Abstract

Background

The characteristics of and relationship between sleep apnoea and hypoventilation in patients with muscular dystrophy (MD) remain to be fully understood.

Methods

We analysed 104 in-laboratory sleep studies of 73 patients with MD with five common types (DMD—Duchenne, Becker MD, CMD—congenital, LGMD—limb-girdle and DM—myotonic dystrophy). We used generalised estimating equations to examine differences among these types for outcomes.

Results

Patients in all five types had high risk of sleep apnoea with 53 of the 73 patients (73%) meeting the diagnostic criteria in at least one study. Patients with DM had higher risk of sleep apnoea compared with patients with LGMD (OR=5.15, 95% CI 1.47 to 18.0; p=0.003). Forty-three per cent of patients had hypoventilation with observed prevalence higher in CMD (67%), DMD (48%) and DM (44%). Hypoventilation and sleep apnoea were associated in those patients (unadjusted OR=2.75, 95% CI 1.15 to 6.60; p=0.03), but the association weakened after adjustment (OR=2.32, 95% CI 0.92 to 5.81; p=0.08). In-sleep average heart rate was about 10 beats/min higher in patients with CMD and DMD compared with patients with DM (p=0.0006 and p=0.02, respectively, adjusted for multiple testing).

Conclusion

Sleep-disordered breathing is common in patients with MD but each type has its unique features. Hypoventilation was only weakly associated with sleep apnoea; thus, high clinical suspicion is needed for diagnosing hypoventilation. Identifying the window when respiratory muscle weakness begins to cause hypoventilation is important for patients with MD; it enables early intervention with non-invasive ventilation—a therapy that should both lengthen the expected life of these patients and improve its quality.Cite Now

Keywords: sleep apnoea, respiratory muscles

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Sleep apnoea and hypoventilation are common in patients with muscular dystrophy (MD); however, the characteristics of sleep-disordered breathing among patients with the five types are less known. This study looks into five major types of MD (Duchenne MD, Becker MD, congenital MD, LGMD—limb-girdle and DM—myotonic dystrophy).

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Not all types of MD have the same degree and characteristics of sleep-disordered breathing. Importantly, hypoventilation was only weakly associated with sleep apnoea in patients with MD. Moreover, we found that patients with DM had significantly higher risk of sleep apnoea compared with patients with LGMD.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Specific attention should be paid to each type of MD. Because of the weak association between sleep apnoea and hypoventilation, high clinical suspicion is needed so that hypoventilation can be diagnosed early to allow for timely intervention with non-invasive ventilation and thus better outcome.

Introduction

Muscular dystrophy disorders are a heterogeneous group of inherited genetic diseases characterised by progressive skeletal muscle weakness including diaphragm weakness and cardiomyopathy and wasting.1–4 Respiratory insufficiency and cardiomyopathy are two major causes for mortality and morbidity in those patients. Chronic respiratory insufficiency results in alveolar hypoventilation and hypercapnia,5 both are common in patients with muscular dystrophy.6–8 Early treatment of cardiomyopathy improves outcomes.

The major types of muscular dystrophy include: Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD), congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) and myotonic dystrophy (DM, Greek name ‘dystrophia myotonica’). DMD9 10 is a degenerative X linked recessive muscle disease often caused by out-of-frame mutations in the DMD gene resulting in a complete loss of the functional dystrophin protein. BMD,11 also due to a defective DMD gene resulting in a partial loss of dystrophin function, presents a milder clinical spectrum compared with DMD. LGMDs12 13 are a heterogeneous group of diseases caused often by mutations (repeat expansions) in genes coding for proteins involving muscle structure formation, functions, and/or repair. DM14 is characterised by progressive muscle weakness, wasting and complex extramuscular manifestations including those in the cardiac and central nervous systems; its two principal subtypes are caused by mutations in two different genes: the DMPK gene for DM1 and the CNBP gene for DM2. CMD15 16 refers to a heterogeneous group of often severe muscular dystrophies that become apparent at or near birth.

Sleep-disordered breathing (sleep apnoea and hypoventilation) is common in patients with muscular dystrophy.17–22 Sleep apnoea occurs when normal breathing during sleep is interrupted.23 Sleep-related hypoventilation refers to breathing that is too slow or shallow during sleep resulting in impaired gas exchange as evidenced by an increase in partial arterial carbon dioxide (CO2) pressure.24 Possible differences in characteristics of sleep-disordered breathing among patients with the five major types are less well understood. Moreover, little is known about the relationship between sleep apnoea and hypoventilation in those patients. In this report, we analysed baseline and sleep variables obtained from 104 in-laboratory polysomnography (PSG) studies on 73 patients diagnosed with one of the five major types of muscular dystrophy. Our goals were: (1) to compare average values of selected clinical variables among muscular dystrophy types; (2) to examine the association of hypoventilation and sleep apnoea with clinical variables and types; and (3) to characterise the association between hypoventilation and sleep apnoea in these patients.

Methods

Subjects and study protocol

A retrospective in-laboratory PSG data review was conducted for studies carried out between January 2004 and December 2021 in an American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM)-accredited sleep laboratory at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) on patients with a diagnosis of muscular dystrophy.

In-laboratory PSG study

Routine level 1 in-laboratory PSG studies were carried out at UNC-CH hospitals. Each in-laboratory PSG included at least six channel electroencephalograms, two electro-oculograms, submental and bilateral tibialis surface electromyograms and an ECG. Additional recordings included airflow from nasal pressure and nasal/oral thermocouple, chest and abdominal movement via respiratory impedance plethysmography belts, end-tidal CO2 via a BCI capnograph sampled through a nasal cannula and arterial blood oxygen via a finger probe. Transcutaneous CO2 was used when end-tidal CO2 measurement was not feasible in selected patient groups such as the very young. Time-locked digital video was recorded with the PSG. The multichannel polysomnogram was recorded digitally and stored using a Stellate Systems polygraph, Grass Systems polygraph, and Natus polygraph between 2004 and 2012, between 2013 and 2018, and 2019 and 2021, respectively.

Studies before 2007 were scored using the guidelines from the Sleep Disorders Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association.25 Studies from September 2007 until June 2016 were scored with the 2007 guidelines from the AASM scoring manuals. Subsequent studies were scored with the 2016 guidelines.26 For all three periods, respiratory events were required to be a minimum of two breaths in duration. Hypopnoeas were required to be associated with at least 3% desaturation or arousal or 4% desaturation if the patient was on certain insurance such as Medicare. Diagnoses of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and hypoventilation were based on the criteria by International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3.27 Briefly, mild, moderate and severe sleep apnoea were defined based on the apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI) but, by convention, with different ranges depending on the patient’s age at PSG.28 29 For those younger than 13 years old, mild, moderate and severe were defined, respectively, by the following ranges: 1.5≤AHI<5, 5≤AHI<10 and AHI ≥10; for those at or above 18 years old, the corresponding ranges were: 5≤AHI<15, 15≤AHI<30 and AHI ≥30. For teenagers between the ages of 13 and 18 years, criteria were chosen at the discretion of the reading physician. Hypoventilation was also defined differently depending on the patient’s age. For those under the age of 18 years, hypoventilation was defined as having greater than 25% of time in sleep spent with partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) or surrogate measurements >50 mm Hg and a more than 10 mm Hg increase in pCO2 in sleep in comparison with awake. For those 18 years and older, hypoventilation required having greater than 10 min with pCO2 or surrogate measurements >55 mm Hg.8 Each sleep study was initially scored by an AASM board-certified sleep technologist and finalised by an AASM-certified physician. Paediatric studies were all scored by AASM board-certified sleep physicians specialised in children. Additional information can be found in the online supplemental materials.

bmjresp-2022-001506supp001.pdf (359.2KB, pdf)

Data

We included 96 diagnostic PSG studies and 8 split-night sleep studies. For a split-night study, we used data only from the diagnostic portion of the study.

We extracted patient details from electronic medical records including data on arterial blood gases (ABGs), maximal inspiratory/expiratory pressure (MIP/MEP) as measures of respiratory muscle strength, echocardiogram, Epworth Sleepiness Scale score, beta-blocker prescription, whether the patients were on ventilator at the time of study, status of tracheostomy and other relevant information (online supplemental table 1). For inclusion, these variables had to be measured within ±6 months of the sleep study. Specifically, we looked at the date of the sleep study and then at the closest clinical record before or after that date within 6 months.

From the sleep study records, we extracted the basic variables: sex, age (years), weight (kg), height (cm), body mass index (BMI) and muscular dystrophy type, as well as PSG-specific variables. These included baseline variables: oxygen saturation (%), end-tidal CO2 (mm Hg), heart rate (beats/min) and respiratory rate (breaths/min), as well as variables measured during sleep: average and peak heart rate, average and peak end-tidal CO2 and overall AHI. Some PSG studies did not record all these variables, so our data have sporadic missing values.

Statistical analysis

We computed the age-adjusted and gender-adjusted BMI z-scores using weight (kg) and height (cm) according to the method proposed by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.30 We then categorised these z-scores into three groups: z-score <−2, –2≤ z-score ≤2 and z-score >2. For some statistical analyses, we transformed continuous variables like age (by the base-2 logarithm) to improve model fit. Using the criteria delineated earlier, we also created binary (present or absent) variables for hypoventilation and sleep apnoea.

We used generalised estimating equations (GEE) with an exchangeable correlation structure31 when examining associations. Model specification differed somewhat for different response variables. For binary responses, such as apnoea or hypoventilation, our GEE models used a binomial distribution with the logistic link function; for continuous responses, such as heart rate, our GEE models used a normal distribution with the identity link function.

Although we have a reasonably large collection of patients with muscular dystrophy with PSG data, our sample, containing approximately 100 PSG studies, supports only small numbers of predictors in individual statistical models and limits statistical power. Consequently, we examined associations between response variable and individual predictor variables including adjustment for a few selected covariates. In general, we report p values without accounting for multiple testing although we employ the Tukey-Kramer procedure32 for pairwise comparisons among types. For model fitting, we used PROC GENMOD in SAS (V.9.4) (details in online supplemental materials).

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public had any involvement with planning, conducting or reporting this research.

Results

We identified 104 PSG studies from 73 unique patients with confirmed diagnosis of one of the five major types of muscular dystrophy (table 1). The most frequently represented among the major types were DMD (37% of patients) and DM (33% of patients); BMD, CMD and LGMD made up approximately 7%, 10% and 14% of patients, respectively. Of the 73 patients, 57 (78%) contributed one study, 7 (10%) had two studies, 7 (10%) had three studies and 1 (1%) had four studies. One patient (1%) with congenital DM had eight studies (online supplemental table 2). At least one patient of each type had more than one study. The patient who had eight studies was diagnosed with congenital DM type 1. Of the 31 consecutive pairs of studies from patients with multiple studies, their separation in time ranged from 0 to 10 years, with 17 (55%) within 2 years of the previous study. The patients’ pulmonologists or neurologists ordered all PSGs. All patients with DMD and BMD were male, consistent with these types being X linked recessive diseases. All patients with CMD except one were also male. Approximately half of the patients with LGMD and the DM were male.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical data for the 73 patients with muscular dystrophy from 104 PSG studies

| Variables | All types | BMD | CMD | DM | DMD | LGMD |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Total patients | 73 (100) | 5 (100) | 7 (100) | 24 (100) | 27 (100) | 10 (100) |

| Male | 55 (75) | 5 (100) | 6 (86) | 10 (42) | 27 (100) | 7 (70) |

| Female | 18 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 14 (58) | 0 (0) | 3 (30) |

| Vital status as of January 2023* | ||||||

| Alive | 58 (79) | 4 (80) | 5 (71) | 20 (83) | 21 (78) | 8 (80) |

| Deceased | 14 (19) | 1 (20) | 2 (29) | 3 (13) | 6 (22) | 2 (20) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Tracheostomy* | ||||||

| Yes | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 3 (13) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| No | 68 (93) | 5 (100) | 6 (86) | 21 (87) | 26 (96) | 10 (100) |

| Total studies† | 104 (100) | 7 (100) | 9 (100) | 37 (100) | 38 (100) | 13 (100) |

| Male | 76 (73) | 7 (100) | 8 (89) | 16 (43) | 38 (100) | 7 (54) |

| Female | 28 (27) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 21 (57) | 0 (0) | 6 (46) |

| Daytime hypoventilation (ABG) (pCO2 >45 mm Hg or bicarb >30 mEq/L)† |

||||||

| Present | 14 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 7 (19) | 2 (5) | 3 (23) |

| Absent | 35 (34) | 3 (43) | 3 (33) | 8 (22) | 17 (45) | 4 (31) |

| Not recorded | 55 (53) | 4 (57) | 4 (44) | 22 (59) | 19 (40) | 6 (46) |

| Maximal inspiratory pressure† | ||||||

| Normal | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Reduced (<75 cm H2O) | 27 (26) | 0 (0) | 4 (44) | 4 (11) | 14 (37) | 5 (38) |

| Not recorded | 76 (73) | 7 (100) | 4 (44) | 33 (89) | 24 (63) | 8 (62) |

| Maximal expiratory pressure† | ||||||

| Normal | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (15) |

| Reduced (<60 cm H2O) | 23 (22) | 0 (0) | 4 (44) | 3 (8) | 13 (34) | 3 (23) |

| Not recorded | 76 (73) | 7 (100) | 4 (44) | 33 (89) | 24 (63) | 8 (62) |

| Echocardiogram† | ||||||

| Normal | 59 (57) | 4 (57) | 6 (67) | 14 (38) | 24 (63) | 11 (85) |

| Reduced (<50 NL LVEF) | 8 (8) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Not recorded | 37 (36) | 2 (29) | 3 (33) | 23 (62) | 7 (18) | 2 (15) |

Clinical data were recorded within ±6 months of the corresponding PSG studies. Vital status was assessed up to January 2023. Clinical data for each patient nearest each PSG study are presented in online supplemental table 1.

*Percentages for all types use total number of patients (73) as the denominator; percentages for specific types use the number of patients in the total patients row for that specific type as the denominator. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

†Percentages for all types use total number of PSG studies (104) as the denominator; percentages for specific types use the number of PSG studies in the total studies row for that specific type as the denominator. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

ABG, arterial blood gas; BMD, Becker muscular dystrophy; CMD, congenital muscular dystrophy; DM, myotonic dystrophy; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; LGMD, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy; NL LVEF, normal left ventricular ejection fraction; pCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PSG, polysomnography.

Brief summary of the clinical variables

We sought certain both PSG and non-PSG-related clinical variables from patient medical records within ±6 months of each PSG study. These included ABGs, beta-blocker prescription, echocardiogram, MIP/MEP, vital status, tracheostomy status, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, ventilator status at PSG study, among others (table 1 and online supplemental table 1). For many subjects, some variables were not recorded during the 6-month window around the PSG. For example, MIP/MEP was recorded for 29, marked as ‘unable’ for 8 and unrecorded for 67 of 104 PSG studies; these factors were not routinely assessed by their pulmonologists for patients with DM and for the young because of small nostrils and other constraints. Among the 49 studies with ABG (pCO2) measurements, 35 (71%) had borderline to elevated levels (pCO2 ≥45 mm Hg or bicarb >30 mEq/L). Among the 27 studies with MIP measurements, 26 (96%) had reduced pressures. Similarly, among the 27 with MEP measurements, 22 (81%) had reduced pressures. Eight of the 67 studies (12%) with echocardiograms showed reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Five patients (three DM, one CMD and one DMD) had tracheostomy. Among the 73 patients, 14 (1 BMD, 2 CMD, 3 DM, 6 DMD and 2 LGMD) are known to have died, 1 has unknown vital status; the remainder are alive. Among the 14 deaths, the median and average age at death were 21 and 25 years old.

Age and BMI in the patients under study

Based on all 104 studies, patients with DMD and CMD had the youngest median ages (13 and 14 years, respectively); whereas patients with DM, LGMD and BMD had older median ages (22, 23 and 18 years, respectively) (table 2 and online supplemental table 3).

Table 2.

Summary statistics of age and BMI z-score among all PSG studies of patients with each type of muscular dystrophy

| Type | N* | Minimum | 1st quartile | Median | Average | 3rd quartile | Maximum |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| BMD | 7 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 18 | 30.1 | 54.4 | 58.5 |

| CMD | 9 | 4.4 | 11.5 | 14.2 | 13.6 | 14.3 | 19.3 |

| DM | 37 | 0.3 | 7.3 | 22 | 23.7 | 31.7 | 69.2 |

| DMD | 38 | 2.8 | 10.5 | 13.4 | 14 | 16.9 | 25.4 |

| LGMD | 13 | 9.8 | 12.8 | 23.1 | 28.5 | 34 | 68.8 |

| All types | 104 | 0.3 | 10.5 | 14.4 | 20.3 | 25.4 | 69.2 |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | |||||||

| BMD | 7 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 29 | 26.9 | 31.3 | 33.6 |

| CMD | 8 | 10.8 | 16.5 | 17.7 | 17.4 | 19.5 | 20.4 |

| DM | 37 | 13.3 | 16.1 | 19.5 | 21.7 | 24.2 | 38.4 |

| DMD | 38 | 13.8 | 16.9 | 23.6 | 24 | 27.3 | 45.2 |

| LGMD | 13 | 15.4 | 17.1 | 22.3 | 24.1 | 26.4 | 49.7 |

| All types | 103 | 10.8 | 16.8 | 21.1 | 22.9 | 27.8 | 49.7 |

| BMI z-score | |||||||

| BMD | 7 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 1.46 | 1.57 | 1.95 | 2.31 |

| CMD | 8 | −9.56 | −1.61 | −0.73 | −1.64 | −0.45 | 0.58 |

| DM | 37 | −2.09 | −0.98 | 0.58 | 0.26 | 0.99 | 2.46 |

| DMD | 38 | −6.32 | −0.53 | 1.18 | 0.63 | 1.86 | 2.82 |

| LGMD | 13 | −2.87 | −1.28 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 1.2 | 2.87 |

| All types | 103 | −9.56 | −0.62 | 0.74 | 0.33 | 1.53 | 2.87 |

*Number of PSG studies.

BMD, Becker muscular dystrophy; BMI, body mass index; CMD, congenital muscular dystrophy; DM, myotonic dystrophy; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; LGMD, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy; PSG, polysomnography.

Based on 103 studies (information on BMI was missing for one study), the median BMI z-score for patients with BMD or DMD either approached or exceeded the 90th percentile (z=1.28) in the general population (table 2). BMI z-score for patients with CMD was below the average z-score (z=0) in the general population in over 75% of the studies. Some patients showed signs of malnourishment at the time of study with BMI z-scores less than −2. Eleven of the 72 patients had at least one study with a BMI z-score greater than 2, indicative of overweight; eight of these were patients with DMD.

Sleep apnoeas and AHI in patients with muscular dystrophy

Fifty-three of the 73 patients (73%) were diagnosed with sleep apnoea (table 3). Four of the five patients with BMD exhibited severe primary OSA.

Table 3.

Number (%) of patients of each type ever diagnosed with hypoventilation and with mild, moderate or severe apnoea

| Type | Total patients | Hypoventilation | Level of sleep apnoea severity | |||

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |||

| BMD | 5 | 0 (0)* | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (80) |

| CMD | 7 | 4 (57) | 2 (29) | 4 (57) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) |

| DM | 24 | 10 (42) | 6 (25) | 11 (46) | 5 (21) | 2 (8) |

| DMD | 27 | 14 (52) | 7 (26) | 11 (41) | 7 (26) | 2 (7) |

| LGMD† | 10 | 2 (22) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Overall | 73 | 30 (42) | 20 (27) | 30 (41) | 14 (19) | 9 (12) |

Patients with multiple studies were assigned their highest observed apnoea severity level.

*Percentages use the type-specific total number of patients (column 2) as the denominator. Apnoea percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

†One of 10 patients with LGMD was missing hypoventilation status; thus, the denominator for hypoventilation was 9 for LGMD and 72 overall.

BMD, Becker muscular dystrophy; CMD, congenital muscular dystrophy; DM, myotonic dystrophy; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; LGMD, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy.

We examined differences in the prevalence of sleep apnoea among the types by fitting a logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex and three categories of BMI z-score using GEE. Although sleep apnoea prevalence tended to increase with age, the evidence was inconclusive (OR 1.03 per year, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.06; p=0.08). Neither were extremely high BMI z-scores (>2) associated with apnoea compared with scores between −2 and 2 (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.19 to 2.67; p=0.61); however, extremely low BMI z-scores were associated with lower prevalence of apnoea (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.91; p=0.04). Female patients had lower prevalence of sleep apnoea (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.08; p=0.07) compared with male patients, though not significantly. Adjusted estimates of the odds of sleep apnoea differed across muscular dystrophy types with DM exhibiting the highest odds and LGMD the lowest, but estimates were imprecise (online supplemental table 4A). In comparisons among all possible pairs of types, only the OR comparing DM with LGMD was statistically significant after adjustment for multiple testing (OR=5.15, 95% CI 1.47 to 18.0; p=0.003) (online supplemental table 4B).

We also examined differences in mean AHI among muscular dystrophy types by fitting a regression model using GEE adjusting for age, sex and category of BMI z-score. Based on this model, each 10-year age increase was associated with a slight increase in AHI (1.5 events/hour, 95% CI 0.5 to 2.4; p=0.002). Female patients had about the same AHI on average as male patients (mean difference=−1.3 events/hour, 95% CI −4.5 to 2.3; p=0.52). Although patients with extremely low BMI z-scores (<−2) tended to have lower AHI than the reference group (−2≤ z-score ≤2), the difference was not statistically significant (mean difference=−3.3 events/hour, 95% CI −7.5 to 0.5; p=0.08). For those with extremely high BMI z-scores (>2), mean AHI was similar to the reference group (mean difference=1.1 events/hour, 95% CI −5.5 to 7.7; p=0.74). Mean AHI appeared to differ among muscular dystrophy types. Patients with BMD had the highest observed mean AHI, over 10 events/hour higher than any other type, and patients with CMD and LGMD had the lowest (online supplemental table 3). The same relationship held after adjustment for these covariates, but confidence limits were broad (online supplemental table 5A). In comparisons of all possible pairs of types, only the BMD versus LGMD difference was statistically significant after correction for multiple testing (online supplemental table 5B).

Hypoventilation in patients with muscular dystrophy

Among the 104 PSG studies, 54 and 89 had recordings for average end-tidal CO2 (mean 44.3 mm Hg, range 26.4–62.0 mm Hg) and peak end-tidal CO2 (mean 51.7, range 35.2–90 mm Hg) during sleep, respectively (online supplemental table 3). Correlation between age and average CO2 or peak CO2 was small (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.13 and 0.03, respectively). Among the 72 patients with hypoventilation status, 30 (42%) were diagnosed with hypoventilation at least once. Patients with CMD were most likely to be diagnosed with hypoventilation (table 3), consistent with the finding that patients with CMD showed the highest mean end-tidal CO2 levels at baseline and during sleep (online supplemental table 3). Hypoventilation was common in the following types: 57% of CMD, 52% of DMD and 42% of DM. Patients with BMD and LGMD were the least likely to exhibit hypoventilation (table 3); in fact, none of the seven PSG studies on five patients with BMD yielded a diagnosis of hypoventilation.

We examined differences in the prevalence of hypoventilation among muscular dystrophy types by fitting a logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex and three categories of BMI z-score using GEE. The prevalence of hypoventilation was constant with age (OR 1.00 per year, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.03; p=0.86). Those with extreme BMI z-scores (<−2 or >2) had similar prevalence of hypoventilation compared with those with intermediate scores (z-score <−2: OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.06 to 2.79; p=0.35 and z-score >2: OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.97; p=0.69). Adjusted estimates of the odds of hypoventilation differed across muscular dystrophy types with CMD exhibiting the highest odds and LGMD the lowest, but estimates were imprecise (online supplemental table 6A). In comparisons among all possible pairs of types, none of the pairwise differences were statistically significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons (online supplemental table 6B).

Association of hypoventilation and sleep apnoea or AHI in patients with muscular dystrophy

We examined the relationship between sleep apnoea and hypoventilation among the 102 studies encompassing 71 patients where both were recorded with BMI available. We considered the association first without adjusting for any covariates and again after simultaneously adjusting for age, sex, three categories of BMI z-score and muscular dystrophy type by fitting logistic models using GEE. Among 68 PSG studies where the patient exhibited sleep apnoea, the patient also exhibited hypoventilation in 28 of them; whereas in the 34 PSG studies where the patient did not have sleep apnoea, only 7 had hypoventilation (GEE unadjusted OR 2.75, 95% CI 1.15 to 6.60; p=0.03). After adjustment for covariates, the association weakened slightly (adjusted OR 2.31, 95% CI 0.92 to 5.81; p=0.08).

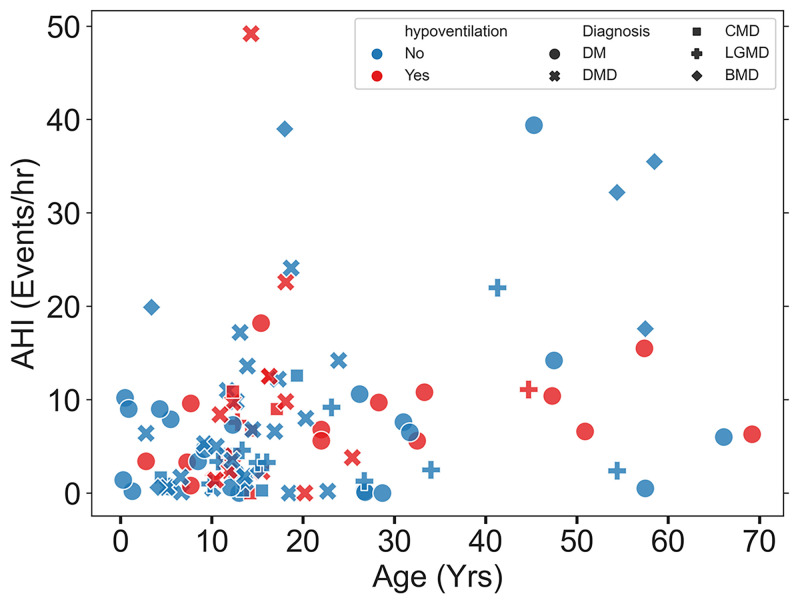

We also examined the relationship between AHI and hypoventilation by replacing sleep apnoea with AHI in the GEE logistic model. The odds of hypoventilation were estimated to increase slightly with increasing AHI, but the association was not statistically significant (adjusted OR for a 5 events/hour increase in AHI: 1.02, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.31; p=0.89). A plot of AHI against age with points coded by hypoventilation status and type failed to show a clear relationship of hypoventilation status or type to AHI (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of age versus AHI for the 104 PSG studies on patients with muscular dystrophy. Plotting symbols of different shapes indicate muscular dystrophy type (list the shapes and give the type for each). Plotting symbols in different colours indicate hypoventilation status (red symbols, present; blue symbols, absent). AHI, apnoea–hypopnoea index; BMD, Becker muscular dystrophy; CMD, congenital muscular dystrophy; DM, myotonic dystrophy; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; LGMD, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy; PSG, polysomnography.

Heart rates in patients with muscular dystrophy

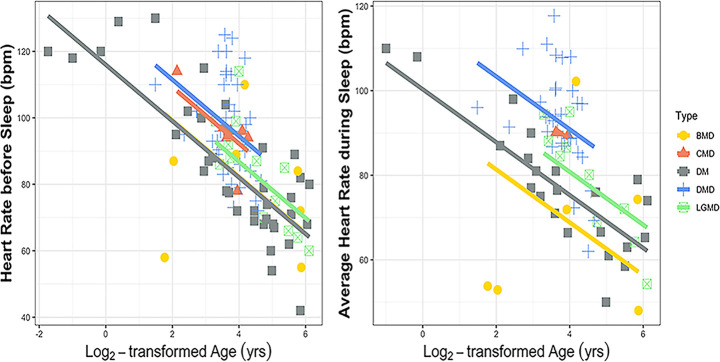

Mean baseline heart rates were 79, 96, 85, 98 and 84 beats/min (overall mean 90 beats/min) for patients with BMD, CMD, DM, DMD and LGMD, respectively (online supplemental table 3). Likewise, during sleep, the mean heart rates were 67, 90, 77, 93 and 79 beats/min (overall mean 83 beats/min), and mean peak heart rates were 113, 126, 115, 126 and 112 beats/min (overall mean 119 beats/min), respectively. Patients with DMD had significantly higher baseline heart rate and average and peak heart rates during sleep by about 10 beats/min (online supplemental table 7A), than those of patients with DM (p=0.003, p<0.0001 and p=0.02, respectively) (online supplemental table 7B and figure 2). Similarly, patients with CMD had significantly higher baseline heart rate and average and peak heart rates during sleep than those of patients with DM, again with mean differences near 10 beats/min (p=0.03, p<0.0001 and p=0.0006, respectively).

Figure 2.

Differences among muscular dystrophy types in mean heart rates after adjusting for age using regression fit by GEE methods (top: baseline heart rate; bottom: average heart rate during sleep). BMD, Becker muscular dystrophy; bpm, beats per minute; CMD, congenital muscular dystrophy; DM, myotonic dystrophy; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; GEE, generalised estimating equations; LGMD, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy.

Discussion

Our finding is consistent with sleep-disordered breathing being common in patients with muscular dystrophy.18–21 24 33 Among the five common muscular dystrophy types, sleep apnoea tended to be mild for patients with LGMD and severe for patients with BMD, an observation based on very few subjects of each type. Hypoventilation is also a major concern for patients with muscular dystrophy. Patients with CMD had the highest prevalence of hypoventilation, but it was also common in patients with DMD and DM; patients with LGMD had the lowest prevalence though differences in hypoventilation prevalence among types were not statistically significant. In a recent study of patients with DMD in their early teens,34 ~34% had hypoventilation; this proportion is somewhat lower than in our patients with DMD. Hypoventilation in patients with muscular dystrophy is usually most severe in rapid eye movement sleep.18

Unlike conditions related to skeletal muscle weakness, hypoventilation due to respiratory muscle weakness can be treated with non-invasive ventilation such as bilevel positive airway pressure. Our results support the importance of nocturnal hypoventilation monitoring for patients with muscular dystrophy as part of disease management,35 because of the high prevalence of hypoventilation and progressive nature of the diseases in patients with muscular dystrophy. Non-invasive mechanical ventilation can be a valuable modality for patients with muscular dystrophy for more favourable outcomes and better survival.8 18 24 36–38

Our analysis also revealed that sleep apnoeic events and hypoventilation events in patients with muscular dystrophy were mildly associated, though of borderline statistical significance. This finding has important clinical implications. Unlike obese hypoventilation, which is strongly associated with OSA,24 39 hypoventilation in patients with muscular dystrophy is only marginally associated with OSA. Thus, for patients with muscular dystrophy, treating OSA may not provide equal relief for hypoventilation and vice versa; both conditions may need to be managed concomitantly. Hypoventilation commonly occurs alongside sleep apnoea especially for those with obesity. Chronic hypoventilation in patients with muscular dystrophy is likely related to the underlying aetiology of the disease rather than to other conditions such as obesity, though we did see a tendency toward higher prevalence of hypoventilation among the most obese patients. Chronic weakening of respiratory muscles including diaphragm in patients with muscular dystrophy is likely the major contributor of hypoventilation in those patients.1 8 18 19 21 24 40–42 Monitoring and diagnosing early muscle weakness in those patients are important for appropriate early intervention.35 Once sleep-disordered breathing has developed, both sleep apnoeas and hypoventilation may need to be monitored and managed alongside.

Consistent with our findings, patients with CMD and DMD had high heart rate during sleep.43–45 For patients with muscular dystrophy, routine cardiology follow-up for the risk of cardiomyopathy and early pharmacological intervention may be needed especially for those with DMD and CMD.

Lastly, not all types of muscular dystrophy have the same degree and characteristics of sleep-disordered breathing or the same clinical manifestations. Specific attention should be paid to each type. For instance, patients with CMD tend to have severe muscle weakness. As a result, those patients had the lowest average BMI z-scores and the highest risk of hypoventilation compared with patients with other types. Mean AHI appeared to differ among muscular dystrophy types. DM had statistically significant higher odds of sleep apnoea compared with LGMD. Patients with BMD exhibited the severest primary OSA compared with all other types. Hypoventilation was common in the following types: 57% of CMD, 52% of DMD and 42% of DM. Patients with DMD had significantly, or nearly significantly, higher baseline heart rate and average and peak heart rates during sleep than those of patients with DM. Similarly, patients with CMD had significantly higher average and peak heart rates during sleep than those of patients with DM.

This study has several limitations. Despite having one of the largest collections of diagnostic PSG studies of patients with muscular dystrophy ever reported, our small sample size limited our ability to probe associations; consequently, CIs were wide and statistical power was restricted. BMD, CMD and LGMD had especially small samples. Our sample size was too small to probe some questions of interest such as whether the association of hypoventilation and sleep apnoea differed among the types. Further, our tertiary data collection may skew our sample of patients toward the more severe spectrum; how well the patients in our study represent the disease population is difficult to assess. Our analysis included PSG studies spanning 17 years during which different PSG technologies and scoring criteria were used. The changes in scoring criteria during the study period may have influenced scoring of hypopnoea events. We did not attempt to rescore all original studies using a single scoring criterion. Our analysis also did not consider medication use and other potential clinical confounders.

Conclusions

Sleep-disordered breathing is common among the patients with muscular dystrophy. Not all types of muscular dystrophy have the same degree and characteristics of sleep-disordered breathing or the same clinical manifestations. Specific attention should be paid to each type. Patients with DM had the highest odds of sleep apnoea, significantly higher than patients with LGMD who had the lowest odds. Patients with DMD had the highest proportion with moderate to severe OSA. Patients with CMD had the highest odds of hypoventilation followed by DMD. Hypoventilation was mildly associated with sleep apnoea after adjusting for age, sex, BMI and type, although the statistical significance of the association was borderline. Thus, CO2 retention may be an independent process from upper airway obstructive breathing. Early diagnosis of muscle weakness is critical for early intervention with non-invasive ventilation and will have a positive effect on the quality of care of a patient with muscular dystrophy and, thus, life expectancy.46

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the NIEHS Office of Scientific Computing for computing support.

Footnotes

Contributors: ZJF identified the research question. ZJF, LL and DMU were responsible for the study design and research protocol, and for drafting the manuscript. DMU, MS, LL and MA were responsible for the statistical analysis. LL, DSCY, YL and ZJF were responsible for data collection. PH, BV and ZJF were the clinicians on this project. All other authors contributed to writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript. ZJF is the guarantor for this paper, accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Programme of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ZIA ES101765).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data used in this study are stored on a secure drive at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIH). All requests for data sharing will be considered on an individual basis and data will be made available to facilitate replication of the results.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The retrospective in-laboratory PSG data review was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) (IRB #21-1984).

References

- 1.Guiraud S, Aartsma-Rus A, Vieira NM, et al. The pathogenesis and therapy of muscular dystrophies. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2015;16:281–308. 10.1146/annurev-genom-090314-025003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. BMJ 1998;317:991–5. 10.1136/bmj.317.7164.991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercuri E, Bönnemann CG, Muntoni F. Muscular dystrophies. Lancet 2019;394:2025–38. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32910-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnkrant DJ, Bushby K, Bann CM, et al. Diagnosis and management of duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:347–61. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30025-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roussos C, Koutsoukou A. Respiratory failure. European Respiratory Journal 2003;22:3s–14s. 10.1183/09031936.03.00038503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Annane D, Chevrolet JC, Chevret S, et al. Nocturnal mechanical ventilation for chronic hypoventilation in patients with neuromuscular and chest wall disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;2014:CD001941. 10.1002/14651858.CD001941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hukins CA, Hillman DR. Daytime predictors of sleep hypoventilation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:166–70. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9901057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simonds AK. Chronic hypoventilation and its management. Eur Respir Rev 2013;22:325–32. 10.1183/09059180.00003113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan D, Goemans N, Takeda S, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021;7:13. 10.1038/s41572-021-00248-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nowak KJ, Davies KE. Duchenne muscular dystrophy and dystrophin: pathogenesis and opportunities for treatment. EMBO Rep 2004;5:872–6. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bushby KMD, Gardner-Medwin D. The clinical, genetic and dystrophin characteristics of becker muscular dystrophy. J Neurol 1993;240:453. 10.1007/BF00867363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guglieri M, Straub V, Bushby K, et al. Limb-Girdle muscular dystrophies. Curr Opin Neurol 2008;21:576–84. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32830efdc2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushby K. Diagnosis and management of the limb girdle muscular dystrophies. Pract Neurol 2009;9:314–23. 10.1136/jnnp.2009.193938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner C, Hilton-Jones D. The myotonic dystrophies: diagnosis and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:358–67. 10.1136/jnnp.2008.158261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang PB, Morrison L, Iannaccone ST, et al. Evidence-Based guideline summary: evaluation, diagnosis, and management of congenital muscular dystrophy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the practice issues review panel of the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Neurology 2015;84:1369–78. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bönnemann CG, Wang CH, Quijano-Roy S, et al. Diagnostic approach to the congenital muscular dystrophies. Neuromuscular Disorders 2014;24:289–311. 10.1016/j.nmd.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner MH, Berry RB. Disturbed sleep in a patient with duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Clin Sleep Med 2008;4:173–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arens R, Muzumdar H. Sleep, sleep disordered breathing, and nocturnal hypoventilation in children with neuromuscular diseases. Paediatr Respir Rev 2010;11:24–30. 10.1016/j.prrv.2009.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourke SC, Gibson GJ. Sleep and breathing in neuromuscular disease. Eur Respir J 2002;19:1194–201. 10.1183/09031936.02.01302001a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ragette R, Mellies U, Schwake C, et al. Patterns and predictors of sleep disordered breathing in primary myopathies. Thorax 2002;57:724–8. 10.1136/thorax.57.8.724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aboussouan LS. Sleep-disordered breathing in neuromuscular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:979–89. 10.1164/rccm.201412-2224CI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus CL. Sleep-disordered breathing in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:16–30. 10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2008171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lévy P, Kohler M, McNicholas WT, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015;1:15015. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Böing S, Randerath WJ. Chronic hypoventilation syndromes and sleep-related hypoventilation. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:1273–85. 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rechtschaffen A. A manual for standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages in human subjects. Washington DC: Public Health Service, US Government Printing Office, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo C, et al. AASM scoring manual updates for 2017 (version 2.4). J Clin Sleep Med 2017;13:665–6. 10.5664/jcsm.6576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medicine AAoS . International classification of sleep disorders. Darien, IL, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu JL, Afolabi-Brown O. Updates on management of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatr Investig 2019;3:228–35. 10.1002/ped4.12164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roland PS, Rosenfeld RM, Brooks LJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline: polysomnography for sleep‐disordered breathing prior to tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngol--Head Neck Surg 2011;145:S1–15. 10.1177/0194599811409837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 2000;2000:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13–22. 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu J. Multiple comparisons. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1996. 10.1201/b15074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albdewi MA, Liistro G, El Tahry R. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with neuromuscular disease. Sleep Breath 2018;22:277–86. 10.1007/s11325-017-1538-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zambon AA, Trucco F, Laverty A, et al. Respiratory function and sleep disordered breathing in pediatric Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2022;99:e1216–26. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trucco F, Pedemonte M, Fiorillo C, et al. Detection of early nocturnal hypoventilation in neuromuscular disorders. J Int Med Res 2018;46:1153–61. 10.1177/0300060517728857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishikawa Y, Miura T, Ishikawa Y, et al. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: survival by cardio-respiratory interventions. Neuromuscular Disorders 2011;21:47–51. 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gartman EJ. Pulmonary function testing in neuromuscular and chest wall disorders. Clin Chest Med 2018;39:325–34. 10.1016/j.ccm.2018.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward S, Chatwin M, Heather S. Randomised controlled trial of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) for nocturnal hypoventilation in neuromuscular and chest wall disease patients with daytime normocapnia. Thorax 2005;60:1019–24. 10.1136/thx.2004.037424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu C, Chen MS, Yu H. The relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017;8:93168–78. 10.18632/oncotarget.21450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polat M, Sakinci O, Ersoy B, et al. Assessment of sleep-related breathing disorders in patients with duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Clin Med Res 2012;4:332–7. 10.4021/jocmr1075w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM. Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea. JAMA 2020;323:1389. 10.1001/jama.2020.3514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamashita S. Recent progress in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. J Clin Med 2021;10:1375. 10.3390/jcm10071375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beynon RP, Ray SG. Cardiac involvement in muscular dystrophies. QJM 2008;101:337–44. 10.1093/qjmed/hcm124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas TO, Morgan TM, Burnette WB, et al. Correlation of heart rate and cardiac dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Cardiol 2012;33:1175–9. 10.1007/s00246-012-0281-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilroy J, Cahalan JL, Berman R, et al. Cardiac and pulmonary complications in Duchenne’s progressive muscular dystrophy. Circulation 1963;27:484–93. 10.1161/01.cir.27.4.484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mah JK. Current and emerging treatment strategies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:1795–807. 10.2147/NDT.S93873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2022-001506supp001.pdf (359.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data used in this study are stored on a secure drive at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIH). All requests for data sharing will be considered on an individual basis and data will be made available to facilitate replication of the results.