Abstract

Policy Points.

Systems based on primary care have better population health, health equity, and health care quality, and lower health care expenditure.

Primary care can be a boundary‐spanning force to integrate and personalize the many factors from which population health emerges.

Equitably advancing population health requires understanding and supporting the complexly interacting mechanisms by which primary care influences health, equity, and health costs.

Keywords: population health, primary health care, generalism, general practice, health equity, health expenditures, physician–patient relationship, care integration

In widely quoted ecological analyses, primary care is associated with population health. 1 , 2 Not only with population health, 3 , 4 but with health equity, 5 , 6 health care quality, 7 , 8 and lower health care expenditure 1 , 4 , 9 , 10 —a pretty good definition of value. 11

Yet, there is a paradox about primary care. 12 Despite these desirable population‐level attributes, at the disease level at which we typically measure, incentivize, and organize the work of health care, when assessed with one‐disease‐at‐a‐time quality measures, primary care does not perform as well as care focused on a single disease.

What is going on here? In caring for patients’ individual diseases, primary care appears to offer lower quality than specialty care. But at the population level of countries, systems, and municipalities—if we organize around primary care, we get better health, equity, quality, and value? 12 , 13 How can this be?

Apparently there are some emergent properties of primary care in which a relationship with the whole—person, family, community—is more than the sum of its parts. 14 , 15 Not understanding this paradox, indeed feeling threatened by it, leads us to act on many potential health drivers in ways that do not have the intended effects on the health of people and populations and that indeed often make things worse. 15 , 16 , 17

This paper explores the ways in which primary care might influence population health by serving as a force for integration 18 across the often‐fragmented systems 19 influencing population health. In the course of that exploration, we will examine the complexly related mechanisms by which the craft of general practice, as a vital component of primary health care, leads to the emergent properties of health, equity, quality, and sustainable resource use. Then, we will consider two informative stories—one of a person living with multiple chronic conditions and social disadvantage, and a second person who is overserved and whose problems and opportunities do not fit neatly into little boxes. Next, we will examine how primary care might helpfully interact with the other influencers of population health investigated in this special issue of The Milbank Quarterly. We close with policy recommendations for federal, state, and health care system leaders.

Situating Primary Care

When people talk about primary care, they usually mean primary medical care. But there are related primary sources of care that also influence health. 20 The most proximate primary care involves people being supported by family, friends, neighbors, coworkers, and lay health peers. Primary medical care adds the particular expertise of the generalist clinician, often supported by a team, taking responsibility for health care services at the front door of the health care system, and connecting to specialized expertise when needed. 13 Primary health care adds the additional resources of public health and health‐related community organizations, nested within a larger sociocultural commitment, as exemplified in the lofty Declaration of Alma‐Ata. 21 , 22

Primary medical care, supported by the discipline and craft of generalist practice, is situated at the unsettled boundary region between the messy but meaningful lives of individuals, families, and communities, and the health care, public health, and social systems designed to support them. 23 Witnessing and acting at those junctures puts properly understood and supported primary care in a boundary‐spanning role 24 with a breadth that makes it both difficult to characterize and uniquely positioned to provide locally adaptable solutions. 22 In this paper, we use the term primary care in its most common use, referring to primary medical care offered by a generalist clinician supported by a primary care team.

The Locally and Personally Adaptable Generalist Approach

Effective primary care is based on a generalist approach that involves certain ways of being, knowing, perceiving, and doing. 25 , 26 Generalist ways of being include an open stance that is receptive to diverse perspectives and co‐created knowledge. It involves humility that comes from being connected in key relationships as a boundary spanner. Generalist ways of knowing require broad knowledge of self, others, systems, the natural world, and their interconnectedness. Generalist ways of perceiving involve seeing the world in ways that foster integration—scanning and prioritizing, then directing attention to the highest priority in that moment—in many moments over time, focusing on the particulars 27 while keeping the whole in view. Generalist ways of doing involve prioritized, joined‐up action that engages with the most important parts in context, 28 often doing multiple low‐level tasks to enable higher‐level integrative action over time—iterating among breadth/depth, subjective/objective, parts/whole, and action/reflection in service to a particular person and situation. 25

One of the desirable features of a generalist approach to primary care that makes it difficult to characterize is that it adapts to the particular 27 local needs of people, families, and communities. 29 , 30 This local adaptation occurs at the level of the clinician–patient relationship and manifests differently in different personal and sociocultural contexts. 28 , 31 It would not be surprising for six different patients from six different neighborhoods with the same elevated blood pressure reading to have six different care plans that simultaneously acknowledge the evidence‐based guidelines based on what works on average while accommodating their personal needs, capacities, and sociocultural context. Current top‐down quality improvement methods that attempt to reduce variability often are too crude to recognize the appropriate variability that represents personalized care. 15 , 31

Vertical and Horizontal Integration and Different Sociopolitical Manifestations of Primary Care

In our fragmented health systems, there are two ways of approaching integration. Vertical integration, typically organized around disease pathways, involves managing named disease conditions or risk factors for ill health. 32 It connects people's defined needs with specialized services across multiple levels of the system. 33 Horizontal integration, typically organized around whole people or communities with complex needs rather than disease‐specific conditions, involves broad‐based collaboration to improve overall health. 34 Comprehensive, whole‐systems integration includes a balance of both. 35

The linear processes of vertical integration are easier to understand and to organize in top‐down fashion. Vertical integration can be very helpful once problems have been characterized. It is a viable way to organize multiple specialized systems around a well‐defined need. But if health care is organized only around well‐characterized problems, then complex multifactorial, undifferentiated, and unexplained problems get short shrift. 36

The dynamic processes of horizontal integration require flexible systems that iteratively link on‐the‐ground experience with efforts to grasp the larger contexts in which they operate. Comprehensive primary care and public health can serve as forces for horizontal integration that make the vertically integrated systems more efficient and effective. However, in the United States, we have conceptualized and organized primary care and public health almost entirely as part of top‐down vertically integrated systems focused on problems rather than on people and communities, resulting in diminished effectiveness. 20 , 34 , 37

Local adaptation of the generalist function to specific individuals, families, and communities also is reflected in the wide variability of the primary care function at the sociopolitical and population level.

For example, Geoff Meads, in studying primary care in 31 countries undergoing primary care reforms, identified a typology of six different manifestations. 38 Interestingly, all six ways of organizing care are visible in the heterogeneous US system. In different settings, with different needs and resources, these manifestations of primary care vary in the degree to which they provide individual medical care and/or larger public health functions, and various degrees of horizontal and vertical integration. 35

Outreach franchises deliver primary care organized around a central hospital or sometimes administrative agencies, charities, companies, churches, councils, or communities. In this model, there rarely is coherence between the pattern of service delivery in one area and another. Vertical integration is centrally controlled by the hospital seeking to encourage access to specialized services. Horizontal integration is ad hoc and largely dependent on visionary leaders and chance. In the United States, this model is common in hospital systems that have purchased or affiliated with primary care practices to create service networks and feeder systems for their specialized services.

Reformed polyclinic organizational schemes originated in Russia as part of centralized planning for health care but more recently have attracted international interest as a way for specialist and generalist clinicians to connect at the local level without the need for coordinated service planning. Doctors convene, usually in the same building, and are paid for what they doeither directly by patients or through government subsidy. Vertical integration dominates with an emphasis on medical treatment of individual problems. But the overall value of a polyclinic must be interpreted in the light of other local services and the vision of the doctors. For example, in Sydney there is a strong parallel public health role in health promotion, whereas in Copacabana the polyclinic functions almost as a community development agency. In the United States, the Mayo and Cleveland Clinics are well‐known examples.

Extended general practice has its roots in post–World War II general practice that became separated from hospital development and identified with community services. It strongly emphasizes multidisciplinary working, and general practitioners have pivotal leadership roles, often shared with other team members. Sometimes, a health authority manages the contract for services through certain markers of achievement and negotiates practice involvement in local developmental work. It facilitates horizontal integration through its extended multidisciplinary team because interorganizational partnerships are usually too weak to support broader collaborations. It facilitates vertical integration by serving as a selective and personalized gateway to specialist care for those registered with the practice. In the United States, many private practice examples exist, often operationalized as patient‐centered medical homes, and some have become highly functional physician‐led accountable care organizations (ACOs).

District health system models have been promoted by the World Health Organization as a way to provide whole population care. Its philosophy is “health for all,” but its organization is bureaucratic. Typically, a health authority employs all health care workers and public health officers as part of a wider multidepartment executive with responsibility for the full spectrum of public facilities across populations from 10,000 to >100,000. Nurses commonly run clinics with doctors operating as supervisors or strategic consultants. Both vertical and horizontal integration are planned through committees that devise care pathways and cross‐organizational innovation. Line management is the norm, but often at a local level charismatic nurses act as community leaders in their “spare time.” This entrepreneurial interface with voluntary work and community development is largely invisible in published papers. In the United States, a number of tribal health service systems are examples.

Managed care enterprises, in which primary care clinicians are contracted by insurance companies to deliver agreed packages of care, developed in the United States to bring disease management under the control of one health insurance company. This approach has been adopted in many low‐ and middle‐income countries as a condition of international loans. It has been used in many high‐income countries as well but has fallen out of favor in much of the United States as the illusion of informed patient choice came to the fore. Its philosophy is rooted in market theory and focuses on ways to control wait times, prescriptions, diagnoses, and packages of care. Those who purchase services are often separated from those who provide them to make one accountable to the other. Deviation from the norm results in financial sanctions. Vertical integration of medical care is its great strength by tracking all links and costs in the care pathway. Horizontal integration is present or absent depending on the local context, but difficulties in measuring this can result in it being misrepresented, with the term “horizontal integration” used to mean local management of medical conditions. In the United States, Kaiser, Group Health, and others are examples that have persisted.

Community development agency approaches carry a concern for social justice and see “health as a citizen, rather than professional issue.” Basic principles include capacity building, shared responsibility, and local ownership. It aims for simultaneous vertical and horizontal integration. Health centers typically serve populations of 10,000‐20,000. Local multidisciplinary committees develop economic policies that include control of pharmaceutical supply and local pricing, as well as using mapping techniques and community diagnosis to evaluate social capital. A network of cooperatives and neighborhood committees support sophisticated horizontal integration of health care. Women and elders often became leaders. The approach is overtly connected with the notion of a learning organization, and practitioners are often required to take part in learning events such as telemedicine links with a university hospital. Local autonomy is tempered by a national focus on equity and targets for capital investment. Integrated information systems facilitate the amalgamation of data. Public health and personal care practitioners work side by side. Management concentrates especially on communication systems. In the United States, community development agencies often bring social and housing services together with community health centers providing care to disadvantaged populations.

The relational adaptability of the generalist approach and the sociopolitical adaptability of primary care systemic organization are its great strengths. This local adaptability is a source of primary care's positive effects on population health, equity, and cost. New and creative models 39 , 40 , 41 are continuing to emerge to adapt to the changing sociopolitical and environmental landscapes and population health needs. Such models were stimulated by the COVID‐19 pandemic and growing use of telehealth 42 , 43 , 44 and by the recognition of opportunities for greater integration with behavioral health, 45 , 46 social drivers, 47 , 48 and public health. 49 , 50 , 51 However, the resulting large heterogeneity and often helpful lack of standardization has made primary care challenging to understand. 52 This lack of understanding has consequences.

Interacting Mechanisms: How Primary Care Works to Advance Person and Population Health

(Mis)understanding Primary Care

Amid the multilevel factors influencing population health, primary care acts in the middle. 53 It works to foster population health one person at a time. Primary care serves a boundary‐spanning role between individuals' experience of health and illness and the collective of medical, social, and environmental factors that advance or impede health and healing. 24 It provides the large majority of health care. 54 On the basis of personal knowing that comes from seeing people in sickness and in health over time, primary care serves as a connector and a buffer within a system that can be brilliant at delivering commodities of health care 55 but dangerous if that care is fragmented and decontextualized. 28 Primary care serves as a bridge to targeted use of specialized services that make them more effective and limit their risks. 56 Primary care also can serve as a link with public health and social services and environments that support population health. 49 , 57 Primary care provides contextually tailored whole‐person care that advances equity in health care and health 58 and both buffers structural inequities and fosters the social capital and relationships needed to advance systemic change. 5 , 59 People with social disadvantage, including poverty, persons of color, and the uninsured are more likely to receive care from family physicians, 60 and greater access to primary care is associated with improved life expectancy. 3 , 61 , 62

Support for primary care must align with how it functions, and yet how primary care works is widely misunderstood. 63 , 64 Too often, it is conceptualized, measured, and incentivized based on pieces of the whole—disease care or “management,” preventive service delivery, serving as a referral mechanism, etc. 14 Misunderstanding primary care has led to often well‐intentioned but damaging efforts to improve these parts, absent an understanding of their interdependencies and how they articulate as a whole. 15 , 16 , 19 , 65 For example, the combination of emphasizing access over continuity, expanding required checklists on electronic medical record templates, and compensating physicians on performance of a few selected disease measures, all work together to diminish the perceived value of the healing relationship and to create professional role conflict, moral distress, untenable data gathering and administrative burden, and burnout. 31

In the following sections, we explore some of the complexly related mechanisms by which primary care can deliver its value. This exploration begins by asking those receiving, providing, and paying for primary care, “what matters?” That exploration revealssimple rules and a patient‐reported measure that help us to understand health and health care as complex systems that require a balanced mix of specialized and generalist services. Then we examinesome of the features of primary care that must be understood if we are to advance primary care as a personalizing and integrating force for population health.

Asking Those Providing, Receiving, and Paying for Primary Care

A recent survey asked members of the public, clinicians, and payors what is most important about primary care. In crowdsourced surveys of nearly a thousand people, patients and clinicians were largely congruent in valuing relationship, personalized attention, and accessibility, whereas health care payors tended to emphasize health care organizational factors. 66 The identified attributes of what matters then were vetted and interpreted at the Starfield Summit III, a two‐and‐a‐half day workshop among 70 national and international health care delivery experts, including patients. Participants shared personal, research and policy experiences, and surfaced the multifaceted mechanisms by which primary care can foster personal and population health, healing, and systemic value. 66

During the summit, participants struggled to fit the interrelated complexity of the generalist approach and primary care into the usual reductionist classification and measurement systems that assume that the whole is merely the sum of its parts. The complexity of primary care was well captured in stories, and participants were able to begin to identify the mechanisms by which those complex ways of knowing and doing could be described. But in trying to operationalize measurement of these ways of knowing and doing, they became quite anxious that a measure of any individual function could be misused. They emphasized that the individual facets of primary care must be understood, acted on, and supported as a whole. The different ways of knowing and doing represent trade‐offs, and the right decision among the competing demands and opportunities requires local knowledge on the ground and in the moment.

Careful analysis of responses from the surveys and of the work by the Starfield III Summit participants revealed two complementary ways of understanding and assessing primary care: a set of simple rules and a parsimonious holistic measure.

Initial analyses built on principles from complexity science and uncovered three simple rules that, when actualized together by patients, clinicians, and practices, and supported by systems, describe the generalist approach from which the population health outcomes of primary care emerge. 67 Subsequent analyses also revealed complementary simple rules for the more narrowly focused specialist function. 67

Further analyses identified a parsimonious set of individual attributes that, when used as a set rather than assessed individually, can focus attention and support on the mechanisms by which primary care generates value. 68

Simple Rules to Understand the Craft of Generalism and the Complementary Specialist Function. Sometimes, the emergent behavior of complex systems can be described and understood by simple rules. 69

Consider an analogy. The marvelously complex flocking behavior of birds can be described by three simple rules followed by each bird: 70

Line up with those close by;

Steer toward the emerging center mass of those around you;

Seek to be equidistant from your neighbors so you do not collide.

Similarly, when clinicians act as specialists, their behavior can be explained by three simple rules that represent the dominant approach to health care organization and quality measurement: 67

Identify and classify disease for management;

Interpret through specialized knowledge;

Generate and carry out a management plan.

However, when clinicians act as generalists, 25 their thoughts and actions invoke three simple rules that are focused not only on single disease elements but on the whole person. 67 Considering the person in their larger context 28 requires that they do the following:

Recognize a broad range of problems/opportunities/capacities;

Prioritize attention and action with the intent to promote health, healing, and connection;

Personalize care based on the particulars of the individual or family in their local context.

These generalist rules work together to focus care on what is most important for each patient at a given time, and over time through a life course perspective.

Recognizing requires foraging for salient information 71 based on a comprehensive generalist perspective—watching for teachable moments, 72 , 73 clues, risks, and opportunities. 25

Prioritizing begins with the broad, inclusive generalist perspective and then sorts, ranks, and negotiates what is most important to identify what action or set of actions in the moment and across moments, has the greatest potential to advance health, healing, and connection. 25 , 63 , 74

Personalizing care moves from the statistical generalities of evidence‐based medicine to the nitty‐gritty of this person or family in this particular moment and place and context. 27 Over time, there are many particular moments, 10 , 25 , 75 and attending to these develops knowledge of the person, trust, and trustworthiness. 27

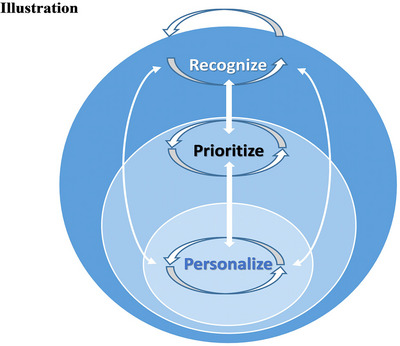

As shown in Figure 1, the generalist three simple rules interact and operate in an iterative fashion: 76 , 77 1) as new information reframes problems and opportunities; 2) as what is most important continually evolves; and 3) as hypotheses are tried out with the intent of promoting some combination of health, healing, and/or connection. The cumulative effect of actualizing these rules is an investment in a relationship bank that can be drawn on with interest during challenging moments in the health and lives of individuals, families, and communities. 74

Figure 1.

The Iterative Nature of the Craft of Generalism [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Balanced with the right mix of specialist approaches and connected with functional social systems, this generalist approach serves as an integrating and personalizing force in systems that otherwise tend to be fragmented. 64 , 78

The paradox of primary care is not a paradox if we understand that focusing comprehensively on the needs of the whole person, over time, in relationship, combined with selective use of more narrow expertise, results in care that is personalized, integrated, and prioritized. 74 , 79 That approach fosters healthy individuals, families, and communities and results in a fair, effective, and sustainable health care system. 1 , 4

Eleven Items That Reveal the Whole of the Craft of Generalism and the Primary Care Function. Further analyses of both the crowdsourced original data and the work of the Starfield Summit III participants revealed 11 attributes that represent what those receiving, providing, and paying for primary care find to be most valuable. Interestingly, these diverse attributes, as assessed by the patient, all factor analyze into a single factor 68 , showing that there is strong conceptual coherence to the comprehensiveness of a person‐focused approach to health care. These 11 attributes have been subjected to extensive reliability and validity analyses 68 , 80 , 81 and translated into 30 languages 82 as a patient‐report measure of what matters in primary care—the Person‐Centered Primary Care Measure. 68

The actual measure is freely available at the Person‐Centered Primary Care Measure website 83 or a public domain scientific article, 68 but the 11 items assessed by this measure can be summarized as follows:

accessibility;

a comprehensive, whole‐person focus;

integrating care across acute and chronic illness, prevention, mental health, and life events;

coordinating care in a fragmented system;

knowing the patient as a person;

developing a relationship through key life events;

advocacy;

providing care in a family context;

providing care in a community context;

goal‐oriented care; and

disease, illness, and prevention management.

The Person‐Centered Primary Care Measure has been endorsed by the National Quality Forum and by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for use in measuring high value primary care in quality performance programs.

Putting a Face on the Generalist Approach to the Primary Care Function

Many practitioners, patients, and observers have witnessed how the craft of generalism, 64 , 72 , 84 as manifested in primary care, influences the health of real people over time in ways that collectively lead to improved population health. Complex system models 85 , 86 and theories 87 , 88 can help to convey how health emerges at the level of the person and population by paying attention to related factors on the ground, but many times, that complexity is most easily shared through stories. 89 , 90 Below, two pseudonymous composite stories of real people begin to put a face on this complexity.

The Williams Family. Mrs. Williams lost her job and her health insurance at the start of the pandemic and was humbled to have to go to a community health center when her prescriptions ran out. It was a four‐week wait to see a gender/race‐concordant physician, so she settled for Dr. White, whom she had seen on TV doing COVID testing at a homeless shelter. At least he seemed humble. She had worked hard to get her four specialists to prescribe the latest medications for her diabetes, hypertension, anxiety, insomnia, irritable bowel syndrome, and osteoarthritis and did not want her new doctor messing with things. At the first visit, he renewed each medication. When he pointed out the possible beneficial effects of working in a bit of regular physical activity for many of these illnesses, she said that her knee pain and the burning in her feet were too bad for that.

Over the next few months, Mrs. Williams came in for a couple of respiratory infections that, thank goodness, turned out not to be COVID. On one of the visits, Dr. White diagnosed diabetic neuropathy as one cause of her leg pain, and she got him to prescribe the pill she had seen on TV, even though it was expensive. Then her pregnant daughter lost her job, and Mrs. Williams had her come in. Dr. White had the daughter start seeing one of the midwives at the practice, and he referred one of the grandsons to see the male social worker for counseling about his depression and drug use. When her grandson was shot by a drug dealer, Mrs. Williams and her daughter and Dr. White cried together, and the social worker started seeing the whole family.

When her savings ran out, Mrs. Williams finally was able to hear what Dr. White had been saying, that sometimes, doing “good enough” on a bunch of things at the same time ends up being “great.” He prescribed a low‐dose antidepressant that was not a first‐line treatment for any of her conditions but reduced her panic attacks, made the diabetic neuropathy burning leg pain tolerable, and slowed her diarrhea to the extent that she felt more comfortable leaving the house. The medication made her sleepy, but taking it at bedtime helped the insomnia, and finding she had more energy, she let Dr. White have her see the health coach, who reminded her of her grandson. Mrs. William's daughter was showing signs of diabetes, and so with a tailored plan from the coach, they all started walking together during the day when the streets felt safer. With her reduced blood pressure and blood glucose and by doing “good enough” for all her illnesses together, Dr. White was able to reduce her medications from nine to four inexpensive generics.

Mr. Williams was dead set against vaccines, but Mrs. Williams made him come in and talk to Dr. White, and he at least let everyone else in the family get the COVID shot. When Mrs. Williams got “the COVID” anyway, Dr. White discussed with the whole family the wishes she had expressed in her living will and then called the intensive care unit (ICU) physician at the hospital with them. After nine days in the ICU, Mrs. Williams died within an hour of being taken off the respirator.

Mrs. Williams’ family continues to see Dr. White and his team, sometimes remembering her together.

Mr. Falstaff. For a number of years, Mr. Falstaff enjoyed flying his private jet to whatever world‐class specialist was recommended during his annual two‐day executive physical at a large well‐known multispecialty practice. He was bothered by waxing and waning fatigue and sometimes incapacitating headaches. He accumulated many tests and several diagnoses, but after a while, he decided he needed a “quarterback” to lead his medical care. His executive assistant made an appointment with Dr. Beck in his hometown.

During his first visit, Dr. Beck corrected him that she was not a concierge physician who charged a high retainer fee on top of insurance. She was a direct primary care physician. Mr. Falstaff scoffed at the $100 per month fee that supposedly covered all his primary care and that was low enough that people with no insurance or just a cheap high‐deductible insurance could afford. How good could she be if she did not respect herself to charge enough to make a decent living?

“Do the math,” she said. “I have a panel of 500 patients, rather than the 2,400 I had when I was employed by the health system. So I can spend time with people. And I keep my overhead low.”

“Too low.” His face was almost a sneer. “You can't even afford a waiting room.”

“Nobody waits.”

As long as he was there, he let her do her thing. When he left after an hour of mostly talking, he felt more known and respected than after a day of world‐class prodding and high‐tech testing at his annual physical. Because his wife already had paid for the whole year, he decided to accept Dr. Beck's invitation to come back after she had gotten all his medical records.

“You have a lot of medically unexplained symptoms,” she said.

“Most of the tests come back negative.”

She asked him to keep diaries of his symptoms and life events and diet. Over the year, she worked with him to experiment with several diet changes, and when some of the symptoms improved, she took the opportunity to challenge him about the way he medicated himself with alcohol. He seldom came into Dr. Beck's one‐room office, but they worked together by text and talk.

Mr. Falstaff got no magical diagnosis but developed understanding of his body and how his mind affected it. After a rare in‐person visit, he saw a family of migrant workers waiting outside in a dilapidated truck. He watched as they entered Dr. Beck's office. When he got home, he sent an letter to Dr. Beck with a note that said, “Eventually, once people see what a personal physician can do, the market will drive more physicians and patients into this kind of practice. But until then, here's a check so more people can experience it now.”

International and Interdisciplinary Work to Understand the Mechanisms of Primary Care

A considerable body of literature conceptualizes the mechanisms by which primary care works. Barbara Starfield, whose international comparative research revealed the positive population health and cost effects of primary care 4 , 91 and whose later work focused particularly on its equity effects, 5 , 92 , 93 developed a model of health service use 94 in which primary care was central. 8 Nested within that model, she described four cardinal functions of primary care, widely referred to as the four Cs: first contact (going to primary care first for each new need or problem), continuity (later called longitudinality—seeing the same primary care clinician over time), comprehensiveness (addressing all health‐related needs in the population except those too rare for primary care clinicians to maintain competence), and coordination (iharmonizing care when patients need to be seen elsewhere). 4 , 5 , 91

Ian McWhinney, who trained in England, practiced in Stratford‐Upon‐Avon, and then had a central role in launching primary care in North America, 95 , 96 articulated primary care's functions, as embodied by family physicians who

are committed to the person rather than a particular body of knowledge or group of diseases;

seek to understand the context of the illness;

see every contact with the patient as an opportunity for prevention or health education;

view their practice as a population;

see themselves as part of a communitywide network of supportive and health care agencies;

ideally, share the same habitat as their patients;

see patients in their homes;

attach importance to the subjective aspects of medicine; and

act as a manager of resources. 97

Other early founders, as well as settlers and homesteaders in the reinvention of the ancient craft of the generalist healer as primary care, have added refinements based on their grounding in practice, community health, research, or policy. These conceptualizations examine the healing journey 98 and how primary care relationships can result in healing for people who have suffered diverse illness and life traumas. 77 , 78 , 98 Empirical studies and systematic reviews characterize the different effects of relationships 99 as manifested in interpersonal or informational continuity 10 , 100 , 101 , 102 and highlight the importance of a sufficiently broad scope of primary care 88 , 103 , 104 , 105 to allow the whole person to be seen and cared for in their community context. Other work highlights the emergent outcomes of the profound combination of broad scope, first contact, and ongoing relationship in enabling the most important and effective care to be provided at the right moment over time to meet the needs of people in their personal, family, and community contexts. 25 , 28 , 104 , 105 , 106

One conceptual innovation that has profoundly affected how primary care is understood, organized, and paid for, is the Chronic Care Model 107 , 108 proposed by Ed Wagner for proactively organizing evidence‐based care for the growing number of chronic diseases that drive so much of health care costs. This model has been expanded to espouse a proactive approach to evidence‐based preventive services 109 and population health. 110 As a result, primary care has become organized around providing chronic illness and preventive care 111 and is less available for addressing patients’ acute illnesses and most salient felt needs. 111 This diminished availability to patients’ immediate needs and concerns has reformulated primary care as a collection of health services, rather than as a locus of health care. The loss is doubled as the simple rules of generalist practice are interrupted by a commodified health care approach that diminishes the relationships developed from meeting those immediate concerns. 74 Dr. Starfield's untimely death halted the final development of a paper that she and Drs. Wagner and Stange were working on to examine the trade‐offs in balancing responsive availability for patients’ acute problems with proactively managing chronic illnesses. Dr. Starfield felt that something important was being lost in the recent decades’ emphasis on directively managing chronic care over the generalist simple rule to recognize and be available and open to people's immediate concerns. 112

Another conceptualization identifies a hierarchy of health care that begins with meeting people's basic needs for care of acute and chronic illness, prevention, and mental health. 74 The resulting personal knowing and sense of being known sets up the ability to integrate care across these domains and supports the underappreciated primary care attribute and second simple rule to prioritize care. The deep understanding that results from such integration allows primary care clinicians to abide with people when cure, disease management, and/or prevention are not possible. It allows them to be present when healing—transcending suffering toward meaning—might be within reach, even if that means sticking with the person as they let go of life. 77 , 113 , 114

Other observers have articulated the third simple rule, to personalize care, through such strategies as helping people to find a sense of safety, not only as part of the process of providing primary care but also as an important aspect of people's lives. 78 Some have identified the benefits of recognizing whether patient encounters are routines, ceremonies, or dramas, and importantly, 115 of protecting people from the dangers of overtreatment, 56 of integrating primary care and behavioral health, 48 of managing complexity 36 , 64 , 116 and multimorbidity, 36 , 117 and of providing sufficient time to move beyond the superficial to know people and their problems in context and to identify and actualize meaningful solutions. 118 , 119 , 120

Early exemplars linked knowing individuals and families with knowledge of the community 121 and early bottom‐up manifestations such as community‐oriented primary care 122 , 123 now are being reinvented as clinical population medicine, 124 population health, 125 and as the (sometimes for‐profit) 126 integration of the social determinants of health 127 , 128 into health care. 47 , 57 , 129 , 130 , 131 The success of primary care physician–led ACOs in advancing population health while controlling costs, compared with the poor performance of hospital‐led ACOs, shows the potential of placing primary care at the center of health care organization rather than the periphery. 132 Calls for greater support to integrate primary care and public health 133 have been intensified by the pandemic. 44 , 49

One of the largest bodies of work examines how primary care should be organized, ranging from recent efforts to expand toward team approaches 17 , 46 , 134 , 135 in the patient‐centered medical home 136 , 137 , 138 and even more recent and contrasting direct primary care 39 , 139 efforts to reduce overhead, administrative burden, and panel size so that clinicians can invest the vital resource of time needed to develop relationships and provide and integrate care.

At the same time, a challenging body of research and policy development examines the workforce needed to provide and support primary care in different settings and to respect the wholeness and dignity of individuals from different disadvantaged or otherwise vulnerable populations. 140 , 141 , 142 , 143 Related work highlights difficult policy decisions regarding the balance of workforce investment and upstream social versus downstream disease care and the possibilities of primary care as an effective interface that turns rationing into personalizing. 144 , 145

Much of this work shows, explicitly or implicitly, that to be most effective at advancing population health, primary care and its heart—the craft of generalism—must be embedded in societies that have some sense of the collective as well as valuing the individual and that support and value various integrating system attributes and functions. 2 , 91 , 146 , 147 Indeed, international comparisons that attempt to discern the effects of variably manifested primary care on population health are confounded by the fact that societies that value primary care also tend to value investment in other collective goods, such as social services, safety nets, and other factors that influence population health. 4 , 91 , 148

The attributes of primary care and their larger societal contexts represent trade‐offs. 149 Optimizing individual attributes of primary care is unlikely to advance the whole of person and population health, and the right decisions on where to focus resources requires considerations of local particulars, larger context, and time. 150

The 2021 report of the (US) National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine National Academies of Science, Education, and Medicine (NASEM) on Implementing High‐Quality Primary Care 11 identifies primary care as a “common good” that must be available to everyone and financed in ways that assure accessibility to it as a whole and availability as a relationship context for advancing person and population health. The report also emphasizes the importance of integrated whole‐person care, sustained relationships, the potential of interprofessional teams, and the critical roles of community, equity, and supporting diversity in the settings and modalities used to deliver primary care.

Interaction of Primary Care With the Other Population Health Influencers Investigated in This Special Issue

One of the points of this special issue of The Milbank Quarterly is that there are many complexly related, multilevel drivers of population health. There is no magic bullet. The multiple drivers of population health must be considered collectively, with understanding of how they work together or oppose each other, if we are to advance population health.

One of the points of this paper is that amid many multilevel drivers of population health, primary care embodied with a generalist approach can serve a personalizing, boundary‐spanning function toward population health—insufficient by itself, but essential. Therefore, Table 1 examines how specific primary care mechanisms might be particularly helpful in supporting the other drivers of population health explicated in this special issue of The Milbank Quarterly. Because of the interrelatedness of different primary care mechanisms, for many of the population health determinants in the table, it is the totality of primary care mechanisms together that is likely to be most helpful.

Table 1.

Primary Care as a Personalizing, Boundary Spanning toward Integration for Population Health

| Special Issue Articles/Topics | Relevant Primary Care Mechanisms |

|---|---|

| Drivers of health | |

| 1. Health equity (including marginalized populations) | A‐J |

| 2. Systemic racism and health | A, G, I |

| 3. Social drivers of health | A, C, E, G, I, J |

| 4. Upstream policy changes | F, G |

| 5. Medicalization and individualism | A, C, F, H, I, J |

| 6. Climate change and environmental threats to health | G, I |

| 7. Childhood poverty and health | A‐K |

| 8. Education and health | A, C, E, F, G |

| 9. Housing and health | A, C, E, G |

| 10. Policing and health | A, G |

| 11. Commercial drivers of health | A‐K |

| Major health challenges | |

| 12. Obesity and chronic disease | A‐K |

| 13. Substance use/overdose | A‐K |

| 14. Aging (including long‐term care) | A‐K |

| 15. Mental health | A‐K |

| 16. Alcohol use | A‐K |

| 17. Gun violence/gun safety (including suicide) | A, B, E, G, J, I, J |

| 18. Violence/intentional and unintentional injuries/trauma | A, B, E, G, J, I, J |

| State‐ and municipal‐level policies and strategies | |

| 19. State‐level policies | B, G, I |

| 20. The politics of population health | G, I |

| 21. Municipal‐level policies | G, I |

| Global health | |

| 22. Migration/immigration | A‐K |

| 23. Cities/urbanization | A‐K |

| 24. Global health governance and institutions | G |

| 25. Health care spending vs. social spending (including equitable resource allocation) | A‐K |

| Public health | |

| 26. The public health infrastructure | E, G, I |

| 27. Pandemic preparedness | A, B, G, I |

| 28. Transforming public health data | A‐K |

| 29. The Supreme Court and public health | G |

| The US health care system | |

| 30. Role of US health care system in population health (including access, affordability) | A‐K |

| 31. Primary care | A‐K |

| 32. Workforce (including health care delivery, social services, public health) | A‐K |

| 33. Reproductive health | A‐K |

A. Generalist craft: Recognize, Prioritize, Personalize

B. Accessibility

C. Comprehensive, whole‐person focus

D. Integrating care across acute and chronic illness, prevention, mental health, and life events

E. Knowing the person

F. Developing a relationship by living through key life events

G. Advocacy

H. Contextualizing based on knowing the family

I. Contextualizing based on knowing the community

J. Targeting based on knowing the person's goals

K. Helping to manage disease, illness, and prevention

Implications for Policy

How are we to achieve the benefits of systems that invest in primary care—better population health, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 147 greater health equity, 5 , 6 , 58 , 59 , 151 , 152 health care quality, 7 , 153 and lower health care expenditure? 1 , 4 , 9 , 10 How can we advance primary care as a force for integration and personalization across our fragmented and depersonalizing health system?

Achieving the benefits of high value primary care for population and person health requires new understanding and action by federal, state, and health care system leaders, as well as by those providing and receiving care. It requires investment in primary care as a common good. 11 , 154 It requires that we generate grounded and systemic knowledge, develop new systems that support a generalist approach to complement disease‐specific care, and support, rejuvenate, and expand a heroic but beaten down workforce. 155 , 156 , 157 , 158 , 159

Countries that have healthier populations than the United States tend to spend less on health care as a whole and more on the primary care and social services. 4 Even in the United States, where it is undervalued, primary care accounts for the following:

500 million patient visits each year—more than half of all patient visits; 160

informed by only 0.2% of the National Institutes for Health (NIH) research budget. 165

Generating the Knowledge Needed to Advance the Health of Whole People and Populations

Is it not ironic that the United States spends hundreds of billions of dollars each year on basic research to understand the mechanisms of rare diseases and biological pathways that affect only a small percentage of the population but has no structured approach to investigating the effects of a foundational aspect of high‐quality health care and population health that can affect the health of the entire population? There is an NIH Institute for General Medical Sciences, but it funds only laboratory research. The Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research is Congressionally mandated to support primary care research but mostly focuses on health services research, 166 has a pittance of the NIH budget, and does not fund basic science. 167 And the NIH institutes themselves are organized around diseases and special populations. There is no support for elucidating the generalist approach to primary care to put all the pieces together for whole people and the collective of the population. This must be remedied.

An NIH Institute for Generalism is needed to support the generation of new knowledge on how to put the pieces back together to advance the health of whole people, communities, and populations. Even more important is generating new knowledge that does not start with the parts but emphasizes the whole. Advances in system science methods now make this possible. 36 , 86 , 168 , 169 , 170 , 171 Such research embraces complexity by integrating quantitative and qualitative methods—using both statistics and stories, numbers and narratives—to tell the complete story of how health and equity are won and lost. 172 , 173 Such research requires the development of generalist laboratories, building on early but largely unsupported work in practice‐based research networks, 174 , 175 , 176 , 177 , 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 community‐oriented primary care, 182 , 183 , 184 and participatory methods 185 , 186 , 187 that emphasize the collective.

The generalist approach and primary care are worthy of, and in desperate need of, the generation of relevant scientific knowledge so that efforts to improve primary care are informed by understanding how it works. The efforts of recent decades to reform primary care without understanding it have fragmented it, 19 burned out and morally distressed the current workforce, 16 , 188 kept the next generation from joining in, 142 , 189 and have fragmented and depersonalized the larger health care and health systems 190 to a point of such low value that it is an international embarrassment and a national tragedy. 191 , 192

Investing in Primary Care as the Health Care System Lynch Pin and the Health System Integrator

Decades of rising investment in technical and narrowly focused health care services and burdensome payment models have impoverished the whole‐person care enabled by primary care and have not supported its much‐needed partnerships with public health and social services. 119 , 193 The perverse incentives of our current system treatboth the providers and receivers of care as objects that can be used to generate additional commodities of care. The result is great expenditure on often dangerous services but little effort to prioritize which services provide value and to integrate them to foster health.

Implementing High‐Quality Primary Care 11 calls for making primary care accessible to the entire population and for rebalancing both how and how much payment is rendered. Increasing accessibility will require investment in workforce development. But to attract generalists to the workforce, the payment system must value and support their work. The NASEM report calls for rebalancing the current unfair system that pays those providing narrow care twice as much as those offering comprehensive care. It calls for increasing national spending on primary care 154 through blended payment that increasingly pays for primary care as a foundational common good, moving away from fragmented payments for disease‐focused activities and toward fixed payments for taking care of whole people and populations. Paying for narrow services may make sense for specialized care, but it does not support the integrating, personalizing, and prioritizing functions of primary care. Capitated payments for primary care as a common good and foundation for health care have the potential to reduce the current stifling administrative burden and can unleash the potential of the current workforce even as an expanded workforce is being developed.

Supporting the Generalist Approach and a Primary Care Workforce

For decades, primary care clinicians have tried to hold together an increasingly fragmented health care system that has become more about generating revenue than about advancing the health of our people and population. That work has become untenable. 155 Nearly every external effort to bring support to primary care has added substantial administrative burden 16 , 65 , 194 that cancels the intended benefit by distracting from the simple rules of recognizing, prioritizing, and personalizing care to advance health and healing by investing in relationship. 67 , 119 , 193

Measuring and paying for fragments of care, combined with the huge burden of then documenting those fragments, 63 , 119 , 193 both steals attention from the work of care delivery and drives away members of a shrinking workforce who are actually trying to provide that care.

The pandemic furthered the disconnect between what primary care longs to be and how its role is misunderstood and its payment and support misaligned. As we supported emergency departments and ICUs as the “frontlines” of the COVID‐19 pandemic, decried misinformation and inequitable responses, struggled to make centrally run testing and vaccination available, and bemoaned the preventive and chronic and non‐COVID acute care that was being missed—we were blind to those on the primary care frontlines who were using their relationships with people and communities to do what was needed despite minimal support, developing telehealth and outreach systems with potential for increasing care accessibility for vulnerable populations and that are persisting even as the pandemic winds down. 155 , 195 , 196

In contrast, Germany relied on and supported their primary care practices as the frontline response to the pandemic, and even before sufficient testing and treatment and vaccinations were available, they had better early outcomes than most other countries. 44 , 197 There is a poorly recognized but vitally important role in person and population health for care that is based on ongoing relationships, focused on the whole person in their family and community context. The primary care workforce trying to fill that role, and the individuals, families, and communities that they are trying to serve, need our recognition and support.

Our primary care workforce needs time and support to recover from the pandemic and from decades of trying to hold together a system that is bent on models that support effective business practices rather than effective health care. 155 The two can coexist, but prioritizing margin over mission in this case will always lead to health care as a set of commercial goods rather than as a common good. This recovery can be engendered by moving quickly toward fixed payment systems that value primary care as a foundational gateway to health care and a connector to public health and social services. It can be fostered by dramatically changing the current measurement and documentation systems that are designed to support billing rather than providing, integrating, and personalizing care. Information technology can be revamped to focus on clinically relevant rather than billing‐required information and by reducing documentation burden by focusing quality measurement on supporting the integrating, personalizing, and prioritizing functions of primary care, such as those assessed by the National Quality Forum (NQF)/Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) endorsed Person‐Centered Primary Care Measure. 68

Valuing and supporting primary care have the potential to draw into the workforce those who want to care for whole people and to support that impulse in the entire workforce. Novel training approaches have been proposed for the individuals and teams needed for this work. 49 , 199

It also is vital to begin to invest in rebalancing toward 50% of the health care workforce serving in primary care, as is seen in more functional health care systems. 161 , 200 Currently, graduate medical and nursing training is hospital based, and the needs of the population would be better served by moving a substantial portion of that training to community settings and community ownership to better reflect population health needs. 198 Redirecting graduate medical education and graduate nursing education support, including Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Title VII funding, toward primary care and community training settings 11 and refocusing health care professional school admission processes so that trainees better reflect underserved populations 200 are important first steps. In addition, there is a growing need for training to better reflect the interprofessional practice setting and to develop integrated training programs to train other members of the primary care team. 11 The transition to, and sustenance of, practice in currently underserved settings and populations needs greater support, including increased HRSA Title VIII funding, loan forgiveness for those practicing in primary care, and additional incentives for those serving high needs and underserved populations. 201

What Is so Threatening About Generalism?

Why, despite occasionally recognizing the importance of a generalist approach, 13 do we do so much to disparage and disadvantage it? Despite its macro‐level benefits and on‐the‐ground hominess, there is something threatening about a generalist approach and primary care. Most people like the idea of a personal physician. 203 , 204 For people who have experienced the value of a personal physician over time and in moments of crisis, the benefit is readily apparent. But fewer and fewer Americans have a regular and ongoing care relationship with a primary care clinician; the ideal seems unreachable, and for many, it is unattainable. 17 , 119 , 193 , 205 For those dealing with a new concerning health condition or living with multiple chronic conditions, medically unexplained symptoms, or socioeconomic, racial, or ethnic prejudice, dealing with the US health care system is a lonely, scary, costly, and dangerous proposition. 17

And yet, we as a society are suspicious of primary care and the generalist approach. Perhaps the combination of large‐scale benefit combined with the paradoxical lack of anything apparently “special” about generalism is so difficult to understand that it is threatening. Certainly, in the United States, the idea of primary care as a common good 11 and its emphasis on the collective,as well as the person and family, smacks of socialism as well as individualism, and is easily maligned.

Simple, reductionist explanations are much more appealing to the Western psyche than are attempts to understand complex system properties such as the whole emerging as greater than the sum of the parts. 36 , 64 It is much easier to try to understand, measure, and incentivize health improvement as the sum of its parts, 14 as we have done for primary care and public health. Unfortunately, it does not work like that. And in trying to command and control primary care, we kill the horizontally integrating and personalizing functions that provide much of its value. 34

Breaking things apart into their pieces is easier than putting things (and people) together. 14 Dividing is an easier way to gain and maintain mastery of market share and (the often false) prediction of outcomes. Our current system's fragmenting and depersonalizing are problematic but profitable. No wonder generalism is threatening.

It is vital to understand what is valuable about primary care—how it works—and to support those generalist functions and the relationships necessary to make them work so that those on the front lines have time and resources to invest in relationships to understand and meet the local needs of individuals, families, and communities. From that investment, population health, equity, quality, and sustainable cost are emergent properties.

Conclusion

In summary, the following policies will advance population health through primary care:

Create and fund an NIH Institute for Generalism to support the generation of new knowledge on the health of whole people, communities, and populations.

Actualize the recommendations of the NASEM report on Implementing High‐Quality Primary Care, 11 including a establishing and empowering a Department of Health and Human Services Secretary's Council on Primary Care and creating a scorecard to track progress in boosting state and national primary care infrastructure. 205

Invest in primary care as a common good by doubling the current 6% of health care expenditure on primary care to 12% 11 , 154 , 207 , 208 and paying for primary care through capitation as the relationship‐centered frontlines for a more integrated, personalized health care system.

Dramatically reduce administrative and documentation burden by revamping information systems to focus on clinically relevant rather than billing‐required information and focusing quality measurement on supporting the integrating, personalizing, and prioritizing functions of primary care, such as those assessed by the Person‐Centered Primary Care Measure. 68

Invest in expanding the primary care workforce by redirecting graduate medical education and graduate nursing education support, including HRSA Title VII funding, toward primary care and community training settings 11 , 199 ; refocusing health care professional school admission processes so that trainees better reflect underserved populations 200 ; developing integrated training programs for members of the primary care team 11 ; and increasing HRSA Title VIII funding and loan forgiveness for those practicing in primary care, with additional incentives for those serving high‐need and underserved populations. 201

Properly understood and supported primary care can be a force for integration and personalization in a fragmented, impersonal system and society. Primary care has untapped potential to do even more to advance population health and equity. To fulfill its role, primary care's complexly related mechanisms—the generalist craft and the primary care attributes—must be understood and supported as a whole. By working at the messy boundary regions between illness and health, person and population, primary care can help us move toward the unity of purpose that underlies our superficial differences and co‐create meaningful population health.

Funding/Support: This work is supported by grants from the University Suburban Health Center for the Wisdom of Practice Study, the American Board of Family Medicine Foundation for the Larry A. Green Center for the Advancement of Primary Health Care and for Drs. Stange and Etz as Distinguished Scholars, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for the Starfield Summit: Developing a national Strategic Vision for Primary Care conference (1 R13 HS025312‐01) and the study of Novel, High‐Impact Studies Evaluating Health System and Healthcare Professional Responsiveness to COVID‐19 (1R01 HS28253‐01). Dr. Etz's time is also supported as a Visiting Visionary by the Nova Institute for Health.

References

- 1. Starfield B, Shi LY, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457‐502. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kringos DS, Boerma W, van der Zee J, Groenewegen P. Europe's strong primary care systems are linked to better population health but also to higher health spending. Health Affairs. 2013;32(4):686‐694. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37(1):111‐26. 10.2190/3431-G6T7-37M8-P224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Starfield B. Primary care and equity in health: the importance to effectiveness and equity of responsiveness to people's needs. Humanity Soc. 2009;33(1/2):56‐73. 10.1177/016059760903300105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shi L. The impact of primary care: a focused review. Scientifica. 2012;2012:432892. 10.6064/2012/432892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:W184‐197. 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Starfield B. New paradigms for quality in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(465):303‐309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Starfield B. Primary care and health: a cross‐national comparison. JAMA. 1991;266(16):2268‐2271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Bruno R, Chung Y, Phillips RL, Jr. Higher primary care physician continuity is associated with lower costs and hospitalizations. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(6):492‐497. 10.1370/afm.2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine . Implementing High‐Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care. The National Academies Press; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):293‐299. 10.1370/afm.1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferrer RL, Hambidge SJ, Maly RC. The essential role of generalists in health care systems. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(8):691‐699. 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stange KC. The paradox of the parts and the whole in understanding and improving general practice. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(4):267‐268. 10.1093/intqhc/14.4.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Casalino LP. The unintended consequences of measuring quality on the quality of medical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(15):1147‐1150. 10.1056/NEJM199910073411511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bujold E. When practice transformation impedes practice improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):273‐275. 10.1370/afm.1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoff T. Next in Line: Lowered Care Expectations in the Age of Retail‐ and Value‐Based Health. Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stange KC. Forces for integration. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):192‐194. 10.1370/afm.2245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stange KC. The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):100‐103. 10.1370/afm.971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller WL. The story of general practice and primary medical care transformation in the United States since 1981. Commissioned paper for the NASEM Consensus Report: Implementing high‐quality primary care rebuilding the foundation of health care. 2021:1‐60. Accessed April 15, 2022. https://www.nap.edu/resource/25983/The%20Story%20of%20General%20Practice%20and%20Primary%20Medical%20Transformation%20in%20the%20United%20States%20Since%201981.pdf

- 21. World Health Organization . Declaration of Alma‐Ata: International conference on primary health care, Alma‐Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978. World Health Organization. Accessed April 11, 2022, https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/113877/E93944.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization . Declaration on Primary Health Care, Astana, 2018. World Health Organization. Accessed April 15, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO‐HIS‐SDS‐2018.61 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomas P. Collaborating for Health. Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stange KC. Refocusing knowledge generation, application and education: raising our gaze to promote health across boundaries. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 Suppl 3):S164‐S169. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stange KC. The generalist approach. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):198‐203. 10.1370/afm.1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gunn JM, Palmer VJ, Naccarella L, et al. The promise and pitfalls of generalism in achieving the Alma‐Ata vision of health for all. Med J Aust. 2008;189(2):110‐112. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01933.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McWhinney IR. ‘An acquaintance with particulars…’. Fam Med. 1989;21(4):296‐298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weiner SJ. Contextualizing care: an essential and measurable clinical competency. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(3):594‐598. 10.1016/j.pec.2021.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Defining and measuring the patient‐centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):601‐612. 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Soubhi H, Bayliss EA, Fortin M, et al. Learning and caring in communities of practice: using relationships and collective learning to improve primary care for patients with multimorbidity. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(2):170‐177. 10.1370/afm.1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heath I, Rubenstein A, Stange KC, van Driel M. Quality in primary health care: a multidimensional approach to complexity. BMJ. 2009;338:b1242. 10.1136/bmj.b1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Orszag P, Rekhi R. The economic case for vertical integration in health care. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2020;1(3). 10.1056/CAT.20.0119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Kessler DP. Vertical integration: hospital ownership of physician practices is associated with higher prices and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):756‐763. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. De Maeseneer J, van Weel C, Egilman D, Mfenyana K, Kaufman A, Sewankambo N. Strengthening primary care: addressing the disparity between vertical and horizontal investment. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(546):3‐4. 10.3399/bjgp08X263721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thomas P, Meads G, Moustafa A, Nazareth I, Stange KC. Combined horizontal and vertical integration of care: a goal of practice‐based commissioning. Qual Prim Care. 2008;16(6):425‐432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sturmberg JP, Getz LO, Stange KC, Upshur REG, Mercer SW. Beyond multimorbidity: what can we learn from complexity science? J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27(5):1187‐1193. 10.1111/jep.13521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chan M. Return to Alma‐Ata. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):865‐866. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61372-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meads G. Primary Care in the Twenty‐First Century. Radcliffe; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alliance DPC. Direct Primary Care Alliance ‐ Home. Accessed February 2, 2023. https://dpcalliance.org/

- 40. Crabtree BF, Howard J, Miller WL, et al. Leading innovative practice: leadership attributes in LEAP practices. Milbank Q. 2020;35(1):16‐22. 10.1111/1468-0009.12456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sinsky CA, Willard‐Grace R, Schutzbank AM, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high‐functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):272‐278. 10.1370/afm.1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Galea S. The post–COVID‐19 case for primary care. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(7):e223096. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Geyman JP. Beyond the COVID‐19 pandemic: The urgent need to expand primary care and family medicine. Fam Med. 2021;53(1):48‐53. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.709555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stange KC. What a pandemic reveals about the implementation of high quality primary care. Commissioned paper for the NASEM Consensus Report: Implementing high‐quality primary care rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care. National Academy Press; 2021:1‐45. Accessed September 16, 2022. https://www.nap.edu/resource/25983/What%20a%20Pandemic%20Reveals%20About%20the%20Implementation%20of%20High%20Quality%20Primary%20Care.pdf

- 45. Yonek J, Lee CM, Harrison A, Mangurian C, Tolou‐Shams M. Key components of effective pediatric integrated mental health care models: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):487‐498. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reiss‐Brennan B, Brunisholz KD, Dredge C, et al. Association of integrated team‐based care with health care quality, utilization, and cost. JAMA. 2016;316(8):826‐834. 10.1001/jama.2016.11232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gruß I, Bunce A, Davis J, Dambrun K, Cottrell E, Gold R. Initiating and implementing social determinants of health data collection in community health centers. Popul Health Manag. 2020;24(1):52‐58. 10.1089/pop.2019.0205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hoeft TJ, Hessler D, Francis D, Gottlieb LM. Applying lessons from behavioral health integration to social care integration in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(4):356. 10.1370/afm.2688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Westfall JM, Liaw W, Griswold K, et al. Uniting public health and primary care for healthy communities in the COVID‐19 era and beyond. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(Supp l):S203‐S209. 10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Institute of Medicine . Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sloane PD, Bates J, Gadon M, Irmiter C, Donahue K. Effective clinical partnerships between primary care medical practices and public health agencies. American Medical Association. 2009:1‐65.

- 52. Sinsky CA, Bavafa H, Roberts RG, Beasley JW. Standardization vs customization: finding the right balance. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(2):171‐177. 10.1370/afm.2654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peek CJ, Westfall JM, Stange KC, et al. Shared language for shared work in population health. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(5):450‐457. 10.1370/afm.2708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Green LA, Fryer GE, Jr. , Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):2021‐2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lown B. The commodification of health care. PNHP Newsletter. 2007(Spring):40‐44. Accessed July 15, 2014. http://www.pnhp.org/publications/the_commodification_of_health_care.php?page=all [Google Scholar]

- 56. Franks P, Clancy CM, Nutting PA. Gatekeeping revisited–protecting patients from overtreatment. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(6):424‐429. 10.1056/NEJM199208063270613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Farmanova E, Baker GR, Cohen D. Combining integration of care and a population health approach: a scoping review of redesign strategies and interventions, and their impact. Int J Integr Care. 2019;19(2):5. 10.5334/ijic.4197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shi L, Starfield B, Politzer R, Regan J. Primary care, self‐rated health, and reductions in social disparities in health. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(3):529‐550. 10.1111/1475-6773.t01-1-00036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ford‐Gilboe M, Wathen CN, Varcoe C, et al. How equity‐oriented health care affects health: key mechanisms and implications for primary health care practice and policy. Milbank Q. 2018;96(4):635‐671. 10.1111/1468-0009.12349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ferrer RL. Pursuing equity: contact with primary care and specialist clinicians by demographics, insurance, and health status. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(6):492‐502. 10.1370/afm.746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Basu S, Phillips RS, Berkowitz SA, Landon BE, Bitton A, Phillips RL. Estimated effect on life expectancy of alleviating primary care shortages in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(7):920‐926. 10.7326/M20-7381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pereira Gray DJ, Sidaway‐Lee K, White E, Thorne A, Evans PH. Continuity of care with doctors‐a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e021161. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stange KC, Etz RS, Gullett H, et al. Metrics for assessing improvements in primary health care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:423‐442. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lynch JM, van Driel M, Meredith P, et al. The craft of generalism: clinical skills and attitudes for whole person care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28(6):1187‐1194. 10.1111/jep.13624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tarn DM, Wenger NS, Stange KC. Small solutions for primary care are part of a larger problem. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(8):1179‐1180. 10.7326/M21-4509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Starfield III Summit . STARFIELD III: Meaningful Measures for Primary Care. Accessed May 15, 2022. http://www.starfieldsummit.com/starfield3/

- 67. Etz R, Miller WL, Stange KC. Simple rules that guide generalist and specialist care. Fam Med. 2021;53(8):697‐700. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.463594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Etz RS, Zyzanski SJ, Gonzalez MM, Reves SR, O'Neal JP, Stange KC. A new comprehensive measure of high‐value aspects of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(3):221‐230. 10.1370/afm.2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]