Keywords: cardiovascular disease, CKD, clinical trial, coronary calcification, randomized controlled trials, vascular calcification, magnesium

Abstract

Significance Statement

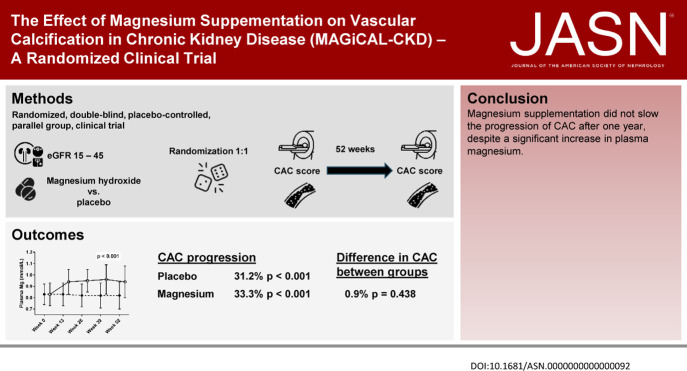

Magnesium prevents vascular calcification in animals with CKD. In addition, lower serum magnesium is associated with higher risk of cardiovascular events in CKD. In a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, the authors investigated the effects of magnesium supplementation versus placebo on vascular calcification in patients with predialysis CKD. Despite significant increases in plasma magnesium among study participants who received magnesium compared with those who received placebo, magnesium supplementation did not slow the progression of vascular calcification in study participants. In addition, the findings showed a higher incidence of serious adverse events in the group treated with magnesium. Magnesium supplementation alone was not sufficient to delay progression of vascular calcification, and other therapeutic strategies might be necessary to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease in CKD.

Background

Elevated levels of serum magnesium are associated with lower risk of cardiovascular events in patients with CKD. Magnesium also prevents vascular calcification in animal models of CKD.

Methods

To investigate whether oral magnesium supplementation would slow the progression of vascular calcification in CKD, we conducted a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, clinical trial. We enrolled 148 subjects with an eGFR between 15 and 45 ml/min and randomly assigned them to receive oral magnesium hydroxide 15 mmol twice daily or matching placebo for 12 months. The primary end point was the between-groups difference in coronary artery calcification (CAC) score after 12 months adjusted for baseline CAC score, age, and diabetes mellitus.

Results

A total of 75 subjects received magnesium and 73 received placebo. Median eGFR was 25 ml/min at baseline, and median baseline CAC scores were 413 and 274 in the magnesium and placebo groups, respectively. Despite plasma magnesium increasing significantly during the trial in the magnesium group, the baseline-adjusted CAC scores did not differ significantly between the two groups after 12 months. Prespecified subgroup analyses according to CAC>0 at baseline, diabetes mellitus, or tertiles of serum calcification propensity did not significantly alter the main results. Among subjects who experienced gastrointestinal adverse effects, 35 were in the group receiving magnesium treatment versus nine in the placebo group. Five deaths and six cardiovascular events occurred in the magnesium group compared with two deaths and no cardiovascular events in the placebo group.

Conclusions

Magnesium supplementation for 12 months did not slow the progression of vascular calcification in CKD, despite a significant increase in plasma magnesium.

Clinical Trials Registration

Introduction

CKD is associated with a very high risk of cardiovascular disease independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.1 Coronary artery calcification (CAC) increases with progressive CKD,2 and CAC is associated with a graded increase in the risk of cardiovascular events in CKD.3 Attempts to prevent progression of CAC might reduce the risk of cardiovascular events. Magnesium prevents vascular calcification in rats with CKD,4 and in patients with end stage kidney disease, serum magnesium has a U-shaped relationship with cardiovascular death, with slight hypermagnesemia being associated with the lowest risk of cardiovascular death.5 In vitro, magnesium delays the transition from initially harmless primary to dangerous secondary calciprotein particles (mineral complexes of fetuin-A, calcium, and phosphate,6 which cause massive vascular calcification7), and thus, magnesium might protect against vascular calcification induced by disturbed mineral metabolism in CKD.8 We hypothesized that magnesium supplementation would delay the progression of CAC in patients with predialysis CKD and investigated this hypothesis in the magnesium supplementation on vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease trial.

Methods and Materials

Study Participants

This was an investigator-initiated double-blinded placebo-controlled multicenter clinical trial conducted at nine sites in Denmark and Norway. The full study design and rationale has previously been published9 including the revised statistical plan (https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/6/e016795.responses) (revised before unblinding of the data). Briefly, we recruited adult patients with an eGFR of 15–45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula) with plasma magnesium <0.82 mmol/L and plasma phosphate >1.15 mmol/L or plasma magnesium <0.92 mmol/L and plasma phosphate >1.30 mmol/L. We excluded kidney transplant recipients, patients who had undergone a parathyroidectomy or had plasma intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) >66 pmol/L, patients who had undergone coronary artery bypass grafting, and patients who were taking magnesium supplements or had conditions which impaired gastrointestinal absorption of magnesium.

All subjects gave written informed consent before initiating the trial, and the trial was performed according to the latest revision of the Helsinki Declaration. The trial was approved by the Danish and Norwegian National Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics (H-15009846 and Regionale komiteer for medisinsk og helsefaglig forskningsetikk Sør-Øst D 2015/2428, respectively) as well as the Danish and Norwegian Data Protection Agencies (2012-58-0004 and 16–077, respectively) and was prospectively registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02542319) before initiation.

Interventions

Subjects were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to 52 weeks of treatment with either oral slow-release Mg hydroxide (Mablet 360 mg, Gunnar Kjems ApS, Denmark) twice daily (equivalent to 30 mmol of elemental magnesium per day) or matching placebo twice daily. Tablets containing magnesium hydroxide and placebo were identical in appearance, odor, constituents, and containers and did not contain calcium. Treatment allocation followed a computer-generated randomization list with permuted randomization in blocks of four and stratification according to enrollment site and presence of diabetes mellitus (yes/no). Subjects and investigators were blinded to treatment allocation for the duration of the trial.

At weeks 0 and 52, subjects underwent multislice electrocardiogram-gated computer tomography scans of the heart without intravenous contrast to calculate the CAC score by the Agatston method.10 All sites used 128 slice scanners according to a common scanning protocol. Subjects were administered beta-blockers 3 days before the scans if the heart rate was >60 beats/min. CAC scores were calculated independently by two observers trained in CAC scoring, and in the event of >5% difference in the calculated CAC score, the score was recalculated by both observers for the final CAC score (average of the two rescored CAC score). In addition, every 13 weeks, subjects had blood samples drawn in a fasting state and performed 24-hour urine collections. Study medication was dispensed every 13 weeks, and adherence to study medication was assessed by pill count.

Primary End point and Statistics

The primary end point was the week 52 CAC, which was compared between treatment groups by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) of log-transformed CAC at week 52, with adjustment for prevalent diabetes (yes/no) and linear adjustments for age and baseline (week 0) log-transformed CAC score. We tested for heterogeneity of the treatment effect for subjects with CAC scores >0 and =0 at week 0, prevalent diabetes mellitus (yes/no), and tertiles of serum calcification propensity (T50).11 Basic random intercept linear mixed models with a compound symmetry covariance structure were used to analyze changes over time in the serial measurements of plasma magnesium, plasma phosphate, plasma ionized calcium, plasma intact PTH, plasma potassium, eGFR, urine magnesium, and urine phosphate. Within-group mean baseline to week 52 changes in log-transformed CAC scores were tested for statistical significance using paired t-tests and back-transformed with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to point and interval estimates of median percentage changes in CAC scores.

Data are described as mean±SD, median with interquartile range, or numbers and percentages, as appropriate. Values for CAC score, plasma ionized calcium, plasma intact PTH, plasma potassium, eGFR, urine magnesium, and urine phosphate were all highly skewed and were log-transformed before performing statistical analyses. For CAC, the analysis was confined to complete cases. Subjects with CAC values of 0 were changed to 1 before log transformation. For the other biochemical variables, missing data were omitted from the analysis and not carried forward from the last observation.

Hypothesis testing of treatment effects was performed on the basis of statistical significance of treatment by time interaction coefficients. Mixed models were estimated by maximum likelihood, and CIs and tests used the model-based covariance estimate.

The data analysis was performed blinded to treatment allocation. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample Size Calculation

We considered an annual difference in CAC score of 200 to be the minimally relevant difference. With a power (β) of 80% in a two-sample t-test with a significance (α) of 5%, the sample size was calculated to be 52 per group for subjects who had prevalent CAC at week 0. However, because we did not know which subjects would have prevalent CAC at week 0, we assumed that the prevalence (51%) and progression of CAC in our study population would be similar to a reference study.12 On the basis of this, we therefore needed 108 subjects per group. We anticipated a dropout rate of 15% and therefore planned to recruit 250 subjects in the trial.

Results

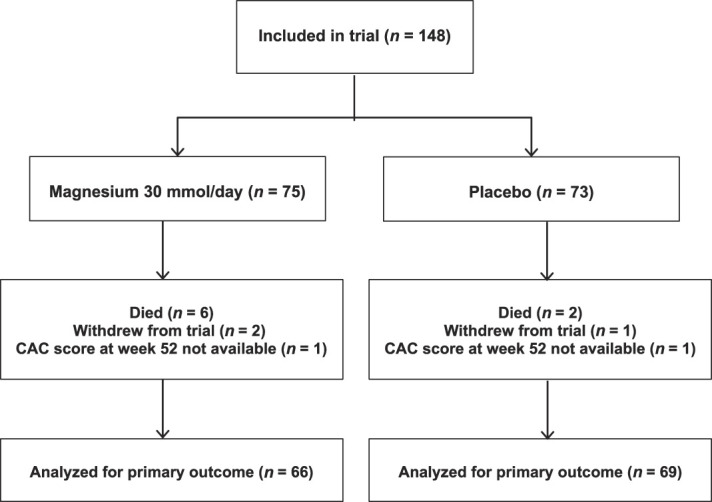

Between December 2015 and October 2019, we enrolled 148 of the 250 planed study participants after which enrollment was stopped because of slow recruitment. Of these, 135 completed the trial with CAC scores at week 52 available for 66 subjects in the magnesium group and 69 subjects in the placebo group (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics for the study participants were similar, although CAC scores were higher among subjects randomized to magnesium treatment (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram for trial.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics

| Characteristic | Magnesium (n=75) | Placebo (n=73) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 66±11 | 65±14 |

| Male sex (%) | 47 (61) | 43 (59) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1±4.7 | 29.2±5.6 |

| Cause of CKD (%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (24) | 19 (26) |

| Hypertension | 15 (20) | 16 (22) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 13 (17) | 11 (15) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 4 (5) | 5 (7) |

| Interstitial nephritis | 2 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Other | 9 (12) | 13 (18) |

| Unknown | 13 (17) | 9 (12) |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 70 (93) | 69 (95) |

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 | 3 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 26 (35) | 29 (40) |

| Coronary artery disease | 12 (16) | 16 (22) |

| Heart failure | 4 (5) | 4 (6) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 10 (13) | 7 (10) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 6 (8) | 3 (4) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 63 (84) | 63 (86) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7 (9) | 4 (6) |

| Smoking (%) | ||

| Never smoker | 27 (36) | 27 (37) |

| Previous smoker | 34 (45) | 30 (41) |

| Current smoker | 14 (19) | 16 (22) |

| Pack-years | 10 (0–30) | 9.5 (0–25) |

| Medication (%) | ||

| ACEi or ARB | 54 (73) | 50 (69) |

| Loop diuretic | 36 (49) | 34 (47) |

| Thiazide diuretic | 11 (15) | 17 (23) |

| Statin | 43 (58) | 44 (60) |

| Antiplatelet | 25 (34) | 29 (40) |

| DOAC | 3 (4) | 3 (4) |

| Warfarin | 3 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Insulin | 17 (23) | 19 (26) |

| GLP-1 RA | 1 (1) | 2 (3) |

| SGLT2i | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Activate vitamin D analogs | 21 (28) | 16 (22) |

| Native vitamin D analogs | 38 (51) | 30 (41) |

| Ca-containing PO4 binders | 4 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Non-Ca-containing PO4 binders | 4 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Erythropoietin-stimulating agents | 4 (5) | 4 (6) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 139 (131–157) | 140 (128–151) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 80 (72–86) | 79 (71–85) |

| Plasma total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.6 (3.6–5.6) | 4.6 (3.7–5.5) |

| Plasma LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.5 (1.6–3.5) | 2.4 (1.8–3.1) |

| Blood hemoglobin A1c | ||

| Subjects with diabetes mellitus (mmol/mol) | 53 (43–76) | 61 (53–64) |

| Subjects without diabetes mellitus (mmol/mol) | 38 (34–40) | 37 (34–41) |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) | 25 (21–33) | 25 (20–33) |

| 24-h urine protein excretion (g) | 0.6 (0.2–1.6) | 0.7 (0.2–1.8) |

| Plasma Mg (mmol/L) | 0.83±0.10 | 0.83±0.09 |

| Plasma PO4 (mmol/L) | 1.28±0.20 | 1.25±0.18 |

| Plasma ionized Ca (mmol/L) | 1.21 (1.18–1.25) | 1.21 (1.19–1.23) |

| Plasma intact PTH (pmol/L) | 10.6 (6.6–21.3) | 12 (8.0–19.0) |

| Plasma bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 23.6±2.8 | 24.1±3.1 |

| Serum calcification propensity (min) | 254±81 | 251±74 |

| CAC score | 413 (19–1585) | 274 (29–1007) |

| CAC score >0 (%) | 64 (85) | 63 (86) |

Mean±SD or median and interquartile range. BMI, body mass index; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-2 receptor blocker; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor antagonist; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor; Ca, calcium; PO4, phosphate; Mg, magnesium; PTH, parathyroid hormone; CAC, coronary artery calcification.

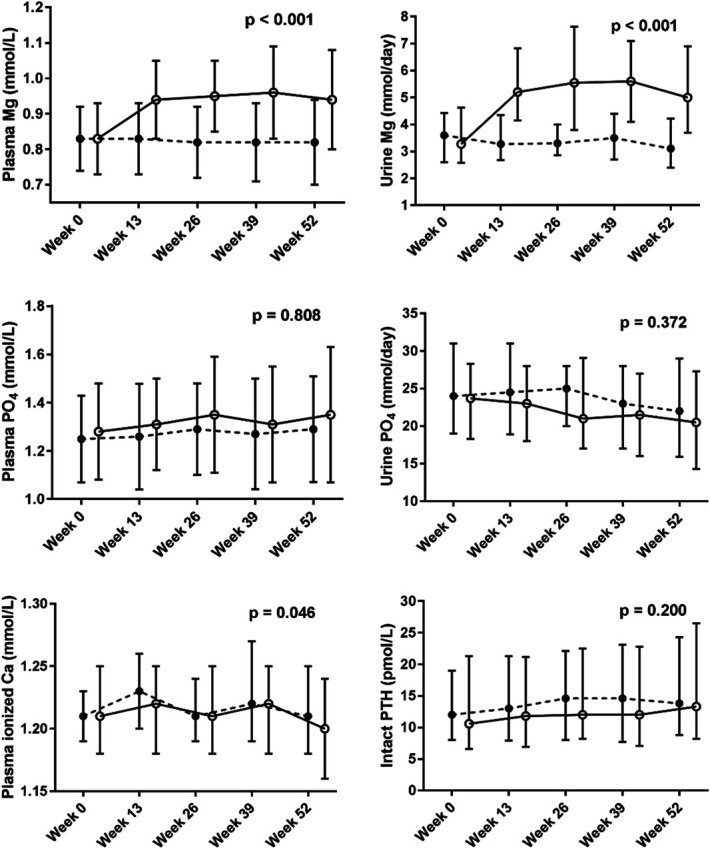

Adherence to study drug was high with 97% of subjects taking >95% of the study drug as assessed by tablet count at each study visit. Both plasma magnesium and 24-hour urine magnesium excretion increased significantly in the magnesium-treated group (P<0.001) and were unchanged in the placebo group (Figure 2). At week 52, mean plasma magnesium was 0.94±0.14 mmol/L in the magnesium-treated group versus 0.82±0.12 mmol/L in the placebo group, with a between-groups difference at week 52 of 0.13 mmol/L (95% CI, 0.08 to 0.17 mmol/L, P<0.001). No subjects had measured plasma magnesium >1.50 mmol/L at any time during the trial.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal effects of magnesium on markers of mineral metabolism. Analysis of changes over time in the serial measurements of markers of mineral metabolism using linear mixed models with basic random intercept and compound symmetry covariance structure. Plots describe the original data with error bars representing mean and SD for plasma Mg and PO4, and median and interquartile range for urine Mg and PO4, plasma ionized Ca, and intact PTH. ●=placebo (n=73), ○=magnesium (n=75). Ca, calcium; Mg, magnesium; PO4, phosphate.

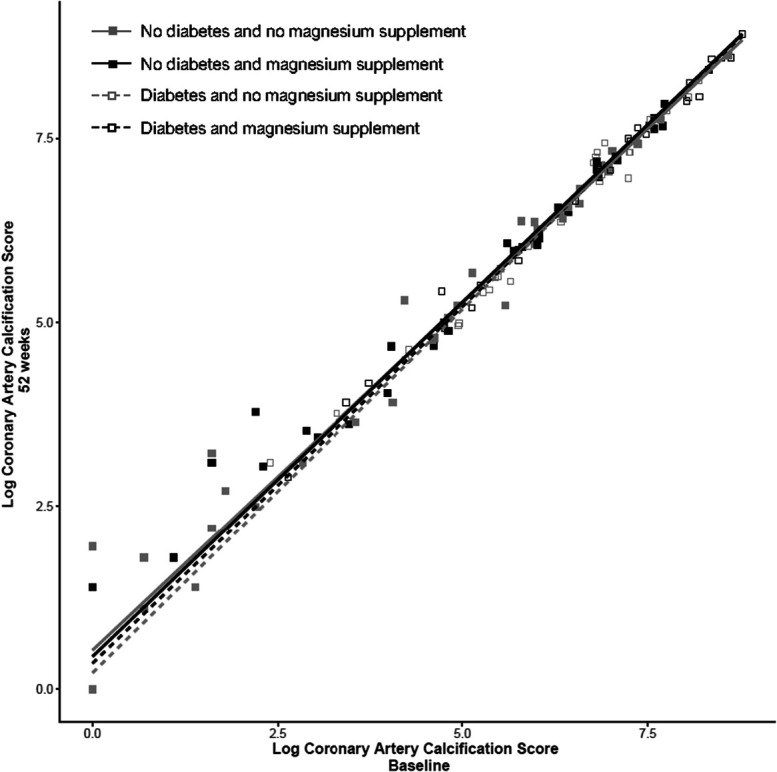

Consistency of the data with standard ANCOVA assumptions was acceptable after logarithmic transformation of the CAC score. The CAC score increased by 31.2% (95% CI, 18.5% to 45.2%, P<0.001) in the placebo group and 33.3% (95% CI, 19.9% to 48.2%, P<0.001) in the magnesium group during the trial (Table 2). However, the between-groups difference in CAC score at week 52 adjusted for baseline CAC score, age, and diabetes mellitus was only 0.9% (95% CI, –10.2% to 13.4%, P=0.438) (Table 2 and Figure 3). We did not observe statistically significant heterogeneity of treatment effect for the prespecified subgroups of baseline CAC score =0 or >0, diabetes mellitus at baseline, and tertiles of T50 at baseline (Supplemental Figure 1). Additional representations of the ANCOVA are shown in Supplementary Figures 3 and 4.

Table 2.

Coronary artery calcification scores before and after treatment

| Characteristic | CAC Score Week 0 (n=66) (Median and Interquartile Range) |

CAC Score Week 52 (n=69) (Median and Interquartile Range) |

Estimated Median Percentage CAC Score Changes Assuming Log-Normal Within-Group Distributions (paired t-tests) |

Between Groups Difference in Fractional CAC Changes at Week 52 (From ANCOVA Model for Log-Transformed CAC Scores) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo group | 247 (21–955) | 274 (30–1182) | 31.2% (95% CI, 18.5% to 45.2%, P<0.001) | |

| Magnesium group | 370 (27–1462) | 429 (41–1825) | 33.3% (95% CI, 19.9% to 48.2%, P<0.001) | |

| 0.9% (95% CI, –10.2% to 13.4%, P=0.438) |

Median and interquartile range for subjects with coronary artery calcification scores at week 0 and week 52. Analysis of covariance model adjusted for coronary artery calcification score, age, and prevalent diabetes mellitus at week 0. CAC, coronary artery calcification; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 3.

CAC scores before and after treatment. ANCOVA with CAC score at week 0 as covariate. Scatterplot of logarithmic CAC score at 52 weeks and baseline in all subjects with stratification for diabetes mellitus and treatment (magnesium supplementation or placebo).

Magnesium supplementation did not affect plasma phosphate, intact PTH, or 24-hour urine excretion of phosphate (Figure 2), and nor were eGFR and plasma potassium affected by the intervention (Supplemental Figure 2). Ionized calcium showed a marginally statistically significant between-groups difference (treatment×time interaction P=0.046). In the magnesium group, T50 was 254±81 minutes at week 0 and 255±66 minutes at week 52 versus 251±74 minutes and 259±78 minutes in the placebo group (mean difference in change between treatments 9 minutes, 95% CI, –30 to 12 minutes, P=0.412).

Thirty-five subjects (47%) randomized to magnesium supplementation experienced loose stool (32%) or diarrhea (15%) compared with only nine subjects (12%) randomized to placebo (loose stool 7% and diarrhea 6%). The median time until loose stool or diarrhea was 2 weeks (interquartile range 1–8 weeks) in the magnesium group versus 7 weeks (interquartile range 4–8 weeks) in the placebo group. In the magnesium group, eight subjects (11%) reduced the dose of the study drug and three subjects (4%) discontinued the study drug because of gastrointestinal side effects while in the placebo group, one subject (1%) reduced the dose of the study drug and three subjects (4%) discontinued the study drug because of gastrointestinal side effects.

There were 23 serious adverse events in the magnesium group and 13 in the placebo group. In the magnesium group, we observed six major adverse cardiovascular events, namely three sudden cardiac deaths, two strokes, and one subject with incident heart failure. There were no major adverse cardiovascular events in the placebo group. We observed one subject with incident cancer in the magnesium group and three subjects with incident cancer in the placebo group, with one death due to cancer in each group. In total, there were six deaths in the magnesium group and two deaths in the placebo group. We also observed six gout attacks in the magnesium group compared with one in the placebo group. None of the serious adverse events were suspected to be caused by the study drug as assessed by the site investigators at the time of the events. Details of the serious adverse events are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Discussion

The main finding of the MAGiCAL-CKD trial is that magnesium supplementation did not slow progression of the CAC score in CKD compared with placebo among subjects in our trial. This was despite the fact that magnesium treatment resulted in a significant increase in plasma magnesium and that adherence to study medication was very high.

Our findings are in contrast to those of Sakaguchi et al.13 who found that magnesium supplementation slowed the progression of CAC in subjects with CKD and risk factors of cardiovascular disease. The two trials are similar in that they both used oral magnesium supplementation in a randomized controlled design with a similar sample size and duration of intervention. However, they also differ on several points. First, our trial used a double-blinded study design and a fixed dose of magnesium while the trial by Sakaguchi et al. used an open-label design and titration of magnesium supplementation to a serum magnesium level of 1.04–1.25 mmol/L (achieved serum magnesium was 0.88±0.13 mmol/L, which was slightly lower than the 0.94±0.14 mmol/L in our trial). The open-label design may have introduced inadvertent treatment bias by treating physicians, a bias which can be excluded in our trial by virtue of the double-blinded study design. Second, while both trials enrolled subjects with CKD, the trial by Sakaguchi et al. enrolled subjects on the basis of high cardiovascular risk using traditional cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes mellitus, history of cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, or current smoking) while enrollment of subjects in our trial was on the basis of levels of plasma phosphate and magnesium (which have previously been associated with progression of CAC in CKD). Despite this, both trial populations were similar at baseline. However, it cannot be ruled out that differences in the trial populations that are not reflected in the baseline characteristics may have influenced the treatment effect. Third, the two trials used different formulations of oral magnesium supplementation, and while both trials showed similar and statistically significant increases in serum/plasma levels of magnesium, it cannot be ruled out that different formulations of oral magnesium supplementation have different effects on progression of CAC in CKD. Given that there were clear differences in the progression of the CAC score between the two groups in the trial by Sakaguchi et al. and almost none in our trial, it seems unlikely that the methods used to assess CAC progression is the explanation for the differences between the two trials.

We observed a higher incidence of cardiovascular events and deaths in the magnesium group compared with the placebo groups. Although the cardiovascular events were divided among strokes, congestive heart failure, and sudden cardiac death, worsening of atherosclerotic disease could conceivably be a common underlying cause of these events. This is not in line with the presumed effects of magnesium treatment on the vasculature in CKD, which is believed to be through reduced platelet aggregation and increased production of nitric oxide,14 as well as delayed formation of calciprotein particles, inflammation, and oxidative stress.15 Subjects who experienced a cardiovascular event had very high CAC scores at baseline and would therefore be assumed to be at high risk of cardiovascular events. It is interesting to note that we did not observe any events traditionally ascribed to toxic hypermagnesemia (e.g., arrythmias, hypotension, or syncope), which are seen at plasma levels of magnesium >2.0 mmol/L.16 We also observed a higher incidence of gout attacks in subjects randomized to magnesium treatment, an association that to the best of our knowledge has not previously been described and for which we have no explanation.

It is possible that the higher incidence of serious adverse events associated with magnesium treatment occurred purely by chance. Because the trial was not powered to investigate these end points, the results can only be taken as hypothesis-generating. However, we cannot rule out that the observed cardiovascular events were related to the magnesium treatment and close monitoring of adverse events in future trials of magnesium supplementation in CKD will be necessary.

Our trial has limitations. Owing to slow recruitment, we were unable to enroll the planned 250 subjects into the trial and the trial may therefore have been underpowered to detect any differences in the CAC score between the two groups. However, our sample size assumed that half of all enrolled subjects would have CAC score >0 at baseline, when in fact 85% of our trial population had CAC score >0. The narrow CIs around the effect estimate exclude a treatment effect of >15%, a cutoff which has previously been shown to be predictive of future cardiovascular events.17 Thus, even if there is a small effect of the magnesium supplementation, which might have been uncovered with a larger trial population, it is unlikely to be clinically meaningful. Baseline imbalances in CAC scores were compensated for by linear adjustment in the ANCOVA model, thus not affecting the final results. It is, however, possible that calcification may have been delayed in other sites, for example, heart valves, thoracic aorta, or abdominal aorta, which were not measured in the trial. Our inclusion criteria may explain the lack of a treatment effect. Enrichment of the trial population for subjects with CAC score >0 as part of the inclusion criteria would have reduced the necessary sample size, but would instead have required larger resources from the investigating sites and was considered unfeasible. In addition, the use of different risk factors to identify and enroll subjects at risk of progressive CAC (e.g., traditional cardiovascular risk factors, prevalent CAC at baseline, low T50, etc.) and/or longer trial duration might have produced different results. It is also possible that a higher dose of oral magnesium may have raised plasma magnesium further, which might have affected our results. However, given the high number of gastrointestinal side effects from magnesium supplementation, it seems unlikely that a higher dose of oral magnesium would be tolerated for a prolonged period. As an alternative to the enteral route of magnesium supplementation, we have previously conducted clinical research using increased levels of magnesium in dialysate fluid in patients on hemodialysis, which was not associated with gastrointestinal side effects.18 Finally, subjects who died during the trial all had CAC >0, and it is possible that “survivors bias” may have affected the results (i.e., subjects who died may have had progressive CAC amendable to treatment, which was not captured because they did not have repeat measurement of the CAC score at the end of the trial).

The main strength of the trial is the randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded trial design, which is the highest standard for conduct of clinical trials. In addition, despite no between-groups differences in CAC scores after 1 year, the trial population was clearly at high risk of progressive CAC with both groups progressing >30% from baseline during the course of the trial and was therefore a relevant trial population with high risk of cardiovascular events, that is progression >15% per year.17 This article does not contain all planned secondary end points relating the effects of magnesium supplementation.

In conclusion, magnesium supplementation did not slow the progression of CAC after one year among participants in our trial, despite a significant increase in plasma magnesium.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the huge contributions of Ørjan Ingebrigtsen to the study protocol; Charlotte Bjernved Nielsen and Tine Vester Christensen to the implementation of good clinical practice; as well as the support to conducting the trial from Lise Tarnow, Lotte Pietraszek, Susanne Månsson, Lizette Helbo Nislev, Mette Lund, Marian Holm, Lene Thomsen, Lillian Sørensen, Toril Pompino Enger, Trude Bjørntvedt, Lisa Frödin, Charlotte Mose Skov, Kirsten Munk Vesterager, and Kirsten Meinicke Stilling.

Disclosures

R. Borg reports Consultancy: AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim; Research Funding: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and NovoNordic Foundation; Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim; and Advisory or Leadership Role: AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim. L. Brandi reports Honoraria: Astellas. I. Bressendorff reports Research Funding: Novo Nordisk Foundation. N. Carlson reports Speakers Bureau: AstraZeneca—Lecture fees and Bristol Myers Squibb—Lecture fees. D. Hansen reports Research Funding: AstraZeneca A/S, Bayer A/S, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gedeon Richter, Kappa Bioscience AS, and Vifor Pharma; Advisory or Leadership Role: Pharmacosmos; and Speakers Bureau: AstraZeneca A/S and UCB Nordic. C.H. Kristiansen reports Employers: Akershus University Hospital, Oslo Metropolitan University, and Philips Healthcare. A. Pasch is a founder, stockholder, and employee of Calciscon AG, Bern, Switzerland, which commercializes the T50 test. A. Pasch also reports the following: Employer: Biel, Switzerland; Ownership Interest: Biel, Switzerland; and Patents or Royalties: Calciscon AG, Biel, Switzerland. M. Schou reports Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk; and Speakers Bureau: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by Nordsjælland's Hospital's Research Foundation, The Danish Society of Nephrology's Research Foundation, Helen and Ejnar Bjørnow's Foundation, The Danish Kidney Foundation, and The Toyota Foundation. Gunnar Kjems ApS provided the study drug and placebo for free but had no role in study design or interpretation of results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L. Brandi, I. Bressendorff, D. Hansen, M. Schou

Data curation: I. Bressendorff, H.Ø. Hjortkjær, C. Kragelund, C.H. Kristiansen, A. Pasch

Formal analysis: I. Bressendorff, N. Carlson

Investigation: K. Borg, R. Borg, I. Bressendorff, D. Hansen, B. Hashemi, T. Kristensen, M. Svensson, B. Tougaard, M.H. Vrist

Project administration: L. Brandi I. Bressendorff

Resources: H. Ashraf, L. Brandi, M. Nasiri

Supervision: L. Brandi

Writing – original draft: I. Bressendorff

Writing – review & editing: H. Ashraf, K. Borg, R. Borg, L. Brandi, I. Bressendorff, N. Carlson, D. Hansen, B. Hashemi, H.Ø. Hjortkjær, C. Kragelund, C.H. Kristiansen, T. Kristensen, M. Nasiri, A. Pasch, M. Schou, M. Svensson, B. Tougaard, M.H. Vrist

Data Sharing Statement

There are some restrictions for these data as follows: The Danish Authorities have not granted permission for the patient-level data to be shared openly (approval given in 2015 before Data Sharing was common). Researchers interested in using patient-level data may contact the corresponding author to enquire about the possibility of using the patient-level data.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/JSN/D745.

Supplemental Figure 1. Effect of magnesium supplementation on CAC score in subgroups.

Supplemental Figure 2. Longitudinal effects of magnesium on kidney function and potassium.

Supplemental Figure 3. Log coronary artery calcification score at 52 weeks and baseline in age-grouped subjects with stratification on diabetes and treatment.

Supplemental Figure 4. Effect plots stratified on treatment with magnesium supplement and placebo.

Supplemental Table 1. Serious adverse Events.

References

- 1.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budoff MJ, Rader DJ, Reilly MP, et al. Relationship of estimated GFR and coronary artery calcification in the CRIC (chronic renal insufficiency cohort) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(4):519–526. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Budoff MJ, Reilly MP, et al. Coronary artery calcification and risk of cardiovascular disease and death among patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(6):635–643. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz-Tocados JM, Peralta-Ramirez A, Rodriguez-Ortiz ME, et al. Dietary magnesium supplementation prevents and reverses vascular and soft tissue calcifications in uremic rats. Kidney Int. 2017;92(5):1084–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakaguchi Y, Fujii N, Shoji T, Hayashi T, Rakugi H, Isaka Y. Hypomagnesemia is a significant predictor of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2014;85(1):174–181. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ter Braake AD, Eelderink C, Zeper LW, et al. Calciprotein particle inhibition explains magnesium-mediated protection against vascular calcification. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(5):765–773. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfz190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aghagolzadeh P, Bachtler M, Bijarnia R, et al. Calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells is induced by secondary calciprotein particles and enhanced by tumor necrosis factor-α. Atherosclerosis. 2016;251:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ter Braake AD, Vervloet MG, de Baaij JHF, Hoenderop JGJ. Magnesium to prevent kidney disease–associated vascular calcification: crystal clear? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;37(3):421–429. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bressendorff I, Hansen D, Schou M, Kragelund C, Brandi L. The effect of magnesium supplementation on vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease - a randomised clinical trial (MAGiCAL-CKD): essential study design and rationale. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e016795. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(4):827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasch A, Farese S, Graber S, et al. Nanoparticle-based test measures overall propensity for calcification in serum. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(10):1744–1752. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russo D, Corrao S, Miranda I, et al. Progression of coronary artery calcification in predialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27(2):152–158. doi: 10.1159/000100044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakaguchi Y, Hamano T, Obi Y, et al. A randomized trial of magnesium oxide and oral carbon adsorbent for coronary artery calcification in predialysis CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(6):1073–1085. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018111150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiger H, Wanner C. Magnesium in disease. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5(suppl 1):i25–i38. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakaguchi Y. The emerging role of magnesium in CKD. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2022;26(5):379–384. doi: 10.1007/s10157-022-02182-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jahnen-Dechent W, Ketteler M. Magnesium basics. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5(suppl 1):i3–i14. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raggi P, Callister TQ, Shaw LJ. Progression of coronary artery calcium and risk of first myocardial infarction in patients receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(7):1272–1277. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000127024.40516.ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bressendorff I, Hansen D, Schou M, Pasch A, Brandi L. The effect of increasing dialysate magnesium on serum calcification propensity in subjects with end stage kidney disease: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(9):1373–1380. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13921217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are some restrictions for these data as follows: The Danish Authorities have not granted permission for the patient-level data to be shared openly (approval given in 2015 before Data Sharing was common). Researchers interested in using patient-level data may contact the corresponding author to enquire about the possibility of using the patient-level data.