Abstract

The mechanism of light-induced spatial memory deficits, as well as whether rhythmic expression of the pituitary adenylyl cyclase-activating polypeptides (PACAP)-PAC1 pathway influenced by light is related to this process, remains unclear. Here, we aimed to investigate the role of the PACAP-PAC1 pathway in light-mediated spatial memory deficits. Animals were first housed under a T24 cycle (12 h light:12 h dark), and then light conditions were transformed to a T7 cycle (3.5 h light:3.5 h dark) for at least 4 weeks. The spatial memory function was assessed using the Morris water maze (MWM). In line with behavioral studies, rhythmic expression of the PAC1 receptor and glutamate receptors in the hippocampal CA1 region was assessed by western blotting, and electrophysiology experiments were performed to determine the influence of the PACAP-PAC1 pathway on neuronal excitability and synaptic signaling transmission. Spatial memory was deficient after mice were exposed to the T7 light cycle. Rhythmic expression of the PAC1 receptor was dramatically decreased, and the excitability of CA1 pyramidal cells was decreased in T7 cycle-housed mice. Compensation with PACAP1-38, a PAC1 receptor agonist, helped T7 cycle-housed mouse CA1 pyramidal cells recover neuronal excitability to normal levels, and cannulas injected with PACAP1-38 shortened the time to find the platform in MWM. Importantly, the T7 cycle decreased the frequency of AMPA receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents. In conclusion, the PACAP-PAC1 pathway is an important protective factor modulating light-induced spatial memory function deficits, affecting CA1 pyramidal cell excitability and excitatory synaptic signaling transmission.

Keywords: light, spatial memory, Morris water maze, PACAP-PAC1 pathway, CA1 pyramidal cell, excitability

Introduction

Light has profound effects on cognitive function in mammals. Aberrant changes in lighting conditions lead to physiological and behavioral dysfunctions, including deficits in circadian rhythm, learning, and memory (Huang et al., 2021; LeGates et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2022). Light influences mammalian behaviors through intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs), which receive light information; then through the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT), widespread projection to different targeting regions occurs, such as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the clock master (Juan et al., 2018; Fernandez et al., 2018; Gibson et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2007; Soler et al., 2018). Pituitary adenylyl cyclase-activating polypeptides (PACAP) and glutamate are coreleased from RHT terminals in response to photic stimulation (Hannibal et al., 2002; Hannibal et al., 2004). Extensive experimental data in mammals have shown that PACAP plays important roles in the regulation of learning and memory (Borbély et al., 2013). Ultradian light conditions, such as the T7 cycle (3.5 h light:3.5 h dark), may cause spatial memory impairment (Fernandez et al., 2018). However, the contribution of this neuropeptide with respect to the effects of ultradian light causing memory impairment is still unclear.

PACAP is a pleiotropic bioactive peptide belonging to the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)—secretin/glucagon superfamily that exists in the forms PACAP38 and PACAP27, sharing about 68% homology of its amino acid sequence with VIP (Harmar et al., 1998; Lee & Seo, 2014; Miyata et al., 1990). PACAP and VIP share two common G protein-coupled receptors, the VPAC1 receptor and VPAC2 receptor, while PACAP also has its specific receptor, PAC1-R. The equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) is the basic parameter to evaluate the binding property between ligands and receptors. The affinity of PAC1-R for PACAP38 and PACAP27 (Kd = 0.5 nM) is at least 1000 times greater than that for VIP (Kd > 500 nM) (Hirabayashi et al., 2018; Shivers et al., 1991). In addition, PACAP-PAC1 signaling is primarily activated by the neuropeptide PACAP-38, which is expressed 10-fold to 100-fold more abundantly than its truncated form PACAP-27 (Arimura et al., 1991; Harmar et al., 2012). PACAP and PAC1 are widely expressed in several brain regions, including the hippocampus, basolateral amygdala, and SCN, which play neuroprotective and neurotrophic roles in memory, contextual fear conditioning, and circadian rhythms (Hannibal et al., 2004; Sauvage et al., 2000; Schmidt et al., 2015). Multiple strains of transgenic animal models have been used to study the contribution of PACAP and the PAC1 receptor to these functions. Studies in PAC1 receptor knockout mice uncovered a deficit in contextual fear conditioning as assessed by the passive avoidance test, and PACAP-null mice displayed spatial working memory impairment in the Y-maze test (Ago et al., 2013; Otto et al., 2001). PACAP not only is coreleased with glutamate in the RHT tract but might also be synthesized by glutamatergic neurons (Fahrenkrug & Hannibal, 2004; Hannibal et al., 2000). Electrophysiological results have shown that the PACAP-PAC1 signaling pathway enhances NMDA and AMPA currents in CA1 pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus (Costa et al., 2009; Macdonald et al., 2005). In addition, cannula injection of PACAP and D-serine into the rat hippocampus resulted in the extinction of contextual fear conditioning mediated by glutamate NMDA receptors (Schmidt et al., 2015). All this evidence indicates a potential role for the PACAP-PAC1 pathway in learning and memory that might be involved in modulating glutamate signaling. Furthermore, previous studies have reported that the expression of PACAP and PAC1 receptor mRNA significantly varies during the light–dark cycle, and they display an autonomous rhythm that is influenced by light (Hannibal et al., 2017; Kalló et al., 2004).

Our preliminary experiments investigated the expression of the PAC1 receptor under the T7 cycle, comprised of alternating 3.5-h periods of light and darkness, which were significantly different from animals living under a normal T24 cycle light condition (12 h light:12 h dark). The animals breeding under the T7 cycle for approximately 21 days exhibited spatial memory impairment as assessed by the Morris water maze (MWM). To determine the relationship between ultradian light-influenced PACAP-PAC1 rhythmic expression and its function in ultradian light-induced memory impairment, we used in vivo behavioral tests, immunoblotting, and in vitro electrophysiology recordings combined with pharmacological treatments to detect the potential roles of the PACAP-PAC1 signaling pathway in modulating glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the CA1 region of the hippocampus.

Material and Methods

Mice

Male C57BL/6J mice (6–14 weeks) were used in this study and were given food and water ad libitum. The mice were primarily group-housed under a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle (T24) (lights on at 8:00 a.m.) at consistent humidity (50 ± 5%) and ambient temperature (22 ± 1 °C). Animals were purchased from the laboratory animal facilities of Anhui Medical University. All electrophysiological and behavioral experiments were conducted during the light cycle. In this study, all animal experimental procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Management Office of Laboratory Animals of Anhui Medical University and complied with all relevant ethical guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care Unit Committee of Anhui Medical University, with project number LLSC20190763.

Rhythmic Activity Measurement

Two- to 3-month-old male mice were single-housed in cages equipped with running wheels and with food and water ad libitum under the T24 and/or T7 light cycle. The cages were placed in separate lucifugal boxes with ventilation, and the ambient light intensity of the cages was 1382 lux (Opple LED lamps, China). The number of wheel revolutions was counted per second by a custom-made device. The total activity and period lengths were calculated as the total number of wheel revolutions in 2-min bins. Wheel-running data were analyzed using a custom-written program running in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA), and period lengths were calculated using ClockLab (Actimetrics, IL).

Morris Water Maze

A tank 1.2 m in diameter filled with water was made opaque using white, nontoxic ink and was maintained at 24 ± 1 °C. The pool was divided into four equal quadrants (northeast [NE], northwest [NW], southwest [SW], and southeast [SE]), with a differently shaped marker placed at the center of each quadrant, and the pool was surrounded by black curtains. The environment was kept quiet during the test. A computer with a camera and MWM software was used to record the tracking information. The animals were brought to the testing room 1 h before testing. On the first day, they were trained using a visible platform (6 × 6 cm). If a mouse did not find the platform within 90 s, it was guided to the platform and was allowed to remain on the platform for 15 s. The platform was placed in the SW quadrant during training trials with the mice starting randomly in the NE, NW, SW, and SE quadrants. Mice received four trials per day for 4 consecutive days with 20 min intertrial intervals. The total training period was 4 days and was followed by the probe test on the fifth day. For probe trials, the platform was hidden, and each mouse was allowed to swim for 90 s and was started in the NE quadrant. The escape latency, distance traveled, time spent in the target quadrant, time required to find the platform, and total distance traveled were automatically recorded for subsequent analysis.

Western Blotting

All tissue was extracted after the behavioral tests. The hippocampus was dissected out and immediately homogenized at 4 °C using a plastic homogenizer after the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane. BCA protein quantification kit (Servicebio, G2026, Wuhan, China) was used to detect the protein content. Tissues were stored in a −80 °C freezer until use. The frozen hippocampal tissues were subsequently lysed in RIPA lysis buffer and separated by 10% SDS–PAGE. After the proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes at 240 mA for 2 h, the membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk dilution in TBST for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: GluR1 (mouse, 1:1000, 100 KDa, ab183797, Novus Biology, Novus, CA, USA); GluR2 (rabbit, 1:1000, 98 KDa, R22839, Zen-bioscience, Chengdu, China); PAC1 receptor (rabbit, 1:500, 51 KDa, abs119775, absin, Shanghai, China); NR2A (rabbit, 1:1000, 160 KDa, FNab05761, Fine Biotech, Wuhan, China); NR2B (rabbit, 1:1000, 180 KDa, AF6426, Affbiotech, Changzhou, China); p-PKA (rabbit, 1:1000, 40 KDa, AF7246,Affbiotech, Changzhou, China); p-PKC (rabbit, 1:1000, 80 KDa, AF3197, Zen-bioscience, Chengdu, China); CaMKII (rabbit, 1:2000, 45 KDa, 60 KDa, 380440, Zen-bioscience, Chengdu, China); p-ERK(rabbit, 1:1000, 43 KDa, 310065, Zen-bioscience, Chengdu, China); PKA (rabbit, 1:1000, 40 KDa, FNab06478, Fine Biotech, Wuhan, China); PKC (rabbit, 1:1000, 80 KDa, FNab10007, Fine Biotech, Wuhan, China); ERK (rabbit, 1:1000, 43 KDa, FNab02846, Fine Biotech, Wuhan, China); GAPDH (mouse, 1:2000, 37 KDa, sc-47724, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); and Lamin B1 (rabbit, 1:1000, 66 KDa, AF5161, Affinit, Jiangsu, China). After overnight incubation, the membranes were washed with TBST and incubated overnight at RT with the secondary antibodies HRP-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (1:10000, S0001) or goat antimouse IgG (1:10000, BA1050) (Boster Biological Technology, USA). Chemiluminescence detection was performed using ECL Plus Western blotting detection reagent (Sparkjade, Shanghai, China). Immunoblots were quantified using a chemiluminescence gel imaging analysis system (P&Q, Shanghai, China).

In Vivo Bilateral Hippocampal Microinjection

Stereotaxic injections were performed on male mice that were 10–14 weeks old. Mice were anesthetized with i.p. injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. The skin was incised, and the skull was cleaned using 75% ethanol. Guide cannulas were bilaterally implanted 1 mm above the CA1 regions (AP: −1.5 mm, ML: ± 1 mm, and DV: −1.5 mm) of the hippocampus according to the atlas of Paxinos and Franklin. The guide cannula was affixed using dental cement to maintain cannula patency. After surgery, mice were singly housed and allowed to recover at least 3 days before the behavioral testing began. The drug was administered 30 min before the behavioral experiment. Bilateral injections were performed using an infusion pump (RWD, R462, Shenzhen, China) at a constant rate of 2 μl/min. After injection, the cannulas were left in place for an additional minute to allow for the diffusion of the drug throughout the injection site. The drugs used in the bilateral injections were pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide 1–38 (1186/100 U, Tocris Cookson, UK) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide 6–38 (3236/100 U, Tocris Cookson, UK). All drugs were dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline just before the experiments and were injected into the hippocampal CA1 regions at 1 μl/mouse (0.5 μl per side). Control animals received sterile 0.9% saline. The drugs used in the electrophysiology were 100 nmol PACAP1-38 (1186/100 U, Tocris Cookson, UK), a PAC1 receptor agonist which was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline, and 250 nmol PACAP6-38 (3236/100 U, Tocris Cookson, UK), a selective PAC1 receptor and VPAC2 receptor (Heppner et al., 2019) antagonist which was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline. Interestingly, in certain cells/tissues, PACAP6-38 exerts similar actions to PACAP1-38, behaving as an agonist (Reglodi et al., 2008).

Electrophysiology

Slice Preparation

We prepared hippocampus-containing acute slices from C57BL6/J mice (5–9 weeks old). For acute hippocampal slices, mice were anesthetized using isoflurane. The brains were removed and placed in ice-cold slice solution containing (in mM) 92 NMDG, 1.2 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 30 NaHCO3, 25 D-glucose, 20 HEPES, 5 L-ascarbate, 3 Na-pyruvate, 2 thiourea, 10 MgSO4, and 0.5 CaCl2 (saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2; pH 7.2 ± 0.1; 305–310 mOsm). Coronal slices (300 µm) were cut using a vibrating microtome (Leica Microsystems, VT1200S, USA) in the same NMDG solution. Slices were transferred to 36.5 °C artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing (in mM) 125 NaCl, 1.25 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 25 D-glucose (saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2; 305–310 mOsm; pH 7.4). Slices were allowed to recover for 45 min and were then placed on the stage and perfused with aCSF at 1–2 ml/min.

Whole-Cell Recording

Whole-cell patch clamp measurements were recorded with a MultiClamp 700B amplifier and stored using pClamp 10 software. For the recording of action potential (AP), patch pipettes had 3–5 MΩ resistance filled with intracellular solution (in mM): 135 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 10 HEPES, 0.1 EGTA, 5 Mg-ATP, and 0.5 Na-GTP (pH 7.2, 305-315 mOsm). AP was recorded using standard current-clamp patch-clamp electrophysiology techniques. Resting membrane potential (RMP) was recorded immediately upon seal rupture, and only cells had an RMP of at least −55 mV. For the recording of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSC), patch pipettes were filled with intracellular solution (in mM): 135 CsMeSO4, 10 CsCl, 1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 5 Mg-ATP, and 0.5 Na-GTP (pH 7.2, 305–315 mOsm). sEPSCs were recorded using standard voltage-clamp patch-clamp electrophysiology techniques. Slices were perfused in aCSF containing picrotoxin (50 μM) to block GABA receptor-mediated currents, AP-5 (2 μM) to block NMDA receptor-mediated currents, and CNQX (10 μM) to block AMPA receptor-mediated currents. Recordings were made at a holding potential of −70 mV.

Statistical Analysis

Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. The number of samples/animals (n) in each experimental condition is indicated in the corresponding figure legend. Comparisons among experimental groups were performed using Student's t test, Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test, Sidak's multiple comparisons test, and two-way ANOVA of GraphPad Prism 8.0 (San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical differences were accepted when P < 0.05.

Results

The Ultradian Light Cycle Induces Learning Deficits in Mice

Aberrant light stimulation can lead to alterations in cognitive function (LeGates et al., 2012). The light schedule of the T7 cycle provides a model to study the effect of light on spatial memory (Huang et al., 2021). To model learning deficit in mice, we housed mice primarily under a normal T24 light–dark cycle for at least 2 weeks and then changed the light condition to the T7 cycle. Compared to mice entrained under the T24 cycle, circadian periods were prolonged in mice housed under the T7 cycle (Figure 1A and B). After exposure to T24 or T7 for 3 weeks, the mice were subjected to the MWM. During both the training and test periods, mice housed under the T24 cycle exhibited normal spatial learning. In contrast, 2 weeks after being housed on the T7 cycle, the time mice spent finding the platform was significantly increased compared to when they were housed under the T24 cycle, and they displayed significant deficits in the spatial memory task during both training and testing (Figure 1C and D, data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and were assessed by two-way ANOVA (F(1,115) = 30.85, **** P < 0.0001) with Sikak's multiple comparisons test (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, n = 12–13 mice; Day 2: * P = 0.031; Day 3: ** P = 0.0029; Day 4: ** P = 0.0016).

Figure 1.

The ultradian light cycle induces learning deficits in mice. A, Wheel-running activity of mice housed under the T24/T7 cycle. B, Associated periodograms during at least 2 weeks in T24 cycle, followed by at least 3 weeks in T7 cycle. C, Representative trajectories of mice from each experimental group in the probe trial and working trial. D, Using the MWM, we observed significant deficits during learning and test trials in mice exposed to the T7 (gray, N = 12 mice) cycle versus T24-housed (blue, N = 13 mice) mice (two-way ANOVA (F(1,115) = 30.85, ****P < 0.0001) with Sikak's multiple comparisons test: *P(day2) = 0.031, **P(day3) = 0.0029, **P(day4) = 0.0016). E, Representative immunoblots showing the expression of PAC1 in the CA1 region from T24 and T7 mice (PAC1: pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, PACAP receptor subtype 1). F, Relative quantification of PAC1 expression. Significant differences in the rhythmicity of PAC1 levels were observed in mice exposed to the T7 (gray, N = 4 mice) cycle versus T24-housed (black, N = 4 mice) mice. The data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (F(1,36) = 56.60, ****P < 0.0001) with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; *P(ZT5) = 0.0218; *P(ZT9) = 0.0017; *P(ZT13) = 0.0019; *P(ZT17) = 0.0022) n = 4 mice)). ZT, Zeitgeber time.

The Ultradian Light Cycle Disrupts the Rhythmic Expression of PAC1 in the CA1 Region

PACAP is widely expressed in the central nervous system and has been implicated in circadian photoentrainment. The PACAP-PAC1 signaling pathway is also involved in learning and memory (Ciranna & Costa, 2019; Jaworski & Proctor, 2000). A previous study found that expression of PACAP and PAC1 displayed stable daily rhythms (Ajpru et al., 2002). To determine whether PAC1 exhibits daily variations under the T7 cycle, we chose six time points to obtain tissue from the hippocampus CA1 region over 24 h with a 4-h interval for each collection under both the T24 and T7 cycles. Expression of PAC1 displayed robust rhythmic expression under both the T24 and T7 cycles, but expression levels of PAC1 were significantly decreased under the T7 cycle compared to the T24 cycle (Figure 1E and F, data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (F(1,36) = 56.60, **** P < 0.0001) with Sikak's multiple comparisons test (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01; ZT5: * P = 0.0216; ZT9: ** P = 0.0017; ZT13: **P(ZT13) = 0.0019; ZT17: ** P = 0.0022; n = 4 mice), indicating that expression of PAC1 in the hippocampus is altered by the T7 cycle.

The PACAP-PAC1 Pathway is Implicated in Ultradian Light Cycle-Induced Mouse Learning Deficits

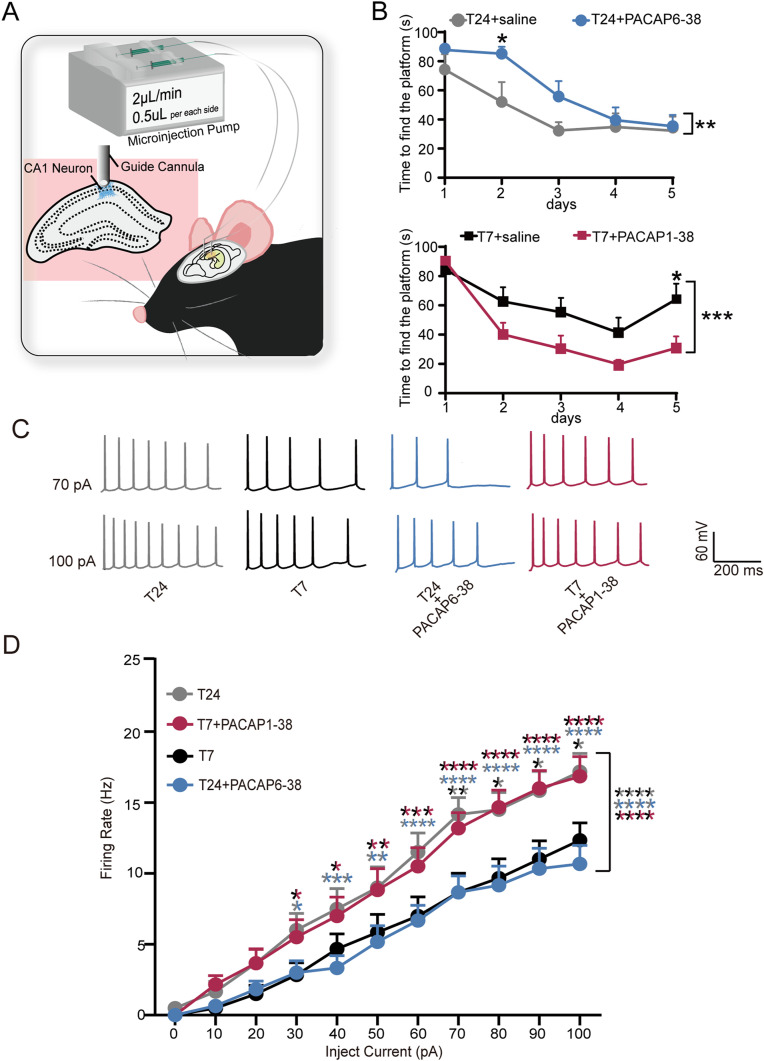

To further investigate the influence of the PACAP-PAC1 pathway on mouse learning function, we bilaterally implanted cannulas into the mouse hippocampal CA1 region (Figure 2A and Figure S1) before mice were housed under the T24 cycle or the T7 cycle. After 1 week of recovery, the mice were subjected to MWM experiments. We found that mice housed under the T24 cycle required more time to find the platform during the first 2 days of the 4-day training period after bilateral microinjection of PACAP6-38 (1 nM/1 µl/mouse), a selective PAC1 receptor antagonist that inhibits PACAP(1-27)-induced stimulation of adenylate cyclase (Maugeri et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2020), 30 min before the training period, whereas during the remaining 2 days of the training period and the subsequent test period, the mice performed similarly to the control group microinjected with saline (Figure 2B, data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (F(1,65) = 7.935, ** P = 0.0064) with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test (* P < 0.05; day 2: * P = 0.0462; n = 7–8 mice). In contrast, mice exposed to the T7 cycle required less time to find the platform during the test period than the control group after bilateral microinjection of PACAP1–38 (0.2 nM/1 µL/mouse), a PAC1 receptor agonist that shows high affinity for PAC1 receptor in membranes (Yamaguchi, 2001), 30 min before the training period (Figure 2D, data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (F(1,70) = 14.96, *** P = 0.0002) with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test; * P < 0.05; day 5: * P = 0.02, n = 8 mice), suggesting that the ultradian light cycle-induced spatial learning memory impairment is related to the PACAP-PAC1 pathway in the hippocampal CA1 region.

Figure 2.

The PACAP-PAC1 pathway is implicated in ultradian light cycle-induced learning deficits in mice. A, Representative bilateral implanted cannula in mice and bilateral microinjected drugs into the hippocampal CA1 region. B, Using the MWM, (top) deficits during learning in T24-housed mice microinjected with PACAP6-38 (blue, N = 8 mice) versus T24-housed mice microinjected with saline (gray, N = 7 mice) (two-way ANOVA (F(1,65) = 7.935, **P = .0064) are shown with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test: *P(day2) = 0.0462). (Bottom) Recover during learning in T7-housed mice microinjected with PACAP1-38 (red, N = 8 mice) versus T7-housed mice microinjected with saline (black, N = 8 mice) (two-way ANOVA (F(1,70) = 14.96, ***P = 0.0002) with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test: *P(day5) = 0.02) (PACAP6-38: antagonist of PAC1 receptor; PACAP1-38: agonist of PAC1 receptor). C, Representative current steps of changing amplitude applied during whole-cell recordings from CA1 pyramidal cells in the presence of T24 (gray), T7 (black), T24 + PACAP6-38 (blue), and T7 + PACAP1-38 (red) (PACAP1-38: PAC1 receptor agonist, PACAP6-38: PAC1 receptor antagonist). Horizontal bars represent 200 ms, and vertical bars represent 60 mV. D, Action potential firing rate of CA1 pyramidal neurons (n = 12 cells; N = 4 mice). Compared to T24-housed (gray) mice, the frequency was decreased in the cells of T7-housed (black) mouse brain slices (two-way ANOVA (F(1,242) = 50.06, ****P < 0.0001) and Sidak's multiple comparisons test: **P(70pA) = 0.0075; *P(80pA) = 0.0299; *P(90pA) = 0.0299; *P(100pA) = 0.0299), and the cells were puffed with PACAP6-38 in the T24 mouse (blue) brain slices (two-way ANOVA (F(1,121) = 166.6, ****P < 0.0001) and Sidak's multiple comparisons test. *P(30pA) = 0.0298; ***P(40pA) = 0.0005; **P(50pA) = 0.0017; ****P(60pA) < 0.0001; ****P(70pA) < 0.0001; ****P(80pA) < 0.0001; ****P(90pA) < 0.0001; ****P(100pA) < 0.0001). The frequency increased in the cells puffed with PACAP1-38 in T7 (red) mouse brain slices(two-way ANOVA (F(1,121) = 165.8, ****P < 0.0001 and Sidak's multiple comparisons test * P(30pA) = 0.0132; *P(40pA) = 0.0474; **P(50pA) = 0.0032; ***P(60pA) = 0.0003; ****P(70pA) < 0.0001; ****P(80pA) < 0.0001; ****P(90pA) < 0.0001; ****P(100pA) < 0.0001).Compared to T24-housed (gray) mice, T7 + PACAP1-38 (red) has no significant difference (two-way ANOVA and Sidak's multiple comparisons test; P > 0.05). Compared to T7-housed (gray) mice, T24 + PACAP6-38 (blue) has no significant difference (two-way ANOVA and Sidak's multiple comparisons test; P > 0.05).

The PAC1 receptor is a G-protein coupled receptor that can activate the AC/cAMP/PKA and IP3/PKC signaling pathways and internalization/endosome MEK/ERK signaling (May et al., 2014). In addition, PAC1 can mediate the AC/cAMP/PKA pathway coupling with the Ca2+/CaM/CaM kinase Ⅱ cascades in the modulation of glutamate signaling, and PACAP can increase the amplitude of the L-type calcium current by activating the PKA and PKC signaling pathways (Chik et al. 1996; Lin et al., 2018). To investigate whether the rhythmic expression of PAC1 receptor under the T7 cycle altered these intracellular signaling pathways, we euthanized mice at 4-h intervals and assessed the expression of p-PKA, p-PKC, p-ERK, and CaMKⅡ in mice housed under the T24 cycle or the T7 cycle. Expression of p-ERK in the T7 group exhibited a significant decrease at ZT13 (Figure 4, data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and were assessed by two-way ANOVA (F(1,36) = 5.079, * P < 0.0304) with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test (** P < 0.01, P(ZT13) = 0.0092) compared to the T24 group, while the rest of the rhythmic time points displayed a trend with no statistical significance. In addition, expression levels of p-PKA, p-PKC, and CaMKⅡ were not significantly different between the T24 and T7 groups. These results indicate that the ultradian light cycle does not further influence the downstream PAC1 receptor signaling pathways that were examined.

Figure 4.

The ultradian light cycle disrupts the rhythmic expression of p-PKA, P-PKC, CaMK I, and p-ERK in the CA1 region. A, C, E, G Representative immunoblots showing expression of p-PKA, p-PKC, CaMK II, and p-ERK in CA1 from T24-housed (black, N = 5 mice) and T7-housed (gray, N = 5 mice) mice (p-PKA: phospho-protein kinase A; p-PKC: phospho-proteinkinase C; CaMK Ⅱ : Ca2 + /calmodulin-dependent protein kinase, p-ERK:phospho-ERK). B, No differences in the rhythmicity of p-PKA levels were observed between groups two-way ANOVA: P > 0.05). D, No differences in the rhythmicity of p-PKC levels were observed between groups two-way ANOVA: P > 0.05). F, No differences in the rhythmicity of CaMK Ⅱ levels were observed between groups two-way ANOVA: P > 0.05). H. T24 versus T7 has a different expression of p-ERK (The data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (F(1,36) = 5.079, * P < 0.0304) with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test (** P < 0.01, P(ZT13) = 0.0092).

The PACAP-PAC1 Pathway is Involved in Modulating CA1 Region Neuron Excitability

Neurons encode and transmit information in specific frequencies and patterns, and APs and the activity of CA1 pyramidal cells in the hippocampus are associated with memory consolidation (Bevan & Wilson, 1999; Connors & Gutnick, 1990; Hainmueller & Bartos, 2018). To determine the role of the PACAP-PAC1 pathway in regulating synaptic signaling transmission in CA1 neurons under different light conditions, we obtained brain slices containing the hippocampus from mice housed under the T24 or T7 cycle. In addition, mice exposed to the T7 cycle displayed spatial memory deficits as assessed by the MWM test. We used a whole-cell patch to record the electrical activity of CA1 pyramidal cells. We investigated the effects of PACAP-PAC1 on pyramidal cell excitability by quantifying AP generation elicited by the injection of widely varying depolarizing current steps from −40 pA ∼ + 100 pA. Under control current-clamp conditions, ACSF was puffed to the surface of cells to verify that the administration route did not change the stability of cells (Figure S2A and B: baseline vs. puff statistic analyzed by two-way ANOVA; P > 0.05; n = 9 cells, N = 4 mice). The neuronal excitability of CA1 pyramidal cells under the T24 cycle and T7 cycle was assessed using the current clamp. The firing rate of APs was significantly decreased in mice kept under the T7 cycle compared to the T24 cycle when the current was injected from −40 ∼ + 100 pA (Figure 2D: T7 vs. T24 statistic analyzed by two-way ANOVA (F(1,242) = 50.06, ****P < 0.0001) and Sidak's multiple comparisons test (* P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; 70 pA: **P = 0.0075; 80 pA: * P = 0.0299; 90 pA: * P = 0.0299; 100 pA: * P = 0.0299, n = 12 cells, N = 4 mice). Interestingly, additional administration of PACAP1–38 (100 nM) (Maugeri et al., 2016) for 500 ms to neurons in the T7 group helped them recover their levels of neuronal excitability close to that in the T24 group (Figure 2D: T24 vs. T7 + PACAP1-38 statistics analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Sidak's multiple comparisons test; P > 0.05; n = 12 cells, N = 4 mice). Additionally, after CA1 pyramidal cells in brain slices from mice kept under T24 cycles were puffed with PACAP6-38 (250 nM) (Varodayan et al., 2020) for 500 ms, the firing rate of APs was significant decreased compared to T24 baseline when injected current was from −40 ∼ + 100 pA (Figure 2D T24 vs T24 + PACAP6-38 statistic analyzed by two-way ANOVA(F(1,121) = 166.6, ****P < 0.0001) and Sidak's multiple comparisons test(* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01,***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; 30pA: ** P = 0.0298; 40pA: *** P = 0.005; 50pA: ** P = 0.001760pA: **** P < 0.0001 70pA: **** P < 0.0001; 80pA: **** P < 0.0001; 90pA: **** P < 0.0001; 100pA: **** P < 0.0001, n = 12 cells, N = 4 mice), demonstrated that inhibiting the PACAP-PAC1 pathway significantly decreased neuronal excitability. However, the input resistance (Rin) (Figure S3: data are expressed as the mean ± SEM [n = 12 cells, N = 4 mice per group] by unpaired Student's t test; P > 0.05) and RMP displayed no differences among any of the groups (Figure S3: data are expressed as the mean ± SEM [n = 12 cells, N = 4 mice per group] by unpaired Student's t test; P > 0.05). These results support a direct effect of the PACAP-PAC1 pathway on regulating CA1 pyramidal cell excitability in a light-induced memory deficit model.

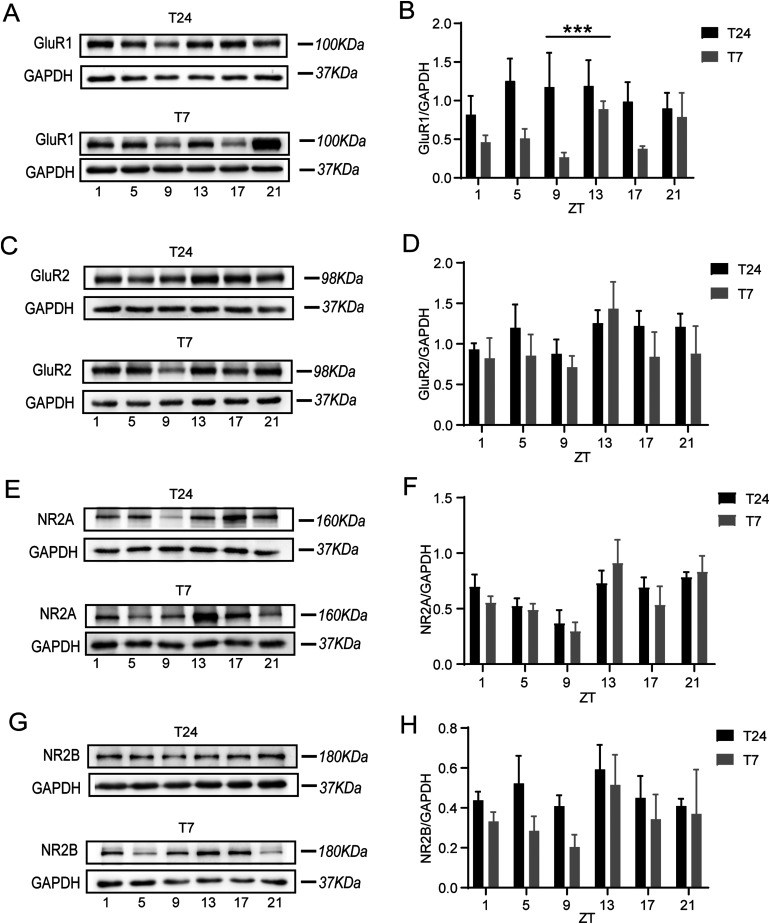

The Ultradian Light Cycle Disrupts the Rhythmic Expression of AMPA Receptors and NMDA Receptors in the CA1 Region

Excitatory glutamate synaptic signaling plays a crucial role in regulating spatial memory (Bannerman et al., 2014; Frye et al., 2021); however, the underlying mechanisms mediated by AMPARs and NMDARs in response to ultradian light-induced memory loss have not been elucidated. To determine whether there were variations in the expression of GluR1, GluR2, NR2A, and NR2B, we chose six time points (every 4 h) to obtain the mouse tissue of the hippocampal CA1 region during a 24-h interval for mice under both the T24 and T7 cycles. Compared to the T24 cycle, expression of GluR1 was decreased in the T7 cycle (Figure 3A and B, data are expressed as the data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA; F(1,36) = 13.15, *** P < 0.0009). However, we observed no expression variations in GluR2, NR2A, or NR2B protein expression in brain tissue obtained from mice housed under these two light cycles (Figure 3C–F, data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and were examined by two-way ANOVA; P > 0.05, n = 4), supporting that changes in the light environment influence expression of the glutamate receptor.

Figure 3.

The ultradian light cycle disrupts the rhythmic expression of AMPA receptors and NMDA receptors in the CA1 region. A, C, E, G, Representative immunoblots showing expression of GluR1, GluR2, NR2A, and NR2B in CA1 from T24-housed (black, N = 4) and T7-housed (gray, N = 4) mice (GluR1: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor subunit 1; GluR2: AMPA receptor subunit 2; NR2A: N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunits NR2A; NR2B: NMDB receptor subunits NR2B). B,T24 vs T7 has a different expression of GluR1(The data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (F(1,36) = 13.15, *** P < 0.0009). D, No differences in the rhythmicity of GluR2 levels were observed between groups two-way ANOVA: P > 0.05). F, No differences in the rhythmicity of NR2A levels were observed between groups two-way ANOVA: P > 0.05). H, No differences in the rhythmicity of NR2B levels were observed between groups two-way ANOVA: P > 0.05).

The PACAP-PAC1 Pathway Modulates AMPA Receptor-Mediated Currents in Memory Deficit-Induced Mice

To further examine whether the PACAP-PAC1 pathway also affects excitatory synaptic signaling transmission, we recorded AMPA receptor- and NMDA receptor-mediated currents of CA1 pyramidal cells in mice housed under the T24 or T7 cycle. The electrophysiology results revealed that compared to the T24 group, the frequency of AMPA receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents was significantly decreased in the T7 group (Figure 5A and B, data are expressed as the mean ± SEM [n = 11 cells, N = 4 mice per group] as assessed by unpaired Student's t test [* P < 0.05; T24 vs. T7: * P = 0.0321] and paired Student's t test [T24 vs. T24 + PACAP 6-38 * P = 0.0109]), but the amplitude was no different (Figure 5C, data are expressed as the mean ± SEM [n = 11 cells, N = 4 mice per group] as assessed by unpaired Student's t test; P > 0.05). Remarkably, under normal light conditions and perfusion with PACAP6-38 (250 nM), the frequency and amplitude of AMPA receptor-mediated current exhibited no differences compared to the T7 group (Figure 5A and B, data are expressed as the mean ± SEM [n = 11 cells, N = 4 mice per group] as assessed by Student's t test; P > 0.05). These results support an important functional role for the PACAP-PAC1 pathway in the regulation of excitatory postsynaptic signaling transmission. In addition, we recorded the frequency and amplitude of NMDA receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents, and no differences were observed between the T24 and T7 cycles (Figure 5D and E; data are expressed as the mean ± SEM [n = 11 cells, N = 4 mice per group] as assessed by unpaired Student's t test; P > 0.05).

Figure 5.

The PACAP-PAC1 pathway modulates the AMPA current in memory-deficit mice. A, Representative AMPA current trace on CA1 pyramidal cells. Horizontal bars represent 1 s, and vertical bars represent 20 pA. B, A cumulative probability plot of the AMPA-EPSC interevent interval (IEI) and frequency of AMPA-EPSCs in T24 (blue), T7 (gray), and T24 + PACAP6-38 (red). Compared to T24-housed (n = 11 cells, N = 4 mice) mice, the frequency was decreased in the cells of T7-housed (n = 11 cells, N = 4 mice) mouse brain slices (unpaired Student's t test: * P = 0.0321), and the cells were puffed with PACAP6-38 in the T24 mouse brain slices (n = 11 cells, N = 4 mice) (paired Student's t test: * P = 0.0109). There was no significant change between T7-housed mice and T24 + PACAP6-38 mice (unpaired Student's t test: P > 0.05). C, There was no significant change in the amplitude of the AMPA current (unpaired Student's t test: P > 0.05). D, Representative NMDA current trace in CA1 pyramidal cells. Horizontal bars represent 1 s, and vertical bars represent 20 pA. E, A cumulative probability plot of the NMDA-EPSC interevent interval (IEI) and frequency of NMDA-EPSCs at T24 (blue) and T7 (gray). Compared to T24-housed (n = 11 cells, N = 4 mice) mice, the frequency was no different in the cells of T7-housed (n = 11 cells, N = 4 mice) mouse brain slices (unpaired Student's t test: P > 0.05). F, There was no significant change in the amplitude of the NMDA current (unpaired Student's t test: P > 0.05).

Discussion

PACAP is a widely distributed neuropeptide with underlying modulatory roles in neuroprotection, stress regulation, circadian rhythm regulation, and cognition that occur through the PAC1 receptor (Georg et al., 2007; Gilmartin & Ferrara, 2021; May & Parsons, 2017). The ultradian light cycle exerts a crucial effect on learning and memory through the ipRGC-SCN pathway, with which the terminals of ipRGCs can release PACAP and glutamate when light is applied (Fernandez et al., 2018; Hannibal et al., 2002; Hannibal et al., 2004). Here, we reveal that (1) impairment of learning and memory in response to the ultradian light cycle is related to the PACAP-PAC1 pathway in the hippocampus; (2) PAC1 receptors functionally influence the excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons in the regulation of learning and memory under different light conditions; and (3) the PACAP-PAC1 pathway affects the transmission of excitatory synaptic signals of CA1 pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus primarily through AMPA receptors, affecting the ultradian light cycle and causing learning and memory impairment. Together, these results delineate the vital contribution of PACAP-PAC1 signaling in ultradian light-induced learning and memory impairment.

The ultradian light cycle-induced spatial memory impairment mouse model (Fernandez et al., 2018) allowed us to identify the PACAP-PAC1 pathway in modulating the mechanism of the effects of light on memory. In our study, the observed decrease in the rhythmic expression of the PAC1 receptor under the T7 cycle compared to the T24 cycle provides a research direction for further study. Genetic deletion of PACAP or the PAC1 receptor in mice has been used to investigate their roles in learning and memory. Mice lacking PACAP exhibit deficits in contextual fear memory (Takuma et al., 2014), as do mice lacking the PAC1 receptor, but for PAC1-deficient mice in hippocampus-dependent learning tasks, performance in the MWM task was unaffected (Otto et al., 2001; Sauvage et al., 2000). Interestingly, in our MWM experiments, mice that received the PAC1 receptor antagonist PACAP6-38 in the CA1 of the hippocampus exhibited a significantly prolonged time to find the platform when housed under the T24 cycle. Subsequently, we measured the expression of PAC1 receptor in CA1 region after this in vivo study, the results showed that the level of PAC1 in mice that received the PAC1 receptor antagonist PACAP6-38 in the CA1 was close to the mice kept under T7 cycle. Combined with the results of decreased expression rhythmic of the PAC1 receptor caused by the T7 cycle and pharmacological blocking the interaction of PACAP and PAC1 receptor, further verifying that the PACAP-PAC1 signaling pathway plays a role in learning and memory. In contrast, after administration of the PAC1 receptor agonist PACAP1-38 in the CA1 of the hippocampus in mice housed under the T7 cycle, the time to find the platform was not significantly changed compared to mice kept under the T24 cycle that underwent a sham operation. These results demonstrate that under an ultradian light cycle, the spatial memory of animals is impaired, which is related to the PACAP-PAC1 signaling pathway.

Recent evidence has shown that PACAP significantly enhances the excitability of dentate gyrus granule neurons via the PAC1 signaling pathway (Johnson et al., 2020), which is similar to our results showing that blocking the PACAP-PAC1 signaling pathway by administering PACAP6-38 to CA1 pyramidal neurons significantly depressed their excitability in mice housed under the T24 cycle. Additionally, we found that the depressed excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons in mice with the T7 cycle caused spatial memory impairment that could be reversed by perfusion with PACAP1-38, in which the excitability of neurons became close to that in mice housed under the T24 cycle. Although the expression of PAC1 receptor was lower in T7 cycle, PACAP1-38 efficiently reversed the excitability of neurons, probably through binding to VPAC receptors in CA1 regions and further influencing neuronal properties. Based on the previous literature, the most likely explanation for our results is that modulation of PACAP-PAC1 in ultradian light causes spatial memory impairment by enhancing the excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons.

Consolidation of memory depends on the regulation of the glutamate signaling pathway as shown during the process of the training experiment (Asok et al., 2019). PACAP modulates postsynaptic excitatory current via PKA or PLC/PKC, and long-term potential (LTP) is impaired in mice that lack PACAP or PAC1 (Costa et al., 2009; Macdonald et al., 2005; Otto et al., 2001). Light is an essential stimulus that modulates mood, learning, and circadian rhythms (Fernandez et al., 2018; Gibson et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2021; LeGates et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2007; Soler et al., 2018). Two neurotransmitters, PACAP and glutamate, are coreleased at the RHT terminal in response to light stimulation, and their rhythmic receptor expression is highly related to light conditions in the SCN (Hannibal et al., 2002; Hannibal et al., 2004). Our results revealed that the rhythmic expression of the PAC1 receptor, AMPAR subunit, and NMDAR subunit in the hippocampus was different under the two light conditions, which might represent the need for proper alignment between light and memory consolidation. Neurons send and receive various synaptic inputs to achieve precise regulation in the nervous system functions; the neurons excitability can drive the network's activity and dynamics (Blankenship & Feller, 2010; Penn et al., 2016; Takahashi et al., 2010). Our results showed the T7 cycle alters CA1 region neuronal excitability related to PACAP-PAC1 pathway which might influence the synaptic transmission and modulate the firing encodes of pyramidal cells. As a result, we speculate that T7 light cycle might change the state of neuronal networks in this region and modify neurons to internal or external peculiarity via the PACAP-PAC1 signaling pathway. In our subsequent electrophysiological study, we found that the frequency of AMPA-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents was significantly decreased after exposure to an ultradian T7 light cycle, and this phenomenon is consistent with the electrophysiology results when a PAC1 receptor antagonist was applied to neurons under T24 light conditions, further supporting our hypothesis. These results suggest that ultradian light-induced spatial memory impairment might be due to the blockade of glutamatergic neuronal transmission.

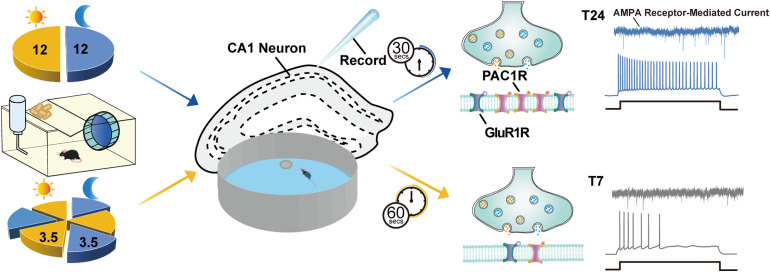

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated that ultradian light-induced spatial memory deficiency is markedly related to decreased expression of PAC1 and glutamate receptors (Figure 6). We provide evidence that ultradian light causes degressive excitability of CA1 pyramidal cells, which is related to the impairment of the PACAP-PAC1 pathway. Therefore, the PACAP/PAC1 signaling pathway is necessary and sufficient to accelerate the repair of impaired spatial memory caused by an ultradian light cycle.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram summarizing the role of the PACAP-PAC1 pathway in light-mediated spatial memory deficits. Aberrant light stimulation can lead to alterations in cognitive functions. Two different light conditions, a regular T24 cycle (12 h light: 12 h dark) and an ultradian T7 light cycle (3.5 h light: 3.5 h dark), were used in this study. In Morris water maze (MWM), a significantly prolonged time to find the platform was observed in mice exposed to the T7 cycle versus T24-housed mice. Rhythmic expressions of PAC1 receptor were decreased when housed under the T7 cycle compared to the T24 cycle. Patch clamp recording results showed that the excitability of CA1 pyramidal cells, as well as the frequency of AMPAR-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents in mice housed under the T7 cycle, were decreased, which was related to the decrease in PAC1 receptor and GluR1 expression. The PACAP-PAC1 pathway is an essential protective factor in modulating light-induced spatial memory deficits.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-asn-10.1177_17590914231169140 for Activation of the PACAP/PAC1 Signaling Pathway Accelerates the Repair of Impaired Spatial Memory Caused by an Ultradian Light Cycle by Dejiao Xu, Ying Zhang, Jun Feng, Hongyu Fu, Jiayi Li, Wei Wang, Zhen Li, Pingping Zhang, Xinqi Cheng, Liecheng Wang and Juan Cheng in ASN Neuro

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dandan Zang and GuanJun Chen of the Center for Scientific Research of Anhui Medical University for their valuable help in our experiment.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Juan Cheng and Liecheng Wang supervised and designed the work; Juan Cheng, Dejiao Xu, and Ying Zhang wrote the manuscript and revised the manuscript. Dejiao Xu and Ying Zhang complete and analyzed the patch-clamp experiment; Dejiao Xu, Jun Feng, Ying Zhang, Wei Wang, and Zhen Li completed and analyzed the western blotting experiment; Dejiao Xu, Hongyu Fu, and Jun Feng complete the Morris water maze experiment; Dejiao Xu and Jiayi Li set up the recording system and breed mice.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Our work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31800997 to Juan Cheng, 81971236, 81571293 to Liecheng Wang), the National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training (S202110366009), and the Natural Science Foundation of Universities of Anhui Province (2022AH050783 to Juan Cheng, KJ2021A0278 to Xinqi Cheng), and Postgraduate Innovation Research and Practice Program of Anhui Medical University (YJS20230035). Grants for Scientific Research of BSKY (XJ201721 to Zhen Li) of Anhui Medical University.

ORCID iD: Juan Cheng https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8116-6701

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Ago, Y., Hiramatsu, N., Ishihama, T., Hazama, K., Hayata-Takano, A., Shibasaki, Y., Shintani, N., Hashimoto, H., Kawasaki, T., Onoe, H., Chaki, S., Nakazato, A., Baba, A., Takuma, K., & Matsuda, T. (2013). The selective metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor agonist MGS0028 reverses psychomotor abnormalities and recognition memory deficits in mice lacking the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide. Behav Pharmacol, 24(1), 74–77. 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32835cf3e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajpru S., McArthur A. J., Piggins H. D., Sugden D. (2002). Identification of PAC1 receptor isoform mRNAs by real-time PCR in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 105(1--2), 29–37. 10.1016/S0169-328X(02)00387-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura A., Somogyvári-Vigh A., Miyata A., Mizuno K., Coy D. H., Kitada C. (1991). Tissue distribution of PACAP as determined by RIA: Highly abundant in the rat brain and testes. Endocrinology, 129(5), 2787–2789. 10.1210/endo-129-5-2787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asok A., Leroy F., Rayman J. B., Kandel E. R. (2019). Molecular mechanisms of the memory trace. Trends Neurosci, 42(1), 14–22. 10.1016/j.tins.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman, D. M., Sprengel, R., Sanderson, D. J., McHugh, S. B., Rawlins, J. N., Monyer, H., & Seeburg, P. H. (2014). Hippocampal synaptic plasticity, spatial memory and anxiety. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(3), 181–192. 10.1038/nrn3677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan M. D., Wilson C. J. (1999). Mechanisms underlying spontaneous oscillation and rhythmic firing in rat subthalamic neurons. J Neurosci, 19(17), 7617–7628. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07617.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship A. G., Feller M. B. (2010). Mechanisms underlying spontaneous patterned activity in developing neural circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci, 11(1), 18–29. 10.1038/nrn2759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbély E., Scheich B., Helyes Z. (2013). Neuropeptides in learning and memory. Neuropeptides, 47(6), 439–450. 10.1016/j.npep.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chik, C. L., Li, B., Ogiwara, T., Ho, A. K., & Karpinski, E. (1996). PACAP Modulates L-type Ca2+ channel currents in vascular smooth muscle cells: Involvement of PKC and PKA. FASEB J, 10(11), 1310–1317. 10.1096/fasebj.10.11.8836045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciranna L., Costa L. (2019). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide modulates hippocampal synaptic transmission and plasticity: New therapeutic suggestions for Fragile X syndrome. Front Cell Neurosci, 13, 524. 10.3389/fncel.2019.00524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors B. W., Gutnick M. J. (1990). Intrinsic firing patterns of diverse neocortical neurons. Trends Neurosci, 13(3), 99–104. 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90185-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa L., Santangelo F., Li Volsi G., Ciranna L. (2009). Modulation of AMPA receptor-mediated ion current by pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in CA1 pyramidal neurons from rat hippocampus. Hippocampus, 19(1), 99–109. 10.1002/hipo.20488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrug J., Hannibal J. (2004). Neurotransmitters co-existing with VIP or PACAP. Peptides, 25(3), 393–401. 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, D. C., Fogerson, P. M., Lazzerini Ospri, L., Thomsen, M. B., Layne, R. M., Severin, D., Zhan, J., Singer, J. H., Kirkwood, A., Zhao, H., Berson, D. M., & Hattar, S. (2018). Light affects mood and learning through distinct retina-brain pathways. Cell, 175(1), 71–84. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye, H. E., Izumi, Y., Harris, A. N., Williams, S. B., Trousdale, C. R., Sun, M. Y., Sauerbeck, A. D., Kummer, T. T., Mennerick, S., Zorumski, C. F., Nelson, E. C., Dougherty, J. D., & Morón, J. A. (2021). Sex differences in the role of CNIH3 on spatial memory and synaptic plasticity. Biol Psychiatry, 90(11), 766–780. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georg B., Hannibal J., Fahrenkrug J. (2007). Lack of the PAC1 receptor alters the circadian expression of VIP mRNA in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of mice. Brain Res, 1135(1), 52–57. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson E. M., Wang C., Tjho S., Khattar N., Kriegsfeld L. J. (2010). Experimental ‘jet lag’ inhibits adult neurogenesis and produces long-term cognitive deficits in female hamsters. PLoS One, 5(12), e15267. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin M. R., Ferrara N. C. (2021). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in learning and memory. Front Cell Neurosci, 15, 663418. 10.3389/fncel.2021.663418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainmueller T., Bartos M. (2018). Parallel emergence of stable and dynamic memory engrams in the hippocampus. Nature, 558(7709), 292–296. 10.1038/s41586-018-0191-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannibal J., Georg B., Fahrenkrug J. (2017). PAC1- and VPAC2 receptors in light regulated behavior and physiology: Studies in single and double mutant mice. PLoS One, 12(11), e0188166. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannibal J., Hindersson P., Knudsen S. M., Georg B., Fahrenkrug J. (2002). The photopigment melanopsin is exclusively present in pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-containing retinal ganglion cells of the retinohypothalamic tract. J Neurosci, 22(1), RC191. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-j0002.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannibal J., Hindersson P., Ostergaard J., et al. (2004). Melanopsin is expressed in PACAP-containing retinal ganglion cells of the human retinohypothalamic tract. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 45(11), 4202–4209. 10.1167/iovs.04-0313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannibal J., Møller M., Ottersen O. P., Fahrenkrug J. (2000). PACAP And glutamate are co-stored in the retinohypothalamic tract. J Comp Neurol, 418(2), 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmar, A. J., Arimura, A., Gozes, I., Journot, L., Laburthe, M., Pisegna, J. R., Rawlings, S. R., Robberecht, P., Said, S. I., Sreedharan, S. P., Wank, S. A., & Waschek, J. A. (1998). International union of pharmacology. XVIII. Nomenclature of receptors for vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide. Pharmacol Rev, 50(2), 265–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmar, A. J., Fahrenkrug, J., Gozes, I., Laburthe, M., May, V., Pisegna, J. R., Vaudry, D., Vaudry, H., Waschek, J. A., & Said, S. I. (2012). Pharmacology and functions of receptors for vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide: IUPHAR review 1. Br J Pharmacol, 166(1), 4–17. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01871.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner, T. J., Hennig, G. W., Nelson, M. T., May, V., & Vizzard, M. A. (2019). PACAP38-mediated bladder afferent nerve activity hyperexcitability and Ca2+ activity in urothelial cells from mice. J Mol Neurosci, 68(3), 348–356. 10.1007/s12031-018-1119-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirabayashi T., Nakamachi T., Shioda S. (2018). Discovery of PACAP and its receptors in the brain. J Headache Pain, 19(1), 28. 10.1186/s10194-018-0855-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X., Huang, P., Huang, L., Hu, Z., Liu, X., Shen, J., & Ren, C. (2021). A visual circuit related to the nucleus reuniens for the spatial-memory-promoting effects of light treatment. Neuron, 109(2), 347–362. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski D. M., Proctor M. D. (2000). Developmental regulation of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and PAC(1) receptor mRNA expression in the rat central nervous system. Brain Res Dev Brain Res, 120(1), 27–39. 10.1016/S0165-3806(99)00192-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G. C., Parsons R. L., May V., Hammack S. E. (2020). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide-induced PAC1 receptor internalization and recruitment of MEK/ERK signaling enhance excitability of dentate gyrus granule cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 318(5), C870–C878. 10.1152/ajpcell.00065.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan C., Xu H., Yue L., Tian, X. Liecheng, W., Jin, B. (2018). Plasticity of light-induced concurrent glutamatergic and GABAergic quantal events in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Biol Rhythms, 33(1), 65–75. 10.1177/0748730417754162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalló I., Kalamatianos T., Piggins H. D., Coen C. W. (2004). Ageing and the diurnal expression of mRNAs for vasoactive intestinal peptide and for the VPAC2 and PAC1 receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of male rats. J Neuroendocrinol, 16(9), 758–766. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. H., Seo S. R. (2014). Neuroprotective roles of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in neurodegenerative diseases. BMB Rep, 47(7), 369–375. 10.5483/BMBRep.2014.47.7.086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGates, T. A., Altimus, C. M., Wang, H., Lee, H. K., Yang, S., Zhao, H., Kirkwood, A., Weber, E. T., & Hattar, S. (2012). Aberrant light directly impairs mood and learning through melanopsin-expressing neurons. Nature, 491(7425), 594–598. 10.1038/nature11673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGates T. A., Fernandez D. C., Hattar S. (2014). Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nat Rev Neurosci, 15(7), 443–454. 10.1038/nrn3743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C., Bai, J., He, M., & Wong, A. O. L. (2018). Grass carp prolactin gene: Structural characterization and signal transduction for PACAP-induced prolactin promoter activity. Sci Rep, 8(1), 4655. 10.1038/s41598-018-23092-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W. P., Cao, J., Tian, M., Cui, M. H., Han, H. L., Yang, Y. X., & Xu, L. (2007). Exposure to chronic constant light impairs spatial memory and influences long-term depression in rats. Neurosci Res, 59(2), 224–230. 10.1016/j.neures.2007.06.1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, D. S., Weerapura, M., Beazely, M. A., Martin, L., Czerwinski, W., Roder, J. C., Orser, B. A., & MacDonald, J. F. (2005). Modulation of NMDA receptors by pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide in CA1 neurons requires G alpha q, protein kinase C, and activation of Src. J Neurosci, 25(49), 11374–11384. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3871-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maugeri, G., D'Amico, A. G., Reitano, R., Magro, G., Cavallaro, S., Salomone, S., & D’Agata, V. (2016). PACAP And VIP inhibit the invasiveness of glioblastoma cells exposed to hypoxia through the regulation of HIFs and EGFR expression. Front Pharmacol, 7, 139. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May, V., Clason, T. A., Buttolph, T. R., Girard, B. M., & Parsons, R. L. (2014). Calcium influx, but not intracellular calcium release, supports PACAP-mediated ERK activation in HEK PAC1 receptor cells. J Mol Neurosci, 54(3), 342–350. 10.1007/s12031-014-0300-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May V., Parsons R. L. (2017). G protein-coupled receptor endosomal signaling and regulation of neuronal excitability and stress responses: Signaling options and lessons from the PAC1 receptor. J Cell Physiol, 232(4), 698–706. 10.1002/jcp.25615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, A., Jiang, L., Dahl, R. D., Kitada, C., Kubo, K., Fujino, M., Minamino, N., & Arimura, A. (1990). Isolation of a neuropeptide corresponding to the N-terminal 27 residues of the pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide with 38 residues (PACAP38). Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 170(2), 643–648. 10.1016/0006-291X(90)92140-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. T., Kambe, Y., Kurihara, T., Nakamachi, T., Shintani, N., Hashimoto, H., & Miyata, A. (2020). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in the ventromedial hypothalamus is responsible for food intake behavior by modulating the expression of agouti-related peptide in mice. Mol Neurobiol, 57(4), 2101–2114. 10.1007/s12035-019-01864-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto, C., Kovalchuk, Y., Wolfer, D. P., Gass, P., Martin, M., Zuschratter, W., Gröne, H. J., Kellendonk, C., Tronche, F., Maldonado, R., Lipp, H. P., Konnerth, A., & Schütz, G. (2001). Impairment of mossy fiber long-term potentiation and associative learning in pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide type I receptor-deficient mice. J Neurosci, 21(15), 5520–5527. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05520.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn Y., Segal M., Moses E. (2016). Network synchronization in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 113(12), 3341–3346. 10.1073/pnas.1515105113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reglodi, D., Borzsei, R., Bagoly, T., Boronkai, A., Racz, B., Tamas, A., Kiss, P., Horvath, G., Brubel, R., Nemeth, J., Toth, G., & Helyes, Z. (2008). Agonistic behavior of PACAP6-38 on sensory nerve terminals and cytotrophoblast cells. J Mol Neurosci, 36(1--3), 270–278. 10.1007/s12031-008-9089-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage M., Brabet P., Holsboer F., Bockaert J., Steckler T. (2000). Mild deficits in mice lacking pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide receptor type 1 (PAC1) performing on memory tasks. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 84(1--2), 79–89. 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00219-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S. D., Myskiw J. C., Furini C. R., Schmidt B. E., Cavalcante L. E., Izquierdo I. (2015). PACAP modulates the consolidation and extinction of the contextual fear conditioning through NMDA receptors. Neurobiol Learn Memory, 118: 120–124. 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivers B. D., Görcs T. J., Gottschall P. E., Arimura A. (1991). Two high affinity binding sites for pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide have different tissue distributions. Endocrinology, 128(6), 3055–3065. 10.1210/endo-128-6-3055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler J. E., Robison A. J., Núñez A. A., Yan L. (2018). Light modulates hippocampal function and spatial learning in a diurnal rodent species: A study using male Nile grass rat (Arvicanthis niloticus). Hippocampus, 28(3), 189–200. 10.1002/hipo.22822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, N., Sasaki, T., Matsumoto, W., Matsuki, N., & Ikegaya, Y. (2010). Circuit topology for synchronizing neurons in spontaneously active networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 107(22), 10244–10249. 10.1073/pnas.0914594107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuma, K., Maeda, Y., Ago, Y., Ishihama, T., Takemoto, K., Nakagawa, A., Shintani, N., Hashimoto, H., Baba, A., & Matsuda, T. (2014). An enriched environment ameliorates memory impairments in PACAP-deficient mice. Behav Brain Res 272, 269–278. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varodayan, F. P., Minnig, M. A., Steinman, M. Q., Oleata, C. S., Riley, M. W., Sabino, V., & Roberto, M. (2020). PACAP regulation of central amygdala GABAergic synapses is altered by restraint stress. Neuropharmacology, 168, 107752. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Yang, W., Zhang, P., Ding, Z., Wang, L., & Cheng, J. (2022). Effects of light on the sleep-wakefulness cycle of mice mediated by intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 592, 93–98. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi N. (2001). Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide enhances glucose-evoked insulin secretion in the canine pancreas in vivo. JOP, 2(5), 306–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-asn-10.1177_17590914231169140 for Activation of the PACAP/PAC1 Signaling Pathway Accelerates the Repair of Impaired Spatial Memory Caused by an Ultradian Light Cycle by Dejiao Xu, Ying Zhang, Jun Feng, Hongyu Fu, Jiayi Li, Wei Wang, Zhen Li, Pingping Zhang, Xinqi Cheng, Liecheng Wang and Juan Cheng in ASN Neuro