Abstract

Background:

Recent studies reported abnormal alpha-synuclein deposition in biopsyaccessible sites of the peripheral nervous system in Parkinson’s disease (PD). This has considerable implications for clinical diagnosis. Moreover, if deposition occurs early, it may enable tissue diagnosis of prodromal PD.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to develop and test an automated bright-field immunohistochemical assay of cutaneous pathological alpha-synuclein deposition in patients with idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, PD, and atypical parkinsonism and in control subjects.

Methods:

For assay development, postmortem skin biopsies were taken from 28 patients with autopsy-confirmed Lewy body disease and 23 control subjects. Biopsies were stained for pathological alpha-synuclein in automated stainers using a novel dual-immunohistochemical assay for serine 129-phosphorylated alpha-synuclein and panneuronal marker protein gene product 9.5. After validation, single 3-mm punch skin biopsies were taken from the cervical 8 paravertebral area from 79 subjects (28 idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, 20 PD, 10 atypical parkinsonism, and 21 control subjects). Raters blinded to clinical diagnosis assessed the biopsies.

Results:

The immunohistochemistry assay differentiated alpha-synuclein pathology from nonpathologicalappearing alpha-synuclein using combined phosphatase and protease treatments. Among autopsy samples, 26 of 28 Lewy body samples and none of the 23 controls were positive. Among living subjects, punch biopsies were positive in 23 (82%) subjects with idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, 14 (70%) subjects with PD, 2 (20%) subjects with atypical parkinsonism, and none (0%) of the control subjects. After a 3-year follow-up, eight idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder subjects phenoconverted to defined neurodegenerative syndromes, in accordance with baseline biopsy results.

Conclusion:

Even with a single 3-mm punch biopsy, there is considerable promise for using pathological alpha-synuclein deposition in skin to diagnose both clinical and prodromal PD. © 2020 International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society

Keywords: alpha-synuclein, PGP9.5, UCHL1, RBD, Parkinson’s disease, skin biopsy

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is defined by the deposition of aggregated alpha-synuclein (aSyn) in the central nervous system.1,2 Definitive diagnosis can be made only at autopsy. However, synuclein deposition has also been found in peripheral nerves of patients with PD from a variety of tissue sites, including skin.3–9 Skin biopsy is a particularly attractive biomarker because of the ease at which tissue can be obtained. An assay for aSyn pathology in skin that can be made broadly accessible could become a critical diagnostic tool for accurate diagnosis of neurodegenerative synucleinopathies.

PD may start with a prodromal stage wherein nonmotor manifestations predominate.10–12 One of the strongest clinical markers of synucleinopathy is idiopathic/isolated rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (iRBD). More than 80% of patients with iRBD will experience development of PD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), or multiple system atrophy (MSA).13,14 Recently, pathological aSyn was also reported in skin of individuals with iRBD,15,16 suggesting that tissue diagnosis of synucleinopathy even in its prodromal stages is possible.

In this study, we evaluated deposition of pathological aSyn in skin biopsies first from an autopsy-confirmed PD cohort and then in living cohorts of patients with clinical PD, atypical parkinsonism, and iRBD and control subjects using a novel bright-field immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay deployed on automated staining platforms.

Subjects and Methods

Autopsy Subjects

Synuclein staining patterns were first assessed in autopsied patients and later confirmed in living subjects. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue was obtained from Roche Tissue Diagnostics (Tucson, AZ, USA) internal tissue bank, Discovery Life Sciences (Los Osos, CA, USA), and the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program (Sun City, AZ, USA).17 In addition to standardized clinical assessments, diagnosis of PD was confirmed in the donors by the presence of substantia nigra Lewy bodies.17

Living Subjects

Seventy-nine subjects (28 iRBD, 20 PD, 10 atypical parkinsonism, and 21 control subjects) were recruited from June 2016 until June 2018 at McGill University Movement Disorder Clinic and the Center for Advanced Research in Sleep Medicine, Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur de Montréal. Subjects with iRBD were polysomnography confirmed and were free of parkinsonism and dementia based on expert evaluation (R.B.P. and A.-A.-Q.) at the time of skin biopsy. Subject with PD met criteria for probable PD according to the Movement Disorder Society clinical diagnostic criteria.18 Atypical parkinsonism cases were diagnosed clinically and included progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) (n = 4), vascular parkinsonism (n = 2), MSA (n = 1), corticobasal syndrome (n = 2), and drug-induced parkinsonism (n = 1). Exclusion criteria were age <40 years and dementia of severity sufficient to preclude informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics board of McGill University Health Centre and of Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur, and all subjects gave written informed consent to participate.

All subjects were assessed with a comprehensive neurological examination, as described in the Supporting Information Methods. A single punch skin biopsy 3 mm in diameter was obtained under local anesthesia from the left C8 paravertebral area of each subject, with no stitching required. Other than mild transitory local soreness, no serious or persistent complications of the procedure were reported by any patient. Biopsies were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin.

Staining Procedure

Details of immunohistochemical assay for pathological aSyn are described in the Supporting Information Methods. In brief, FFPE biopsies were sectioned at 4-μm thickness, deparaffinized, and sequentially stained for aSyn phosphorylated at serine 129 (pS129-aSyn) as a surrogate marker for pathological aSyn and for the panneuronal marker protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5) to identify nerve fibers in skin. The rabbit monoclonal antibodies against pS129-aSyn (clone 7E2; Roche) and PGP9.5 (clone EPR4118; Abcam) were detected using, respectively, black silver and yellow dabcyl chromogens. Nonpathological pS129-aSyn was removed by protease and alkaline phosphatase before staining. A schematic depicting the pS129-aSyn and PGP9.5 silver/yellow dual-IHC assay configuration is shown in Supporting Information Figure S1A. Images of skin tissue stained with the assay are shown in Supporting Information Figure S1B.

Evaluation of in vivo Skin Biopsy Slides

Raters evaluated slides while fully blinded to diagnosis. Every biopsy sample was subdivided into two blocks before paraffin embedding, and from each block four nonadjacent slides (typically 16–20 μm apart) were stained and analyzed. A positively stained neuronal feature was reported as the occurrence of black dots or short jagged lines with discrete morphology and smooth contours visible at 20× objective magnification, in close proximity with PGP9.5-stained neuronal features. The numbers of PGP9.5-positive neuronal and pathological aSyn-positive features were reported for every slide. A slide was considered positive if any of the PGP9.5 features on that slide had positive pathological aSyn staining.

Diagnostic Algorithm

We used the complete dataset (eight slides per patient) to explore sources of variability and to derive a practical systematic scoring algorithm for future use. The statistical properties of the proposed diagnostic procedure were studied in sensitivity and power analyses (see Supporting Information for more details). Generation of the decision algorithm itself was conducted post hoc (unblinded to overall staining results), although blinded to whether the algorithm would call a specific patient positive or negative. The algorithm analysis found that to prevent false negatives as a result of undersampling, at least 10 PGP9.5-positive neuronal features needed to be visualized. Based on the number of PGP9.5 features per slide, staining four slides would visualize ≥10 PGP9.5 features in 95% of cases (ie, requiring restaining in ≤5% of negative biopsies). Therefore, the primary diagnostic algorithm was determined as follows:

Initially stain and examine four slides (two slides per block bisected from a single biopsy).

If any feature is positive, the biopsy is considered positive.

If negative, and at least 10 PGP9.5 features are seen, the biopsy is considered negative.

If negative, but less than 10 PGP9.5 features are seen, the remainder of the sample is resectioned/restained ensuring that ≥10 PGP9.5 features have been examined.

We also explored alternate diagnostic algorithms aimed to optimize sensitivity (any synuclein staining in any of the eight slides = positive biopsy) and specificity (at least two positive PGP9.5 features required for positive biopsy, in the first four slides), both of which had no requirement for the minimum number of nerve features. We also performed exploratory analyses aimed at understanding the potential association of staining properties with baseline clinical descriptors. Details of statistical analysis are provided in the Supporting Information Methods.

Results

Patterns of pS129-aSyn Staining in Tissue From Subjects With and Without PD

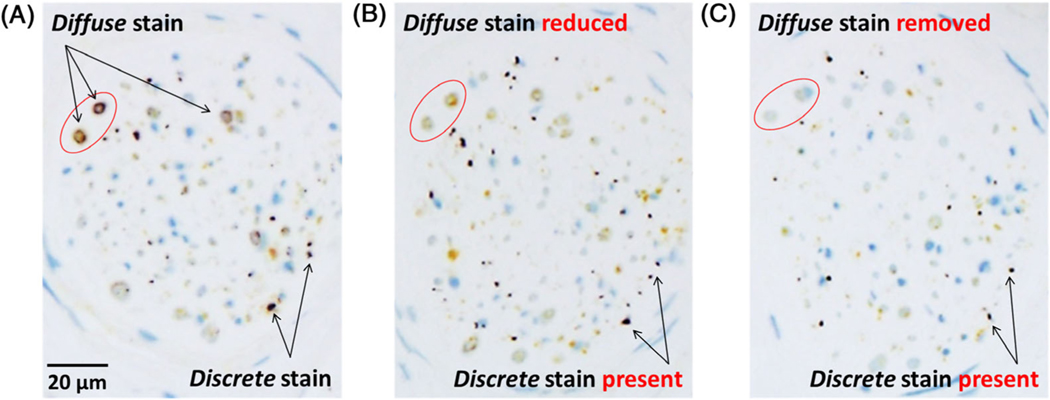

Results documenting specificity of the 7E2 antibody are provided in the Supporting Information Results. This was assessed first on autopsy samples and confirmed in living subjects. Staining of skin sections with 7E2 antibody showed two distinct pS129-aSyn patterns in cutaneous nerve fibers: diffuse/granular and discrete. The diffuse/granular type of pS129-aSyn was consistently observed in nerve bundles (Fig. 1A) in patients and control subjects. It often had a circumferential (Fig. 1A) or a pipelike (Fig. 2) appearance characteristic of myelin sheath. Pathological aSyn has been reported to be resistant to protease and phosphatase.19,20 Consequently, we treated skin tissue sections with protease or alkaline phosphatase before antibody incubation to assess whether this diffuse/granular staining exhibited properties associated with pathological aSyn. As shown in Fig. 1B, the intensity of diffuse/granular staining decreased after protease (Fig. 1B) or phosphatase (Fig. 1C) treatment, suggesting it was likely caused by nonpathological aSyn known to be present in nervous tissue.

FIG. 1.

Skin formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections from patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) stained with pS129-alpha-synuclein (aSyn) and protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5) silver/yellow dual-immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay showing (A) two distinct types of silver pS129-aSyn stain and their differential sensitivities to (B) protease and (C) phosphatase. The pS129-aSyn stain with diffuse and granular morphology was observed mostly in the larger nerve bundles as a circumferential ring around a nerve fiber. This type of pS129-aSyn stain was either reduced or apparently removed (reduced below detectable levels) after pretreatment at 37°C with, respectively, protease 3 for 4 minutes or recombinant bovine alkaline phosphatase for 8 minutes. In contrast, the discrete type of pS129-aSyn stain with smooth contours was resistant to either protease or phosphatase pretreatment. Nerve fibers innervating skin structures were detected using a rabbit monoclonal antibody against PGP9.5 and alkaline phosphatase-activated QM-Dabcyl yellow chromogen as described in Subjects and Methods.

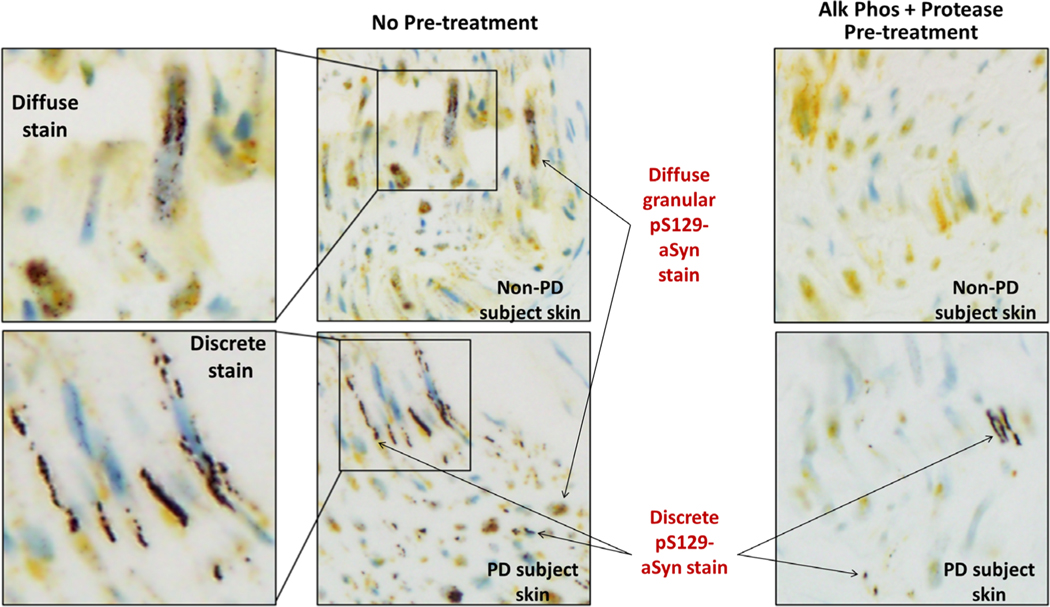

FIG. 2.

Morphologies of pS129-alpha-synuclein (aSyn) stain produced by pS129-aSyn and protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5) silver/yellow dual-immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay in scalp sections from autopsied non-PD and PD subjects with and without combined protease and phosphatase pretreatments. In non-PD subject skin, only diffuse and granular pS129-aSyn stain was observed. The diffuse pS129-aSyn stain exhibited pipelike appearance sheathing nerve fibers sectioned horizontally along the length of the fibers. Discrete pS129 stain was not observed in skin sections of subjects without PD. Both diffuse and discrete stains were seen in skin of subjects with PD. Discrete pS129-aSyn stain appeared as tracks running along the length of nerve fibers. In both non-PD and PD subjects, diffuse and granular pS129-aSyn stain was removed on sequential pretreatments at 37°C with recombinant bovine alkaline phosphatase (Alk Phos) and protease 3 for, respectively, 8 and 4 minutes.

In addition to diffuse/granular staining, a second type of pS129-aSyn stain with a discrete morphology was observed in skin sections exclusively from patients with PD (Figs. 1 and 2). In transverse nerve sections, the discrete pS129-aSyn stain had a dotlike appearance with varying sizes and clearly defined borders (Fig. 1). In sagittal/oblique nerve sections, the discrete pS129-aSyn stain appeared as a solid serpentine line or dots along a track (Fig. 2). The discrete pS129-aSyn stain differed from the diffuse/granular stain in the following ways: (1) its resistance to alkaline phosphatase and/or protease (Fig. 1); and (2) its exclusive presence in skin obtained at autopsy from patients with PD, but not control subjects (Fig. 2).

After protease and phosphatase pretreatment, 7E2 antibody produced discrete silver-stained structures characteristic of nerve fibers in nerve bundles and in association with smooth muscle, glandular structures, and vessels in FFPE skin sections (scalp) from patients with PD (Supporting Information Figs. S2 and S3). Granular/diffuse pS129-aSyn staining was observed in large nerve bundles but rarely in other innervated structures (Supporting Information Fig. S2). In addition to skin, 7E2 antibody produced discrete aSyn signals in both submandibular gland and colon sections from patients with PD (Supporting Information Fig. S4).

Skin Biopsy Diagnosis in Autopsy Samples

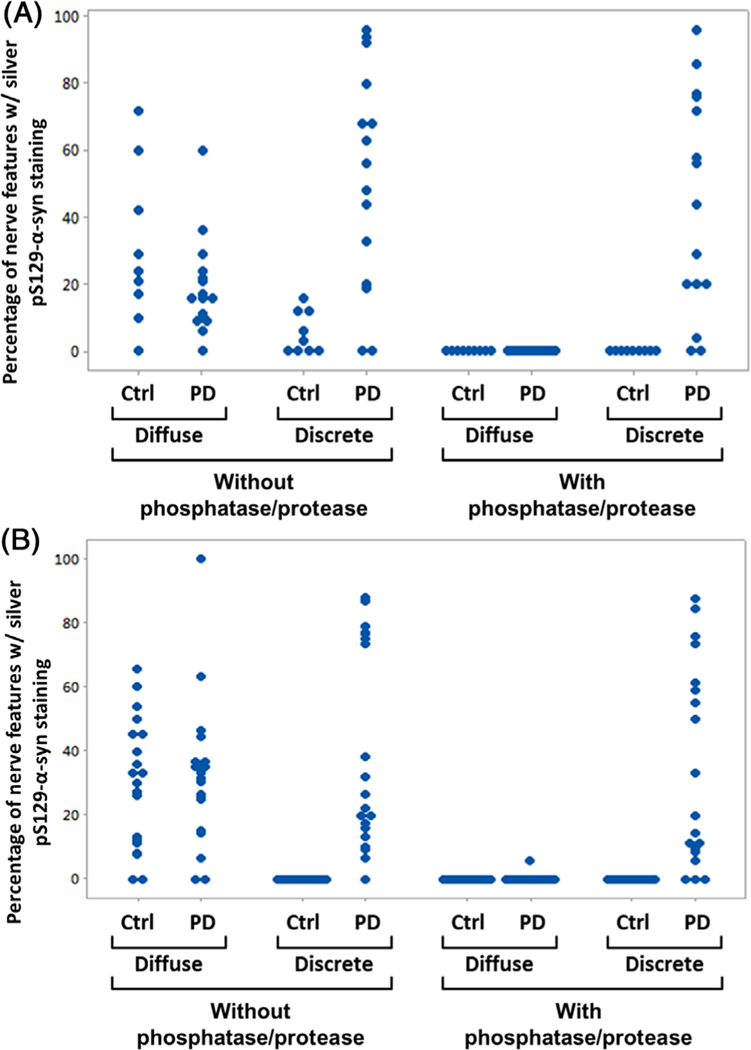

Assay sensitivity and specificity were first assessed in scalp FFPE sections from 15 subjects with autopsy-confirmed PD and 9 non-PD subjects. Demographic information and postmortem Lewy body assessment results are shown in Supporting Information Table S1. Slides were evaluated for numbers of innervated tissue structures that expressed PGP9.5, and percentages of such yellow-stained features that also exhibited pS129-aSyn were recorded. As shown in Fig. 3A, 13 of 15 samples (87%) from subjects with PD exhibited pS129-aSyn of the discrete type after staining with or without phosphatase and protease pretreatment. After phosphatase/protease pretreatment, none of the nine non-PD scalp samples exhibited pS129-aSyn staining (Fig. 3A), suggesting the pretreatment procedure was important for removing nonpathological pS129-aSyn. The diffuse/granular type of pS129-aSyn staining was observed only in the absence of phosphatase/protease pretreatment (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

(A) Individual value plot showing percentages of nerve features containing either diffuse or discrete pS129-alpha-synuclein (aSyn) stain in 4-μm sections of postmortem scalp skin biopsies from 15 subjects with PD and 9 control (Ctrl) subjects without PD. All formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) skin sections were stained with pS129-aSyn and protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5) silver/yellow dual-immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay without and with phosphatase/protease pretreatment as described in Subjects and Methods. (B) Individual value plot showing percentages of nerve features containing either diffuse or discrete pS129-aSyn stain in 4-μm sections of postmortem abdomen skin biopsies from 20 subjects with PD and 20 Ctrl subjects without PD. All FFPE skin sections were stained with pS129-aSyn and PGP9.5 silver/yellow dual-IHC assay without and with phosphatase/protease pretreatment as described in Subjects and Methods. Nerve features are defined as innervated skin structures with yellow chromogens staining neuronal marker PGP9.5. Examples of these are shown in Supporting Information Figures S5 and S6.

Assay sensitivity and specificity were further assessed in abdomen skin from 20 autopsy-confirmed PD and 20 non-PD control subjects (see Supporting Information Table S2 for demographic information and autopsy results). Of the 20 PD samples stained with and without phosphatase/protease pretreatment, discrete pS129-aSyn stain was observed in, respectively, 17 and 19 samples (Fig. 3B). In contrast, none of the 20 non-PD abdomen skin samples exhibited any discrete pS129-aSyn signal (Fig. 3B) (P < 0.001 for both protocols). Diffuse granular pS129-aSyn staining was present in most of the PD and non-PD abdomen skin samples stained without phosphatase and protease pretreatment (Fig. 3B).

Skin from seven patients with PD and six control subjects was sampled in both scalp and abdomen sites. A subject is considered positive if either site presents with pathological aSyn and the assay has an overall 93% sensitivity (26 of 28 patients with PD) and 100% specificity (none of the 23 control subjects).

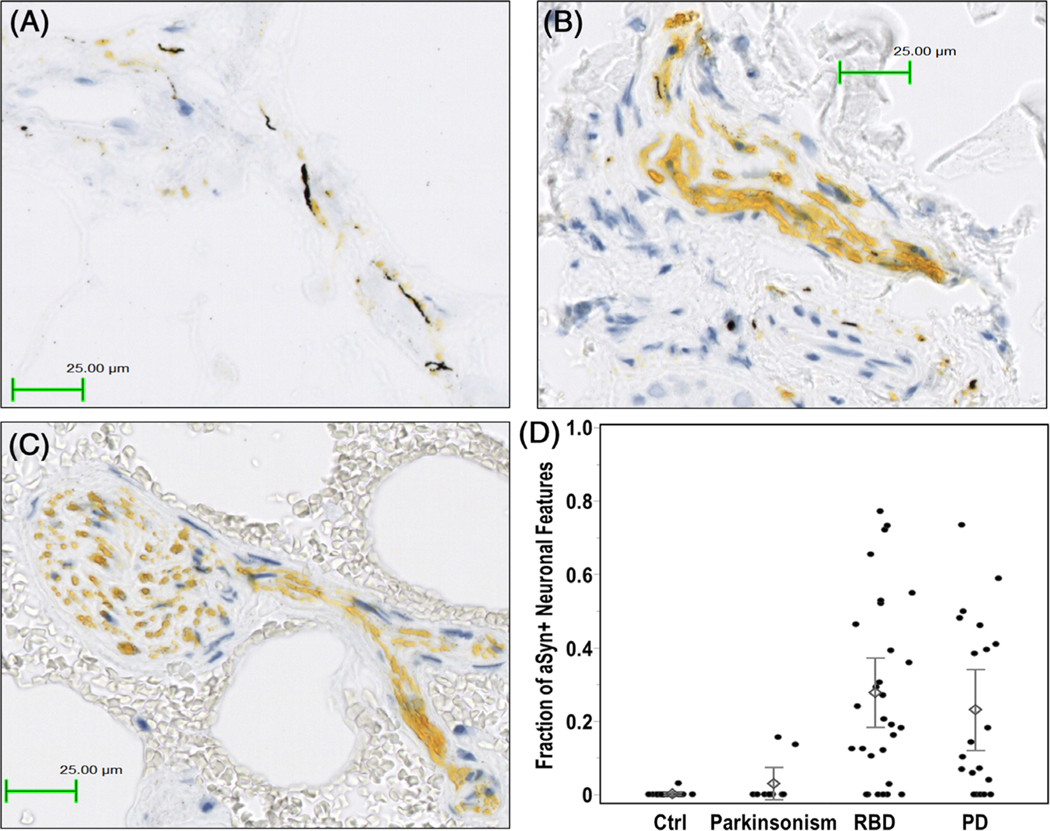

Skin Biopsy In Vivo

The same dual-IHC assay that included protease and phosphatase pretreatment was used to stain FFPE skin biopsies from 79 subjects (28 iRBD, 20 PD, 10 atypical parkinsonism, and 21 control subjects). Patient characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Demographic variables were similar between groups, except that controls were slightly younger (mean age = 60.8 vs 67.3 years in the other groups). Representative IHC images from the biopsy procedure are shown in Fig. 4A–C. A scatterplot showing the proportion of aSyn-positive neuronal features for each patient is shown in Fig. 4D. Overall, the average proportion of individual nerve features positive for aSyn was 27.8% in iRBD and 23.1% in PD, compared with 2.9% in atypical parkinsonism and 0.1% in controls (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.002 for control subjects compared with subjects with iRBD and PD, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Living subjects clinical characteristics and skin biopsy samples results

| Control (n = 21) | Idiopathic RBD (n = 28) | PD (n = 20) | Atypical Parkinsonism (n = 10) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | A | B | C | D | Significant differencesa |

|

| |||||

| Age, yr | 60.8 (8.2) | 67.4 (11.9) | 66.7 (9.8) | 68.3 (11.9) | |

| Sex, % men | 47.6 | 71.4 | 65.0 | 30.0 | |

| Disease duration, mo | n/a | n/a | 101.2 (52.7) | 94.2 (61.7) | |

| Total MDS-UPDRS Part III | 1.3 (1.8) | 7.8 (7.7) | 23.8 (10.2) | 43.1 (22.1) |

P < 0.0001 C > A, D > A, D > C, D > B, C > B |

| Orthostatic systolic blood pressure decline, mm Hg | 1.7 (13.8) | 13.6 (17.9) | 14.1 (20.1) | 12.0 (7.2) | |

| SCOPA-AUT total score | 6.2 (5.7) | 13.5 (7.1) | 12.9 (6.9) | 18.1 (10.5) |

P = 0.02 B, C, D > A |

| MoCA total score | 26.4 (3.6) | 26.8 (3.3) | 27.2 (3.0) | 24.4 (3.6) | |

| Average nerve fiber count on a slide | 4.0 (1.0) | 4.4 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.3) | 4.4 (1.3) | P = 0.04 B > C |

| Proportion of neuronal features positive | 0.001 (0.007) | 0.28 (0.25) | 0.24 (0.24) | 0.03 (0.06) | P < 0.05, all pairs between (A, D) and (B, C) |

| Skin biopsy positive, n (%)b | 0 (0) | 23 (82.1) | 14 (70) | 2 (20) | |

Results are presented as mean (standard deviation) except for sex and skin biopsy positive.

Abbreviations: RBD, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder; PD, Parkinson’s disease; MDS-UPDRS, Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale; SCOPA-AUT, Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease—Autonomic; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; na, not applicable.

P values refer to significant differences between groups as assessed by Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference all pairs comparison test.

Result of the primary diagnostic classification.

FIG. 4.

Example of colocalization of pathological alpha-synuclein (aSyn) deposition (silver black stain) in neuronal structures (dabcyl yellow stain) from skin biopsies of (A) a subject with PD and (B) a subject with idiopathic RBD. In contrast, skin biopsy from (C) a control subject exhibited only dabcylstained protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5) without silver-stained pathological aSyn. (D) Scatterplot of the proportion of pathological aSyn positivity in PGP9.5-positive neuronal features in each biopsy sample (using all eight sections per subject) classified according to diagnostic status. Diamonds represent average proportion of pathological aSyn-positive neuronal features. Error bars correspond to ±1 standard error from the corresponding mean value. Ctrl, control; PD, Parkinson’s disease; RBD, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder.

Using first the maximized sensitivity approach (all eight slides examined, any positive aSyn = positive biopsy), pathological aSyn could be detected in 23 of 28 (82%) subjects with iRBD and in 15 of 20 (75%) subjects with PD. One of the biopsy-negative patients with PD was later found to have PD caused by parkin mutations (deletion in exon 3 and K161N). There was a single positive slide among the 21 control subjects, with one aSyn-positive neuronal feature on the seventh examined slide (overall 1 positive out of 33 analyzed nerve features). This subject had normal cognitive testing: Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale Part II and III scores = 0 and Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease–Autonomic = 7 (mild sexual and cardiovascular symptoms).21 Pathological aSyn was also detected in 2 of 10 (20%) patients with atypical parkinsonism (one with a clinical diagnosis of MSA and one with PSP; additional details are available in the Discussion). Using the optimized specificity approach (≥2 positive features in four slides), biopsies were positive in 22 of 28 (78%) subjects with iRBD, 11 of 20 (55%) subjects with PD, none of the 10 (0%) subjects with atypical parkinsonism, and none of the 21 (0%) control subjects.

Finally, using the primary diagnostic definition, the biopsy was positive in 23 of 28 (82%) subjects with iRBD, 14 of 20 (70%) subjects with PD, 2 of 10 (20%) subjects with atypical parkinsonism, and none of the 21 (0%) control subjects.

Correlates of Biopsy

Supporting Information Table S3 shows clinical characteristics of biopsy-positive and -negative subjects in patients with Lewy body disease (iRBD and PD groups combined) using the primary diagnostic definition. Biopsy-positive subjects were older by 9.3 years (P = 0.018). Other baseline characteristics were not significantly different. However, biopsy-positive subjects tended to have higher orthostatic systolic blood pressure decline, lower Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and lower University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) scores. Comparing iRBD and PD groups separately, similar trends were seen without statistical significance (Supporting Information Tables S4 and S5). Among the PD group, eight (80%) of those with RBD symptoms had positive skin biopsy compared with six (60%) of those without. In bivariate analysis correlating the ratio of aSyn-positive neuronal features and baseline clinical characteristics, the only significant correlation was with age (Spearman’s Rho coefficient = 0.328, P = 0.023, iRBD and PD groups combined), with a nonsignificant trend toward a lower MoCA score and positive biopsy (Spearman = −0.283, P = 0.051). Among patients with iRBD, UPSIT score was negatively correlated with the ratio of aSyn-positive neuronal features (Spearman’s coefficient = −0.376, P = 0.049). Among patients with PD, there was no correlation between the ratio of aSyn-positive neuronal features and disease duration and/or severity.

Prospective Follow-up in iRBD

Since biopsy, 8 of 28 (28.6%) patients with iRBD phenoconverted to defined neurodegenerative disease over a mean 3.0-year follow-up. Six of eight had positive biopsy results. All of those with positive biopsy were clinically diagnosed with Lewy body disease (four with PD and two with DLB, both of whom also met criteria for PD). Of the phenoconvertors with a negative biopsy, one was diagnosed with probable MSA.22 The second had dementia with no parkinsonism, hallucinations, or fluctuations; she had multiple vascular risk factors, and the neuropsychological profile suggested mixed dementia (relatively preserved visuospatial function, predominant memory involvement, without improvement by recall cues). Both patients with negative biopsies had normal olfaction at the time of phenoconversion.

Discussion

Using a novel pS129-aSyn and PGP9.5 silver/yellow dual-IHC assay, we demonstrated cutaneous pathological aSyn deposition in 23 of 28 (82.1%) subjects with polysomnography-confirmed iRBD, 14 of 20 (70%) subjects with PD, 2 of 10 (20%) subjects with atypical parkinsonism (MSA and PSP), and none of the 21 control subjects. These results were similar to those obtained from two separate cohorts of autopsy-confirmed PD. This suggests that skin biopsy may be a valuable tool to identify PD, even in its prodromal stages, and may help researchers in selection of prodromal subjects for clinical trials of disease-modifying therapies.

The dual-IHC assay for pS129-aSyn and PGP9.5 offers several advantages. First, the assay can be deployed on an automated staining platform commonly available in diagnostic anatomical pathology laboratories. This provides the possibility that detection of peripheral synucleinopathy could be included in the future as part of the routine PD diagnosis. Second, pathological aSyn produces a staining pattern in skin tissue that resembles short jagged lines or small dots (Figs. 1 and 2). Such small features could be easily missed with conventional staining techniques. Even though detection of PGP9.5 in FFPE skin tissue using EPR4118 antibody required the added step of heat-induced epitope retrieval (Supporting Information Figure S5), the resulting yellow stain helped to visualize pathological aSyn. Comparison of a nerve feature in sequentially sectioned slides presenting pathological aSyn stained with this dual silver/yellow chromogen combination or with just 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Supporting Information Fig. S6) demonstrates the comparative ease with which silver-stained pS129-aSyn can be recognized by its close proximity to yellow chromogen. Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity of the dual assay may have been enhanced by using alkaline phosphatase as pretreatment. This finding is consistent with prior literature showing nonpathological aSyn is sensitive to specific protein phosphatases, whereas aggregated pathological aSyn is resistant to multiple phosphatases.20,23–25 Use of alkaline phosphatase was based on its stability, but it has been shown to act as protein phosphatase.26

Two prior studies have shown premortem pathological aSyn in skin biopsies of subjects with iRBD.15,16 In one study, 10 of 18 (55.6%) subjects with iRBD, 20 of 25 (80%) subjects with early PD, and none of the 20 (0%) control subjects had positive skin biopsy. The second study found positive biopsies in 9 of 12 (75%) subjects with iRBD and none of the 55 (0%) control subjects. Both studies used multiple proximal and distal sites (cervical C7/C8 and legs) with different skin biopsy sizes and section thicknesses. In our study, we obtained comparable detection rates even with a single small 3-mm skin biopsy from the C8 paravertebral area (a size sufficiently small so that stitching is not required). We chose the proximal site based on prior studies that found a gradient of rostrocaudal spread of pathological aSyn.3,15 One of the factors that may have allowed a high yield despite the 3-mm sample was the requirement to ensure sufficient sampling of nervous system tissue before a biopsy was called negative. Without this, diagnostic yield would have decreased slightly to 12 of 20 (60%) subjects with PD and 22 of 28 (78.5%) subjects with iRBD. Notably, our sensitivity analysis to assess effects of sensitivity/specificity maximization produced only modest differences in results, suggesting that findings were relatively insensitive to alterations in diagnostic criteria.

The two prior studies demonstrating pathological aSyn deposition in skin biopsies of subjects with iRBD shared common biomarker targets to this study: pS129-aSyn and PGP9.5.15,16 This commonality demonstrates the suitability of pS129-aSyn as a surrogate biomarker to detect pathological aSyn. Beyond these similarities, the methods for detecting pathological aSyn had important differences. First, this study used a bright-field IHC approach, whereas the two prior studies used dark-field immunofluorescence. Second, the assay in this study must rely on phosphatase and protease pretreatments to remove nonpathological pS129-aSyn. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S7A,C, pS129-aSyn was observed in innervated skin structures in both PD and control subjects. However, pS129-aSyn persisted in PD skin after sequential phosphatase and protease pretreatments (Supporting Information Fig. S7B), but not in control skin (Supporting Information Fig. S7D). The two prior studies did not report use of phosphatase or protease pretreatment; it is unclear why dark-field detection of pathological aSyn may not require this, whereas bright-field detection does.

It is notable that the ratio of positive biopsies was at least as high in iRBD as in PD, and possibly higher. There have been numerous studies that document severe autonomic dysfunction in RBD, which is often worse than that seen in PD.11,27 Within PD, RBD marks a “diffuse malignant” subtype of PD, with more severe autonomic dysfunction28,29 and more extensive deposition of pathological synuclein on autopsy.30 Another potential explanation for negative biopsies in PD could be related to loss of neuronal skin terminals in advanced PD rendering the skin biopsy negative.31 If intraepidermal nerve fiber density in PD degenerates, there could be potential signal dropout; this is one of the reasons that it is critical to ensure adequate sampling of neuronal tissue, as was required in our diagnostic algorithm.32 Notably, some genetic forms of PD do not have evident aSyn pathology in the brain,33 and in our study, our patient with parkin-related PD also had a negative skin biopsy. Furthermore, it is possible that some of the PD diagnoses were incorrect, and the negative skin biopsy indicates misdiagnosis. Finally, the clinical diagnosis of PD is not always confirmed neuropathologically and may be only 50%–70% accurate at early stages.34,35

Concerning the two patients with atypical parkinsonism with positive biopsies, both had very high certainty of diagnosis with classic features of PSP and MSA. For the patient with PSP, response to levodopa was partial but suboptimal, and backward falls developed within 2 years of diagnosis. On our initial examination (5 years of disease duration), there was classic downward-vertical gaze palsy, absent optokinetic nystagmus, and eyelid apraxia. Therefore, the patient clearly met criteria for probable PSP with Richardson’s syndrome.36 However, this patient also had originally presented with a rest tremor that was typical of PD, and at our most recent visit, had recently experienced visual hallucinations and paranoia that responded to cholinesterase inhibition. This suggests a possibility of true dual pathology, as has been reported in 10% of PSP cases.37 The patient with MSA had no levodopa response and had clear features of RBD, orthostatic hypotension, and cerebellar abnormalities. Prior studies have shown conflicting evidence of pathological aSyn deposition in the skin of patients with MSA.6,38 With regard to the five patients with iRBD with negative biopsy (17.9%), this is a finding similar to prior studies.15,16 In addition to simple false negatives related to early disease stage, this may also reflect the small percentage of patients with iRBD who may not convert to defined neurodegenerative disease.12

We detected few differences between subjects with PD or iRBD with and without positive skin biopsy; this may be because of the high prevalence of positive biopsies, which limited statistical power. There was a modest correlation between positive neuronal feature ratio and age across subjects with iRBD and PD, and an inverse correlation with olfaction (UPSIT score) among the iRBD group, similar to what was seen in a recent study.16 A possible trend was seen between positive biopsies, orthostatic systolic blood pressure decline, and MoCA. Similar orthostatic blood pressure correlation was seen in subjects with PD with positive pathological aSyn skin biopsy.39

Our study is the first to include prospective follow-up of phenoconversion relative to biopsy results in iRBD. Each of the six patients who converted to defined Lewy body disease had a positive skin biopsy at baseline. Interestingly, one phenoconvertor with negative biopsy experienced development of probable MSA, perhaps suggesting that skin pathology may be less common or emerge later in the course of MSA than in PD. The second phenoconvertor had an uncertain clinical diagnosis; although she met new consensus criteria for probable DLB (like all patients with dementia with polysomnography-confirmed RBD40), the atypical clinical picture plus the strong vascular risk factors could suggest an important contribution of nonsynuclein pathology.

There are limitations to our study. Compared with other studies, we used a single biopsy site; using multiple sites may have increased sensitivity further. Despite this, the detection rate was comparable with prior studies.15,16 Sample size was too small to sufficiently evaluate correlations between skin biopsy results and clinical characteristics, particularly given the high positivity rate. The final diagnostic algorithm, although blinded to the effects of algorithm decisions on the ultimate diagnosis, was not blinded to overall biopsy results (ie, one needs to understand the parameters in order to optimize them). However, results were robust regardless of diagnostic algorithm; among the potential classifications (primary, maximal sensitivity, optimized specificity), final biopsy diagnosis was the same in all three categories for 27 of 28 subjects with iRBD, 16 of 20 subjects with PD, 8 of 10 subjects with atypical parkinsonism, and 20 of 21 control subjects.

In summary, even with a single 3-mm skin biopsy from C8 paravertebral area, we detected a high rate of pathological aSyn deposition in both iRBD and PD using a novel automated bright-field dual-IHC assay. Longitudinally, 29% of subjects with iRBD phenoconverted to specific neurodegenerative syndromes in concordance with their prior skin biopsy results. There is considerable promise for skin biopsy as a specific marker of synucleinopathy and as a potential selection criterion for clinical trials of synuclein-based therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program of Sun City, Arizona, for the provision of human autopsy-derived tissue. The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901, and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium), and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Full financial disclosures and author roles may be found in the online version of this article.

Footnotes

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: T.-S.T., A.R., M.A.S., R.C.B., H.Z., J.M., J.P., F.L., M.D.R., L.P.-D., and L.T. performed the work associated with this manuscript as employees or contractors of Roche Tissue Diagnostics. M.R. performed the work associated with this manuscript as employee of Roche Centralised and Point of Care Solutions. T.K., C.C., M.C., K.I.T., A.B., and S.D. performed the work associated with this manuscript as employees of Hoffmann-La Roche. W.Z. performed the work associated with this manuscript as an employee of Prothena Biosciences. T.G.B. was a paid consultant to Roche Tissue Diagnostics for advice contributing to the development of the methodology reported herein.

Supporting Data

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

References

- 1.Lindberg I, Shorter J, Wiseman RL, Chiti F, Dickey CA, McLean PJ. Chaperones in neurodegeneration. J Neurosci 2015;35(41):13853–13859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witt SN. Molecular chaperones, alpha-synuclein, and neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol 2013;47(2):552–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doppler K, Ebert S, Uceyler N, et al. Cutaneous neuropathy in Parkinson’s disease: a window into brain pathology. Acta neuropathol 2014;128(1):99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beach TG, Adler CH, Serrano G, et al. Prevalence of submandibular gland Synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and other Lewy body disorders. Parkinson’s Dis 2016;6(1):153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donadio V, Incensi A, Leta V, et al. Skin nerve alpha-synuclein deposits: a biomarker for idiopathic Parkinson disease. Neurology 2014;82(15):1362–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doppler K, Weis J, Karl K, et al. Distinctive distribution of phospho-alpha-synuclein in dermal nerves in multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord 2015;30(12):1688–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbons CH, Garcia J, Wang N, Shih LC, Freeman R. The diagnostic discrimination of cutaneous alpha-synuclein deposition in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2016;87(5):505–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surguchov A Parkinson’s disease: assay of phosphorylated alpha-Synuclein in skin biopsy for early diagnosis and association with melanoma. Brain Sci 2016;6(2):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang N, Gibbons CH, Lafo J, Freeman R. Alpha-Synuclein in cutaneous autonomic nerves. Neurology 2013;81(18):1604–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Invited article: nervous system pathology in sporadic Parkinson disease. Neurology 2008;70(20):1916–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Pelletier A, Montplaisir J. Prodromal autonomic symptoms and signs in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Mov Disord 2013;28(5):597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postuma RB, Iranzo A, Hogl B, et al. Risk factors for neurodegeneration in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a multicenter study. Ann Neurol 2015;77(5):830–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iranzo A, Fernández-Arcos A, Tolosa E, et al. Neurodegenerative disorder risk in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: study in 174 patients. PLoS One 2014;9(2):e89741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Postuma RB, Iranzo A, Hu M, et al. Risk and predictors of dementia and parkinsonism in idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder: a multicentre study. Brain 2019;142(3):744–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antelmi E, Donadio V, Incensi A, Plazzi G, Liguori R. Skin nerve phosphorylated alpha-synuclein deposits in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 2017;88(22):2128–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doppler K, Jentschke HM, Schulmeyer L, et al. Dermal phosphor-alpha-synuclein deposits confirm REM sleep behaviour disorder as prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 2017;133(4):535–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, et al. Arizona study of aging and neurodegenerative disorders and brain and body donation program. Neuropathology 2015;35(4):354–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2015;30(12):1591–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickson DW. Misfolded, protease-resistant proteins in animal models and human neurodegenerative disease. J Clin Invest 2002;110(10):1403–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waxman EA, Giasson BI. Specificity and regulation of casein kinase-mediated phosphorylation of alpha-synuclein. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2008;67(5):402–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visser M, Marinus J, Stiggelbout AM, Van Hilten JJ. Assessment of autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: the SCOPA-AUT. Mov Disord 2004;19(11):1306–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology 2008;71(9):670–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braithwaite SP, Voronkov M, Stock JB, Mouradian MM. Targeting phosphatases as the next generation of disease modifying therapeutics for Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Int 2012;61(6):899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KW, Chen W, Junn E, et al. Enhanced phosphatase activity attenuates alpha-synucleinopathy in a mouse model. J Neurosci 2011;31(19):6963–6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taymans JM, Baekelandt V. Phosphatases of alpha-synuclein, LRRK2, and tau: important players in the phosphorylation-dependent pathology of parkinsonism. Front Genet 2014;5:382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinozaki T, Watanabe H, Arita S, Chigira M. Amino acid phosphatase activity of alkaline phosphatase. A possible role of protein phosphatase. Eur J Biochem 1995;227(1–2):367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kashihara K, Imamura T, Shinya T. Cardiac 123I-MIBG uptake is reduced more markedly in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder than in those with early stage Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16(4):252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fereshtehnejad SM, Romenets SR, Anang JB, Latreille V, Gagnon JF, Postuma RB. New clinical subtypes of Parkinson disease and their longitudinal progression: a prospective cohort comparison with other phenotypes. JAMA Neurol 2015;72(8):863–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fereshtehnejad SM, Zeighami Y, Dagher A, Postuma RB. Clinical criteria for subtyping Parkinson’s disease: biomarkers and longitudinal progression. Brain 2017;140(7):1959–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Postuma RB, Adler CH, Dugger BN, Hentz JG, Shill HA, Driver-Dunckley E, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder and neuropathology in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2015;30: 1413–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orimo S, Uchihara T, Nakamura A, et al. Axonal alpha-synuclein aggregates herald centripetal degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerve in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2008;131(Pt 3):642–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolano M, Provitera V, Manganelli F, et al. Loss of cutaneous large and small fibers in naive and l-dopa-treated PD patients. Neurology 2017;89(8):776–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulopoulos M, Levy OA, Alcalay RN. The neuropathology of genetic Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2012;27(7):831–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beach TG, Adler CH. Importance of low diagnostic accuracy for early Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2018;33:1551–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adler CH, Beach TG, Hentz JG, et al. Low clinical diagnostic accuracy of early vs advanced Parkinson disease: clinicopathologic study. Neurology 2014;83:406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Höglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: the movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord 2017;32(6):853–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uchikado H, DelleDonne A, Ahmed Z, Dickson DW. Lewy bodies in progressive supranuclear palsy represent an independent disease process. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2006;65(4):387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zange L, Noack C, Hahn K, Stenzel W, Lipp A. Phosphorylated alpha-synuclein in skin nerve fibres differentiates Parkinson’s disease from multiple system atrophy. Brain 2015;138(Pt 8):2310–2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donadio V, Incensi A, Del Sorbo F, et al. Skin nerve phosphorylated α-Synuclein deposits in Parkinson disease with orthostatic hypotension. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2018;77(10):942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB consortium. Neurology 2017;89(1):88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.