponents and effective diffusion constants were comparable to those in untreated cells (Figure 5), indicating that the movements we observed of attB were not related to DNA replication.

in Supplementary Figure S4A. We found that the values of the power law exponents and effective diffusion constants were comparable to those in untreated cells (Figure 5), indicating that the movements we observed of attB were not related to DNA replication.

Three non-exclusive mechanisms are known to give rise to subdiffusive behavior: continuous time random walks (CTRW); obstructed diffusion (OD); and fractional Brownian motion (FLM) (37). In continuous time random walks, motion consists of a sequence of alternating jumping and binding events with a broad distribution of binding times (38–40). Obstructed diffusion reflects motion within a crowded environment such as the cell's interior (41). Fractional Brownian motion reflects a viscoelastic response stemming both from the cytoplasm, and the chromosome itself. As a first step to elucidate which of these mechanism(s) determines attB dynamics, we tested attB trajectories for ergodicity, comparing the time-averaged with the ensemble-averaged

with the ensemble-averaged  (Figure 6A). For an ergodic process, time averages are equivalent to ensemble averages, in particular for the

(Figure 6A). For an ergodic process, time averages are equivalent to ensemble averages, in particular for the  (42). Both calculations yielded the same result within experimental error, supporting the notion that a continuous time random walk mechanism can be ruled out (43,44). Next, to discriminate between the obstructed diffusion and fractional Brownian motion mechanisms, we calculated the velocity auto-correlation function

(42). Both calculations yielded the same result within experimental error, supporting the notion that a continuous time random walk mechanism can be ruled out (43,44). Next, to discriminate between the obstructed diffusion and fractional Brownian motion mechanisms, we calculated the velocity auto-correlation function  (13,42,45):

(13,42,45):

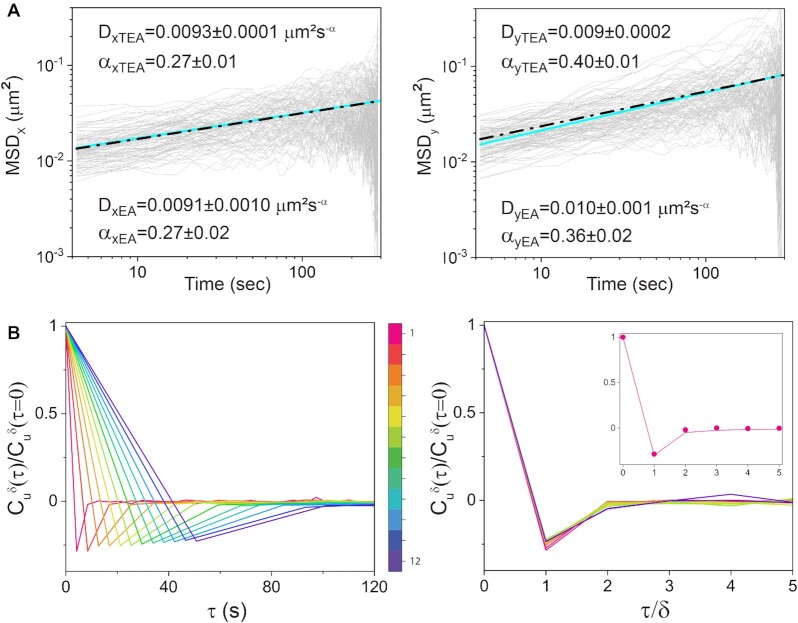

Figure 6.

Dynamics of attB is ergodic. (A) Time-averaged (TEA) mean square displacements of attB (grey) in the longitudinal and transversal directions ( and

and  respectively), plotted as a function of time (n = 50). The straight line (cyan) is a power law fit to the mean

respectively), plotted as a function of time (n = 50). The straight line (cyan) is a power law fit to the mean  of the respective panel. The dot-dashed straight line (black) is a power law fit to the mean of ensemble-averaged

of the respective panel. The dot-dashed straight line (black) is a power law fit to the mean of ensemble-averaged  of attB in the longitudinal and transversal directions (EA). The respective values of the diffusion coefficients and power law exponents are given in each panel for both TAE and AE fits. (B) Left panel: normalized velocity autocorrelation function

of attB in the longitudinal and transversal directions (EA). The respective values of the diffusion coefficients and power law exponents are given in each panel for both TAE and AE fits. (B) Left panel: normalized velocity autocorrelation function  of attB trajectories as a function of time, for different lag times

of attB trajectories as a function of time, for different lag times  , which are multiples of the interval between successive frames (4.23 s). The velocity

, which are multiples of the interval between successive frames (4.23 s). The velocity  between positions separated by intervals

between positions separated by intervals  ranging from 4 to 40 s as indicated by the colour scheme bar. The colour scheme represents the values of

ranging from 4 to 40 s as indicated by the colour scheme bar. The colour scheme represents the values of  from small (red) to large (purple). Right panel: same velocity autocorrelation function as in the corresponding left panel, plotted against rescaled time

from small (red) to large (purple). Right panel: same velocity autocorrelation function as in the corresponding left panel, plotted against rescaled time . Inset: experimentally measured

. Inset: experimentally measured  (circles) and Eq. (2) for

(circles) and Eq. (2) for .

.

|

(1) |

where  , is an velocity and

, is an velocity and  is the time interval over which the velocity is calculated (a multiple of the mean interval between successive frames) and

is the time interval over which the velocity is calculated (a multiple of the mean interval between successive frames) and  is a lag time. We show in Figure 6B the ensemble average of the time-averaged normalized

is a lag time. We show in Figure 6B the ensemble average of the time-averaged normalized  for various values of

for various values of . For all temporal resolutions, the different

. For all temporal resolutions, the different  display a negative peak at

display a negative peak at , indicating that the elastic properties of the intracellular medium induce anti-persistent behavior, a characteristic of a viscoelastic environment. Since obstructed diffusion produces trajectories with uncorrelated steps, and therefore no antipersistent behavior, we conclude that fractional Brownian motion is the model that best describes the dynamical characteristics of attB motion. In fact, fractional Brownian motion describes quantitatively the behavior of the velocity autocorrelation function. Plotting the

, indicating that the elastic properties of the intracellular medium induce anti-persistent behavior, a characteristic of a viscoelastic environment. Since obstructed diffusion produces trajectories with uncorrelated steps, and therefore no antipersistent behavior, we conclude that fractional Brownian motion is the model that best describes the dynamical characteristics of attB motion. In fact, fractional Brownian motion describes quantitatively the behavior of the velocity autocorrelation function. Plotting the  for different

for different  as a function of the rescaled time lag

as a function of the rescaled time lag  results in a collapse of all velocity autocorrelation functions into a universal curve, indicating that the dynamics of the attB locus is self-similar (Figure 6B). This self-similar curve can be well fitted by the predicted

results in a collapse of all velocity autocorrelation functions into a universal curve, indicating that the dynamics of the attB locus is self-similar (Figure 6B). This self-similar curve can be well fitted by the predicted  from fractional Brownian motion (45,46):

from fractional Brownian motion (45,46):

|

(2) |

as shown in Figure 6B (inset). Depletion of ATP and GTP by DNP results in stronger viscoelastic behavior (Supplementary Figure S5A) than in the untreated case (Figure 6B), consistently with the observed lower values of the power law exponents  (Figure 5C).

(Figure 5C).

Tracking the motion of ICEBs1 in transconjugants

We also characterized the movement of ICEBs1 in transconjugants. Figure 3 displays representative ICEBs1 trajectories, color-coded according to time. The mean square displacements in transversal and longitudinal directions  and

and  are shown in Supplementary Figure S6A. The dynamics are subdiffusive and the large asymmetry in the motion in transversal and longitudinal directions is reflected in a ∼4-fold difference in the exponents

are shown in Supplementary Figure S6A. The dynamics are subdiffusive and the large asymmetry in the motion in transversal and longitudinal directions is reflected in a ∼4-fold difference in the exponents  and

and  . Since the dynamical characterization of ICEBs1 was carried out in the same cells as that for attB, we assume their dynamics is also governed by the viscoelastic nature of the cytoplasm. The heterogeneity of ICEBs1 motion (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S2), and in particular the existence of both local and cell-scale explorations, indicates that ICEBs1 dynamics are heavily influenced by the chromosomal structure in the transconjugant.

. Since the dynamical characterization of ICEBs1 was carried out in the same cells as that for attB, we assume their dynamics is also governed by the viscoelastic nature of the cytoplasm. The heterogeneity of ICEBs1 motion (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S2), and in particular the existence of both local and cell-scale explorations, indicates that ICEBs1 dynamics are heavily influenced by the chromosomal structure in the transconjugant.

Effects of perturbing chromosomal structure on ICEBs1 dynamics

Further insights into the role of chromosomal structure can be gleaned by following the behavior of ICEBs1 and attB in cells treated with antibiotics that inhibit either transcription or translation, known to affect chromosomal structure (47–52). Specifically, we used rifampicin, an inhibitor of transcription that is known to induce nucleoid expansion (51,53–56), and chloramphenicol, an inhibitor of translation that is known to cause nucleoid compaction (53,56–58). Note that blocking transcription by treatment with rifampicin essentially also prevents translation after degradation of pre-existing mRNA.

Rifampicin significantly affected ICEBs1 dynamics. We found that in 76 ± 3% (mean ± SE, n = 213) of cells, ICEBs1 displayed highly mobile behavior spanning most of the cell (Supplementary Figure S6B), in contrast to the untreated case (14 ± 2%, n = 868). Similarly to the untreated case, this motion is visibly episodic, with local explorations interrupted by rapid longitudinal motion (Supplementary Figure S6B). This behavior gives rise to a very large asymmetry between the transversal and longitudinal directions. Furthermore, an  analysis shows a ∼2–3-fold increase in the apparent diffusion coefficients in both directions (Supplementary Figure S6B), relative to untreated cells (Supplementary Figure S6A). However, no significant differences were obtained in the values of the power law exponents. Finally, it is worth noting that the larger mobility of ICEBs1 allowed it to carry out an increased exploration of regions where attB loci were more likely to be found (Figure 4B).

analysis shows a ∼2–3-fold increase in the apparent diffusion coefficients in both directions (Supplementary Figure S6B), relative to untreated cells (Supplementary Figure S6A). However, no significant differences were obtained in the values of the power law exponents. Finally, it is worth noting that the larger mobility of ICEBs1 allowed it to carry out an increased exploration of regions where attB loci were more likely to be found (Figure 4B).

In contrast to the effects on ICEBs1, the effects on the dynamics of attB loci are to increase the effective diffusion constants in both longitudinal and transversal directions (Supplementary Figure S4B). An analysis of the dynamics of attB loci using the velocity auto-correlation function  shows that rifampicin treatment preserves the essential features observed in untreated cells (Supplementary Figure S5C).

shows that rifampicin treatment preserves the essential features observed in untreated cells (Supplementary Figure S5C).

In contrast to rifampicin, chloramphenicol induced a marked reduction in the range of motion of ICEBs1 (Supplementary Figure S6C). In fact, the extent of the motion was similar to that of attB. The percentage of cells in which ICEBs1 exhibited motion without being integrated, was 23 ± 1%, about 2-fold less than that in untreated cells (Supplementary Figure S6A). The effects of chloramphenicol on attB were also significant (Supplementary Figure S4C), abolishing the asymmetry in longitudinal and transversal directions observed in the untreated case: a mean square displacement analysis of attB trajectories showed that within experimental error,  and

and  (Supplementary Figure S6C). This result is consistent with the known compaction of the chromosome by chloramphenicol, which was shown previously to stabilize mRNAs and induce accumulation of rRNAs (56). We tested whether chromosome compaction would also enable larger explorations of the cell's interior by ICEBs1. This notion is borne out by the results shown in Figure 4C. Furthermore, the likelihood of finding attB near a cell center was observed to be higher than in the untreated case, in line with the reported compaction of the chromosome (53,56–58). None of the antibiotic treatments nor HPUra, affected the behavior of the velocity auto-correlation functions of attB (Supplementary Figure S5B–D). Based on the different results with rifampicin and chloramphenicol, we conclude that the effects of blocking transcription with rifampicin were not due to the pleiotropic effects of blocking translation. Together, our results indicate that perturbations of chromosome structure and alteration of the crowded nature of the cytoplasm by rifampicin and chloramphenicol affect the dynamics of ICEBs1, as it searches for its integration site.

(Supplementary Figure S6C). This result is consistent with the known compaction of the chromosome by chloramphenicol, which was shown previously to stabilize mRNAs and induce accumulation of rRNAs (56). We tested whether chromosome compaction would also enable larger explorations of the cell's interior by ICEBs1. This notion is borne out by the results shown in Figure 4C. Furthermore, the likelihood of finding attB near a cell center was observed to be higher than in the untreated case, in line with the reported compaction of the chromosome (53,56–58). None of the antibiotic treatments nor HPUra, affected the behavior of the velocity auto-correlation functions of attB (Supplementary Figure S5B–D). Based on the different results with rifampicin and chloramphenicol, we conclude that the effects of blocking transcription with rifampicin were not due to the pleiotropic effects of blocking translation. Together, our results indicate that perturbations of chromosome structure and alteration of the crowded nature of the cytoplasm by rifampicin and chloramphenicol affect the dynamics of ICEBs1, as it searches for its integration site.

DISCUSSION

A striking feature that emerges from the experiments reported in this work is the stark contrast between the large variability of dynamical behaviors that ICEBs1 can display as it searches the B. subtilis chromosome, and the quasi-regular motion of the chromosomal site of integration (attB). As discussed below, we believe that the structure of the bacterial chromosome (59) likely dictates the dynamical characteristics of ICEBs1 movement.

Recent experiments and models of chromosomal configurations and segregation in B. subtilis have revealed that on large scales, the chromosome is arranged longitudinally, with bristle-like plectonemic loops topologically isolated at their base, protruding in the transversal (radial) direction, in a bottle-brush configuration (29,32,47,59–61). The pronounced asymmetry in the  of attB loci we observed, with larger displacements along the longitudinal than in the transversal direction is consistent with this structure: while bristles may easily fluctuate together along the longitudinal direction, displacements in the transversal radial direction are more constrained by the embedding of the attB site within the bottle-brush structure. This asymmetric behavior, observed at subcellular scales, may be more general and contrasts with asymmetric mean square displacements detected at extracellular scales during cellular motion in gradients (62). The mean square displacement power law exponents of attB trajectories are indicative of sub-diffusive behavior, and are consistent with previous observations on the motion of chromosomal loci in other bacteria such as E. coli and C. crescentus (17,63).

of attB loci we observed, with larger displacements along the longitudinal than in the transversal direction is consistent with this structure: while bristles may easily fluctuate together along the longitudinal direction, displacements in the transversal radial direction are more constrained by the embedding of the attB site within the bottle-brush structure. This asymmetric behavior, observed at subcellular scales, may be more general and contrasts with asymmetric mean square displacements detected at extracellular scales during cellular motion in gradients (62). The mean square displacement power law exponents of attB trajectories are indicative of sub-diffusive behavior, and are consistent with previous observations on the motion of chromosomal loci in other bacteria such as E. coli and C. crescentus (17,63).

Furthermore, our analysis indicates that the dynamics of attB are ergodic and that sub-diffusivity is due primarily to the viscoelastic nature of the nucleoid (64). attB constitutes a moving target driven by active processes (29,63,65) and the spatial extent of its motion is limited to well-defined subcellular regions centered around 1/4 and 3/4 of the cell's length. The positional distribution of ICEBs1 that has not yet integrated along the longitudinal coordinate display overlap with attB positions that can allow ICEBs1 to find its target for integration. Simulations have provided evidence that sub-diffusion massively enhances the probability of finding a target despite being slower than normal diffusion, making a search process more reliable (66,67).

In contrast to the relatively regular dynamical behavior of attB, ICEBs1 motion was characterized by significant dynamical heterogeneity, ranging from rapid large-scale motion that spanned a large portion of the cell length, to localized motion, e.g. near cell centers, to quiescent behavior near cell poles. These behaviors are in addition to that of the integrated element, which behaves similarly to attB. The sub-diffusive motion of ICEBs1 is driven primarily by out-of-equilibrium, athermal, metabolic fluctuations of the cytoplasm (14), and by transient integrase-mediated associations between the recipient chromosome and ICEBs1 (68).

It is difficult to reconcile the episodic rapid, large-scale motion of ICEBs1 as it criss-crosses a cell with penetration and reptation through brush bristles. We hypothesize that during such episodes, ICEBs1 localizes primarily to nucleoid fringes where its motion is relatively unhindered. This picture is consistent with entropic eviction of plasmids from the nucleoid, observed in experiments in E. coli and simulations (69). The observed localization and motion of ICEBs1s near cell centers between sister copies of attB indicates that brush density there is reduced, as expected between the two nucleoids of incipient daughter cells, and is indicative of an entropic price for ICEBs1 to penetrate into the respective bottlebrush structures.

The importance of chromosomal structure in determining ICEBs1 dynamics in a transconjugant is further substantiated by the effects of perturbations to chromosomal structure. Inhibition of transcription by rifampicin is known to decompact the chromosome, which has been observed to span all the cytoplasm up to the membrane (51,53). The effects of chromosomal structure decompaction are clearly observed in the dynamical behavior of ICEBs1. Following treatment with rifampicin, the proportion of cells in which ICEBs1 displays fast, free motion is significantly larger than in the untreated case (∼5-fold), as measured by the apparent diffusion coefficient. These features are consistent with ICEBs1 motion within an open, porous chromosomal mesh. The mesh size  of the bacterial nucleoid regarded as a polymer network has been measured recently to be

of the bacterial nucleoid regarded as a polymer network has been measured recently to be  50 nm in the case of E. coli (56). Assuming that the ∼20 kb DNA of ICEBs1 undergoes similar compaction as the bacterial genome, and that

50 nm in the case of E. coli (56). Assuming that the ∼20 kb DNA of ICEBs1 undergoes similar compaction as the bacterial genome, and that  in B. subtilis is similar to that of E. coli, one can estimate the size of ICEBs1 within the cytoplasm. The estimate yields 50–70 nm, a size that is of the same order of magnitude as

in B. subtilis is similar to that of E. coli, one can estimate the size of ICEBs1 within the cytoplasm. The estimate yields 50–70 nm, a size that is of the same order of magnitude as  , enabling the search for attB across the cell. The larger percentage of cells displaying large scale high mobility dynamics of ICEBs1 with rifampicin is in line with these notions. One may speculate that larger ICEs will display a lower efficiency of search and integration than ICEBs1. We also note that in eukaryotic cells, objects whose size is smaller than 50 nm -below the pore size of the cytoplasmic network- behave like Brownian particles diffusing in a medium of low viscosity (70). Effects of rifampicin on the changes in chromosomal structure are also noticeable in the dynamical behavior of attB. The comparable values of

, enabling the search for attB across the cell. The larger percentage of cells displaying large scale high mobility dynamics of ICEBs1 with rifampicin is in line with these notions. One may speculate that larger ICEs will display a lower efficiency of search and integration than ICEBs1. We also note that in eukaryotic cells, objects whose size is smaller than 50 nm -below the pore size of the cytoplasmic network- behave like Brownian particles diffusing in a medium of low viscosity (70). Effects of rifampicin on the changes in chromosomal structure are also noticeable in the dynamical behavior of attB. The comparable values of  and

and  indicate a partial loss of the anisotropy of motion observed in the untreated case. Nonetheless, residual anisotropy still remains in the apparent diffusion coefficients (

indicate a partial loss of the anisotropy of motion observed in the untreated case. Nonetheless, residual anisotropy still remains in the apparent diffusion coefficients ( ). Note that the values of these coefficients are about three-fold larger than in the untreated case, indicating larger local mobility of chromosomal segments. These results are consistent with previous evidence showing that rifampicin effects reduces the static fraction of SMC proteins in B. subtilis and increases its diffusion (71).

). Note that the values of these coefficients are about three-fold larger than in the untreated case, indicating larger local mobility of chromosomal segments. These results are consistent with previous evidence showing that rifampicin effects reduces the static fraction of SMC proteins in B. subtilis and increases its diffusion (71).

Whereas the compaction of the chromosome by inhibition of translation, and the consequent availability of a larger nucleoid-free volume might have led to greater mobility of ICEBs1, the results of our experiments indicate that this is not the case. The drastic reduction in the proportion of highly mobile ICEBs1s observed after addition of chloramphenicol is instead consistent with evidence from a recent study in which it was shown that nucleoid compaction by translation inhibition is caused by an increase in RNA levels(56), since chloramphenicol results in stabilization of mRNAs (72–74), and in higher levels of free rRNAs (75,76). The higher levels of RNA in nucleoid-free regions, crowding the intracellular medium may also hinder significantly ICEBs1s mobility. In addition, a compacted chromosome may also severely reduce accessibility and search for attB due to a decrease in mesh size.

Based on the observed response of ICEBs1 to changes in the compaction state of the bacterial chromosome induced by antibiotics, we anticipate that the dynamics of the search process might also be affected by the size of the ICE itself. ICEBs1 is ∼21 kb, but ICEs range from ∼12 kb to ∼500 kb (77,78). ICEs are increasingly used for genetic engineering and analyses, particularly in undomesticated bacteria (79). Understanding the effects of ICE size on the search process will be important in improving their use and in understanding the physical constraints on target site selection.

The search mechanism used by ICEBs1 differs substantially from that used by lambda phage to find its attachment site during lysogenization (80). In sharp contrast to ICEBs1s, which can span all a recipient's interior until the integration site attB is found, phage DNA remains confined near its point of entry primarily near the poles in an infected cell. There, the integration site approaches it, driven by the replication and segregation of the host genome (80). Thus, borrowing the language of the rendezvous problem of operations research, phage lambda employs a ‘Wait for Mummy’ strategy (WFM) (81), in order to find its integration site. We hypothesize that ICEBs1 motion may be required to enable encounter with its integration site, as ICEBs1 can likely enter a recipient cell at any point along the cell's contour (16), in contrast to lambda DNA that enters preferentially at the cell poles. The WFM strategy is rarely optimal (82), and yet lysogenization of lambda phage can reach a very high efficiency (∼60%).

While the variegated dynamical behavior of ICEBs1 differs considerably from that of lambda phage, our experiments following the search at the single-cell level reveal that the efficiency of target location by ICEBs1 for an integration site is very high. Indeed, the fractal dimension associated with the trajectory of an ICEBs1 prior to integration is  , and since

, and since  values are smaller than 1,

values are smaller than 1,  , i.e. larger than the embedding space. This guarantees that the path explored by the ICEBs1 is space-filling, a crucial feature to ensure a thorough search for the attB target. In the unlikely case in which an integration site is not found, the rapid cell to cell spreading of ICEBs1 along chains, common in microbial communities on surfaces, increases further the efficiency of conjugation, amplifying the number of cells that acquire conjugative mobile genetic elements (16,83,84).

, i.e. larger than the embedding space. This guarantees that the path explored by the ICEBs1 is space-filling, a crucial feature to ensure a thorough search for the attB target. In the unlikely case in which an integration site is not found, the rapid cell to cell spreading of ICEBs1 along chains, common in microbial communities on surfaces, increases further the efficiency of conjugation, amplifying the number of cells that acquire conjugative mobile genetic elements (16,83,84).

The task faced by an ICE as it searches for a unique site of integration along a host chromosome is highly challenging. Bacterial chromosomes are typically millions of base pairs long, and the number of possible addresses is thus very large. Furthermore, the search is compounded by the complex nature of the crowded, viscoelastic bacterial interior and its non-equilibrium, active nature. Compared to transcription factors searching for cognate binding sites, the small number of ICEs in a recipient is small and their size is about an order of magnitude larger. Yet, the search is efficient and target sites are located within physiologically relevant timescales. How is this task accomplished?

Our results provide key insights about the strategy used by integrating conjugating DNA elements in their search. First, far from being a diffusive process, the search is episodic, allowing for compact local explorations interspersed by periods in which ICE motion is fast, crisscrossing the cell within seconds-long intervals. This highly heterogeneous dynamic behavior and the attendant search strategy, is consistent with bacterial chromosome structure, and underscores the fact that heterogeneity is essential in bacterial subcellular organization, despite the fact that a bacterium consists of only one compartment. Second, the motion of both the integration site and ICE is subdiffusive and remarkably, highly anisotropic. Our observations indicate that the anisotropy reflects bacterial chromosome structure and not simply the stadium-like, elongated shape of a cell and its boundaries. From a theoretical perspective, our work stimulates the quest for an anomalous diffusion model that can characterize the anisotropy in the diffusion exponents. The interest extends beyond the specific context of ICEs and attBs motion, to active systems in which the anisotropy might prove crucial for uncovering details that are lost in the steady-state (85,86).

Our results raise many fundamental evolutionary questions. For example, has the size of ICEBs1, or other long DNA molecules imported into a cell during horizontal gene transfer processes been tuned by evolutionary pressures? Answering this question is critical to optimize the use of ICEs for the genetic modification of undomesticated bacteria (79). Has the site of integration along the chromosome been optimized? In this context it is important to stress that the degree of compaction varies locally along chromosomal coordinates, affecting the size mesh, the search by ICEBs1 and its access to the integration locus. To what extent is anisotropic dynamical behavior advantageous to search process? Future studies could address these questions and the extent to which other aspects of the search were honed by evolution.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The software for segmentation is available at https://github.com/ferinat/Bacillus-Analysis-Public.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank R. Voituriez, Y. Kafri, O. Raz and O. Dudko for useful conversations; Miguel Camarena Sainz, Kfir Eisner, Itan Brill, Noa Rosenthal, Anna Joukov and Yam Tawachi for assistance in data processing and Laurel Wright for some of the initial genetic design. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Rinat Arbel-Goren, Department of Physics of Complex Systems, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Saria A McKeithen-Mead, Department of Biology Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Dominik Voglmaier, Department of Physics of Complex Systems, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Idana Afremov, Department of Physics of Complex Systems, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Gianluca Teza, Department of Physics of Complex Systems, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

Alan D Grossman, Department of Biology Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Joel Stavans, Department of Physics of Complex Systems, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

MathWorks Science Fellowship (to SAMM, in part); NIGMS predoctoral training grant [T32 GM007287]; National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health ]R01 GM050895 and R35 GM122538 to A.D.G.]; G.T. was supported by the Center for Statistical Mechanics at the Weizmann Institute of Science [662962] of the Simons Foundation; HALT and Hydrotronics of the EU Horizon 2020 program; NSF-BSF [2020765]. Funding for open access charge: Internal Weizmann fund.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wiedenbeck J., Cohan F.M.. Origins of bacterial diversity through horizontal genetic transfer and adaptation to new ecological niches. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011; 35:957–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guglielmini J., Quintais L., Garcillán-Barcia M.P., de la Cruz F., Rocha E.P.C.. The repertoire of ICE in prokaryotes underscores the unity, diversity, and ubiquity of conjugation. PLoS Genet. 2011; 7:e1002222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Touchon M., Rocha E.P.C.. Coevolution of the organization and structure of prokaryotic genomes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016; 8:a018168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carraro N., Burrus V.. Biology of three ICE families: SXT/R391, ICEBs1, and ICESt1/ICESt3. In Mobile DNA III. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2014; 2:289–309. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Auchtung J.M., Aleksanyan N., Bulku A., Berkmen M.B.. Biology of ICEBs1, an integrative and conjugative element in Bacillus subtilis. Plasmid. 2016; 86:14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Menard K.L., Grossman A.D.. Selective pressures to maintain attachment site specificity of integrative and conjugative elements. PLoS Genet. 2013; 9:e1003623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Halford S.E., Marko J.F.. How do site-specific DNA-binding proteins find their targets?. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32:3040–3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dey P., Bhattacherjee A.. Role of macromolecular crowding on the intracellular diffusion of DNA binding proteins. Sci Rep. 2017; 8:844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barzel A., Kupiec M.. Finding a match: how do homologous sequences get together for recombination?. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008; 9:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tal A., Arbel-Goren R., Costantino N., Court D.L., Stavans J.. Location of the unique integration site on an Escherichia coli chromosome by bacteriophage lambda DNA in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014; 111:7308–7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones D.L., Leroy P., Unoson C., Fange D., Ćurić V., Lawson M.J., Elf J.. Kinetics of dCas9 target search in Escherichia coli. Science. 2017; 357:1420–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vink J., Martens K., Vlot M., McKenzie R., Almendros C., Bonilla B., Brocken D., Hohlbein J., Brouns S.. Direct visualization of native CRISPR target search in live bacteria reveals Cascade DNA surveillance mechanism. Mol. Cell. 2020; 77:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. S Mogre S., Brown A.I., Koslover E.F.. Getting around the cell: physical transport in the intracellular world. Phys. Biol. 2020; 17:061003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parry B.R., Surovtsev I.V., Cabeen M.T., O’Hern C.S., Dufresne E.R., Jacobs-Wagner C.. The bacterial cytoplasm has glass-like properties and is fluidized by metabolic activity. Cell. 2014; 156:183–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weber S.C., Spakowitz A.J., Theriot J.A.. Nonthermal ATP-dependent fluctuations contribute to the in vivo motion of chromosomal loci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012; 109:7338–7343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Babic A., Berkmen M.B., Lee C.A., Grossman A.D.. Efficient gene transfer in bacterial cell chains. MBio. 2011; 2:e00027-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weber S.C., Spakowitz A.J., Theriot J.A.. Bacterial chromosomal loci move subdiffusively through a viscoelastic cytoplasm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010; 104:238102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Espeli O., Mercier R., Boccard F.. DNA dynamics vary according to macrodomain topography in the E. coli chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 2008; 68:1418–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fiebig A., Keren K., Theriot J.A.. Fine-scale time-lapse analysis of the biphasic, dynamic behaviour of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 2006; 60:1164–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perego M., Spiegelman G.B., Hoch J.A.. Structure of the gene for the transition state regulator, abrB: regulator synthesis is controlled by the spo0A sporulation gene in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 1988; 2:689–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith J.L., Goldberg J.M., Grossman A.D.. Complete genome sequences of Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis laboratory strains JH642 (AG174) and AG1839. Genome Announc. 2014; 2:663–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Auchtung J.M., Lee C.A., Monson R.E., Lehman A.P., Grossman A.D.. Regulation of a Bacillus subtilis mobile genetic element by intercellular signaling and the global DNA damage response. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005; 102:12554–12559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee P.S., Grossman A.D.. The chromosome partitioning proteins Soj (ParA) and Spo0J (ParB) contribute to accurate chromosome partitioning, separation of replicated sister origins, and regulation of replication initiation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2006; 60:853–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shaner N., Lin M., McKeown M., Steinbach P., Hazelwood K., Davidson M., Tsien R.. Improving the photostability of bright monomeric orange and red fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods. 2008; 5:545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lau I.F., Filipe S.R., Søballe B., Økstad O.A., Barre F.X., Sherratt D.J.. Spatial and temporal organization of replicating Escherichia coli chromosomes. Mol. Microbiol. 2003; 49:731–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harwood C., Cutting S.. Molecular Biological Methods for Bacillus. Wiley. 1990; NY: Chichester. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gibson D.G., Young L., Chuang R.-Y., Craig Venter J., Hutchison C.A. III, Smith H.O. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods. 2009; 6:343–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Golding I., Cox E.C.. Physical nature of bacterial cytoplasm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006; 96:098102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang X., Llopis P.M., Rudner D.Z.. Bacillus subtilis chromosome organization oscillates between two distinct patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014; 111:12877–12882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kuhlman T.E., Cox E.C.. Gene location and DNA density determine transcription factor distributions in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012; 8:610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Javer A., Long Z., Nugent E., Grisi M., Siriwatwetchakul K., Dorfman K.D., Cicuta P., Lagomarsino M.C.. Short-time movement of E. coli chromosomal loci depends on coordinate and subcellular localization. Nat. Commun. 2013; 4:3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marbouty M., Le Gall A., Cattoni D.I., Cournac A., Koh A., Fiche J.-B., Mozziconacci J., Murray H., Koszul R., Nollmann M.. Condensin-and replication-mediated bacterial chromosome folding and origin condensation revealed by Hi-C and super-resolution imaging. Mol. Cell. 2015; 59:588–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang X., Le T.B.K., Lajoie B.R., Dekker J., Laub M.T., Rudner D.Z.. Condensin promotes the juxtaposition of DNA flanking its loading site in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 2015; 29:1661–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burov S., Metzler R., Barkai E.. Aging and nonergodicity beyond the Khinchin theorem. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010; 107:13228–13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reverey J.F., Jeon J.H., Bao H., Leippe M., Metzler R., Selhuber-Unkel C.. Superdiffusion dominates intracellular particle motion in the supercrowded cytoplasm of pathogenic Acanthamoeba castellanii. Sci. Rep. 2015; 51:11690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brown N. 6-(p-Hydroxyphenylazo)-uracil: a selective inhibitor of host DNA replication in phage-infected Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1970; 67:1454–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lutz E. Fractional Langevin equation. Fractional Dynamics: Recent Advances. 2011; World Scientific Publishing Co; 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Montroll E., Weiss G.. Random walks on lattices. II. J. Math. Phys. 1965; 6:167–181. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saxton M.J. Anomalous diffusion due to binding: a Monte Carlo study. Biophys. J. 1996; 70:1250–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scher H., Montroll E.W.. Anomalous transit-time dispersion in amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. B. 1975; 12:2455–2477. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saxton M.J. Anomalous diffusion due to obstacles: a Monte Carlo study. Biophys. J. 1994; 66:394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang Y., Dudko O.K.. First-passage processes in the genome. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2016; 45:117–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. He Y., Burov S., Metzler R., Barkai E.. Random time-scale invariant diffusion and transport coefficients. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008; 101:058101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Deng W., Barkai E.. Ergodic properties of fractional Brownian-Langevin motion. Phys. Rev. E - Stat. Nonlinear, Soft Matter Phys. 2009; 79:011112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Burov S., Jeon J.-H., Metzler R., Barkai E.. Single particle tracking in systems showing anomalous diffusion: the role of weak ergodicity breaking. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011; 13:1800–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Backlund M., Joyner R., Moerner W.. Chromosomal locus tracking with proper accounting of static and dynamic errors. Phys. Rev. E. 2015; 91:062716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang X., Brandão H.B., Le T.B.K., Laub M.T., Rudner D.Z.. Bacillus subtilis SMC complexes juxtapose chromosome arms as they travel from origin to terminus. Science. 2017; 355:524–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stracy M., Lesterlin C., De Leon F., Uphoff S., Zawadzki P., Kapanidis A.. Live-cell superresolution microscopy reveals the organization of RNA polymerase in the bacterial nucleoid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:E4390–E4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wlodarski M., Mancini L., Raciti B., Sclavi B., Lagomarsino M.C., Cicuta P.. Cytosolic crowding drives the dynamics of both genome and cytosol in Escherichia coli challenged with sub-lethal antibiotic treatments. Iscience. 2020; 23:101560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wlodarski M., Raciti B., Kotar J., Cosentino Lagomarsino M., Fraser G.M., Cicuta P.. Both genome and cytosol dynamics change in E. coli challenged with sublethal rifampicin. Phys. Biol. 2017; 14:015005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cabrera J.E., Jin D.J.. The distribution of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli is dynamic and sensitive to environmental cues. Mol. Microbiol. 2003; 50:1493–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bylund J.E., Haines M.A., Piggot P.J., Higgins M.L.. Axial filament formation in Bacillus subtilis: induction of nucleoids of increasing length after addition of chloramphenicol to exponential-phase cultures approaching stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 1993; 175:1886–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bakshi S., Siryaporn A., Goulian M., Weisshaar J.C.. Superresolution imaging of ribosomes and RNA polymerase in live Escherichia coli cells. Mol. Microbiol. 2012; 85:21–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yang D., Männik J., Retterer S.T., Männik J.. The effects of polydisperse crowders on the compaction of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. Mol. Microbiol. 2020; 113:1022–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sun Q., Margolin W.. Effects of perturbing nucleoid structure on nucleoid occlusion-mediated toporegulation of FtsZ ring assembly. J. Bacteriol. 2004; 186:3951–3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xiang Y., Surovtsev I., Chang Y., Govers S., Parry R., Liu J., Jacobs-Wagner C.. Interconnecting solvent quality, transcription, and chromosome folding in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2021; 184:3626–3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cabrera J.E., Cagliero C., Quan S., Squires C.L., Jin D.J.. Active transcription of rRNA operons condenses the nucleoid in Escherichia coli: examining the effect of transcription on nucleoid structure in the absence of transertion. J. Bacteriol. 2009; 191:4180–4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zimmerman S.B. Toroidal nucleoids in Escherichia coli exposed to chloramphenicol. J. Struct. Biol. 2002; 138:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Badrinarayanan A., Le T.B.K., Laub M.T.. Bacterial chromosome organization and segregation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015; 31:171–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zraly C.B., Dingwall A.K.. The chromatin remodeling and mRNA splicing functions of the Brahma (SWI/SNF) complex are mediated by the SNR1/SNF5 regulatory subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:5975–5987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Banigan E.J., Mirny L.A.. Loop extrusion: theory meets single-molecule experiments. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020; 64:124–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dieterich P., Lindemann O., Moskopp M.L., Tauzin S., Huttenlocher A., Klages R., Chechkin A., Schwab A.. Anomalous diffusion and asymmetric tempering memory in neutrophil chemotaxis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022; 18:e1010089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Campos M., Jacobs-Wagner C.. Cellular organization of the transfer of genetic information. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013; 16:171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kleckner N., Fisher J.K., Stouf M., White M.A., Bates D., Witz G.. The bacterial nucleoid: nature, dynamics and sister segregation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014; 22:127–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. El Najjar N., Geisel D., Schmidt F., Dersch S., Mayer B., Hartmann R., Eckhardt B., Lenz P., Graumann P.L.. Chromosome segregation in Bacillus subtilis follows an overall pattern of linear movement and is highly robust against cell cycle perturbations. Msphere. 2020; 5:e00255-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Guigas G., Weiss M.. Sampling the cell with anomalous diffusion—the discovery of slowness. Biophys. J. 2008; 94:90–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Weiss M. Crowding, diffusion, and biochemical reactions. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014; 307:383–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Johnson C.M., Grossman A.D.. Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs): what they do and how they work. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2015; 49:577–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Planchenault C., Pons M.C., Schiavon C., Siguier P., Rech J., Guynet C., Dauverd-Girault J., Cury J., Rocha E.P.C., Junier I.et al.. Intracellular positioning systems limit the entropic eviction of secondary replicons toward the nucleoid edges in bacterial cells. J. Mol. Biol. 2020; 432:745–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Etoc F., Balloul E., Vicario C., Normanno D., Liße D., Sittner A., Piehler J., Dahan M., Coppey M.. Non-specific interactions govern cytosolic diffusion of nanosized objects in mammalian cells. Nat. Mater. 2018; 17:740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schibany S., Hinrichs R., Hernández-Tamayo R., Graumann P.L.. The major chromosome condensation factors Smc, HBsu, and Gyrase in Bacillus subtilis operate via strikingly different patterns of motion. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2020; 5:e00817-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lopez P., Marchand I., Yarchuk O., Dreyfus M.. Translation inhibitors stabilize Escherichia coli mRNAs independently of ribosome protection. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998; 95:6067–6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pato M.L., Bennett P.M., Von Meyenburg K.. Messenger ribonucleic acid synthesis and degradation in Escherichia coli during inhibition of translation. J. Bacteriol. 1973; 116:710–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Schneider E., Blundell M., Kennell D.. Translation and mRNA decay. MGG Mol. Gen. Genet. 1978; 160:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cole J.R., Olsson C.L., Hershey J.W.B., Grunberg-Manago M., Nomura M.. Feedback regulation of rRNA synthesis in Escherichia coli: requirement for initiation factor IF2. J. Mol. Biol. 1987; 198:383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kurland C.G., Maaløe O.. Regulation of ribosomal and transfer RNA synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 1962; 4:193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cury J., Touchon M., Rocha E.P.C.. Integrative and conjugative elements and their hosts: composition, distribution and organization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:8943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wozniak R., Waldor M.. Integrative and conjugative elements: mosaic mobile genetic elements enabling dynamic lateral gene flow. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010; 8:552–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Brophy J., Triassi A., Adams B., Renberg R., Stratis-Cullum D., Grossman A., Voigt C.. Engineered integrative and conjugative elements for efficient and inducible DNA transfer to undomesticated bacteria. Nat. Microbiol. 2018; 3:1043–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tal A., Arbel-Goren R., Costantino N., Court D.L., Stavans J.. Location of the unique integration site on an Escherichia coli chromosome by bacteriophage lambda DNA in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014; 111:7308–7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Alpern S. Rendezvous search: a personal perspective. Oper. Res. 2002; 50:772–795. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Alpern S., Gal S.. Introduction to rendezvous search. The Theory of Search Games and Rendezvous. 2003; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lécuyer F., Bourassa J.-S., Gélinas M., Charron-Lamoureux V., Burrus V., Beauregard P.B.. Biofilm formation drives transfer of the conjugative element ICEBs1 in Bacillus subtilis. Msphere. 2018; 3:e00473-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jones J.M., Grinberg I., Eldar A., Grossman A.D.. A mobile genetic element increases bacterial host fitness by manipulating development. Elife. 2021; 10:e65924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Teza G., Stella A.. Exact coarse graining preserves entropy production out of equilibrium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020; 125:110601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Teza G. Out of Equilibrium Dynamics: From an Entropy of the Growth to the Growth of Entropy Production. 2020; University of Padova; PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The software for segmentation is available at https://github.com/ferinat/Bacillus-Analysis-Public.