Abstract

There are two ‘pathways’ of replication of λ plasmids in Escherichia coli. One pathway requires the assembly of a new replication complex before replication and the second pathway is based on the activity of the replication complex inherited by one of two daughter plasmid copies after a preceding replication round. Such a phenomenon was postulated to occur also in other replicons, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae autonomously replicating sequences. Here we investigated directionality of λ plasmid replication carried out by the heritable and newly assembled replication complexes. Using two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis and electron microscopy we demonstrated that in both normal growth conditions and during the relaxed response to amino acid starvation (when only replication carried out by the heritable complex is possible), bidirectionally and undirectionally replicating plasmid molecules occurred in host cells in roughly equal proportions. The results are compatible with the hypothesis that both complexes (heritable and newly assembled) are equivalent.

INTRODUCTION

Plasmids derived from bacteriophage λ, called λ plasmids, bear a replication region of the phage genome and can replicate by the θ (theta, circle-to-circle) mode in Escherichia coli cells as regular plasmids. The λ replication region contains all genes and regulatory sequences necessary for initiation of DNA replication from oriλ, located in the middle of the O gene, which codes for the replication initiator protein (for a review see 1).

When bacteriophage λ genome or λ plasmid enter an E.coli cell, an assembly of the replication complex at oriλ is necessary for λ DNA replication. The first step of this assembly is binding of the O protein to the oriλ region. Then another λ-encoded protein, P, delivers the host-encoded helicase, DnaB, to this region. For initiation of DNA replication, the action of molecular chaperones (DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE) is necessary to liberate DnaB from P-mediated inhibition (1).

Contrary to early assumptions that an assembly of the replication complex is necessary for each replication initiation event (2,3), experiments performed during the last 10 years demonstrate that after a replication round the replication complex is inherited by one of the two daughter λ plasmid copies rather than disassembled (4–8). It is likely that inheritance of the replication complex also occurs regularly during lytic development of bacteriophage λ (9). The inherited replication complex can function in the next replication round, thus an assembly of the replication complex is necessary only on one of the two daughter λ DNA copies, i.e. that devoid of the heritable complex. Interestingly, a similar phenomenon was postulated to occur also in some other replicons, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae autonomously replicating sequence (ARS), where the origin recognition complex remains bound to one copy of the replication origin after replication initiation and exists in such a form throughout the whole cell cycle (for reviews and discussions see 9,10). Therefore, the inheritance of the replication complex seems to be a more general phenomenon rather than a process restricted to λ.

The heritable λ replication complex contains the λ-encoded O protein, protected from proteolysis by other components of this complex, namely P, DnaB and possibly others (5,11,12). Otherwise, the O protein is rapidly degraded by the ClpP/ClpX protease (13–15). It was proposed that the action of molecular chaperones (DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE) on the pre-primosome, consisting of O, P and DnaB proteins, leads to a rearrangement of this structure in such a way that P no longer inhibits DnaB, rather than the physical disassembly of the pre-primosome as suggested previously (for a review and detailed discussion see 9). It seems clear that O must be protected from proteolysis by other proteins present in the pre-primosome as binding of the O protein to oriλ and formation of the nucleoprotein structure called O-some did not prevent the rapid degradation of this replication initiator protein mediated by the ClpP/ClpX protease both in vivo (11) and in vitro (12).

In amino acid-starved E.coli cells, synthesis of new molecules of the O protein is inhibited due to lack of amino acids, and the assembly of new λ replication complexes is abolished (6). Under these conditions λ plasmid replication is possible solely due to activity of the heritable replication complex. This replication requires transcriptional activation of oriλ (7,16,17). Therefore, it is inhibited in amino acid-starved relA+ hosts due to ppGpp-mediated inhibition of transcription from the pR promoter, which normally activates oriλ (18,19). On the other hand, λ plasmid replication proceeds in starved relA mutants that are deficient in ppGpp production (4,7,20).

An interesting question is whether the replication carried out by the heritable replication complex is identical to that driven by a newly assembled complex. One of the basic features of DNA replication is directionality of this process. The θ type of replication of a circular DNA molecule may be bidirectional or unidirectional (leftward or rightward). For most circular replicons it is generally believed that only one of these replication types occurs (for a review see 21). However, our recent studies revealed that among λ plasmid molecules that are maintained in E.coli cells some replicate bidirectionally and others replicate unidirectionally at the same time (22). Previous investigations indicated that the λ replication complex is randomly inherited by one of the two daughter plasmid copies rather than preferentially inherited by either the copy carrying the parental r strand or that containing the parental l strand (23). Therefore, one could consider a model in which λ plasmid replication carried out by the heritable replication complex is unidirectional (either leftward or rightward depending on the parental DNA strand which inherited the replication complex), and that carried out by a newly assembled complex is bidirectional, thus giving a mixture of unidirectionally and bidirectionally replicating molecules in a population of plasmids maintained in the host cells growing under standard laboratory conditions. Alternatively, both ‘pathways’ of λ plasmid replication could be equivalent, i.e. both unidirectional and bidirectional replications might be driven by the heritable as well as newly assembled replication complexes. To determine which of these two alternative possibilities is true, we investigated directionality of λ plasmid replication in E.coli relA+ hosts and relA mutants growing under normal conditions and in the amino acid-starved relA mutant, i.e. under conditions in which only the replication carried out by the heritable complex could occur.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and bacteriophage λ-derived plasmid

Escherichia coli K-12 strain CP78 (thr-1 leuB6 rfbD1 supE44 thi-1 lacY1 malT1 fhuA2 xyl-7 ara-13 mtlA2 osmZ1 gal-3 fic-1 his-65 argH46 relX) and its otherwise isogenic relA2 derivative, CP79 (24,25) were used. A standard λ plasmid, pKB2 (26), was employed.

Culture medium and amino acid starvation

Minimal medium 2 (for details see 4) was used. Isoleucine starvation was induced by addition of l-valine to a final concentration of 1 mg ml–1, as described previously (4).

Replication of plasmid DNA in amino acid-starved bacteria

Plasmid DNA replication in amino acid-starved bacteria was investigated by isolation of total DNA from cells, agarose gel electrophoresis and analysis of plasmid bands on an electrophoregram, as described previously (4).

Two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis

Analysis of replication intermediates by two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis (2D-AGE) was performed according to a method described previously (27), with modifications described subsequently (28).

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy analysis of replicating plasmid DNA molecules was performed as described previously (29,30).

RESULTS

Isolation of λ plasmid replication intermediates

For investigation of directionality of DNA replication of λ plasmids carried out by both heritable and newly assembled replication complexes, plasmid DNA was isolated from unsynchronized cultures of the relA+ and relA2 hosts. Very gentle cell lysis and DNA purification procedures (27,30) were employed to obtain a reasonable number of replication intermediates for analysis.

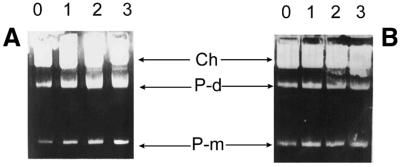

For investigation of directionality of λ plasmid replication carried out exclusively by the heritable replication complexes, plasmid DNA was isolated from cultures of the relA2 mutant, and the samples were withdrawn 1 h after onset of amino acid starvation. In accordance with previous reports (4,7,20) we observed the inhibition of λ plasmid replication in isoleucine-starved relA+ cells (Fig. 1; as an equal cell mass was used for DNA isolation from each sample and amino acid starvation caused inhibition of bacterial growth, an increase in the intensity of plasmid bands indicates plasmid DNA replication whereas a constant amount of plasmid DNA indicates the inhibition of plasmid replication). Therefore, material from the amino acid-starved relA+ strain was not investigated further.

Figure 1.

Replication of the λ plasmid, pKB2, in amino acid-starved relA2 (A) and relA+ (B) hosts. Bacteria were grown in a minimal medium, isoleucine starvation was induced at time 0 and samples of equal cell mass (1 OD unit) for total DNA isolation were withdrawn at 1, 2 and 3 h after onset of the starvation. Numbers above lanes represent these times. Plasmid monomers and dimers, and chromosomal DNA bands are indicated as P-m, P-d and Ch, respectively.

Analysis of directionality of λ plasmid replication by 2D-AGE

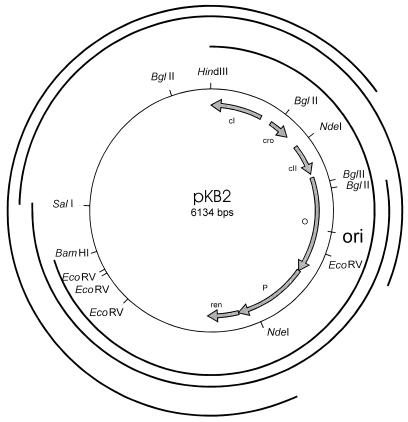

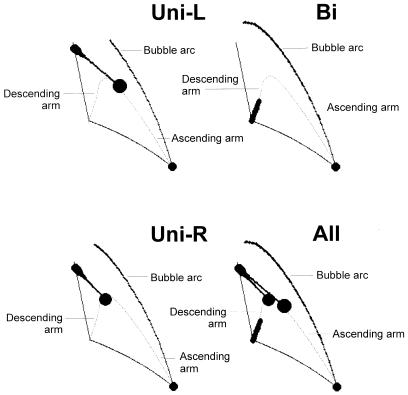

Following isolation of plasmid pKB2 from E.coli cells (as described above), DNA was digested with different restriction enzymes (Fig. 2) and analyzed by 2D-AGE. Theoretical patterns of λ plasmid (pKB2) replication intermediates in the case of bidirectional and unidirectional (leftward and rightward) replication in samples digested with HindIII and BamHI, predicted by a computer method (31) and assuming that replication forks initiate synchronously and travel at the same rate for each direction, are presented in Figure 3. Examples of electrophoregrams and their interpretations are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 2.

Map of the λ plasmid, pKB2, used in this work with indicated restriction sites and fragments used as probes (external circles) in 2D-AGE and employed in electron microscopic studies.

Figure 3.

Theoretical schemes of expected pictures of 2D-AGE of λ plasmid (pKB2), digested with HindIII and BamHI, replicating according to unidirectional leftward θ mode (Uni-L), unidirectional rightward θ mode (Uni-R), bidirectional θ mode (Bi) and a combination of molecules replicating according to all these modes (All). The schemes were obtained using a computer model for the analysis of DNA replication intermediates by 2D-AGE (31), and considering particular pictures, which might appear after digestion of pKB2 replication intermediates with certain restriction enzymes followed by 2D-AGE.

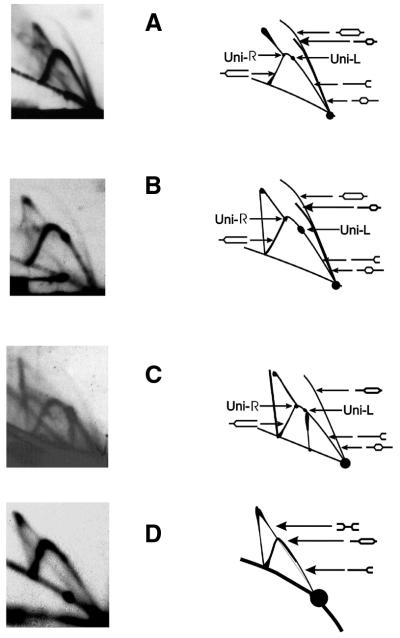

Figure 4.

2D-AGE analysis of directionality of replication of the λ plasmid, pKB2, in non-starved relA+ cells (A), non-starved relA2 mutant (B) and isoleucine-starved relA2 mutant (C and D). The experiments in which HindIII and BamHI (A–C) or NdeI (D) digestions were performed are shown. Left panels represent autoradiograms and right panels show their interpretation. ‘Uni-R’ and ‘Uni-L’ denote dots characteristic for rightward and leftward unidirectional replication, respectively. Positions of DNA molecules of particular shapes are indicated by arrows.

In relA+ and relA2 cells growing under normal conditions (Fig. 4A and B, respectively), replication of the λ plasmid proceeded both bidirectionally and unidirectionally. In the case of digestion of plasmid pKB2 with HindIII and BamHI (Fig. 4A and B), bidirectional replication is represented by the characteristic shape of the bubble arc and the intense descending arm of the simple-Y arc. The dots at the top and at the ascending arm of the simple-Y arc indicate rightward and leftward unidirectional replication, respectively. The intensities of these dots suggest that the leftward replication is somewhat more frequent than the rightward replication in both relA+ and relA2 hosts growing under normal conditions (Fig. 4A and B).

Similar results were obtained during analysis of plasmid replication intermediates isolated from amino acid-starved relA2 cells and digested with HindIII and BamHI (Fig. 4C). The bubble arc was less intense due to a smaller fraction of replicating plasmid molecules among all plasmid DNA molecules relative to bacteria growing under normal conditions (this is compatible with the model of the replication carried out exclusively by the heritable replication complex as the same number of active complexes produces more and more DNA molecules of which only half are able to replicate again; 9). Nevertheless, features characteristic for both bidirectional and unidirectional replications could be observed, similarly to experiments with non-starved cells. The bidirectional replication was further confirmed by the presence of a clear double-Y pattern in the large NdeI fragment, which does not contain the origin region (Fig. 4D). Rightward and leftward replication was also confirmed by the detection of juxtaposed but not coincidental bubble arcs, i.e. the double bubble arc (Fig. 5). One of these bubble arcs ended earlier than the other (Fig. 5). As a result of the relatively low intensity of the double bubble arc, such a pattern was detected only when gels were overexposed (Fig. 5). Therefore, other signals could not be analyzed from such overexposed autoradiograms, as they required a significantly shorter exposure time (compare Figs 4C and 5).

Figure 5.

Overexposure of the gel obtained after 2D-AGE of the λ plasmid, pKB2, isolated from isoleucine-starved relA2 cells and digested with HindIII and BamHI (compare with Fig. 4C). The left panel represents the autoradiogram and the right panel shows its interpretation (analogously to pictures presented in Fig. 4). The juxtaposed but not coincidental bubble arcs are visible; however, other signals are too strong to be analyzed. Very similar patterns were obtained when plasmid pKB2 was isolated from non-starved relA+ and relA2 cells (data not shown).

Experiments analogous to those presented in Figures 4 and 5 but using different restriction enzymes (Fig. 2) were performed. The results of these experiments led to the same conclusion, i.e. the presence of intermediates of bidirectional and unidirectional DNA replication in all experimental systems employed (data not shown). This indicates that bidirectional and unidirectional replication of bacteriophage λ-derived plasmids occur simultaneously both in normal growth conditions of the host and in amino acid-starved relA mutants. The only considerable difference between λ plasmid replication in cells growing under normal conditions and during the relaxed response is that in amino acid-starved relA2 bacteria the rightward replication seems to be somewhat more frequent than the leftward replication, just the opposite to the pattern observed in non-starved cells (compare intensities of dots at the top and at the ascending arm of the simple-Y arc in Fig. 4A–C).

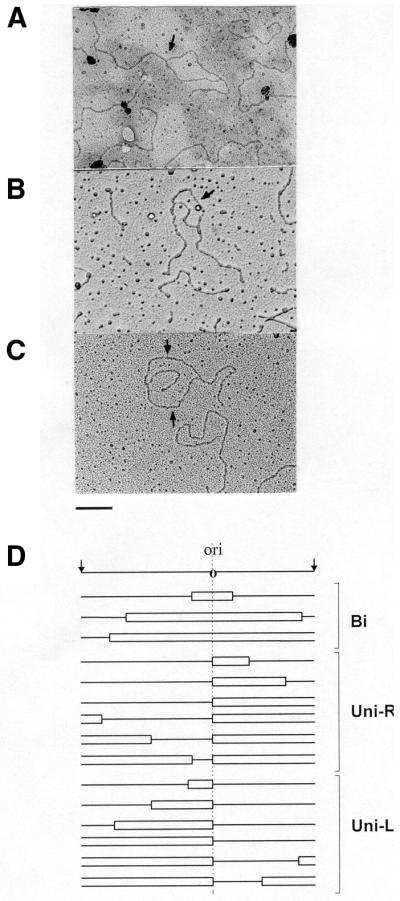

Analysis of directionality of λ plasmid replication by electron microscopy

2D-AGE analysis demonstrated little difference between the directionality of replication of populations of λ plasmids in non-starved and amino acid-starved cells. To obtain quantitative data, we analyzed λ plasmid molecules using electron microscopic techniques. Plasmid DNA molecules isolated from bacteria were cut with different restriction enzymes (Fig. 2) and analyzed in the electron microscope. DNA fragments containing the oriλ region located asymmetrically, thus allowing determination of replication directionality on the basis of analysis of replication intermediates, were considered. The origin-bearing fragments of molecules that contained bubbles, as well as Y-shaped oriλ-containing DNA fragments, were identified and the lengths of appropriate arms were measured. For determination of directionality of replication, the position of oriλ was assumed as the only possible replication start point. Thus, we could determine the fractions of bidirectionally and unidirectionally replicating plasmids. Examples of replication intermediates found under electron microscopy and a gallery of representative results of experiments in which plasmid pKB2 was linearized with BamHI are shown in Figure 6. Quantitative results of electron microscopic studies of replication intermediates obtained after λ plasmid (pKB2) digestion with different restriction enzymes are presented in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Examples of replication intermediates of the λ plasmid, pKB2, analyzed under an electron microscope (A–C) and a gallery of representative results obtained after measurement of lengths of fragments of DNA molecules (D). Following isolation of plasmid DNA from isoleucine-starved relA2 cells and digestion with BamHI, samples were prepared for electron microscopy. Examples of replication intermediates, which contain bubbles indicating unidirectional (A) and bidirectional (B and C) DNA replication, are presented. Positions of oriλ regions are shown by arrows. Bar represents 1 kb. Schemes of representative replication intermediates (grouped according to directionality of replication) are presented below the map of the investigated region with the oriλ region marked (D). Bi, bidirectional replication; Uni-R, unidirectional rightward replication; Uni-L, unidirectional leftward replication.

Table 1. Electron microscopic studies on the directionality of λ plasmid (pKB2) replication.

| Host and growth conditions | λ plasmid replication intermediatesa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of analyzed intermediates | Bidirectional replication (%) | Unidirectional replication (%) | |||

| Total | Leftward | Rightward | |||

| relA+ (non-starved) | 117 | 54 | 46 | 31 | 15 |

| relA2 (non-starved) | 157 | 60 | 40 | 25 | 15 |

| relA2 (starved for isoleucine) | 137 | 43 | 57 | 24 | 33 |

aFollowing isolation of plasmid DNA from relA+ and relA2 cells growing under different conditions, and digestion with different restriction enzymes, samples were prepared for electron microscopy. Directionality of replication was concluded on the basis of measurement of lengths of bubbles and branches of DNA replication intermediates.

In accordance with the results obtained during the analysis of 2D-AGE, we found that in all experimental systems (i.e. non-starved relA+ and relA2 hosts, and in the isoleucine-starved relA2 host) replication of λ plasmid DNA proceeded bidirectionally and unidirectionally. Proportions of bidirectionally and unidirectionally replicating molecules were similar. The electron microscopy studies also confirmed that the leftward replication is somewhat more frequent than the rightward replication in non-starved cells, whereas the rightward replication slightly predominates in amino acid-starved relA2 host (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The phenomenon of inheritance of the replication complex by one of two daughter DNA copies after a replication round, first described for λ plasmids (5,26), seems to occur in various replicons, including other bacterial plasmids (32) and S.cerevisiae ARSs (9,10). Once assembled, the λ replication complex can function for many cell generations (8). After each replication round it is inherited randomly by one of the two daughter plasmid copies rather than preferentially by either the copy carrying the parental r strand or that containing the parental l strand (23). However, it was not known whether the replication carried out by the heritable replication complex is identical to or different from the replication driven by a newly assembled replication complex.

One of the basic and important features of DNA replication is its directionality. λ plasmids are circular DNA molecules and replicate according to the θ mode (1). This replication mode may be either bidirectional or unidirectional. In most cases it is believed that a particular plasmid or virus replicates its DNA exclusively according to one of these two θ replication mechanisms (21,33). However, recently reported results of studies on λ DNA replication indicated that, in a population of λ plasmids maintained in E.coli cells, a fraction of molecules can replicate by the bidirectional θ mechanism, whereas other molecules replicate unidirectionally (22).

Here we demonstrate that directionality of replication of λ plasmids carried out by the heritable replication complex does not differ significantly from that carried out by a newly assembled replication complex. In cells supporting the two replication ‘pathways’ of λ plasmid DNA as well as under conditions in which only replication carried out by the heritable replication complex was possible, we observed plasmid molecules replicating by the bidirectional θ mechanism and molecules replicating unidirectionally. These results indicate that the kind of λ replication complex (heritable or newly assembled) does not determine the directionality of λ plasmid replication. This conclusion is compatible with the hypothesis that both complexes are equivalent.

It is interesting that in the absence of transcription, in vitro λ DNA replication was unidirectional and almost exclusively rightward (34,35). Addition of RNA polymerase to the reaction mixture switched the replication mode of a large fraction of λ plasmid molecules to bidirectional θ in vitro (35), and the strong influence of the efficiency of transcription proceeding through the oriλ region on directionality of λ plasmid replication has recently been confirmed in vivo (22). However, it is not clear what is the reason for the difference between the direction of the unidirectional θ replication of λ plasmids in vivo (which can be both leftward and rightward) and in vitro (which is mostly rightward).

Although transcriptional activation of oriλ undoubtedly stimulates bidirectional θ replication both in vitro (35) and in vivo (22), it seems that transcription of the λ replication region has little effect on the direction of the unidirectional θ replication, as under conditions of decreased activity of the pR promoter both leftward and rightward replication occurred efficiently (22). In amino acid-starved relA2 cells the unidirectional rightward replication intermediates were more abundant than molecules replicating leftward, contrary to the distribution of unidirectionally replicating plasmids in non-starved cells (Table 1). One might speculate that the conditions of the relaxed response (a response of relA mutants to amino acid starvation) resemble the in vitro replication conditions more closely than replication in normal growth conditions of the host cells. It is possible that a putative regulatory factor, which stimulates the leftward replication was absent in the in vitro replication assays, and it is less abundant in amino acid-starved cells, for instance due to impairment of its synthesis. One might speculate that the ClpP/ClpX complex could be a candidate for such a factor, as suggested on the basis of in vitro experiments (12). Nevertheless, further studies are necessary to test this hypothesis and to identify such a putative regulatory factor.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Polish State Committee for Scientific Research (project no. 6 P04A 016 16). S.B. and G.W. acknowledge financial support from the Foundation for Polish Science (a stipend for young scientists and subsidy 14/2000, respectively).

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor K. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1995) Replication of coliphage lambda DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 17, 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsubara K. (1981) Replication control system in lambda dv. Plasmid, 5, 32–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furth M.E. and Wickner,S. (1983) Lambda DNA replication. In Hendrix,R.W., Roberts,J.W., Stahl,F.W. and Weisberg,R.A. (eds), Lambda II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 145–173.

- 4.WÉgrzyn G., Neubauer,P., Krueger,S., Hecker,M. and Taylor,K. (1991) Stringent control of replication of plasmids derived from coliphage λ. Mol. Gen. Genet., 225, 94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WÉgrzyn G. and Taylor,K. (1992) Inheritance of the replication complex by one of two daughter copies during λ plasmid replication in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 226, 681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WÉgrzyn G., Pawßowicz,A. and Taylor,K. (1992) Stability of coliphage λ DNA replication initiator, the λO protein. J. Mol. Biol., 226, 675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szalewska-Paßasz A., WÉgrzyn,A., Herman,A. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1994) The mechanism of the stringent control of λ plasmid DNA replication. EMBO J., 13, 5779–5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WÉgrzyn A., WÉgrzyn,G., Herman,A. and Taylor,K. (1996) Protein inheritance: λ plasmid replication perpetuated by the heritable replication complex. Genes Cells, 1, 953–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WÉgrzyn A. and WÉgrzyn,G. (2001) Inheritance of the replication complex: a unique or common phenomenon in the control of DNA replication? Arch. Microbiol., 175, 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DePamphilis M.L. (1998) Initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotic chromosomes. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl., 30/31, 8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WÉgrzyn A., WÉgrzyn,G. and Taylor,K. (1995) Protection of coliphage λO initiator protein from proteolysis in the assembly of the replication complex in vivo. Virology, 207, 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.üylicz M., Liberek,K., Wawrzynów,A. and Georgopoulos,C. (1998) Formation of the preprimosome protects λ O from RNA transcription-dependent proteolysis by ClpP/ClpX. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 15259–15263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottesman S., Clark,W.P., de Crecy-Lagard,V. and Maurizi,M.R. (1993) ClpX, an alternative subunit for the ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 22618–22626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wojtkowiak D., Georgopoulos,C. and üylicz,M. (1993) Isolation and characterization of ClpX, a new ATP-dependent specificity component of the Clp protease of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 22609–22617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WÉgrzyn A., Czyg,A., Gabig,M. and WÉgrzyn,G. (2000) ClpP/ClpX-mediated degradation of the bacteriophage λ O protein and regulation of λ phage and λ plasmid replication. Arch. Microbiol., 174, 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szalewska-Paßasz A. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1994) An additional role of transcriptional activation of oriλ in the regulation of λ plasmid replication in Escherichia coli.Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 205, 802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WÉgrzyn A. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1995) Transcriptional activation of oriλ regulates λ plasmid replication in amino acid-starved Escherichia coli cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 214, 978–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wróbel B., Murphy,H., Cashel,M. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1998) Guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp)-mediated inhibition of the activity of the bacteriophage λpR promoter in Escherichia coli.Mol. Gen. Genet., 257, 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sßomiáska M., Neubauer,P. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1999) Regulation of bacteriophage l development by guanosine 5′-diphosphate-3′-diphosphate. Virology, 262, 431–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wróbel B. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1997) Replication and amplification of λ plasmids in Escherichia coli during amino acid starvation and limitation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 153, 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornberg A. and Baker,T.A. (1992) DNA Replication. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, NY.

- 22.Baraáska S., Gabig,M., WÉgrzyn,A., Konopa,G., Herman-Antosiewicz,A., Hernandez,P., Schvartzman,J.B., Helinski,D.R. and WÉgrzyn,G. (2001) Regulation of the switch from early to late bacteriophage λ DNA replication mode. Microbiology, 147, 535–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WÉgrzyn A. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1998) Random inheritance of the replication complex by one of two daughter λ plasmid copies after a replication round in Escherichia coli.Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 246, 634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiil N. and Friesen,J.D. (1968) Isolation of relaxed mutants of Escherichia coli.J. Bacteriol., 95, 729–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wróbel B., ìrutkowska,S. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1998) Biochemical and genetic analysis of λW, the newly isolated lambdoid phage. Acta Biochim. Pol., 45, 251–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kur J., Górska,I. and Taylor,K. (1987) Escherichia coli dnaA initiation function is required for replication of plasmids derived from coliphage lambda. J. Mol. Biol., 198, 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viguera E., Hernandez,P., Krimer,D.B., Boistov,A.S., Lurz,R., Alonso,J.C. and Schvartzman,J.B. (1996) The ColE1 unidirectional origin acts as a polar replication fork pausing site. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 22414–22421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ìrutkowska S., Caspi,R., Gabig,M. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1999) Detection of DNA replication intermediates after two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis using a fluorescein-labeled probe. Anal. Biochem., 269, 221–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burkardt H. and Lurz,R. (1984) Electron microscopy. In Puhler,A. and Timmis,K.N. (eds), Advanced Molecular Genetics. Springer Verlag, Berlin–Heidelberg, pp. 281–313.

- 30.ìrutkowska S., Konopa,G. and WÉgrzyn,G. (1998) A method for isolation of plasmid DNA replication intermediates from unsynchronized bacterial cultures for electron microscopy analysis. Acta. Biochim. Pol., 45, 233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viguera E., Rodríguez,A., Krimer,D.B., Hernández,P., Trelles,O. and Schvartzman,J.B. (1998) A computer model for the analysis of DNA replication intermediates by two-dimensional (2D) agarose gel electrophoresis. Gene, 217, 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potrykus K., Wrobel,B., Wegrzyn,A. and Wegrzyn,G. (2000) Replication of oriJ-based plasmid DNA during the stringent and relaxed responses of Escherichia coli. Plasmid, 44, 111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Del Solar G., Giraldo,R., Ruiz-Echevarria,M.J., Espinosa,M. and Diaz-Orejas,R. (1998) Replication and control of circular bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 62, 434–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mensa-Wilmot K., Seaby,R., Alfano,C., Wold,M.S., Gomes,B. and McMacken,R. (1989) Reconstitution of a nine-protein system that initiates bacteriophage λ DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 2853–2861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Learn B., Karzai,A.W. and McMacken,R. (1993) Transcription stimulates the establishment of bidirectional λ DNA replication in vitro. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 58, 389–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]