Abstract

Objective:

The Shriners Hospitals for Children/American Burn Association Burn Outcomes Questionnaires (BOQ) are well-established, reliable, and valid outcome measures. The adolescent (BOQ11–18 years) and young adult version (YABOQ 18–30 years) have similar overlapping domains, but the scores are not comparable. This study objective was to build bridges across these forms.

Methods:

Datasets were from the Multi-Center Benchmarking Study Group. The comparable subscales from the BOQ11–18 and the YABOQ were bridged using item response theory (IRT) co-calibration. The IRT scale scores were then transformed into an expected raw score on the alternative form, from which normative scores are available. A sensitivity analysis using up to three time points, as opposed to one randomly-selected occasion, was also conducted to ensure robust results.

Results:

Data were available on 353 unique adolescents and 148 young adults. The comparable subscales were successfully bridged across forms (adolescent reliability from 0.67 to 0.85; young adult from 0.69 to 0.88). Compared to adolescents, young adults on average reported more pain and itch, less symptom and role satisfaction, and poorer work/school reintegration (Cohen’s d = 0.39 to 0.77, p < 0.05). Physical functioning, appearance, and family/parental concern were comparable across ages (d = −0.01 to 0.09, p > 0.05). Family functioning was better for young adults than adolescents (d = −0.25, p = 0.006).

Conclusions:

BOQ11–18 scores can be mapped from adolescence into young adulthood. Physical and psychosocial outcomes change across this life span. Bridges provide a highly useful approach to track changes across this part of the lifespan.

Keywords: Burn Outcome Questionnaire, Patient-reported outcomes, Linking, Adolescent survivors, Young adult survivors, Item response theory

Introduction

Burn injury has the potential to have a negative impact on the survivor’s entire life, particularly when the injury was sustained during childhood. Long-term physical issues, such as scarring, functional impairment due to contracture1, itch,2 sleep disruption,3 persistent hypermetabolism,4 and heat intolerance5 have been reported following burns. Psychological consequences related to the traumatic event or suffering through painful treatments can occur and impact long-term outcomes. In addition, post-traumatic stress disorder, dissatisfaction with perceived body image, and survivor guilt can be complicated by difficulties in social reintegration, including relating to family members, friends, strangers, and school and work lives.6,7 Sexual function and romantic relationships can be negatively influenced by both physical changes and psychosocial factors.8 The field of burn care needs to understand how current treatments impact physical and mental growth and development over childhood and into adulthood. Examination of long-term outcomes from burn injury is essential to assess and improve the quality of care provided for this population. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) are useful for this purpose. They can be used to describe a population from the patient’s perspective, as metrics to test the efficacy of treatment programs, and are a potentially powerful tool to provide personalized care.

Measurement of physical, psychological, and social outcomes following burn injury is additionally complex when examining these outcomes in children. This is because pediatric outcome measures need to account for expected changes in the growth and development of the child. Domains of interest, such as play, school or work, and sexual function are different as a person ages. Furthermore, in pre-literate and pre-verbal children, there is a need for a parent or guardian proxy to respond to the questionnaire on behalf of the child. One of the first examinations of long-term outcomes in burned children used the SF-36, a widely used generic measure.9 Using this PROM, outcomes were measured when the children were grown. In that study, while some children surviving severe burns had lingering physical disability, most had a satisfying quality of life. However, the study was limited by not only the lack of granularity attributed to the use of a non-condition specific PROM, but also by the inability to administer the instrument to the child/parent and follow the changes longitudinally throughout the child’s growth and development into adulthood.10 In order to best understand the long term effects on children in particular, it is important to track pediatric burn survivors throughout childhood, adolescence, and into adulthood. This requires PROMs where differing metrics are congruent over time.

The Shriners Hospitals for Children/American Burn Association Burn Outcome Questionnaires (BOQs) are a suite of PROMs that address multidimensional, condition-specific physical, psychological, and social health outcomes following a burn injury in children. Each form is intended for use within a specific age-based developmental stage. This allows comparisons to typically-developing peers with age-appropriate expectations. The BOQ suite includes parent-reported measures for early childhood (BOQ0–4),11 and adolescent functioning (BOQ5–18),12 adolescent functioning reported by teenagers (BOQ11–18),12 and a self-reported measure for young adults (YABOQ; appropriate for individuals 19 to 30 years of age).13 Some of the subscales do not appear on every BOQ form (e.g. Religion appears only on the YABOQ whereas aspects of physical function appear on all forms).

The scoring of the BOQs involves algorithms that incorporate data from age-matched normative samples to account for a child’s expected growth and development. The BOQs have high content relevance for burn patients, and developmental appropriateness within a form. However, one limitation within the BOQ suite is a lack of comparability across forms. All recovery trajectory studies conducted on the BOQ to date have used a within-form structure.6,13,14 Nuanced changes in clinically important domains can be lost in the transition from one survey to the next. This prevents a seamless assessment of the clinical status of the child’s burn recovery over time. A second and related limitation concerns scoring procedures. BOQ scores can be reported on either a 0–100 metric or on a T-score metric, with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. The T-score metric is frequently used in publications.6,8,13,15,16 However, the T-score is centered on different populations: the mean score of 50 for the BOQ5–18 and BOQ11–18 relates to a clinical sample; in contrast, a mean of 50 on the BOQ0–4 and the YABOQ are centered on a non-burned community sample. This significantly interferes with direct comparisons across forms.

The objective of the present study was to build bridges across the self-reported adolescent and young adult BOQ forms (i.e. BOQ11–18 and YABOQ), using the form-specific scoring conventions. It is vital for clinicians and researchers to be able to track children into adulthood as part of clinical care and longitudinal research. The physical, psychological, and social effects of a burn can linger for years and as such it is necessary to have PROMs that can bridge developmental stages. This is not a new problem: the education field in particular has developed a wide variety of statistical techniques, collectively referred to as vertical scaling, to compare scores across grades.17 Likewise, linking techniques are emerging within psychology and health services research for comparisons across different PROMS.18,19 We hypothesize that these techniques—vertical scaling and linking—will allow bridging comparable subscales across forms with sufficient item overlap. Furthermore, we hypothesize that including clinical covariates in the model would replicate previous studies and support the use of the bridges across clinical severities. This allows comparison across forms on the effect of the various clinical covariates. Comparing recovery trajectories for adolescent burn survivors into early adulthood can then be achieved.

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Multi-Center Benchmarking Study Group (MCBS).20 Data were collected at four Shriner Hospital sites between September 2001 and November 2010 for the BOQ11–18 and between March 2003 and February 2008 for the YABOQ. Children and young adults who completed at least one BOQ version were eligible for participation. For subgroup analyses, patients were included if they had a burn to any critical area (i.e. face, genitals, hands, or feet [when available]), and if the size of their burn was greater than or equal to 20% of their total body surface area (TBSA). For individuals with multiple BOQ completions, a randomly-selected set was used for the traditional bridging techniques. Then sensitivity analysis was conducted, using up to three BOQ completions, stratified by time since burn (3 months or less, over 3 months to one year, and longer than one year post-burn).

Measures

Both the BOQ11–18 and the YABOQ versions were used to create the bridges. They have two types of scores: either a 0–100 scale, or a T-score with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. Higher scores indicate better functioning. The average score for the BOQ11–18 is centered on a clinical sample from the MCBS, whereas the average score for the YABOQ is centered on a non-burned community sample of 112 young adults.

The BOQ11–18 has 12 subscales and the YABOQ includes 15 subscales. Table 1 gives the names and number of items on the two BOQ versions. For subscales appearing on both forms, the number of nearly identical items is also provided. Overlapping content across forms occasionally spanned multiple domains. Namely, Satisfaction with Symptom Relief and Satisfaction with Role on the YABOQ, when aggregated, overlapped with Satisfaction with Current Status on the BOQ11–18. Likewise, items on the YABOQ Physical Function subscale were drawn from both the Physical Function and Sports and the Transfers and Mobility subscales from the BOQ11–18. The Compliance subscale only appears on the BOQ11–18, and Social Function limited by Physical Function, Social Function limited by Appearance, Religion, and Sexual Function only appear on the YABOQ.

Table 1:

BOQ11–18 and YABOQ Subscales

| BOQ11–18 | # Overlapping Items | YABOQ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | # Items | # Items | Domain | |

| Pain | 2 | 2 | 2 | Pain |

| Itch | 2 | 2 | 2 | Itch |

| Satisfaction with Current Status | 6 | 6 | 3 | Satisfaction with Symptom Relief |

| 3 | Satisfaction with Roles | |||

| Physical Function and Sports | 6 | 5 | 5 | Physical Function |

| Transfers and Mobility | 5 | |||

| 5 | Social Function limited by Physical Function | |||

| Upper Extremity Function | 7 | 1 | 1 | Fine Motor |

| Appearance | 4 | 3 | 3 | Perceived Appearance |

| 4 | Social Function limited by Appearance | |||

| Emotional Health | 4 | 1 | 2 | Emotion |

| Family Disruption | 5 | 3 | 3 | Family Function |

| Parental Concern | 3 | 3 | 3 | Family Concern |

| School Reintegration | 3 | 3 | 3 | Work Reintegration |

| Compliance | 5 | |||

| 4 | Religion | |||

| 5 | Sexual Function | |||

Analytic Plan

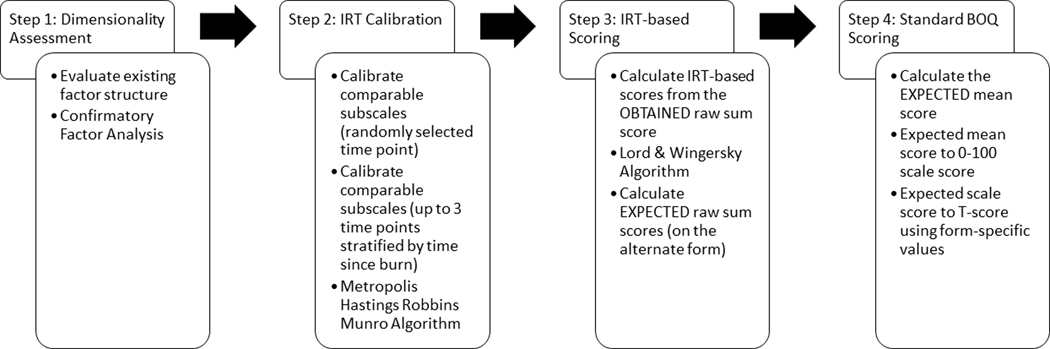

We hypothesized that comparable subscales could be bridged across BOQ forms. The score conversion process required a multi-step procedure (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

The analytic steps for this project involve evaluating the dimensionality of the BOQ forms (step 1), co-calibrating the forms using item response theory (IRT; step 2), IRT-based scoring (step 3), and BOQ algorithmic scoring (step 4).

Step 1 involved confirming the factor structure of the BOQ forms, which has been previously described,12,13 using confirmatory factor analytic models. In the event of factor structure misfit, follow-up models were estimated allowing fewer restrictions on misfitting items.

Step 2 involved co-calibrating the BOQ11–18 and YABOQ using a graded response item response theory (IRT) model. The Metropolis-Hastings Robbins Munro (MHRM) algorithm21 was used to calibrate the item parameters onto an IRT-based scale consistent with the final directionality of the scores (e.g. higher scores indicate better outcomes/fewer symptoms). Each form was treated as a separate group of individuals, responding to some unique and some overlapping items. In order to statistically identify groups, the adolescent BOQ11–18 was chosen as the reference group with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1, and items with overlapping content (allowing for minor rewording of items, e.g. from “parents” to “family”) were equated across groups. This structure is referred to as a non-equivalent anchor test (NEAT) design.17 The overlapping items composed the “anchor” which allowed score comparisons across forms. An important statistical requirement for NEAT designs is that the anchor items function equivalently across forms, which was assumed for this project.

Step 3 involved IRT-based scoring. The raw sum score from one form was converted into a comparable IRT-based score through the Lord and Wingersky algorithm.22 Then, the IRT-based score was converted into an expected sum score on the alternate form using the test characteristic curve specific to that form.

Step 4 involved standard BOQ scoring algorithms (BOQ11–18-2014–1 and YABOQ-2014–1), using the expected mean score. The mean of the raw score is converted into the form-specific 0–100 scale score and the T-score. We used the appropriate form-specific conversion values on the mean of the expected raw score to calculate expected scaled scores and T-scores.

To ensure the robustness of the conclusions, Step 2 was conducted twice: first using a randomly selected BOQ completion, and then using up to three BOQ completions per person, stratified by time since burn. This second sensitivity analysis utilized a complex IRT bifactor data structure to account for the longitudinal design and repeated items.23 Step 3 in this robustness check then used the time-weighted group distribution.

Finally, it was important to consider the effect of known covariates in assessing recovery trajectories. TBSA greater than 20% and any burns to critical areas were treated as dichotomous predictors of scores in all domains at all three time points in the longitudinal model. These predictors were not required to be equal on the BOQ11–18 and YABOQ, thus allowing comparisons on the effect of these clinical characteristics across forms.

Results

Participants

Table 2 summarizes the patient demographics. There were 353 unique adolescents and 148 young adults who completed at least one form from the BOQ suite. Age and time since burn were taken from the randomly selected occasion. Subjects were on average 15 years old with 1.5 years since burn injury on the BOQ11–18 and about 25 years old and 0.6 years since burn injury on the YABOQ. For the sensitivity analysis stratified by time since burn, 655 BOQ11–18 completions and 241 YABOQ completions were available. No survivor completed both forms at any time during their recovery.

Table 2:

Burn Survivor Demographics

| Characteristic | BOQ11–18 | YABOQ |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sample size – N | 353 | 148 |

| Age – Mean (SD) | 14.7 (2.6) | 24.8 (3.6) |

| Years Since Burn – Mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.2) | 0.6 (1.3) |

| Males – N, % | 279, 79% | 107, 72% |

| Females – N, % | 74, 21% | 41, 28% |

| Caucasian – N, % | 162, 46% | 93, 63% |

| Non-Caucasian – N, % | 191, 54% | 55, 37% |

| Critical Site Burns – N, % | 291, 82% | 91, 61% |

| TBSA >= 20% – N, % | 238, 67% | 25, 17% |

Dimensionality

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to validate the existing structures. For subscales with only two items (e.g. Pain, Itch), the factor loadings were constrained to equality for identification purposes. The subscales were largely supported; however, several differences emerged. Specifically, on the BOQ11–18, Physical Function and Sports and Transfers and Mobility exhibited a high correlation (r = 0.96), suggesting modeling as one subscale rather than two. Likewise on the YABOQ, with only one item the Fine Motor subscale was not empirically identified. Allowing this item to join a different subscale suggested it most closely aligned with Physical Function. Satisfaction with Symptom Relief and Satisfaction with Roles were also highly correlated (r = 0.80), suggesting modeling as one subscale rather than two. Collapsing Physical Function and Sports with Transfers and Mobility on the BOQ11–18 and collapsing the two satisfaction subscales on the YABOQ support the goals of this project insofar as the subscales are collapsed on the opposite form, easing the bridges between forms. Overall, these analyses broadly supported the subscale structure previously proposed for these measures in the BOQ suite.11,12,13

Creating and Using Subscale Bridges

There were 10 subscales (after collapsing subscales as specified above) with overlapping content (Table 1). However, Upper Extremity/Fine Motor and Emotional Health only contained one overlapping item. This was determined to be insufficient for bridging subscales. Collapsing Upper Extremity/Fine Motor into the Physical Function subscale was considered (as this was suggested for the YABOQ) but was determined to be suboptimal for the BOQ11–18. Although the Upper Extremity domain is clearly related to the two physical function domains (r = 0.87 with Physical Function and Sports; r = 0.90 with Transfers and Mobility), the additional items allow unique estimation of this subscale for adolescents. This left eight comparable subscales across BOQ forms: Pain, Itch, Satisfaction, Physical Function, Appearance, Family Function, Parental/Family Concern, and School/Work Reintegration.

Using the randomly selected BOQ completions, bridges were built across BOQ forms. The reliability for the IRT-based scoring varied from 0.65 to 0.86 for the BOQ11–18, and from 0.74 to 0.88 for the YABOQ. The randomly completed BOQ suggested that young adults fared worse than adolescents. However, young adult survivors were closer to the time of the burn than the adolescents (c.f. Table 2), which may be related to their recovery. Separately, we conducted a sensitivity analysis, stratifying BOQ completions by time since burn. This further allowed comparison of recovery trajectories with the BOQ bridging. For identification purposes, adolescent completions 3 to 12 months post-burn were used as the reference group onto which IRT-based scores were compared. This produced largely comparable bridges and subscale reliabilities. However, differences emerged in the time-weighted average severities across groups. Specifically, young adults reported more pain and itch, less symptom and role satisfaction, and poorer work/school reintegration. There were no differences by age for physical function, appearance, or family concern. Young adults reported better Family Function, however, than adolescents. Table 3 provides the reliabilities for both calibrations, and between group effect sizes on the time-weighted means.

Table 3:

Subscale Reliability and Between Group Differences

| Subscale | IRT-based Marginal Reliability | Time-Weighed Effect Size Between Forms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOQ11–18 Random | BOQ11–18 Three Times | YABOQ Random | YABOQ Three Times | ||

| Pain | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.97 |

| Itch | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.39 |

| Satisfaction | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.56 |

| Physical Function | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.69 | −0.01 |

| Appearance | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.09 |

| Family Function | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.72 | −0.25 |

| Parental / Family Concern | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | −0.01 |

| School / Work Reintegration | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.41 |

The item parameters were then used to create a bridge between obtained raw sum scores and mean scores to expected scores on the alternate form, which were transformed into the scores typically reported for that BOQ form. Table 4 provides an example of a bridge for the Appearance subscale. The obtained raw sum scores are given with the expected scores on the alternate form. All eight subscale bridges are available in the online supplementary material.

Table 4:

Example Score Bridge for Appearance

| Obtained Scores | Expected Scores (Random Completion) | Expected Scores (Three Time Points) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Sum | Mean | Mean | Scale 0–100 | T-Score | Mean | Scale 0–100 | T-Score |

| Observed BOQ11–18 to Expected YABOQ | |||||||

| 0 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 3.50 | −2.98 | 0.19 | 4.78 | −2.16 |

| 1 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 9.49 | 0.83 | 0.42 | 10.45 | 1.45 |

| 2 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 13.71 | 3.52 | 0.61 | 15.32 | 4.54 |

| 3 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 19.62 | 7.28 | 0.83 | 20.76 | 8.01 |

| 4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 25.09 | 10.77 | 1.04 | 26.06 | 11.38 |

| 5 | 1.25 | 1.24 | 30.92 | 14.48 | 1.26 | 31.38 | 14.77 |

| 6 | 1.50 | 1.46 | 36.46 | 18.00 | 1.46 | 36.61 | 18.09 |

| 7 | 1.75 | 1.68 | 41.94 | 21.49 | 1.67 | 41.76 | 21.38 |

| 8 | 2.00 | 1.90 | 47.43 | 24.99 | 1.88 | 46.96 | 24.68 |

| 9 | 2.25 | 2.12 | 53.03 | 28.55 | 2.09 | 52.28 | 28.07 |

| 10 | 2.50 | 2.36 | 58.91 | 32.29 | 2.31 | 57.80 | 31.58 |

| 11 | 2.75 | 2.60 | 64.92 | 36.12 | 2.54 | 63.49 | 35.21 |

| 12 | 3.00 | 2.88 | 71.91 | 40.57 | 2.79 | 69.70 | 39.16 |

| 13 | 3.25 | 3.10 | 77.52 | 44.13 | 3.02 | 75.45 | 42.82 |

| 14 | 3.50 | 3.38 | 84.45 | 48.55 | 3.28 | 82.03 | 47.01 |

| 15 | 3.75 | 3.52 | 88.11 | 50.88 | 3.46 | 86.59 | 49.91 |

| 16 | 4.00 | 3.80 | 95.01 | 55.27 | 3.72 | 92.97 | 53.97 |

| Observed YABOQ to Expected BOQ 11–18 | |||||||

| 0 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 7.24 | 29.68 | 0.37 | 9.36 | 30.44 |

| 1 | 0.33 | 0.74 | 18.45 | 33.70 | 0.80 | 19.92 | 34.23 |

| 2 | 0.67 | 1.06 | 26.49 | 36.59 | 1.12 | 28.07 | 37.15 |

| 3 | 1.00 | 1.38 | 34.48 | 39.46 | 1.43 | 35.80 | 39.93 |

| 4 | 1.33 | 1.67 | 41.66 | 42.03 | 1.72 | 42.97 | 42.50 |

| 5 | 1.67 | 1.95 | 48.74 | 44.58 | 1.99 | 49.81 | 44.96 |

| 6 | 2.00 | 2.23 | 55.63 | 47.05 | 2.26 | 56.55 | 47.38 |

| 7 | 2.33 | 2.51 | 62.63 | 49.56 | 2.53 | 63.35 | 49.82 |

| 8 | 2.67 | 2.81 | 70.36 | 52.34 | 2.82 | 70.43 | 52.36 |

| 9 | 3.00 | 3.07 | 76.78 | 54.64 | 3.08 | 76.88 | 54.68 |

| 10 | 3.33 | 3.37 | 84.30 | 57.34 | 3.35 | 83.77 | 57.15 |

| 11 | 3.67 | 3.53 | 88.21 | 58.74 | 3.53 | 88.34 | 58.79 |

| 12 | 4.00 | 3.80 | 94.99 | 61.18 | 3.77 | 94.17 | 60.88 |

Note: The observed Raw and Mean scores assume standard rescoring procedures to maintain the subscale directionality, when necessary (e.g. recoding the Appearance subscale [and others] on the BOQ11–18 to maintain better outcomes with higher scores.

Effect of Covariates on Recovery Trajectories

The final analyses for this project involved examining if or how known covariates affected the between groups bridging. As such, the three time point models were re-estimated using the MHRM algorithm to include covariates. For ease of interpretation, the covariate effects were assumed to be constant at all time points within each group but were allowed to vary between groups. The models were run three times: once considering only critical areas, once considering only TBSA, and once considering both critical areas and TBSA. The coefficients from these models and their 95% confidence intervals are shown in Table 5. Clinical covariates with confidence intervals that do not include 0.0 reflect significant predictors of the latent IRT-based scores.

Table 5:

Clinical Covariate Effects

| Domain | Model | Form | Critical Areas | TBSA >= 20% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Estimate | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Pain | Considered Alone | BOQ11–18 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.42 | −0.08 | −0.20 | 0.04 |

| YABOQ | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.08 | ||

| Considered Together | BOQ11–18 | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.74 | −0.34 | −0.56 | −0.12 | |

| YABOQ | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.10 | 0.10 | ||

| Itch | Considered Alone | BOQ11–18 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.37 | −0.14 | −0.26 | −0.02 |

| YABOQ | −0.04 | −0.12 | 0.04 | −0.18 | −0.28 | −0.08 | ||

| Considered Together | BOQ11–18 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.72 | −0.47 | −0.69 | −0.25 | |

| YABOQ | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.05 | −0.17 | −0.27 | −0.07 | ||

| Satisfaction | Considered Alone | BOQ11–18 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.63 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.16 |

| YABOQ | −0.07 | −0.19 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.15 | 0.13 | ||

| Considered Together | BOQ11–18 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 1.08 | −0.45 | −0.66 | −0.23 | |

| YABOQ | −0.06 | −0.18 | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.15 | 0.13 | ||

| Physical Function | Considered Alone | BOQ11–18 | 1.01 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.51 |

| YABOQ | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.13 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.04 | ||

| Considered Together | BOQ11–18 | 1.51 | 1.29 | 1.73 | −0.69 | −0.94 | −0.44 | |

| YABOQ | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.13 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.04 | ||

| Appearance | Considered Alone | BOQ11–18 | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.18 | −0.46 | −0.58 | −0.34 |

| YABOQ | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.14 | −0.11 | −0.27 | 0.05 | ||

| Considered Together | BOQ11–18 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.70 | −0.73 | −0.94 | −0.51 | |

| YABOQ | 0.02 | −0.12 | 0.16 | −0.11 | −0.27 | 0.05 | ||

| Family Function | Considered Alone | BOQ11–18 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.35 | −0.11 | −0.21 | −0.01 |

| YABOQ | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.15 | −0.04 | −0.16 | 0.08 | ||

| Considered Together | BOQ11–18 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.71 | −0.38 | −0.58 | −0.18 | |

| YABOQ | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.15 | −0.04 | −0.18 | 0.10 | ||

| Parental / Family Concern | Considered Alone | BOQ11–18 | −0.21 | −0.31 | −0.11 | −0.51 | −0.63 | −0.39 |

| YABOQ | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.26 | ||

| Considered Together | BOQ11–18 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.41 | −0.64 | −0.84 | −0.44 | |

| YABOQ | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.28 | ||

| School / Work Reintegration | Considered Alone | BOQ11–18 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.53 |

| YABOQ | −0.08 | −0.16 | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.17 | 0.03 | ||

| Considered Together | BOQ11–18 | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 0.21 | 0.57 | |

| ABOQ | −0.09 | −0.17 | −0.01 | −0.08 | −0.18 | 0.02 | ||

For adolescents, burns to critical areas affected scores on all subscales except for Appearance when considered alone. TBSA greater than or equal to 20% also significantly affected scores for all subscales except Pain and Satisfaction. When considering both critical areas and TBSA at the same time, all subscales were significantly impacted by the known covariates except for the effect of a burn to a critical area on School Reintegration.

Those results were in contrast to the results for young adults. TBSA significantly affected Itch and Family Concern either when considered alone or with critical areas (p < 0.05). Work Reintegration was significantly affected by burns to critical areas when considered alone or with TBSA (p < 0.05). All other subscales were not affected by the known covariates (p > 0.05).

Discussion

Burns can have long term lingering physical, psychological, and social effects. Clinical care and outcome researchers thus need to be able to follow child and adolescent burn survivors into adulthood. This is the first study to bridge scores from different BOQ forms, thereby allowing long-term follow-up studies of burn survivors from adolescence into adulthood. Our first hypothesis was supported: Bridges were credibly built from the BOQ11–18 to the YABOQ using an IRT-based NEAT design. The bridges were broadly similar regardless of whether survivors were allowed to contribute one data point or up to three data points. This sensitivity analysis benefits the current study and supports the robustness of results. Prior to this study, the BOQ could not be used longitudinally beyond the age range for which the scale was originally developed.

The second major finding to arise from this study relates to clinical covariates. Consistent with previous reports, burns to critical areas and large burns consistently emerged as significant predictors for adolescents,15,16 whereas research on burn size among young adults has been equivocal overall, with many domains not being associated with burn size.8,24 This is consistent with our findings as well, and supports our second hypothesis. This suggests that the effect of clinical covariates varies by form or separately by age. However, the design of this study does not permit us to disentangle these covariates. As future studies attempt to bridge recovery trajectories for burn survivors across wider age ranges, a greater understanding of these effects will be necessary.

While the results of the covariate analysis could be used to modify the bridges between BOQ forms, we have not suggested doing so at this time. To use this information in the actual bridges would require computerized scoring at each occasion, and would not allow easy conversions of aggregated data. This severely limits its utility in a fast-paced clinical setting which may or may not have the required clinical covariates immediately available for scoring, and may not have the computing resources for person-level score conversions. Rather, by not including the covariates in the actual bridges, simple look-up tables, like the ones in the supplementary online material, can be used.

The ability to transform scores across BOQ forms is vital for continued longitudinal research. The BOQ suite of measures are extremely valuable to researchers and clinicians measuring physical, emotional, and social outcomes among burn survivors. Most efforts to date have utilized only one BOQ form in a study, limiting comparisons over time. BOQ forms also use different centering scores for the T-scores. The BOQ11–18 T-scores are centered on a clinical sample of burn survivors, whereas the YABOQ is centered on a non-burned community sample. Previously, examination of T-scores without a conversion would be greatly mistaken. Raw scores are equally incomparable insofar as the number of items per subscale are not equal. Now that the BOQ11–18 and YABOQ have been bridged, the converted T-scores are comparable for the centering sample for the respective forms.

To date, recovery trajectories have been proposed for the BOQ11–1814 and for the YABOQ separately.13 Bridging the forms will allow future researchers to create recovery trajectories that exhibit greater robustness in terms of their clinical application. Already, this project allowed evaluation of differences in recovery trajectories over an expanded age range. When stratifying BOQ completions by time since burn, young adults experience poorer outcomes than adolescents on most subscales. More research examining recovery trajectories in the transition from childhood to adolescence and adolescence to young adulthood is necessary to fully understand how these age groups differ.

In order to bridge the forms, we used an IRT-based approach. Scores were scaled to an IRT-based metric from which expected scores on the other form could be determined. The IRT-based scores also include an estimate of reliability. Both the BOQ11–18 and YABOQ exhibited appropriate reliability for research and clinical applications. The lowest reliability for the BOQ11–18 consistently was on the Pain subscale. The Pain subscale is composed of two items: pain frequency, and a pain intensity numerical rating scale (NRS). The lower reliability could imply that adolescents are inconsistent in reporting their pain. Interestingly, the Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (PedIMMPACT) recommended use of a visual analog scale instead of a NRS for pain, largely because the reliability of the NRS hasn’t been consistently shown and is less frequently used among children and adolescents.25

For young adults, the lowest reliability was on the Physical Function subscale. This was an unexpected finding, insofar as the content of the YABOQ Physical Function subscale is broadly consistent with other questionnaires of physical function and is not overly specific to burn survivors. Other measures of reliability have supported the YABOQ Physical Function subscale (e.g. Cronbach’s alpha has previously been reported as 0.8813). While this IRT-based measure of reliability is not excessively low for young adults, further research is needed to explain this finding, including explicitly testing whether this is related to the presence or absence of a burn to the lower extremity.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. First is the relatively small sample size for YABOQ completions. With the strong assumption that the anchor items functioned equivalently across forms,17 even with minor wording changes, the sample size was adequate for fairly precise parameter estimates. A larger sample, however, would have allowed statistical evaluation of the anchor assumptions, and would have provided more power to detect an effect of clinical covariates. A second limitation also relates to the anchor. Previous research in educational testing has recommended that the anchor should comprise approximately 20% of a test and consist of no fewer than 15 items.26 However, given the constraints of clinical settings, requiring short forms, this suggestion is not reasonable for many health outcome measures, including the BOQ scales. Third, the confirmatory dimensionality assessments broadly supported the current structure, but an alternative structure could focus on higher-order constructs such as physical, emotional, and social health. This issue will become even more salient when future research extends these bridges to the Adult BOQ (ABOQ), which is currently in development. The ABOQ has fewer items than the YABOQ but almost the same number of subscales. Future research can investigate whether these higher-order constructs would be useful clinically, and if so, whether bridges could be built across forms based on higher-order constructs with more anchor items. Another limitation is that previous studies have reported on the effect of clinical covariates within a form, but no attempts have been made to examine how they affect recovery trajectories across forms. This examination of covariates, while useful in addressing recovery trajectories, was not included for bridging across the BOQ forms. A comparison of covariates across forms is nonetheless important, as it allows clinicians and researchers to evaluate expected and unexpected group differences. Future work can focus on this issue. A final limitation relates to the ability to cross-validate the bridging results. No one was administered both the BOQ11–18 and the YABOQ. Future work based upon cohorts in which subjects are administered both forms longitudinally will allow for comparison of predicted scores from one form onto the other with the actual scores obtained on that form. Cross-validating the bridges in this manner is an area for future research.

General Conclusions

This was the first study to build bridges across forms within the BOQ suite of measures. This holds potential for future longitudinal research and outcomes monitoring among burn survivors. More research is necessary to confirm the usefulness of these bridges and to develop longitudinal recovery trajectories that do not depend on only one form of the BOQ. Future studies should examine if or how other BOQ forms can be bridged, such as the parent-completed BOQ0–4 or BOQ5–18 or the ABOQ. These efforts will allow greater score comparability and applicability across settings.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This study was funded under an award from the John W. Alden Trust, from the Shriners Hospitals for Children Grant #70011, and from the NIDILRR Grant #90DP0035, NIDILRR Grant #90DP0055. The results of this study were not contingent upon sponsor approval and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the sponsoring organizations.

References

- 1.Goverman J, Mathews K, Goldstein R, et al. Adult Contractures in Burn Injury: A Burn Model System National Database Study. J. Burn Care Res. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider JC, Nadler DL, Herndon DN, et al. Pruritus in Pediatric Burn Survivors: Defining the Clinical Course. J. Burn Care Res. 2015;36(1):151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee AF, Ryan CM, Schneider JC, et al. Quantifying Risk Factors for Long-Term Sleep Problems after Burn Injury in Young Adults. J. Burn Care Res. 2015;Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter C, Tompkins RG, Finnerty CC, Sidossis LS, Suman OE, Herndon DN. The Metabolic Stress Response to Burn Trauma: Current Understanding and Therapies. The Lancet. 2016;388(10052):1417–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEntire SJ, Chinkes DL, Herndon DN, Suman OE. Temperature Responses in Severely Burned Children During Exercise in a Hot Environment. J. Burn Care Res. 2009;31(4):624–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazis LE, Lee AF, Rose M, et al. Recovery Curves for Pediatric Burn Survivors: Advances in Patient-Oriented Outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016;170(6):534–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goverman J, Mathews K, Nadler D, et al. Satisfaction with Life after Burn: A Burn Model System National Database Study. Burns. 2016;42(5):1067–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan CM, Lee A, Kazis LE, et al. Recovery Trajectories after Burn Injury in Young Adults: Does Burn Size Matter? J. Burn Care Res. 2015;36(1):118–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheridan RL, Hinson MI, Liang MH, et al. Long-Term Outcome of Children Surviving Massive Burns. JAMA. 2000;283(1):69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duke JM, Boyd JH, Randall SM, Wood FM. Long Term Mortality in a Population-Based Cohort of Adolescents, and Young and Middle-Aged Adults with Burn Injury in Western Australia: A 33-Year Study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015;85:118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kazis LE, Liang MH, Lee A, et al. The Development, Validation, and Testing of a Health Outcomes Burn Questionnaire for Infants and Children 5 Years of Age and Younger: American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children. J. Burn Care Res. 2002;23(3):196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daltroy LH, Liang MH, Phillips CB, et al. American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children Burn Outcomes Questionnaire: Construction and Psychometric Properties. J. Burn Care Res. 2000;21(1):29&hyhen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan CM, Schneider JC, Kazis LE, et al. Benchmarks for Multidimensional Recovery after Burn Injury in Young Adults: The Development, Validation, and Testing of the American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children Young Adult Burn Outcome Questionnaire. J. Burn Care Res. 2013;34(3):e121–e142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer III WJ, Lee AF, Kazis LE, et al. Adolescent Survivors of Burn Injuries and Their Parents’ Perceptions of Recovery Outcomes: Do They Agree or Disagree? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(3):S213–S220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmieri TL, Nelson-Mooney K, Kagan RJ, et al. Impact of Hand Burns on Health-Related Quality of Life in Children Younger Than 5 Years. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(3):S197–S204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner P, Stubbs TK, Kagan RJ, et al. The Effects of Facial Burns on Health Outcomes in Children Aged 5 to 18 Years. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(3):S189–S196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolen MJ, Brennan RL. Test Equating, Scaling, and Linking : Methods and Practices. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi SW, Schalet B, Cook KF, Cella D. Establishing a Common Metric for Depressive Symptoms: Linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS Depression. Psychol. Assess. 2014;26(2):513–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schalet B, Revicki D, Cook K, Krishnan E, Fries J, Cella D. Establishing a Common Metric for Physical Function: Linking the HAQ-Di and SF-36 Pf Subscale to PROMIS® Physical Function. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015;30(10):1517–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kazis LE, Lee AF, Hinson M, et al. Methods for Assessment of Health Outcomes in Children with Burn Injury: The Multi-Center Benchmarking Study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(3):S179–S188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai L. Metropolis-Hastings Robbins-Monro Algorithm for Confirmatory Item Factor Analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2010;35(3):307–335. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai L. Lord–Wingersky Algorithm Version 2.0 for Hierarchical Item Factor Models with Applications in Test Scoring, Scale Alignment, and Model Fit Testing. Psychometrika. 2015;80(2):535–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai L. A Two-Tier Full-Information Item Factor Analysis Model with Applications. Psychometrika. 2010;75(4):581–612. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hickerson W, Shapiro G, Jeng J, et al. The Effects of Burn Size on Long-Term Community Reintegration Outcomes: A Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (Libre) Study. Proceedings of the American Burn Association 48th Annual Meeting. J. Burn Care Res. 2016;37:S1–S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, et al. Core Outcome Domains and Measures for Pediatric Acute and Chronic/Recurrent Pain Clinical Trials: Pedimmpact Recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(9):771–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wainer H. Comparing the Incomparable: An Essay on the Importance of Big Assumptions and Scant Evidence. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 1999;18(4):10–16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.