Abstract

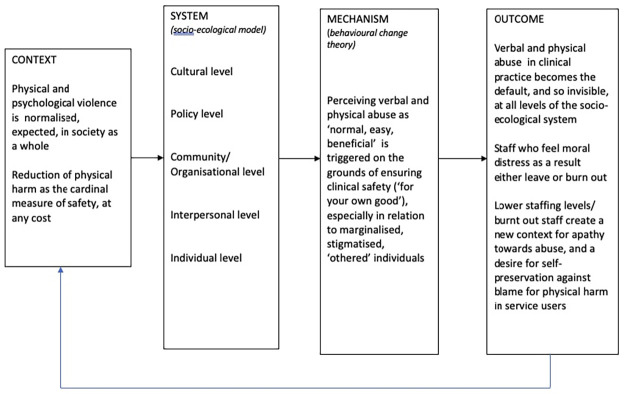

Despite global attention, physical and verbal abuse remains prevalent in maternity and newborn healthcare. We aimed to establish theoretical principles for interventions to reduce such abuse. We undertook a mixed methods systematic review of health and social care literature (MEDLINE, SocINDEX, Global Index Medicus, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Sept 29th 2020 and March 22nd 2022: no date or language restrictions). Papers that included theory were analysed narratively. Those with suitable outcome measures were meta-analysed. We used convergence results synthesis to integrate findings. In September 2020, 193 papers were retained (17,628 hits). 154 provided theoretical explanations; 38 were controlled studies. The update generated 39 studies (2695 hits), plus five from reference lists (12 controlled studies). A wide range of explicit and implicit theories were proposed. Eleven non-maternity controlled studies could be meta-analysed, but only for physical restraint, showing little intervention effect. Most interventions were multi-component. Synthesis suggests that a combination of systems level and behavioural change models might be effective. The maternity intervention studies could all be mapped to this approach. Two particular adverse contexts emerged; social normalisation of violence across the socio-ecological system, especially for ‘othered’ groups; and the belief that mistreatment is necessary to minimise clinical harm. The ethos and therefore the expression of mistreatment at each level of the system is moderated by the individuals who enact the system, through what they feel they can control, what is socially normal, and what benefits them in that context. Interventions to reduce verbal and physical abuse in maternity care should be locally tailored, and informed by theories encompassing all socio-ecological levels, and the psychological and emotional responses of individuals working within them. Attention should be paid to social normalisation of violence against ‘othered’ groups, and to the belief that intrapartum maternal mistreatment can optimise safe outcomes.

Introduction

In 2010, Bowser and Hill published a landscape analysis reporting on disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth [1]. In 2015, WHO published a review that classified disrespect and abuse into seven domains, under the overall typology of ‘mistreatment during childbirth’ [2]. These domains include verbal and physical abuse. Since the publication of these papers, there has been increasing evidence in this field, relating to both women and newborns [3–5]. As a result, efforts to improve maternal health are now focused on improving quality of both the provision and experience of maternity services as a critical component of Universal Health Coverage (UHC), particularly in LMIC settings. The current WHO recommendations on maternity care for a positive childbirth experience [6–8] emphasize the overarching importance of respectful maternity care. This includes the need for staff and health services to create enabling maternity environments to encourage a woman’s sense of control and their involvement in decision-making. Improving experiences of women during maternity care requires both promotion of respectful care, and reduction of mistreatment [1, 2]. In 2018, a systematic review of controlled studies undertaken in low-income settings and designed to increase respectful care was undertaken by some of the authors of the current review [9]. The findings indicated that multifactored approaches to increase respectful care could work in low-income settings. Based on the three findings with moderate confidence, we concluded that effective implementation to increase respectful care requires:

… a visible, sustained, and participatory intervention process, with committed facility leadership, management support, and staff engagement. It is still unclear precisely which elements of a package of RMC [respectful maternity care] implementation might be most successful, and most sustained over time….

As part of the move to promote respectful care, WHO has been working on improving the evidence globally in relation to measuring the prevalence of mistreatment of women during childbirth and raising awareness for evidence and action [10]. In 2019 the team published a paper reporting on a prospective cross-sectional study of women from admission in labour and up to two hours postpartum in twelve facilities across four countries (Ghana, Guinea, Myanmar, and Nigeria) [11]. Some degree of physical or verbal abuse or stigma/discrimination was observed in 838 (41·6%) of 2016 women, and reported by 945 (range 4–35% by facility) of those surveyed after their birth. Physical and verbal abuse was particularly prevalent in the half hour before birth and the 15 minutes afterwards, and verbal abuse was more likely to be experienced by younger than older women (≥30 years), adjusting for marital status and parity [11]. These findings suggest that little had changed in the ten years since Bowser and Hill first highlighted the issue of abuse in maternity care, despite a significant increase in studies in this area. Looking beyond the reproductive health literature may provide new insights for future effective interventions.

Issues of mistreatment have been identified in other health and social care fields [12]. In particular, there is a body of literature on de-implementation of inappropriate use of physical and pharmacological restraint in nursing and residential services [13], that mirrors current debates about use of unnecessary or unconsented physical and pharmacological interventions in maternity care. Indeed, use of physical restraint on women using maternity services has been reported most recently in 2020 [14, 15].

Although there may be some particular drivers for mistreatment in maternity care (including gender based inequalities, and social norms about desirable reproduction and undesirable reproduction) most underlying factors for mistreatment of service users in health and social care are likely to be similar across disciplines. To date, however, there have been no studies that explore the issue of mistreatment in general, and verbal and physical abuse in particular, in a cross-disciplinary review.

This paper reports on a mixed-methods systematic review of theoretical insights into what might underpin verbal and/or physical abuse in health and social care in general, and of interventions designed to reduce such abuse, with the aim of identifying candidate theories for designing future intervention studies. The findings are synthesised to generate hypotheses about the optimal theoretical underpinning for future implementation of change in this area, and the synthesis is then mapped to published intervention studies in maternity care.

Aim

To establish theoretical principles and mechanisms of what works in reducing physical and verbal abuse in health and social care, as a basis for designing effective interventions for maternity services in the future.

Research questions

What theoretical explanations have been proposed to explain drivers for and/or prevention of physical and verbal mistreatment by professional health and social care providers?

What interventions are effective, feasible and acceptable for reducing physical and/or verbal mistreatment of service users by professional providers of health and social care, when compared to usual care, or to alternative interventions?

What kinds of theoretically informed interventions work, or might work, in a range of contexts, to reduce physical and verbal abuse of childbearing women by health care providers?

Definitions

We used the following definitions of physical and verbal abuse, adapted from the Bohren [2] typology of mistreatment of women during childbirth, with additional terms that are relevant to other areas of health and social care, based on the results of our initial scoping review:

-

Verbal abuse

Harsh or rude language; shouting, insults, scolding, mocking; judgemental or accusatory comments; threats of withholding treatment or of using unnecessary treatment, or of poor outcomes; blaming for current situation, or current or potential future poor outcomes.

-

Physical abuse

Being beaten, slapped, kicked, punched, or pinched; physical restraint; gagged; physically tied down; (childbearing women: forceful downward pressure); rough use of instruments or interventions.

Reflexive statement

We maintained a reflexive stance throughout the review process, from study selection to data synthesis. Progress was discussed regularly among the team and decisions were explored critically. As a review team, we have a mixture of clinical, public health, and other backgrounds, including in midwifery (SD); medicine (LG, OT); psychology (GT, RN); public health (OT, HM); information science (CH), statistics (NA, HM) health services research (KF, CK); health technology assessment (AC). GT, SD, OT, KF had all undertaken prior primary and/or secondary studies in the area of respectful care, mistreatment, birth trauma, and/or maternal mental health, for maternity care users in general, or for marginalised groups specifically, prior to undertaking this review. LG had prior exposure to reproductive justice research. Based on our collective and individual experiences (as clinicians, academics and researchers, as well as health service users), we anticipated that the findings of our review would reveal that relational theories might underpin more effective interventions, and that multiple components, tailored to context, might be most effective, acceptable, and feasible. As a team, we remained aware of these prior beliefs, and we used disconfirmation checks to ensure that we were not over-interpreting data that supported our prior views, or that we were not overlooking data that disputed our pre-suppositions.

Materials and methods

We undertook a mixed-methods review. A scoping search was initially undertaken to refine the search terms, and to finalise the data sources, prior to formal searches being undertaken.

Once the included papers were located, those reporting maternity interventions were removed from the initial analysis. This was because our first step was to identify potentially transferable insights that were new to the maternity field. The remaining papers then were separated into those that included implicit or explicit reference to any relevant theory/ies, without reporting any interventions; and those that included interventions (with or without reference to theory). We then undertook the following steps:

Logging and narrative description of explicit/implicit theories

Meta-analysis of the findings in the non-maternity intervention papers with respect to any underlying theory used

Synthesis of the results of the first two steps

Mapping of the maternity intervention studies against the emerging synthesis

Creation of a logic model from the findings and synthesis

Search strategy

We undertook an initial scoping search in Medline using search terms proposed in the protocol. The search strategy was iteratively refined through testing in the Medline, SocINDEX and Global Index Medicus databases, and consultation with the review team, to improve the precision of the search and identify additional useful terms.

We initially searched the following databases on 29th Sept 2020 using the finalised search strategy: Medline (Ovid); SocINDEX (EBSCO); Global Index Medicus (including African Index Medicus (AIM), Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR), Index Medicus for South-East Asia Region (IMSEAR), Latin America and the Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences (LILACS), ans Western Pacific Region Index Medicus (WPRIM)); CINAHL Complete (EBSCO) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic reviews and Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Cochrane Library). Given the high yield of results retrieved in these databases, and potential overlap of content, the decision was made not to expand the search to further databases originally considered in the protocol. No date or language limits were applied to the search. The search was updated on March 22nd 2022. The full search strategy for the Medline database (Ovid platform) is provided in S1 Table. A log was set up to record hits and numbers of included papers at each stage of selection. One member of the review team (CH) undertook the searches in each database and carried out de-duplication. The de-duplicated results were imported into Rayyan for screening.

Study selection

At the title and abstract stage of both searches regular meetings were undertaken with the whole team to ensure consistency in decision making. At the full text stage, selection was initially undertaken in three pairs. Calibration exercises were conducted within each pair, where screeners independently screened 100 hits in batches until an 80% level of agreement was reached within the pair. Where sufficient agreement was not reached after the first 100 hits because of areas of uncertainty, this was discussed in the wider team, and the inclusion process was refined by consensus. This process continued until sufficient agreement was achieved. The remaining studies were then screened by four members of the review team (RN, AF, LG, HM) independently for the index search, and by SD and HM in the updated search, with consultation between team members where decisions could not be easily made.

Studies in languages that could not be translated sufficiently by the author team, google translate, or other contributors were logged but not included in the analysis.

As the selection process proceeded, it became apparent that there are a very large number of studies and papers focused on restraint and seclusion in psychiatric care. It was not always easy to determine if the issue was about therapeutic methods of restraint, or about restraint as abuse. To avoid overwhelming the review with papers from this very specific field, the decision was made to exclude papers on seclusion (as this was not deemed to be either verbal or physical abuse) and also to exclude those on medication in psychiatric settings as a means of restraint. We also excluded mechanical restraint in these settings, though we did retain papers on mechanical restraint in critical illness settings, as these were agreed to be more like the kinds of settings in which such restraint might be used in maternity care. For example, women in labour may be mechanically restrained if they have had a sedative (to prevent falls), or their movement may be constrained by IV lines, lithotomy, or wired fetal monitoring machines. See Table 1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Published research studies and theoretical analyses | Grey literature, PhD or masters theses, commentaries, blogs, media reports |

| Papers and studies with a theoretical component in the analysis or interpretation OR prospective intervention studies with ‘usual practice’ controls, including time-series designs, or with comparator interventions |

Descriptions/prevalence of factors associated with verbal/physical mistreatment, with no theoretical analysis of underlying issues Intervention studies without controls or comparators |

| Focus on physical or verbal mistreatment in health and social care provision settings/situations | Focus on understanding or explaining positive communication, or interventions focused on other aspects of mistreatment where verbal or physical mistreatment cannot be disaggregated |

| Focus on professional carers (people paid to provide care) | Focus on lay (voluntary/unpaid) carers, and family or group relations in general, or service user mistreatment of staff |

| Any health or social care discipline | Study or paper not specifically applied to health and social care |

| Any study type | |

| Any language | |

| Any date |

The intervention design and outcomes of controlled intervention studies in maternity care published since our previous systematic review of such studies [9] were tabulated and assessed against the synthesised theoretical framework of the current review, to establish the extent to which these interventions have been aligned, or not, to the findings of the review.

Studies and papers based in maternity care settings that included implicit or explicit theory were, however, included in the primary theoretical analysis.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias ratings were applied to studies included in the meta-analysis [16] There is no quality assessment tool for theoretical data, and, indeed, epistemologically this would not be relevant. Though the protocol stated that quality assessment would be undertaken for qualitative studies, it was decided in the team that this was not required, since the findings were not the unit of analysis: the issue of interest was the explicit and implicit theories that were evident in the included studies.

Record of study characteristics

For the research studies and articles including theoretical concepts, relevant data from all included full-text studies were logged on a study-specific data capture form. This included the bibliographic details, and characteristics of included papers; aim of study, participant characteristics (where relevant) implicit, explicit theories, other explanations of mistreatment; and findings from research papers. The form also captured the health/social care domain(s) of each paper, and the type of mistreatment that was addressed.

For the controlled studies, data were extracted using a pre-piloted form by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements were discussed between reviewers and, if consensus was not achieved, arbitration was carried out by a third reviewer. We extracted data on the citation details, country of study, study design, data collection method, primary outcome, secondary outcomes, intervention, underpinning theory, setting, type of mistreatment, participants characteristics, primary and secondary outcomes, and methods of data collection and analysis.

Analysis

Studies including theory

We intended to undertake an adaptation of the meta-narrative approach [17] to track theories used by different disciplines over time and to create an initial taxonomy of candidate theories that could underpin intervention studies to reduce physical and verbal abuse. In the event, very few studies included formal underpinning theory, so this analysis could not be undertaken. Our approach was to identify author-identified (‘explicit’) a-priori or post-hoc theories cited in the studies and to identify sections of the text of the included papers that referred to implicit or explicit theoretical concepts or models, or drivers for verbal or physical mistreatment. Both explicit and implicit theories were logged. We summarised these findings narratively.

Controlled intervention studies

Our outcome of interest was any reduction in any measure of physical or verbal abuse (primary). We also looked for information on the acceptability of the intervention(s) for staff or service users, fidelity to the protocol, and for any evidence of sustainability.

RCT and before and after (‘controlled’) intervention studies that had measures of relevance to the review were logged. Where possible, meta-analysis was undertaken to assess the effectiveness of the intervention. We pooled studies through the inverse variance method, estimating the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals, using random effects models.

Heterogeneity was assessed through visual inspection of the forest plots and the I2 statistic. Pre-specified sub-group analyses were produced, focusing on study design, underpinning theory, care setting, people receiving the intervention, type of intervention and country income level. Sensitivity analyses explored the effects of different studies on the outcomes.

We also intended to use network meta-analysis techniques [18], if the data were robust enough, to identify pathways that stood out as highly influential, or contexts that tended to be associated with the success or otherwise of particular theories. In the event, this was not possible due to insufficient data of adequate precision to develop an evidence network.

Synthesis and logic model

We used a results-based convergent synthesis to integrate the findings across the papers with theoretical elements and intervention studies [19], as a means of answering our third research question. This approach is defined by Hong as: where qualitative and quantitative evidence is analyzed separately using different synthesis methods and results of both syntheses are integrated during a final synthesis [19]. The synthesis was intended to illuminate what fundamental theoretical approach(es) might have most utility as a basis for designing interventions to reduce physical or verbal mistreatment in a range of contexts. We then mapped the resulting model to controlled studies in maternity service provision to assess the extent to which our model is reflected currently in interventions used in controlled studies designed to reduce verbal and/or physical abuse in maternity care. Finally, we created a logic model as the basis for hypotheses about critical contexts and mechanisms of effect arising from our findings.

Changes from protocol

Changes from the protocol are described above.

Results

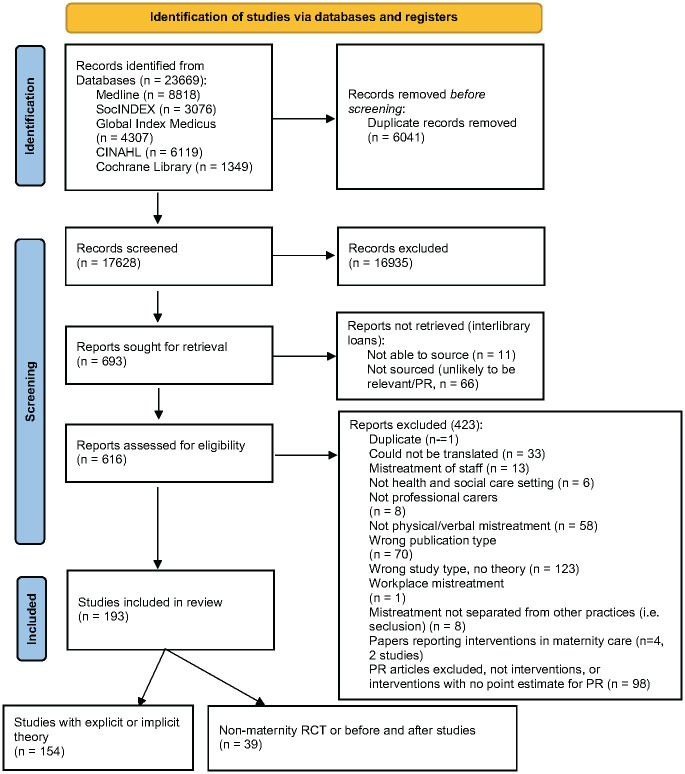

In the primary search (2020), a total of 23,699 studies were identified from the database searches. Following de-duplication 17,628 were retained for screening. Screening on title/abstract revealed 693 relevant studies for full text review. Many of these were focused on physical restraint in a range of settings. Ninety of them required inter-library loan requests, and a decision was made to only pursue a sub-set that were intervention studies, or that were not physical restraint studies (n = 24). Eleven of these could not be sourced, leaving 616 for full text screening selection. During full text screening it became apparent that a very large proportion of the remaining studies meeting the inclusion criteria were also focused on physical restraint. At that point, it was decided that the remaining physical restraint papers would be excluded, unless they were intervention studies, or studies with a strong theoretical basis. During closer scrutiny by the quantitative team, thirteen of the RCT or before and after studies of restraint did not have identifiable point estimate measures of restraint use, and so these were also excluded. Ninety-eight of 150 physical restraint papers were therefore excluded at this stage. A further 324 papers were excluded for a range of reasons (Fig 1).

Fig 1. PRISMA flow chart, index search (29th Sept 2020).

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

The remaining 193 included papers were grouped into those including theoretical components (n = 154 [20–173]) (qualitative and quantitative and reviews) and (n = 39 [174–212]) non-maternity controlled intervention studies with at least one outcome measure of verbal or physical abuse.

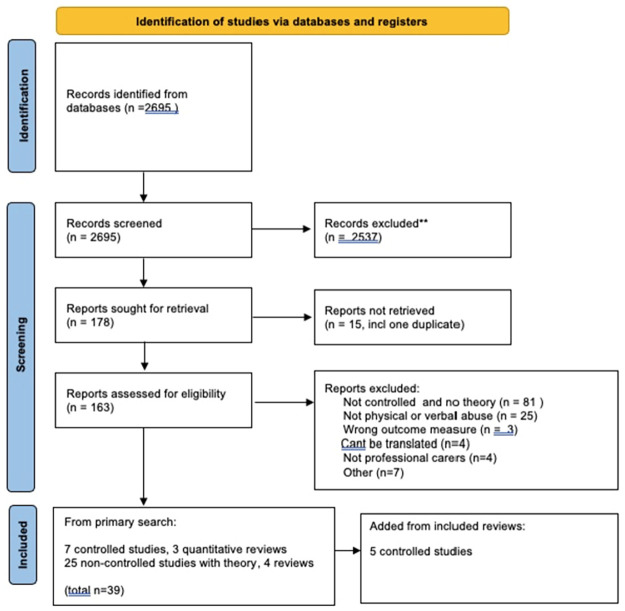

In the updated search (2022), of 2695 hits from the updated search, 29 had theoretical components [213–241], including 4 reviews [217, 218, 221, 233] and 14 non-maternity controlled studies with at least one measure of verbal or physical abuse [242–255] (Fig 2).

Fig 2. PRISMA flow chart, updated search (22nd March 2022).

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

Six of these were controlled studies, based in emergency/ITU/critical care[246, 253, 254] inpatient geriatric care [243]; a youth behavioural unit [247] and adult psychiatric care [255]. Three quantitative reviews were included [242, 245, 252] and their reference lists generated five of the included primary studies [244, 248–251]. Two of the included studies could be metaanalysed [248, 253].

In the updated inclusion decision process, we did not check for primary papers included in the previously published reviews that had not been identified by our search, given that the primary papers in the previous reviews were not selected for their theoretical content. However, we did check to ensure there was no substantial overlap between the papers contributing to the previous reviews and our primary theory papers, to avoid ‘double weighting’ of the overall contribution of the prior reviews to our analysis.

The three included reviews of controlled studies [242, 245, 252] and two of the primary controlled papers [243, 244] also included some theory. They are included in the analysis of theory papers, resulting in a total of 34 papers with theoretical components. The results of both searches are combined in the rest of this paper.

Papers with underlying theoretical components (n = 188)

The characteristics of the 188 papers with explicit or implicit underlying theories in the study design, analysis, interpretation or discussion from the first (n = 154) and second (n = 34) reviews are provided in S2 and S3 Tables. The date of publication ranged from 1988–2022, and they were undertaken in all regions of the world. For maternity focused papers with theory, 48/58 were based in low or middle income countries [20, 22, 26, 30, 31, 38, 39, 44, 46, 53, 54, 59, 60, 63, 75, 100–102, 120, 122, 124, 140, 148, 150, 151, 154, 156, 157, 159–161, 167, 171–173, 217, 219–222, 224, 225, 226, 229, 230, 235, 236], with larger numbers of studies from Ethiopia [31, 38, 59, 60, 154, 221], India [44, 75, 120, 124, 154, 157, 198], Kenya [20, 22, 140, 171, 172] Tanzania [148, 150, 156, 160] and Brazil [161, 222, 225, 226, 230]. In contrast, the vast majority of the 130 studies based in other areas of health care took place in high income countries, with large numbers from North America [23, 28, 32, 40, 48, 55, 66–69, 82–84, 91, 96, 105, 106, 113, 129, 130, 132, 143, 145, 146, 153, 163, 165, 218, 239, 242–244].

The topics included mistreatment in maternity settings (n = 58) [19, 21, 24, 26, 30, 31, 38,39, 43, 44, 46, 53, 54, 59, 60, 63, 75, 85, 88, 90, 97–102, 120, 122–124, 140, 148, 150, 151, 154–157, 159–161, 167, 169, 171–173, 215, 218, 219, 220, 222, 224–226, 229, 230, 235, 236]; physical restraint in mental health settings (n = 30) [23, 32, 40, 41, 48–51, 56, 73, 80, 82, 83, 91, 93, 99, 106, 112, 113, 118, 120, 149, 163, 165, 223, 234, 238, 240, 244, 253]; physical or verbal abuse and/or restraint in elderly residential care settings (n = 44) [17, 28, 29, 36, 42, 45, 47, 57, 58, 62, 65–70, 81, 92, 95, 96, 98, 103, 104, 107–111, 115–117, 119, 126, 132, 134, 135, 189, 164, 168, 214, 228, 232, 241, 243], verbal and/or physical abuse in other settings (n = 35) [33–35, 37, 52, 55, 61, 64, 71, 72, 76–78, 86, 89, 94, 113, 121, 128, 131, 136–138, 143–146, 152, 153, 158, 162, 116, 227, 239, 242]; and physical restraint only in other health care settings (n = 21) [21, 25, 74, 79, 84, 87, 105, 125, 127, 130, 133, 141, 142, 147, 166, 170, 215, 231, 233, 237, 244].

Table 2 provides examples of the theories included for each of these categories.

Table 2. Examples of explicit or implicit theories in included papers, by mistreatment type/ setting.

| Category | Maternity (n = 58) | Other healthcare settings, not physical restraint (n = 35)* | Physical restraint, not mental health or elderly (n = 21)# | Physical abuse or restraint–elderly (n = 44) | Physical restraint–mental health (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit theories | Conceptual (structural framework for disrespectful care [53, 54, 173]; Obstetric violence (theory) [157, 215, 218, 222, 230, 225, 226, 229], Overmedicalisation of childbirth [53,75, 217, 218, 230] Gender inequalities (theory developed using USAID Gender Analysis Framework [43] Gender theory [97]; (structural) gender inequality [161, 172, 173];, Gender based violence [75, 140]; Patriarchy [75] Feminist critiques [219]Oppressed groups theory [54], Stigma [140, 151, 172], Moral evaluation of patients[123] Intersectionality [97], Normalisation of violence [50, 217, 218, 224, 226, 235] Foucault (Theory of Inscription/power) [88, 225], Jacobson’s taxonomy of dignity [88], Learned helplessness [88]. Mental models, ‘automaticity’, cognitive availability/scarcity [159], communication theory [54] Authoritative knowledge [160] Cultural health capital [157], Socio-ecological theory [236] Social movements theory [97], |

Socioecological/ecological theory [27, 121, 128], positioning [162], medicalisation [113] (medical model of disability), Theory of reasoned action [138] | The theory of planned behaviour [142, 170] Normalisation of restraint [231, 233] Human rights [231], Iceberg theory [213] Risk aversion [242] Labelling theory (victim-blaming) [237] | Stereotyping (ageism [228], normalisation of stereotypes) [234], Racial disparities [66], moral geographies [29], The theory of reasoned action/planned behaviour [42, 241] Complexity theory [28] open systems theory [68], Socioecological model/theory [216, 228] | (Response to) discriminative stimulus control (behaviour towards staff) & motivating operations (attention-seeking) [129]–relating to the behaviour of the patient, Stigma[56, 234] Trauma informed care [253] Salutogenesis (low Sense of Coherence) [253], Social learning theory [253] Behavioural change theory [240] |

| Implicit theories | Gender inequalities, Gender-based violence, Structural inequalities, Racism, Class inequality, Intersectionality, rurality normalisation/ trivialisation of abuse (personal, organisational, societal), power dynamics, social/cultural norms, behavioural change theory, pathologisation, supervaluation of technology, risk aversion, health industrialisation, behavioural change theory, socio-ecological theory | Institutional, situational and patient characteristics, discrimination, trauma-informed, behavioural change theory | Balance between ‘safety’ and humane care;’safety/risk’ conceptualisations, Institutional norms, risk minimisation (patient safety), labelling theory, depersonalisation and dehumanisation (learning difficulty) behavioural change theory, socio-ecological theory | Risk minimisation/ avoidance—individual level patient safety, staff safety; organisational level–avoiding litigation risk), paternalism (elderly subjects of paternalist control), objectivisation, system failure, dehumanisation, rights violations, behavioural change theory, socio-ecological theory | Patient autonomy, trauma response, organizational culture, risk minimisation/avoidance (patient safety, staff safety, safety vs humanisation), gender inequalities, organisational culture (staffing/resources), behavioural norms (staff knowledge, nurse attitudes), behavioural change theory, socio-ecological theory |

*mostly elderly/learning disabilities

#mostly surgical or acute care

The following section expands on the theories listed in Table 2.

Maternity studies (n = 58)

About half of the maternity papers mentioned explicit theories. These included gender inequalities (theory developed using USAID Gender Analysis Framework [43]; and feminist critique [219], gender theory [97]; (structural) gender inequality [161, 172]; oppressed groups theory [54] in relation to hospital hierarchies; gender based violence[75, 140]; overmedicalisation of childbirth [53, 75, 117, 218, 230], and associated patriarchy [75]; cultural health capital [157]; stigma [140, 151, 172] and moral evaluation of patients [123]; Foucault’s (1979) theory of Inscription [88], in which the risk of being judged “abnormal” by others is internalized, making powerful norms work from within, and Foucaults theories of power/resistance to power [225]; and Jacobson’s taxonomy of dignity [88], and learned helplessness [88]. One paper [159] explored behavioural concepts of mental models, and of ‘automaticity’ (based on the concept of cognitive availability/scarcity, in which a hegemonous focus on death avoidance left no space for consideration of other aspects of good quality maternity care. Another [160] was framed by the notion of authoritative knowledge, in which the knowledge and beliefs of the most powerful group frame what is acceptable in terms of actions. One paper explicitly cited the socio-ecological theory [236].

Implicit theories used in the maternity studies tend to focus on gender inequalities [43, 160], internalised, organisational and social norms around general acceptability of mistreatment [22, 39, 46, 160, 217, 218, 224, 226, 235] (for example, in the case of the ‘difficult’ patient, or where the safety of the baby was seen to be at risk) and social/cultural norms about the acceptability and expectation of violence against women (gender-based violence) [22, 39, 75, 157, 173], control of deviation from perceived gender/role or stereotype [43], and stigma and shaming around sex (as dirty or sinful) [24, 46, 157, 159]. Vertical transmission of mistreatment was captured in theoretical assumptions that gender inequalities and consequent mistreatment experienced by female staff (including limited access to resources and opportunities) could lead to frustration and burnout and consequently blunted compassionate relating, resulting in mistreatment of women during childbirth and labour.

Some of the theories capture how intersectionality compounds inequalities in both female staff and service users, and in hierarchies within gender (related to class, ethnicity or marital status). From this perspective, assertion of power differentials (from institutionally oppressed health care professionals to socially oppressed service users) results in social sanctioning, and punishment of service users for not following the institutional rules, or for non-payment of fees, as this is a domain over which the staff have control, and the service users do not. Social sanctioning includes restriction of birth companionship to avoid anticipated resistance to rules if the woman has a companion with her, or to minimise external observation of mistreatment.

The relative lack of power of female staff as compared to equivalent male staff is proposed as a reason for finding evidence of greater mistreatment by female midwives/nurses than male health workers in equivalent roles. Power based theories also argue that the struggle to assert the professional status of midwifery/nursing results in preference for over-medicalisation by staff in some contexts, and of strong local norms in which service users are often conceptualised as inferior to staff, socially and morally. In a nuanced take on gender based violence theories, where the gender of the person inflicting abuse was explicitly examined, it was more often attributed to female rather than male staff.

Poorly resourced facilities (i.e. resources, workload, skilled staff) and institutional infrastructure (lack of supervision) are repeatedly mentioned across papers, as are institutional norms about mistreatment (e.g. as acceptable practice).

In the index review, there are some differences in emphasis across the dataset. Within African countries, some report on gender based violence (Ethiopia [31, 38, 155], Kenya [22]) or sexual shame (Nigeria) [46]). In others, this is focused on other forms of discrimination, such as social class. In contrast, for India and Pakistan, analyses were more likely to be undertaken through the lens of social class discrimination [44, 102, 154]. Studies undertaken in Arabic counties cited predominately cultural/institutional hierarchies/pressures [24, 30, 100]. However, these differences were not as evident in the papers generated by the updated review.

Two conceptual frameworks were cited: The Conceptual Framework for Disrespectful Care in Maternity which includes drivers of mistreatment and abuse [53, 54], and the Framework of Obstetric Violence, which includes both facilitators of such behaviour (social factors, harmful cultural practices, systemic barriers, historic normalisation), and solutions for change [157]. The general concept of obstetric violence featured in a number of studies [eg, 216, 218, 222, 225, 226, 229, 230].

Physical and verbal abuse in non-maternity studies, other than physical restraint (n = 35)

A few studies in this category include patients in general wards and emergency departments [33, 35, 71, 72, 131, 158], adults with learning difficulties [64, 113], and psychiatric inpatients [86]. However, most identify risk factors associated with mistreatment of elderly persons in residential care [37, 52, 55, 61, 76–78, 89, 94, 121, 128, 136–138, 143–146, 152, 153, 162], highlighting interactions between institutional factors and staff and patient characteristics, rather than proposing theories to explain this, with the exception of two papers. Moore [136] discusses a range of social psychology theories and explores findings using a socioecological framework, proposing that Henri Tajfel’s theory on the social psychology of intergroup relations is a useful theoretical model to explain abuse of elderly people in a care home. Natan [138] uses the theoretical model for predicting causes of maltreatment of elderly residents developed by Pillemer [144]. This includes three components of the work environment; patient traits; and the Theory of Reasoned Action developed by Ajzen & Fishbein [256].

One of the papers also mentions exogenous factors [144] such as bed shortage based on local supply and unemployment rates. Another paper [162] on elderly care used the positioning theory in which interactions are conceptualised as being based on individuals taking certain ‘positions’: clusters of rights and duties to act in certain ways and impose particular meanings, which enable or prohibit access to certain storylines. The medical model of disability is mentioned in a paper about care of women with learning disabilities [113].

More generally, most papers in this area argue that relevant situational factors, including staff burnout, patient-staff conflict, lack of knowledge and/or relational factors impact on mistreatment [61, 78, 121, 128, 144–146]. Victim blaming was used as a justification for mistreatment in a number of studies, on the basis that elderly residents were aggressive and abusive, and therefore required a robust physical or verbally response to regain control over the individual and/or the situation [37, 76, 77, 138]. Gender issues were also raised, in that female older adults were noted to be most likely to experience physical abuse [37, 131, 138, 152]. In parallel with the evidence on mistreatment in maternity care when women do not have labour and birth companionship, social isolation was noted to be a relevant factor, particularly for older adults who did not have relatives and friends as protectors, so were deemed to be most likely to experience abuse [37, 144].

A conceptual review [257] was referenced in one of the included papers. This was not located in the search for the current study, as it did not include the key words. This review identifies a typology of risk factors for maltreatment, including institutional factors, carer and patient characteristics.

Physical restraint, not in elderly populations or in mental health (n-21)

An explicit theory was only mentioned in a few papers in this category. Both Via-Clavero [170] and Perez [142] used the theory of planned behaviour to explain physical restraint use and how to reduce it in intensive care unit settings. The authors discuss the influence of workload pressures on nurses’ intention to use physical restraint, and subjective norms and controlling factors that contribute to this, in line with Ajzans theory [256]. Acevedo-Nuevo uses the Iceberg theory noting: ‘According to this theory, the visible part of the iceberg represents PR use, but lower down, an intricate network of interrelated elements is at work; here, all health care actors exert an influence on the main actors in PR use (i.e., the nurses) (p3) [213]. Social and organisational normalisation/ of restraint is explicitly referred to in two studies (p78) [231, 233]. Smithard notes: For many the use has become institutionalized, with accepted practice hard to change [233].

Staff and external organisational risk aversion [242] and labelling theory (related to victim blaming) [237] also feature in this group of studies.

Implicitly, notions of institutional norms to protect patient safety are particularly evident in the studies in the intensive/critical care setting, either due to the nature of the procedure or patients’ functional ability, centred around preventing interference with tubes and/or to prevent extubation [105, 130, 133, 142]. Lach notes that Prevention of falls is a primary reason for restraint use on medical–surgical units, whereas preventing removal of medical devices and confusion are primary reasons in critical care settings.[125] In many of these analyses, the point is made that there is evidence that restraint use in these settings does not in fact lead to decreased danger for patients, in direct contrast to nurses beliefs.

In three studies [105, 142, 242], the concept of risk minimisation is discussed in more depth along with the implications of a blame culture in which nurses have to take on responsibility for decision making in relation to restraint use in critical/acute care. The argument is that this leads to unnecessary or over-use of restraint, for fear of litigation, or of blame within the organisational structure, in line with some of the self-protective theories in maternity care noted above. In this case, the personal consequences of making a decision that is not in line with the risk minimisation focus of the organisation outweighs the risk to the patient, or the professional values of the nurse, leading to a sense of lack of mutual support, and therefore increasing the likelihood of using physical restraint.

Physical abuse or restraint in the elderly (n = 44)

Where explicit theories occurred in this set of papers, they included the use of complexity theory [28], and the theory of self-organisation (practice that emerges based on the interconnectivity between people and how they relate to each other), and related notions of open systems theory [68], in which organisations are influenced by the context and environment they operate in. Approaches also included moral geographies [29] in which moral norms for a particular group are calibrated in relation to the physical proximity of people to each other, and across different geographical spaces, such as private versus public domains. Behavioural change theories featured in two papers [42, 241]. Theories of racism [66] were also used, where Black residents were more likely to be abused than White residents. Stereotyping and normalisation of stereotypes, specifically negative beliefs about, and attitudes towards, the social value and status of the elderly were identified [228, 232]. Some authors developed their own frameworks of interactions between factors such as organisational, resident functional capacities/behaviour, personal and psychosocial drivers, and physical environment, to examine associations with physical restraint [164, 132]. For two authors, these levels of action were formally captured in the socio-ecological model [116, 228].

Where theory was implicit, the predominant explanation of the use of physical restraint in elderly population is for patient safety (e.g. to protect patients from falls and prevent injury from wandering). Underlying this ideology of protection of elderly residents is a belief system within institutions that patients are frail and have diminished responsibility and lack autonomy, in parallel with staff fear of litigation or blame by peers and superiors when accidents and injuries do occur. Thus, as in other sections of this review, physical pressure or restraint was used in the belief that it offered protection from adverse physical outcomes for the elderly, and was prioritised over dignity and autonomy, even though this was recognised as dehumanising by some staff.

The consequent disconnect between professional values of care and compassion and the action of enacting physical restraint resulted in moral distress for some staff. Indeed, some papers discussed the need for balance in maintaining physical and psychological integrity, presenting nurses with an ethical dilemma with the use of physical restraints. In this case, underpinning decision-making was the ideology of nursing as a moral practice (particularly Goethals [95]). This is associated with ‘doing good’ with protecting patients from physical harm and/or maintaining the psychological integrity/safety of other elderly patients.

One review highlighted social and cultural norms as an important influencer of physical restraint by nursing staff, highlighting differences in restraint use between the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland [114].

Physical restraint in those with mental health issues (n = 30)

Two papers in this group focused on stigma against those with mental health issues [56, 234], Trauma informed care, social learning theory, salutogenesis (ie, the impact of a low Sense of Coherence) all featured in a review undertaken by Perers [253], Other studies related to this topic were more focused on behavioural and psychological theories, including how staff response is stimulated by patient actions [129] and behavioural change theory [240].

Implicit theories were linked to the dilemma between risk minimization and humanization. Organisational barriers to environments that promote on-going support of, and knowledge development in, local practitioners included low levels of staffing and resources. Gender inequalities also featured in some of the discussions, in terms of assumptions about how men and women ‘typically‘ provoke violence, or not.

Another emergent topic in this category was the need for staff to optimize a sense of safety and security within a mental health setting, and consequent risk aversion. The argument is that when there is increased staff exposure to resident or patient aggression, there may also be an increase in the use of restraints, due to a desire for self-preservation by staff [41]. In some cases, nurses acknowledged that while it is not a first line treatment, in situations where no other alternatives exist, restraint is a ‘necessary evil’ [93].

Although not mentioned as a primary theory, patient-provider communication was found to be an implicit theme in a number of studies in which patients/residents reported that restraint was unnecessarily overused, linking with the over-medicalisation theories in other sections above [56]. In another study, discussion with patients uncovered a desire for communication and collaboration to establish restraint-use alternatives [91].

Papers reporting non-maternity intervention studies (n = 53)

The full characteristics of these papers are given in S4 and S5 Tables. The summary characteristics are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of characteristics of included primary non maternity intervention studies.

| RCT/CCT | Before & After | |

|---|---|---|

| Study Setting | ||

| In facilities/acute care | 3 | |

| Care home | 10 | 2 |

| Children’s care home | 2 | |

| Hospital | 1 | |

| ICU | 11 | |

| Psychiatric hospital | 5 | 15 |

| Residential camp | 1 | |

| Country | ||

| Canada | 1 | |

| China | 1 | 2 |

| Denmark | 1 | |

| Finland | 1 | |

| Germany | 3 | |

| Iran | 1 | |

| Netherlands | 3 | |

| New Zealand | 1 | |

| Norway | 2 | |

| Spain | ||

| Sweden | 1 | |

| Taiwan | 2 | |

| UK | 1 | 2 |

| USA | 1 | 23 |

| NR/various | 1 | 3 |

| Intervention based on theory | ||

| Yes | 7 | 11 |

| No | 6 | 12 |

| Unclear | 2 | 12 |

| Intervention type | ||

| Education/training | 7 | 5 |

| Mindfulness | 1 | 2 |

| Multicomponent | 6 | 27 |

They included 15 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) [174, 176, 182, 187, 191–193, 195, 199, 200, 203, 208, 209, 258] and 35 prospective before and after studies (pre- and post-design) [165, 177–181, 183–186, 188–190, 194, 197, 198, 202–210, 243, 244, 246–251, 253, 254],. Three were reviews [242, 245, 252]. Most studies were set in psychiatric hospitals (n = 20) [176, 177, 181–183, 185–189, 198, 200–202, 206, 217, 243, 244, 247, 255] or elderly care homes (n = 12) [174, 191–193, 195, 196, 199, 203–205, 207, 209]. Other settings included acute and other hospitals (n = 4) [118, 178–180], intensive care units (ICU) or emergency units (n = 11) [175, 196, 197, 212, 246, 248–250, 251, 253, 254], children’s care homes (n = 2) [184, 190] and a residential camp (n = 1) [210]. All the studies were conducted in MICs or HICs, particularly the USA (n = 24) [178, 181, 182, 184–186, 188, 190, 194, 198, 201, 202, 206, 207, 210, 201, 243, 244, 247–249, 250, 251, 253].

In 18 studies the intervention was based on an underlying theory (7 RCTs/CCTs and 11 before and after studies) [175, 159, 161, 162, 164–167, 169, 172–176, 180, 181, 224, 225]. The interventions were predominantly either multicomponent (n = 33) [175, 176, 177, 182–190, 195–198, 200, 202, 206, 208, 209, 211, 243, 244, 246–250, 251, 253–255] or educational/training (n = 12) [175, 178, 199, 191–194, 199, 207, 208, 210, 212] They were all compared with usual care (including baseline standard practice for before and after studies). The outcomes assessed focused on different measures of restraint, including prevalence, reduction in numbers of restraint episodes, or staffs’ attitudes towards and perceptions of restraint.

Fidelity, acceptability and sustainability

This was assessed for the studies in the updated review. In general, these domains were not well reported. Only one paper cited a protocol [255] but this could not be found on the Chinese Trials Registry, and it isn’t clear if the study followed the protocol that was registered.

Chen [246] and Dixon [247] both reported that their tools seemed to be acceptable to staff. Hevener [249] undertook a formal staff audit, and noted that, while the majority of respondents found the intervention tool (the Restraint Decision Wheel) to be useful in principle, they still preferred to use their own judgement in deciding when to restrain a service user.

Sustainability was implied for six studies where time series data were reported [243, 244, 249, 250, 251, 253], all generally showing maintenance of changes over time.

Effectiveness

For individual studies, comparison of the different interventions with usual care tended to demonstrate positive change in the primary outcomes measured in the intervention arms, or the ‘after’ phase. However, only 14 studies provided point estimates and measures of variability to enable meta-analysis, and these were all measures of impact on physical restraint [174, 183, 187–188, 191, 193, 194, 196–198, 203, 204, 248, 253]. The characteristics of these studies are provided in Table 4.

Table 4. Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Setting | Design | Primary outcome | Outcome in current analysis | Intervention | Underlying theory | Comparator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham[174] 2019 Germany | 120 elderly nursing homes in 4 regions | Cluster RCT | Physical restraint prevalence | Mean prevalence (%) of any physical restraint | 1Two versions of a guideline, & a multicomponent educational intervention 2Concise version of 1 | No explicit theory mentioned (guidelines developed through consultations with experts)–targeting nurses’ attitudes and organisational culture, though Kopke referenced, which implies the theory of planned behaviour | Optimized usual care (supportive materials only) |

| Bowers [183] 2006 UK |

Two acute psychiatric wards | B&A | Multiple conflict and containment outcomes | Restrained mean per shift | Two ‘City Nurses’ were employed to work with ward staff, to operationalise the working model | No explicit theory mentioned–working model involving positive appreciation, emotional regulation and effective structure–based on 6 core components: 1) the psychiatric philosophy of staff; 2) their moral commitments, 3) their use of cognitive-emotional self-management methods, 4) their technical mastery in interpersonal skills, 5) team work skills, 6) organisational support. | Before intervention |

| Duxbury [187] 2018 UK |

14 acute psychiatric wards in 7 hospitals | Individual RCT | Physical restraint incidents | Restraint event rates per 1000 bed-days | REsTRAIN YOURSELF intervention: (UK) modified version of ’Six Core Strategies’ (US) multimodal approach to reduce restraint—prevention & trauma informed principles | No explicit theory mentioned–—underpinned by principles of prevention and trauma informed care—based on six core strategies–leaders for organisational change, the use of data to inform practice, workforce development, person-centred tools, service user roles within patient settings and debriefing techniques. | Usual care |

| Godfrey [188] 2014 USA |

1 psychiatric ward | B&A | Mechanical restraint incidents | Mechanical restraint use (daily incidence rate) | 2 strategies: (1) staff training in de-escalation techniques (2) policy change for the use of mechanical restraint | No explicit theory mentioned–based on recovery oriented trauma-informed care | Before intervention |

| Huizing [191] 2006 Netherlands |

5 psycho-geriatric nursing homes | Cluster RCT | Restraint prevalence and intensity | Mean % of residents observed being physically restrained at any time during a 24hrs period | An educational programme for selected staff to reduce restraint use, and a consultation with a nurse specialist | No explicit theory mentioned | Usual care |

| Huizing [192] 2009 Netherlands |

5 psycho-geriatric nursing homes | Cluster RCT | Restrained status, intensity, use of multiple restraints | No. of times resident was physically restrained in 24hrs | An educational programme for selected staff to reduce restraint use, and a consultation with a nurse specialist | No explicit theory mentioned. | Usual care |

| Johnson [194] 2016 USA |

1 trauma intensive care unit | B&A | Restraint use | Mean Restraints per 1000 patient days | Power point review of non-pharmacological interventions and alternative devices with hands on demonstration with the devices were provided in the TICU on both day/evening shift. The programme was designed to enable staff to tailor appropriate non-pharmacological devices to the individual patient | No explicit theory mentioned | Before intervention |

| Kopke [196] 2012 Germany |

36 nursing home clusters | Cluster RCT | % of residents with physical restraint | % of residents with physical restraint | A multidisciplinary approach designed to address attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control; evidence-based guideline, information programs, endorsement of nursing home leaders, and support materials | Theory of planned behaviour | Standard information delivered in previously developed brochures |

| Lin [197] 2018 Taiwan |

3 neurological intensive care units | B&A | Incidence rate of physical restraint | Physical restraint hours | Standardised PR reduction program developed by a multidisciplinary team | No explicit theory mentioned | Before intervention |

| McCue [198] 2004 USA |

1 hospital: psychiatric inpatient service | B&A | Restraint use | Number of restraints per 1000 patients days | 6 interventions primarily involving changing staff behaviour: better identification of restraint, stress/anger management group for patients, staff training on crisis intervention, development of a crisis response team, daily review of restraints, a staff incentive system | No explicit theory mentioned | Before intervention |

| Singh [203] 2016a USA |

5 care homes for those with intellectual disabilities | Individual RCT | Reduction in psychological stress, physical restraints and restraint medications | Average use of physical restraint per week | 7-day Mindfulness-Based Positive Behaviour Support (MBPBS) for caregivers | No explicit theory mentioned. | Training as usual |

| Singh [204] 2016b USA |

1 care home for those with intellectual and developmental disabilities | B&A | Reduction in physical restraints, staff injury, peer injury, staff turnover | Weekly frequency of staff use of physical restraints | 7-day Mindfulness-Based Positive Behaviour Support (MBPBS) for caregivers | No explicit theory mentioned. | Before intervention |

| Hall [248] 2018 USA |

1 intensive care unit | B&A | Proportion of patients restrained | Restrained patients per patient day | Daily audit and review of restraint information; Customized restraint management education, including case studies; standardising and monitoring restraint audit tool | No explicit theory | Before intervention |

| Shields [253] 2021 USA |

1 ICU unit | B&A | Restraint use | Mean % with restraints | 12 different components for the intervention package | No explicit theory mentioned. | Before intervention |

Most of the meta-analysed papers do not explicitly mention underlying theory. Some report consultation work to develop guidelines with experts based on the evidence base, but do not mention specifics about the evidence base. Where explicit theory is mentioned, and where theory was implicit, the general approach seems to have been some version of the theory of planned behaviour [262]. Thirteen of the interventions [174, 183, 187, 188, 191, 193, 194, 196–198, 203, 204] were primarily focused on training in alternative strategies so appear to be based on the hypothesis that excessive use of restraint is related to a lack of knowledge about alternatives. Two papers (same study team) [203, 204] used mindfulness methods, implying a hypothesis that stress/distress in staff or patients could be a trigger for unnecessary physical restraint

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias was evaluated for all of the studies included in the meta-analysis (See Table 5). Full risk of bias details are in S6 Table.

Table 5. Summary risk of bias for studies included in the meta-analysis.

| RCT (Parallel) | |

| Singh 2016a [203] | Some concerns |

| RCT (Cluster) | |

| Abraham 2019 [174] | Some concerns |

| Huizing 2006 [191] | Some concerns |

| Huizing 2009 [192] | Some concerns |

| Kopke 2012 [196] | Some concerns |

| Before & After | |

| Bowers 2006 [183] | Fair |

| Duxbury 2019 [187] | Fair |

| Godfrey 2014 [188] | Good |

| Hall 2018 [248] | Fair |

| Johnson 2016 [194] | Fair |

| Lin 2018 [197] | Good |

| McCue 2004 [198] | Poor |

| Shields 2021 [254] | Fair |

| Singh 2016b [204] | Fair |

The assessment revealed some concerns with twelve of the fourteen studies (and all of the RCTs) [174, 183, 187, 191, 193, 194, 196, 198, 203, 204]. The funnel plots also suggest some publication bias, so the results of the meta-analysis should be treated with caution.

Findings

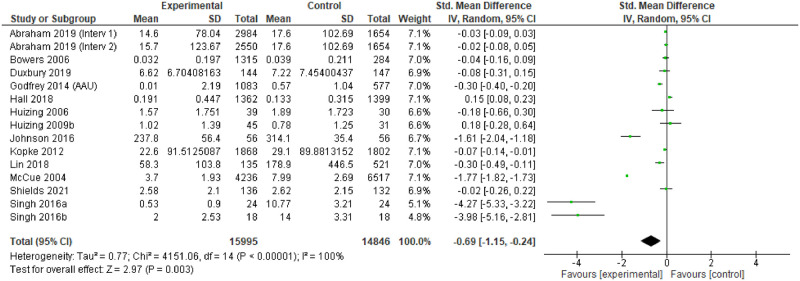

The 14 studies made 15 comparisons. Although two studies presented two comparisons, only one comparison could be included as the other reported no events [188].

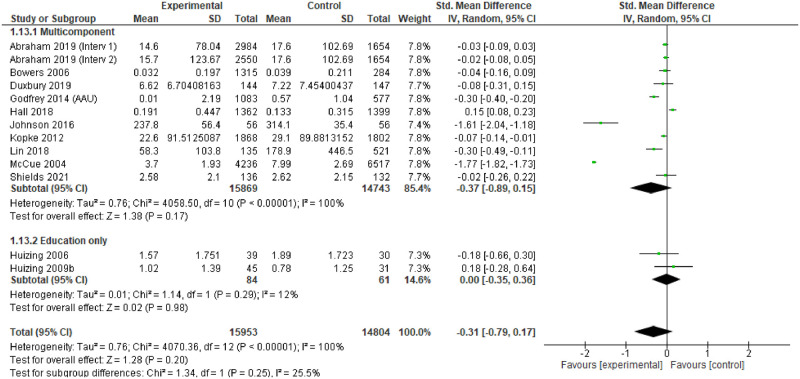

The pooled outcome showed a statistically significant beneficial effect in reducing restraint following the different interventions compared to usual care (SMD -0.69 (95% CI: -1.15; -0.24) (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Effectiveness of interventions on the use of restraint: All included studies.

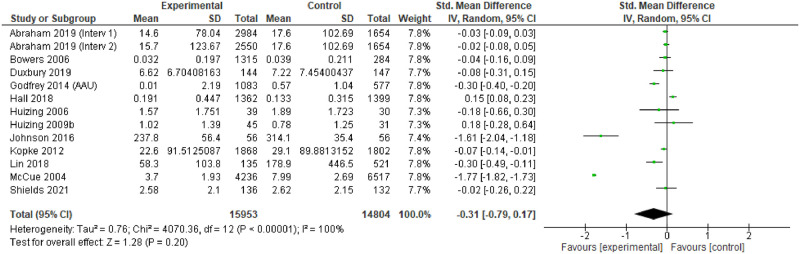

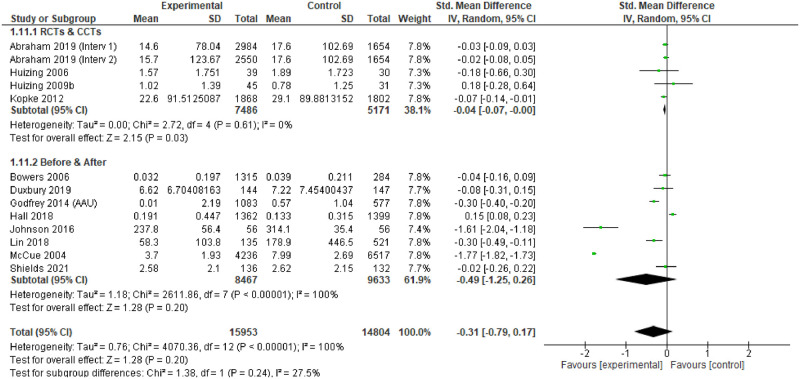

Two studies, which assessed the effects of mindfulness-based positive behaviour support, found markedly strong effects[203, 204]. When these studies were excluded through a sensitivity analysis, the pooled effect was reduced, becoming marginally statistically insignificant (SMD -0.31 (95% CI: -0.79; 0.17)) (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Effectiveness of interventions on the use of restraint, excluding outliers.

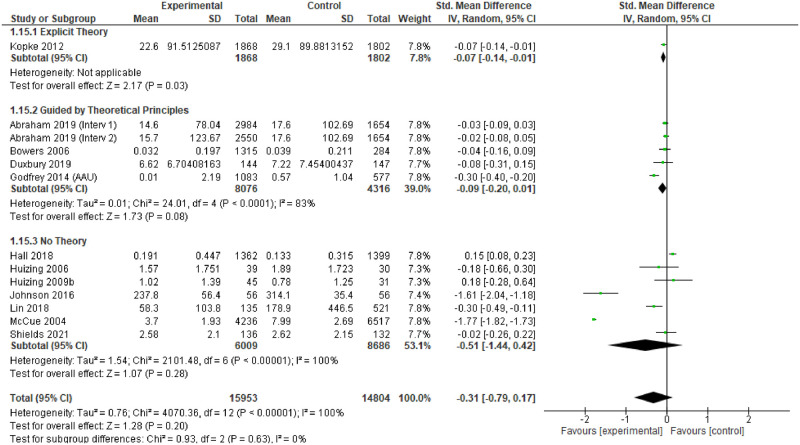

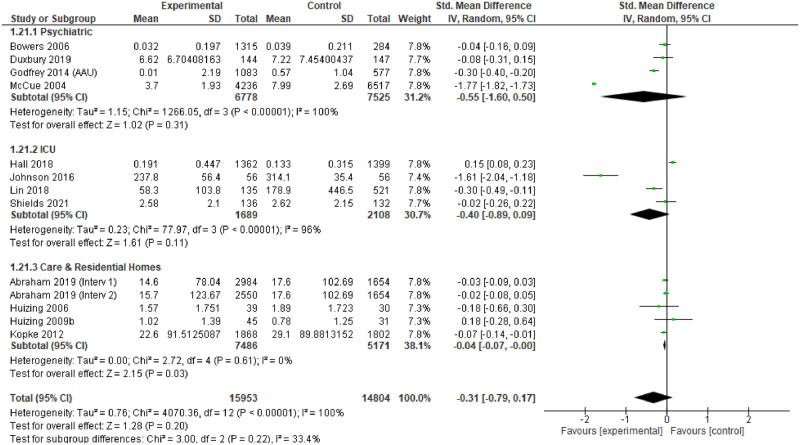

Sub-group analyses were largely inconclusive, reflecting uncertainties in the evidence base. RCTs and CCTs, (providing more robust evidence), reported a small statistically significant benefit from the different interventions when compared with before and after studies (SMD -0.04 (95% CI: -0.07; -0.00)) (Fig 5). A similar small benefit was found from interventions based on explicit theory, but this only comprised one study [177] (SMD -0.07 (95% CI: -0.14; -0.01); from studies with explicit or implicit underpinning theory (4 studies, 5 comparisons); SMD -0.09 (95% CI: -0.20–0.01) (Fig 6); or for interventions used in care and residential homes [155, 172, 174, 177] (SMD -0.04 (95% CI: -0.07; -0.00)) (Fig 7).

Fig 5. Effectiveness of interventions on the use of restraint by study design, excluding outliers.

Fig 6. Effectiveness of interventions with an underpinning theory on the use of restraint, excluding outliers.

Fig 7. Effectiveness of interventions on the use of restraint by setting of care, excluding outliers.

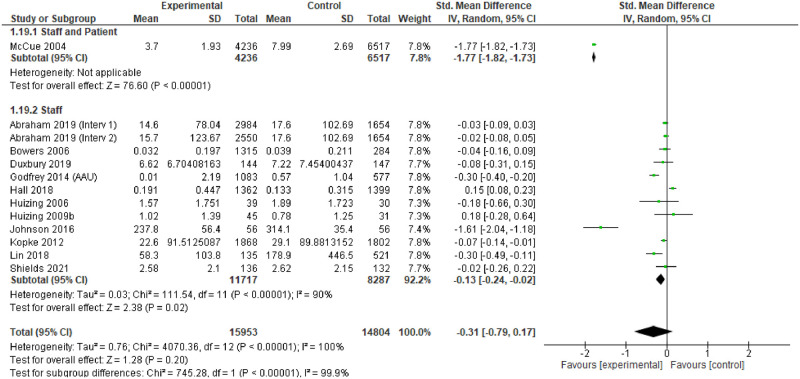

An intervention that involved both staff and patients had a greater benefit than those focused on staff only [179] (SMD -1.77 (95% CI: -1.82; -1.73)) (Fig 8). Multicomponent interventions seemed to have a larger effect than those based on education alone, but this did not reach statistical significance (SMD -0.37 (95% CI: -0.89–0.15) (Fig 9,. The influence of a country’s income could not be assessed as all studies that were suitable for meta-analysis were undertaken in high-income settings.

Fig 8. Effectiveness of interventions on the use of restraint by those receiving the intervention, excluding outliers.

Fig 9. Effectiveness of interventions on the use of restraint by intervention type, excluding outliers.

Heterogeneity affected most of the meta-analyses, despite undertaking sub-group and sensitivity analyses (I2 >90%). Only the sub-group analyses that focused on the RCTs and CCTs, on the education only interventions, and on care and residential home settings reduced the heterogeneity to being unimportant. The occurrence of heterogeneity is unsurprising given the diverse evidence base, where participants, interventions, outcome measures, study designs and setting vary considerably.

Importantly only 14 of the 50 non-maternity controlled studies were included in the meta-analyses. This reflects the lack of data reported in the studies, with many not reporting measures of variability (e.g. standard deviations, confidence intervals), or participant numbers, or outcomes for different groups.

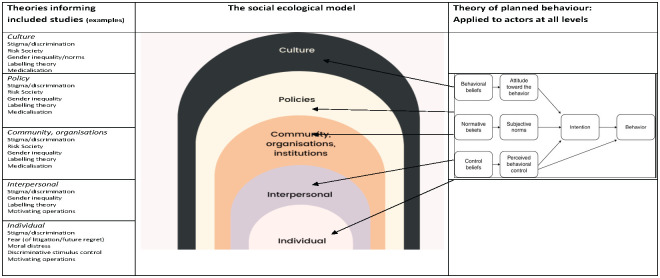

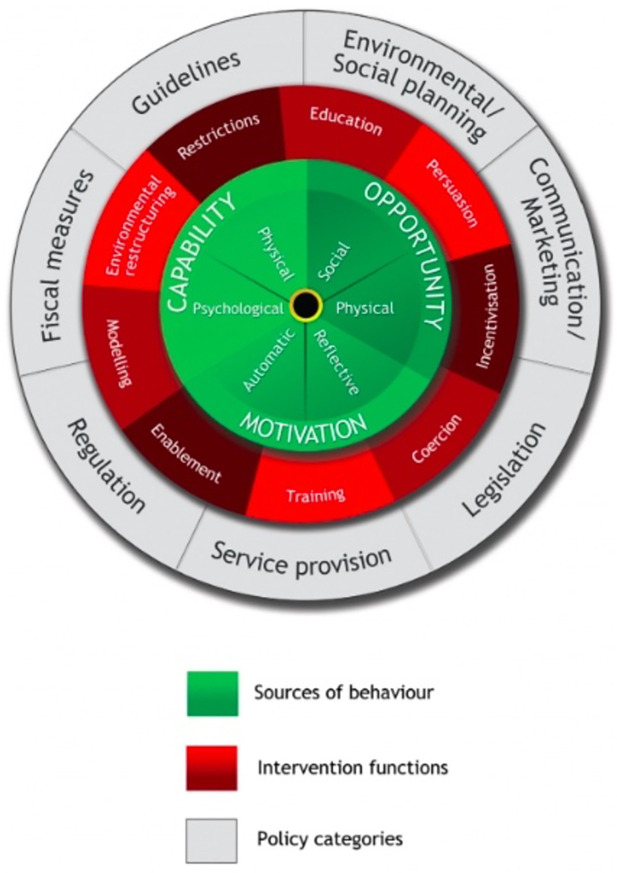

Synthesis

The analysis above indicates that a wide range of implict or explicit theories have been used in studies and papers that address mistreatment, including physical and/or verbal abuse, in health and social care. The theories used tend to focus either on aspects of the health or social care system, or on wider societal and cultural norms, or on the behaviours, norms and attitudes of the individual practitioners working within these systems. Based on these observations, we propose a model that could explain the mechanisms that might trigger and sustain physical and/or verbal abuse (and that therefore could be used for change in future maternity care interventions). The approach is based on an integration of both the social-ecological theory [258, 259] and the theory of planned behaviour [256], to capture both systems and people factors.

We propose that this model, or alternatives that integrate both a systems wide and a human factors approach, might be a useful template for formative research. This could be used to identify mechanisms of effect in settings where disrespectful behavioural norms are proving to be resistant to change, as well as being a vehicle for ensuring that, once identified, any future local intervention can be designed to address and change these negative drivers.

There are many variations of the socio-ecological model in current circulation, applied to a wide range of disciplines and problems. What they all have in common is an understanding that human behaviour occurs in nested layers of the social systems in which people operate. The original model was proposed by Bronfenbrenner in 1977 [258] in the context of child development, with his final version being published in 1994 [259]. Fig 10 summarises the levels that are usually included in socio-ecological models (sometimes also categorised into ‘micro-meso-exo-macro’ domains).

Fig 10. Proposed socio-ecological-behavioural approach linked to example theories from included studies.

The model has an affinity with systems thinking and with complexity theory concepts of inter-connectivity, emergence, self-organisation and self-similarity at different levels of an organism or agency [260]. In other words, systems that are connected across some or all of these levels can tend to express similar characteristics in the component parts at each level. This is important in terms of understanding verbal and physical abuse in maternity care, as it is likely that attitudes, behaviours and norms that are apparent at lower levels of the system are modelled at higher levels of the system. Operating theories located in this review, such as gender norms, stigma and discrimination provide examples of this hypothesis.

Bronfenbrenner himself acknowledged that levels of the system operate in interaction with the people within them. His thinking moved from an emphasis on context towards an increasing recognition of the importance of recognising how far the individual (specifically the developing child, in his work) is in interplay with, and influences, that context. In this reading, the emergence of the cultures and norms, and, therefore the operation of each level of the socio-ecological system can be seen as a function of personal interaction, at least to some extent. This suggests that the analysis of and impacts on human behaviour at the individual/interpersonal level (as many implementation of change strategies are designed to do) misses critical human agency drivers and barriers at the meso-exo-macro level. This might limit the possibility of enacting change effectively, raising the hypothesis that understanding and influencing human behaviour at all levels of the system might be the key to change.

The family of theories that was most often evident in this review (either implicitly or explicitly) was one of the forms of the theory of planned behaviour. First published as the theory of Reasoned Action in 1980 [261] following an earlier paper setting the groundwork [262], the theory has undergone a series of transformations [263] as it has been refined to take into account psychological processes that human beings engage with as they decide whether or not to act in particular ways in specific circumstances. The labelling and composition of the model that results from the theory have varied over time, but the fundamental components relate to (perceived or actual) control over undertaking the behaviour; subjective and social norms (whether people that matter to the individual would approve, and whether the local social norms would support the action); and behavioural attitude (the extent to which performing the behaviour is perceived to be beneficial). The later formulations of the model add a level of intention to each of these three core components.

This iteration of the theory is detailed enough to capture both attitude and intent, while being simple enough to be interpreted in formative research. Implicitly or explicitly, many subsequent change models and theories encompass these concepts of, broadly, what is ‘normal’/supported/enabled in the local context; what is easy for the individual to do; and what gives the individual a sense of benefit.

Despite the apparent utility of both systems and psychological theories in the context of health and social care, they have rarely been synthesised together. While socio-ecological theory is built on human/system interaction at the supra-individual level, this is usually in terms of the person experiencing the system (the child, patient, service user and so on) and not at the level of the people who are creating and sustaining it (staff, managers, policy makers, social influencers, for instance). In 2015 Nilsen identified around 40 frameworks, models and theories used in implementation science [264] most of which either have a primary focus on either systems/ environment, or on human factors. Few recognise that human factors influence all levels of the health and social care system. The assumption seems to be that either ‘the system’ is the issue, with resource limitations or availability and system constraints or freedoms forcing individuals to act in certain ways: or the individuals within the system are the drivers, having freewill to accept or resist institutional and social norms and expectations, including norms of stigma, stereotyping, and the range of theories of discrimination, othering, and exclusion identified in this review.

However, arguably, and as implied by Bronfenbrenner in his later outputs [259], systems are people. Deciding which resources to allocate to ensuring staff are well trained and that services are well-staffed, or that training schools are available, or who has the right to access care, or any of a myriad of other system level barriers and facilitators, are all decisions made by individuals acting on the basis of what they believe to be normal/acceptable to those they value or who have power over them; who make a judgement about what is the most likely (easiest) action or set of actions for a positive outcome; and about the degree of control they have to enact that resource allocation, or to legislate for a certain kind of (non)-discrimination; or to use nudge techniques to create a certain new cultural norm, for instance.

This suggests that interventions that do not take account of both organisational, cultural and political pressures, and the psychological intentions of actors at all system levels (based on their prior prejudices, attitudes and beliefs) will not be able to enact effective shifts in behaviours across the socio-ecological levels. In terms of respectful care, we have modelled this assumption in Fig 10, using examples of some of the explicit or implicit theories located in the review. This is not an exhaustive exercise–the intent is to show that at least some of the theories identified in the review could be mapped to all levels of the model.

Mapping the synthesis to maternity care interventions

We only located two controlled intervention studies in maternity care, published (in three papers [14, 15, 265] since our systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to increase respectful care in 2018 [9]. The Asefa study [14, 15] was before and after, was reported in 2020, and was undertaken in three hospitals in Ethiopia. The intervention was based on a multi-component programme, including training of service providers, putting posters about the right to respectful care in labour rooms, and post-training quality improvement visits. It included measures of physical restraint and of gagging, both of which were reduced by the intervention, though the reduction did not reach statistical significance.

The study undertaken by Mihret [265] was also a before and after study, undertaken in 2020 in one hospital in Ethiopia. It was a multicomponent intervention, focused on both the antenatal and intrapartum period. The authors reported large differences between pre and post study measures, in overall disrespect and abuse, and in physical abuse specifically.

Putting these studies alongside the five studies (six papers) included in the Downe review [266–271] results in seven intervention studies, all undertaken in hospitals in either Ethiopia or Tanzania. Study characteristics and explicit/implicit underlying theories are given in Table 6.

Table 6. Characteristics of published studies of respectful care interventions in maternity services.

(outcomes that improved with the intervention in bold: associated theory papers in italics).

| Author | Design | Focus | Setting | Country | Intervention | Outcome measures+ | Underlying theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abuya 2015 [270] [172] | Before/ after |

Reduction in disrespect/ abuse | 13 maternity facilities | Kenya | Multi-component multi-system multi-site change programme, including policy maker engagement, training in values and attitudes transformation; quality improvement teams; caring for carers; D&A monitoring; mentorship; maternity open days; community workshops; mediation/alternative dispute resolution; Counselling community members who had experienced D&A |

|

Explicit: gender theory/discrimination, structural disrespect Implicit: social engagement, hierarchy, systems theory; socio-ecological theory; behaviour change theories |

| Asefa 2020 [14, 15] | Before/ after |

Reduction in mistreatment | 3 maternity facilities | Ethiopia | 3 day interactive training workshop including presentations, role play, videos and hospital visits, using a manual based on human rights, the law, ethics and continuous quality improvement. Labour ward wall posters with WRA universal rights, and with WHO positive childbirth experience infographics. Post training quality improvement facility visits including checklist based appraisal based on observations, documents and interviews. Gap analysis resulting in escalation of solutions to hospital administrators |

|

Explicit: none Implicit: normalisation theory (of verbal abuse); systems theory; socio-ecological theory; behaviour change theories |

| Brown 2007 [266] | RCT | Increase in labour companions (as a means to respectful care) | 10 maternity facilities | South Africa | Access to the WHO Reproductive Health Library and linked training, plus: an educational intervention to promote childbirth companions, introduction of WHO RHL facilities, including an interactive workbook and workshop; posters and banners encouraging women to bring in a companion; illustrated pamphlets for staff and pregnant women to show how companionship could be promoted locally; a magazine style video on birth companionship including interviews with recent South African mothers and with staff. Encouragement by the research team for senior staff to attend the workshop. Visits by research team every two weeks to discuss progress, and how to overcome obstacles. |

|

Explicit: none Implicit: social support theory |

| Kujawski 2017 [267] | Before/ after |

Reduction in disrespect/abuse | 2 maternity facilities | Tanzania | 1) Participatory process with multiple community, policy and facility stakeholders, designed to create a Client Service Charter built on consensus on norms to foster mutual respect and respectful care. The Charter was then widely disseminated in communities and local health facilities (6 months). 2) Quality Improvement process in one local facility to address D&A as a system-level issue, using plan-do-act type cycles with local staff, resulting in a number of changes at ward and facility level, including provision of curtains to ensure privacy, transparency about stock-outs, running continuous customer satisfaction exit surveys, providing tea for on-shift staff, best-practice sharing with other wards and the regional hospital, counselling staff who showed D&A behaviours, and mutual staff encouragement to exhibit respectful care |

|

Explicit: normalisation theory Implicit: systems theory; socio-ecological theory; behaviour change theories |

| Mihret 2020 [265] | Before/ after |

Reduction in disrespect/ abuse | 1 maternity facility | Ethiopia | Multi-component package across the organisation based on prior qualitative work with a senior multi-disciplinary team |

Overall disrespect and abuse: subscales: (physical abuse, non-consented care, non-confidential care, non-dignified care, discrimination and neglected care) |

None |

| Ratcliffe 2016 [268, 269] [148] | Before/ after |

Reduction in disrespect/ abuse | 1 maternity facility | Tanzania | A three-part step-wise dissemination and participatory process with local stakeholders from the facility, district community, and national representatives, and a multi-stakeholder working group. Two components were developed. The first (May-Oct 2014) was a series of Open Birth Days (antenatal education, communication, and information sessions for women re birth and what would happen to them in hospital, their rights, what they should bring in, open discussions between attendees and staff to build trust, tours of the hospital, including the complaints department; accompanied by posters of the ‘universal rights of childbearing women’, translated into Kiswahili and hung on all the wards, notebook copies sent to all staff, and postcard copies given to all women attending the sessions). The second was a Respectful Care Workshop, held over 6 sessions over 2 days, ending with an agreed action plan agreed by each participating group, based on the WHO Health Workers for Change curriculum. | Measures mostly of changes in knowledge among service users and attitudes providers about D&A, and provider communication and job satisfaction. Service user satisfaction with services and perceptions of quality of care and of respect shown by providers |

Explicit: none Implicit: logic model (called ‘theory of change’ in the text) developed based on knowledge, communication and attitudes; systems theory; socio-ecological theory |

| Umbeli 2011 [271] | Before/ after |

Improving communication during labour | 1 maternity facility | Sudan | Training of registrars, house officers, midwives and data collectors on communication skills, support during childbirth, providing information, and empathy. |

|

Explicit: communication theory Implicit: none |

In general, maternity studies in this area have included multi-component interventions, at various levels of the maternity care system, based on prior development work with key stakeholders. All the included studies report improvements in at least some of their outcomes. The one study that was largely focused on educational interventions alone reduced rates of episiotomy, but did not have a significant effect on overall verbal or physical abuse [266]