Abstract

The relations between maternal sensitivity and infant negative emotionality have been tested extensively in previous literature. However, the extent to which these associations reflect unidirectional or bi-directional effects over time remains somewhat uncertain. Further, the possibility that maternal characteristics moderate the extent to which infant negative emotionality predicts maternal sensitivity over time has yet to be tested in cross-lag models. The goal of the current study is to address these gaps. First time mothers (N = 259; 50% White; 50% Black) and their infants participated when infants were 6-, 14-, and 26-months of age. Infant negative emotionality was assessed via maternal report and direct observation during standardized laboratory tasks, which were subsequently combined to yield a multimethod measure at each wave. Maternal sensitivity was observationally coded at each wave and mothers self-reported emotion dysregulation at 6- and 14-months. A random intercepts cross-lagged model with maternal emotion dysregulation specified as a moderator revealed that infant negative emotionality at 6-months was negatively associated with maternal sensitivity at 14-months, but only among mothers higher in emotion dysregulation. Higher maternal sensitivity was in turn associated with lower infant negative emotionality when infants were 26-months of age. The indirect pathway was significant, lending support for the transactional model. Implications for future research and prevention/intervention are discussed.

Keywords: maternal sensitivity, infant negative emotionality, maternal emotion dysregulation, transactional model, infant temperament

Scientists have long argued that parents play a role in shaping their children’s development, and since the 1960s, there has been attention to the possibility that children also shape parenting (Bell, 1968). Researchers have focused on the extent to which child temperament (i.e., individual differences in reactivity and regulation; Rothbart & Bathes, 2006), particularly negative emotionality, may contribute to parenting in the moment and longitudinally (e.g., Belsky & Rovine, 1987). Likewise, parenting contributes to change in temperament; infants who experience more sensitive caregiving (i.e., responsive, warm, and contingent parental responses) may experience a decline in negative emotionality over time (Bell & Ainsworth, 1979). In subsequent theorizing, Sameroff (2009) posited a model by which children and parents may influence one another in the moment and contribute to change in the other over time. This longitudinal chain of effects whereby a person affects their environment, which in turn, contributes to change in their own characteristics is known as the transactional model.

In the current study, we aimed to test a transactional model by which maternal sensitivity and infant negative emotionality have longitudinal effects on one another over the first two years of the infants’ life, while differentiating the between- and within-dyad effects over time. Infant negative emotionality, a core dimension of temperament is one of the most frequently examined infant predictors of subsequent developmental outcomes. Temperament is based in biology but is susceptible to influence from characteristics of the environment (Rothbart & Bates, 2006), including the caregiving environment. Identifying factors that may promote increases or decreases in negative emotionality over time is important given consistent evidence that heightened negative emotionality predicts a host of maladaptive outcomes, including externalizing and internalizing behavior problems and deficits in social skills (Pauli-Pott et al., 2007; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Maternal sensitivity is a critical aspect of infants’ early environmental experiences. Infants who receive more sensitive caregiving develop more adaptive emotional, behavioral, and physiological regulation compared to children who receive less sensitive caregiving and demonstrate lower behavioral and physiological stress reactivity (Calkins & Leerkes, 2004; Leerkes et al., 2009). Notably, in their foundational review and response to commentaries focused on emotion socialization, Eisenberg and colleagues (1998a; 1998b) asserted that emotion socialization is a transactional process whereby child behavior shapes subsequent emotionally relevant parenting and parenting shapes child outcomes including temperament.

Although many researchers have examined reciprocal and transactional effects between temperament and parenting, prior studies of this type tend to (1) rely primarily on mother-reported temperament, (2) focus predominately on negative parenting behaviors, and (3) ignore the possibility that other factors may moderate how infant negative emotionality and maternal sensitivity are related overtime. Examining a maternal characteristic as a moderator of this model is well justified given long-standing evidence that the effects of temperament on maternal behavior vary depending on mothers’ risks and available resources (Crockenberg, 1986; Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003). Previous research highlighting the negative effects of infant crying on parents’ emotional and cognitive processes (e.g., Leerkes et al., 2012) support our focus in the current study on maternal emotion regulation given that in the context of distress, caregivers are tasked with responding sensitively and responsively to their infant while also modulating their own arousal.

Associations between Temperament and Parenting

Parenting Predicts Temperament

Caregiving may contribute to infants’ negative emotionality in several ways. First, infants learn to minimize or maximize their distress based on how caregivers have responded to their distress in the past. Infants who learn that their mothers are inconsistently responsive tend to maximize their distress to promote the likelihood of maternal responses, and infants who learn that their mothers reject their distress cues tend to minimize their distress in order to prevent rejection from their mothers (Cassidy, 1994). This has been supported in more recent work (McKay et al., 2019), and appears to be long lasting, with parent-driven effects on temperament being observed through toddlerhood (Hentges et al., 2019) and into early adolescence (Briscoe et al., 2019). Longitudinal associations of infants’ minimization and maximization of distress in response to their history of caregiving can be seen across other domains, including maternal warmth (Van den Akker et al., 2014) and emotion socialization (Pérez-Edgar & Hastings, 2018). Second, parenting affects infant negative emotionality through the development of adaptive or maladaptive physiological reactivity and regulation. Early experiences with sensitive and responsive caregiving can provide a social buffer to stress reactivity as assessed via cortisol by the time infants are 12 months old (Bernard & Dozier, 2010; Gunnar & Donzella, 2002), and researchers have demonstrated that heightened cortisol reactivity is linked with later heightened infant negative emotionality (Braren et al., 2019). Overall, this body of work suggests that more sensitive caregiving promotes lower levels of negative emotionality, whereas insensitive caregiving increases negative emotionality in the moment and over time.

Temperament Predicts Parenting

Children’s temperament has been associated with parenting behaviors both concurrently and longitudinally across many domains of parenting and developmental periods (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). In particular, heightened negative emotionality makes parenting more difficult in two ways. First, children higher in negative emotionality are more demanding of their caregivers, and the frequency and intensity of infants’ distress, coupled with difficulty soothing such infants, contributes to parental fatigue and lower parenting self-efficacy (Kienhuis et al., 2010). Second, infant crying is an aversive sound that elicits strong physiological, emotional, and cognitive reactions in the moment (Leerkes et al., 2012), and it is possible that frequent exposure to this stressor may undermine cognitive and emotional processes that promote adaptive parenting.

Indeed, previous research demonstrates that infants who exhibit higher levels of negative emotionality during early infancy are more likely to have mothers who display negative affect during playful interactions throughout infancy and into toddlerhood, as well as over time (Dix & Yan, 2014), are less engaged in social interactions (Hibel et al., 2019), and are more likely to engage in harsh parenting (Armour et al., 2016; Hajal et al., 2015). Less work has examined negative emotionality in relation to positive caregiving, but some research demonstrates that infant negative emotionality undermines sensitive and responsive caregiving in the moment and over time (Leerkes, 2010; Woldarsky et al., 2019). In the current study, we aim to extend the latter by examining the concurrent and longitudinal implications of infant negative emotionality on maternal sensitivity, a positive caregiving construct.

Role of maternal emotion dysregulation.

Although the negative effect of infant negative emotionality on caregiving quality appears to be prevalent, observed effects are weak in magnitude, and explain relatively small amounts of the variance in parenting behaviors (see Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al., 2007 for a meta-analysis and evaluation of effect sizes). Crockenberg (1986; Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003) has argued that maternal characteristics may affect the degree to which infant negative emotionality undermines the quality of parenting. Not all mothers engage in less sensitive caregiving toward their highly reactive infant. Rather, certain characteristics of mothers (e.g., heightened depressive symptoms) or their environments (e.g., poor social support) may hinder effective caregiving to infants that are more easily and intensely distressed. Thus, in the current study, we examined the degree to which maternal emotion dysregulation served as a moderator of the association between infant negative emotionality and maternal sensitivity. We focus on maternal regulation for two primary reasons. First, given the aversive and arousing nature of infant negative emotionality, individual differences in mothers’ ability to regulate their own emotions may play a critical role in determining their capacity to prioritize and respond sensitively to their infants, particularly over time as the stress of caring for a challenging infant may accrue. Second, a focus on maternal emotion regulation is well-justified by existing theoretical frameworks. Specifically, Eisenberg et al.’s (1998) model of emotion socialization and Dix’s (1991) affective organizational model of parenting both note parent emotion characteristics, such as arousal and regulation, are central predictors of parenting in emotionally arousing situations, which likely modulate how parents respond in the face of challenging child behaviors or traits. This is a critical gap in the literature as it has only been tested using a microanalytic timeframe (Scott et al., 2020). Mothers who responded more negatively to aversive child behaviors on days when they felt more dysregulated compared to days they felt less dysregulated.

Transactional Effects Over Time

Taken together, these bodies of research suggest that bidirectional, transactional effects between negative emotionality and parenting behaviors are probable. A cross-lagged design is optimal for examining transactional associations because it allows for the differentiation between infant and mother-driven effects while controlling for stability over time and within time associations between variables of interest. Overall, there have been mixed findings in these studies, with some demonstrating there are no significant cross-lag effects from mothers or children (e.g., Verhage et al., 2015; Wittig & Rodriguez, 2019). Other studies only find support for mother-driven effects (i.e., parenting affecting later infant negative emotionality; Cha, 2017; Klien et al., 2018), with such effects being somewhat more prominent during early infancy (Perry et al., 2018; Scaramella et al., 2008). In contrast, studies beginning later in infancy have demonstrated child-driven effects, specifically, higher negative emotionality predicted increases in parent over-reactivity from 10-months to 27-months (Lipscomb et al., 2011). Finally, Perry and colleagues (2018) demonstrated that infant negative emotionality at 5 months was associated with increases in maternal intrusiveness at 10 months, which was in turn associated with more infant negative emotionality at 24 months. The latter results provide the strongest evidence of the transactional model given infants contributed to change in their environment, which then altered their own developmental trajectory.

Current Study

The above cited studies that employed the transactional model to study associations between infant negative emotionality and parenting are characterized by an important methodological limitation, and important gaps remain in this area of inquiry that we address in the current study. First, most relied solely on mother-reported infant negative emotionality, which could be biased based on mothers’ perceptions of the infant, mothers’ mood or personality, and factors like maternal depression (Stifter & Dollar, 2016). Perry et al. (2018) specifically called for future research to utilize observationally coded infant negative emotionality measures, while also acknowledging the benefits of mother-report. Thus, in the current study, we used a multi-method approach of measuring infant negative emotionality by utilizing both mother-report and observed infant negative emotionality. Second, with the exception of Cha (2017), the above studies focus on associations between infant negative emotionality and negative parenting behaviors, such as intrusiveness, parental control, and harsh parenting. We examine longitudinal and transactional associations between maternal sensitivity, a positive aspect of parenting, and infant negative emotionality, which is important given that previous work has established the importance of maternal sensitivity for many social and emotional outcomes. Third, prior studies focus on main effects, despite evidence that negative effects of infant negative emotionality on parental outcomes are more prevalent among mothers with other risk factors (Crockenberg, 1986; Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al., 2007). Unexamined moderators could be one reason the extant literature provides mixed support for the presence of child-driven effects. Thus, we examine maternal emotion dysregulation as a moderator of the cross-lagged paths from infant negative emotionality to subsequent maternal sensitivity. Fourth, we employ the random intercepts cross-lagged panel model (RICLPM) which tests bidirectional effects while disaggregating the between- and within-person effects over time. This approach is superior to the basic cross-lagged model in that estimations in the basic model can be biased and inflated given the conflation of between- and within-person effects.

We hypothesized that after accounting for stability and concurrent associations: 1) higher levels of maternal sensitivity at 6-months and 14-months would be associated with lower levels of infant negative emotionality at 14-months and 26-months, 2) higher levels of infant negative emotionality at 6-months and 14-months would be associated with lower levels of maternal sensitivity at 14-months and 26-months, and 3) maternal emotion dysregulation would moderate the association between 6-month and 14-month infant negative emotionality and later maternal sensitivity, such that for mothers higher in emotion dysregulation, the effect of infant negative emotionality on sensitivity would be stronger. We anticipated two possible indirect effects. First, insensitive maternal behavior may lead to subsequent insensitive behavior over time via heightened infant negative emotionality. Second, infant negative emotionality may contribute to elevated subsequent negative emotionality by undermining maternal sensitivity, particularly in dyads where mothers have higher emotion dysregulation. Given that we were interested in both the moderating effects of maternal emotion dysregulation and the indirect effects of sensitivity and infant temperament over time, it is possible that conditional indirect effects would emerge; the indirect effect would be significant for mothers higher or lower in emotion dysregulation.

Method

Participants

Participants included 259 first time mothers (131 African American, 128 European American) and infants when infants were 6- (n = 230; 50% female; n = 15 questionnaire only), 14- (n = 227; n = 19 questionnaire only), and 26-months (n = 214; n = 15 questionnaire only) of age. Participants were recruited from childbirth and breastfeeding classes, obstetrics and gynecology practices, and word of mouth. At the prenatal wave (about 6–8 weeks before mothers’ due date), mothers ranged from 18 to 44 years of age (M = 25.05, SD = 5.41). Maternal education varied: 27% of mothers had a high school diploma or less, 27% had attended some college, and 46% had at least a 4-year degree. Annual income ranged from less than $2,000 to over $100,000 (median = $35,000). Most mothers reported being married to or living with their child’s father (57%), 24% were dating, but not living with their child’s father, and 19% were single. Attrition/missing data over time was due to participants moving, infant mortality, being too busy to participate, and inability to contact participants despite multiple attempts. Missingness was not associated with most key demographic variables (i.e., income-to-needs, marital status, race, or experience with infants). Mothers who completed more waves of data collection were older (r = .15, p < .05) and had higher levels of education (r = .17, p < .01).

Procedures

Upon enrollment in the study, mothers were mailed a packet of questionnaires to collect demographic information. During the follow-up waves, mothers completed questionnaires about their infants’ temperament and maternal emotion dysregulation and attended a laboratory session with their infant in which dyads participated in distress-electing tasks. With the exception of the Still-Face paradigm at 6-months and the clean-up task at 26-months, all distress eliciting tasks were 4 minutes. Mothers were instructed not to interact with infants until signaled by the experimenter after 1 minute, and for the remaining 3 minutes mothers were allowed to interact however they wanted with infants without interfering with the task. At 6-months, distress-eliciting tasks included an arm restraint, novel toy approach, and Still-Face paradigm. For the arm restraint, an experimenter knelt in front of infants and gently held their forearms. For the novel toy approach, a loud remote-controlled dump truck moved toward and away from the infant. At 6-months, dyads also participated in the Still-Face Paradigm, where mothers and infants were seated across from each other and engaged in three episodes: engage, still-face, and re-engage, each lasting two minutes long. At 14-months, distress-eliciting tasks included the toy removal and novel character approach. For the locked jar, an attractive toy phone was placed in a plastic jar that infants were unable to open. For the novel character approach, an assistant wearing a character mask entered the room, approached the infant, and interacted with infants in unpredictable ways (e.g., singing, dancing, talking to infants). At 26-months, the distress-eliciting tasks included toy clean-up, locked box, and spider approach. After the 7-minute free play session, an experimenter entered the room and gave the mother and child two plastic containers and instructed mothers to get their child to clean up all of the toys. Mothers were told that they could accomplish this any way they wanted, but they must involve their child. The clean-up task lasted for 5 minutes or until all of the toys were cleaned up. For the locked box, an attractive toy was placed into a locked plastic box. The experimenter showed infants how to unlock the box using a set of keys, and then gave infants a set of keys that would not open the box. For spider approach, a large spider strapped to a remote-controlled car approached and withdrew from children. All procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina Greensboro Internal Review Board (Protocol #09–0035).

Measures

Infant Negative Emotionality

Infant negative emotionality was assessed via a maternal report measure and observationally coded infant distress. Mothers completed the Infant Behavior Questionnaire – Revised Very Short Form (IBQ-RVSF; Putnam et al., 2014) at 6- and 14-months and the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire – Very Short Form (ECBQ-VSF; Putnam et al., 2006) at 26-months. Both measures have been used extensively in previous work and demonstrate internal consistency reliability and convergent validity with other measures infant temperament (Putnam et al., 2014; Putnam et al., 2006). Both measures include 12 items that ask mothers to report the frequency of their infants’ negative emotionality in response to common situations (e.g., When meeting a stranger, how often does your baby show distress?) on a 7-point scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always) over the last 2 weeks. Internal consistency reliability was adequate for 6-, 14- and 26-months: αs = .74, .82, and .74, respectively.

Infant affect was continuously rated from videos of the distress-eliciting tasks at each wave on a 7-point scale from 1 (high positive affect) to 7 (high negative affect) (adapted from Braungart-Rieker & Stifter, 1996) using INTERACT 9 (Version 9; Mangold, 2011). Mean distress was calculated for each task at each wave with higher scores reflecting higher duration and intensity of distress. Almost all infants (6-months: 97%, 14-months: 91%, 26-months: 97%) displayed some distress at each wave, although episodes of distress were brief, and few infants displayed brief instances of positive affect resulting in mean affect scores between 4 (neutral) and 5 (mild negative affect) (6-months: M distress = 4.43, SD = .43; 14-months: M distress = 4.19, SD = .27; 26-months: M distress = 4.19, SD = .26). Coders were blind to other data and reliability cases were selected at random. Disagreements were resolved via consensus coding. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using weighted kappa based on 15 to 25% of double coded cases for each wave (6-month κ = .76; 14-month κ = .75; 26-month κ = .81).

For each wave, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted that included the IBQ/ECBQ negative emotionality score and mean observed distress for each observational task. At each wave a one-factor structure was revealed with an Eigen factor greater than 1 explaining 88% of the variance at 6-months and 14-months and 0% at 26-months. Thus, scores were standardized and averaged to create a single multi-method negative emotionality score.

Maternal Sensitivity

Maternal sensitivity was rated separately for the free play task and each distress task at each wave using Ainsworth’s 9-point sensitivity scale (Ainsworth et al., 1974). Scores range from 1 (highly insensitive; inconsistently responsive, responses are inappropriate or fragmented) to 9 (highly sensitive; mothers are attuned to infants’ behaviors, perceives infants’ signals quickly and acts accordingly). Coders were trained on the scale and inter-rater reliability was assessed via randomly assigned double-coded cases (6-month: N = 26, 13%; 14-month N = 40, 20%; and 26-month: N = 30, 15%); intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from .74 to .92. Sensitivity scores were computed by averaging ratings across tasks within waves to create one overall sensitivity score (α = .89, .84, and .87 for 6-, 14-, and 26-months, respectively).

Maternal Emotion Dysregulation

Mothers completed the Difficulties with Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) at 6- and 14-months. This measure has been used in non-clinical samples, demonstrates test-retest reliability, good internal consistency reliability, convergent validity with other self-reports about emotion, and predictive validity to infant and mother outcomes (e.g., Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Leerkes et al., 2020). The DERS is a 36 item measure in which participants respond to items like “When I am upset, I feel out of control,” on a 5-point scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Items were averaged together to create a total score at each wave (α = .93 for both), with higher scores representing more emotion dysregulation.

Data Transparency and Openness

Hypotheses and data analysis plans were not preregistered. Data and code are not publicly available. Additional information regarding data, analyses, code, and study protocols may be obtained from the authors upon request.

Results

Analytic Plan

Preliminary analyses were conducted to examine descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among variables of interest (Tables 1 and 2). The main analyses that examined the associations between maternal sensitivity and infant negative emotionality were estimated using a random intercepts cross-lagged panel model (RICLPM; Usami, 2021) in Mplus (Version 8; Muthén & Muthén, 2017). The RICLPM is advantageous in that, by design, the model differentiates between- and within-dyad effects, allowing us to see how constructs change and are related to each other over time without influence from between-person variance. Mplus uses full information maximum likelihood, which allows for the examination of all available data, regardless of missingness. Following procedures by Usami (2021), fitting a RICLPM includes: 1) specifying latent between-person individual difference factors for maternal sensitivity and infant negative emotionality; 2) centering the within-person variables by specifying latent variables with single manifest indicators of maternal sensitivity and infant negative emotionality at each timepoint; 3) constraining measurement error variances for each manifest indicator to 0; 4) specifying cross-lagged effects between within-person variables; 5) specifying covariances between the within-person variables; and 6) constraining the correlations of the between-person factors and other exogenous variables to be 0. After specifying this model, we also fitted a model that included maternal emotion regulation as a moderator of the association between infant negative emotionality and maternal sensitivity at each cross-lagged path using latent variable moderation (see Muthén & Asparouhov, 2003). Significant interactions were probed one standard deviation above and below the mean of emotion dysregulation to test for simple slopes (Aiken & West, 1991). Indirect effects and conditional indirect effects were tested when both the path from maternal sensitivity to subsequent infant negative emotionality (or the interaction with the path) and path from infant negative emotionality to subsequent maternal sensitivity were both significant. Given the nature of RICLPMs, the effects of time-invariant covariates are implicitly controlled (Usami et al., 2019). Thus, no covariates were included in the statistical model.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Varaibles of Interest

| M | SD | Min. | Max. | Skew | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1. 6m Maternal Sensitivity | 4.99 | 1.44 | 1.67 | 8.00 | −0.06 | −1.08 |

| 2. 14m Maternal Sensitivity | 5.46 | 1.68 | 1.50 | 9.00 | −0.11 | −0.64 |

| 3. 26m Maternal Sensitivity | 6.09 | 1.50 | 1.67 | 9.00 | −0.41 | −0.72 |

| 4. 6m Infant NE | 0.01 | 0.79 | −1.50 | 1.99 | 0.38 | −0.49 |

| 5. 14m Infant NE | 0.01 | 0.80 | −1.71 | 2.92 | 0.65 | 0.70 |

| 6. 26m Infant NE | −0.01 | 0.81 | −1.58 | 2.59 | 0.97 | 0.95 |

| 7. 6m Maternal Emot. Dyreg. | 1.71 | 0.45 | 1.00 | 3.66 | 1.60 | 3.58 |

| 8. 14m Maternal Emot. Dysreg. | 1.86 | 0.51 | 1.00 | 3.59 | 1.07 | 0.79 |

Note. M = months. NE = negative emotionality.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Variables of Interest.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1. 6m Maternal Sensitivity | -- | ||||||

| 2. 14m Maternal Sensitivity | .64** | -- | |||||

| 3. 26m Maternal Sensitivity | .64** | .67** | -- | ||||

| 4. 6m Infant NE | −.27** | −.26** | −.18** | -- | |||

| 5. 14m Infant NE | −.15* | −.33** | −.28** | .31** | -- | ||

| 6. 26m Infant NE | −.31** | −.35** | −.48** | .19** | .29** | -- | |

| 7. 6m Maternal Emot. Dyreg. | .11 | .00 | −.03 | .12t | .16* | .02 | -- |

| 8. 14m Maternal Emot. Dysreg. | −.26** | −.17* | −.28** | .07 | .18** | .23** | .70** |

Notes. M = months. NE = negative emotionality. Emot. Dysreg. = emotion dysregulation

p < .05

p < .01

p < .10.

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics for the main study variables are presented in Table 1. All variables were normally distributed. Of note, maternal sensitivity was highly correlated over time (rs = .64, .64, and .67). Infant negative emotionality was moderately correlated over time (rs = .31, .19, and .29). Further, maternal sensitivity and infant negative emotionality were negatively correlated both within timepoint (e.g., 6-month maternal sensitivity and 6-month infant negative emotionality r = −.27) and longitudinally (e.g., 6-month infant negative emotionality with 14-month maternal sensitivity r = −.26).

Random Intercepts Cross-Lagged Panel Model

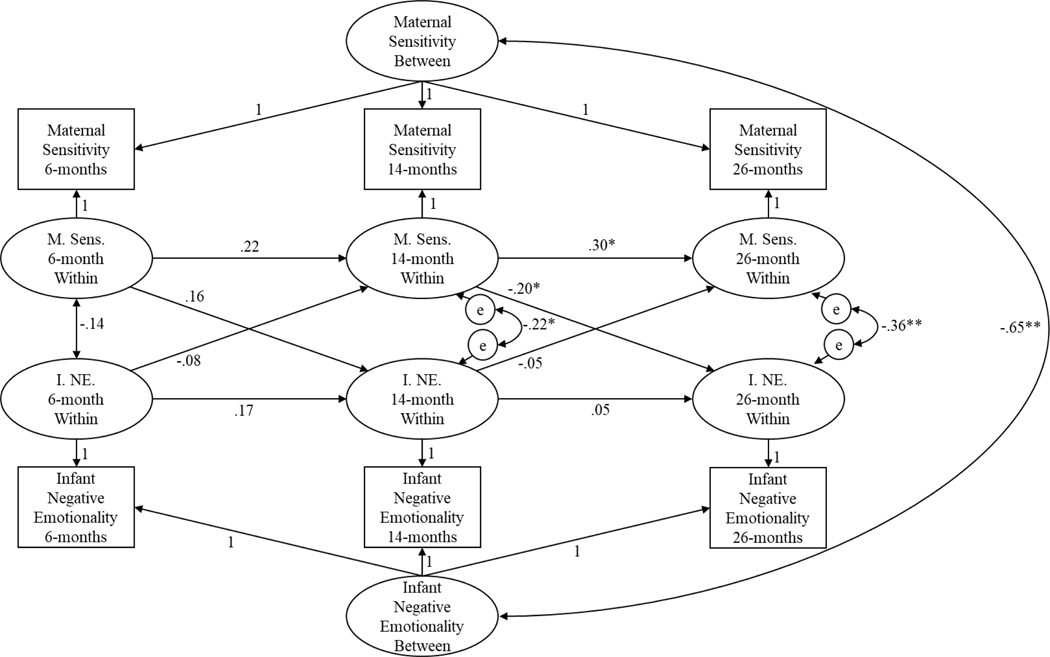

The RICLPM (Figure 1) demonstrated excellent fit across all indicators of model fit, χ2(1) = 2.23, p = .14; RMSEA = .071, 90% CI [.000, .202]; CFI = .996; SRMR = .021. There was a significant negative between-person correlation between maternal sensitivity and infant negative emotionality (β = −.65, p < .001), suggesting that on average, higher maternal sensitivity was correlated with lower infant negative emotionality. Within-person within-timepoint correlations between infant negative emotionality and maternal sensitivity at 6-months were not statistically significant (β = −.14, p = .17), but were statistically significant at 14-months (β = −.22, p = .03) and 26-months (β = −.36, p < .001). Maternal sensitivity was not significantly stable from 6- to 14-months (β = .22, p = .11) but was significantly stable from 14- to 26-months (β = .30, p = .02). Infant negative emotionality did not demonstrate statistically significant stability from 6- to 14-months (β = .17, p = .17) or from 14- to 26-months (β = .05, p = .65). Only one lagged effect was statistically significant, such that higher maternal sensitivity at 14-months was associated with lower infant negative emotionality at 26-months (β = −.20, p = .049).

Figure 1.

RICLPM Testing associations between maternal sensitivity and infant negative emotionality

Note. M. Sens. = Maternal Sensitivity; I. NE. = Infant Negative Emotionality. Values are standardized coefficients. *p < .05, **p < .01.

Moderation and Conditional Indirect Effects.

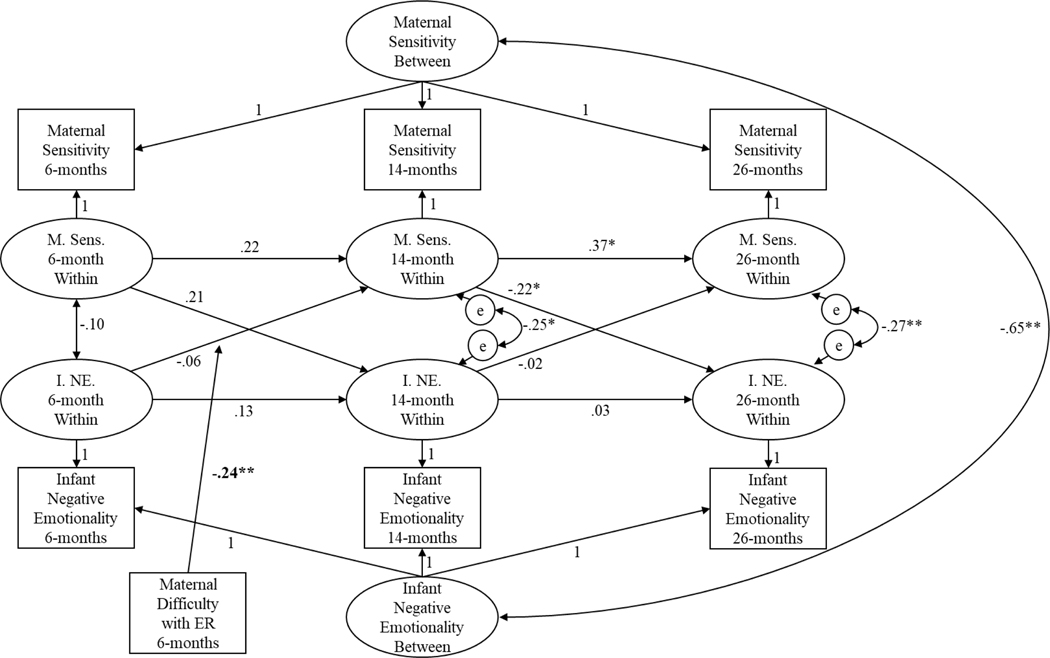

Next, a model with moderation was specified. Specifically, 6-month infant negative emotionality by 6-month maternal emotion dysregulation was specified to predict 14-month sensitivity and 14-month infant negative emotionality by 14-month maternal emotion dysregulation was specified to predict 26-month sensitivity. In the moderated cross-lagged model, only the first interaction was significant, and thus, the 14-month interaction was removed. The final path model is presented in Figure 2. Model fit was good across all indicators of fit, χ2(3) = 5.38, p = .15; RMSEA = .057, 90% CI [.000, .134]; CFI = .993; SRMR = .023. The interaction between 6-month infant negative emotionality and 6-month maternal emotion dysregulation was statistically significant (β = −.24, p = .004). For mothers higher in emotion dysregulation, there was a negative association between infant negative emotionality at 6-months and maternal sensitivity at 14-months (β = −.25, p = .01). This effect was not significant for mothers lower in emotion dysregulation (β = .16, p = .26).

Figure 2.

RICLPM with moderators of emotion regulation

Note. M. Sens. = Maternal Sensitivity; I. NE. = Infant Negative Emotionality. Values are standardized coefficients. *p < .05, **p < .01.

As a final step, a conditional indirect effect was tested to determine if the indirect effect from 6-month infant negative emotionality to 14-month maternal sensitivity to 26-month infant negative emotionality was significant in dyads in which mothers were higher in emotion dysregulation. The conditional indirect effect was significant at 90% CI, B = .07, SE = .04, β = .06, 90% CI [.008, .180]. Thus, infants who were higher in negative emotionality elicited less sensitive care over time if their mothers were higher in emotion dysregulation, which in turn predicted more infant negative emotionality at 26-months.

Discussion

In the current study, we used a transactional random intercepts cross-lagged panel model design to examine how maternal sensitivity and infant negative emotionality were associated with each other across three timepoints throughout infancy. Further, we examined the degree to which maternal emotion dysregulation moderated the association between infant negative emotionality and later maternal sensitivity. Our results provide support for transactional associations between infant negative emotionality and maternal sensitivity, but only when mothers have more difficulty regulating their own emotions.

Stability and Concurrent Associations

We found that maternal sensitivity was stable, but only during later infancy. This is likely due to the disentanglement of between- and within-person effects, given that our preliminary correlations would suggest that maternal sensitivity is stable across infancy, which would be consistent with other research that has examined parenting behaviors over time e (Cha et al., 2017; Perry et al., 2018; Perry et al., 2014). Compared to other studies that have examined stability in temperament (e.g., Bornstein et al., 2015; Perry et al., 2018), our stability coefficients were lower likely due to the analytic technique extrapolating between-person and within-person effects and differences in the measurement of infant negative emotionality (e.g., mother report only in previous work vs. our use of multiple assessments). It is possible that our stability coefficients were lower in magnitude because observed distress is less stable over time compared to mother report. In follow-up analyses, we found this to be the case in our sample, such that stability coefficients for observed distress ranged from .10 to .15 and stability coefficients for mother-reported negative emotionality ranged from .38 to .43 (comparable to that of other research; ranged from .35 to .41). Notably, these follow-up correlations do not account for removing the between-person effects like the main analyses do. Observations based on behavior in a single day are expected to be less stable over time compared to maternal reports of temperament which are based on infants’ typical behavior over the past two weeks.

In the current study, we found an overall negative association between average maternal sensitivity and average infant negative emotionality (between-person effect), consistent with prior research (Leerkes & Wong, 2012). The timepoint-specific associations were not significant at 6-months, but were significant, negative, and moderate in magnitude for 14- and 26-months. One explanation for this could be that as caregivers and infants spend more time together and develop a longer relational history, it is possibly that negative behavior from one member of the dyad has greater potential to erode the behavior of the other. A limitation of these concurrent associations is that the directionality of the associations is unclear, underscoring the value of the longitudinal model.

Cross-lagged and Transactional Effects

We did not find any evidence of child-driven effects without considering the effects of moderation. In the moderated model, there was a child effect from infant negative emotionality at 6-months to subsequent sensitivity at 14-months among mothers with more emotion regulation problems. That we found child-driven effects under certain conditions supports our view that some previous work may have failed to find evidence of child-driven effects due to untested moderators. These results support previous work suggesting that infant negative emotionality does not affect all mothers the same way, but rather, certain maternal characteristics may exacerbate the negative effects of infant distress on caregiving (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2003). Infant distress is aversive and arousing, and mothers who struggle to regulate their emotions may be particularly inclined to engage in insensitive behavior when infants higher in negative emotionality are distressed, but also when they are non-distressed because they may be burnt out from responding to frequent and intense distress cues and miss opportunities to engage positively when their infants are in positive states (van den Boom & Hoeksma, 1994). However, this interaction effect was only significant during early infancy (i.e., 6-months predicting 14-month maternal sensitivity). That the interaction between infant negative emotionality and maternal emotion dysregulation was not significant later in infancy may be a function of the demands of parenting an infant early in the first year of life that subsequently subside. Coping with infants’ heightened negative emotionality may be particularly challenging during the first 6 months when coupled with additional stressors such as fatigue caused by frequent night wakings (Trifu et al., 2019), making maternal regulatory abilities particularly important at this time. By the time infants reach 14- and 26-months of age, maternal hormones are highly likely to have re-stabilized (Trifu et al., 2019), infants sleep becomes more consolidated and predictable, and new parents have gained confidence their parenting (Leerkes & Burney, 2007). Thus, mothers may be better able to cope with infant negative emotionality later in infancy regardless of individual differences in their regulatory capacities.

Both the simple RICLPM and the model with moderators revealed that 14-month maternal sensitivity was predictive of lower subsequent infant negative emotionality at 26-months supporting the view that temperament is influenced by the environment (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Infants who experience high quality caregiving have more opportunities to develop adaptive emotion regulation skills that may minimize displayed negative emotionality (Leerkes et al., 2009). The evidence of mother-driven effects during late infancy is consistent with some previous research (e.g., Cha, 2017; Perry et al., 2018). The indirect effect from 6-month infant negative emotionality to 26-month infant negative emotionality through 14-month maternal sensitivity was significant, but only for dyads in which mothers were higher in emotion dysregulation. The transactional pattern may occur because infants who experience insensitive parenting may heighten their emotional distress to elicit caregiving from their mothers (Cassidy, 1994) and/or may experience worse physiological regulation (Calkins & Leerkes, 2004) over time which contributes to greater negative emotionality.

Inconsistent with prediction and previous work (e.g., Leerkes & Wong, 2012), early maternal sensitivity (i.e., 6 months) was not associated with later negative emotionality. Throughout infancy, distinct domains of self-regulation (e.g., behavioral, physiological) develop extensively, but perhaps on different timetables. It is possible that it takes longer before maternal sensitivity contributes to sufficient enhancements in emotion regulation that would elicit a change in infants’ propensity to display negative emotion. Early sensitivity may enhance physiological regulation earlier in infancy and alter behavioral expressions of negative affect later. Thus, perhaps incorporating a physiological indicator of arousal and emotionality such as baseline RSA which is thought to reflect infants’ trait-like responses to the environment may yield different results (Perry et al., 2018; Perry et al., 2014).

Taken together, these results have applied implications. Maternal emotion regulation appears to serve a critical role in promoting sensitive responding when faced with an infant high in negative emotionality, at least early in infancy, which in turn serves to reduce infant negative emotionality over time. Thus, enhancing expectant or early post-partum mothers’ emotion regulation skills may increase maternal sensitivity, resulting in lower levels of negative emotionality over time. Enhancing maternal emotion regulation skills by focusing on emotion coaching, cognitive reframing, and emotional awareness has been demonstrated to be effective in promoting positive caregiving (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2019). Such efforts may be particularly important for mothers whose infants who are more easily and intensely distressed.

Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

The current study has several strengths. First, the sample was intentionally recruited so that half of the mothers were European American, and half were African American. Much of the previous work examining transactional models were completed using mostly homogenous samples regarding race and ethnicity. Additionally, the sample was diverse with respect to indices of socio-economic status such as education and income. Second, this was a multi-method study that drew from mother reported information (i.e., infant negative emotionality and maternal emotion dysregulation) and observationally coded infant and mother behavior using well-established observational tasks and coding schemes (i.e., infant distress and maternal sensitivity). Specifically, the multi-method measure of infant negative emotionality was responsive to Perry et al.’s (2018) call for a more integrated and comprehensive examination of infant negative emotionality that does not solely rely on potentially biased maternal reports.

A number of limitations also warrant discussion. First, this was a community sample, and it is possible that samples with higher levels of maternal emotional risk, such as high regulatory difficulties (e.g., Ostlund et al., 2019) or psychopathology may yield different results. Second, the observational tasks were brief, and the distress tasks were designed to elicit heightened distress and may not reflect how the infant behaves in typical daily life. Thus, future work should utilize longer observations and incorporate home observations to capture infant temperament in a routine setting. Relatedly, we did not establish measurement invariance for infant negative emotionality across the waves of assessment. Although establishing measurement invariance would be ideal, there is not a single measure or series of tasks that are appropriate for 6-, 14-, and 26-month-old infants, thus, tasks must be updated for developmental appropriateness. Measurement invariance has been established for the maternal report measures of infant negative emotionality (see Putnam et al., 2008), but efforts have not yet been set forth for observed measures of temperament across infancy. Fourth, we only examined a maternal characteristic as a moderator of child effects on sensitivity and did not consider the possibility that other child characteristics, such as perceptual sensitivity, attentional control, and emotion regulation, operate as moderators of parent effects on negative emotionality. Such an approach is warranted based on the differential susceptibility perspective (Ellis et al., 2011) and should be examined in future research. Fifth, the time interval varied between data collection waves. Eight months passed between the 6-month and 14-month assessments and 12 months passed between the next two. A cross-lagged panel model does not allow for the weighting of time, and thus, we may be missing critical regulatory developmental processes. Future work should utilize longitudinal growth curve modeling to allow for the weighting of time to examine time-sensitive linear change. Last, although we view our approach of aggregating across multiple contexts (i.e., distress and non-distress) a strength of the current study, it is possible that there may be differences in how infant negative emotionality develops in the context of maternal sensitivity to distress specifically (Leerkes, 2010). Future work in which sensitivity to distress and non-distress are each measured across multiple tasks for longer periods of time at each wave would be ideal for comparing cross-lagged effects from each parenting context.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study contributes to the literature on the development of negative emotionality throughout infancy and the predictors of maternal sensitivity. In particular, this study provides evidence to suggest that mothers and infants both contribute to the development of infant negative emotionality over time. Consistent with the transactional model, infants high in negative emotionality elicited a decline in maternal sensitivity over time, under certain conditions, which in turn increased infant negative emotionality. Utilizing transactional models in future work can shed light on the role that mothers have in the development of infant negative emotionality. Further, the current study underscores the importance of understanding the interplay between infant and mother characteristics in predicting sensitive caregiving and longer-term child outcomes and underscores the value of focusing on maternal emotion dysregulation specifically.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Grant R01HD058578 (EML). LGB’s time was supported, in part, by T32MH18921. The contents of this manuscript are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development or the National Institute of Mental Health. Thanks to Savannah Girod for her invaluable feedback on this paper. We are grateful to the participants for their time and to Dr. Reagan Burney and project staff for their dedication. The hypotheses and analyses for this study were not pre-registered. Data and code are available upon request.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Bell SM, & Stayton DF (1974). Infant-mother attachment and social development: Socialization as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In Richards MPM (Ed.), The integration of a child into a social world. (pp. 99–135). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Armour J, Joussemet M, Kurdi V, Tessier J, Boivin M, & Tremblay RE (2018). How toddlers’ irritability and fearfulness relate to parenting: A longitudinal study conducted among Quebec families. Infant and Child Development, 27, 1–16. 10.1002/icd.2062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ (1968). A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review, 75, 81–95. 10.1037/h0025583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SM, & Ainsworth MDS (1979). Infant crying and maternal responsiveness. Child Development, 43, 1171–1190. 10.2307/1127506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, & Rovine M. (1987). Temperament and attachment security in the strange situation: An empirical rapprochement. Child Development, 58, 787–795. 10.2307/1130215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, & Dozier M. (2010). Examining infants’ cortisol responses to laboratory tasks among children varying in attachment disorganization: Stress reactivity or return to baseline? Developmental Psychology, 46, 1771–1778. 10.1037/a0020660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braren SH, Perry RE, Ursache A, & Blair C. (2019). Socioeconomic risk moderates the association between caregiver cortisol levels and infant cortisol reactivity to emotion induction at 24 months. Developmental Psychobiology, 61, 573–591. 10.1002/dev.21832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Gartstein MA, Hahn C, Auestad N, & O’Connor DL (2015). Infant temperament: Stability by age, gender, birth order, term status, and socioeconomic status. Child Development, 86, 844–863. 10.1111/cdev.12367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD & Leerkes EM (2004). Early attachment processes and the development of emotional self-regulation. In Baumeister RF & Vohs KD (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications. (pp. 324–339). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. (1994). Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. The Development of Emotion Regulation, 228–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha K. (2017). Relationships among negative emotionality, responsive parenting and early socio-cognitive development in Korean children. Infant and Child Development, 26. 10.1002/icd.1990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SB (1986). Are temperamental differences in babies associated with predictable differences in care giving? New Directions for Child Development, 31, 53–73. 10.1002/cd.23219863105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, & Leerkes EM (2003). Parental acceptance, postpartum depression, and maternal sensitivity: Mediating and moderating processes. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 80–93. 10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, & Yan N. (2014). Mothers’ depressive symptoms and infant negative emotionality in the prediction of child adjustment at age 3: Testing the maternal reactivity and child vulnerability hypotheses. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 111–124. 10.1017/S0954579413000898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce T, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & van IJzendoorn MH (2011). Differential susceptibility to the environment: A evolutionary-neurodevelopment theory. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 7–28. 10.1017/S0954579410000611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, & Donzella B. (2002). Social regulation of the cortisol levels in early human development. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 27, 199–220. 10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00045-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajal N, Neiderhiser J, Moore G, Leve L, Shaw D, Harold G, Scaramella L, Ganiban J, & Reiss D. (2015). Angry responses to infant challenges: Parent, marital, and child genetic factors associated with harsh parenting. Child Development, 86, 80–93. 10.1111/cdev.12345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibel LC, Mercado E, & Valentino K. (2019). Child maltreatment and mother-child attunement and transmission of stress physiology. Child Maltreatment, 24, 340–352. https://doi.org/10.1177-1077559519826295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienhuis M, Rogers S, Giallo R, Matthews J, & Treyvaud K. (2010). A proposed model for the impact of parental fatigue on parenting adaptability and child development. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 28, 392–402. 10.1080/02646830903487383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM (2010). Predictors of maternal sensitivity to infant distress. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10, 219–239. 10.1080/15295190903290840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, & Burney RV (2007). The development of parenting efficacy among new mothers and fathers. Infancy, 12, 45–67. 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2007.tb00233.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, & Crockenberg SC (2003). The impact of maternal characteristics and sensitivity on the concordance between maternal reports and laboratory observations of infant negative emotionality. Infancy, 4, 517–539. 10.1207/S15327078IN0404_07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Blankson AN, & O’Brien M. (2009). Differential effects of maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress on social-emotional functioning. Child Development, 80, 762–775. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01296.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Su J, & Sommers SA (2020). Mothers’ self-reported emotion dysregulation: A potentially valid method in the field of infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41, 642–650. 10.1002/imhj.21873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Weaver JM, & O’Brien M. (2012). Differentiating maternal sensitivity to infant distress and non-distress. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12, 175–184. 10.1080/15295192.2012.683353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, & Wong MS (2012). Infant distress and regulatory behaviors vary as a function of attachment security regardless of emotion context and maternal involvement. Infancy, 17, 455–478. 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00099.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Leve LD, Harold GT, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ge X, & Reiss D. (2011). Trajectories of parenting and child negative emotionality during infancy and toddlerhood: A longitudinal analysis. Child Development, 82, 1661–1675. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01639.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangold International. (2011). INTERACT 9 [Computer software]. Arnstorf, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. & Asparouhov T. (2003). Modeling interactions between latent and observed continuous variables using maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus. [Unpublished webnotes] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund BD, Vlisides-Henry RD, Crowell SE, Raby KL, Terrell S, Brown MA, Tinajero R, Shakiba N, Monk C, Shakib JH, Buchi KF, & Conradt E. (2019). Intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation: Part II. Developmental origins of newborn neurobehavior. Developmental Psychopathology, 31, 833–846. https://doi.org/10.1017?S0954579419000440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli-Pott U, Haverkock A, Pott W, & Beckmann D. (2007). Negative emotionality, attachment quality, and behavior problems in early childhood. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28, 39–53. 10.1002/imhj.20121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulussen-Hoogeboom MC, Stams GJJM, Hermanns JMA, & Peetsma TTD (2007). Child negative emotionality and parenting from infancy to preschool: A meta-analytic review. Developmental Psychology, 43, 438–453. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, & Hastings P. (2018). Emotion development from an experimental and individual differences lens. In Wixted JT (Ed.), Steven’s Handbook of Experimental Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience. 10.1002/9781119170174.epcn409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry NB, Dollar JM, Calkins SD, Keane SP, & Shanahan L. (2018). Childhood self-regulation as a mechanism through which early overcontrolling parenting is associated with adjustment in preadolescence. Developmental Psychology, 54, 1542–1554. 10.1037/dev0000536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry NB, Mackler JS, Calkins SD, & Keane SP (2014). A transactional analysis of the relation between maternal sensitivity and child vagal regulation. Developmental Psychology, 50, 784–793. 10.1037/a0033819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Gartstein MA, & Rothbart MK (2006). Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: The Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behavior & Development, 29, 386–401. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Rothbart MK, & Gartstein MA (2008). Homotypic and heterotypic continuity of fine-grained temperament during infancy, toddlerhood, and early childhood. Infant and Child Development, 17, 387–405. 10.1002/ICD.582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Helbig AL, Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK, & Leerkes E. (2014). Development and assessment of Short and Very Short Forms of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire–Revised. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96, 445–458. 10.1080/00223891.2013.841171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, & Bates JE (2006). Temperament. In Damon W, Lerner R, & Eisenberg N. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, Sixth edition: Social, emotional, and personality development (Vol. 3). 99–106. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. (2009). The transactional model. In Sameroff A. (Ed.), The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. (pp. 3–21). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/11877-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Neppl TK, Ontai LL, & Conger RD (2008). Consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage across three generations: Parenting behavior and child externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 725–733. 10.1037/a0013190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter C, & Dollar J. (2016). Temperament and developmental psychopathology. In Cicchetti D. (Ed.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, resilience, and intervention., Vol. 4, 3rd ed. (pp. 546–607). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 10.1002/9781119125556.devpsy411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trifu S, Vladuit A, & Popescu A. (2019). The neuroendocrinological aspects of pregnancy and postpartum depression. Actualities in Medicine, 3, 410–415. 10.4183/acb.2019.410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usami S. (2021). On the difference between general cross-lagged panel model and random-intercept cross-lagged panel model: Interpretation of cross-lagged parameters and model choice. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28, 331–344. 10.1080/10705511.2020.1821690 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Usami S, Murayama K, & Hamaker EL (2019). A unified framework of longitudinal models to examine reciprocal relations. Psychological Methods, 24, 637–657. https://doi.org/10/1037/met0000210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Akker AL, Deković M. Asscher J, & Prinzie P. (2014). Mean-level personality development across childhood and adolescence: A temporary defiance of the maturity principle and bidirectional associations with parenting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107, 736–750. 10.1037/a0037248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bloom DC, & Hoeksma JB (1994). The effect of infant irritability on mother-infant interaction: A growth-curve analysis. Developmental Psychology, 30, 581–590. 10.1037/0012-1649.30.4.581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verhage ML, Oosterman M, & Schuengel C. (2015). The linkage between infant negative temperament and parenting self-efficacy: The role of resilience against negative performance feedback. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33, 506–518. 10.1111/bjdp.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittig SMO, & Rodriguez CM (2019). Emerging behavior problems: Bidirectional relations between maternal and paternal parenting styles with infant temperament. Developmental Psychology, 55, 1199–1210. 10.1037/dev0000707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woldarsky V, Urzúa C, Farkas C, & Vallotton CD (2019). Differences in Chilean and USA mothers’ sensitivity considering child gender and temperament. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1937–1947. 10.1007/s10826-019-01419-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, McKay A, & Webb HJ (2019). The food-related parenting context: Associations with parent mindfulness and children’s temperament. Mindfulness, 10, 2415–2428. 10.1007/s12671-019-01219-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]