Abstract

Background

The immune system is affected by the circadian rhythm. The objective of this study was to clarify whether time-of-day patterns (early or late in the daytime) of the infusion of nivolumab and whether its duration affect treatment efficacy in metastatic or recurrent esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (R/M-ESCC).

Methods

The data of 62 consecutive patients with R/M-ESCC treated with nivolumab between February 2017 and May 2022 were retrospectively reviewed. The infusion of nivolumab before 13:00 was set as ‘early in the day’, and that after 13:00 was set as ‘late in the day’. The treatment efficacy was compared between early and late groups by 3 criteria (first infusion, during the first 3 months, and all treatment courses).

Results

The overall survival, progression-free survival, and response rate of patients received the first dose in the early group were significantly superior to those of patients in the late group. The progression-free survival and response rate of patients who received the majority of nivolumab infusions before 13:00 during the first 3 months were significantly superior to those who received it after 13:00, with the exception of overall survival. There were no significant differences in the overall survival, progression-free survival, and response rate between patients who received the majority of nivolumab infusions before 13:00 of all treatment courses and those who received it after 13:00.

Conclusion

The timing of the infusion of nivolumab may affect treatment efficacy in R/M-ESCC.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer, Metastasis, Chemotherapy, Immunotherapy, Circadian rhythm

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the seventh most common cancer worldwide [1]. The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has increased dramatically in developed countries in recent decades. However, most esophageal cancers diagnosed in Japan are squamous cell carcinomas, with adenocarcinomas accounting for only 2.7% of all esophageal cancers [2].

In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have innovated the treatment of advanced solid cancers, including esophageal cancer. Inhibitors of programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) in combination with inhibitors of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) or chemotherapy have become the standard regimen for recurrent or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (R/M-ESCC) [3, 4]. Based on the results of the ATTRACTION-3 trial and the KEYNOTE-181 trial, the standard second-line treatment for patients with R/M-ESCC who previously received fluorouracil and platinum-based chemotherapy is PD-1 inhibitors [5, 6].

The blockade of PD-1 and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) interactions promotes T-cell-mediated anti-tumor effects. PD-L1 expression is a widely used biomarker to predict the response to PD-1 inhibitors. However, dynamic alterations in PD-L1 expression are a major challenge in determining the actual status of PD-L1. Optimal biomarkers to predict the response to PD-1 inhibitors, including nivolumab, have not yet been identified.

Chronotherapy, in which the timing of therapy administration is optimized, has been used for cytotoxic anti-cancer agents [7, 8]. However, only two retrospective reports have been published about the timing of ICI infusion of all courses [9, 10], and no information about the initial and the first three months timing of nivolumab infusion as a predictive marker for response to ICI therapy in R/M-ESCC patients has been reported.

The objective of this study was to clarify whether time-of-day patterns (early or late in the daytime) of the infusion of nivolumab and whether its duration affect treatment efficacy in patients with R/M-ESCC.

Patients and methods

Patient population

A retrospective review of 62 consecutive patients with R/M-ESCC treated with nivolumab at Kyoto University Hospital between February 2017 and May 2022 was performed. Patient selection criteria were as follows: (1) histologically confirmed R/M-ESCC, (2) intolerant or refractory to prior fluorouracil and platinum-containing chemotherapy treatment, (3) age ≥ 20 years, (4) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) 0–2, and (5) adequate bone marrow, hepatic, and renal function (neutrophils ≥ 1500/mm3, hemoglobin ≥ 8.0 g/dL, platelet count ≥ 10 × 104/mm3, total bilirubin ≤ 1.5 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase ≤ 100 IU/L, alanine transaminase ≤ 100 IU/L, and creatinine clearance ≥ 50 mL/min). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee and the Institutional Review Board of Kyoto University Hospital (R3238). Patients received a 3 mg/kg or 240 mg nivolumab intravenous infusion every 2 weeks, a 2 mg/kg nivolumab every 3 weeks, or 480 mg nivolumab every 4 weeks.

Data collection

The following information was abstracted from electric medical records and radiological images: treatment initiation date, age, gender, ECOG PS, recurrent disease, number of metastatic sites, nivolumab infusion timing of all courses, the season in which the first dose was given, laboratory test results at the start of nivolumab treatment, previous treatments, prior chemotherapy regimen before nivolumab, response to nivolumab, the toxicity of nivolumab, and final date of survival assessment.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval between the date of initiation of nivolumab treatment and the date of death due to any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the interval between the date of initiation of nivolumab treatment and the date of disease progression or death due to any cause. Patients not experiencing disease progression or death were censored at the last follow-up visit. The objective response rate was assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1 criteria. All patient characteristics were classified as categorical variables.

Because outpatient infusion of chemotherapy at our hospital starts between 10:00 and 16:00, the cut-off was set at the midpoint at 13:00. The infusion of nivolumab between 10:00 and 12:59 was set as ‘early in the day’, and that between 13:00 and 16:00 was set as ‘late in the day’. In analyses, patients were classified into two groups by three criteria, respectively: early-first group received their first infusion before 13:00, late-first group received their first infusion after 13:00, early-3 M group received at least 50% of their infusions before 13:00 during the first 3 months, late-3 M group received fewer than 50% of their infusions before 13:00 during the first 3 months, early-all group received at least 50% of their infusions before 13:00 of all treatment courses, and late-all group received fewer than 50% of their infusions before 13:00 of all treatment courses. OS, PFS, response rates, and disease control rates according to RECIST v1.1 criteria were compared between two groups (early-first group vs. late-first group, early-3 M group vs. late-3 M group, and early-all group vs. late-all group), respectively.

Multivariate analysis models were used to examine the effect of independent variables on survival. The selection of variables in model 1 was based on the previous trial and included age, ECOG PS, and recurrent disease [5], and those in model 2 were all assessments with a p value < 0.10 in univariate analyses. The duration group with the lowest hazard ratios (HR) in the early versus late comparison were included as covariable in the multivariate analysis. OS and PFS curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. HR and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using Cox regression models. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA, version 17 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 62 consecutive patients with R/M-ESCC treated with nivolumab, 27 were in the early-first group, and 35 were in the late-first group. Of all patients, 15 patients had received more than once after 13:00 in the early-first group, and 13 patients had received more than once before 13:00 in the late-first group. There were no significant differences between the patient characteristics in the early- and late-first groups, except for bone metastasis in 3 M groups. The median follow-up period among survivors after administration of nivolumab was 13.8 months (range, 2.5–60.2 months).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Early-first group | Late-first group | P | Early-3 M group | Late-3 M group | P | Early-all group | Late-all group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | (n = 27) | (n = 35) | (n = 30) | (n = 32) | (n = 26) | (n = 36) | |||

| < 65 | 9 | 15 | 0.170 | 11 | 13 | 0.749 | 10 | 14 | 0.973 |

| ≥ 65 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 16 | 22 | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 20 | 30 | 0.250 | 24 | 26 | 0.901 | 20 | 30 | 0.528 |

| Female | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||

| ECOG PS | |||||||||

| 0 | 16 | 14 | 0.322 | 16 | 14 | 0.700 | 15 | 15 | 0.460 |

| 1 | 10 | 19 | 13 | 16 | 10 | 19 | |||

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Recurrent | |||||||||

| No | 6 | 7 | 0.831 | 7 | 6 | 0.658 | 5 | 8 | 0.775 |

| Yes | 21 | 28 | 23 | 26 | 21 | 28 | |||

| Number of metastatic organ sites | |||||||||

| 0–1 | 15 | 24 | 0.293 | 18 | 21 | 0.647 | 17 | 22 | 0.731 |

| 2–6 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 14 | |||

| Lung metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 17 | 26 | 0.338 | 20 | 23 | 0.657 | 18 | 25 | 0.986 |

| Yes | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 11 | |||

| Liver metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 23 | 29 | 0.805 | 26 | 26 | 0.562 | 23 | 29 | 0.404 |

| Yes | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 7 | |||

| Bone metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 27 | 31 | 0.069 | 30 | 28 | 0.045 | 26 | 32 | 0.079 |

| Yes | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | |||

| Distant lymph-node metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 17 | 28 | 0.136 | 20 | 25 | 0.312 | 17 | 28 | 0.280 |

| Yes | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 8 | |||

| Uncommon organ metastasis | |||||||||

| No | 23 | 30 | 0.953 | 25 | 28 | 0.642 | 24 | 29 | 0.195 |

| Yes | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 7 | |||

| Alb (g/dL) | |||||||||

| < 3.8 | 15 | 18 | 0.747 | 19 | 14 | 0.122 | 16 | 17 | 0.265 |

| ≥ 3.8 | 12 | 17 | 11 | 18 | 10 | 19 | |||

| CRP (mg/dL) | |||||||||

| < 1.0 | 18 | 20 | 0.445 | 19 | 19 | 0.749 | 17 | 21 | 0.574 |

| ≥ 1.0 | 9 | 15 | 11 | 13 | 9 | 15 | |||

| Previous surgery | |||||||||

| No | 21 | 28 | 0.831 | 25 | 24 | 0.421 | 21 | 28 | 0.775 |

| Yes | 6 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | |||

| Previous radiotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 10 | 7 | 0.136 | 10 | 7 | 0.312 | 8 | 9 | 0.615 |

| Yes | 17 | 28 | 20 | 25 | 18 | 27 | |||

| Previous taxane chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 8 | 7 | 0.380 | 9 | 6 | 0.301 | 9 | 6 | 0.103 |

| Yes | 19 | 28 | 21 | 26 | 17 | 30 | |||

| Season in which first dose was given | |||||||||

| Winter | 5 | 7 | 0.165 | 6 | 6 | 0.513 | 4 | 8 | 0.233 |

| Spring | 12 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 16 | |||

| Summer | 3 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | |||

| Fall | 7 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 3 | |||

| First dosage | |||||||||

| 2 mg/kg | 1 | 2 | 0.543 | 1 | 2 | 0.215 | 2 | 1 | 0.179 |

| 3 mg/kg | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| 240 mg | 13 | 18 | 13 | 18 | 10 | 21 | |||

| 480 mg | 13 | 13 | 16 | 10 | 14 | 12 | |||

ECOG PS Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status, Alb albumin, CRP C-reactive protein

Response and survival

The overall response rates were 44.4% in the early-first group and 20.0% in the late-first group (p = 0.038), 46.7% in the early-3 M group and 15.6% in the late-3 M group (p = 0.008), and 38.5% in the early-all group and 25.0% in the late-all group (p = 0.257), respectively (Table 2). The disease control rates were 51.9% in the early-first group and 34.3% in the late-first group (p = 0.165), 53.3% in the early-3 M group and 31.3% in the late-3 M group (p = 0.078), and 46.2% in the early-all group and 38.9% in the late-all group (p = 0.567).

Table 2.

Overall response

| Early-first group | Late-first group | Early-3 M group | Late-3 M group | Early-all group | Late-all group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 27) | (n = 35) | (n = 30) | (n = 32) | (n = 26) | (n = 36) | |

| Complete response (n) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Partial response (n) | 10 | 7 | 13 | 4 | 9 | 8 |

| Stable disease (n) | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Progressive disease (n) | 13 | 23 | 14 | 22 | 14 | 22 |

| Response rate (%) | 44.4 | 20.0 | 46.7 | 15.6 | 38.5 | 25.0 |

| Disease control rate (%) | 51.9 | 34.3 | 53.3 | 31.3 | 46.2 | 38.9 |

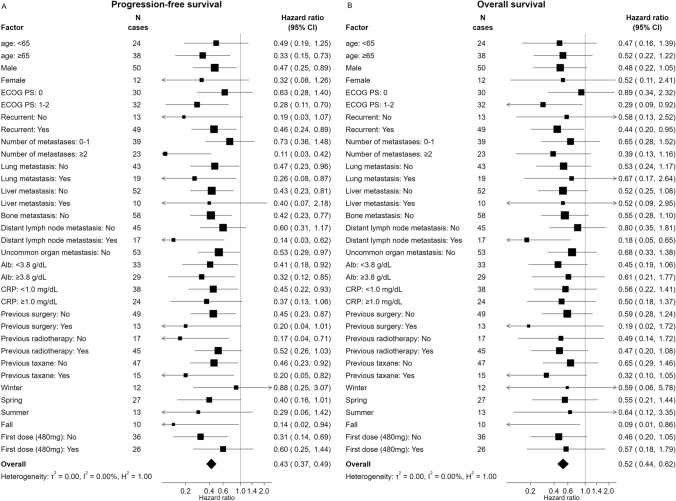

At the time of data cut-off, progressive disease was observed in 57 of 62 patients (91.9%). Patients in the early-first group experienced significantly longer PFS than patients in the late-first group (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.22–0.71, p = 0.002). The 1-year PFS rates were 33.3% in the early-first group and 2.8% in the late-first group (Fig. 1A). Patients in the early-3 M group experienced significantly longer PFS than patients in the late-3 M group (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26–0.79, p = 0.005). The 1-year PFS rates were 30.0% in the early-3 M group and 3.1% in the late-3 M group (Fig. 1B). Patients in the early-all group tend to have longer PFS than patients in the late-all group (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.44–1.28, p = 0.303). The 1-year PFS rates were 23.0% in the early-all group and 11.1% in the late-all group (Fig. 1C). In univariate analyses, the early-first group, female gender, no bone metastasis, and C-reactive protein (CRP) < 1.0 mg/dL were associated with longer PFS (Table 3). In both models of multivariate analysis, it revealed that the early-first group was independently and significantly associated with longer PFS (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with recurrent or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab infusion before 13:00 (early-first group) and after 13:00 (late-first group) at the first dose (A), treated with the majority of nivolumab infusions occurred before 13:00 (early-3 M group) or after 13:00 (late-3 M group) during the first 3 months (B), and treated with the majority of nivolumab infusions occurred before 13:00 (early-all group) or after 13:00 (late-all group) of all treatment courses (C)

Table 3.

Factors associated with PFS and OS in univariate analyses

| reference | PFS | OS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |||

| Initial timing of nivolumab | Late-first | Early-first | 0.40 | 0.22–0.71 | 0.002 | 0.51 | 0.26–0.99 | 0.049 |

| Age (y) | < 65 | ≥ 65 | 0.99 | 0.58–1.70 | 0.995 | 1.19 | 0.62–2.26 | 0.585 |

| Gender | Male | Female | 0.54 | 0.26–1.11 | 0.097 | 0.52 | 0.22–1.21 | 0.134 |

| ECOG PS | 0 | 1–2 | 1.37 | 0.81–2.33 | 0.235 | 2.41 | 1.23–4.70 | 0.010 |

| Recurrent | No | Yes | 1.14 | 0.58–2.21 | 0.691 | 1.01 | 0.45–2.19 | 0.976 |

| Number of metastatic organ sites | 0–1 | 2–6 | 0.76 | 0.44–1.33 | 0.352 | 0.85 | 0.45–1.60 | 0.622 |

| Lung metastasis | No | Yes | 0.93 | 0.53–1.65 | 0.827 | 0.57 | 0.28–1.16 | 0.124 |

| Liver metastasis | No | Yes | 1.22 | 0.57–2.59 | 0.603 | 1.5 | 0.65–3.44 | 0.332 |

| Bone metastasis | No | Yes | 2.93 | 1.04–8.27 | 0.042 | 3.66 | 1.06–12.55 | 0.039 |

| Distant lymph-node metastasis | No | Yes | 0.62 | 0.33–1.15 | 0.132 | 0.83 | 0.42–1.65 | 0.606 |

| Uncommon organ metastasis | No | Yes | 0.65 | 0.29–1.46 | 0.303 | 0.84 | 0.32–2.16 | 0.721 |

| Alb (g/dL) | < 3.8 | ≥ 3.8 | 0.79 | 0.46–1.34 | 0.390 | 0.45 | 0.24–0.87 | 0.018 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | < 1.0 | ≥ 1.0 | 1.75 | 1.02–3.01 | 0.041 | 2.85 | 1.52–5.34 | 0.001 |

| Previous surgery | No | Yes | 0.94 | 0.48–1.83 | 0.872 | 0.94 | 0.43–2.05 | 0.880 |

| Previous radiotherapy | No | Yes | 1.44 | 0.77–2.70 | 0.245 | 1.04 | 0.50–2.14 | 0.910 |

| Previous taxane chemotherapy | No | Yes | 0.71 | 0.38–1.31 | 0.277 | 1.02 | 0.52–2.02 | 0.935 |

| Season in which first dose was given | Winter | Spring | 0.76 | 0.37–1.57 | 0.470 | 1.26 | 0.46–3.40 | 0.649 |

| Summer | 0.71 | 0.31–1.63 | 0.432 | 1.2 | 0.40–3.62 | 0.734 | ||

| Fall | 0.58 | 0.23–1.47 | 0.260 | 1.33 | 0.41–4.30 | 0.632 | ||

| First dosage (480 mg) | No | Yes | 1.10 | 0.63–1.89 | 0.730 | 1.2 | 0.58–2.46 | 0.618 |

PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, ECOG PS Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status, Alb albumin, CRP C-reactive protein

Table 4.

Factors associated with PFS and OS in multivariate analyses

| reference | PFS | OS | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |||

| Initial timing of nivolumab | Late-first | Early-first | 0.39 | 0.21–0.71 | 0.002 | 0.41 | 0.22–0.76 | 0.005 | 0.50 | 0.26–0.98 | 0.044 | 0.47 | 0.23–0.96 | 0.040 |

| Age (y) | < 65 | ≥ 65 | 1.00 | 0.56–1.80 | 0.982 | 1.11 | 0.55–2.23 | 0.757 | ||||||

| Gender | Male | Female | 0.84 | 0.38–1.84 | 0.667 | |||||||||

| ECOG PS | 0 | 1–2 | 1.34 | 0.77–2.35 | 0.295 | 2.36 | 1.19–4.70 | 0.014 | 2.21 | 1.09–4.49 | 0.028 | |||

| Recurrent | No | Yes | 1.03 | 0.51–2.08 | 0.931 | 1.16 | 0.49–2.73 | 0.722 | ||||||

| Bone metastasis | No | Yes | 2.04 | 0.70–5.93 | 0.186 | 1.42 | 0.38–5.24 | 0.593 | ||||||

| Alb (g/dL) | < 3.8 | ≥ 3.8 | 0.66 | 0.31–1.43 | 0.299 | |||||||||

| CRP (mg/dL) | < 1.0 | ≥ 1.0 | 1.77 | 0.98–3.18 | 0.055 | 2.21 | 1.03–4.69 | 0.039 | ||||||

PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, ECOG PS Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status, Alb albumin, CRP C-reactive protein

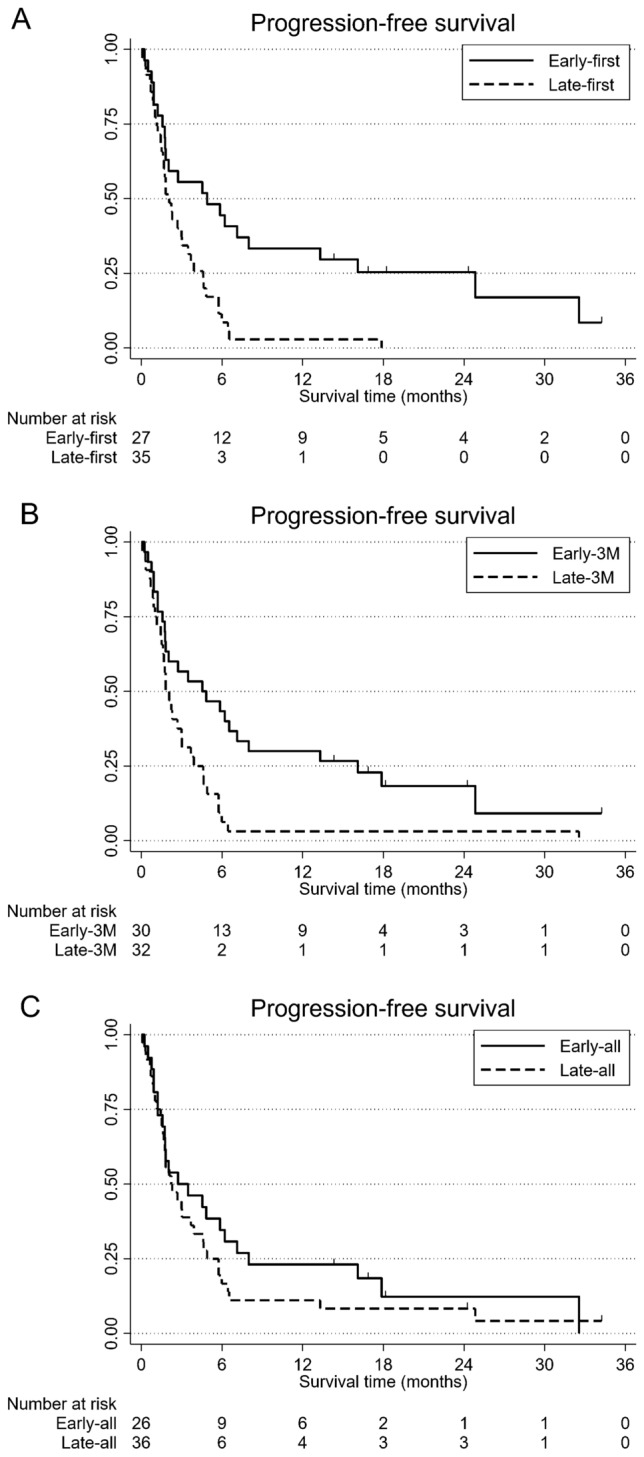

At the time of data cut-off, 41 of 62 patients (66.1%) were deceased. Patients in the early-first group experienced significantly longer OS than patients in the late-first group (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.26–0.95, p = 0.036). The 1 year OS rate was 69.1% in the early-first group and 48.5% in the late-first group (Fig. 2A). Patients in the early-3 M group tend to longer OS than patients in the late-3 M group (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.37–1.26, p = 0.224). The 1-year OS rates were 65.6% in the early-3 M group and 51.0% in the late-3 M group (Fig. 2B). Patients in the early-all group have slightly longer OS than patients in the late-all group (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.50–1.72, p = 0.821). The 1 year OS rates were 60.0% in the early-all group and 56.8% in the late-all group (Fig. 2C). In univariate analyses, the early-first group, PS 0, no bone metastasis, albumin (Alb) ≥ 3.8 g/dL, and CRP < 1.0 mg/dL were associated with longer OS (Table 3). Multivariate analysis revealed early-first group, PS 0, and CRP < 1.0 mg/dL were independently and significantly associated with longer OS (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival (OS) of patients with recurrent or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab infusion before 13:00 (early-first group) and after 13:00 (late-first group) at the fist dose (A), treated with the majority of nivolumab infusions occurred before 13:00 (early-3 M group) or after 13:00 (late-3 M group) during the first 3 months (B), and treated with the majority of nivolumab infusions occurred before 13:00 (early-all group) or after 13:00 (late-all group) of all treatment courses (C)

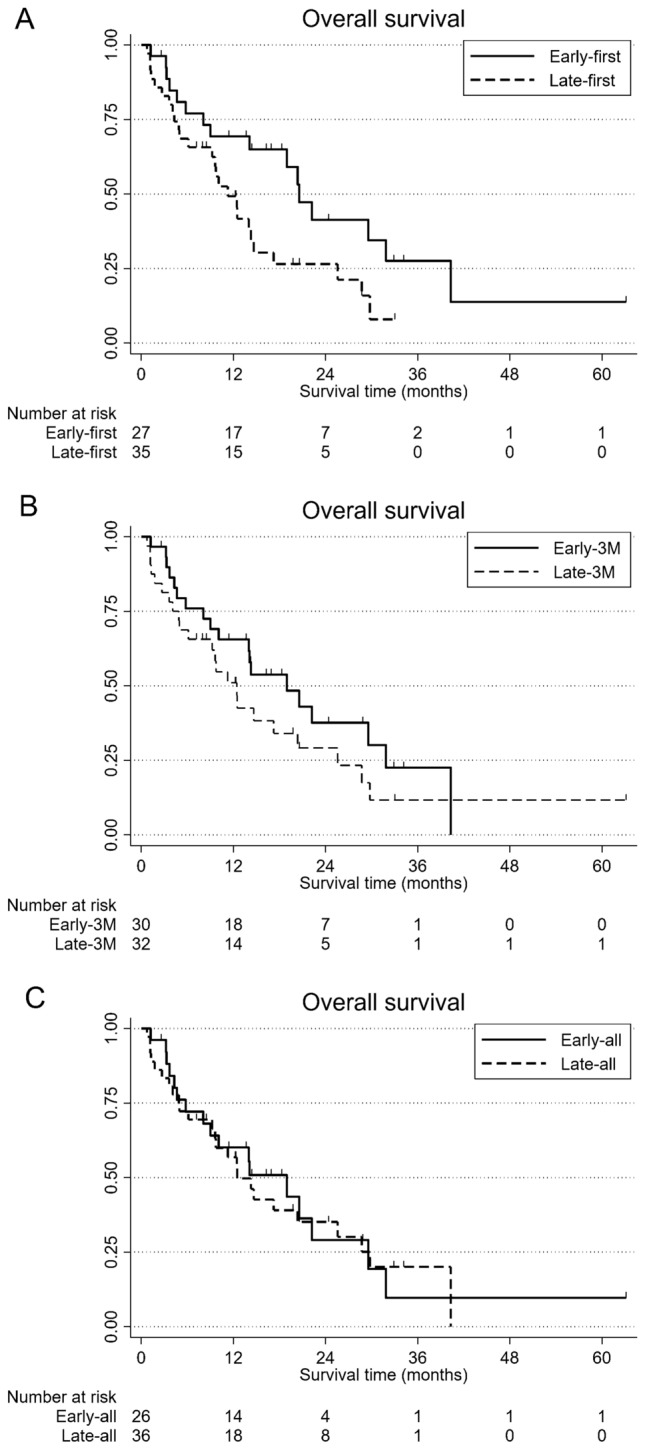

Both assessed survival outcomes were superior in the early-first group compared to the late-first group. Subgroup analyses using the Cox proportional hazard model demonstrated that all subgroups (age, gender, PS, number of metastases, lung metastasis, liver metastasis, bone metastasis, distant lymph-node metastasis, uncommon organ metastasis, Alb, CRP, previous surgery, previous radiotherapy, season, and first dose) in the early-first group had longer PFS and OS compared with those in the late-first group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analyses of PFS (A) and OS (B) in early-first versus late-first groups. Patients with bone metastasis or uncommon organ metastasis were not evaluable in subgroup analyses due to the small numbers. PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, ECOG PS Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status, Alb albumin, CRP C-reactive protein, NE not evaluable

Safety

The incidences of toxicities according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5.0 are shown in Table 5. The most common adverse events were pruritus and hypothyroidism. No grade 4 or 5 adverse events were observed.

Table 5.

Toxicity

| Early-first group | Late-first group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 27) | (n = 35) | |||||

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |

| Proteinuria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mucositis oral | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colitis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Hypopituitarism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Rush maculopapular | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bullous dermatitis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Infusion-related reactions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

This is the first report in which patients with R/M-ESCC were stratified by infusion timing of nivolumab. The present study indicated that response rate, PFS, and OS were significantly superior in patients who received their initial nivolumab infusion early in the day (initial timing of nivolumab infusion between 10:00 and 12:59) compared with patients who received it late in the day (initial timing of nivolumab infusion between 13:00 and 16:00) in overall and all subgroup analyses, and that response rate and PFS were significantly superior in patients who received with the majority of nivolumab infusions occurred before 13:00 compared with patients who received it after 13:00. Additionally, by multivariate analysis, the initial timing of nivolumab infusion was confirmed as an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS.

Our results are in agreement with those recently reported in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer [9, 10]. In the melanoma study (MEMOIR study), evening infusion time (after dusk) was hypothesized to correlate with clinical outcomes in metastatic malignant melanoma treated with ICI, including ipilimumab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab, or a combination of these [9]. The cut-off in that study was set at 16:30. The MEMOIR study showed that the administration of 20% or more of ICI infusions after 16:30 was associated with shorter overall survival than when at least 20% of ICI infusions took place after 16:30. The non-small-cell lung cancer study revealed that PFS and OS were superior in patients who received the majority of nivolumab administrations between 9:27 and 12:54, than in patients who received the infusions between 12:55 and 17:14 [10]. Both study results indicate that patients receiving most of their ICI infusions in the evening have shorter survival than those with fewer evening infusions. These and our results suggest that the circadian rhythm plays a pivotal role in the functioning of the immune system, including anti-cancer immunity.

Randomized or prospective vaccination trials with inactivated influenza, hepatitis A, BCG, and SARS-CoV-2 virus have shown that morning vaccination induced more enhanced immune responses than afternoon or evening vaccination [11–14]. One of the mechanisms behind this effect is considered to be lymphocyte circadian oscillations. Lymphocyte and dendritic cell homing to lymph nodes occurs in a circadian manner that peaks at the active phase, with cells leaving the tissue during the rest phase [15–17]. Tumor tissue consists not only of cancer cells, but also numerous non-cancer cells, such as fibroblasts, epithelial cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. The tumor microenvironment is also associated with the extracellular matrix, growth factors, and cytokines, and supports tumor growth and resistance to chemotherapy. PD-L1 binds to the PD-1 receptor expressed on T cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), preventing their anti-tumor activities through the induction of exhaustion and apoptosis. It has been reported that the circadian expression of the PD-1 receptor is observed in TAMs, and the anti-tumor efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors is enhanced by administering the drug at the time of day (active phase) when PD-1 expression is increased on TAMs [18]. The serum half-time of nivolumab was 12–20 days, with a reported sustained mean plateau occupancy of 72% of PD-1 molecules on circulating T cells for 2 months or more after one infusion [19]. The efficacy or toxicity of nivolumab has been reported not to be associated with pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [20], whereas nivolumab pharmacodynamics in tumors, the tumor microenvironment, and tumor-draining lymph nodes might critically impact efficacy [21, 22]. The above reports indicate that the active phase could be the time to most effectively trigger the nivolumab-induced priming of the immune system. However, the time to the nivolumab-induced priming of the immune system is unclear. Steady-state concentrations of nivolumab were reached by 12 weeks [23]. Our results comparing the majority of the nivolumab infusions before 13:00 with after 13:00 at the first dose, during the first 3 months, and all courses showed that the timing of nivolumab infusions at the first dose and during the first 3 months affected the response rate and progression-free survival. This suggests that early in the daytime infusion of nivolumab at the first dose and during the first 3 months may be important. The length of this important period needs to be clarified in the future.

Limitations of the present study include the small sample size and the retrospective study design. The patients in the present study had R/M-ESCC, for which it remains unknown what the role is of circadian rhythms in CD8+ T cells or how circadian rhythm affects other immune functions. In the present study, only the results of nivolumab alone are available. We do not have any data using pembrolizumab alone for esophageal cancer, although a similar trend is possible with pembrolizumab alone. Furthermore, circadian biomarkers, such as rest or activity, temperature, and cortisol rhythms, are not defined in this pathology. In addition, we could not evaluate other biomarkers, such as PD-L1.

In conclusion, although prospective studies on the timing of nivolumab and assessment of biomarkers are required to validate the present findings, the infusion timing of nivolumab might affect the efficacy of treatment in patients with R/M-ESCC. Chronotherapy with nivolumab has the potential to change clinical practice, while it comes at no additional costs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Juko Shimizu for reviewing the medical records in the present study.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions on the inclusion of information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Declarations

Ethical Statement

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions.

Informed consent

Informed consent or a substitute for it was obtained from all patients before inclusion in the study.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and do not have financial or funding support to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe M, Tachimori Y, Oyama T, et al. Comprehensive registry of esophageal cancer in Japan, 2013. Esophagus. 2021;18:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10388-020-00785-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun JM, Shen L, Shah MA, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2021;398:759–771. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doki Y, Ajani JA, Kato K, et al. Nivolumab combination therapy in advanced esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:449–462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2111380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato K, Cho BC, Takahashi M, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to previous chemotherapy (ATTRACTION-3): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1506–1517. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30626-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kojima T, Shah MA, Muro K, et al. Randomized phase III KEYNOTE-181 study of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:4138–4148. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hrushesky WJ. Circadian timing of cancer chemotherapy. Science. 1985;228:73–75. doi: 10.1126/science.3883493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lévi F, Zidani R, Misset JL. Randomised multicentre trial of chronotherapy with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and folinic acid in metastatic colorectal cancer. Int Organ Cancer Chronother Lancet. 1997;350:681–686. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)03358-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qian DC, Kleber T, Brammer B, et al. Effect of immunotherapy time-of-day infusion on overall survival among patients with advanced melanoma in the USA (MEMOIR): a propensity score-matched analysis of a single-centre, longitudinal study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1777–1786. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karaboué A, Collon T, Pavese I, et al. Time-dependent efficacy of checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab: results from a pilot study in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:896. doi: 10.3390/cancers14040896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips AC, Gallagher S, Carroll D, et al. Preliminary evidence that morning vaccination is associated with an enhanced antibody response in men. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:663–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long JE, Drayson MT, Taylor AE, et al. Morning vaccination enhances antibody response over afternoon vaccination: a cluster-randomised trial. Vaccine. 2016;34:2679–2685. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Bree LCJ, Mourits VP, Koeken VA, et al. Circadian rhythm influences induction of trained immunity by BCG vaccination. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:5603–5617. doi: 10.1172/JCI133934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Liu Y, Liu D, et al. Time of day influences immune response to an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res. 2021;31:1215–1217. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00541-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki K, Hayano Y, Nakai A, et al. Adrenergic control of the adaptive immune response by diurnal lymphocyte recirculation through lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2016;213:2567–2574. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Druzd D, Matveeva O, Ince L, et al. Lymphocyte circadian clocks control lymph node trafficking and adaptive immune responses. Immunity. 2017;46:120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C, Barnoud C, Cenerenti M, et al. Dendritic cells direct circadian anti-tumor immune responses. Nature. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05605-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuruta A, Shiiba Y, Matsunaga N, et al. Diurnal expression of PD-1 on tumor-associated macrophages underlies the dosing time-dependent antitumor effects of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor BMS-1 in B16/BL6 melanoma-bearing mice. Mol Cancer Res. 2022;20:972–982. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-21-0786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellesoeur A, Ollier E, Allard M, et al. Is there an exposure-response relationship for nivolumab in real-world NSCLC patients? Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1784. doi: 10.3390/cancers11111784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fransen MF, van Hall T, Ossendorp F. Immune checkpoint therapy: Tumor draining lymph nodes in the spotlights. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9401. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francis DM, Manspeaker MP, Schudel A, et al. Blockade of immune checkpoints in lymph nodes through locoregional delivery augments cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaay3575. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. OPDIVO (NIVOLUMAB). Approved Drug Label. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/125554s119lbl.pdf. Accessed 12 Mar 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions on the inclusion of information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.