Abstract

Obesity is a chronic disease characterised by excess adiposity, which impairs health. The high prevalence of obesity raises the risk of long-term medical complications including type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Several studies have focused on patients with obesity, type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease due to the increased prevalence of diabetic kidney disease. Several randomized controlled trials on sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues, and bariatric surgery in diabetic kidney disease showed renoprotective effects. However, further research is critical to address the treatment of patients with obesity and chronic kidney disease to lessen morbidity.

Key message

Obesity is a driver of chronic kidney disease, and type 2 diabetes, along with obesity, accelerates chronic kidney disease.

Several randomized controlled trials on sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues, and bariatric surgery in diabetic kidney disease demonstrate the improvement of renal outcomes.

There is a need to address the treatment of patients with obesity and CKD to lessen morbidity.

Keywords: Obesity, diabetic kidney disease, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues, bariatric surgery, chronic kidney disease, randomized controlled trial

1. Introduction

Obesity is a chronic disease characterised by excess adiposity, which impairs health [1]. Obesity reduces lifespan and raises the risk of long-term medical complications [2]. The pathogenesis of obesity lies in energy homeostasis disorder, in which the body defends against fat loss through either inherited or acquired mechanisms that cause ‘upward setting’ or ‘resetting’ of the level of body-fat mass [3]. The increasing prevalence of obesity has implications for the risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D), obstructive sleep apnoea, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cancer, osteoarthritis, urinary incontinence [4] and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [5]. Obesity is a major cause of CKD and there is a need to address the treatment of patients with obesity and CKD to lessen its morbidity. Several randomized controlled trials (RCT) showed that weight loss interventions such as bariatric surgery, medications and dietary strategies improve renal outcomes [6–9]. Due to the high prevalence of diabetic kidney disease (DKD), many studies have focused on patients with obesity, T2D and CKD. In this narrative review, we searched PubMed from its inception until March 2023 for the term obesity and chronic kidney disease, limited to English-language articles. We focused on RCTs with renal outcomes from anti-obesity medications such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues (GLP-1a), bariatric surgery and other pharmacotherapies. Evidence derived mainly from randomized clinical trials, meta-analyses and relevant narrative reviews. The aim of this review is to highlight current and ongoing RCTs examining renal outcomes in patients with obesity, T2D and CKD.

2. Obesity as a driver of chronic kidney disease

Obesity and CKD are common to complex disorders with increasing clinical and economic impact on healthcare around the globe. The prevalence of CKD is estimated to be over 10% of adults worldwide, with more than 50% in high-risk subpopulation groups [10]. Population-based observational studies have established a significant association between obesity and the development and progression of CKD [11–14]. A cross-sectional study among South Koreans showed obesity was more prevalent in patients with CKD than those without CKD [11]. The prevalence of obesity with increased visceral adiposity was highest in stage 2 CKD and stage 3a CKD. In a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the combined effects of body mass index (BMI) and metabolic status on CKD risk, individuals with obesity were shown to have a higher risk of CKD compared to metabolically healthy normal-weight individuals, even in the absence of remarkable metabolic abnormalities [15]. Furthermore, obesity and CKD were associated in individuals with and without diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease [16], indicating that obesity may partly mediate CKD risk via mechanisms independent of its effects on T2D and cardiovascular disease risks. Obesity can also directly cause CKD [17–19]. A mendelian randomization (MR) analysis in n = 11,384 East Asians investigated the causal associations of obesity with CKD and arterial stiffness [18]. Using the genetic risk score as the instrumental variable, a causal relationship was shown for each 1-SD increment in BMI with CKD (OR: 2.36;95% CI, 1.11–5.00) and arterial stiffness (OR: 1.71;95% CI, 1.22–2.39). Using 14 single–nucleotide variations individually as instrumental variables, each 1–SD increment in BMI was casually associated with CKD (OR: 2.58;95% CI, 1.39–4.79) and arterial stiffness (OR: 1.87;95% CI, 1.24–2.81) in the inverse–variance weighted analysis and MR–Egger regression demonstrated no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy (both P for intercept >/= 0.34). The causality between obesity and CKD was validated in a 2-sample MR analysis among Europeans (681,275 of Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits and 133,413 of CKD Genetics). The study emphasizes the importance of weight management for primary prevention and control of subclinical vascular diseases. Another study using genetic analyses from 281,228 UK Biobank participants estimated the relevance of waist-to-hip ratio and BMI to CKD prevalence. Zhu et al. revealed that both central (waist-to-hip ratio) and general adiposity (BMI) appear to be independent and substantial causes of CKD, with associations mainly explained by diabetes, blood pressure (BP), and their correlates [19]. Genetic approaches estimate that each 0.06 increase in the waist-to-hip ratio is linked with a 30% increased risk of CKD, and each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI is associated with a 50% increase in CKD risk. Recently, using data from MR studies on over 300,000 participants from UK Biobank, obesity was linked to different kidney disorders across a spectrum of various aetiologies [17]. Additionally, this obesity-CKD link was largely independent of BP and T2D. Furthermore, the signatures of obesity on the human kidney transcriptome, i.e. groups of genes and pathways that may explain the effects of obesity on the kidney, were studied in 467 kidney tissue samples [17].

Obesity increased CKD’s lifetime risk by 25% compared to individuals with a BMI <25 kg/m2. The underlying pathophysiology of obesity-related kidney disease involves several mechanisms. Due to adipose tissue accumulation and infiltration of the kidney, alterations occur in the kidney haemodynamic, leading to increase tubular sodium reabsorption, volume overload/hypertension, and glomerular hyperfiltration, which causes kidney injury (glomerulomegaly, glomerular hyperfiltration, podocyte dysfunction, tubulointerstitial damage and fibrosis) [20].

Increased adiposity also modulates inflammatory adipokines (the cell signalling molecules secreted by adipose tissue) such as leptin, adiponectin, tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α), resistin, visfatin, plasminogen-activator inhibitor and interleukin 6 (IL6). There are several potential mechanisms in the literature explaining the effects of these adipokines on renal function [21]. For example, obesity-augmented leptin secretion promotes hypertension via activation of the sympathetic nervous system, oxidative stress, fatty acid oxidation and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1). Conversely, obesity-related reduction in adiponectin is associated with impaired glucose and fatty acids metabolism and may contribute to albuminuria through alterations in the renal podocyte effacement [22]. The secretion of aldosterone and other angiotensinogen from adipose tissue in obesity further regulates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) leading to further adipocyte differentiation and obesity-related hypertension [23–25]. Furthermore, intracellular accumulation of adipose within the kidney exerts a lipotoxic activity leading to oxidative stress and cell apoptosis [26].

3. How type 2 diabetes, together with obesity, accelerate chronic kidney disease

T2D is an obesity complication and is closely associated with kidney inflammation through different molecular pathways. Insulin resistance increases the risk of CKD progression through glomerular haemodynamic alterations and podocyte function disruption. Insulin acts directly on the podocytes’ insulin receptors involving intracellular AKT/mTOR or glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) signalling [27]. At least three mechanisms in which augmented insulin secretion due to insulin resistance in T2D cause kidney injury. Firstly, insulin promotes oxidative stress within podocytes by activating NADPH oxidase [28]. Secondly, insulin stimulates transforming growth factor (TGF) beta-1 and collagen IV formation, possibly leading to tubulointerstitial fibrosis [29]. Thirdly, in individuals with T2D, insulin changes tubular sodium avidity, which promotes water reabsorption, raises BP and glomerular hyperfiltration and subsequently increases albumin permeability [28]. Overall, T2D contributes to insulin resistance which leads to increased insulin secretion, growth factor release and oxidative stress, and dysregulates the glomerular filtration barrier, which changes the kidney haemodynamic and ultimately causes obesity-related glomerulopathy (ORG) and kidney injury [30].

4. Randomized controlled trials on sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) in diabetic kidney disease

There is a need for interventions with reliable evidence for effectiveness in preventing and/or slowing the progression of CKD. SGLT2i is a group of medications that inhibits renal glucose absorption and promotes glucosuria, resulting in a caloric loss of approximately 300 kcal/day which explains the average 2-3kg weight loss achieved in the clinical trials [31,32]. To date, there is no data on the use of SGLT2i as part of the weight loss strategy in patients with obesity. In the recent guideline, SGLT2i is considered to have an intermediate action in promoting weight loss and is an option in treating patients with obesity and T2D [33]. As obesity, T2D and CKD are closely interlinked, all available trials to date that evaluate the role of SGLT2i in overweight, obesity and renal disease were derived from RCTs involving patients with T2D.

In the Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients (EMPA-REG OUTCOME), 7020 patients with T2D and established CVD were randomized to either empagliflozin 10 mg, 25 mg or placebo daily. At baseline, the glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and BMI were 8% and 30.6 kg/m2 respectively. Patients with a minimum estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30 ml/min/1.73m2 were included, and the median follow-up was 3.1 years. In the main study, the risk of a 3-point major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) was significantly lower in the empagliflozin compared to the placebo group (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 − 0.99; p = 0.04 for superiority) [34]. In the follow-up analysis, there was a significant reduction in weight (2–3 kg in empagliflozin 25 mg) and systolic blood pressure (4–6 mmHg) compared to the placebo group [35]. Moreover, the investigators evaluated the composite microvascular outcome, defined as the first occurrence of initiation of retinal photocoagulation, vitreous haemorrhage, diabetes-related blindness, and incident or worsening of nephropathy. Overall, there was a 38% relative risk reduction in the composite microvascular outcome following empagliflozin compared to placebo. The incident or worsening of nephropathy and the progression to macroalbuminuria were reduced by 39% and 38%, respectively. In comparison, 44% and 55% relative risk reduction in the doubling of serum creatinine levels and initiation of renal replacement therapy were demonstrated in the empagliflozin group compared to the placebo. There was no difference in the incidence of albuminuria between groups [36]. The addition of empagliflozin to the standard care in patients with T2D with high cardiovascular risk was shown to reduce the progression of kidney disease compared to placebo.

These positive findings on renal outcomes were further supported by the follow-on trials of empagliflozin in participants with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF);the EMPEROR-Reduced trial, and participants with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HRpEF);the EMPEROR-Preserved trial. Nearly half of the total participants in EMPEROR-Reduced (n = 3730) and EMPEROR-Preserved (n = 5988) have T2D with a mean eGFR and BMI of 61–62 ml/min/1.73m2 and 28–30 kg/m2. Both trials showed a reduction in the composite primary outcome, 25% in EMPEROR-Reduced (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65 − 0.86;p < 0.001) and 21% in EMPEROR-Preserved (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.69 − 0.90;p < 0.001). The rate of eGFR decline in the EMPEROR-Reduced was slower in the empagliflozin (–0.55 ml/min/1.73m2/year) compared to the placebo group (–2.28 ml/min/1.73m2/year) with a between-group difference in slope of 1.73 ml/min/1.73m2/year (95% CI 1.1 − 2.37;p < 0.001) [37]. Similarly, in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial, the rate of eGFR decline was also slower in the empagliflozin (–1.25 ml/min/1.73m2/year) compared to the placebo group (–2.62 ml/min/1.73m2/year) with a between-group difference in slope of 1.36 ml/min/1.73m2/year (95% CI 1.06 − 1.66;p < 0.001) [38].

The role of empagliflozin in patients with CKD was further investigated in the EMPA-KIDNEY trial. A total of 6609 patients with multiple causes of CKD and a wide range of eGFR from at least 20 ml/min/1.73m2 with a minimum urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) of 200 mg/g were randomly assigned to empagliflozin 10 mg daily or placebo for a median of 24 months, with a composite progression of kidney disease as the primary outcome. This was defined as a composite of end-stage kidney disease, a sustained decrease in eGFR to less than 10 ml/min/1.73m2, a sustained reduction in eGFR ≥40% from baseline, or death from renal or CV cause. There were 1525 (46.2%) and 1515 (45.8%) patients with diabetes, with a mean eGFR of 37.4 and 37.3 ml/min/1.73m2, a BMI of 29.7 and 29.8 kg/m2, and a median urine ACR of 331 and 327 mg/g in the empagliflozin and placebo group respectively. The primary outcome was reduced by 28% in the empagliflozin group (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.64 − 0.82;p < 0.001) compared to placebo, irrespective of diabetes status, across subgroups of eGFR ranges. The proportion of risk reduction was significant among patients with the highest urinary ACR >300 mg/g. There was a 14% reduction in hospitalisation rate from any cause in the empagliflozin group (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78 − 0.95;p-0.003) with no difference in the composite outcome of hospitalization for heart failure or death from CV causes between both groups. The between-group difference in the eGFR slope was 0.75 ml/min/1.73m2/year (95% CI 0.54 − 0.96) in favour of empagliflozin. There was a small improvement in weight (–0.9 kg), systolic (–2.6 mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure (0.5 mmHg), favouring empagliflozin [39].

Through the CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study (CANVAS), data from 10,142 participants from CANVAS and CANVAS-R (renal) trials were integrated to evaluate the effects of canagliflozin on CV and renal outcomes in participants with T2D and high CV risk. This was defined as either age ≥30 years old with a history of symptomatic atherosclerotic CV disease or ≥50 years old with two or more risk factors for CV disease. eGFR at entry was >30 ml/min/1.73m2 and the mean follow-up was 188.2 weeks. Patients were randomised to either canagliflozin 100 mg, 300 mg or placebo (CANVAS trial) or canagliflozin 100 mg with the option to increase to 300 mg (week 13) or placebo in the CANVAS-R trial. A composite of death from CV causes, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke, was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes included death from any cause, death from CV causes, albuminuria progression and the composite of death from CV causes and hospitalization from heart failure. A composite renal outcome included a 40% reduction in eGFR, requirement of renal replacement therapy or death from any renal causes. Mean BMI and eGFR at baseline were 32.0 kg/m2 and 76.5 ml/min/1.73m2 respectively. Median urine ACR was 12.3 mg/g, with 22.6% and 7.6% having microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria, respectively. There was a 14% reduction in the primary outcome in the canagliflozin group compared to the placebo (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 − 0.97; p < 0.001). Progression of albuminuria was reduced by 27% (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.67 − 0.79) with a 40% reduction in the composite renal outcome (HR 0.6, 95% CI 0.47 − 0.77) in the canagliflozin group compared to placebo. The mean weight, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) differences in the canagliflozin group compared to placebo, were −1.6 kg, −3.9 mmHg and −1.39 mmHg, respectively [40].

The Evaluation of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Participants with Diabetic Nephropathy (CREDENCE trial) was designed to evaluate the effects of canagliflozin in patients with T2D and CKD with specific renal endpoints. A total of 4401 participants with T2D with CKD (eGFR 30–90 ml/min/1.73m2) and albuminuria (urine ACR >300 to 5000 mg/g) on a stable dose of renin-angiotensin system blockade were randomized to canagliflozin 100 mg or placebo. The primary outcome was a composite of end-stage renal disease, a doubling of creatinine level, or death from renal or CV causes. The definition of end-stage renal disease included a requirement for dialysis, transplantation, or a sustained eGFR <15 ml/min/1.73m2. The mean baseline HbA1c, eGFR, and BMI were 8.3%, 56.2 ml/min/1.73m2, and 31.3 kg/m2 respectively, while the median urine ACR was 927 mg/g. After a median follow-up of 2.62 years, the primary outcome was reduced by 30% in the canagliflozin group (HR 0.7, 95% CI 0.59 − 0.82, p = 0.00001) compared to placebo, and this was consistent across regions and prespecified subgroups. The renal-specific composite outcome (end-stage renal disease, doubling of serum creatinine or renal-related death) was reduced by 34% (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.53 − 0.81, p < 0.001) while end-stage kidney disease (initiation of dialysis for at least 30 days, kidney transplantation, or eGFR <15 ml/min/1.73m2 for at least 30 days) was reduced by 32% (HR 0.68, CI 0.54 − 0.86, p = 0.002) in the canagliflozin group. There was a 31% reduction in the composite of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 − 0.83, p < 0.001), a 20% reduction in cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (HR 0.8, 95% CI 0.67 − 0.95, p = 0.01), and a 39% reduction in hospitalization for heart failure (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.47 − 0.8, p < 0.001) in canagliflozin group compared to placebo. SBP and weight were reduced by 3.3 mmHg (95% CI 2.73 − 3.87) and 0.8 kg (95% CI 0.69 − 0.92), respectively, while the geometric mean of urine ACR was reduced by 31% (95% CI 26 to 35) in favour of canagliflozin [41].

Like the CANVAS program, the Dapagliflozin Effect on Cardiovascular Events (DECLARE-TIMI 58) trial involved a large number of patients (n = 17,160) with T2D randomised to either dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo, with a follow-up period of 4.2 years. Participants involved were either individuals with established atherosclerotic CV disease (40.6%, n = 6974) or had multiple risk factors for it (59.4%, n = 10,186). A MACE composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or ischaemic stroke was the primary safety outcome. MACE and a composite of CV death or hospitalization for heart failure were the two primary efficacy outcomes. The renal composite outcome included a sustained decrease of 40% or more in eGFR, new end-stage renal disease or death from renal or CV causes. The mean baseline HbA1c and BMI were 8.3% and 32.0 kg/m2 respectively. The median diabetes duration was 11 years, and 10% of participants had a diagnosis of heart failure. The baseline mean eGFR was 85.2 ml/min/1.73m2, with 45% and 7% having eGFR between 60–90 ml/min/1.73m2 and < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 respectively. There was a 17% reduction in the composite CV death or hospitalization for heart failure in the dapagliflozin group (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.73 − 0.95, p = 0.005), primarily driven by a lower rate of heart failure hospitalization (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.61 − 0.88). There were no differences in the event of CV death (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.82 − 1.17) or MACE (HR 0.93, CI 0.84 − 1.03, p = 0.17) between dapagliflozin and placebo. The following results within this study were hypothesis generating rather than hypothesis testing. The Dapagliflozin group had a lower incidence of the renal composite outcome by 24% (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.67 − 0.87), and there was no difference in the rate of death from any causes between groups (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.82 − 1.04). The least-squares mean difference in weight, SBP and DBP was 1.8 kg, 2.7 mmHg and 0.7 mmHg, favouring dapagliflozin [42].

Similar to the EMPEROR trials, the role of dapagliflozin was evaluated against placebo, for a median of 18.2 months, in participants with HFrEF with and without T2D in the Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction (DAPA-HF) trial (n = 4744). Nearly 42% had T2D, with a baseline BMI and eGFR of 28 kg/m2 and 66 ml/min/1.73m2 respectively. In each group 41% of participants had eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2. While there was a reduction in the composite primary outcome (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.65 − 0.85; p < 0.001) and key composite secondary outcome (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.65 − 0.85; p < 0.001), there was no difference in the composite renal outcome (HR 0.71, CI 0.44 − 1.16) following dapagliflozin [43].

To evaluate the effect of dapagliflozin in patients with CKD, 4304 participants with or without diabetes, with eGFR of 25–75 ml/min/1.73m2 and urine ACR of 200 to 5000 mg/g, were randomized to either dapagliflozin 10 mg or placebo in the DAPA-CKD trial. The primary composite renal outcome included an eGFR decline of at least 50%, the onset of end-stage kidney disease or death from a renal or cardiovascular cause. The 1st secondary renal outcome was a composite of sustained decline in eGFR of at least 50%, end-stage kidney disease or death from renal causes. The 2nd secondary outcome was a composite of death from CV causes or hospitalization for heart failure, while the final secondary outcome was death from any causes. The baseline BMI in each group was 29.5 kg/m2 and 67.5% of participants in each group had T2D. The mean eGFR at baseline was 43.1 ml/min/1.73m2 with 14.5% of participants having eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2. The median urinary ACR was 949 mg/g, while 48.7% (dapagliflozin) and 47.9% (placebo) of participants had a baseline urinary ACR > 1000 mg/g. This trial was stopped early by an independent data monitoring committee, at 2.4 years, due to the demonstration of apparent efficacy. The primary renal composite outcome was reduced by 39% in the dapagliflozin group (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.51 − 0.72, p < 0.001) with an NNT of 19 to prevent one primary outcome. This benefit was consistent across all subgroups, including in patients with or without T2D. The 1st secondary renal outcome was reduced by 44% (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.45 − 0.68, p < 0.001), while the 2nd and final secondary outcome was decreased by 29% (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55 − 0.92, p = 0.009) and 31% (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53 − 0.88, p = 0.004) respectively, in favour of dapagliflozin [44].

In the Evaluation of Ertugliflozin Efficacy and Safety Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (VERTIS CV), 8246 participants with T2D and established CV diseases were randomized to either ertugliflozin 5 mg, 15 mg or placebo for 3.5 years. A composite of death from CV causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke, was the primary outcome. The 1st secondary outcome was a composite of death from CV causes or heart failure hospitalisation and death from CV causes. In contrast, the 2nd secondary outcome was a composite of doubling serum creatinine, renal replacement therapy or death from renal causes. At baseline, the mean BMI and eGFR were 32 kg/m2 and 76 ml/min/1.73m2, while 22% of participants in each group had eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2. There was no significant reduction in the primary outcome (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85 − 1.11), 1st secondary outcome (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.75 − 1.03) and the composite renal outcome (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.63 − 1.04) in the pooled ertugliflozin group compared to placebo [45].

To evaluate the efficacy of sotagliflozin in preventing CV events in patients with T2D and CKD with and without albuminuria, 10,584 participants were randomized to either sotagliflozin 200 mg daily (with an increase to 400 mg if tolerated) or placebo in the Effect of Sotagliflozin on Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Participants with Type 2 Diabetes and Moderate Renal Impairment Who Are at Cardiovascular Risk (SCORED) trial. This study was discontinued early due to loss of funding, and consequently, the endpoints underwent several changes. The composite of the total number of deaths from CV causes, hospitalizations for HF and urgent visits for HF was the composite primary endpoint. The specific renal secondary endpoint was a composite of a sustained decrease of >50% eGFR for ≥ 30 days, long-term dialysis, renal transplantation, or a sustained eGFR < 15 ml/min/1.73m2 for ≥ 30 days. At baseline, the mean BMI, median eGFR and urinary ACR were 31.8 kg/m2, 44.5 ml/min/1.73m2 and 74 mg/g, respectively. After a median follow-up of 16 months, the primary outcome was reduced by 26% (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.63 − 0.88, p < 0.001) in the sotagliflozin group compared to the placebo group, while no difference was seen in the secondary renal outcome (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.46 − 1.08) [46].

In a recent collaborative meta-analysis, all large placebo-controlled clinical trials evaluating the effects of SGLT2i in participants with CKD, heart failure and T2D were included. The analyses aimed to assess the effects of SGLT2i on kidney disease progression, acute kidney injury (AKI) and other outcomes in patients with and without diabetes. The definition of kidney disease progression includes a sustained decrease in eGFR (>50%), end-stage renal disease, a sustained low eGFR (<15 ml/min/1.73m2 or <10 ml/min/1.73m2), or kidney failure resulting in death. AKI, a composite of hospitalisation for heart failure or CV death, CV and non-CV death and all-cause mortality were also investigated. Safety outcomes, including ketoacidosis, lower limb amputation, urinary tract infection (UTI), mycotic genital infections, hypoglycaemia, and bone fractures, were also evaluated. There were 13 trials included, with a total of 90,409 participants (82.7% with T2D). The range of trial baseline eGFR levels were 74–85 ml/min/1.73m2 (T2D with high atherosclerotic CV disease trials), 51–66 ml/min/1.73m2 (heart failure trials) and 37–56 ml/min/1.73m2 (CKD trials). SGLT2i reduces the risk of kidney disease progression by 37% (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.58 –0.69), with similar benefits seen in patients with (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.56–0.68) and without diabetes (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 –0.82), compared to placebo. Data derived from the CKD trials demonstrated a 38% (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.56 –0.69) reduction in kidney disease progression irrespective of the aetiology of CKD. In this analysis, SGLT2i also reduces the risk of AKI by 23% (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.7–0.84), with a similar reduction in patients with (0.79, 95% CI 0.72 –0.88) and without diabetes (0.66, 95% CI 0.54–0.81). The composite outcome of CV death or hospitalisation for heart failure was reduced by 23% (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.74 –0.81), while the risk of CV death was reduced by 14% (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.81 –0.92) in favour of SGLT2i, irrespective of diabetes status. In this study, SGLT2i did not have any impact in reducing the risk of non-CV death compared to the placebo (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.88 –1.02). There was a doubling in the risk of ketoacidosis (RR 2.12, 95% CI 1.49–3.04), with a 15% increased risk of lower limb amputation (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02–1.30) in patients with diabetes allocated SGLT2i compared to placebo. Overall, SGLT2i resulted in a 3-fold increase in mycotic genital infections (RR 3.57, 95% CI 3.14–4.06), an 8% increase in UTI (RR 1.08, 95% 1.02–1.15) and a trend for bone fractures (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.99–1.14) compared to placebo. With all the trials to date, the absolute benefit of SGLT2i outweighs the potential harm. It is estimated that treating 1000 patients with diabetes and CKD using SGLT2i for one year will result in 11 fewer patients developing kidney disease progression, four fewer patients with AKI, 11 fewer patients with CV death or hospitalisation for heart failure and only one potential ketoacidosis and one lower limb amputations [47].

All evidence to date demonstrates the benefit of SGLT2i as part of optimising diabetes care and CV outcomes, exacerbation of heart failure and hospitalization. SGLT2i plays a central role as a disease-modifying agent in patients with CKD, irrespective of diabetes status and the aetiology of kidney disease. While there is an increase in the relative risk of adverse reactions (mycotic genital infection, UTI, and lower limb amputation), the absolute benefit currently outweighs the risk. Several meta-analyses involving the above trials have demonstrated a positive weight loss outcome with SGLT2i compared to placebo [48,49]. However, to date, there are no published trials of SGLT2i specifically in patients with obesity.

5. Randomized controlled trials on glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues in diabetic kidney disease

GLP-1 analogue (GLP-1a) is licensed in the management of T2D and/or obesity. It promotes glucose-dependent insulin secretion and glucagon suppression, improves satiety, and reduces gastric motility and appetite, with an intermediate to a high level of weight loss outcome [33,50]. The SCALE and STEP clinical trials provided evidence of the use of high-dose liraglutide (3.0 mg) and semaglutide (2.4 mg) in participants living with obesity either with and without diabetes or pre-diabetes. These trials vary in duration, aims, and comparators and none included renal outcome as a primary endpoint [51]. To date, the renoprotective effects of GLP1 analogue in obesity and renal disease are derived from RCTs involving patients with T2D.

The Evaluation of Lixisenatide in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ELIXA) trial examined the CV safety outcomes of lixisenatide in participants with T2D and recent acute coronary syndrome (n = 6068). Participants were randomized to either lixisenatide (10 to 20 mcg daily) or placebo with a median of 25 months follow-up. The mean HbA1c, BMI and eGFR at baseline were 7.6%, 30.1 kg/m2 and 76 ml/min/1.73m2 respectively. There was no difference in the occurrence of the composite primary outcome event (CV death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina) in the lixisenatide group compared to placebo (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.89– 1.17). HbA1c and BMI were better in the lixisenatide group compared to the placebo, with an average between-group difference of –0.27% and –0.7 kg (p < 0.001 for both), respectively [52]. To evaluate the possible effect of lixisenatide on the renal outcome, a follow-up exploratory analysis examined the percentage change in urinary ACR and eGFR based on the baseline albuminuria status in both groups. Normo-, micro- and macroalbuminuria were identified in 74%, 19% and 7% of participants. The macroalbuminuria group significantly reduced urinary ACR with lixisenatide (–39.2%, p = 0.07) compared to the placebo. No eGFR changes in treatment groups in any urinary ACR group. Lixisenatide was associated with a reduction in new-onset macroalbuminuria (HR 0.81), adjusted for both baseline HbA1c (p = 0.04) and on-trial HbA1c (p = 0.05) [53].

The Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results (LEADER) trial involved participants with T2D and high CV risk, with a total of 9340 participants randomized to either liraglutide (1.8 mg/day or maximum tolerated dose) or placebo for a median of 3.8 years. The baseline HbA1c was 8.7%, with 25% of participants having CKD stage 3-4. There was a 13% reduction in the primary composite outcome (death from CV causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) in the liraglutide group compared to placebo (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78–0.97, p < 0.001). The secondary composite renal or retinal microvascular outcome was also reduced in the liraglutide group (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.73–0.97, p = 0.02), predominantly driven by a lower rate of nephropathy (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.67–0.92, p = 0.003). The liraglutide group had a mean difference in HbA1c of –0.4% and 2.3 kg more weight loss than the placebo [54]. In a secondary analysis of this trial, the renal outcome was defined as a composite of new-onset persistent macroalbuminuria, doubling of creatinine, end-stage renal disease or death due to renal disease. At baseline, the mean eGFR was 80 ml/min/1.73m2, with 20.7% having eGFR of 30–59 ml/min/1.73m2 and 2.4% having eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2. Microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria were identified in 26.3% and 10.5% of participants, respectively. The composite renal outcome was reduced by 22% in the liraglutide group (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.67–0.92, p = 0.003), predominantly driven by a 26% reduction in the new onset macroalbuminuria (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.6–0.91, p = 0.004) [55].

In the Semaglutide in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes (SUSTAIN-6) trial, 3297 participants with high CV risk T2D were randomized to either semaglutide (0.5 mg or 1.0 mg) or placebo for 104 weeks. At baseline, 83% of participants had established CV disease and CKD stage 3 or higher, while 10.7% had CKD only. The mean diabetes duration, HbA1c and BMI were 13.9 years, 8.7% and 33.0 kg/m2 respectively. There was a 26% reduction in the primary outcome (composite of CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) in the semaglutide group compared to placebo (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.58– 0.95, p < 0.001). There was also a 36% reduction in the secondary renal outcome (new or worsening nephropathy) (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.46– 0.88, p = 0.005), but a 76% increase in the onset of diabetes retinopathy (HR 1.76, 95% CI 1.11–2.78, p = 0.02) in the semaglutide group. Compared to placebo, the mean HbA1c and weight differences in the semaglutide group were –0.7% (semaglutide 0.5 mg), –1.0% (semaglutide 1.0 mg), –2.9 kg (semaglutide 0.5 mg) and –4.3 kg (semaglutide 1.0 mg) respectively [56].

The Exenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering Trial (EXSCEL) examined the CV effects of once-weekly exenatide (2.0 mg) versus placebo in 14,752 participants with T2D with or without CV disease over a median of 3.2 years. At baseline, the median diabetes duration and HbA1c were 12.0 years and 8.0%. The mean BMI and eGFR were 32 kg/m2 and 76 ml/min/1.73 m2. There was no difference in the primary composite outcome (death from CV causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) in the exenatide group vs placebo (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.83– 1.0). The mean difference in HbA1c and weight was –0.53% and –1.27 kg, favouring exenatide [57]. A post hoc analysis examined the effects of once-weekly exenatide on the eGFR slope and the change in urinary ACR in a subset of EXSCEL participants. There were 3503 and 2828 participants with eGFR and urinary ACR data available. Once weekly exenatide improved the eGFR slope in participants with a baseline urinary ACR > 100 mg/g (0.79 ml/min/1.73m2/year (95% CI 0.24–1.34)) and a baseline urinary ACR >200 mg/g (1.32 ml/min/1.73m2/year (95% CI 0.57–2.06)). Urinary ACRs were also reduced by 28.2%, 22.5% and 34.5% in the subgroup baseline urinary ACR > 30 mg/g, >100 mg/g and >200 mg/g following once-weekly exenatide. In this analysis, once weekly exenatide reduces urinary ACR and improves eGFR slope in participants with T2D with higher baseline urinary ACR [58].

Participants with T2D, with or without CV disease, were randomized to either weekly dulaglutide 1.5 mg or placebo for a median of 5.4 years as part of the CV trial for dulaglutide in the Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND) trial (n = 9901). The primary composite outcome includes nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or death from CV causes (including unknown causes). There were seven secondary outcomes, including a composite microvascular outcome (diabetes retinopathy) and renal outcomes. The baseline median diabetes duration, HbA1c and eGFR were 9.5 years, 7.2% and 74.9 ml/min/1.73 m2 respectively, while the mean BMI was 32.3 kg/m2. A total of 7.9% of participants had macroalbuminuria at baseline. There was a 12% reduction in the primary outcome in the dulaglutide group compared to the placebo (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.79– 0.99, p = 0.026). A 13% reduction in the composite microvascular outcome in the dulaglutide group (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.79– 0.95, p = 0.002), predominantly driven by the 15% reduction (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.77–0.93, p = 0.0004) in the renal outcomes (defined as development of urinary ACR >33.9 mg/mmol, a sustained ≥ 30% decline in eGFR, or chronic renal replacement therapy) was revealed. The least-square mean (LSM) HbA1c, weight and BMI were –0.61%, –1.46 kg and –0.53 kg/m2, in favour of dulaglutide [59]. A further exploratory analysis was conducted to evaluate the effects of dulaglutide on the renal outcome in the REWIND trial. The largest component of reduction in the renal outcome came from the decrease in the new onset macroalbuminuria (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.68– 0.87, p < 0.0001) rather than the sustained decline in eGFR (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.78–1.01, p = 0.06) or chronic renal replacement therapy (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.39–1.44, p = 0.39) [60].

To evaluate the CV and renal outcomes of efpeglenatide, 4076 participants with T2D and CV disease or current kidney disease were randomized to weekly efpeglenatide (4 mg or 6 mg) vs placebo for a median of 1.81 years (AMPLITUDE-O trial). The primary composite outcome was the first major MACE. In contrast, one of the secondary outcomes was a composite renal outcome (defined as incident macroalbuminuria, increase in urinary ACR ≥ 30% from baseline, a sustained > 40% decrease in eGFR, renal replacement therapy, and a sustained eGFR < 15 ml/min/1.73m2). At baseline, 89.6% had a history of CV disease, 31.6% had eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2, and 21.8% had both CV disease and low eGFR. The baseline mean BMI, eGFR and median urinary ACR were 33 kg/m2, 72 ml/min/1.73m2 and 28.3 mg/g, respectively. There was a 27% reduction in the primary MACE outcome (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58–0.92, p < 0.001) and a 32% reduction in the secondary composite renal outcome (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.57– 0.79, p < 0.001) in the efpeglenatide group compared to placebo, independent of the baseline use of SGLT2i, metformin and baseline eGFR. The LSM for HbA1c, BMI and weight were –1.24%, –0.9 kg/m2 and –2.6 kg favouring the efpeglenatide group [61].

In the most recent meta-analysis of published RCTs, 8 out of 98 articles fulfilled the pre-specified criteria to evaluate the benefit or risks of GLP-1a in cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in participants with T2D (n = 60,080). Overall, all-cause mortality was reduced by 12% (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.82– 0.94, p = 0.0001) with GLP-1a compared to placebo. The composite renal outcome (development of macroalbuminuria, doubling serum creatinine, or at least 40% decline in eGFR, renal replacement therapy, or death due to renal disease) was reduced by 21% (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.73–0.87, p < 0.0001). The worsening renal function outcome was significantly reduced by 18% (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.69– 0.98, p = 0.03) following sensitivity analysis, where the ELIXA trial was omitted as it was restricted to participants with acute coronary syndrome. There was no increase in the risk of hypoglycaemia, worsening retinopathy or pancreatic side effects following GLP-1a therapy [62].

The dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1a, tirzepatide, was shown to reduce HbA1c and weight in patients with T2D in the Tirzepatide versus insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes and increased cardiovascular risk (SURPASS-4) trial [63]. Recently, a post-hoc analysis was performed to evaluate the rates of eGFR decline, the urinary ACR and the kidney composite outcome in participants with T2D who were randomized to either once weekly tirzepatide (5, 10 or 15 mg) or titrated insulin glargine. A total of 2002 participants with T2D and established CV disease or at a high risk of CV disease had a median treatment duration of 85 weeks. The baseline mean eGFR and median urinary ACR were 81.3 ml/min/1.73m2 and 15 mg/g, respectively. The mean eGFR slope was lower for tirzepatide compared to the insulin group at –1.4 ml/min/1.73m2/year compared to –3.6 ml/min/1.73m2/year respectively (between-group difference of 2.2, 95% CI 1.6– 2.8, p < 0.05). The mean percentage change in urinary ACR was lower in the tirzepatide group (-4.4%) compared to the insulin group (+56.7%) with a between-group difference of –39.0% (95% CI –50.6 to –24.6, p < 0.0001). There was a 57% reduction in the worsening of urinary ACR stages in the tirzepatide group compared to the insulin glargine group (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.27– 0.71, p = 0.0008). The risk of reaching the composite renal outcome was reduced by 42% (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43– 0.8, p = 0.0008), predominantly driven by the reduction in the new onset macroalbuminuria component [64].

To date, GLP-1a or GLP-1a/GIP-based therapies provide vast evidence in the pharmacotherapy of obesity. There are several ongoing CVO trials involving GLP-1a or GLP-1a/GIP which may provide further evidence of the renal outcome. The Semaglutide Effects on Heart Disease and Stroke in Patients With Overweight or Obesity (SELECT) trial included 17,500 participants with overweight or obesity with established CVD randomized to either semaglutide 2.4 mg or placebo. This study is due to be completed in September 2023 [65]. The SURPASS CVOT (Study of Tirzepatide Compared With Dulaglutide on Major Cardiovascular Events in Participants With Type 2 Diabetes) trial included 13,299 participants with overweight or obesity with T2D and established CVD, randomized to either tirzepatide or dulaglutide weekly. This study is due to be completed in October 2024 [66]. The SURMOUNT-MMO (A Study of Tirzepatide on the Reduction on Morbidity and Mortality in Adults With Obesity) trial will include 15,000 participants with obesity and established or at risk of CVD. Participants will be randomized to either tirzepatide or placebo. The primary outcome within the following 5 years is the first occurrence of any component of composite CV outcome. This study is currently in the recruitment phase [67]. In these 3 trials, renal endpoints are included as part of the secondary outcomes in addition to the main primary outcome of first composite CV death, non-fatal MI and non-fatal stroke. Finally, the SUMMIT (A Study of Tirzepatide in Participants With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Obesity) trial aims to recruit 700 participants with obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, randomized to either tirzepatide or placebo. The primary outcome is a hierarchical composite of all-cause mortality, heart failure events, 6-minutes’ walk test distance and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score category. The study is due to be completed in July 2024 [68]. Renal endpoints are not part of this study outcome, however, participants with eGFR between 15 to 75 ml/min/1.73m2 will be included.

In conclusion, evidence supports the benefit of GLP-1a in reducing CV and renal outcomes in patients with T2D linked with a previous history or at high risk of CV disease, with minimal effects on hypoglycaemia, retinopathy or pancreatic adverse events. Evidence also showed that GLP-1a contributes to more weight loss than SGLT2i, with an additional positive renal outcome. However, SGLT2i contributes to more positive renal outcomes in patients with T2D and obesity, with a smaller weight loss compared to GLP-1a.

6. Randomized controlled trials of bariatric surgery in diabetic kidney disease

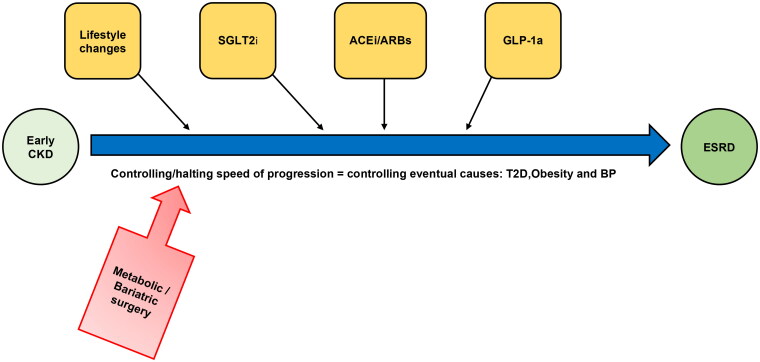

Bariatric surgery is the most effective and sustained weight loss procedure that may regress or diminish obesity-related complications such as cardiopulmonary disease and T2D [4], with T2D as the leading cause of CKD [69]. Figure 1 shows a simplified management pathway for obesity and CKD in which bariatric surgery can be employed in the early stage of CKD. Mounting epidemiological evidence showed that bariatric surgery has renoprotective effects on diabetic kidney disease (DKD) [70]. However, data from randomized trials are limited. Recently, emerging RCTs revealed that bariatric surgery reduces the incidence of albuminuria and slows CKD progression over extended follow-up, and therefore may have a potential complementary role to medical treatment in managing DKD.

Figure 1.

A simplified management pathway for obesity and CKD in which bariatric surgery can be employed in the early stage of CKD. SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors;ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor;ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker;GLP-1a, glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues; CKD, chronic kidney disease;T2D, type 2 diabetes;BP, blood pressure;ESRD, end-stage renal failure.

Schauer et al. conducted the Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently (STAMPEDE) trial randomizing patients with obesity and T2D (n = 150) to intensive medical therapy alone, intensive medical therapy plus Roux-en-Y-gastric bypass (RYGB), or intensive medical therapy plus sleeve gastrectomy (SG) in a 5-year follow-up study. The primary outcome was glycaemic control, while the prespecified secondary endpoint included kidney outcomes. At five years, the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (uACR), measured in milligrams of albumin to grams of creatinine, had decreased significantly from baseline in the SG group (p < 0.001) and was considerably lower in the SG group than in the medical therapy group (p < 0.001). There was no significant change from baseline in albuminuria rates in any group at five years but there were within-group reductions in serum creatinine and eGFR observed in the two surgical arms.

In the Microvascular Outcomes after Metabolic Surgery (MOMS) trial, a total of 100 patients with T2D, obesity and CKD were randomized to best medical treatment (n = 49) versus RYGB (n = 51) [6]. The primary outcome was albuminuria remission (uACR < 30 mg/g), while secondary outcomes included CKD remission rate and absolute change in uACR. The 2-year data revealed that RYGB was more effective than the best medical treatment for achieving albuminuria remission and early-stage CKD in patients with DKD and obesity (BMI 30-35 kg/m2). Subsequently, MOMS 5-year data showed that albuminuria remission was not statistically different between best medical treatment versus RYGB in the T2D, early CKD and Class 1 obesity cohort [71]. Although diabetic kidney disease remission did not persist after five years follow up, RYGB improved glycaemia, diastolic blood pressure, lipids, body weight, and quality of life. The long-term control of these risk factors may halt the progression of CKD. Furthermore, there was no difference in the serious adverse events between the surgical versus medical group (p = 0.8).

Ongoing RCT to investigate patients with CKD stages 3 to 5, such as the Randomized Study Comparing Metabolic Surgery with Intensive Medical Therapy to Treat Diabetic Kidney Disease (OBESE-DKD), may support the notion that bariatric surgery may stop the evolution of CKD in more advanced kidney disease. This clinical trial will randomize 60 patients with type 2 diabetes proteinuria, obesity, and CKD stage 3 to metabolic surgery or the best medical therapy. The endpoints to be assessed include directly measured GFR, albuminuria, weight loss, metabolic and cardiovascular parameters, and health care costs [72].

7. Randomized controlled trials of other obesity-related pharmacological agents in kidney disease

Several pharmacotherapies proven to aid weight loss, have either been removed or suspended from the market. Sibutramine was removed from the European market due to the increased risk of CV outcome [73]. The CV outcome trials for rimonabant were prematurely discontinued due to the increased risk of suicide [74] while the CV outcome of naltrexone-bupropion is still unknown due to the termination of its trial following a breach of confidentiality [75]. None were designed to evaluate the impact on kidney disease related to obesity.

The CAMELLIA-TIMI-61 (Cardiovascular and Metabolic Effects of Lorcaserin in Overweight and Obese Patients-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 61) trial evaluated the CV outcome of lorcaserin compared to placebo. Lorcaserin is proven to aid weight loss via appetite regulation through the activation of the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) pathway. This study included 12,000 participants who were overweight or obese (median BMI = 35 kg/m2) with CV diseases or CV risk factors, randomized to either lorcaserin 10 mg BD or placebo. There were triple odds of 5% weight loss in lorcaserin group and no differences in primary CV outcome were demonstrated when compared to placebo (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.85–1.14) [76]. A composite of new or worsening persistent micro- or macroalbuminuria, new or worsening CKD, doubling of serum creatinine, ESRD, renal transplant or renal death was the primary renal outcome of this trial. Close to 24% of participants had a baseline eGFR of < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 while 19% had urinary albumin: creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g indicating albuminuria. The primary renal outcome was reduced in the lorcaserin group (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.79– 0.96, p = 0.0064) compared to placebo. It is not known if this benefit is related to the weight loss of a direct action of the medication [8].

8. Conclusion

There is a dearth of RCT data in combination therapies of SGLT2i plus GLP-1a for DKD. Recently, Lam et al. performed an exploratory analysis of the AMPLITUDE-O trial in which cardiovascular and renal outcomes were analyzed with Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for region, SGLT2i randomization strata, and the SGLT2 inhibitor–by–treatment interaction [77]. The trial stratified randomization by baseline or anticipated use of SGLT2i and included the highest prevalence at baseline of SGLT2i use among GLP-1a cardiovascular outcome trials (n = 618, 15.2%). Results were analyzed to estimate the combined effect of SGLT2i and the GLP-1a on clinical outcomes. The effect (hazard ratio (95% CI)) of efpeglenatide versus placebo in the absence and presence of baseline SGLT2i on MACEs (0.74 (0.58–0.94) and 0.70 (0.37–1.30), respectively), expanded MACEs (0.77 (0.62–0.96) and 0.87 (0.51–1.48)), renal composite (0.70 (0.59–0.83) and 0.52 (0.33–0.83)), and MACEs or death (0.74 (0.59–0.93) and 0.65 (0.36–1.19)) did not differ by baseline SGLT2i use (p for all interactions >0.2). The reduction of blood pressure, body weight, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and uACR by efpeglenatide also appeared to be independent of concurrent SGLT2i use (all interactions p ≥ 0.08). Therefore, the study supports the usage of combined SGLT2i and GLP-1a in the management of T2D with evidence of additive or synergistic effects on renal events.

There is no data on combination therapies of bariatric surgery plus SGLT2i plus GLP-1a for DKD in the background of obesity. Therefore, trials examining the effect of these therapies on kidney protection in patients at high risk of DKD progression are warranted. Nevertheless, our findings have shown that the clinical management of DKD is evolving. Indeed, there is a need to address the treatment of patients with obesity and CKD to lessen morbidity. With the rapid growth and high prevalence of obesity in the CKD population, this area of research is critical and should take precedence.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Author contributions

RAW, ClR and RVC were responsible for the conception;RAW was responsible for the acquisition of the literature for the manuscript. RAW wrote the original draft of the manuscript. ClR and RVC reviewed and edited. ClR and RVC supervised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

ClR reports grants from the Irish Research Council, Science Foundation Ireland, Anabio, and the Health Research Board. He serves on advisory boards of Novo Nordisk, Herbalife, GI Dynamics, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Glia, and Boehringer Ingelheim. ClR is a member of the Irish Society for Nutrition and Metabolism outside the area of work commented on here. He was the chief medical officer and director of the Medical Device Division of Keyron in 2011. Both of these are unremunerated positions. ClR was a previous investor in Keyron, which develops endoscopically implantable medical devices intended to mimic the surgical procedures of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass. The product has only been tested in rodents and none of Keyron’s products is currently licensed. They do not have any contracts with other companies to put their products into clinical practice. No patients have been included in any of Keyron’s studies and they are not listed on the stock market. ClR was gifted stock holdings in September 2021 and divested all stock holdings in Keyron in September 2021. He continues to provide scientific advice to Keyron for no remuneration. RVC reports research grants from Johnson & Johnson Brazil and Medtronic, and serves as the speaker for Johnson & Johnson Brazil and Medtronic. He also serves on advisory boards of Johnson & Johnson Brazil, Medtronic, Keyron, GI Dynamics and Baritek. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1.Bray GA, Heisel WE, Afshin A, et al. The science of obesity management: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2018;39(2):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1083–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Zeltser LM, et al. Obesity pathogenesis: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2017;38(4):267–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdul Wahab R, Le Roux CW.. A review on the beneficial effects of bariatric surgery in the management of obesity. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2022;17(5):435–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovesdy CP, Furth SL, Zoccali C.. Obesity and kidney disease: hidden consequences of the epidemic. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2017;4:2054358117698669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen RV, Pereira TV, Aboud CM, et al. Effect of gastric bypass vs best medical treatment on early-stage chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;1155(8):e200420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann JFE, Orsted DD, Buse JB.. Liraglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;30377(22):2197–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scirica BM, Bohula EA, Dwyer JP, et al. Lorcaserin and renal outcomes in obese and overweight patients in the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial. Circulation. 2019;15139(3):366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tirosh A, Golan R, Harman-Boehm I, et al. Renal function following three distinct weight loss dietary strategies during 2 years of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2225–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckardt KU, Coresh J, Devuyst O, et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet. 2013;13382(9887):158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evangelista LS, Cho WK, Kim Y.. Obesity and chronic kidney disease: a population-based study among South Koreans. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0193559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuma A, Uchino B, Ochiai Y, et al. Relationship between abdominal adiposity and incident chronic kidney disease in young- to Middle-aged working men: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2019;23(1):76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madero M, Katz R, Murphy R, et al. Comparison between different measures of body fat with kidney function decline and incident CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(6):893–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H, Kuja-Halkola R, Chen X, et al. Higher body mass index is associated with incident diabetes and chronic kidney disease independent of genetic confounding. Kidney Int. 2019;95(5):1225–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alizadeh S, Esmaeili H, Alizadeh M, et al. Metabolic phenotypes of obese, overweight, and normal weight individuals and risk of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2019;2963(4):427–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrington WG, Smith M, Bankhead C, et al. Body-mass index and risk of advanced chronic kidney disease: prospective analyses from a primary care cohort of 1.4 million adults in England. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu X, Eales JM, Jiang X, et al. Contributions of obesity to kidney health and disease - insights from mendelian randomisation and the human kidney transcriptomics. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118 (15):3151–3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye C, Kong L, Zhao Z, et al. Causal associations of obesity with chronic kidney disease and arterial stiffness: a mendelian randomization study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(2):e825–e835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu P, Herrington WG, Haynes R, et al. Conventional and genetic evidence on the association between adiposity and CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(1):127–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Lerman LO.. Obesity and renovascular disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;309(4):F273–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nawaz S, Chinnadurai R, Al-Chalabi S, et al. Obesity and chronic kidney disease: a current review. Obesity Science & Practice. 2023;9:61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma K, Ramachandrarao S, Qiu G, et al. Adiponectin regulates albuminuria and podocyte function in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(5):1645–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briones AM, Nguyen Dinh Cat A, Callera GE, et al. Adipocytes produce aldosterone through calcineurin-dependent signaling pathways: implications in diabetes mellitus-associated obesity and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2012;59(5):1069–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camara NO, Iseki K, Kramer H, et al. Kidney disease and obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(3):181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, et al. Obesity, kidney dysfunction and hypertension: mechanistic links. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(6):367–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato S, Nazneen A, Nakashima Y, et al. Pathological influence of obesity on renal structural changes in chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13(4):332–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coward R, Fornoni A.. Insulin signaling: implications for podocyte biology in diabetic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24(1):104–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piwkowska A, Rogacka D, Kasztan M, et al. Insulin increases glomerular filtration barrier permeability through dimerization of protein kinase G type I alpha subunits. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832(6):791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrisey K, Evans RA, Wakefield L, et al. Translational regulation of renal proximal tubular epithelial cell transforming growth factor-beta1 generation by insulin. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(5):1905–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Carro C, Vergara A, Bermejo S, et al. A nephrologist perspective on obesity: from kidney injury to clinical management. Front Med 2021;8:655871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown E, Wilding JPH, Barber TM, et al. Weight loss variability with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity: mechanistic possibilities. Obes Rev. 2019;20(6):816–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajeev SP, Cuthbertson DJ, Wilding JP.. Energy balance and metabolic changes with sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibition. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(2):125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American diabetes association (ADA) and the European association for the study of diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2022;145(11):2753–2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perseghin G, Solini A.. The EMPA-REG outcome study: critical appraisal and potential clinical implications. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1413–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(16):1451–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herrington WG, Staplin N, Group E-KC, et al. Empagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):117–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neal B, Perkovic V, Matthews DR.. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(21):2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heerspink HJL, Stefansson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1436–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo-Jack S, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with ertugliflozin in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;8383(15):1425–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Pitt B, et al. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(2):129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies G, Consortium SiM-AC-RT Impact of diabetes on the effects of sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on kidney outcomes: collaborative meta-analysis of large placebo-controlled trials. Lancet. 2022;400(10365):1788–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheong AJY, Teo YN, Teo YH, et al. SGLT inhibitors on weight and body mass: a meta-analysis of 116 randomized-controlled trials. Obesity. 2022;30(1):117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pan R, Zhang Y, Wang R, et al. Effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on body composition in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0279889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nauck MA, Quast DR, Wefers J, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes - state-of-the-art. Mol Metab. 2021;46:101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jensterle M, Rizzo M, Haluzik M, et al. Efficacy of GLP-1 RA approved for weight management in patients with or without diabetes: a narrative review. Adv Ther. 2022;39(6):2452–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;3373(23):2247–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muskiet MHA, Tonneijck L, Huang Y, et al. Lixisenatide and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome: an exploratory analysis of the ELIXA randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(11):859–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.so SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;28375(4):311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mann JFE, Orsted DD, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):839–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.so SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;10375(19):1834–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, et al. Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13):1228–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Aart-van der Beek AB, Clegg LE, Penland RC, et al. Effect of once-weekly exenatide on estimated glomerular filtration rate slope depends on baseline renal risk: a post hoc analysis of the EXSCEL trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(12):2493–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an exploratory analysis of the REWIND randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gerstein HC, Sattar N, Rosenstock J, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with efpeglenatide in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(10):896–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sattar N, Lee MMY, Kristensen SL, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(10):653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Del Prato S, Kahn SE, Pavo I, et al. Tirzepatide versus insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes and increased cardiovascular risk (SURPASS-4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10313):1811–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heerspink HJL, Sattar N, Pavo I, et al. Effects of tirzepatide versus insulin glargine on kidney outcomes in type 2 diabetes in the SURPASS-4 trial: post-hoc analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(11):774–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.A/S NN . Semaglutide effects on heart disease and stroke in patients with overweight or obesity. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03574597. ;2018.

- 66.Lilly E. Company. A study of tirzepatide (LY3298176) compared with dulaglutide on major cardiovascular events in participants with type 2 diabetes. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04255433. 2020.

- 67.A Study of tirzepatide (LY3298176) on the reduction on morbidity and mortality in adults with obesity . https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05556512.

- 68.Lilly E. Company. A study of tirzepatide (LY3298176) in participants with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity (SUMMIT). https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04847557. ;2021.

- 69.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US renal data system 2018 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(3 Suppl 1):A7–A8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scheurlen KM, Probst P, Kopf S, et al. Metabolic surgery improves renal injury independent of weight loss: a meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(6):1006–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cohen RV, Pereira TV, Aboud CM, et al. Gastric bypass versus best medical treatment for diabetic kidney disease: 5 years follow up of a single-Centre open label randomised controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;53:101725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Friedman AN, Schauer PR, Beddhu S, et al. Obstacles and opportunities in managing coexisting obesity and CKD: report of a scientific workshop cosponsored by the national kidney foundation and the obesity society. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2022;30(12):2340–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.James WP, Caterson ID, Coutinho W, et al. Effect of sibutramine on cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2010;2363(10):905–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Topol EJ, Bousser MG, Fox KA, et al. Rimonabant for prevention of cardiovascular events (CRESCENDO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;14376(9740):517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nissen SE, Wolski KE, Prcela L, et al. Effect of naltrexone-bupropion on major adverse cardiovascular events in overweight and obese patients with cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;8315(10):990–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bohula EA, Wiviott SD, McGuire DK, et al. Cardiovascular safety of lorcaserin in overweight or obese patients. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1107–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lam CSP, Ramasundarahettige C, Branch KRH, et al. Efpeglenatide and clinical outcomes with and without concomitant sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition use in type 2 diabetes: exploratory analysis of the AMPLITUDE-O trial. Circulation. 2022;145(8):565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.