Abstract

Capsid engineering of adeno-associated virus (AAV) can surmount current limitations to gene therapy such as broad tissue tropism, low transduction efficiency, or pre-existing neutralizing antibodies (NAb) that restrict patient eligibility. We previously generated an AAV3B combinatorial capsid library by integrating rational design and directed evolution with the aim of improving hepatotropism. A potential isolate, AAV3B-DE5, gained a selective proliferative advantage over five rounds of iterative selection in hepatocyte spheroid cultures. In this study, we reanalyzed our original dataset derived from the AAV3B combinatorial library and isolated variants from earlier (one to three) rounds of selection, with the assumption that variants with faster replication kinetics are not necessarily the most efficient transducers. We identified a potential candidate, AAV3B-V04, which demonstrated significantly enhanced transduction in mouse-passaged primary human hepatocytes as well as in humanized liver chimeric mice, compared to the parental AAV3B or the previously described isolate, AAV3B-DE5. Interestingly, the AAV3B-V04 capsid variant exhibited significantly reduced seroreactivity to pooled or individual human serum samples. Forty-four percent of serum samples with pre-existing NAbs to AAV3B had 5- to 20-fold lower reciprocal NAb titers to AAV3B-V04. AAV3B-V04 has only nine amino acid substitutions, clustered in variable region IV compared to AAV3B, indicating the importance of the loops at the top of the three-fold protrusions in determining both transduction efficiency and immunogenicity. This study highlights the effectiveness of rational design combined with targeted selection for enhanced AAV transduction via molecular evolution approaches. Our findings support the concept of limiting selection rounds to isolate the best transducing AAV3B variant without outgrowth of faster replicating candidates. We conclude that AAV3B-V04 provides advantages such as improved human hepatocyte tropism and immune evasion and propose its utility as a superior candidate for liver gene therapy.

Keywords: AAV3B, gene therapy, hepatocyte, directed evolution, seroprevalence, neutralizing antibody, humanized liver chimeric mice, huFNRG mice

INTRODUCTION

The liver is an important target for in vivo gene therapy due to accessibility via peripheral vein injection, slow hepatocyte turnover, and an inherently tolerogenic microenvironment that favors long-term therapeutic gene expression.1–3 Although many viral and nonviral gene delivery methods into the liver have been described,4 arguably the most effective vehicle to date has been the adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector, with one FDA-approved product for hemophilia B (Hemgenix) and multiple treatments in late phase III clinical trials (NCT04370054, NCT05345171, NCT03370913, NCT03392974). One of the factors driving the mainstream application of AAV as the gene delivery vehicle of choice is its relative simplicity. The virion comprises a small ∼20–25 nm protein capsid that can package ∼4.7 kb of the therapeutic transgene, flanked by cis acting 145 base pair inverted terminal repeats (ITRs).5

Hepatic gene therapy with AAV vectors offers the potential for long-lived correction of monogenic disorders such as hemophilia A and B, ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, phenylketonuria, glycogen storage disease type Ia, Fabry disease, and Crigler Najjar syndrome,6–16 among others. A large predictor of therapeutic efficacy is hepatotropism of the vector capsid following intravenous infusion. Serotypes considered for liver targeting in clinical trials so far include AAV2,17 AAV8,10,11 and AAV9,4,18 although their capacity for effectively transducing human hepatocytes might not be optimal. The capsid is also the major determinant of recognition by the host immune system, resulting in the production of neutralizing antibodies (NAb). Up to 80% of the human population have pre-existing NAbs to the commonly used AAV serotypes, serving as a major patient exclusion criterion.19–22

Selecting a suitable vector serotype for hepatic gene therapy therefore involves a calculated balance between tissue tropism and evading immune responses. Approaches to circumvent pre-existing NAbs include testing other vector serotypes with lower pre-existing immunity such as AAV56,23 and AAV624 (NCT04046224, NCT03587116, NCT04370054), although these serotypes might not transduce hepatocytes as efficiently.25,26 This loss in efficiency is often offset by administering up to 6 × 1013 vg/kg titers in patients,6,27 which increases the risk of eliciting potent immune responses against both the vector and the transgene product.3,28–30 Thus, it is challenging to find an existing natural capsid that checks all the boxes for safe and efficacious hepatic gene delivery. More effective vector capsid variants are needed to propel clinical advancements in the gene therapy field.

Efforts to address this problem include the selection of novel capsid serotypes isolated from ancestral or other mammalian species.31–33 Alternatively, vector engineering by capsid shuffling, rational design by site-directed mutagenesis, directed evolution in the cell of interest, or a combination of these strategies have been used for improving transduction efficiency into the tissue of choice and/or selecting for NAb evasion.34–38 This can result in an entirely new recombinant capsid carrying components of the parental capsids34,39,40 or can result in the incorporation of modified amino acid sequences into the parent serotype. Recently, AAV3B was identified as an emerging clinical trial candidate for liver gene therapy because of its improved tropism to hepatocytes.26,41,42 Its properties can be further enhanced by incorporating targeted mutations.43–45 However, studies suggest a high prevalence of pre-existing antibodies to AAV3 among individuals,46,47 which may exclude a large percentage of the eligible patient population.

To address this, we generated an AAV3B combinatorial targeted variant library and used directed evolution to isolate enhanced liver targeting variants.35 Variants with targeted mutations in the capsid variable region (VR) loops36,48 gained a selective advantage after five rounds of selection in human hepatocarcinoma spheroid cultures.35 In vivo, the variant AAV3B-DE5 exhibited enhanced human hepatocyte tropism in a human liver chimeric mouse model. Importantly, AAV3B-DE5 showed reduced seroreactivity to human intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) as well as to individual serum samples from 100 healthy North American donors.35

The current study originated as a reanalysis of the data set generated in our previous study. It was inspired by the intriguing claims made by de Alencastro et al. in a recent publication49 that AAV replication in the presence of adenovirus helper factors can select for variants that replicate more efficiently but are not necessarily better transducers. Further, the authors claimed that using a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) and multiple rounds of selection can be detrimental to selection of the most desired variants. Considering that we had used adenovirus help, low starting MOIs and multiple (five) rounds of selection in our study, this raised valid concerns about whether superior transducing variants from early selection rounds were possibly lost due to the faster replication kinetics of AAV3B-DE5.

We therefore set out to screen earlier iterations from our original dataset. In addition, we also simplified our dataset by ignoring mutations in VR-I and treating everything outside VR-IV to VR-VII as wild type (wt), after observing that several sequences in the original dataset differed only in VR-I without a concomitant difference in enrichment.

This narrowed search identified two new variants that were further tested for improved in vivo transduction of human hepatocytes. One of these variants, AAV3B-V04, was shown to have significantly improved tropism for human hepatocytes compared to our previously identified AAV3B-DE5 capsid. Interestingly, AAV3B-V04 was less seroreactive compared to AAV3B or AAV3B-DE5, despite being remarkably similar to AAV3B, differing in only nine amino acids in VR-IV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

AAV3B capsid library

Detailed methods for generating the combinatorial AAV3B capsid library used in this study is described by Biswas et al.35 In brief, a replication competent AAV3B capsid library was generated by performing amino acid substitutions only on the capsid VRs VR-I, VR-IV, VR-V, VR-VI, and VR-VII, while keeping the backbone sequence unchanged. The library was constructed stepwise, by first constructing A (VR-I+VR-V+VR-VI), B (VR-IV), and C (VR-VII) sublibraries from overlapping synthetic oligonucleotides by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and isothermal DNA assembly, followed by packaging and purification. Finally, by using viral DNA as PCR templates, VRs from sublibraries A, B, and C were amplified and combined in one ABC plasmid library. The final viral library was packaged large scale and subjected to high-throughput Illumina sequencing, which supported a viral complexity on the order of 1 × 10.7

Data analysis

All data analyses except codon usage were done using caplib3: https://github.com/damienmarsic/caplib3

Codon analysis was performed using Rare Codon Search: https://www.bioline.com/media/calculator/01_11.html

Three-dimensional model was done using PyMOL: https://pymol.org/and the AAV3B structure (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3KIC).

Construction of AAV3B variants

Human liver-targeted AAV3B variants were selected by in vitro passaging the AAV3B library in human hepatocarcinoma (HUH-7) spheroid cells.35 Two variants: V04 and V05 were selected on the third passage, based on their relative enrichment. The region between amino acids 351–570, encompassing mutations in VR-IV to VR-VII, was synthesized for the two selected variants (Genscript USA, Inc., Piscataway, NJ). The sequences incorporating mutations in the epitopes were then individually cloned into the AAV3B capsid backbone using BsiWI and XcmI restriction enzymes corresponding to amino acid positions 351 and 570, respectively.

AAV3B-DE5, as described earlier,35 was selected from the same AAV3B library on the fifth passage based on its predominance in rounds 4 and 5 of selection.

AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, AAV3B-V04, AAV3B-V05, and AAV5 nonreplicating vectors were packaged to express the self-complementary Renilla luciferase (RLuc) transgene under control of the CAG promoter (C: cytomegalovirus early enhancer element, A: the first exon and the first intron of chicken β-actin gene promoter, G: splice acceptor of rabbit β-globin gene), flanked by AAV2 ITRs to generate rAAV3B (DE5, V04, V05)-CAG-RLuc. Alternatively, rAAVs were packaged to express the self-complementary mScarlet fluorescent reporter protein. rAAVs were produced by polyethylenimine-mediated transfection of adherent HEK-293 cells via a three-plasmid cotransfection system. Virus was purified by discontinuous iodixanol gradient centrifugation followed by dialysis using buffer exchange and concentration columns (Sartorius Vivaspin, Bohemia, NY).50 Virus titers were determined by real-time quantitative PCR using AAV2-ITR primers and probe as described.51

In vitro transduction

HUH-7 cell monolayers in 96-well plates were transduced over a MOI range (3.5 × 102–5 × 104 vg/cell) with AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, AAV3B-V04, or AAV3B-V05 encoding the RLuc transgene. Quantification of luciferase expression was carried out at 48 h using the Renilla-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) and measured on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader with luminescence detection capacity (Synergy HTX; BioTek, Inc., Shoreline, WA).

Mouse-passaged primary human hepatocytes (mpPHH) from humanized Fah−/−NOD Rag1−/−Il2rgnull (huFNRG) mice were isolated, plated in 10% fetal bovine serum-supplemented William's-E media in 24-well format on collagen-coated plates (BD Biocoat). The following day, cells were washed with William's-E media three times and cultured in hepatocyte complete medium (HCM; Lonza, Walkersville, MD) for 3 days. Cells were transduced in prewarmed HCM with limiting dilutions of AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, and AAV3B-V04 expressing the mScarlet transgene starting at 1 × 104 viral genome per plated cell. Cells were cultured for an additional 4 days, stained with Hoechst nuclear stain, and frequencies of mScarlet+ cells were quantified on Cytation 7 (BioTek) using autofluorescence of untransduced wells as baseline.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were housed at the Indiana University laboratory animal resources center (LARC). Food and water were given ad libitum. Animals were treated under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols.

Fah−/−NOD Rag1−/−Il2rgnull (FNRG) mice were used at the Rockefeller University under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol 21056. Cryopreserved pediatric human hepatocytes were purchased from Lonza. Fresh human hepatoblasts were isolated from human fetal livers (Advanced Bioscience Resources, Alameda, CA). All huFNRG mice in this article were generated with mpPHH from one donor (HUM4188).

In vivo transduction

C57BL/6 mice were injected via tail vein at 1 × 1011 vg/mouse (n = 4/group) with AAV3B, AAV3B-V04, or AAV8 vectors encoding either the mScarlet or GFP fluorescent reporter transgene. Transduced hepatocytes were quantified at 2 weeks by flow cytometry.

Human liver cell suspensions of 0.5–1 × 106 were injected into the spleens of FNRG mice under anesthesia.35 Starting on the day of transplantation, mice were cycled off the liver protective drug 2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylbenzoyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione (NTBC or nitisinone; Yecuris, Tualatin, OR)52 to stimulate repopulation with human hepatocytes. Human albumin levels in mouse sera were measured by ELISA (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX). All AAV vectors packaged a self-complementary genome encoding the mScarlet fluorescent reporter transgene flanked by AAV2 ITRs. One day before AAV injection, mice were placed back on NTBC using the “efficient” protocol termed previously.53 AAV3B-ST, AAV3B-DE5, AAV3B-V04, or vehicle control were injected through the tail vein at 1 × 1011 vg/mouse (n = 4–9/group). Two weeks later, human-chimeric mouse livers were isolated and processed. In vivo transduction efficiency was determined for each group by quantifying frequencies of mScarlet+ HLA class I+ human hepatocytes by flow cytometry on day 14.

Real-time PCR

C57BL/6 mice were euthanized 2 weeks after AAV3B, AAV3B-V04, or AAV8 tail vein injection. Genomic DNA was isolated from liver, kidney, heart, spleen, muscle, and brain using the genomic DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One hundred nanograms of input genomic DNA was used to quantitate AAV vector genome copies using transgene-specific primers. A PCR reaction was performed using the 2 × SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), using the following cycling conditions: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 35 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 30 s, using a CFX96 Touch real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad).

In vitro neutralization assay

1 × 103 vg/cell MOI of AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, or AAV3B-V04 expressing the RLuc transgene were incubated with serial twofold dilutions of pooled human IVIg (Privigen; CSL Behring, Bradley, IL). Further, 1 × 103 vg/cell MOI of AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, or AAV3B-V04 were preincubated with 30 individual healthy donor serum samples (Innovative Research, Inc., Novi, MI) for 2 h at 37°C. HUH-7 cell monolayers in 96-well plates were transduced as described with the vector: serum mix. RLuc expression was quantified after 24 h using the Renilla-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega) and measured on an ELISA reader with luminescence detection capacity (Synergy HTX; BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Neutralization titer for each sample is defined as the serum dilution at which RLuc expression is reduced by 50% compared to naive sera.

In a separate experiment, 1 × 104 vg/cell MOI of RLuc transgene expressing AAV3B, AAV3B-V04, or AAV5 were incubated with twofold dilutions of pooled human IVIg and overlayed on 2V6.11 cell monolayers (expressing the adenovirus E4 ORF gene product) as described.54 RLuc expression was quantified after 24 h.

Statistical analysis

Data are normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test) unless indicated otherwise. For neutralization assays, reciprocal NAb titers were extrapolated by nonlinear curve fitting methods and analyzed using four- to five parameter half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) tests or fourth-order polynomial curve fitting in GraphPad Prism 8. Comparison between multiple groups was performed using one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey's or Dunnett's post hoc analysis.

RESULTS

Directed evolution

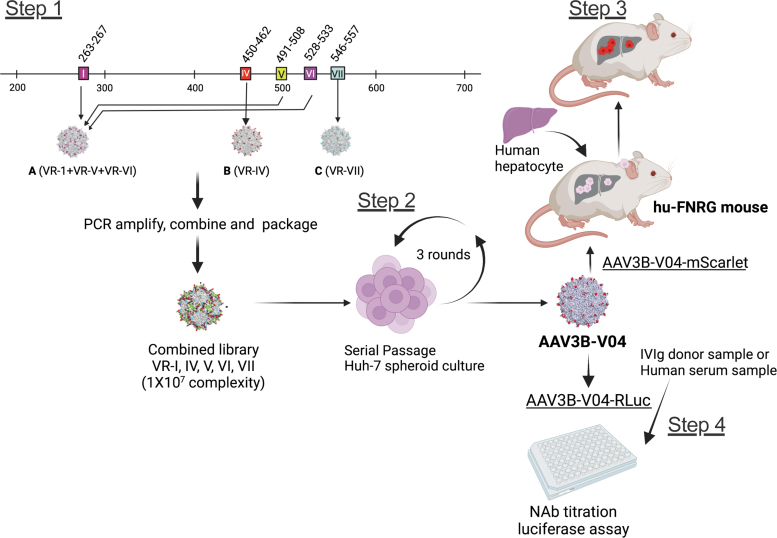

The AAV3B combinatorial library used to identify the new capsid variants was described earlier.35 In brief, surface-exposed residues in VR-I to VR-VII were diversified by PCR using degenerate oligonucleotides. Library construction was incremental to maximize the likelihood of combining mutations compatible with capsid assembly. Three sublibraries were first constructed, each with mutations in one or more different regions. Their viral DNA was then used to generate the final library that included mutations in all five VRs, therefore filtering out sequences that failed to result in functional viral particles (Fig. 1, Step 1). Viral complexity was estimated to be in the order of 1 × 10.7

Figure 1.

Steps involved in isolating and evaluating AAV3B-V04 from a combinatorial AAV3B library. Step 1: sublibraries A, B, and C with mutations in VR-I, VR-IV, and VR-VII, respectively, are first assembled, combined, and then packaged. Step 2: Library is subjected to three rounds of replication in human hepatocarcinoma spheroid cultures. AAV3B-V04 is isolated and evaluated in vitro and in vivo. Step 3: Transduction efficiency is tested in mpPHH in vitro and in huFNRG mouse livers in vivo. Step 4: Evasion of NAb titers in IVIg and individual human serum samples is evaluated in vitro. AAV, adeno-associated virus; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; mpPHH, mouse-passaged primary human hepatocytes; NAb, neutralizing antibodies; VR, variable region.

The directed evolution process aimed at selecting variants with hepatocyte tropism was also described previously.35 In brief, five iterative selections in 3D human hepatocellular carcinoma (HUH-7) spheroid cultures were performed, using an initial MOI of 1 and subsequent MOIs of 0.01. Superinfection with human adenovirus 5 (Ad5) was performed at each round of selection to facilitate AAV replication.34

To minimize the potential bias caused by low MOI, use of Ad5, and the large number of selection cycles,49 we focused on the results from the first three rounds of selection (Fig. 1, Step 2). In addition, we reasoned that diversification of VR-I had introduced unnecessary complexity into the analysis because we observed no significant enrichment for any mutations in this region. Therefore, we elected to treat the VR-I region as wt to simplify data analysis.

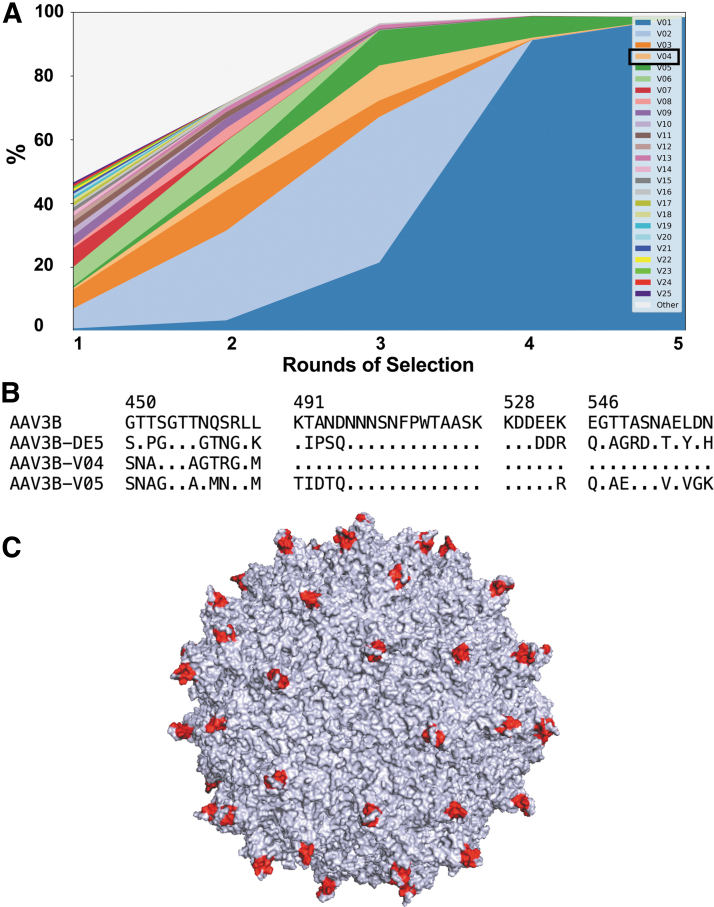

The resulting amino acid sequences were sorted by their maximal frequency across all rounds of selection. The evolution of the top 25 sequences is shown in Fig. 2A. Enrichment scores were computed based on enrichment factors between first and second rounds and between second and third rounds of selection (Table 1). AAV3B-DE5 (indicated as V01 in both Table 1 and Fig. 2A), in addition to being the most abundant variant at passages 4 and 5, was also the most enriched from rounds 1 to 3. To examine whether enrichment scores might have been affected by differences in replication kinetics in the hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, the incidence of rare codons in the original nucleotide sequences was analyzed (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Evolution of sequence frequencies. (A) Sequences were sorted by their highest frequency among the five samples (each sample corresponding to one round of selection in HUH-7 spheroid cultures). The top 25 sequences are displayed with a separate color (V1–V25). All other sequences are combined under a single color (Other). AAV3B-V04 is highlighted (light orange). AAV3B-DE5 is indicated as V01. (B) Alignment of parental capsid AAV3B and variants AAV3B-DE5, AAV3B-V04, and AAV3B-V05. Only diversified regions in VR-IV, VR-V, VR-VI, and VR-VII are shown. Numbers indicate amino acid position (VP1 numbering); sequence identity with AAV3B is represented by a dot. (C) Three-dimensional structural model of AAV3B showing the positions of the AAV3B-V04 mutations in red.

Table 1.

Sequences with a positive enrichment score after three selection rounds

| Sequence ID | Frequency, % | 1–2 enrichment | 2–3 enrichment | Enrichment score | Rare codons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V01 | 21.47 | 4.24 | 6.45 | 1.44 | 16 |

| V04 | 11.00 | 6.21 | 3.16 | 1.29 | 18 |

| V05 | 10.97 | 4.72 | 3.77 | 1.25 | 15 |

| V13 | 1.23 | 12.63 | 0.87 | 1.04 | 17 |

| V02 | 45.71 | 4.49 | 1.62 | 0.86 | 16 |

| V27 | 0.58 | 3.19 | 1.08 | 0.54 | 15 |

The frequency column represents the sequence abundance after the third round of selection. One to two enrichment: sequence enrichment factor between first and second round. Two to three enrichment: sequence enrichment factor between second and third round. Enrichment score: Log of product of enrichment factors. Rare codons: number of codons with frequency lower than 7% in the coding nucleotide sequence.

Apart from AAV3B-DE5, only five other sequences had a positive enrichment score, of which only two, V04 and V05, had both a score higher than 1 and actual enrichment at both intervals. V04 was of particular interest because it had the highest incidence of rare codons, suggesting that its enrichment score could possibly have been higher than what was observed.

Sequence comparison showed that V04 was highly similar to the parent AAV3B, with only nine amino acid substitutions concentrated in VR-IV. In contrast, V05 had mutations distributed over all four VR regions: VR-IV to VR-VII (Fig. 2B). The positions of the mutations in the V04 capsid are represented in Fig. 2C.

Improved in vitro hepatocyte transduction by early passage variants

Transduction efficiency of AAV3B, AAV3B-V04, AAV3B-V05, and the previously described passage 5 variant, AAV3B-DE535 was tested in vitro using (i) HUH-7 human hepatocellular carcinoma adherent monolayers and (ii) mpPHH.

-

(i)

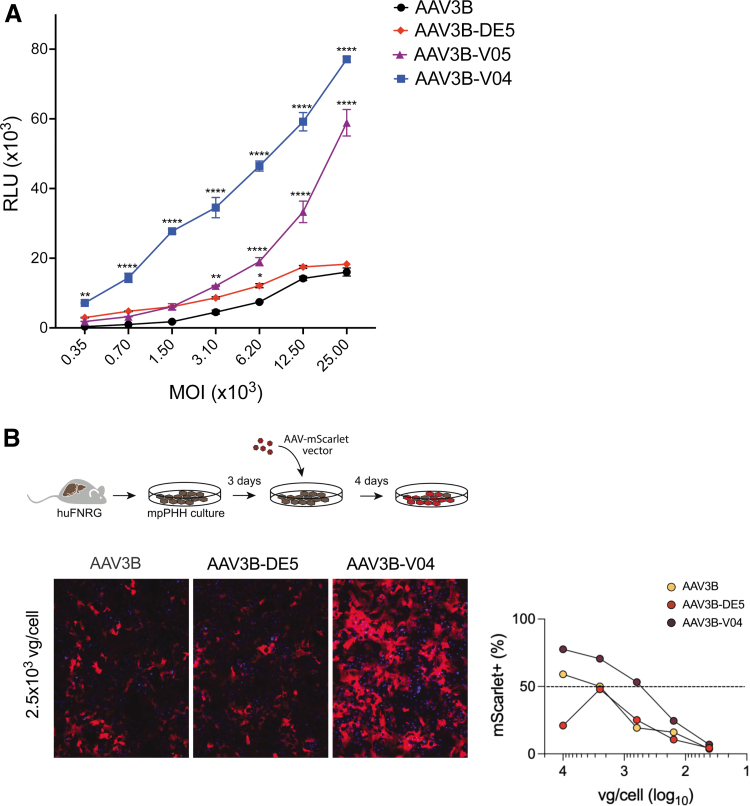

Vectors encoding the RLuc transgene driven by the ubiquitous CAG promoter were transduced at varying MOIs. All variants (AAV3B-VO4, AAV3B-V05, AAV3B-DE5) transduced HUH-7 cells more efficiently than the parent AAV3B vector. AAV3B-V04 had significantly increased RLuc expression compared to the other variants (Fig. 3A).

-

(ii)

We further tested AAV3B-V04 transduction in mpPHH, which were isolated from humanized Fah−/−NOD Rag1−/−Il2rgnull (huFNRG) mice and cultured in vitro as described.55 Following transduction with varying MOIs (50–104 vg/cell) of AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, or AAV3B-V04 encoding the mScarlet transgene, frequencies of mScarlet+ HLA class I+ mpPHH cells were quantified. Recapitulating the findings in HUH-7 cells, AAV3B-V04 transduced mpPHH monolayers at higher frequencies compared to AAV3B and AAV3B-DE5 at most of the MOIs tested (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Comparison of in vitro transduction efficiency. (A) Transduction efficiencies of AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, AAV3B-V04, and AAV3B-V05 at varying MOIs on HUH-7 adherent cells, using RLuc relative luminescence units at 48 h as a readout. (B) Schema and fluorescence images of mpPHH cells transduced with 2.5 × 103 MOI of AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, or AAV3B-V04 expressing the mScarlet reporter transgene product. AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, and AAV3B-V04 MOIs corresponding to 50% mScarlet transduction in mpPHH cells as quantified on Cytation 7 are indicated. Data are an average of at least two replicates per group per test condition and are the best representative of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis is performed by two-way ANOVA with a Sidak's multiple comparison test for A. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. A p-value <0.05 is considered statistically significant and indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001. MOI, multiplicity of infection; RLuc, Renilla luciferase; SEM, standard error of the mean.

We further compared AAV3B and AAV3B-V04 transduction of human cell lines derived from different tissues. Although AAV3B-V04 transduced HUH-7 cells more efficiently than AAV3B, we observed that both AAV3B and AAV3B-V04 exhibited similarly high transduction of osteosarcoma cells (U2-OS and SA-OS), and low transduction of pancreatic (CCD-13LU) or neuronal cells (Neuro-2C) cells, indicating that tropism of AAV3B-V04 did not appear to be altered (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Improved in vivo hepatocyte transduction by AAV3B-V04

huFNRG mice humanized with mpPHH were generated as described.53,55 High engraftment of PHH was confirmed by high levels (median 10.5 mg/mL, ranging from 7.6 to 29.2 mg/mL) of human albumin in mouse serum, which correlates with ∼90% humanization.56–58 We compared transduction efficiencies of PHH in animals receiving 1 × 1011 vg of AAV3B-ST, AAV3B-DE5, and AAV3B-V04 expressing the mScarlet transgene, administered intravenously (Fig. 1, Step 3). We selected these two vectors for comparison because they were previously shown to transduce huFNRG livers with high efficiency.35 AAV3B-ST, an engineered AAV3B variant with two amino acid modifications in surface-exposed capsid residues (S663V+T492V)43 was previously shown to transduce human liver xenografts and nonhuman primates more effectively as compared to AAV5, AAV8, AAV9, and AAV3B.42,43,59

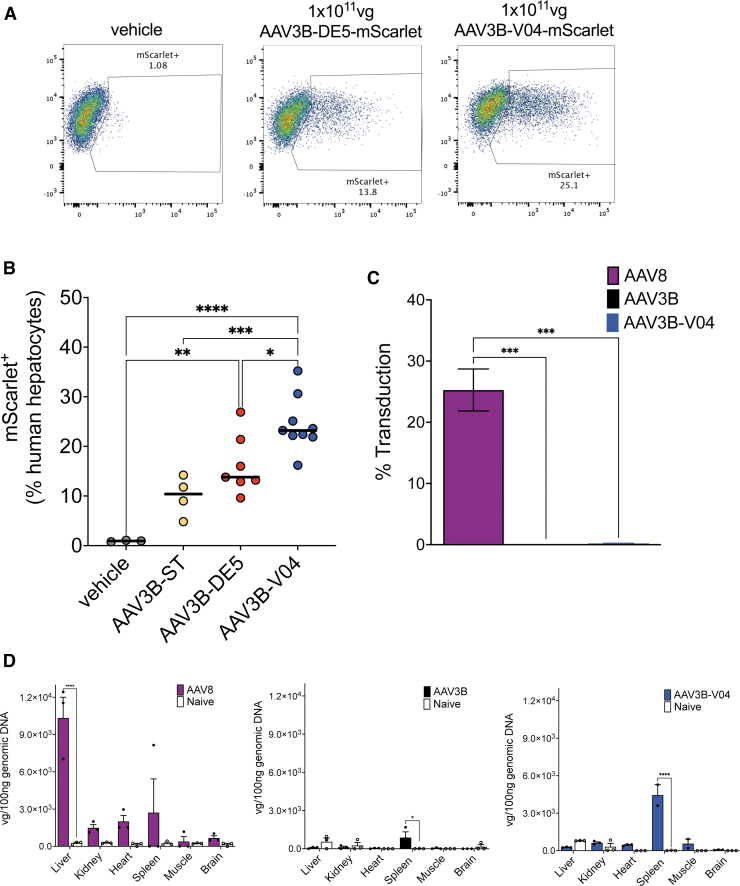

Flow cytometric quantification of transduced HLA-1+ mScarlet+ human hepatocytes (Fig. 4A) showed transduction frequencies of ∼5–14% for AAV3B-ST (median transduction 10.4%), ∼10–27% for AAV3B-DE5 (median transduction 13.8%), compared to 16–35% for AAV3B-V04 (median transduction 23.2%, p = 0.0006 and 0.01, respectively, Fig. 4B). We were unable to verify mouse hepatocyte detargeting using this model due to high human engraftment and loss of mouse hepatocytes during isolation due to NTBC withdrawal stress. Therefore, we intravenously injected 1 × 1011 vg of AAV3B, AAV3B-V04, or AAV8 expressing either the mScarlet or GFP transgene into immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice and quantified transduction on day 14 by flow cytometry and real-time RT-PCR. We confirmed that AAV3B and AAV3B-V04 poorly transduced mouse hepatocytes compared to AAV8, which has high tropism for murine hepatocytes (Fig. 4C).42,60

Figure 4.

In vivo transduction efficiency in mice. (A) Density plots showing frequencies of vehicle control, AAV3B-DE5, or AAV3B-V04 transduced human hepatocytes isolated from huFNRG mouse livers (n = 4–9/group). Transduced human hepatocytes are characterized as HLA-I+ mScarlet+ by flow cytometry. (B) Comparison of transduction frequencies of HLA-I+ mScarlet+ human hepatocytes. (C) Quantification of transduced hepatocytes from C57BL/6 mice (n = 3/group) intravenously injected with AAV8, AAV3B, or AAV3B-V04. (D) Quantification of vector genome copies/100 ng genomic DNA isolated from livers, kidneys, hearts, spleens, muscles, and brains of C57BL/6 mice (n = 3/group) intravenously injected with AAV8, AAV3B, or AAV3B-V04. Data are an average of at least two independent experiments. Statistical analysis is performed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test for (B). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. A p-value <0.05 is considered statistically significant and indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Furthermore, we only detected low vector genome copies in kidneys, heart, muscles, brains, and moderate copies in spleens of AAV3B- and AAV3B-V04-injected mice (Fig. 4D). These findings indicate that mutations in the AAV3B-V04 variant did not alter tissue tropism in mice.

Improved evasion of NAbs by AAV3B-VO4

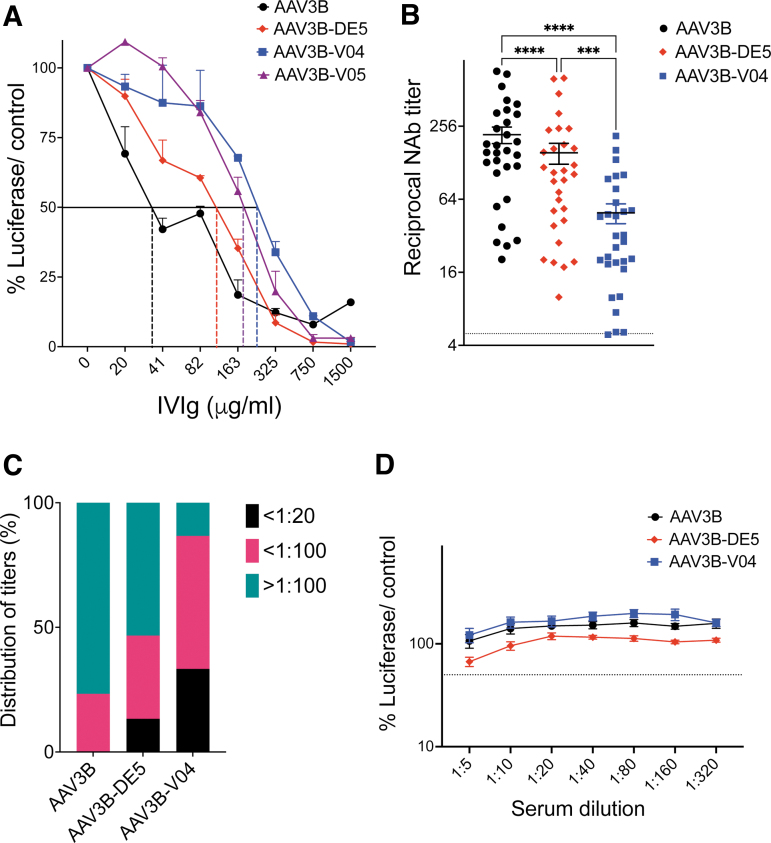

We assessed vector capsid neutralization by pre-existing NAbs from human sera using either IVIg or human sera from individual donors. In vitro transduction of HUH-7 cells by AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, AAV3B-V04, or AAV3B-V05 (1 × 103 vg/cell) was quantified in the presence of serial dilutions of IVIg or test serum samples, using RLuc expression as readout.20,54,61 The average IVIg concentration required to neutralize transduction by 50% (IC50) for AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, AAV3B-V04, and AAV3B-V05 was 38, 115.6, 256, and 160.8 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 5A), with an observed 6.7-fold increase in IC50 for AAV3B-V04 over the parent AAV3B capsid.

Figure 5.

In vitro neutralization assays. (A) IVIg: Inhibition of HUH-7 adherent cell transduction by AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, AAV3B-V04, or AAV3B-V05 using increasing concentrations of pooled IVIg (20–1,500 μg/mL). The IVIg concentration corresponding to 50% reduction in RLuc expression (RLU) for each group, compared to a no IVIg control, is indicated with dashed lines. (B) Determination of mean reciprocal NAb titers to AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, and AAV3B-V04 for 30 seropositive samples from individual healthy donors using an in vitro RLuc-based assay. Samples that can inhibit transduction by 50% at ≥1:5 dilution are considered seropositive. (C) Distribution of NAb titers from (B). Frequencies of serum samples with NAb titers <1:20, <1:100, and >1:100 to AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, and AAV3B-V04 are indicated. (D) Eight individual serum samples without detectable (<1:5) NAb to AAV3B are evaluated for NAb to AAV3B-DE5 and AAV3B-V04. Data are represented as mean ± SEM are an average of at least two replicates per group per test condition and are the best representative of at least two independent experiments. IC50 is determined for (A, B, D) using a four-parameter curve fit test. Statistical analysis is performed by two-way ANOVA with a Dunnett's comparison test for (A) and a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey's multiple comparison test for (B, D). A p-value <0.05 is considered statistically significant and indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration.

We also compared IVIg neutralization of AAV3B, AAV3B-V04, or AAV5 using the 2V6.11 in vitro cell reporter system.54 AAV5 is currently evaluated in clinical trials for liver gene transfer6,62 due to its lower global seroprevalence.23,63 AAV5 (IC50 = 240.7 μg/mL) was less sensitive to neutralization compared to either AAV3B (47.21 μg/mL) or AAV3B-V04 (91.47 μg/mL), although the IC50 concentration for AAV3B-V04 was higher than for AAV3B (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Next, we assessed a pool of 100 individual serum samples from healthy donors, which we had previously screened.35 Of these, 30 samples had detectable (>1:5 NAb dilution) capsid NAb titers to both AAV3B and AAV3B-DE5. We compared the seroreactivity of these 30 serum samples toward AAV3B, AAV3B-DE5, and AAV3B-V04. In all samples, we observed a substantial reduction in reciprocal NAb titers required to neutralize AAV3B-V04, compared to AAV3B or AAV3B-DE5 (p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc analysis, Fig. 5B). Average reciprocal serum NAb titers were ∼4- and 3-fold lower for AAV3B-V04 compared to AAV3B or AAV3B-DE5 (mean difference of 168.6 and 105.3, respectively), indicating significant NAb evasion by the AAV3B-V04 variant (Fig. 5B).

For each variant, frequencies of seropositive individuals with titers <1:20, <1:100, or ≥1:100 were determined (Fig. 5C). Distribution of donors with titers ≥1:100 was highest for AAV3B (77%). For AAV3B-V04, 33% of donors presented with low titers (<1:20), whereas the majority had intermediate titers (1:20–1:100, 53%). Only 13% of donors presented with titers ≥1:100. Importantly, none of the serum samples had higher titers for AAV3B-V04 compared to AAV3B, indicating that new antigenic determinants were not selected for or created by the 450-SNASGTAGTRGLM-462 mutations on VR-IV of AAV3B-V04. To confirm this, we tested eight serum samples that had undetectable NAb titers to AAV3B and AAV3B-DE5. We did not observe any detectable NAb titers for AAV3B-V04 in these samples (Fig. 5D), indicating that our selection conditions did not create new immunogenic epitopes.

DISCUSSION

The nature of exposed amino acid residues on the AAV capsid surface largely determines receptor attachment, tissue transduction, and antigenicity.64 Capsid surface topology is mostly conserved in all AAVs, with major features, including fivefold channels, threefold protrusions, twofold depressions, and an interior nucleotide binding site.65,66 Serotype differences are attributed to unique features at the VRs in the surface loops that connect the strands in a β-barrel motif at the core of each viral protein making up the capsid.65 These differences in the VRs presumably contribute to serotype-specific receptor interactions, immune recognition, cell tropism, and transduction efficiency.67

Capsid engineering by introducing deliberate mutations for the purpose of improving tissue targeting and evading immune recognition is an attractive alternative to the use of natural serotypes, which may be limited in their capacity to optimally deliver the gene of interest.45 Capsid engineering also has the potential to address the issue of immunotoxicities. Most of the serious adverse events and loss in transgene expression associated with AAV gene therapy appear to be triggered by immune responses to the high vector doses that are administered to achieve therapeutic levels of transgene expression.6,8,30,68–71

Capsid engineering can alleviate this by improving or modifying tissue tropism, thereby reducing the overall vector burden. Lower capsid titers can also reduce the formation of capsid antigen-antibody complexes, thus evading complement activation and deleterious innate immune responses.72 Engineered capsids have not yet been widely adopted in clinical settings, although this is expected to increase, with several being explored in preclinical studies.

The most common capsid engineering strategy is capsid shuffling followed by directed evolution in the cell or tissue of interest.40,48,73,74 This has resulted in the isolation of promising candidates such as LK03, currently used in clinical trials for liver gene transfer (NCT05092685, NCT05092685, etc.).8,34 Interestingly, although LK03 is a shuffled capsid, it shares the most identity with AAV3B. Therefore, our approach was to introduce rational mutagenesis into surface-exposed residues in the VR loops of AAV3B, which led to the recent isolation of the AAV3B-DE5 variant,35 and to our current candidate, AAV3B-V04.

Recent work by the Srivastava laboratory and others revealed the ability of AAV3B to transduce human and nonhuman primate hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo,19,43,59 likely owing to the use of human hepatocyte growth factor receptor for cellular entry.75 Performance of the AAV3 capsid was further improved by eliminating one serine and one threonine residue (AAV3-ST containing mutations S663V and T492V). Here, we show that AAV3B-V04 transduces human hepatocytes significantly better than either AAV3-ST or AAV3B-DE5 in humanized liver chimeric mice, which are emerging as an essential model to validate human hepatocyte transduction efficacy at the preclinical stage.53

Since VR-IV, VR-V, and VR-VIII form the top of the threefold protrusion on the AAV capsid, mutations at these loops affect cell tropism and receptor attachment, transduction efficiency, and antigenic reactivity.76,77 Other directed evolution studies have implied that VR-IV and VR-VIII are more likely to dictate host cell interactions that determine evolutionary pressure. We found that AAV3B-V04 differs from the parent AAV3B in only nine amino acids, located in the VR-IV loop region. Residues 450-GTTSGTTNQSRLL-462 on VR-IV of AAV3B are mutated to 450-SNASGTAGTRGLM-462. Interestingly, improved transduction in AAV3B-V04 is also associated with improved evasion of NAb responses, suggesting possible coevolution of tropism and capsid antibody evasion.

It has previously been proposed that residues implicated in antigenic recognition also influence other biological properties of the AAV capsid, such as attachment to cell receptors.78 Therefore, it appears that for AAV3B-V04, the VR-IV loop is a major determinant of both capsid tropism and antigenicity. A recent study showed that introducing S472A, S587A, and N706A substitutions into VR-IV, VR-VIII, and VR-IX, respectively of the AAV3B capsid reduces reactivity to anticapsid NAbs.45 While mutations in our AAV3B-V04 isolate were concentrated in the VR-IV region, it will be interesting to explore whether incorporating additional directed mutations such as S587A (VR-VIII) to AAV3B-V04 will further improve NAb evasion properties.

The seroprevalence to AAV3B is significant.35,79,80 AAV5, which has lower seroprevalence,23 was more resistant to neutralization compared to either AAV3B or AAV3B-V04. It is currently unclear whether low NAb titers can preclude transduction with AAV5, as transduction has been observed in some hemophilia B patients in the presence of pre-existing NAbs.81,82 However, AAV3B-V04 significantly evaded neutralization by pooled or individual human serum samples. The reduced seroreactivity for AAV3B-V04 therefore has the potential to expand patient inclusion. In support of this, 44% of the individual serum samples with pre-existing NAbs to AAV3B had 5- to 20-fold lower reciprocal NAb titers to AAV3B-V04.

de Alencastro et al. recently reported parameters that should be taken into consideration for maximizing AAV variant selection with desired properties.49 These include forgoing help from adenovirus type 5 superinfection, using high starting MOIs during directed evolution, and isolating variants from earlier rounds of selection. The authors reasoned that the most enriched AAV capsid variants selected after several rounds of replication were not necessarily the most efficient for transduction, whereas variants that transduced the target cell line with high efficiency could be lost or greatly diminished over rounds of selection. Although our selection used low MOI and Ad5 coinfection, by restricting our analysis to earlier rounds of selection in the current study, we were able to identify the V04 and V05 variants, with considerably enhanced transduction capacity for human hepatocytes.

These variants were enriched up to the third round of selection, but were lost in successive rounds due to the dominance of AAV3B-DE5, which overwhelmingly took over at passage 4 and 5, possibly due to its increased replicative potential. However, we did not directly observe differences in replicative ability between the variants. In fact, production yields of AAV3B-DE5, V04, and V05 were indistinguishable from that of wt AAV3B (from three small scale AAV preparations, data not shown), although in the case of V04 and V05, the mutated positions were codon optimized.

Our study has a few limitations. One fundamental shortcoming is selection based on cellular entry as opposed to functional transduction, requiring the evaluation of multiple candidates to identify the most desirable variants. In contrast, mRNA-based selection approaches, although more technically challenging, have the potential to identify the best candidates using fewer selection steps.83,84

We did not compare human hepatocyte transduction efficacy with other serotypes currently used in liver gene therapy clinical trials such as AAV5, AAV6, or the engineered variant, LK03, which is highly similar to AAV3B. Second, while we were able to confirm high human hepatocyte tropism for AAV3B-V04, we did not determine detargeting from other human tissues. Although AAV3B has been shown to have low tropism for tissues such as skeletal muscle or heart in nonhuman primates,43 we cannot completely discount the possibility that the amino acid changes in VR-IV of AAV3B-V04 might introduce new receptor binding sites.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we suggest that identification of novel capsids by directed evolution from a diverse mutant capsid library can be improved by careful data analysis and by limiting the number of rounds of selection. We conclude that the candidate variant AAV3B-V04 described here is superior to its parent AAV3B capsid, as well as to the previously described AAV3B-DE5 isolate. AAV3B-V04 provides distinct advantages such as improved transduction efficiency, tissue tropism, and reduced immunogenicity. Since the liver is an important target for gene delivery in many gene therapy applications, AAV3B-V04 as a vector offers high potential to explore translational liver gene transfer studies.

Supplementary Material

ETHICS APPROVAL

Animal studies were performed by Rockefeller University under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol 21056. Animals at Indiana University School of Medicine were treated under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Recombinant AAV3B sequences are available in GenBank.

AUTHORs' CONTRIBUTIONS

D.M., S.Z., and M.B. conceptualized the study. J.R., D.M., C.Z., M.-M.M., X.L., O.K., and N.L. performed experiments; J.R., D.M., Y.P.d.J., S.Z., and M.B. designed experiments; J.R., D.M., Y.P.d.J., S.Z., and M.B. analyzed and interpreted data; D.M., Y.P.d.J., S.Z., and M.B. wrote the article; Y.P.d.J., S.Z., and M.B. supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final article.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE

No competing financial interests exist.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants 1P01HL160472-01 (Ype P. de Jong and Moanaro Biswas) and R01 HL097088 (Sergei Zolotukhin).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

REFERENCES

- 1. Nathwani AC, Gray JT, Ng CY, et al. Self-complementary adeno-associated virus vectors containing a novel liver-specific human factor IX expression cassette enable highly efficient transduction of murine and nonhuman primate liver. Blood 2006;107(7):2653–61; doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mingozzi F, Liu YL, Dobrzynski E, et al. Induction of immune tolerance to coagulation factor IX antigen by in vivo hepatic gene transfer. J Clin Invest 2003;111(9):1347–56; doi: 10.1172/JCI16887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colella P, Ronzitti G, Mingozzi F. Emerging issues in AAV-mediated in vivo gene therapy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2018;8:87–104; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maestro S, Weber ND, Zabaleta N, et al. Novel vectors and approaches for gene therapy in liver diseases. JHEP Rep 2021;3(4):100300; doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grieger JC, Samulski RJ. Packaging capacity of adeno-associated virus serotypes: Impact of larger genomes on infectivity and postentry steps. J Virol 2005;79(15):9933–9944; doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9933-9944.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pasi KJ, Rangarajan S, Mitchell N, et al. Multiyear follow-up of AAV5-hFVIII-SQ gene therapy for hemophilia A. N Engl J Med 2020;382(1):29–40; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang L, Bell P, Morizono H, et al. AAV gene therapy corrects OTC deficiency and prevents liver fibrosis in aged OTC-knock out heterozygous mice. Mol Genet Metab 2017;120(4):299–305; doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. George LA, Monahan PE, Eyster ME, et al. Multiyear factor VIII expression after AAV gene transfer for hemophilia A. N Engl J Med 2021;385(21):1961–1973; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baruteau J, Cunningham SC, Yilmaz BS, et al. Safety and efficacy of an engineered hepatotropic AAV gene therapy for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency in cynomolgus monkeys. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2021;23:135–146; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. George LA, Sullivan SK, Giermasz A, et al. Hemophilia B gene therapy with a high-specific-activity factor IX variant. N Engl J Med 2017;377(23):2215–2227; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nathwani AC, Reiss UM, Tuddenham EG, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of factor IX gene therapy in hemophilia B. N Engl J Med 2014;371(21):1994–2004; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kishnani PS, Sun B, Koeberl DD. Gene therapy for glycogen storage diseases. Hum Mol Genet 2019;28(R1):R31–R41; doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collaud F, Bortolussi G, Guianvarc'h L, et al. Preclinical development of an AAV8-hUGT1A1 vector for the treatment of Crigler-Najjar syndrome. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2019;12:157–174; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Greig JA, Nordin JML, Draper C, et al. AAV8 gene therapy rescues the newborn phenotype of a mouse model of Crigler-Najjar. Hum Gene Ther 2018;29(7):763–770; doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tao R, Xiao L, Zhou L, et al. Long-term metabolic correction of phenylketonuria by AAV-delivered phenylalanine amino lyase. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2020;19:507–517; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mochizuki S, Mizukami H, Ogura T, et al. Long-term correction of hyperphenylalaninemia by AAV-mediated gene transfer leads to behavioral recovery in phenylketonuria mice. Gene Ther 2004;11(13):1081–1086; doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. George LA, Ragni MV, Rasko JEJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of the first in human intravascular delivery of AAV for gene transfer: AAV2-hFIX16 for severe hemophilia B. Mol Ther 2020;28(9):2073–2082; doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Du S, Ou H, Cui R, et al. Delivery of glucosylceramidase beta gene using AAV9 vector therapy as a treatment strategy in mouse models of Gaucher disease. Hum Gene Ther 2019;30(2):155–167; doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang D, Tai PWL, Gao G. Adeno-associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019;18(5):358–378; doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0012-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weber T. Anti-AAV antibodies in AAV gene therapy: Current challenges and possible solutions. Front Immunol 2021;12:658399; doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.658399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Calcedo R, Vandenberghe LH, Gao G, et al. Worldwide epidemiology of neutralizing antibodies to adeno-associated viruses. J Infect Dis 2009;199(3):381–390; doi: 10.1086/595830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kruzik A, Fetahagic D, Hartlieb B, et al. Prevalence of anti-adeno-associated virus immune responses in international cohorts of healthy donors. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2019;14:126–133; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klamroth R, Hayes G, Andreeva T, et al. Global seroprevalence of pre-existing immunity against AAV5 and other AAV serotypes in people with hemophilia A. Hum Gene Ther 2022;33(7–8):432–441; doi: 10.1089/hum.2021.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boutin S, Monteilhet V, Veron P, et al. Prevalence of serum IgG and neutralizing factors against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 in the healthy population: Implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum Gene Ther 2010;21(6):704–712; doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qian R, Xiao B, Li J, et al. Directed evolution of AAV serotype 5 for increased hepatocyte transduction and retained low humoral seroreactivity. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2021;20:122–132; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brown HC, Doering CB, Herzog RW, et al. Development of a clinical candidate AAV3 vector for gene therapy of hemophilia B. Hum Gene Ther 2020;31(19–20):1114–1123; doi: 10.1089/hum.2020.099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Batty P, Lillicrap D. Gene therapy for hemophilia: Current status and laboratory consequences. Int J Lab Hematol 2021;43(Suppl 1):117–123; doi: 10.1111/ijlh.13605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Long BR, Veron P, Kuranda K, et al. Early phase clinical immunogenicity of valoctocogene roxaparvovec, an AAV5-mediated gene therapy for hemophilia A. Mol Ther 2021;29(2):597–610; doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perrin GQ, Herzog RW, Markusic DM. Update on clinical gene therapy for hemophilia. Blood 2019;133(5):407–414; doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-820720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Monahan PE, Negrier C, Tarantino M, et al. Emerging immunogenicity and genotoxicity considerations of adeno-associated virus vector gene therapy for hemophilia. J Clin Med 2021;10(11):2471; doi: 10.3390/jcm10112471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Santiago-Ortiz J, Ojala DS, Westesson O, et al. AAV ancestral reconstruction library enables selection of broadly infectious viral variants. Gene Ther 2015;22(12):934–946; doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gross DA, Tedesco N, Leborgne C, et al. Overcoming the challenges imposed by humoral immunity to AAV vectors to achieve safe and efficient gene transfer in seropositive patients. Front Immunol 2022;13:857276; doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.857276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Asokan A, Schaffer DV, Samulski RJ. The AAV vector toolkit: Poised at the clinical crossroads. Mol Ther 2012;20(4):699–708; doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lisowski L, Dane AP, Chu K, et al. Selection and evaluation of clinically relevant AAV variants in a xenograft liver model. Nature 2014;506(7488):382–386; doi: 10.1038/nature12875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Biswas M, Marsic D, Li N, et al. Engineering and in vitro selection of a novel AAV3B variant with high hepatocyte tropism and reduced seroreactivity. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2020;19:347–361; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marsic D, Govindasamy L, Currlin S, et al. Vector design Tour de Force: integrating combinatorial and rational approaches to derive novel adeno-associated virus variants. Mol Ther 2014;22(11):1900–1909; doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grimm D, Buning H. Small but increasingly mighty: Latest advances in AAV vector research, design, and evolution. Hum Gene Ther 2017;28(11):1075–1086; doi: 10.1089/hum.2017.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bartel MA, Weinstein JR, Schaffer DV. Directed evolution of novel adeno-associated viruses for therapeutic gene delivery. Gene Ther 2012;19(6):694–700; doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li W, Asokan A, Wu Z, et al. Engineering and selection of shuffled AAV genomes: a new strategy for producing targeted biological nanoparticles. Mol Ther 2008;16(7):1252–1260; doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cabanes-Creus M, Navarro RG, Zhu E, et al. Novel human liver-tropic AAV variants define transferable domains that markedly enhance the human tropism of AAV7 and AAV8. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2022;24:88–101; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang L, Bell P, Somanathan S, et al. Comparative study of liver gene transfer with AAV vectors based on natural and engineered AAV capsids. Mol Ther 2015;23(12):1877–1887; doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vercauteren K, Hoffman BE, Zolotukhin I, et al. Superior in vivo transduction of human hepatocytes using engineered AAV3 capsid. Mol Ther 2016;24(6):1042–1049; doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li S, Ling C, Zhong L, et al. Efficient and targeted transduction of nonhuman primate liver with systemically delivered optimized AAV3B vectors. Mol Ther 2015;23(12):1867–1876; doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ran G, Chen X, Xie Y, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis improves the transduction efficiency of capsid library-derived recombinant AAV vectors. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2020;17:545–555; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ito M, Takino N, Nomura T, et al. Engineered adeno-associated virus 3 vector with reduced reactivity to serum antibodies. Sci Rep 2021;11(1):9322; doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88614-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Daniel HD, Kumar S, Kannangai R, et al. Prevalence of adeno-associated virus 3 capsid binding and neutralizing antibodies in healthy and hemophilia B individuals from India. Hum Gene Ther 2021;32(9–10):451–457; doi: 10.1089/hum.2020.258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ling C, Wang Y, Feng YL, et al. Prevalence of neutralizing antibodies against liver-tropic adeno-associated virus serotype vectors in 100 healthy Chinese and its potential relation to body constitutions. J Integr Med 2015;13(5):341–346; doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(15)60200-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pei X, Shao W, Xing A, et al. Development of AAV variants with human hepatocyte tropism and neutralizing antibody escape capacity. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2020;18:259–268; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. de Alencastro G, Pekrun K, Valdmanis P, et al. Tracking adeno-associated virus capsid evolution by high-throughput sequencing. Hum Gene Ther 2020;31(9–10):553–564; doi: 10.1089/hum.2019.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Crosson SM, Dib P, Smith JK, et al. Helper-free production of laboratory grade AAV and purification by iodixanol density gradient centrifugation. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2018;10:1–7; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Aurnhammer C, Haase M, Muether N, et al. Universal real-time PCR for the detection and quantification of adeno-associated virus serotype 2-derived inverted terminal repeat sequences. Hum Gene Ther Methods 2012;23(1):18–28; doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2011.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bissig-Choisat B, Wang L, Legras X, et al. Development and rescue of human familial hypercholesterolaemia in a xenograft mouse model. Nat Commun 2015;6:7339; doi: 10.1038/ncomms8339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zou C, Vercauteren KOA, Michailidis E, et al. Experimental variables that affect human hepatocyte AAV transduction in liver chimeric mice. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2020;18:189–198; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Meliani A, Leborgne C, Triffault S, et al. Determination of anti-adeno-associated virus vector neutralizing antibody titer with an in vitro reporter system. Hum Gene Ther Methods 2015;26(2):45–53; doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2015.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Michailidis E, Vercauteren K, Mancio-Silva L, et al. Expansion, in vivo-ex vivo cycling, and genetic manipulation of primary human hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(3):1678–1688; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919035117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vanwolleghem T, Libbrecht L, Hansen BE, et al. Factors determining successful engraftment of hepatocytes and susceptibility to hepatitis B and C virus infection in uPA-SCID mice. J Hepatol 2010;53(3):468–476; doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kawahara T, Toso C, Douglas DN, et al. Factors affecting hepatocyte isolation, engraftment, and replication in an in vivo model. Liver Transpl 2010;16(8):974–982; doi: 10.1002/lt.22099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Billerbeck E, Mommersteeg MC, Shlomai A, et al. Humanized mice efficiently engrafted with fetal hepatoblasts and syngeneic immune cells develop human monocytes and NK cells. J Hepatol 2016;65(2):334–343; doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ling C, Wang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Selective in vivo targeting of human liver tumors by optimized AAV3 vectors in a murine xenograft model. Hum Gene Ther 2014;25(12):1023–1034; doi: 10.1089/hum.2014.099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gao GP, Alvira MR, Wang L, et al. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99(18):11854–11859; doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jungmann A, Muller O, Rapti K. Cell-based measurement of neutralizing antibodies against adeno-associated virus (AAV). Methods Mol Biol 2017;1521:109–126; doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6588-5_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Steven W, Pipe MR, Key NS, et al. First data from the phase 3 HOPE-B gene therapy trial: Efficacy and safety of etranacogene dezaparvovec (AAV5-Padua hFIX variant; AMT-061) in adults with severe or moderate-severe hemophilia B treated irrespective of pre-existing anti-capsid neutralizing antibodies. Blood 2020;136:LBA-6; doi: 10.1182/blood-2020-143560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sen D, Balakrishnan B, Gabriel N, et al. Improved adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 1 and 5 vectors for gene therapy. Sci Rep 2013;3:1832; doi: 10.1038/srep01832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Agbandje-McKenna M, Kleinschmidt J. AAV capsid structure and cell interactions. Methods Mol Biol 2011;807:47–92; doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-370-7_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mietzsch M, Jose A, Chipman P, et al. Completion of the AAV structural atlas: Serotype capsid structures reveals clade-specific features. Viruses 2021;13(1):101; doi: 10.3390/v13010101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Govindasamy L, DiMattia MA, Gurda BL, et al. Structural insights into adeno-associated virus serotype 5. J Virol 2013;87(20):11187–11199; doi: 10.1128/JVI.00867-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lerch TF, Xie Q, Chapman MS. The structure of adeno-associated virus serotype 3B (AAV-3B): Insights into receptor binding and immune evasion. Virology 2010;403(1):26–36; doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. FDA. Toxicity Risks of Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) Vectors for Gene Therapy (GT). Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee (CTGTAC) Meeting #70, Food and Drug Administration, United States, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chand DH, Zaidman C, Arya K, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy following onasemnogene abeparvovec for spinal muscular atrophy: A case series. J Pediatr 2021;231:265–268; doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bonnemann CB, Braun S, Morris C, et al. A Collaborative Analysis by Clinical Trial Sponsors and Academic Experts of Anti-Transgene SAES in Studies of Gene Therapy for DMD. In: 2022. Muscular Dystrophy Association conference 2022. Conference abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Konkle BA, Walsh CE, Escobar MA, et al. BAX 335 hemophilia B gene therapy clinical trial results: Potential impact of CpG sequences on gene expression. Blood 2021;137(6):763–774; doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hamilton BA, Wright JF. Challenges posed by immune responses to AAV vectors: Addressing root causes. Front Immunol 2021;12:675897; doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.675897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Paulk NK, Pekrun K, Zhu E, et al. Bioengineered AAV capsids with combined high human liver transduction in vivo and unique humoral seroreactivity. Mol Ther 2018;26(1):289–303; doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Grimm D, Lee JS, Wang L, et al. In vitro and in vivo gene therapy vector evolution via multispecies interbreeding and retargeting of adeno-associated viruses. J Virol 2008;82(12):5887–5911; doi: 10.1128/JVI.00254-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ling C, Lu Y, Kalsi JK, et al. Human hepatocyte growth factor receptor is a cellular coreceptor for adeno-associated virus serotype 3. Hum Gene Ther 2010;21(12):1741–1747; doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Govindasamy L, Padron E, McKenna R, et al. Structurally mapping the diverse phenotype of adeno-associated virus serotype 4. J Virol 2006;80(23):11556–11570; doi: 10.1128/JVI.01536-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Tseng YS, Agbandje-McKenna M.. Mapping the AAV capsid host antibody response toward the development of second generation gene delivery vectors. Front Immunol 2014;5:9; doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Havlik LP, Simon KE, Smith JK, et al. Coevolution of adeno-associated virus capsid antigenicity and tropism through a structure-guided approach. J Virol 2020;94(19):e00976-20; doi: 10.1128/JVI.00976-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Perocheau DP, Cunningham S, Lee J, et al. Age-related seroprevalence of antibodies against AAV-LK03 in a UK population cohort. Hum Gene Ther 2019;30(1):79–87; doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. van der Marel S, Comijn EM, Verspaget HW, et al. Neutralizing antibodies against adeno-associated viruses in inflammatory bowel disease patients: implications for gene therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17(12):2436–2442; doi: 10.1002/ibd.21673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pipe SW, Recht M, Key NS, et al. Durability of bleeding protection and factor IX activity levels are demonstrated in individuals with and without adeno-associated virus serotype 5 neutralizing antibodies (titers <1:700) with comparable safety in the phase 3 HOPE-B clinical trial of etranacogene dezaparvovec gene therapy for hemophilia B. Blood 2022;140:4904–4906; doi: 10.1182/blood-2022-166745 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Majowicz A, Nijmeijer B, Lampen MH, et al. Therapeutic hFIX activity achieved after single AAV5-hFIX treatment in hemophilia B patients and NHPs with pre-existing anti-AAV5 NABs. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2019;14:27–36; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nonnenmacher M, Wang W, Child MA, et al. Rapid evolution of blood-brain-barrier-penetrating AAV capsids by RNA-driven biopanning. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2021;20:366–378; doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Westhaus A, Cabanes-Creus M, Jonker T, et al. AAV-p40 bioengineering platform for variant selection based on transgene expression. Hum Gene Ther 2022;33(11–12):664–682; doi: 10.1089/hum.2021.278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Recombinant AAV3B sequences are available in GenBank.