Abstract

Recent research indicates that children with autism are at increased risk of maltreatment. We examined news media reports on homicide incidents involving children with autism as victims in the United States between 2000 and 2019. Of the 52 victims studied, 47 (90.4%) were male. Age of victims ranged from 2 to 20 years (mean = 10.4 ± 5.3 years). Parents and other caregivers accounted for 63.5% and 13.5% of the perpetrators, respectively. The leading injury mechanism was gunshot wounds (23.1%), followed by drowning (19.2%), and suffocation, strangulation, or asphyxiation (19.2%). The most commonly cited contributing factor (47.1%) was overwhelming stress from caring for the autistic child. These results underscore the importance of supporting services for caregivers of children with autism.

Keywords: Autism, Caregiver, Homicide, Safety, Stress, Violence

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, and restrictive and repetitive patterns. Symptoms typically appear before age 3 years and last throughout adulthood. In the United States, the reported prevalence of ASD has increased over the past two decades; in 2016, about 1 in 54 children was diagnosed with ASD increasing from 1 in 150 children in 2000 (Maenner et al., 2020). ASD is approximately four times as common among males as females and the reported prevalence is higher in non-Hispanic White children followed by non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Asian Pacific Islander children (Baio et al., 2018).

Parents of children with ASD face unique joys and challenges. These challenges often increase as the child ages and include intense financial and emotional demands (Hoefman et al., 2014). In previous studies, the most common sources of stress expressed by parents include uncontrollable child behavior and development, uncertainty in the etiology of ASD, financial costs, family relationships, uncertainty with the future, and accessing ASD-related services (Hall & Graff, 2010; Tehee et al., 2009). Parents and caregivers often report feeling misunderstood by others, including healthcare providers and family members (Celia et al., 2020). Mental, physical, and financial stress contributed most to the challenges imposed on parents giving care to children with ASD, with parents experiencing high levels of major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms (Piven & Palmer, 1999; Hoefman et al., 2014). In addition, research indicates that individuals with ASD are more likely to have parents with preexisting psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, social phobia, and personality disorders, which may further contribute to the challenges (Piven & Palmer, 1999; Daniels et al., 2008).

Studies have also documented the pivotal role that social support plays in helping parents with children with ASD to successfully manage potential stressors; including the importance of easy access to ASD-related services, quality health care for their child, and respite care (Bluth et al., 2013; Vohra et al., 2014; Whitmore, 2016). It is also important to recognize parental and family resilience as positive contributors to raising a child with ASD. In a previous study, it was found that two major necessary factors for resilience are the family’s ability to utilize resources and family members cooperating with each other for the child’s wellbeing (Bayat, 2007). Other factors include making meaning out of adversity, affirmation of strength and becoming more compassionate, and having spiritual experience and belief systems (Bayat, 2007). In some instances, having a child with ASD may strengthen family relationships (Bayat, 2007). Thus, parents who possess resilience indicators may be better able to manage stressors associated with caring for their children with ASD.

Despite the various mechanisms for navigating the challenges faced when caring for children with ASD, these challenges can take a substantial toll on caregivers and parents. As a result, children with ASD may be at increased risk of being neglected, abused, and exposed to harsh parenting compared to the general population (Chan & Lam, 2016; Sullivan & Knutson, 2000). According to the US Department of Justice, of young people with disabilities, those aged 12 to 15 years had the highest rate of violence victimizations among all age groups (Harrell, 2017). Furthermore, research indicates that the risk of premature death in children and adolescents with ASD is 2 to 10 times as high as in the general population (Gillberg et al., 2010; Mouridsen et al., 2008; Pickett et al., 2011). A Danish cohort study of children and teens followed for a mean of 35.5 years found a nearly two-fold higher mortality rate in youth with ASD compared to sex- and age-matched youth without ASD, often due to comorbid conditions such as epilepsy and other developmental conditions, injuries and infectious diseases (Bonnet-Brilhault, 2017; Mouridsen et al., 2008). There is mounting evidence that children with ASD are at substantially increased risks of self-injurious behavior and suicidality (Folch et al., 2018; Kõlves et al., 2021). However, it remains unclear if children with ASD may be at an increased risk of homicide (i.e., being deliberately and unlawfully killed by someone else).

Despite the increasing prevalence and excess risk of injury death associated with ASD, there is no injury surveillance system that reports details about the circumstances of injury incidents among children with ASD. News media has long been recognized as a useful data source for sentinel surveillance of injury incidents that are relatively rare and of public interest, such as homicide, fire-related fatalities, and drowning (Rainey and Runyan 1992). The objective of this study was to examine the characteristics of homicide incidents involving children with ASD as victims reported in the US news media from 2000–2019.

Methods

We conducted a news media search to obtain information about the circumstances of homicide incidents involving child victims with ASD. These details are typically not available in mortality surveillance systems, such as the multiple cause of death data files in the United States. We searched the Nexis Uni® database, a web-based database that features more than 15,000 news, business, and legal sources. The database was queried using the terms “autism” or “autistic” and “murder” or “kill” or “homicide” that appeared in the headline and/or lead sections of the news media. The results were limited to news articles published in the US, from January 2000 through December 2019, and in the English language. Duplicates were removed and results were screened to identify homicide victims ages ≤20 years with ASD. If multiple news media sources reported the same case, information was obtained from the most recent published article, which was assumed to have the most accurate, up-to-date information, and cross-checked against earlier published reports to obtain any details missing from the latest report to ensure complete information. Database queries and screening of results were conducted by the first author (JG), in consultation with the senior author (GL).

Data extracted for the victim included age, gender, mechanism of homicide, and year of death. In addition, the perpetrator’s age and relationship to the victim were recorded. Details of the circumstances leading up to the homicide, including stated reason for homicide and reported perpetrator psychiatric condition, were extracted. For news articles that were short and provided minimal information, a supplemental internet news media search was conducted via Google News in order to obtain additional information. Social media posts were also considered in the supplemental search only if they were from a traditional news media’s account or contained a link to the published article. Descriptive statistics were computed in Microsoft Excel.

Results

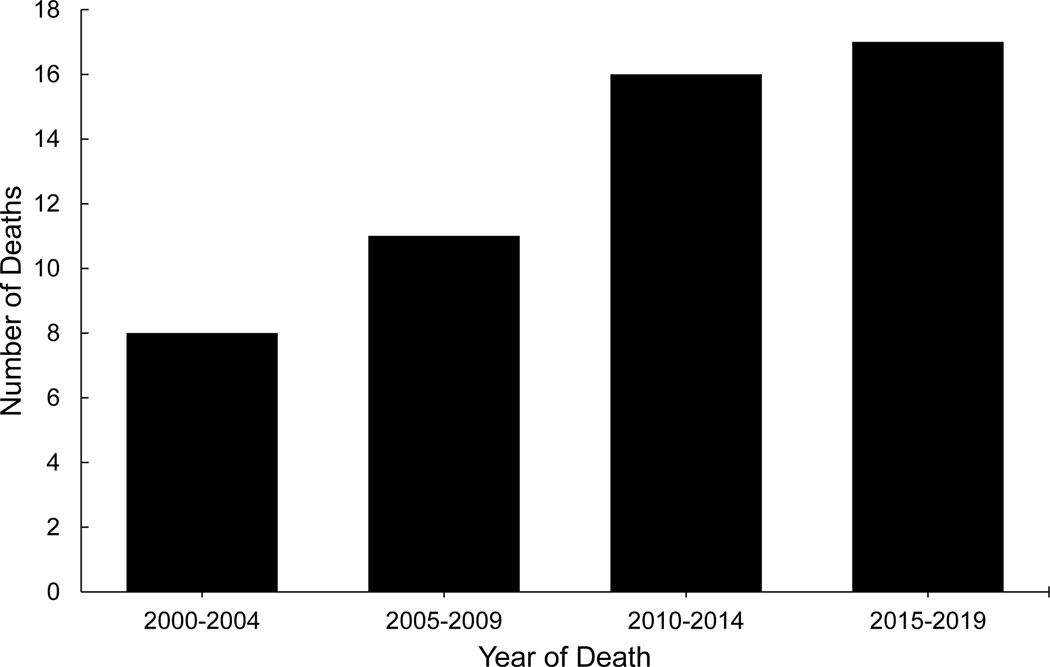

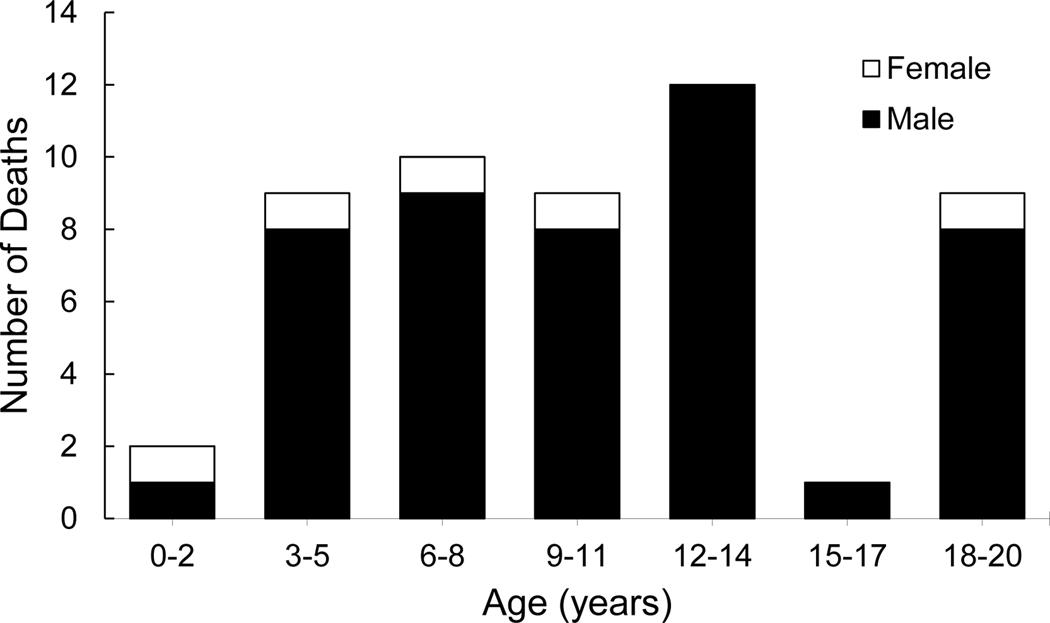

During the 20-year study period, the query yielded a total of 706 news media articles on 52 homicide incidents involving autistic child victims, including 4 homicide-suicide incidents. Of the 52 reported homicides, 33 (63.5%) occurred between 2010–2019 (Figure 1). Males accounted for 90.4% of the victims. Ages of victims at death ranged from 2 to 20 years (mean = 10.4 ± 5.3 years) (Figure 2). Information on race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status was not available from the news media reports.

Fig. 1.

Frequency Distribution of Autistic Child Homicide Victims by 5-Year Period as Reported in US News Media, January 2000 – December 2019

Fig. 2.

Frequency Distribution of Autistic Child Homicide Victims by Age and Sex as Reported in US News Media, January 2000 – December 2019

The majority (63.5%) of perpetrators were parents, with mothers and stepmothers (28.8%) most frequently identified, followed by fathers and stepfathers (25.0%), and grandparents (5.8%) (Table 1). In two cases, both the parents were identified as the perpetrators. Other perpetrators included siblings, legal guardians, caregivers, police officers, pastors, and physicians (Table 1). Data on age were available for 37 perpetrators, including 23 parents. The average age of parents who perpetrated a homicide was 37.9 ± 11.1 years. Four perpetrators (7.7%) were reported to have a diagnosis of mental illness, including three with depression and one with reactive attachment disorder.

Table 1.

Relationships of perpetrators to autistic child homicide victims by sex as reported in US news media, January 2000 ─ December 2019

| Relationship to victim | Victims | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Total n (%) | |

|

| |||

| Parent | 29 (61.7) | 4 (80.0) | 33 (63.5) |

| Mother/stepmother | 12 (25.5) | 3 (60.0) | 15 (28.9) |

| Father/stepfather | 13 (27.7) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (25.0) |

| Both mother and father | 1 (2.1) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (3.8) |

| Grandparent | 3 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.8) |

| Brother/Stepbrother | 4 (8.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.7) |

| Guardian/Caregiver a | 6 (12.8) | 1 (20.0) | 7 (13.5) |

| Law enforcement personnel | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) |

| Other unrelated b | 6 (12.8) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (11.5) |

| Total | 47 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 52 (100.0) |

Including victim’s relatives, legal guardians and caregivers.

Including pastors, physicians, or individuals who are not related to the victim.

The most common mechanism of homicide reported was gunshot wounds (23.1%), followed by drowning (19.2%), and suffocation/strangulation/asphyxiation (19.2%) (Table 2). Contributing factors were mentioned in 34 of the 52 incidents. Of these 34 incidents, overwhelming stress from caring for the child was reported in 16 (47.1%) incidents, followed by reaction to the child’s behavior reported in nine (26.5%) incidents. Common themes that emerged from the articles detailing the circumstances included variations of “[victim] is just a handful and burden”, “[perpetrator] had no life because of child”, and “not wanting a child with autism”. Reports citing the victims’ behaviors included “[victim] was punished for attempting to suffocate infant cousin”, [victim] was punished for crying”, “[victim] was restrained during a physical confrontation”, and “[victim] charged at officer with a knife”.

Table 2.

Mechanisms of injury in homicide incidents involving autistic child victims by sex as reported in US news media, January 2000 – December 2019

| Means of Homicide | Victims |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Total n (%) | |

|

| |||

| Gunshot wound | 12 (25.5) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (23.1) |

| Drowning | 8 (17.0) | 2 (40.0) | 10 (19.2) |

| Suffocation/strangled/asphyxiation | 8 (17.0) | 2 (40.0) | 10(19.2) |

| Neglecta | 5 (10.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (9.6) |

| Medication overdose | 3 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.8) |

| Blunt head trauma/traumatic brain injury | 2 (4.3) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (5.8) |

| Stabbed/slashed | 3 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.8) |

| Fire | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Physical abuse/blunt traumatic injury | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Thrown off bridge | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Unknownb | 3 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.8) |

| Total | 47 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 52 (100.0) |

Neglect includes dehydration/malnourishment, medication restriction, hypothermia, being left in hot vehicle.

Means of homicide was not disclosed or stated in the news reports.

Discussion

Our results indicate that news media reports of homicide incidents involving children with ASD in the United States have increased in recent years. This could be due to the increased prevalence and awareness of ASD since early 2000. Consistent with the existing research literature on filicide (Stöckl et al., 2017), our findings show that family members and caregivers were the most common perpetrators, with the most frequently cited contributing factor being overwhelming stress from caring for the child.

Prior studies have reported that parents of children with ASD experience substantial chronic stress due to the significant demands related to their child’s special needs (Hall & Graff, 2010; Hoefman et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2010; Tehee et al., 2009; Whitmore, 2016). Thus, it is sensible and necessary that social support (e.g., mindful parenting training and respite care) and mental health services for parents and caregivers are incorporated into intervention programs for families of children with ASD. Access to affordable, targeted intervention programs for children with ASD as well as financial assistance may help decrease parents’ stress and support parental resilience (Hall & Graff, 2010; Kogan et al., 2008; Vohra et al., 2014).

Our study found that the vast majority of children with ASD who died from homicide were male. The data provided in the news media did not provide sufficient information to explain the overrepresentation of boys among the victims. It is likely due, at least in part, to males being nearly four times as likely as females to be diagnosed with ASD (Baio et al., 2018; Perou et al., 2013). It is also possible that previously observed differences between boys and girls with ASD, e.g., differences in social communication and interaction or restricted and repetitive behaviors (Supekar & Menon, 2015;Dean et al., 2017), contributed to the overrepresentation of boys.

There are several limitations in using news media as a data source for sentinel surveillance of homicide incidents involving children with ASD. Cases reported in news media are susceptible to selection bias as journalists likely report stories based on the perceived “newsworthiness.” Consequently, the characteristics of homicide incidents involving children with ASD described in this study may have limited generalizability. While some news media reports mentioned contributing factors for the homicide incidents, the larger context of violence occurring in the household and the complex causes of child abuse, neglect, or domestic violence were not addressed. To better understand the epidemiology of violence against children with ASD, it is necessary to establish injury surveillance systems for the ASD population or enhance existing data sources, such as the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), to collect information related to autism and other developmental disorders.

Another limitation of our study is that the sensitivity of the search terms we used for querying the Nexis Uni® database is unknown. It is possible that our search may have missed some homicide incidents meeting our inclusion criteria. Finally, the accuracy of the medical conditions in child homicide victims reported in news articles has not been assessed against diagnoses in health records. Therefore, ASD cases reported in news media could be susceptible to misclassification bias.

The number of homicide incidents involving children with ASD as victims reported by the US news media has increased in the recent years, underscoring the need for better understanding of the risk of violence and injury in children with ASD. Our results indicate that the majority of perpetrators in homicide incidents involving autistic child victims are family members or caregivers who reported being overwhelmed by stress from caring for the child or having difficulty managing the victim’s behaviors. These findings support the need to expand intervention programs for children with ASD to include mental health and financial support for family members and caregivers to promote and sustain family strength and resilience.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by Grants R21 HD098522 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health; and R49 CE002096 from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The contents of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Joseph Guan, Rush Medical College, Chicago, IL.

Ashley Blanchard, Department of Emergency Medicine, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY.

Carolyn G. DiGuiseppi, Department of Epidemiology, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, CO.

Stanford Chihuri, Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY.

Guohua Li, Department of Epidemiology, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY; and Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY.

References

- Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, Maenner MJ, Daniels J, Warren Z, et al. (2018). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ, 67(6), 1–23. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat M. (2007). Evidence of resilience in families of children with autism. J Intellect Disabil Res, 51(Pt 9), 702–714. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00960.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celia T, Freysteinson W, Fredland N, & Bowyer P. (2020). Battle weary/battle ready: A phenomenological study of parents’ lived experiences caring for children with autism and their safety concerns. J Adv Nurs, 76(1), 221–233. 10.1111/jan.14213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KKS, & Lam CB (2016). Parental maltreatment of children with autism spectrum disorder: A developmental-ecological analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 32, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels JL, Forssen U, Hultman CM, Cnattingius S, Savitz DA, Feychting M, Sparen P. (2008). Parental psychiatric disorders associated with autism spectrum disorders in the offspring. Pediatrics, 121(5), e1357–62. 10.1542/peds.2007-2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Harwood R, & Kasari C. (2017). The art of camouflage: Gender differences in the social behaviors of girls and boys with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(6), 678–689. 10.1177/1362361316671845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch A, Cortés MJ, Salvador-Carulla L, et al. (2018). Risk factors and topographies for self-injurious behaviour in a sample of adults with intellectual developmental disorders. J Intellect Disabil Res, 62(12):1018–1029. 10.1111/jir.12487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg C, Billstedt E, Sundh V, & Gillberg IC (2010). Mortality in autism: a prospective longitudinal community-based study. J Autism Dev Disord, 40(3), 352–357. 10.1007/s10803-009-0883-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HR, & Graff JC (2010). Parenting challenges in families of children with autism: a pilot study. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs, 33(4), 187–204. 10.3109/01460862.2010.528644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell E. (2017). Crime against persons with disabilities, 2009–2015-Statistical tables. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Hoefman R, Payakachat N, van Exel J, Kuhlthau K, Kovacs E, Pyne J, et al. (2014). Caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder and parents’ quality of life: application of the CarerQol. J Autism Dev Disord, 44(8), 1933–1945. 10.1007/s10803-014-2066-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kõlves K, Fitzgerald C, Nordentoft M, Wood SJ, Erlangsen A. (2021). Assessment of suicidal behaviors among individuals with autism spectrum disorder in Denmark. JAMA Netw Open, 4(1), e2033565. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J, Washington A, Patrick M, DiRienzo M, et al. (2020). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ, 69(4), 1–12. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouridsen SE, Bronnum-Hansen H, Rich B, & Isager T. (2008). Mortality and causes of death in autism spectrum disorders: an update. Autism, 12(4), 403–414. 10.1177/1362361308091653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Palmer P. (1999). Psychiatric disorder and the broad autism phenotype: evidence from a family study of multiple-incidence autism families. Am J Psychiatry, 156(4), 557–63. 10.1176/ajp.156.4.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey DY, Runyan CW (1992). Newspapers: a source for injury surveillance? Am J Public Health, 82(5),745–6. 10.2105/ajph.82.5.745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöckl H, Dekel B, Morris-Gehring A, Charlotte Watts C, Abrahams N. (2017). Child homicide perpetrators worldwide: a systematic review. BMJ Paediatr Open, 1(1), e000112. 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U, & St Peter C. (2014). Access to services, quality of care, and family impact for children with autism, other developmental disabilities, and other mental health conditions. Autism, 18(7), 815–826. 10.1177/1362361313512902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore KE (2016). Respite Care and Stress Among Caregivers of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Integrative Review. J Pediatr Nurs, 31(6), 630–652. 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]