Abstract

An integrated intersectoral care model promises to meet complex needs to promote early child development and address health determinants and inequities. Nevertheless, there is a lack of understanding of actors’ interactions in producing intersectoral collaboration networks. The present study aimed to analyze the intersectoral collaboration in the social protection network involved in promoting early child growth and development in Brazilian municipalities. Underpinned by the tenets of actor-network theory, a case study was conducted with data produced from an educational intervention, entitled “Projeto Nascente.” Through document analysis (ecomaps), participant observation (in Projeto Nascente seminars), and interviews (with municipal management representatives), our study explored and captured links among actors; controversies and resolution mechanisms; the presence of mediators and intermediaries; and an alignment of actors, resources, and support. The qualitative analysis of these materials identified three main themes: (1) agency fragility for intersectoral collaboration, (2) attempt to form networks, and (3) incorporation of fields of possibilities. Our findings revealed that intersectoral collaboration for promoting child growth and development is virtually non-existent or fragile, and local potential is missed or underused. These results emphasized the scarcity of action by mediators and intermediaries to promote enrollment processes to intersectoral collaboration. Likewise, existing controversies were not used as a mechanism for triggering changes. Our research supports the need to mobilize actors, resources, management, and communication tools that promote processes of interessement and enrollment in favor of intersectoral collaboration policies and practices for child development.

Keywords: intersectoral collaboration, actor-network theory, early child growth and development, health promotion

Introduction

Child development refers to the gradual emergence of progressively more complex thinking patterns, perception, movement, speech, understanding, and relationships. It is also related to developing the ability to control and regulate emotions, focus attention, and plan behaviors. It is now understood that children’s relationships with their caregivers and the environment are important for their growth and development. The quality of relationships, which influences development, must be supported by communities and governments (Engle & Huffman, 2010; WHO, 2007). Early integrated care involving health, education, and social service through intersectoral interventions may provide access to strong environments for a child’s ideal development. These integrated approaches may ensure higher access to child development promotion services, such as parental and caregiver support, nutrition, social protection, primary health, and basic education. These services must be coordinated and aligned locally to accomplish this goal and place the child at the center of actions (Blair & Hall, 2006; Engle et al., 2011; Laurin et al., 2015; WHO, 2007). Brazilian regulations have recommended early intersectoral actions to promote child development, stimulating interaction and effective communication mechanisms among different services at the municipal level (Department of Health, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018).

Social support systems geared toward the complex processes of empowering families and their children can also decrease social inequalities. Families do not operate alone. They are—or should be—inserted into the social network of institutions, institutional agents (educators, social workers, health and other professionals), and organizations serving families within the communities (Stanton-Salazar, 2011). Studying these network relationships, mainly in intersectoral collaborations, must highlight the efforts and mechanisms to address the complexities of stimulating early childhood development. Intersectoral collaborations may occur across various levels of government and between governmental and non-governmental sectors and do not necessarily rely on formal structures. They can also be health specific or focused on other issues. Various intersectoral initiatives addressing health determinants can link public policies and better population outcomes (Freiler et al., 2013). The present study draws on the understanding of intersectoral collaboration of health defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), as described by Nutbeam and Muscat (2021, p. 1592):

Intersectoral action for health refers to actions undertaken by different sectors of society to achieve health outcomes in a way which is more effective, efficient, or sustainable than might be achieved by [one] sector working alone.

The literature has evidence and reflections on aspects contributing to successful intersectoral collaboration. Relationships and relationship building may be central to collaborative governance in all intersectoral collaborations. Relationships among people and organizations are expressions of power (im)balances, which is a fundamental factor that requires continued research to provide a better understanding of how to achieve shared goals (Glandon et al., 2019; Such et al., 2022). A deeper understanding of the diversity of arrangements for the various public services involved in intersectoral actions and the different levels of involvement and integration among the services, policymakers, and practitioners is required (Blanken et al., 2022; Neves et al., 2021; Okeyo et al., 2020). The mapping of the intersectoral networks within various contexts can contribute to understanding the relationships and ways this network works, identifying patterns of interaction (both formal and informal) to refine the knowledge of types of intersectoral arrangements.

This study analyzed the intersectoral collaboration found in the social protection network involved in early child growth and development promotion in Brazilian municipalities. The purpose was to capture the relational view of the existing social network, the complexity of the relationship patterns, and the quality of the support of this network. The issues were examined using the principles of actor-network theory (ANT), a social theory developed in the 1980s as a new approach to science and technology studies (Latour, 2005). We argue that an in-depth understanding of interactions within the network can guide interventions that increase social and technical support for families and professionals, which is known to contribute to reducing social inequities. In addition, the findings may highlight the strengths and weaknesses of relationships in the intersectoral network, demonstrating opportunities to strengthen actions to promote child development.

Methods

The present study relied on a theoretical ANT framework (Bilodeau et al., 2019; Bilodeau & Potvin, 2016; Callon, 1986; Latour, 2005) to inform its research design. A case study was conducted as part of a research project entitled “Projeto Nascente” (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais and Brazilian Ministry of Health).

Theoretical Framework

According to ANT, humans and non-humans (specialized knowledge, resources, technologies) are actors with the power to produce innovation. They interact in a socio-technological network through translation (Latour, 2005). Actors change roles, create new ones, establish or strengthen connections within and among existing networks, create new networks, and mobilize new resources. These displacements and transformations, accompanied by negotiations and adjustments, make up translation, a process consisting of four phases that can overlap. Problematization leads actors to develop a common view of the problem or issue. It allows them to define a common interest with other stakeholders. Interessement means the set of actions that actors implement to encourage other actors to join the project, embrace a common objective, and participate in its realization. Enrollment refers to negotiating and accepting new roles in connection with problematization. Mobilization consists of changes in actors’ positions, for or against the intended result. As a process, translation continues, but the equilibrium has been modified (Callon, 1986).

ANT is currently recognized as a tool for evaluating complex situations and analyzing the production of changes, allowing for a relational view of the action. Moreover, it conceives the context defined by actors and their actions and investigates how the effects are produced (Bilodeau & Potvin, 2016). Concerning intersectoral collaboration, local intersectoral networks support transformations that add up, combine, and render environments more salutogenic, even if modest. ANT notions highlight the connection of heterogeneous universes and the agency of human and non-human entities in networks of action, the critical role of controversies in shaping collective action, the role of intermediaries and mediators that convey ideas and stabilize agreement, the importance of enrolling actors in new positions to achieve an alignment of interests, and the need to mobilize a critical mass of connected actors (Bilodeau et al., 2019). The concept of controversy is fundamental to ANT. It means the confrontation of differing views that actors may hold and are tied to interessement and enrollment in a given situation. ANT essentially considers controversies as places of negotiation (Bilodeau & Potvin, 2016; Callon, 2006).

Four main aspects of ANT principles were considered to contextually analyze the intersectoral collaboration patterns in promoting early child development: links among actors; controversies and resolution mechanisms; the presence and role of mediators and intermediaries; and the alignment of actors, resources, and support. This data coding system was developed from the ANT-based intersectoral collaboration modeling performed by Bilodeau et al. (2019).

Contextualization of the Case Study: Projeto Nascente

This case study was performed in the second half of 2019 as part of Projeto Nascente to reveal the context (organizational political) of intervention in progress concerning intersectoral collaboration.

The Projeto Nascente was intervention research with a convenience sample of one or more primary healthcare unit territories from 31 municipalities in Minas Gerais, Brazil, conducted from August 2019 to December 2019. The research as a whole included the assessment of the external context (social, demographic, socioeconomic, education, health, and environmental indicators), the organizational political context (management and planning of existing intersectoral collaboration in the municipality), the internal context (professionals profiles, expectations and motivations, and situation of child development in each territory), and the effects of the intervention (reorientation of practices to promote the child development and use of the Child Health Booklet). This study contributes to evaluating the organizational political context in some territories.

The territory is the smallest geographic unit created by the healthcare system and matches the delimited area under the care of a team of Family Health Strategy (FHS). In addition, there are other local public services in these territories, such as social service centers, elementary schools, children’s daycare centers, and community service centers. These services work for the same population. The FHS was adopted as the main model for organizing primary health care in the Brazilian public health system (SUS, in Portuguese) and aims to provide universal access and comprehensive health care, coordinate and expand coverage to more complex levels of care, and implement intersectoral actions for health promotion and disease prevention (Paim et al., 2011). The health teams from FHS consist of a doctor, a nurse, a nursing technician, and three to five community health agents, and may or may not include oral health professionals.

The intervention consisted of training an “intersectoral team” composed of professionals from the FHS teams and other sectors working in services located in primary healthcare territories to promote early child growth and development. The choice of professionals to participate in training (“trainee”) and respective enrollment was in the charge of the municipalities. The training (intervention) was based on eight in-person seminars and practical activities about different fields carried out in the services.

The intersectoral collaboration was the subject of one seminar. It was the recommended strategy for articulating and integrating actions in the territories (Supplemental Table 1, program of the intervention performed by Projeto Nascente, including distribution of activities, working hours, and topics discussed in seminars). Health professionals from each municipality, hereinafter called “facilitators,” were selected to deliver this training in each municipality and were prepared for two days (July 2019) on the following themes: National Policy for Comprehensive Child Health Care, child development, parenting, intersectoral collaboration, and strategic planning. The facilitators were instructed to encourage interactions and everyone’s participation, allowing a diversity of speeches and experiences. Then, the Projeto Nascente aimed to encourage intersectoral teams to create innovative solutions that contribute to the promotion of child development, breaking with each sector’s traditional isolated and fragmented actions. This model of intersectoral collaboration built locally (bottom-up approach) does not rule out the possibility of a model of intersectoral collaboration at a higher management level, with local sectoral implementation (top-down approach) (Cunill-Grau, 2005, 2014; Sposati, 2006). The Projeto Nascente aimed to bring these workers together in a training process for coordinated action in the territories. The trainees included 1267 professionals representing the following sectors: Health (76.0%), Education (7.2%), Social Work (6.0%), Universities (1.5%), Culture/Sports/Leisure (0.7%), Civil Society Organizations (0.5%), and Child Tutelary Council (0.3%). Of these, 7.8% of the participants did not inform their sector of origin (Cury et al., 2019).

Data Production

Our chosen unit of analysis for this study was municipalities where Projeto Nascente was in progress. Our sample included intersectoral teams and managers of public services in these municipalities. Our focus was to describe and understand intersectoral collaboration as a context of intervention. We used multiple strategies for data collection: document analysis, participant observation, and interviews (Bowen, 2009; Hanna, 2012; Jorgensen, 1989; Kawulich, 2005) aiming for an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon (Denzin & Lincoln, 1998; Flick, 2014). Additionally, we included professionals from intersectoral teams who know and experience intersectoral collaboration in their daily professional practice. Managers of public services from different sectors represent the organizational political context of the intervention related to the organization and management of the intersectoral childcare network. Thus, these managers would present a broader perception of the relationships/intersectoral actions supporting early child development in their territories.

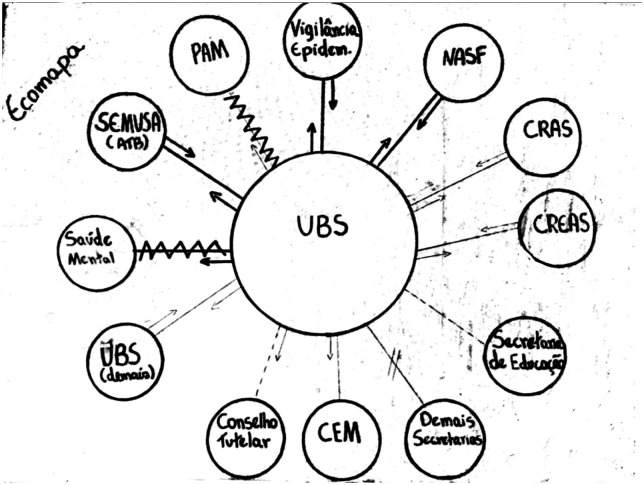

Regarding the intersectoral team, we analyzed documents they produced as a practical activity conducted before the in-person seminar on intersectoral collaboration (October to November 2019). We also observed the participation of these professionals in this same seminar. The analyzed documents were digital or printed copies of ecomaps. Each intersectoral team surveyed all local actors in primary health care, such as social services, schools, daycare centers, and leisure services, representing their relationships through an ecomap. Facilitators had guided the intersectoral team on how to make an ecomap, but they were not present during the production. The intersectoral team was instructed to demonstrate the intersectoral relationships with the family health team placed in a circle in the center of the map. 1 Circles around the central circle represented other identified actors (services). Drawing lines indicated the connections between the family health team and the various actors in the territory. The strength of this relationship was expressed as follows: a thick line represents a strong connection, a thin line represents a weak connection, and a dotted line is a tenuous connection. Arrows along the lines represented the direction of the flow of resources or offered support. Jagged lines denoted stressful or conflicting relationships (Hartman, 1978). Figure 1 illustrates an ecomap produced by professionals from a municipality.

Figure 1.

Ecomap produced by an intersectoral team from a Primary Health Care area during the training of Projeto Nascente. Minas Gerais State, Brazil, 2019.

Ecomaps were the research strategy chosen to explore the nature of social network relationships to support early childhood development in each primary healthcare territory according to professionals’ perceptions from various sectors (Bravington & King, 2019). This tool contributed to diagnosing intersectoral collaboration in the political-organizational context of the intervention. Ecomap enables the organization of data for assessment, planning, and intervention (Hartman, 2003), providing a comprehensive picture of the situation in space and time through three basic elements: relationships, social networks, and support (Bennett & Grant, 2016). This tool offers an interfacial nature, pointing out conflicts to be mediated, bridges to be built, and resources to be sought and mobilized (Hartman, 1978). The ecomaps have been employed to analyze support networks for children, adolescents, and young people, helping to understand relationships in a person’s life and how communication and interaction occur (Johnson et al., 2017; Silveira & Neves, 2019; Woodgate et al., 2020). In addition, when the same pattern of a diagram is used for data production, comparisons between cases can be established (Bravington & King, 2019).

We selected four municipalities, for convenience, to perform participant observation during the in-person seminar on intersectoral collaboration and support networks for child growth and development. In this seminar, each intersectoral team presented their ecomaps to the facilitator and other intersectoral teams, when available in the municipality. Participant observation allowed the researcher (APGC) to capture the expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior, determine who interacts with whom, and grasp how participants communicate with each other (Kawulich, 2005). The aim was to observe the interactions among the professionals on the issues addressed during the seminar. A reflective dialogue between the observer and the facilitators followed each observation, highlighting various aspects of the ongoing interactions. Field notes were also taken and analyzed (Phillippi & Lauderdale, 2018).

The same researcher (APGC) conducted interviews with four municipal health and one social work management representative (hereinafter referred to as “managers”). They were health coordinators, primary care coordinators, and social work policy coordinator. They were also involved in the implementation process of Projeto Nascente: formal adherence to the project, invitation from other sectors to participate, indication and enrollment of professionals, and organization of the infrastructure for the seminars. They were appointed for interview by local facilitators in each municipality. The interviews averaged between 40 minutes and 1 hour, following a semi-structured guide: manager profile, implemented programs and projects to promote child growth and development, intersectoral collaboration experiences, and local governance for intersectoral collaboration in their territories. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic hampered the continuity of interviews with managers in March 2020. As all participants were outside this study’s geographic area, we decided to conduct Skype interviews. Skype provided synchronous visual and audio interaction between the researcher and participants, so the interview could remain a “face-to-face” experience (Hanna, 2012). The software recorded both the visual and audio interactions of the interviews, and the audio was transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

The principles of ANT guided the data coding system and the reconstruction of intersectoral relationships and interactions between the actors under study. The material from the three sources of evidence was decomposed by content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004), in line with the following preconceived descriptive codes: links among actors; the presence of controversies and resolution mechanisms; presence and role of mediators and intermediaries; and an alignment of actors, resources, and support (Bilodeau et al., 2019).

Reliability was ensured through collaborative analysis of the data. APGC initially identified preconceived codes across participants’ responses from the interview and in the observational field notes. Through constant and repeated readings, specifically involving attention to common codes, RCF and MIBS collaborated with APGC to develop specific categories (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004), which reflected participants’ social interactions aimed at intersectoral collaboration in their work experiences in promoting early child growth and development. The three researchers analyzed ecomaps by their three specific aspects—relationships, social networks, and supports, according to Hartman (1978) and validated by more contemporary researchers (Johnson et al., 2017; Silveira & Neves, 2019; Woodgate et al., 2020), as well as by preconceived codes. Table 1 shows the main categories informed by analyzing the three sources of evidence. The final data analysis stage involved a reflexive and interpretative process in extrapolating themes (Moser & Korstjens, 2018), which most prominently addressed how trainees constructed their intersectoral interactions in work settings. Discussions among researchers occurred throughout the analysis: discussion, creating and condensing categories, and refining and deepening the themes by drawing on existing literature.

Table 1.

Table of the Main Categories Informed by Analyzing the Three Sources of Evidence (Ecomaps, Field Notes of Participant Observation, and Interviews).

| Sources of evidence | Categories |

|---|---|

| Ecomaps | - Broad, diverse network |

| - Weak and tenuous relationships | |

| - No need to expend energy | |

| - Little support | |

| - Non-stressful relationships | |

| Field notes of participant observation | - Lack of information about sectors |

| - Lack of connection between services and municipal departments | |

| - Fragile relationships with sport, leisure, culture, and structural sectors | |

| - Unclear concept of intersectoral collaboration | |

| - Local professionals do not participate in intersectoral discussion groups | |

| - Initial action is always someone else’s responsibility | |

| - Map elaboration provided new information about areas | |

| - Difficult enrollment in Projeto Nascente | |

| - Family Health Strategy teams irregularly represented in Projeto Nascente | |

| - Professionals with promotion potential for intersectoral collaboration | |

| - Strategic professionals in the implementation of programs | |

| - Double hiring of professionals as a possibility to build bridges | |

| Interviews | - Fragile relationships with sport, leisure, culture, and

structural sectors - Participation of sport, leisure, and culture as a permanent promise |

| - Local professionals do not participate in intersectoral discussion groups | |

| - Relationship difficulties even within institutional intersectoral programs | |

| - Planned actions remain sectorial | |

| - Initial action is always someone else’s responsibility | |

| - Absence of any systematic recommendations for intersectoral collaboration | |

| - Difficult enrollment in Projeto Nascente | |

| - Health criticized other sectors for not having an expanded view of health and health promotion | |

| - Asymmetrical position of health and social work in relation to health and social issues | |

| - Professionals with promotion potential for intersectoral collaboration | |

| - Strategic professionals in the implementation of programs | |

| - Double hiring of professionals as a possibility to build bridges | |

| - Formation of intersectoral committees | |

| - Matrix support to share knowledge, responsibility, and stimulate relationships | |

| - Case managers to coordinate case discussion | |

| - University support for innovation |

The analyses were conducted using MAXQDA2020 software. The texts were inserted into the software and properly coded. The ecomap’s data—actors’ names, grouped by sectors, and the characteristics of the relationships—were converted into texts and tabulated. MAXQDA diagrams helped in the interpretation of ecomap material.

Statement on Ethics

The present study underwent required review and approval by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (logged under protocol number 2.751.249), and all participants provided written informed consent. The participants were aware that their data might be used to develop knowledge on early child development and intersectoral collaboration topics.

Results

This study received 48 ecomaps from 19 of the 31 municipalities participating in Projeto Nascente. The number of ecomaps varied from one to ten according to the number of “intersectoral teams” in each municipality. Forty-eight different arrangement patterns of social networks and support for promoting child growth and development were observed in these ecomaps, which involved a series of actors (n = 33) from six different sectors (Supplemental Table 2, sectors and actors mentioned in the ecomaps).

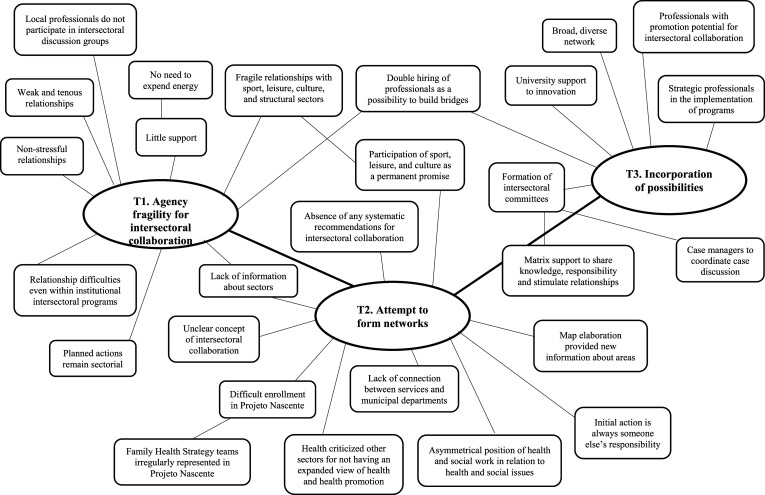

Our findings were organized into three primary themes: (1) agency fragility for intersectoral collaboration, (2) attempt to form networks, and (3) incorporation of fields of possibilities. The insights reflected within these themes highlighted the role of actors’ social interactions, and their resulting exposure to relationships and controversies, across different situations and settings. The interrelations between the themes and categories are visually presented in a thematic map (Figure 2). It illustrates the three themes, as well as the contribution of the categories in the extrapolation of each theme, those that contributed with more than one theme, and the categories that were related to each other.

Figure 2.

Thematic map showing the three themes abstracted through analysis based on developed categories.

Agency Fragility for Intersectoral Collaboration

Our research indicated a tendency for weak agency toward building intersectoral collaboration. Explaining this tendency, it was noted that the actors would often move mainly in endogenous ways, practicing isolated and non-shared forms of work in promoting early child growth and development. The findings were revealed from ecomap representations and reports from the managers and trainees. Despite the apparently broad and diversified network, the relationships between the FHS teams and the other actors were described mainly as weak or tenuous. The “intersectoral teams” reported no need to expend energy on most relationships, received little support from mentioned actors, and mapped the relationships as basically non-stressful.

All managers reported previous experience in intersectoral discussion groups of complex cases. Some of them described that the identification and choice of complex cases were not shared among them. A health manager said the case usually came from the education or social work sectors (see Table 2, the main categories of theme 1 identified in the interviews and quotes). She also claimed that she had received relevant information about the case from local health professionals and brought it up for discussion. This situation was confirmed by the other managers, who reported that discussion groups are formed mainly by sector managers. The participation of local professionals seems to be rare. The education and health sector, in particular, seemed to have more difficulty encouraging the participation of local professionals in case discussions, as mentioned by the social work manager. The actions planned for the cases remained sectorial.

Table 2.

Main Categories of Theme 1 Identified in the Interviews.

| Categories | Primary theme |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Agency fragility for intersectoral collaboration | |

| Local professionals do not participate in intersectoral discussion groups |

The school and the social [work], they usually bring... the question,

right? About who we're going to talk about... the demands. Then, then, what

happens, they propose a meeting every two months and at that meeting, they

bring a case report. A few days before, they gave me the names. I check with

the health team what is going on, who is the doctor, what about the medication

and the treatment, right? And then we sit down and discuss the case. (Health

Manager 1 – HM1) The school and the social [work], they usually bring... the question,

right? About who we're going to talk about... the demands. Then, then, what

happens, they propose a meeting every two months and at that meeting, they

bring a case report. A few days before, they gave me the names. I check with

the health team what is going on, who is the doctor, what about the medication

and the treatment, right? And then we sit down and discuss the case. (Health

Manager 1 – HM1) |

From the social work, it is the technicians [that participate], usually

representatives of CRAS [Centro de Referência de Assistência Social - Social

Work Reference Center] and CREAS [Centro de Referência Especializado de

Assistência Social - Specialized Social Work Reference Center]. From the

Department of Education are the managers, usually directors, not the secretary

of education herself, but they are usually managers who attend. (Social Work

Manager – SWM) From the social work, it is the technicians [that participate], usually

representatives of CRAS [Centro de Referência de Assistência Social - Social

Work Reference Center] and CREAS [Centro de Referência Especializado de

Assistência Social - Specialized Social Work Reference Center]. From the

Department of Education are the managers, usually directors, not the secretary

of education herself, but they are usually managers who attend. (Social Work

Manager – SWM) | |

We already have a meeting, you know, it works about every two months, we

have a meeting. But [from] health, it's the management area that participates;

so the health teams themselves, they didn't know about the existence of this

protection network. (SWM) We already have a meeting, you know, it works about every two months, we

have a meeting. But [from] health, it's the management area that participates;

so the health teams themselves, they didn't know about the existence of this

protection network. (SWM) | |

| Planned actions remain sectorial |

[...] the social [work] and education usually bring the problem; and from

the problem they bring we get together, each one in his/her own area, to see

where it can act to reverse that situation. We... talk about the strategies we

will adopt in the sector... in the secretariat, how... how each one of us

could help, right?... In the well-being of that child, right? How we are

going... to solve the problem the child is going through at that moment, the

family and everything else. And I do my best, in health [services], I see

the... appointments, if they’re taking the medication, if they’re consulting

with the doctor properly. Social [work] makes the visit... They also visit. If

the family needs a basic food basket, if the child goes to school, if he is

enrolled. (HM1) [...] the social [work] and education usually bring the problem; and from

the problem they bring we get together, each one in his/her own area, to see

where it can act to reverse that situation. We... talk about the strategies we

will adopt in the sector... in the secretariat, how... how each one of us

could help, right?... In the well-being of that child, right? How we are

going... to solve the problem the child is going through at that moment, the

family and everything else. And I do my best, in health [services], I see

the... appointments, if they’re taking the medication, if they’re consulting

with the doctor properly. Social [work] makes the visit... They also visit. If

the family needs a basic food basket, if the child goes to school, if he is

enrolled. (HM1) |

| Relationship difficulties even within institutional intersectoral programs |

So, I think there is a lack of commitment on the part of the education

department, especially in the Programa Saúde na Escola. We go... we set some

goals... that in the end we can't achieve. And, yes, of course we have

responsibilities, but there is a lack [of action] on the education side as

well. (HM2) So, I think there is a lack of commitment on the part of the education

department, especially in the Programa Saúde na Escola. We go... we set some

goals... that in the end we can't achieve. And, yes, of course we have

responsibilities, but there is a lack [of action] on the education side as

well. (HM2) |

| Fragile relationships with sport, leisure, culture, and structural sectors |

No, we don't think so yet. They [sport and culture] participate a lot...

when we are going to do, for example, an activity in the square. Then they

provide sound [equipment], which we don't have. They have a better sound

[equipment]. So they, they help us like this, providing sound, providing

space, something we need. They help with publicity, they help, you know,

whatever we need in terms of publicity, they help us. But specific, like...

some kind of planned activity, a project, we don't have with the Department of

Culture. (HM2) No, we don't think so yet. They [sport and culture] participate a lot...

when we are going to do, for example, an activity in the square. Then they

provide sound [equipment], which we don't have. They have a better sound

[equipment]. So they, they help us like this, providing sound, providing

space, something we need. They help with publicity, they help, you know,

whatever we need in terms of publicity, they help us. But specific, like...

some kind of planned activity, a project, we don't have with the Department of

Culture. (HM2) |

| Double hiring |

As the NASF [Núcleo de Apoio à Saúde da Família - Family Health Support

Center] nutritionist also works in the education department, I invited her to

be part of the Projeto Nascente. Indirectly, education would also be part of

it. And as one of the NASF psychologists, she also works 20 hours at the NASF

and another 20 hours in social work. So, I also invited her to try to take the

project to social work. (HM3) As the NASF [Núcleo de Apoio à Saúde da Família - Family Health Support

Center] nutritionist also works in the education department, I invited her to

be part of the Projeto Nascente. Indirectly, education would also be part of

it. And as one of the NASF psychologists, she also works 20 hours at the NASF

and another 20 hours in social work. So, I also invited her to try to take the

project to social work. (HM3) |

Managers described relationship difficulties even within institutional programs, such as Programa Saúde na Escola (School Health Program, PSE) and Bolsa Família Program (income transfer program). Despite the expected intersectoral planning and execution, they demonstrated limited agency even in discussing program-related issues.

Relationships with sectors other than education and social work were rarely mentioned by managers (in interviews) and professionals (in seminars), although the whole range of social problems was reported and recognized by them. They said that relationships with sports and culture sectors were restricted to providing places and sound equipment for health promotion and health-talk sessions. They reported a regular partnership with the Environmental Department in the fight against dengue and other arboviruses. None of them mentioned the structural sectors of municipal administrations, such as finances, public construction, and infrastructure areas.

In seminars, many professionals at Núcleo de Apoio à Saúde da Família (Family Health Support Center, NASF) were also hired by education or social work sectors. 2 These dual-hire workers were the only education or social work professionals in the “intersectoral team” in some seminars. Interviewed managers also talked about the double hiring of some local professionals. They considered this aspect of being a way to improve communication between sectors.

Attempt to Form Networks

The most common relationships were observed among the health, education, and social work sectors. These were also the most commonly represented in the ecomaps and almost the only ones mentioned by interviewed managers and present in the observed seminars. Despite many citations in ecomaps and the historical ties built between them, fragile bonds and a low search for strengthening relationships were observed.

Despite the whole range of models of the social network presented in ecomaps, this variety was not identified either among the professionals enrolled in Projeto Nascente (as described above) or in the observed seminars. The FHS teams were irregularly represented in training seminars even though they were the majority in the “intersectoral teams.” In municipalities with more than one FHS team, not all teams participated. It was not uncommon to find incomplete teams, usually with the absence of either the doctor or the nurse. After the seminar, one facilitator told the researcher that the health secretary asked one doctor not to go to the training. In the same municipality, the Department of Health cut the seminars’ snacks in the middle of the course.

Many participants said that the elaboration of the ecomaps brought new information about the areas, as they were surprised by the number of actors found. Curiously, they identified these actors as some form of support in addition to their actions:

What do you have in this service to contribute to child development? (A nurse, in seminar)

In seminars, participants expressed the importance of partnership and communication between the healthcare team and other sectors. They mentioned needing support to respond together to children and family problems. However, most complained about a lack of information, especially concerning sectoral operations, contact, and access rules. Discussion groups were not cited during seminars as they were in managers’ interviews.

The seminar allowed professionals to discuss the concept of intersectoral collaboration. We noticed that the participants stated some consensus, although having an incomplete or inaccurate understanding of the term. They defined intersectoral collaboration as a “partnership” with a “sharing of responsibilities and actions” to solve “complex problems.” Most of them highlighted that the partnership occurs according to a superior’s decision or was inserted into institutional programs.

From the professional’s point of view, the initial action to intersectoral collaboration was always someone else’s responsibility. When asked about proposed shared actions to promote child growth and development, the participants offered sectoral proposals in design and action. They did not think about strategies for articulating services in the areas. They even spoke about a network but in a generic and disjointed way. Most participants in the seminar reported that they were part of a network and, at some point, “the network should be activated.” However, another actor, generally from another sector, must “activate the network”; this was never the speaker’s responsibility.

Sports, leisure, and culture professionals did not participate in the observed seminars. All interviewed managers expressed the need and the importance of the participation of these three sectors. However, they also complained about a lack of participation and support of these sectors. In general, the participation of the three sectors appeared to be a promise that never came true.

Despite keeping local health professionals away from existing discussion groups of complex cases, health managers expressed the need for FHS teams to become part of the area (see Table 3, the main categories of theme 2 identified in the interviews and quotes). However, no systematic guidelines were found for intersectoral collaboration with other actors in the area. No pathways, plans, and support mechanisms were identified, given that the managers’ statements were almost always generic and evasive.

Table 3.

Main Categories of Theme 2 Identified in the Interviews.

| Categories | Primary theme |

|---|---|

| Theme 2: Attempt to form networks | |

| Participation of sport, leisure, and culture as a permanent promise |

[...] to set up an intersectoral commission, education is involved, social

[work] is involved, and sport, you know..., they could not participate in, in

the meeting. [...] (HM1) [...] to set up an intersectoral commission, education is involved, social

[work] is involved, and sport, you know..., they could not participate in, in

the meeting. [...] (HM1) |

And then we will have now, making up the team for the next... meeting, a

representative of, of the secretary of sport. [...] (HM2) And then we will have now, making up the team for the next... meeting, a

representative of, of the secretary of sport. [...] (HM2) | |

In addition to education, it was proposed to ask... to invite the social

[work], culture, sport, to help develop the activities [...] of the

intersectoral work. (HM3) In addition to education, it was proposed to ask... to invite the social

[work], culture, sport, to help develop the activities [...] of the

intersectoral work. (HM3) | |

| Absence of any systematic recommendation for intersectoral collaboration |

We leave... them [FHS teams] free to visit schools, to develop activities.

Yes, right there in the children's daily lives, to see what could be done. So,

the Department of Health, we leave them free to be close to the children while

it is... education, as a school, as a project, of social assistance, to work

better, even better with... understanding what children really need.

(HM3) We leave... them [FHS teams] free to visit schools, to develop activities.

Yes, right there in the children's daily lives, to see what could be done. So,

the Department of Health, we leave them free to be close to the children while

it is... education, as a school, as a project, of social assistance, to work

better, even better with... understanding what children really need.

(HM3) |

| Health criticized other sectors for not having an expanded view of health and health promotion |

‘Ah, but this is the responsibility of the health [sector], this is not my

job’, right? ‘Ah, but why do these people come here to school to do this kind

of thing? Oh no, but the health [sector] has to take care of dengue. I have

nothing to do with dengue.’ Right? (HM2) ‘Ah, but this is the responsibility of the health [sector], this is not my

job’, right? ‘Ah, but why do these people come here to school to do this kind

of thing? Oh no, but the health [sector] has to take care of dengue. I have

nothing to do with dengue.’ Right? (HM2) |

| Asymmetrical position of health and social work in relation to health and social issues |

They [education workers] don't have it, it seems they don't have our

vision. Well, I think the view of health is a differentiated view. We find

places of work, places for intervention, we go beyond schools. Today we work

with other programs, we can work in churches. How if we already work with

churches! Who invites us to participate, right? We work... with day care

centers, you know, with other types of space... that favor health education.

(HM2) They [education workers] don't have it, it seems they don't have our

vision. Well, I think the view of health is a differentiated view. We find

places of work, places for intervention, we go beyond schools. Today we work

with other programs, we can work in churches. How if we already work with

churches! Who invites us to participate, right? We work... with day care

centers, you know, with other types of space... that favor health education.

(HM2) |

I felt a little uncomfortable because most health professionals think that

everything is a social problem; that everything is a problem for the social

[work] to solve, that everything is the social [work] that must do. So... to a

certain extent, I was even a little worried and afraid, because it seems that

the social doesn't want to do it. And then they take the social as the person

who is there, right? And I'm not the social, I'm not the person who carries

out the policy alone. So, at a certain point it was important to clarify, what

is my role, right, within the social [work]. There are a lot of things that

they think are social [problems], it's not social, it's public safety. Many

things that they think are social [problems] can be worked on by the FHS

teams. (SWM) I felt a little uncomfortable because most health professionals think that

everything is a social problem; that everything is a problem for the social

[work] to solve, that everything is the social [work] that must do. So... to a

certain extent, I was even a little worried and afraid, because it seems that

the social doesn't want to do it. And then they take the social as the person

who is there, right? And I'm not the social, I'm not the person who carries

out the policy alone. So, at a certain point it was important to clarify, what

is my role, right, within the social [work]. There are a lot of things that

they think are social [problems], it's not social, it's public safety. Many

things that they think are social [problems] can be worked on by the FHS

teams. (SWM) |

By contrast, local health professionals participating in the seminars complained of “being alone.” They spoke about the weak management support for expanded actions within the areas. They drew our attention to the lack of connection between community services and sectors and reported not having access to a detailed diagnosis of the living conditions of the population in the region.

In addition to the limited agency in discussing issues related to institutional programs already mentioned, a series of difficulties were observed in sharing responsibilities and actions in building networks. Health professionals criticized other sectors for not having an expanded view of health and not collaborating in health promotion actions, including a health manager citing teachers’ statements in schools. Moreover, health professionals tended to place themselves in an asymmetrical position when compared to the other sectors in terms of health promotion. The social work manager also reported that health professionals have difficulties dealing with social problems. As they do not understand the issues, they attributed greater responsibility to social work, even concerning actions that the health team should carry out.

Incorporating Fields of Possibilities

This theme explored how the present study’s findings support incipient intersectoral collaboration in municipalities, which is viewed as a field of possibilities to promote better child growth and development. “Intersectoral teams” recognized a broad and diverse network. Even in small municipalities, they identified services and services for potential partnerships.

Some professionals, such as community health agents, nurses, and NASF teams, seemed to have the potential to promote intersectoral interactions. Community health agents were the most common professional category among those enrolled in the Projeto Nascente (35.8%). The health managers considered them and the nurses to be strategic professionals in implementing projects in the municipalities (see Table 4, the main categories of theme 3 identified in the interviews and quotes). Recognition of the innate role of nurses as managers of health teams and as cluster promoters was also observed in seminars. As already described above, the managers identified the double hiring of NASF professionals as a way to connect the sectors. In fact, the observation of seminars suggested that NASF professionals greatly facilitated conversations with actors from other sectors. They could also help identify resources in the communities.

Table 4.

Main Categories of Theme 3 Identified in the Interviews.

| Categories | Primary theme |

|---|---|

| Theme 3: Incorporating fields of possibilities | |

| Professionals with potential to promote intersectoral collaboration |

So, I invited four [nurses], from four FHS teams, the four nurses

participated [in the Projeto Nascente], and from two teams the... the

community health agents participated. The agents of the other two teams did

not participate. But my goal is that... they will be future facilitators in

order to really be able to... foster the implementation of the policy [to

promote child development]. (HM2) So, I invited four [nurses], from four FHS teams, the four nurses

participated [in the Projeto Nascente], and from two teams the... the

community health agents participated. The agents of the other two teams did

not participate. But my goal is that... they will be future facilitators in

order to really be able to... foster the implementation of the policy [to

promote child development]. (HM2) |

| Formation of intersectoral committees |

There is a low intersectoriality in the municipality, right? The sectors

talk very little to each other. And so we need the committee. It will make it

possible for everyone to know the progress of the actions, right, make the

communication among the city's sectors easier. (SWM) There is a low intersectoriality in the municipality, right? The sectors

talk very little to each other. And so we need the committee. It will make it

possible for everyone to know the progress of the actions, right, make the

communication among the city's sectors easier. (SWM) |

The [intersectoral] collaboration, I believe that now, it will be better

configured, with the intersectoral committee and with the matrix support that

we did not have. So, I believe that is it, a cultural issue, of work format,

you know. The public sectors are [not] used to and now, a new vision is

coming. (HM1) The [intersectoral] collaboration, I believe that now, it will be better

configured, with the intersectoral committee and with the matrix support that

we did not have. So, I believe that is it, a cultural issue, of work format,

you know. The public sectors are [not] used to and now, a new vision is

coming. (HM1) | |

There is a very vulnerable area. Really, very vulnerable, you know? So they

[FHS team] wanted to work on a way that they could actually have this matrix

support and have this intersectoral support for families, because it is

imperative to do something there. One of the intervention projects [as result

of Projeto Nascente] was the creation of an intersectoral committee. Then we

already had a first meeting, it was on last Friday, to set up the committee,

and to plan, you know, what will be the objectives of the committee, how are

we going to work, what will be the role of the committee, right? And then,

within this committee, we created a matrix support form. Vulnerability cases

will be discussed at committee meetings, matrix support will be carried out.

The next committee meeting is scheduled, and the remaining actions are already

discussed, programmed and proposed within the matrix support. We are thinking

it is going to be okay. (HM1) There is a very vulnerable area. Really, very vulnerable, you know? So they

[FHS team] wanted to work on a way that they could actually have this matrix

support and have this intersectoral support for families, because it is

imperative to do something there. One of the intervention projects [as result

of Projeto Nascente] was the creation of an intersectoral committee. Then we

already had a first meeting, it was on last Friday, to set up the committee,

and to plan, you know, what will be the objectives of the committee, how are

we going to work, what will be the role of the committee, right? And then,

within this committee, we created a matrix support form. Vulnerability cases

will be discussed at committee meetings, matrix support will be carried out.

The next committee meeting is scheduled, and the remaining actions are already

discussed, programmed and proposed within the matrix support. We are thinking

it is going to be okay. (HM1) | |

| Matrix support |

We do the meeting, we delegate functions, you know, do the matrix support

and each professional is in charge of... of developing some activities, trying

to solve the problem that was discussed. (SWM) We do the meeting, we delegate functions, you know, do the matrix support

and each professional is in charge of... of developing some activities, trying

to solve the problem that was discussed. (SWM) |

They [FHS teams] pointed out the issue of... matrix support, right? We have

been carrying out matrix support here in terms of health care, together with

the FHS teams, NASF, mental health team, too. But this matrix support has to

be broad, it has to involve the Department of Education, the school. It has to

involve the... the Department of Social Work, CRAS [Centro de Referência de

Assistência Social - Social Work Reference Center], CREAS [Centro de

Referência Especializado de Assistência Social - Specialized Social Work

Reference Center]. The Children Tutelary Council. And the proposal... made by

this team, was the matrix support and the intersectoral work with these

professionals. So... it's really important that we develop this work in a

broad conversation, right, so the service becomes more effective, and we can

give better answers to our users. (HM3) They [FHS teams] pointed out the issue of... matrix support, right? We have

been carrying out matrix support here in terms of health care, together with

the FHS teams, NASF, mental health team, too. But this matrix support has to

be broad, it has to involve the Department of Education, the school. It has to

involve the... the Department of Social Work, CRAS [Centro de Referência de

Assistência Social - Social Work Reference Center], CREAS [Centro de

Referência Especializado de Assistência Social - Specialized Social Work

Reference Center]. The Children Tutelary Council. And the proposal... made by

this team, was the matrix support and the intersectoral work with these

professionals. So... it's really important that we develop this work in a

broad conversation, right, so the service becomes more effective, and we can

give better answers to our users. (HM3) | |

| Case managers |

We do the entire meeting, and then we delegate it to the responsible

person, to pass it on to other... competent services, right? (HM4) We do the entire meeting, and then we delegate it to the responsible

person, to pass it on to other... competent services, right? (HM4) |

It is very easy to say that the problem is someone else's, right, and not

take the problem for yourself. So, you know... when it becomes clear what is

the problem, who is involved, what are the actions that will be done and who

are responsible for the action, as is the proposal we made... with the

committee, maybe this makes it easier, improve intersectoriality. (SWM) It is very easy to say that the problem is someone else's, right, and not

take the problem for yourself. So, you know... when it becomes clear what is

the problem, who is involved, what are the actions that will be done and who

are responsible for the action, as is the proposal we made... with the

committee, maybe this makes it easier, improve intersectoriality. (SWM) | |

| University support |

We have the rural internship from UFMG [Faculty of Medicine, Universidade

Federal de Minas Gerais]. We have... absorbed many ideas from, from academics,

because they have already worked, they have already done the internship in

other cities as well, they managed to absorb a lot of experience there, so

they bring us this information and we apply it here, in our daily routine.

(HM3) We have the rural internship from UFMG [Faculty of Medicine, Universidade

Federal de Minas Gerais]. We have... absorbed many ideas from, from academics,

because they have already worked, they have already done the internship in

other cities as well, they managed to absorb a lot of experience there, so

they bring us this information and we apply it here, in our daily routine.

(HM3) |

They’ve widened the vision! So, training [Projeto Nascente] is something

that should happen more, because from the training they [professionals]

managed to broaden their vision and understand that the work carried out

previously was multisectoral and not intersectoral and to engage for the

creation of this committee. So, I believe that the engagement of

professionals, through training, is a factor that has made it much easier for

us. (HM4) They’ve widened the vision! So, training [Projeto Nascente] is something

that should happen more, because from the training they [professionals]

managed to broaden their vision and understand that the work carried out

previously was multisectoral and not intersectoral and to engage for the

creation of this committee. So, I believe that the engagement of

professionals, through training, is a factor that has made it much easier for

us. (HM4) |

Managers highlighted that Projeto Nascente started a process to encourage the formation of intersectoral committees and matrix support actions. They described matrix support as a strategy for integrating practices from different sectors in the perspective of horizontal collaborative relationships. They expressed that having opportunities for debate would play a crucial role in action planning to address complex cases involving children and their families. They emphasized the importance of connecting key actors from different sectors so that professionals know the details of the cases to contribute to the discussion and problem solutions. These initiatives seemed to involve care professionals more broadly, not just managing ones.

The involvement of professionals focused on practical support for identified problems. Actions were still thought about and articulated by sectors. Coordination and integration of care and action emerged in a very incipient way. The strategies mentioned by the managers contemplated notions of reference professionals and case managers in order to manage the discussions and maintain the workers’ active ties with the cases.

The “intersectoral teams” reported few experiences with intersectoral collaboration initiatives at the seminars other than those related to institutional intersectoral programs. They reported that this was not a common practice for them. However, beginning and straightforward experiences were described, with collaborative work and potential for more consistent future collaborations. One example was the report on restoring the covers of 60 child health booklets.3 The action was conceived by Centro de Referência de Assistência Social (Social Work Reference Center, CRAS) professionals and the FHS team; teachers were responsible for disseminating information to parents. The action was carried out during a week of school recess, at the CRAS office, by professionals from the social work and health areas, with material provided by the involved sectors.

Some managers highlighted the importance of improvement and access to new theoretical and practical knowledge. This regular and continuous support they received from the university was fundamental in developing Projeto Nascente and discussing intersectoral collaboration.

Discussion

The contribution of our analysis expands the current understanding of the complexity of the challenges of the socialization process aimed at intersectoral collaboration. Three main themes highlighted the socio-technological and political contents that underlie this process. Our results showed that intersectoral collaboration for promoting child growth and development is fragile. When there was local potential, it was missed or underused. In light of ANT, our results demonstrated the scarcity of action by mediators and intermediaries to promote enrollment processes for intersectoral collaboration. Likewise, the many existing controversies were not used to trigger changes.

Generating Interessement and Producing Enrollment of Actors for Promoting Child Development

Our findings on the professionals’ interactions allowed us to identify both their local and organizational relational priorities, practically restricted to sector guidelines. In this way, we recognized a paucity of enrollment processes that do not allow them to recognize potential collaborative partners and carry out a collaborative and integrated action plan designed to promote child growth and development. Callon (2006) and Djohy (2019) described the collaboration as a socialization process of producing such resources as knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes. It depends on socio-technologically implemented policies, with an actor’s enrollment in a network of other actors. For successful enrollment, various social (actors) and technological (equipment, email, documents, publications, financing, working contracts) allies must be mobilized. This approach will help to build a solid foundation for every child to receive nurturing care, with the conditions that promote health, nutrition, security, safety, responsive caregiving, and opportunities for early learning (WHO, 2018).

Little sharing of knowledge was found within the sectors themselves and among them. Meetings and conversations among professionals seemed scarce. Forums and discussion groups dealing with complex family cases tried to use an intersectoral approach. However, many weaknesses and gaps made this process difficult, including the managers’ understanding that local professionals should not frequent these spaces. There was a lack of space for discussion and argumentation among sectors and even between local professionals and managers of the same sector. This low sharing of knowledge and responsibilities, associated with the lack of information about the existing social network in the areas, seemed to indicate a low movement of actors within the network. Kuruvilla et al. (2018) and van Dale et al. (2020) emphasized the importance of the interaction dimension in the construction of intersectoral collaboration. According to the authors, it was vital to systematically develop and strengthen synergies between actors and sectors to promote multi-actor dialogues and deliberation for case resolution. As Laurin et al. (2015) demonstrated, sharing knowledge served as a catalyst for intersectoral action, reflected in the increased size and strength of the actor-network and the formalization of the highly anticipated collaboration between sectors involved in early childhood care.

The perceived lack of leadership in favor of intersectoral collaboration reinforced the fragility or absence of the translation process with this objective. Whether in the health sector or not, the managers themselves needed to assume the role of leaders, training and exercising this skill (Hendriks et al., 2015). In cases where the involvement of professionals was irregular, leadership helped connect specific technical sectors and involved a wide range of stakeholders (Kuruvilla et al., 2018; van Dale et al., 2020).

Our analysis revealed a rhetorical discussion about intersectoral collaboration but almost no practice. While the findings showed a theoretically receptive speech of the management to external intervention (Projeto Nascente), they also highlighted an irregular enrollment of FHS teams and professionals from other sectors. Our study also identified the manager of a Health Department interfering negatively during the intervention, by asking a doctor not to participate in the training and not encouraging the event. The use of strategies by powerful actors hindered the empowerment and engagement of local professionals. How to align the interests of the involved actors, including management, for better socialization to sustain the changes aimed at intersectoral collaboration? Current models considered that successful networks of aligned interests were created by recruiting a sufficient body of allies and translating their interests into the thinking and acting that maintained the network (Bilodeau et al, 2019; Ceballos-Higuita & Otálvaro-Castro, 2021; Okeyo et al., 2020; Potvin et al., 2005). Likewise, Andrade et al. (2015) and Holt et al. (2018) found that abstract rhetoric could diffuse responsibility without priorities rather than directly addressing the challenges.

Identified Mediators

Our analysis led us to identify nurses, community health agents, and professionals linked to more than one sector as possible mediators that could contribute to overcoming gaps. We considered them as potential mediators that have been underused in the enrollment process. Management must be attentive and encourage the enrollment of these actors. This action would involve bringing together multiple components, such as key stakeholders, resources, and tools to support interaction and build intersectoral collaboration. All these components should contribute to exchanging information and sustaining the work as mediators of interessement and enrollment (Borvil et al., 2021; Djohy, 2019; Hendriks et al., 2015).

The findings suggest that integrating mechanisms proposed by institutional intersectoral policies (PSE and the Bolsa Família Program) were poorly implemented or not implemented at all. Despite being programs with other specific objectives, the exercise of intersectoral collaboration could be a learning experience and a powerful mediator for shared actions aimed at early childhood development. Furthermore, this would be an important opportunity to ensure the expansion of integrated and appropriate approaches to early childhood development (Engle et al., 2011).

The findings from the present study revealed some potential integrative mechanisms for intersectoral collaboration developed from the Projeto Nascente. This supported the notion that intervention projects and universities may be potential mediators in promoting and disseminating changes. The reported intersectoral committees might act as a promoter of enrollment. They constitute a privileged space for the performance of intersectoral collaboration, enabling meetings, the exercise of arguments, and the possibility of discussing and resolving controversies. Through the tools presented in this study, such as matrix support, reference professionals, and case managers, workers can increase their understanding of other sectors’ routine actions, increasing the possibilities for collaboration. It will be an opportunity for them to improve their skills in reframing issues so that actors from other sectors understand their influence on issues (Hendriks et al., 2015; van Eyk et al., 2020). This could contribute, for example, to the design of more comprehensive interventions in addressing young children’s needs, especially supporting responsive caregiving and opportunities for early learning (WHO, 2018).

Unfolding of Controversies

Regarding the formats and patterns of interaction in the network, this case study showed a self-perceived centrality and agency of the sectoral professionals and managers. This centrality generated an asymmetrical position between the actors of the different sectors, which maintained a latent, never-ending controversy. As the literature shows, there are risks associated with an extreme emphasis on sectoral issues and outcomes when seeking collaboration with actors from different sectors. Therefore, it is deemed crucial that public intersectoral policy objectives are not perceived as an additional burden by sectors and that their implementation considers a power-sharing scenario (Borvil et al., 2021; Kriegner et al., 2021; Okeyo et al., 2020). These concerns are consistent with what is referred to as “health imperialism”—understood as defining an agenda from a health perspective alone, only considering how other sectors can contribute to the health goals without recognizing the interests of other sectors (Kriegner et al., 2021; Nutbeam, 1994).

The findings also suggested other unresolved controversies: the enormous difficulty in calling sectors outside the social sectors, such as culture, leisure, and sport; managers who did not disclose and did not allow the participation of professionals in discussion groups on complex cases; and the lack of information about the existing equipment in the regions where the FHS teams work. Through the unfolding of controversies, the translation process can promote new participant enrollment, stabilize uncertainties, and develop interaction in the network through contradictory arguments and points of view (Callon, 1986; Latour, 2005).

This article reflected and supplemented the literature on intersectoral collaboration, and its findings highlighted the need to embed local actors, resources, and structures into networks. The importance of investing in ongoing and open communication and information management among stakeholders was also evident. These components, discussed, negotiated, and rearranged in a participatory way, could support intersectoral collaboration and foster health promotion and equity impacts. ANT advocates that the context is constructed by the action, mainly by the interaction of the actor networks. The need for continued commitment becomes clear when pursuing coordinated action embedded with integrative mechanisms that induce enrollment to achieve this goal. In this way, the enrollment of professionals and managers in an actor-network oriented toward child development will have profound implications for family life, children’s lives, and the ways in which childhood is understood and practiced.

Implications for Intersectoral Collaboration Promoting Child Development

An integrated and intersectoral model for promoting child growth and development requires the active participation of various human actors with specific roles and the inclusion of technologies, tools, plans, and activities (Latour, 2005). We believe management needs to adopt a more assertive and pragmatic vision for understanding how to encourage collective work, placing the actor-network at the center of the discussion. According to Latour (2005), innovations arise from collective existence. Indeed, a wide range of social, organizational, economic, psychological, or personal conditions could work as mediators, influence the enrollment process, and generate innovation. In this light, the present study’s findings reveal fields of possibilities that can be summarized in three questions:

1. Key actors, services, or organizations in each municipality that could coordinate and facilitate resource links: who might play the role of coordination to improve access and interaction between sectors and services in promoting child development?

2. Resources or management tools that will help managers and local professionals to manage actions and processes over time: which resources might be essential to support the self-management process?

3. Communication tools or digital technologies that can support a local community model of health and promote child development: how might available technologies be used to support the communication process between sectors and improve access to different services?

Limitations

In closing our article, it is important to note some of this study’s limitations. It was not possible to recruit many municipal managers, which may have impacted the range of insights generated about the management perspectives. To overcome this limitation, it was necessary to explore the greatest interpretive depth of respondents’ insights. Moreover, the low participation of workers from sectors outside the health sector brought a health bias in the view of “intersectoral teams,” especially in the elaboration of ecomaps. Thus, data on the relationships and ties among the services of the various sectors represented in the ecomaps need to be interpreted with caution. The design of the project was sectoral, centralized by the health sector. The Projeto Nascente came from a partnership between the Ministry of Health of Brazil and the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. The facilitators were only health professionals because the many subjects in the training program demanded specific knowledge. However, they were oriented to motivate intersectoral collaboration to contribute to overcoming the difficulties of promoting child development.

Furthermore, this study took place in small towns in Brazil and, therefore, may lack transferability to other contexts, including industrialized regions of our country and of the world. Small municipalities in low-income countries tend to have a fragile service network. This fragility can influence the organization and provision of social protection actions. There is also a low level of governance, with high political interference in determining government actions.

The process of monitoring and evaluating the change in the studied context was not part of this study, although Projeto Nascente is part of an impact assessment research and production of evidence of intersectoral actions to promote child development. While these limitations will warrant attention in future studies, the present work represents an important contribution to studies of intersectoral collaboration in promoting child growth and development, specifically, and in health promotion, more comprehensively. Given the subject’s relevance, we hope that this study’s considerations can prove an important contribution to the emerging body of scholarship in this area, which will likely continue raising questions for social and health researchers.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Intersectoral Collaboration to Promote Child Development: The Contributions of the Actor-Network Theory by Antônio Paulo Gomes Chiari, Maria Inês B. Senna, Viviane Elisângela Gomes, Geraldo C. Cury, Maria do Socorro M. Freire, Anna Rachel dos S. Soares, Claudia Regina L. Alves, and Raquel C. Ferreira in Qualitative Health Research

Notes

In Brazil, different public policies do not share territorial divisions (Bronzo, 2016).

Brazilian civil servants work 20, 30, or 40 hours a week. A worker on a 20-hour shift can be double-hired.

The child health booklets are distributed for free to all Brazil-born children and given to families. It is the tool recommended by the Ministry of Health to monitor children’s health, growth, and development up to 10 years of age (Amorim et al., 2018).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the Ministério da Saúde (No. TED MS/FNS no. 62/2017) , Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (No. 001) and Raquel C. Ferreira received financial support from FAPEMIG, Brazil (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) – Programa Pesquisador Mineiro, PPM-00603-18).

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Antônio Paulo Gomes Chiari https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4104-9164

Claudia Regina L. Alves https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0885-1729

References

- Amorim L. P., Senna M. I. B., Soares A. R. S., Carneiro G. T. N., Ferreira E. F., Vasconcelos M., Zarzar P. M. P., Ferreira R. C. (2018). Assessment of the way in which entries are filled out in child health records and the quality of the entries according to the type of health services received by the child. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 23(2), 585–597. 10.1590/1413-81232018232.06962016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade L. O. M., Pellegrini Filho A., Solar O., Rígoli F., Salazar L. M., Serrate P. C. F., Ribeiro K. G., Koller T. S., Cruz F. N. B., Atun R. (2015). Social determinants of health, universal health coverage, and sustainable development: Case studies from Latin American countries. Lancet, 385(9975), 1343–1351. 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61494-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J., Grant N. S. (2016). Using an ecomap as a tool for qualitative data collection in organizations. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human. Resource Development, 28(2), 1–13. 10.1002/nha3.20134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]