Abstract

The circularity of plastic packaging waste (PPW) material via recycling is critical to its circular economy towards sustainability and carbon neutrality of society. The multi-stakeholders and complex waste recycling loop of Rayong Province, Thailand, is herein analysed using an actor-network theory to identify key actors, roles, and responsibilities in the recycling scheme. The results depict the relative function of three-actor networks, namely policy, economy, and societal networks, which play different roles in PPW handling from its generation through various separations from municipal solid wastes to recycling. The policy network comprises mainly national authorities and committees responsible for targeting and policymaking for local implementation, while economic networks are formal and informal actors acting for PPW collection with a recycling contribution of 11.3–64.1%. A societal network supports this collaboration for knowledge, technology, or funds. Two waste recycling models are classified as community-based and municipality-based management, which functions differently by coverage areas, capabilities, and process efficiency. The economic reliability of each informal sorting activity is a crucial factor for sustainability, while empowering people in environmental awareness and sorting ability at the household level is also essential, as well as law enforcement that is effective in the long-term circularity of the PPW economy.

Keywords: Actor-network analysis, Circularity, Closed-loop recycling, Plastic packaging waste, Plastic waste management

Introduction

Plastic waste is a particular concern as a globalised crisis due to its severe contamination of the environment and food chain, particularly the marine ecosystem, which harms human health [1, 2]. Since it was first introduced in the 1950s, the use of plastic has increased continuously. Plastic resin and fibre production rose from 2.0 million tonnes initially to 380 million tonnes in 2015 and is estimated to be 12 billion tonnes in 2050 [3]. The main application of plastic is for packaging materials, which accounted for 36.0% of total production in 2017 [3, 4]. This linearly consumed or single-used plastic ends up mainly in dumpsites and landfills or is eventually released into the environment, which accounts for almost 79% of the generated plastic waste, and 12% is incinerated, while only 9.0% of these plastics are recycled [5, 6]. Single-use plastic causes a majority loss of economic and financial value of 80–120 billion USD from approximately 95% of the material produced, a wasted opportunity in returning benefits from quality recycling [7, 8]. A circular economy (CE) of plastic materials is crucial to solving this issue. This CE effectively supports an efficient economy and reduces the negative impact of plastic packaging waste (PPW) pollution, which will double production in 2035 and quadruple in 2050, regulated mainly by economic growth and population expansion [7–9]. Such policies and regulations concerning CE are regularly implemented worldwide, especially in European countries and Japan [8–11]. Table 1 summarises the examples of CE applications to use plastic material maximally [10, 12–15].

Table 1.

The application of a circular economy to plastic packaging waste management

| Source | Policy approach | Action goals |

|---|---|---|

| EU, 2018 [10, 12] | EU strategy for plastics in the circular economy (2018) |

• Recycle about 55% of packaging plastic in 2030 • Recycle at least 65% of municipal solid waste in 2035 |

| The European green deal, 2020 [12] |

Circular economy action plan (2018) |

• Promote product reuse, repair, refurbishing, and recycling and set recycled content targets and packaging waste reduction targets • Apply new legal measures on reuse material, replacing the single-use packaging material |

| Japan, 2019 [13] | Japan’s resource circulation policy for plastics (2019) |

• Reduce one-way plastic emissions by 25% as an accumulated value in 2030 • Complete design for plastic packaging and containers recyclable and reusable by 2025 • Target at a recycling ratio of 60% of plastic packaging in 2030 • Target to double the use of recycled plastic by 2030, with following policies for consumer, municipalities, and businesses sector’s roles in sorting through waste and collecting classified waste |

| German, 2021 [12] | The EU single-use plastics directive in Germany (2021) |

• Reduce plastic consumption by reuse policy • Promote the use of reusable plastic material |

| Thailand, 2018 [14, 15] |

Thailand's roadmap on plastic waste management (2018–2030) |

• Reduce and replace some single-use plastic using environmentally friendly products (cap seal, oxo, microbead, foam food container, plastic bags, and cups thicker than 100 µm) • Promote a circular economy for 100% recycling of 7 types of plastic packaging wastes in 2030 (plastic bags, monolayer film, bottles, caps, cups, food containers, and cutlery) |

Waste recycling—a part of a CE where resources are used and reused in a closed loop—is the critical step towards a carbon-neutral society. Promoting the CE for handling PPW contributes significantly to the target of a carbon-neutral society in various contexts, mainly by reducing GHG emissions and lowering the need for new plastic resin production [4, 12, 16]. This action consequently reduces the amount of plastic waste in landfill and conserves resource consumption [16]. Furthermore, recycling plastic waste requires less energy than producing new material regarding raw material conservation and carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning [4]. The application of CE in reducing emissions has been successfully implemented [4]; for example, recycling plastic waste in China could mitigate about 14.57 M tCO2eq in 2016 [16]. Promoting closed-loop recycling and increasing the plastic waste collection rate have been reported to enhance benefits in both economic proportion and environmental reduction of GHG [4, 7, 16]. Like other countries, Thailand promotes plastic waste recycling as one of the strategies to achieve Thailand’s Nationally Determined Contribution (TNDC) of becoming a carbon-neutral society and targets to reduce about 2.0 M tCO2eq from waste management in 2050 [17].

Plastic pollution is becoming a national problem in Thailand, which generates approximately 2 million tonnes of plastic waste, mainly PPW, i.e. bottles, bags, films, cups, and food containers [18]. Through the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MNRE), the country launched the Roadmap on Plastic Waste Management for 2018–2030 to solve the problem by promoting the CE of PPW and banning single-use ones [14, 15]. Various procedures are implemented to treat and dispose of plastic waste in different proportions, most recently landfill for 62%, recycling 19%, incineration 9%, and refuse-derived fuel (RDF) production 7%. However, it was still far from the nation’s goal of completely reducing and recycling PPW by 2027 [15]. Thus, about 3.0% of plastic waste still leaks into the environment annually [15]. The local community played a sectoral role in driving the CE in waste management, which is, however, dependent on several factors, i.e. local actors, activities, regions, and cultures [18, 19]. Some national and local plastic waste management system constraints, such as multi-stakeholder involvement, management strategy, and an unclear role and responsibility, prohibit its efficient recycling [14].

To handle and manage plastic waste effectively, the correct information and understanding of the role and responsibility of crucial actors influencing recycling activity are critiqued and helpful in deciding or implementing policy [20]. However, waste recycling is a relatively technical and societal issue. There is no specific protocol, but only a practical procedure for planning and implementing locally, due to the large variety of community types, resource capacities, and needs. To gain an informative action plan, a stakeholder analysis is an effective tool for gathering knowledge and information that helps to understand the interaction and gaps for improvement in the correct driven solution [21]. The effectiveness of a local waste recycling and management programme is influenced by key players such as community leaders, organisations, local authorities, private sector, and institutions [21, 22]. This analysis is essential for initial implementation before other coordinated efforts to manage plastic waste in the local community. Therefore, this study aims to provide a holistic picture of an analysis of the actor network that influenced PPW management and recycling in the pilot area of Rayong Province, an excellent candidate for its rapid urbanisation with new industrialisation and facilities for the centralisation treatment plant to handle about 0.36 million tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) consisting of nearly 30% of PPW. The study would demonstrate some novelty in deeply analysing the actor network and the critical actor’s role of involved stakeholders and using that porosity to enhance the circularity of PPW. The qualitative and quantitative data from primary and secondary sources are linked to the actual relationships among actors and the model of PPW management in the represented communities. Lastly, the implication strategy for driving the sustainability of PPW through CE is proposed using the informative data gained and developing strategies for combating plastic pollution that fit local conditions and advocation solutions. The findings would also benefit other localities that could instantly learn from its demonstration of how to gather formative information and conduction of analysis to improve sustainability and reach carbon-neutrality targets.

Methodology

Site description

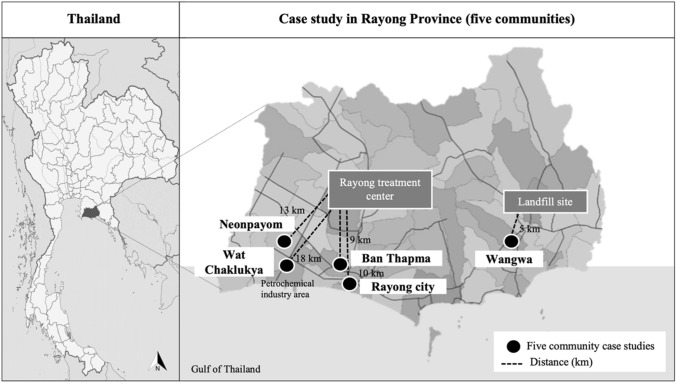

This study selected five characterised communities in Rayong Province as pilot areas named Wangwa, Noenpayom, Watchaklukya, Ban Thapma, and Rayong City. They are diversified developed communities linked to entirely operated facilities and recycling networks differently. Figure 1 shows the map of Rayong Province and the pilot communities. Rayong Province is located in the East of Thailand and is divided into eight districts, fifty-eight sub-districts, and three hundred and eighty-eight villages. The primary land use in Rayong Province balances the previous occupation in agriculture and the new location of industrial factories. This research focuses on PPW management and its sorting out from the MSW of each community, which is different in size, characteristics, facilities, and management practices. Wangwa is a small community, Noenpayom, Watchaklukya and Ban Thapma are medium and Rayong City municipality is large. These communities represent a common characteristic of the local community in Rayong Province and other provinces, which are then classified differently by the level of practice in PPW management that can link to closed-loop recycling. Good waste management practices mainly consist of waste separation and collection systems, which can be operated by community members, generally for small area coverage, whereas in medium- and large-scale communities of Ban Thapma and Rayong City, many households are covered. Local city municipalities must handle enormous amounts of waste for collection and disposal. In Table 2, the primary characters of pilot communities are summarised.

Fig. 1.

Map of Rayong Province depicting the studied communities

Table 2.

Basic information of the surveyed communities in Rayong Province

| Information | Pilot communities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wangwa | Wat Chaklukya | Noenpayom | Ban Thapma | Rayong City | |

| Located areas | Muang Klang sub-district municipality | Maptaphut Town municipality | Maptaphut Town municipality | Thapma sub-district municipality | Rayong City municipality |

| Land use |

Resident Commerce |

Resident Agriculture Industry |

Resident Agriculture Industry |

Resident Commerce Institution |

Resident Commerce Agriculture Institution |

|

Coverage area, km2 (Studied area km2) |

0.8 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 17.0 |

| Households (× 1000) | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 37.8 |

|

Populations (× 1000): estimated(1) : Registered |

2.3 1.2 |

8.0 2.1 |

10.6 1.9 |

6.2 3.8 |

162.1 62.1 |

| Main occupation |

Employee Merchant |

Employee Farmer |

Employee Farmer |

Employee Merchant |

Employee Merchant Fisherman |

|

MSW generation (× 1000 tonne/year) |

0.1 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 32.0 |

| PPW (× 1000 tonnes/year) | 0.02 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 5.0 |

| Defined cases (scale) | Small | Medium | Medium | Medium | Large |

(1) Included latent population

PPW plastic packaging waste

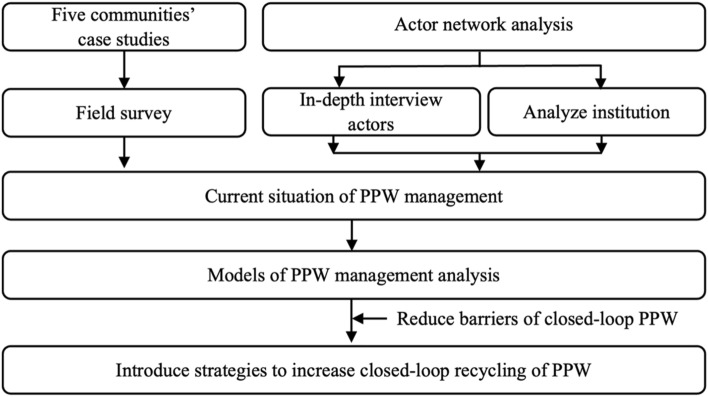

Data collection and framework

The method for data gathering applied in this study, during 2021–2022, consists of a literature survey, a community site visit for the primary physical information survey, a resident’s condition, and an informative interview. An in-depth interview was then applied for selected actors in the recycling value chain using semi-structured questions to narrow the identification of actors and relevant stakeholders. The conceptual framework was developed based on systematic thinking to gather each actor’s perception, opinion, and implementation of PPW management at the national and local levels. The collected data was discussed by categorizing similar results into similar relationships, summarising, and interpreting. In Fig. 2, the studied framework is depicted.

Fig. 2.

A studied framework of plastic packaging waste management in local communities

Secondary data survey

The secondary information concerning local recycling and waste management was revealed. The PPW and communities’ knowledge, facilities and waste handling strategy were studied. The data focus was the reports, articles, and public information screened and analysed for relevance and update. This basic information was comparable to the surveyed information when visiting the communities.

Site visit and community field survey

To understand waste and PPW management in practice, the communities and recycling facility plants were visited intensively. The community and household survey aimed to gather a holistic picture of plastic waste management in the selected areas. The visit was also aimed at participating community members or residents for data interviewing. Using multistage and stratified criteria, five communities were selected based on prevalent factors such as community type, readiness, facility, recycling ability, and activity and stage of recycling development. A visiting place is also a focus of the survey, which currently focuses on the PPW management system in each local community, unit, functions, and types of plastic waste (i.e. bottles, bags, films, and containers) generated. The amount of PPW generated, existing PPW management practices, and activities for collecting and recycling schemes were also mentioned.

Stakeholders’ in-depth interviews

This study selected 42 actors in the PPW management system based on their case knowledge and level of involvement, ranging from policymakers to producers, users, recyclers, and waste handlers. In-depth interviews were implemented to analyse the role and responsibility of all critical actors in the stakeholder’s network involved in recycling PPW. These actors functioned initially in driving policy at the national level to sorting and collecting duty in local implementation through the whole action loop of recycling in the pilot communities of Rayong Province—the selected vital actor, as listed in Table 3. An in-depth interview was conducted to obtain expertise from informants with knowledge and experience of the case [23]. The in-depth interviews were digitally recorded and complemented by written notes. The interviews lasted 30–90 min and were mainly on-site during the stakeholder’s visit, but some were online during the COVID-19 pandemic. The interviews were subjected to the thematic scope for analysing and identifying the similarities and differences of qualitative answering. The relationships of each actor or among the working network of the PPW recycling loop were also mentioned. A similar implementation was msde by Kongshøj Wilson [24], who applied a stakeholder analysis procedure to this type of interview by performing some tasks of selection, interview preparation, information gathering from informants and surrounding environment, and participating in data analysis. This technique is an effective tool for systematic and in-depth data gathering for global, national, and local prospects that are complicated and far from primary consideration on the questionnaire basis. For national and local informants, the in-depth interview was organised for 42 actors or stakeholders of plastic management chains. The open-ended questions were constructed and conveyed primarily to gather information, opinion, and attitude guides from key informants about how the PPW management system works in local communities. Their functions and roles, barriers and problems of the current situation, internal and external critical success factors, knowledge and understanding of PPW management, and recommendations were also mentioned by asking some questions concerning the issues below.

Current status of PPW management: strategy and policy.

Internal and external success factors of PPW management.

Problem situation, barrier faced, and suggestions for resolving.

Knowledge and understanding of closed-loop recycling, CE, and EPR for PPW recycling.

Plans and recommendations in establishing closed-loop recycling for circulating plastic waste material.

Table 3.

Key actors and networks of plastic waste recycling at the local level: a case study of Rayong Province, Thailand

| Networks | Key informants | Number of organisations |

|---|---|---|

| Policy |

National and central organisation: Pollution Control Department (PCD) |

1 |

|

Provincial Organization Administration: PNRE, Rayong provincial office for local administrative |

3 | |

|

Local organisation administration and municipality: Maptaphut municipality, Cheongnoen sub-district municipality, Namkhok sub-district municipality, Rayong City municipality, Thapma sub-district municipality, and Muangklang municipality |

6 | |

| Economic | Plastic recycling plants | 3 |

| Plastic remanufacturer/converter | 1 | |

| Waste recyclers/junk shops | 5 | |

| Waste collectors/pickers | 6 | |

| Consumer goods companies | 2 | |

| Waste bank operators | 2 | |

| Retails in community | 5 | |

| Institute: Environmental Research Institute | 1 | |

| Societal | Local communities (leaders): Wat Chaklukya community, Noenpayom community, Rayong City community, Ban Thapma community, and Wangwa community | 5 |

| School: Wat Lum Mahachai Chumpon Municipal School | 1 | |

| NGOs (PPP Plastics; Public Private Partnership for Sustainable Plastic and Waste Management) | 1 |

Data analysis

The obtained data and information were analysed in a specific direction focused on an actor-network investigation to identify the person, role, and responsibility with regard to PPW recycling. The practical management model that acts in the surveyed communities was also mentioned and a suggestion proposed for the circularity of plastic waste economy promotion at the end. The details of each discussion are stated as follows:

Actor-network analysis

The critical analysis of actor networking, role and responsibility, and barriers to circularity management were discussed. Actor-network analysis is a tool for identifying the actual direction of actors involved in central and local government and community action with the same objection and issue, herein, PPW management [25]. To manage PPW effectively, the vital role of key actors, which is the main factor influencing each network, is an essential and emerging information. Because multiple actors and stakeholders are involved in plastic waste management, their different key roles influence successful management. To investigate stakeholder relationships, this actor-network analysis is similar to stakeholder network analysis that focuses on identifying the significant role of each actor in acting on PPW handling, sorting, collecting, transporting, and recycling and treatment process. The relationships are compared within and between individuals, groups, and systems to analyse the situation of communities-based management. This procedure developed an actor-network graph for visualising the linkage between the actors [23]. These actors were then divided into three groups of networks being interviewed: the policy network for 10 in-depth interviews, the economic network for 25 in-depth interviews, and the societal network for 7 in-depth interviews (Table 3).

PPW management model

Managing plastic waste in various local communities is critical [26]. The analysis focused on communities’ currently used strategies, here called a model, to organise their plastic waste mechanisms that effectively drive PPW flow from its source to the following scheme of sorting, collection, transferring, and reprocessing in a recycling plant. It was found that there were two practical management models often used in different areas.

Circularity strategy propose

This section discusses the possibility of improving the strategy to achieve sustainability via CE in plastic material. The CE of waste material has been proven and used to analyse sustainability and a solution for waste management in previous works [4, 7, 16]. In this study, to explore the sustainability of PPW management, the CE strategy suitable for local capability and conditions and practical to widely applied was proposed. The technical policy, technology needs, and societal support must be implemented entirely in short-, medium-, and long-term periods.

Results and discussion

Waste and plastic waste management at the local level

Plastic waste management at the local level, including PPW, was directly related to MSW collection and treatment, depending on how the provincial and local governments operated [26]. There was no specific law, regulation, or treatment condition practically operated for PPW. Various factors related to this difference including the local capability in human resources, finances, and final treatment options, which consequently influenced a regular protocol for managing MSW [27, 28]. For the legal policy, the Thai national government regulates all local municipalities and administrative organisations to handle waste collection and treatment [28]. This legal duty is of the local authorities’ officers under the Maintenance of Public Sanitary and Order Act, B.E. 2535 and cleanliness and tidiness of the country Act, 2535. It was found that this option was effective when a completed installation of treatment and collection facilities was installed, which was found only in the large and wealthy city municipalities or districts with sufficient income or regular budget earned from the industrialised factories as in Rayong Province. However, the distribution of financial proposition depends on the population density and contribution to activities; thus, the coverage area ability and management efficiency of solid waste subsequently differ from district to district [29].

Rayong Province handles about 0.36 million tonnes of MSW annually, which contains approximately 30% of PPW, or about 0.11 million tonnes of plastic waste generation per year [18]. This number varied significantly by district and community ranging around 9.3–29.0% of PPW in MSW. The PPW management at the local level in Rayong Province was involved with multiple stakeholders, including the formal and informal sectors. In practice, high-value plastic waste materials were separated and collected by the informal section of communities, pickers, or waste collection crews to sell to waste junk shops and recycling plants. In plastic waste management, one of Rayong Province’s strengths was the location of its recycling plants. However, there was still a significant amount of unmanaged PPW in MSW under the responsibility of local governments. Rayong Provincial government facilitated the centralised facilities: an RDF plant for combustible waste and a landfill site for incombustible and non-recyclable waste materials. These facilities are operated by contracted private companies charging a fee for treatment from local municipalities and administration organisations. Therefore, increasing the recycling rate can directly reduce plastic pollution and operation costs from waste disposal.

Plastic packaging waste management practices in the selected communities

The high price of saleable plastic was initially separated from other waste at the generation source or households and commercial sectors. These plastics included bottles, bags, films, cups, and other food containers. Such valuable PPW was sold to the formal sector (municipalities, waste collection crews, recyclers, and junk shop owners) and the informal sector (waste pickers and collectors). However, non-valuable and contaminated PPW was dumped as MSW. Each local community sets up activities encouraging people to sort and collect PPW for recycling, such as community waste banks, waste-exchange campaigns, and plastic drop points. This organised event is regularly held by the local authority or a community member once or twice a month to deposit or collect PPW using a bank-like procedure. The benefits, such as the points in the accounts to exchange consumer goods or profits, were incentives to motivate people. The waste-exchange event is sometimes organised by temple, where private companies, retail stores, and households donate their valuable PPW to the temple. This waste-to-merit strategy is an attractive option in many urbanisation areas, i.e. Rayong City municipality and Thapma sub-district municipality.

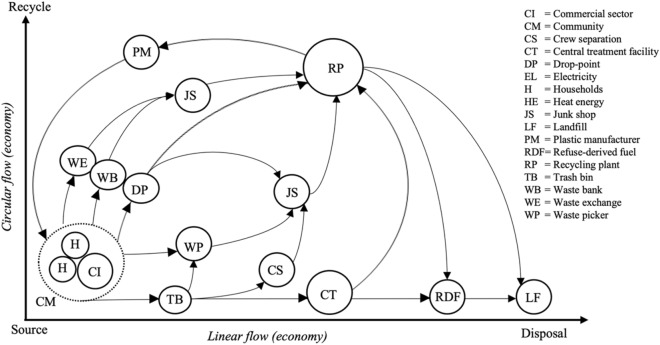

Meanwhile, the informal sectors were crucial in managing a large volume of unsorted PPW in communities. Households may sell their plastic to waste pickers, who pick up the valuable waste from the trash bin. Some mixed wastes were disposed of without sorting into the trash bin and covered by the curbside collection, which is not a regular practice. This composite plastic will be separated by crew separation or workers hired by the local government who work with collection trucks, mainly for high-value materials. These collected plastic wastes are then sold to the junk shop and recycling plants for processing as recycled plastic material for new product production. Figure 3 shows PPW management in linear flow and CE approach. It was found that the circular loop economy of selected communities can recover about 11.3–64.1% of PPW back to the recycling process. The rest of these plastic wastes are separated at treatment centres turning combustible waste into energy, and the residues are disposed of in a landfill, which is not practical in all municipalities.

Fig. 3.

Plastic recycling and waste management loop at the local level

Regarding the circularity of plastic waste material, it was found that surveyed communities have a similar strategy to management, but different units involved in collecting and separating plastic waste from MSW, transferring it, and selling it to junk shops. This pattern is typical in a small community like Wangwa. The circularity of the separated PPW material is possible by selling it to a junk shop, which connects to the recycling plant in the recycle loop. Moreover, in urban areas like Noenpayom, Watchaklukya, Ban Thapma, and Rayong City, a recycling network is automatically connected as they are a part of the centralised treatment facility network through energy recovery and final disposal for handling enormous wastes daily. This practical management procedure is also found in other provinces, such as Phuket [30], Nonthaburi [31], or a central city of South Korea [4], where the centralised facility has operated as a part of waste management. Promoting recycling activity and the sorting facility could promote more circularity of PPW material. However, a complicated network of actors or stakeholders influenced the actions and efficacy of its recycling.

Almost all plastics are technically recyclable, but many plastics are not practical to recycle. Many factors related to social–behavioural, economic purchasing price, and technical knowledge are integrated obstacles to the recycling activity of plastics recycling schemes. It was found that economic returns from selling plastic waste could encourage significant recycling activity in households and at a community level. According to the results of five community case studies, mixed plastic, mainly food containers and plastic bags made of polypropylene (PP), high-density polyethene (HDPE), and polyethene (PET), accounted for 65.6% of the plastic sold to junk shops and recycling plants. In practice, each junk shop buys a different type of PPW, which depends on the plastic’s cleanliness and saleable price to the recycling plant. It was observed that plastics with high purchasing prices, such as PET bottles, were separated early in the household; thus, less contamination was found in later steps.

Actor-network analysis

Network composition

Network analysis goes beyond stakeholders. A network herein is a formal and informal working group to work in a similar direction with and without any collaboration of individual actors to manage or do those activities related to plastic waste management, such as collecting and recycling. This definition is also included to accomplish a similar target, mainly plastic waste recycling and management. A network comprises many actors or stakeholders. In each network, different units and persons punctually respond to promoting activities. Figure 4 shows the actor network in PPW management, including policy, economic, and societal in Rayong Province.

Fig. 4.

A relative network of actors functioning for plastic waste collection and recycling

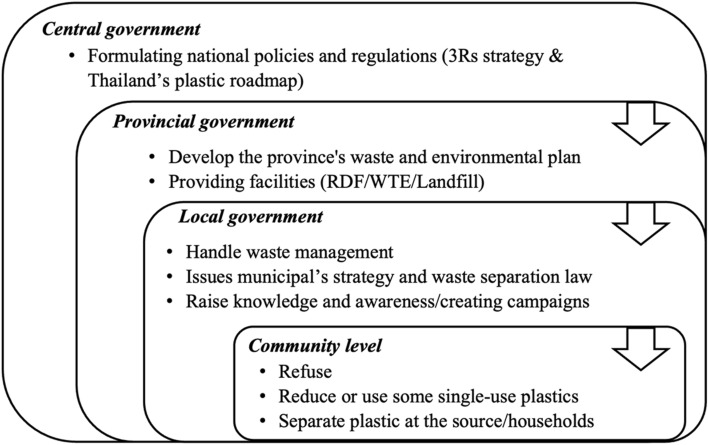

Policy network

It was found that the policy on plastic waste management was driven by government organisations from the national to the local level or policy network, as shown in Fig. 5. The two central ministries with official duties enforced by laws are the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MNRE) and the Ministry of Interior (MOI). From central to local organisations, a clear target, focus area, and practical action plan are responsible for this policymaker group. The central government had established policies to promote national targets in plastic management. Thailand’s roadmap on plastic waste management 2018–2030, has been launched. This policy framework is organised by the Pollution Control Department (PCD) under MNRE to drive the CE and initiate action to ban using four types of plastic products: foam food containers, plastic straws, plastic bags thicker less than thirty-six microns and single-use plastic cups. However, a multi- and cross-section organisation involving various government agencies, stakeholders, and experts is sometimes a critical barrier to implementing and completing a direction.

Fig. 5.

Roles and functions of key actors in the policy network

For local governors, 3Rs (reduce, reuse and recycle) were an essential strategy for managing MSW and PPW. Local government, district municipalities and administrative organisations also play an essential role as middle organisations receiving central policy to action provincially and locally communicate to the community for the implementation of waste collection, handling, and disposal. Some municipalities established local regulations and policies; for example, Rayong City established the 3Rs policy on facilities for MSW collection and disposal services. Plastic drop-off points and other facilities have been provided for twenty-nine villages in their coverage area for monthly routine collection to promote PPW for recycling. Although the authorities in Rayong Province knew that reducing and reusing were better ways to manage PPW, only a few participated in campaigns for short periods, and their behaviour did not change. Moreover, many measures initiate their recycling activities voluntarily, which initially benefit from gaining some attraction but have a less long-term impact due to the lack of enforcement ability. All these limitations were key challenges to the sustainability of policy implementation and needed effective revision in their target and implementation protocol.

The results of actor-network roles and analysis of the policy network found that the challenges to the sustainability of policy implementation needed effective revision in their target and implementation protocol, including a clear direction and regulated packaging separation and collection for recycling, which must be promoted to deal with PPW at the source. National and provincial authorities believed that promoting extended producer responsibility (EPR) was critical for driving the CE in PPW. Aside from promoting recycling, it assists local governments in reducing the cost of management that would otherwise be spent on hiring public waste collection companies and treatment, which cost around 37 dollars per tonne of PPW according to the municipal waste collection and treatment fees in Rayong Province (2021). It required brand owners and waste generators to act more because various non-recyclable PPW types are still technically challenging to manage, such as PVC films, multi-layer films, and foam food containers (Fig. 5).

Economic network

An economic network is defined as a group of actors linked along the value chain of plastic packaging through production, distribution, collection, processing of new products, and disposal. The network comprises specifically plastic providers, i.e. resin factory owners, plastic converters, brand owners, retailers, and plastic waste collectors, i.e. waste pickers, waste collectors, junk shop owners, and recycling plant owners or recyclers. In this study, the institutional or university researchers were also a part of this group, as they provided technical information or knowledge of PPW recycling to local communities with government and international organisation support. It was found that most post-consumer PPW in Rayong Province, like in other cities in Thailand, was currently managed through a recycling market or economic recycling loop that involves both formal and informal sectors. Both players were involved in each step of PPW separating and collecting at households; waste bank recycling; waste exchange; plastic drop points; waste pickers; ‘crews’ separation, and selling to junk shops and recycling plants, driven by economic incentives. Particularly in Rayong Province, there were plastic recyclers for recycling various types of plastic waste that had the potential to close the loop on PPW, including high-volume PPW such as plastic bags and films made from polypropylene (PP), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), and low-density polyethylene (LDPE).

PPW was separated for recycling varied by community and municipality implementation capacities, with the highest rate in Wangwa community at about 64.1%, and only 11.3–18.1% in other communities. PPW was separated as clean raw material at source or household level through the community’s voluntary activities at 48.6% in Wangwa and 1.4–3.8% in others. Moreover, mixed PPW was contributed by waste pickers, known locally as “Sa-leng,” who collected an estimated 2.1–15.5% of total PPW from fifty waste pickers in Rayong City municipality areas. The crew’s separation recovered about 4.7–9.0% for the formal curbside daily collection by the municipality’s services. The collection truck’s crews informally separate the separated day-to-day waste to the junk shop. From the results of five community case studies, it accounted for roughly 11.3–64.1% of the capacity of PPW collection as raw material for recycling. At the same time, the remaining PPW is sent to the central treatment facility, where the separation is based on its utilisation for combustion material and disposed of entirely in the constructed landfill.

The limited PPW separation and collection at the source was one of the recycling system’s significant factors. However, it struggled with the PPW recycling system’s technical plastic separation and collection limitations. Local recyclers stated that the PPW collected from communities lacked the complexity of plastic types, grades, colours, and low consistency volume, directly affecting the recycled resins’ quality. In addition, the market price of separated recyclable PPW depended on its quality; if communities could separate them into high quality and quantity, it would result in higher selling prices and enable them to deal with recyclers for direct collection at the community’s centre. It still needed to consider improved techniques and operational costs, such as long-distance transportation, workers, and storage areas. Local recycling loop actors also required technical assistance to improve management, such as plastic waste compactors and cleaning and drying machines.

The economic feasibility of each recycling project also strengthens the sustainability promotion of PPW recycled, which could promote the CE of PPW material. This economic network contributed significantly by 2.8–56.8% of residents in selected communities, which means the suitability for each local condition. In these actor communities, junk shops were significant units receiving all PPW for recycling. Local junk shops were registered with authority organisations to follow limited operating regulations. It was observed clearly that, in the economic actor network, there was less contribution from the plastic provider’s sector, i.e. resin producer, converter, consumer goods company, retailer, and recyclers. The only participation was from a recycler, who buys PPW for reprocessing but with varying prices and limited purchasing conditions. An enhanced contribution of other actors, mainly consumer goods companies, is now a concern worldwide. EPR is a relatively new concept for communities, which was initially implemented voluntarily in a pilot case study in Chonburi Province. However, this concept was initially evaluated, and no implementation was found in Rayong areas. Table 4 shows some formal and informal critical actors in Rayong’s economic network.

Table 4.

Formal and informal actors in the economic network for plastic packaging waste separation and collection

| Separation route | Defined sector | Key activities | Key success factors |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Start: household Stop: recycling plant |

Formal(1) |

Municipal waste bank Waste-exchange event Drop points |

A part of the municipality’s policy Getting financial and resource supports Ensuring activities routine for continuity |

| Informal(2) |

Community waste bank Waste-exchange event Drop points |

A trusted community strong leader Self-motivation by directed benefits Community relationships and networking |

|

|

Start: drop point (roadside) Stop: recycling plant |

Formal(1) | Municipality waste collection service | Legal duty enforced bylaws |

| Informal(2) |

Crew separation Waste pickers |

Direct benefit from selling plastic wastes and high market price material |

(1) Initiated or operated by the local government authorities, (2) initiated or operated by actors or community members, or private company

Societal network

A supportive group of actors works socially with policy and economic networks to promote the efficiency of PPW recycling. This group is called a societal network, comprising private sector members from private companies, non-government organisations (NGOs), and local community members who mainly work for non-profit requests, such as volunteers, for campaign promotion in their local area. In Rayong Province, several societal networks had been operated previously. Several industrialised companies operate their cooperated social responsivity (CSR) activities.

The actors in this group all play an essential external role in assisting local communities with plastic waste recycling programmes by closing the gaps in the connection loop between plastic producers, recyclers, institutes, and local communities. Societal actors agreed that strengthening plastic waste management networks was critical to closing the PPW loop. However, the capacity of PPW recycling in each district depends on many factors, such as the community’s leader, people participation, and rules of waste separation. It was found that Rayong City was able to manage plastic bags and films that made up the most considerable portion of PPW in MSW at more than 100 tonnes a year, and Wangwa was able to manage PPW at more than half of the total PPW generation in the community with collaboration with external networking groups.

This strong relationship between people in the same community, district, or city is the most critical factor governing the success of plastic waste management activities such as waste banks, plastic drop points, and other activities shown by participant numbers. Most plastic waste management activities are on a voluntary basis. Besides that, societal actors agreed that clear communication about managing PPW in their community was critical; if they knew how to sort and send it to facilities near their households, it would be easier for them to participate in the programme. Moreover, the intense collaboration with external organisations is supported by societal networking, such as private companies, institutes, and community volunteering. It was one of the keys to promoting plastic recycling, reducing, and reusing by providing knowledge, technologies, or funds, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Societal contribution and support for plastic packaging waste management in the selected communities

| Contribution and supports | Pilot areas | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wangwa | Wat Chaklukya | Noenpayom | Ban Thapma | Rayong City | |

| Community’s plastic collection activities |

Sorting Collecting Reproducing |

Sorting Collecting |

Sorting Collecting |

Sorting Collecting |

Sorting Collecting |

| Place | Community hall |

Community hall Temple |

Community hall Temple |

Community hall Temple |

Community hall City recycling hub |

| % of residents participating in plastic collection activities | 56.80% | 38.56% | 14.06% | 3.20% | 2.84% |

| Financial support (sorting) | Self-investment | Self-investment | Self-investment | Municipality | Municipality |

| Technology support |

Academic institutes Private sectors NGOs |

Private sectors NGOs |

Private sectors NGOs |

Academic institutes Private sectors NGOs |

Academic institutes Private sectors NGOs |

Several initiatives have been reported to impact improving the waste separation performance of the surrounding community. Furthermore, awareness raising and knowledge sharing of success among communities may assist other local communities in developing sustainable PPW management. Cities or municipalities are trying to raise environmental awareness in communities and schools. A young school student is one part of the community that strongly influenced to increase parents’ and communities’ waste sorting ability and knowledge transfer. In Rayong Province, some schools run a zero-waste programme by promoting the 3Rs concept in lessons, policies, and student involvement activities.

Network interactions

By analysing the networking of actor stakeholders in each working group, it was found that each actor was significantly and relatively in the same or between the working groups to drive PPW from source to recycle loop. Different relations were found for each network: control and command for the policy network, benefit sharing for the economic network, and linear cooperation for society herein defined as the network interaction type. In policy networking, the controls were according to legal enforcement. These responsibilities were officially used to control the direction. Central governments drive regional and provincial implementation by controlling the direction and budget. Similarly, the provincial government also directed the local municipality. Policy or governors were supportive and initiative agencies for many recycling projects. At the same time, the registry of many informal sectors of the economy to local governors was compulsory. This detection of commands was found to be less when they connected to another network.

The benefits or prices of recyclable PPW were a significant factor in the community’s decision to operate its separation and collection for PPW recycling, such as waste banks and plastic drop-off points. The benefits varied according to type, quality of PPW separation, and market price, affecting waste management’s sustainability in the long term. The separated PPW is transferred economically and price from selling at the initial point, i.e. household, waste bank, and to the recycling plant sequentially. By working in the same recycling network, an economy group is relatively working on a benefit-sharing basis. The economic network plays a significant role in motivating local communities to manage PPW for recycling, especially in the informal sector, such as waste pickers, waste collectors, waste collection crews, junk shops, and local plastic recycling plants. This economic network deals with policy by receiving technology, knowledge, and regulations launched by local authorities. The supportive direction was also found for societal networks, which eventually play a role in donating equipment, technology, and knowledge for PPW recycling. It maintains that harnessing social support, acceptability, and participation is vital to sustainable PPW management.

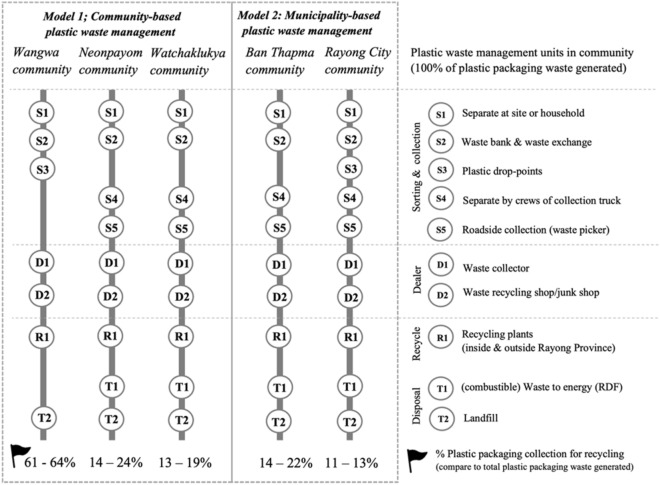

Plastic packaging waste management model

The PPW management model analysis in five community case studies showed two basis types at local communities: community-based self-management and municipality-based centralised-management models. Community-based self-management was observed to have a higher recycling rate than municipality-centralised-based management. However, these two types of activities are essential to recycling and function relatively to close the loop of the Rayong recycle scheme. Figure 6 depicts PPW management conceptual models found in Rayong Province.

Fig. 6.

Plastic packaging waste separation and management models

Community-based self-management model

The ‘Community’ working group played a crucial role in the informal sector and set up a community system for communication and income distribution to the residents using profit from selling recycled PPW. The community’s members manage and handle their waste by establishing a working group for collecting, sorting, and transferring recyclable waste in the community to junk shops or recycling plants, mainly implemented at the village level as case studies in Wangwa, Wat Chaklukya and Neonpayom communities.

The local communities established the zero-waste programme to solve the community’s waste crisis by encouraging households to sort their waste at the source into four categories: recycling and plastic waste, organic waste, hazardous waste, and general waste. All types of waste have sorting, collection, and application systems such as a learning centre, waste management at source, waste bank, and plastic drop points. As a result, Wangwa community collected plastic for around 64.1% of the total plastic generated. Such waste was sold to junk shops and recyclers. Similarly, other communities in Watchaklukya and Neonpayom operated waste banks to separate waste for recycling. Moreover, waste pickers and waste collection crews in the two communities continue to play an essential role in roadside collection, resulting in much plastic waste collection in these sectors.

Wangwa, a community self-management, is a successful model for managing PPW for recycling. Due to vital networking, good knowledge, and practice in responsible areas for managing PPW, household sorting and collection schemes are effective at the household level, with 56.8% of households involved. On the other hand, implementation costs were also barriers, such as the high cost of transporting plastic waste to recycling plants and need for more storage and operation areas. Furthermore, it found that a considerable portion of unmanaged PPW in the community case studies, both recyclable and non-recyclable, remained in MSW, ranging from 8 to 22% of five communities. It had to be managed further by the central waste management loop at the provincial level, such as by RDF power plants to be combusted and converted into electricity and disposed of in landfills.

Municipality-based centralised-management model

The municipalities are the centres of plastic waste management, which drive the policy of waste management, such as 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycling) and zero-waste programmes, i.e. in Rayong City and Ban Thapma. The local authorities encouraged people to manage plastic waste by implementing programmes and campaigns to collect at its source using event-based activities, i.e. waste banks, plastic drop-off points, and plastic waste segregation projects. The authorities were supported by local people and the private sector to sort and collect plastic waste for the recycling loop. However, managing plastic waste in urban areas is challenging by its low engagement rate, only 2.8–3.2% of households participated. Furthermore, the informal sector, such as collection crews and waste pickers, also plays an essential role in collecting plastic waste at the roadside and separating a significant amount for recycling due to the economic driving force or market demand. It was found that the quality of collected plastic waste at the roadside was poor due to contamination with other waste, which resulted in a low selling price. Lastly, MSW’s plastic waste was transported to waste treatment facilities where the RDF and landfill were applied. However, the barriers to these models appear to be low awareness of waste sorting among people and economic driving factors such as incentives and profits, which were still critical factors for managing a large amount of PPW from the city to the recycling system.

Circular economy strategy for plastic packaging waste

The CE for plastic waste was promoted to meet sustainability goals and Thailand’s Nationally Determined Contribution goals of becoming a carbon-neutral society by 2050 [32]. According to the findings of this study, the critical actors in the local plastic waste recycling chain have made numerous attempts to promote CE in waste recycling. It is helpful to national and local management if plastic material circularity is a sustainable and preferable practice for local municipalities. The analysed results of five communities found that several factors drive a community’s contribution to the closed-loop recycling of PPW. However, different barriers emerge in each community, which are influenced by forces driving people to do the recycling activity. The sustainability of these recycling communities is vital to the city’s recycling capability and governs the success of plastic waste circularity. Promoting local capability has been proven to be an efficient strategy that promotes more sustainability in the recycling project. The following promotion strategies for the CE for PPW recycling aligning to the nation’s roadmap policy in actions in short-term (2022–2023), medium-term (2024–2030), and long-term (by 2050) implementation are summarised in Table 6.

Table 6.

Practical promotion strategy for the circular economy of plastic packaging waste material

| Proposed strategies | Actions and needs |

|---|---|

| Short term (2022–2023) | Target: to increase recycling efficiency and economic feasibility of each recycling group important to recycle PPW. A mentoring system could promote more rapid development |

| • Awareness raising | • Self-awareness is best for recycling, but it takes time and continued promotion to accomplish |

| • Sort at site | • A best practice of PPW management is sorting at source or household. This action promotes a good quality of PPW from being separated early |

| • Economic incentive | • High quality of separated PPW at source (cleanliness, separation by type) influences the high selling price, recycling ability, and operation cost |

| • Extend recycle network | • The success of the informal sector or small communities’ network is an excellent example to encourage other communities to start recycling their waste |

| • Reduce the cost of operation | • Provincial and local governments should provide the facilities for PPW collection for recycling, such as plastic drop points and routine public collection trucks (separate from other waste) |

| • Technology aids recycling | • Equipment, i.e. compactor and cleaning machine, enhance efficiency and reduce the cost of operation |

| Medium term (2024–2030) | Target: to develop recycling facility platform that makes it easy for recyclers to connect the recycling loop to encourage more recycling activity and reduce the cost of operation |

| • Develop tack-back centre | • Retailers and private companies provide the facilities for collecting and returning PPW from consumers to recyclers |

| • Database development | • Normalised and correct data on the same basis is essential to policy and action implementation |

| • Sorting facility platform | • Application or online platform is helpful to promote knowledge and recycle campaign for the recycler |

| • Community engagement | • Collaboration of each community is a key to recycling that is encouraged by the clear example of success case |

| • Encouraging by incentive | • To encourage new recyclers, adding an incentive is sometimes beneficial. However, a local regulation should be considered in maintaining its long-term stable operation |

| • Economic incentive | • To increase incentive in recycled market, the government should provide financial subsidies for recyclers and promote recycled product consumption by tax reduction |

| Long term (by 2050) | Target: to develop sustainability and standard best practice for PPW recycling and circular economy |

| • Law enforcement | • Law and regulation clearly state that role and responsibility are essential to PPW management in a public city with significant stakeholders. Voluntary-based engagement is low enforcement ability in practice |

| • Promotion of EPR | • EPR is fare policy sharing the responsibility of waste with producers. A mandatory-based EPR should be developed step by step. |

| • Sharing benefits | • Sharing benefits in an economy should be directly returned to recyclers. The application of technology, such as an online platform to track PPW recycling activities and tax refunds for recycling, will encourage more active recyclers. |

| • Promote eco-friendly product | • Promoting brand owners to avoid using materials or designing products that are difficult to recycle and encouraging consumers to buy eco-friendly products with reusable, recyclable, or biodegradable packaging by reducing taxes |

| • A centralised system | • A centralised organisation is an efficient way to operate recycling waste |

| • Whole-system management | • Non-valuable, priceless and non-recyclable plastic should be considered as it is a part of management that also needs to share responsibility and whole-system strategy to handle |

MNRE Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, MOI Ministry of Interior, PCD Pollution Control Department, DLA Department of Local Administration, Rayong-PNRE Rayong Provincial Office of Natural Resources and Environment

In promoting the CE of plastic waste material and sustainability in Rayong waste recycling, various implementations are needed to fill the development gap, solve the problem, and overcome the barrier of such threats to sustainability for PPW management. Promoting laws and regulations that state a clear role and direction for each stakeholder to be responsible for waste is essential. This clear direction is also needed for market position and demand enhancement of recycled plastic, which should be a control material for processing new plastic products. Furthermore, proposing actions and needs of strategies at different levels of primary actor involvement could assist in determining their roles towards the CE and becoming a low-carbon-neutral society.

Various mechanisms of increased recycling efficiency, technology, and networking improvement are required to reduce recycling operating costs and improve its economic feasibility. The initial goal for the short term (2022–2023) is to promote such activities for recycling improvement projects focusing on local communities that can be implemented immediately and on a low budget. The medium strategy (2024–2030) is aimed differently at developing recycling quality by using the technology of online and application platforms for public participation and engagement in promotion campaigning, knowledge and news announcement, and data recording usefully. This development is essential to a recycling business that needs intensive collaboration and support from government and private agencies.

In the long-term operation (by 2050), the central government is critical in promoting laws for the source segregation of household waste, especially for PPW recycling, which is necessary for effective enforcement. The current regulations are less considerate to effect position force recycling strictly. There is no clear definition specific to PPW from other MSW, but it stipulates as an insertion in different directions presently. This situation is similar to national and local regulations, where a broad responsibility to handle waste is assigned to the local municipality while managing the budget or monetary remains in the central decision ministry unit. The extended responsibility of waste producers is also an emerging issue that needs systematic development in the future of national waste management. EPR is an environmental policy approach developed to extend the responsibility of the product’s producers or brand owners, herein plastic packaging, to recover their waste [33]. The plastic producers are expected to provide financial and operations to support recycling activities, such as appropriately handling, sorting, collecting, and recycling. Furthermore, promoting eco-friendly production and consumption requires brand owners or producers to avoid the use of difficult-to-recycle materials or design products that encourage people to use reusable, recyclable, or biodegradable packaging, which would reduce plastic waste handling to landfilling or incineration. Sharing responsibility with a whole-system strategy for circulating plastic packaging material will contribute to a carbon-neutral society.

In the case of community-based waste management, the community can self-manage plastic waste through a recycling scheme due to good practices in plastic waste management and strong collaboration with people. To close the plastic waste loop, one significant factor in driving sorting plastic activities at the household and community level is the economic returns from selling plastic waste. Furthermore, the economic feasibility of recycling activity influences its sustainability. Operating costs are a significant economic consideration, such as transporting plastic from communities to recycling plants. Thus, financial support and cost reductions through the promotion of technology, i.e. plastic waste compactors and washing machine, are needed to increase the efficiency then circularity of the material. Furthermore, building a solid relationship with local authorities and societal networks may allow communities to develop a closed-loop plastic waste area to serve as a the pilot case study for sustainability management.

In the case of city waste management, municipality-based plastic waste management is a model of PPW operated for large city municipalities. There are critical factors in social engagement, economic incentives, and environmental policy in promoting the closed-loop recycling scheme. Raising awareness and knowledge education is essential in changing people’s behaviour to be more plastic waste friendly because it is still limited to plastic waste sorting at the household level. Also, proper handling, recycling, and education for all stakeholders are essential to improve plastic waste management. A basic recycling infrastructure should be established so that households can easily collect and send their PPW to the recycling loop. The implemented technology will be less significant when applied to low-aware people to recycle their waste; it will be neglected if there is no valid regulation. Thus, ongoing promotional campaigns are essential for success in awareness raising. Improving marketed data and information or knowledge on the platform can assist in the correct separation and process efficiency. According to the findings, 11.3% and 64.1% of the PPW in the communities studied were returned to the recycling system as raw materials as a step towards a low-carbon society. It was found that the models of community-based and municipality-based plastic waste management at the local level could be helped by returning 11.2–92.5 and 34.0–572.0 tonnes of PPW for recycling, respectively. It was estimated that there were GHG reductions of 15.1–124.9 tCO2eq and 45.4–772.2 tCO2eq by reducing the use of new plastic resins (according to a UNESCAP closed-loop plastic case study in Bangkok in 2019, approximately 1.5 tCO2eq was reduced by using 1 tonne of recycled plastic material) [34].

Conclusions

The active actors in plastic waste recycling of local communities is a critical driving factor governing the success of plastic waste management and recycling. Due to a lack of direct law enforcement, such as EPR, waste and plastic waste management have been influenced by multi-stakeholders, involving both the formal and informal sectors [21, 33]. Local waste facilities’ different criteria and constraints also result in various actor network compositions that bring plastic waste from their generations to recycling schemes. The actors’ network analysis results revealed the vital groups of actors influencing PPW recycling in Rayong. This practical tool depicted proper application in identifying the complex conditions of the local municipalities. Actor-network analysis could provide a holistic perspective of the relationships between multi-stakeholders, which is essential and helps to better understand the whole value chain of plastic waste recycling. This step is necessary for activity implementation and policy development.

The strong collaboration between the three networks of actors functioned differently in the policy direction: plastic waste sorting, collecting, and recycling. These relations are essential and related to the system’s sustainability. By identifying each actor’s responsible role, this analysis determined the critical functions of closing the loop in PPW management, allowing actors to play more actions in successful project management at the local level [33]. The findings of this study show that closed-loop recycling activities in local communities, both in community-based and municipality-based plastic waste management, assisted in the move to a carbon-neutral society. Recycling PPW helps to reduce not only the amount of plastic waste that ends up in landfills and is burnt, but also GHG emissions by minimising the use of new plastic resins.

This study posits a defined means of network interaction and its importance in regulating PPW recycling and bringing circularity towards sustainability. The findings demonstrated the implications of analysis tools to tackle a vital driving force of sustainability in plastic packaging recycling. Several implementations are essential to engage PPW separation at the source to achieve the CE of PPW. Technical assistance, economic feasibility, increasing incentives, technology support, recycling facilities, and improving people’s knowledge and awareness raising are considered factors for implementation. These policy directions and strategies could be implemented systematically in short- to long-term conditions [35]. The circular strategies would be helpful for local authorities in Rayong Province and other localities to use Rayong as a role model to analyse the key actors in plastic waste recycling and apply the appropriate strategies for their areas to achieve sustainability and become a carbon-neutral society.

Acknowledgements

This research project was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT): NRCT5-RGJ63001-024 (2020). The author thanks NRCT for the Royal Golden Jubilee PhD scholarship granted to Sutisa Samitthiwetcharong and the financial support of the European Union and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the implementation of GIZ and Expertise France. Also the excellent support of all municipalities and organisations is acknowledged.

Author contributions

S.S. (M.Eng.) performed the data collection, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. P.K. (Ph.D.) analysed the data and made revisions to the manuscript. K.S. (Ph.D.) assisted in manuscript preparation. O.C. (Ph.D.) conceived the ideas, directed the research project, and edited the manuscript. All authors read, corrected, and approved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Eerkes-Medrano D, Thompson RC, Aldridge DC. Microplastics in freshwater systems: a review of the emerging threats, identification of knowledge gaps and prioritisation of research needs. Water Res. 2015;75:63–82. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jambeck JR, Geyer R, Wilcox C, Siegler TR, Perryman M, Andrady A, Narayan R, Law KL. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science. 2015;347:768–771. doi: 10.1126/science.1260352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv. 2017 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang YC, Lee G, Kwon Y, Lim JH, Jeong JH. Recycling and management practices of plastic packaging waste towards a circular economy in South Korea. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2020;158:104798. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes CJ. Plastic pollution and potential solutions. Sci Prog. 2018;101(3):207–260. doi: 10.3184/003685018X15294876706211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar R, Verma A, Shome A, Sinha R, Sinha S, Jha PK, Vara Prasad PV. Impacts of plastic pollution on ecosystem services, sustainable development goals, and need to focus on circular economy and policy interventions. Sustainability. 2021;13(17):9963. doi: 10.3390/su13179963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buch R, Marseille A, Williams M, Aggarwal R, Sharma A. From waste pickers to producers: an inclusive circular economy solution through development of cooperatives in waste management. Sustainability. 2021;13(16):8925. doi: 10.3390/su13168925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morseletto P. Targets for a circular economy. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2020;153:104553. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agamuthu P, Mehran S, Norkhairah A, Norkhairiyah A. Marine debris: a review of impacts and global initiatives. Waste Manag Res. 2019;37:987–1002. doi: 10.1177/0734242x19845041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foschi E, Bonoli A. The commitment of packaging industry in the framework of the european strategy for plastics in a circular economy. Adm Sci. 2019;9(1):18. doi: 10.3390/admsci9010018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen HL, Nath TK, Chong S, Foo V, Gibbins C, Lechner AM. The plastic waste problem in Malaysia: management, recycling and disposal of local and global plastic waste. SN Appl Sci. 2021;3:4. doi: 10.1007/s42452-021-04234-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calleja D (2019) Why the “New Plastics Economy” must be a circular economy. Field Actions Science Reports Publishing JournalsOpeneditionWeb. http://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/5123 Accessed 14 July 2022

- 13.Nakatani J, Maruyama T, Moriguchi Y. Revealing the intersectoral material flow of plastic containers and packaging in Japan. Proc NAS. 2020;117:19844–19853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2001379117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vassanadumrongdee S, Hoontrakool D, Marks D. Perception and behavioral changes of Thai youths towards the plastic bag charging program. Appl Environ Res. 2020;4:27–45. doi: 10.35762/AER.2020.42.2.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marks D, Miller MA, Vassanadumrongdee S. Closing the loop or widening the gap? The unequal politics of Thailand's circular economy in addressing marine plastic pollution. J Clean Prod. 2023;391:136218. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z, Adams M, Cote RP. How does circular economy respond to greenhouse gas emissions reduction: an analysis of Chinese plastic recycling industries. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;91:1162–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajbhandari S, Limmeechokchai B, Masui T. The impact of different GHG reduction scenarios on the economy and social welfare of Thailand using a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model. Energ Sustain Soc. 2019;9:1–21. doi: 10.1186/s13705-019-0200-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johannes HP, Kojima M, Iwasaki F, Edita EP. Applying the extended producer responsibility towards plastic waste in Asian developing countries for reducing marine plastic debris. Waste Manag Res. 2021;39(5):690–702. doi: 10.1177/0734242X211013412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pietzsch N, Ribeiro JLD, Medeiros JF. Benefits, challenges and critical factors of success for Zero Waste: a systematic literature review. Waste Manag. 2017;67:324–353. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bots PW, Van Twist MJ, Van Duin R (1999) Designing a power tool for policy analysts: dynamic actor network analysis. In: Proceedings of the 32nd annual Hawaii international conference on systems sciences. IEEE Publishing IEEEexploreWeb. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=772627. Access 10 May 2022.

- 21.Caniato M, Vaccari M, Visvanathan C, Zurbrügg C. Using social network and stakeholder analysis to help evaluate infectious waste management: a step towards a holistic assessment. Waste Manage. 2014;34(5):938–951. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farhangi M, Turvani ME, van der Valk A, Carsjens GJ. High-tech urban agriculture in Amsterdam: an actor network analysis. Sustainability. 2020;12(10):3955. doi: 10.3390/su12103955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narayan AS, Fischer M, Lüthi C. Social network analysis for water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH): application in governance of decentralised wastewater treatment in India using a novel validation methodology. Front Environ Sci. 2020;7:198. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2019.00198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kongshøj Wilson DC. Module 6: Stakeholder Analysis. In: Klenke R, Ring I, Kranz A, Jepsen N, Rauschmayer F, Henle K, editors. Human—wildlife conflicts in Europe. Environmental science and engineering. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayyad M (2009) Using the Actor-Network Theory to interpret e-government implementation barriers. In: Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on Theory and practice of electronic governance. Association for Computing Machinery Publishing IcegovWeb. Accessed 14 May 2022

- 26.Debrah JK, Vidal DG, Dinis MAP. Innovative use of plastic for a clean and sustainable environmental management: learning cases from Ghana, Africa. Urban Sci. 2021;5(1):12. doi: 10.3390/urbansci5010012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bui TD, Tsai FM, Tseng ML, Ali MH. Identifying sustainable solid waste management barriers in practice using the fuzzy Delphi method. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2020;154:104625. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wichai-utcha N, Chavalparit O. 3Rs Policy and plastic waste management in Thailand. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag. 2019;21:10–22. doi: 10.1007/s10163-018-0781-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yukalang N, Clarke B, Ross K. Barriers to effective municipal solid waste management in a rapidly urbanizing area in Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health Health. 2017;14:1013. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14091013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boonpa S, Sharp A. Waste-to-energy policy in Thailand. Energy Sources B: Econ Plan Policy. 2017;12:434–442. doi: 10.1080/15567249.2016.1176088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menikpura SNM, Gheewala SH, Bonnet S. Evaluation of the effect of recycling on sustainability of municipal solid waste management in Thailand. Waste Biomass Valor. 2013;4:237–325. doi: 10.1007/s12649-012-9119-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva K, Janta P, Chollacoop N. Points of consideration on climate adaptation of solar power plants in Thailand: how climate change affects site selection, construction and operation. Energies. 2021;15(1):171. doi: 10.3390/en15010171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quartey ET, Tosefa H, Danquah KAB, Obrsalova I. Theoretical framework for plastic waste management in Ghana through extended producer responsibility: case of sachet water waste. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(8):9907–9919. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120809907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNESCAP (2019) Closing the loop: Sai Mai district, Bangkok case study. Bangkok, Thailand

- 35.Foschi E, D’Addato F, Bonoli A. Plastic waste management: a comprehensive analysis of the current status to set up an after-use plastic strategy in Emilia-Romagna Region (Italy) Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28(19):24328–24341. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-08155-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]