Keywords: genetic kidney disease, clinical epidemiology, glomerular disease, chronic kidney disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, apolipoprotein L1, genotype

Abstract

Significance Statement

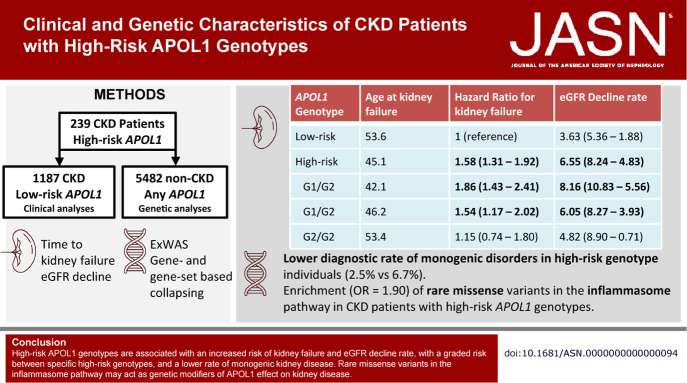

APOL1 high-risk genotypes confer a significant risk of kidney disease, but variability in patient outcomes suggests the presence of modifiers of the APOL1 effect. We show that a diverse population of CKD patients with high-risk APOL1 genotypes have an increased lifetime risk of kidney failure and higher eGFR decline rates, with a graded risk among specific high-risk genotypes. CKD patients with high-risk APOL1 genotypes have a lower diagnostic yield for monogenic kidney disease. Exome sequencing revealed enrichment of rare missense variants within the inflammasome pathway modifying the effect of APOL1 risk genotypes, which may explain some clinical heterogeneity.

Background

APOL1 genotype has significant effects on kidney disease development and progression that vary among specific causes of kidney disease, suggesting the presence of effect modifiers.

Methods

We assessed the risk of kidney failure and the eGFR decline rate in patients with CKD carrying high-risk (N=239) and genetically matched low-risk (N=1187) APOL1 genotypes. Exome sequencing revealed monogenic kidney diseases. Exome-wide association studies and gene-based and gene set–based collapsing analyses evaluated genetic modifiers of the effect of APOL1 genotype on CKD.

Results

Compared with genetic ancestry-matched patients with CKD with low-risk APOL1 genotypes, those with high-risk APOL1 genotypes had a higher risk of kidney failure (Hazard Ratio [HR]=1.58), a higher decline in eGFR (6.55 versus 3.63 ml/min/1.73 m2/yr), and were younger at time of kidney failure (45.1 versus 53.6 years), with the G1/G1 genotype demonstrating the highest risk. The rate for monogenic kidney disorders was lower among patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes (2.5%) compared with those with low-risk genotypes (6.7%). Gene set analysis identified an enrichment of rare missense variants in the inflammasome pathway in individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes and CKD (odds ratio=1.90).

Conclusions

In this genetically matched cohort, high-risk APOL1 genotypes were associated with an increased risk of kidney failure and eGFR decline rate, with a graded risk between specific high-risk genotypes and a lower rate of monogenic kidney disease. Rare missense variants in the inflammasome pathway may act as genetic modifiers of APOL1 effect on kidney disease.

Introduction

Individuals of African ancestry are at an increased risk of developing CKD and in the United States carry a three-fold increased risk of incident kidney failure compared with Americans of European ancestry.1–3 This is attributable to interacting environmental, social, and genetic factors.4 The G1 and G2 APOL1 alleles are unique because they are strongly associated with kidney disease while being common in populations of sub-Saharan African ancestry and therefore account for a significant portion of these ancestry-based differences.5–7 In the United States, the G1 and G2 alleles are most common in Americans of sub-Saharan African ancestry, where up to 15% have high-risk genotypes and are very rare in Americans of European ancestry.8–10

In individuals with and without prevalent kidney disease, high-risk APOL1 genotypes are associated with an increased rate of decline in eGFR and an increased risk of incident proteinuria and kidney failure.5,6,11–13 Despite this, only 15%–20% of individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes develop kidney disease in their lifetime.11,12 In addition, the effect of APOL1 risk genotype is highly variable between specific kidney diseases, and self-declared Black ancestry is associated with more rapid progression independent of APOL1 genotype, suggesting the presence of modifiers.14,15,16 One known modifier is elevations in interferon levels, which induce APOL1 expression in podocytes, potentially explaining the HIV and SARS-CoV-2–associated collapsing glomerulopathy seen in individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes.5,10,15–20 Recent studies have implicated the NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis in interferon-induced APOL1 cytotoxicity, suggesting these pathways as potential modifiers for APOL1-associated phenotypes.16,17,21,22

Several studies have attempted to identify genetic modifiers of the effect of APOL1 risk genotype on kidney disease, but no strong signals have been identified and replicated. A gene-based collapsing analysis applied to a smaller sample from the same biobank used for this study identified a suggestive enrichment of rare, nonbenign variants in the AHDC1 gene in individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes and CKD.23 Admixture mapping in individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes and FSGS found an increase in African ancestry at the UBD locus that correlated with lower UBD expression and increased APOL1-mediated cytotoxicity suggesting a role as a modifier.14 A relatively small genome-wide association study of common variants did not identify any significant associations or interactions with APOL1 risk genotype and did not replicate AHDC1 or UBD leaving us with a limited understanding of the genetic architecture of APOL1-associated kidney disease.24

Here we studied the effect of APOL1 risk genotype on the risk of kidney failure and the rate of eGFR decline in a large, ethnically diverse, cohort with all-cause CKD. We used exome sequencing data to genetically match individuals with high- and low-risk APOL1 genotypes and compared the impact of genetically determined and self-declared ancestry on outcomes.

Exome sequencing was also used to evaluate individuals for monogenic kidney disease and novel APOL1 variants. Finally, genetic modifiers of kidney disease in individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes were evaluated using an exome-wide association study (ExWAS) and gene-based and gene set–based collapsing analyses.

Methods

Study Population and Design

Individuals with CKD at New York Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City, NY, were recruited between October 2013 and July 2021 into the Genetic Studies of Chronic Kidney Disease biobank with Columbia University Institutional Review approval. All participants provided informed consent. So far 4388 individuals from the biobank had undergone exome sequencing following standard protocols at the Institute for Genomic Medicine (IGM) at Columbia University (Supplemental Methods).23,25 Retrieval, annotation, and filtering of variants were performed using analysis tool for annotated variants (ATAV).26

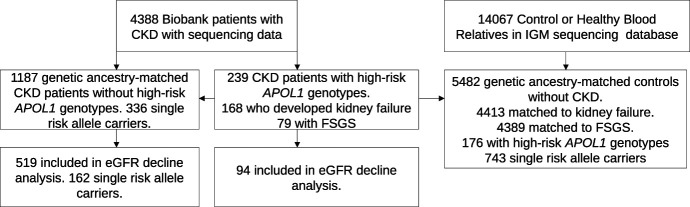

APOL1 risk genotypes were defined by the presence of the G1 (G1G 22-36661906-A-G [rs73885319] and G1M 22-36662034-T-G [rs60910145]) and G2 (22-36662041-AATAATT-A [s71785313]) alleles. Within the biobank, 239 individuals were identified with high-risk APOL1 genotypes (genotypes G1/G1, G2/G2, or G1/G2) along with a comparison cohort of 1187 genetic ancestry-matched individuals without high-risk APOL1 genotypes, including 336 single risk allele carriers that have either the G1/G0 or G2/G0 genotypes, selected by Louvain clustering of 12,400 informative genetic ancestry markers (Figure 1, Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Methods).26,27 Louvain clustering was used because it does not require the number of ground truth clusters to be known and does not make assumptions about cluster size, density, or shape.28 Clinical data were collected at recruitment and updated from the electronic health record (EHR). Descriptive statistics were performed in R 4.0.3 (R Core Team, Vienna Austria).29

Figure 1.

Patient flow within the study. IGM, Institute for Genomic Medicine.

Analysis of Clinical Diagnosis

The association of APOL1 risk alleles with common primary causes of kidney disease was evaluated using logistic regression. Patients with CKD with a diagnosis of either autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease or congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract were used as a reference cohort because these disorders are not known to be associated by APOL1 genotype. This analysis was adjusted for sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, genetic ancestry cluster, quintile of the median income of their home ZIP code as an area-based surrogate of socioeconomic status, and International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10–based Swiss AHQI Elixhauser comorbidity score.30–32 Missing Elixhauser comorbidity score and ZIP code–based median income data were imputed using multiple imputations by chained equations (Supplemental Methods).33

Time to Event Analyses

Kaplan-Meier, Cox proportional hazard, and Fine-Gray competing risk models were used to evaluate the onset of kidney failure (defined as chronic dialysis or kidney transplantation) with a median of 3.5 years of follow-up data.34,35 Cox proportional hazard and Fine-Gray competing risk models were performed unadjusted and adjusted for sex, family history of kidney disease, presence of monogenic kidney disease diagnosis, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, genetic ancestry cluster, quintile of the median income of their home ZIP code as an area-based surrogate of socioeconomic status, and ICD-10–based Swiss AHQI Elixhauser comorbidity score.30–32 The proportional-hazard assumptions were met with the inclusion of time-varying covariates. The effects of specific high-risk APOL1 genotypes, single allele carrier status, and the interaction of clinical diagnosis and APOL1 genotype were evaluated in secondary analyses.

eGFR Decline Analysis

Patients with CKD with two or more serum creatinine measurements collected at least 1 year apart were included. Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI 2021) without race term was used to eGFR.36,37 Values collected at younger than 14.2 years, where the CKD-EPI formula loses accuracy, and after the initiation of dialysis or transplantation were excluded.38 Ninety-four patients with CKD (2216 creatinine values) with high-risk APOL1 genotypes were compared with 519 genetic ancestry-matched patients with CKD (20,869 creatinine values) without high-risk APOL1 genotypes which included 162 (6916 creatinine values) single-risk allele carriers. A median of 5.5 years of data and 21 creatinine values were available per individual. Linear mixed-effects modeling evaluated the eGFR decline rate using a random slope and intercept for each subject, nested within their primary cause of kidney disease and fixed effects for APOL1 risk genotype, family history of kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, initial eGFR value, and genetic ancestry cluster.39,40 The interaction term of APOL1 risk genotype and time since the first creatinine value represented the decline in eGFR per unit time. Numeric variables were centered and scaled. As a secondary analysis, the effects of specific high-risk APOL1 genotypes and single-risk allele carrier status were evaluated. Fixed-effect confidence intervals were estimated using parametric bootstrapping.

Diagnostic Analysis of Monogenic Kidney Disorders

Sequencing data were analyzed using ATAV to identify pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants diagnostic of an individual's kidney disease using a curated list of 625 genes known to cause kidney disease.41 Variant interpretation followed the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) guidelines with the implementation of criteria updates recommended by the ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation working group.42 Diagnostic variants were reviewed at multidisciplinary genetic sign-out rounds and reached consensus interpretation and are considered returnable after Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)–certified lab confirmation. APOL1 high-risk genotypes are also considered returnable after CLIA confirmation. Variants that did not fit the individual's kidney disease phenotype were considered nondiagnostic. Novel APOL1 coding variants were also analyzed. The diagnostic rate based on APOL1 risk genotype was compared using logistic regression with self-described race and ethnicity and family history as covariates.

Exome-Based Association Studies

The 239 patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes were compared with a genetic ancestry-matched comparison cohort without CKD selected using Louvain clustering.43 After quality control (QC), coverage harmonization and kinship pruning 232 patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes remained and were compared with 5482 genetic ancestry-matched controls without CKD from the IGM sequencing database (Figure 1, Supplemental Methods). In addition to the full cohort, two a priori subgroup analyses were performed, examining those who developed kidney failure (168 patients; 4413 matched controls) representing the most severely affected individuals and those with FSGS (79 patients; 4389 matched controls) which has been strongly associated with APOL1 risk genotype.18

To search for potential genetic modifiers of the effect of APOL1 genotype on kidney disease, we first conducted a single-variant association study using Regenie 2.0 (Supplemental Methods).44 Sex and the first ten principle components were included as covariates. GCTA 1.93.3 was used to perform conditional analysis where loci P-values are recalculated by conditioning on the top loci signal.45,46 The conditional analysis was repeated by selecting the new top loci signal until no new signals reached the prespecified significance threshold. The approximate Firth likelihood ratio test was used to evaluate the association between single variants and disease status. The ExWAS significance threshold was adjusted for the total number of exome-wide variants tested across the three analyses using a q value significance threshold of Q<0.05.

We next performed a rare-variant gene-based collapsing analysis, applying one recessive and 11 dominant nonsynonymous models for selecting qualifying variants (QVs) (Supplemental Table 1). The work flow, QC, and coverage harmonization followed prior published reports (Supplemental Methods).23,47,48 One hundred thirty-seven of the identified patients with high-risk APOL1 genotypes included in this analysis were used in a published gene-based collapsing analysis of patients with CKD.23

Finally, we conducted gene set–based collapsing analysis with three predefined gene sets: (1) the pyroptosis gene set, (2) the inflammasome gene set, and (3) known autosomal recessive kidney disease genes (Supplemental Table 2). These gene sets were evaluated across all 12 models from the rare-variant gene-based collapsing analysis (Supplemental Table 1). Gene and gene set analyses used the exact two-sided Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test of independence across ancestry clusters and a q value significance threshold of Q<0.05.49 Once a suggestive signal was identified, we conducted two follow-up analyses for the pyroptosis and inflammasome gene sets. The first compared patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes (N=232) with controls with high-risk APOL1 genotypes without CKD (N=176) to assess whether enrichment was due to high-risk APOL1 genotype independent of CKD status and is termed high-risk only. The second analysis compared patients with CKD with one APOL1 risk allele (N=339) with controls with 0 APOL1 risk alleles without CKD (N=4563) to assess whether enrichment was instead associated with CKD in the absence of high-risk APOL1 genotypes and is termed APOL1 het.

Results

Study Population

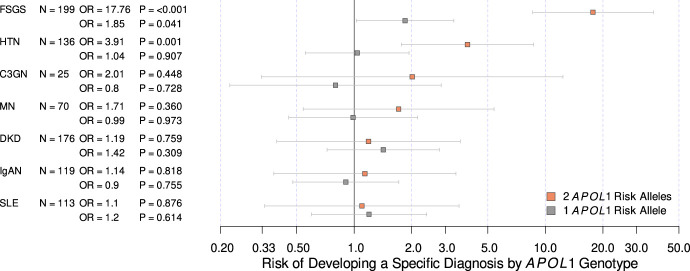

Baseline characteristics of the 239 patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes and 1187 genetic ancestry-matched patients with CKD with low-risk APOL1 genotypes are summarized in Table 1. Novel rare variants in APOL1 were identified in the low-risk genotype cohort, but not in the high-risk genotype cohort (Supplemental Table 3). A large proportion of individuals with high-risk and low-risk genotypes self-reported their race and ethnicity as Black or African American and not Hispanic or Latinx (61% and 22%, respectively) or White and Hispanic or Latinx (17% and 36%, respectively). Patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes were more likely to carry a primary diagnosis of FSGS and hypertension-attributed CKD (odds ratio [OR], 17.76, 3.91; P=6.1×10−14, 8.3×10−4, respectively; Figure 2, Table 2). In addition, we noted an increased risk of FSGS in those with a single APOL1 risk allele (OR, 1.85; P=0.041).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline data of included patients with CKD, characterized by APOL1 risk genotype

| Sample Characteristics | Low-Risk Genotype | High-Risk Genotype |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 1187 | 239 |

| Biologic sex, female, no. (%) | 564 (48) | 105 (44) |

| Age at recruitment, yr, median (IQR) | 43.7 (27.9–57.8) | 43.4 (30.2–54.6) |

| Age at last follow-up, yr, median (IQR) | 48.4 (32.1–62.2) | 48.8 (35.9–59.3) |

| Follow-up time, yr, median (IQR) | 3.7 (0–6.1) | 3.7 (0–7.1) |

| Pediatric at recruitment, no. (%) | 149 (13) | 4 (2) |

| Developed kidney failure, no. (%) | 630 (53) | 168 (70) |

| Age at kidney failure, yr, median (IQR) | 43.3 (30.5–55.4) | 40.6 (28.0–50.2) |

| Received kidney transplant, no. (%) | 538 (45) | 150 (63) |

| Family history of kidney disease, no. (%) | 399 (34) | 83 (35) |

| Initial eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 mean (IQR) | 57.9 (33.2–97.6) | 49.7 (34.5–81.7) |

| Self-described race and ethnicity, no. (%) | ||

| Asian, Hispanic or Latinx | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Asian, not Hispanic or Latinx | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| Black/African American, Hispanic or Latinx | 70 (6) | 14 (6) |

| Black/African American, not Hispanic or Latinx | 294 (25) | 149 (61) |

| Black/African American, unspecified ethnicity | 5 (0.4) | 2 (1) |

| Native American, Hispanic or Latinx | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown or preferred not to specify, Hispanic or Latinx | 265 (22) | 16 (7) |

| Unknown or preferred not to specify, not Hispanic or Latinx | 41 (3) | 1 (0.4) |

| Unknown or preferred not to specify, unspecified ethnicity | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| White, Hispanic or Latinx | 428 (36) | 41 (17) |

| White, not Hispanic or Latinx | 62 (5) | 15 (6) |

| White, unspecified ethnicity | 7 (0.6) | 0 (0) |

| Genetic ancestry cluster, no. (%) | ||

| Majority Black/African American | 364 (31) | 170 (71) |

| Majority Hispanic or Latinx | 195 (16) | 5 (2) |

| Admixed connecting cluster | 628 (53) | 64 (27) |

| ZIP code median income (by quintile), no. (%) | ||

| 1 (highest) | 33 (3) | 3 (1) |

| 2 | 355 (30) | 71 (30) |

| 3 | 515 (43) | 102 (43) |

| 4 | 218 (18) | 52 (22) |

| 5 (lowest) | 18 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Missing | 48 (4) | 8 (3) |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 452 (38) | 108 (45) |

| Diabetes mellitus, no. (%) | 183 (12) | 37 (15) |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score, median (IQR) | 5 (0–9) | 7 (4–8) |

| Missing, no. (%) | 450 (38) | 86 (36) |

Intra-quartile range, IQR.

Figure 2.

Risk of developing specific kidney diseases based on the number of APOL1 risk alleles. The comparison group is composed of individuals with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Adjusted for family history of kidney disease, sex, ZIP code–based median income, genetic ancestry cluster, Elixhauser comorbidity score, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. C3GN, C3 glomerulopathy; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; HTN, hypertension-associated nephropathy; IgAN, IgA nephropathy; MN, membranous nephropathy; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Table 2.

Most common primary causes of kidney disease by APOL1 risk genotype

| Clinical Diagnosis | Low-Risk APOL1 Genotype, no. (%) | Single Risk Allele G1 or G2, no. (%) | High-Risk APOL1 Genotype, no. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSGS | 108 (9) | 35 (10) | 91 (38) |

| FSGS developing kidney failure | 42 (39) | 14 (40) | 51 (56) |

| C1q nephropathy | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 5 (5) |

| H-CKD | 103 (9) | 34 (10) | 33 (14) |

| H-CKD developing kidney failure | 79 (77) | 25 (74) | 33 (100) |

| LN | 103 (9) | 37 (11) | 10 (4) |

| LN developing kidney failure | 48 (47) | 23 (62) | 8 (80) |

| CAKUT | 148 (12) | 28 (8) | 11 (5) |

| IgA nephropathy | 112 (9) | 23 (7) | 7 (3) |

| DKD | 159 (13) | 50 (15) | 17 (7) |

| DKD developing kidney failure | 136 (86) | 45 (90) | 15 (88) |

| Membranous nephropathy | 62 (5) | 20 (6) | 8 (3) |

| ADPKD | 48 (4) | 17 (5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Other | 334 (28) | 96 (29) | 61 (26) |

Other includes: membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, ANCA vasculitis, anti-GBM disease, minimal change disease, chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis, Alport syndrome, thin basement membrane disease, nephrolitiasis, Gitelman syndrome, thrombotic microangiopathy, amyloidosis, nephronophthisis, medullary cystic kidney disease, sarcoidosis, Bartter syndrome, preeclampsia, scleroderma, and tuberous sclerosis. H-CKD, hypertension-associated CKD; LN, lupus nephritis; CAKUT, congenital anomalies of kidney and urinary tract; DKD, diabetic kidney disease; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

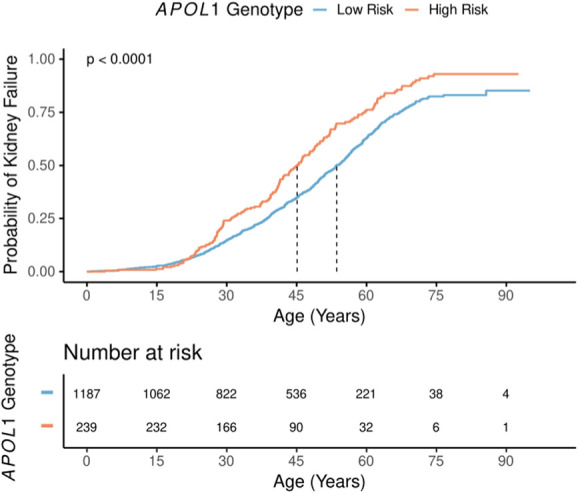

Lifetime Risk of Kidney Failure and Rate of eGFR Decline

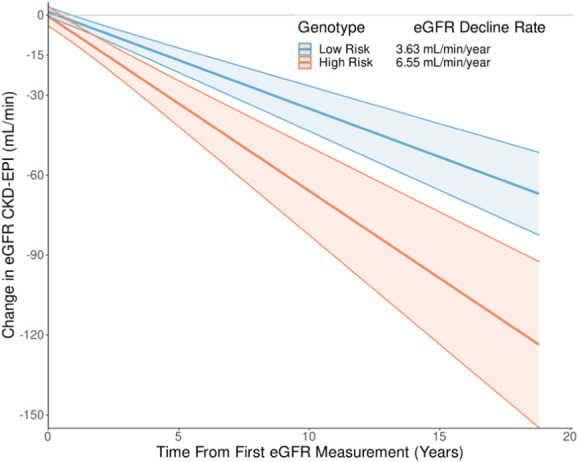

This analysis included 239 patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes and 1187 genetic ancestry-matched patients with CKD with low-risk genotypes. Patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes were younger at kidney failure compared with those with low-risk genotypes (45.1 versus 53.6 years; log rank P=2.0×10−6; Figure 3, Table 3). In the adjusted model, patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes were at an increased lifetime risk of developing kidney failure compared with those with low-risk genotypes (HR, 1.58; P=1.5×10−6; Table 3). The inclusion of the competing risk of death showed similar results (HR, 1.59; P=2.7×10−6; Table 3). Similarly, patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes experienced a higher rate of eGFR decline compared with those with low-risk genotypes (6.55 versus 3.63 ml/min/1.73 m2/yr; P=6.9×10−4; Figure 4, Table 3). We also detected a significant interaction between APOL1 risk genotype and lupus nephritis for the risk of kidney failure, but not with other primary diagnoses (OR, 2.41; P=0.027; Supplemental Figure 2). In this genetically matched cohort, only self-declared race and ancestry of Black/African American, Hispanic or Latinx was significantly associated with risk of progression (HR, 1.52; P=0.049) while other self-declared race and ethnicities and genetic ancestry clusters did not have an impact. None of these affected the impact of APOL1 risk genotype on kidney outcomes.

Figure 3.

Lifetime risk of developing kidney failure comparing subjects with high-risk APOL1 genotypes with low-risk APOL1 genotypes. Median time to kidney failure denoted and logrank P-value shown.

Table 3.

Analyses of kidney failure outcomes by APOL1 genotype

| APOL1 Risk Genotype | Number of Subjects | Age at Kidney Failure, yr, Median (95% CI) | Adjusted HR of Kidney Failure (95% CI), P | Competing Risk HR of Kidney Failure (95% CI), P | eGFR Decline Rate, Mean (95% CI, ml/min/1.73 m2/yr), P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-risk | 1187 | 53.6 (51.8 to 55.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 3.63 (5.36–1.88), reference |

| High-risk | 239 | 45.1 (42.0 to 48.7) | 1.58 (1.31 to 1.91), 1.5×10−6 | 1.59 (1.31 to 1.92), 2.7×10−6 | 6.55 (8.24 to 4.83), 6.9×10−4 |

| G1/G1 | 98 | 42.1 (40.5 to 48.9) | 1.88 (1.45 to 2.44), 1.9×10−6 | 1.86 (1.43 to 2.41), 3.7×10−6 | 8.16 (10.83 to 5.56), 8.9×10−4 |

| G1/G2 | 109 | 46.2 (42.0 to 50.0) | 1.53 (1.19 to 1.97), 1.0×10−3 | 1.54 (1.17 to 2.02), 1.8×10−3 | 6.05 (8.27 to 3.93), 0.03 |

| G2/G2 | 32 | 53.4 (42.4 to 66.5) | 1.15 (0.74 to 1.79), 0.54 | 1.15 (0.74 to 1.80), 0.53 | 4.82 (8.90 to 0.71), 0.56 |

Kaplan-Meier and Cox Proportional hazard modeling applied to development of kidney failure, competing risk analysis includes competing risk of death, eGFR decline modeled using linear mixed-effects modeling. Time to event analyses adjusted for sex, ZIP code based median income, genetic ancestry cluster, family history of kidney disease, presence of monogenic kidney disease, Elixhauser comorbidity score, diabetes mellitus and hypertension. eGFR decline adjusted for initial eGFR measurement, genetic ancestry cluster, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, family history of kidney disease, and primary cause of kidney disease. Statistical testing was not corrected for multiple testing.

Figure 4.

eGFR decline from baseline in subjects with high- and low-risk APOL1 genotypes. eGFR decline rate calculated with covariates held at mean values with 95% confidence intervals shown. Adjusted for primary cause of kidney disease, family history of kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, genetic ancestry cluster, and initial measured eGFR. CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration.

In secondary analyses (Table 3, Supplemental Table 4), we noted a graded risk of kidney failure in patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes. The G1/G1 genotype was associated with the highest risk of kidney failure while G1/G2 carried an intermediate risk. Consistent with these data, the G1/G1 genotype group had the highest rate of eGFR decline and developed kidney failure earliest, followed by the G1/G2 genotype, the G2/G2 genotype, and the low-risk genotype groups (Supplemental Figure 3, Supplemental Figure 4). Patients with CKD carrying a single APOL1 risk allele showed a nominally higher rate of eGFR decline compared with those with zero APOL1 risk alleles, but no difference in the risk of kidney failure (4.43 versus 3.23 ml/min/1.73 m2/yr; P=0.066; HR, 1.08; P=0.40; Supplemental Figure 5).

Monogenic Kidney Diseases

There was a lower rate of monogenic diagnoses in patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes (6/239, 2.5%) compared with low-risk genotypes (79/1187, 6.7%; OR, 0.38; P=0.032; Supplemental Table 5), despite similar rates of positive family history (34.7% versus 33.6%).

Positive family history of kidney disease was associated with a diagnosis of monogenic kidney disease, but not a high-risk APOL1 genotype (OR, 3.04, 1.11; P=1.17×10−6, 0.50, respectively). Removing those patients with a monogenic kidney disease did not affect the effect of APOL1 risk genotype on the lifetime risk of kidney failure. There was no difference in the diagnostic rate between the genetic ancestry clusters or between self-reported race and ethnicity. In addition, we identified six individuals with sickle cell anemia and 83 individuals with sickle cell trait with no enrichment based on APOL1 risk genotype.

Exome-Based Association Studies

We analyzed exome sequencing data from CKD patients with high-risk APOL1 genotypes and compared them with genetic ancestry-matched individuals without known kidney disease. Two prespecified subgroups of patients with CKD with kidney failure and FSGS were also analyzed. As expected, the ExWAS identified three independent significant signals after step-wise conditional analysis; the APOL1 G1M allele (OR, 5.17; P=4.52×10−78; Q=5.94×10−73), the APOL1 G2 allele (OR, 3.74; P=2.48×10−33; Q=1.63×10−28), and the synonymous variant 22-36661842-G-A which forms part of the G3 haplotype in APOL1 (OR, 0.16; P=1.90×10−7; Q=0.015).50 Within the gene-based collapsing analyses, no genes reached the prespecified level of significance (Supplemental Table 6, Supplemental Table 7). The top two enrichment signals were within the subgroup of individuals with FSGS, in the genes DHDH (OR, 38.75; 95% CI, 7.42 to 187; P=2.33×10−5; Q=1.00) and NLRP1 (OR, 13.00; 95% CI, 4.20 to 34.19; P=2.33×10−5; Q=1.00). We did not find any compelling signals in the previously reported UBD or AHDC1 genes.

Gene set–based collapsing analyses demonstrated a significant enrichment of rare missense variants within the inflammasome gene set in the full CKD patient cohort and the subgroup with kidney failure (OR, 1.90, 2.03; P=0.0005, 0.0008; Q=0.038, 0.041, respectively; Supplemental Table 8). This was driven by 57 QVs in 45 patients with CKD, none of which have been associated with disease in the literature (Supplemental Table 9). The enrichment remained significant when patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes were compared with non-CKD patients with high-risk APOL1 genotypes (OR, 3.31; P=0.0005; Q=0.038), but not when single-risk allele APOL1 carriers with CKD were compared with patients with non-CKD with zero risk alleles (OR, 0.46; P=0.0166; Q=0.277), indicating specificity of the inflammasome signal to the CKD group with high-risk APOL1 genotypes. No significant signals were identified in the pyroptosis gene set or within autosomal recessive kidney disease genes (Supplemental Table 8).

Discussion

In this study of a diverse cohort of patients with CKD, which included a large Hispanic and Latinx population, we confirmed that high-risk APOL1 genotypes conferred an increased risk of developing kidney failure (HR, 1.58) and a higher rate of eGFR decline (difference of 2.92 ml/min/1.73 m2/yr). We found a graded risk between high-risk genotypes, where G1/G1 was most affected. By including individuals with all causes of kidney disease, we found that those with high-risk APOL1 genotypes were more likely to have a diagnosis of FSGS or hypertension-attributed CKD. There was also evidence that individuals with a single APOL1 risk allele were more likely to have FSGS which had previously only been described in association with HIV-associated nephropathy.18 The diagnostic rate of exome sequencing for monogenic kidney diseases was lower in individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes. While the analysis of genetic modifiers of the effect of APOL1 genotype on kidney disease did not yield any genome-wide significant genes or loci, there were suggestive signals in the inflammasome pathway in the gene set analysis.

This report supports prior work showing an increased risk of kidney failure, higher rates of eGFR decline, and an enrichment of FSGS and hypertension-associated kidney disease in individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes.5,11,13,51 Compared with prior reports, we studied an ethnically diverse population where the high- and low-risk genotype groups were genetically matched for ancestry and identified patients with monogenic diagnoses of kidney disease. The availability of genetic information reduced the potential confounding effect of ancestry and concomitant monogenic disease on progression. Our results also align with prior studies showing that patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes develop kidney failure 7–9 years earlier than those without a high-risk genotype which has important prognostic implications for these individuals.52,53 Our study did identify a small residual effect of self-declared Black/African American, Hispanic or Latinx race and ethnicity on renal outcomes, after APOL1 risk genotype and genetic ancestry was taken into account. Recent data also suggest that the polygenic score for kidney disease may predict future risk of progression.54 Hence, incorporation of the genome-wide polygenic score may help in improved risk prediction in patients with high-risk APOL1 genotypes.

We identified a graded risk between specific high-risk APOL1 genotypes, with the G1/G1 genotype associated with the highest risk, in concordance with allele-specific effects that have been reported in assays of antitrypanosomal activity and in model systems of APOL1-associated kidney disease.7,55–57 The APOL1 G2 allele provided resistance to serum resistance–associated protein (SRA) producing Trypanosoma brucei rhodesience by abolishing the interaction of SRA with APOL1; however, the G1 allele only had a moderate effect on the SRA-APOL1 interaction, suggesting it may lead to protection through other mechanisms, such as increased cytotoxicity.7,57 In addition, individuals with the G1 allele who are infected by T. b. gambiense, which causes most of the human diseases, more often develop a state of asymptomatic carriage, while those with the G2 allele are more likely to have clinically overt disease, further supporting allele-specific effects.55 These findings highlight the importance of separating specific high-risk APOL1 genotypes in future analyses of observational and clinical trials because of potential differences in prognosis. In addition, the nominal trend toward a higher rate of eGFR decline in subjects with a single APOL1 risk allele is consistent with studies showing increased risk of kidney failure, CKD, cardiovascular disease, and cardiomyopathy in additive models of APOL1 risk variants, suggesting that heterozygotes carry some increased risk.52,58,59

The lower diagnostic rate of exome sequencing for monogenic kidney disease in patients with CKD with high-risk APOL1 genotypes suggests that dual genetic diagnoses are rarer in this patient population. Although a family history of kidney disease was predictive of a diagnosis of monogenic kidney disease, it was not predictive of APOL1 risk genotype, implicating additional factors such as polygenic background or environmental effects as contributors to the effect of family history in this group.25,60 These data are important for clinicians selecting patients for genetic testing.

The gene-based collapsing analyses did not identify significant modifiers of the effect of APOL1 genotype, including the previously suggested modifiers AHDC1 and UBD.14,23 The suggestive signals in NLRP1 and the inflammasome gene set are noteworthy because this pathway has been implicated in APOL1-mediated cytotoxicity.61 The cytotoxicity of APOL1 risk variants may be due to increased expression after viral infections, inflammation, and interferon signaling.15,19 In model systems of APOL1-associated kidney disease, overexpression of APOL1 risk variants was shown to stimulate both the simulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway and the inflammasome and ultimately lead to podocyte death by pyroptosis.21 This cellular injury was attenuated by genetic depletion of either NLRP3 or GSDMD within the inflammasome or the STING gene. Hence, genetic variants within these pathways may be plausible modifiers of the effect of APOL1 risk genotype.

This study's limitations include the single-center design which may introduce unmeasured center-specific practices in the analyses, such as medication usage, the timing of initiation of kidney replacement therapy, and transplantation referral. In the process of genetic ancestry-matching, only one African ancestry dominant cluster was identified, suggesting that the cohort did not capture the full spectrum of genetic diversity in Africa.8,9 The use of clinically collected creatinine values may produce variation because of differences in laboratory measurements. We included both inpatient and outpatient creatinine values in this analysis which could include creatinine values that are in flux as patients experience or recover from acute kidney injury; however, the restriction of eGFR analyses to only those individuals with over 1 year of data aimed to reduce the effects of short-term creatinine changes, while the use of subject-specific intercept and slopes within the eGFR slope modeling accounted for subject-specific differences. The computation of comorbidity scores from EHR ICD-10 codes is routinely performed but can introduce bias based on billing and diagnostic patterns. Collapsing analyses carry their own set of limitations including the identification of QVs that are biologically meaningful and sequencing data variability.47 To address this, we used a standardized QC and analysis pipeline that includes coverage harmonization along with measures of missense intolerance and multiple models to identify appropriate QV screening criteria. Power analyses suggest the rare-variant analyses performed were underpowered to identify many interactions with APOL1 genotype, demonstrating the need for larger sample sizes to identify genetic modifiers and confirm the novel clinical associations detected in this study.

In conclusion, we confirmed that high-risk APOL1 genotypes conferred an increased risk of developing kidney failure and a higher rate of eGFR decline and identified a graded risk between high-risk genotypes, where G1/G1 were most affected. In single APOL1 risk allele carriers, we identified an increased risk of FSGS and a trend toward a faster rate of eGFR decline. We found a lower diagnostic rate of exome sequencing for monogenic kidney diseases in individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes and identified suggestive signals in the inflammasome pathway in the gene set analysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all CUIMC participants and investigators who have been involved in the Genetic Studies of Chronic Kidney Disease biobank. M.D. Elliott was supported by a Helios post-fellowship training award from the University of Calgary.

Footnotes

See related editorial, “Phenotypes of APOL1 High-Risk Status Subjects,” on pages 735–736.

Disclosures

A.G. Gharavi reports receiving research grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Renal Research Institute. A.G. Gharavi also reports consultancy: AstraZeneca Center for genomics research, Goldfinch Bio: Actio biosciences, Novartis: Travere; ownership interest: Actio; research funding: Natera; honoraria: Sanofi, Alnylam; and advisory or leadership role: Editorial board: JASN and Journal of Nephrology. G. Povysil is an employee of and has ownership interest in Waypoint Bio. E. Cocchi reports research funding: American Society of Nephrology. H. Milo Rasouly reports research funding: Natera. K. Kiryluk reports consultancy: Calvariate, HiBio; and research funding: AstraZeneca, Vanda, Bioporto, Aevi Genomics, and Visterra. Because A.G. Gharavi is an Associate Editor of the JASN, he was not involved in the peer review process for this manuscript. A guest editor oversaw the peer review and decision-making process for this manuscript.

Funding

Funding institutions: Department of Defence Research Award (Grant/Award Number: PR201425). A. Khan is supported by grants from the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (Grant/Award Numbers: K25DK128563 and UL1TR001873).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Mark D. Elliott, Ali G. Gharavi, Maddalena Marasa.

Data curation: Mark D. Elliott, Maddalena Marasa, Natalie Vena, Jun Y. Zhang.

Formal analysis: Shiraz Bheda, Enrico Cocchi, Mark D. Elliott, Atlas Khan, Sarath Krishna Murthy, Gundula Povysil, Natalie Vena.

Funding acquisition: Ali G. Gharavi, Krzysztof Kiryluk.

Investigation: Mark D. Elliott.

Methodology: Mark D. Elliott, Ali G. Gharavi, Krzysztof Kiryluk, Hila Milo Rasouly.

Project administration: Mark D. Elliott, Maddalena Marasa.

Resources: Ali G. Gharavi, Krzysztof Kiryluk.

Software: Shiraz Bheda, Enrico Cocchi, Mark D. Elliott, Atlas Khan, Sarath Krishna Murthy, Gundula Povysil.

Supervision: Ali G. Gharavi, Krzysztof Kiryluk.

Visualization: Mark D. Elliott.

Writing – original draft: Mark D. Elliott, Ali G. Gharavi.

Writing – review & editing: Shiraz Bheda, Enrico Cocchi, Mark D. Elliott, Ali G. Gharavi, Atlas Khan, Krzysztof Kiryluk, Sarath Krishna Murthy, Maddalena Marasa, Hila Milo Rasouly, Gundula Povysil, Natalie Vena, Jun Y. Zhang.

Data Sharing Statement

Individual level data for 1426 participants with CKD are available through National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) dbGaP database (phs001828.v2.p1, in process).

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/JSN/D761.

Supplemental Table 1. Model characteristic used for gene-based and gene set–based collapsing analyses.

Supplemental Table 2. Gene names used for gene set analyses.

Supplemental Table 3. Novel APOL1 variants identified.

Supplemental Table 4. Expanded demographics and baseline data of included patients with CKD, divided by APOL1 risk genotype, including single-risk allele carriers and specific high-risk genotypes.

Supplemental Table 5. Monogenic kidney diseases identified within the study. Includes variant classification and criteria asserted.

Supplemental Table 6. Top 15 ranked genes across the rare-variant collapsing analysis.

Supplemental Table 7. Top results of the common and rare-variant secondary gene-based burden analysis.

Supplemental Table 8. Results from the gene set–based rare-variant collapsing analysis.

Supplemental Table 9. Qualifying variants identified within the inflammasome gene set within the dominant rare missense model for the full cohort.

Supplemental Figure 1. Genetic ancestry and clustering using principal components analyses of exome ancestry markers on a UMAP projection.

Supplemental Figure 2. Lifetime risk of the development of kidney failure comparing subjects with specific high-risk APOL1 genotypes with low-risk APOL1 genotype.

Supplemental Figure 3. eGFR change over time in subjects by specific APOL1 genotype. eGFR decline rate calculated with covariates held at mean values.

Supplemental Figure 4. Lifetime risk of developing kidney failure for the interaction between APOL1 high-risk genotype and primary cause of kidney disease.

Supplemental Figure 5. eGFR change over time in subjects characterized by number of APOL1 risk alleles.

References

- 1.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US Renal Data System 2019 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(1 suppl 1):A6–A7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trinh E, Na Y, Sood MM, Chan CT, Perl J. Racial differences in home dialysis utilization and outcomes in Canada. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(11):1841–1851. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03820417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathur R, Dreyer G, Yaqoob MM, Hull SA. Ethnic differences in the progression of chronic kidney disease and risk of death in a UK diabetic population: an observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020145. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patzer RE, McClellan WM. Influence of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status on kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(9):533–541. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grams ME, Rebholz CM, Chen Y, et al. Race, APOL1 risk, and eGFR decline in the general population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(9):2842–2850. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015070763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peralta CA, Bibbins-Domingo K, Vittinghoff E, et al. APOL1 genotype and race differences in incident albuminuria and renal function decline. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(3):887–893. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329(5993):841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Limou S, Nelson GW, Kopp JB, Winkler CA. APOL1 kidney risk alleles: population genetics and disease associations. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21(5):426–433. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadkarni GN, Gignoux CR, Sorokin EP, et al. Worldwide frequencies of APOL1 renal risk variants. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2571–2572. doi: 10.1056/nejmc1800748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman DJ, Pollak MR. APOL1 nephropathy: from genetics to clinical applications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(2):294–303. doi: 10.2215/CJN.15161219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, et al. APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(9):1484–1491. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013010113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen TK, Tin A, Peralta CA, et al. APOL1 risk variants, incident proteinuria, and subsequent eGFR decline in Blacks with hypertension-attributed CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(11):1771–1777. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01180117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsa A, Kao WL, Xie D, et al. APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2183–2196. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1310345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J-Y, Wang M, Tian L, et al. UBD modifies APOL1-induced kidney disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(13):3446–3451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716113115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dummer PD, Limou S, Rosenberg AZ, et al. APOL1 kidney disease risk variants—an evolving landscape. Semin Nephrol. 2015;35(3):222–236. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.May RM, Cassol C, Hannoudi A, et al. A multi-center retrospective cohort study defines the spectrum of kidney pathology in Coronavirus 2019 Disease (COVID-19). Kidney Int. 2021;100(6):1303–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma L, Divers J, Freedman BI. Mechanisms of injury in APOL1-associated kidney disease. Transplantation. 2019;103(3):487–492. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000002509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paranjpe I, Chaudhary K, Paranjpe M, et al. Association of APOL1 risk genotype and air pollution for kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(3):401–403. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11921019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha A, Kumar V, Haque S, et al. Alterations in plasma membrane ion channel structures stimulate NLRP3 inflammasomes activation in APOL1 risk milieu. FEBS J. 2020;287:2000–2022. doi: 10.1111/febs.15133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(11):2129–2137. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichols B, Jog P, Lee JH, et al. Innate immunity pathways regulate the nephropathy gene Apolipoprotein L1. Kidney Int. 2015;87(2):332–342. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu J, Raman A, Coffey NJ, et al. The key role of NLRP3 and STING in APOL1-associated podocytopathy. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(20):e136329. doi: 10.1172/jci136329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cameron-Christie S, Wolock CJ, Groopman E, et al. Exome-based rare-variant analyses in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(6):1109–1122. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018090909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langefeld CD, Comeau ME, Ng MC, et al. Genome-wide association studies suggest that APOL1-environment interactions more likely trigger kidney disease in African Americans with non-diabetic nephropathy than strong APOL1-second gene interactions. Kidney Int. 2018;94(3):599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groopman EE, Marasa M, Cameron-Christie S, et al. Diagnostic utility of exome sequencing for kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(2):142–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren Z, Povysil G, Hostyk JA, Cui H, Bhardwaj N, Goldstein DB. ATAV: a comprehensive platform for population-scale genomic analyses. BMC Bioinformatics. 2021;22(1):149. doi: 10.1186/s12859-021-04071-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abraham G, Inouye M. Fast principal component analysis of large-scale genome-wide data. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e93766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blondel VD, Guillaume J-L, Lambiotte R, Lefebvre E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J Stat Mech. 2008;2008(10):P10008. doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/p10008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; 2020. Available at http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berkowitz SA, Traore CY, Singer DE, Atlas SJ. Evaluating area-based socioeconomic status indicators for monitoring disparities within health care systems: results from a primary care network. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(2):398–417. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma N, Schwendimann R, Endrich O, Ausserhofer D, Simon M. Comparing Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity indices with different weightings to predict in-hospital mortality: an analysis of national inpatient data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05999-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravani P, Fiocco M, Liu P, et al. Influence of mortality on estimating the risk of kidney failure in people with stage 4 CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(11):2219–2227. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019060640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, et al. New creatinine- and cystatin C–based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1737–1749. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2102953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azzi A, Cachat F, Faouzi M, et al. Is there an age cutoff to apply adult formulas for GFR estimation in children? J Nephrol. 2015;28(1):59–66. doi: 10.1007/s40620-014-0148-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shou H, Hsu JY, Xie D, et al. Analytic considerations for repeated measures of eGFR in cohort studies of CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(8):1357–1365. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11311116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasouly HM, Groopman EE, Heyman-Kantor R, et al. The burden of Candidate pathogenic variants for kidney and genitourinary disorders emerging from exome sequencing. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(1):11–21. doi: 10.7326/m18-1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Povysil G, Chazara O, Carss KJ, et al. Assessing the role of rare genetic variation in patients with heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(4):379–386. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.6500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mbatchou J, Barnard L, Backman J, et al. Computationally efficient whole-genome regression for quantitative and binary traits. Nat Genet. 2021;53(7):1097–1103. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00870-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang J, Ferreira T, Morris AP, et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat Genet. 2012;44(4):369–375. doi: 10.1038/ng.2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Povysil G, Petrovski S, Hostyk J, Aggarwal V, Allen AS, Goldstein DB. Rare-variant collapsing analyses for complex traits: guidelines and applications. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(12):747–759. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0177-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van der Auwera GA, O'Connor BD. Genomics in the Cloud: Using Docker, GATK, and WDL in Terra. O'Reilly Media; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Storey JD. False discovery rate. In: Lovric M, editor. International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science. Springer; 2011:504–508. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-04898-2_248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palmer ND, Ng MC, Langefeld CD, et al. Lack of association of the APOL1 G3 haplotype in African Americans with ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(5):1021–1025. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jagannathan R, Rajagopalan K, Hogan J, et al. Association between APOL1 genotype and kidney diseases and annual Kidney function change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the prospective studies. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2021;14:97–104. doi: 10.2147/ijnrd.s294191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tzur S, Rosset S, Skorecki K, Wasser WG. APOL1 allelic variants are associated with lower age of dialysis initiation and thereby increased dialysis vintage in African and Hispanic Americans with non-diabetic end-stage kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(4):1498–1505. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee BT, Kumar V, Williams T, et al. The APOL1 genotype of African American kidney transplant recipients does not impact 5-year allograft survival. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(7):1924–1928. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04033.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khan A, Turchin MC, Patki A, et al. Genome-wide polygenic score to predict chronic kidney disease across ancestries. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1412–1420. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01869-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cooper A, Ilboudo H, Alibu VP, et al. APOL1 renal risk variants have contrasting resistance and susceptibility associations with African trypanosomiasis. eLife. 2017;6:e25461. doi: 10.7554/elife.25461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayek SS, Koh KH, Grams ME, et al. A tripartite complex of suPAR, APOL1 risk variants and αvβ3 integrin on podocytes mediates chronic kidney disease. Nat Med. 2017;23(8):945–953. doi: 10.1038/nm.4362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomson R, Genovese G, Canon C, et al. Evolution of the primate trypanolytic factor APOL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(20):E2130–E2139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400699111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hughson MD, Hoy WE, Mott SA, Bertram JF, Winkler CA, Kopp JB. APOL1 risk variants independently associated with early cardiovascular disease death. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(1):89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bajaj A, Ihegword A, Qiu C, et al. Phenome-wide association analysis suggests the APOL1 linked disease spectrum primarily drives kidney-specific pathways. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):1032–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cocchi E, Nestor JG, Gharavi AG. Clinical genetic screening in adult patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(10):1497–1510. doi: 10.2215/CJN.15141219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Masters SL, Gerlic M, Metcalf D, et al. NLRP1 inflammasome activation induces pyroptosis of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Immunity. 2012;37(6):1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Individual level data for 1426 participants with CKD are available through National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) dbGaP database (phs001828.v2.p1, in process).